Advancements in Nanotheranostic Approaches for Tuberculosis: Bridging Diagnosis, Prevention, and Therapy Through Smart Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

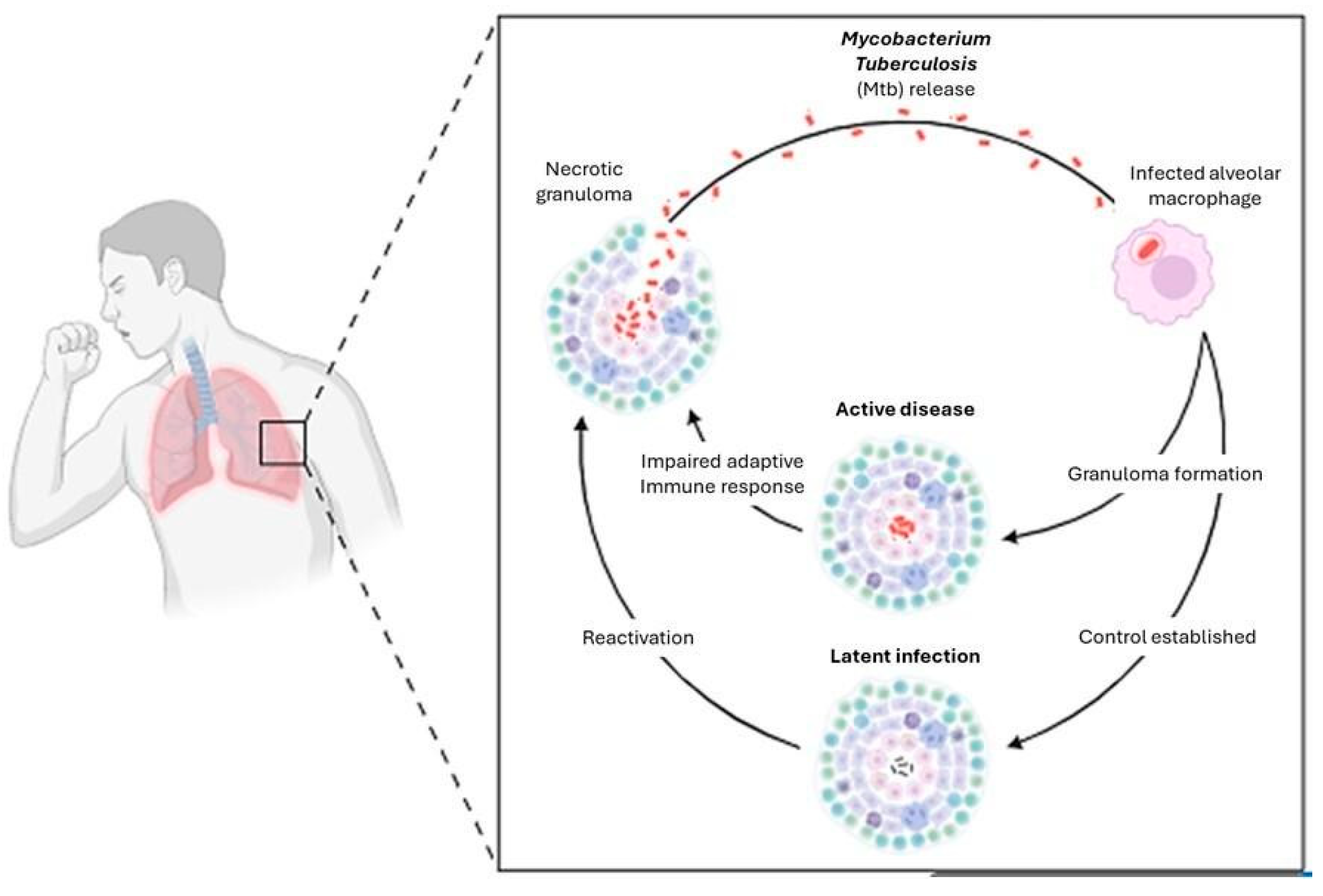

1.1. General Characteristics of the Disease

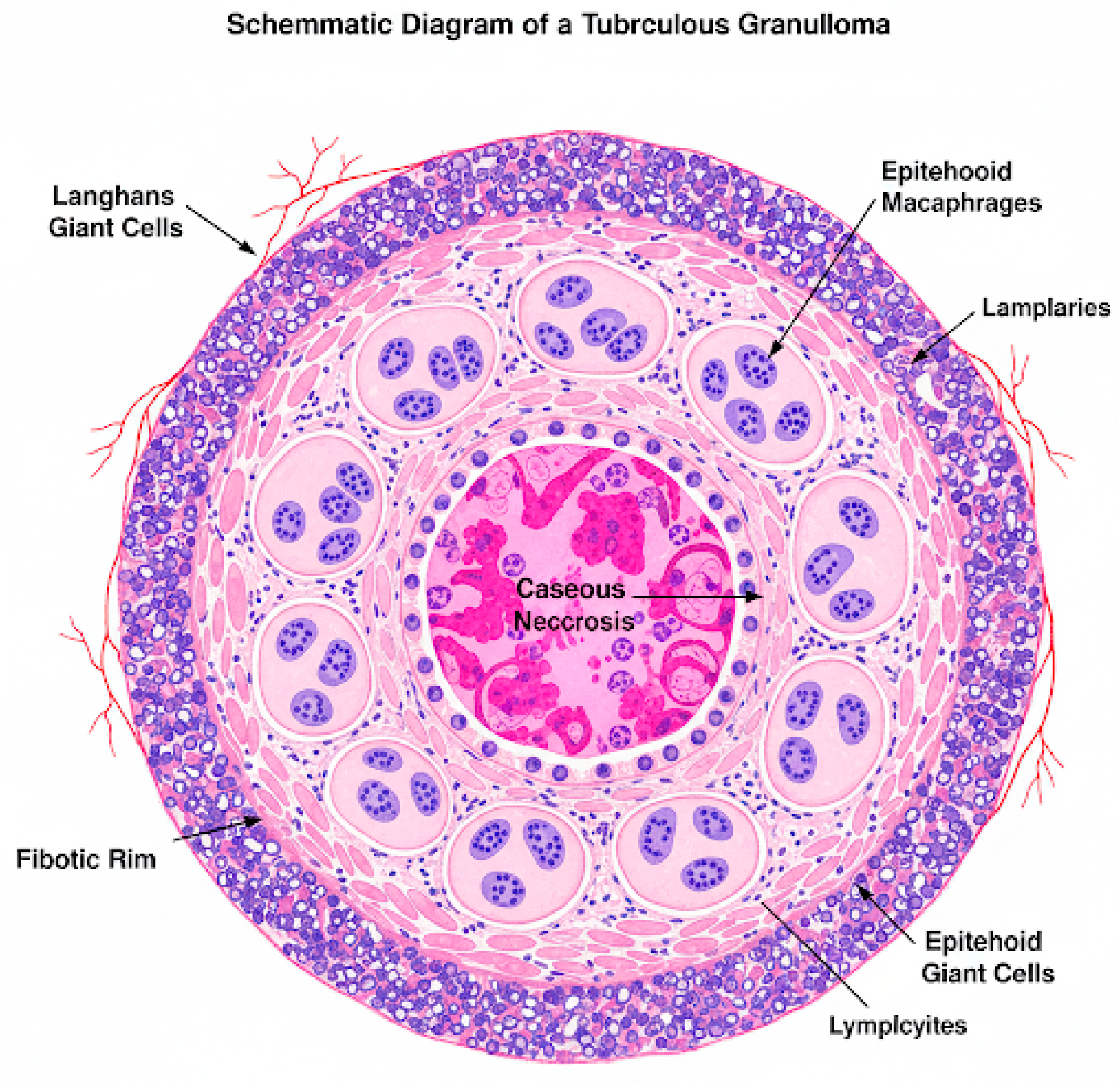

