Microwave-Irradiated Eco-Friendly Multicomponent Synthesis of Substituted Pyrazole Derivatives and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Antibacterial Sensitivity Assays

2.2. Ligand Acquisition, Protein Preparation, and Molecular Docking at Active Site of the Essential Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs) of the Investigated Bacteria

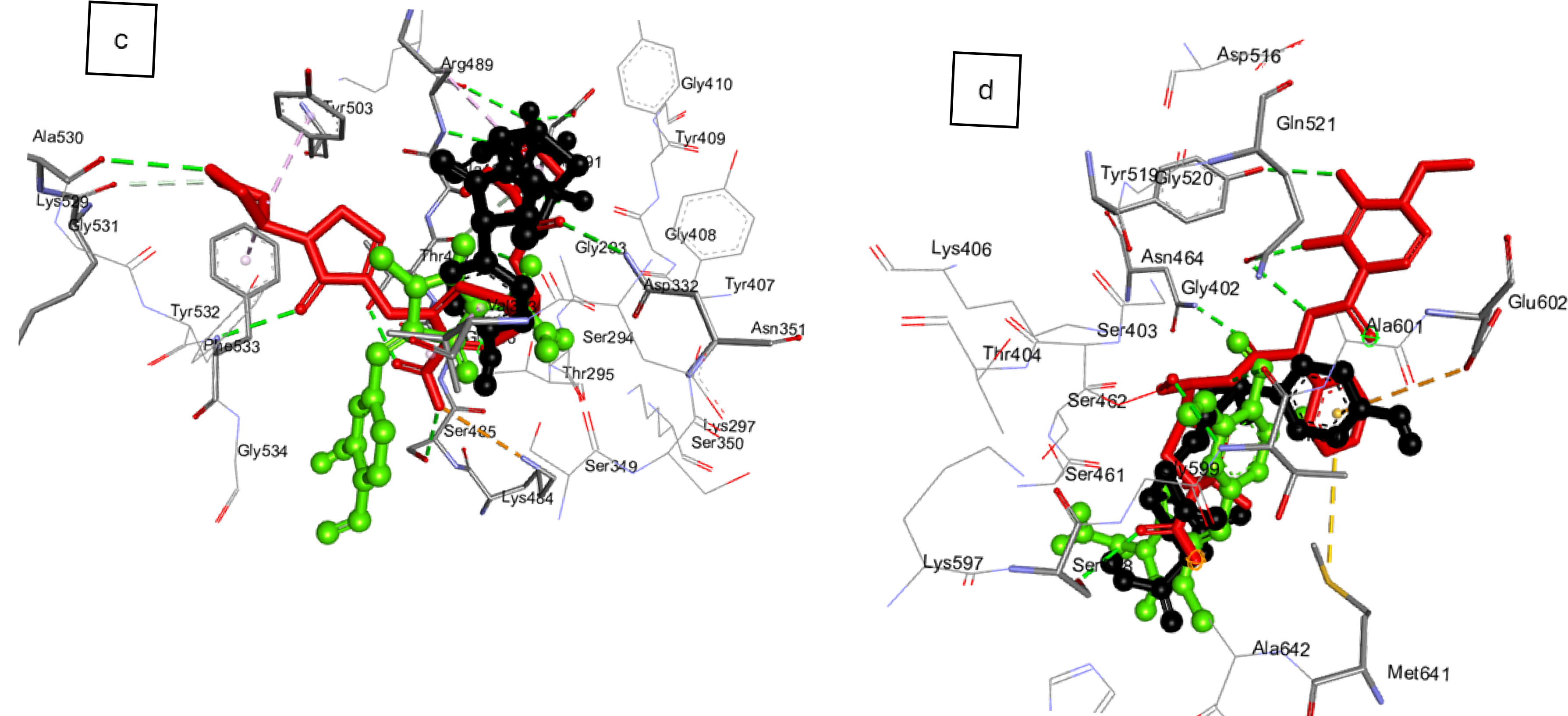

2.3. In Silico Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity Prediction

3. Results and Discussion

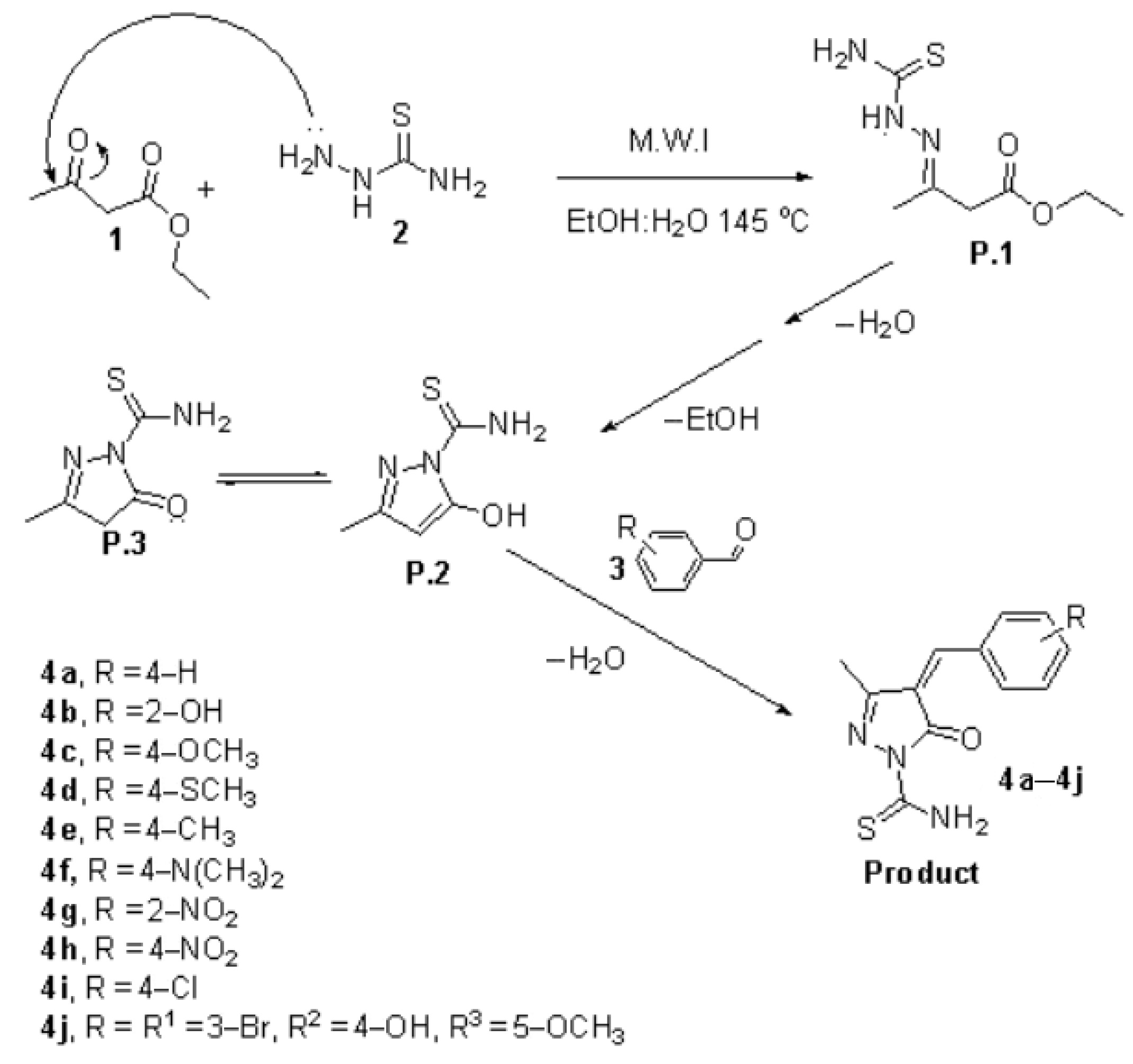

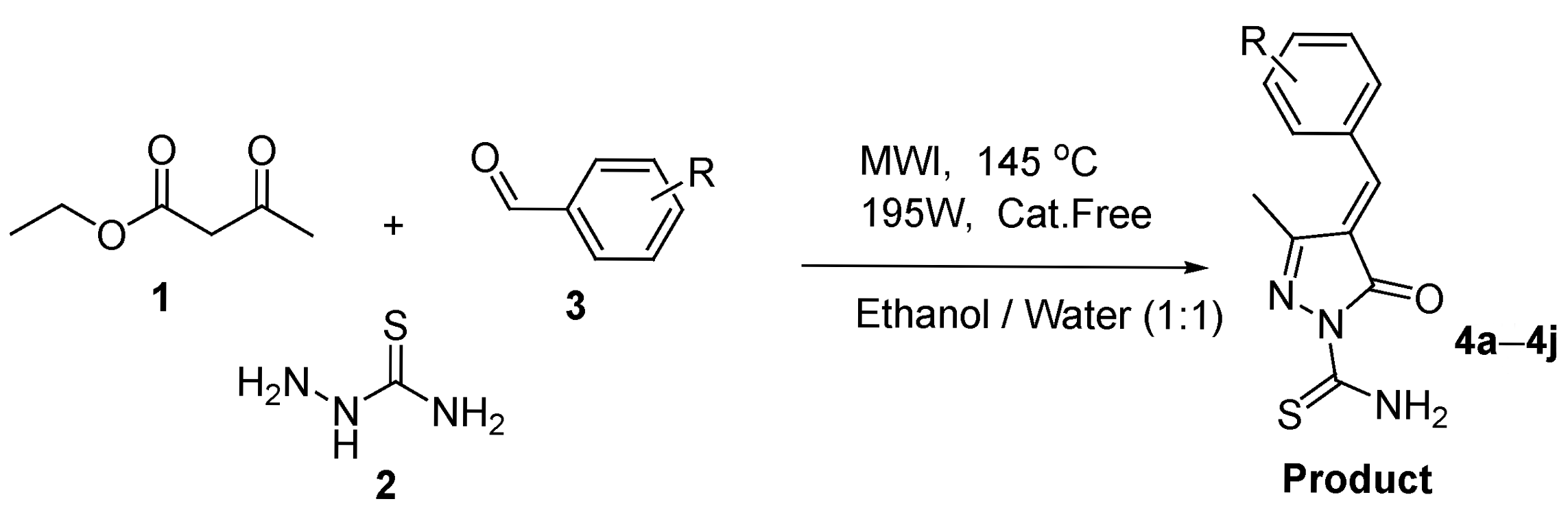

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Synthesis and Characterization of (4E)-4-Arylidene-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide Derivatives

3.3. Sample Structural/Spectral Assignment of 4a

3.4. Spectral Assignment of 4b–4j

- (4E)-4-(2-hydroxybenzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4b

- Yield is 89% pale lemon solids. M.p 198–201 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3302–3333 (NH), 3045 (=C-H), 1593 (C=N), 1003–1083 (C=S), 3423 (C-OH), and 1208 (C-O). The 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); at δ11.34 ppm (2H, s) H2N-C=S; δ8.37 ppm (1H, H4, s) sp2-CH; at δ6.87 ppm (2H, H2′ and H5′, d, J = 8.16); δ7.22 ppm (1H, H3′, t, J = 7.26 Hz); at δ6.81 ppm (1H, H4′, t, J = 7.44 Hz); and -OH δ9.88 ppm (1H, s). 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ131.5 ppm, δ272.2 ppm, δ119.7 ppm, δ116.5 ppm, δ140.2 ppm, δ116.5 ppm and δ178.1 TOF-MS ES found [Na + M+] 287.0031 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated [Na + M+] 283.3 m/z.

