UV–Vis Spectra of Gold(III) Complexes with Different Halides, Hydroxide, and Ammonia According to TD-DFT Calculations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. What Are the Experimental Spectra?

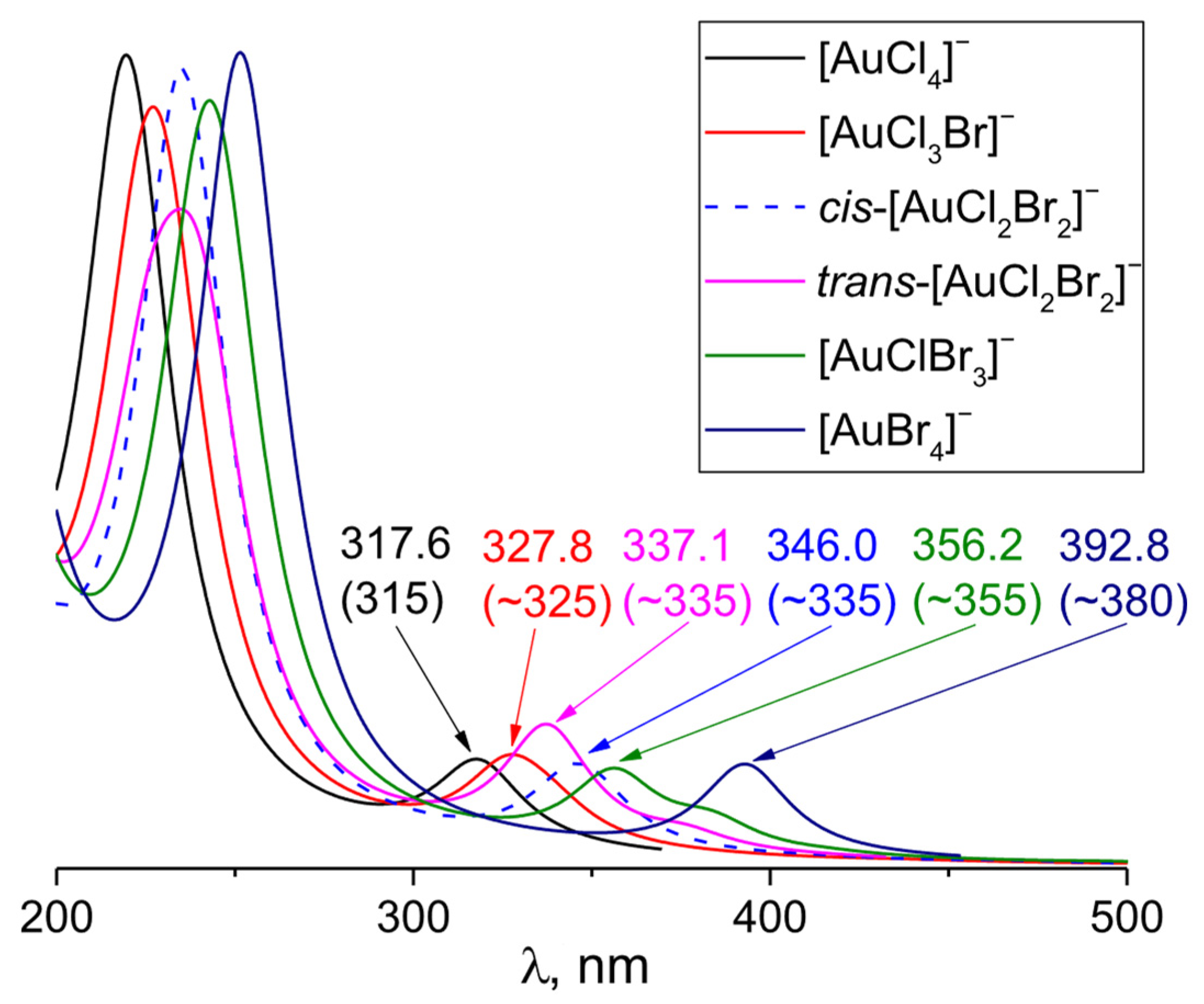

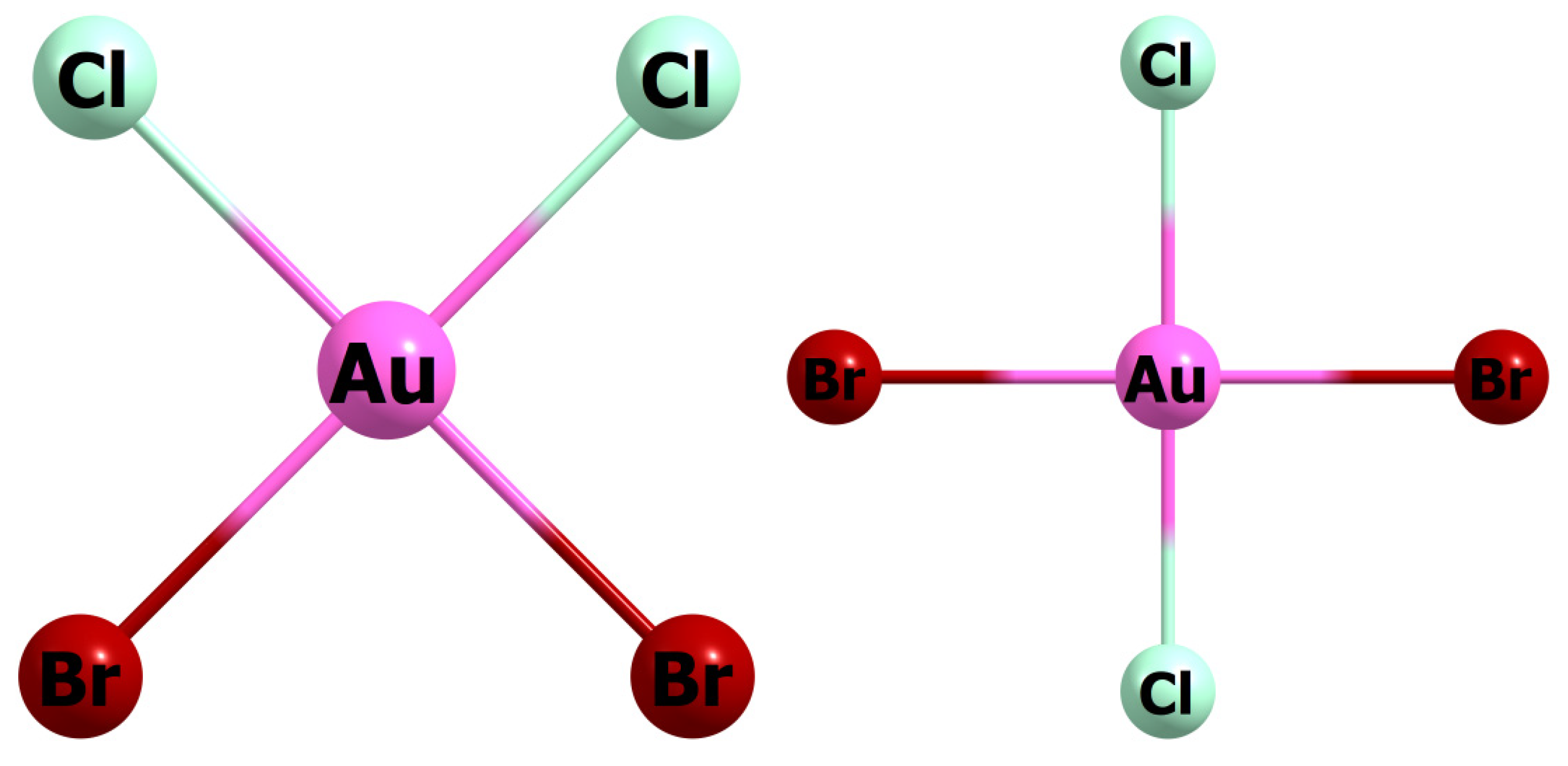

3.2. [AuCl4−nBrn]− (n varies from 1 to 4)

