Exploring Determinants of Information Security Systems Adoption in Saudi Arabian SMEs: An Integrated Multitheoretical Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Development of an Integrated Research Model

2.1. InfoSec Systems in SMEs

2.2. Adoption of InfoSec System

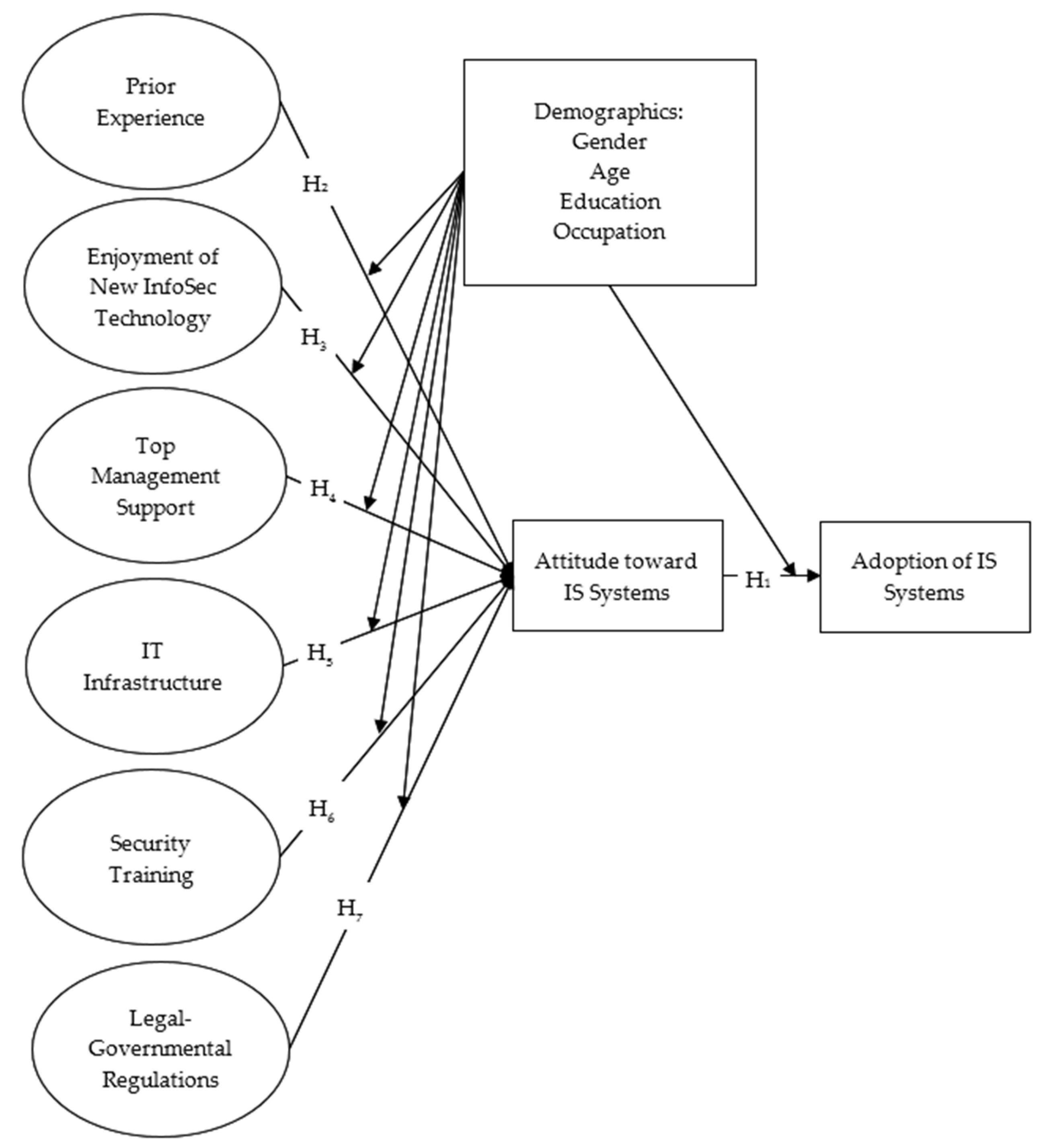

2.3. Theoretical Framework and Development of the Integrated Model Adoption of InfoSec Systems

2.4. From Attitude Towards InfoSec Systems to Adoption of InfoSec Systems

2.5. Determinants Influencing Attitudes Toward InfoSec Systems

2.5.1. Prior Experience

2.5.2. Enjoyment of New InfoSec Technology

2.5.3. Top Management Support

2.5.4. IT Infrastructure

2.5.5. Security Training

2.5.6. Legal-Governmental Regulations

2.5.7. Mediating Role of Attitude

2.5.8. Moderation of Demographic Variables in Determinants Influencing Attitude Towards and Adoption of InfoSec Systems

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Sample Size Estimation

3.4. Setting

3.5. Research Instruments

3.6. Statistical Analysis

3.7. Ethical Consideration

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.4. Pearson’s Correlation Analysis

4.5. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.6. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4.7. Path Analysis

