Experimental Study and THM Coupling Analysis of Slope Instability in Seasonally Frozen Ground

Abstract

1. Introduction

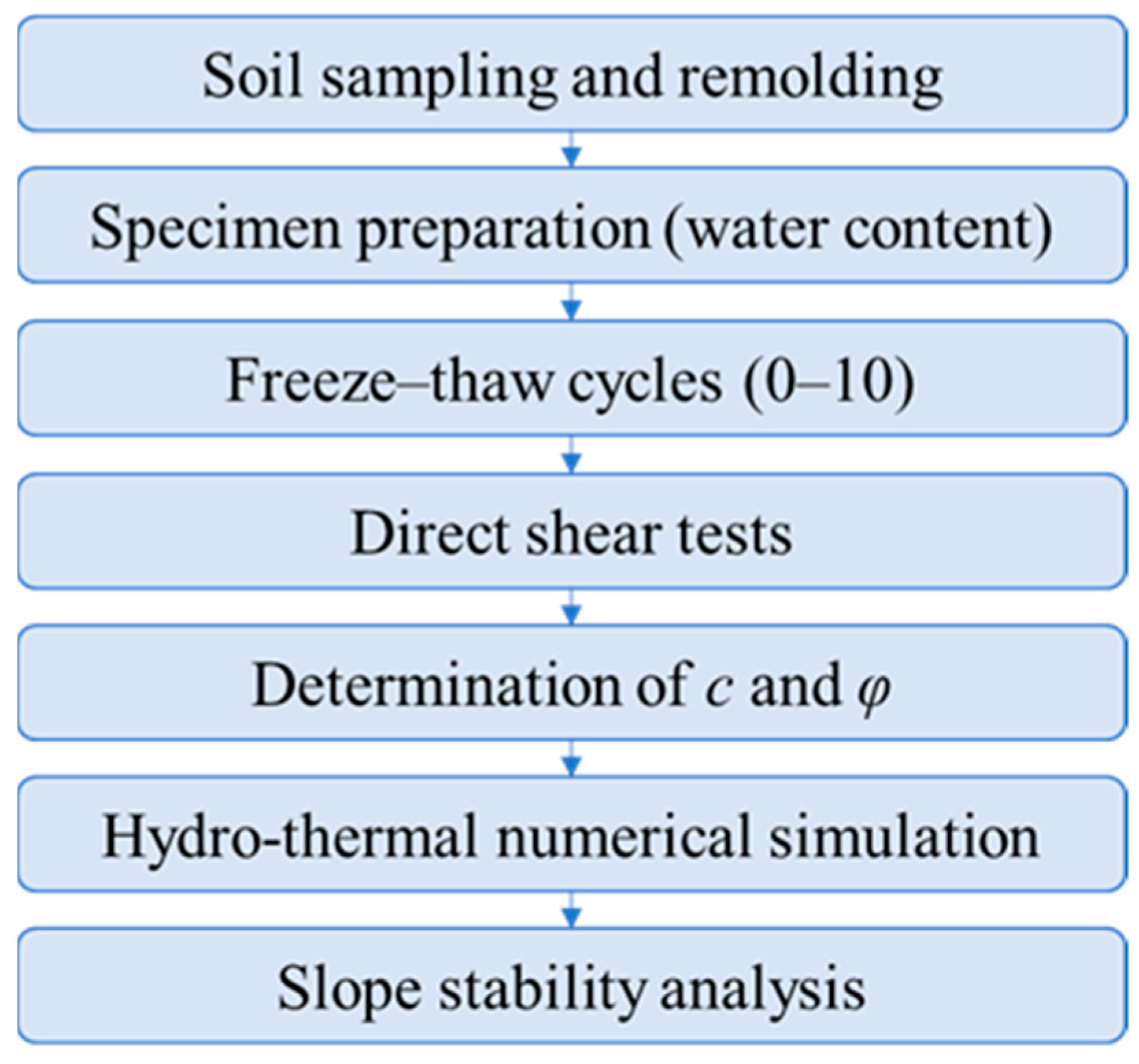

2. Materials and Methods

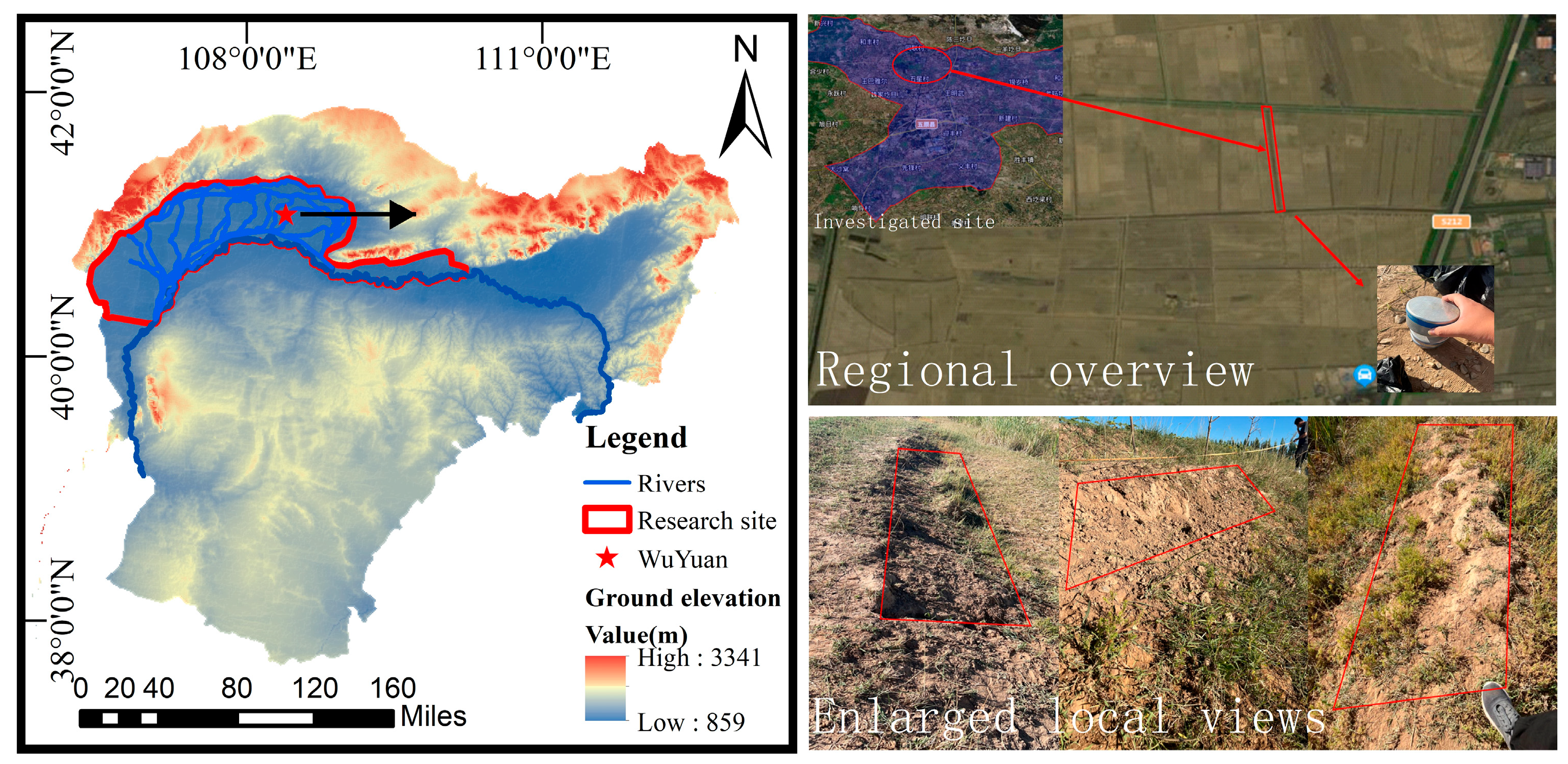

2.1. Site Characterization

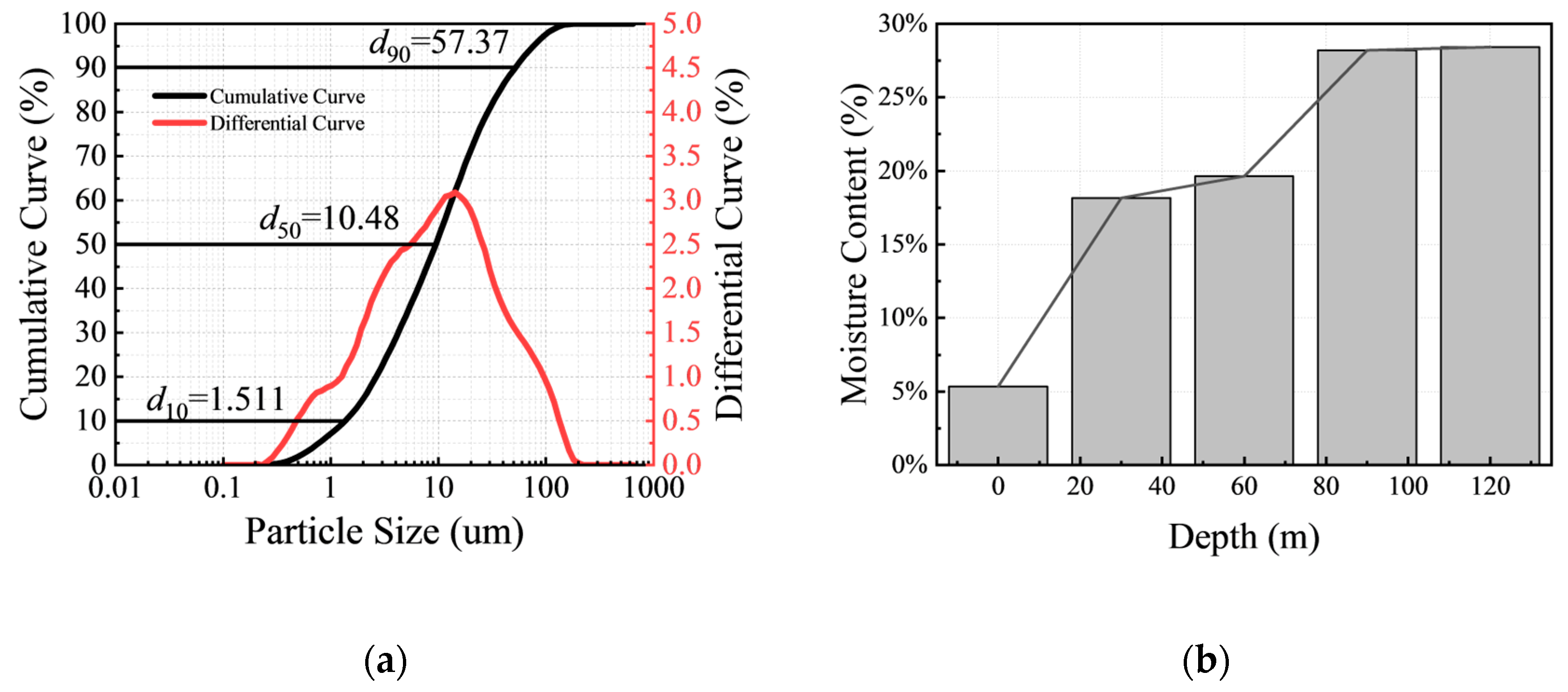

2.2. Soil Properties and Sample Preparation

2.3. Direct Shear Test

2.4. Numerical Modeling Framework

