A2 Bovine Milk and Caprine Milk as a Means of Remedy for Milk Protein Allergy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

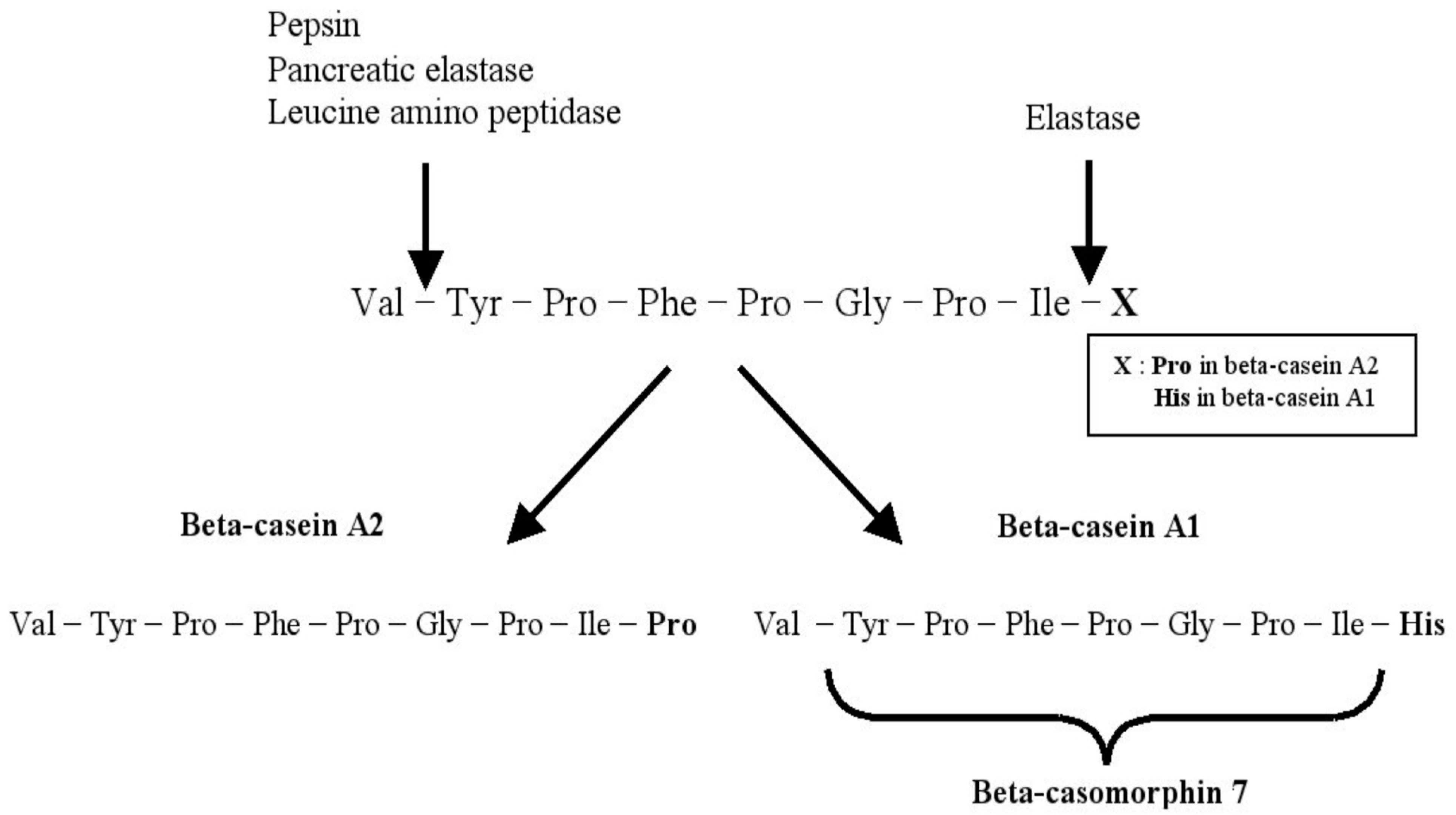

2. Beta-Casein Genetic Variants and Polymorphism

3. Formation of BCM-7, Its Bioactivity and Quantification

4. β-Casein A1 Milk Allergy and Its Symptoms

5. A2 Milk and Goat Milk as a Remedy of CMPA

6. Commercialization of β-CN Polymorphism

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amalfitano, N.; Stocco, G.; Maurmayr, A.; Pegolo, S.; Cecchinato, A.; Bittante, G. Quantitative and qualitative detailed milk protein profiles of 6 cattle breeds: Sources of variation and contribution of protein genetic variants. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11190–11208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Businco, L.; Bellanti, J. Food allergy in childhood. Hypersensitivity to cow’s milk allergens. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1993, 23, 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.W.; Haenlein, G.F.W. Therapeutic and Hypo-Allergenic and Bioactive Potentials of Goat Milk, and Manifestations of Food Allergy. In Handbook of Milk of Non-Bovine Mammals, 2nd ed.; Park, Y.W., Haenlein, G.F.W., Wendorff, W.L., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- Host, A.; Husby, S.; Osterballe, O. A prospective study of cow’s milk allergy in exclusively breast—Fed infants. Acta Paediatr. 1988, 77, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.W. Goat milk-Chemistry and Nutrition. In Handbook of Milk of Non-Bovine Mammals, 2nd ed.; Park, Y.W., Haenlein, G.F.W., Wendorff, W.L., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 42–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi, M.; Mukesh, M.; Kataria, R.S.; Mishra, B.P.; Joshii, B.K. Milk proteins and human health: A1/A2 milk hypothesis. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, P.; Mishra, C.; Mishra, B.; Swain, K.; Rout, M.; Mishra, S.P. Impact of milk protein on human health: A1 verses A2. IJCS 2018, 6, 531–535. