Application of Metal-Doped Nanomaterials in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Properties and Applications of Metal-Doped Nanomaterials

2.1. Manganese-Doped Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (Mn-SMSNs)

2.2. Terbium-Doped Gadolinium Tungstate Nanoscintillators (GWOT NPs)

2.3. Bimetallic Systems

| Bimetallic Systems | Metal Combination | Key Mechanisms of Action | Key Performance Indicators | Clinical Feasibility Analysis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual-Targeting Nanozyme | Not Specified (Likely contains Fe/Mn/Ce) | 1. Dual-targeted precise delivery 2. NIR-enhanced Ferroptosis/Apoptosis 3. Synergistic cell death 4. GSH depletion | 1. High targeting specificity (>3 × non-targeted systems) 2. Significant tumor growth inhibition in xenograft models 3. Induces mitochondrial dysfunction | Moderate to High. The active targeting strategy may reduce off-target effects. NIR light is clinically applicable, but tissue penetration depth can be a limiting factor. | [58,59,60] |

| Dendrimer-Entrapped Nanozyme | Pt-Cu | 1. TME regulation (pH, O2, H2O2) 2. Cascade catalytic therapy (CDT) 3. Regulable activity | 1. Multi-enzyme-like activities (POD, CAT, SOD) 2. Synergistic enhancement of CDT and PTT 3. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis | Moderate. The use of precious metals (Pt) may increase cost. The sophisticated design for TME regulation is promising but requires validation of large-scale manufacturing and long-term safety. | [61,62] |

| Mitochondria-Targeted Nanozyme | Fe-Cu | 1. Mitochondria-specific targeting 2. Synergistic induction of Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis 3. Ion-interference therapy (IIT) 4. ROS generation under NIR | 1. Efficient tumor accumulation 2. Disruption of mitochondrial function 3. Validated anti-tumor efficacy in vivo | Promising, but early stage. Leveraging essential metal ions (Fe, Cu) could improve biocompatibility. The novel mechanism of cuproptosis induction is significant, but its long-term metabolic profile needs thorough investigation. | [63] |

| Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) Nanoplatform | Mg/Fe/Zn/Al | 1. Immunotherapy via TME modulation (Ca2+ chelation) 2. Reduces tumor stiffness 3. Promotes immune cell infiltration 4. Inhibits metastasis | 1. Targets advanced, large-volume tumors 2. Activates anti-tumor immune response | High. Metal ions are biocompatible. The material’s ability to modulate the immunosuppressive TME is highly relevant for treating advanced cancers. Likely favorable safety profile supports clinical translation. | [64,65,66] |

| Heterometallic Iron Complexes | Fe with Pt, Pd, Au, Ru, etc. | 1. ROS generation 2. Apoptosis induction 3. Cell cycle arrest 4. Theranostic capabilities (e.g., MRI) | 1. Activity against Pt-resistant cancers 2. Multiple mechanisms of action | Variable. These are typically small molecules, not nanoparticles. Their development is at an earlier stage. Clinical feasibility will depend heavily on the specific metal pair and its pharmacokinetic and toxicity profile. | [67,68] |

| Au/Ag Nanoparticles | Au-Ag | 1. Multiple synergistic therapy (PTT, PDT) 2. Drug delivery 3. Gene expression modulation | 1. Effective in PTT/PDT 2. Capable of targeted drug delivery | High. Gold and silver nanostructures are well-studied with tunable properties. Their application in thermally based therapies is clinically feasible, though concerns about long-term biodistribution of silver may need addressing. | [56,57,69] |

2.4. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

| MOFs | Metal Nodes and Organic Ligands | Key Mechanisms of Action | Key Performance Indicators | Clinical Feasibility Analysis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) MOFs | Zn2+ with 2-methylimidazole | 1. Drug carrier 2. PTT 3. CDT by Zn2+ | 1. Drug loading capacity up to 20–30 wt%. 2. Temperature increase at the tumor site up to 30–40 °C under NIR irradiation. 3. In vitro cell experiments show tumor cell inhibition rates of 70–90%. | Moderate: Good biocompatibility, but Zn2+ may dissolve under certain conditions, requiring assessment of potential toxicity to normal tissues. Large-scale production and purification processes need optimization, and costs are relatively high. | [84,85,86] |

| UiO-66 MOFs | Zr4+ with terephthalic acid | 1. Radiotherapy sensitization 2. Fluorescence imaging 3. Combination Therapy | 1. Radiotherapy sensitization ratio of 1.5–2.0. 2. Fluorescence quantum yield of approximately 1–5%. 3. In animal experiments, tumor growth inhibition rate increased by 30–50% compared to radiotherapy alone. | Moderate. Zr4+ has good biostability, but degradation products of organic ligands may be toxic. The size and dispersibility of MOFs affect their distribution and metabolism in the body, requiring further optimization. | [87,88,89] |

| MIL-100(Fe) MOFs | Fe3+ with 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid | 1. CDT by Fe3+ 2. MRI Contrast | 1. Increased ·OH generation rate in the acidic tumor microenvironment. 2. Transverse relaxation rate (r2) of approximately 10–20 mM−1 s−1. 3. In vivo experiments clearly show tumor sites, providing accurate positioning for treatment. | Moderate. Fe3+ is an essential element with relatively good biocompatibility. However, MRI effects are significantly influenced by MOFs size and concentration, and iron overload may occur during treatment. | [90,91,92] |