2.4.1. Simulation Methodology and Governing Equations

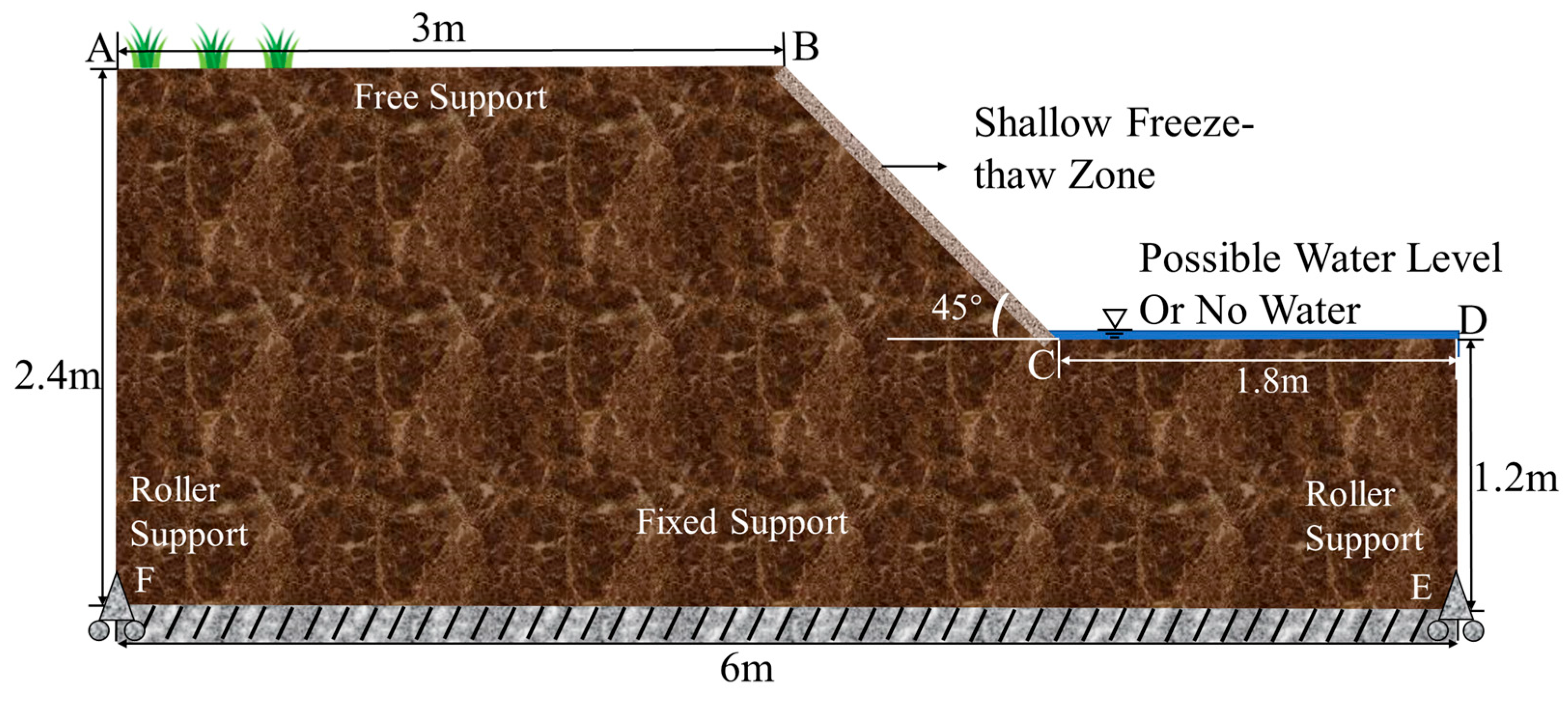

2.4.2. Geometry Modeling, Boundary Conditions, and Parameter Setting

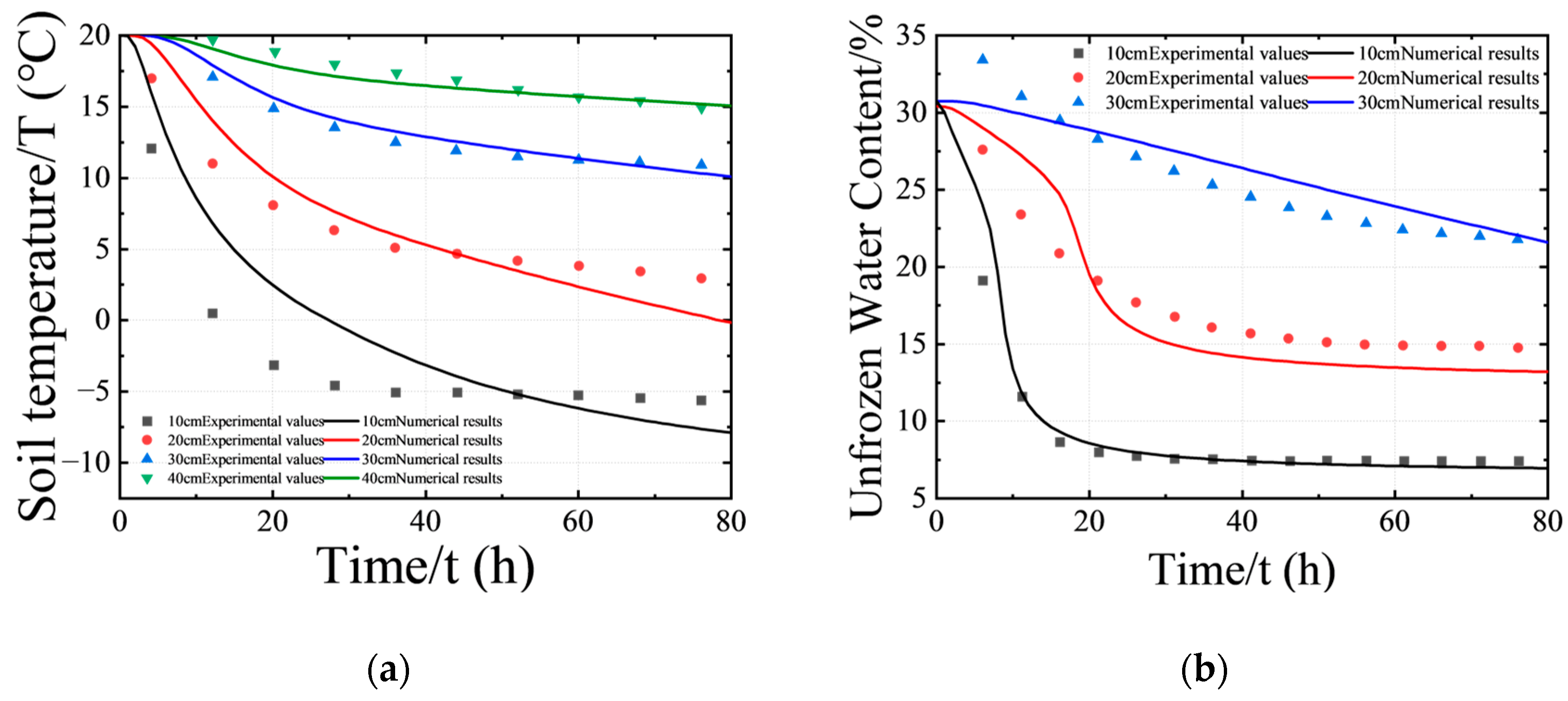

2.4.3. Model Validation

2.4.4. Figure Caption

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Deterioration Effects of Freeze–Thaw Cycles on Soil Mechanical Properties