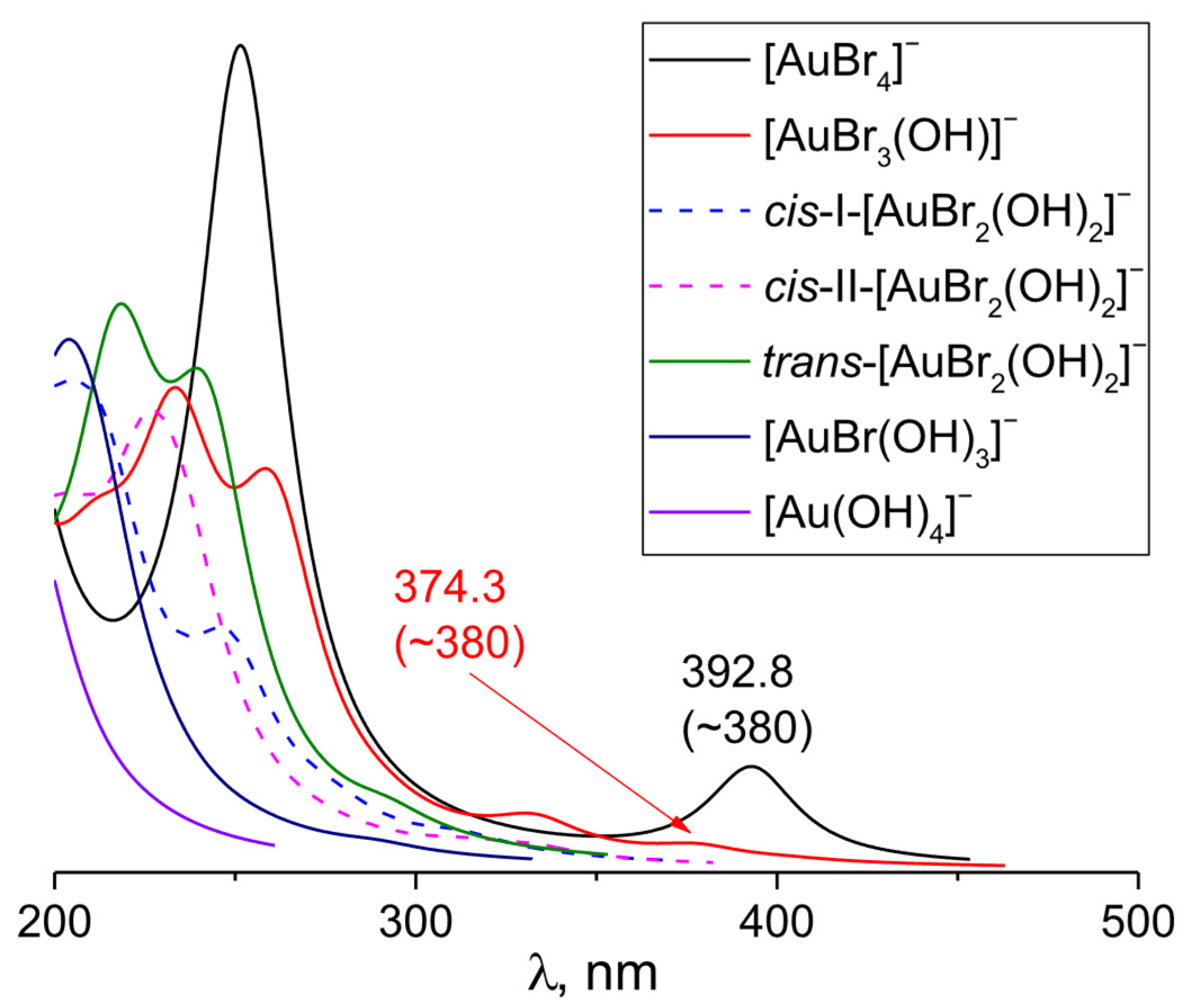

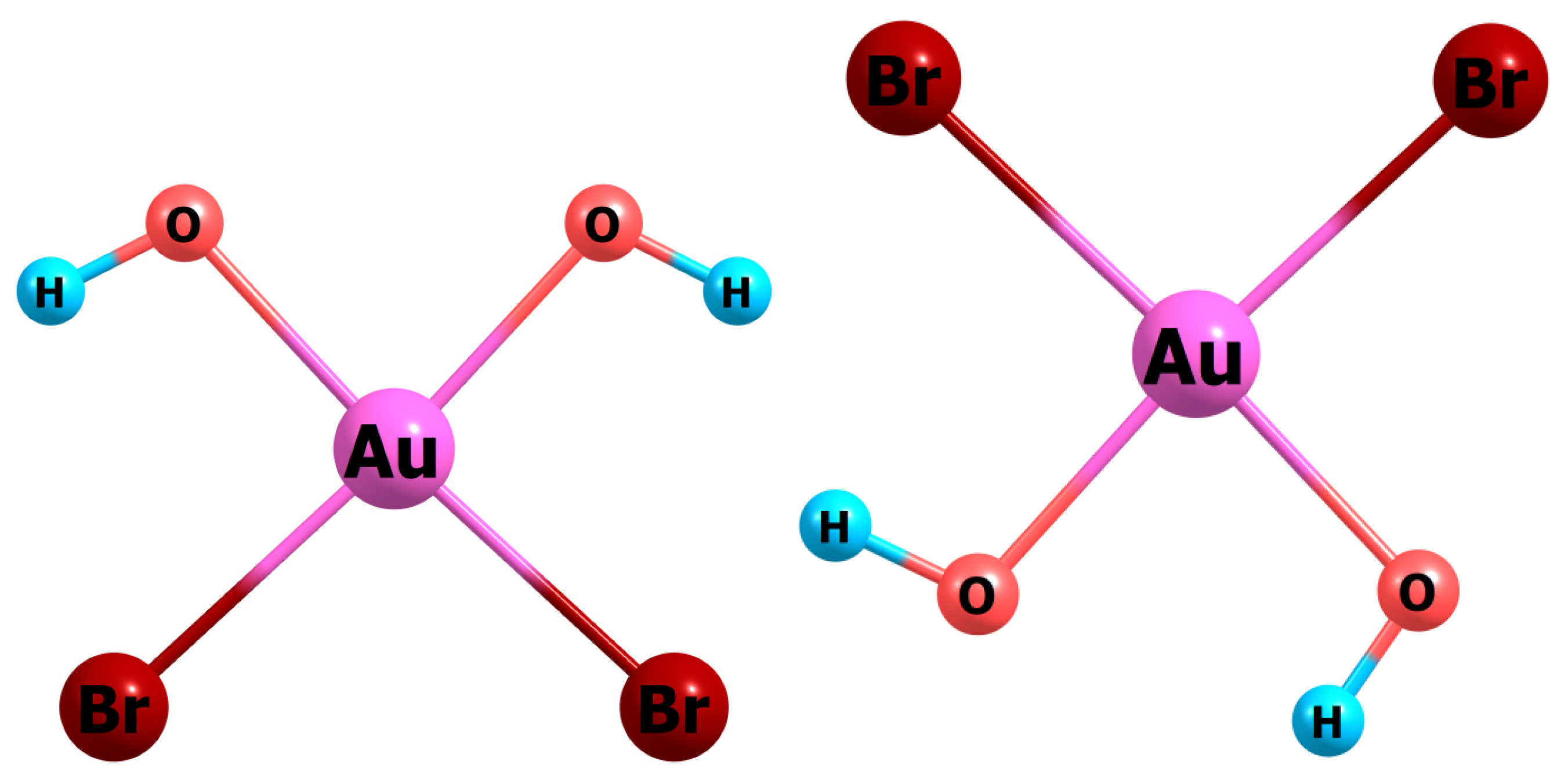

3.3. [AuBr4−n(OH)n]− (n