| PCN-224 MOFs | Zr4+ with terephthalic acid and porphyrin | 1. PDT by porphyrin under light irradiation 2. Fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging | 1. Singlet oxygen quantum yield of approximately 0.5–0.7. 2. Fluorescence lifetime of approximately 10–20 ns. 3. High signal-to-noise ratio in photoacoustic imaging, accurately displaying tumor boundaries and size. | Moderate. Porphyrin ligands have certain photostability, but their metabolic processes in the body are complex. Photosensitivity of PCN-224 may cause photodamage to normal tissues, requiring precise control of light irradiation parameters. | [75,93,94] |

| HKUST-1 MOFs | Cu2+ with 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid | 1. CDT by Cu2+ 2. Immunotherapy | 1. Significant increase in ·OH and ·O2− generation in tumor tissues. 2. In vitro experiments promote polarization of TAMs from M2 to M1 type, enhancing antitumor immune responses. | Low to Moderate. Cu2+ has certain toxicity and may cause damage to organs such as the liver and kidneys. The stability and biodegradability of HKUST-1 need further research to ensure safety in the body. | [95,96,97] |

3. Synergistic Therapeutic Mechanisms and Applications

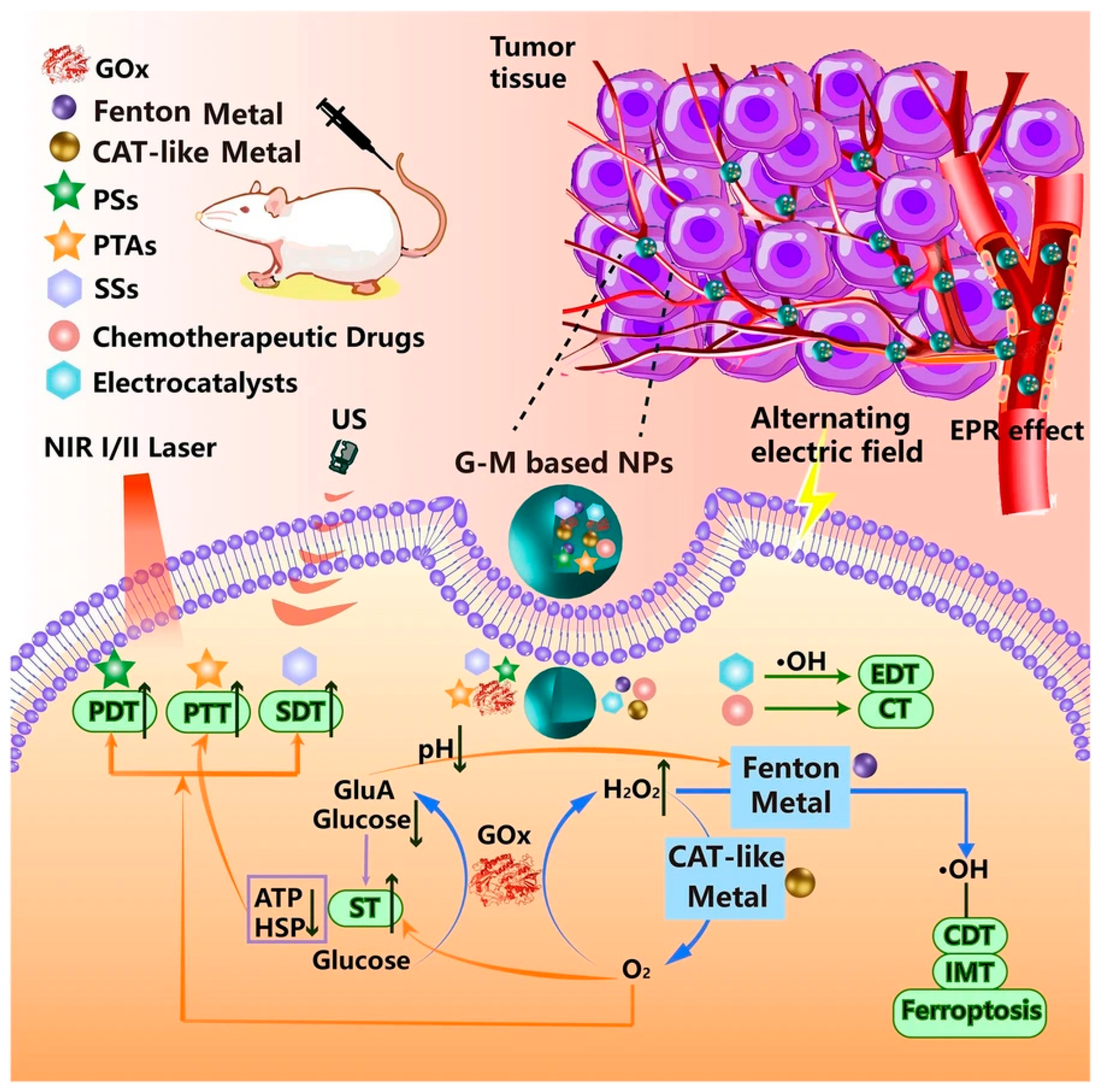

3.1. Chemodynamic Therapy

3.2. Photothermal Therapy and Photodynamic Therapy

3.3. Synergistic Therapeutic Strategies

4. Conclusions and Outlooks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2023 Cancer Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of cancer, 1990–2023, with forecasts to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1565–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.; Khatoon, S.; Khan, M.J.; Abu, J.; Naeem, A. Advancements and limitations in traditional anti-cancer therapies: A comprehensive review of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Suliman, H.; Alamzeb, M.; Abid, O.U.; Sohail, M.; Ullah, M.; Haleem, A.; Omer, M. An insight into recent developments of copper, silver and gold carbon dots: Cancer diagnostics and treatment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1292641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, Y.; Mao, J. Transition metal supported UiO-67 materials and their applications in catalysis. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1596868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Luo, Z.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Xia, C. Mechanism and application of copper-based nanomedicines in activating tumor immunity through oxidative stress modulation. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1646890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarif, Z.H.; Oresegun, A.; Abubakar, A.; Basaif, A.; Zin, H.M.; Choo, K.Y.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Abdul-Rashid, H.A.; Bradley, D.A. Time-Resolved Radioluminescence Dosimetry Applications and the Influence of Ge Dopants In Silica Optical Fiber Scintillators. Quantum Beam Sci. 2022, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zeng, X.; Mei, L. An optimal portfolio of photothermal combined immunotherapy. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, J.; Bezuidenhout, C.X.; Villa, I.; Cova, F.; Crapanzano, R.; Frank, I.; Pagano, F.; Kratochwill, N.; Auffray, E.; Bracco, S.; et al. Highly luminescent scintillating hetero-ligand MOF nanocrystals with engineered Stokes shift for photonic applications. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zou, Y.; Hu, L.; Lv, Y. Manganese-doped liquid metal nanoplatforms for cellular uptake and glutathione depletion-enhanced photothermal and chemodynamic combination tumor therapy. Acta Biomater. 