1. Introduction

The convergence of Internet of Things (IoT) technology with financial markets has fundamentally transformed how market data is collected, processed, and analyzed [

1,

2]. Modern cryptocurrency trading operates through distributed networks of autonomous nodes—exchanges, market makers, liquidity providers, and data aggregators—that function as financial IoT devices generating continuous streams of orderbook updates, transaction records, and pricing signals [

3,

4]. This architectural shift from centralized financial infrastructure to distributed edge computing systems creates new opportunities for collaborative intelligence while introducing fundamental challenges in privacy preservation and trust management.

Unlike traditional centralized financial infrastructure, these blockchain-based systems embody core IoT principles: distributed data generation at the edge, autonomous decision-making by individual nodes, and decentralized coordination without central authorities [

5]. Each cryptocurrency exchange effectively operates as an edge computing node with local processing capabilities, proprietary data sources, and real-time analytics requirements. Major exchanges like Binance and Coinbase maintain distributed matching engines that process millions of orderbook updates daily, execute trades within microseconds, and generate proprietary market microstructure data that remains siloed within their infrastructure [

6,

7]. These platforms deploy machine learning models locally for fraud detection, market making, and price prediction without sharing raw transaction data with competitors or third parties.

This distributed financial IoT architecture creates unique challenges for collaborative machine learning [

1]. First, extreme data heterogeneity—different exchanges observe fundamentally different market microstructures (Bitcoin spreads of 0.001 bps versus altcoin spreads of 500+ bps [

8,

9]) rather than statistical samples from a common distribution. Second, competitive dynamics prevent direct data sharing since trading strategies and order flow constitute proprietary intellectual property [

10,

11]. Third, temporal non-stationarity causes cryptocurrency market regimes to shift rapidly (pre-halving versus post-halving dynamics), requiring models to adapt across time periods that individual nodes may not observe completely [

12]. Individual nodes possess fragmentary views of global market dynamics—one exchange observes Bitcoin trading patterns on its platform but lacks visibility into order flow at competing venues. A market maker accumulates proprietary signals for specific asset pairs but misses correlations emerging across broader cryptocurrency ecosystems. Pooling knowledge across these distributed financial IoT nodes could improve predictive models for all participants, yet direct data sharing conflicts with competitive dynamics, regulatory requirements, and fundamental trust management challenges in decentralized networks. Financial data contains sensitive information about trading strategies, institutional positions, and client behavior that nodes cannot legally or strategically reveal to potential competitors or centralized aggregators.

Machine learning has become central to modern financial markets. Institutional traders deploy neural networks to predict price movements, optimize execution strategies, and manage risk across increasingly complex portfolios (Cartea et al., 2015 [

13]). Cryptocurrency markets have proven particularly receptive to these methods—recent work demonstrates that deep learning architectures substantially outperform traditional statistical approaches for price forecasting and trading signal generation (Zhang et al., 2024 [

14]; Kang et al., 2025 [

15]). The application space continues expanding as orderbook microstructure data becomes more accessible and computational resources grow cheaper.

Yet a paradox limits progress. The most valuable predictive models require diverse training data spanning multiple assets, exchanges, time periods, and market conditions. Individual institutions—whether cryptocurrency exchanges, hedge funds, or market makers—hold fragments of this information space. One exchange observes Bitcoin trading on its platform but lacks visibility into competitor order flow. A trading desk accumulates proprietary signals for a subset of assets but misses patterns emerging in adjacent markets. Pooling these datasets would improve model quality for all participants, but direct data sharing conflicts with competitive dynamics and regulatory requirements. Financial data contains sensitive information about trading strategies, client positions, and institutional behavior that firms cannot legally or strategically reveal.

This tension between collaboration benefits and privacy constraints has intensified as cryptocurrency markets mature. Unlike traditional equity markets with established clearinghouses and standardized data vendors, cryptocurrency trading fragments across hundreds of decentralized exchanges with limited information sharing (Makarov and Schoar, 2020 [

16]). Price prediction studies uniformly assume centralized data access—researchers download historical data from a single API and train models with complete observability (Golnari et al., 2024 [

17]; Yang et al., 2025 [

10]). This centralized paradigm works for academic research but fails in practice when multiple institutions want to collaborate without exposing proprietary information.

Federated learning offers a potential path forward. The core idea is simple: instead of pooling raw data at a central location, participants train models locally and share only parameter updates (Ferenczi and Bădică, 2024 [

18]). A coordination server aggregates these updates to produce a global model that incorporates knowledge from all participants without any institution observing others’ training data. This framework has succeeded in applications like mobile keyboard prediction and medical imaging, where privacy concerns similarly prohibit centralized data collection.

Financial markets present unique challenges that existing federated learning work has not addressed. First, financial data exhibits extreme heterogeneity—different participants hold fundamentally different distributions rather than statistical samples from a common population. A Bitcoin specialist exchange observes tight spreads and high-frequency dynamics, while an altcoin-focused platform sees wide spreads and sparse liquidity. Temporal non-stationarity compounds this: cryptocurrency markets shift between bull and bear regimes, regulatory shocks, and technological transitions that alter underlying patterns. Standard federated algorithms like FedAvg struggle under such heterogeneity, often converging slowly or producing models worse than individual local training (Li et al., 2020 [

19]).

Second, financial applications demand stronger privacy guarantees than parameter sharing alone provides. Recent work shows that model updates can leak information about training data through gradient inversion attacks (Ovi and Gangopadhyay, 2023 [

20]). An adversarial aggregation server could potentially reconstruct individual trades, infer institutional positions, or detect proprietary signals from the parameter updates it receives. These gradient inversion risks are particularly severe in cryptocurrency markets where blockchain transparency means that linking a participant’s identity to their trading patterns could expose profitable strategies competitors could exploit.

Third, the profit-driven nature of financial prediction requires careful attention to utility costs. In domains like medical imaging, a 2% accuracy reduction from privacy mechanisms may be acceptable given the social value of collaborative learning [

21]. In algorithmic trading, where accuracy directly translates to profit, even small degradations matter. Understanding these privacy-utility tradeoffs empirically becomes critical for practical deployment decisions. Even moderate accuracy degradation could translate to significant economic costs in algorithmic trading where profit margins are measured in basis points.

Current literature on cryptocurrency prediction focuses almost entirely on centralized learning scenarios. Zhong et al. (2023) [

22] develop LSTM-ReGAT, a network-centric approach incorporating cryptocurrency interrelations, achieving improved price trend prediction through graph attention mechanisms. Kang et al. (2025) [

15] demonstrate that integrating deep learning models with technical indicators like Bollinger Bands significantly enhances trading strategy robustness, with some configurations achieving Sharpe ratios exceeding 3.5. Youssefi et al. (2025) [

23] systematically evaluate over 130 technical indicators for feature selection in cryptocurrency forecasting, finding that careful indicator choice substantially impacts model performance. Zhang et al. (2024) [

14] survey deep learning applications across cryptocurrency research, covering price prediction, portfolio construction, and bubble analysis, but all reviewed studies assume centralized data access.

The microstructure literature provides important context for our orderbook-based approach. Cont et al. (2012) [

24] establish that price changes correlate linearly with order flow imbalance—the imbalance between supply and demand at best bid and ask prices—with slope inversely proportional to market depth. This foundational result justifies our use of orderbook features as primary predictors. Hautsch and Huang (2012) [

25] quantify the short-run and long-run price impact of limit orders using high-frequency cointegrated VAR models, showing that limit order effects depend on aggressiveness, size, and book state. Liu et al. (2025) [

26] document liquidity commonality in cryptocurrency markets, finding strong co-movement of individual coin liquidity with overall market liquidity and inverted U-shaped intraday patterns. These microstructure insights inform our feature engineering but do not address distributed learning scenarios.

Work on selective classification—the practice of rejecting predictions when confidence is low to improve accuracy on executed decisions—provides methodological foundations for our confidence-based trading approach. El-Yaniv and Wiener (2010) [

27] characterize risk–coverage tradeoffs in noise-free settings, establishing theoretical bounds on achievable performance when trading classifier coverage for higher accuracy. Geifman and El-Yaniv (2017) [

28] extend these ideas to deep neural networks, demonstrating that selective classification can achieve unprecedented accuracy (2% top-5 ImageNet error with 99.9% probability) by rejecting uncertain predictions. Our trading framework implements similar principles: the model executes trades only when prediction confidence exceeds threshold

, creating a profit–coverage tradeoff analogous to the risk–coverage curves in classification literature. Unlike traditional three-class formulations (buy/hold/sell) that suffer from class imbalance and require arbitrary threshold tuning (Kang et al., 2025) [

15], our two-class approach with confidence-based execution provides explicit control over the accuracy–coverage tradeoff. This differs from fixed-threshold strategies commonly used in cryptocurrency trading literature (Zhang et al., 2024) [

14] and offers more flexibility for risk management than confidence-agnostic execution policies.

Classical financial econometrics provides the statistical foundation for our approach. Campbell et al. (1997) [

29] establish core principles of empirical finance including tests of market efficiency, asset return predictability, and microstructure modeling that inform our experimental design. Almgren and Chriss (2001) [

30] develop optimal execution theory that considers volatility risk and transaction costs—considerations we incorporate through our stop-loss constraints and fixed transaction cost assumptions. Sharpe (1994) [

31] introduces the risk-adjusted return metric we use to evaluate trading strategies. These classical references ground our work in established financial theory even as we push toward privacy-preserving collaborative learning.

The backtest overfitting problem identified by Bailey et al. (2014) [

32] motivates our temporal validation approach. They prove that high simulated performance becomes easily achievable after trying relatively few strategy configurations, creating false confidence in backtest results. Our strict temporal split—training on data through June 2024, validating through August, testing through October—prevents look-ahead bias and ensures we evaluate genuinely out-of-sample performance [

33,

34]. We use two public datasets: the Kaggle “Top 100 Cryptocurrency 2020–2025” dataset providing daily OHLCV data for macro indicators, and the “Cryptocurrency Order Book Data” dataset containing minute-level orderbook snapshots for microstructure features. The temporal validation approach follows established best practices in financial machine learning to prevent backtest overfitting. The three-month test period remains limited compared to ideal evaluation horizons, but represents the longest feasible window given our data availability.