Varies from 1 to 4)

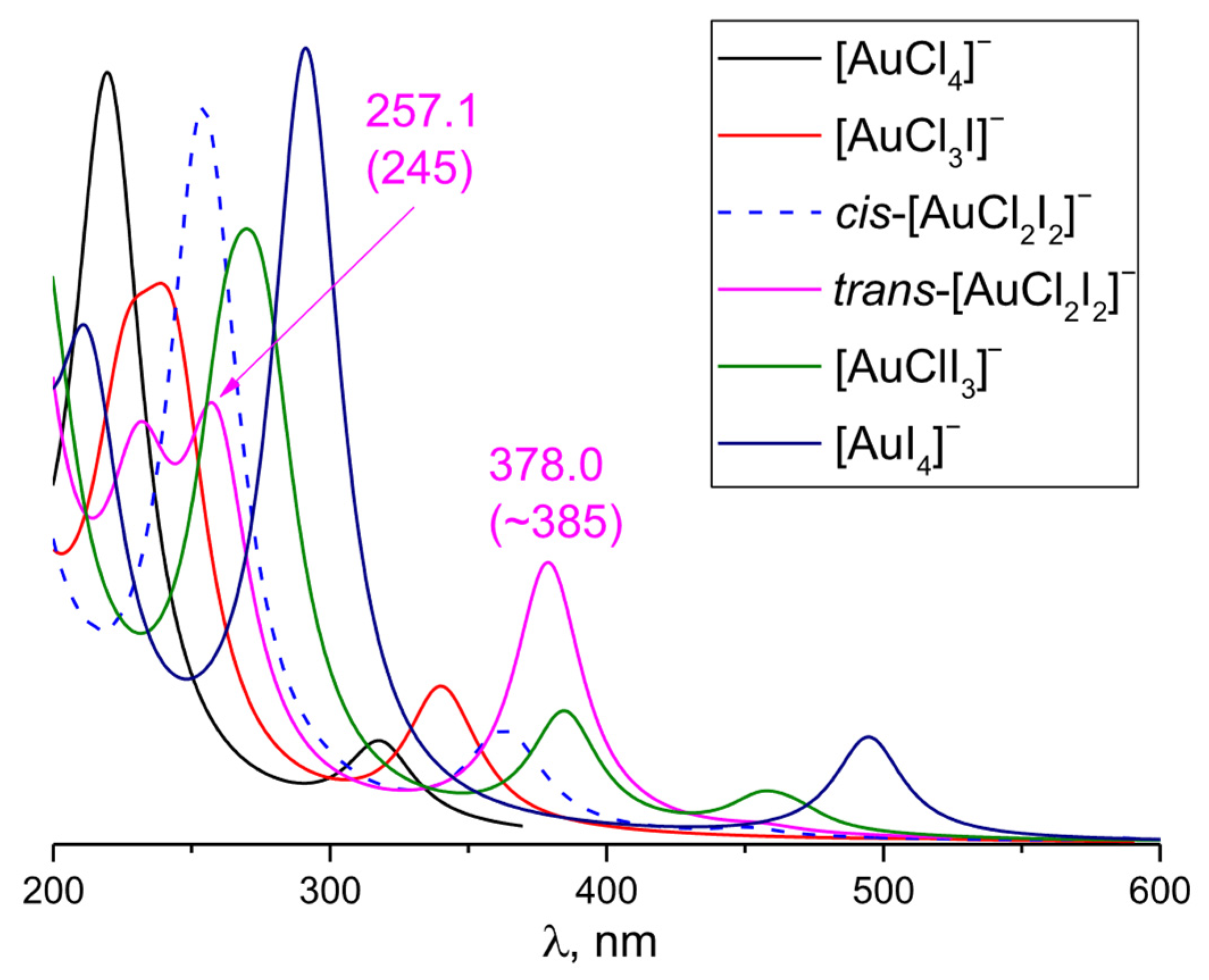

3.4. [AuCl4−nIn]− (n Varies from 1 to 4)

