How Are Discoveries in Chemistry Made? Insight from Three Discoveries and Their Impact

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

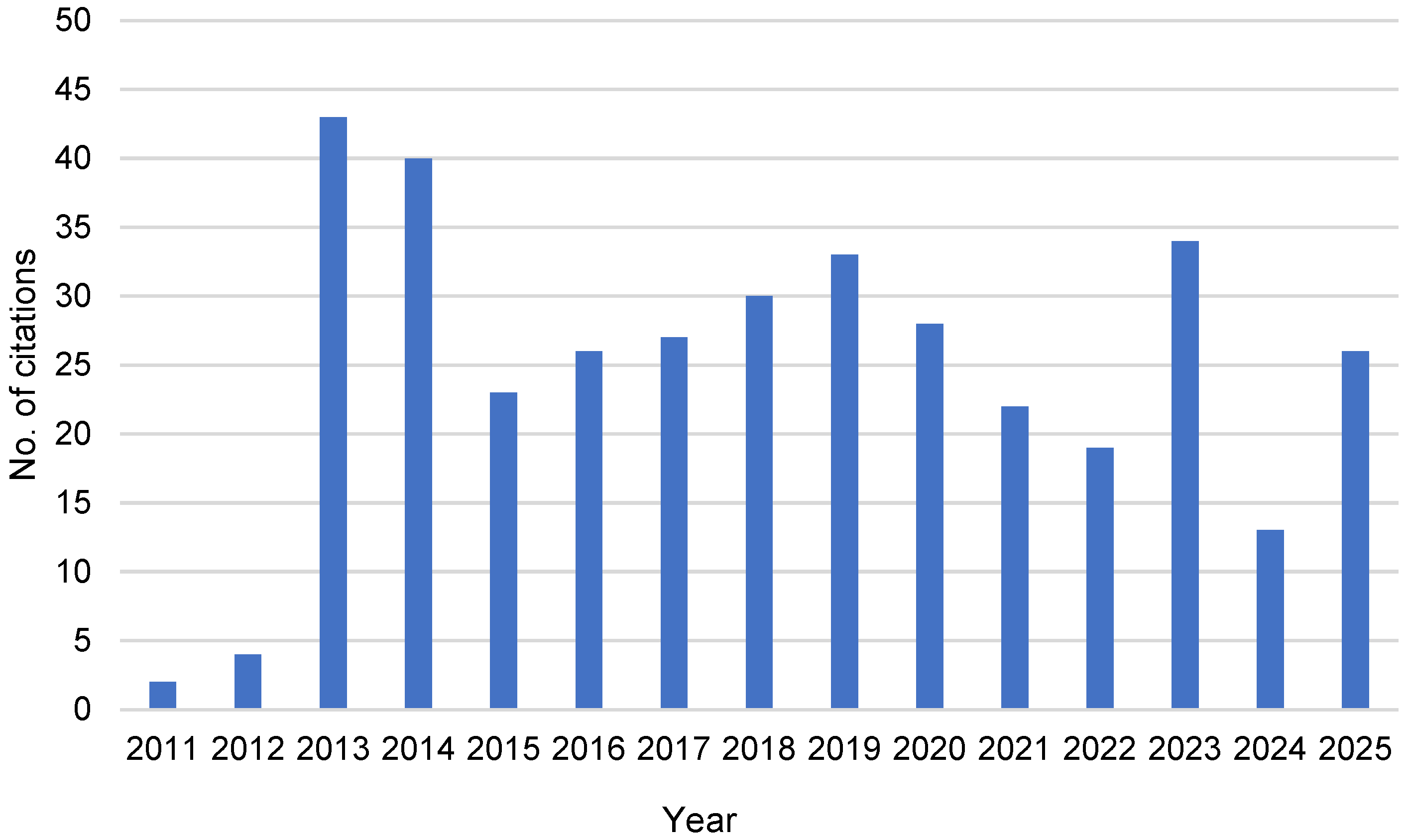

3.1. Cocktail-Type Catalysis

“Heterogenization of the molecular precatalyst to palladium nanoparticles and subsequent dissolution of palladium atoms from these nanoparticles constitutes a model that accounts for all of the observations detailed above. Such a model has been suggested, although only rarely underpinned with experimental evidence.”[14]

