Public Access Dimensions of Landscape Changes in Parks and Reserves: Case Studies of Erosion Impacts and Responses in a Changing Climate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

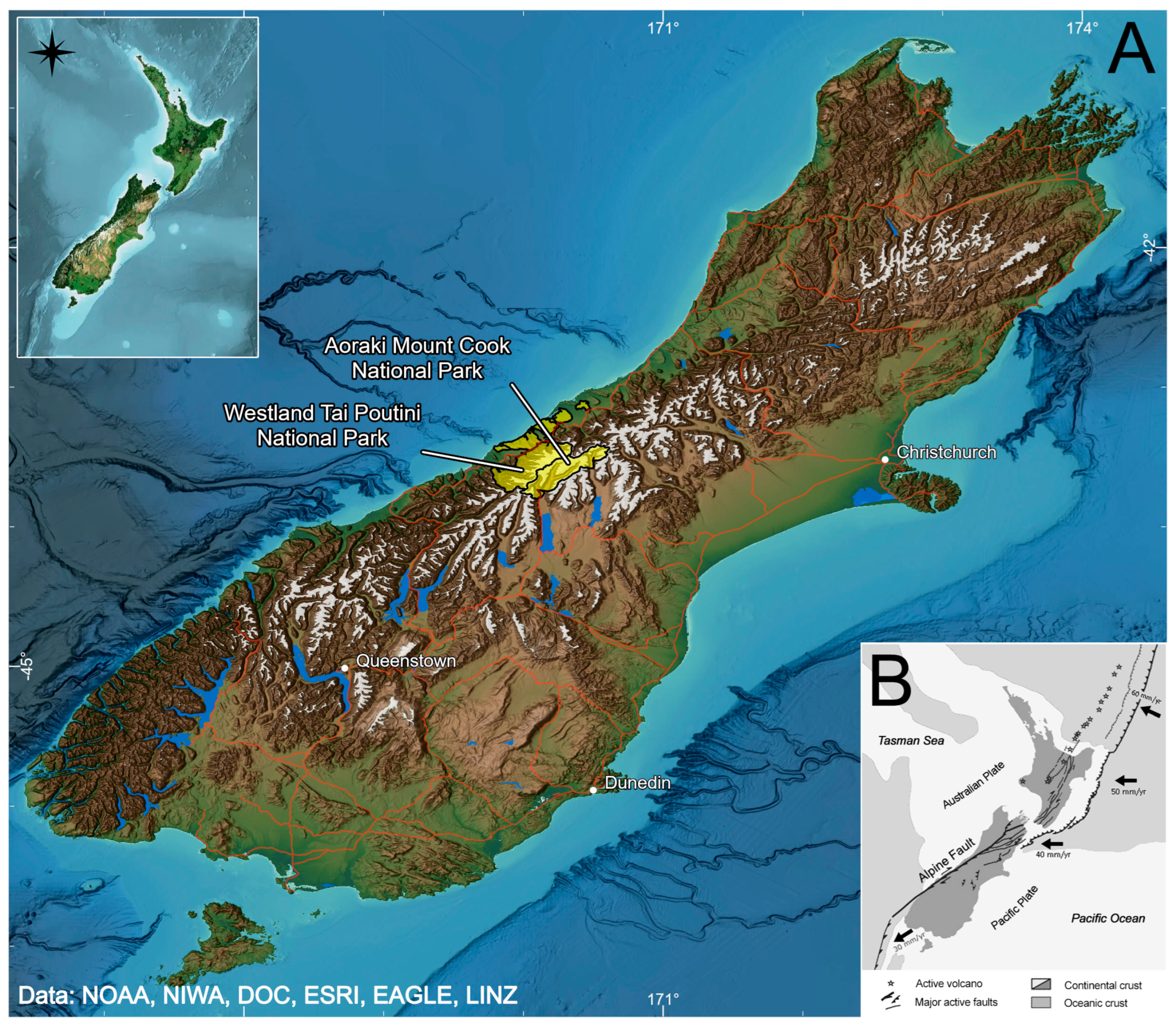