1.2. Pathophysiology of the Disease

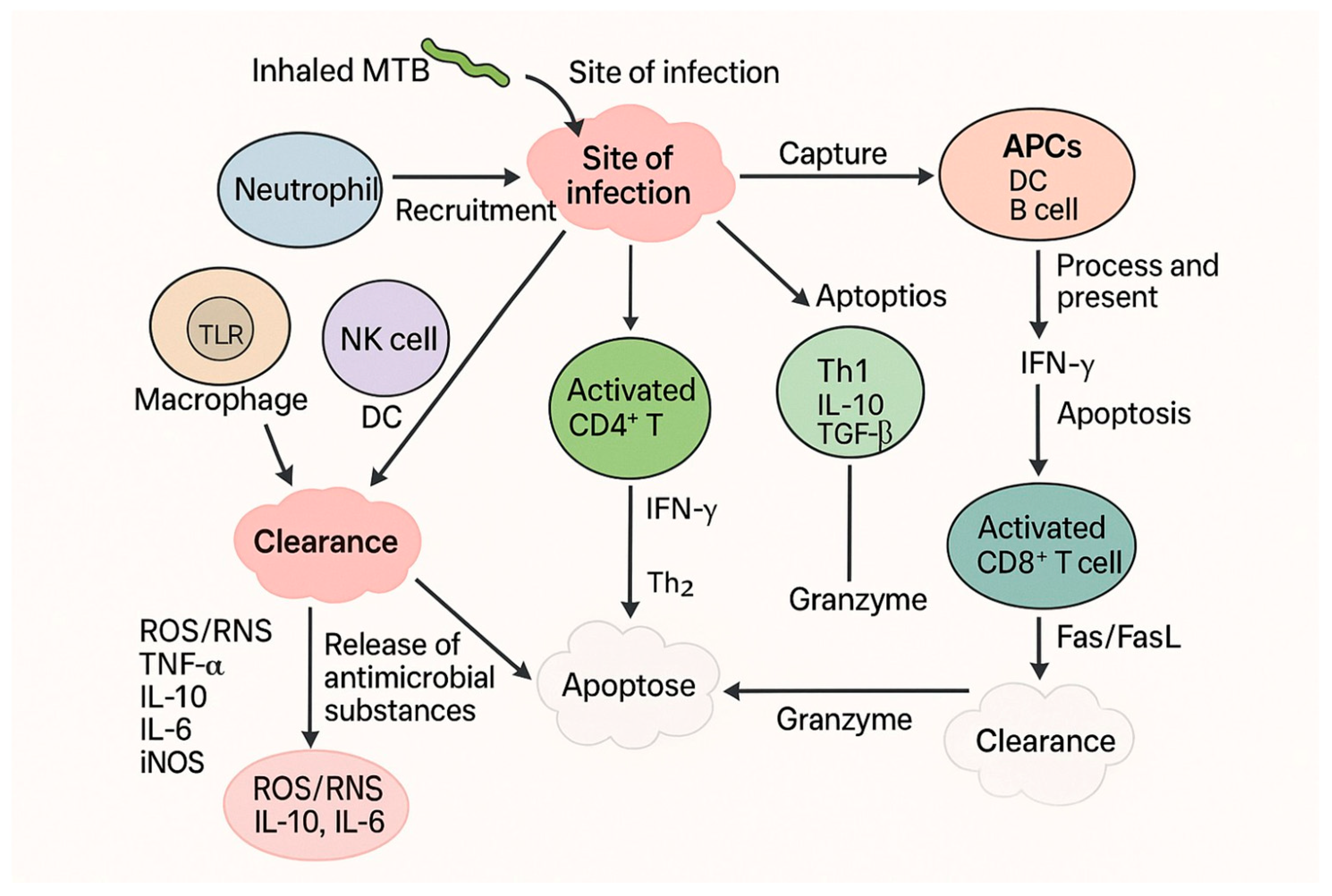

1.3. Host Immune Response Triggered by Disease and Potential Therapeutic Strategies

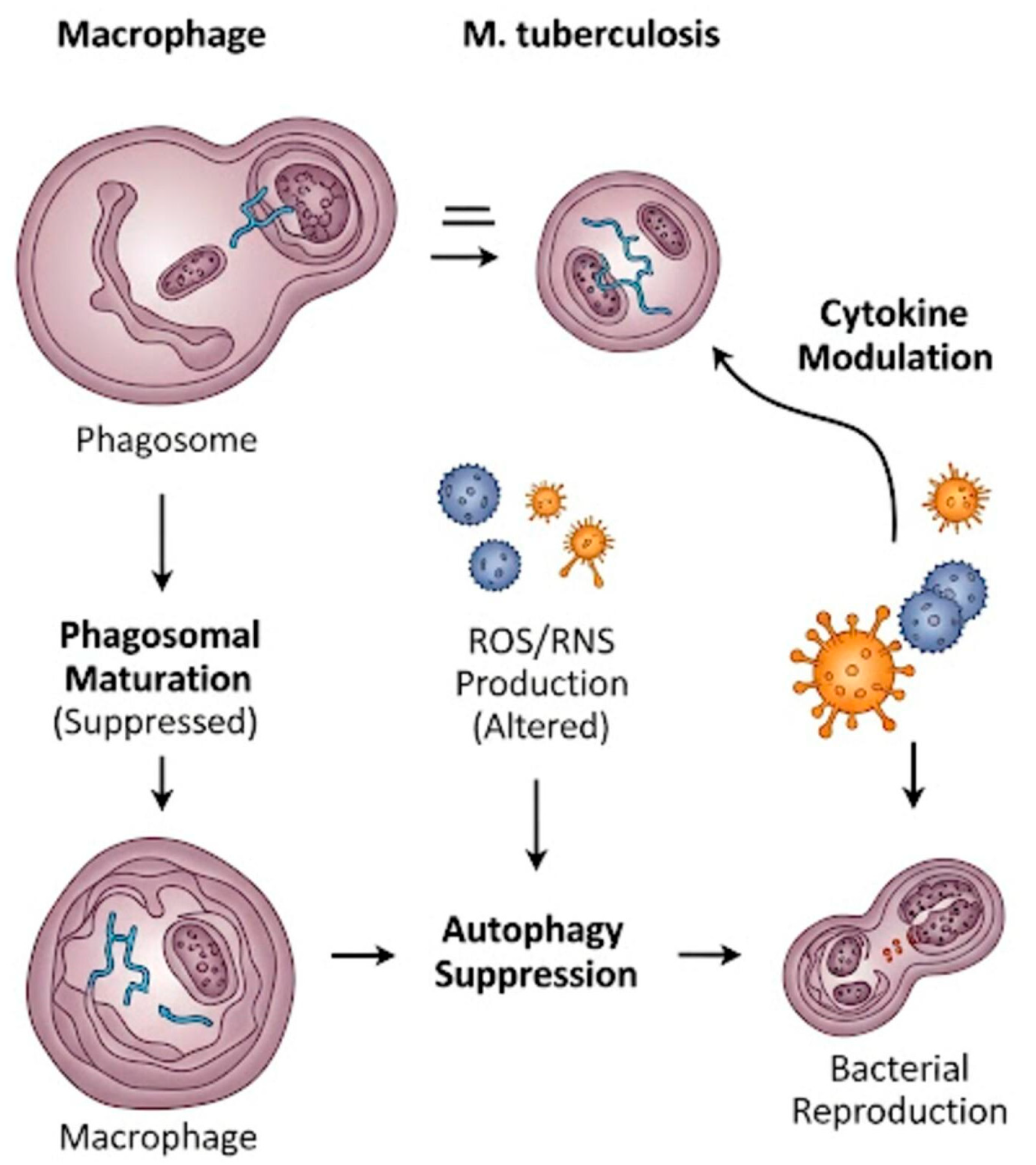

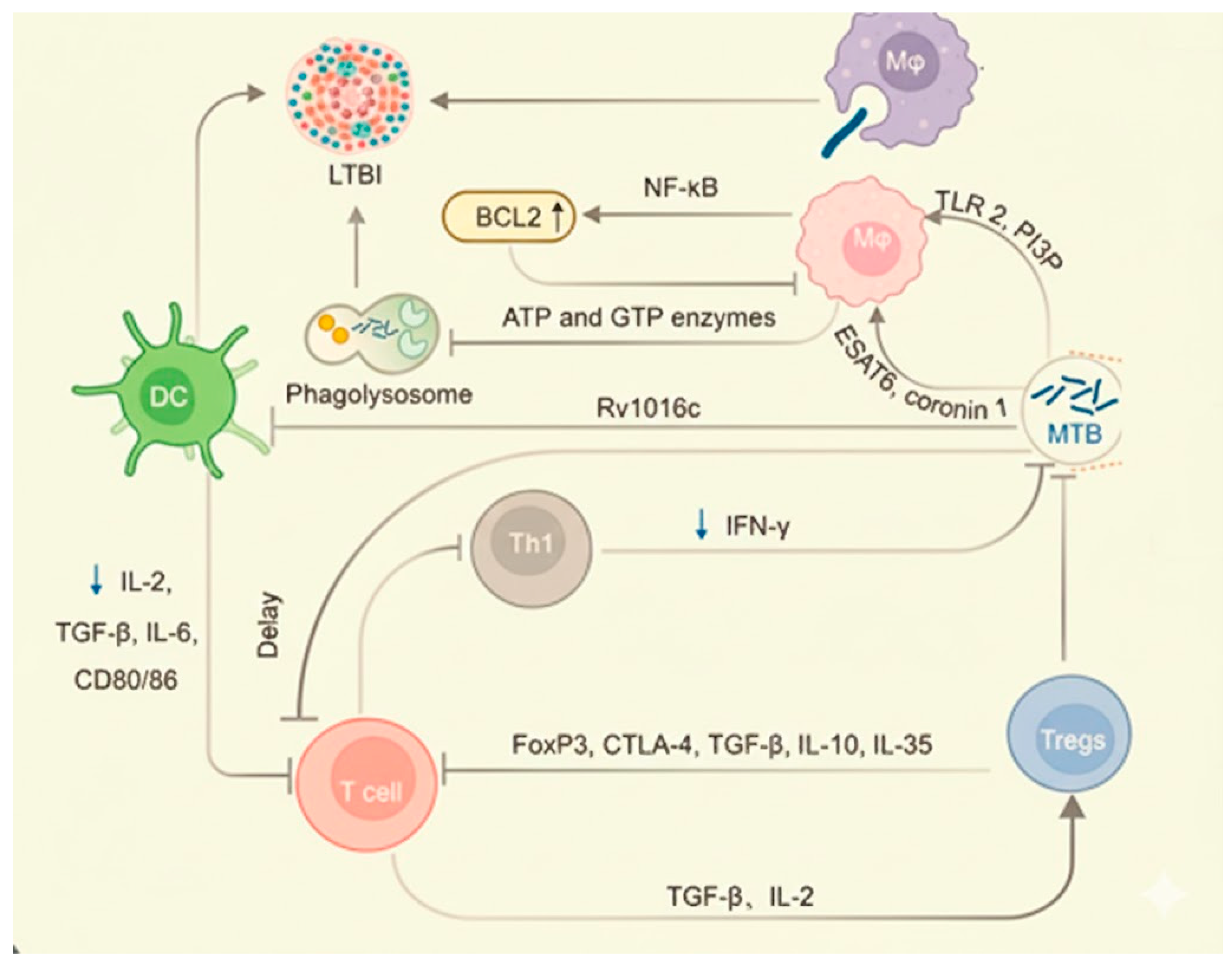