“The “Cocktail”-type catalysis gives rise to a new way of thinking. Rather than fighting complexity, it embraces it. This approach is helping chemists design better, more flexible catalytic systems—ones that work under challenging conditions, require less metal, and offer greater control over reactivity and selectivity. It is a dynamic, cooperative view of catalysis that opens the door to next-generation technologies in sustainable chemistry and industrial applications”.[17]

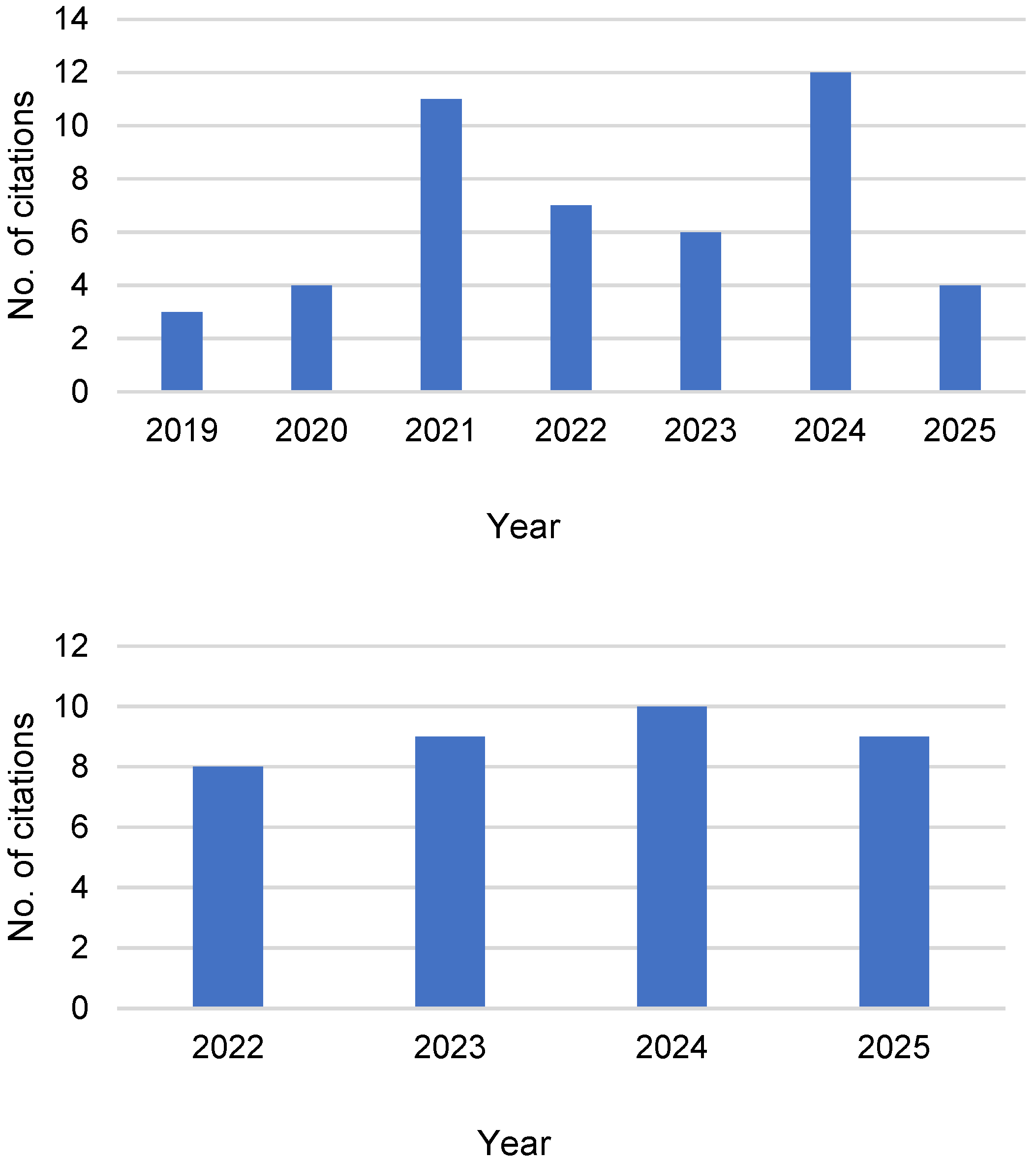

3.2. The LimoFish Process

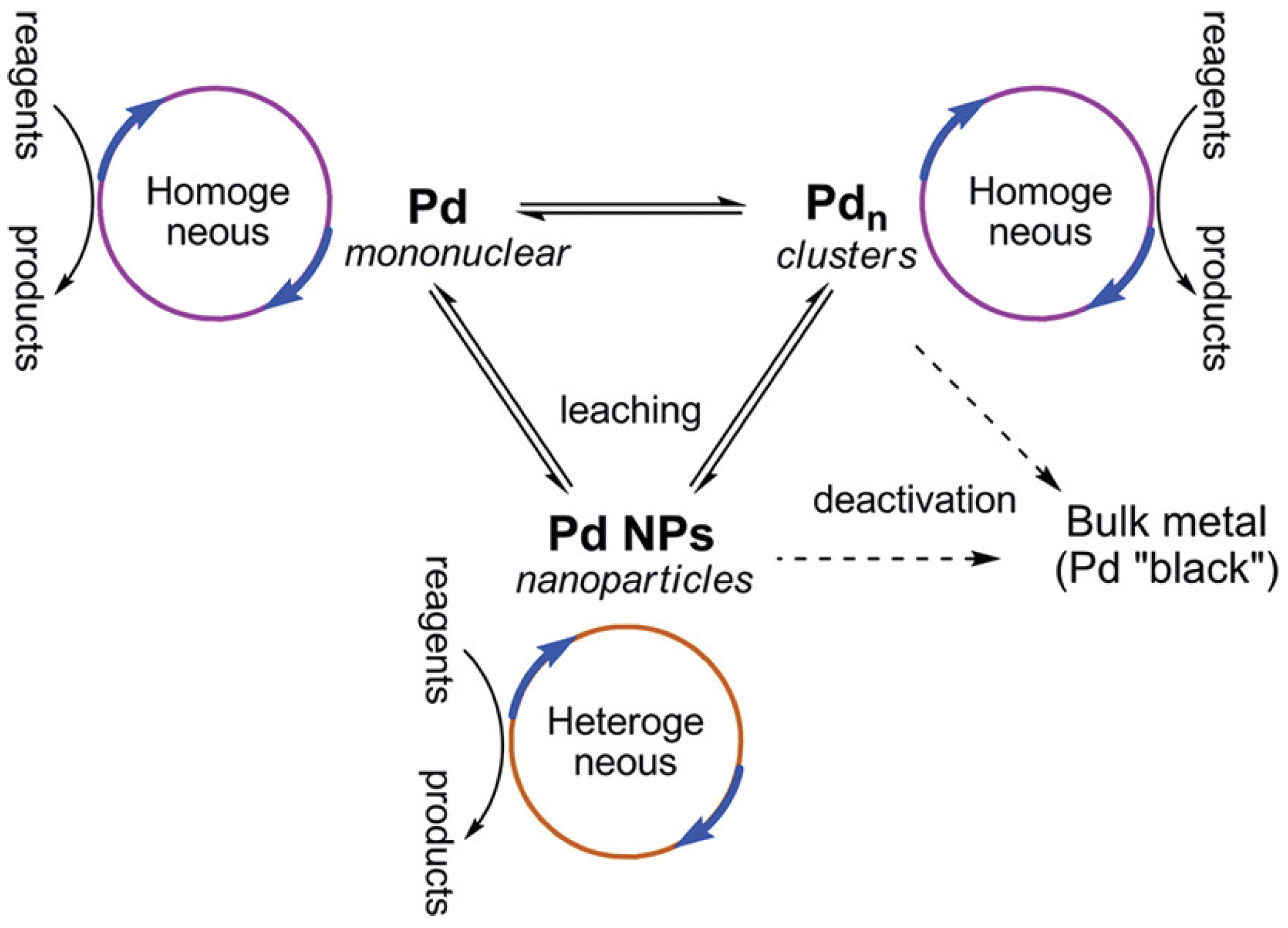

3.3. Molecularly Doped Metals

“The study of molecularly doped metals is a relatively new area of materials science, where metals may be used to entrap soft matter, such as polymers… During molecular doping, molecules may be encapsulated within a metal, creating a dopant-metal structure with far stronger interactions than metal with adsorbed polymer…”.