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Cade, J.R.; Fregly, M.J.; Privette, R.M. Beta casomorphin induces Fos-like immune reactivity in discrete brain regions relevant to schizophrenia and autism. Autism 1999, 3, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, F.; Buitenhuis, A.J.; Johansson, M.; Bertelsen, H.P.; Glantz, M.; Poulsen, N.A.; Månsson, H.L.; Stålhammar, H.; Larsen, L.B.; Bendixen, C.; et al. Effects of breed and casein genetic variants on protein profile in milk from Swedish Red, Danish Holstein, and Danish Jersey cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 3866–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mclachlan CNS. Beta-casein A1, ischemic heart diseases, mortality and other illnesses. Med. Hypotheses 2001, 56, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Laugesen, M.; Elliott, R. Ischaemic heart disease, Type 1 diabetes, and cow milk A1 beta-casein. N. Z. Med. J. 2003, 116, 1168. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, H.M., Jr.; Jimenez-Flores, R.; Bleck, T.; Brown, M.; Butler, E.; Creamer, K.; Hicks, L.; Hollar, M.; Ng-Kwai-Hang, F.; Swaisgood, E. Nomenclature of the proteins of cows’ milk—Sixth revision. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1641–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Truswell, A.S. The A2 milk case: A critical review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaminski, S.; Cieslinska, A.; Kostyra, E. Polymorphism of bovine beta-casein and its potential effect on human health. J. Appl. Genet. 2007, 48, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.W. Hypo-allergenic and therapeutic significance of goat milk. Small Rumin. Res. 1994, 14, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.W. Goat milk–Chemistry and Nutrition. In Handbook of Milk of Non-Bovine Mammals; Park, Y.W., Haenlein, G.F.W., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 34–58. [Google Scholar]

- Alferez, M.J.M.; Barrionuevo, M.; Aliaga, L.L.; Sampelayo, M.R.S.; Lisbona, F.; Robles, J.C.; Campos, M.S. Digestive utilization of goat and cow milk fat in malabsorption syndrome. J. Dairy Res. 2001, 68, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bevilacqua, C.; Martin, P.; Candalh, C.; Fauquant, J.; Piot, M.; Bouvier, F.; Manfredi, E.; Pilla, F.; Heyman, M. 2000. Allergic sensitization to milk proteins in guinea pigs fed cow milk and goat milks ofdifferent genotypes. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Goats, Tours, France, 14–20 May 2000; Gruner, L., Chabert, Y., Eds.; Institute del Elevage Publ.: Tours, France, 2000; Volume II, pp. 874–879. [Google Scholar]

