High-Entropy Alloys for Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation: Recent Advances on Mechanism and Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Dual Mechanisms of the OER

2.1. Adsorbate Evolution Mechanism (AEM)

2.2. Lattice Oxygen-Mediated Mechanism (LOM)

3. Fundamental Effects of HEAs on OER Progress

3.1. High-Entropy Effect

3.2. Lattice Distortion Effect

3.3. Diffusion Effect

3.4. Cocktail Synergy Effect

4. Synthetic Control of Lattice Oxygen Activity

4.1. Stabilizing the AEM

4.2. Bifunctional LOM/AEM Switching

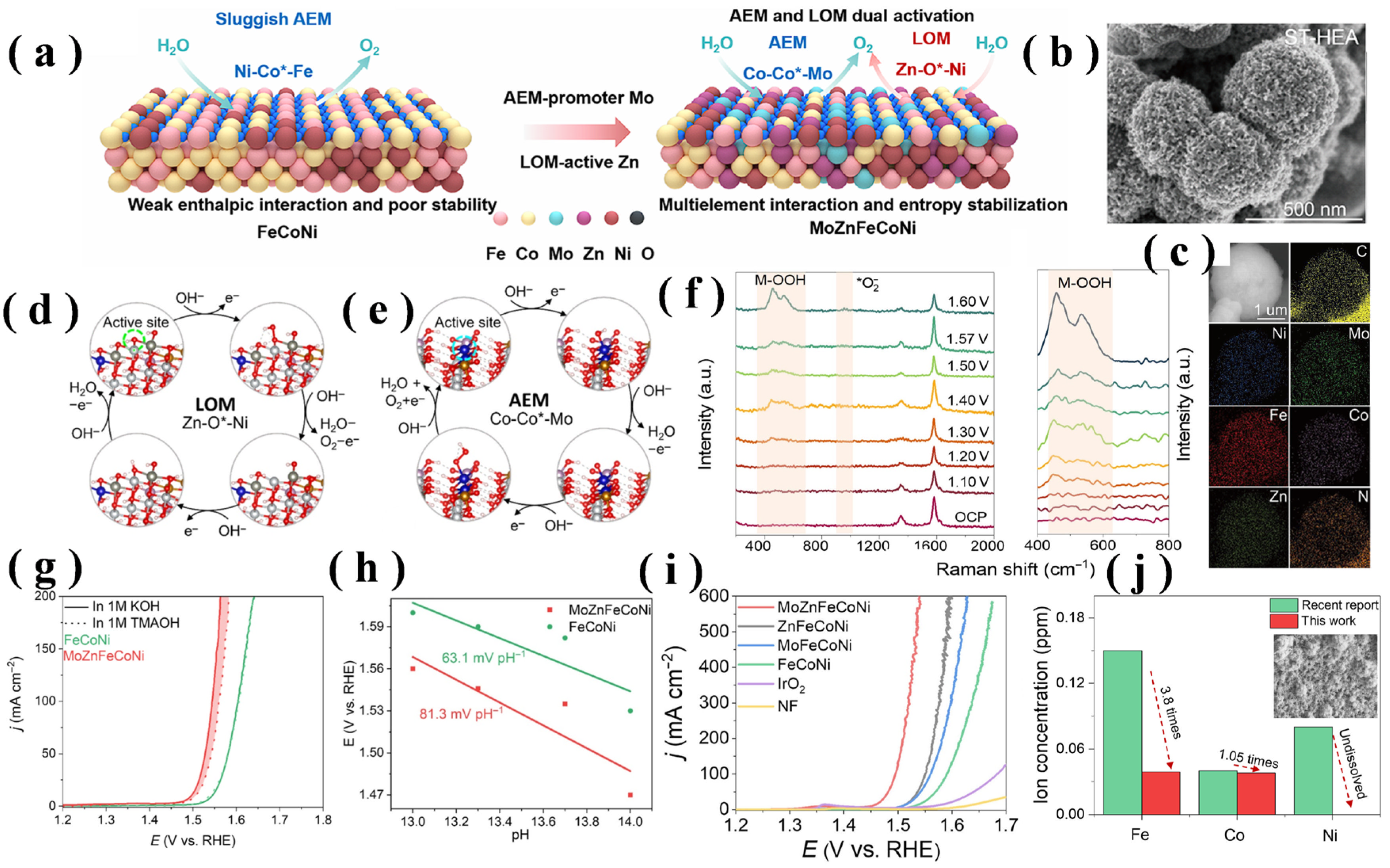

4.3. Coupled AEM-LOM Activation

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Challenge and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, H.C.; Li, W.; Lee, Y.L.; Zheng, H.K.; Li, Q.Y.; Ma, L.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Chen, X.J.; Zhang, D.W.; Li, G.S.; et al. Conformally coated scaffold design using water-tolerant PrBaNiO for protonic ceramic electrochemical cells with 5,000-h electrolysis stability. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.K.; AlGarni, T.S.; Javed, M.S.; Shah, S.S.A.; Hussain, S.; Xu, M.W. 2D MXene Materials for Sodium Ion Batteries: A review on Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2021, 37, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Ding, X.; Lv, Q.J.; Qin, H.T.; Li, A.S.; Yang, X.; Han, J.; Song, F. Electronic engineering induced ultrafine non-noble nanoparticles for high-performance hydrogen evolution from ammonia borane hydrolysis. Fuel 2025, 381, 133424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.Y.; Zabed, H.M.; Wei, Y.T.; Qi, X.H. Technoeconomic and environmental perspectives of biofuel production from sugarcane bagasse: Current status, challenges and future outlook. Ind. Crop Prod. 2022, 188, 115684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, B.; Jing, M.X.; Shen, X.Q.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Yan, X.H.; He, X.M. In Situ Catalytic Polymerization of a Highly Homogeneous PDOL Composite Electrolyte for Long-Cycle High-Voltage Solid-State Lithium Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2201762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, C.; Tang, H.; Liu, Q.Q.; Bahadur, I.; Karlapudi, S.; Jiang, Y.J. A latest overview on photocatalytic application of g-CN based nanostructured materials for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 337–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.K.; Pan, Y.; Wang, X.H.; Guo, Y.N.; Ni, C.H.; Wu, J.B.; Hao, C. High performance hybrid supercapacitors assembled with multi-cavity nickel cobalt sulfide hollow microspheres as cathode and porous typha-derived carbon as anode. Ind. Crop Prod. 2022, 189, 115863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, R.; Ling, G.; Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Hao, C. Cu-Ag-C@Ni3S4 with core shell structure and rose derived carbon electrode materials: An environmentally friendly supercapacitor with high energy and power density. Ind. Crop Prod. 2024, 222, 119676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.Z.; Colella, W.G.; Golden, D.M. Cleaning the air and improving health with hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles. Science 2005, 308, 1901–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Y.; Ding, X.; Xiang, J.; Qin, H.T.; Tang, S.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Dong, J.; Yin, Y.; Jiang, N.; Yang, X.; et al. Iron-induced charge density redistribution of medium entropy alloys for ampere-level seawater electrolysis. Fuel 2026, 406, 137084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Li, G.; Wang, J.P.; Xu, L.X.; Cheng, D.G.; Chen, F.Q.; Asakura, Y.; Kang, Y.Q.; Yamauchi, Y. Modulating Electronic Metal-Support Interactions to Boost Visible-Light-Driven Hydrolysis of Ammonia Borane: Nickel-Platinum Nanoparticles Supported on Phosphorus-Doped Titania. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202305371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.L.; Sun, Q.H.; Zhang, T.J.; Zhang, J.C.; Dong, Z.Y.; Ma, Y.H.; Wu, Z.X.; Wang, H.F.; Bao, X.G.; Sun, Q.M.; et al. Cobalt-Promoted Noble-Metal Catalysts for Efficient Hydrogen Generation from Ammonia Borane Hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 5486–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.T.; Tang, S.