The Applications of Nanocellulose and Its Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Relation to Obesity and Diabetes

Abstract

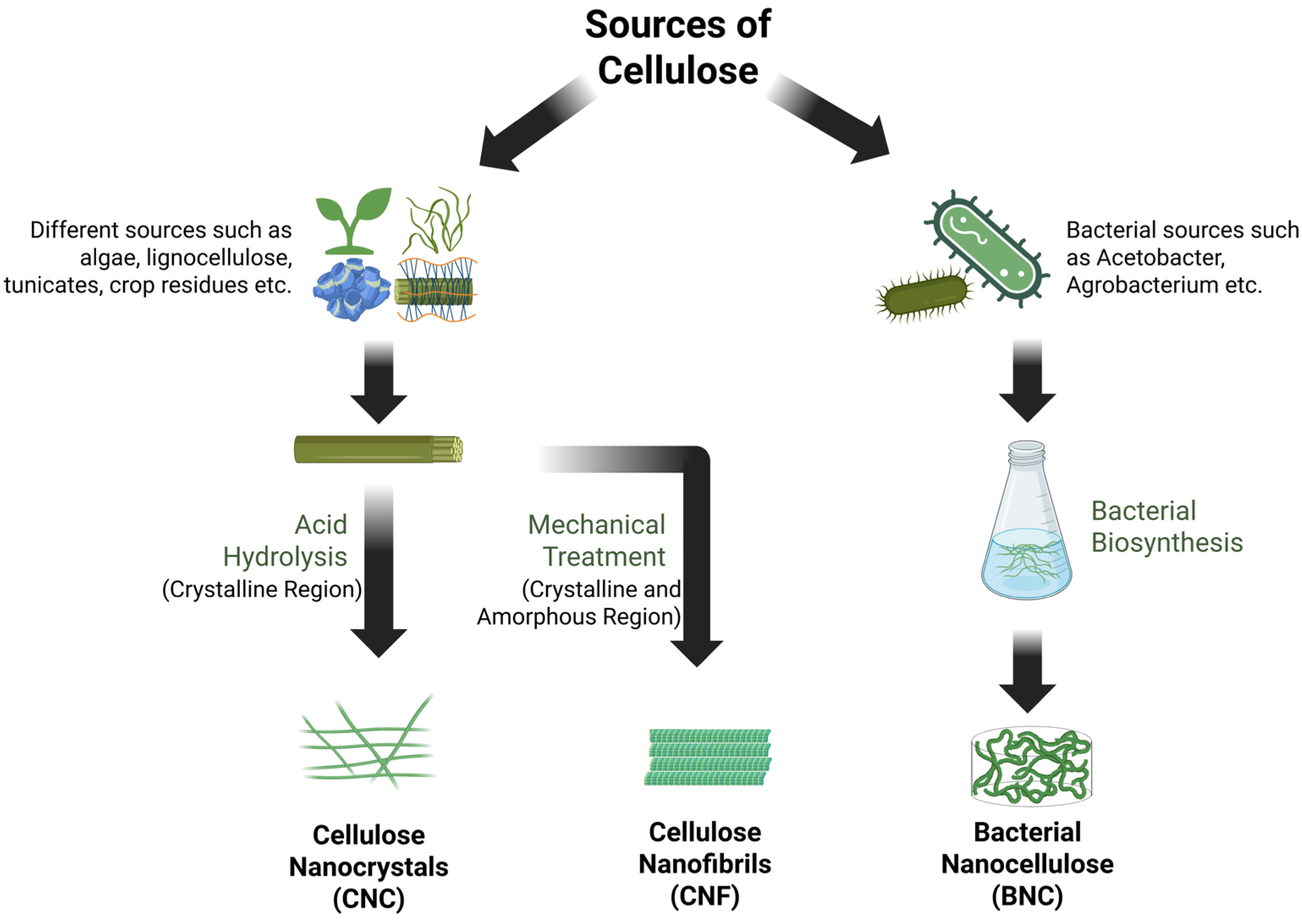

1. Introduction

2. Methods

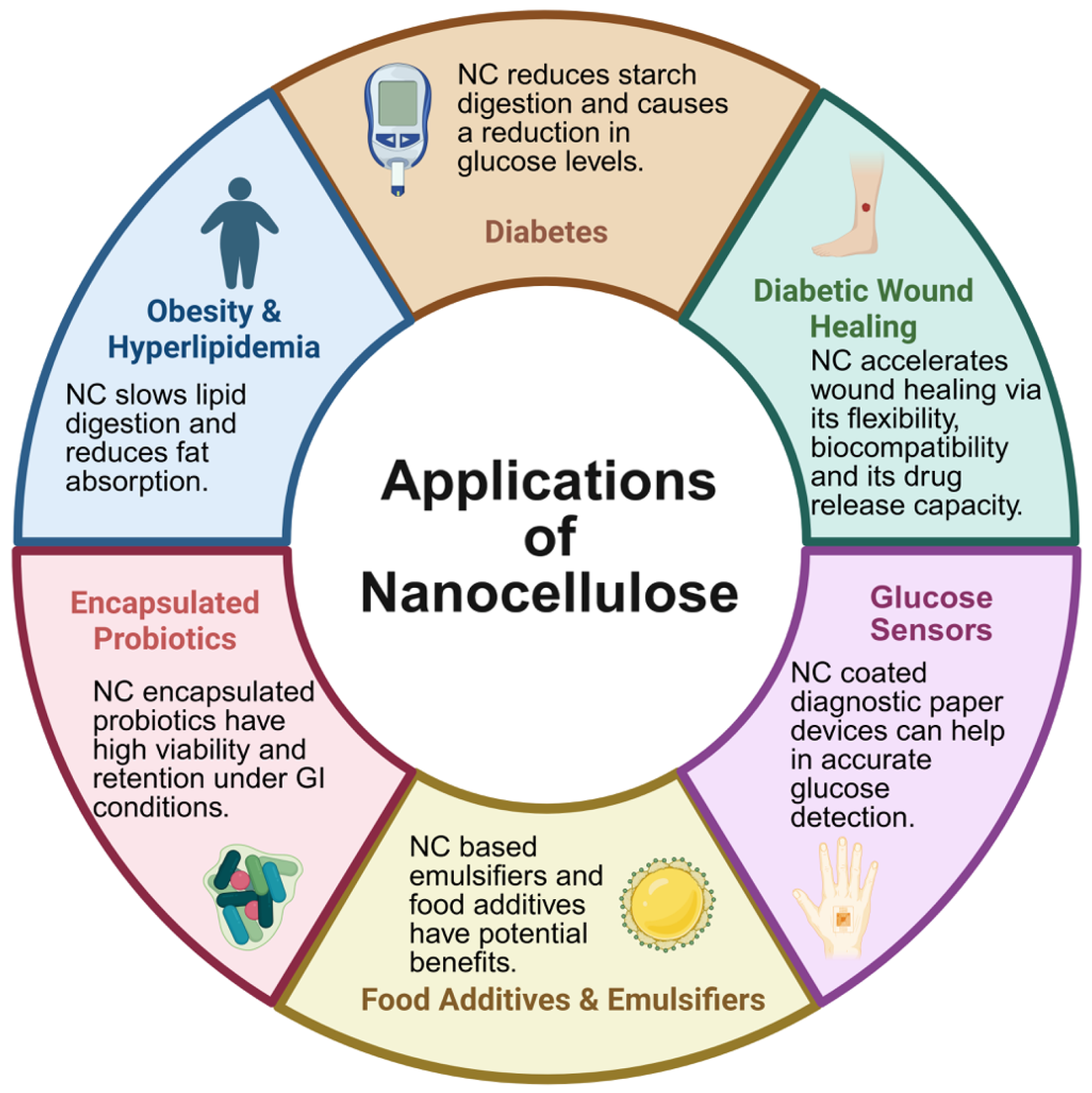

3. Applications of Nanocellulose—Focusing on Obesity and Diabetes

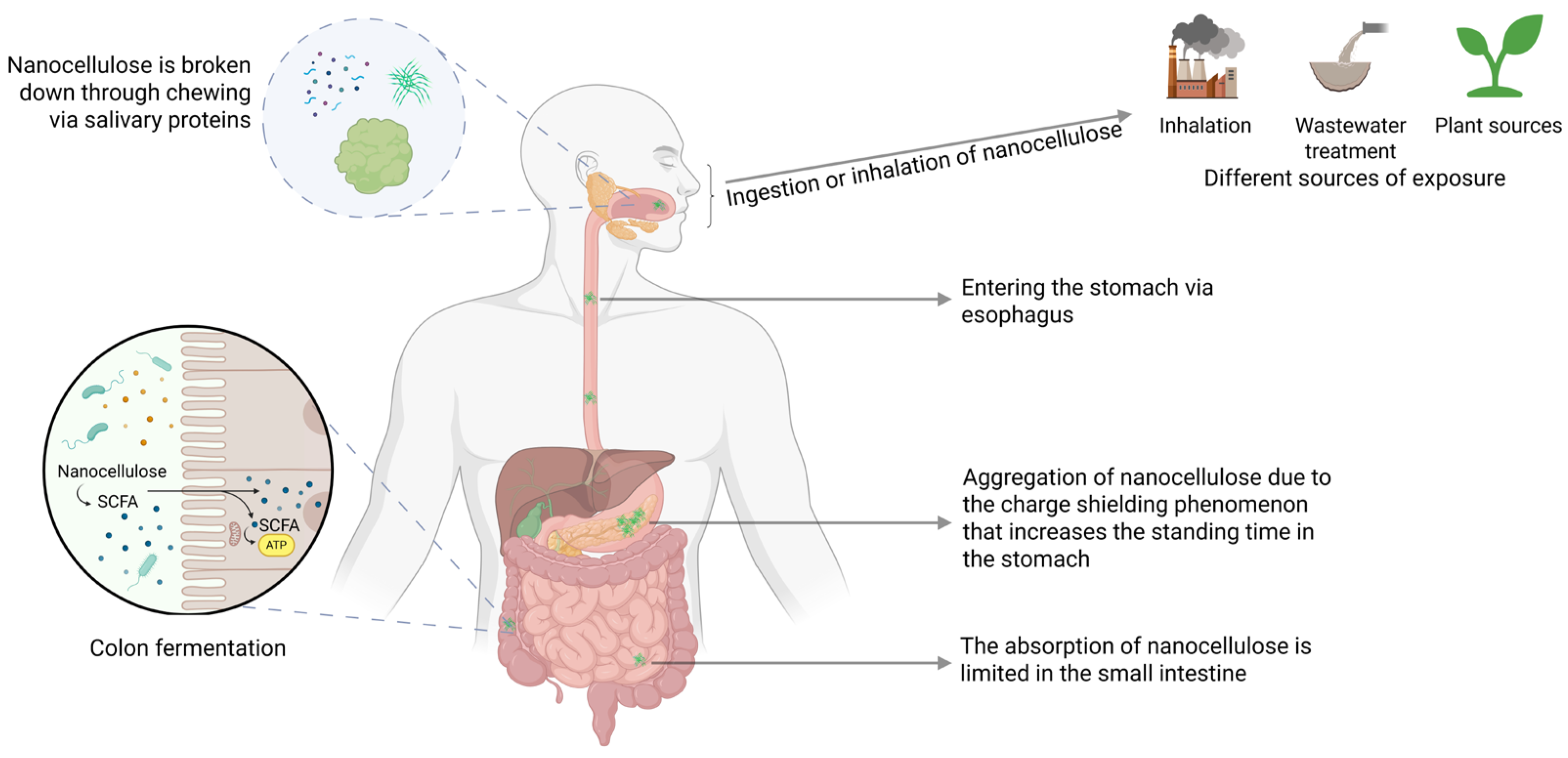

4. Uptake, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion of Nanocellulose

5. Effects of Nanocellulose on Gut Microbiota and Their Relations to Obesity and Diabetes

5.1. Effect of Cellulose Nanofibril on Gut Microbiota

5.1.1. Effect of Cellulose Nanofibril on Gut Microbiota in Males

5.1.2. Effect of Cellulose Nanofibril on Gut Microbiota in Females

5.2. Effect of Cellulose Nanocrystals on Gut Microbiota

5.3. Effect of Bacterial Nanocellulose on Gut Microbiota

5.4. Other Studies of Nanocellulose Derivatives on Gut Microbiota

6. Possible Detrimental Effects Associated with Nanocellulose-Mediated Changes in Gut Microbiota

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trache, D.; Tarchoun, A.F.; Derradji, M.; Hamidon, T.S.; Masruchin, N.; Brosse, N.; Hussin, M.H. Nanocellulose: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoid, G.M.; Sohal, I.S.; Lorente, L.R.; Molina, R.M.; Pyrgiotakis, G.; Stevanovic, A.; Zhang, R.; McClements, D.J.; Geitner, N.K.; Bousfield, D.W.; et al. Reducing Intestinal Digestion and Absorption of Fat Using a Nature-Derived Biopolymer: Interference of Triglyceride Hydrolysis by Nanocellulose. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6469–6479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefa, A.A.; Park, M.; Gwon, J.G.; Lee, B.T. Alpha tocopherol-Nanocellulose loaded alginate membranes and Pluronic hydrogels for diabetic wound healing. Mater. Des. 2022, 224, 111404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, L.; De Francesco, M.; Tedja, P.; Tanner, J.; Garnier, G. Nanocellulose coated paper diagnostic to measure glucose concentration in human blood. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1052242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, R.; Yokoyama, W.; Zhong, F. Investigation of the effect of nanocellulose on delaying the in vitro digestion of protein, lipid, and starch. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2022, 2, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas-Gutiérrez, A.; Gómez Hoyos, C.; Velásquez-Cock, J.; Gañán, P.; Triana, O.; Cogollo-Flórez, J.; Romero-Sáez, M.; Correa-Hincapié, N.; Zuluaga, R. Health and toxicological effects of nanocellulose when used as a food ingredient: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 323, 121382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, P.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Mayers, B.; Gates, B.; Yin, Y.; Kim, F.; Yan, H. One-dimensional nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and applications. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 353–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, E.J.; Moon, R.J.; Agarwal, U.P.; Bortner, M.J.; Bras, J.; Camarero-Espinosa, S.; Chan, K.J.; Clift, M.J.D.; Cranston, E.D.; Eichhorn, S.J.; et al. Current characterization methods for cellulose nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2609–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacek, P.; Dourado, F.; Gama, M.; Bielecki, S. Molecular aspects of bacterial nanocellulose biosynthesis. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.; Dufresne, A. Nanocellulose in biomedicine: Current status and future prospect. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 59, 302–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffashsaie, E.; Yousefi, H.; Nishino, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Mashkour, M.; Madhoushi, M.; Kawaguchi, H. Direct conversion of raw wood to TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 262, 117938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipelin, V.A.; Skiba, E.A.; Budaeva, V.V.; Shumakova, A.A.; Trushina, E.N.; Mustafina, O.K.; Markova, Y.M.; Riger, N.A.; Gmoshinski, I.V.; Sheveleva, S.A.; et al. Toxicological Characteristics of Bacterial Nanocellulose in an In Vivo Experiment-Part 2, Immunological Endpoints, Influence on the Intestinal Barrier and Microbiome. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLoid, G.M.; Cao, X.; Molina, R.M.; Silva, D.I.; Bhattacharya, K.; Ng, K.W.; Loo, S.C.J.; Brain, J.D.; Demokritou, P. Toxicological effects of ingested nanocellulose in in vitro intestinal epithelium and in vivo rat models. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, T.; Yano, H. Dietary cellulose nanofiber modulates obesity and gut microbiota in high-fat-fed mice. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre. 2020, 22, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.S.; Chen, Y.; Patel, A.; Wang, Z.; McDonough, C.; Guo, T.L. Chronic exposure to nanocellulose altered depression-related behaviors in mice on a western diet: The role of immune modulation and the gut microbiome. Life Sci. 2023, 335, 122259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.S.