1. Introduction

Similar to the catalytic site of an enzyme, the geometric arrangement of nitrogen and oxygen atoms in the amino acid

l-Proline (

1) has the potential to catalyze asymmetric reactions—a discovery that led to a concept awarded with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2021. In the last forty years,

1 has been used as a catalyst, for example, in the asymmetric Robinson annulation [

1,

2], the aldol condensation [

3,

4], and in the stereoselective Mannich reaction [

5,

6].

1 also catalyzes an unconventional reaction via aldol condensation of α-hydroxyketones and aldehydes to give α,β-dihydroxyketones [

7,

8]. Several aspects have been discussed, such as the small size of

1, its rigidity, inexpensiveness, and ready availability [

9].

The reaction path of aldol reactions catalyzed by

1 had previously been under debate with respect to the intermediates and transition states determining the overall reaction rates and the stereoselectivity, respectively. The Houk–List pathway suggests an enamine intermediate being formed from

1 and the carbonyl substrate (

Scheme 1) [

10,

11]. In stereoselective C,C-bond formation, proline’s carboxylic acid group helps positioning a second carbonyl substrate in close proximity to the enamine moiety. While this is the rate-limiting step of aldol reactions catalyzed by

1 [

12], the enamine, which serves as the activated electron donor, is of particular importance in the understanding of catalysis by

1 and derivatives thereof. Its formation involves different intermediates and transition states including the formation of a hemiaminal after addition of the first carbonyl substrate and the tautomerization of a zwitterionic iminium intermediate to the desired enamine. The latter transition competes with the formation of a bicyclic intermediate [

13]. A direct involvement of this intermediate in stereoselective C–C-coupling has been proposed [

14], but would be incompatible with observed enantio- and diastereoselectivities; therefore, a bicyclic intermediate is considered a merely parasitic by-product that competes with enamine formation [

15].

Drawbacks of

l-proline catalysis are its only moderate stereoselectivity and the necessity for comparably large amounts of catalyst, as the catalytic activity is low. The use of N-terminal

l-proline peptides as organocatalysts seems a promising alternative [

16,

17]. It has been shown that some N-terminal

l-proline tripeptides considerably increased activity and stereoselectivity compared to catalysis by

1; however, both activity and stereoselectivity strongly depended on the choice of the

l- or

d-amino acid residue in addition to

l-proline [

18]. Effects on catalytic activity were explained by an optimal relative disposition of the secondary amine in the terminal

l-proline and the carboxylic acid group of an

l- or

d-aspartic acid amide in position three. The stereoselectivity depends on the conformation of the tripeptide [

18]; in the case of peptides of the Pro-Pro-Xaa-NH

2-type, stereoselectivity clearly correlates with the

trans/cis ratio of the Pro-Pro amide bond [

19]. The notion of optimal distance and stereochemical arrangement in tripeptides is supported by the finding that neither activity nor stereoselectivity can be improved in tetrapeptides [

20]. In the case of dipeptide catalysts, the reaction path of an aldol reaction may be more similar to the Houk–List pathway suggested for

l-proline catalysis. The presence of a carboxylic acid group seems to be beneficial for catalytic activity as the conversion in reactions catalyzed by Pro-NH

2 or Pro-Xaa-NH

2, where Xaa can be any amino acid, is considerably lower [

11,

21,

22]. Nevertheless, it could be shown that non-acidic N-terminal

l-proline di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexapeptides whose C-terminal carboxylic acid group was masked as a methyl ester were still able to catalyze aldol reactions with moderate to high yield and moderate to high enantioselectivities [

23,

24].

Another important aspect is the increased conformational flexibility of peptide catalysts in comparison to

1 which might either stabilize or destabilize the geometry of a transition state or an intermediate throughout the catalytic cycle. However, if a defined chiral environment is still provided, it might even enhance selectivity [

25,

26]. Last but not least, both the chiral environment in the stereoselectivity-determining transition state and the rate-determining transition state are affected by the puckering of the proline ring. Proline adopts basically two preferred puckerings, C

γ-

exo and C

γ-

endo [

27,

28,

29,

30], which also applies to catalytic peptides with an N-terminal proline residue [

26].

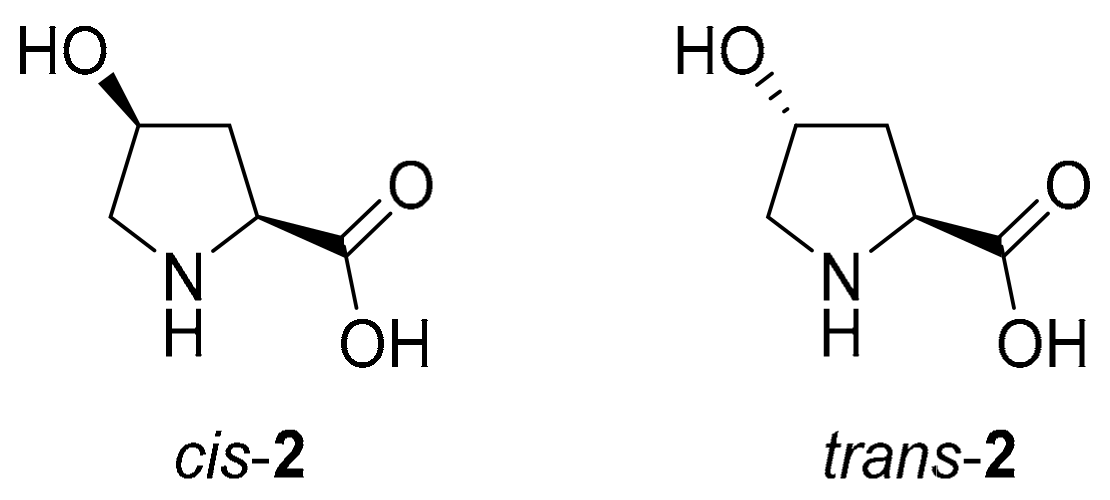

In

cis-4-hydroxyproline (

cis-4-Hyp,

cis-

2,

Figure 1), C

γ-

endo is the most preferred puckering that would also allow the formation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the

cis-4-hydroxy group and the carboxylic acid group. Similarly,

1 has a slight preference for C

γ-

endo. In contrast, in

trans-4-hydroxyproline (

trans-4-Hyp,

trans-

2,

Figure 1), the 4-hydroxy group imposes a C

γ-

exo pucker. This is in accordance with the gauche empirical rule, an effect that also contributes to the outstanding stability of the collagen triple helix [

31,

32]. Intuitively, the ring puckering should also affect the stereoselectivity of reactions catalyzed by hydroxyprolines and related peptides. Surprisingly, in different reactions tested, the stereochemical outcome of reactions (aldol, Mannich and Michael asymmetric reactions) catalyzed by

cis-

2 or

trans-

2 was similar to

1 catalysis or even lower [

33]. These observations prompted us to study the reaction channels leading to either an

R- or an

S-configured product in Hyp-catalysis or catalysis by Hyp-derived dipeptides in further detail, in particular, with respect to the role of the conformer distribution in organocatalysts, transition states, and intermediates.