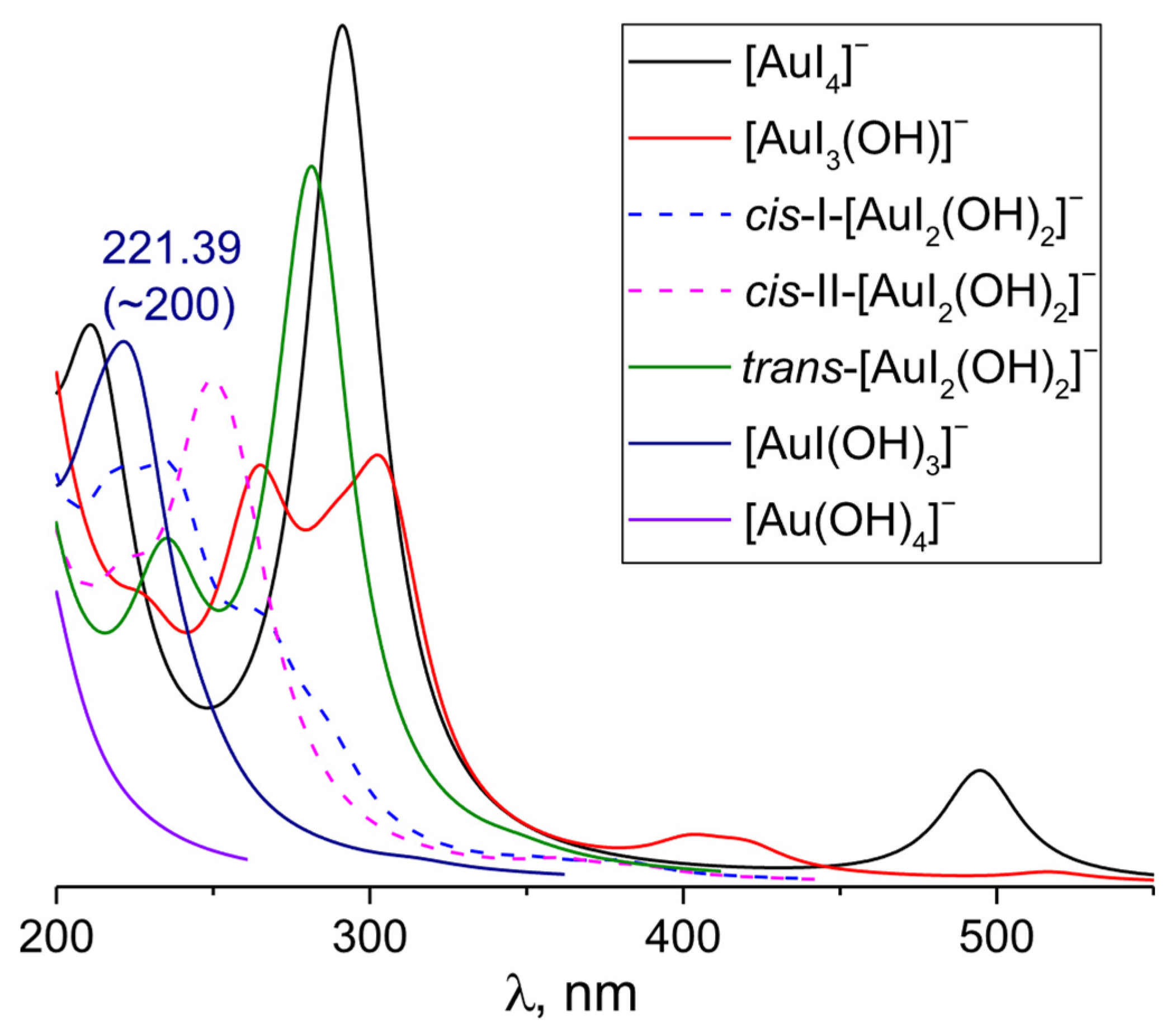

3.5. [AuI4−n(OH)n]− (n varies from 1 to 4)