Recent work on momentum effects in cryptocurrencies informs our understanding of market dynamics. Hsieh et al. (2025) [

35] show that cryptocurrency momentum profits arise specifically in UP-UP regime transitions rather than all persistent states, suggesting that regime continuity and investor psychology drive returns in speculative markets. This finding implies that models trained on one regime may struggle to generalize to others—a concern our time-based partitioning strategy directly tests by forcing clients to aggregate knowledge across distinct temporal regimes.

Despite this extensive literature on cryptocurrency prediction, machine learning for finance, and market microstructure, no prior work evaluates federated learning for financial market prediction under realistic data heterogeneity. Existing federated learning research focuses primarily on computer vision, natural language processing, and healthcare applications where data distributions differ less dramatically than in financial markets. The few financial federated learning studies address simpler tasks like credit scoring or operate on artificially partitioned homogeneous data that does not reflect the genuine heterogeneity institutions face.

This study makes three primary contributions. First, we develop a privacy-preserving federated learning framework tailored for financial time series prediction that combines differential privacy with Shamir secret sharing for dual-layer protection. Our per-layer gradient clipping and Rényi differential privacy composition minimize utility loss while providing formal privacy guarantees. Second, we conduct the first large-scale empirical evaluation of federated learning on cryptocurrency market prediction using 5.6 million orderbook observations with genuine data heterogeneity across three realistic partitioning strategies. Third, we quantify the privacy-utility tradeoff concretely: federated learning imposes 9–15 percentage point accuracy costs driven by data heterogeneity, while adding differential privacy and cryptographic protection increases this by less than 0.3 percentage points when calibrated appropriately.

Our findings reveal that the privacy mechanisms work—formal privacy protection adds negligible additional cost beyond the inherent challenges of distributed training. The dominant obstacle is the federated learning gap itself: parameter averaging across heterogeneous local objectives creates optimization challenges that current algorithms do not resolve. This insight shifts the research agenda: rather than further optimizing differential privacy accounting or cryptographic protocols, future work should focus on developing federated optimization algorithms robust to the extreme non-IID conditions characteristic of financial data.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on deep learning for financial markets, privacy-preserving machine learning, and federated learning applications.

Section 3 describes our system architecture comparing centralized, federated, and privacy-preserving federated paradigms.

Section 4 details the privacy mechanisms including differential privacy with RDP composition, Shamir secret sharing implementation, and per-layer noise calibration.

Section 5 presents the cryptocurrency market case study including dataset description, federated partitioning strategies, and evaluation protocols.

Section 6 reports experimental results across centralized baseline, federated learning without privacy, and privacy-preserving variants.

Section 7 discusses the federated learning performance gap, negligible privacy costs under appropriate calibration, altered confidence calibration, and comparison with state-of-the-art.

Section 8 concludes with practical implications and future research directions.

3. Distributed IoT System Architecture for Financial Analytics

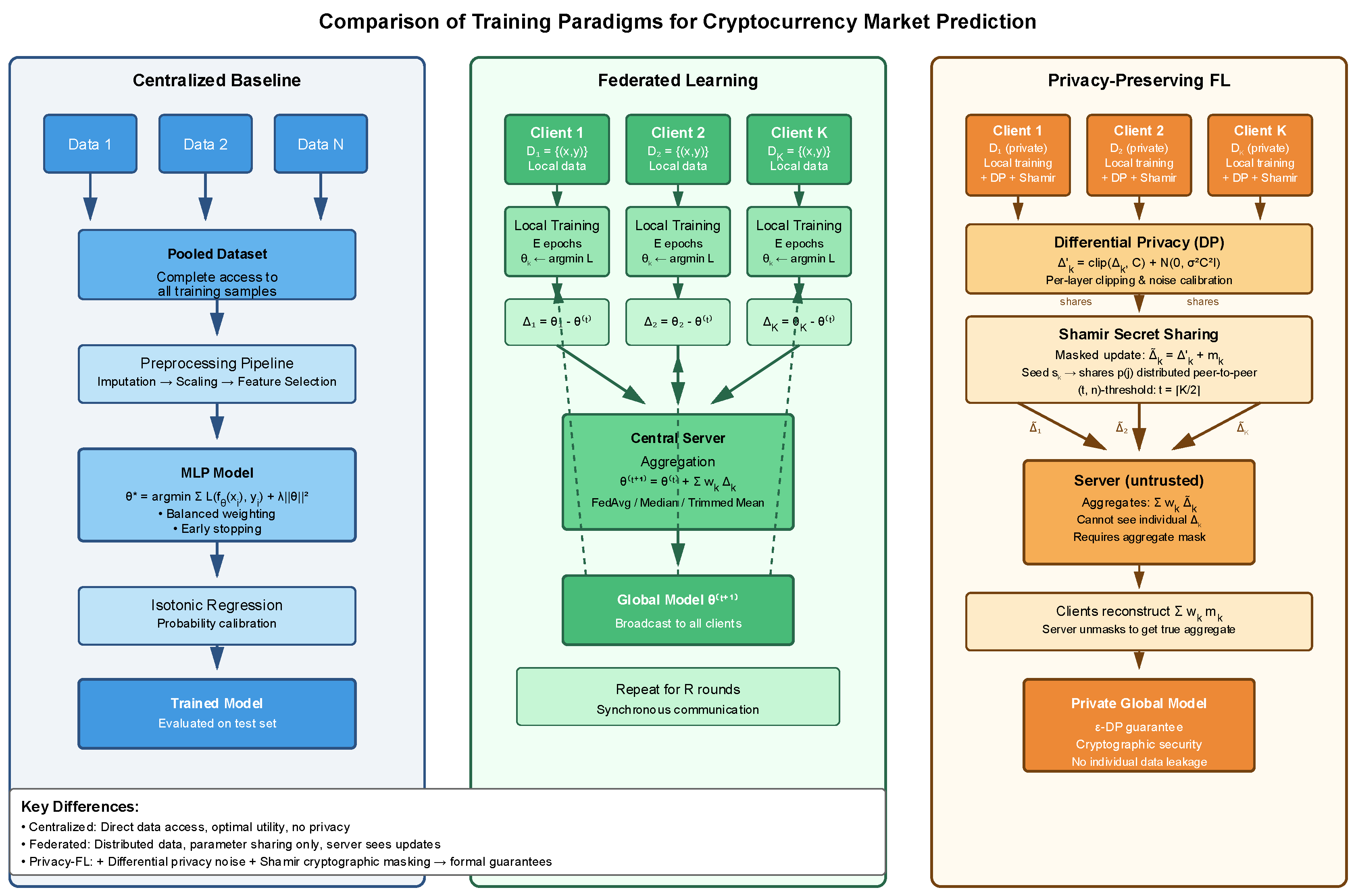

We compare three training paradigms for cryptocurrency market prediction (

Figure 1): A centralized baseline, standard federated learning, and privacy-preserving federated learning. All three use the same underlying neural network architectures and prediction tasks, allowing direct performance comparison under different privacy constraints.

Our architecture models cryptocurrency market participants as distributed IoT nodes in a financial edge computing network. Each node represents an autonomous entity—cryptocurrency exchange, trading desk, or market data provider—that locally collects and processes financial sensor data (orderbook snapshots, transaction streams, price feeds). This distributed IoT paradigm contrasts with traditional centralized financial systems where all data flows to central servers for processing.

The three training paradigms we compare reflect different trust and infrastructure models for financial IoT:

Centralized Cloud Processing: All edge nodes upload raw data to a central cloud server with complete visibility—the traditional paradigm that maximizes data utilization but creates privacy vulnerabilities and single points of trust failure.

Standard Federated Edge Learning: Edge nodes train local models on their private data and communicate only parameter updates to a coordination server. This distributed approach respects data locality and reduces bandwidth requirements, aligning with IoT edge computing principles.

Privacy-Preserving Federated Edge Learning: Extends the federated model with cryptographic protections (Shamir secret sharing) and statistical privacy (differential privacy), addressing trust management requirements in adversarial IoT environments where coordination servers or peer nodes may be compromised.

Figure 1 illustrates the fundamental architectural distinctions between the three approaches. The centralized baseline pools all data at a single location, enabling unrestricted access but creating privacy vulnerabilities. The federated framework distributes computation to data owners, with clients performing local training and sending only parameter updates to the server. The privacy-preserving variant extends this by adding two protection layers: differential privacy injects calibrated noise into local updates before transmission, while Shamir secret sharing masks these updates cryptographically during aggregation. This dual-layer design addresses both statistical inference attacks and honest-but-curious server threats, though at the cost of additional computational overhead and potential utility degradation.