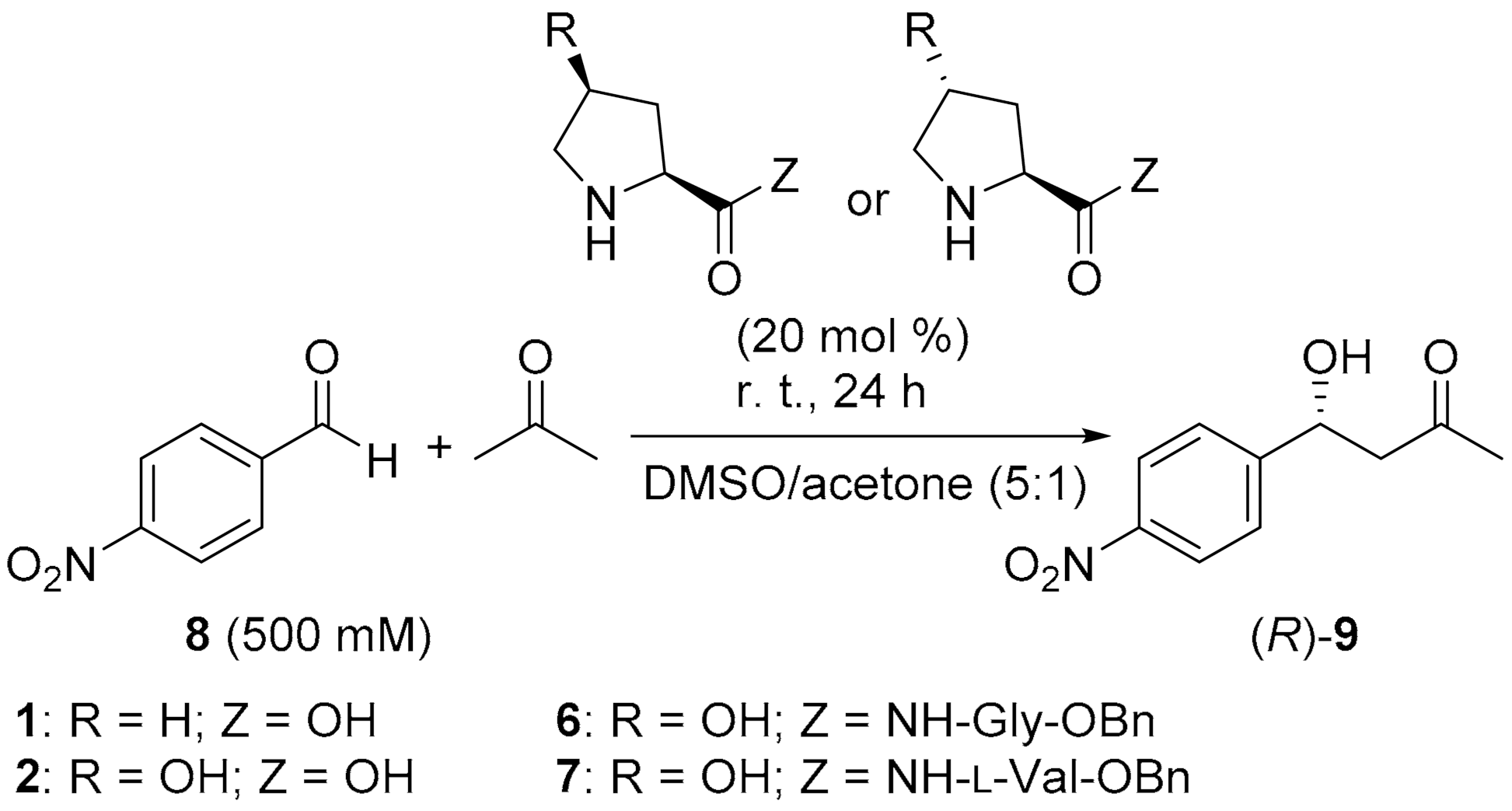

We synthesized four Hyp-derived C-terminally protected dipeptides (

cis-

6,

trans-

6,

cis-

7,

trans-

7,

Scheme 2) and performed the aldol addition of acetone to

p-nitrobenzaldehyde (

8) catalyzed by

6 or

7 as model reactions. To investigate whether catalysis of aldol additions with Hyp and Hyp-derived peptides follow a similar path as previously suggested for

l-proline, we calculated the free energy differences of transition states and intermediates in Hyp and Hyp-dipeptide catalysis at the density functional theory level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Experimental Conditions

All reagents were of analytical grade. Solvents were dried by standard methods if necessary. TLC was carried out on aluminum sheets pre-coated with silica gel 60 F254 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Detection was accomplished by UV light (λ = 254 nm). Preparative column chromatography was carried out on silica gel 60 (Merck, 40–63 µm). 1H NMR (500.3 MHz) spectra were recorded with a Avance III 500 spectrometer (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany). CDCl3 (δ = 7.26 ppm), HDO (δ = 4.81 ppm), and DMSO (δ = 2.50 ppm) were used as internal standards. 13C{1H} NMR (125.8 MHz) spectra were calibrated with CDCl3 (δ = 77.00 ppm) and DMSO-d6 (δ = 39.43 ppm) as internal standard. IR spectra were recorded with a Nicolet IR200 FTIR-spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). HR-MS spectra were measured with a micrOTOF QII mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The enantiomeric excess (ee) values of the aldol reaction products were determined by chiral phase HPLC on an HP 1100 chromatography system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA)) equipped with a Chiralpak AS-H column (Daicel, Osaka, Japan) using an n-hexane/isopropanol mixture (70:30) as eluent (UV 254 nm, flow rate 0.7 mL min−1, 25 °C).