- (4E)-4-(4-methoxynzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4c

- Yield is 94% cream white solids. M.p 158–160 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3298–3331 (NH), 3049 (=C-H), 1605 (C=N), 1017–1085 (C=S), and 1150 (C-O-C). The 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); at δ11.32 ppm (1H, s) H2N-C=S; δ7.74 ppm (2H, H2′ and H4′, d, J = 8.70 Hz); δ6.96 ppm (2H, H1′ and H5′, d, J = 8.76 Hz); δ3.85 ppm (3H, methoxy, s) and δ8.11 ppm sp2-CH (1H, H4, s). 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ132.1 ppm, δ129.3 ppm, δ161.2 ppm, δ127.1 ppm, δ115.1 ppm, δ178.1 ppm and δ142.8 ppm. TOF-MS ES found [Na + M+], 297.1531 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated [Na + M+], 298 m/z.

- (4E)-4-(4-(methylthio)benzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4d

- Yield is 90% pale grey solids. M.p 210–216 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3300–3314 (NH), 3057 (=C-H), 1601 (C=N), 1012–1061 (C=S). The 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); at δ11.40 ppm (1H, s) H2N-C=S; δ2.08 ppm (3H, methyl, s); δ7.73 ppm (2H, H2′ and H4′, d, J = 8.40 Hz); δ7.26 ppm (2H, H1′ and H5′, d, J = 8.26 Hz); δ8.00 ppm (1H, H4, s, sp2-CH). 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ178.3 ppm, δ206.9 ppm, δ161.3 ppm, δ191.5 ppm, δ129.1 ppm, δ125.9, δ130.4 ppm and δ142.3 ppm. TOF-MS ES found [M+] 290.0000 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated 291.4 m/z.

- (4E)-4-(4-methylbenzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4e

- Yield is 91% cream-grey solids. M.p 166–170 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3346 (NH), 2916 (-C-H aromatic), 1065–1148 (C=S), 2328–2622 (methyl stretch). The 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); at δ11.37 ppm (1H, s) H2N-C=S; δ2.08 ppm (3H, methyl H5 and H3″, s); δ7.69 ppm (2H, H2′ and H4′, d, J = 8.10 Hz); δ7.22 ppm (2H, H1′ and H5′, d, J = 7.92 Hz); δ8.01 ppm (1H, H4, s, sp2-CH). 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ178.3 ppm, δ206.9 ppm, δ140.1 ppm, δ128.7 ppm, δ142.9 ppm, and δ129.9. TOF-MS ES found [M+] 261.1314 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated 259.3 m/z.

- (4E)-4-(4-(dimethyamino)benzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4f

- Yield is 92% reddish brown solids. M.p 208–210 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3301–3314 (NH), 3046 (=C-H), 1590 (C=N), 995–1079 (C=S), and 1221 (C-O). The 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); δ11.18 ppm (1H, s) H2N-C=S; δ2.96 ppm (3H, H6′, s, N-CH3); δ6.69 ppm (2H, H2′ and H4′, d, J = 8.82 Hz); δ7.59 ppm (2H, H1′ and H5′, d, J = 8.82 Hz) and δ7.92 ppm (1H, H4, s) sp2-CH. 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ177.5 ppm, δ190.3 ppm, δ143.8 ppm, δ129.1 ppm, δ151.9 ppm, and δ45.8 ppm. TOF-MS ES found [Na + M+], 311.1693 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated [Na + M+], 312.39 m/z.

- (4E)-4-(4-nitronzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4g

- Yield is 95% bright yellow solids. M.p 239–241 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3302–3332 (NH), 3046 (=C-H), 1540 (C=N), 1015–1086 (C=S), and 1485 (NO-Stretch). The 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); δ11.72 ppm (1H, s) H2N-C=S; δ8.22 ppm (2H, H2′ and H4′, d, J = 8.76 Hz); δ8.09 ppm (2H, H1′ and H5′, d, J = 8.76 Hz); δ8.12 ppm sp2-CH (1H, H4, s). 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ128.6 ppm, δ124.2 ppm, δ148.5 ppm, δ141.2 ppm, and δ178.9 ppm. TOF-MS ES found [M+] 295.0000 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated 290.3 m/z.

- (4E)-4-(2-nitrobenzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4h

- Yield is 87% bright yellow solids. M.p 239–241 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3314–3341 (NH), 3055 (=C-H), 1630 (C=N), 1013–1086 (C=S), and 1304 and 1485 (C-NO). The 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); at δ11.74 ppm (1H, s) H2N-C=S; δ8.02 ppm (1H, H2′, d, J = 8.16 Hz); δ8.43 ppm (1H, H3′, t, J = 5.28 Hz); and δ7.73 ppm (1H, H5′, d, J = 7.68 Hz). 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ130.7 ppm, δ133.7 ppm, δ128.8 ppm, δ137.7 ppm, δ128.7 ppm and δ124.9 ppm, δ148.7, and δ178.9 ppm TOF-MS ES found [M+] 292.1549 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated 290.3 m/z.

- (4E)-4-(4-chlorobenzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4i

- Yield is 90% pale grey solids. M.p 190–194 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3308–3322 (NH), 3059 (=C-H), 1635 (C=N), 1033–1077 (C=S), and 791 (C-Cl). The 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); at δ11.47 ppm (2H, s) H2N-C=S; δ7.83 ppm (2H, H1′ and H5′, d, J = 8.46 Hz); δ7.44 ppm (2H, H2′ and H4′, d, J = 8.46 Hz). 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ177.5 ppm, δ141.4 ppm, δ129.4 ppm, δ133.6 ppm, TOF-MS ES found [M+] 279.0753 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated 279.0 m/z.