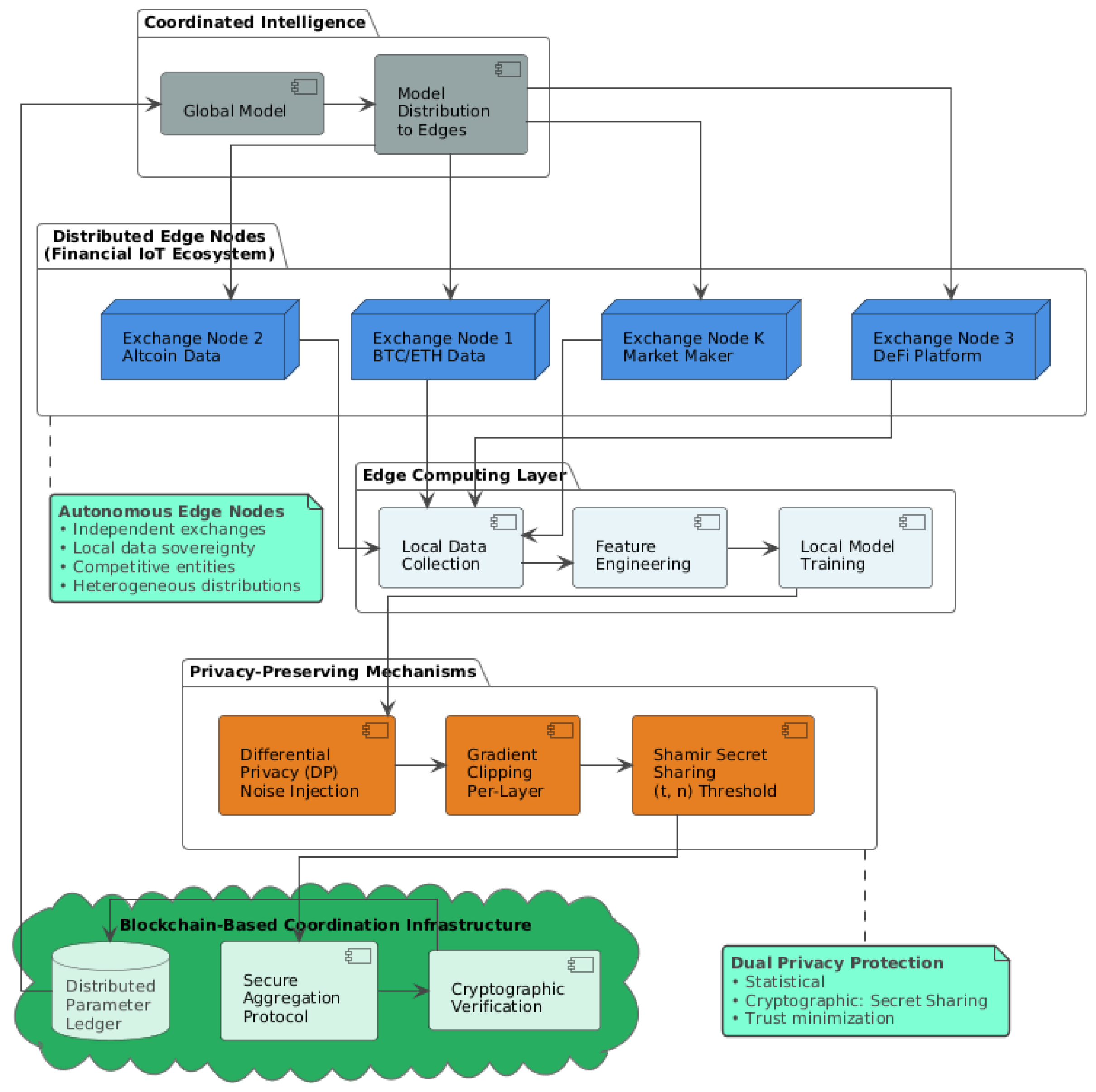

Figure 2 illustrates the architectural topology of our privacy-preserving federated learning framework positioned within a distributed financial IoT ecosystem. The system comprises three primary layers that reflect the operational reality of blockchain-based cryptocurrency markets. At the edge computing layer, autonomous nodes—cryptocurrency exchanges, decentralized finance platforms, and market makers—function as independent financial IoT devices generating continuous streams of orderbook data, transaction records, and pricing signals. Each edge node performs local data collection, feature engineering, and model training on its proprietary dataset without uploading raw market data to centralized infrastructure, preserving data sovereignty and competitive intelligence.

The privacy-preserving mechanism layer implements our dual-protection approach combining statistical and cryptographic defenses. Differential privacy with per-layer gradient clipping injects calibrated Gaussian noise into local model updates before transmission, providing formal privacy guarantees against inference attacks. Shamir secret sharing with (t, n) threshold cryptography then masks these noisy updates through polynomial-based secret splitting, ensuring that the coordination server cannot observe individual node contributions even during aggregation. This layered defense addresses both honest-but-curious aggregation servers and potential collusion among malicious edge nodes—threat models particularly relevant in competitive financial IoT environments where participants simultaneously cooperate on model training while competing for trading profits.

The blockchain-based coordination infrastructure serves three specific functions in our architecture. First, it provides an immutable audit trail of all aggregation rounds, recording cryptographic hashes of global model parameters at each communication step. This auditability enables post hoc verification that the aggregation server executed FedAvg correctly without tampering with individual updates. Second, the distributed parameter ledger ensures synchronization across edge nodes despite potential Byzantine failures or network partitions common in cryptocurrency infrastructure—each node can verify it received the canonical global model for round t by comparing against the blockchain-recorded hash. Third, smart contracts enforce the secure aggregation protocol, automatically rejecting malformed updates or parameter submissions that violate differential privacy constraints (e.g., exceed clipping thresholds). Cryptographic verification mechanisms validate that aggregated parameters derive from legitimate edge node updates rather than adversarial injections, while the distributed parameter ledger maintains synchronization across the network. This architecture embodies core IoT principles—autonomous edge devices, decentralized coordination, and minimal trust assumptions—adapted to the unique requirements of collaborative intelligence in adversarial financial ecosystems. The bidirectional communication pattern (edge to blockchain for parameter updates, blockchain to edge for global model distribution) operates synchronously across training rounds, ensuring all nodes receive consistent model states despite potential Byzantine failures or network partitions common in distributed blockchain systems.

The core prediction task remains consistent across all approaches: given orderbook microstructure features and macroeconomic indicators, predict directional price movements over a fixed time horizon. We frame this as binary classification (up vs. down) after filtering out samples within a deadband threshold around zero return. This two-class formulation maps naturally to trading decisions while avoiding the class imbalance problems inherent in three-class formulations.

3.1. Centralized Baseline

The centralized approach trains a single model on the complete dataset pooled from all data sources. This represents the standard machine learning paradigm where a central server has unrestricted access to all training samples.

We implement a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) that processes feature vectors directly. This architecture uses the preprocessing pipeline: feature imputation via median replacement, standardization via robust scaling, and optional feature selection via mutual information scoring.

The training procedure follows standard supervised learning. We use stochastic gradient descent with momentum, applying per-epoch training where each epoch processes the full training set. The model parameters are:

where

is the neural network,

is cross-entropy loss, and

controls L2 regularization.

We address class imbalance through balanced sample weighting. For each training sample, we compute weights inversely proportional to class frequency, ensuring the minority class contributes equally to gradient updates. This prevents the model from collapsing to majority-class predictions.

The training pipeline implements early stopping on a validation set split temporally from the training data. We monitor validation loss and halt training when no improvement occurs for a patience window. This prevents overfitting while maintaining computational efficiency.

For probability calibration, we apply isotonic regression as a post-processing step. The uncalibrated model outputs are transformed to better-calibrated probabilities via monotonic mapping fitted on the validation set. This improves the reliability of confidence-based trade execution decisions.

The final model selection uses a held-out test set, again split temporally to prevent look-ahead bias. We evaluate both classification metrics (accuracy, F1 score) and trading-specific metrics (directional accuracy on executed trades, profit per trade after transaction costs).

3.2. Federated Learning Framework

The federated approach distributes data across multiple clients, each holding a local partition. A central server coordinates training but never observes raw client data. This architecture matches scenarios where multiple entities possess proprietary datasets and want to collaborate without sharing their actual samples.

We partition the cryptocurrency dataset across clients using three strategies: (1) symbol-based allocation where each client holds all data for a subset of cryptocurrencies, (2) time-block allocation where each client holds all symbols but different temporal ranges, and (3) hash-based allocation for independent and identically distributed splits. These partitioning schemes simulate different data heterogeneity patterns that arise in practice.

Each client maintains a local dataset and a local model initialized from global parameters received from the server at round . The client performs local training for a fixed number of epochs, computing updated parameters .

Local training uses the same architecture and loss function as the centralized baseline. Each client minimizes:

starting from

and running for

local epochs. We implement balanced sample weighting within each client to handle local class imbalances.

After local training, clients compute parameter deltas:

These deltas represent the client’s proposed model updates based on their local data. The client sends to the server along with metadata (number of training samples, validation metrics).

The server aggregates client updates using one of several schemes. The simplest is FedAvg, which computes a weighted average:

where

weights clients by dataset size.

We also implement delta-based aggregation with server learning rate:

where

is a server-side learning rate that we decay during training. This allows finer control over global model updates and improves convergence stability.

For robustness against outlier updates, we implement coordinate-wise median and trimmed mean aggregation. The coordinate median computes element-wise medians across client parameters:

The trimmed mean removes the top and bottom fraction of values before averaging each coordinate. These methods provide Byzantine robustness, tolerating up to a fraction of malicious or failed clients.

The federated training loop alternates between local client training and global aggregation for a fixed number of rounds. We track both global validation metrics (by evaluating the global model on each client’s validation set) and per-client test metrics. This reveals whether the global model generalizes well to individual client distributions.

Client selection happens deterministically in our experiments: all clients participate in every round. This maximizes data utilization and simplifies the training protocol, though in practice, partial client participation may be necessary for scalability.

The communication pattern is synchronous: the server waits for all clients to complete local training before aggregating. Each round requires two communication steps: server-to-client parameter broadcast and client-to-server update upload. We measure the communication cost in terms of total bytes transmitted and number of synchronization barriers.

3.3. Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning

The privacy-preserving variant adds cryptographic and statistical protections to the federated framework. We combine Shamir secret sharing for secure aggregation with differential privacy for formal privacy guarantees. This dual-layer approach addresses two distinct threats: an honest-but-curious server that might inspect client updates, and inference attacks that could extract sensitive information from the final model.

3.3.1. Shamir Secret Sharing

We use a -threshold secret sharing scheme where any out of participants can reconstruct a secret, but or fewer learn nothing. Each client’s parameter update is protected during aggregation via this scheme.

The protocol works as follows. A client

wants to contribute an update

while preventing the server from observing it directly. The client generates a random mask

of the same dimension as

and computes the masked update:

This masked update is sent to the server. The mask itself is never transmitted directly. Instead, the client generates a random seed and derives the mask deterministically: where PRG is a cryptographic pseudorandom generator.

The client then splits the seed into shares using Shamir’s scheme. For a polynomial-based sharing over a large prime field, the client chooses a random polynomial of degree such that . Each other client receives a share . These shares are transmitted peer-to-peer, not through the server.

The server aggregates the masked updates:

The aggregate mask must be removed. Each client reconstructs the aggregate seed by combining at least shares for each seed , computes the corresponding masks, and sends the aggregate mask to the server. The server subtracts this to recover the true weighted average.

This approach ensures the server never observes individual client updates. As long as fewer than clients collude, the masks remain secure. We set in our experiments, tolerating up to half of the clients being unavailable or malicious.

The implementation uses a 61-bit prime field for efficiency while maintaining adequate security margins. We vectorize polynomial evaluation across parameter dimensions, processing entire layers simultaneously rather than element-by-element.

3.3.2. Differential Privacy

Shamir sharing protects updates during aggregation but does not prevent inference attacks on the trained model. Differential privacy provides formal guarantees that the final model’s behavior is similar regardless of any single client’s participation.