2.2. Dipeptide Coupling

To a solution of 1.0 eq. of enantiomerically pure amino acid

cis-

3 or

trans-

3 (200 mg, 0.87 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL)

, 1.15 eq. of HOBt ( 50 mg, 1.0 mmol) were added, and the reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C, followed by addition of 1.15 eq. of the

N-terminally unprotected amino acids Gly-OBn (202 mg, 1.0 mmol) or

l-Val-OBn (243 mg, 1.0 mmol). Afterwards, 3.0 eq. (263 mg, 2.61 mmol, 361 mL) of triethylamine (TEA) were added in a single portion and the reaction solution was allowed to stir for 10 min. at 0 °C. Then, 1.15 eq. (192 mg, 1.0 mmol) of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) in dichloromethane (15 mL) were dropped gradually to the solution at 0 °C and stirred at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was extracted with 1 M HCl, sat. NaHCO

3 and finally with sat. NaCl. The collected dichloromethane layer was dried over anhyd. Na

2SO

4. The crude product was purified using column chromatography (SiO

2). All products

4 and

5 were characterized by FT-IR and

1H,

13C{

1H} NMR spectroscopy, and ESI-TOF mass-spectrometry (

Figures S2–S17).

Dipeptides cis-4 and trans-4 were isolated as colorless viscous oils in a yield of 207 mg (63%) or 315 mg (96%).

cis-4: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 7.62 (bs, 1H), 7.36–7.18 (m, 5H), 7.05 (bs, 1H), 5.08 (s, 2H), 4.85 (d, J = 8.5, 1H), 4.46–4.11 (m, 2H), 4.08–3.81 (m, 2H), 3.64–3.23 (m, 2H), 2.35–2.00 (m, 2H), 1.36 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, several rotamers) δ 174.09, 171.13, 169.52, 169.18, 155.45, 154.22, 135.20, 128.61, 128.47, 128.33, 80.72, 70.78, 69.81, 67.12, 60.36, 59.99, 59.34, 56.83, 56.00, 41.62, 38.62, 36.39, 28.33, 21.01, 14.18. IR (neat, cm-1): 3307 (OH), 1742, 1667 (CO), 1189, 1131 (C-O). MS (C19H26N2O6): calcd. 379.1869 ([M+H]+), exp. 379.1843 ([M+H]+).

trans-4: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 7.40 (bs, 1H), 7.29–7.19 (m, 5H), 6.86 (bs, 1H), 5.06 (s, 2H), 4.32 (bs, 2H), 4.08–3.84 (m, 2H), 3.82–3.25 (m, 3H), 2.36–1.90 (m, 2H), 1.33 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, several rotamers) δ = 172.34, 171.64, 170.29, 168.54, 154.78, 153.86, 134.21, 127.60, 127.48, 127.32, 79.79, 68.61, 68.15, 66.09, 59.43, 58.76, 57.68, 53.97, 40.18, 38.49, 36.47, 27.29, 20.02, 13.17. IR (neat, cm−1): 3303 (OH), 1748, 1667 (C=O), 1159, 1127 (C-O). MS (C19H26N2O6): calcd. 379.1869 ([M+H]+), exp. 379.1865 ([M+H]+).

Dipeptides cis-5 and trans-5 were isolated as colorless viscous oils in a yield of 213 mg, (59%) or 320 mg (87%).

cis-5: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 7.46 (d, J = 8.4, 1H), 7.32–7.20 (m, 5H), 6.77 (bs, 1H), 5.19–4.97 (m, 3H), 4.53–4.43 (m, 1H), 4.39 (d, J = 8.8, 1H), 4.25 (t, J = 20.2, 1H), 3.59–3.28 (m, 2H), 2.31–1.97 (m, 3H),1.38 (s, 9H), 0.82 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, several rotamers) δ 172.18, 170.16, 154.52, 134.39, 127.56, 127.39, 127.33, 79.57, 69.72, 68.80, 65.93, 59.18, 58.52, 56.69, 56.40, 55.99, 34.54, 30.20, 27.32, 17.88, 16.30. IR (neat, cm-1): 3283 (OH), 1737, 1701, 1664 (C=O), 1155, 1112 (C-O). MS (C22H32N2O6): calcd. 421.2339 ([M+H]+), exp. 421.2338 ([M+H]+).

trans-5: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 7.47 (bs, 1H), 7.33–7.11 (m, 5H), 6.63 (bs, 1H), 5.07 (q, J = 12.2, 2H), 4.55-4.20 (m, 3H), 3.92–3.15 (m, 3H), 2.45–1.77 (m, 3H), 1.35 (s, 9H), 0.81 (d, J = 6.8, 3H), 0.78 (d, J = 6.9, 3H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, several rotamers) δ = 171.98, 170.95, 170.50, 154.92, 153.93, 134.68, 134.43, 127.55, 127.34, 79.62, 68.68, 68.10, 65.89, 65.58, 59.42, 58.94, 57.54, 56.42, 56.06, 53.98, 53.37, 52.48, 38.70, 35.50, 31.09, 30.15, 27.29, 25.88, 20.01, 18.18, 18.00, 16.84, 16.51, 16.14, 13.17. IR (neat, cm−1): 3307 (OH), 1739, 1667 (C=O), 1158. MS (C22H32N2O6): calcd. 421.2339 ([M+H]+), exp. 421.2333 ([M+H]+).

2.3. Preparation of N-Deprotected Dipeptides

To a solution of 0.25 mmol of Boc-protected dipeptides

cis-

4 (95 mg)

, trans-

4 (95 mg),

cis-

5 (105 mg), or

trans-

5 (105 mg) in 1 mL dichloromethane, 0.5 mL of anisole and then 0.5 mL trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. All volatiles were removed at reduced pressure. Dipeptides

6 and

7 were obtained quantitatively as TFA salts without further purification and were characterized by

1H NMR,

13C{

1H} NMR, and FT-IR spectroscopy as well as MS spectrometry (

Figures S18–S29).

cis-6: 1H NMR (acetone-d6) δ = 7.45–7.30 (m, 5H), 5.45 (dd, J = 25.9, 7.9, 1H), 5.21 (d, J = 4.2, 1H), 5.19–5.15 (m, 2H), 4.88–4.51 (m, 2H), 4.40–3.98 (m, 3H), 3.72–3.35 (m, 2H), 2.88–2.09 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ = 174.04, 169.26, 135.26, 128.73, 128.47, 80.89, 70.91, 67.29, 59.45, 56.97, 41.75, 36.28, 29.77, 28.43. IR (neat, cm-1): 3088 (OH and NH), 1742, 1668 (C=O), 1189, 1133 (C-O). MS (C14H18N2O4): calcd. 279.1345 ([M+H]+), exp. 279.1339 ([M+H]+).

trans-6: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 10.14 (bs, 1H), 8.46 (bs, 1H), 7.86 (bs, 1H), 7.38–7.22 (m, 5H), 5.53 (bs, 2H), 5.17–4.98 (m, 2H), 4.81 (bs, 1H), 4.52 (bs, 1H), 4.07 (bs, 2H), 3.63–3.11 (m, 2H), 2.52 (bs, 1H), 1.95 (bs, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 169.66, 169.45, 135.12, 128.76, 128.70, 128.39, 127.23, 70.70, 67.56, 58.89, 54.45, 53.56, 41.66, 38.86. IR (neat, cm-1): 3088 (OH and NH), 1745, 1667 (C=O), 1178, 1134 (C-O). MS (C14H18N2O4): calcd. 279.1345 ([M+H]+), exp. 279.1339 ([M+H]+).