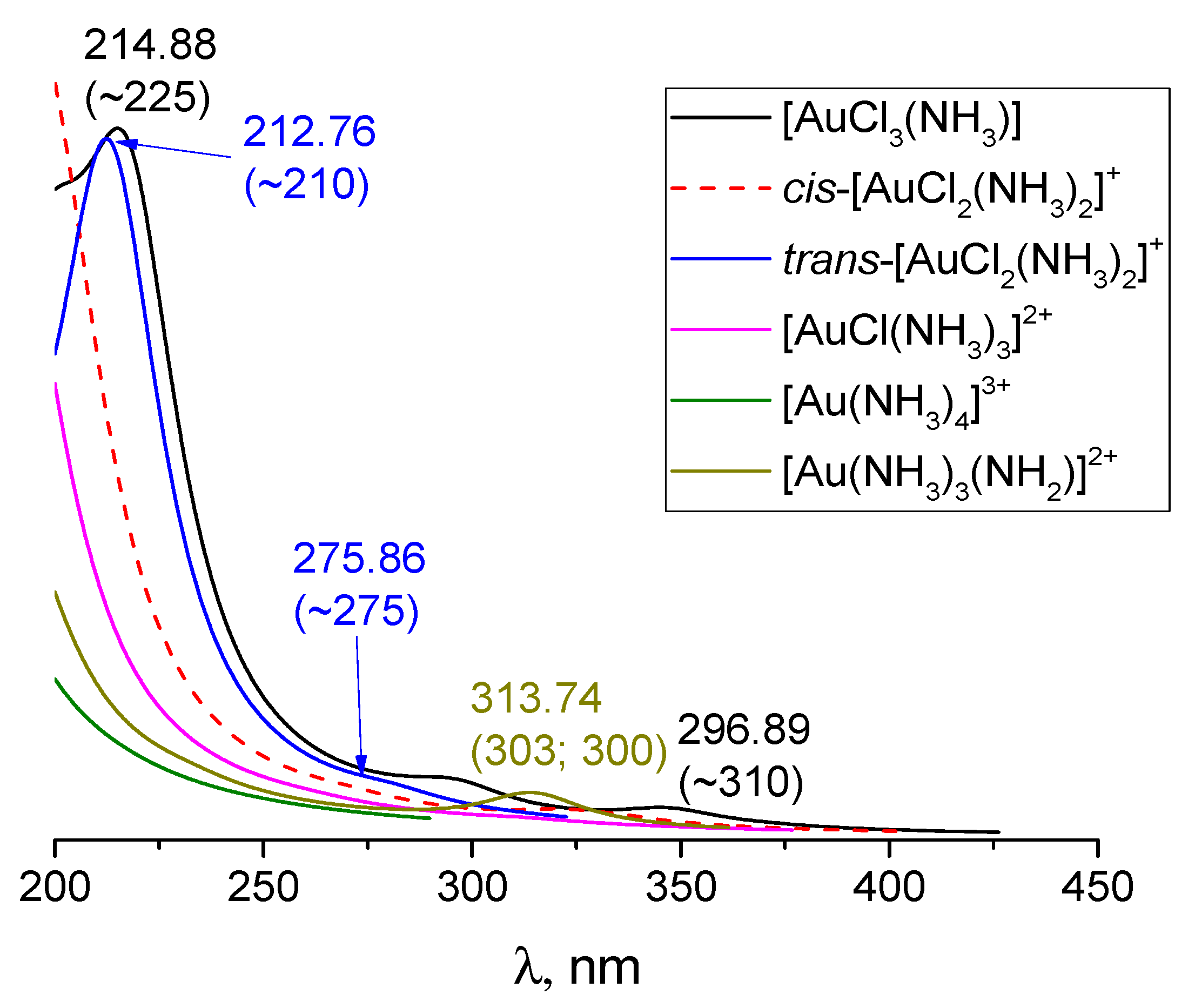

3.6. [AuCl3(NH3)], [Au(NH3)4]3+ and [Au(NH3)3(NH2)]2+

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UV–Vis | Ultraviolet and visible |

