Abstract

This study examines the adoption and implementation of the Zero Trust (ZT) cybersecurity paradigm using the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework. While ZT is gaining traction as a security model, many organizations struggle to align strategic intent with effective implementation. We adopted a sequential mixed-methods design combining 27 semi-structured interviews with cybersecurity professionals and a survey of 267 experts across industries. The qualitative phase used an inductive approach to identify organizational challenges, whereas the quantitative phase employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the hypothesized relationships. Results show that information security culture and investment significantly influence both strategic alignment and the technical implementation of ZT. Implementation acted as an intermediary mechanism through which these organizational factors affected governance and compliance outcomes. Strategic commitment alone was insufficient to drive effective implementation without strong cultural support. Qualitative insights underscored the importance of leadership engagement, cross-functional collaboration, and legacy infrastructure readiness in shaping outcomes. The findings emphasize the need for cultural alignment, targeted investments, and process maturity to ensure successful ZT adoption. Organizations can leverage these insights to prioritize resources, strengthen governance, and reduce implementation friction. This research is among the first to empirically investigate ZT implementation through the TOE lens. It contributes to cybersecurity management literature by integrating strategic, cultural, and operational dimensions of ZT adoption and offers practical guidance for decision-makers seeking to institutionalize Zero Trust principles.

1. Introduction

The growing complexity of cyber threats, combined with the widespread adoption of hybrid work models, has catalyzed a surge of interest in Zero Trust (ZT) security frameworks [1]. Rooted in the principle of “never trust, always verify” [2], ZT rejects the traditional perimeter-based model and instead enforces continuous authentication, contextual access controls, and granular network segmentation to mitigate security risks [3]. More than an incremental evolution of security measures, ZT represents a disruptive paradigm that demands cultural, architectural, and regulatory transformation [4,5]. Unlike discrete tools such as firewalls, intrusion detection systems, or VPN hardening, ZT embeds trust-minimization principles into governance, compliance, and daily operations [6,7]. Despite its growing appeal and endorsement by global cybersecurity leaders such as the U.S. Department of Defense, CISA, and Google [8,9], most organizations remain in the early phases of ZT adoption [10].

The ZT security framework thus represents a paradigm shift in organizational cybersecurity, offering a proactive and adaptive response to the escalating complexity of cyber threats [11]. Real-world applications underscore ZT’s transformative potential: Google’s BeyondCorp—developed in response to the 2009 Operation Aurora attack—eliminated reliance on VPNs by enabling secure access from untrusted networks [12]. Sectors such as finance, energy, and healthcare have also embraced ZT. Bank of America applies network micro-segmentation, multifactor authentication, and advanced analytics; Duke Energy uses continuous monitoring and dynamic access controls to limit lateral movement; and Mayo Clinic employs encryption, identity management, and data loss prevention to meet HIPAA compliance and maintain patient trust [13]. Despite such practical relevance, academic research has predominantly emphasized ZT’s technical dimension, often overlooking its organizational and environmental complexities.

Empirical evidence also supports ZT’s effectiveness—particularly among micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs)—where its implementation has led to a 45% reduction in security incidents [14]. Furthermore, ZT-related patents have been positively associated with improvements in government effectiveness and regulatory quality [6]. Despite these advances, literature reviews indicate that ZT research has largely focused on technological components such as architectures, encryption, identity management, and micro-segmentation [15,16,17], while neglecting the distinct organizational and environmental complexities of ZT adoption. Compared to other cybersecurity solutions, ZT requires not only technical readiness but also organizational culture alignment, sustained financial investment, and adaptation to regulatory pressures—areas where empirical inquiry remains scarce [18,19,20].

Although ZT was introduced more than a decade ago [4], critical gaps remain regarding its effective management, with limited consensus on implementation criteria and insufficient attention to diverse organizational and environmental contexts [18,20,21]. Challenges such as limited resources, resistance rooted in organizational culture, skill shortages, and regulatory pressures continue to hinder effective implementation [1]. This gap underscores the theoretical and practical need to study ZT not as another security tool, but as a transformative paradigm whose adoption dynamics differ from conventional security technologies. In particular, empirical research applying structured frameworks such as Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) remains limited, leaving unanswered questions about the interplay among organizational, technological, and environmental factors shaping ZT implementation.

Accordingly, this study draws on the TOE framework [22], which provides a holistic model for examining the technological readiness, organizational capacity, and environmental pressures shaping this innovative cybersecurity paradigm. TOE has proven valuable in research on digital transformation and artificial intelligence (AI) implementation [23,24], yet has not been comprehensively applied to the ZT paradigm. By employing TOE, this study addresses the lack of empirical work that systematically captures the organizational and environmental complexities of ZT implementation, offering a theoretical lens that extends beyond technical considerations.

This research adopts a sequential mixed-methods approach. First, an inductive phase involving semi-structured interviews with 27 information security professionals across multiple industries explored emergent challenges in ZT integration. Second, a deductive phase employed a structured survey of 267 cybersecurity practitioners to empirically validate the TOE framework’s applicability to ZT adoption. Guided by this perspective, the central research question asks:

How do technological, organizational, and environmental factors influence the implementation of the Zero Trust security paradigm in organizations, and what mechanisms explain its effects on governance and compliance?

Preliminary findings reveal the central role of organizational enablers in the successful adoption of the ZT paradigm. A strong information security culture emerged as a key driver, influencing both the formation of strategic commitments to ZT and the effective implementation of its principles. Likewise, organizational investment in cybersecurity infrastructure proved essential for fostering strategic alignment and translating it into operational execution. While strategic commitment alone did not guarantee implementation success, the study found that effective ZT implementation significantly contributes to improved governance and regulatory compliance. Furthermore, the results suggest that organizational culture and investment affect governance outcomes indirectly, by enabling robust technological adoption. These insights reinforce the importance of addressing not only technological readiness but also the organizational and environmental contexts that shape the success of ZT initiatives.

This study offers important theoretical and practical contributions by extending the TOE framework to the domain of cybersecurity, specifically to the ZT paradigm. It contributes to cybersecurity literature by demonstrating TOE’s capacity to explain not only technology adoption but also paradigm-level transformations that demand organizational and regulatory alignment. By theorizing ZT implementation as mediating mechanism and organizational culture as a moderating condition, the study advances TOE’s explanatory power in high-risk digital environments and provides a structured lens to differentiate ZT from conventional security technologies. Practically, the findings equip organizations with a structured approach to assess their readiness for ZT adoption by aligning internal capabilities with external demands. As cyber threats become increasingly sophisticated, this study provides a timely roadmap for reshaping cybersecurity postures—moving from reactive, perimeter-based models to proactive, trust-driven architectures. It underscores that sustainable adoption of emerging cybersecurity frameworks requires not only robust technologies but also deeply embedded organizational alignment and environmental foresight.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical foundations of ZT and the TOE framework. Section 3 outlines the research design and methodological approach. Section 4 reports empirical findings, while Section 5 discusses theoretical implications and managerial recommendations. Section 6 concludes with reflections on limitations and directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background: Technology–Organization–Environment Framework and the Zero Trust Paradigm

In a dynamic, digitized, and risk-prone environment, organizations are increasingly compelled to adopt security architectures that go beyond traditional perimeter-based models. One such paradigm, ZT, fundamentally redefines the security posture by emphasizing explicit and continuous trust verification over implicit trust assumptions [4,10]. As enterprises confront the rising complexity of cybersecurity threats [16,25], the ZT paradigm requires rethinking not only technical infrastructures but also organizational and environmental responses. The Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework [22] offers a robust lens for examining the multifaceted influences on ZT adoption, making it a relevant and flexible theoretical foundation for this study.