- Podleski, W.K. Milk protein sensitivity and lactose intolerance with special preference to goat milk. In Proceedings of the V International Conference on Goatss, New Delhi, India, 5–12 May 1992; Volume II, pp. 610–613, Part I. [Google Scholar]

- Caroli, A.M.; Chessa, S.; Erhardt, G.J. Invited review: Milk protein polymorphisms in cattle: Effect on animal breeding and human nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 335–5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrat-Melin, B.; Andersen, P.; Rasmussen, J.T.; Poulsen, N.A.; Larsen, L.B.; Young, J.F. In vitro digestion of purified β-casein variants A 1, A 2, B, and I: Effects on antioxidant and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory capacity. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Givens, I.; Aikman, P.; Gibson, T.; Brown, R. Proportions of A1, A2, B and C β-casein protein variants in retail milk in the UK. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglioti, R.; Gutmanis, G.; Katiki, L.M.; Okino, C.H.; Cristinade, M.; Oliveira, S.; Filho, E.V. New high-sensitive rhAmp method for A1 allele detection in A2 milk samples. Food Chem. 2020, 313, 126167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, M.; Grasset, E.; Duroc, R.; Desjeux, J.F. Antigen absorption by the jejunal epithelium of children with cow’s milk allergy. Pediatr. Res. 1988, 24, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Groves, M.I. Some minor components of casein and other phosphoproteins in milk. A revew. J. Dairy Sci. 1969, 52, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roginski, H. Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences; Academic Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jianqin, S.; Leiming, X.; Lu, X.; Yelland, G.W.; Ni, J.; Clarke, A.J. Effects of milk containing only A2 beta casein versus milk containing both A1 and A2 beta casein proteins on gastrointestinal physiology, symptoms of discomfort, and cognitive behavior of people with self-reported intolerance to traditional cows’ milk. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kostyra, E.; Sienkiewicz-Szapka, E.; Jarmoowska, B.; Krawczuk, S.; Kostyra, H. Opioid peptides derived from milk proteins. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2004, 13, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Johnson, S.K.; Busetti, F.; Solah, V.A. Formation and dedradation of beta-casomorphins in dairy processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 1955–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarmołowska, B.; Bukało, M.; Fiedorowicz, E.; Cieślińska, A.; Kordulewska, N.K.; Moszyńska, M.; Świątecki, A.; Kostyra, E. Role of milk-derived opioid peptides and proline di-peptidyl peptidase-4 in autism. Spectr. Disord. Nutr. 2019, 11, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, H.S.; Doull, F.; Rutherfurd, K.J.; Cross, M.L. Immunoregulatory peptides in bovine milk. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisel, H.; Bockelmann, W. Bioactive peptides encrypted in milk proteins: Proteolytic activation and thropho-functional properties. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1999, 76, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwig, A.; Teschemacher, H.; Lehmann, W.; Gauly, M.; Erhardt, G. Influence of genetic polymorphisms in bovine milk on the occurrence of bioactive peptides. International. Dairy Federation. 1997, 2, 459–460. [Google Scholar]