cis-7: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 8.03 (d, J = 9.2, 1H), 7.41–7.27 (m, 5H), 5.25–5.04 (m, 2H), 4.52 (dd, J = 9.3, 4.8, 1H), 4.41–4.26 (m, 1H), 3.86–3.71 (m, 1H), 3.12 (dd, J = 11.1, 4.6, 1H), 2.99 (dd, J = 11.1, 1.0, 1H), 2.62–2.36 (m, 2H), 2.33–2.11 (m, 2H), 2.03 (ddd, J = 26.9, 13.4, 10.9, 1H), 0.96–0.81 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ = 175.25, 171.98, 135.54, 128.65, 128.46, 128.39, 72.07, 66.97, 59.62, 56.86, 55.25, 39.82, 31.48, 19.12, 17.64. IR (neat, cm-1): 3462, 3343, 3269 (OH and NH), 1741, 1643 (C=O), 1193, 1146 (C-O). MS (C17H24N2O4): calcd. 321.1814 ([M+H]+), exp. 321.1809 ([M+H]+).

trans-7: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ = 8.24 (d, J = 9.2, 1H), 7.40–7.28 (m, 5H), 5.19 (d, J = 12.2, 1H) 5.12 (d, J = 12.2, 1H), 4.49 (dd, J = 9.3, 4.9, 1H), 4.38 (bs, 1H), 4.00 (t, J = 8.4, 1H), 3.03 (d, J = 12.3, 2H), 2.75 (m, 4H), 2.28 (dd, J = 13.8, 8.7, 1H), 2.22–2.11 (m, 1H), 1.92–1.80 (m, 1H), 0.86 (dd, J = 21.9, 6.9, 6H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ = 175.28, 171.86, 135.53, 128.67, 128.49, 128.42, 73.10, 67.03, 59.84, 56.64, 55.52, 40.32, 31.33, 19.23, 17.64. IR (neat, cm-1): 3321 (OH and NH), 1737, 1652 (C=O), 1192, 1147 (C-O). MS (C17H24N2O4): calcd. 321.1814 ([M+H]+), exp. 321.1809 ([M+H]+).

2.4. Aldol Reactions

To 8 (151 mg, 1.0 mmol) dissolved in 2 mL of an acetone/DMSO mixture (ratio 1:5, v/v) or in pure acetone, 20 mol-% of the solid catalyst 2, 6, or 7 was added after stirring overnight at room temperature. In the case of 6 and 7, TEA was added in equimolar amounts to release the free base from the TFA salt. The reaction mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate (5 mL) and washed twice with water (2 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The conversion number was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The ee with respect to (R)-9 was determined by chiral HPLC (see General Experimental Conditions). The absolute configuration of the major product was determined as R in accordance with the elution order in previously published data on chiral separations of 9.

Aldol product 9: 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ = 8.21 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H, H-arom), 7.54 (d, J = 8.6 Hz. 2H, H-arom), 5.26 (dt, J = 3.7 Hz, 7.6 Hz, 1H, CH-O), 3.58 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H, CO-CHH), 2.85 (dd, J = 3.4 Hz, 6.1 Hz, 1H, CO-CHH), 2.22 (s, 3H, CO-CH3), 1.59 (bs, 1H, OH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ = 208.47 (C=O), 149.94 (C-arom), 147.26 (C-arom), 126.37 (2 × C-arom), 123.72 (2 × C-arom), 68.86 (C-O), 51.46 (CO-CH2), 30.68 (CO-CH3).

HPLC retention time (

tR): (

R)-

9: 12.2 min; (

S)-

9: 15.4 min (

Figures S30–S39).

2.5. Quantum Chemical Calculations

Conformers of free catalysts and the intermediates of the aldol reaction cycle with

cis-

2,

trans-

2,

cis-

6, and

trans-

6 were modeled using the conformer search algorithm in SPARTAN (Wavefunction, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA).). Geometries of transition states formed from

cis-

2 and

trans-

2 were modeled based on transition state geometries previously published for

1 [

34,

35]. All geometries were optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level with a polarized continuum model (PCM) for DMSO in GAUSSIAN 16 [

36], whereby the level of theory was chosen as a compromise between accuracy and computational cost for the number of conformers that had to be optimized for this study. Geometries of transition states formed from

cis-

6 and

trans-

6 were modeled using the transition states from

cis-

2 and

trans-

2 as templates replacing the carboxylic acid –OH by Gly-OBn. Conformers were generated using a constrained conformer search with a frozen core structure, in which dihedrals were only freely rotatable for the 4-hydroxy group (provided it was not involved in the transition state) and the Gly-OBn group. Geometry optimizations at the density functional theory level were performed in a two-step procedure, first constrained (with frozen core structure) and thereafter unconstrained. Transition geometries without any precedence for

l-proline such as the stereoselective step (TS4) and the alternative path for enamine formation presented in this study were modeled using the STQN method for locating transition structures [

37]. TS4 geometries were modeled as transition states leading to an

R-configured product (TS4

pro R) and to an

S-configured product (TS4

pro S), respectively, where for TS4

pro R and TS4

pro S each two core structures were modeled: one with an

s-anti orientation of the enamine, and one with an

s-syn orientation. Additional conformers with respect to 4-OH and Gly-OBn were modeled as given above. Duplicate intermediate and transition structures were identified based on their individual interatomic distance distribution pattern as described elsewhere [

38], and removed using a script in MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). From the transition structures, only those were kept that exhibited one imaginary frequency after frequency calculations (same level as optimizations). From the transition states with a single imaginary frequency, only those were kept, where the frequency was clearly associated with a vibration along a bond to be formed or broken in the course of the transition. For the calculation of standard free energies (

G) from statistical thermodynamics in GAUSSIAN, all frequencies were uniformly scaled by 0.97. Average values for

G according to the Boltzmann weights of each contributing conformer and energy barriers were calculated in MATLAB.

Theoretical enantiomeric ratios (er)

R:

S were calculated from the ratios of the theoretical rate constants

kR and

kS for the

R- or an

S-selective reaction steps in each modeled reaction cycle [

39]. These ratios were obtained from the difference of the energy barriers ∆

Gpro R or ∆

Gpro S, i.e., the difference between free energies (Boltzmann-weighted average over different conformers) calculated for TS4

pro R or TS4

pro S, respectively, and the free energy of the enamine intermediate:

For all theoretical er values, we assumed a reaction temperature of 298.15 K.