The TOE framework identifies three core contexts that shape the adoption of technological innovations: technological, organizational, and environmental domains. Rather than viewing technology adoption as deterministic, TOE emphasizes the nonlinearity and socio-technical dynamics inherent in enterprise decision-making [26,27]. It acknowledges that adoption decisions are not merely technical judgments but are influenced by the alignment of new technologies with organizational capacity and environmental pressures [24,28]. TOE’s strength lies in its adaptive and evolutionary nature, as it continues to evolve through applications in new technological contexts [29,30], making it especially relevant for emerging paradigms such as ZT. Zero Trust thus represents an evolutionary test case for TOE, shifting the framework from explaining the adoption of technological innovations to accounting for the adoption of organizational security paradigms that require sustained cultural transformation and regulatory adaptation.

Intertwining TOE and Zero Trust: A Multi-Contextual View

The Zero Trust paradigm, while primarily conceptualized as a technological security model [4,5], represents a strategic and organizational transformation [1]. Its implementation involves new policies, cultural shifts, and infrastructure realignments that align well with the TOE’s triadic structure:

(i) From the technological perspective, ZT is embedded in a sophisticated ecosystem that includes multifactor authentication, microsegmentation, encryption, and continuous monitoring [5,15,31]. ZT’s emphasis on seamless integration and context-aware controls resonates with TOE’s focus on perceived simplicity and performance expectancy [26,32]. Importantly, it is the perception of complexity or simplicity—rather than the absolute technical difficulty—that drives adoption outcomes [33,34]. Organizations evaluate whether ZT integration reduces uncertainty and aligns with existing processes, and perceptions of excessive complexity may delay or even block adoption.

(ii) From the organizational perspective, ZT adoption requires strong top management support, cultural readiness, and adequate resource allocation [1]—all of which are critical factors in the TOE framework [35,36]. Firms with large operational scopes and mature digital infrastructures are more likely to possess slack resources and institutional support to engage in the structural transformation that ZT demands [37,38]. ZT is therefore not merely a technical upgrade but a strategic realignment that depends on managerial cognition, organizational culture, and change-management capacity [14,19]. Strategic commitment to ZT should thus be understood within the organizational domain, as it reflects managerial priorities and decision-making rather than a purely technological attribute.

(iii) From the environmental perspective, the rise of ZT is closely tied to external pressures, including regulatory requirements, client demands for stronger security guarantees, and competitive dynamics—elements directly addressed by the environmental dimension of TOE [39,40]. Normative and mimetic pressures, such as compliance mandates or influential competitors’ strategies, catalyze ZT adoption [11,41]. Additionally, increasing regulatory scrutiny around data protection and breach-response protocols strengthens the appeal—and, in many cases, the necessity—of adopting proactive security models such as ZT [42,43].

A critical nuance concerns the role of governance, which can be conceptualized in two complementary ways. On one hand, governance and compliance structures are internal organizational processes and outcomes of ZT adoption, reflecting how enterprises institutionalize security practices, strengthen accountability, and enhance resilience. On the other hand, governance also operates as an external environmental driver, since regulatory frameworks, industry standards, and stakeholder expectations impose governance requirements that organizations must satisfy to maintain legitimacy. Because of this duality, this study conceptualizes governance as an organizational outcome rather than an environmental factor, allowing it to be measured as a tangible result of effective ZT implementation while still acknowledging that many of its requirements are environmentally driven. This dual interpretation aligns with recent calls in information-systems research to treat governance as both an endogenous construct shaped by organizational choices and an exogenous pressure stemming from institutional environments [11,44]. Accordingly, governance is modeled as a dependent variable in this study, reflecting the organizational consequences of adopting ZT practices.

The integration of the TOE framework with the ZT paradigm offers a holistic theoretical perspective that extends beyond technological determinism. It enables a richer exploration of how organizational and environmental contingencies shape security-innovation adoption. For instance, while ZT requires granular access controls and dynamic trust mechanisms [44], its effective deployment depends on managerial commitment, organizational culture, and industry alignment—factors that TOE aptly captures. Furthermore, drawing from institutional theory embedded in the environmental context of TOE, organizations often adopt ZT not only out of internal necessity but also due to external legitimacy pressures [45,46]. Applying the TOE framework to the ZT paradigm thus enables a multidimensional and recursive understanding of the adoption process—one that captures the technical robustness, organizational feasibility, and environmental viability required for Zero Trust architectures to be fully realized in complex enterprise ecosystems.

Table 1 below summarizes this multi-contextual integration between the TOE dimensions and the governance roles emerging in ZT adoption, illustrating how technological, organizational, and environmental factors jointly shape security-governance outcomes.

Table 1.

Mapping TOE Dimensions and Governance Roles in ZT Adoption.

In sum, while the TOE framework traditionally explains technology adoption, this study extends its scope to security-innovation contexts, where technology is not merely a tool but a governance mechanism shaping organizational accountability and trust relations. In the context of ZT, the organizational and environmental dimensions interact in a recursive, rather than linear, way—regulatory pressures shape governance structures, which in turn redefine organizational readiness and cultural alignment. This recursive interpretation refines TOE by introducing a governance-feedback loop that links environmental legitimacy pressures with internal control mechanisms.

3. Conceptual Model and Hypothesis Development

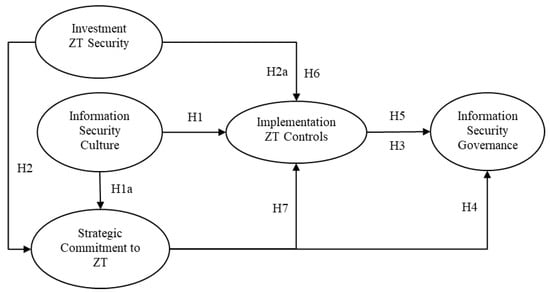

Understanding the drivers of ZT implementation requires more than identifying isolated factors; it demands a nuanced examination of how cybersecurity capabilities interact to shape security outcomes. While prior studies have established the relevance of organizational culture, investment, and compliance in shaping ZT adoption [1], this study extends that foundation by investigating not only direct effects, but also how and under what conditions these factors influence ZT implementation and governance performance. Specifically, this research captures both mediating mechanisms—such as the way implementation translates investments and culture into improved governance—and moderating dynamics, where the cultural context strengthens or weakens the impact of strategic intent. Such an approach aligns with calls for richer explanatory models that recognize the contingent and processual nature of innovation adoption [50,51]. By unpacking these layered relationships, the study offers a more integrative understanding of the conditions under which ZT is effectively deployed and governed in organizational settings. Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical research model, grounded in the TOE framework, capturing the direct, mediating, and moderating effects among organizational, technological, and environmental factors in adoption of ZT. The model highlights how Information Security Culture and Investment in Zero Trust Security directly influence Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls, how Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust mediates these effects, and how Information Security Culture moderates the translation of strategy into execution. We develop our hypotheses step by step in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model. In this study, governance is modeled as an organizational outcome of Zero Trust implementation. While governance requirements often originate from environmental pressures (e.g., regulations, industry standards), we conceptualize it as the measurable internal result of adoption, reflecting the organizational consequences of ZT practices. Source: Authors’ Own Creation.