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.J.; Eldefrawy, F.; Kramer, N.E.; Siracusa, J.S.; Kong, F.; Guo, T.L. Nanocellulose dysregulated glucose homeostasis in female mice on a Western diet: The role of gut microbiome. Life Sci. 2025, 370, 123567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, J.Q. Definitions, Classification, and Epidemiology of Obesity. [Updated 2023 May 4]. In Endotext [Internet]; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279167/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Sandoval, D.A.; Patti, M.E. Glucose metabolism after bariatric surgery: Implications for T2DM remission and hypoglycaemia. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veghari, G.; Sedaghat, M.; Maghsodlo, S.; Banihashem, S.; Moharloei, P.; Angizeh, A.; Tazik, E.; Moghaddami, A.; Joshaghani, H. The association between abdominal obesity and serum cholesterol level. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2015, 5, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, K.; Pathak, M.S.; Borah, P.; Das, D. Association of Decreased High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C) With Obesity and Risk Estimates for Decreased HDL-C Attributable to Obesity: Preliminary Findings From a Hospital-Based Study in a City From Northeast India. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2017, 8, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowell, H. Definition of dietary fiber and hypotheses that it is a protective factor in certain diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1976, 29, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.W. The role of dietary carbohydrate and fiber in the control of diabetes. Adv. Intern. Med. 1980, 26, 67–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozyurt, V.H.; Ötles, S. Effect of food processing on the physicochemical properties of dietary fibre. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2016, 15, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Kerr, W.L.; Kong, F. Characterization of lipid emulsions during in vitro digestion in the presence of three types of nanocellulose. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 545, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.J.; Qin, Z.; Paton, C.M.; Fox, D.M.; Kong, F. Influence of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) on permeation through intestinal monolayer and mucus model in vitro. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 263, 117984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.J.; Nagy, T.; Kong, F.; Guo, T.L. Subchronic exposure to cellulose nanofibrils induces nutritional risk by non-specifically reducing the intestinal absorption. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H. Cellulose and the human gut. Gut 1984, 25, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, T.; Yano, H. Effect of dietary cellulose nanofiber and exercise on obesity and gut microbiota in mice fed a high-fat-diet. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittendorfer, B.; Peterson, L.R. Cardiovascular Consequences of Obesity and Targets for Treatment. Drug Discov. Today Ther. Strategies 2008, 5, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Selvin, E. Prevalence and Management of Obesity in U.S. Adults With Type 1 Diabetes. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, eL230228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kerr, W.L.; Kong, F.; Dee, D.R.; Lin, M. Influence of nano-fibrillated cellulose (NFC) on starch digestion and glucose absorption. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutnikova, H.; Genser, B.; Monteiro-Sepulveda, M.; Faurie, J.M.; Rizkalla, S.; Schrezenmeir, J.; Clément, K. Impact of bacterial probiotics on obesity, diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease related variables: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e017995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Ramasamy, M.; Cho, D.G.; Chung Soo, C.C.; Kapar, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Tam, K.M.C. A new approach for the encapsulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae using shellac and cellulose nanocrystals. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 134, 108079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, F.; Li, B.; Luo, X.; Liu, S. Probiotics in cellulose houses: Enhanced viability and targeted delivery of Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 62, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, C.; Zhou, W.; Luan, Q.; Li, W.; Deng, Q.; Dong, X.; Tang, H.; Huang, F. A pH-responsive gel microsphere based on sodium alginate and cellulose nanofiber for potential intestinal delivery of probiotics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 23, 1981–1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nahr, F.K.; Mokarram, R.R.; Hejazi, M.A.