2025, 191, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Tang, Z.; Tian, S.; Tang, H.; Jia, Z.; Li, F.; Qiu, C.; Deng, L.; Ke, L.; He, P.; et al. Metal-organic nanostructures based on sono/chemo-nanodynamic synergy of TixOy/Ru reaction units: For ultrasound-induced dynamic cancer therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadzadeh, M.; Khosravi, A.; Zarepour, A.; Jamalipour Soufi, G.; Hekmatnia, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Iravani, S. Molecular imaging using (nano)probes: Cutting-edge developments and clinical challenges in diagnostics. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 24696–24725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, P.; Nuzzo, S.; Torino, E.; Condorelli, G.; Salvatore, M.; Grimaldi, A.M. Antifouling Strategies of Nanoparticles for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Application: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Liang, Y.; Cai, W.; Chakravarty, R. In situ radiochemical doping of functionalized inorganic nanoplatforms for theranostic applications: A paradigm shift in nanooncology. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Sun, L.; Wu, M.; Li, Q. From detection to elimination: Iron-based nanomaterials driving tumor imaging and advanced therapies. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1536779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Simms, M.E.; Kertesz, V.; Wilson, J.J.; Thiele, N.A. Chelating Rare-Earth Metals Ln3+ and 225Ac3+ with the Dual-Size-Selective Macrocyclic Ligand Py2-Macrodipa. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 12847–12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-J.; Liu, J.-H.; Liu, W.; Niu, R.; Zhang, B.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.-H.; Zhang, H.-J. Metal-based nanomedicines for cancer theranostics. Mil. Med. Res. 2025, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Quan, G.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Niu, B.; Wu, B.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarn, D.; Ashley, C.E.; Xue, M.; Carnes, E.C.; Zink, J.I.; Brinker, C.J. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle nanocarriers: Biofunctionality and biocompatibility. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Xie, W.; Luo, X.; Zou, G.; Mo, Q.; Zhong, W. Manganese-doped stellate mesoporous silica nanoparticles: A bifunctional nanoplatform for enhanced chemodynamic therapy and tumor imaging. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 370, 113012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Kang, J.; Wang, L.; Huang, D.; Liu, Y.; He, C.; Lin, C.; Lu, C.; Wu, D.; et al. Mesoporous manganese nanocarrier target delivery metformin for the co-activation STING pathway to overcome immunotherapy resistance. iScience 2024, 27, 110150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, E.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Liao, Z. Tumor microenvironment responsive Mn-based nanoplatform activate cGAS-STING pathway combined with metabolic interference for enhanced anti-tumor therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zou, K.; Lan, Z.; Cheng, G.; Mai, Q.; Cui, H.; Meng, Q.; Chen, T.; Rao, L.; et al. Biomimetic manganese-based theranostic nanoplatform for cancer multimodal imaging and twofold immunotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 19, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Li, Q.; Li, G.; Wang, T.; Lv, X.; Pei, Z.; Gao, X.; Yang, N.; Gong, F.; Yang, Y.; et al. Manganese molybdate nanodots with dual amplification of STING activation for “cycle” treatment of metalloimmunotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 31, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, B.; Liu, X.; Gu, J.; Yang, T.; Sun, C.; Yi, X. Differential reinforcement of cGAS-STING pathway-involved immunotherapy by biomineralized bacterial outer membrane-sensitized EBRT and RNT. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Mao, Y.; Feng, S.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S. Biomimetic smart mesoporous carbon nanozyme as a dual-GSH depletion agent and O2 generator for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Acta Biomater. 2022, 148, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; He, Y.; Lu, J.; Yan, Z.; Song, L.; Mao, Y.; Di, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S. Degradable iron-rich mesoporous dopamine as a dual-glutathione depletion nanoplatform for photothermal-enhanced ferroptosis and chemodynamic therapy. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2023, 639, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, E.M.; Koretsky, A.P. Convertible manganese contrast for molecular and cellular MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2008, 60, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaad, C.A.; Pautler, R.G. Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI). Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 711, 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Feng, X.; Sun, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S. Mesoporous carbon—Manganese nanocomposite for multiple imaging guided oxygen-elevated synergetic therapy. J. Control Release 2020, 319, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkaew, A.; Chen, F.; Zhan, Y.; Majewski, R.L.; Cai, W. Scintillating Nanoparticles as Energy Mediators for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3918–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewnuam, E.; Wantana, N.; Ruangtaweep, Y.; Cadatal-Raduban, M.; Yamanoi, K.; Kim, H.J.; Kidkhunthod, P.; Kaewkhao, J. The influence of CeF3 on radiation hardness and luminescence properties of Gd2O3-B2O3 glass scintillator. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, X.; Liu, X.; Mao, R.; Chen, X.; Li, W. Codoping Enhanced Radioluminescence of Nanoscintillators for X-ray-Activated Synergistic Cancer Therapy and Prognosis Using Metabolomics. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 10419–10433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, W.; Yang, K.; Mao, R.; Ahmad, F.; Chen, X.; Li, W. CT/MRI-Guided Synergistic Radiotherapy and X-ray Inducible Photodynamic Therapy Using Tb-Doped Gd-W-Nanoscintillators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 2017–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polozhentsev, O.E.; Pankin, I.A.; Khodakova, D.V.; Medvedev, P.V.; Goncharova, A.S.; Maksimov, A.Y.; Kit, O.I.; Soldatov, A.V. Synthesis, Characterization and Biodistribution of GdF3:Tb3+@RB Nanocomposites. Materials 2022, 15, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.D.; Nguyen, H.T.; Chen, H.; Cox, P.B.; Wang, L.; Nagata, K.; Hao, Z.; Wang, A.; Li, Z.; Xie, J. X-Ray Induced Photodynamic Therapy: A Combination of Radiotherapy and Photodynamic Therapy. Theranostics 2016, 6, 2295–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H.; Jenh, Y.-J.; Wu, S.-K.; Chen, Y.-S.; Hanagata, N.; Lin, F.-H. Non-invasive Photodynamic Therapy in Brain Cancer by Use of Tb3+-Doped LaF3 Nanoparticles in Combination with Photosensitizer Through X-ray Irradiation: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhou, Z.; Pratx, G.; Chen, X.; Chen, H. Nanoscintillator-Mediated X-Ray Induced Photodynamic Therapy for Deep-Seated Tumors: From Concept to Biomedical Applications. Theranostics 2020, 10, 1296–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