3.1. Direct Effects

Organizational culture plays a foundational role in shaping how institutions respond to technological innovations [48]. Information security culture can be defined as the shared values, norms, and practices within an organization that influence employee behaviors and managerial decisions regarding the protection of information assets [1]. It reflects the degree to which security is internalized as a collective organizational priority rather than imposed solely through compliance mechanisms. In the context of ZT—where traditional security assumptions are replaced by principles such as continuous verification, least privilege, and adaptive access control—a culture that values security, accountability, and change readiness becomes critical [52]. Within the TOE framework, culture is captured under the organizational context, representing the internal norms, values, and behavioral expectations that influence the adoption of innovation [32].

A robust security culture creates a climate in which employees and leaders recognize cybersecurity as a shared organizational value [53]. This includes cultivating awareness of security threats, fostering a proactive mindset toward risk mitigation, and maintaining a commitment to compliance and continuous improvement [54]. These cultural attributes directly support the operationalization of ZT principles, which require organizations to continuously evaluate access permissions, minimize trust boundaries, and maintain high levels of accountability across systems and users [55]. In such environments, the implementation of ZT is more likely to be both technically successful and behaviorally reinforced. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Organizations with a robust security culture are more likely to implement Zero Trust controls effectively.

Culture does not only influence how technologies are implemented; it also shapes how strategic priorities are defined. Strategic commitment to Zero Trust (ZT) refers to the organization’s conscious and deliberate prioritization of ZT principles within its overarching cybersecurity vision, encompassing leadership intent, long-term planning, and the integration of ZT into enterprise-wide security policies [1,7]. When security is embedded in an organization’s shared values, leaders are more likely to prioritize long-term cybersecurity investments and align their strategic objectives with frameworks such as ZT [56]. Strategic alignment with ZT involves recognizing the need to transition from reactive security postures to proactive, trust-minimization architectures [3,5]. Cultures that emphasize resilience, continuous learning, and cross-functional collaboration provide the social and institutional foundation for such strategic shifts [57]. Within the TOE framework, this reflects how internal norms and beliefs shape strategic orientation toward technology adoption [26]. Organizations with weak or compliance-driven cultures may implement ZT under regulatory pressure but fail to embed its principles into strategic thinking, leading to fragmented or symbolic adoption. In contrast, when culture supports innovation and risk-aware thinking, strategy formation is more likely to incorporate comprehensive ZT objectives [1], such as architectural redesign, sustained investment in authentication infrastructure, and policy integration. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1a.

Organizations with a strong information security culture are more likely to align their strategy effectively with Zero Trust principles.

Effective adoption of the ZT paradigm requires organizations to commit both strategically and operationally to the transformation of their security infrastructure [58]. At the center of this transformation lies investment in ZT security, defined as the allocation of financial, technological, and human resources directed toward developing and sustaining cybersecurity capabilities—particularly those aligned with ZT principles [1,38,59]. Within the TOE framework, investment reflects a key dimension of the organizational context, representing the firm’s readiness to innovate, its absorptive capacity, and its willingness to allocate resources toward long-term technological transformation [38,60].

Organizational investment not only provides the means to procure new technologies but also serves as a strategic signal [61]. When firms make deliberate and sustained investments in cybersecurity, they demonstrate heightened awareness of digital risks and a proactive orientation toward resilience [62]. These investments often precede or accompany the formulation of comprehensive security strategies, such as the adoption of ZT principles, which require a departure from perimeter-based security thinking toward an architecture centered on explicit and continuous trust evaluation [52,63].

Strategic commitment to ZT entails more than technology deployment; it requires architectural redesign, long-term planning, policy overhaul, and organizational alignment [1]. Organizations that invest early and substantially in cybersecurity are more likely to develop strategic intent around ZT, as investment reflects both prioritization and capability—two prerequisites for robust strategic engagement [39,64]. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

Higher organizational investment in ZT security increases the likelihood of developing its strategic commitment.

Beyond its strategic signaling function, organizational cybersecurity investment also plays a direct operational role in enabling ZT implementation [20,59]. ZT implementation refers to the extent to which organizations operationalize ZT principles—such as continuous authentication, microsegmentation, identity and access management, encryption, and behavioral analytics—into their security architecture, policies, and day-to-day practices [1,5,43]. Deploying ZT requires a complex array of technologies, including identity and access management systems, microsegmentation tools, behavioral analytics, continuous monitoring platforms, and encryption frameworks [5,31,43]. These technologies cannot be deployed effectively without adequate resources. Therefore, the level of investment directly influences an organization’s ability to implement ZT controls in a comprehensive and sustainable manner.

Within the TOE framework, this relationship reflects the importance of resource availability as a driver of technology adoption [22]. Investment enables firms to overcome operational barriers such as outdated infrastructure, limited technical skills, and integration complexity [65,66]. Furthermore, financial commitment allows for the phased adoption and scaling of ZT technologies across diverse systems and user environments, ensuring that implementation is not symbolic or fragmented but embedded and continuous [1]. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2a.

Organizational investment in ZT security directly facilitates its implementation.

The successful implementation of the ZT paradigm is also a foundational component of broader governance and compliance frameworks [11]. Information security governance is defined as the set of structures, processes, and practices through which organizations direct and control their security efforts, ensuring alignment with regulatory requirements, organizational objectives, and stakeholder expectations [44,67]. As organizations transition toward dynamic and identity-aware security models, ZT becomes instrumental in supporting enterprise-wide efforts to enhance accountability, enforce policy compliance, and mitigate risk [68]. Within the TOE framework, the implementation of new technologies—when well-integrated—enables organizations respond more effectively to environmental demands and institutional pressures, particularly those related to regulation, audit, and compliance [22,69].

The ZT paradigm, by design, promotes continuous verification, least-privilege access, and granular policy enforcement—principles that align closely with governance mechanisms aimed at ensuring that systems operate within defined security parameters [5,70]. Empirical studies have shown that security architectures capable of segmenting network access, verifying identities dynamically, and auditing user activity not only reduce the risk of internal and external threats but also support organizations in meeting regulatory standards and strengthening risk management systems [6,52,71]. These functions are central to modern governance structures, where compliance is increasingly data-driven and enforced through real-time control systems.

From the TOE perspective, effective implementation of ZT represents the technological context interacting with environmental expectations (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA, or industry-specific mandates), allowing firms to operationalize regulatory requirements and enhance transparency in data access and handling processes [11,43,49]. ZT frameworks thus act as technical enablers of governance by embedding verification, traceability, and control mechanisms into core information systems (IS). Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

The effective implementation of Zero Trust enhances organizational security governance.