- (4E)-4-(3-bromo-4-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzylidene)-4,5-dihydro-3-methyl-5-oxopyrazole-1-carbothioamide 4j

- Yield is 96% pale brown solids. M.p 209–211 °C. FT-IR (KBr, v, cm−1): 3310–3333 (NH), 3057 (=C-H), 1624 (C=N), 1013–1088 (C=S), and 3413 and 3499 (C-OH). The 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO); at δ11.36 ppm (1H, s) H2N-C=S; δ7.49 ppm (1H, H1′, s); δ7.43 ppm (1H, H5′, s); δ7.91 ppm (1H, H4, s) sp2-CH and -OH δ9.92 ppm (1H, s). 13C NMR (150 MHz, TMS); δ124.8 ppm, δ146 ppm, δ150.3 ppm, δ56.8 ppm, δ110.1 ppm, δ141.8 and δ178.1 ppm, δ148.7, and δ178.9 ppm TOF-MS ES found [M+] 372.0000 m/z; TOF-MS ES calculated 370.2 m/z.

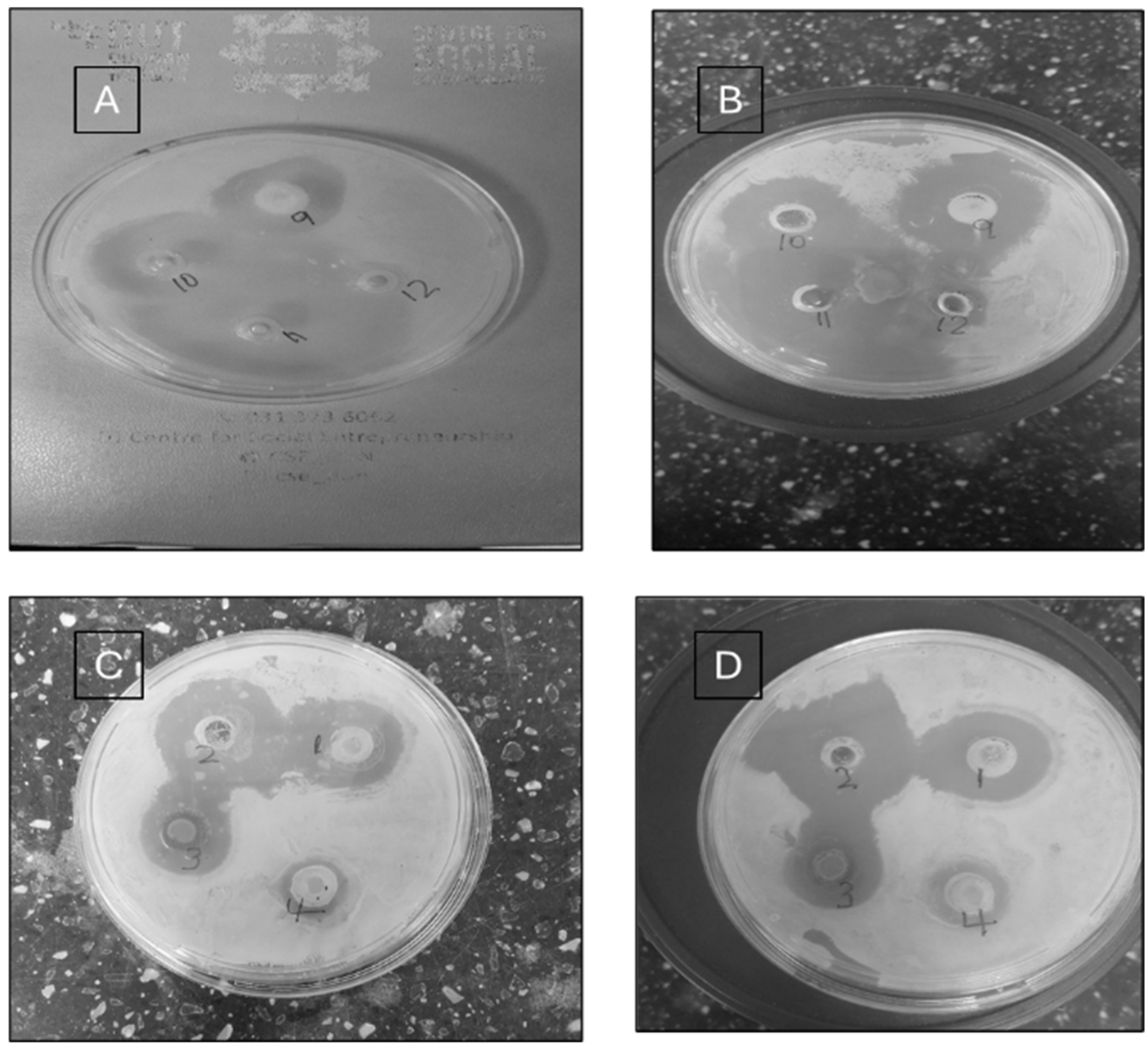

4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Evaluation of Synthesized Pyrazoles

5. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Synthesized Pyrazoles Against Test Organisms