[46]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Aftalion, F. A History of the International Chemical Industry; Chemical Heritage Foundation: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A. Rulev, Serendipity or the art of making discoveries. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 4262–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoye, E. Chemists Don’t Think Their Field is Innovative Enough. Chemstry World. 2017. Available online: https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/chemists-dont-think-their-field-is-innovative-enough/3008140.article (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Hoctor, T. 2017; Cit. In Ref.3.

- Prima, D.O.; Kulikovskaya, N.S.; Galushko, A.S.; Mironenko, R.M.; Ananikov, V.P. Transition metal ‘cocktail’-type catalysis. Curr. Op. Green Sust. Chem. 2021, 31, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzone, D.M.; Angellotti, G.; Carabetta, S.; Di Sanzo, R.; Russo, M.; Mauriello, F.; Ciriminna, R.; Pagliaro, M. The LimoFish circular economy process for the marine bioeconomy. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avnir, D. Molecularly doped metals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Della Pina, C.; Luque, R.; Pagliaro, M. Altmetrics in chemistry: Alternative metrics for research impact in chemistry. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; López-Cózar, E.D. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J. Informetr. 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalesskiy, S.S.; Ananikov, V.P. Pd2(dba)3 as a precursor of soluble metal complexes and nanoparticles: Determination of palladium active species for catalysis and synthesis. Organometallics 2012, 31, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananikov, V.P.; Beletskaya, I.P. Toward the ideal catalyst: From atomic centers to a “cocktail” of catalysts. Organometallics 2012, 31, 1595–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvela, R.K.; Leadbeater, N.E.; Sangi, M.S.; Williams, V.A.; Granados, P.; Singer, R.D. A reassessment of the transition-metal free Suzuki-type coupling methodology. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Search conducted at https://scholar.google.com/ accessed on 6 November 2025.