In parallel, organizational efforts to implement ZT principles often begin at the strategic level. Strategic commitment represents the organization’s conscious decision to prioritize ZT principles within its overarching cybersecurity vision. This includes allocating resources, revising architectural blueprints, and integrating ZT concepts into enterprise-wide security policies [7,52]. According to the TOE framework, strategic intent—part of the organizational context—is a key determinant of successful adoption, as it aligns leadership vision, resource mobilization, and execution priorities [64,69]. Organizations that articulate a clear ZT strategy are better positioned to move from fragmented or reactive security measures to fully integrated ZT architectures [72].

This alignment between strategic planning and operational deployment enables smoother implementation of technical controls such as multifactor authentication, access segmentation, and behavioral analytics [15,31]. Furthermore, research in information systems adoption underscores the importance of top-down alignment, where leadership vision and enterprise strategy drive technological change at scale [73,74]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.

Organizational commitment to a Zero Trust strategy drives the effective implementation of its principles and controls.

3.2. Mediation Effects

In the context of cybersecurity transformation—particularly the adoption of paradigms such as ZT—understanding how and through what mechanisms organizational factors affect governance outcomes is critical. Mediation analysis offers a way to uncover these underlying processes. Rather than viewing the relationship between organizational culture or investment and governance as direct and linear, mediation enables a more nuanced understanding by recognizing the implementation of ZT as the intervening mechanism that translates inputs into outcomes. This is especially relevant in cybersecurity, where strategy or values alone do not suffice—success depends on how these are embedded into systems, policies, and operational practices. The relevance of mediation in information systems (IS) research is well established, with scholars highlighting that the success of complex technological initiatives often hinges on intervening implementation behaviors [75,76]. Within the TOE framework, such mediators represent the dynamic interplay between the organizational context (e.g., culture, resources) and environmental outcomes (e.g., governance, compliance) [77].

A strong security culture is often regarded as foundational to cyber resilience [78]. However, its effects are not automatically realized. A culture that emphasizes awareness, accountability, and adaptability must still be translated into action—particularly through the implementation of security architectures that embody those values [79,80]. ZT implementation serves as that bridge: organizations with robust cultures are more likely to embed security-conscious behaviors and support structures that facilitate the adoption of verification-based models [55]. Research in IS confirms that the pathway from values to outcomes is frequently mediated by how effectively those values are enacted through technology and processes [81,82]. As such, the benefits of security culture on governance and compliance materialize only when ZT practices are actively implemented. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H5.

The influence of information security culture on governance outcomes is mediated by the implementation of Zero Trust controls.

Similarly, organizational investment in cybersecurity—while crucial—does not guarantee improved governance performance. Resources must be strategically deployed and operationalized through implementation activities that align with the principles of Zero Trust (ZT) (e.g., segmentation, access control, real-time analytics). Prior research in IT adoption has shown that financial commitment enhances technological performance only when coupled with effective deployment and user engagement [83,84]. In this light, implementation functions as the mechanism through which investment generates returns in the form of resilience, compliance, and oversight. From a TOE perspective, investment represents organizational readiness, but it is implementation that determines whether that readiness is translated into technological value realization [77]. Without a mature implementation phase, investments may be underutilized or fail to respond adequately to evolving threats and regulatory mandates [85]. Recent studies have demonstrated that implementation quality mediates the effects of IT resources on firm-level outcomes such as process maturity, auditability, and risk mitigation [14,86]. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H6.

Investment in Zero Trust security positively influences information security governance through the mediating role of Zero Trust implementation.

By conceptualizing ZT implementation as a mediating construct, this study contributes to a more layered understanding of how internal organizational factors produce meaningful security and governance outcomes. It emphasizes that performance gains in security contexts emerge not merely from having resources or values in place but from how these elements are operationalized through structured, principle-driven architectures such as ZT.

3.3. Moderation Effects

In this study, moderation represents the conditional influence of information security culture on the strength of the relationship between strategic commitment to ZT and its implementation, highlighting how internal cultural factors can amplify or weaken strategic execution. A strong security culture fosters shared values, norms, and behaviors that align employees’ actions with organizational cybersecurity objectives [53,54]. In the context of ZT—where the paradigm demands a shift from implicit trust to continuous verification and role-based access—cultural readiness becomes a critical enabler of change acceptance and policy compliance [19,78].

From the perspective of the TOE framework, culture is a key organizational determinant that shapes how strategic decisions are internalized and translated into practice [22,26]. Organizations with a well-established culture of security awareness and accountability are more likely to exhibit the behavioral and procedural alignment necessary to implement ZT strategies effectively [55]. Thus, the relationship between strategic commitment to ZT and the implementation of its principles is not uniform across organizations—it is conditioned by the degree of cultural alignment.

Accordingly, we posit that security culture moderates the relationship between strategic commitment to ZT and its implementation, such that organizations with a robust security culture are better equipped to translate strategic intent into operational outcomes. This interaction effect highlights the integrative role of cultural readiness in shaping cybersecurity execution, further enriching the TOE framework’s explanatory power in security-innovation contexts. This leads to the final hypothesis in our model:

H7.

The relationship between strategic commitment with Zero Trust and its implementation is moderated by information security culture, such that the effect is stronger in organizations with a robust security culture.

In summary, this study integrates the TOE framework with the ZT paradigm to explain how organizational and technological factors jointly shape governance performance in cybersecurity contexts. The conceptual model (Figure 1) posits that information security culture and investment in ZT security serve as organizational enablers influencing both strategic commitment and technical implementation, while ZT implementation functions as the mediating mechanism through which these enablers improve information security governance. The model further introduces a moderating effect of culture, emphasizing that a robust security culture strengthens the translation of strategic intent into operational outcomes. Collectively, these relationships extend the TOE framework to the domain of security innovation by conceptualizing governance not only as an organizational outcome but also as a reflection of environmental accountability.

Building on this conceptual foundation, the following section details the research design and methodological approach employed to empirically test these hypotheses through a sequential mixed-methods strategy combining qualitative exploration and quantitative validation.

4. Methodological Approach

To investigate our research model, we employed a sequential mixed-methods design, integrating both qualitative and quantitative techniques within a single study [87,88,89]. Mixed-methods research is characterized by the deliberate combination of distinct methodological approaches to deepen and broaden the understanding of a phenomenon [90]. Among the various configurations of mixed methods, we adopted a sequential explanatory strategy, in which the qualitative component complements and contextualizes the quantitative findings. Specifically, we first collected survey data to test the theoretical model, followed by in-depth interviews to explore the underlying dynamics and interpretations.

The integration of both data types enables methodological triangulation, reinforcing the robustness of the findings by cross-validating results across multiple sources [90]. In line with established guidelines, the qualitative insights were used to elaborate and interpret the patterns identified in the quantitative phase, thereby enhancing both the credibility and depth of the overall analysis.

4.1. Quantitative Method: Survey Design and Data Collection

To test the research model illustrated in Figure 1, a large-scale survey was conducted among information security professionals from diverse industries and regions. The instrument was developed using constructs validated in prior information systems and cybersecurity research [17,21,56,58,70,91,92] and was approved by the institutional ethics committee in compliance with human-subjects research protocols [87,88].