1.4. Role of Macrophages in Tuberculosis and Potential Therapeutic Strategies

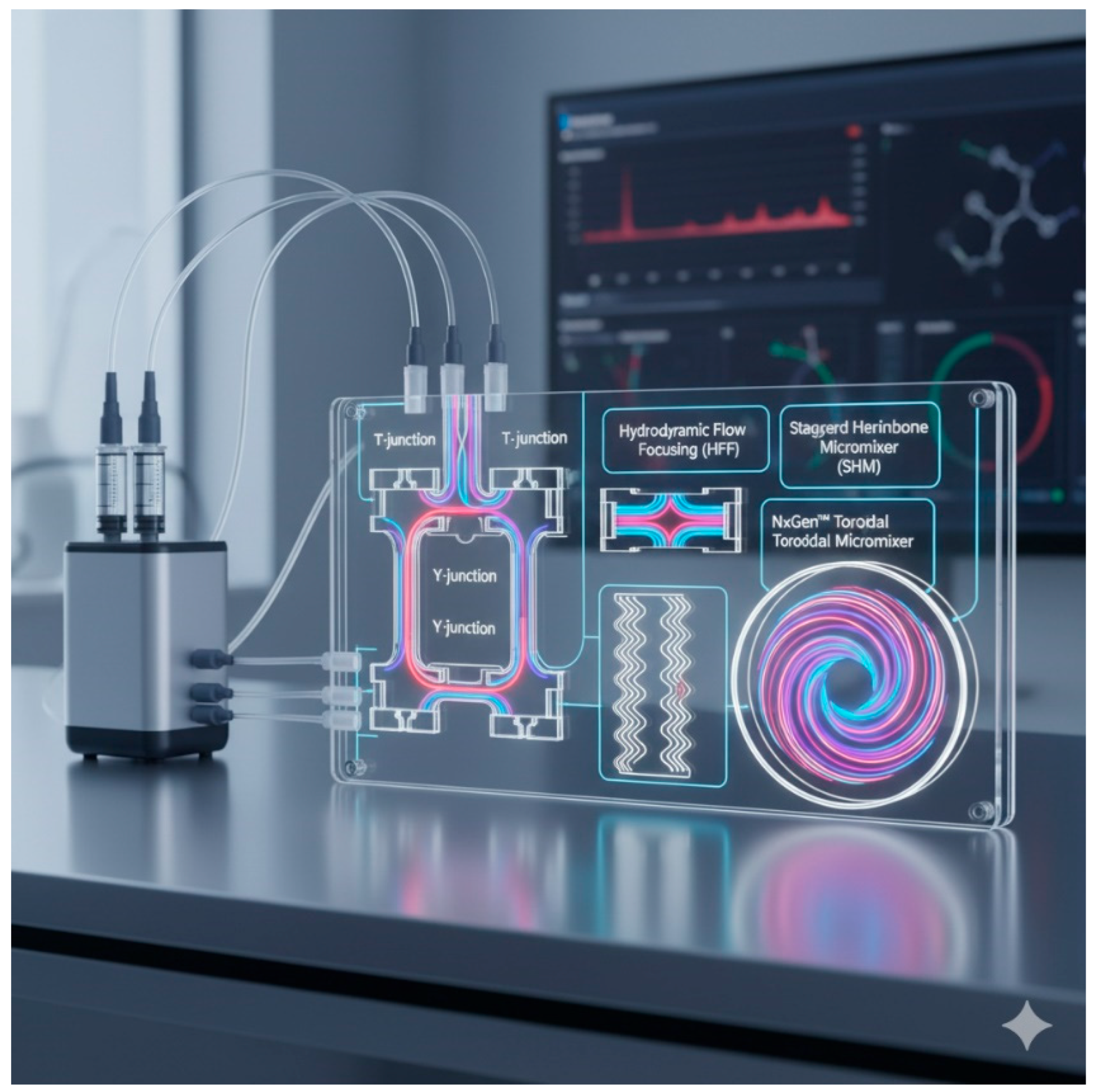

1.5. Nanotechnology’s Potential to Provide Effective Treatment Solutions for Tuberculosis and Challenges for Inhalable Anti-TB Drugs: Nanocarrier-Based Drug Delivery Systems