- Canseco-Gonzalez, D.; Gniewek, A.; Szulmanowicz, M.; Müller-Bunz, H.; Trzeciak, A.M.; Albrecht, M. PEPPSI-type palladium complexes containing basic 1,2,3-triazolylidene ligands and their role in Suzuki–Miyaura catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6055–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentsak, E.O.; Eremin, D.B.; Gordeev, E.G.; Ananikov, V.P. Phantom reactivity in organic and catalytic reactions as a consequence of microscale destruction and contamination-trapping effects of magnetic stir bars. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 3070–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enikolopov Institute of Synthetic Polymeric Materials. Discovery and development of “cocktail”-type catalysis. In Proceedings of the New Horizons of Catalysis and Organic Chemistry, Moscow, Russia, 19–20 May 2025; Russian Academy of the Sciences: Moscow, Russia, 2025. Available online: https://ispm.ru/en/institute/news/archive/354 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and their health benefits. Ann. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002, 56, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lands, W.E.M. Fish, Omega-3 And Human Health, 2nd ed.; AOCS Publishing: Urbana, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, J.T. The most hidden of all hidden hungers: The global deficiency in DHA and EPA and what to do about it. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, T.H. Global access to uncontaminated omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids requires attention. AJPM Focus 2025, 4, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glencross, B.D.; Bachis, E.; Betancor, M.B.; Calder, P.; Liland, N.; Newton, R.; Ruyter, B. Omega-3 futures in aquaculture: Exploring the supply and demands for long-chain omega-3 essential fatty acids by aquaculture species. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2024, 33, 167–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepon, A.; Makov, T.; Hamilton, H.A.; Müller, D.B.; Gephart, J.A.; Henriksson, P.J.G.; Troell, M.; Golden, C.D. Sustainable optimization of global aquatic omega-3 supply chain could substantially narrow the nutrient gap. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, L.A.; Wabnitz, C.C.C.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Pauly, D.; Sumaila, U.R. Spatial distribution of fishmeal and fish oil factories around the globe. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr6921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Organization for EPA and DHA Omega-3 (GOED). The Global EPA+DHA Omega-3 Finished Products Report; Global Organization for EPA and DHA Omega-3: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2025; Available online: https://goedomega3.com/purchase-data-and-reports/fpr (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Delisi, R.; Pagliaro, M. Enhancing and improving the extraction of omega-3 from fish oil. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2017, 5, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Scurria, A.; Avellone, G.; Pagliaro, M. A circular economy approach to fish oil extraction. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 5106–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurria, A.; Lino, C.; Pitonzo, R.; Pagliaro, M.; Avellone, G.; Ciriminna, R. Vitamin D3 in fish oil extracted with limonene from anchovy leftovers. Chem. Data Collect. 2020, 25, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurria, A.; Tixier, A.-S.F.; Lino, C.; Pagliaro, M.; Avellone, G.; D’Agostino, F.; Chemat, F.; Ciriminna, R. High yields of shrimp oil rich in omega-3 and natural astaxanthin from shrimp waste. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 17500–17505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscolo, A.; Mauriello, F.; Marra, F.; Calabrò, P.S.; Russo, M.; Ciriminna, R.; Pagliaro, M. AnchoisFert: A new organic fertilizer from fish processing waste for sustainable agriculture. Glob. Chall. 2022, 6, 2100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, M.; Lino, C.; Pizzone, D.M.; Mauriello, F.; Russo, M.; Muscolo, A.; Ciriminna, R.; Avellone, G. Amino acids in new organic fertilizer AnchoisFert. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202203665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Scurria, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Avellone, G.; Chemat, F.; Pagliaro, M. Omega-3 extraction from anchovy fillet leftovers with limonene: Chemical, economic, and technical aspects. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 15359–15363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Oviedo, J.; Yara-Varón, E.; Torres, M.; Canela-Garayoa, R.; Balcells, M. Sustainable synthesis of omega-3 fatty acid ethyl esters from monkfish liver oil. Catalysts 2021, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angellotti, G.; Pizzone, D.M.; Pagliaro, M.; Avellone, G.; Lino, C.; Mauriello, F.; Ciriminna, R. High stability of AnchoisOil extracted with limonene from anchovy fillet leftovers. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrukan, M.; Raharjo, S.; Yanti, R.; Setyaningsih, W. Dual response optimization of ultrasound-assisted oil extraction from milkfish by-products using d-limonene as a bio-based solvent. Trends Sci. 2024, 21, 8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutrasource. Omega-3s; Nutrasource: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2025; Available online: https://www.nutrasource.ca/markets/omega-3s/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Arfelli, F.; Pizzone, D.M.; Cespi, D.; Ciacci, L.; Ciriminna, R.; Calabrò, P.S.; Pagliaro, M.; Mauriello, F.; Passarini, F. Prospective life cycle assessment for the full valorization of anchovy fillet leftovers: The LimoFish process. Waste Manag. 2023, 168, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliment Limited. Omega Plus Finest Fish Oil Capsules 120 Capsules, Cwmafan (Great Britain). 2025. Available online: https://alimentnutrition.co.uk/products/omega3-fish-oil-capsules-epa-dha (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Erol, H.S.; Metin, H.; Kaynar, Ö.; Acar, Ü.; Kesbiç, O.S. Sustainable use of orange peel essential oil: A natural antioxidant to combat fish oil oxidation. Memba Kastamonu Üniv. Ürünleri Fak. Derg. 2024, 10, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedullà, A.; Carabetta, S.; Ciriminna, R.; Russo, M.; Pagliaro, M.; Calabrò, P.S. TunaOil: Integral fish oil from tuna processing waste via the LimoFish process. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behar-Levy, H.; Avnir, D. Entrapment of organic molecules within metals: dyes in silver. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avnir, D. Recent progress in the study of molecularly doped metals. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinai, O.; Avnir, D. Organics@metals as the basis for a silver/doped-silver electrochemical cell. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 3289–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, S.K. Silver solos in lemon circuit. Chem. Eng. News 2011, 89, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Search carried out at https://scopus.com accessed on 10 November 2025, with the query “molecularly doped metals” extending the search to “All fields”.