Data were collected between January and June 2024. Invitations were distributed via personalized emails containing unique survey links. The sampling frame consisted of 1864 cybersecurity experts identified on LinkedIn based on their professional profiles. Participation was voluntary and uncompensated, minimizing response bias. Before full deployment, a pretest with 40 cybersecurity experts confirmed item clarity and face validity, and no revisions were required. In total, 301 responses were received. After excluding incomplete submissions, responses with extremely short completion times, and inconsistent patterns, 267 valid responses remained, yielding an effective response rate of 14.32% (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic information of the sample.

Nonresponse bias was evaluated by comparing early and late respondents across key demographics and construct means, and no significant differences were found (p > 0.05). These results suggest that attrition did not materially affect the representativeness of the final sample, although generalization should be limited to similar professional populations rather than to the broader workforce.

Respondents represented a wide range of organizational sizes and sectors (finance, healthcare, manufacturing, technology, and public administration) as well as geographic locations, providing a heterogeneous sample suitable for examining the generalizability of ZT implementation factors.

4.1.1. Operationalization of Constructs

All latent variables were modeled reflectively and measured using multi-item scales adapted from validated instruments [1,53,55,72]. Appendix A (Table A1) presents the complete measurement instrument. Each construct was conceptually defined and operationalized to capture its behavioral, organizational, and technological manifestations.

- Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust: The degree to which an organization aligns its security vision, planning, and governance priorities with ZT principles. It reflects strategic intent, awareness of business implications, prioritization of technical requirements, and the formal integration of ZT initiatives (e.g., “My company currently has a defined Zero Trust security initiative.”)

- Information Security Culture: The shared values, norms, and behaviors that shape collective commitment to information protection. It assesses how security best practices are embedded in daily routines and internalized as organizational norms rather than enforced solely through compliance (e.g., “At my company, best practices in information security are the accepted way of doing business.”)

- Investment in Zero Trust Security: The tangible and intangible commitments enabling ZT adoption, including financial capacity, technological modernization, and human-resource development (e.g., “My company invests in Zero Trust architecture.”)

- Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls: The extent to which technical mechanisms translate ZT principles into practice—such as multifactor authentication, contextual access control, network segmentation, and modernization of legacy systems (e.g., “My company employs multifactor authentication for external users and employees.”)

- Information Security Governance: The policies, compliance routines, and accountability structures that institutionalize ZT practices. Items capture risk reporting, communication of governance updates, and alignment with governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) functions (e.g., “My company provides timely risk management updates to GRC stakeholders.”)

All items used a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Construct reliability and validity were assessed through indicator loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and discriminant-validity analyses, confirming the robustness of the measurement model for replication.

4.1.2. Assessment of Common-Method Bias (CMB)

To mitigate potential common-method variance, respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality and were instructed to answer based on organizational practices observed during the previous 12 months. Item randomization was implemented through the Research.net platform to minimize ordering effects [90].

In addition to these procedural remedies, two quantitative tests were conducted. First, Harman’s single-factor test was performed using unrotated principal-axis factoring across all measurement items to assess whether a single latent factor dominated the variance [93]. Second, full collinearity variance-inflation factors (VIFs) were computed for each latent variable in SmartPLS [94,95]. These complementary procedures are widely recommended in PLS-SEM research to ensure that common-method variance does not bias model estimates [95,96].

4.1.3. Method Application

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was conducted using SmartPLS 4 [97,98]. Both the measurement and structural models were assessed in accordance with established guidelines [93,99].

For the measurement model, indicator loadings were evaluated via bootstrapping (target > 0.70), internal consistency via Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR; 0.70–0.95), convergent validity via AVE (>0.50), and discriminant validity via the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio (<0.85–0.90). Nomological validity was confirmed within the theoretical framework, and predictive validity was assessed using Q2 (cross-validated redundancy) and f2 (effect size) metrics, where Q2 > 0, 0.25, and 0.50 indicate small, medium, and large predictive relevance, respectively. Collinearity was examined using VIF (<3.0), and R2 values were reported for all endogenous constructs.

To control potential endogeneity, the Gaussian Copula (GC) method proposed by Park and Gupta [95] was applied. This nonlinear transformation detects whether explanatory variables correlate with model error terms, which could bias path estimates. Non-significant copula terms indicate that endogeneity does not affect the corresponding relationships, thereby increasing causal robustness [94,95].

PLS-SEM is well suited for complex models involving mediation and moderation, and sample-size requirements were determined using multiple-regression power heuristics [95,100,101,102]. Using α = 0.05 and a target power of 0.80, benchmarks indicate that detecting a medium effect (f2 = 0.15) with up to five predictors (our most complex specification, including the interaction term) requires N ≈ 92, while detecting a large effect (f2 = 0.35) requires N ≈ 52 [101]. The final sample of N = 267 thus comfortably exceeds these thresholds, ensuring adequate power for both mediation (bootstrapped indirect effects) and moderation analyses.

The interaction term (Information Security Culture × Strategic Commitment to ZT) was modeled using the product-indicator approach with mean-centered indicators, as implemented in SmartPLS. Mean-centering minimizes multicollinearity between the latent predictors and their interaction term, providing unbiased estimates of the moderation effect within the PLS framework [93,95,99].

4.2. Qualitative Method: Interview Design and Data Analysis

To enrich and contextualize the findings from the quantitative phase, we conducted a qualitative study grounded in an interpretivist paradigm and informed by ontological pragmatism, which emphasizes the practical construction of meaning through experts’ perspectives [103]. Given the emergent and complex nature of ZT in organizational information security, a qualitative approach was essential to uncover the nuanced challenges, contradictions, and contextual mechanisms that shape ZT adoption [103,104,105].

We conducted 27 semi-structured interviews with information-security professionals across multiple sectors, employing purposeful sampling to initially target senior-level executives (e.g., CISOs, CIOs, IT Directors) with direct oversight of security strategies. Snowball sampling was subsequently used to capture a broader spectrum of perspectives across managerial, operational, and advisory roles, thereby ensuring both strategic- and implementation-level viewpoints [106,107]. Interviews averaged approximately 32 min in length and continued until data saturation was reached, consistent with prior literature [108].

All but one interview were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; in one case, due to privacy concerns, the participant provided written responses. Participants were fully informed of the study’s scope, confidentiality procedures, and the voluntary nature of participation prior to data collection. A flexible interview guide was developed to explore core themes while accommodating emergent insights and sensemaking narratives that surfaced during the conversations. Table 3 summarizes participant demographics and organizational affiliations.

Table 3.

Interviewees Information.

In mixed-methods research, the generation of inferences often stems from the reciprocal integration of quantitative findings with qualitative insights, whereby statistical relationships among variables are interpreted through participants’ subjective experiences, rationales, and institutional contexts [89,90]. Accordingly, the qualitative phase in this study was not designed merely to confirm survey results but to explain, reinterpret, and extend them by uncovering the organizational processes through which ZT principles are enacted—or resisted—in practice.

The qualitative data analysis was guided by established interpretive procedures. Anchored in the TOE framework, we translated the latent variables examined in the quantitative phase into initial analytical categories—referred to by Miles and Huberman [109] as “intellectual bins”—which served as coding anchors. These predefined categories structured the initial round of thematic analysis of the interview transcripts. However, the analysis also incorporated inductive coding to capture emergent subthemes—such as leadership alignment, institutional resistance, symbolic compliance, and trust negotiation—that provided deeper interpretive insights beyond the original constructs.