4.8. Mediation Analysis

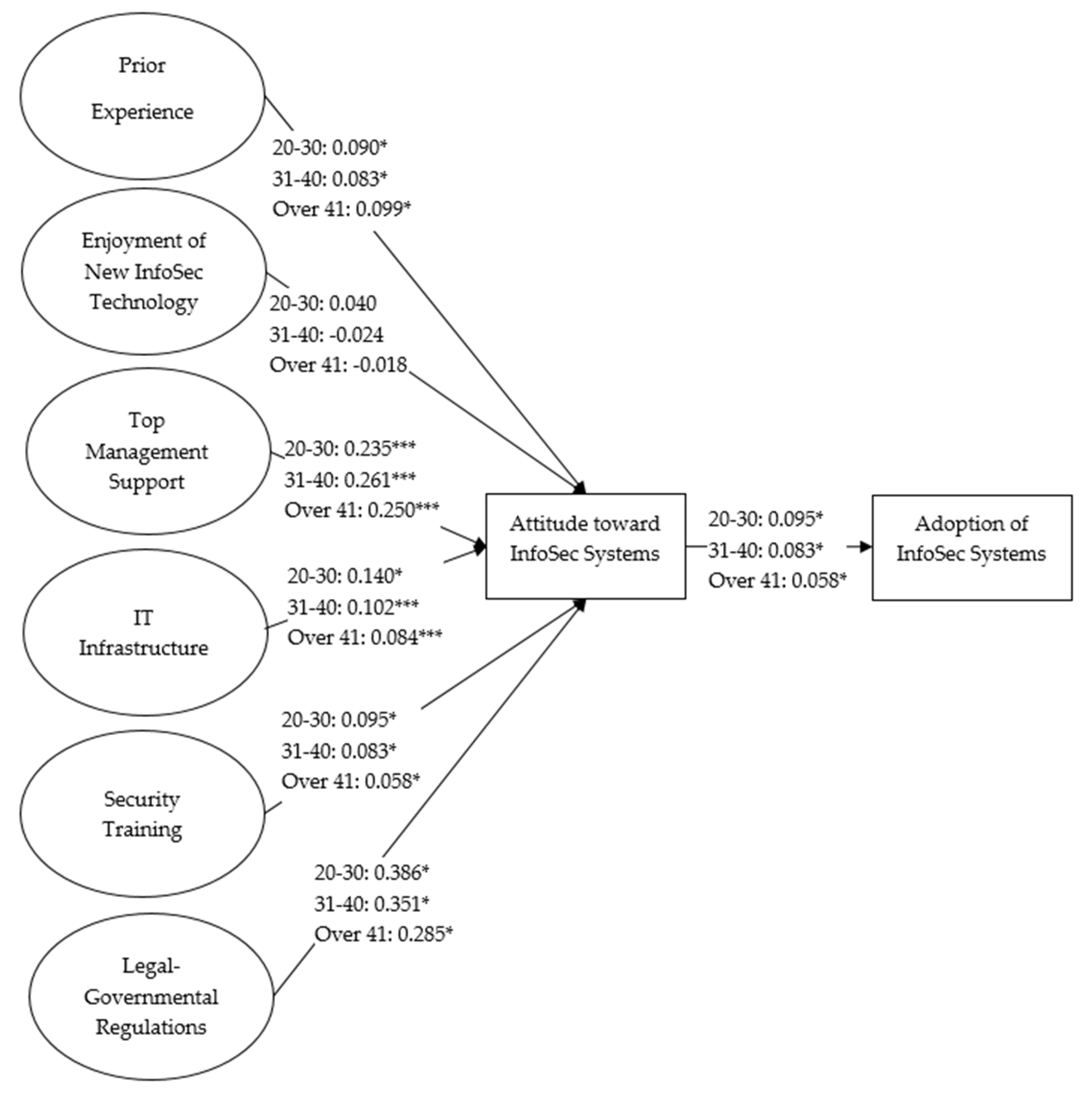

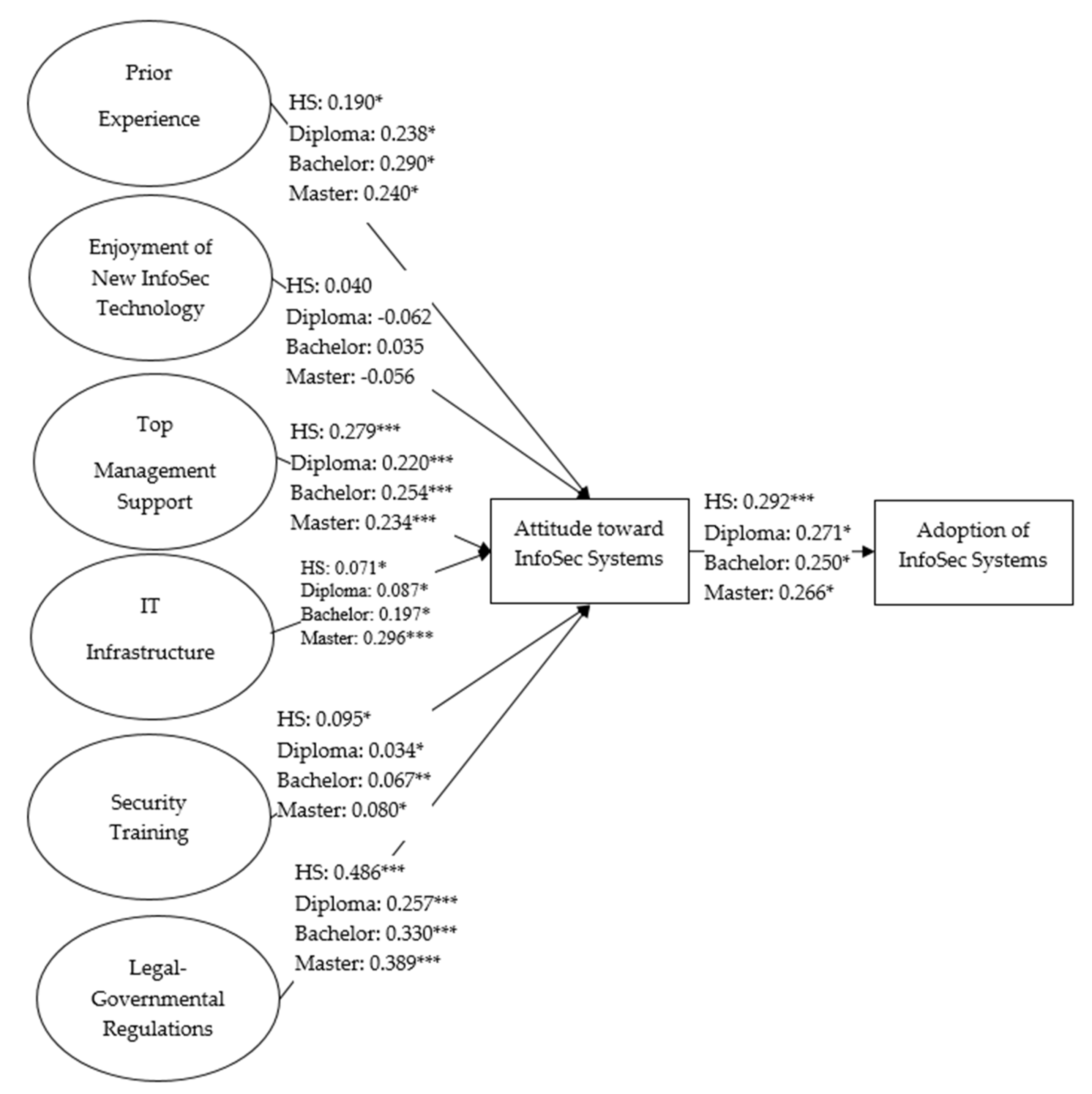

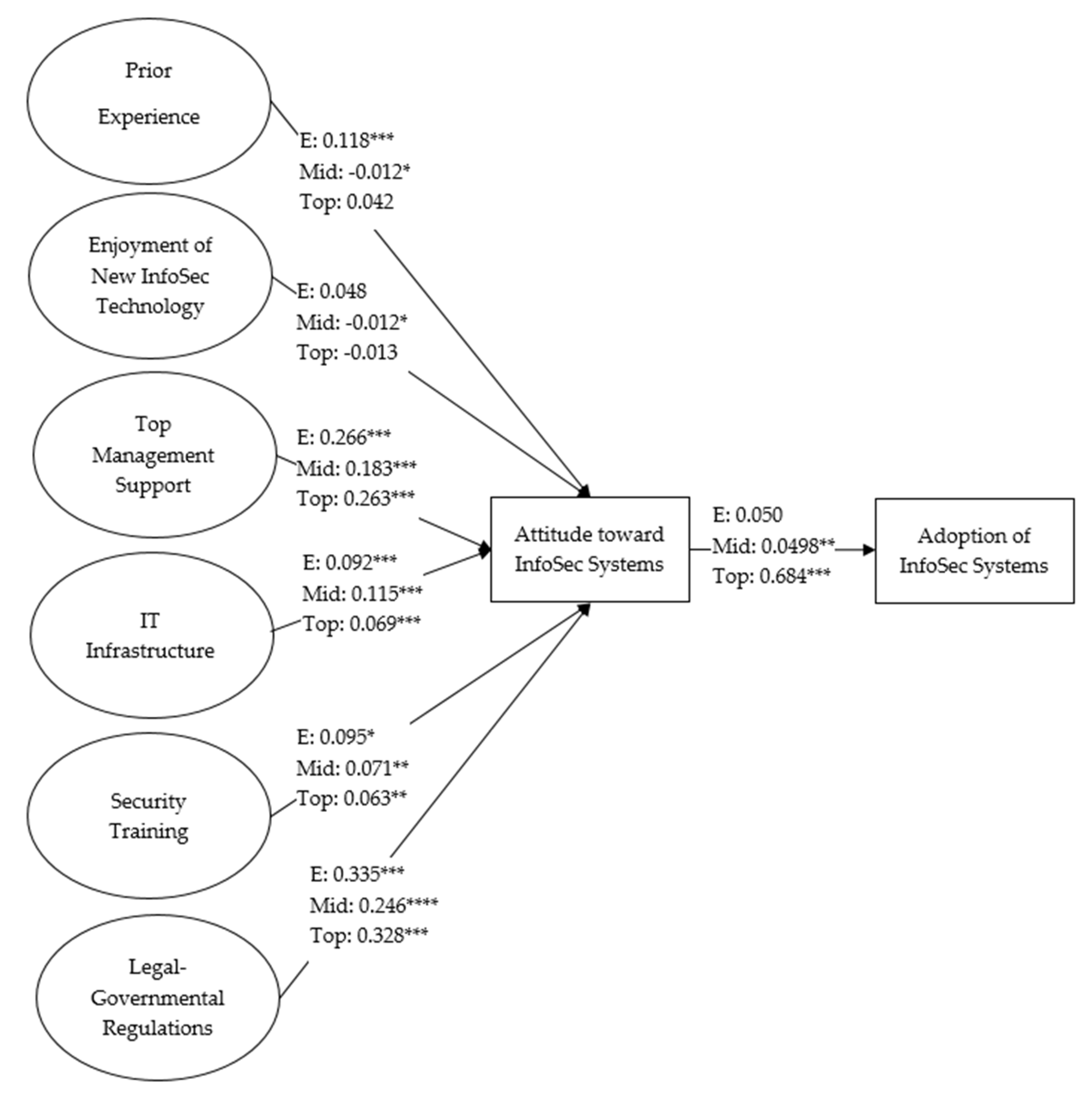

4.9. Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings

5.2. Key Theoretical Implications

5.3. Key Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| InfoSec | Information Security |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| IT | Information Technology |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| TRA | Theory of Reasoned Action |