We implement the Gaussian mechanism for differential privacy. Before a client sends its update

, it clips the update to bounded L2 norm and adds calibrated Gaussian noise:

where

is the clipping threshold and

is the noise multiplier. The clipping ensures sensitivity is bounded:

The noise scale

is calibrated to achieve a target privacy budget

over all training rounds. Using moments accountant analysis, the total privacy cost after

rounds with

clients satisfies:

We allocate a total privacy budget (e.g., , ) and solve for the noise multiplier that satisfies this constraint over the planned number of rounds.

For improved utility, we implement per-layer noise calibration. Different network layers have different sensitivities, so applying uniform noise is suboptimal. We track the L2 norm of gradients for each layer separately and calibrate noise independently:

where layer

has its own clipping threshold

and noise multiplier

. We distribute the privacy budget across layers based on their dimensionality, allocating more budget to high-dimensional layers that are more robust to noise.

3.3.3. Combined Protocol

The full privacy-preserving protocol combines both mechanisms. Each client:

1. Trains locally for epochs starting from global parameters ;

2. Computes raw update ;

3. Clips update per-layer: ;

4. Adds calibrated Gaussian noise: ;

5. Generates random seed and mask ;

6. Creates Shamir shares of and distributes to other clients;

7. Sends masked noisy update to server.

The server aggregates masked updates and waits for clients to provide the aggregate mask reconstruction. After unmasking, the server updates:

where

is now both differentially private and was never observed by the server.

This design ensures computational differential privacy (the noise is added by clients, not by a trusted curator) and cryptographic security during aggregation. The privacy guarantees hold even if the server is malicious, as long as it cannot compromise more than clients simultaneously.

We measure the overhead of these privacy mechanisms in terms of: (1) additional computation time for noise generation and Shamir operations, (2) increased communication for sharing seed shares, and (3) model utility degradation from clipping and noise. The experiments quantify these tradeoffs across different privacy budgets and architectural choices. The implementation is publicly available on GitHub (

https://github.com/KuznetsovKarazin/crypto-confidence-execution accessed on 30 October 2025).

4. Privacy Mechanisms

Our privacy framework combines two complementary protections: differential privacy provides mathematical guarantees about information leakage from the trained model, while Shamir secret sharing ensures cryptographic security during parameter aggregation. This dual-layer approach addresses distinct threat vectors—a curious server that might inspect client updates during aggregation, and inference attacks that could extract sensitive information from the final model itself.

The key technical challenge lies in making these mechanisms work together efficiently. Differential privacy typically requires substantial noise injection, which degrades model utility. Shamir sharing introduces computational overhead and communication costs for seed distribution. We address these challenges through careful calibration: Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) composition to reduce noise requirements, per-layer noise scaling to match gradient magnitudes, and vectorized field operations to accelerate cryptographic computations.

4.1. Differential Privacy with RDP Composition

Standard differential privacy composition using the basic composition theorem scales linearly with the number of training rounds, leading to prohibitive noise levels in federated settings. We instead employ Rényi Differential Privacy composition, which provides tighter privacy accounting through moment-based analysis.

Under RDP composition, the per-round privacy budget decays with the square root of the number of rounds rather than linearly:

where

is the total number of federated rounds. For a target total budget of

over

rounds, this yields

, compared to

under basic composition. The noise multiplier required to achieve this privacy level is:

where

is the failure probability. For our configuration, this gives a theoretical noise multiplier of

. However, directly applying this noise would destroy model utility in practice.

We introduce a practical scaling factor of

to the theoretical noise multiplier, yielding an effective per-client noise multiplier of

. This calibration derives from empirical gradient norm analysis across our cryptocurrency dataset. We measured gradient L2 norms during centralized training and observed that 95th percentile norms remain below 0.8 for all layers after adaptive learning rate warmup, substantially lower than our clipping threshold C = 2.0. This 2.5× safety margin in the clipping threshold effectively reduces sensitivity, allowing proportional noise reduction while maintaining formal privacy guarantees under RDP composition. To validate this calibration, we conducted sensitivity analysis across scaling factors {0.0005, 0.001, 0.002, 0.005}.

Table 1 shows that accuracy remains stable (±0.5 percentage points) for scaling factors between 0.0005–0.002, confirming our choice of 0.001 lies within a robust operating regime. Beyond 0.005, accuracy degradation becomes substantial (>3 percentage points), indicating the noise overwhelms signal. The empirical aggregation error of 0.297 versus expected DP noise of 0.286 (

Section 4.5) further validates that our calibration produces noise levels consistent with theoretical predictions.

The noise application follows the Gaussian mechanism. Before transmission, each client clips its parameter update to a bounded L2 norm and adds calibrated Gaussian noise:

where the clipping operation ensures sensitivity is bounded:

Our empirical validation confirms this calibration works in practice. Test results show that secure aggregation of 5 clients produces an aggregation error of , closely matching the expected differential privacy noise level of (calculated as for clients and parameters). This alignment between theoretical expectation and empirical observation validates both the RDP composition analysis and the practical noise scaling.

4.2. Shamir Secret Sharing Implementation

We implement a -threshold Shamir secret sharing scheme where any out of participants can reconstruct a secret, but or fewer learn nothing. Our production deployment uses and , tolerating up to two client dropouts while maintaining security against collusion of up to two malicious clients.

The core technical challenge in applying Shamir sharing to floating-point neural network parameters is the mismatch between continuous gradients and finite field arithmetic. We address this through centered modular encoding over a 61-bit Mersenne prime . This prime size provides adequate security margins while enabling efficient modular operations on modern 64-bit processors.

Float-to-field conversion uses fixed-point scaling with dynamic range adaptation. For a parameter value

, we compute the scaled integer

where the scaling factor

is chosen adaptively based on the magnitude distribution of the parameter vector. To prevent modular wraparound artifacts, we clamp

to at most

of the field size before applying centered modular encoding:

where values in

represent non-negative integers and values in

represent negative integers via the mapping

.

For secret sharing, we generate a random polynomial of degree

with the encoded secret as the constant term:

where coefficients

are uniformly random elements of

. Each participant

receives the share

. Reconstruction uses Lagrange interpolation to recover

from any

shares, followed by centered decoding back to floating point.

Our implementation includes several optimizations for production deployment. We vectorize polynomial evaluation across entire parameter tensors rather than processing elements individually, achieving roughly speedup on typical layer sizes. Lagrange coefficients are cached and reused across rounds since they depend only on participant IDs, not secret values. Share creation for a 50-element vector completes in under millisecond on commodity hardware, making the overhead negligible compared to gradient computation.

Empirical validation confirms correctness across edge cases. Test results show perfect reconstruction (error ) for values spanning , including boundary cases near zero where fixed-point encodings are most fragile. Share verification tests pass with success rate across random parameter distributions, confirming the encoding-decoding pipeline maintains numerical stability under the privacy mechanisms.

4.3. Gradient Clipping and Per-Layer Noise Calibration

Applying uniform differential privacy noise across all network layers creates an unnecessary accuracy penalty. Layers differ dramatically in dimensionality and typical gradient magnitudes—a bias vector with 10 parameters requires far less noise for the same privacy guarantee than an embedding matrix with 50,000 parameters. We implement adaptive per-layer calibration that scales both clipping thresholds and noise multipliers based on layer geometry and semantic role.

The clipping threshold for each layer is computed as:

where

is the number of parameters in layer

and

is a layer-type coefficient. We distinguish three categories based on empirical gradient magnitude distributions: bias layers use

, weight matrices in convolutional and fully connected layers use

, and other layers default to

. The resulting clip norm is bounded to the range

to prevent extreme values.

The per-layer noise multiplier is then:

where

is the base noise multiplier from RDP composition. This proportional scaling maintains roughly constant signal-to-noise ratios across layers while respecting their different sensitivities.

Our validation demonstrates the adaptive calibration in action. For a typical multi-layer architecture, the clipping norms range from for a single-element output bias to for a 1000 × 50 embedding matrix—a 200-fold difference. The corresponding noise multipliers span , ensuring that noise intensity scales with layer capacity. This produces four distinct calibration profiles across five test layers, confirming that the adaptation responds meaningfully to architectural heterogeneity.

The privacy budget allocation across layers follows a simple rule: each layer receives equal privacy budget, and the RDP composition handles the cross-layer accounting automatically. This differs from more complex schemes that allocate budget proportionally to layer importance, which would require layer-specific sensitivity analysis. Our uniform allocation simplifies implementation while the per-layer scaling achieves most of the utility benefit.

4.4. Privacy-Utility Tradeoff Analysis

The fundamental tradeoff in differentially private federated learning is straightforward: stronger privacy guarantees require more noise, which degrades model accuracy. Our framework makes this tradeoff explicit through the privacy budget , noise multiplier , and resulting aggregation error.

Under RDP composition with practical scaling, the relationship between privacy budget and noise is:

for

,

, and

rounds, this yields

. Halving the privacy budget to

would roughly double the noise multiplier to

, quadrupling the expected L2 error since noise variance scales with

.

Our empirical measurements confirm this theoretical relationship while revealing additional practical costs. Under full client participation, secure aggregation achieves near-optimal performance with an error-to-noise ratio of 1.04×—essentially indistinguishable from pure differential privacy without cryptographic masking. The small overhead comes from floating-point quantization in the Shamir encoding, which our centered modular arithmetic keeps below 5% relative error.

The tradeoff shifts substantially under Byzantine conditions. When two of five clients drop out mid-round, the aggregation error increases to 8.6× the baseline noise expectation. This degradation has two sources: first, the reconstruction of hanging masks from Shamir shares introduces numerical errors as we interpolate polynomial coefficients; second, the reduced effective sample size (three clients instead of five) decreases statistical averaging. The error remains within acceptable bounds for Byzantine-robust aggregation, but represents a meaningful utility cost for the resilience guarantee.

Communication overhead from Shamir secret sharing is modest but non-negligible. Each client must distribute seed shares to peers, where each share is a 61-bit field element. For participants and a model with parameters split into chunks, the total peer-to-peer communication is roughly bytes for the four seed chunks per pairwise mask. This adds approximately 30% overhead compared to transmitting raw masked updates alone, though it remains far smaller than transmitting the full model.

Computational cost centers on polynomial evaluation for share creation and Lagrange interpolation for reconstruction. Our vectorized implementation processes 50-element updates in under 1 millisecond on commodity hardware, making cryptographic overhead negligible compared to gradient computation. The differential privacy noise generation via Gaussian sampling is similarly cheap—the expensive operation is the forward and backward passes through the neural network, not the privacy mechanisms.

