Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for Diabetic Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Nano-Delivery Systems, and Translational Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiology of Diabetic Wound Healing

3. Therapeutic Mechanism of Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Diabetic Wound Repair

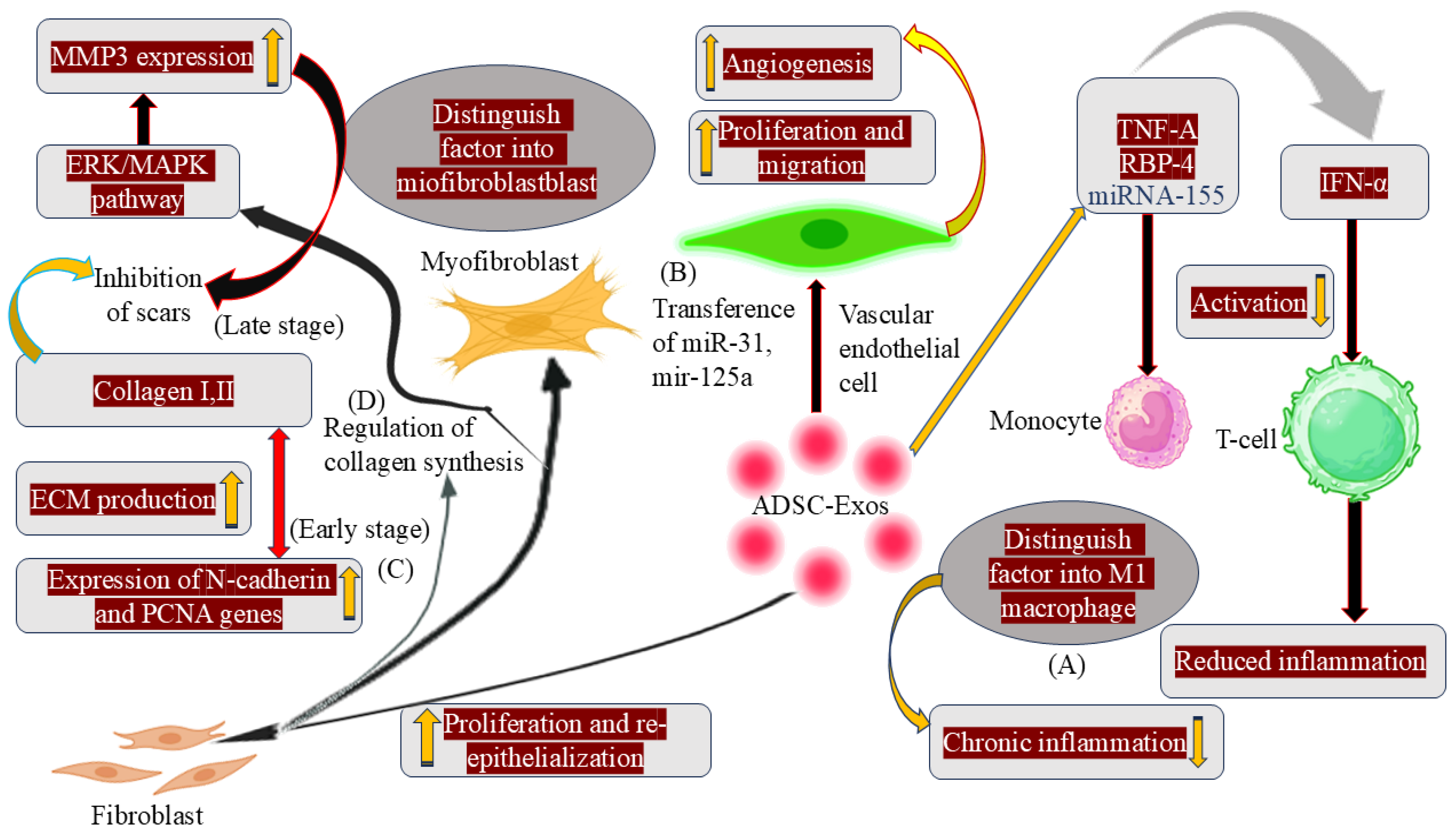

3.1. Immune Response and Anti-Inflammation

3.2. Prompting Angiogenesis

3.3. Proliferation and Re-Epithelialization of Skin Cells

3.4. Collagen Remodelling and Scar Hyperplasia

4. Biology, Biogenesis, and Composition of Exosomes

4.1. Biogenesis

4.2. Cargo

5. Engineering, Isolation, and Manufacturing of Exosomes

5.1. Ultracentrifugation (UC)

5.2. Ultrafiltration

5.3. Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

5.4. Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) and Dead-End Filtration (DEF)