3. Results

As a model reaction for asymmetric aldol additions, we used the addition of acetone to

8 to give the chiral β-hydroxyketone

9 where acetone acted both as a solvent and as a reactant. The use of a solvent mixture with DMSO (ratio DMSO/acetone 5:1,

v/

v) ensured that all reactants and catalyst were fully dissolved, as it has been shown that the catalytic cycle only involves soluble proline complexes or soluble proline adducts [

40]. All reactions were carried out in the presence of 20 mol-% of the catalyst as evidenced from earlier studies as the optimal catalyst concentration [

33]. After 24 h of stirring at room temperature, the overall conversion was determined by

1H NMR spectroscopy and the ee by chiral phase HPLC (see Experimental Section and

Figures S30–S39).

1,

trans-4-Hyp (

trans-

2), and

cis-4-Hyp (

cis-

2) were used as references to evaluate the efficiency of

6 and

7 as catalysts. The results are summarized in

Table 1.

Like well-known aldol additions in the presence of 1, catalysis with cis-2 and trans-2 results in virtually full conversion (>98%) after 24 h with moderate enantioselectivities in favor of the R-configured product (48% ee with cis-2 and 40% with trans-2).

The highly similar stereochemical outcome of both conversions suggests only a little influence from the 4-hydroxy group on enantioselectivity confirming previous observations [

33]. Theoretical models from previous studies on proline catalysis have shown that the stereoselectivity is determined by the relative arrangement of the double-bonded methylene group of the enamine intermediate (

Scheme 1) and the carbonyl group of the substrate. Here, a coordination of the carbonyl oxygen by the carboxylic acid group of the enamine intermediate in TS4 clearly favors an

R-configured product (TS4

pro R) as the energy barrier via TS4

pro R is lower than via a transition state TS4

pro S with opposite arrangement.

To evaluate the plausibility of a similar mechanism with

cis-

2 and

trans-

2, in analogy to previously published models for catalysis with

1, we modeled different conformers of the enamine intermediates and of transition states TS4

pro R and TS4

pro S toward product

9 with both

cis-

2 and

trans-

2 (lowest-energy conformers of TS4

pro R are depicted in

Figure 2). We calculated their respective standard free energies (

G°) at the B3LYP/6-31G(d)-level with an implicit solvent model for DMSO and determined theoretical stereoselectivities for both catalysts from the ∆

G° values calculated with both catalysts (

Table 1). The full consideration of conformational space would require modeling numerous reaction channels for individual substrate, transition state, and product conformers and the calculation of rotational barriers to model the interconversion between different conformational species. Hence, even for systems with limited conformational space, any attempt of calculating a full reaction profile would be hardly manageable. Therefore, instead of considering free energy levels of individual conformers, we calculated free energy profiles based on Boltzmann-weighted average values of

G°. This approach may be a source of error, if a reaction step going through a short-lived intermediate conformer would proceed considerably faster to the next intermediate than its accommodation in a lower-lying intermediate conformer, i.e., the energy barrier by the subsequent transition state is lower than the involved rotational barriers. In all other cases, focusing on the low-lying species within a limited set of conformers appears as a good approximation, at least to obtain a qualitative picture of the energy barriers in the catalytic cycle.

As a first benchmark for the catalytic cycles with

cis-

2 and

trans-

2, we calculated ∆

G° between enamine intermediate/substrate and TS4

pro R or TS4

pro S, respectively. The predicted er values according to the calculated ∆

G° values are somewhat higher (91:9 with

cis-

2 and 93:7 with

trans-

2) than what had been observed experimentally. Still, given the low level of theory used for our calculation and the above-mentioned focus on low-lying conformers, this is in the range of the stereochemical outcome expected for proline-catalyzed aldol reactions. Taken together, transition state geometries analogous to what had been suggested previously for aldol reactions catalyzed by

1 seem to apply as well for aldol additions catalyzed by

cis- or

trans-

2. Depending on reaction conditions, however, the ee of such reactions may be moderate, as the difference between energy barriers going through TS4

pro R and TS4

pro S is small. Interestingly, but in accordance with the experiment, the 4-hydroxy-group has little impact on the transition states shown in

Figure 2, yet may have implications on ring puckering, which leads to different geometries of the lowest-energy conformers of TS4

pro R with

cis-

2 (

Figure 2A) and

trans-

2 (

Figure 2B).