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Approach

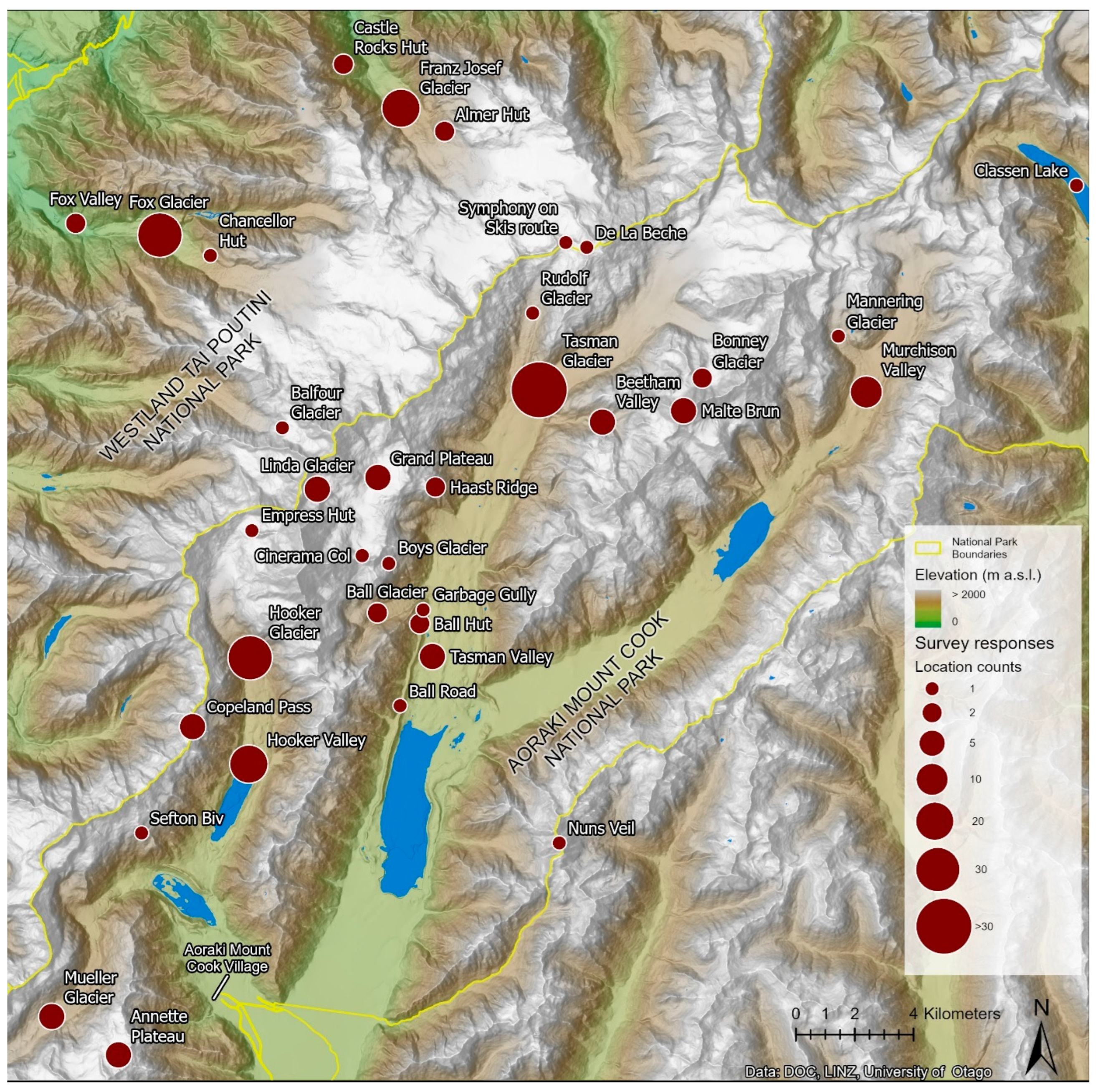

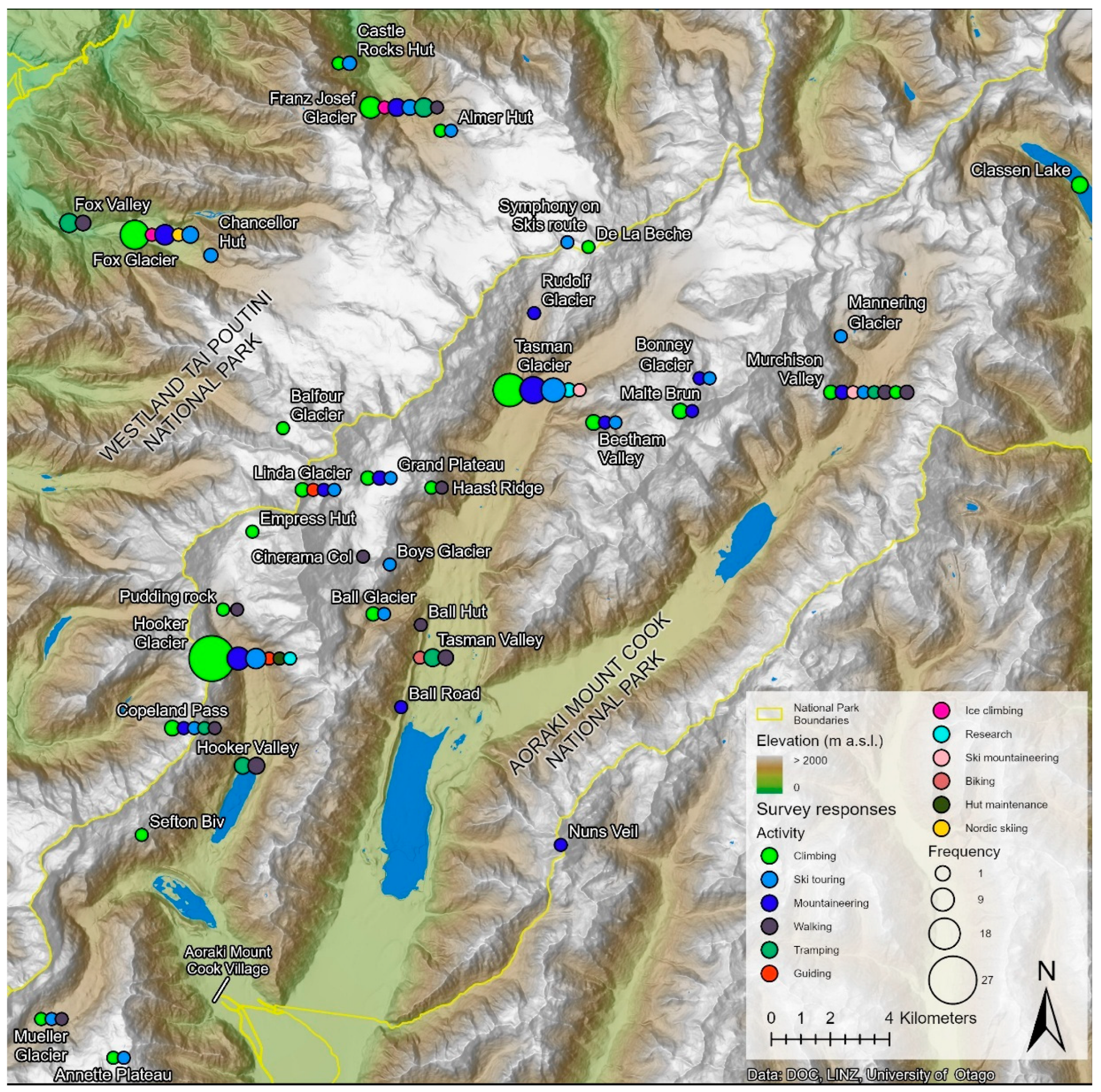