5.5. Quality Control for MSC-Derived EVs

6. Classification of Exosome Isolation Methods and Their Analytical Performance

7. Characterization Techniques for Exosomes

7.1. Total Exosomes Count

7.2. Protein Content

7.3. Lipid Composition

7.4. DNA/RNA Analysis

8. Stem Cell Sources and Their Therapeutic Potential

8.1. Stem Cell Source Determination

8.2. ADSC-Exos

8.3. Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs)

8.4. Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

8.5. Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs)

8.6. iPSC-Derived Cells

8.7. Application of iPSC

9. Comparative Analysis of Stem Cell-Based Therapy and Stem Cell-Derived Exosome Therapy

10. Delivery Strategies for Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Cell Products

10.1. Direct/Topical Delivery

10.2. Exosome-Hydrogel Formulations

10.3. Three-Dimensional Scaffolds and Decellularized Matrix (dECM)-Based Delivery Systems

10.4. Microneedle-Based Transdermal Delivery Systems for Exosomes

11. Clinical Trials and Evidence on Stem Cell- and Exosome-Based Therapies

12. Key Challenges and Translational Barriers

13. Future Perspectives in Exosome-Based Diabetic Wound Healing

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| DFUs | Diabetic foot ulcers |

| MSC-Exos | Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end products |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| TNF-β | Tumor necrosis factor beta |

| FGF-2 | Fibroblast growth factor-2 |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| ADSCs | Adipose-derived stem cells |

| iPSCs | Induced pluripotent stem cells |

| PI3K/AKT | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Protein kinase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| TGF-β/Smad | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| JAK/STAT | Janus kinase/Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| IFN-α | Interferon alpha |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| RBP-4 | Retinol-binding protein 4 |

| ADSC-Exos | adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell exosomes |

| hADSCs | Human adipose stem cells |

| DLL4 | Delta-like ligand 4 |

| hADSC-Exos | Human adipose-derived stem cell exosomes |

| MMP-3 | Metalloproteinase-3 |

| TIMP-1 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 |

| ILVs | Intraluminal vesicles |

| ESCRT | endosomal sorting complex required for transport |

| Vps4 | Vascular protein sorting 4 |

| TEMs | Tetraspanins-enriched microdomains |

| MVs | Microvesicles |

| ECs | Endothelial cells |

| EM | Electron microscopy |

| RPS | Resistive pulse sensing |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| FCS | Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy |

| NTA | Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| ELISAs | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays |

| SPV | Sulfo-phospho-vanillin |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| NTV | Nanoparticle tracer vehicles |

| ASCs | Adult stem cells |

| BM-MSCs | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells |

| hUC-MSCs | Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells |

| USCs | Urine-derived stem cells |

| PD-MSCs | Placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| PLT Exos | Platelet-derived exosomes |

| EPCs | Endothelial progenitor cells |

| TNFR2 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 |

| TRAIL | Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis ligand |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| BMP | Bone morphogenetic protein |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| PECAM-1 | Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| uPA | Urokinase plasminogen activator |

| uPAR | Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor |

| uPARAP | Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor-associated |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| EGFL7 | Epidermal growth factor-like domain 7 |

| Oct4 | Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 |

| MEFs | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts |

| MN | Microneedle |

| UC | Ultracentrifugation |

| SEC | Size-exclusion chromatography |

| TFF | Tangential flow filtration |

| DEF | Dead-end filtration |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GMP | Good manufacturing practice |