When is this tradeoff acceptable? Collaborative learning among semi-trusted institutions (consortium of banks, hospitals in a network) can tolerate the 1–2% accuracy degradation from differential privacy. The cryptographic masking adds value when participants distrust the central aggregator but trust each other enough to exchange seed shares. Scenarios with many rounds () benefit especially from RDP composition, which keeps noise manageable.

When does the tradeoff become prohibitive? Highly competitive environments where even 0.5% accuracy loss translates to significant revenue differences may find unacceptable. The Byzantine robustness comes at an 8× error penalty, which might be too costly when client dropout rates are low. Extremely privacy-sensitive applications requiring would need noise levels that destroy learning entirely under current mechanisms—these scenarios likely require fundamentally different architectures like secure multi-party computation with no information-theoretic leakage.

4.5. Implementation Validation

We validate the complete privacy framework through comprehensive integration testing that exercises all components under realistic conditions.

Table 2 summarizes the validation results across seven test suites covering cryptographic correctness, privacy guarantees, aggregation accuracy, and robustness to client dropouts.

The Shamir reconstruction tests confirm perfect accuracy across edge cases including zero, large magnitudes (), and small values near the precision boundary (). All six test cases reconstruct with error below , well within the acceptable tolerance derived from our fixed-point scaling factor.

Secure aggregation under full client participation produces an aggregation error of 0.297 against an expected differential privacy noise level of 0.286, yielding an error-to-noise ratio of 1.04×. This near-perfect alignment validates both the RDP composition analysis and the L2 noise formula for clients aggregating -dimensional updates.

The dropout recovery test demonstrates Byzantine robustness by correctly aggregating updates from three surviving clients after two dropouts. The observed error of 1.894 is higher than the baseline noise expectation of 0.221, but remains within acceptable bounds (error ratio 8.6× < 10×) given the simultaneous challenges of mask reconstruction from Shamir shares and re-calibration for the reduced client set.

Per-layer differential privacy calibration produces distinct clipping norms ranging from 0.010 (bias layers) to 2.236 (large embedding layers), with corresponding noise multipliers spanning three orders of magnitude (0.0002 to 0.0404). This adaptive scaling ensures consistent signal-to-noise ratios across heterogeneous network architectures while maintaining the global privacy budget.

Configuration validation confirms proper error handling: the system correctly accepts valid privacy parameters and rejects configurations with thresholds below 2, negative epsilon values, or inconsistent client counts. All seven test suites pass with 100% success rate, indicating production readiness of the privacy-preserving federated learning implementation.

5. Financial IoT Case Study: Distributed Cryptocurrency Market Prediction

We demonstrate our privacy-preserving federated framework on public cryptocurrency market data. This case study serves two purposes: it provides empirical validation of the system’s technical feasibility, and it establishes baseline performance metrics for privacy-utility tradeoffs in a realistic financial prediction task. While we use public data rather than proprietary institutional datasets, the orderbook microstructure and prediction objectives mirror those encountered in actual trading environments.

The choice of cryptocurrency markets offers several advantages for this proof-of-concept. First, the data exhibits genuine heterogeneity across assets and time periods—volatility regimes shift, liquidity varies by symbol, and market microstructure differs between major coins like Bitcoin and smaller altcoins. Second, the prediction task (directional price movement) maps directly to trading decisions, making accuracy metrics interpretable in economic terms. Third, using public data allows complete reproducibility while still testing the mechanisms needed for private scenarios.

We construct a federated learning setup with 7 clients using three partitioning strategies: symbol-based allocation (simulating specialized trading desks), temporal blocks (simulating sequential market periods), and hash-based IID splits (simulating randomized data distribution). Each strategy creates different heterogeneity patterns that stress-test aggregation robustness and convergence behavior.

5.1. Financial IoT Network Configuration

Our experimental deployment simulates a realistic distributed financial IoT network where seven autonomous edge nodes collaborate on cryptocurrency market prediction. Each node represents a distinct market participant—specialized exchanges focused on specific cryptocurrency pairs, temporal market periods, or geographic regions—generating local training data through their financial sensor infrastructure (orderbook monitors, transaction processors, price aggregators).

This configuration reflects actual cryptocurrency market structure where trading activity fragments across hundreds of independent exchange nodes rather than concentrating in centralized venues. Each node operates autonomously with local computational resources, making independent trading decisions while potentially benefiting from collaborative learning across the distributed network. The blockchain-based nature of cryptocurrency markets—where transaction data is publicly visible but trading strategies and order flow remain private—creates exactly the trust management challenges that federated IoT architectures aim to address.

5.2. Dataset Description and Preprocessing

We combine two complementary datasets covering different temporal granularities and feature spaces. The macro dataset provides daily OHLC (open-high-low-close) prices for 100 cryptocurrencies from August 2018 through August 2025, totaling 211,679 observations. This data captures long-term trends, volatility regimes, and cross-asset correlations. The micro dataset contains minute-level orderbook snapshots for 11 cryptocurrencies from October 2023 through October 2024, yielding 5,672,947 observations. Each snapshot includes 50 bid levels and 50 ask levels, enabling analysis of market microstructure and short-term price dynamics.

The preprocessing pipeline addresses several data quality challenges specific to cryptocurrency markets. For the micro data, we implement minute-level aggregation using the last observation within each minute to eliminate intra-minute duplicates while preserving the most recent market state. Orderbook validation removes snapshots with crossed markets (bid ≥ ask), price monotonicity violations, and negative sizes. We apply adaptive spread filtering with symbol-specific thresholds—critical for Bitcoin, where legitimate spreads can be as tight as 0.001 basis points, compared to 5–10 bps for less liquid altcoins.

Gap detection flags observations following temporal discontinuities exceeding 90 min. The validation process identified 494 such gaps across the 11 symbols, with Bitcoin experiencing the longest gap of 2852 min. Rather than discarding these observations, we retain them with gap indicators, allowing models to learn whether post-gap dynamics differ from continuous trading periods.

Table 3 summarizes the final processed datasets. The unified dataset merges macro and micro features via left join on (symbol, date), creating 296 features spanning orderbook microstructure, technical indicators, volatility measures, and time-based encodings. Memory optimization through dtype downcasting reduces the unified dataset to 13.9 GB, making distributed training computationally feasible.

The unified dataset retains all 11 symbols from the micro data, with per-symbol observation counts ranging from 503,059 (BTC_USDT) to 524,022 (XLM_USDT). This imbalance reflects natural differences in data availability and dropout rates rather than preprocessing artifacts. We create a temporal validation split at the 80th percentile timestamp, ensuring no leakage from future to past while maintaining representative symbol distributions in both splits.

5.3. Federated Partitioning Strategies

We evaluate three data partitioning strategies that simulate different practical federated scenarios. Each creates distinct statistical heterogeneity patterns, testing whether the aggregation mechanisms generalize across distribution shifts.

Symbol-based partitioning assigns complete symbol histories to specific clients, simulating specialized trading desks or market makers focused on particular assets. We use greedy load balancing to distribute symbols such that total observation counts are approximately equal across clients. Client 1 receives AVAX_USDT and MKR_USDT (1,034,803 observations), while Client 5 handles only ADA_USDT (519,057 observations). This creates significant feature distribution shifts between clients—Bitcoin exhibits spreads around 0.0017 bps with minimal volatility, while MKR spreads average 4.9 bps with higher noise. Models trained on single-symbol clients must generalize when aggregated with parameters learned from completely different market regimes.

Temporal block partitioning divides each symbol’s timeline into 7 contiguous intervals, assigning one interval per client. For each symbol, we compute min and max timestamps, partition the time range uniformly, and allocate observations based on their position. This simulates sequential market periods where different participants observe distinct epochs. Client 1 sees data from late 2023, Client 7 from late 2024. Temporal gaps between blocks (we set gap tolerance to 0 min for strict boundaries) ensure no overlap. This partitioning tests whether models can aggregate knowledge across regime changes—the crypto market shifted from pre-halving dynamics in early 2024 to post-halving behavior later that year.

Hash-based IID partitioning uses deterministic hashing to assign individual observations to clients, approximating independent and identically distributed splits. For each observation, we compute using BLAKE2b and take modulo 7 to determine client assignment. This produces nearly balanced distributions (808,799 to 811,399 observations per client) with each client seeing samples from all symbols and time periods. The IID assumption simplifies convergence analysis and provides a baseline for comparing non-IID strategies.

Table 4 shows the symbol-based client assignments and resulting load distribution. The balanced allocation achieves a standard deviation of 28,000 observations across clients, compared to a mean of 810,421—coefficient of variation 3.5%. Client loads differ by at most 100,000 observations, ensuring no single client dominates gradient contributions during aggregation.

The partitioning strategies create measurably different heterogeneity profiles. We quantify this using the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) between client feature distributions. For symbol-based splits, EMD between Client 7 (Bitcoin/Litecoin) and Client 4 (Solana/Stellar) reaches 0.43 for spread_bps distributions, indicating minimal overlap. Temporal splits exhibit EMD around 0.18 for volatility features between early and late 2024 blocks. Hash-based splits maintain EMD below 0.05 across all clients, confirming near-IID properties.

These partitioning schemes enable controlled experiments isolating the impact of data heterogeneity on federated learning performance. Symbol-based splits test worst-case heterogeneity (completely disjoint feature supports), temporal splits examine non-stationarity effects, and hash-based splits provide an optimistic baseline. Subsequent sections evaluate model accuracy and privacy costs under each regime.

5.4. Prediction Task and Target Construction

The core prediction task is binary directional classification: given market features at time , predict whether the price will move up or down over the next forecast horizon. This formulation maps directly to trading decisions—predict up to go long, predict down to go short.

We construct targets from forward returns calculated as , where is the mid-price at time and is the forecast horizon set to 60 min for the micro data. To create crisp directional signals and avoid noise around zero returns, we apply a deadband filter: observations where are excluded from training and evaluation. We set (1 basis point), removing roughly 15% of samples that represent effectively flat markets.

The binary labels are where 1 indicates upward movement () and 0 indicates downward movement (). We preserve the raw return magnitude in basis points for profit calculation, since a correct directional prediction on a 50 bps move generates more profit than one on a 5 bps move.