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Construct | Item | Question | Adapted From |

| Prior Experience | PE.1 | In my prior work, I learnt how to implement InfoSec security procedures. | [20,119] |

| PE.2 | I acquired from my training how to adopt the InfoSec system. | ||

| PE.3 | I learned to use the InfoSec system in my prior job. | ||

| PE.4 | I have had prior experience with similar systems. | ||

| PE.5 | I am already acquainted with similar systems. | ||

| Enjoyment of New InfoSec Technology | ENJ.1 | I believe complying with InfoSec policies is enjoyable. | [120,121,122,123,124] |

| ENJ.2 | I believe the process of daily practicing security measures is pleasant. | ||

| ENJ.3 | I believe that while I implement InfoSec procedures, I enjoy the process. | ||

| ENJ.4 | I believe adopting InfoSec systems is convenient. | ||

| ENJ.5 | I believe using InfoSec systems is interesting. | ||

| Top Management Support | TMS.1 | Top management commits all employees to adopt InfoSec system measures. | [125,126,127] |

| TMS.2 | Top management motivates employees to adopt the InfoSec system in their work. | ||

| TMS.3 | Top management provides reliable support for InfoSec system adoption. | ||

| TMS.4 | Top management is aware of the benefits that can be obtained by adopting InfoSec systems. | ||

| TMS.5 | Top management provides the necessary resources to adopt InfoSec systems. | ||

| IT Infrastructure | ITI.1 | IT infrastructure of my organization is good. | [128,129] |

| ITI.2 | IT infrastructure of my organization meets information security needs. | ||

| ITI.3 | IT infrastructure of my organization facilitates stakeholder collaboration. | ||

| ITI.4 | IT infrastructure of my organization is sufficient. | ||

| ITI.5 | IT infrastructure of my organization can support all procedures. | ||

| Security Training | TRN.1 | Guidance is provided for me on how to use InfoSec systems. | [74] |

| TRN.2 | Security guidelines are available to me on how to implement InfoSec procedures. | ||

| TRN.3 | Training courses are provided to enhance the adoption of InfoSec systems. | ||

| TRN.4 | Training is provided to clarify the features of the InfoSec system. | ||

| TRN.5 | InfoSec professionals are available to support me when I face security threats. | ||

| Legal- Governmental Regulation | G.REG.1 | Government regulations motivate organizations to adopt InfoSec systems. | [109,130,131] |

| G.REG.2 | Government regulations are necessary to help personnel to update the InfoSec system. | ||

| G.REG.3 | The government formulates regulations related to InfoSec systems usage. | ||

| G.REG.4 | Government regulations are necessary to ensure InfoSec systems adoption. | ||

| G.REG.5 | The country’s legal system encourages InfoSec systems adoption. | ||

| Attitude towards InfoSec Systems | ATT.1 | I believe adopting an InfoSec system is essential for my work. | [132,133] |

| ATT.2 | I believe adopting an InfoSec system is part of my daily job tasks. | ||

| ATT.3 | I believe adopting an InfoSec system is beneficial. | ||

| ATT.4 | My attitude towards an InfoSec system is favorable. | ||

| ATT.5 | I believe that InfoSec systems adoption is valuable in my organization. | ||

| Adoption of InfoSec Systems | ADPT.1 | How frequently do you use the InfoSec system in a week? | [134,135] |

| ADPT.2 | How frequently do you use the InfoSec system for job-related work? | ||

| ADPT.3 | How frequently do you use different applications of the InfoSec system? | ||