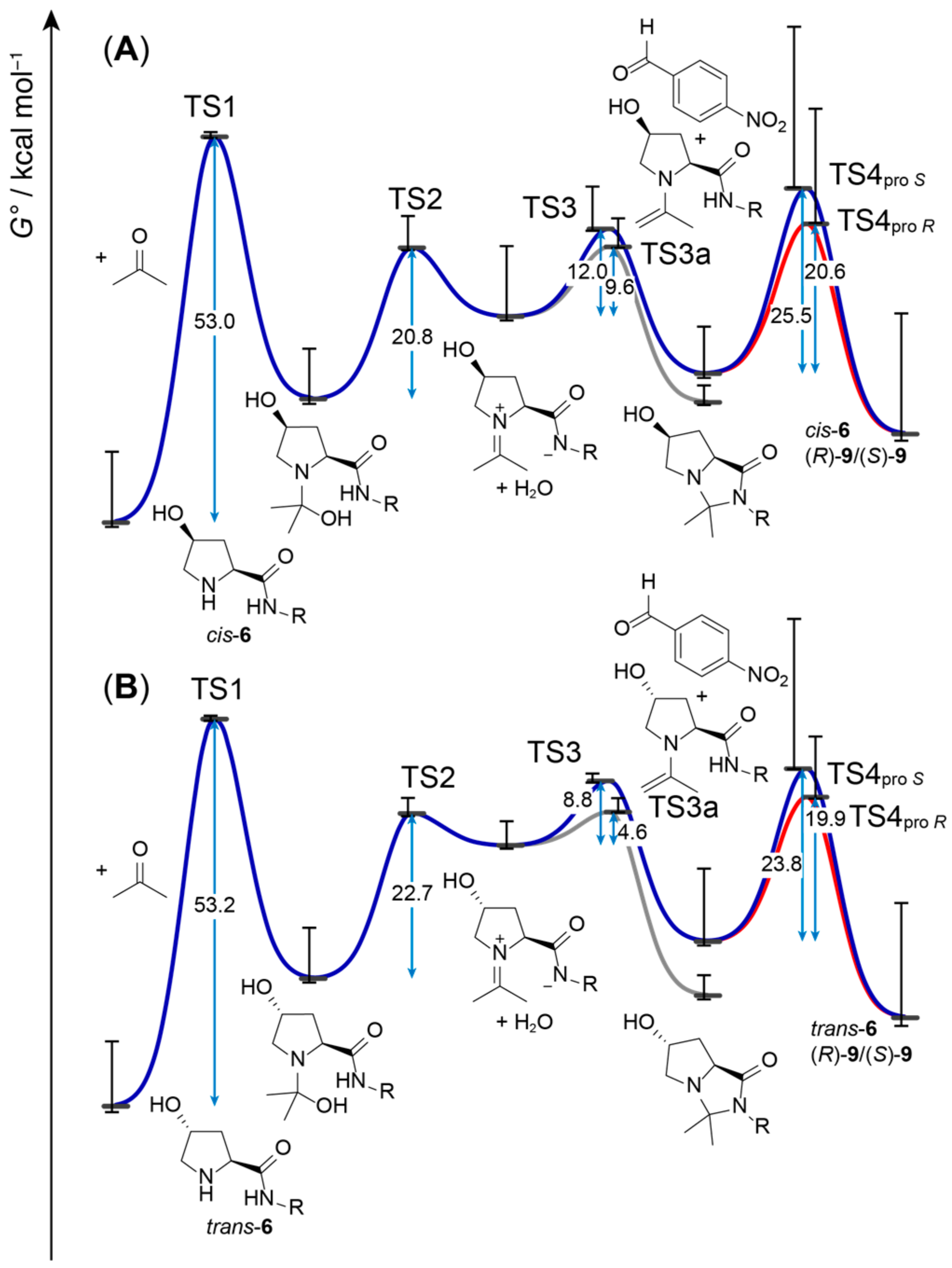

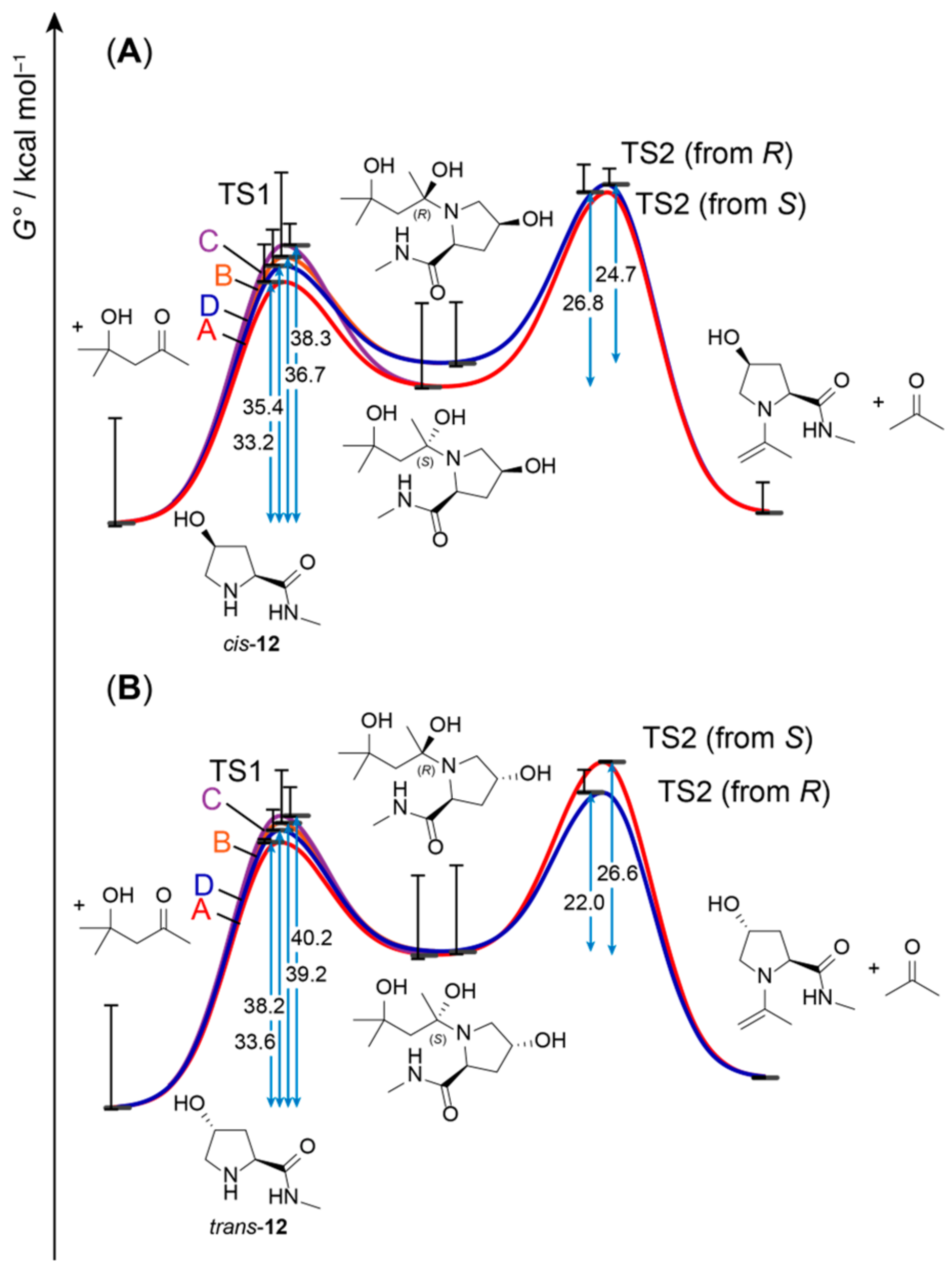

With both

cis-

2 and

trans-

2, we observed virtually full conversion (>98%) after 24 h. While C,C-bond formation is rate-limiting [

12], the rate of this second-order step also depends on the concentration of the enamine intermediate, whose formation itself had previously been discussed as rate-limiting for proline-catalyzed aldol reactions [

41]. To obtain a full picture of formation of enamine in the aldol reaction catalyzed by

cis-

2 in comparison to

trans-

2, we also modeled geometries of the preceding intermediates and transition states (TS1, TS2, and TS3), from formation of the hemiaminal from catalyst and acetone through the iminium intermediate to the enamine (

Figure 3). To provide a rough estimate of the error due to our treatment of the conformer problem, we also plotted respective ∆

G° with highest- and lowest-energy conformers as ‘whiskers’ attached to each substrate, intermediate, transition, or product state. As given in

Scheme 1, we also included a parasitic side path to a putatively formed bicyclic byproduct from the iminium intermediate via TS3a in our models of reaction cycles with

cis-

2 and

trans-

2. The calculated energy barriers are reasonable in the boundaries of the accuracy of the model and are like what had been obtained for proline-catalyzed reactions previously. Differences in the energy profile of the

cis-

2 and

trans-

2 reaction cycle are small, except for the energy of the iminium intermediate being slightly lower in the

cis-

2 cycle. However, as the energy associated with hemiaminal formation, whose rate is additionally limited by concentration of reactants and the corresponding frequency factor (not considered in

Figure 3), is the highest, minor differences in subsequent reaction steps should not be rate-determining. Therefore, it is not surprising that we observe very similar conversion with both catalysts after 24 h.