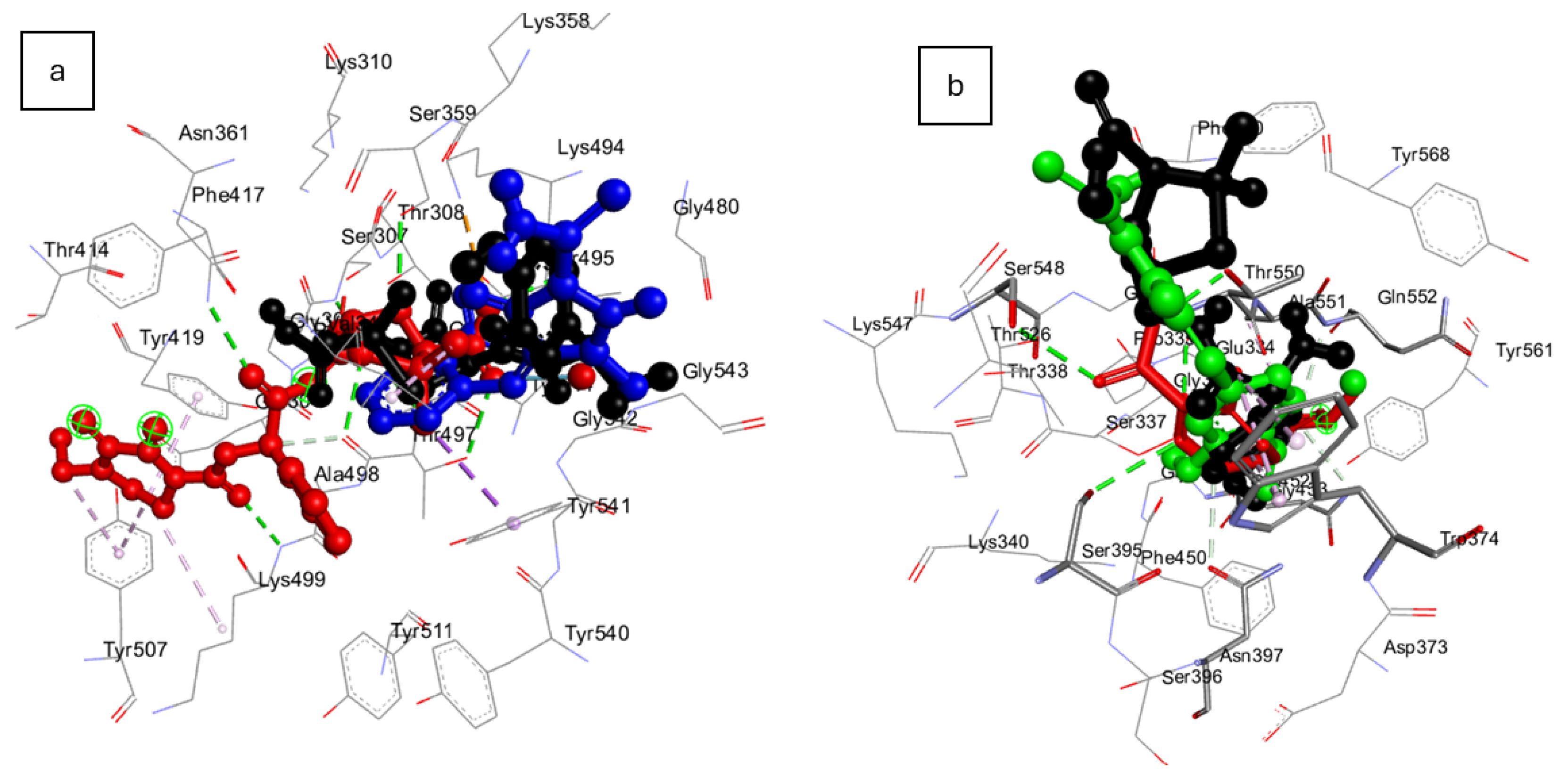

6. Docking Scores of Synthesized Pyrazoles Against Essential Penicillin Binding Proteins (PBPs) of Investigated Bacteria and Their Pharmacokinetic Evaluation

7. Pharmacokinetics and Toxicology Evaluation of Synthesized Pyrazoles

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, N. Benign Approaches for the Microwave-assisted Synthesis of Five-membered 1,2-N,N-heterocycles. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2015, 52, 953–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrouchi, K.; Radi, S.; Ramli, Y.; Taoufik, J.; Mabkhot, Y.N.; Al-Aizari, F.A.; Ansar, M. Synthesis and Pharmacological Activities of Pyrazole Derivatives: A Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkana, F.; Cetin, A.; Taslimic, P.; Karamand, M.; Gulçinc, I. Synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking of novel pyrazole derivatives as potent carbonic anhydrase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 86, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Hoz, A.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J. The mechanism of the reaction of hydrazines with α, β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds to afford hydrazones and 2-pyrazolines (4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazoles): Experimental and theoretical results. Tetrahedron 2021, 97, 132413. [Google Scholar]