| ADPT.4 | How frequently do you use advanced features of InfoSec systems? |

References

- Lehto, M. Cyber-Attacks Against Critical Infrastructure. In Cyber Security; Computational Methods in Applied Sciences; Lehto, M., Neittaanmäki, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 56, pp. 3–42. ISBN 978-3-030-91292-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hanzu-Pazara, R.; Raicu, G.; Zagan, R. The Impact of Human Behaviour on Cyber Security of the Maritime Systems. Adv. Eng. Forum 2019, 34, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilchuk, S.; Reutov, V.; Nalivaychenko, E.; Shevchenko, E.; Yaroshenko, A. Ensuring the Security of an Automated Information System in a Regional Innovation Cluster. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M.A.; Arachchilage, N.A.G. The Role of Self-Efficacy on the Adoption of Information Systems Security Innovations: A Meta-Analysis Assessment. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2021, 25, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune Business Insights. Cybersecurity Market Size, Share & Industry Analysis; Fortune Business Insights: Pune, India, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cobalt. Top Cybersecurity Statistics for 2025. Available online: https://www.cobalt.io/blog/top-cybersecurity-statistics-2025 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Secure IT Consult 2025 Adoption Rates of Advanced Security Technologies: A Statistical Deep Dive. Available online: https://secureitconsult.com/advanced-security-tech-adoption-statistics/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Fox, T. Cybercrime to Cost the World $12.2 Trillion Annually by 2031. Cybercrime Magazine, 28 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Almubayedh, D.; Khalis, M.A.; Alazman, G.; Alabdali, M.; Al-Refai, R.; Nagy, N. Security Related Issues in Saudi Arabia Small Organizations: A Saudi Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st Saudi Computer Society National Computer Conference (NCC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 25–26 April 2018; IEEE: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- AlMindeel, R.; Martins, J.T. Information Security Awareness in a Developing Country Context: Insights from the Government Sector in Saudi Arabia. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 34, 770–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, A. Measuring the Level of Cyber-Security Awareness for Cybercrime in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajunaied, K.; Hussin, N.; Kamarudin, S. Behavioral Intention to Adopt FinTech Services: An Extension of Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, S.; Renno, W.; Bhardwaj, A. Unto the Breach: What the COVID-19 Pandemic Exposes about Digitalization. Inf. Organ. 2021, 31, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargiotis, D. Data Security and Privacy: Protecting Sensitive Information. In Data Governance; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 217–245. ISBN 978-3-031-67267-5. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, S.H.; Wider, W.; Tanucan, J.C.M.; Yew Lim, K.; Jiang, L.; Prompanyo, M. Key Factors Influencing Long-Term Retention among Contact Centre Employee in Malaysia: A Delphi Method Study. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2370444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catal, C.; Ozcan, A.; Donmez, E.; Kasif, A. Analysis of Cyber Security Knowledge Gaps Based on Cyber Security Body of Knowledge. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.Y.; Lee, S.-Y.T.; Lim, J.-H. Information Security Breaches and IT Security Investments: Impacts on Competitors. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, Ö.; Aktuğ, S.S.; Ozkan-Okay, M.; Yilmaz, A.A.; Akin, E. A Comprehensive Review of Cyber Security Vulnerabilities, Threats, Attacks, and Solutions. Electronics 2023, 12, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M.A.; Arachchilage, N.A.G. On the Impact of Perceived Vulnerability in the Adoption of Information Systems Security Innovations. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.08229. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; He, W.; Xu, L.; Ash, I.; Anwar, M.; Yuan, X. Investigating the Impact of Cybersecurity Policy Awareness on Employees’ Cybersecurity Behavior. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, T.C.; Herath, H.S.B.; D’Arcy, J. Organizational Adoption of Information Security Solutions: An Integrative Lens Based on Innovation Adoption and the Technology-Organization-Environment Framework. SIGMIS Database 2020, 51, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naradda Gamage, S.K.; Ekanayake, E.; Abeyrathne, G.; Prasanna, R.; Jayasundara, J.; Rajapakshe, P. A Review of Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Economies 2020, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.; Palivela, H. LCCI: A Framework for Least Cybersecurity Controls to Be Implemented for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.; Maximiano, M.; Gomes, R.; Pinto, D. Information Security and Cybersecurity Management: A Case Study with SMEs in Portugal. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2021, 1, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit Ozkan, B.; Spruit, M.; Wondolleck, R.; Burriel Coll, V. Modelling Adaptive Information Security for SMEs in a Cluster. J. Intellect. Cap. 2019, 21, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.; Maximiano, M.; Gomes, R. A Customizable Web Platform to Manage Standards Compliance of Information Security and Cybersecurity Auditing. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 196, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, M.; Chatterjee, D. Calculated Risk? A Cybersecurity Evaluation Tool for SMEs. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; McDonald, S.; Button, D.; McGarry, K. It Won’t Happen to Me: Surveying SME Attitudes to Cyber-Security. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2023, 63, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadok, M.; Alter, S.; Bednar, P. It Is Not My Job: Exploring the Disconnect between Corporate Security Policies and Actual Security Practices in SMEs. Int. Cont. Soc. 2020, 28, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, R.G.; Kemerer, C.F. The Illusory Diffusion of Innovation: An Examination of Assimilation Gaps. Inf. Syst. Res. 1999, 10, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Dong, S.; Xu, S.X.; Kraemer, K.L. Innovation Diffusion in Global Contexts: Determinants of Post-Adoption Digital Transformation of European Companies. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Kraemer, K.L.; Xu, S. The Process of Innovation Assimilation by Firms in Different Countries: A Technology Diffusion Perspective on e-Business. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1557–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momani, A.M. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A new approach in technology acceptance. Int. J. Sociotechnology Knowl. Dev. 2020, 12, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Lee, J.-N.; Straub, D. Institutional Influences on Information Systems Security Innovations. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 918–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N. Saudi Arabia’s Cybersecurity Market Poised for Growth amid Rising Investments. Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/node/2573805/business-economy (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Muthuswamy, V.V. Cyber Security Challenges Faced by Employees in the Digital Workplace of Saudi Arabia’s Digital Nature Organization. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2021, 17, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwraith, A. Information Security and Employee Behaviour: How to Reduce Risk Through Employee Education, Training and Awareness, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-0-429-28178-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.; McDonald, S. One Size Does Not Fit All: Exploring the Cybersecurity Perspectives and Engagement Preferences of UK-Based Small Businesses. Inf. Secur. J. A Glob. Perspect. 2025, 34, 15–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, B.H.; Hartwick, J.; Warshaw, P.R. The Theory of Reasoned Action: A Meta-Analysis of Past Research with Recommendations for Modifications and Future Research. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.; Xu, X. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Synthesis and the Road Ahead. Jab. Agama Islam Selangor 2016, 17, 328–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskerville, R. Risk Analysis: An Interpretive Feasibility Tool in Justifying Information Systems Security. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 1991, 1, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siponen, M.; Willison, R. Information Security Management Standards: Problems and Solutions. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granić, A. Educational Technology Adoption: A Systematic Review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 9725–9744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Karsh, B.-T. The Technology Acceptance Model: Its Past and Its Future in Health Care. J. Biomed. Inform. 2010, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Woo, S.E.; Kim, J. Attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence at Work: Scale Development and Validation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 920–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. Importance-Performance Map Analysis to Enhance the Performance of Attitude towards Mobile Wallet Adoption among Indian Consumer Segments. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 73, 946–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Night, S.; Bananuka, J. The Mediating Role of Adoption of an Electronic Tax System in the Relationship between Attitude towards Electronic Tax System and Tax Compliance. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2020, 25, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. Determinants of Perceived Ease of Use: Integrating Control, Intrinsic Motivation, and Emotion into the Technology Acceptance Model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J. An Acceptance Model for an Internet Protocol Television Service in Korea with Prior Experience as a Moderator. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 1883–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Zhang, X.; Tsang, W.Y. How Tourists Perceive the Usefulness of Technology Adoption in Hotels: Interaction Effect of Past Experience and Education Level. J. China Tour. Res. 2022, 18, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers in the Workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, D.; Chiu, W.; Byun, H. Factors Influencing Consumer Use of a Sport-Branded App: The Technology Acceptance Model Integrating App Quality and Perceived Enjoyment. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 1112–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-H.; Wang, S.-C.; Tsai, H.-H. Falling in Love with Online Games: The Uses and Gratifications Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1862–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Kim, D.J. Customer Self-Service Systems: The Effects of Perceived Web Quality with Service Contents on Enjoyment, Anxiety, and e-Trust. Decis. Support Syst. 2007, 43, 746–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitardi, V.; Marriott, H.R. Alexa, She’s Not Human But… Unveiling the Drivers of Consumers’ Trust in Voice-based Artificial Intelligence. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D. Does Remote Work Flexibility Enhance Organization Performance? Moderating Role of Organization Policy and Top Management Support. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, G.; Pilkauskaite, E. Implementing Process Innovation by Integrating Continuous Improvement and Business Process Re-Engineering. In Innovation Management; Škudienė, V., Li-Ying, J., Bernhard, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78990-981-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, I.; Wakefield, R.; Kim, S.; Kim, T. Security Awareness: The First Step in Information Security Compliance Behavior. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2021, 61, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwilling, M.; Klien, G.; Lesjak, D.; Wiechetek, Ł.; Cetin, F.; Basim, H.N. Cyber Security Awareness, Knowledge and Behavior: A Comparative Study. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 62, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S.R.; Pindek, S.; Kleinman, G.; Andel, S.A.; Spector, P.E. Information Security Climate and the Assessment of Information Security Risk among Healthcare Employees. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulton, R.; Coles, R.S. Applying Information Security Governance. Comput. Secur. 2003, 22, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, G.D.; Siponen, M.; Pahnila, S. Toward a Unified Model of Information Security Policy Compliance. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchendu, B.; Nurse, J.R.C.; Bada, M.; Furnell, S. Developing a Cyber Security Culture: Current Practices and Future Needs. Comput. Secur. 2021, 109, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, G.; Brown, I. The Influence of Organisational Culture and Information Security Culture on Employee Compliance Behaviour. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021, 34, 1203–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.N.D.; Sharma, S.K. Globalization and Information Management Strategy. In Encyclopedia of Information Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 475–487. ISBN 978-0-12-227240-0. [Google Scholar]

- Golightly, L.; Chang, V.; Xu, Q.A.; Gao, X.; Liu, B.S. Adoption of Cloud Computing as Innovation in the Organization. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2022, 14, 18479790221093992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, G.; Warraich, N.F.; Iftikhar, S. Digital Information Security Management Policy in Academic Libraries: A Systematic Review (2010–2022). J. Inf. Sci. 2025, 51, 1000–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, A.K. Cybersecurity Needs for SMEs. Issues Inf. Syst. 2024, 25, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsias, J.; Ahmad, A.; Scheepers, R. Adopting and Integrating Cyber-Threat Intelligence in a Commercial Organisation. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidster, W.W.; Rahman, S.S.M. Identifying Influences to Information Security Framework Adoption: Applying a Modified UTAUT. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–13 December 2020; IEEE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020; pp. 2605–2609. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Hsu, C.; Zhou, Z. Security Education, Training, and Awareness Programs: Literature Review. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 62, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungo, J. Self-Paced Cybersecurity Awareness Training Educating Retail Employees to Identify Phishing Attacks. J. Cyber Secur. Technol. 2024, 8, 71–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peery, J.G.; Pasalar, C. Designing the Learning Experiences in Serious Games: The Overt and the Subtle—The Virtual Clinic Learning Environment. Informatics 2018, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawood, H.; Skinner, G. Reviewing Cyber Security Social Engineering Training and Awareness Programs—Pitfalls and Ongoing Issues. Future Internet 2019, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.; Hajjej, F.; Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Shehab, R.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Alrawad, M. Explaining the Factors Affecting Students’ Attitudes to Using Online Learning (Madrasati Platform) during COVID-19. Electronics 2022, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalafi, N.; Veeraraghavan, P. Exploring the Challenges and Issues in Adopting Cybersecurity in Saudi Smart Cities: Conceptualization of the Cybersecurity-Based UTAUT Model. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1523–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwurah, N.; Adebayo, V.I.; Ige, A.B.; Idemudia, C.; Eyieyien, O.G. Ensuring Compliance with Regulatory and Legal Requirements through Robust Data Governance Structures. Open Access Res. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2024, 8, 036–044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassaf, M.; Alkhalifah, A. Exploring the Influence of Direct and Indirect Factors on Information Security Policy Compliance: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 162687–162705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamil, Y.; Lund, S.; Islam, M.S. Information Security Objectives and the Output Legitimacy of ISO/IEC 27001: Stakeholders’ Perspective on Expectations in Private Organizations in Sweden. Inf. Syst. e-Bus. Manag. 2023, 21, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Chadhar, M.; Vatanasakdakul, S.; Chetty, M. Factors Affecting the Organizational Adoption of Blockchain Yechnology: Extending the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) Framework in the Australian Context. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.; Reichert, S.; Schmid, J.; Strüker, J.; Neumann, D.; Fridgen, G. Dynamics of Blockchain Implementation-a Case Study from the Energy Sector. In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 2 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, P.; Tanner, M.; Johnston, K. Perceived Factors Influencing Blockchain Adoption in the Asset and Wealth Management Industry in the Western Cape, South Africa. In Evolving Perspectives on ICTs in Global Souths; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Junio, D.R., Koopman, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1236, pp. 48–62. ISBN 978-3-030-52013-7. [Google Scholar]