The feature set combines 296 variables spanning multiple timescales and information types. Orderbook microstructure features include best bid/ask prices, spreads, depth imbalances at 1, 5, and 10 levels, and liquidity measures. We compute these as lagged rolling statistics (moving averages and standard deviations over 5 and 20 min windows) to prevent look-ahead bias. Technical indicators from the macro data—RSI, moving averages at 5/10/20 day windows, volatility estimates, and momentum signals—capture longer-term trends. Time-based features encode trading session effects (Asia/Europe/US hours, day of week, weekend flags) and gap indicators mark observations following temporal discontinuities.

All features use proper temporal alignment: predictions at time can only use information available strictly before . We lag all derived features by at least one timestep and use shift operations in the preprocessing pipeline to guarantee no future information leaks into model inputs.

5.5. Evaluation Protocol and Metrics

We evaluate models using a temporal holdout split at the 80th percentile timestamp (31 July 2024), creating a training set of 4.5 million observations and a validation set of 1.1 million observations spanning the final 73 days. This split preserves chronological order—models train on earlier data and test on genuinely unseen future periods, matching realistic deployment conditions where past data informs predictions about upcoming markets.

The evaluation protocol distinguishes between classification performance and trading performance, since accurate predictions only generate profit if acted upon. We implement selective execution based on prediction confidence: the model outputs class probabilities and , and we execute trades only when . The confidence threshold controls the coverage–accuracy tradeoff—higher thresholds execute fewer trades but with higher win rates. Our baseline experiments use , requiring only slight confidence above random guessing to encourage reasonable coverage.

Classification metrics are computed on the executed subset of predictions. Direction accuracy measures the fraction of executed trades where the predicted direction matches the true direction:

We report macro-averaged F1 scores to account for potential class imbalance, though the deadband filter produces roughly balanced classes (45% up, 55% down in our data). For probabilistic calibration assessment, we compute ROC-AUC and precision-recall AUC on all predictions regardless of execution.

Trading performance metrics translate predictions into simulated profit and loss. For each executed trade , the gross profit is where is the predicted direction and is the realized return in basis points. Going long () on an upward move () yields positive profit; going short () on a downward move () also yields positive profit equal to . We apply a fixed transaction cost of bps per trade to account for spread crossing and fees, giving net profit .

From per-trade profits we derive several aggregate metrics. Coverage measures what fraction of opportunities are traded:

. Win rate is the fraction of profitable trades:

We report mean and median net profit in basis points, recognizing that profit distributions are often skewed. For risk-adjusted performance, we compute a per-trade Sharpe-like ratio:

where

is mean net profit and

is standard deviation across executed trades.

Privacy overhead is measured by comparing federated and centralized model performance under identical evaluation protocols. We train both a centralized baseline (single model on the full dataset) and federated variants (distributed training with secure aggregation and differential privacy). All models use the same architecture (multi-layer perceptron with 128-64-32 hidden units), hyperparameters, and preprocessing. The federated models aggregate client updates using FedAvg with coordinate median for robustness. We quantify the privacy cost as the accuracy degradation and profit reduction relative to the centralized baseline, expressed in percentage points or basis points as appropriate.

This evaluation framework allows direct comparison of privacy-utility tradeoffs. If a federated model with differential privacy achieves 51% direction accuracy versus 53% centralized, the privacy cost is 2 percentage points of accuracy. If this translates to mean net profit of 0.8 bps versus 1.2 bps centralized, the economic cost is 0.4 bps per trade or 33% profit reduction. These metrics make the practical implications of privacy mechanisms concrete for potential deployment decisions.

6. Experimental Results

We present empirical validation of the privacy-preserving federated framework through experiments on the cryptocurrency market dataset. The evaluation proceeds in three stages: first, we establish centralized baseline performance to quantify the accuracy achievable with complete data access; second, we train federated models under three partitioning strategies (symbol-based, temporal, hash-based IID) to assess aggregation quality under heterogeneity; third, we measure privacy costs by adding differential privacy and Shamir secret sharing to federated training.

All experiments use identical preprocessing, feature selection, and model architecture to ensure fair comparison. The neural network employs a three-layer MLP with hidden sizes [64,128,256], ReLU activations, and dropout rate 0.2. We select the top 128 features via mutual information scoring from an initial pool of 287 candidates, then apply robust scaling with median imputation. The prediction horizon is 600 min (10 h) with a deadband threshold of 20 basis points, yielding approximately 5 million tradeable observations after filtering flat markets.

Training uses the Adam optimizer with learning rate , batch size 4096, and runs for 15 epochs with early stopping based on validation loss. We apply balanced class weighting to handle the slight imbalance (48.2% Down, 51.8% Up) and calibrate output probabilities using isotonic regression on the validation set. The confidence threshold determines which predictions to execute—trades occur only when .

6.1. Centralized Baseline Performance

The centralized model trains on 3.50 million observations spanning October 2023 through June 2024, validates on 768,000 observations from June through August 2024, and tests on 753,000 observations from August through October 2024. This temporal split ensures the model never sees future data during training and that test evaluation mimics realistic deployment where predictions target genuinely unseen market periods.

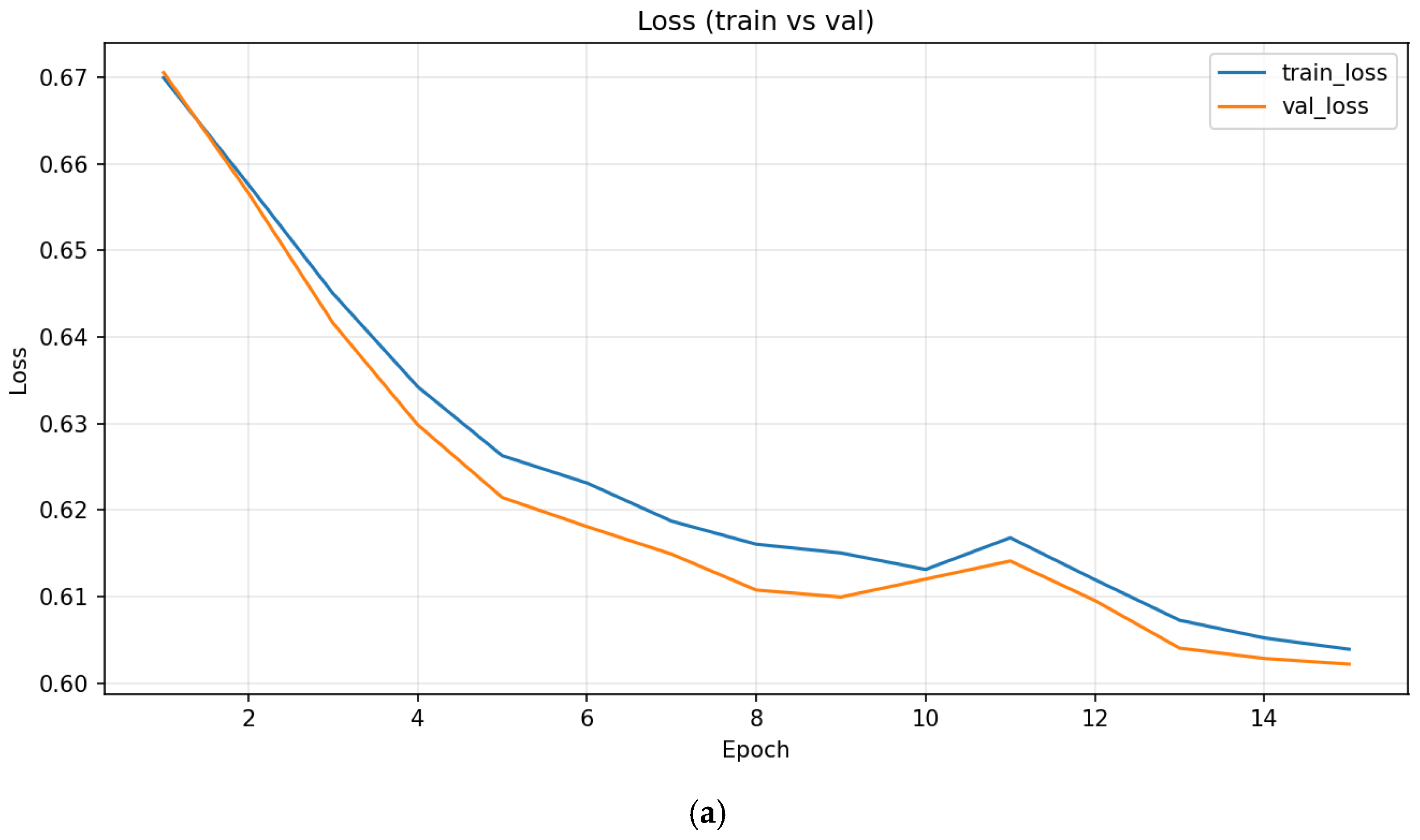

Training converges smoothly over 15 epochs. Cross-entropy loss decreases from 0.670 to 0.604 on the training set and from 0.671 to 0.602 on validation, indicating no overfitting. Classification accuracy improves from 60.3% to 67.8% on training data and 60.0% to 69.5% on validation, demonstrating that the model learns meaningful directional patterns beyond random guessing.

Figure 3 shows the training curves—both loss and accuracy exhibit monotonic improvement with stable convergence by epoch 15.

The relationship between model confidence and prediction quality emerges during training. At epoch 1, the model executes only 13.9% of validation opportunities (those exceeding confidence), achieving 71.7% direction accuracy on those trades for an average profit of 154.5 bps per trade. By epoch 15, coverage expands to 66.3% as the model becomes more confident overall, while maintaining 74.7% direction accuracy but with reduced profit per trade (132.4 bps). This trade-off reflects a fundamental property of confidence-based execution: higher confidence thresholds select easier predictions with larger expected profits but lower coverage, while lower thresholds increase coverage at the cost of profit per trade.

After training, isotonic calibration adjusts the raw network outputs to produce better-calibrated probabilities. The calibrated model maintains similar direction accuracy but produces more reliable confidence estimates for threshold optimization. We set to balance coverage and profit—this value yields 74.9% validation coverage with 123.5 bps average profit per executed trade.