| TD-DFT | Time-dependent density functional theory |

| RECPs | Relativistic electron core potentials |

| PCM | Polarizable continuum model |

| RHF | Restricted Hartree–Fock |

| CISD | Single and double excitations |

| LSQ | Least squares method |

| LMCT | Ligand-metal charge transfer |

| HOMO | Highest occupied molecular orbital |

| LUMO | Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital |

References

- Đurović, M.D.; Bugarčić, Ž.D.; Van Eldik, R. Stability and Reactivity of Gold Compounds–From Fundamental Aspects to Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 338, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, H.E.; Mohamed, A.A.; Fackler, J.P.; Burini, A.; Galassi, R.; López-de-Luzuriaga, J.M.; Olmos, M.E. Structures and Properties of Gold(I) Complexes of Interest in Biochemical Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.-M.; Sun, R.W.-Y. Therapeutic Applications of Gold Complexes: Lipophilic Gold(Iii) Cations and Gold(i) Complexes for Anti-Cancer Treatment. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Alcántar, G.; Picchetti, P.; Casini, A. Gold Complexes in Anticancer Therapy: From New Design Principles to Particle-Based Delivery Systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202218000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richert, M.; Mikstacka, R.; Walczyk, M.; Cieślak, M.J.; Kaźmierczak-Barańska, J.; Królewska-Golińska, K.; Muzioł, T.M.; Biniak, S. Gold(I) Complexes with P-Donor Ligands and Their Biological Evaluation. Processes 2021, 9, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glišić, B.Đ.; Djuran, M.I. Gold Complexes as Antimicrobial Agents: An Overview of Different Biological Activities in Relation to the Oxidation State of the Gold Ion and the Ligand Structure. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 5950–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratia, C.; Sueiro, S.; Soengas, R.G.; Iglesias, M.J.; López-Ortiz, F.; Soto, S.M. Gold(III) Complexes Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria of Veterinary Significance. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shareena Dasari, T.P.; Deng, H.; Yu, H. Antimicrobial Activity of Gold Nanoparticles and Ionic Gold. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2015, 33, 286–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elie, B.T.; Levine, C.; Ubarretxena-Belandia, I.; Varela-Ramírez, A.; Aguilera, R.J.; Ovalle, R.; Contel, M. Water-Soluble (Phosphane)Gold(I) Complexes–Applications as Recyclable Catalysts in a Three-Component Coupling Reaction and as Antimicrobial and Anticancer Agents. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 2009, 3421–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrakdar, T.A.C.A.; Scattolin, T.; Ma, X.; Nolan, S.P. Dinuclear Gold(i) Complexes: From Bonding to Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 7044–7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, A.; Sadowski, M.; Jasiński, R. Selectivity and Molecular Mechanism of the Au(III)-Catalyzed [3+2] Cycloaddition Reaction between (Z)-C,N-Diphenylnitrone and Nitroethene in the Light of the Molecular Electron Density Theory Computational Study. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2024, 60, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, C.; Reith, F.; Brugger, J.; Pring, A.; Lenehan, C.E. Analysis of Gold(I/III)-Complexes by HPLC-ICP-MS Demonstrates Gold(III) Stability in Surface Waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 5737–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugger, J.; Liu, W.; Etschmann, B.; Mei, Y.; Sherman, D.M.; Testemale, D. A Review of the Coordination Chemistry of Hydrothermal Systems, or Do Coordination Changes Make Ore Deposits? Chem. Geol. 2016, 447, 219–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, I.V.; Tsvelodub, L.D. Chlorohydroxocomplexes of gold(III) in aqueous alkaline solutions. Zhurn. Neorg. Khim. 2000, 45, 706–711. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, A.; McPhail, D.C.; Brugger, J. A Spectrophotometric Study of Aqueous Au(III) Halide–Hydroxide Complexes at 25–80 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 3359–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurović, M.D.; Puchta, R.; Bugarčić, Ž.D.; Van Eldik, R. Studies on the Reactions of [AuCl4]− with Different Nucleophiles in Aqueous Solution. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 8620–8632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasic, V.; Premovic, S.; Cakar, M.; Radak, B.; Milovanovic, G. Spectrophotometric Investigations of the Reaction between Gold(III) and Potassium Iodide. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2000, 65, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalishin, M.N.; Pimenov, O.A.; Belov, K.V.; Khodov, I.A.; Gamov, G.A. Chemical Equilibria in Aqueous Solutions of H[AuCl4] and Bovine or Human Serum Albumin. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 389, 122914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, T.; Tew, D.P.; Handy, N.C. A New Hybrid Exchange–Correlation Functional Using the Coulomb-Attenuating Method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalmani, G.; Frisch, M.J.; Mennucci, B.; Tomasi, J.; Cammi, R.; Barone, V. Geometries and Properties of Excited States in the Gas Phase and in Solution: Theory and Application of a Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory Polarizable Continuum Model. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 094107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figgen, D.; Rauhut, G.; Dolg, M.; Stoll, H. Energy-Consistent Pseudopotentials for Group 11 and 12 Atoms: Adjustment to Multi-Configuration Dirac–Hartree–Fock Data. Chem. Phys. 2005, 311, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.A.; Puzzarini, C. Systematically Convergent Basis Sets for Transition Metals. II. Pseudopotential-Based Correlation Consistent Basis Sets for the Group 11 (Cu, Ag, Au) and 12 (Zn, Cd, Hg) Elements. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2005, 114, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.A.; Figgen, D.; Goll, E.; Stoll, H.; Dolg, M. Systematically Convergent Basis Sets with Relativistic Pseudopotentials. II. Small-Core Pseudopotentials and Correlation Consistent Basis Sets for the Post-d Group 16–18 Elements. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 11113–11123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T.H. Gaussian Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations. I. The Atoms Boron through Neon and Hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woon, D.E.; Dunning, T.H. Gaussian Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations. III. The Atoms Aluminum through Argon. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F. Error of Relativistic Effective Core Potentials for Closed-Shell Diatomic Molecules of p-Block Heavy and Superheavy Elements in DFT and TDDFT Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 159, 244107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roothaan, C.C.J. New Developments in Molecular Orbital Theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1951, 23, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pople, J.A.; Seeger, R.; Krishnan, R. Variational Configuration Interaction Methods and Comparison with Perturbation Theory. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1977, 12, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemcraft-Graphical Program for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations. Available online: https://www.chemcraftprog.com/ (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Meshkov, A.N.; Gamov, G.A. KEV: A Free Software for Calculating the Equilibrium Composition and Determining the Equilibrium Constants Using UV–Vis and Potentiometric Data. Talanta 2019, 198, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouradier, J.; Coquard, M. Électrochimie Des Sels d’or: V.—Complexes Mixtes Aurichlorobromure. J. Chim. Phys. 1966, 63, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshchevitskii, B.I.; Belevantsev, V.I. Constants of substitution of Cl− by Br− in [AuCl4]−. Zhurn. Neorg. Khim. 1967, 12, 312–318. [Google Scholar]