- Addula, S.R.; Tyagi, A.K.; Naithani, K.; Kumari, S. Blockchain-Empowered Internet of Things (IoTs) Platforms for Automation in Various Sectors. In Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Digital Twin for Smart Manufacturing; Tyagi, A.K., Tiwari, S., Arumugam, S.K., Sharma, A.K., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 443–477. ISBN 978-1-394-30357-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Alzoubi, Y.I.; Gill, A.Q.; Anwar, M.J. Cybersecurity Enterprises Policies: A Comparative Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akai, N.D.; Ibok, N.; Akinninyi, P.E. Cloud Accounting and the Quality of Financial Reports of Selected Banks in Nigeria. Eur. J. Account. Audit. Financ. Res. 2023, 11, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Gao, C.; Zhai, L.; Shahzad, F.; Arshad, M.R. Moderating Effects of Gender and Resistance to Change on the Adoption of Big Data Analytics in Healthcare. Complexity 2020, 2020, 2173765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaouf, A.; Altaqqi, O. The Impact of Gender Differences on Adoption of Information Technology and Related Responses: A Review. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Res. 2018, 5, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; He, W.; Ash, I.; Yuan, X.; Li, L.; Xu, L. Gender Difference and Employees’ Cybersecurity Behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daengsi, T.; Pornpongtechavanich, P.; Wuttidittachotti, P. Cybersecurity Awareness Enhancement: A Study of the Effects of Age and Gender of Thai Employees Associated with Phishing Attacks. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 4729–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, N.; Yoon, J.S.; Souders, D.; Stothart, C.; Yehnert, C. Predictors of Attitudes toward Autonomous Vehicles: The Roles of Age, Gender, Prior Knowledge, and Personality. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maswadi, K.; Ghani, N.A.; Hamid, S. Factors Influencing the Elderly’s Behavioural Intention to Use Smart Home Technologies in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Noland, R.B.; Mondschein, A.S. Attitudes towards Privately-Owned and Shared Autonomous Vehicles. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 72, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Salehin, M.F.; Nurul Habib, K. A Discrete Choice Experiment on Consumer’s Willingness-to-Pay for Vehicle Automation in the Greater Toronto Area. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 149, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. The Moderating Role of Gender and Age in the Adoption of Mobile Wallet. Foresight 2020, 22, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E.Y.; Akalp, G.; Aytac, S.; Bayram, N. Factors Influencing Information Security Management in Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Case Study from Turkey. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.F.; Dominic, P.D.D.; Ali, S.E.A.; Rehman, M.; Sohail, A. Information Security Behavior and Information Security Policy Compliance: A Systematic Literature Review for Identifying the Transformation Process from Noncompliance to Compliance. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenerry, B.; Chng, S.; Wang, Y.; Suhaila, Z.S.; Lim, S.S.; Lu, H.Y.; Oh, P.H. Preparing Workplaces for Digital Transformation: An Integrative Review and Framework of Multi-Level Factors. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 620766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Enriquez, B.G.; Arbulú Ballesteros, M.A.; Arbulu Perez Vargas, C.G.; Orellana Ulloa, M.N.; Gutiérrez Ulloa, C.R.; Pizarro Romero, J.M.; Gutiérrez Jaramillo, N.D.; Cuenca Orellana, H.U.; Ayala Anzoátegui, D.X.; López Roca, C. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Ethics Regarding the Use of ChatGPT among Generation Z University Students. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2024, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.H.; Le, H.N.Q. Investigation on Information Security Awareness Based on KAB Model: The Moderating Role of Age and Education Level. Int. Cont. Soc. 2024, 32, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, J.; Fel, S. How Sociodemographic Factors Relate to Trust in Artificial Intelligence among Students in Poland and the United Kingdom. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Medium Enterprises General Authority. SME Monitor: Monsha’at Quarterly Report Q4 2023; Saudi Medium Enterprises General Authority: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aldiab, A.; Chowdhury, H.; Kootsookos, A.; Alam, F.; Alluhaybi, A.; Aloufi, H. Telecommunication Infrastructure in Saudi Arabia: Is It Ready for eLearning? AIP Publishing LLC.: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2022; p. 020088. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4129-6556-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H. Sample Size Determination and Power Analysis Using the G*Power Software. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Dignity Trust Saudi Arabia; Human Dignity Trust: London, UK, 2024.

- Hochstetter-Diez, J.; Dieguez-Rebolledo, M.; Fenner-López, J.; Cachero, C. AIM triad: A prioritization strategy for public institutions to improve information security maturity. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbaş, C.; Tuzlukaya, Ş. Cyberattack and Cyberwarfare Strategies for Businesses. In Conflict Management in Digital Business; Özsungur, F., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2022; pp. 303–328. ISBN 978-1-80262-774-9. [Google Scholar]