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Li, A.S.; Lv, Q.J.; Dong, J.L.; Liu, L.Y.; Ding, X.; Jiang, N.; Luo, R.; et al. Alkaline functional chromium carbide: Immobilization of ultrafine ruthenium copper nanoparticles for efficient hydrogen evolution from ammonia borane hydrolysis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 697, 137897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, H.T.; Liu, M.Q.; Tang, S.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Ding, X.; Song, F. Pd Nanoparticles Confined by Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Architecture Derived from Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks for Remarkable Hydrogen Evolution from Formic Acid Dehydrogenation. Catalysts 2025, 15, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, P.; Zhang, S.L.; Yang, J.; Guan, C.; Li, J.P.; Liu, M.J.; Pan, W.W.; Wang, Y.Q. Investigation on the Al/low-melting-point metals/salt composites for hydrogen generation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 9627–9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.C.; Xu, Q. Ru Nanoparticles Confined within a Coordination Cage. Chem 2018, 4, 403–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, E.H.; Song, N.; Hong, S.H.; She, C.; Li, C.M.; Fang, L.Y.; Dong, H.J. Zn, S, N self-doped carbon material derived from waste tires for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 16544–16551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.T.; Tang, S.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Li, A.S.; Lv, Q.J.; Dong, J.L.; Liu, L.; Ding, X.; Pan, X.; Yang, X.; et al. Alkaline titanium carbide (MXene) engineering ultrafine non-noble nanocatalysts toward remarkably boosting hydrogen evolution from ammonia borane hydrolysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.Q.; Qiu, J.X.; Tang, S.Y.; Lv, Q.J.; Dong, J.L.; Jiang, N.; Liu, L.Y.; Wan, Y.Y.; Yang, X.C.; Han, J.; et al. Engineering cobalt coordination environment with dual heteroatom doping for boosting urea-assisted hydrogen evolution. Fuel 2025, 395, 135161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.C.; Yang, S.S.; Yang, H.; Gao, S.; Yan, X.H. Mechanism of heteroatom-doped Cu catalysis for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 7802–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debe, M.K. Electrocatalyst approaches and challenges for automotive fuel cells. Nature 2012, 486, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamenkovic, V.R.; Strmcnik, D.; Lopes, P.P.; Markovic, N.M. Energy and fuels from electrochemical interfaces. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, M.L.; Mahato, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Visible-light-switchable Chalcone-Flavylium Photochromic Systems in Aqueous Media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202311551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Rao, D.W.; Ye, J.J.; Yang, S.K.; Zhang, C.N.; Gao, C.; Zhou, X.C.; Yang, H.; Yan, X.H. Mechanism of transition metal cluster catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 3484–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.A.; El Jery, A.; Najam, T.; Nazir, M.A.; Wei, L.; Hussain, E.; Hussain, S.; Ben Rebah, F.; Javed, M.S. Surface engineering of MOF-derived FeCo/NC core-shell nanostructures to enhance alkaline water-splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 5036–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Li, X.F.; Wei, Y.S.; Fu, Z.M.; Wei, W.B.; Wu, X.T.; Zhu, Q.L.; Xu, Q. Ordered Macroporous Superstructure of Nitrogen-Doped Nanoporous Carbon Implanted with Ultrafine Ru Nanoclusters for Efficient pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2006965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.P.; Tang, S.