- Almgren, L.; Nicholson, D.G.; Kimland, B.; Enzell, C.R.; Lousberg, R.J.J.C.; Weiss, U. The Stability Constants of Mixed Chloro-Bromo-Aurate(III) Complexes. Acta Chem. Scand. 1971, 25, 3713–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Elding, L.I.; Gröning, A.-B.; Summerville, D.A.; Almenningen, A.; Bastiansen, O.; Fernholt, L.; Gundersen, G.; Nielsen, C.J.; Cyvin, B.N.; Cyvin, S.J. Kinetics, Mechanism and Equilibria for Halide Substitution Processes of Chloro Bromo Complexes of Gold(III). Acta Chem. Scand. 1978, 32a, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tsuchida, R. Absorption Spectra of Co-Ordination Compounds. I. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1938, 13, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammreich, H.; Forneris, R. Raman Spectra and Force Constants of Planar Square Molecules of the Type AB4. Spectrochim. Acta 1960, 16, 363–367, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, W.R.; Gray, H.B. Electronic Structures and Spectra of Square-Planar Gold(III) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1968, 7, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makotchenko, E.V.; Baidina, I.A.; Korol’kov, I.V. Structure of Diethylenetriammonium Tetrabromoaurates(III). J. Struct. Chem. 2014, 55, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efremov, A.N.; Sharutin, V.V.; Sharutina, O.K.; Andreev, P.V.; Eltsov, O.S. Synthesis and Structure of Methyltriphenylphosphonium Dicyanodibromoaurate [Ph3PCH3] [Au(CN)2Br2]. IVKKT 2020, 63, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinskii, V.I.; Shul’man, V.M.; Peshchevitskii, B.I. Stability of Tetrachloroaurate(III) and Tetrabromoaurate(III) in Aqueous Solution. Zhurn. Neorg. Khim. 1968, 13, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, W.J.; Robb, W. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Reactions of Gold(III) Complexes. II. The Formation and Equilibrium Hydrolysis of Tetrabromoaurate(III). Inorg. Chim. Acta 1974, 9, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isart, C.; Burés, J.; Vilarrasa, J. Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectra of the Reactions of NaAuBr 4 and Related Aurates with Nucleophiles: JMS Letters. J. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 49, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skibsted, L.H.; Bjerrum, J.; Frederichsen, P.S.; Nakken, K.F. Studies on Gold Complexes. I. Robustness, Stability and Acid Dissociation of the Tetramminegold(III) Ion. Acta Chem. Scand. 1974, 28, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, I.V. About the Stability of Au(NH3) 4 3+ in Aqueous Solution. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 53, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, I.V.; Tsvelodub, L.D. Equilibria of Cl- substitution by ammonia, ethylenediamine, diethylenetriamine in AuCl4-complex in aqueous solution. Zhurn. Neorg. Khim. 2000, 45, 425–430. [Google Scholar]

- Ventegodt, J.; Øby, B.; Skibsted, L.H.; Dietzsch, W.; Hoyer, E. Amineanionogold(III) Complexes. V. Kinetics of the Consecutive Substitutions of Ammonia by Chloride in Tetraamminegold(III) Ion in Acidic Aqueous Solution. Acta Chem. Scand. 1985, 39a, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Logacheva, O.I.; Pimenov, O.A.; Gamov, G.A. UV–Vis Spectra of Gold(III) Complexes with Different Halides, Hydroxide, and Ammonia According to TD-DFT Calculations. Chemistry 2026, 8, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry8010003

Logacheva OI, Pimenov OA, Gamov GA. UV–Vis Spectra of Gold(III) Complexes with Different Halides, Hydroxide, and Ammonia According to TD-DFT Calculations. Chemistry. 2026; 8(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry8010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleLogacheva, Olga I., Oleg A. Pimenov, and George A. Gamov. 2026. "UV–Vis Spectra of Gold(III) Complexes with Different Halides, Hydroxide, and Ammonia According to TD-DFT Calculations" Chemistry 8, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry8010003

APA StyleLogacheva, O. I., Pimenov, O. A., & Gamov, G. A. (2026). UV–Vis Spectra of Gold(III) Complexes with Different Halides, Hydroxide, and Ammonia According to TD-DFT Calculations. Chemistry, 8(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry8010003