- Fustero, S.; Simón-Fuentes, A.; Sanz-Cervera, J.F. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Pyrazoles. A Review. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2009, 41, 253–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Saeed, A.; Hussain, S.; Dar, P.; Larik, F.A. Recent developments in synthetic chemistry and biological activities of pyrazole derivatives. J. Chem. Sci. 2019, 131, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.S.S.; Zeni, G. Alkynes and Nitrogen Compounds: Useful Substrates for the Synthesis of Pyrazoles. Chem. A Eur. J. 2020, 26, 8175–8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henary, M.; Kananda, C.; Rotolo, L.; Savino, B.; Owens, E.; Cravotto, G. Benefits and applications of microwave-assisted synthesis of nitrogen containing heterocycles in medicinal chemistry. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 14170–14197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkal, A.; Kamble, S. Greener and Environmentally Benign Methodology for the Synthesis of Pyrazole Derivatives. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12971–13026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, E. One-Pot Reactions of Triethyl Orthoformate with Amines. Reactions 2023, 4, 779–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, T.D.; Antunes, J.C.; Padrão, J.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Zille, A.; Amorim, M.T.P.; Ferreira, F.; Felgueiras, H.P. Activity of Specialized Biomolecules against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoullis, L.; Papachristodoulou, E.; Chra, P.; Panos, G. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Important Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Pathogens and Novel Antibiotic Solutions. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargianou, M.; Stathopoulos, P.; Vrysis, C.; Tzvetanova, I.D.; Falagas, M.E. New β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combination Antibiotics. Pathogens 2025, 14, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Alam, M. Antibacterial pyrazoles: Tackling resistant bacteria. Future Med. Chem. 2022, 14, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, R.J.; Khankhel, Z.S.; De Anda, C.; Bruno, C.; Puzniak, L.A. 1596. Ceftolozane/tazobactam (Zerbaxa) for the Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PSA) Bacteremia: A Systematic Literature Review (SLR). Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, S794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.M.; Garcia, J.R.; Yuvaraja, G.; Venkata Subbaiah, M.; Wen, J.-C. Design, synthesis of tri-substituted pyrazole derivatives as promising antimicrobial agents and investigation of structure activity relationships. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2020, 57, 2288–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, C.; Kar, D.; Dutta, M.; Kumar, A.; Ghosh, A.S. Moderate deacylation efficiency of DacD explains its ability to partially restore beta-lactam resistance in Escherichia coli PBP5 mutant, FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 337, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Janardhanan, J.; Meisel, J.E.; Ding, D.; Schroeder, V.A.; Wolter, W.R.; Mobashery, S.; Chang, M. In Vitro and In Vivo Synergy of the Oxadiazole Class of Antibacterials with β-Lactams. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5581–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Tang, C.; Bethel, C.R.; Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Wyatt, J.; Desarbre, E.; Bonomo, R.A.; van den Akker, F. Structural insights into ceftobiprole inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa penicillin-binding Protein 3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00106-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, D.; Koekemoer, L.; Newman, H.; Dowson, C.G. Novel and Improved Crystal Structures of H. influenzae, E. coli and P. aeruginosa Penicillin-Binding Protein 3 (PBP3) and N. gonorrhoeae PBP2: Toward a Better Understanding of β-Lactam Target-Mediated Resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3501–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E.; Mouz, N.; Duee, E.; Dideberg, O. The crystal structure of the penicillin-binding protein 2x from Streptococcus pneumoniae and its acyl-enzyme form: Implication in drug resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 299, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aribisala, J.O.; Saheed, S. Cheminformatics Identification of Phenolics as Modulators of Penicillin-Binding Protein 2a of Staphylococcus aureus: A Structure–Activity-Relationship-Based Study. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.K.; Ahmed, S.F.; Hossain, M.S.; Bhojiya, A.A.; Mathur, A.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Srivastava, A.K.; Vishvakarma, N.K.; Barik, M.; Rahaman, M.M.; et al. Molecular docking and simulation studies of flavonoid compounds against PBP-2a of methicillin—Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 10561–10577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslow, R. The Principles of and Reasons for Using Water as a Solvent for Green Chemistry. In Handbook of Green Chemistry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 42, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dallinger, D.; Kappe, C.O. Microwave-assisted synthesis in water as solvent. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2563–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R. Fundamentals of Green Chemistry: Efficiency in Reaction Design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1437–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-J.; Trost, B.M. Green chemistry for chemical synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13197–13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, G.; Ramalingam, K.; Jaykar, B.; Rathnakumar, T. In vitro antibacterial activity of different extracts of leaves of Coldenia procumbens. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2011, 3, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.K.; Chandak, N.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, C.; Aneja, K.R. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Some 4-Functionalized-Pyrazoles as Antimicrobial Agents: Short Communication. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury, S.; Bird, L.; Rao, V.; Shepherd, S.M.; Stuart, D.I.; Hunter, W.N.; Owens, R.J.; Ren, J. Crystal structures of penicillin-binding protein 3 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Comparison of native and antibiotic-bound forms. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 405, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MubarakAli, D.; MohamedSaalis, J.; Sathya, R.; Irfan, N.; Kim, J.W. An evidence of microalgal peptides to target spike protein of COVID-19: In silico approach. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 160, 105189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallakyan, S.; Olson, J.A. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1263, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khodairy, F.M.; Khan, M.K.A.; Kunhi, M.; Pulicat, M.S.; Akhtar, S.; Arif, J.M. In Silico prediction of mechanism of erysolin induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cell lines. Am. J. Bioinform. Res. 2013, 3, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bajorath, J. Rational drug discovery revisited: Interfacing experimental programs with bio- and chemo-informatics. Drug Discov. Today 2001, 6, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.K.A.; Elghandour, A.H.H.; Abdel-Sayed, G.S.M.; Abdel Fattah, A.S.M. ChemInform Abstract: Synthesis of Pyrazoles and Fused Pyrazoles. Novel Synthesis of Pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole, Thieno[2,3-c]pyrazole and Pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine Derivatives. ChemInform 2010, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salum, K.A.; Alidmat, M.M.; Khairulddean, M.; Kamal, N.N.S.N.M.; Muhammad, M. Design, Synthesis, Characterization, and Cytotoxicity Activity Evaluation of Mono-Chalcones and New Pyrazolines Derivatives Article Info. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 10, 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Boudjellal, F.; Ouici, H.B.; Guendouzi, A.; Benali, O.; Sehmi, A. Experimental and Theoretical Approach to the Corrosion Inhibition of Mild Steel in Acid Medium by a Newly Synthesized Pyrazole Carbothioamide Heterocycle. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1199, 127051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatab, T.K.; Kandil, E.; Elsefy, D.E.; El-Mekabaty, A. A one-pot multicomponent catalytic synthesis of new 1H-pyrazole-1-carbothioamide derivatives with molecular docking studies as cox-2 inhibitors. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 13779–13789. [Google Scholar]