1.6. From Nanomedicine to Nanotheranostics: Integrating Diagnosis and Therapy

1.7. Theranostic Design Principles and Engineering Considerations

1.8. Future Perspectives and the Need for Integrated Theranostic Strategies

1.9. Current Prevention of Tuberculosis

1.10. New Vaccination Strategies for Disease Prevention and Potential Solutions Offered by Nanotechnology

2. Host-Directed Therapy (HDT) as an Alternative Tuberculosis Treatment Strategy and the Potential of Nanocarriers

2.1. General Considerations on the Concept of Host-Directed Therapies (HDT)

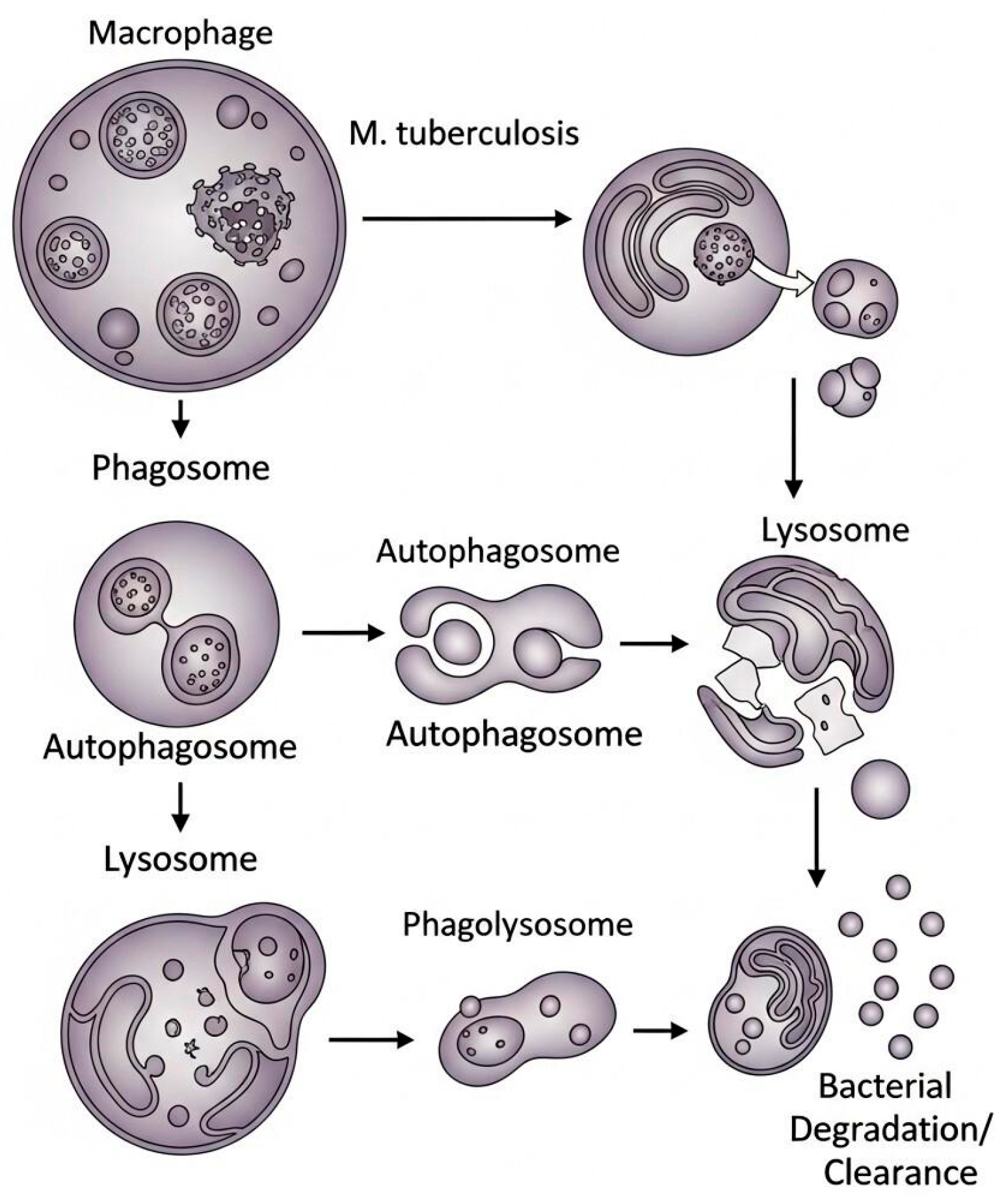

2.2. Therapies Targeting Autophagy in Tuberculosis

Role of Nanocarriers in Autophagy in Tuberculosis-Infected Macrophages

2.3. Nanocarriers for Macrophage Targeting Delivery

2.4. Nanocarriers Inhibit Apoptosis and Induce Macrophage Polarization in Tuberculosis-Infected Macrophages

3. Summary of Nanomaterials as an Alternative Strategy for Tuberculosis Treatment

4. Nanocarriers for Tuberculosis Prevention

4.1. Host Immunological Response to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection

4.2. Nanovaccines for Tuberculosis

4.3. Nucleic Acid-Based (DNA and RNA) Vaccines for Tuberculosis

4.4. Protein-Based Nanovaccines for Tuberculosis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2024 Global Tuberculosis Report; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maison, D.P. Tuberculosis pathophysiology and anti-VEGF intervention. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2022, 27, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memariani, H.; Memariani, M.; Eskandari, S.E.; Ghasemian, A.; Neamatollahi, A.N. The potential role of probiotics and their bioactive compounds in the management of pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.L. The Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis—The Koch Phenomenon Reinstated. Pathogens 2020, 9, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, D.; Redinger, N.; Schwarz, K.; Li, F.; Hädrich, G.; Cohrs, M.; Dailey, L.A.; Schaible, U.E.; Feldmann, C. Amorphous Drug Nanoparticles for Inhalation Therapy of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 9478–9486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoza, L.J.; Kumar, P.; Dube, A.; Demana, P.H.; Choonara, Y.E. Insights into innovative therapeutics for drug-resistant tuberculosis: Host-directed therapy and autophagy inducing modified nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 622, 121893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelofse, S.; Esmail, A.; Diacon, A.H.; Conradie, F.; Olayanju, O.; Ngubane, N.; Howell, P.; Everitt, D.; Crook, A.M.; Mendel, C.M.; et al. Pretomanid with bedaquiline and linezolid for drug-resistant TB: A comparison of prospective cohorts. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2021, 25, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.M.; Minko, T. Pharmacokinetics of inhaled nanotherapeutics for pulmonary delivery. J. Control. Release 2020, 326, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J.E.C.; Yalovenko, T.; Riaz, A.; Kotov, N.; Davids, C.; Persson, A.; Falkman, P.; Feiler, A.; Godaly, G.; Johnson, C.M.; et al. Inhalable porous particles as dual micro-nano carriers demonstrating efficient lung drug delivery for treatment of tuberculosis. J. Control. Release 2024, 369, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahlool, A.Z.; Cavanagh, B.; Sullivan, A.O.; MacLoughlin, R.; Keane, J.; Sullivan, M.P.O.; Cryan, S.-A. Microfluidics produced ATRA-loaded PLGA NPs reduced tuberculosis burden in alveolar epithelial cells and enabled high delivered dose under simulated human breathing pattern in 3D printed head models. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 196, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Xie, S.; Li, Z.; Dong, S.; Teng, L. Precise nanoscale fabrication technologies, the “last mile” of medicinal development. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 2372–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokesch-Himmelreich, J.; Treu, A.; Race, A.M.; Walter, K.; Hölscher, C.; Römpp, A. Do Anti-tuberculosis Drugs Reach Their Target?─High-Resolution Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging Provides Information on Drug Penetration into Necrotic Granulomas. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 5483–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronan, M.R. In the Thick of It: Formation of the Tuberculous Granuloma and Its Effects on Host and Therapeutic Responses. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 820134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canales, C.S.C.; Cazorla, J.I.M.; Cazorla, R.M.M.; Roque-Borda, C.A.; Polinário, G.; Banda, R.A.F.; Sábio, R.M.; Chorilli, M.; Santos, H.A.; Pavan, F.R. Breaking barriers: The potential of nanosystems in antituberculosis therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 39, 106–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, G.; Faisal, S.; Dorhoi, A. Microenvironments of tuberculous granuloma: Advances and opportunities for therapy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1575133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, K.; Kokesch-Himmelreich, J.; Treu, A.; Waldow, F.; Hillemann, D.; Jakobs, N.; Lemm, A.-K.; Schwudke, D.; Römpp, A.; Hölscher, C. Interleukin-13-Overexpressing Mice Represent an Advanced Preclinical Model for Detecting the Distribution of Antimycobacterial Drugs within Centrally Necrotizing Granulomas. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0158821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, P.; Polak, M.E.; Reichmann, M.T.; Leslie, A. Understanding the tuberculosis granuloma: The matrix revolutions. Trends Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevel, R.; Pernet, E.; Tran, K.A.; Sadek, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Lapshina, E.; Jurado, L.F.; Kristof, A.S.; Moumni, M.; Poschmann, J.; et al. β-Glucan reprograms alveolar macrophages via neutrophil/IFNγ axis in a murine model of lung injury. eLife 2025, 13, RP102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.D.; Koch, B.E.V.; van Veen, S.; Walburg, K.V.; Vrieling, F.; Guimarães, T.M.P.D.; Meijer, A.H.; Spaink, H.P.; Ottenhoff, T.H.M.; Haks, M.C.; et al. Functional Inhibition of Host Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) Enhances in vitro and in vivo Anti-mycobacterial Activity in Human Macrophages and in Zebrafish. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagdev, P.K.; Agnivesh, P.K.; Roy, A.; Sau, S.; Kalia, N.P. Exploring and exploiting the host cell autophagy during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 1297–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Qinglai, T.; Yang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Lei, L.; Li, S. Pulmonary inhalation for disease treatment: Basic research and clinical translations. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 25, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kam, J.Y.; Cheng, T.; Garland, D.C.; Britton, W.J.; Tobin, D.M.; Oehlers, S.H. Inhibition of infection-induced vascular permeability modulates host leukocyte recruitment to Mycobacterium marinum granulomas in zebrafish. Pathog. Dis. 2022, 80, ftac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoteso, O.A.; Fadaka, A.O.; Walker, R.B.; Khamanga, S.M. Innovative Strategies for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Advances in Drug Delivery Systems and Treatment. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Tewes, F.; Aucamp, M.; Dube, A. Formulation and clinical translation of inhalable nanomedicines for the treatment and prevention of pulmonary infectious diseases. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 2967–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Ding, L.; Liu, G. Nanoparticle formulations for therapeutic delivery, pathogen imaging and theranostic applications in bacterial infections. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1545–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinnawo, C.A.; Dube, A. Clinically Relevant Metallic Nanoparticles in Tuberculosis Diagnosis and Therapy. Adv. Ther. 2025, 8, 2400189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wang, W.; Zhao, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Yan, D.; Gao, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Y.; et al. Photothermal therapy of tuberculosis using targeting pre-activated macrophage membrane-coated nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszogrodzka, G.; Dorożyński, P.; Gil, B.; Roth, W.J.; Strzempek, M.; Marszałek, B.; Węglarz, W.P.; Menaszek, E.; Strzempek, W.; Kulinowski, P. Iron-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks as a Theranostic Carrier for Local Tuberculosis Therapy. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, G.T.; Gularte, M.S.; Vogt, A.G.; Giongo, J.L.; Vaucher, R.A.; Echenique, J.V.; Soares, M.P.; Luchese, C.; Wilhelm, E.A.; Fajardo, A.R. Polysaccharide-based film loaded with vitamin C and propolis: A promising device to accelerate diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 552, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, V.V.; Lepekhina, T.B.; Alliluev, A.S.; Bidram, E.; Sokolov, P.M.; Nabiev, I.R.; Kistenev, Y.V. Quantum Dot-Based Nanosensors for In Vitro Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Duan, H.; Cao, T.; Dai, G.; Sheng, G.; Chu, H.; Sun, Z. Macrophage-targeted nanoparticles mediate synergistic photodynamic therapy and immunotherapy of tuberculosis. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 1727–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, M.; Soria-Carrera, H.; Wohlmann, J.; Dal, N.-J.K.; de la Fuente, J.M.; Martín-Rapún, R.; Griffiths, G.; Fenaroli, F. Subcellular localization and therapeutic efficacy of polymeric micellar nanoparticles encapsulating bedaquiline for tuberculosis treatment in zebrafish. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 2103–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, H.; Peng, C.; Yasin, P.; Shang, Q.; Xiang, W.; Song, X. Mannosamine-Engineered Nanoparticles for Precision Rifapentine Delivery to Macrophages: Advancing Targeted Therapy Against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 2081–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Li, B.; Zhao, Z.; Fu, Y.; Tan, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Yin, J.; Shan, H.; Tang, B.Z.; et al. Targeted Theranostics for Tuberculosis: A Rifampicin-Loaded Aggregation-Induced Emission Carrier for Granulomas Tracking and Anti-Infection. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 8046–8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, H.; Zhao, C.; Tian, X.; Cun, D.; Yang, M. Mannose-Decorated Solid-Lipid Nanoparticles for Alveolar Macrophage Targeted Delivery of Rifampicin. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuguntaev, R.G.; Hussain, A.; Fu, C.; Chen, H.; Tao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Liang, X.-J.; Guo, W. Bioimaging guided pharmaceutical evaluations of nanomedicines for clinical translations. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, K.; Bhaskar, A.; Dwivedi, V.P. Progressive Host-Directed Strategies to Potentiate BCG Vaccination Against Tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 944183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Kumar, S.K.; Nath, A.; Kapoor, P.; Aggarwal, A.; Misra, R.; Sinha, S. Synergy between tuberculin skin test and proliferative T cell responses to PPD or cell-membrane antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for detection of latent TB infection in a high disease-burden setting. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Pan, C.; Cheng, P.; Wang, J.; Zhao, G.; Wu, X. Peptide-Based Vaccines for Tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 830497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka; Abusalah, M.A.H.; Chopra, H.; Sharma, A.; Mustafa, S.A.; Choudhary, O.P.; Sharma, M.; Dhawan, M.; Khosla, R.; Loshali, A.; et al. Nanovaccines: A game changing approach in the fight against infectious diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Misra, T.K.; Ray, D.; Majumder, T.; Bandyopadhyay, T.K.; Bhowmick, T.K. Current therapeutic delivery approaches using nanocarriers for the treatment of tuberculosis disease. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 640, 123018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Enkhtaivan, K.; Yang, J.; Niepa, T.H.R.; Choi, J. How could emerging nanomedicine-based tuberculosis treatments outperform conventional approaches? Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muvva, J.R.; Ahmed, S.; Rekha, R.S.; Kalsum, S.; Groenheit, R.; Schön, T.; Agerberth, B.; Bergman, P.; Brighenti, S. Immunomodulatory Agents Combat Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis by Improving Antimicrobial Immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-Y.; Yoo, B.