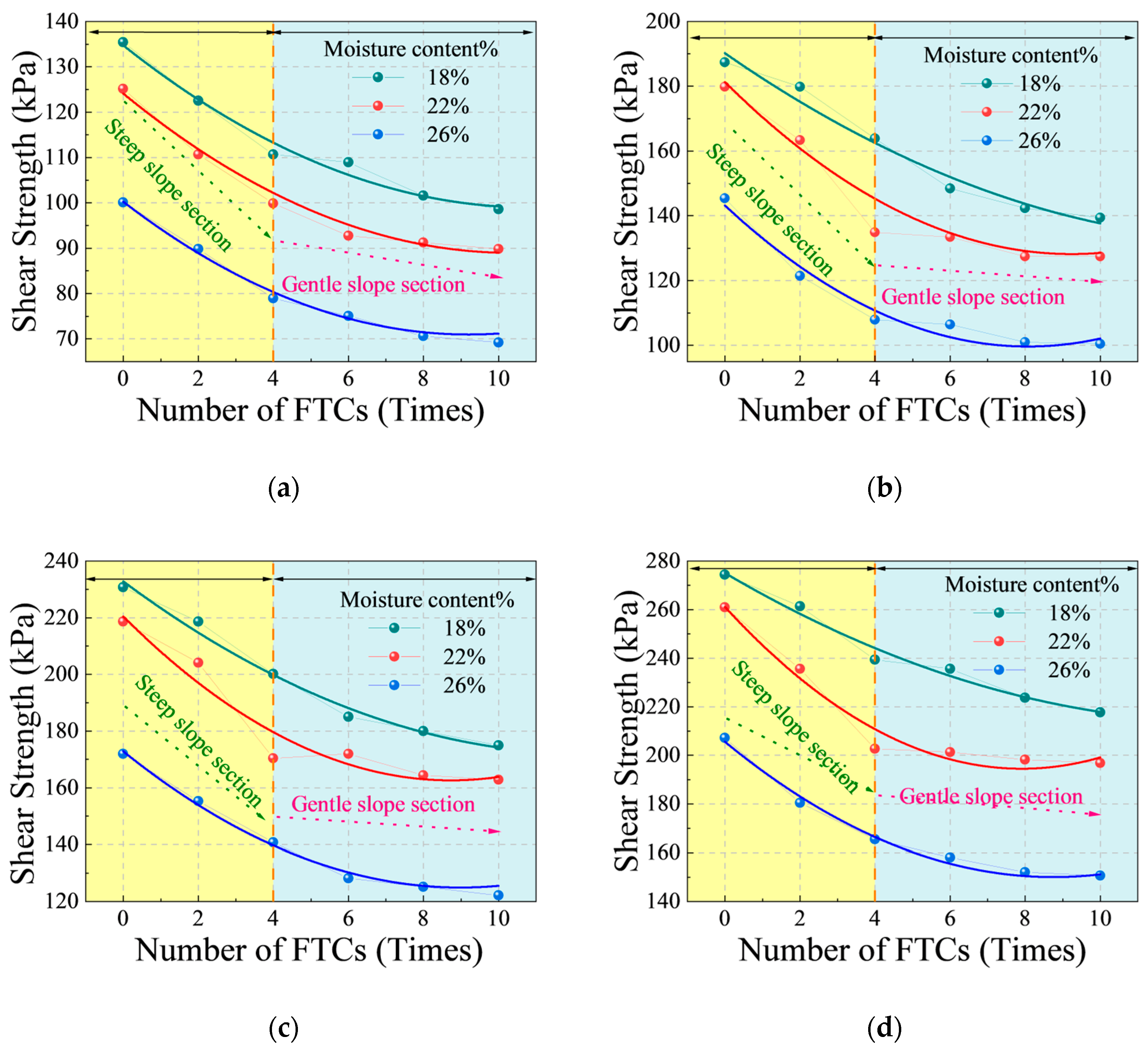

3.1.1. The Attenuation Law of Shear Strength

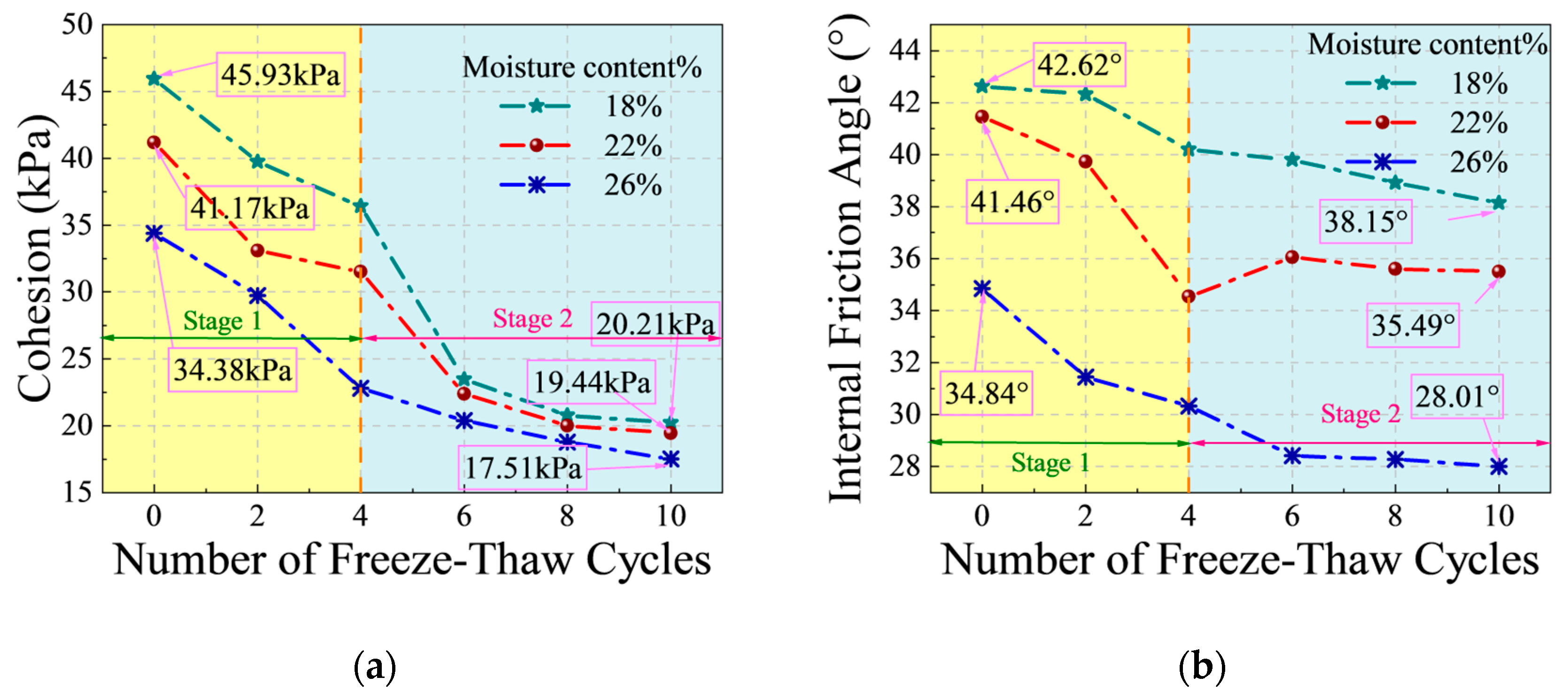

3.1.2. The Evolution Characteristics of Strength Parameters

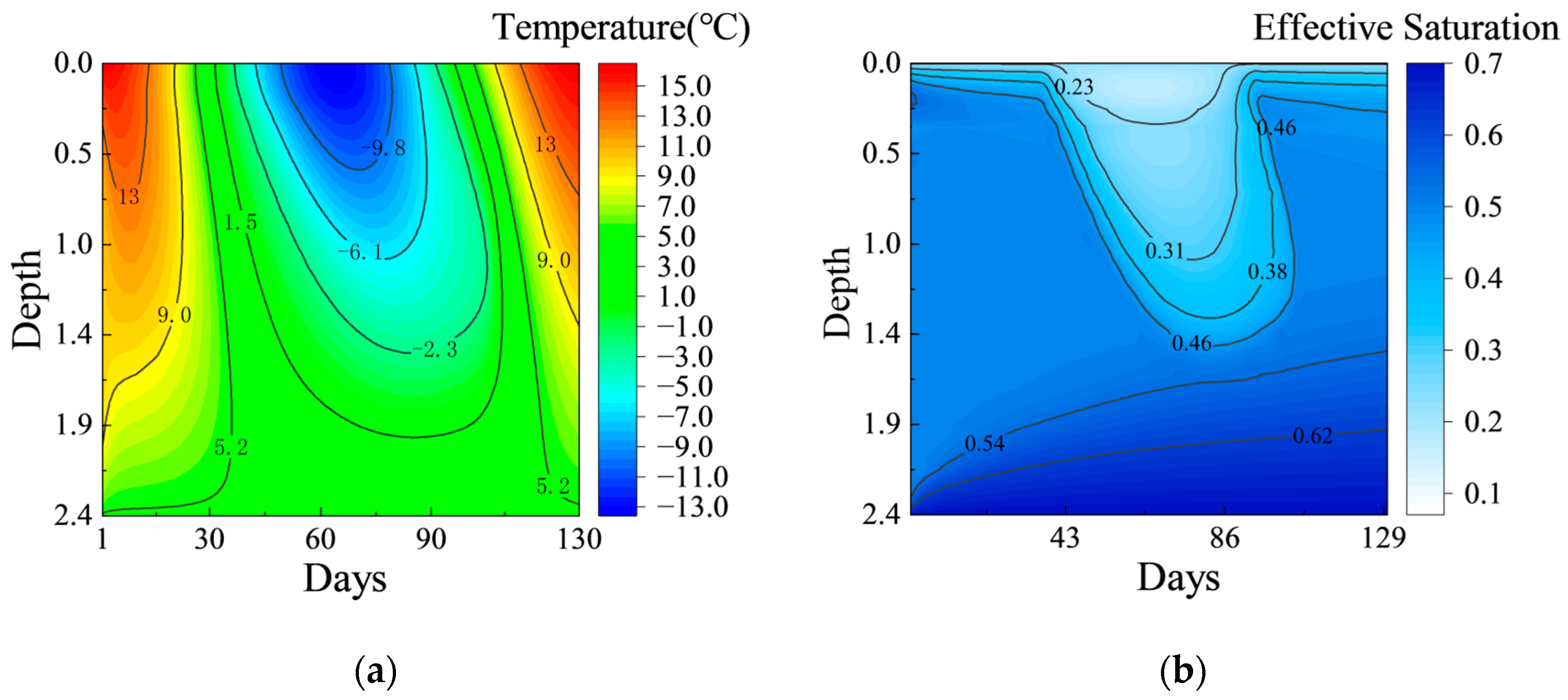

3.2. The Dynamic Hydro-Thermal Evolution Process of Slopes

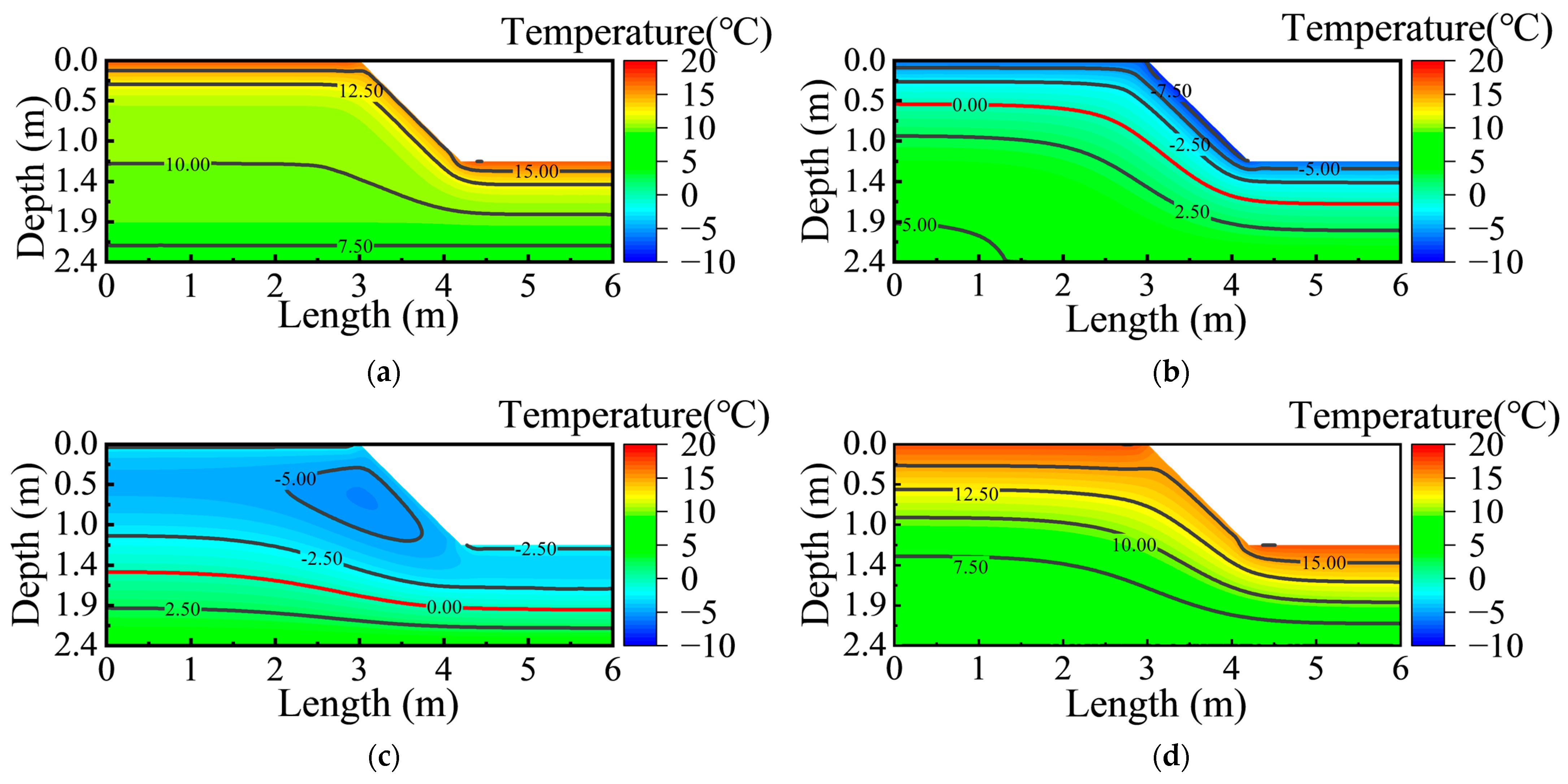

3.2.1. Spatiotemporal Distribution of the Temperature Field

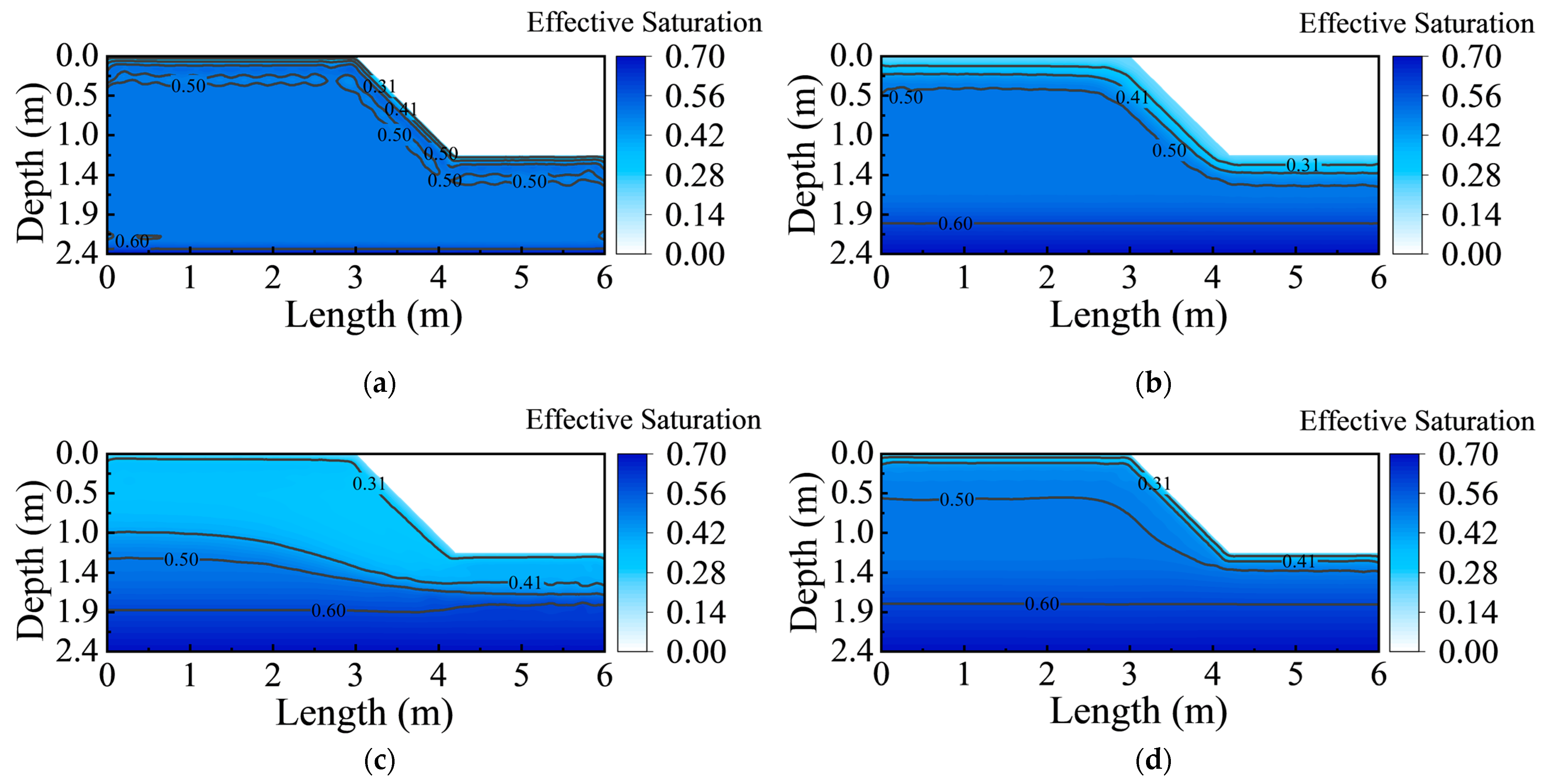

3.2.2. The Migration and Redistribution of the Moisture Field

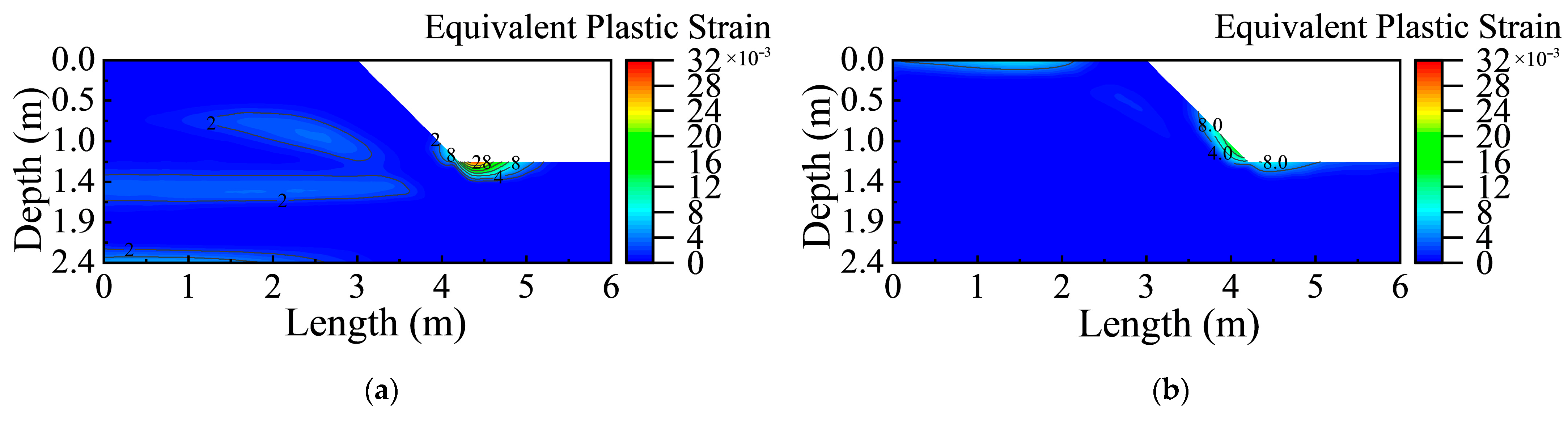

3.3. Stress–Strain Behavior Under Thermo–Hydro Coupling

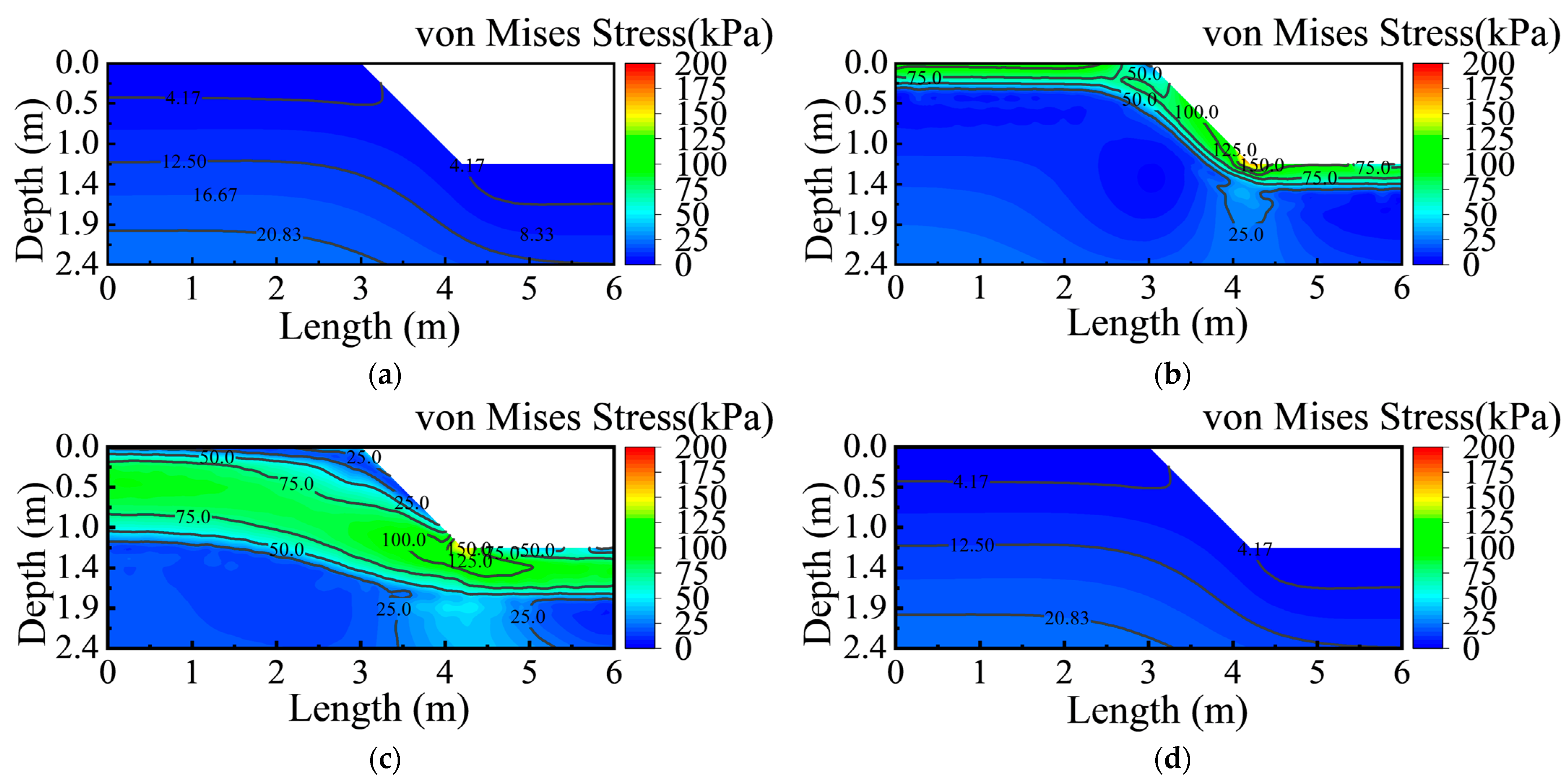

3.3.1. Evolution of Frost Heave Stress

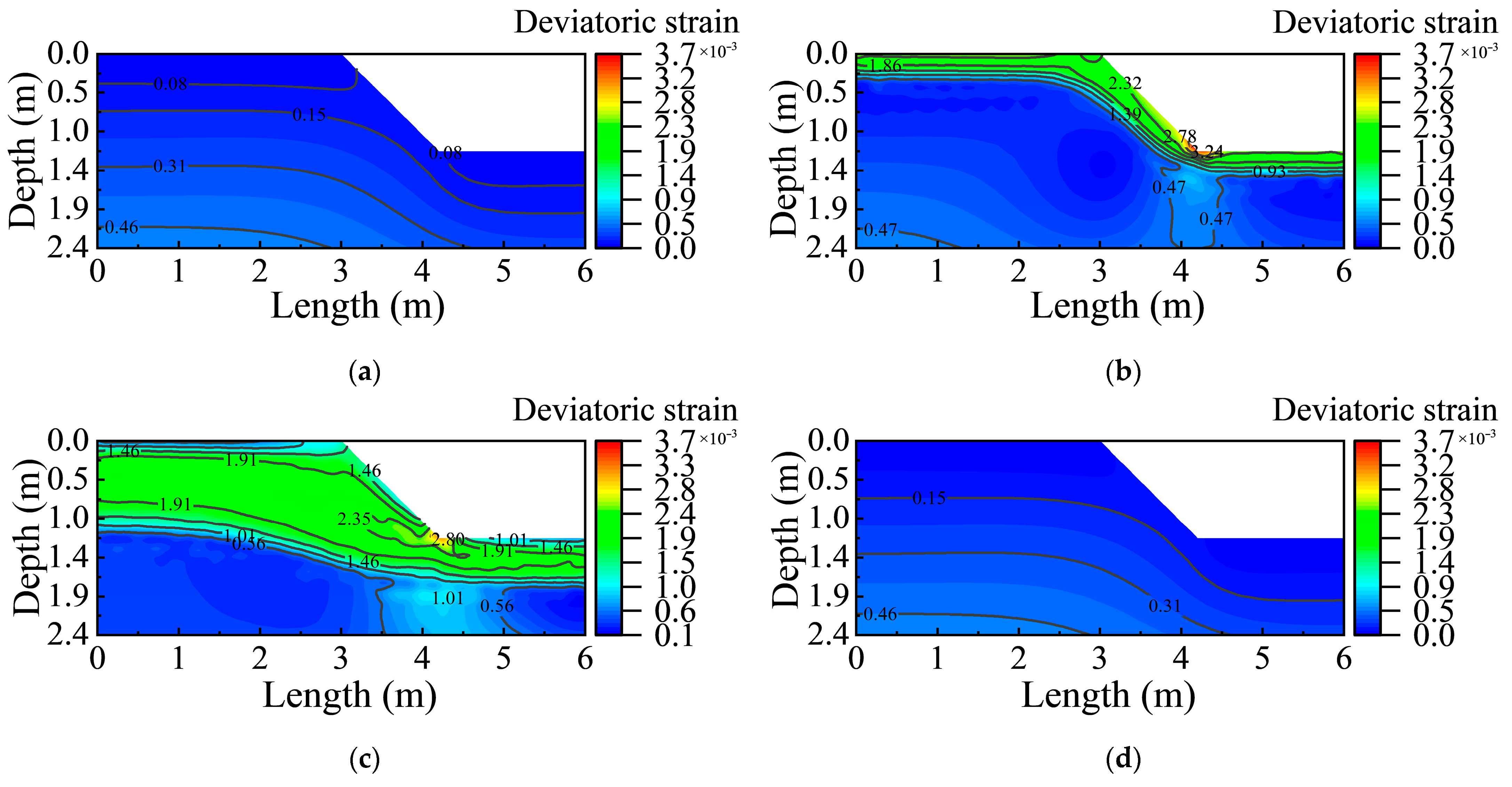

3.3.2. Strain Accumulation and Localization

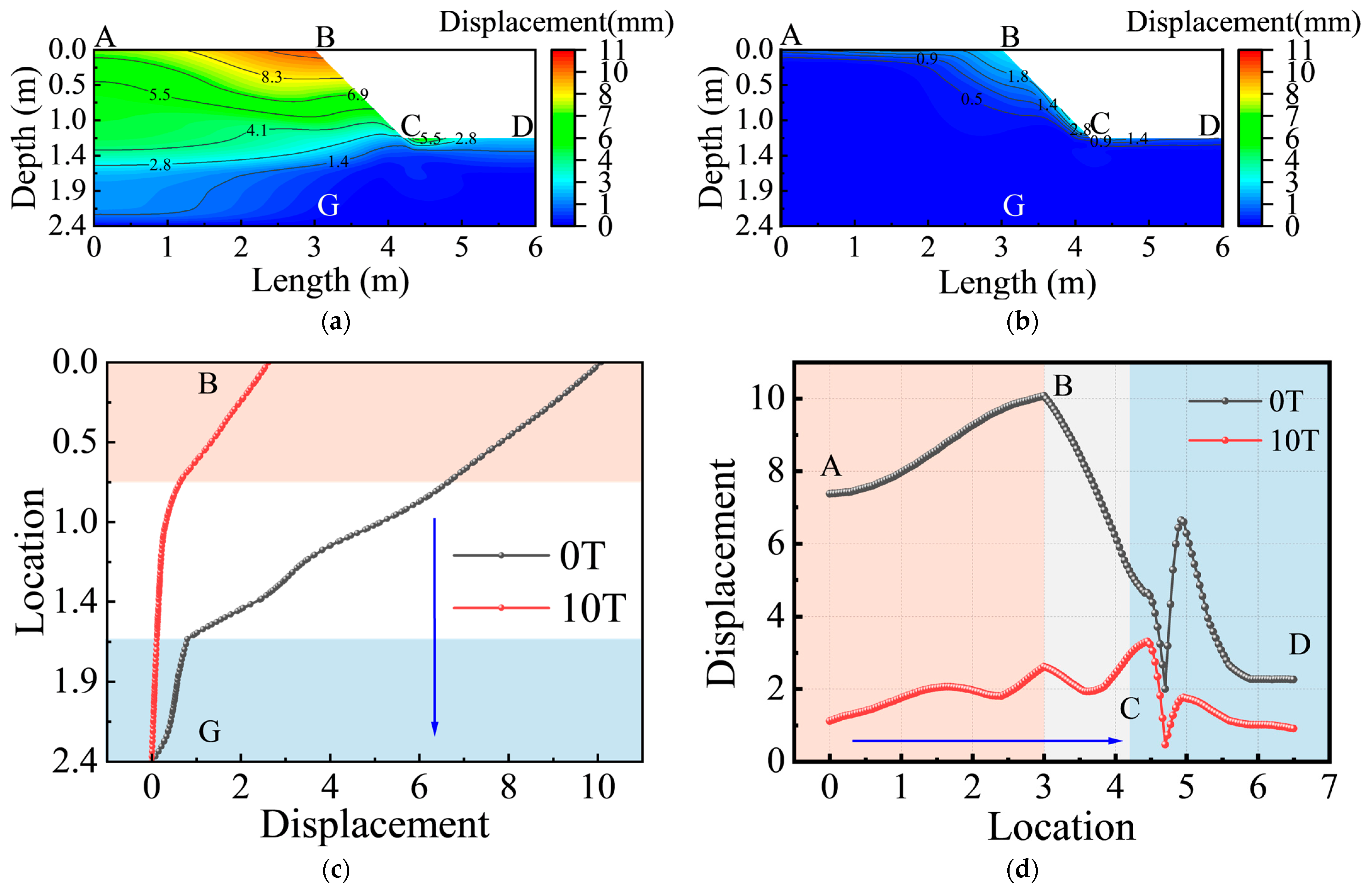

3.4. Slope Stability and Displacement Analysis

3.4.1. Assumptions

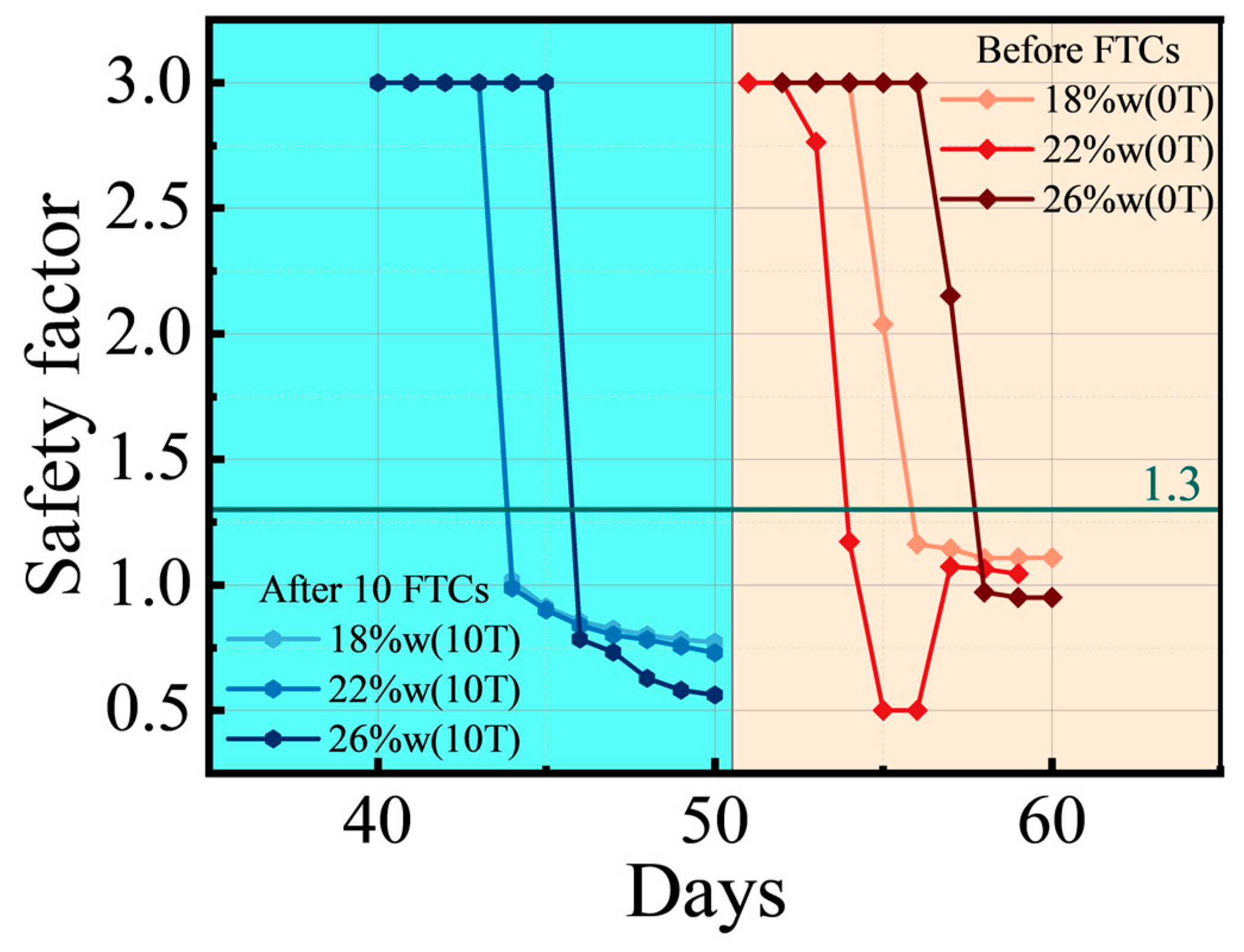

3.4.2. Evolution of the Safety Factor

3.4.3. Evolution and Distribution Characteristics of the Displacement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, R.; Kang, E.; Ji, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y. Cold Regions in China. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2006, 45, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, R. Freezing and thawing characteristics of seasonally frozen ground across China. Geoderma 2024, 448, 116966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Pang, H.; Bell, S.M.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Reinforced soil salinization with distance along the river: A case study of the Yellow River Basin. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 279, 108184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Xu, X.; Hao, Y.; Huang, G. Modeling and assessing field irrigation water use in a canal system of Hetao, upper Yellow River basin: Application to maize, sunflower and watermelon. J. Hydrol. 