- Makhanya, T.; Gengan, R.; Kasumbwe, K. Synthesis of Fused Indolo—Pyrazoles and Their Antimicrobial and Insecticidal Activities against Anopheles arabiensis Mosquito. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 2756–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mert, S.; Kasımoğulları, R.; İça, T.; Çolak, F.; Altun, A.; Ok, S. Synthesis, structure–activity relationships, and in vitro antibacterial and antifungal activity evaluations of novel pyrazole carboxylic and dicarboxylic acid derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 78, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón-Carrasco, J.P. When virtual screening yields inactive drugs: Dealing with false theoretical friends. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aribisala, J.O.; Abdulsalam, R.A.; Dweba, Y.; Madonsela, K.; Sabiu, S. Identification of secondary metabolites from Crescentia cujete as promising antibacterial therapeutics targeting type 2A topoisomerases through molecular dynamics simulation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 145, 105432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntie-Kang, F. An in silico evaluation of the ADMET profile of the StreptomeDB database. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segall, M.D.; Barber, C. Addressing toxicity risk when designing and selecting compounds in early drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 23, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stielow, M.; Witczyńska, A.; Kubryń, N.; Fijałkowski, Ł.; Nowaczyk, J.; Nowaczyk, A. The Bioavailability of Drugs—The Current State of Knowledge. Molecules 2023, 28, 8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morak-Młodawska, B.; Jeleń, M.; Martula, E.; Korlacki, R. Study of Lipophilicity and ADME Properties of 1,9-Diazaphenothiazines with Anticancer Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, E.; Sivalingam, K.; Doke, M.; Samikkannu, T. Effects of Drugs of Abuse on the Blood-Brain Barrier: A Brief Overview. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, H.; Handral, H.K.; Cha, S.; Nguyen, D.T.P.; Cai, J.; Cao, T.; Wu, C.; Kang, L. Enhancement of Skin Delivery of Drugs Using Proposome Depends on Drug Lipophilicity. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, E.; Pajak, K.; Jozwiak, K. Lipophilicity—Methods of determination and its role in medicinal chemistry. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2012, 70, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ogu, C.C.; Maxa, J.L. Drug interactions due to cytochrome P450. Proc. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. 2000, 13, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Iturbide, N.A.; Díaz-Eufracio, B.I.; Medina-Franco, J.L. In Silico ADME/Tox Profiling of Natural Products: A Focus on BIOFACQUIM. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16076–16084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, T.N.; Wathieu, H.; Ojo, A.; Byers, W.S.; Dakshanamurthy, S. Drug Metabolism in Preclinical Drug Development: A Survey of the Discovery Process, Toxicology, and Computational Tools. Curr. Drug Metab. 2017, 18, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, K.H.; Su, B.H.; Tu, Y.S.; Lin, O.A.; Tseng, Y.J. Mutagenicity in a Molecule: Identification of Core Structural Features of Mutagenicity Using a Scaffold Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waechter, F.; Falcao Oliveira, A.A.; Borges Shimada, A.L.; Bernes Junior, E.; de Souza Nascimento, E. Retrospective application of ICH M7 to anti-hypertensive drugs in Brazil: Risk assessment of potentially mutagenic impurities. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 151, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basak, R.; Nair, N.K.; Mittra, I. Evidence for cell-free nucleic acids as continuously arising endogenous DNA mutagens. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2016, 793–794, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, P.; Somanathan, R. Nitroaromatic compounds: Environmental toxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, therapy and mechanism. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014, 34, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semwal, R.; Semwal, R.B.; Lehmann, J.; Semwal, D.K. Recent advances in immunotoxicity and its impact on human health: Causative agents, effects and existing treatments. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 108, 108859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Solvent | Temperature | Catalyst | Time | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DMF | 120 | Piperidine | 180 min | 32 |

| 2 | DMSO | 120 | TEA | >180 min | 22 |

| 3 | DMSO | 125 | NaOH | >180 min | - |

| 4 | Water | 130 | Glycine | 26 min | 63 |

| 5 | Ethanol | 135 | L-Proline | 40 min | 59 |

| 6 | Ethanol/Water (3:1) | 140 | L-Proline | 33 min | 66 |

| 7 | Ethanol | 145 | - | 17 min | 79 |

| 8 | Ethanol/Water (2:1) | 145 | - | 10 min | 83 |

| 9 | Ethanol/Water (1:1) | 145 | - | 10 min | 91 |

| Entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | Time (min) | Synthesized Pyrazoles | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4-H | - | - | 10 | 4a | 91 |

| 2 | 2-OH | - | - | 10 | 4b | 89 |

| 3 | 4-OCH3 | - | - | 10 | 4c | 94 |

| 4 | 4-SCH3 | - | - | 10 | 4d | 90 |

| 5 | 4-CH3 | - | - | 10 | 4e | 91 |

| 6 | 4-N(CH3)2 | - | - | 10 | 4f | 92 |

| 7 | 4-NO2 | - | - | 10 | 4g | 95 |

| 8 | 2-NO2 | - | - | 10 | 4h | 87 |

| 9 | 4-Cl | - | - | 10 | 4i | 90 |

| 10 | 3-Br | 4-OH | 5-OCH3 | 10 | 4j | 96 |

| Synthesized Pyrazoles | S. aureus | S. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | 20 ± 1.0 | 30 ± 0.0 | 25 ± 1.2 | - |

| 4b | 30 ± 1.0 | 28 ± 0.58 | 15 ± 0.58 | - |

| 4c | 20 ± 1.2 | - | 10 ± 1.7 | - |

| 4d | 20 ± 1.7 | 20 ± 1.2 | - | - |

| 4e | 25 ± 1.5 | 25 ± 1.1 | 14 ± 1.2 | 8 ± 0.0 |

| 4f | 20 ± 1.0 | 20 ± 0.0 | 10 ± 0.58 | 8 ± 1.0 |

| 4g | - | - | - | - |

| 4h | 14 ± 0.58 | 14 ± 1.0 | - | - |

| 4i | 22 ± 0.58 | 22 ± 0.58 | 10 ± 1.2 | - |

| 4j | 23 ± 1.5 | 22 ± 1.0 | 20 ± 1.5 | - |

| Amoxicillin | 50 ± 0.0 | 51 ± 0.58 | 10 ± 0.58 | 32 ± 1.0 |

| 2% DMSO | - | - | - | - |

| Synthesized Pyrazoles | R | S. aureus | S. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | 4-H | 0.212 | 0.149 | 0.170 | - |