To reinforce and expand upon the quantitative findings, which examined relationships among organizational, technological, and environmental factors, we applied axial coding to link these themes and identify cross-cutting mechanisms connecting strategy, culture, and governance. This iterative integration ensured that the qualitative data not only supported or challenged the hypotheses tested in the structural model but also revealed how and why these relationships materialize in organizational contexts. In this way, the qualitative phase contributed to theory building by clarifying the socio-cultural and institutional conditions under which the statistical relationships observed in the quantitative analysis hold true or become attenuated.

Coding Reliability and Validation Procedures

To ensure the credibility and reliability of the qualitative coding process, we employed an iterative and collaborative validation procedure rather than relying solely on quantitative inter-coder statistics. The first author developed the initial coding framework inductively based on repeated readings of the interview transcripts, following open and axial coding procedures consistent with grounded theory principles. The second author independently reviewed approximately one-third of the transcripts and applied the emerging codebook to assess conceptual alignment and coding consistency.

Discrepancies in code interpretation were discussed during reflexive consensus meetings with two additional independent researchers, during which both coders compared excerpts, refined category boundaries, and merged semantically overlapping codes. This process continued until full agreement was achieved across all thematic categories. The final codebook thus reflects a consensual validation approach, emphasizing interpretive convergence over numerical agreement measures.

To further enhance dependability, all coding decisions and analytical memos were systematically documented in an audit trail, ensuring transparency in how analytical themes evolved from the raw data. This triangulated validation process ensured that the final thematic structure accurately represented experts’ perspectives on ZT adoption and implementation challenges.

5. Findings

The following section presents the results of the quantitative analysis. It begins with an evaluation of the measurement model’s validity and reliability, followed by a description of the analytical procedures used to test the hypotheses. Finally, the results of the hypothesis testing are reported.

5.1. Quantitative Results

All measurement instruments demonstrated strong internal consistency reliability, with Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70 [93] (Table 4). Convergent validity was established for all constructs, as the average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.591 to 0.805, surpassing the 0.50 criterion.

Table 4.

Reliability, Convergent Validity, and Discriminant Validity (Fornell-Larcker Criterion and Correlations.

Discriminant validity was confirmed through two complementary tests. First, the Fornell–Larcker criterion [98] indicated that the square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its correlations with other constructs. Second, all heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratios [95] fell below the conservative threshold of 0.85 (Table 5), confirming empirical distinctiveness among the constructs. All indicator loadings exceeded 0.70 and were statistically significant (p < 0.001), reinforcing indicator reliability and the robustness of the measurement model.

Table 5.

HTMT ratios.

Multicollinearity diagnostics indicated that all variance inflation factors (VIFs) were below 5.0 (maximum = 3.3), confirming the absence of critical collinearity issues. The complete set of measurement indicators is provided in Appendix A (Table A1).

Tests for common-method bias (CMB) confirmed that it did not pose a threat to the validity of the results. Harman’s single-factor test revealed that the first factor explained less than 50% of the total variance, while all full collinearity VIFs were ≤3.0, below the conservative threshold of 3.3 [94].

Although the SRMR value (0.102) slightly exceeded the conventional 0.08 cut-off, such values are acceptable for complex PLS-SEM models that include multiple mediators and moderators [95,99]. Examination of the cross-loading matrix (Appendix A, Table A2) confirmed that all indicators loaded highest on their intended constructs, with cross-loadings at least 0.20 lower, thus ruling out redundancy or misspecification. Complementary fit indices (d_ULS = 1.768; d_G = 0.489; NFI = 0.815; χ2 = 660.719) further supported satisfactory global model fit.

Structural model significance and precision were evaluated through bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples (two-tailed, α = 0.05), following Hair et al. [93]. Effect sizes (f2) were computed to assess the practical relevance of each exogenous construct in explaining its respective endogenous variable. Information Security Culture exerted medium-sized effects on both the Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls (f2 = 0.141) and Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust (f2 = 0.148), underscoring its substantive role in fostering organizational readiness and strategic alignment with Zero Trust principles. The interaction term (Information Security Culture × Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust) produced a very small effect (f2 = 0.014), consistent with the marginal moderation observed in the structural analysis and suggesting that cultural strength slightly conditions the influence of strategic intent on technical outcomes.

The Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls demonstrated an exceptionally large effect on Information Security Governance (f2 = 1.222), reaffirming its central role as the operational mechanism translating organizational enablers into governance performance. Likewise, Investment in Zero Trust Security exhibited a large effect on Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust (f2 = 1.391) but only a small effect on Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls (f2 = 0.046), indicating that financial and technical investments contribute more to the formulation of ZT strategy than to its immediate operational realization. Conversely, the Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust → Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls path showed a negligible effect (f2 = 0.006), reinforcing that strategic vision alone—without complementary cultural and resource support—is insufficient to drive technical deployment.

Collectively, these f2 values indicate that the structural model is dominated by high-impact pathways—notably Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls → Information Security Governance and Investment in Zero Trust Security → Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust—while cultural and interactive mechanisms, though secondary, play essential enabling roles that sustain long-term adoption and governance maturity.

Predictive performance was further evaluated using the PLS-Predict procedure with 10-fold cross-validation. All Q2_predict values were positive and well above zero, confirming strong out-of-sample predictive accuracy: Q2_predict = 0.604 for Information Security Governance, 0.535 for Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls, and 0.763 for Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust. The corresponding RMSE and MAE values (0.635 and 0.506; 0.688 and 0.524; 0.490 and 0.365, respectively) demonstrate that the PLS model consistently outperformed the linear benchmark across all endogenous constructs.

5.1.1. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

Table 6 summarizes all hypothesized relationships. Consistent with H1, Information Security Culture had a strong, positive effect on the Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls (β = 0.385, p < 0.001), indicating that organizations with a stronger security culture are more effective in operationalizing Zero Trust principles. H1a was also supported (β = 0.233, p < 0.001), showing that a strong security culture enhances Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust.

Table 6.

Structural-model results: path coefficients, t-values, and significance levels.

Support was likewise found for H2 and H2a, demonstrating that Investment in Zero Trust Security positively influences both Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust (β = 0.715, p < 0.001) and Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls (β = 0.277, p = 0.002). These findings highlight the critical role of resource allocation and investment capacity in enabling both strategic planning and operational execution of ZT initiatives.

H3 received strong support (β = 0.742, t = 21.545, p < 0.001), confirming that Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls significantly enhances Information Security Governance through strengthened policy enforcement, improved risk communication, and consistent compliance routines. In contrast, H4 was not supported (β = 0.110, p = 0.223), suggesting that Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust, without supportive cultural and operational structures, is insufficient to drive technical adoption.

Mediation analyses further confirmed the central role of Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls. The construct mediated the effects of Information Security Culture on Information Security Governance (H5: β = 0.286, p < 0.001) and of Investment in Zero Trust Security on Information Security Governance (H6: β = 0.206, p = 0.003). These findings emphasize that ZT implementation functions as the operational bridge linking organizational enablers to governance outcomes.