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Khiyabani, M.S.; Benis, K.Z. Optimization of the nanocellulose based cryoprotective medium to enhance the viability of freeze dried Lactobacillus plantarum using response surface methodology. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, O.; Khaledabad, M.A.; Amiri, S.; Asl, A.K.; Makouie, S. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 7469 in whey protein isolatecrystalline nanocellulose-inulin composite enhanced gastrointestinal survivability. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 126, 109224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dong, M.; Xiao, H.; Young Quek, S.; Ogawa, Y.; Ma, G.; Zhang, C. Advances in spray-dried probiotic microcapsules for targeted delivery: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 17, 11222–11238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruah, R.; Das, A.M. Application of Nanocellulose Biocomposites in Acceleration of Diabetic Wound Healing: Recent Advances and New Perspectives. In Recent Developments in Nanofibers Research; Khan, M., Chelladurai, S.J.S., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.; Fu, L.; Wang, H.; Yin, W.; He, P.; Shi, Z.; Yang, G. A novel multifunctional self-assembled nanocellulose based scaffold for the healing of diabetic wounds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 361, 123643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadi, A.; Lodeserto, P.; Todaro, F.; Meloni, M.; Romano, M.; Minasi, A.; Bellia, A.; Lauro, D. Nanomedicine in the Treatment of Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bancil, A.S.; Sandall, A.M.; Rossi, M.; Chassaing, B.; Lindsay, J.O.; Whelan, K. Food Additive Emulsifiers and Their Impact on Gut Microbiome, Permeability, and Inflammation: Mechanistic Insights in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2021, 15, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Sheng, X.; Gong, Z.; Zang, Y.Q. Lecithin promotes adipocyte differentiation and hepatic lipid accumulation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2009, 23, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, D.R.M.; Mendonca, M.H.; Helm, C.V.; Magalhaes, W.L.E.; de Muniz, G.I.B.; Kestur, S.G. Assessment of Nano Cellulose from Peach Palm Residue as Potential Food Additive: Part II: Preliminary Studies. J. Food Sci. Technol.-Mysore 2015, 52, 5641–5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khare, S.; DeLoid, G.M.; Molina, R.M.; Gokulan, K.; Couvillion, S.P.; Bloodsworth, K.J.; Eder, E.K.; Wong, A.R.; Hoyt, D.W.; Bramer, L.M.; et al. Effects of ingested nanocellulose on intestinal microbiota and homeostasis in Wistar Han rats. NanoImpact 2020, 18, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilves, M.; Vilske, S.; Aimonen, K.; Lindberg, H.K.; Pesonen, S.; Wedin, I.; Nuopponen, M.; Vanhala, E.; Højgaard, C.; Winther, J.R.; et al. Nanofibrillated cellulose causes acute pulmonary inflammation that subsides within a month. Nanotoxicology 2018, 12, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatkin, J.A.; Kim, B. Cellulose nanomaterials: Life cycle risk assessment, and environmental health and safety roadmap. Environ. Sci. Nano 2015, 2, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshani, R.; Madadlou, A. A viewpoint on the gastrointestinal fate of cellulose nanocrystals. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 71, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Wu, H.; Dong, Z.; Fan, Q.; Huang, J.; Jin, Z.; Xiao, N.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Ming, L. Recent trends in nanocellulose: Metabolism-related, gastrointestinal effects, and applications in probiotic delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 343, 122442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Gu, Q.; Li, J.; Fan, L. Modulating in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of nanocellulose-stabilized Pickering emulsions by altering cellulose lengths. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 118, 106738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, A.R.; Gourcy, S.; Rigby, N.M.; Moffat, J.G.; Capron, I.; Bajka, B.H. The fate of cellulose nanocrystal stabilised emulsions after simulated gastrointestinal digestion and exposure to intestinal mucosa. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 2991–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Juan, A.; Assié, A.; Esteve-Codina, A.; Gut, M.; Benseny-Cases, N.; Samuel, B.S.; Dalfó, E.; Laromaine, A. Caenorhabditis elegans endorse bacterial nanocellulose fibers as functional dietary Fiber reducing lipid markers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 331, 121815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsor-Atindana, J.; Zhou, Y.X.; Saqib, M.N.; Chen, M.; Douglas Goff, H.; Ma, J.; Zhong, F. Enhancing the prebiotic effect of cellulose biopolymer in the gut by physical structuring via particle size manipulation. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, K.; Deehan, E.C.; Walter, J.; Backhed, F. The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cha, R.; Hao, W.; Du, R.; Zhang, P.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, X. Nanocrystalline Cellulose Cures Constipation via Gut Microbiota Metabolism. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 16481–16496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Sun, C.; Fang, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fang, Y. In vitro colonic fermentation profiles and microbial responses of cellulose derivatives with different colloidal states. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9509–9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hwang, S.W.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Kim, T.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, S.J.; Yoo, H.J.; Kim, E.N.; Kweon, M.-N. Dietary cellulose prevents gut inflammation by modulating lipid metabolism and gut microbiota. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 944–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, S.; Yuan, G.; Li, C.; Xiong, Y.; Zhong, X.; Li, X. High cellulose dietary intake relieves asthma inflammation through the intestinal microbiome in a mouse model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornejo-Pareja, I.; Muñoz-Garach, A.; Clemente-Postigo, M.; Tinahones, F.J. Importance of gut microbiota in obesity. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 72 (Suppl. 1), 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crudele, L.; Gadaleta, R.M.; Cariello, M.; Moschetta, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches of diabetes. eBioMedicine. 2023, 97, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, W.; van Kesteren, P.C.E.; Swart, E.; Oomen, A.G. Overview of potential adverse health effects of oral exposure to nanocellulose. Nanotoxicology 2022, 16, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cha, R.; Hao, W.; Jiang, X. Nanocrystalline Cellulose Modulates Dysregulated Intestinal Barriers in Ulcerative Colitis. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 18965–18978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, H.; Gholami, A.M.; Berry, D.; Desmarchelier, C.; Hahne, H.; Loh, G.; Mondot, S.; Lepage, P.; Rothballer, M.; Walker, A.; et al. High-fat diet alters gut microbiota physiology in mice. ISME J. 2014, 8, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Yang, L.; Huang, P.; Li, W.; Wang, S.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, M.; Pang, X.; Yan, Z.; et al. Structural modulation of gut microbiota in life-long calorie-restricted mice. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, L.B.; Liu, C.M.; Melendez, J.H.; Frankel, Y.M.; Engelthaler, D.; Aziz, M.; Bowers, J.; Rattray, R.; Ravel, J.; Kingsley, C.; et al. Community analysis of chronic wound bacteria using 16S rRNA gene-based pyrosequencing: Impact of diabetes and antibiotics on chronic wound microbiota. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wu, N.; Wang, X.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Dysbiosis gut microbiota associated with inflammation and impaired mucosal immune function in intestine of humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.Y.; Ahn, Y.T.; Park, S.H.; Huh, C.S.; Yoo, S.R.; Yu, R.; Sung, M.K.; McGregor, R.A.; Choi, M.S. Supplementation of Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032 in diet-induced obese mice is associated with gut microbial changes and reduction in obesity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Derrien, M.; Rocher, E.; van-Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.; Strissel, K.; Zhao, L.; Obin, M.; et al. Modulation of gut microbiota during probiotic-mediated attenuation of metabolic syndrome in high fat diet-fed mice. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, D.K.; Renuka Puniya, M.; Shandilya, U.K.; Dhewa, T.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, S.; Puniya, A.K.; Shukla, P. Gut Microbiota Modulation and Its Relationship with Obesity Using Prebiotic Fibers and Probiotics: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Liu, S.; Miao, J.; Shen, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Gong, H.; Li, M.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Q. Eubacterium siraeum suppresses fat deposition via decreasing the tyrosine-mediated PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Microbiome 2024, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinagawa, N.; Tanaka, K.; Mikamo, H.; Watanabe, K.; Takeyama, H.; Yokoyama, T.; Takesue, Y.; Taniguchi, M. Bacteria isolated from perforation peritonitis and their antimicrobial susceptibilities. Jpn. J. Antibiot. 2007, 60, 206–220. [Google Scholar]