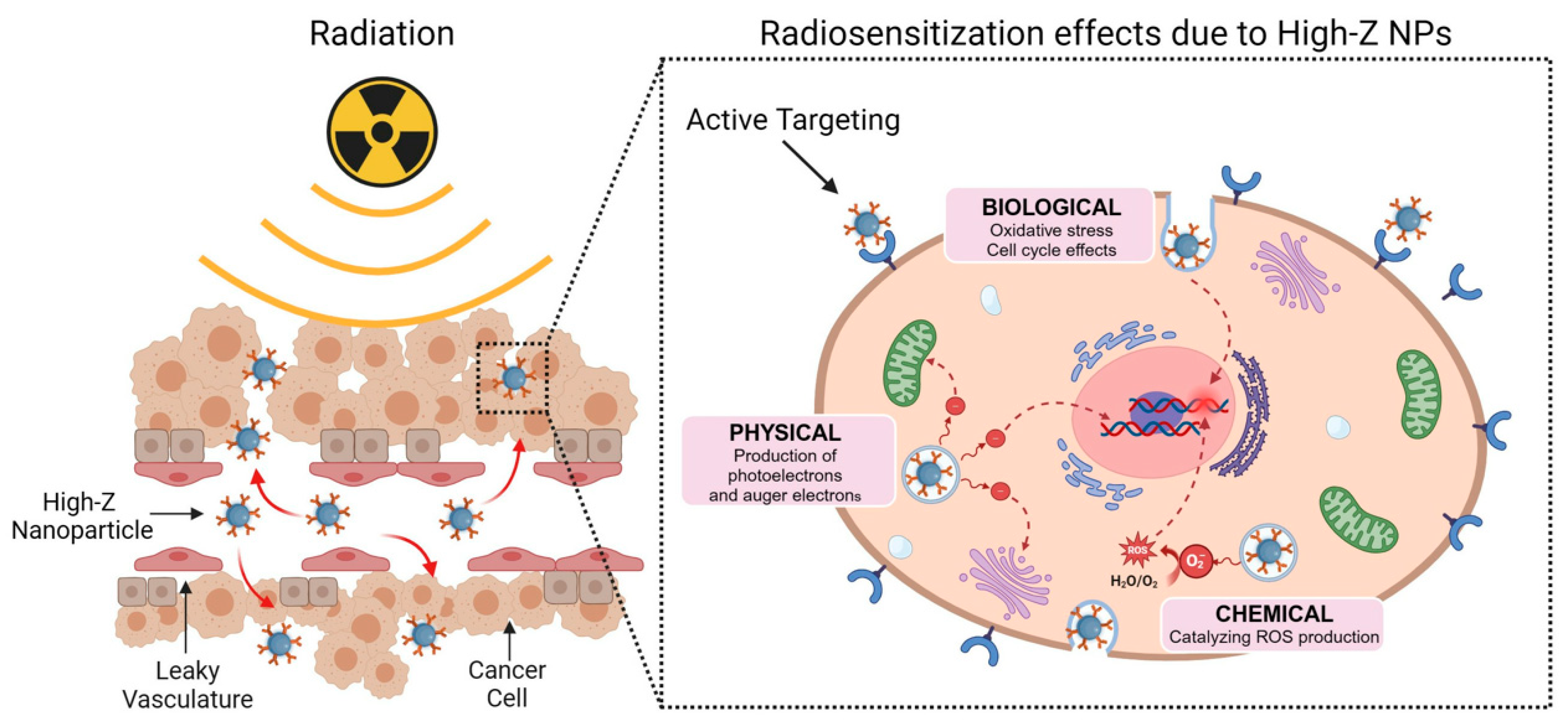

- Jackson, N.; Cecchi, D.; Beckham, W.; Chithrani, D.B. Application of High-Z Nanoparticles to Enhance Current Radiotherapy Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; McKelvey, K.J.; Guller, A.; Fayzullin, A.; Campbell, J.M.; Clement, S.; Habibalahi, A.; Wargocka, Z.; Liang, L.; Shen, C.; et al. Application of Mitochondrially Targeted Nanoconstructs to Neoadjuvant X-ray-Induced Photodynamic Therapy for Rectal Cancer. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Shu, T.; Deng, W.; Shen, C.; Wu, Y. An X-ray activatable gold nanorod encapsulated liposome delivery system for mitochondria-targeted photodynamic therapy (PDT). J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 4539–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Pal, K. Exploration of polydopamine capped bimetallic oxide (CuO-NiO) nanoparticles inspired by mussels for enhanced and targeted paclitaxel delivery for synergistic breast cancer therapy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 626, 157266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Liu, N.; Chang, Z.; Liu, J.; Jin, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhu, X. Single-site bimetallic nanosheet for imaging guided mutually-reinforced photothermal-chemodynamic therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442, 136125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, R.; Ninakanti, R.; Bals, S.; Verbruggen, S.W. Plasmon resonance of gold and silver nanoparticle arrays in the Kretschmann (attenuated total reflectance) vs. direct incidence configuration. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahinez, D.; Reji, T.; Andreas, R. Modeling of the surface plasmon resonance tunability of silver/gold core-shell nanostructures. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 19616–19626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.-K.; Sanders, C. Chapter 3—Low-loss plasmonic metals epitaxially grown on semiconductors. In Plasmonic Materials and Metastructures; Gwo, S., Alù, A., Li, X., Shih, C.-K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Mu, X.; Ma, A.; Guo, S. Raman tags: Novel optical probes for intracellular sensing and imaging. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Liow, C.H.; Zhang, M.; Huang, R.; Li, C.; Shen, H.; Liu, M.; Zou, Y.; Gao, N.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Surface plasmon resonance enhanced light absorption and photothermal therapy in the second near-infrared window. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15684–15693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravets, V.G.; Kabashin, A.V.; Barnes, W.L.; Grigorenko, A.N. Plasmonic Surface Lattice Resonances: A Review of Properties and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 5912–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xi, J.; Lee, D.; Ramella-Roman, J.; Li, X. Gold Nanocages with a Long SPR Peak Wavelength as Contrast Agents for Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging at 1060 nm. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Luo, Y.; Chang, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Gan, L.; Huang, Y.; Sun, Q. BSA-Coated Gold Nanorods for NIR-II Photothermal Therapy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilipour, M.; Moshaii, A.; Siampour, H. Controlled electrochemical fabrication of large and stable gold nanorods with reduced cytotoxicity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, P.; Ai, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Gao, J.; Sun, Z. Fabrication of Ag/ZnO composite nanoflowers for ultrasensitive and recyclable SERS detection toward Rhodamine 6G. Opt. Mater. 2025, 168, 117485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Syadi, A.M.; Faisal, M.; Harraz, F.A.; Jalalah, M.; Alsaiari, M. Immersion-plated palladium nanoparticles onto meso-porous silicon layer as novel SERS substrate for sensitive detection of imidacloprid pesticide. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Tang, Z.; Huo, T.; Wu, D.; Tang, J.H. Ag/Au Bimetallic Core–Shell Nanostructures: A Review of Synthesis and Applications. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Yang, Q.; Tong, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y. Morphology-Preserved Ag Alloying in Au Nanosheets Enables Tunable NIR-I/II Plasmonics for Enhanced Photothermal Conversion. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 16915–16925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Aslam, H.; Sohail, J.; Umar, A.; Ullah, A.; Ullah, H. Golden insights for exploring cancer: Delivery, from genes to the human body using bimetallic Au/Ag nanostructures. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awiaz, G.; Lin, J.; Wu, A. Recent advances of Au@Ag core-shell SERS-based biosensors. Exploration 2023, 3, 20220072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, T.; Pan, X.; Deng, Z.; Huang, J.; Mo, X.; Shen, X.; Qin, X.; Yang, X.; Gao, M.; et al. CD44 and αV-integrins dual-targeting bimetallic nanozymes for lung adenocarcinoma therapy via NIR-enhanced ferroptosis/apoptosis. Biomaterials 2025, 323, 123407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Sun, Q.; Huang, L.; Xia, Y.; Wang, J.; Mo, D.; Butch, C.J.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.; et al. Dual-Targeting Mn@CeO2 Nanozyme-Modified Probiotic Hydrogel Microspheres Reshape Gut Homeostasis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 31619–31642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajare, B.; Kanp, T.; Aalhate, M.; Dhuri, A.; Manoharan, B.; Rode, K.; Nair, R.; Paul, P.; Singh, P.K. Emerging Paradigms in Nanozyme: Strategies in Fabrication, Cancer Targeting, and Biosensing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 6588–6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Li, A.; Huang, H.; Ni, C.; Cao, X.; Shi, X.; Guo, R. Dendrimer-Entrapped CuPt Bimetallic Nanozymes for Tumor Microenvironment-Regulated Photothermal/Catalytic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 30716–30730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.M.; Ju, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.; Jung, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, D. A metastasis suppressor Pt-dendrimer nanozyme for the alleviation of glioblastoma. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 4015–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, L.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, J.; Pan, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, D.; Jiao, L.; Fu, C. A Mitochondria-Targeted Nanozyme Platform for Multi-Pathway Tumor Therapy via Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis Regulation. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e17616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Chen, K.Z.; Qiao, S.L. Advances of Layered Double Hydroxide-Based Materials for Tumor Imaging and Therapy. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202400010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Ding, B.; Chen, H.; Meng, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Z.; Ma, X.; Han, D.; Yang, M.; et al. Gallium-Magnesium Layered Double Hydroxide for Elevated Tumor Immunotherapy Through Multi-Network Synergistic Regulation. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2501256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Wei, K.; Pei, Z.; Gong, F.; Chen, L.; Han, Z.; Yang, Y.; Dai, Y.; et al. Bioactive Layered Double Hydroxides for Synergistic Sonodynamic/Cuproptosis Anticancer Therapy with Elicitation of the Immune Response. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 10495–10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tűz, B.; Correia, I.; Martinho, P.N. A critical analysis of the potential of iron heterobimetallic complexes in anticancer research. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2025, 264, 112813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.B.; Sipos, É.; Bényei, A.C.; Nagy, S.; Lekli, I.; Buglyó, P. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Co(III)/Ru(II) Heterobimetallic Complexes as Hypoxia-Activated Iron-Sequestering Anticancer Prodrugs. Molecules 2024, 29, 5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katifelis, H.; Mukha, I.; Bouziotis, P.; Vityuk, N.; Tsoukalas, C.; Lazaris, A.C.; Lyberopoulou, A.; Theodoropoulos, G.E.; Efstathopoulos, E.P.; Gazouli, M. Ag/Au Bimetallic Nanoparticles Inhibit Tumor Growth and Prevent Metastasis in a Mouse Model. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6019–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Timmons, D.J.; Yuan, D.; Zhou, H.C. Tuning the topology and functionality of metal-organic frameworks by ligand design. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Guo, D.; Wang, N.; Wang, H.F.; Yang, X.; Shen, K.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. Defect Engineered Metal-Organic Framework with Accelerated Structural Transformation for Efficient Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202311909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Sun, X.; Gu, H.; Niu, Z.; Braunstein, P.; Lang, J.P. Engineering the Electronic Structures of Metal-Organic Framework Nanosheets via Synergistic Doping of Metal Ions and Counteranions for Efficient Water Oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 15133–15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, D.; Xie, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Liao, Y.; Li, H. HIFU postoperative hypoxia enables metal-organic frameworks amplifying banoxantrone and STING activation for enhanced immunotherapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Sun, S.; Gong, C.; Yang, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Dong, H. Ag-Doped Metal-Organic Frameworks’ Heterostructure for Sonodynamic Therapy of Deep-Seated Cancer and Bacterial Infection. ACS Nano 2022, 17, 1174–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xu, D.; Hu, X.; Zhu, W.; Kong, L.; Qian, Z.; Mei, J.; Ma, R.; Shang, X.; Fan, W.; et al. Biodegradable oxygen-evolving metalloantibiotics for spatiotemporal sono-metalloimmunotherapy against orthopaedic biofilm infections. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, P.D.; Magalhães, F.D.; Pereira, R.F.; Pinto, A.M. Metal-Organic Frameworks Applications in Synergistic Cancer Photo-Immunotherapy. Polymers 2023, 15, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, W.; Yu, S.; Xia, S.L.; Liu, Y.N.; Yang, G.J. Application of MOF-based nanotherapeutics in light-mediated cancer diagnosis and therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lismont, M.; Dreesen, L.; Wuttke, S. Metal-Organic Framework Nanoparticles in Photodynamic Therapy: Current Status and Perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1606314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, X.; Liang, J.; Chao, H. Current roles of metals in arming sonodynamic cancer therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 521, 216169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Hua, Y.; Cai, Z. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy: Present and emerging inducers. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 4854–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmpilis, A.I.; Paschalis, A.; Mourkakis, A.; Christodoulou, P.; Kostopoulos, I.V.; Antimissari, E.; Terzoudi, G.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Armpilia, C.; Papageorgis, P.; et al. Immunogenic Cell Death, DAMPs and Prothymosin α as a Putative Anticancer Immune Response Biomarker. Cells 2022, 11, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, S.; Rennen, S.; Agostinis, P. Decoding immunogenic cell death from a dendritic cell perspective. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 321, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Zitvogel, L. Immunogenic Cell Death in Cancer Therapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Chen, H.; Tan, J.; Meng, Q.; Zheng, P.; Ma, P.; Lin, J. ZIF-8 Nanoparticles Evoke Pyroptosis for High-Efficiency Cancer Immunotherapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202215307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Li, M. Near-Infrared-II Plasmonic Trienzyme-Integrated Metal-Organic Frameworks with High-Efficiency Enzyme Cascades for Synergistic Trimodal Oncotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2200871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, W.; Li, T.; Wang, M.; Gao, Y.; Ma, S.; Feng, Y.; Du, S.; Lan, P.; et al. Boosting Glioblastoma Therapy with Targeted Pyroptosis Induction. Small 2023, 19, e2207604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Han, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, Y.; Shao, B.; Miao, Q.; Shi, Z.; Yan, F.; Feng, S. UiO-66 MOFs-Based “Epi-Nano-Sonosensitizer” for Ultrasound-Driven Cascade Immunotherapy against B-Cell Lymphoma. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 6282–6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fu, Y.; Feng, K.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Xu, Y.; Tian, H.; et al. Polydopamine-coated UiO-66 nanoparticles loaded with perfluorotributylamine/tirapazamine for hypoxia-activated osteosarcoma therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lu, Y.; Dong, C.; Zhao, W.; Wu, X.; Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; Yao, T.; Shi, S. A Ru(II) Polypyridyl Alkyne Complex Based Metal-Organic Frameworks for Combined Photodynamic/Photothermal/Chemotherapy. Chemistry 2020, 26, 1668–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cun, J.E.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, Q.; Gao, W.; Luo, K.; He, B.; Pu, Y. Photo-enhanced upcycling H2O2 into hydroxyl radicals by IR780-embedded Fe3O4@MIL-100 for intense nanocatalytic tumor therapy. Biomaterials 2022, 287, 121687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, K.; Zhou, Y.; Quan, G.; Wen, X.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Microneedle-mediated delivery of MIL-100(Fe) as a tumor microenvironment-responsive biodegradable nanoplatform for O2-evolving chemophototherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 6772–6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Liu, H.; Guo, L.; Tang, Y.; Lan, T.; Zhou, R.; Xu, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; et al. MIL-100(Fe)-based Co-delivery platform as cascade synergistic chemotherapy and immunotherapy agents for colorectal cancer via the cGAS-STING pathway. Acta Biomater. 2025, 204, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.M.; Li, R.T.; Yu, L.; Huang, T.; Peng, J.; Meng, W.; Sun, B.; Zhang, W.H.; Jiang, Z.H.; Chen, J.; et al. Reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment using a PCN-224@IrNCs/D-Arg nanoplatform for the synergistic PDT, NO, and radiosensitization therapy of breast cancer and improving anti-tumor immunity. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 10715–10729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Chen, J.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, C.; Huang, P.; Mao, Z.; Tong, W. Erythrocyte Membrane-Camouflaged PCN-224 Nanocarriers Integrated with Platinum Nanoparticles and Glucose Oxidase for Enhanced Tumor Sonodynamic Therapy and Synergistic Starvation Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 24532–24542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Lau, A.; Novosselov, I.V. HKUST-1 MOF nanoparticles: A non-classical crystallization route in supercritical CO2. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 22142–22151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Chen, Y.; Shan, W.; Hui, T.; Ilham, M.; Wu, J.; Zhou, C.; Yu, L.; Qiu, M. HKUST-1 loaded few-layer Ti3C2Tx for synergistic chemo-photothermal effects to enhance antibacterial activity. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 3929–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhao, S.; Nice, E.C.; Huang, C.; He, W.; Zou, B.; Lin, J. A cascaded copper-based nanocatalyst by modulating glutathione and cyclooxygenase-2 for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2022, 607, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Li, B.; Shang, P. Recent advances in polydopamine-coated metal–organic frameworks for cancer therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1553653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, C.; Lv, X.; Dai, H.; Zhong, Z.; Liang, C.; Wang, W.; Huang, W.; Song, X.; Dong, X. A H2O2 self-sufficient nanoplatform with domino effects for thermal-responsive enhanced chemodynamic therapy. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 1926–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Shi, J.; Liu, Z. Metal–organic framework-encapsulated nanoparticles for synergetic chemo/chemodynamic therapy with targeted H2O2 self-supply. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 15870–15877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. Glucose oxidase and metal catalysts combined tumor synergistic therapy: Mechanism, advance and nanodelivery system. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.H.; Wan, Y.; Qi, C.; He, J.; Li, C.; Yang, C.; Xu, H.; Lin, J.; Huang, P. Nanocatalytic Theranostics with Glutathione Depletion and Enhanced Reactive Oxygen Species Generation for Efficient Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2006892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Saw, P.E.; Xu, L. Long-Circulating Theranostic 2D Metal-Organic Frameworks with Concurrent O2 Self-Supplying and GSH Depletion Characteristic for Enhanced Cancer Chemodynamic Therapy. Small Methods 2022, 6, e2200178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, A.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, D. A Review on Metal- and Metal Oxide-Based Nanozymes: Properties, Mechanisms, and Applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Shu, G.; Shen, L.; Ding, J.; Qiao, E.; Fang, S.; Song, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Lu, C.; et al. Biomimetic mesoporous polydopamine nanoparticles for MRI-guided photothermal-enhanced synergistic cascade chemodynamic cancer therapy. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 5262–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Liang, X.; Wei, M.; Shi, D.; Gou, J.; Yin, T.; He, H.; Tang, X.; et al. pH-Activatable copper-axitinib coordinated multifunctional nanoparticles for synergistic chemo-chemodynamic therapy against aggressive cancers. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 6267–6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Jia, N. PDA-coated CPT@MIL-53(Fe)-based theranostic nanoplatform for pH-responsive and MRI-guided chemotherapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 1821–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Xiao, Y.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Gu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q. Tumor microenvironment sensitization via dual-catalysis of carbon-based nanoenzyme for enhanced photodynamic therapy. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2024, 663, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Sevencan, C.; Li, B.L. Functionalized MoS2-Based Nanomaterials for Cancer Phototherapy and Other Biomedical Applications. ACS Mater. Lett. 2021, 3, 462–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G.; Hao, G.; Sun, Y.; Cao, J. Strategies to improve photodynamic therapy efficacy by relieving the tumor hypoxia environment. NPG Asia Mater. 2021, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Xie, Z.; Ding, B.; Shao, S.; Liang, S.; Pang, M.; Lin, J. Monodispersed Copper(I)-Based Nano Metal-Organic Framework as a Biodegradable Drug Carrier with Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy Efficacy. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungcharoen, P.; Thivakorakot, K.; Thientanukij, N.; Kosachunhanun, N.; Vichapattana, C.; Panaampon, J.; Saengboonmee, C. Magnetite nanoparticles: An emerging adjunctive tool for the improvement of cancer immunotherapy. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 2024, 5, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Lu, M. Study on the thermal field distribution of cholangiocarcinoma model by magnetic fluid hyperthermia. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi 2021, 38, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Tomar, R.; Chakraverty, S.; Sharma, D. Effect of manganese doping on the hyperthermic profile of ferrite nanoparticles using response surface methodology. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 16942–16954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Na, Y.R.; Na, C.M.; Im, P.W.; Park, H.W.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, Y.; You, J.H.; Kang, D.S.; Moon, H.E.; et al. 7-nm Mn0.5 Zn0.5Fe2O4 superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle (SPION): A high-performance theranostic for MRI and hyperthermia applications. Theranostics 2025, 15, 2883–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pan, X.; Wu, Q.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, H. Manganese carbonate nanoparticles-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction for enhanced sonodynamic therapy. Exploration 2021, 1, 20210010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunziata, G.; Borroni, A.; Rossi, F. Advanced microfluidic strategies for core-shell nanoparticles: The next-generation of polymeric and lipid-based drug nanocarriers. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2025, 22, 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Prakash, G.; Ozturk, A.; Saghazadeh, S.; Sohail, M.F.; Seo, J.; Dockmeci, M.; Zhang, Y.S.; Khademhosseini, A. Evolution and Clinical Translation of Drug Delivery Nanomaterials. Nano Today 2017, 15, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellicoe, M.; Yang, L.; He, S.; Lobel, B.; Young, D.; Harvie, A.; Bourne, R.; Elbourne, A.; Chamberlain, T. Flowing into the Future: The Promise and Challenges of Continuous Inorganic Nanoparticle Synthesis and Application. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Al Zaki, A.; Hui, J.Z.; Muzykantov, V.R.; Tsourkas, A. Multifunctional nanoparticles: Cost versus benefit of adding targeting and imaging capabilities. Science 2012, 338, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hheidari, A.; Mohammadi, J.; Ghodousi, M.; Mahmoodi, M.; Ebrahimi, S.; Pishbin, E.; Rahdar, A. Metal-based nanoparticle in cancer treatment: Lessons learned and challenges. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1436297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, A.; Yu, X.; Tian, Z.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, J. Microfluidic Synthesis of Multifunctional Micro-/Nanomaterials from Process Intensification: Structural Engineering to High Electrochemical Energy Storage. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 20957–20979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotouček, J.; Hubatka, F.; Mašek, J.; Kulich, P.; Velínská, K.; Bezděková, J.; Fojtíková, M.; Bartheldyová, E.; Tomečková, A.; Stráská, J.; et al. Preparation of nanoliposomes by microfluidic mixing in herring-bone channel and the role of membrane fluidity in liposomes formation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrada Cespedes, A.; Reyes, M.; Morales, J.O. Advanced drug delivery systems for oral squamous cell carcinoma: A comprehensive review of nanotechnology-based and other innovative approaches. Front. Drug Deliv. 2025, 5, 1596964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, X.; Sun, Q. Application of Metal-Doped Nanomaterials in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Nanotheranostics 2025, 6, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040035

Jin X, Sun Q. Application of Metal-Doped Nanomaterials in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Journal of Nanotheranostics. 2025; 6(4):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040035

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Xinhao, and Qi Sun. 2025. "Application of Metal-Doped Nanomaterials in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment" Journal of Nanotheranostics 6, no. 4: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040035

APA StyleJin, X., & Sun, Q. (2025). Application of Metal-Doped Nanomaterials in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Journal of Nanotheranostics, 6(4), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jnt6040035