- Jinsmaa, Y.; Yoshikawa, M. Enzymatic release of neocasomorphin and beta-casomorphin from bovine beta-casein. Peptides 1999, 20, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieoelinska, A.; Kaminski, S.; Kostyra, E.; Sienkiewicz-Sz3apka, E. Beta-casomorphin 7 in raw and hydrolysed milk derived from cows of alternative β-casein genotypes. Milchwissenschaft 2007, 62, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Busetti, F.; Johnson, G.S.S.K.; Solah, V.A. Release of beta-asomorphins during in-vitro gastrointestinal digestion of reconstituted milk after heat treatment. LWT 2021, 136, 110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, A.H.N.; Zaros, L.G.; Lima, T.C.; Borba, L.H.F.; Novaes, L.P.; Mota, L.F.M.; Silva, M.S. Polymorphism in the Beta Casein Gene and analysis of milk characteristics in Gir and Guzerá dairy cattle. Genet. Mol. Res. 2017, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlenkamp, M.R.; Warthesen, J.J. β-Casomorphins: Analysis in cheese and susceptibility to Proteolytic enzymes from Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris. J. Dairy Sci. 1996, 79, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudry, K.D.; Lohner, S.; Schmucker, C.; Kapp, P.; Motschall, E.; Hörrlein, S.; Röger, C.; Meerpohl, J.J. Milk A1β-casein and health-related outcomes in humans: A systematic re-view. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 278–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, R.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liu, S.; Ding, J.; Xu, K.; Meng, H. Identification of alleles and genotypes of beta-casein with DNA sequencing analysis in Chinese Holstein cow. J. Dairy Res 2016, 83, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tailford, K.A.; Berry, C.L.; Thomas, A.C.; Campbell, J.H. A casein variant in cow’s milk is atherogenic. Atherosclerosis 2003, 170, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, J.S.L.; McRae, J.L.; Kukuljan, S.; Woodford, K.; Elliott, R.B.; Swinbum, B.; Dwyer, K.M. A1 beta-casein milk protein and other environmental pre-dis-posing factors for type 1 diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, M.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Z.Q.; Yang, Y.X. Effects of cow’s milk beta-casein variants on symptoms f milk intolerance in Chinese adults: A multi-centre, randomised controlled study. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliott, R.B.; Harris, D.P.; Hill, J.P.; Bibby, N.J.; Wasmuth, H.E. Type I (insulindependent) diabetes mellitus and cow milk: Casein variant consumption. Diabetologia 42: 292–296. Atherosclerosis 1999, 170, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.J.; Grochoski, G.T.; Clarke, A.J. Health implications of milk containing beta-casein with the A2 genetic variant. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 46, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Chauhan, G.; Mishra, B.P.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Pattanaik, A.K.; Singh, T.U.; Karikalan, M.; Meshram, S.K.; Garg, L. Comparative evaluation of feeding effects of A1 and A2 cow milk derived casein hydrolysates in diabetic model of rats. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cade, R.; Privette, R.; Fregly, M.; Rowland, N.; Sun, Z.; Zele, V. Autism and schizophrenia: Intestinal disorders. Nutr. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestle; Nestlé Health Science—Global Headquarters: Vevey, Switzerland, 2020.

- Haenlein, G.F.W.; Caccese, R. Goat milk versus cow milk. In Extension Goat Handbook; Haenlein, G.F.W., Ace, D.L., Eds.; USDA Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, W.A. Pathology of intestinal uptake and absorption of antigens in food allergy. Ann. Allergy 1987, 59, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soothill, J.F. Slow Food Allergic Disease. Food Allergy; Chandra, R.K., Ed.; Nutrition Research Education Found: St. John’s, Canada, 1987; pp. 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Haenlein, G.F.W. Goat milk in human nutrition. Small Rumin. Res. 2004, 51, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, A.; Hassoun, S.; Drouet, M. L’allergie au lait de vache et sa substitution par le lait de chevre. In Proceedings, Colloque Interets Nutritionnel et Dietetique du Lait de Chevre; Inst. Nat. Rech. Agron. Publ.: Paris, France, 1997; pp. 111–118, No. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Fabre, A. Perspectives actuelles d’utilisation du lait de chevre dans l’alimentation infantile. In Proceedings, Colloque Interets Nutritionnel et Dietetique du Lait de Chevre; Inst. Nat. Rech. Agron. Publ.: Paris, France, 1997; pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, P.; Fabre, A. Utilisation du lait de chevre chez l’enfant. Experience de Creteil. In Proceedings, Colloque Interets Nutritionnel et Dietetique du Lait de Chevre; Inst. Nat. Rech. Agron. Publ.: Paris, France, 1997; pp. 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, E. Personal Communication. 2017. Available online: www.ellie.Krieger.com (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- CRF. California Research Foundation. 2017. Available online: http:/cdrf.org/2017/02/09/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Triple—Hil Sires. Dun-Did Bush Wacker. Farmshine, 41(20):3. USDA, DHIA 1980. Annual Report of Official Dairy Herd Testing Participation; USDA Publ.: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, D. A2 milk: Is it really better for you? Holstein. Hub. 2018, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- A2 Corporation. 2006. Available online: http://www.a2corporation.com/index.php/ps_pagename/corporate (accessed on 10 September 2020).