- LaCoste, J.D.; Buggy, N.C.; Herring, A.M. Studying molecularly doped metals as catalyst for alkaline fuel cells and electrolysis. Meet. Abstr. 2021, MA2021-02, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy-Leblond, J.-M. Two cultures or none? In Science and Technology Awareness in Europe: New Insights; Vitale, M., Ed.; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1998; pp. 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Formenti, M.; Ciriminna, R.; Lupi, G.; Fanciulli, C.; Della Pina, C.; Casati, R.; Pagliaro, M. CuproGraf: Towards readily accessible copper of enhanced electrical conductivity. SustEnergMat 2026, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Formenti, M.; Ciriminna, R.; Della Pina, C.; Pagliaro, M. Reduced NiGraf: An effective hydrogenation catalyst of large applicative potential. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, A.; Fiano, F.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Paoloni, P.; Briamonte, M.F.; Orlando, B. Unveiling the impact of the adoption of digital technologies on firms’ innovation performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarrà, D.; Piccaluga, A. The impact of technology transfer and knowledge spillover from Big Science: A literature review. Technovation 2022, 116, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.M.; Uskoković, V. Waiting for aπαταω: 250 Years later. Found. Sci. 2019, 24, 617–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uskoković, V. Natural sciences and chess: A romantic relationship missing from higher education curricula. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagliaro, M.; Muscolo, A.; Russo, M.; Mauriello, F.; Avellone, G.; Calabrò, P.S.; Ciriminna, R. How Are Discoveries in Chemistry Made? Insight from Three Discoveries and Their Impact. Chemistry 2025, 7, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060200

Pagliaro M, Muscolo A, Russo M, Mauriello F, Avellone G, Calabrò PS, Ciriminna R. How Are Discoveries in Chemistry Made? Insight from Three Discoveries and Their Impact. Chemistry. 2025; 7(6):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060200

Chicago/Turabian StylePagliaro, Mario, Adele Muscolo, Mariateresa Russo, Francesco Mauriello, Giuseppe Avellone, Paolo Salvatore Calabrò, and Rosaria Ciriminna. 2025. "How Are Discoveries in Chemistry Made? Insight from Three Discoveries and Their Impact" Chemistry 7, no. 6: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060200

APA StylePagliaro, M., Muscolo, A., Russo, M., Mauriello, F., Avellone, G., Calabrò, P. S., & Ciriminna, R. (2025). How Are Discoveries in Chemistry Made? Insight from Three Discoveries and Their Impact. Chemistry, 7(6), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060200