-G.; Lee, Y.; Lim, J.Y.; Gu, E.J.; Jeon, J.; Byun, E.-B. Isoniazid and nicotinic hydrazide hybrids mitigate trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate-induced inflammatory responses and pulmonary granulomas via Syk/PI3K pathways: A promising host-directed therapy for tuberculosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 183, 117798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, M.; Via, L.E.; Dartois, V.; Weiner, D.M.; Zimmerman, M.; Kaya, F.; Walker, A.M.; Fleegle, J.D.; Raplee, I.D.; McNinch, C.; et al. Normalizing granuloma vasculature and matrix improves drug delivery and reduces bacterial burden in tuberculosis-infected rabbits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2321336121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, B.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Q.; Feng, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wang, W.; Su, M.; Liu, X.; Shu, B.; et al. NIR-II AIE Luminogen-Based Erythrocyte-Like Nanoparticles with Granuloma-Targeting and Self-Oxygenation Characteristics for Combined Phototherapy of Tuberculosis. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2406143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhilta, A.; Jadhav, K.; Singh, R.; Ray, E.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Verma, R.K. Breaking the Cycle: Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors as an Alternative Approach in Managing Tuberculosis Pathogenesis and Progression. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 2567–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, E.; Tscherne, D.M.; Wienholts, M.J.; Cobos-Jiménez, V.; Scholte, F.; García-Sastre, A.; Rottier, P.J.M.; de Haan, C.A.M. Dissection of the influenza a virus endocytic routes reveals macropinocytosis as an alternative entry pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miow, Q.H.; Vallejo, A.F.; Wang, Y.; Hong, J.M.; Bai, C.; Teo, F.S.; Wang, A.D.; Loh, H.R.; Tan, T.Z.; Ding, Y.; et al. Doxycycline host-directed therapy in human pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e141895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, M.; Dong, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, X. Nanoparticles target M2 macrophages to silence kallikrein-related peptidase 12 for the treatment of tuberculosis and drug-resistant tuberculosis. Acta Biomater. 2024, 188, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariq, M.; Quadir, N.; Alam, A.; Zarin, S.; Sheikh, J.A.; Sharma, N.; Samal, J.; Ahmad, U.; Kumari, I.; Hasnain, S.E.; et al. The exploitation of host autophagy and ubiquitin machinery by Mycobacterium tuberculosis in shaping immune responses and host defense during infection. Autophagy 2023, 19, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.G.; Codogno, P.; Zhang, H. Machinery, regulation and pathophysiological implications of autophagosome maturation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovermann, M.; Stefan, A.; Palazzetti, C.; Immler, F.; Piaz, F.D.; Bernardi, L.; Cimone, V.; Bellone, M.L.; Hochkoeppler, A. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase MptpA features a pH dependent activity overlapping the bacterium sensitivity to acidic conditions. Biochimie 2023, 213, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, H.; Papavinasasundaram, K.G.; Wong, D.; Hmama, Z.; Av-Gay, Y. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Virulence Is Mediated by PtpA Dephosphorylation of Human Vacuolar Protein Sorting 33B. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 3, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.; Bach, H.; Sun, J.; Hmama, Z.; Av-Gay, Y. Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase (PtpA) excludes host vacuolar-H+–ATPase to inhibit phagosome acidification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19371–19376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its secreted tyrosine phosphatases. Biochimie 2023, 212, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Yi, M.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Chen, W. Mycobacterium tuberculosis EIS gene inhibits macrophage autophagy through up-regulation of IL-10 by increasing the acetylation of histone H3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 473, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berton, S.; Chen, L.; Liang, Y.C.; Xu, Z.; Afriyie-Asante, A.; Rajabalee, N.; Yang, W.; Sun, J. A selective PPM1A inhibitor activates autophagy to restrict the survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 2022, 29, 1126–1139.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.; Ou, M.; Fu, X.; Lin, Q.; Tao, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, A.; Li, G.; Xu, Y.; et al. Berbamine promotes macrophage autophagy to clear Mycobacterium tuberculosis by regulating the ROS/Ca2+ axis. mBio 2023, 14, e0027223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, X.; Song, F.; Xue, D.; Wang, Y. Vitamin D3 promotes autophagy in THP-1 cells infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheallaigh, C.N.; Keane, J.; Lavelle, E.C.; Hope, J.C.; Harris, J. Autophagy in the immune response to tuberculosis: Clinical perspectives. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2011, 164, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.G.; Master, S.S.; Singh, S.B.; Taylor, G.A.; Colombo, M.I.; Deretic, V. Autophagy Is a Defense Mechanism Inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis Survival in Infected Macrophages. Cell 2004, 119, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Qiao, W.; Luo, Y. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Medcomm 2023, 4, e353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Jahagirdar, P.; Tripathi, D.; Devarajan, P.V.; Kulkarni, S. Macrophage targeted polymeric curcumin nanoparticles limit intracellular survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through induction of autophagy and augment anti-TB activity of isoniazid in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1233630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekale, R.B.; Maphasa, R.E.; D’sOuza, S.; Hsu, N.J.; Walters, A.; Okugbeni, N.; Kinnear, C.; Jacobs, M.; Sampson, S.L.; Meyer, M.; et al. Immunomodulatory Nanoparticles Induce Autophagy in Macrophages and Reduce Mycobacterium tuberculosis Burden in the Lungs of Mice. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, S.; Hao, P.; Wang, D.; Zhong, P.; Tian, F.; Zhang, R.; Qiao, J.; Qiu, X.; Bao, P. Zinc oxide nanoparticles have biphasic roles on Mycobacterium-induced inflammation by activating autophagy and ferroptosis mechanisms in infected macrophages. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 180, 106132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, J.; Shen, L.; Yang, E.; Shen, H.; Huang, D.; Wang, R.; Hu, C.; Jin, H.; Cai, H.; Cai, J.; et al. Macrophage-Targeted Isoniazid–Selenium Nanoparticles Promote Antimicrobial Immunity and Synergize Bactericidal Destruction of Tuberculosis Bacilli. Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 3252–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Liao, K.; Yang, E.; Yang, F.; Lin, W.; Wang, J.; Fan, S.; Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Shen, H.; et al. Macrophage targeted iron oxide nanodecoys augment innate immunological and drug killings for more effective Mycobacterium Tuberculosis clearance. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Luan, H.; Shang, Q.; Xiang, W.; Yasin, P.; Song, X. Mannosamine-Modified Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-Polyethylene Glycol Nanoparticles for the Targeted Delivery of Rifapentine and Isoniazid in Tuberculosis Therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2025, 36, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Carretero, M.; Gómez, A.B.; Lázaro, M.; Millán-Placer, A.C.; Gaglio, S.C.; Anoz-Carbonell, E.; Picó, A.; Baranyai, Z.; Jabalera, Y.; Maqueda, M.; et al. Magnetic hyperthermia drastically enhances killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by bacteriocin AS-48 grafted on biomimetic nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Fan, S.; Liao, K.; Huang, Y.; Cong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jin, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Lu, H.; et al. Engineering zinc oxide hybrid selenium nanoparticles for synergetic anti-tuberculosis treatment by combining Mycobacterium tuberculosis killings and host cell immunological inhibition. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 12, 1074533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Xia, J.; Yu, J.; Chen, D.; Huang, Y.; Yang, F.; Ruan, Y.; Xu, J.-F.; et al. Nanomaterial-mediated host directed therapy of tuberculosis by manipulating macrophage autophagy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grobler, A.; Sierra, Z.P.; Viljoen, H. Modeling nanoparticle delivery of TB drugs to granulomas. J. Theor. Biol. 2016, 388, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, L.; Yang, L.; Li, L.; Ye, Z.; Gong, W. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Immune response, biomarkers, and therapeutic intervention. Medcomm 2024, 5, e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, D.R.; Hatherill, M.; Van Der Meeren, O.; Ginsberg, A.M.; Van Brakel, E.; Salaun, B.; Scriba, T.J.; Akite, E.J.; Ayles, H.M.; Bollaerts, A.; et al. Final Analysis of a Trial of M72/AS01E Vaccine to Prevent Tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2429–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeman, H.; Al-Wassiti, H.; Fabb, S.A.; Lim, L.; Wang, T.; Britton, W.J.; Steain, M.; Pouton, C.W.; Triccas, J.A.; Counoupas, C. An LNP-mRNA vaccine modulates innate cell trafficking and promotes polyfunctional Th1 CD4+ T cell responses to enhance BCG-induced protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. eBioMedicine 2025, 113, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.-C.; Hu, Z.-D.; Fan, X.-Y. Advances in protein subunit vaccines against tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1238586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikleanthous, D.; O’hagan, D.T.; Adamo, R. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Delivery of Vaccine Adjuvants and Antigens: Toward Multicomponent Vaccines. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 2867–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Wen, Z.; Gao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y. Precision Nanovaccines for Potent Vaccination. JACS Au 2024, 4, 2792–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakova, A.; Zhelnov, P.; Sidorov, R.; Rogova, A.; Vasileva, O.; Ivanov, R.; Reshetnikov, V.; Muslimov, A. DNA and RNA vaccines against tuberculosis: A scoping review of human and animal studies. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1457327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Xing, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Du, J.; Shi, Z.; Ma, J.; et al. Enhanced immunogenicity of the tuberculosis subunit Rv0572c vaccine delivered in DMT liposome adjuvant as a BCG-booster. Tuberculosis 2022, 134, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.C.; Onnainty, R.; Marini, M.R.; Klepp, L.I.; García, E.A.; Vazquez, C.L.; Canal, A.; Granero, G.; Bigi, F. M72 Fusion Proteins in Nanocapsules Enhance BCG Efficacy Against Bovine Tuberculosis in a Mouse Model. Pathogens 2025, 14, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Mishra, A.; Periasamy, S.; Dyett, B.; Dogra, P.; Ball, A.S.; Yeo, L.Y.; White, J.F.; Wang, Z.; Cristini, V.; et al. Prospective Subunit Nanovaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection─Cubosome Lipid Nanocarriers of Cord Factor, Trehalose 6,6′ Dimycolate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 27670–27686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Dong, S.; Song, Y.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Qian, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; et al. Self-assembled ferritin tuberculosis nanovaccines targeting ESAT-6 and CFP-10 elicit potent immunogenicity in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 146101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacámara, S.; Martin, C. MTBVAC: A Tuberculosis Vaccine Candidate Advancing Towards Clinical Efficacy Trials in TB Prevention. Arch. De Bronconeumol. 2023, 59, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aspect | WHO Standard Treatment (DOTS) | BPaL Treatment (FDA Approved) | Inhalation Therapies and Nanomedicines | Scalability and Nanomedicine Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start and Usage | Since 1991, standard six-month therapy | Recently approved after NIX-TB clinical trials | Under development, focusing on local delivery strategies | Essential for transition to clinical trial production |