- Iwashita, M.; Hayashi, M.; Nishimura, Y.; Yamashita, A. The Link Between Periodontal Inflammation and Obesity. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2021, 8, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, F.; Duan, J.; Chen, F.; Cai, Y.; Luan, Q. Periodontitis induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis drives impaired glucose metabolism in mice. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 998600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S.; Hatasa, M.; Ohsugi, Y.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Liu, A.; Niimi, H.; Morita, K.; Shimohira, T.; Sasaki, N.; Maekawa, S.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Administration Induces Gestational Obesity, Alters Gene Expression in the Liver and Brown Adipose Tissue in Pregnant Mice, and Causes Underweight in Fetuses. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 11, 745117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi, N.; Al-Marzooq, F. The Relation between Periodontopathogenic Bacterial Levels and Resistin in the Saliva of Obese Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 2643079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Ryu, S.; Fukuda, S.; Hase, K.; Yang, C.S.; Lim, H.S.; Kim, M.S.; et al. Gut commensal Bacteroides acidifaciens prevents obesity and improves insulin sensitivity in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmel, J.; Ghanayem, N.; Mayouf, R.; Saleev, N.; Chaterjee, I.; Getselter, D.; Tikhonov, E.; Turjeman, S.; Shaalan, M.; Khateeb, S.; et al. Bacteroides is increased in an autism cohort and induces autism-relevant behavioral changes in mice in a sex-dependent manner. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Du, Y.; Chi, Z.; Bian, Y.; Zhao, X.; Teng, T.; Shi, B. Isobutyrate Confers Resistance to Inflammatory Bowel Disease through Host-Microbiota Interactions in Pigs. Research 2025, 8, 0673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sánchez, M.A.; Balaguer-Román, A.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.E.; Almansa-Saura, S.; García-Zafra, V.; Ferrer-Gómez, M.; Frutos, M.D.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Ruiz-Alcaraz, A.J.; Núñez-Sánchez, M.Á.; et al. Plasma short-chain fatty acid changes after bariatric surgery in patients with severe obesity. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2023, 19, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holscher, H.D. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, E.; Young, W.; Rosendale, D.; Reichert-Grimm, V.; Riedel, C.U.; Conrad, R.; Egert, M. RNA-Based Stable Isotope Probing Suggests Allobaculum spp. as Particularly Active Glucose Assimilators in a Complex Murine Microbiota Cultured In Vitro. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1829685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Lazarevic, V.; Gaïa, N.; Johansson, M.; Ståhlman, M.; Backhed, F.; Delzenne, N.M.; Schrenzel, J.; François, P.; Cani, P.D. Microbiome of prebiotic-treated mice reveals novel targets involved in host response during obesity. ISME J. 2014, 8, 2116–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gutierrez, E.; O’Mahony, A.K.; Dos Santos, R.S.; Marroquí, L.; Cotter, P.D. Gut microbial metabolic signatures in diabetes mellitus and potential preventive and therapeutic applications. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2401654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.H.; Liu, C.P. Diabetic status and the relationship of blood glucose to mortality in adults with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii complex bacteremia. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Edreira, D.; Liñares-Blanco, J.; Fernandez-Lozano, C. Identification of Prevotella, Anaerotruncus and Eubacterium Genera by Machine Learning Analysis of Metagenomic Profiles for Stratification of Patients Affected by Type I Diabetes. Proceedings 2020, 54, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, P.; Du, L.; Wu, M.; Wang, X.; Kong, C.; Huang, D.; Xie, R.; Ji, G.; et al. Multi-omic analyses of the development of obesity-related depression linked to the gut microbe Anaerotruncus colihominis and its metabolite glutamate. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 1822–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Companys, J.; Gosalbes, M.J.; Pla-Pagà, L.; Calderón-Pérez, L.; Llauradó, E.; Pedret, A.; Valls, R.M.; Jiménez-Hernández, N.; Sandoval-Ramirez, B.A.; Del Bas, J.M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Profile and Its Association with Clinical Variables and Dietary Intake in Overweight/Obese and Lean Subjects: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langille, M.G.; Zaneveld, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; McDonald, D.; Knights, D.; Reyes, J.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Vega Thurber, R.L.; Knight, R.; et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, T.; Kanoh, H.; Inamori, K.I.; Suzuki, A.; Takahashi, T.; Inokuchi, J.I. Globo-series glycosphingolipids enhance Toll-like receptor 4-mediated inflammation and play a pathophysiological role in diabetic nephropathy. Glycobiology 2019, 29, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmiguel, C.P.; Jacobs, J.; Gupta, A.; Ju, T.; Stains, J.; Coveleskie, K.; Lagishetty, V.; Balioukova, A.; Chen, Y.; Dutson, E.; et al. Surgically Induced Changes in Gut Microbiome and Hedonic Eating as Related to Weight Loss: Preliminary Findings in Obese Women Undergoing Bariatric Surgery. Psychosom. Med. 2017, 79, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, C.; Yan, Y.; Wang, F.; Mao, Y. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and its derived metabolites confer resistance to FOLFOX through METTL3. EBioMedicine 2024, 102, 105041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cai, Y.; Meng, C.; Ding, X.; Huang, J.; Luo, X.; Cao, Y.; Gao, F.; Zou, M. The role of the microbiome in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 172, 108645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.X.; Yang, C.; Zhan, G.F.; Li, S.; Hua, D.Y.; Luo, A.L.; Yuan, X.L. Whole brain radiotherapy induces cognitive dysfunction in mice: Key role of gut microbiota. Psychopharmacology 2020, 237, 2089–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, K.E.; Rhoads, D.D.; Wilson, D.A.; Highland, K.B.; Richter, S.S.; Procop, G.W. Inquilinus limosus in pulmonary disease: Case report and review of the literature. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 86, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipina, C.; Hundal, H.S. Ganglioside GM3 as a gatekeeper of obesity-associated insulin resistance: Evidence and mechanisms. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 3221–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobgen, W.; Meininger, C.J.; Jobgen, S.C.; Li, P.; Lee, M.J.; Smith, S.B.; Spencer, T.E.; Fried, S.K.; Wu, G. Dietary L-arginine supplementation reduces white fat gain and enhances skeletal muscle and brown fat masses in diet-induced obese rats. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, F.A.; Ullah, E.; Mall, R.; Iskandarani, A.; Samra, T.A.; Cyprian, F.; Parray, A.; Alkasem, M.; Abdalhakam, I.; Farooq, F.; et al. Dysregulated Metabolic Pathways in Subjects with Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S. Can the glyoxylate pathway contribute to fat-induced hepatic insulin resistance? Med. Hypotheses 2000, 54, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagneto-Gissey, L.; Bornstein, S.R.; Mingrone, G. Dicarboxylic acids counteract the metabolic effects of a Western diet by boosting energy expenditure. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e181978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzman, E.S.; Zhang, B.B.; Zhang, Y.; Bharathi, S.S.; Bons, J.; Rose, J.; Shah, S.; Solo, K.J.; Schmidt, A.V.; Richert, A.C.; et al. Dietary dicarboxylic acids provide a nonstorable alternative fat source that protects mice against obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e174186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingrone, G.; Castagneto-Gissey, L.; Macé, K. Use of dicarboxylic acids in type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Xue, Y.; Gao, W.; Li, J.; Zu, X.; Fu, D.; Bai, X.; Zuo, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, F. Bacillaceae-derived peptide antibiotics since 2000. Peptides 2018, 101, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, V.A.; Park, S.O. Molecular Mechanism for Hepatic Glycerolipid Partitioning of n-6/n-3 Fatty Acid Ratio in an Obese Animal Biomodels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, S.; Ponnalagu, S.; Osman, F.; Tay, S.L.; Wong, L.H.; Jiang, Y.R.; Leow, M.K.S.; Henry, C.J. Increased Consumption of Unsaturated Fatty Acids Improves Body Composition in a Hypercholesterolemic Chinese Population. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 869351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koropatkin, N.M.; Cameron, E.A.; Martens, E.C. How glycan metabolism shapes the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.P.; He, Q.Q.; Ouyang, H.M.; Peng, H.S.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Lv, X.F.; Zheng, Y.N.; Li, S.C.; Liu, H.L.; et al. Human Gut Microbiota Associated with Obesity in Chinese Children and Adolescents. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 7585989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, G.F. Elevated propionate and its association with neurological dysfunctions in propionic acidemia. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 18, 1499376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Ge, W. Lactococcus lactis Subsp. lactis LL-1 and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei LP-16 Influence the Gut Microbiota and Metabolites for Anti-Obesity and Hypolipidemic Effects in Mice. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, F.; van Buuringen, N.; Voermans, N.C.; Lefeber, D.J. Galactose in human metabolism, glycosylation and congenital metabolic diseases: Time for a closer look. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2021, 1865, 129898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Ao, H.; Peng, C. Gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and herbal medicines. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K. Strategies to promote abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila, an emerging probiotic in the gut, evidence from dietary intervention studies. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 33, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, N.; Zhao, L. An opportunistic pathogen isolated from the gut of an obese human causes obesity in germfree mice. ISME J. 2013, 7, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira de Gouveia, M.I.; Bernalier-Donadille, A.; Jubelin, G. Enterobacteriaceae in the Human Gut: Dynamics and Ecological Roles in Health and Disease. Biology 2024, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, M.; Celano, G.; Calabrese, F.M.; Portincasa, P.; Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M. The Controversial Role of Human Gut Lachnospiraceae. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, W.J.; Rivero Mendoza, D.; Lambert, J.M. Diet, nutrients and the microbiome. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 171, 237–263. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Wang, Q.; Han, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, N.; Huang, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhang, R.; Meng, K. In Vitro Evaluation of Probiotic Activities and Anti-Obesity Effects of Enterococcus faecalis EF-1 in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Foods 2024, 13, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Luo, J.; Yang, F.; Feng, X.; Zeng, M.; Dai, W.; Pan, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Duan, Y.; et al. Cultivated Enterococcus faecium B6 from children with obesity promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by the bioactive metabolite tyramine. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2351620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzon, O.; Cahn, A.; Gellman, Y.N.; Leibovitch, M.; Peled, S.; Elishoov, O.; Haze, A.; Olshtain-Pops, K.; Elinav, H. Enterococci in Diabetic Foot Infections: Prevalence, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; McCarty, M.F.; OKeefe, J.H. Role of dietary histidine in the prevention of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Open Heart 2018, 5, e000676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Cheng, Z.; Jiang, M.; Ma, X.; Datsomor, O.; Zhao, G.; Zhan, K. Histidine promotes the glucose synthesis through activation of the gluconeogenic pathway in bovine hepatocytes. Animals 2021, 11, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Lin, L.-Y.; Chen, J.-W.; Chang, T.-T. CXCL5 suppression recovers neovascularization and accelerates wound healing in diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, G.; Barlow, G.M.; Rashid, M.; Hosseini, A.; Cohrs, D.; Parodi, G.; Morales, W.; Weitsman, S.; Rezaie, A.; Pimentel, M.; et al. Characterization of the Small Bowel Microbiome Reveals Different Profiles in Human Subjects Who Are Overweight or Have Obesity. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ma, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, W. Ruminococcaceae_UCG-013 Promotes Obesity Resistance in Mice. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, E.; Belkova, N.; Pogodina, A.; Romanitsa, A.; Rychkova, L. ODP377 Adolescents With Obesity Breastfed Until Four Months Age Have High Abundance Of Ruminococcaceae Bacteria In Gut Microbiota. J. Endocr. Soc. 2022, 6 (Suppl. 1), A599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Cui, Y.; Jin, J.; Huang, S.; Wei, J.; Yao, M.; Zhou, D.; Mao, S. The Alterations of Gut Microbiome and Lipid Metabolism in Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Neurol. Ther. 2023, 12, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wen, B.; Zhu, K.; Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z. Antibiotics-induced perturbations in gut microbial diversity influence metabolic phenotypes in a murine model of high-fat diet-induced obesity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5269–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Wang, M.; Ajibade, A.A.; Tan, P.; Fu, C.; Chen, L.; Zhu, M.; Hao, Z.Z.; Chu, J.; Yu, X.; et al. Microbiota regulate innate immune signaling and protective immunity against cancer. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 959–974.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zhu, W.; Lin, Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; Xu, Z.; Ng, S.C. Roseburia hominis improves host metabolism in diet-induced obesity. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2467193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.L.; Ley, R.E. The human gut bacteria Christensenellaceae are widespread, heritable, and associated with health. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Huang, H.; Xu, H.; Xia, H.; Zhang, C.; Ye, D.; Bi, F. Endogenous Coriobacteriaceae enriched by a high-fat diet promotes colorectal tumorigenesis through the CPT1A-ERK axis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Huang, W.; Lin, Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; Ng, S.C. Gut microbiota in patients with obesity and metabolic disorders—A systematic review. Genes Nutr. 2022, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, X. The family Coriobacteriaceae is a potential contributor to the beneficial effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2018, 14, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Daza, M.C.; Roquim, M.; Dudonné, S.; Pilon, G.; Levy, E.; Marette, A.; Roy, D.; Desjardins, Y. Berry Polyphenols and Fibers Modulate Distinct Microbial Metabolic Functions and Gut Microbiota Enterotype-Like Clustering in Obese Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorasani, A.C.; Shojaosadati, S.A. Bacterial nanocellulose-pectin bionanocomposites as prebiotics against drying and gastrointestinal condition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 83, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.H.; Cui, X.W.; Li, Y.X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.S.; Li, M. Bacterial cellulose is a desirable biological macromolecule that can prevent obesity via modulating lipid metabolism and gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283 Pt 1, 137522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Huang, J.; Guo, X.; Xia, J.; Hu, M. Romboutsia lituseburensis JCM1404 supplementation ameliorated endothelial function via gut microbiota modulation and lipid metabolisms alterations in obese rats. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2023, 370, fnad016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Edwards, M.; Huang, Y.; Bilate, A.M.; Araujo, L.P.; Tanoue, T.; Atarashi, K.; Ladinsky, M.S.; Reiner, S.L.; Wang, H.H.; et al. Microbiota imbalance induced by dietary sugar disrupts immune-mediated protection from metabolic syndrome. Cell 2022, 185, 3501–3519.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampanelli, E.; Romp, N.; Troise, A.D.; Ananthasabesan, J.; Wu, H.; Gül, I.S.; De Pascale, S.; Scaloni, A.; Bäckhed, F.; Fogliano, V.; et al. Gut bacterium Intestinimonas butyriciproducens improves host metabolic health: Evidence from cohort and animal intervention studies. Microbiome 2025, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, W.; Jiang, H.; Liu, S.-J. The Ambiguous Correlation of Blautia with Obesity: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosomi, K.; Saito, M.; Park, J.; Murakami, H.; Shibata, N.; Ando, M.; Nagatake, T.; Konishi, K.; Ohno, H.; Tanisawa, K.; et al. Oral administration of Blautia wexlerae ameliorates obesity and type 2 diabetes via metabolic remodeling of the gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Clostridium butyricum Strain CCFM1299 Reduces Obesity via Increasing Energy Expenditure and Modulating Host Bile Acid Metabolism. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woting, A.; Pfeiffer, N.; Loh, G.; Klaus, S.; Blaut, M. Clostridium ramosum promotes high-fat diet-induced obesity in gnotobiotic mouse models. mBio 2014, 5, e01530-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, C.; Bell, R.; Klag, K.A.; Lee, S.H.; Soto, R.; Ghazaryan, A.; Buhrke, K.; Ekiz, H.A.; Ost, K.S.; Boudina, S.; et al. T cell-mediated regulation of the microbiota protects against obesity. Science 2019, 365, eaat9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, M.T.; Kenny, D.J.; Cassilly, C.D.; Vlamakis, H.; Xavier, R.J.; Clardy, J. Ruminococcus gnavus, a member of the human gut microbiome associated with Crohn’s disease, produces an inflammatory polysaccharide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12672–12677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahwan, B.; Kwan, S.; Isik, A.; van Hemert, S.; Burke, C.; Roberts, L. Gut feelings: A randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial of probiotics for depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Huang, X.; Fang, S.; Xin, W.; Huang, L.; Chen, C. Uncovering the composition of microbial community structure and metagenomics among three gut locations in pigs with distinct fatness. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, S.; Qin, L.; Jiang, H. Distinct Gut Microbiota and Arachidonic Acid Metabolism in Obesity-Prone and Obesity-Resistant Mice with a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhuang, P.; Lin, B.; Li, H.; Zheng, J.; Tang, W.; Ye, W.; Chen, X.; Zheng, M. Gut microbiota profiling in obese children from Southeastern China. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Montoro, J.I.; Martín-Núñez, G.M.; González-Jiménez, A.; Garrido-Sánchez, L.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Tinahones, F.J. Interactions between the gut microbiome and DNA methylation patterns in blood and visceral adipose tissue in subjects with different metabolic characteristics. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wang, J.; Yan, X.; Liu, C.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, Y.; Zheng, W.; et al. Butyrate and iso-butyrate: A new perspective on nutrition prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Diabetes 2024, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, G.; Chen, X.; Ruiz, J.; White, J.V.; Rossetti, L. Mechanisms of fatty acid-induced inhibition of glucose uptake. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 93, 2438–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang, M.J. Remodeling glycerophospholipids affects obesity-related insulin signaling in skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e148176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabersani, E.; Portune, K.; Campillo, I.; López-Almela, I.; la Paz, S.M.; Romaní-Pérez, M.; Benítez-Páez, A.; Sanz, Y. Bacteroides uniformis CECT 7771 alleviates inflammation within the gut-adipose tissue axis involving TLR5 signaling in obese mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, H.; Miura, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Koike, S.; Shimamoto, S.; Kobayashi, Y. In Vitro Effects of Cellulose Acetate on Fermentation Profiles, the Microbiome, and Gamma-aminobutyric Acid Production in Human Stool Cultures. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaka, T.; Moriyama, E.; Arai, S.; Date, Y.; Yagi, J.; Kikuchi, J.; Tsuneda, S. Meta-Analysis of Fecal Microbiota and Metabolites in Experimental Colitic Mice during the Inflammatory and Healing Phases. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, W.; Cui, S.; Tang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Mao, B.; Chen, W. A Comprehensive Assessment of the Safety of Blautia producta DSM 2950. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liśkiewicz, P.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Misiak, B.; Wroński, M.; Bąba-Kubiś, A.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Marlicz, W.; Bieńkowski, P.; Misera, A.; Pełka-Wysiecka, J.; et al. Analysis of gut microbiota and intestinal integrity markers of inpatients with major depressive disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enisoglu-Atalay, V.; Atasever-Arslan, B.; Yaman, B.; Cebecioglu, R.; Kul, A.; Ozilhan, S.; Ozen, F.; Catal, T. Chemical and molecular characterization of metabolites from Flavobacterium sp. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205817. [Google Scholar]