| 4b | 2-OH | 0.280 | 0.196 | 0.224 | - |

| 4c | 4-OCH3 | 0.438 | - | 0.438 | - |

| 4d | 4-SCH3 | 0.312 | 0.625 | - | - |

| 4e | 4-CH3 | 0.625 | 0.0156 | 1.25 | 2.50 |

| 4f | 4-N(CH3)2 | 0.344 | 1.38 | 1.38 | 1.38 |

| 4g | 4-NO2 | - | - | - | - |

| 4h | 2-NO2 | 0.438 | 0.438 | - | - |

| 4i | 4-Cl | 0.453 | 0.460 | 0.223 | - |

| 4j | 3-Br, 4-OH, 5-OCH3 | 0.236 | 0.165 | 0.189 | - |

| Amoxicillin | 0.0153 | 0.0306 | 0.0765 | 0.0306 | |

| 2% DMSO | - | - | - | - |

| Synthesized Pyrazoles | PBP3 of E. coli | PBP3 of P. aeruginosa | PBP2x of S. pneumoniae | PBP2a of S. aureus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | - | −7.1 | −7.5 | −5.7 |

| 4b | - | −7.4 | −7.6 | −5.5 |

| 4c | - | −7.5 | −7.6 | −6.0 |

| 4d | - | −7.7 | −7.2 | −5.5 |

| 4e | −7.9 | −7.7 | −8.1 | −6.6 |

| 4f | −7.2 | −7.1 | −7.5 | −5.6 |

| 4g | - | −7.0 | −7.6 | −5.5 |

| 4h | - | −7.3 | −7.9 | −6.0 |

| 4i | - | −7.3 | −7.6 | −5.5 |

| 4j | - | −6.8 | −7.3 | −5.5 |

| Amoxicillin | −7.0 | −7.5 | −7.5 | −5.5 |

| Synthesized Pyrazoles | MolWt < 500 (g/mol) | HB-A ≤ 10 | HB-D ≤ 5 | Log P o/w ≤ 5 | WS | LV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | 245.3 | 2 | 1 | 1.73 | S | No |

| 4b | 261.3 | 3 | 2 | 1.34 | S | No |

| 4c | 275.3 | 3 | 1 | 1.70 | S | No |

| 4d | 291.4 | 2 | 1 | 2.26 | MS | No |

| 4e | 259.3 | 2 | 1 | 2.05 | MS | No |

| 4f | 288.4 | 2 | 3 | 1.73 | S | No |

| 4g | 290.3 | 1 | 4 | 1.17 | MS | No |

| 4h | 288.3 | 3 | 1 | 1.59 | MS | No |

| 4i | 279.7 | 2 | 1 | 2.25 | S | No |

| 4j | 368.2 | 3 | 2 | 2.39 | MS | No |

| Amoxicillin | 365.4 | 6 | 4 | −0.29 | VS | No |

| Synthesized Pyrazoles | GI Absorption | BS | LD50 (mg/kg) | TC | BBB Permeability | Pgp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | High | 0.55 | 960 | 4 | No | No |

| 4b | High | 0.55 | 960 | 4 | No | No |

| 4c | High | 0.55 | 450 | 4 | No | No |

| 4d | High | 0.55 | 1000 | 4 | No | No |

| 4e | High | 0.55 | 960 | 4 | No | No |

| 4f | High | 0.55 | 5400 | 6 | No | No |

| 4g | High | 0.55 | 711 | 4 | No | No |

| 4h | High | 0.55 | 1040 | 4 | No | No |

| 4i | High | 0.55 | 1012 | 4 | No | No |

| 4j | High | 0.55 | 1000 | 4 | No | No |

| Amoxicillin | High | 0.55 | 15,000 | 6 | No | No |

| Synthesized Pyrazoles | CYP-1A2 | CYP-2C19 | CYP-2C9 | CYP-2D6 | CYP-3A4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 4b | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 4c | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 4d | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 4e | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 4f | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 4g | No | No | No | No | No |

| 4h | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 4i | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 4j | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Amoxicillin | No | No | No | No | No |

| Synthesized Pyrazoles | Hepatotoxicity | Carcinogenicity | Mutagenicity | Immunotoxicity | Cytotoxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | - | - | - | I | I |

| 4b | - | - | - | I | I |

| 4c | - | - | - | I | I |

| 4d | - | - | - | I | I |

| 4e | - | - | - | I | I |

| 4f | - | - | - | I | I |

| 4g | - | A | A | I | I |

| 4h | - | A | - | I | I |

| 4i | - | - | - | I | I |

| 4j | - | - | - | A | - |

| Amoxicillin | I | I | I | I | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mntambo, B.L.; Aribisala, J.O.; Sabiu, S.; Majola, S.; Gengan, R.M.; Makhanya, T.R. Microwave-Irradiated Eco-Friendly Multicomponent Synthesis of Substituted Pyrazole Derivatives and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial Potential. Chemistry 2025, 7, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060191

Mntambo BL, Aribisala JO, Sabiu S, Majola S, Gengan RM, Makhanya TR. Microwave-Irradiated Eco-Friendly Multicomponent Synthesis of Substituted Pyrazole Derivatives and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial Potential. Chemistry. 2025; 7(6):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060191

Chicago/Turabian StyleMntambo, Bahle L., Jamiu O. Aribisala, Saheed Sabiu, Senzekile Majola, Robert M. Gengan, and Talent R. Makhanya. 2025. "Microwave-Irradiated Eco-Friendly Multicomponent Synthesis of Substituted Pyrazole Derivatives and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial Potential" Chemistry 7, no. 6: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060191

APA StyleMntambo, B. L., Aribisala, J. O., Sabiu, S., Majola, S., Gengan, R. M., & Makhanya, T. R. (2025). Microwave-Irradiated Eco-Friendly Multicomponent Synthesis of Substituted Pyrazole Derivatives and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial Potential. Chemistry, 7(6), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060191