The moderation test (H7) revealed a marginally significant interaction (β = −0.075, p = 0.081), indicating that a strong Information Security Culture may attenuate the effect of Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust on the Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls—possibly due to misalignments between formal strategic directives and deeply embedded organizational practices.

The adjusted R2 values show that the model explains 54.8% of the variance in Information Security Governance, 55.1% in the Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls, and 76.6% in Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust, reflecting moderate to substantial explanatory power. Overall, these findings reaffirm the centrality of technical implementation in realizing the benefits of Zero Trust and validate the TOE framework as an effective lens for understanding the organizational and technological enablers of cybersecurity innovation.

5.1.2. Robustness and Endogeneity Assessment

Potential endogeneity and distributional biases were examined using the Gaussian Copula (GC) approach [104,105]. None of the copula terms reached statistical significance at p < 0.05—for instance, the paths from Information Security Culture to the Technical Implementation of Zero Trust Controls (p = 0.704) and from Investment in Zero Trust Security to Strategic Commitment to Zero Trust (p = 0.389) were non-significant—indicating that the structural relationships are not biased by endogeneity.

As clarified by Hair et al. [104] and Hult et al. [105], non-significant GC terms confirm the absence of endogeneity, thereby supporting the causal interpretation of the PLS-SEM results. The consistent PLS (PLSc) algorithm [95,106] was additionally applied to correct for potential attenuation bias in reflective constructs. Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was employed to ensure distributional stability and robustness.

Together, these robustness tests confirm that endogeneity and non-normality do not compromise the validity of the structural model or the reliability of the estimated path coefficients.

5.2. Qualitative Results

The qualitative phase deepened and contextualized the statistical findings by uncovering how organizational actors interpret, negotiate, and enact the ZT paradigm in practice. Regarding direct effects, the qualitative results substantiated and expanded the quantitative evidence on the critical role of organizational culture and investment in driving ZT implementation.

Numerous participants emphasized that fostering a strong security culture is foundational to successful implementation and trust realignment. One interviewee remarked, “The cultural impact, I think, is the main impact you have within any security principle” (ID1), while another noted, “The IT culture itself. I talked about the impact on users, budget, investments, and the IT culture itself” (ID7). These perspectives highlight that a security-oriented mindset must permeate organizational routines to overcome resistance and support ZT execution. Interview narratives also revealed “symbolic compliance” patterns—instances where formal controls were implemented without genuine behavioral change—illustrating the gap between technical enforcement and cultural assimilation. A third interviewee underscored this challenge, stating, “Cultural aspects are extremely important from the point of view of trust” (ID22).

With respect to investment, participants consistently identified resource allocation as a key enabler of ZT adoption, encompassing not only financial capacity but also long-term planning and upskilling. For instance, one professional stated, “I think that any company has a barrier… which is the investment in security. In other words, security is not cheap, it never was and never will be” (ID1). Another echoed this view, explaining, “The financial issue in terms of architecture… I think it is essential to be able to implement zero trust” (ID20). Several respondents further described investment as a form of organizational signaling to employees and partners, reinforcing the enterprise’s security commitment. Training and professional development were equally prioritized, with one interviewee emphasizing, “The training of professionals. Having a trained professional who understands the concept and who can overcome these first two barriers, which is to make management aware and to prepare the environment technologically” (ID5). Together, these accounts show that culture and investment interact recursively: financial commitment legitimizes security as a shared organizational value, while a mature culture ensures that such investments translate into behavioral change.

Turning to the mediation effects, the data suggest that ZT implementation acts as a bridge between organizational conditions (such as culture and investment) and governance outcomes. Interviewees explained that tangible improvements in policy compliance, control enforcement, and risk communication only emerge when implementation is thorough and iterative. For example, one participant explained, “Today the company already has a policy… in fact, we are currently readjusting the policies for a higher level of the zero trust, to make it even more stratified” (ID9). Another elaborated, “From the moment you apply an information security policy, you start working with encrypted data, the employees’ access itself requires authentication, depending on where you are working, you need to have an even higher level of security” (ID12). These accounts illuminate the mechanism underlying the mediation effect identified in the model: implementation operationalizes strategic intent and converts cultural and financial readiness into measurable governance outcomes.

Finally, in relation to the moderation effect, qualitative data provide strong evidence that security culture influences the strength and durability of strategic execution. Several participants noted that without a culturally embedded appreciation for security, formal strategies often fail to gain traction. As one interviewee candidly observed, “If it does not come from the top down, it is no use coming from an analyst or a specialist consultant” (ID20). Another explained, “The support of the board as a whole, because you can start at the bottom, but if you do not have people at the top setting an example and spreading the word, it does not work” (ID2). These statements emphasize the need for leadership alignment and cultural reinforcement to translate strategy into operational change. Conversely, participants described institutional resistance in environments where entrenched hierarchies or competing priorities undermined security initiatives, demonstrating how weak cultural endorsement can nullify even well-articulated strategic plans.

Beyond confirming the quantitative results, the qualitative analysis revealed deeper interpretive patterns—such as trust negotiation between employees and systems, symbolic compliance in policy enforcement, and institutional resistance to security transformation—that refine the TOE-based understanding of ZT adoption. These findings show that culture and investment are not merely contextual variables but dynamic forces that shape how ZT is enacted, contested, and sustained within enterprises. They also demonstrate that governance improvements are realized through iterative execution rather than planning alone, and that cultural embeddedness moderates the translation of strategic intent into sustained operational change.

In sum, integrating both phases produces a more interpretive and recursive view of ZT adoption, consistent with the governance-feedback loop proposed in Section Intertwining TOE and Zero Trust: A Multi-Contextual View. These results reinforce the importance of a holistic, TOE-informed approach that captures not only formal structures and technological capabilities but also informal norms, leadership dynamics, and sensemaking processes that determine implementation success.

The semi-structured interview protocol is provided in Appendix B, while Appendix C presents the qualitative evidence base through Table A3 (sample of coding scheme and representative excerpts) and Table A4 (additional quotations supporting quantitative results). These materials collectively ensure transparency and traceability of the analytical process. Because the original transcripts contain personally identifiable and organizational information, they cannot be publicly released in compliance with institutional ethics approval. Instead, the curated excerpts in Appendix C faithfully reflect the conceptual content and diversity of expert perspectives while safeguarding participant confidentiality.

6. Discussion

The integration of quantitative and qualitative evidence reveals that the adoption of ZT extends far beyond a technical reconfiguration of security architectures—it constitutes an organizational transformation shaped by cultural, strategic, and institutional dynamics. The mixed-methods design demonstrates that implementation functions as the operational bridge linking culture, investment, and governance, while security culture conditions the durability of strategic execution. Moreover, the findings refine the TOE framework by introducing a recursive governance-feedback loop, in which regulatory and environmental pressures influence internal governance structures that, in turn, reshape cultural and strategic readiness for Zero Trust. This integrative insight sets the stage for the discussion that follows, where we interpret these relationships, elaborate on their theoretical and managerial implications, and outline how organizations can cultivate the socio-technical conditions required for effective Zero Trust implementation.