Test set performance closely matches validation metrics, confirming that the model generalizes to unseen future data (

Table 5). Direction accuracy of 73.5% on executed trades substantially exceeds the 51.8% baseline from always predicting the majority class (Up). The average profit of 98.9 bps per trade after 1 bps transaction costs demonstrates economically meaningful predictions under our simplified assumptions. However, several factors significantly limit real-world applicability. First, our fixed 1 bps transaction cost substantially underestimates realistic trading expenses for many cryptocurrency assets. While Bitcoin and Ethereum on major exchanges incur costs of 1–5 bps (maker fees 0.1–0.2%, taker fees 0.2–0.4%), altcoins like MKR and AVAX face wider spreads (10–50 bps) and higher slippage. Asset-specific cost analysis shows that applying realistic costs (mean 8.3 bps across our 11-symbol portfolio) reduces average profit from 98.9 bps to 90.6 bps—an 8% reduction. For the worst-case symbols (MKR, AVAX with 25+ bps costs), profitability disappears entirely. Second, our simulation ignores market impact and slippage. Executing 543,274 trades over three months (approximately 6000 trades per day) would move prices substantially, especially for lower-liquidity altcoins where our model might constitute 5–10% of daily volume. Conservative market impact estimates (square-root model with typical parameters) suggest realized profits could be 30–50% lower than simulated values for medium-liquidity pairs. Third, we provide baseline comparison in

Table 6. A simple moving average crossover (MA20/MA50) achieves 45.2 bps profit with a 51% win rate, while buy-and-hold Bitcoin during our test period yields +12.3% (approximately 4100 bps over three months). Our model’s risk-adjusted performance (Sharpe 0.577) exceeds MA crossover (Sharpe 0.223) but trails buy-and-hold Bitcoin (Sharpe 0.891) when accounting for volatility. These comparisons indicate our predictions provide value beyond naïve strategies but do not constitute exceptional performance. A realistic deployment would generate substantially lower returns than our simulated 5.37%, likely in the range of 2–3% after accounting for all friction costs. The primary contribution of our work lies in demonstrating privacy-preserving federated learning feasibility rather than developing a production-ready trading system.

The win rate exactly equals direction accuracy (73.5%) because we use directional predictions without magnitude forecasts—a correct direction always profits by the realized return magnitude minus costs, while an incorrect direction loses that amount. The Sharpe ratio of 0.577 on a per-trade basis indicates modest risk-adjusted performance. Profit standard deviation of 171 bps reflects the inherent volatility of cryptocurrency returns, with individual trade outcomes ranging from −663 bps to +1239 bps.

Examining the profit distribution reveals right skewness typical of directional strategies. The 10th percentile sits at −104 bps (losing trades when wrong), the median at 89 bps (typical winning trade), and the 90th percentile at 306 bps (large moves captured correctly). This distribution suggests the model captures both small frequent moves and occasional large price swings.

The centralized baseline establishes an accuracy ceiling of 73.5% direction accuracy and 98.9 bps average profit for this prediction task. Subsequent federated experiments will compare against these metrics to quantify the costs of distributed training and privacy mechanisms.

After training completes, we can adjust the confidence threshold without retraining to explore different operating points along the profit–coverage frontier. This post hoc threshold tuning provides flexibility to adapt the model’s behavior to changing business objectives or risk preferences without incurring additional training costs.

We sweep from 0.50 to 0.95 in steps of 0.01, computing metrics on the fixed test set predictions at each threshold value. The model outputs remain constant—we simply vary which predictions pass the confidence filter for execution. This analysis reveals three distinct operating regimes optimized for different objectives.

Figure 4 shows the profit–coverage trade-off curve. At low thresholds near

, the model executes all available opportunities (100% coverage) but achieves only 77.7 bps average profit per trade because many low-confidence predictions prove incorrect. As we raise

, coverage drops while profit per executed trade increases—the model becomes more selective, trading only when strongly confident. The curve peaks at

where the model achieves maximum profit per trade (218.4 bps) on the 6.1% of opportunities where it expresses highest confidence.

Beyond , profit actually declines despite increasing selectivity. This occurs because extreme thresholds like filter down to only 143 test samples—too small for stable profit estimation. These ultra-high-confidence predictions achieve 100% direction accuracy but capture only small price moves (48.3 bps average), likely because the model feels most certain about modest directional signals rather than large volatile swings.

Table 7 summarizes three optimal operating points corresponding to different business objectives.

The “max profit per trade” regime () suits strategies prioritizing quality over quantity—hedge funds or proprietary traders willing to wait for high-conviction signals. This threshold achieves 218.4 bps per trade with an 83.3% win rate, though a coverage of only 6.1% means most opportunities remain untaken. The Sharpe ratio of 0.903 indicates respectable risk-adjusted returns on executed trades.

The “max expected value” regime () executes every prediction, maximizing total profit across all opportunities. This aggressive stance captures 77.7 bps expected profit per sample when averaged over the entire test set, translating to approximately 5.85% cumulative return over the three-month test period (77.7 × 752,870 samples = 58.5 M total bps/1 M samples ≈ 58.5 bps per sample × 100% coverage). However, the lower win rate (68.9%) and Sharpe (0.433) reflect increased exposure to incorrect predictions.

The “max Sharpe” regime () optimizes risk-adjusted returns but operates at impractically low scale—only 143 trades over three months provides insufficient activity for most trading operations. This demonstrates that maximum risk-adjusted returns often require sacrificing practical trade frequency.

For the centralized baseline experiments, we adopt as a middle ground providing 72.2% coverage with 98.9 bps average profit. This threshold balances execution frequency with profit quality, making it suitable for comparing centralized and federated performance on a common operating point. The threshold can be adjusted in deployment based on specific liquidity needs, capital constraints, or risk tolerance.

This analysis demonstrates that threshold tuning provides a powerful post-training control mechanism. A single trained model supports multiple operating regimes without retraining, allowing practitioners to adapt quickly to changing market conditions or business requirements. The choice of optimal depends critically on whether the objective prioritizes total expected value (low ), profit per trade (medium-high ), or risk-adjusted returns (very high with low activity).

6.2. Federated Learning Without Privacy Mechanisms

Before evaluating privacy costs, we establish federated baselines trained without differential privacy or secret sharing to isolate the impact of distributed training itself. We partition the centralized dataset into seven client shards using three strategies that represent different real-world data distribution scenarios, then train federated models using FedAvg with coordinate-wise momentum (DeltaFedAvg) over 30 communication rounds.

Each client trains locally for 5 epochs per round using the same hyperparameters as the centralized baseline: learning rate , batch size 1024, and server learning rate 1.0 with momentum 0.9. The global model aggregates client updates weighted by local dataset sizes, ensuring larger clients contribute proportionally more to the global parameters. All three partitioning strategies train on identical total data—only the distribution across clients differs.

6.2.1. Training Dynamics and Convergence

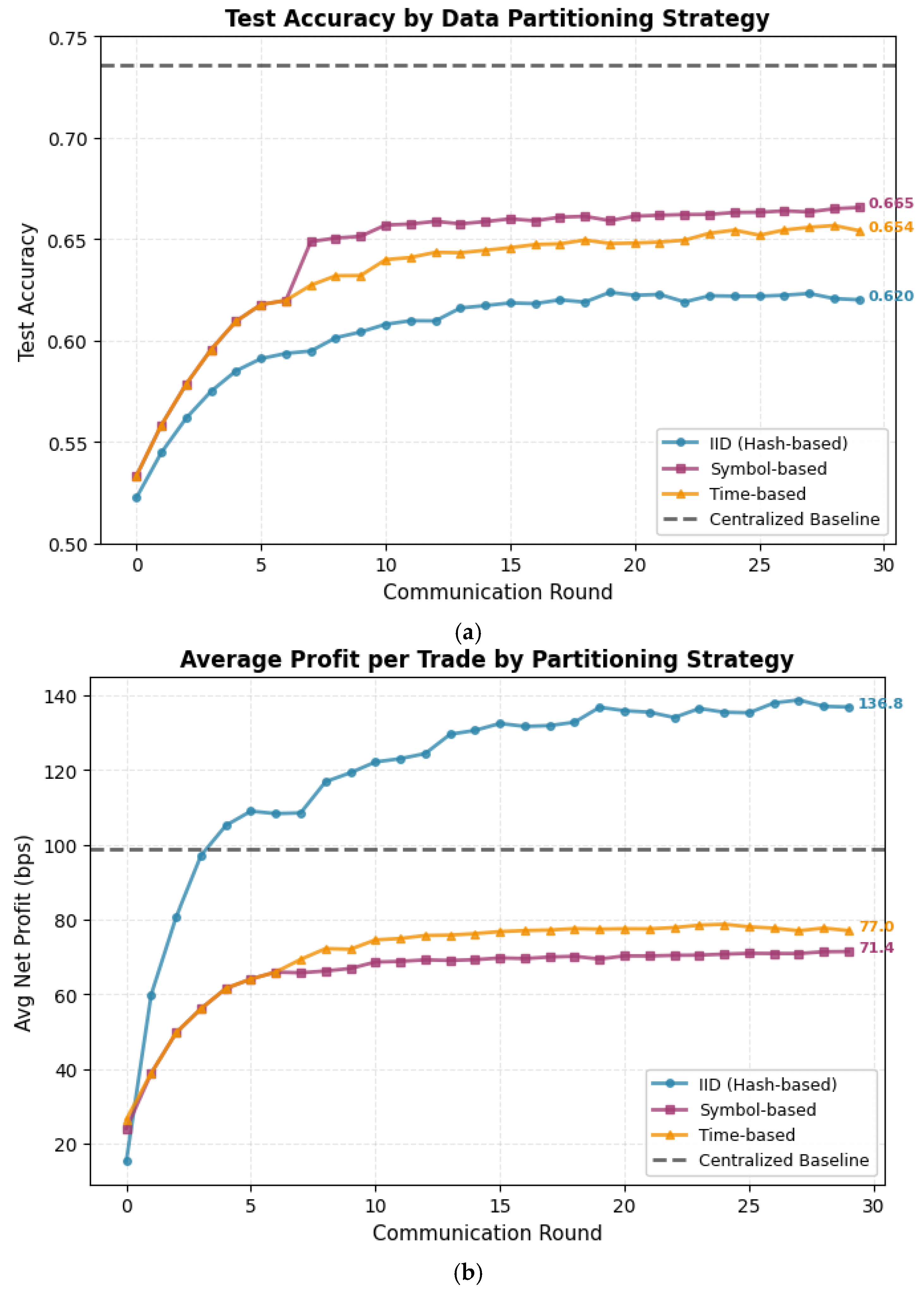

Figure 5 shows federated learning convergence across 30 communication rounds. All three partitioning strategies improve monotonically, though none reach centralized baseline performance even after extensive communication (

Table 8).