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Wang, J.; Li, A.S.; Jing, M.X.; Yang, X.C.; Song, F.Z. Encapsulation of ruthenium oxide nanoparticles in nitrogen-doped porous carbon polyhedral for pH-universal hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 74, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.K.; Li, H.X.; Chen, L.; Ren, M.N.; Fakayode, O.A.; Han, J.Y.; Zhou, C.S. Efficient hydrogen evolution reaction performance using lignin-assisted chestnut shell carbon-loaded molybdenum disulfide. Ind. Crop Prod. 2023, 193, 116214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Zhou, W.D.; Yan, X.H.; Huang, X.P.; Wu, S.T.; Pan, J.M.; Shahnavaz, Z.; Li, T.; Yu, X.Y. Sodium dodecyl sulfate intercalated two-dimensional nickel-cobalt layered double hydroxides to synthesize multifunctional nanomaterials for supercapacitors and electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Fuel 2023, 333, 126323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Jiang, H.; Mei, G.L.; Sun, Y.J.; You, B. Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Overall and Hybrid Water Splitting. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 3694–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.P.; Lv, Q.J.; Pan, X.Q.; Dong, J.L.; Liu, L.Y.; Wan, Y.; Han, J.; Song, F. Heteroatom Engineering in Earth-Abundant Cobalt Electrocatalyst for Energy-Saving Hydrogen Evolution Coupling with Urea Oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 66008–660017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotochaud, L.; Ranney, J.K.; Williams, K.N.; Boettcher, S.W. Solution-Cast Metal Oxide Thin Film Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 17253–17261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Q.H.; Yu, X.J.; Chen, L.; Yarley, O.P.N.; Zhou, C.S. Facile preparation of sugarcane bagasse-derived carbon supported MoS2 nanosheets for hydrogen evolution reaction. Ind. Crop Prod. 2021, 172, 114064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.F.; Tang, S.Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Xie, Y.F.; Yin, Y.; Song, F.Z. Unraveling the mechanism of hydrogen evolution reactions in alkaline media: Recent advances in Raman spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 8778–8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.N.; Wang, M.Y.; Zhang, X.Z.; Lu, L.; Tang, H.; Liu, Q.Q.; Lei, S.Y.; Qiao, G.J.; Liu, G.W. Construction of 0D/3D CdS/CoAl-LDH S-scheme heterojunction with boosted charge transfer and highly hydrophilic surface for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and antibiotic degradation. Fuel 2023, 338, 127259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.F.; Pang, S.L.; Long, C.; Fang, T.; Yang, G.M.; Song, Y.F.; He, X.D.; Ma, S.; Qian, Y.Z.; Shen, X.Q.; et al. Quenching-induced surface reconstruction of perovskite oxide for rapid and durable oxygen catalysise. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 463, 142509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.Z.; Zhao, H.R.; Huang, S.Y.; Zhang, L.L.; Li, J.; Weng, Y.; Sun, Z.T.; Zhang, X.M.; Ye, S.F.; Chen, Y.F. Promoting the activation of HO via vacancy defects over metal-organic framework-derived cobalt oxide for enhanced oxygen evolution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 32598–32606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.Z.; Ding, X.; Wan, Y.Y.; Zhang, T.; Yin, G.G.; Brown, J.B.; Rao, Y. Interface Charge Transfer of Heteroatom Boron Doping Cobalt and Cobalt Nitride for Boosting Water Oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 3535–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.H.; Qiu, F.; Yuan, W.B.; Guo, M.M.; Lu, Z.H. Nitrogen-doped carbon-decorated yolk-shell CoP@FeCoP micro-polyhedra derived from MOF for efficient overall water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 403, 126312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Liu, P.Y.; Li, W.B.; Xu, W.W.; Wen, Y.J.; Zhang, S.X.; Yi, L.; Dai, Y.Q.; Chen, X.; Dai, S.; et al. Stable Seawater Electrolysis Over 10 000 H via Chemical Fixation of Sulfate on NiFeBa-LDH. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2411302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Zhang, F.; Ping, H.; Li, N.; Zhou, J.Y.; Lei, L.W.; Xie, J.J.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wang, W.M.; Fu, Z.Y. Sol-gel Autocombustion Synthesis of Nanocrystalline High-entropy Alloys. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.F.; Wu, P.W.; Lin, P.; Chao, C.G.; Yeh, K.Y. Sputter deposition of multi-element nanoparticles as electrocatalysts for methanol oxidation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 47, 5755–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.C.; Miracle, D.B.; Maurice, D.; Yan, X.H.; Zhang, Y.; Hawk, J.A. High-entropy functional materials. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 3138–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, F.; Yang, Y.; Bei, H.; George, E.P. Relative effects of enthalpy and entropy on the phase stability of equiatomic high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 2628–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.H.; Yeh, J.W. High-Entropy Alloys: A Critical Review. Mater. Res. Lett. 2014, 2, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.J.; Fang, G.; Wen, Y.R.; Liu, P.; Xie, G.Q.; Liu, X.J.; Sun, S.H. Nanoporous high-entropy alloys for highly stable and efficient catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 6499–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.G.; Dong, Q.; Brozena, A.; Luo, J.; Miao, J.W.; Chi, M.F.; Wang, C.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Ren, Z.J.; Greeley, J.; et al. High-entropy nanoparticles: Synthesis-structure-property relationships and data-driven discovery. Science 2022, 376, eabn3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, T.A.A.; Pedersen, J.K.; Winther, S.H.; Castelli, I.E.; Jacobsen, K.W.; Rossmeisl, J. High-Entropy Alloys as a Discovery Platform for Electrocatalysis. Joule 2019, 3, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, B.M.; Gray, H.B.; Muller, A.M. Earth-Abundant Heterogeneous Water Oxidation Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14120–14136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.F.; Tang, S.Y.; Ding, X.; Yin, Y.; Song, F.Z.; Yang, X.C. In Situ Raman Study of Layered Double Hydroxide Catalysts for Water Oxidation to Hydrogen Evolution: Recent Progress and Future Perspectives. Energies 2024, 17, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mefford, J.T.; Rong, X.; Abakumov, A.M.; Hardin, W.G.; Dai, S.; Kolpak, A.M.; Johnston, K.P.; Stevenson, K.J. Water electrolysis on LaSrCoO perovskite electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaud, A.; Hong, W.T.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Tarascon, J.M. Anionic redox processes for electrochemical devices. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.L.; He, Q.; Zhang, Y.K.; Song, L. Structural Self-Reconstruction of Catalysts in Electrocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2968–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, N.C.S.; Du, L.J.; Xia, B.Y.; Yoo, P.J.; You, B. Reconstructed Water Oxidation Electrocatalysts: The Impact of Surface Dynamics on Intrinsic Activities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2008190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.J.; Wei, C.; Huang, Z.F.; Liu, C.T.; Zeng, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.C.J. A review on fundamentals for designing oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2196–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, J.H.; Seitz, L.C.; Chakthranont, P.; Vojvodic, A.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Norskov, J.K. Materials for solar fuels and chemicals. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chai, Y. Lattice oxygen redox chemistry in solid-state electrocatalysts for water oxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 4647–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norskov, J.K.; Rossmeisl, J.; Logadottir, A.; Lindqvist, L.; Kitchin, J.R.; Bligaard, T.; Jónsson, H. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 17886–17892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.G.; Hwang, J.; Hwang, H.J.; Jeon, O.S.; Jang, J.; Kwon, O.; Lee, Y.; Han, B.; Shul, Y.G. A New Family of Perovskite Catalysts for Oxygen-Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Media: BaNiO and BaNiO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 3541–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaud, A.; Diaz-Morales, O.; Han, B.H.; Hong, W.T.; Lee, Y.L.; Giordano, L.; Stoerzinger, K.A.; Koper, M.T.M.; Shao-Horn, Y. Activating lattice oxygen redox reactions in metal oxides to catalyse oxygen evolution. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Feng, X.B.; Rao, D.W.; Deng, X.; Cai, L.J.; Qiu, B.C.; Long, R.; Xiong, Y.J.; Lu, Y.; Chai, Y. Lattice oxygen activation enabled by high-valence metal sites for enhanced water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Q.; Feng, L.; Zhang, M.W.; Cong, H.L. Engineering oxygen nonbonding states in high entropy hydroxides for scalable water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, G.W.; Zhou, C.H.; Lv, F.; Tan, Y.J.; Han, Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, D.W.; Liu, Y.X.; Shang, C.S.; et al. Lanthanide-regulating Ru-O covalency optimizes acidic oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L.C.; Dickens, C.F.; Nishio, K.; Hikita, Y.; Montoya, J.; Doyle, A.; Kirk, C.; Vojvodic, A.; Hwang, H.Y.; Norskov, J.K.; et al. A highly active and stable IrO/SrIrO catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Science 2016, 353, 1011–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, I.C.; Su, H.Y.; Calle-Vallejo, F.; Hansen, H.A.; Martínez, J.I.; Inoglu, N.G.; Kitchin, J.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Norskov, J.K.; Rossmeisl, J. Universality in Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysis on Oxide Surfaces. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.F.; Song, J.J.; Du, Y.H.; Xi, S.B.; Dou, S.; Nsanzimana, J.M.V.; Wang, C.; Xu, Z.C.J.; Wang, X. Chemical and structural origin of lattice oxygen oxidation in Co-Zn oxyhydroxide oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, E.; Schmidt, T.J. Oxygen Evolution Reaction-The Enigma in Water Electrolysis. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9765–9774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.J.; Zeng, M.Q.; Liu, K.L.; Fu, L. Phase Engineering of High-Entropy Alloys. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1907226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.J.; Yang, C.P.; Li, B.Y.; Dong, Q.; Wu, M.L.; Hwang, S.; Xie, H.; Wang, X.Z.; Wang, G.F.; Hu, L.B. High-Entropy Metal Sulfide Nanoparticles Promise High-Performance Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2002887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.; Yao, T.T.; Ma, S.Y.; Xu, Y.F.; Li, L.Z.; Han, J.C.; Fu, Q.; Li, W.H.; Yuan, Z.P.; Wang, K.X.; et al. High-Entropy Engineering of Cobalt Spinel Oxide Breaks the Activity-Stability Trade-Off in Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e12495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santodonato, L.J.; Zhang, Y.; Feygenson, M.; Parish, C.M.; Gao, M.C.; Weber, R.J.K.; Neuefeind, J.C.; Tang, Z.; Liaw, P.K. Deviation from high-entropy configurations in the atomic distributions of a multi-principal-element alloy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Sreeramagiri, P.; Babuska, T.; Krick, B.; Ray, P.K.; Balasubramanian, G. Lattice distortion as an estimator of solid solution strengthening in high-entropy alloys. Mater. Charact. 2021, 172, 110877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.R.; Pickering, E.J.; Playford, H.Y.; Stone, H.J.; Tucker, M.G.; Jones, N.G. An assessment of the lattice strain in the CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.H. Physical Properties of High Entropy Alloys. Entropy 2013, 15, 5338–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Huang, G.Y.; Zhu, G.R.; Hu, H.C.; Li, C.; Guan, X.H.; Zhu, H.B. La-exacerbated lattice distortion of high entropy alloys for enhanced electrocatalytic water splitting. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2025, 361, 124585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.C.; Zhu, H.; Fu, S.; Lan, S.; Hahn, H.; Zeng, J.R.; Feng, T. Atomic Structure Amorphization and Electronic Structure Reconstruction of FeCoNiCrMo High-Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles for Highly Efficient Water Oxidation. Small 2024, 20, 2405596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, C.G.; Tunes, M.A.; Arroyave, R.; Agren, J. On the complexity of solid-state diffusion in highly concentrated alloys and the sluggish diffusion core-effect. Calphad 2020, 68, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.J.; Fang, G.; Gao, J.J.; Wen, Y.R.; Lv, J.; Li, H.L.; Xie, G.Q.; Liu, X.J.; Sun, S.H. Noble Metal-Free Nanoporous High-Entropy Alloys as Highly Efficient Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Acs Mater. Lett. 2019, 1, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowa, J.; Danielewski, M. State-of-the-Art Diffusion Studies in the High Entropy Alloys. Metals 2020, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, S. Alloyed pleasures: Multimetallic cocktails. Curr. Sci. 2003, 85, 1404–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.H.; Lai, C.H.; Lin, S.J.; Yeh, J.W. Recent progress in multi-element alloy and nitride coatings sputtered from high-entropy alloy targets. Ann. Chim.-Sci. Mat. 2006, 31, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasscott, M.W.; Pendergast, A.D.; Goines, S.; Bishop, A.R.; Hoang, A.T.; Renault, C.; Dick, J.E. Electrosynthesis of high-entropy metallic glass nanoparticles for designer, multi-functional electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.C.; Ma, F.J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, S.L.; Duan, F.; Du, M.L.; Wang, C.L.; Zhang, W.C.; Zhu, H. Cocktail effect in high-entropy perovskite oxide for boosting alkaline oxygen evolution. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B.; Wu, R.Y.; Duan, D.B.; Liu, X.J.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.W.; Chen, S.W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Empowering multicomponent alloys with unique nanostructure for exceptional oxygen evolution performance through self-replenishment. Joule 2024, 8, 2920–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, H.F.; Chen, Z.J.; Yang, Q.; Gao, N.; Li, L.; Luo, N.; Zheng, J.; Bao, S.D.; Peng, J.; et al. High-entropy alloy enables multi-path electron synergism and lattice oxygen activation for enhanced oxygen evolution activity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.J.; Chen, J.L.; Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.Q.; Liu, H.W.; Shi, W.H.; Lin, C.; Yuan, Y.F.; Wang, Y.H.; Xia, B.Y.; et al. MoZn-based high entropy alloy catalysts enabled dual activation and stabilization in alkaline oxygen evolution. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadq6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.Q.; Xu, B.E.; Yu, X.B.; Ye, Y.H.; Liu, Y.T.; Guan, T.T.; Yang, Y.; Gao, J.L.; Li, K.X.; Wang, J.L. Activation of Lattice Oxygen in Nitrogen-Doped High-Entropy Oxide Nanosheets for Highly Efficient Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 17806–17817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmel, A.L.; Ratso, S.; Liivand, K.; Danilson, M.; Kaare, K.; Mikli, V.; Kruusenberg, I. CO2 transformed into highly active catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction via low-temperature molten salt electrolysis. Electrochem. Commun. 2024, 166, 107781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafli, E.; Ratso, S.; Ivanov, Y.P.; Gatalo, M.; Pavko, L.; Yoruk, C.R.; Walke, P.; Divitini, G.; Hodnik, N.; Kruusenberg, I. Sustainable CO2-Derived Nanoscale Carbon Support to a Platinum Catalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 5772–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, D.C.; Hsu, Y.C.; Dunand, D.C. Microstructure and properties of high-entropy-superalloy microlattices fabricated by direct ink writing. Acta Mater. 2024, 275, 120055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, A.L.; Han, S.; Shan, Y.; Chen, P.C.; Lizandara-Pueyo, C.; De, S.; Schierle-Arndt, K.; Yang, P.D. Stabilizing Ru in Multicomponent Alloy as Acidic Oxygen Evolution Catalysts with Machine Learning-Enabled Structural Insights and Screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 10268–10278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | Method | Overpotential (mV) | Dominant Mechanism/Key HEA Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (CrMnFeCoNi)Sx | Pulsed thermal shock | η@100 = 295 | High-entropy | [73] |