- Changchit, C.; Lonkani, R.; Sampet, J. Mobile banking: Exploring determinants of its adoption. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2017, 27, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, J.; Lowry, P.B. Cognitive-affective Drivers of Employees’ Daily Compliance with Information Security Policies: A Multilevel, Longitudinal Study. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, B.; Richards, D.; Formosa, P.; McEwan, M.; Bajwa, M.H.A.; Hitchens, M.; Ryan, M. Modelling the ethical priorities influencing decision-making in cybersecurity contexts. Organ. Cybersecur. J. Pract. Process People 2023, 3, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J.; Larsson, L. Integration, Application and Importance of Collaboration in Sustainable Project Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, J.; Herath, T.; Shoss, M.K. Understanding employee responses to stressful information security requirements: A coping perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 31, 285–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reverté, F.; Gomis-López, J.M.; Díaz-Luque, P. Reset or temporary break? Attitudinal change, risk perception and future travel intention in tourists experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Tour. Futures 2022, 11, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, J.; He, Q.; Chan, A.P.C.; Owusu, E.K. Studies on the Success Criteria and Critical Success Factors for Mega Infrastructure Construction Projects: A Literature Review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 1809–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razikin, K.; Soewito, B. Cybersecurity decision support model to designing information technology security system based on risk analysis and cybersecurity framework. Egypt. Inform. J. 2022, 23, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Aldraiweesh, A.A.; Alamri, M.M.; Aljarboa, N.A.; Alturki, U.; Aljeraiwi, A.A. Integrating Technology Acceptance Model with Innovation Diffusion Theory: An Empirical Investigation on Students’ Intention to Use e-Learning Systems. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 26797–26809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Li, N.; Al-Adwan, A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Habibi, A. “Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Predict University Students’ Intentions to Use Metaverse Based Learning Platforms”. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15381–15413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqih, K.M.S.; Jaradat, M.-I.R.M. Integrating TTF and UTAUT2 Theories to Investigate the Adoption of Augmented Reality Technology in Education: Perspective from a Developing Country. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.Y. The Adoption of Virtual Reality Devices: The Technology Acceptance Model Integrating Enjoyment, Social Interaction, and Strength of the Social Ties. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 39, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada, R.; Rivera, L.; Delgadillo, R.; Cajo, B.H. Technological Aspects for Pleasant Learning: A Review of the Literature. Informatics 2021, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Xu, K.; Sotiriadis, M.; Wang, Y. Exploring the Factors Influencing the Adoption and Usage of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Applications in Tourism Education within the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 30, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-Y.; Liu, F.-H.; Tsou, H.-T.; Chen, L.-J. Openness of Technology Adoption, Top Management Support and Service Innovation: A Social Innovation Perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.F.; Tian, F.; Ng, P.M.L. Top Management Support and Knowledge Sharing: The Strategic Role of Affiliation and Trust in Academic Environment. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 2161–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.Y.; Ma, L. Information Technology Investment and Digital Transformation: The Roles of Digital Transformation Strategy and Top Management. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanopas, A.; Krairit, D.; Ba Khang, D. Managing Information Technology Infrastructure: A New Flexibility Framework. Manag. Res. News 2006, 29, 632–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Li, R.Y.M.; Corchado, J.M.; Cheong, P.H.; Mossberger, K.; Mehmood, R. Understanding Local Government Digital Technology Adoption Strategies: A PRISMA Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Furnell, S. Motivating Information Security Policy Compliance: Insights from Perceived Organizational Formalization. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 62, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdaljaleel, M.; Barakat, M.; Alsanafi, M.; Salim, N.A.; Abazid, H.; Malaeb, D.; Mohammed, A.H.; Hassan, B.A.R.; Wayyes, A.M.; Farhan, S.S.; et al. A Multinational Study on the Factors Influencing University Students’ Attitudes and Usage of ChatGPT. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rather, R.A. Monitoring the Impacts of Tourism-Based Social Media, Risk Perception and Fear on Tourist’s Attitude and Revisiting Behaviour in the Wake of COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3275–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çallı, L. Exploring Mobile Banking Adoption and Service Quality Features through User-Generated Content: The Application of a Topic Modeling Approach to Google Play Store Reviews. Int. J. Biomed. 2023, 41, 428–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Chang, L.L.; Yu, C.-P.; Chen, J. Examining an Extended Technology Acceptance Model with Experience Construct on Hotel Consumers’ Adoption of Mobile Applications. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-75742-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-292-02190-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS, 7th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-003-11745-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, Y.P. Advanced Research Statistics: Regression Test, Factor Analysis and SEM Analysis; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, N. Detecting Multicollinearity in Regression Analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2020, 8, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2022; pp. 587–632. ISBN 978-3-319-57411-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis, 3rd ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ashenden, D. In Their Own Words: Employee Attitudes towards Information Security. Int. Cont. Soc. 2018, 26, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.; Alfaisal, R.; Salloum, S.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Shishakly, R.; Lutfi, A.; Alrawad, M.; Mulhem, A.; Awad, A.; Al-Maroof, R. Integrating Teachers’ TPACK Levels and Students’ Learning Motivation, Technology Innovativeness, and Optimism in an IoT Acceptance Model. Electronics 2022, 11, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, A.; Mouzakitis, S.; Bounas, K.; Askounis, D. A Cyber-Security Culture Framework for Assessing Organization Readiness. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 62, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humaidi, N.; Balakrishnan, V. Indirect Effect of Management Support on Users’ Compliance Behaviour towards Information Security Policies. HIM J. 2018, 47, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hina, S.; Dominic, P.D.D. Information Security Policies’ Compliance: A Perspective for Higher Education Institutions. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2020, 60, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, Y.O.; Shehab, E.; Al-Ashaab, A. Developing a Digital Transformation Process in the Manufacturing Sector: Egyptian Case Study. Inf. Syst. e-Bus. Manag. 2022, 20, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushi, M.; Dutta, R. Human Factors in Network Reliability Engineering. J. Netw. Syst. Manag. 2018, 26, 686–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, I.; Tsochev, G. Vulnerability and Protection of Business Management Systems: Threats and Challenges. Probl. Eng. Cybern. Robot. 2020, 72, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhi, M.I. The Role of Technology, Government, Law, And Social Trust on e-Commerce Adoption. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 25, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Tanwar, S.; Rana, A. The Need for Information Security Management for SMEs. In Proceedings of the 2020 9th International Conference System Modeling and Advancement in Research Trends (SMART), Moradabad, India, 4 December 2020; IEEE: Moradabad, India, 2020; pp. 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, Z.; Razli, I.A.; Ing, P. Does Security Concern, Perceived Enjoyment and Government Support Affect Fintech Adoption? Focused on Bank Users. J. Mark. Adv. Pract. 2021, 3, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, K.C.; Zhang, X.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Tam, K.Y. Protecting Against Threats to Information Security: An Attitudinal Ambivalence Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2021, 38, 732–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, R.W. Cognitive and Physiological Processes in Fear Appeals and Attitude Change: A Revised Theory of Protection Motivation. In Social Psychophysiology; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A.; Hasan, N.; Abayomi-Alli, O.; Hardaker, G.; Scherer, R.; Sarker, Y.; Kumar Paul, S.; Maitama, J.Z. Gender Differences in Information and Communication Technology Use & Skills: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 4225–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namahoot, K.S.; Rattanawiboonsom, V. Integration of TAM Model of Consumers’ Intention to Adopt Cryptocurrency Platform in Thailand: The Mediating Role of Attitude and Perceived Risk. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 2022, 9642998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Ming, T.H.; Baigh, T.A.; Sarker, M. Adoption of Artificial Intelligence in Banking Services: An Empirical Analysis. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 4270–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhafeeri, F.M. Perspectives of Radiographers on the Emergence of Artificial Intelligence in Diagnostic Imaging in Saudi Arabia. Insights Imaging 2022, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanche-Gracia, D.; Casaló-Ariño, L.V.; Pérez-Rueda, A. Determinants of Multi-Service Smartcard Success for Smart Cities Development: A Study Based on Citizens’ Privacy and Security Perceptions. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazi, L.; Zaniboni, S.; Wang, M. Age Differences in the Adoption of Technology at Work: A Review and Recommendations for Managerial Practice. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2025, 38, 138–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavandi, H.; Jaana, M. Factors That Affect Health Information Technology Adoption by Seniors: A Systematic Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 1827–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollini, A.; Callari, T.C.; Tedeschi, A.; Ruscio, D.; Save, L.; Chiarugi, F.; Guerri, D. Leveraging Human Factors in Cybersecurity: An Integrated Methodological Approach. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2022, 24, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Hong, W.C.H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kolletar-Zhu, K. How Education Level Influences Internet Security Knowledge, Behaviour, and Attitude: A Comparison among Undergraduates, Postgraduates and Working Graduates. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 22, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanja, E. The Role of the Chief Information Security Officer in the Management of IT Security. Int. Cont. Soc. 2017, 25, 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar, D.; Abedin, B.; Shirahada, K. The Role of Employees in Digital Transformation: A Preliminary Study on How Employees’ Digital Literacy Impacts Use of Digital Technologies. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 7837–7848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Operational Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Prior Experience | Employees’ level of knowledge acquired from past experience in adopting the InfoSec system | Al-Rahmi et al. [123]; Li et al. [20] |

| Enjoyment of New InfoS Technology | Employees’ perception regarding convenience, enjoyment, pleasant experience, and engagement obtained from the adoption of InfoSec technology | Al-Adwan et al. [124]; Faqih and Jaradat [125]; Lee et al. [126]; Quezada et al. [127]; Shen et al. [128] |

| Top Management Support | Employees’ perception regarding the support, motivation, commitment to providing all resources, and awareness of the benefits that top management provides to them during their employment | Hsu et al. [129]; Lo et al. [130]; Zhang et al. [131] |

| IT Infrastructure | Employees’ perception regarding a shared collection of IT resources that supports organizational communication and enables current and future business applications | Chanopas et al. [132] |

| Security Training | An instructional tool and communication tool to activate employees’ thinking processes, persuade them to act appropriately, and enable them to gain a better understanding of security policies and procedures | Hu et al. [75] |

| Legal-Governmental Regulation | Employees’ perception of designing and implementing all necessary rules and regulations needed to control personnel and InfoSec systems within an organization | D’Arcy and Lowry [113]; David et al. [130]; Hong and Furnell [131] |

| Attitude towards InfoSec systems | Employees’ feelings, normative beliefs, and evaluations about InfoSec systems in terms of usefulness, usability, and effectiveness | Abdaljaleel et al. [132]; Rather [133] |

| Adoption of InfoSec systems | Frequency, time, level of usage of InfoSec systems, and level of usage of advanced features of InfoSec systems | Çallı [134]; Huang et al. [135] |

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 175 | 41.9% |

| Female | 243 | 58.1% | |

| Age | 20–30 years | 81 | 19.4% |

| 31–40 years | 206 | 49.3% | |

| Over 41 years | 131 | 31.3% | |

| Education | High School | 59 | 14.1% |

| Diploma | 77 | 18.4% | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 186 | 44.5% | |

| Master’s Degree or above | 96 | 23.0% | |

| Occupation | Employee | 167 | 40.0% |

| Mid-level Manager | 130 | 31.1% | |

| Top-level Manager | 121 | 28.9% |

| Factor 1: Legal- Governmental Regulations | Factor 2: Top Management Support | Factor 3: IT Infrastructure | Factor 4: Prior Experience | Factor 5: Security Training | Factor 6: Enjoyment of New InfoSec Technology | Factor 7: Adoption of InfoSec Systems | Factor 8: Attitude Toward InfoSec Systems | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADPT.1 | 0.824 | |||||||