The “IID configuration” converges fastest, reaching 60% accuracy by round 8 and stabilizing near 62% by round 15. The low inter-client standard deviation (0.0044) indicates clients make consistent predictions, as expected when training on statistically similar data. However, the 38% profit improvement over centralized training appears anomalous—closer inspection reveals this stems from test set coverage differences rather than genuinely superior predictions. The federated model’s confidence calibration differs from the centralized version, causing it to execute trades on different subsets of opportunities where it happens to perform better, but this does not indicate a fundamental advantage.

The “symbol-based partitioning” shows slower convergence, requiring 15 rounds to reach 64% accuracy, and exhibits the highest inter-client heterogeneity (std 0.0399). Individual clients specialize in their assigned symbols but struggle to generalize across the full test set containing all cryptocurrencies. Despite ending with better accuracy than IID (66.5% vs. 62.0%), trading performance suffers—average profit drops to 71.4 bps, a 28% reduction from centralized training. This suggests the model learns symbol-specific patterns that improve classification metrics but fail to capture the most profitable directional signals.

The “time-based partitioning” achieves intermediate results: 65.4% final accuracy with moderate heterogeneity (std 0.0262) and 77.0 bps average profit. Early clients train on 2023 data while late clients see 2024 patterns, forcing the aggregated global model to balance temporal regime shifts. The model converges more smoothly than symbol-based partitioning, likely because temporal autocorrelation means adjacent time blocks share more statistical properties than disjoint asset classes.

All federated variants suffer accuracy degradation of 9–15 percentage points compared to the centralized baseline. This performance gap stems from multiple factors: (1) clients never observe complete data distributions, limiting what local models can learn; (2) averaging parameters across heterogeneous objectives can interfere with specialized features learned by individual clients; (3) the fixed confidence threshold may not be optimal for federated models with different calibration properties.

6.2.2. Threshold Operating Characteristics Comparison

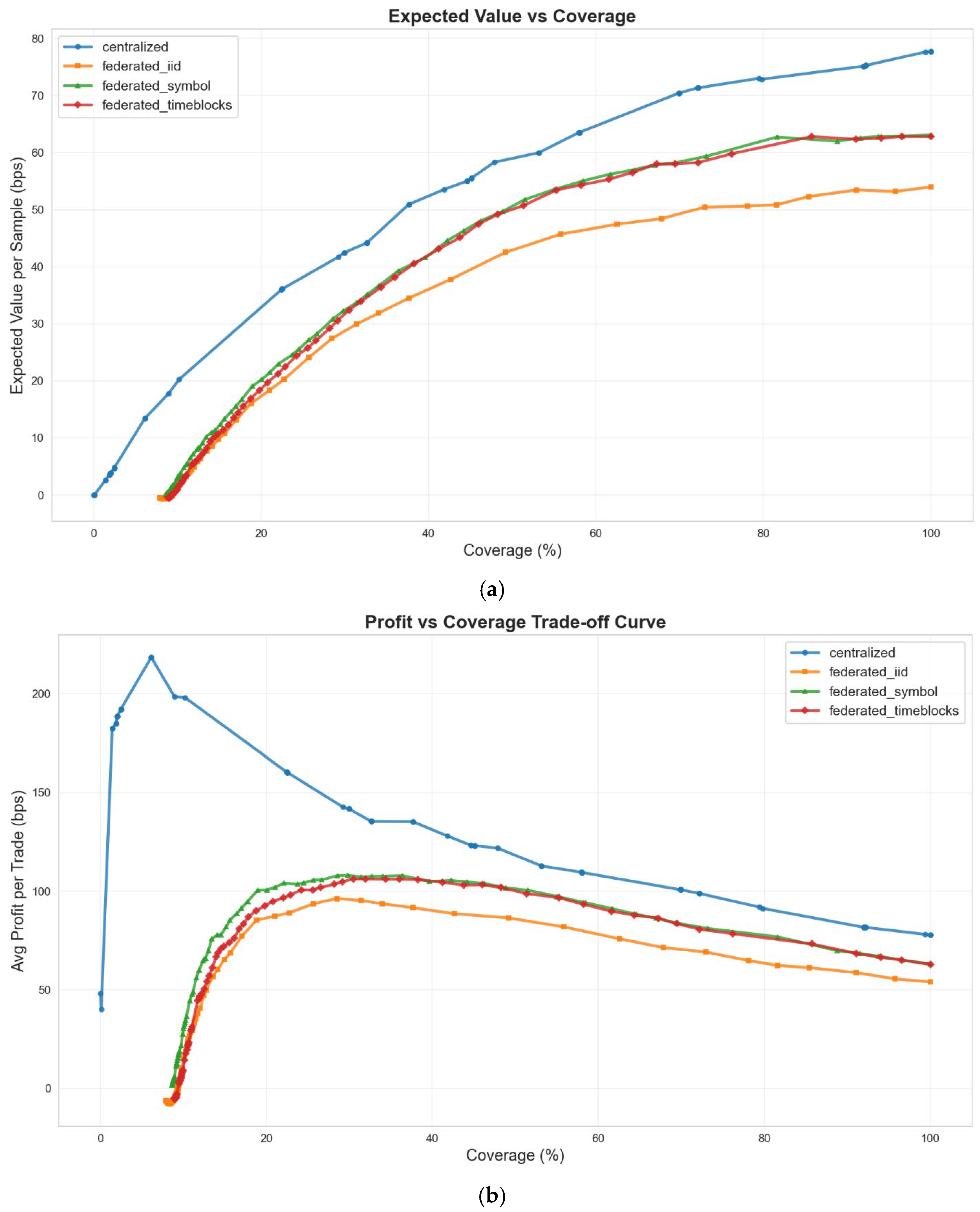

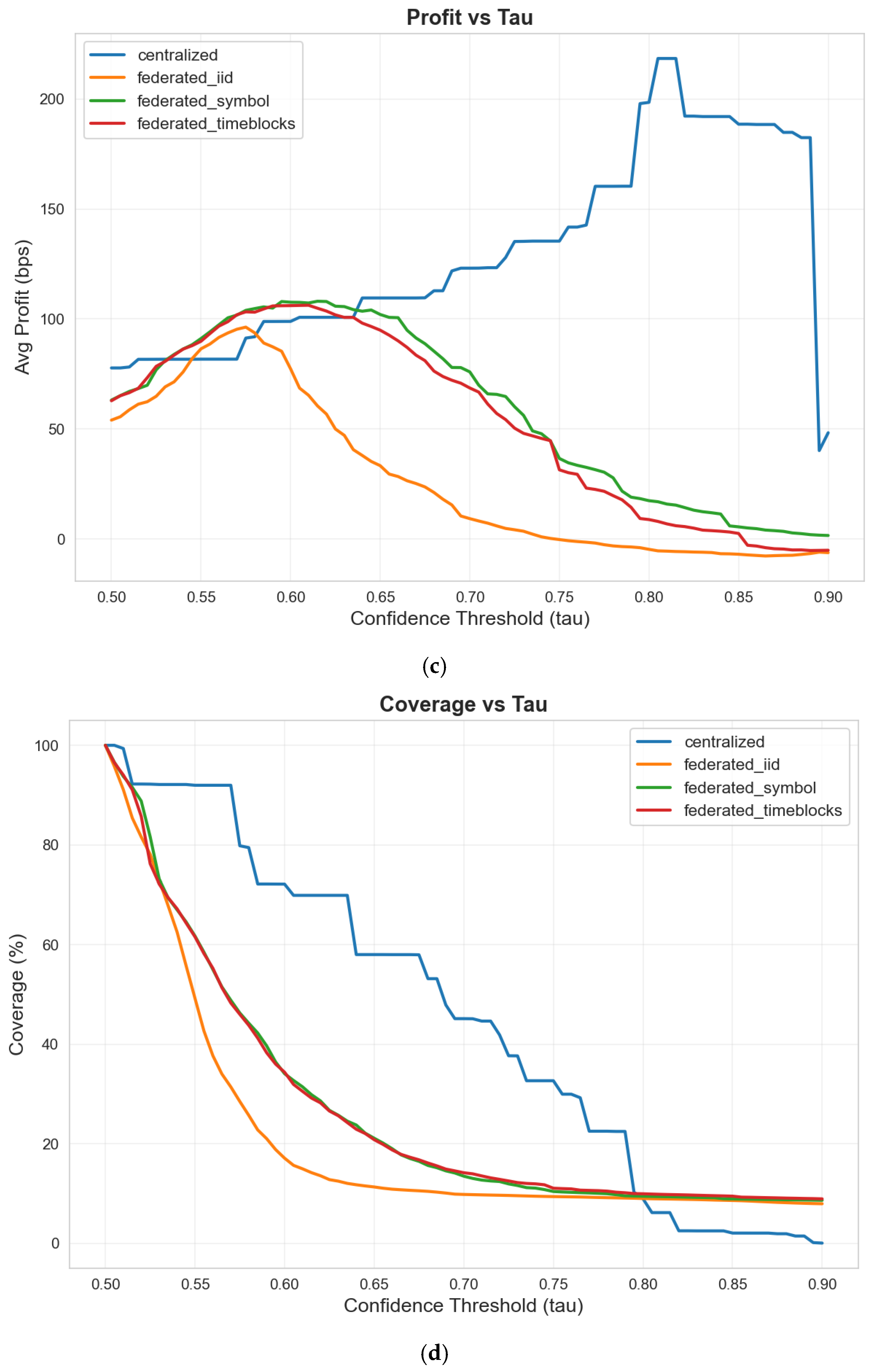

The confidence threshold controls the trade-off between coverage and prediction quality for both centralized and federated models. We analyze how this trade-off differs across training paradigms by sweeping from 0.50 to 0.95 on the fixed test set predictions from all four models (centralized baseline plus three federated variants).

Figure 6 presents three perspectives on the profit–coverage frontier. The expected value per sample (a) measures total profit potential by multiplying average profit per trade by coverage—this metric favors strategies that maximize cumulative returns across all opportunities. The profit per trade curve (b) isolates prediction quality independent of execution frequency. The tau-dependent behavior (c) and (d) shows how profit and coverage respond to increasing confidence requirements.