| QbD | Quality by design |

| cGMP | Current good manufacturing practice |

References

- Rehman, A.; Nigam, A.; Laino, L.; Russo, D.; Todisco, C.; Esposito, G.; Svolacchia, F.; Giuzio, F.; Desiderio, V.; Ferraro, G. Mesenchymal stem cells in soft tissue regenerative medicine: A comprehensive review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutuianu, R.; Rosca, A.-M.; Iacomi, D.M.; Simionescu, M.; Titorencu, I. Human mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes promote in vitro wound healing by modulating the biological properties of skin keratinocytes and fibroblasts and stimulating angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhao, T.; Wang, C.; Sun, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Z. Cell migration in diabetic wound healing: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 56, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, Z.; Bhat, A.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, A. Elucidating diversity of exosomes: Biophysical and molecular characterization methods. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 2359–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, S.; Aly, R.; Mesilhy, R.; Aljohary, H. Diabetic foot ulcer wound healing and tissue regeneration: Signaling pathways and mechanisms. In Diabetic Foot Ulcers-Pathogenesis, Innovative Treatments and AI Applications; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Keshtkar, S.; Kaviani, M.; Sarvestani, F.S.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Aghdaei, M.H.; Al-Abdullah, I.H.; Azarpira, N. Exosomes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells preserve mouse islet survival and insulin secretion function. EXCLI J. 2020, 19, 1064. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Chen, L.-H.; Sun, S.-Y.; Li, Y.; Ran, X.-W. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: The dawn of diabetic wound healing. World J. Diabetes 2022, 13, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, H.; Pandey, M.; Lim, Y.Q.; Low, C.Y.; Lee, C.T.; Marilyn, T.C.L.; Loh, H.S.; Lim, Y.P.; Lee, C.F.; Bhattamishra, S.K. Silver nanoparticles: Advanced and promising technology in diabetic wound therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 112, 110925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Long, L.; Yang, L.; Fu, D.; Hu, C.; Kong, Q.; Wang, Y. Inflammation-responsive drug-loaded hydrogels with sequential hemostasis, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory behavior for chronically infected diabetic wound treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 33584–33599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Han, K.; Dong, K.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Long, Q.; Lu, T. Potential applications of nanomaterials and technology for diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 9717–9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, U.A.; DiPietro, L.A. Diabetes and wound angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, L.; Pan, C.; Saw, P.E.; Ren, M.; Lan, B.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, T.; Zhou, L. Naturally-occurring bacterial cellulose-hyperbranched cationic polysaccharide derivative/MMP-9 siRNA composite dressing for wound healing enhancement in diabetic rats. Acta Biomater. 2020, 102, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, M.; Dobke, M.; Lunyak, V.V. Mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue in clinical applications for dermatological indications and skin aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Chen, W.; Zhao, R.; Liu, Y. Mechanisms of Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways in diabetic wound and potential treatment strategies. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 5355–5367. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; He, W.; Mu, X.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Nie, X. Macrophage polarization in diabetic wound healing. Burn. Trauma 2022, 10, tkac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Tang, Q.; Sun, S.; Xie, H.; Wang, L.; Yin, X. Exosomes in Diabetic Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Applications, and Perspectives. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2025, 18, 2955–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.; Li, Y.; Yu, M.; Ren, D.; Han, C.; Guo, S. Advances of exosomes in diabetic wound healing. Burn. Trauma 2025, 13, tkae078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, D.; Gilligan, M.M.; Serhan, C.N.; Kashfi, K. Resolution of inflammation: An organizing principle in biology and medicine. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 227, 107879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazquez, R.; Sanchez-Margallo, F.M.; de la Rosa, O.; Dalemans, W.; Álvarez, V.; Tarazona, R.; Casado, J.G. Immunomodulatory potential of human adipose mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes on in vitro stimulated T cells. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Mei, H.; Chang, X.; Chen, F.; Zhu, Y.; Han, X. Adipocyte-derived microvesicles from obese mice induce M1 macrophage phenotype through secreted miR-155. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 8, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Lin, S.; Tan, X.; Zhu, S.; Nie, F.; Zhen, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B.; Wei, W. Exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells and application to skin wound healing. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e12993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Xiong, Z.; Zhao, J.; Yu, R.; Huang, F.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L. Exosomes derived from human adipose mensenchymal stem cells accelerates cutaneous wound healing via optimizing the characteristics of fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.W.; Seo, M.K.; Woo, E.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Park, E.J.; Kim, S. Exosomes from human adipose-derived stem cells promote proliferation and migration of skin fibroblasts. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 1170–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Knoedler, S.; Knoedler, L.; Kauke-Navarro, M.; Rinkevich, Y.; Hundeshagen, G.; Harhaus, L.; Kneser, U.; Pomahac, B.; Orgill, D.P.; Panayi, A.C. Regulatory T cells in skin regeneration and wound healing. Mil. Med. Res. 2023, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yi, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Nie, J. Effects of adipose-derived stem cell released exosomes on wound healing in diabetic mice. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi=Chin. J. Reparative Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 34, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Minciacchi, V.R.; Freeman, M.R.; Di Vizio, D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: Exosomes, microvesicles and the emerging role of large oncosomes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 40, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, Y.; Oku, M. ATG and ESCRT control multiple modes of microautophagy. FEBS Lett. 2024, 598, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltanmohammadi, F.; Gharehbaba, A.M.; Zangi, A.R.; Adibkia, K.; Javadzadeh, Y. Current knowledge of hybrid nanoplatforms composed of exosomes and organic/inorganic nanoparticles for disease treatment and cell/tissue imaging. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, W.H. Exosomes: Biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, N.; Shen, Y.-Q. Extracellular vesicles modulate key signalling pathways in refractory wound healing. Burn. Trauma 2023, 11, tkad039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Dong, Y.; Han, T.; Wang, J.; Gao, B.; Guo, H.; Xu, F.; Li, J.; Ma, Y. Microenvironmental cue-regulated exosomes as therapeutic strategies for improving chronic wound healing. NPG Asia Mater. 2022, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airola, M.V.; Hannun, Y.A. Sphingolipid metabolism and neutral sphingomyelinases. Sphingolipids Basic Sci. Drug Dev. 2013, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, T.d.C.B. Biophysical and Biological Properties of Atypical Sphingolipids: Implications to Physiology and Pathophysiology. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- van den Boorn, J.G.; Daßler, J.; Coch, C.; Schlee, M.; Hartmann, G. Exosomes as nucleic acid nanocarriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Nguyen, H.P.; Elgass, K.; Simpson, R.J.; Salamonsen, L.A. Human endometrial exosomes contain hormone-specific cargo modulating trophoblast adhesive capacity: Insights into endometrial-embryo interactions. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freger, S.; Leonardi, M.; Foster, W.G. Exosomes and their cargo are important regulators of cell function in endometriosis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2021, 43, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Huang, X.; Chang, X.; Yao, J.; He, Q.; Shen, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, K. S100-A9 protein in exosomes derived from follicular fluid promotes inflammation via activation of NF-κB pathway in polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller-Miller, S.; Trivedi, J.; Yellon, S.M.; Menon, R. Exosomes cause preterm birth in mice: Evidence for paracrine signaling in pregnancy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarovni, N.; Corrado, A.; Guazzi, P.; Zocco, D.; Lari, E.; Radano, G.; Muhhina, J.; Fondelli, C.; Gavrilova, J.; Chiesi, A. Integrated isolation and quantitative analysis of exosome shuttled proteins and nucleic acids using immunocapture approaches. Methods 2015, 87, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanichamy, K.; Vadivalagan, C.; Fan, Y.-J. Isolation and purification of exosome and other extracellular vesicles. In Extracellular Vesicles for Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Jin, K.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, L. Methods and technologies for exosome isolation and characterization. Small Methods 2018, 2, 1800021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauro, B.J.; Greening, D.W.; Mathias, R.A.; Ji, H.; Mathivanan, S.; Scott, A.M.; Simpson, R.J. Comparison of ultracentrifugation, density gradient separation, and immunoaffinity capture methods for isolating human colon cancer cell line LIM1863-derived exosomes. Methods 2012, 56, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Pei, F.; Zeng, C.; Yao, Y.; Liao, W.; Zhao, Z. Extracellular vesicles in liquid biopsies: Potential for disease diagnosis. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6611244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, W.P.; Jia, S. Extracellular Vesicles: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1660. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Kaslan, M.; Lee, S.H.; Yao, J.; Gao, Z. Progress in Exosome Isolation Techniques. Theranostics 2017, 7, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musante, L.; Tataruch-Weinert, D.; Kerjaschki, D.; Henry, M.; Meleady, P.; Holthofer, H. Residual urinary extracellular vesicles in ultracentrifugation supernatants after hydrostatic filtration dialysis enrichment. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1267896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Du, L.; Lv, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Tang, H. Emerging role and therapeutic application of exosome in hepatitis virus infection and associated diseases. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stranska, R.; Gysbrechts, L.; Wouters, J.; Vermeersch, P.; Bloch, K.; Dierickx, D.; Andrei, G.; Snoeck, R. Comparison of membrane affinity-based method with size-exclusion chromatography for isolation of exosome-like vesicles from human plasma. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Du, L. Review on strategies and technologies for exosome isolation and purification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 811971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoshenko, M.Y.; Lekchnov, E.A.; Vlassov, A.V.; Laktionov, P.P. Isolation of extracellular vesicles: General methodologies and latest trends. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8545347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryzgunova, O.E.; Zaripov, M.M.; Skvortsova, T.E.; Lekchnov, E.A.; Grigor’eva, A.E.; Zaporozhchenko, I.A.; Morozkin, E.S.; Ryabchikova, E.I.; Yurchenko, Y.B.; Voitsitskiy, V.E. Comparative study of extracellular vesicles from the urine of healthy individuals and prostate cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Guan, J.; Shi, J.; Yang, S. Proteomics of urinary exosomes for discovering novel non-invasive biomarkers of acute myocardial infarction patients. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 302, 140427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.S.; Harris, K.; Arian, K.A.; Ma, L.; Zancanela, B.S.; Church, K.A.; McAndrews, K.M.; Kalluri, R. High throughput and rapid isolation of extracellular vesicles and exosomes with purity using size exclusion liquid chromatography. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 40, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, H.; Alarcón-Zapata, P.; Nova-Lamperti, E.; Ormazabal, V.; Varas-Godoy, M.; Salomon, C.; Zuniga, F.A. Comparative study of size exclusion chromatography for isolation of small extracellular vesicle from cell-conditioned media, plasma, urine, and saliva. Front. Nanotechnol. 2023, 5, 1146772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, R.J.; Becker, M.; Wen Wen, S.; Wong, C.S.; Wiegmans, A.P.; Leimgruber, A.; Möller, A. Optimized exosome isolation protocol for cell culture supernatant and human plasma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, L.S.; Santana, M.M.; Henriques, C.; Pinto, M.M.; Ribeiro-Rodrigues, T.M.; Girão, H.; Nobre, R.J.; de Almeida, L.P. Simple and fast SEC-based protocol to isolate human plasma-derived extracellular vesicles for transcriptional research. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 18, 723–737. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Hu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, N. Immunomagnetic separation method integrated with the Strep-Tag II system for rapid enrichment and mild release of exosomes. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 3569–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tian, X.; Li, Y.; Fang, C.; Yang, F.; Dong, L.; Shen, Y.; Pu, S.; Li, J.; Chang, D. Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: A Comprehensive Review of Biomedical Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 10857–10905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busatto, S.; Vilanilam, G.; Ticer, T.; Lin, W.-L.; Dickson, D.W.; Shapiro, S.; Bergese, P.; Wolfram, J. Tangential flow filtration for highly efficient concentration of extracellular vesicles from large volumes of fluid. Cells 2018, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seet, W.T.; Mat Afandi, M.A.; Shamsuddin, S.A.; Lokanathan, Y.; Ng, M.H.; Maarof, M. Current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) Facility and production of stem cell. In Stem Cell Production: Processes, Practices and Regulations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, Y.; Ntege, E.H.; Inoue, Y.; Matsuura, N.; Sunami, H.; Sowa, Y. Optimizing mesenchymal stem cell extracellular vesicles for chronic wound healing: Bioengineering, standardization, and safety. Regen. Ther. 2024, 26, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ouyang, L.; Mi, B.; Liu, G. Engineered extracellular vesicles in wound healing: Design, paradigms, and clinical application. Small 2024, 20, 2307058. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, S.; Miura, Y. Immunomodulatory and regenerative effects of MSC-derived extracellular vesicles to treat acute GVHD. Stem Cells 2022, 40, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Santos, M.E.; Garcia-Arranz, M.; Andreu, E.J.; García-Hernández, A.M.; López-Parra, M.; Villarón, E.; Sepúlveda, P.; Fernández-Avilés, F.; García-Olmo, D.; Prosper, F. Optimization of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) manufacturing processes for a better therapeutic outcome. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 918565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wu, H.; Tan, L.; Meng, X.; Dang, W.; Han, M.; Zhen, Y.; Chen, H.; Bi, H.; An, Y. Porcine pericardial decellularized matrix bilayer patch containing adipose stem cell-derived exosomes for the treatment of diabetic wounds. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 30, 101398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, A.; Finardi, A.; Ferraro, M.M.; Manno, D.E.; Quattrini, A.; Furlan, R.; Romano, A. Selective loss of microvesicles is a major issue of the differential centrifugation isolation protocols. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupert, D.L.; Claudio, V.; Lässer, C.; Bally, M. Methods for the physical characterization and quantification of extracellular vesicles in biological samples. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 3164–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatanek, R.; Baj-Krzyworzeka, M.; Zimoch, J.; Lekka, M.; Siedlar, M.; Baran, J. The methods of choice for extracellular vesicles (EVs) characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R.J.; Zhang, Y. Understanding exosomes: Part 1—Characterization, quantification and isolation techniques. Periodontol. 2000 2024, 94, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, J.B.; Carruthers, N.J.; Stemmer, P.M. Enriching extracellular vesicles for mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2023, 42, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Skotland, T.; Berge, V.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. Exosomal proteins as prostate cancer biomarkers in urine: From mass spectrometry discovery to immunoassay-based validation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 98, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logozzi, M.; Di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Fais, S. Immunocapture-based ELISA to characterize and quantify exosomes in both cell culture supernatants and body fluids. Methods Enzymol. 2020, 645, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Hvam, M.L.; Primdahl-Bengtson, B.; Boysen, A.T.; Whitehead, B.; Dyrskjøt, L.; Ørntoft, T.F.; Howard, K.A.; Ostenfeld, M.S. Comparative analysis of discrete exosome fractions obtained by differential centrifugation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 25011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forfang, K.; Zimmermann, B.; Kosa, G.; Kohler, A.; Shapaval, V. FTIR spectroscopy for evaluation and monitoring of lipid extraction efficiency for oleaginous fungi. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmoussa, A.; Ly, S.; Shan, S.T.; Laugier, J.; Boilard, E.; Gilbert, C.; Provost, P. A subset of extracellular vesicles carries the bulk of microRNAs in commercial dairy cow’s milk. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1401897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominkuš, P.P.; Stenovec, M.; Sitar, S.; Lasič, E.; Zorec, R.; Plemenitaš, A.; Žagar, E.; Kreft, M.; Lenassi, M. PKH26 labeling of extracellular vesicles: Characterization and cellular internalization of contaminating PKH26 nanoparticles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 1350–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağcı, C.; Sever-Bahcekapili, M.; Belder, N.; Bennett, A.P.; Erdener, Ş.E.; Dalkara, T. Overview of extracellular vesicle characterization techniques and introduction to combined reflectance and fluorescence confocal microscopy to distinguish extracellular vesicle subpopulations. Neurophotonics 2022, 9, 021903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osteikoetxea, X.; Balogh, A.; Szabó-Taylor, K.; Németh, A.; Szabó, T.G.; Pálóczi, K.; Sódar, B.; Kittel, Á.; György, B.; Pállinger, É. Improved characterization of EV preparations based on protein to lipid ratio and lipid properties. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadami, S.; Dellinger, K. The lipid composition of extracellular vesicles: Applications in diagnostics and therapeutic delivery. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1198044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzenmacher, M.; Váraljai, R.; Hegedüs, B.; Cima, I.; Forster, J.; Schramm, A.; Scheffler, B.; Horn, P.A.; Klein, C.A.; Szarvas, T. Plasma next generation sequencing and droplet digital-qPCR-based quantification of circulating cell-free RNA for noninvasive early detection of cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakov, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, D.Y. Diagnostics based on nucleic acid sequence variant profiling: PCR, hybridization, and NGS approaches. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 105, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagiri, A.G.; Gotte, P.; Singireddy, S.; Kadarla, R.K. Stem cell therapy—An overview. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2019, 7, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberts, C.A.; Kwa, M.S.; Hermsen, H.P. Risk factors in the development of stem cell therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2011, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, J. The limited application of stem cells in medicine: A review. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trams, E.G.; Lauter, C.J.; Salem, N., Jr.; Heine, U. Exfoliation of membrane ecto-enzymes in the form of micro-vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1981, 645, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.T.; Johnstone, R.M. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: Selective externalization of the receptor. Cell 1983, 33, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Luo, L.; Cai, W.; Li, J.; Li, S.; et al. miR-125b-5p in adipose derived stem cells exosome alleviates pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells ferroptosis via Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 in sepsis lung injury. Redox Biol. 2023, 62, 102655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Shen, K.; Yang, X.; Hu, D.; Zheng, G.; Han, J. Exosomes Derived from Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorate Radiation-Induced Brain Injury by Activating the SIRT1 Pathway. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 693782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wen, Y.; Wu, B.; Yang, D.; Wang, G.; Xiu, G.; Ling, B.; Du, D.; et al. ADSCs increase the autophagy of chondrocytes through decreasing miR-7-5p in Osteoarthritis rats by targeting ATG4A. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 120, 110390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Q.; Yang, E.; Zhang, B.; Qian, Y.; Lian, X.; Xu, J. ADSC-Exos enhance functional recovery after spinal cord injury by inhibiting ferroptosis and promoting the survival and function of endothelial cells through the NRF2/SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 172, 116225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-S.; Ma, X.-R.; Guo, Y.-H. Development and application of haploid embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panferov, E.; Dodina, M.; Reshetnikov, V.; Ryapolova, A.; Ivanov, R.; Karabelsky, A.; Minskaia, E. Induced Pluripotent (iPSC) and Mesenchymal (MSC) Stem Cells for In Vitro Disease Modeling and Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, E.; Hadjantonakis, A.-K. Mesoderm specification and diversification: From single cells to emergent tissues. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2019, 61, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, C.R.; Djonov, V.; Volarevic, V. The cross-talk between mesenchymal stem cells and immune cells in tissue repair and regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. Function and mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells in the healing of diabetic foot wounds. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1099310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altabas, V.; Biloš, L.S.K. The role of endothelial progenitor cells in atherosclerosis and impact of anti-lipemic treatments on endothelial repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafieezadeh, D.; Rafieezadeh, A. Extracellular vesicles and their therapeutic applications: A review article (part1). Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2024, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelgawad, M.E.; Desterke, C.; Uzan, G.; Naserian, S. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling and characterization of endothelial progenitor cells: New approach for finding novel markers. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Inoue, H.; Wu, J.C.; Yamanaka, S. Induced pluripotent stem cell technology: A decade of progress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccarelli, L.; Verriello, L.; Pauletto, G.; Valente, M.; Spadea, L.; Salati, C.; Zeppieri, M.; Ius, T. The role of human pluripotent stem cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: From biological mechanism to practical implications. Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.K. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: The Story of Genetic Reprogramming. In Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies for Autoimmune Diseases; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Dong, J.; Fan, X.; Yong, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lv, L.; Wen, L.; Qiao, J. Characterization of mesenchymal stem cells in human fetal bone marrow by single-cell transcriptomic and functional analysis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Min, Z.; Alsolami, S.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, E.; Chen, W.; Zhong, K.; Pei, W.; Kang, X.; Zhang, P. Generation of human blastocyst-like structures from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Induced pluripotent stem cells, new tools for drug discovery and new hope for stem cell therapies. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 2, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitos, I.A.; Ballini, A.; Cantore, S.; Boccellino, M.; Di Domenico, M.; Borsani, E.; Nocini, R.; Di Cosola, M.; Santacroce, L.; Bottalico, L. Stem cells: A historical review about biological, religious, and ethical issues. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 9978837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, Y.Y.; Han, J.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, H.; Ku, S.-Y. Advancements in human embryonic stem cell research: Clinical applications and ethical issues. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2024, 21, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerneckis, J.; Cai, H.; Shi, Y. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs): Molecular mechanisms of induction and applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, A.; Fang, Y.; Ma, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, B. Engineering strategies to enhance the research progress of mesenchymal stem cells in wound healing. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Shahzad, K.A.; Wang, Y.; Tan, F. Signaling pathways activated and regulated by stem cell-derived exosome therapy. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankrum, J.A.; Ong, J.F.; Karp, J.M. Mesenchymal stem cells: Immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.Y.; Zhai, Y.; Li, C.T.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Chen, H.; Tse, H.F.; Lian, Q. Translating mesenchymal stem cell and their exosome research into GMP compliant advanced therapy products: Promises, problems and prospects. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 919–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Hu, Z.; Wu, S.; Yuan, Q.; Meng, S.; Li, D.; Jiang, M.; Liao, Y.; et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote wound healing and skin regeneration via the regulation of inflammation and angiogenesis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1641709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, X.-L.; Lu, Y.-j.; Lu, S.-T.; Cheng, J.; Fu, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, N.-Y.; Li, P.-X.; et al. Combined topical and systemic administration with human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hADSC) and hADSC-derived exosomes markedly promoted cutaneous wound healing and regeneration. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.K.; Won, S.-Y.; Jung, E.; Han, S.S. Recent progress in biopolymer-based electrospun nanofibers and their potential biomedical applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 293, 139426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Pan, C.; Xu, P.; Liu, K. Hydrogel-mediated extracellular vesicles for enhanced wound healing: The latest progress, and their prospects for 3D bioprinting. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, V.G.; Burdick, J.A. Chemically modified biopolymers for the formation of biomedical hydrogels. Chem. Rev. 2020, 121, 10908–10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Guo, S.; Tian, J.; Xie, X.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. Biomaterials-mediated sequential drug delivery: Emerging trends for wound healing. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 20, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Tao, S.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, C.; Xu, N. Chitosan hydrogel dressing loaded with adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promotes skin full-thickness wound repair. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.B.; Xu, Z.; Yu, C.; Jiang, Z. Hydrogel loaded with exosomes from Wharton’s Jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells enhances wound healing in mice. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2023, 52, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, D.; Yun, H.L.; Zhang, W.; Ren, L.; Li, W.W.; Han, C. Effect of adipose-derived stem cells exosomes cross-linked chitosan-αβ-glycerophosphate thermosensitive hydrogel on deep burn wounds. World J. Stem Cells 2025, 17, 102091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, B.; Liu, Q.; Mao, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Dissolvable microneedle-based wound dressing transdermally and continuously delivers anti-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic exosomes for diabetic wound treatment. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 42, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, S.; Liu, Q.; Yuen, H.-Y.; Xie, H.; Yang, Y.; Yeung, K.W.-K.; Tang, C.-Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, B. A differential-targeting core–shell microneedle patch with coordinated and prolonged release of mangiferin and MSC-derived exosomes for scarless skin regeneration. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 2667–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stem Cell and Cancer Institute, Kalbe Farma Tbk. Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cell Conditioned Medium on Chronic Ulcer Wounds: Pilot Study in Human. 2019. Available online: https://ctv.veeva.com/study/therapeutic-potential-of-stem-cell-conditioned-medium-on-chronic-ulcer-wounds (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Hafez, A. Efficacy and Safety of Wharton’s Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Randomized Controlled Trial; National Library of Medicene: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06812637 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Professional Education and Research Institute. A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Evaluating the Efficacy of a Borate-Based Bioactive Glass Advanced Wound Matrix and Standard of Care Versus Standard of Care Alone. 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06403605 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Gupta, D.; Zickler, A.M.; El Andaloussi, S. Dosing extracellular vesicles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 178, 113961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Wang, X.; Guo, M.; Tzeng, C.-M. Current development of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Cell Transplant. 2025, 34, 09636897241297623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Time (h) | Category | Main Advantages | Limitations | Suitable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Ultracentrifugation | >4 | Physical | Widely used, maintains vesicle morphology and scalable for large volume | Expensive equipment; low purity; aggregation of vesicles; time-consuming | Biomarker discovery, drug delivery research, proteomics, EV morphology studies |

| Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation | 6–12 | Physical | Highest purity among centrifugation methods; preserves size and density distribution | Very long process; requires technical expertise; low throughput | High-purity exosome isolation for molecular characterization |

| Ultrafiltration | 1–4 | Physical | Fast; no specialized equipment; high recovery of proteins/RNA | Membrane clogging; vesicle deformation due to shear stress | Biomarker analysis; RNA profiling; rapid sample concentration |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography | 0.3–2 | Physiochemical | High purity; gentle on vesicles; preserves biological activity | Requires commercial columns; moderate processing time | Drug delivery research; therapeutic exosome preparation; proteomic studies |

| Polymer-Based Precipitation (e.g., PEG) | 2–18 | Physicochemical | Simple; no specialized equipment; high yield | Co-precipitation of contaminants; pellet contains proteins/lipids; vesicle aggregation | Preliminary isolation; nucleic acid quantification; high-yield experiments |

| Microfluidic-Based Isolation | <1 | Microfluidic | Rapid; minimal sample volume; high precision; integrates isolation + analysis | Requires specialized chips; limited scalability for therapeutic use | Clinical diagnostics; point-of-care testing; single-vesicle studies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chowdhury, S.; Kumar, A.; Patel, P.; Kurmi, B.D.; Jain, S.; Kumar, B.; Vaidya, A. Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for Diabetic Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Nano-Delivery Systems, and Translational Perspectives. J. Nanotheranostics 2026, 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt7010001

Chowdhury S, Kumar A, Patel P, Kurmi BD, Jain S, Kumar B, Vaidya A. Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for Diabetic Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Nano-Delivery Systems, and Translational Perspectives. Journal of Nanotheranostics. 2026; 7(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt7010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleChowdhury, Sumsuddin, Aman Kumar, Preeti Patel, Balak Das Kurmi, Shweta Jain, Banty Kumar, and Ankur Vaidya. 2026. "Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for Diabetic Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Nano-Delivery Systems, and Translational Perspectives" Journal of Nanotheranostics 7, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt7010001

APA StyleChowdhury, S., Kumar, A., Patel, P., Kurmi, B. D., Jain, S., Kumar, B., & Vaidya, A. (2026). Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for Diabetic Wound Healing: Mechanisms, Nano-Delivery Systems, and Translational Perspectives. Journal of Nanotheranostics, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt7010001