| ADPT.2 | 0.859 | |||||||

| ADPT.3 | 0.629 | |||||||

| ADPT.4 | 0.698 | |||||||

| ATT.1 | 0.695 | |||||||

| ATT.2 | 0.747 | |||||||

| ATT.3 | 0.792 | |||||||

| ATT.4 | 0.782 | |||||||

| ATT.5 | 0.758 | |||||||

| TRN.1 | 0.761 | |||||||

| TRN.2 | 0.830 | |||||||

| TRN.3 | 0.796 | |||||||

| TRN.4 | 0.690 | |||||||

| TRN.5 | 0.731 | |||||||

| PE.1 | 0.795 | |||||||

| PE.2 | 0.806 | |||||||

| PE.3 | 0.795 | |||||||

| PE.4 | 0.762 | |||||||

| PE.5 | 0.743 | |||||||

| ENJ.1 | 0.676 | |||||||

| ENJ.2 | 0.750 | |||||||

| ENJ.3 | 0.782 | |||||||

| ENJ.4 | 0.738 | |||||||

| ENJ.5 | 0.623 | |||||||

| TMS.1 | 0.818 | |||||||

| TMS.2 | 0.826 | |||||||

| TMS.3 | 0.836 | |||||||

| TMS.4 | 0.803 | |||||||

| TMS.5 | 0.784 | |||||||

| ITI.1 | 0.842 | |||||||

| ITI.2 | 0.784 | |||||||

| ITI.3 | 0.843 | |||||||

| ITI.4 | 0.767 | |||||||

| ITI.5 | 0.848 | |||||||

| G.REG.1 | 0.812 | |||||||

| G.REG.2 | 0.841 | |||||||

| G.REG.3 | 0.829 | |||||||

| G.REG.4 | 0.825 | |||||||

| G.REG.5 | 0.803 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prior Experience | r | 1 | |||||||

| p-value | ||||||||||

| 2 | Enjoyment of New InfoSec Technology | r | −0.160 ** | 1 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.001 | |||||||||

| 3 | Top Management Support | r | 0.171 *** | −0.038 | 1 | |||||

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.435 | ||||||||

| 4 | IT Infrastructure | r | 0.264 *** | 0.139 ** | −0.299 *** | 1 | ||||

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.005 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 5 | Security Training | r | 0.268 *** | 0.128 ** | −0.001 | 0.263 *** | 1 | |||

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.987 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 6 | Legal-Governmental Regulations | r | 0.326 *** | −0.222 *** | 0.501 *** | −0.088 | 0.045 | 1 | ||

| p-value | <0.001 | < 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.072 | 0.361 | |||||

| 7 | Attitude toward InfoSec Systems | r | 0.420 *** | −0.129 ** | 0.651 *** | 0.057 | 0.171 *** | 0.596 *** | 1 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.241 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 8 | Adoption of InfoSec Systems | r | 0.029 | 0.003 | 0.062 | 0.086 | 0.119 * | 0.075 | 0.164 *** | 1 |

| p-value | 0.560 | 0.952 | 0.202 | 0.077 | 0.015 | 0.127 | <0.001 |

| Mean | Std. Deviation | SFL | α | CR | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Experience | PE.1 | 2.92 | 1.010 | 0.801 | 0.885 | 0.885 | 0.607 |

| PE.2 | 2.88 | 0.971 | 0.813 | ||||

| PE.3 | 2.93 | 0.958 | 0.783 | ||||

| PE.4 | 2.93 | 0.952 | 0.755 | ||||

| PE.5 | 2.93 | 0.989 | 0.741 | ||||

| Enjoyment of New InfoSec Technology | ENJ.1 | 1.83 | 0.860 | 0.675 | 0.837 | 0.839 | 0.511 |

| ENJ.2 | 1.79 | 0.867 | 0.750 | ||||

| ENJ.3 | 1.81 | 0.847 | 0.779 | ||||

| ENJ.4 | 1.80 | 0.895 | 0.736 | ||||

| ENJ.5 | 1.73 | 0.838 | 0.624 | ||||

| Top Management Support | TMS.1 | 3.64 | 1.100 | 0.812 | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.661 |

| TMS.2 | 3.64 | 1.089 | 0.825 | ||||

| TMS.3 | 3.62 | 1.051 | 0.834 | ||||

| TMS.4 | 3.61 | 1.050 | 0.806 | ||||

| TMS.5 | 3.61 | 1.056 | 0.788 | ||||

| Security Training | TRN.1 | 2.45 | 1.022 | 0.762 | 0.873 | 0.874 | 0.581 |

| TRN.2 | 2.46 | 1.015 | 0.826 | ||||

| TRN.3 | 2.43 | 1.020 | 0.796 | ||||

| TRN.4 | 2.50 | 0.968 | 0.693 | ||||

| TRN.5 | 2.39 | 1.008 | 0.728 | ||||

| IT Infrastructure | ITI.1 | 2.28 | 1.286 | 0.844 | 0.908 | 0.909 | 0.666 |

| ITI.2 | 2.43 | 1.312 | 0.788 | ||||

| ITI.3 | 2.39 | 1.270 | 0.833 | ||||

| ITI.4 | 2.42 | 1.305 | 0.762 | ||||

| ITI.5 | 2.33 | 1.329 | 0.850 | ||||

| Legal-Governmental Regulations | G.REG.1 | 3.89 | 1.117 | 0.802 | 0.912 | 0.912 | 0.675 |

| G.REG.2 | 3.93 | 1.093 | 0.830 | ||||

| G.REG.3 | 3.82 | 1.155 | 0.834 | ||||

| G.REG.4 | 3.87 | 1.106 | 0.827 | ||||

| G.REG.5 | 3.96 | 1.104 | 0.815 | ||||

| Attitude toward InfoSec Systems | ATT.1 | 4.45 | 0.674 | 0.699 | 0.873 | 0.873 | 0.580 |

| ATT.2 | 4.37 | 0.685 | 0.752 | ||||

| ATT.3 | 4.37 | 0.678 | 0.794 | ||||

| ATT.4 | 4.44 | 0.677 | 0.780 | ||||

| ATT.5 | 4.39 | 0.678 | 0.780 | ||||

| Adoption of InfoSec Systems | ADPT.1 | 3.80 | 1.156 | 0.812 | 0.840 | 0.841 | 0.574 |

| ADPT.2 | 3.79 | 1.126 | 0.863 | ||||

| ADPT.3 | 3.84 | 1.080 | 0.631 | ||||

| ADPT.4 | 3.88 | 1.045 | 0.702 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attitude toward InfoSec Systems | ||||||||

| 2 | Prior Experience | 0.379 | |||||||

| 3 | Top Management Support | 0.606 | 0.153 | ||||||

| 4 | Security Training | 0.164 | 0.239 | 0.004 | |||||

| 5 | Legal-Governmental Regulations | 0.739 | 0.293 | 0.460 | 0.044 | ||||

| 6 | IT Infrastructure | 0.067 | 0.245 | 0.275 | 0.246 | 0.076 | |||

| 7 | Adoption of InfoSec Systems | 0.165 | 0.024 | 0.040 | 0.134 | 0.051 | 0.114 | ||

| 8 | Enjoyment of New InfoSec Technology | 0.120 | 0.145 | 0.049 | 0.116 | 0.210 | 0.120 | 0.004 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enjoyment of New InfoSec Technology | 0.715 | |||||||

| 2 | Attitude toward InfoSec Systems | −0.114 | 0.762 | ||||||

| 3 | Prior Experience | −0.142 | 0.381 | 0.779 | |||||

| 4 | Top Management Support | −0.032 | 0.601 | 0.155 | 0.813 | ||||

| 5 | Security Training | 0.114 | 0.152 | 0.240 | −0.001 | 0.762 | |||

| 6 | Legal-Governmental Regulations | −0.199 | 0.738 | 0.297 | 0.461 | 0.040 | 0.822 | ||

| 7 | IT Infrastructure | 0.124 | 0.054 | 0.241 | −0.277 | 0.238 | −0.082 | 0.816 | |

| 8 | Adoption of InfoSec Systems | 0.003 | 0.158 | 0.011 | 0.048 | 0.129 | 0.053 | 0.095 | 0.757 |

| H | Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ATT → ADPT | 0.222 *** | 0.066 | 3.390 *** | *** | Supported |

| H2 | PE → ATT | 0.069 *** | 0.019 | 3.575 *** | *** | Supported |

| H3 | ENJ → ATT | −0.006 | 0.025 | −0.241 | 0.810 | Not Supported |

| H4 | TMS → ATT | 0.253 *** | 0.018 | 14.297 *** | *** | Supported |

| H5 | ITI → ATT | 0.086 *** | 0.012 | 7.033 *** | *** | Supported |

| H6 | TRN → ATT | 0.049 ** | 0.017 | 2.934 ** | 0.003 | Supported |

| H7 | G.REG → ATT | 0.335 *** | 0.016 | 20.475 *** | *** | Supported |

| H | Path | Estimate | S.E. | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H8_a | PE → ATT → ADPT | 0.016 ** | 0.006 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H8_b | ENJ → ATT → ADPT | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.784 | Not Supported |