| (CoFeNiMnW)3O4 | MOF-derived | η@10 = 256 | AEM/LOM High-entropy | [74] |

| FeCoNiMnRuLa | Carbon thermal shock | η@10 = 281 | Lattice distortion | [79] |

| FeCoNiCrMox | Laser-evaporated inert-gas condensation | η@100 = 294 | Lattice distortion Cocktail effect | [80] |

| np-AlNiCoFeMo | Melt-spinning + dealloying | η@10 = 240 | Entropic stabilization, Sluggish diffusion | [82] |

| CoFeLaNiPt | Electrodeposition | η@10 = 377 | Cocktail effect | [86] |

| LSMFCNC | Electrospinning + calcination | η@10 = 309 | Cocktail effect | [87] |

| NP-(FeCoNi)2Nb | Electrochemical dealloying | η@100 = 305 | AEM | [88] |

| NiFeCoCrW0.2 | Arc-melting + electrochemical reconstruction | η@10 = 220 | LOM | [89] |

| MoZnFeCoNi HEA/C | Spatially confined thermal shock | η@10 = 221 | AEM/LOM | [90] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Ding, X.; Qin, H.; Tang, S.; Xu, L.; Song, F. High-Entropy Alloys for Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation: Recent Advances on Mechanism and Design. Chemistry 2025, 7, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060190

Liu L, Ding X, Qin H, Tang S, Xu L, Song F. High-Entropy Alloys for Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation: Recent Advances on Mechanism and Design. Chemistry. 2025; 7(6):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060190

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Luyu, Xiang Ding, Haotian Qin, Siyuan Tang, Linlin Xu, and Fuzhan Song. 2025. "High-Entropy Alloys for Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation: Recent Advances on Mechanism and Design" Chemistry 7, no. 6: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060190

APA StyleLiu, L., Ding, X., Qin, H., Tang, S., Xu, L., & Song, F. (2025). High-Entropy Alloys for Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation: Recent Advances on Mechanism and Design. Chemistry, 7(6), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060190