This research represents an empirical effort to examine the organizational adoption of ZT as a cybersecurity strategy through an integrated mixed-methods lens. By combining quantitative survey data from a broad, cross-industry sample with qualitative insights from information-security professionals, the study develops a multilayered understanding of how organizational culture, investment, strategic alignment, and governance interrelate within the process of ZT implementation. Drawing on the TOE framework, we explore how these factors act as enablers or constraints in translating ZT principles into operational practices and institutional outcomes.

Beyond triangulating data, the integration of both phases added interpretive depth. The quantitative phase identified statistically significant relationships among culture, investment, strategy, and governance, while the qualitative analysis revealed how these relationships materialize in practice—for instance, through trust negotiation, institutional resistance, and symbolic compliance. This integration enabled a recursive interpretation of ZT adoption, illustrating that implementation success depends on both structural alignment and the socio-cultural processes that sustain organizational change.

Table 7 provides a summary of our main findings based on this multi-method investigation. In synthesizing these insights, we show that ZT adoption involves dynamic interactions between formal strategy and lived practice, where cultural readiness and leadership engagement determine the translation of technical principles into sustainable governance outcomes. In the sections that follow, we outline the theoretical contributions and practical implications of these results for IS management and cybersecurity research.

Table 7.

Summary of Findings and Implications.

6.1. Implications for Practice

The findings of this study yield several practical implications for organizations seeking to adopt the ZT security paradigm. First, the results reaffirm that ZT adoption must be approached as an enterprise-wide transformation rather than a purely technical project. Successful implementation requires alignment among strategy, culture, and investment decisions. The strong influence of organizational culture on both strategic alignment and implementation effectiveness underscores the need to cultivate a shared security mindset across all levels of the enterprise [53,55]. This includes promoting security as a core organizational value, embedding it in day-to-day operations, and aligning internal practices with risk-aware behaviors that enhance readiness for ZT transformation.

Second, while investment remains essential, our results indicate that financial resources alone do not guarantee success unless accompanied by strategic intent, managerial commitment, and coordinated execution. Prior research emphasizes that financial capacity must translate into coherent priorities, training, and measurable capability building [1,10]. Organizations should therefore view investment as a signaling mechanism of strategic seriousness—an enabler of long-term trust alignment rather than a one-time expenditure. Sustained investment in technical infrastructure, professional development, and change-management processes ensures that ZT principles are consistently operationalized across the enterprise.

Third, the study highlights that strategic alignment is a necessary but insufficient condition for successful ZT adoption. Strategy must be reinforced by a supportive culture, governance clarity, and the integration of technology into business processes. This finding aligns with the broader literature on organizational transformation, which stresses the interdependence of top-down strategic intent and bottom-up implementation capacity [24,29,39]. To achieve this, enterprises should establish governance mechanisms that facilitate cross-functional collaboration and leadership accountability, linking executive strategy with operational execution.

Fourth, the mediating role of ZT implementation between organizational inputs (culture and investment) and governance outcomes underscores the importance of execution maturity. Effective implementation enhances compliance, transparency, and risk management—key priorities for both regulators and executive leadership [6,103]. For practitioners, this means emphasizing not only the design of ZT strategies but also their iterative, data-driven deployment through technologies such as microsegmentation, identity-centric access control, and continuous monitoring. Implementation must therefore be managed as a continuous learning process, where technical outcomes inform organizational adaptation.

Finally, leaders should adopt a systems-level view of ZT transformation—one that integrates technological, organizational, and environmental considerations, as described by the TOE framework. This holistic perspective positions ZT not merely as a cybersecurity upgrade but as a governance and trust-management mechanism that strengthens institutional resilience. By embedding ZT principles within existing governance structures and cultural practices, organizations can ensure more sustainable protection against evolving threats and regulatory demands.

6.2. Implications for Theory

This study yields several theoretical implications and opens new avenues for re-search into ZT as a strategic information-security paradigm, particularly when viewed through the lens of the TOE framework [22,26]. While prior research on ZT has pre-dominantly focused on its technical architectures and control mechanisms [58,72,91], our study shifts attention to the organizational, institutional, and environmental dynamics that underpin ZT adoption and implementation. By empirically validating the roles of organizational culture, investment, and strategy, this work advances TOE theory by extending it into cybersecurity-management contexts, a domain in which it has historically been underutilized.

Specifically, the findings position ZT as a paradigm-level innovation that challenges TOE’s traditional explanatory boundaries. ZT adoption involves not only the diffusion of technical solutions but also the institutionalization of new forms of governance, accountability, and trust. Accordingly, this study refines TOE by introducing the concept of a “governance-feedback loop,” whereby environmental legitimacy pressures (e.g., regulation, client expectations) shape internal governance structures that, in turn, influence organizational readiness and cultural alignment. This recursive relationship challenges the linear interpretation of TOE and demonstrates its adaptability to complex, security-driven transformations.

In particular, the findings encourage researchers to move beyond viewing ZT as merely a configuration of technical controls. Instead, ZT should be understood as a multi-level innovation whose success depends on the interplay among organizational readiness, environmental pressures, and technological capabilities. This perspective reframes TOE as a theory of continuous adaptation, highlighting its capacity to capture the co-evolution of technological and institutional forces in security innovation. Future research could extend this approach by integrating individual-level or inter-organizational factors—such as leadership cognition, industry standards, or supply-chain influence—which are increasingly recognized as determinants of security-transformation outcomes [19,55].

Moreover, the results regarding mediating and moderating effects highlight that implementation serves as the central conduit through which strategy, culture, and in-vestment influence governance and compliance outcomes. This finding advances a more nuanced understanding of how organizational factors operate synergistically rather than independently to shape information-security performance. Researchers may build on this by employing longitudinal or multi-level designs to examine how these dynamics evolve over time, or by integrating TOE with complementary theoretical perspectives—such as Dynamic Capabilities Theory or Institutional Theory—to enrich its explanatory depth for paradigm-level transformations.

This study also offers a methodological contribution by demonstrating the explanatory value of a sequential mixed-methods design in cybersecurity research. While quantitative modeling identified significant relationships, the qualitative phase revealed behavioral, cultural, and contextual mechanisms that deepened theoretical interpretation. Such methodological pluralism enhances the theory’s external validity and encourages future IS security studies to combine statistical modeling with interpretive inquiry to better capture socio-technical complexity.

Finally, this study advances the TOE framework beyond its traditional innovation-adoption role by embedding the concepts of governance reflexivity, institutional legitimacy, and continuous verification—dimensions essential for explaining the re-cursive and trust-driven dynamics of ZT adoption. This refined interpretation positions TOE as a generative and adaptive theory for analyzing security innovations that simultaneously reshape technological systems, organizational cultures, and institutional environments, providing a comprehensive foundation for future research on socio-technical resilience.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study provides valuable insights into the organizational adoption of ZT security frameworks, several limitations must be acknowledged, as they also present opportunities for further scholarly inquiry.

First, although the quantitative component employed validated constructs adapted from prior studies [53] and refined through expert interviews, the contextual nature of ZT adoption means that measurement items—particularly those related to strategic alignment, culture, and governance—may be interpreted differently across industries or regions. Future research should aim to refine and validate these con-structs across broader and more diverse organizational samples to enhance their generalizability and measurement robustness.