Reactions with catalysts cis-6 and trans-6 show with 5 and 40% low conversion after 24 h yet are highly enantioselective (98% ee). Reactions catalyzed by cis-7 and trans-7 confirm the moderate conversion (36% and 42%) and high enantioselectivities (94% and 98% ee, respectively).

In analogy to cis-2 and trans-2, we also modeled conformers of the enamine intermediates and the transition states TS4pro R and TS4pro S with cis-6 and trans-6. Due to the flexible benzylglycinate moiety, in comparison to catalysis with 1 or 2, conformational space is considerably larger. To take this into account, we modeled 47 conformers of the cis-enamine and 99 of the trans-species and altogether 12 transition structures for the cis species (4 for TS4pro R and 8 for TS4pro S) and 24 for the trans-species (9 for TS4pro R and 15 for TS4pro S). Different from 1 and 2 catalysis, with 6, conformers may exist that are energetically favorable, but incompatible with the transition state, for example, due to steric interference of the flexible benzylglycinate terminus with the catalytic site. Nevertheless, the theoretical rates for formation of (R)-9 vs. (S)-9 calculated based on Boltzmann-averaged ΔG° show a clear preference for the R-product (er > 99:1), which agrees with the high enantioselectivity observed experimentally. While the energy barriers associated with TS4pro R and TS4pro S highly vary according to the respective transition geometry conformers, the aldol reaction seems to occur predominantly via low-lying conformers of TS4pro R.

Since the proline catalysis-derived transition states of the stereoselective step of

cis-

6 and

trans-

6 catalysis successfully predict the actually observed enantioselectivities, in analogy to catalysis with

2, we also modeled the preceding steps of aldol additions catalyzed by

cis-

6 and

trans-

6 (

Figure 4). In comparison to

1 or

2, the involved energy barriers are considerably higher, in particular, the one that corresponds to hemiaminal formation. The high barriers are due to the fact that proton transfers that are mediated by the carboxylic acid group in

1 and

2 must be undertaken by an amide in

cis-

6 and

trans-

6. Given the high p

K associated with amide deprotonation (approximately 25 in DMSO) [

42], intermediary formation of an amidate in analogy to a carboxylate, as with

1 or

2, is very unlikely. Such proton transfers would be involved in TS1, formation of the hemiaminal (

Figure 5A), and in TS2, elimination of water from the hemiaminal to form an iminium zwitterion. Our attempts to model TS1 involving proton transfer from the amide failed (

Figure S1); however, we were able to obtain an alternative transition geometry as previously suggested by Rankin et al. for proline [

35], where the hydroxylate formed upon nucleophilic attack of the nitrogen to the carbonyl takes up the proton directly from the amine instead of the amide (

Figure 5B). Still, given the high energy barrier of more than 50 kcal mol

−1 that must be overcome for the formation of a hemiaminal from the peptide and acetone (

Figure 4), a catalytic cycle as in

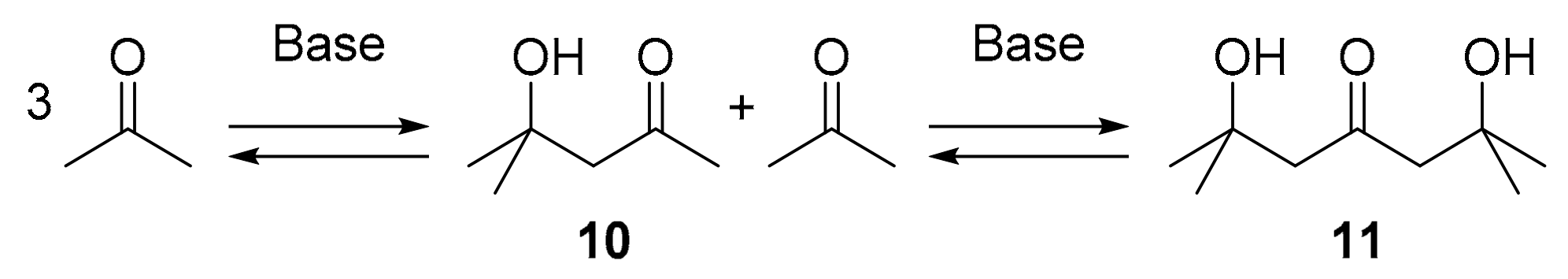

Scheme 1 appears highly unlikely, as such a reaction would not take place at room temperature. Therefore, the whole catalytic cycle, starting with hemiaminal formation to formation of the crucial enamine intermediate, must be different in aldol additions catalyzed by peptides, in particular, those that do not feature a residue that could act as a proton donor.

If proton transfer is not mediated by the peptide catalyst, it must occur from somewhere else. Considering the solvent DMSO as a poor proton donor, possible proton donor candidates present in the reaction solution are triethylammonium (from deprotonation of TFA salt present after Boc deprotection) or water molecules (released and taken up during reaction cycle). However, for statistical reasons, involvement of either of these very weak acids in TS1 is not very likely, as the collision frequency of three molecules in such a single third-order reaction step is expected to be very low. Furthermore, it has been shown that the presence of water has an inhibitory effect on proline-catalyzed aldol additions [

43]. The last remaining candidate for a proton donor in TS1 would be the substrate, acetone, itself. A clear acetone dependence of conversion in aldol additions has been demonstrated for formation of

9 catalyzed by

l-prolineamide, a catalyst lacking a proton-donating group such as

6 and

7: while the yield was <10% at 20 vol% acetone [

44], an increase to 80% had been observed in neat acetone [

45]. As a transition state where one acetone molecule protonates the other in a third-order reaction step appears highly unlikely, we abandoned the idea of considering acetone itself as a proton donor. Nevertheless, an acetone content-dependent conversion would still be observed, if, instead of acetone itself, some kind of ‘auxiliary substrate’ with proton donor properties was fed into the catalytic cycle, whose concentration depends on acetone content. A promising candidate for such an auxiliary is the acetone self-adduct

10, which is formed from two acetone molecules halfway to trimeric acetone

11 (

Scheme 3). In the presence of a base (here

6),

10 should be present to a certain extent (equilibrium constant of

K = 0.04) [

46,

47].