2016, 532, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Berner, Z.; Tang, X.; Norra, S.; Stüben, D. Hydrogeological and biogeochemical constrains of arsenic mobilization in shallow aquifers from the Hetao basin, Inner Mongolia. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y. Study on Frost Heaving Property of Foundation Soil in Seasonal Frozen Soil Region of Inner Mongolia. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2008, 9, 3840–3841+3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Ye, W.; Wang, D.; Ma, Z.; An, Y. Analysis of Slope Freeze-Thaw Characteristics and Freezing-Induced Water Retention Effects in the Heifangtai Area of Gansu Province. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shi, H.; Fu, X.; Li, Z. Spatiotemporal Variation of Soil Moisture and Salinity During the Freeze-Thaw Period in a Cold and Arid Region. J. Irrig. Drain. 2012, 31, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ma, W.; Zhang, S.; Mu, Y.; Li, G. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles in mechanical behaviors of frozen loess. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 146, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Mou, X.; Ji, H.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, J. Effects of freeze–thaw on bank soil mechanical properties and bank stability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Dong, X.; Lei, H.; Sun, X. Effects of Freeze–Thaw Cycles on the Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of a Dispersed Soil. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ma, W.; Roman, L.; Mel’Nik, A.; Yang, X.; Li, H. Freeze-thaw cycles-physical time analogy theory based method for predicting long-term shear strength of frozen soil. Rock Soil Mech. 2021, 42, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Liu, J. Review of the influence of freeze-thaw cycles on the physical and mechanical properties of soil. Sci. Cold Arid Reg. 2013, 5, 0457–0460. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Vermeer, P.A.; Cheng, G. A review of the influence of freeze-thaw cycles on soil geotechnical properties. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2006, 17, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Shao, S.; Wang, S. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on the strength behaviour of recompacted loess in true triaxial tests. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 181, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Ding, L.; Han, Z.; Wang, X. Effects of freeze-thaw cycles on the moisture sensitivity of a compacted clay. Eng. Geol. 2020, 278, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chang, D.; Yu, Q. Influence of freeze-thaw cycles on mechanical properties of a silty sand. Eng. Geol. 2016, 210, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelidis, L.; Griffiths, D.V. Stability of earth slopes. Part I: Two-dimensional analysis in closed-form. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2013, 37, 1969–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.M. State of the Art: Limit Equilibrium and Finite-Element Analysis of Slopes. J. Geotech. Eng. 1996, 122, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janbu, N. Application of Composite Slip Surfaces for Stability Analysis. Proc. Eur. Conf. Stab. Earth Slopes 1954, 3, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, A. The use of the Slip Circle in the Stability Analysis of Slopes. Geotechnique 1955, 5, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, N.R.U.; Price, V.E. The Analysis of the Stability of General Slip Surfaces. Geotechnique 1965, 15, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.P.; Cheng, H. Stability analysis of three-dimensional seismic landslides using the rigorous limit equilibrium method. Eng. Geol. 2014, 174, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.P.; Cheng, H. The long-term stability analysis of 3D creeping slopes using the displacement-based rigorous limit equilibrium method. Eng. Geol. 2015, 195, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zienkiewicz, O.C.; Humpheson, C.; Lewis, R. Associated and non-associated visco-plasticity and plasticity in soil mechanics. Geotechnique 1975, 27, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhu, T.; Cai, X. Hydro-agro-economic optimization for irrigated farming in an arid region: The Hetao Irrigation District, Inner Mongolia. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 277, 108095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Qu, Z.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Qiao, T.; Zhao, Y. Evaluating annual soil carbon emissions under biochar-added farmland subjecting from freeze-thaw cycle. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50123-2019; Geotechnical Test Method Standard. Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- Yuan, Z. Analysis of the Impact of Extreme Temperature Changes on Agricultural Planting in Wuyuan County over the Past 30 Years. J. Smart Agric. 2022, 7, 44–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Cong, S.; Geng, L.; Ling, X.; Gan, F. The effect of freeze-thaw cycling on the mechanical properties of expansive soils. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 145, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beren, M.; Cobanoglu, I.; Çelik, S.B.; Ündül, Ö.J.S.M.; Engineering, F. Shear rate effect on strength characteristics of sandy soils. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2020, 57, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W. Heat Transfer; Northwestern Polytechnical University Press: Xi’an, China, 2006. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.S.; Luthin, J.N. A model for coupled heat and moisture transfer during soil freezing. Can. Geotech. J. 1978, 15, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Likos, W.J. Unsaturated Soil Mechanics; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 269–287. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Q.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Fang, J. Research on the Coupled Hydrothermal Model of Frozen Soil and Its Numerical Simulation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 37, 131–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Zhao, W.; Li, S.; Dong, M.; Xia, Z.; Shi, Y. Study on Seasonal Permafrost Roadbed Deformation Based on Water–Heat Coupling Characteristics. Buildings 2024, 14, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Li, X.; Yang, W.; Liu, Z.; Chai, H.; Gao, R. Study on thermal-hydro-mechanical coupling and stability evolution of loess slope during freeze—Thaw process. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 2010–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, X.; Hou, Y.; Li, Y. Thermo–Hydromechanical Simulation of Fibre–Coal Gangue Stabilised Expansive Soils Under Freeze–Thaw Cycles Using COMSOL. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2025, 2025, 5908032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Qu, Z.; Yang, X.; Fu, X. Application and Adaptability Assessment of Bayesian Models in Pedotransfer Functions. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2014, 45, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. Experimental and Numerical Simulation Analysis of Hydrothermal Migration in Silty Sand under Freezing Effect in Cold Regions. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Stark, T.; Ruffing, D. Selecting Minimum Factors of Safety for 3D Slope Stability Analyses; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2017; pp. 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Liao, M.; Hu, K. A constitutive model of frozen saline sandy soil based on energy dissipation theory. Int. J. Plast. 2016, 78, 84–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ma, W.; Feng, W.; Xiao, D.; Hou, X. Reconstruction of Soil Particle Composition During Freeze-Thaw Cycling: A Review. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamidov, M.; Ishchanov, J.; Hamidov, A.; Shermatov, E.; Gafurov, Z. Impact of Soil Surface Temperature on Changes in the Groundwater Level. Water 2023, 15, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lai, Y.; Zhang, M.; You, Z.; Li, S.; Bai, R. Study on the coupling mechanism of water-heat-vapor-salt-mechanics in unsaturated freezing sulfate saline soil. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 169, 106232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Natural Water Content | Natural Dry Density (g/cm3) | Optimum Moisture Content | Maximum Dry Density (g/cm3) | Specific Gravity | Liquid Limit | Plastic Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.33–28.43% | 1.35–1.57 | 18% | 1.57 | 2.6 | 31.5 | 21.2 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Density of ice ρi (kg/m3) | 918 |

| Density of water ρw (kg/m3) | 1000 |

| Density of soil ρs (kg/m3) | 1460 |

| Saturated water content θs (%) | 0.42 |

| Residual water content θr (%) | 0.1 |

| Hydraulic conductivity ksat (m/s) | 9.62 × 10−6 |

| Soil freezing temperature Tf (°C) | −2 |

| Specific heat capacity of ice Ci [J/(kg·K)] | 2100 |

| Specific heat capacity of water Cw [J/(kg·K)] | 4200 |

| Specific heat capacity of soil Cs [J/(kg·K)] | 890 |

| Latent heat L (kJ/kg) | 334.56 |

| Thermal conductivity of ice λi [W/(m·K)] | 2.31 |

| Thermal conductivity of water λw [W/(m·K)] | 0.63 |

| Thermal conductivity of soil λs [W/(m·K)] | 1.38 |

| α(m−1) * | 3.2 |

| m * | 0.184 |

| l | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Li, C.; Ding, F.; Shao, Y. Experimental Study and THM Coupling Analysis of Slope Instability in Seasonally Frozen Ground. GeoHazards 2026, 7, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010013

Chen X, Li C, Ding F, Shao Y. Experimental Study and THM Coupling Analysis of Slope Instability in Seasonally Frozen Ground. GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiangshen, Chao Li, Feng Ding, and Yongju Shao. 2026. "Experimental Study and THM Coupling Analysis of Slope Instability in Seasonally Frozen Ground" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010013

APA StyleChen, X., Li, C., Ding, F., & Shao, Y. (2026). Experimental Study and THM Coupling Analysis of Slope Instability in Seasonally Frozen Ground. GeoHazards, 7(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010013