- Priyodip, P.; Balaji, S. A Preliminary Study on Probiotic Characteristics of Sporosarcina spp. for Poultry Applications. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 76, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Hosoki, H.; Kasai, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Haraguchi, A.; Shibata, S.; Nozaki, C. A Cellulose-Rich Diet Disrupts Gut Homeostasis and Leads to Anxiety through the Gut-Brain Axis. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 7, 3071–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, C.; Lan, X.; Deng, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ning, Y. Alterations of multiple peripheral inflammatory cytokine levels after repeated ketamine infusions in major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.I.; Kim, N.; Nam, R.H.; Jang, J.Y.; Kim, E.H.; Ha, S.; Kang, K.; Lee, W.; Choi, H.; Kim, Y.R.; et al. The Protective Effect of Roseburia faecis Against Repeated Water Avoidance Stress-induced Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Wister Rat Model. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 28, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Gao, M.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, X.; Sheng, M.; Cheng, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; et al. An insoluble cellulose nanofiber with robust expansion capacity protects against obesity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277 Pt 3, 134401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nanocellulose | Model/Diseases | Model/Population | Exposure Window/Period | Dose/Concentration | Routes of Administration | Diet/Medium | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNF | Obesity and related diseases | Male C57BL/6N mice | 7 weeks | 0.1–0.2 wt% | Oral via drinking water | High-fat diet (HFD) without cellulose | CNF at 0.2% increased bacterial diversity. HFD-induced increases in the relative abundances of Streptococcaceae and Rikenellaceae were reversed by CNF. Further, 0.2% CNF intake increased the abundance of Lactobacillaceae. | [14] |