| Main Drugs | Rifampicin (RIF), Isoniazid (INH), Pyrazinamide (PZA), Ethambutol (EMB) | Bedaquiline, Pretomanid, Linezolid | Bedaquiline, 1,3-Benzothiazines, Clofazimine, ATRA-PLGA NPs | Microfluidics enabling continuous, scalable production. |

| Treatment Duration | 6 months (2 months with four drugs, then 4 months with two drugs) | 6 months | Variable, focused on high local efficacy | Not applicable, but improves production for in vivo testing |

| Main Challenges |

| Frequent linezolid toxicity | Maintaining aerodynamic and nanoscale size for delivery | Scalability, reproducibility, and size control |

| Advantages |

| High efficacy against resistant TB | Higher local drug concentrations, fewer systemic effects | Continuous, efficient, and controlled production |

| Disadvantages |

| Toxicity and limited use (only if others fail) | Experimental technology is still undergoing validation | Conventional methods are not scalable or reproducible |

| Key Mechanism of Action | Multi-drug combination to eliminate TB | Bedaquiline blocks ATP synthase; others have different mechanisms | Nanoparticles enhance dissolution and pulmonary penetration | Microchannels control nanoparticle formation and size |

| Examples and Studies | Worldwide use since 1991 | Positive outcomes in South African studies | Murine models, inhalable nanoparticles (BDQ, BTZ, CLZ, ATRA) | Microfluidics for ATRA-PLGA NPs |

| Side Effects | Hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity | Frequent linezolid toxicity | Expected reduction in systemic side effects via local delivery | Not directly applicable, but ensures safe production |

| WHO Recommendations | Standard treatment unless resistance is present | BPaL is recommended only if other treatments fail | Experimental approaches pending clinical validation | Technological advances for large-scale manufacturing |

| Nanotheranostic Platform | Diagnostic Function | Therapeutic Function | Example/Study | Key Features/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic nanoparticles (Au, Ag, Fe3O4) | Optical and magnetic imaging (MRI, contrast agents) | Photothermal and photodynamic therapy | Akinnawo et al. [27] | Dual-functionality: imaging-guided therapy, real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy at infection sites. |

| Macrophage-membrane-coated nanoparticles | NIR imaging of granulomas | Photothermal ablation of M. tuberculosis | Li et al. [28] | Bioinspired targeting of infected macrophages; integrates diagnosis and therapy in situ; minimizes systemic toxicity. |

| Magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4, MnFe2O4, SPIONs) | MRI-guided localization of infection | Controlled release of antitubercular drugs | Wyszogrodzka, et al. [29] Voss et al. [30] | Pulmonary accumulation visualization; external magnetic field–guided targeting; reduced systemic exposure |

| Quantum dots/upconversion nanoparticles | Optical detection of TB biomarkers | N/A (primarily diagnostic) | Nokolaev et al. [31] | Rapid and ultrasensitive detection of bacterial DNA/proteins; potential for point-of-care diagnosis |

| Polymeric/lipid-based nanocarriers | Fluorescent or radiolabeled tracking of drug distribution | Antibiotic delivery; photodynamic & immunotherapy | Tian et al. [32] Bhandari et al. [33] | Co-encapsulation of drugs and imaging agents; targeted delivery to infected macrophages; in vivo treatment monitoring |

| Metal–organic framework (MOF) nanoparticles | MRI contrast enhancement | Local drug delivery (e.g., isoniazid) | Wyszogrodzka, et al. [29] | Dual diagnostic-therapeutic functionality; magnetic guidance enables site-specific treatment |

| Strategy | Target/Mechanism | Drugs/Nanocarriers Used | Outcomes/Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granuloma Microenvironment (GME) Modulation | Targets abnormal vasculature and excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) within granulomas |

|

|

| Nanocarriers for GME-Targeting | Direct drug delivery to granulomas Overcome ECM and vascular barriers Use of phototherapy and oxygenation |

(Contains photosensitizer, Prussian blue, and perfluorocarbon; coated with erythrocyte membrane) |

|

| Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) Inhibition | Controls ECM degradation and fibrosis by targeting MMPs (MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-9) |

|

|

| RNA-based MMP Gene Silencing | Silences MMP regulatory genes (e.g., KLK12) in M2 macrophages |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onnainty, R.; Granero, G.E. Advancements in Nanotheranostic Approaches for Tuberculosis: Bridging Diagnosis, Prevention, and Therapy Through Smart Nanoparticles. J. Nanotheranostics 2025, 6, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040033

Onnainty R, Granero GE. Advancements in Nanotheranostic Approaches for Tuberculosis: Bridging Diagnosis, Prevention, and Therapy Through Smart Nanoparticles. Journal of Nanotheranostics. 2025; 6(4):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040033

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnnainty, Renée, and Gladys E. Granero. 2025. "Advancements in Nanotheranostic Approaches for Tuberculosis: Bridging Diagnosis, Prevention, and Therapy Through Smart Nanoparticles" Journal of Nanotheranostics 6, no. 4: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040033

APA StyleOnnainty, R., & Granero, G. E. (2025). Advancements in Nanotheranostic Approaches for Tuberculosis: Bridging Diagnosis, Prevention, and Therapy Through Smart Nanoparticles. Journal of Nanotheranostics, 6(4), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040033