| Proteins | Cow | Goat | Human |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (%) | 3.3 | 3.5 | 1.2 |

| Total casein (g/100 mL) | 2.70 | 2.11 | 0.40 |

| αs1 (% of total casein) | 38.0 | 5.6 | --- |

| αs2 (% of total casein) | 12.0 | 19.2 | --- |

| β (% of total casein) | 36.0 | 54.8 | 60–70.0 |

| κ (% of total casein) | 14.0 | 20.4 | 7.0 |

| Whey protein (%) (albumin and globulin) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Beta-Casein Variants | Changes in Amino Acid Sequence | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 25 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 67 | 72 | 88 | 93 | 106 | 117 | 122 | 137 | 138 | |

| A2 | Ser-P | Arg | Ser-P | Glu | Glu | Pro | Glu | Leu | Gln | His | Gln | Ser | Leu | Pro |

| A1 | His | |||||||||||||

| A3 | Gln | |||||||||||||

| B | His | Arg | ||||||||||||

| C | Ser | Lys | His | |||||||||||

| D | Lys | |||||||||||||

| E | Lys | |||||||||||||

| F | His | Leu | ||||||||||||

| G | His | Leu | ||||||||||||

| H1 | Cys | Ile | ||||||||||||

| H2 | Glu | Leu | Glu | |||||||||||

| I | Leu | |||||||||||||

| β-CN Variant | tpep (min) 2 | tpan (min) 3 | DH (%) 4 | MLP 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A 1 | 60 | 0 | 3.6 ± 0.42 a | 27.6 ± 3.01 |

| A 2 | 60 | 0 | 3.2 ± 0.20 a | 31.5 ± 2.20 |

| B | 60 | 0 | 3.6 ± 0.22 a | 28.0 ± 1.95 |

| I | 60 | 0 | 2.6 ± 0.17 a | 37.6 ± 2.46 |

| A 1 | 60 | 5 | 20.4 ± 1.71 b | 4.9 ± 0.42 |

| A 2 | 60 | 5 | 21.5 ± 2.47 b | 4.6 ± 0.55 |

| B | 60 | 5 | 20.2 ± 0.89 b | 5.0 ± 0.20 |

| I | 60 | 5 | 19.4 ± 1.38 b | 5.2 ± 0.33 |

| A 1 | 60 | 120 | 55.0 ± 5.99 c | 1.8 ± 0.21 |

| A 2 | 60 | 120 | 52.4 ± 5.54 c | 1.9 ± 0.19 |

| B | 60 | 120 | 46.2 ± 3.98 c | 2.2 ± 0.16 |

| I | 60 | 120 | 49.9 ± 4.24 c | 2.0 ± 0.17 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, Y.W.; Haenlein, G.F.W. A2 Bovine Milk and Caprine Milk as a Means of Remedy for Milk Protein Allergy. Dairy 2021, 2, 191-201. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy2020017

Park YW, Haenlein GFW. A2 Bovine Milk and Caprine Milk as a Means of Remedy for Milk Protein Allergy. Dairy. 2021; 2(2):191-201. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy2020017

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Young W., and George F. W. Haenlein. 2021. "A2 Bovine Milk and Caprine Milk as a Means of Remedy for Milk Protein Allergy" Dairy 2, no. 2: 191-201. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy2020017

APA StylePark, Y. W., & Haenlein, G. F. W. (2021). A2 Bovine Milk and Caprine Milk as a Means of Remedy for Milk Protein Allergy. Dairy, 2(2), 191-201. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy2020017