| CNF | Obesity/Gut microbiota | Male C57BL/6 mice | 30 days | 30 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Western diet | CNF treatment altered the β diversity. Further, there were changes in taxonomic features and predicted functional contents, which were mostly beneficial. | [15] |

| CNF | Type 1 diabetes | Male NOD mice | 2 months | 30 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Western diet | No significant differences were found in either the α diversity or the β diversity. However, there were changes in taxonomic features and predicted functional contents. Many of these changes have been associated with beneficial health effects. | [15] |

| CNF | Type 1 diabetes | Male NOD mice | 6 months | 30 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Western diet | No significant differences were found in either the α diversity or the β diversity. However, there were some beneficial changes in taxonomic features. Further, changes in the predicted functional contents were mostly beneficial. | [15] |

| CNF | Obesity and related diseases | Male C57BL/6N mice | 7 weeks | 0.2 wt% | Oral via drinking water | HFD without cellulose | Exercise and CNF intake together increased Eubacteriaceae. | [28] |

| CNF | Gut microbiota | Male Wistar Han rats (13 wks old) | 5 weeks | 1% | Gavage (Twice per week) | PicoLab Rodent Diet 5053 | CNF ingestion altered microbial diversity and reduced the abundances of pathogenic bacteria. However, the numbers of live Bifidobacterium were also decreased. Nonetheless, CNF had few effects on the fecal metabolome. | [45] |

| Nanocellulose | Model/Diseases | Model/Population | Exposure Window/Time | Dose/Concentration | Routes of Administration | Diet/Medium | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNF | Obesity/Gut microbiota | Female C57BL/6 mice | 30 days | 30 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Western diet | The β diversity was altered. In addition, there were many beneficial changes in taxonomic features. The seemingly beneficial effects of CNF intake are supported by pathway analysis. | [16] |

| CNF | Type 1 diabetes | Female NOD mice | 2 months | 30 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Western diet | The β diversity was altered. In addition, there were changes in taxonomic features and predicted functional contents (e.g., increases in biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids). | [16] |

| CNF | Type 1 diabetes | Female NOD mice | 6 months | 30 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Western diet | The α diversity was increased. Further, the genus Enterococcus was increased, and the histidine metabolism was predicted to increase. | [16] |

| Nanocellulose | Model/Diseases | Model/Population | Exposure Window/Period | Dose/Concentration | Routes of Administration | Diet/Medium | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNC | Obesity | Female C57BL/6 mice | 30 days | 30 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Western diet | The α diversity was significantly altered. Further, there were changes in taxonomic features that were mostly beneficial. | [16] |

| Microcrystalline cellulose of nanometric size (125 nm) | Prebiotics/Gut microbiota | Male Wistar rats (5 wks old) | 14 days | 250 mg/kg | Gavage (Twice daily) | Normal (AIN-93G) diet | There were increased SCFA yields as well as Bifidobacterium counts when compared to both control and the micro scale size cellulose. | [53] |

| CNC | Constipation | Female ICR mice | 5 days | 50–150 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Standard chow | CNC at the dosage of 100 mg/kg/day could effectively restore the disordered gut microbiota mediated by constipation. Further, the contents of SCFAs were increased. | [55] |

| CNC | Ulcerative colitis | Female C57BL/6J mice | 7 days | 50–200 mg/kg | Gavage daily | Standard chow | CNC at the dosage of 200 mg/kg/day could effectively restore the disordered gut microbiota mediated by ulcerative colitis. Further, six selected beneficial bacteria, including Akkermansia, Odoribacter, Lactobacillus, Prevotellaceae_UCG-001, Anaerotruncus and Roseburia, were significantly increased. | [62] |

| Nanocellulose | Model/Diseases | Model/Population | Exposure Window/Period | Dose/Concentration | Routes of Administration | Diet/Medium | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNC | Toxicology | Male Wistar rats | 6 weeks | 1–100 mg/kg | Diet | AIN-93M | The most changes in the state of the microbiome were observed at the 10 mg/kg dose of BNC. There were increases in the number of hemolytic aerobes and Lactobacilli, simultaneously with a decrease in Enterococci. | [12] |

| BNC | Obesity | Male ICR mice (4 weeks old) | 9 weeks | 15% | Diet | Standard chow | It seemed that Romboutsia and Eubacterium were increased while Faecalibaculum was decreased following BNC consumption. | [135] |

| BNC | Obesity | Male ICR mice (4 weeks old) | 9 weeks | 15% | Diet | HFD | High-fat diet significantly decreased gut microbiota diversity, which could be reversed by consuming BNC. Decreases in Firmicutes, F/B ratio and (F + P)/B ratio, and an increased Bacteroidetes were observed following BNC consumption. | [135] |

| Nanocellulose | Model/Diseases | Model/Population | Exposure Window/Period | Dose/Concentration | Routes of Administration | Diet/Medium | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEMPO-CNF | Obesity | Female C57BL/6J mice | 30 days | 30 mg/kg | Gavage | Western diet | No significant alterations were found in either α or β diversity. However, there were many taxonomic features that were significantly affected. These changes were mostly beneficial. | [16] |

| Variable sized microcrystalline cellulose | In vitro/Prebiotics | Fecal matter from healthy donors | 24 h | 1% | Batch-culture fermentation | Fermentation medium | The production of acetate, butyrate and propionate was significantly increased by the size reduction. | [53] |

| Four types of cellulose derivatives | In vitro | Fecal matter from healthy donors | 0–36 h | 10 mg/mL | Batch-culture fermentation | Fermentation medium | TEMPO-CNF had the highest aspect ratio and produced the highest amount of total SCFAs. TEMPO-CNF and TEMPO-CNC exhibited an opposite effect on the gut microbiota composition at the phylum level. | [56] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, T.L.; Bhagat, A.; Guo, D.J. The Applications of Nanocellulose and Its Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Relation to Obesity and Diabetes. J. Nanotheranostics 2025, 6, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040034

Guo TL, Bhagat A, Guo DJ. The Applications of Nanocellulose and Its Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Relation to Obesity and Diabetes. Journal of Nanotheranostics. 2025; 6(4):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040034

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Tai L., Ayushi Bhagat, and Daniel J. Guo. 2025. "The Applications of Nanocellulose and Its Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Relation to Obesity and Diabetes" Journal of Nanotheranostics 6, no. 4: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040034

APA StyleGuo, T. L., Bhagat, A., & Guo, D. J. (2025). The Applications of Nanocellulose and Its Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Relation to Obesity and Diabetes. Journal of Nanotheranostics, 6(4), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040034