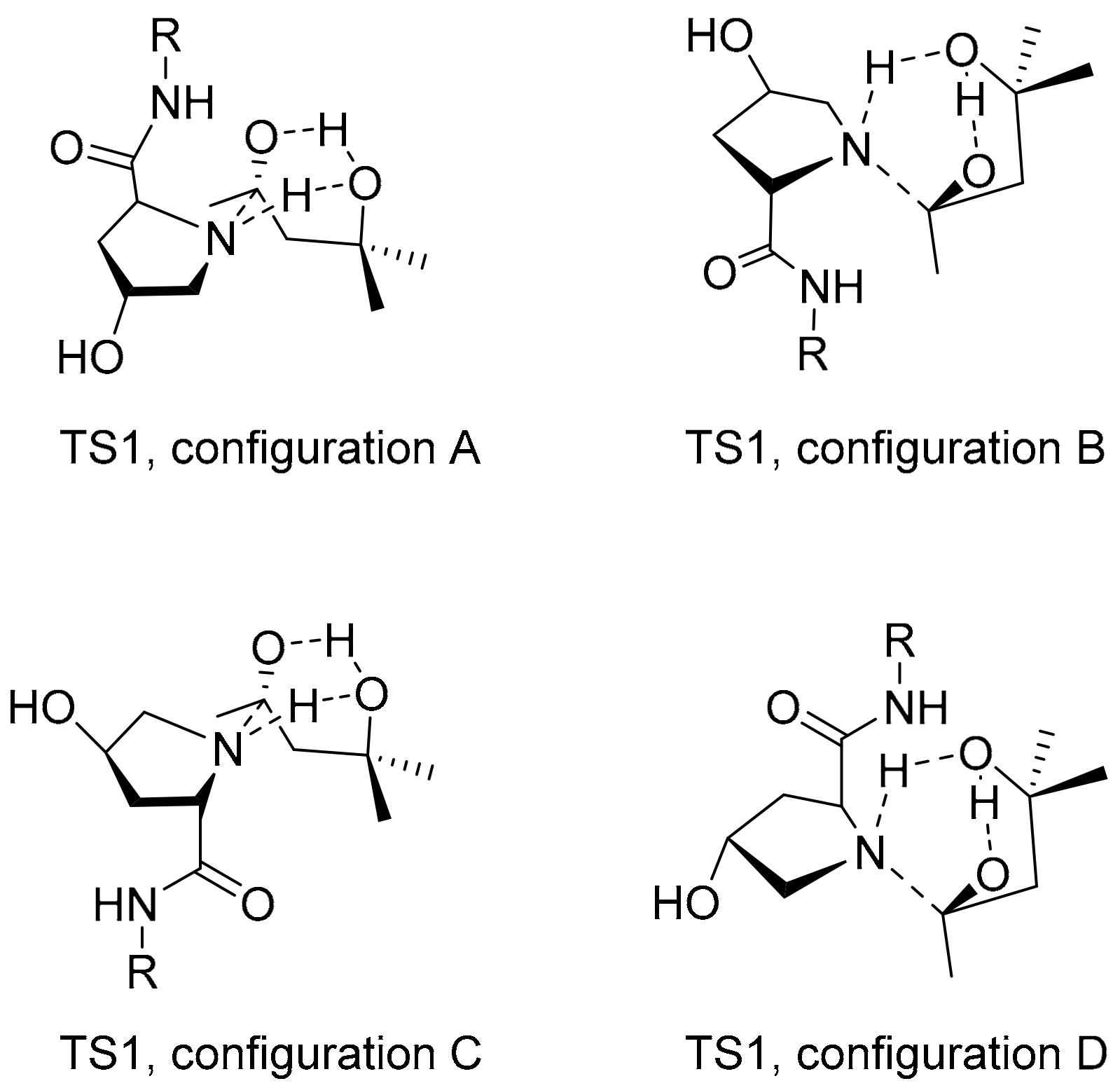

Assuming that with a peptide catalyst, a hemiaminal is not formed from catalyst and acetone, but from acetone and

10, proton transfer would be conveniently mediated by the β-hydroxy group of

10. Due to reduced symmetry of

10 in comparison to acetone, such a transition state could be modeled with four different configurations, of which two transition state configurations lead to an

R-configured hemiaminal, and two to an

S-configured hemiaminal (

Figure 6). Each of the four configurations allow a comparably ‘relaxed’ transition geometry comprising a six-membered ring formed from the atoms that are involved in C,C-bond formation and proton transfer.

Similarly, starting from either an

R- or an

S-configured hemiaminal intermediate, formation of the enamine could as well occur via a cyclic transition state (

Scheme 4). This way, the enamine is formed without the necessity of proton transfer via amide deprotonation, which would also make the formation of a parasitic bicyclic by-product less likely.

We calculated the transition states and intermediates from

Figure 6 and

Scheme 4 with 4-hydroxy-

N-methyl-

l-prolinamide (

12) as a model peptide (

Figure 7). Indeed, with 33.2 kcal/mol for TS1 (configuration A) with

cis- and 36.6 kcal/mol for TS1 (configuration A) with

trans-

12, the energy barriers associated with hemiaminal formation are much lower than those found with transition geometries as in

Figure 5B. Therefore, the mechanism involving

10 as a mediator does present a plausible alternative, albeit coming at the cost of a low proportion of active intermediates, as only small amounts of

10 are available. This is reflected by the considerably lower conversion observed with peptides instead of free amino acids (

Table 1). With the concentration of

10 being a crucial determinant of rate and conversion, any parameter with an influence on the proportion of

10 may have an impact on conversion, such as temperature, catalyst solubility, acid/base conditions in the reaction vessel (avoiding the term ‘pH’ in the context of a DMSO solution), and the amount of excessive acetone. As particularly the latter can be easily modified, we also performed conversions in the presence of

6 and

7 in pure acetone (

Table 2). As expected, the overall conversion slightly increases. Furthermore, differences in conversion between

cis- and

trans-configured catalysts vanish, which suggests that the very first step, the one that depends on acetone concentration, is rate-determining.

For the aldol additions catalyzed by

cis-

6 and

trans-

6, the high stereoselectivity reported above is fully retained in pure acetone. In contrast, it is virtually lost with both diastereomers of

7, the catalyst with a sterically demanding

l-Val sidechain. Furthermore, despite high substrate conversion, considerable formation of by-products was observed both in the presence of

cis-

7 and

trans-

7 (

Figures S38 and S39)

. Possibly, in pure acetone, where higher amounts of

10 or even trimer

11 are present, alternative pathways may exist involving acetone self-adduct intermediates even at the stereoselective C,C-coupling step. If this was the case, different behavior between peptide catalysts with a more- and less sterically demanding environment around the catalytic site would be plausible.