| H8_c | TMS → ATT → ADPT | 0.066 ** | 0.022 | 0.005 | Supported |

| H8_d | ITI → ATT → ADPT | 0.030 ** | 0.011 | 0.003 | Supported |

| H8_e | TRN → ATT → ADPT | 0.012 ** | 0.006 | 0.006 | Supported |

| H8_f | G.REG → ATT → ADPT | 0.094 ** | 0.031 | 0.005 | Supported |

| H | Path | Male β (p-Value) | Female β (p-Value) | χ2 (p-Value) | Δχ2 (p-Value) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstraint Model | 17.628 (0.127) | |||||

| Fully Constraint Model | 84.309 *** (<0.001) | 66.681 *** (<0.001) | Supported | |||

| H9_a | PE → ATT | 0.138 *** (<0.001) | 0.034 (0.083) | 25.184 * (0.022) | 7.556 ** (0.006) | Supported |

| H9_b | ENJ → ATT | 0.037 (0.433) | −0.043 (0.075) | 19.904 (0.908) | 2.276 (0.131) | Not Supported |

| H9_c | TMS → ATT | 0.344 *** (<0.001) | 0.175 *** (<0.001) | 41.142 *** (<0.001) | 23.514 * (0.023) | Supported |

| H9_d | ITI → ATT | 0.076 *** (<0.001) | 0.078 *** (<0.001) | 17.635 (0.172) | 0.007 (0.933) | Not Supported |

| H9_e | TRN → ATT | 0.060 * (0.046) | 0.053 ** (0.002) | 18.640 (0.135) | 1.011 (0.315) | Not Supported |

| H9_f | G.REG → ATT | 0.326 *** (<0.001) | 0.274 *** (<0.001) | 20.235 (0.090) | 2.607 (0.106) | Not Supported |

| H9_g | ATT → ADPT | 0.336 * (0.014) | 0.274 ** (0.003) | −0.032 (0.806) | 4.704 (0.095) | Not Supported |

| H | Path | 20–30 Years β (p-Value) | 31–40 Years β (p-Value) | Over 41 Years β (p-Value) | χ2 (p-Value) | Δχ2 (p-Value) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstraint Model | 15.335 (0.639) | ||||||

| Fully Constraint Model | 37.218 (0.241) | 21.883 (0.081) | Supported | ||||

| H10_a | PE → ATT | 0.090 * (0.050) | 0.083 * (0.028) | 0.099 * (0.012) | 18.609 (0.547) | 3.273 (0.195) | Not Supported |

| H10_b | ENJ → ATT | 0.040 (0.532) | −0.024 (0.485) | −0.018 (0.698) | 16.135 (0.708) | 0.800 (0.670) | Not Supported |

| H10_c | TMS → ATT | 0.235 *** (<0.001) | 0.261 *** (<0.001) | 0.250 *** (<0.001) | 15.645 (0.738) | 0.309 (0.857) | Not Supported |

| H10_d | ITI → ATT | 0.140 * (0.039) | 0.102 *** (<0.001) | 0.084 *** (<0.001) | 18.976 (0.523) | 3.640 (0.162) | Not Supported |

| H10_e | TRN → ATT | 0.095 * (0.010) | 0.083 * (0.038) | 0.058 * (0.036) | 18.887 (0.529) | 3.551 (0.169) | Not Supported |

| H10_f | G.REG → ATT | 0.386 *** (<0.001) | 0.351 *** (<0.001) | 0.285 *** (<0.001) | 20.584 (0.422) | 5.248 (0.073) | Not Supported |

| H10_g | ATT → ADPT | 0.336 * (0.014) | 0.274 ** (0.003) | 0.326 * (0.001) | 15.335 (0.639) | 4.704 (0.095) | Not Supported |

| H | Path | High School β (p-Value) | Diploma β (p-Value) | Bachelor’s Degree β (p-Value) | Master’s Degree β (p-Value) | χ2 (p-Value) | Δχ2 (p-Value) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstraint Model | 26.208 (0.343) | |||||||

| Fully Constraint Model | 61.741 * (0.049) | 35.533 * (0.025) | Supported | |||||

| H11_a | PE → ATT | 0.190 * (0.042) | 0.238 * (0.036) | 0.290 * (0.026) | 0.240 * (0.049) | 26.768 (0.476) | 0.561 (0.905) | Not Supported |

| H11_b | ENJ → ATT | 0.040 (0.532) | −0.062 (0.281) | 0.035 (0.327) | −0.056 (0.243) | 29.889 (0.319) | 3.681 (0.298) | Not Supported |

| H11_c | TMS → ATT | 0.279 *** (<0.001) | 0.220 *** (<0.001) | 0.254 *** (<0.001) | 0.234 *** (<0.001) | 31.357 (0.257) | 5.150 (0.161) | Not Supported |

| H11_d | ITI → ATT | 0.071 * (0.049) | 0.087 * (0.049) | 0.197 * (0.036) | 0.296 *** (<0.001) | 38.638 (0.068) | 12.430 ** (0.006) | Supported |

| H11_e | TRN → ATT | 0.095 * (0.010) | 0.034 * (0.048) | 0.067 ** (0.005) | 0.080 * (0.007) | 27.195 (0.453) | 0.987 (0.804) | Not Supported |

| H11_f | G.REG → ATT | 0.257 *** (<0.001) | 0.330 ** (<0.001) | 0.389 *** (<0.001) | 0.486 *** (<0.001) | 34.779 (0.145) | 8.571 * (0.036) | Supported |

| H11_g | ATT → ADPT | 0.292 ** (0.002) | 0.271 * (0.004) | 0.250 * (0.039) | 0.266 * (0.021) | 28.232 (0.399) | 2.024 (0.567) | Not Supported |

| H | Path | Employee β (p-Value) | Mid-Level Manager β (p-Value) | Top-Level Manager β (p-Value) | χ2 (p-Value) | Δχ2 (p-Value) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstraint Model | 18.367 (0.432) | ||||||

| Fully Constraint Model | 73.916 *** (<0.001) | 55.549 *** (<0.001) | Supported | ||||

| H12_a | PE → ATT | 0.118 *** (<0.001) | −0.012 (0.663) | 0.042 (0.179) | 27.086 (0.133) | 8.719 *** (<0.001) | Supported |

| H12_b | ENJ → ATT | 0.048 (0.288) | −0.012 (0.702) | −0.013 (0.762) | 26.471 (0.151) | 2.104 (0.517) | Not Supported |

| H12_c | TMS → ATT | 0.266 *** (<0.001) | 0.183 *** (<0.001) | 0.263 *** (<0.001) | 24.470 (0.222) | 6.103 * (0.047) | Supported |

| H12_d | ITI → ATT | 0.092 *** (<0.001) | 0.115 *** (<0.001) | 0.069 *** (<0.001) | 21.241 (0.383) | 2.874 (0.238) | Not Supported |

| H12_e | TRN → ATT | 0.095 * (0.029) | 0.071 ** (0.004) | 0.063 ** (0.008) | 19.111 (0.515) | 0.744 (0.690) | Not Supported |

| H12_f | G.REG → ATT | 0.335 *** (<0.001) | 0.246 *** (<0.001) | 0.328 *** (<0.001) | 24.831 (0.208) | 6.464 * (0.039) | Supported |

| H12_g | ATT → ADPT | 0.050 (0.533) | 0.498 ** (0.008) | 0.684 *** (<0.001)- | 35.866 * (0.016) | 17.499 * (0.018) | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dighriri, A.A.M.; Chatrath, S.K.; Mohammadian, M. Exploring Determinants of Information Security Systems Adoption in Saudi Arabian SMEs: An Integrated Multitheoretical Model. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040113

Dighriri AAM, Chatrath SK, Mohammadian M. Exploring Determinants of Information Security Systems Adoption in Saudi Arabian SMEs: An Integrated Multitheoretical Model. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2025; 5(4):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040113

Chicago/Turabian StyleDighriri, Ali Abdu M, Sarvjeet Kaur Chatrath, and Masoud Mohammadian. 2025. "Exploring Determinants of Information Security Systems Adoption in Saudi Arabian SMEs: An Integrated Multitheoretical Model" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 5, no. 4: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040113

APA StyleDighriri, A. A. M., Chatrath, S. K., & Mohammadian, M. (2025). Exploring Determinants of Information Security Systems Adoption in Saudi Arabian SMEs: An Integrated Multitheoretical Model. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 5(4), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040113