2.3. Park User Survey

2.4. Geospatial Analyses and Case Studies

3. Results

3.1. Hotspots of Landscape Change

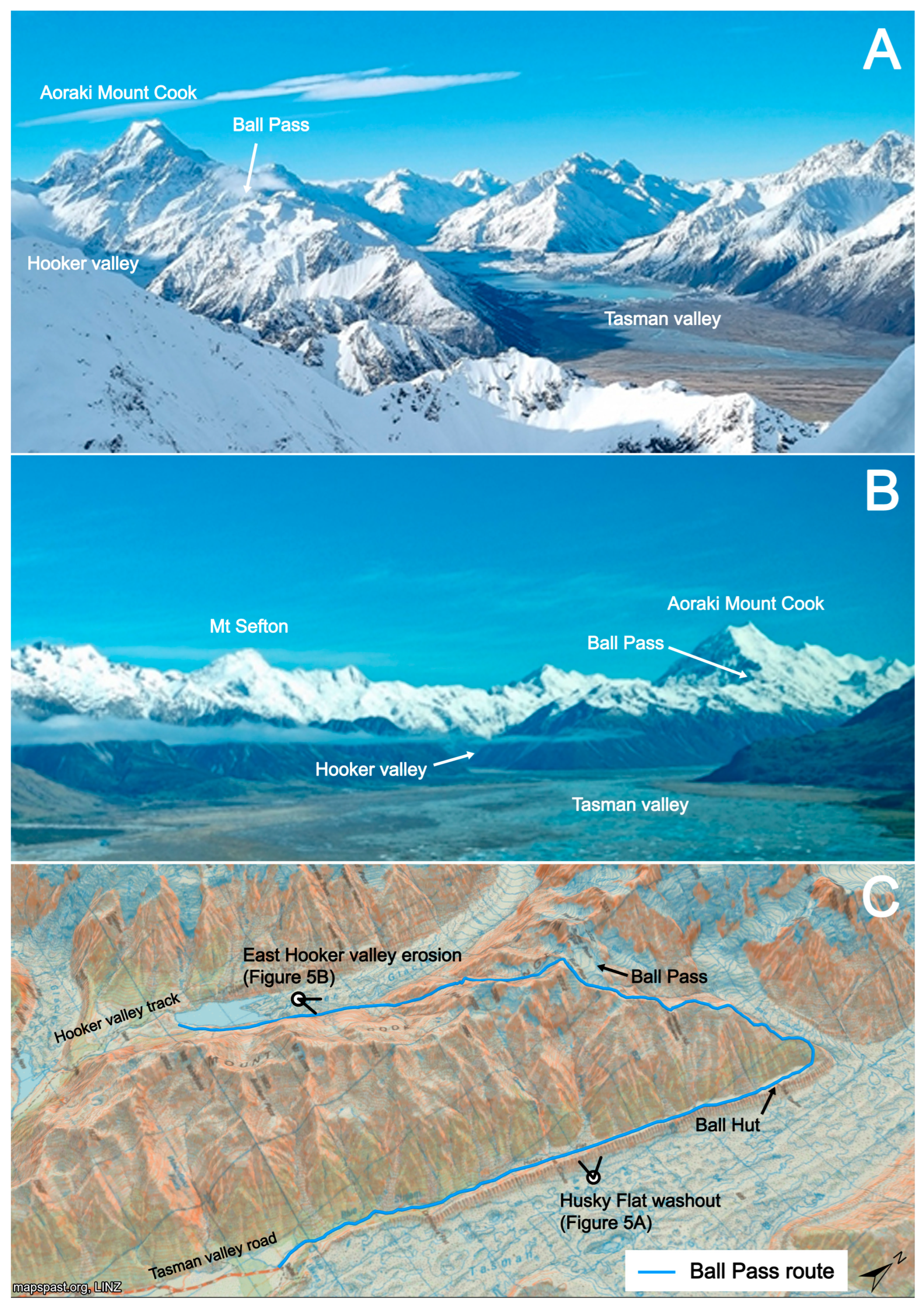

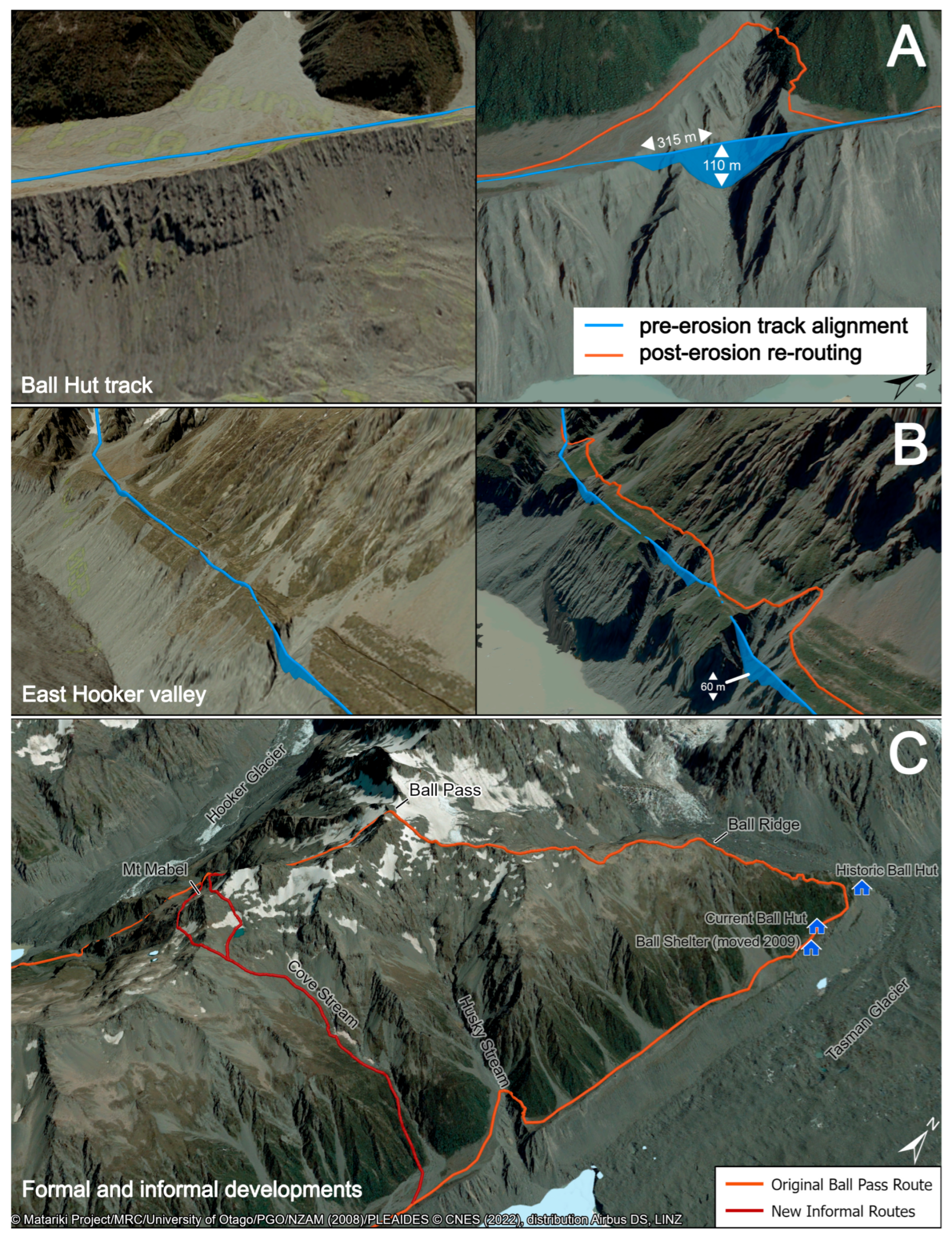

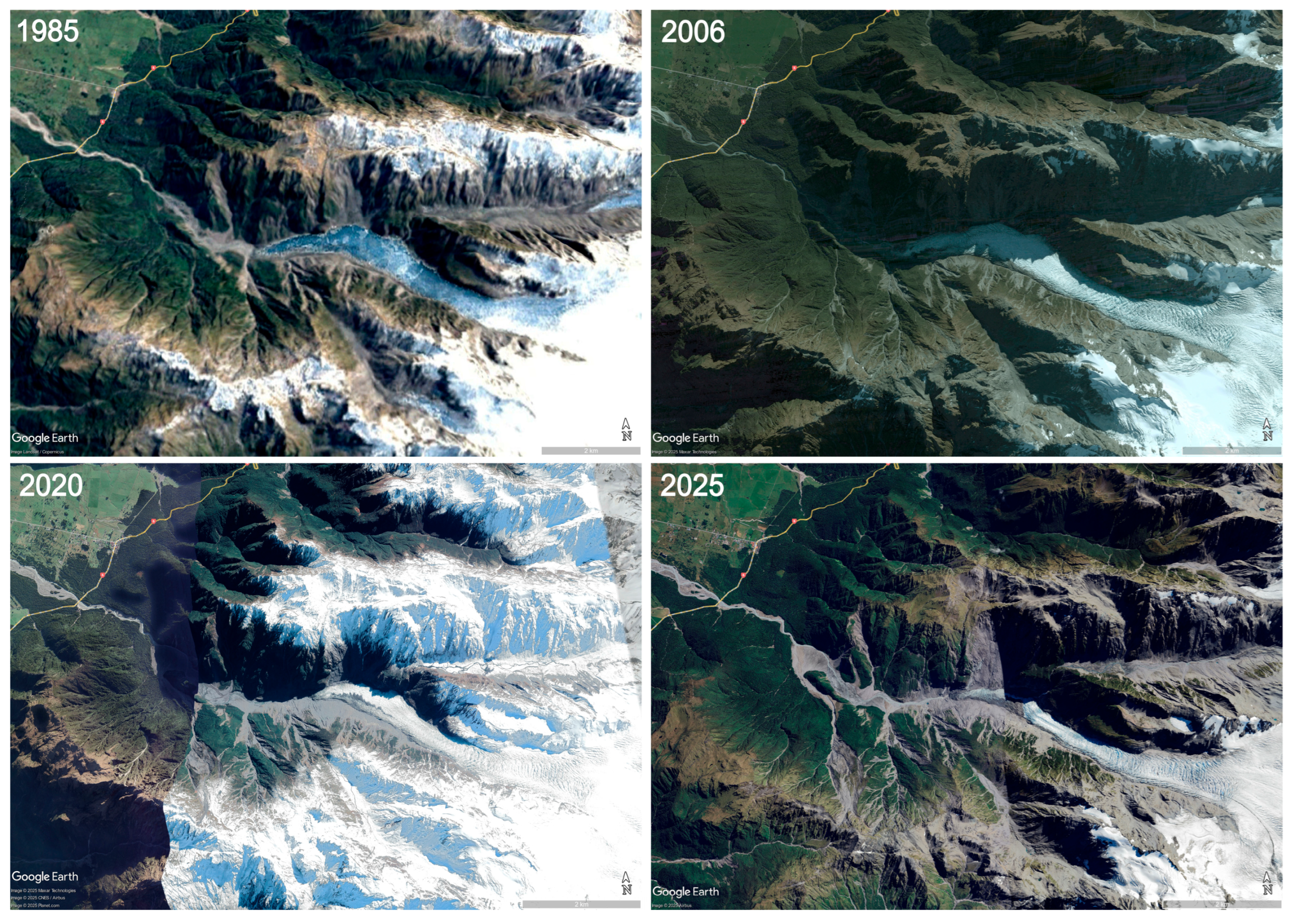

3.2. Ball Pass Route and Glacier Access in Aoraki Mount Cook National Park

3.2.1. Tasman Valley

3.2.2. Hooker Valley

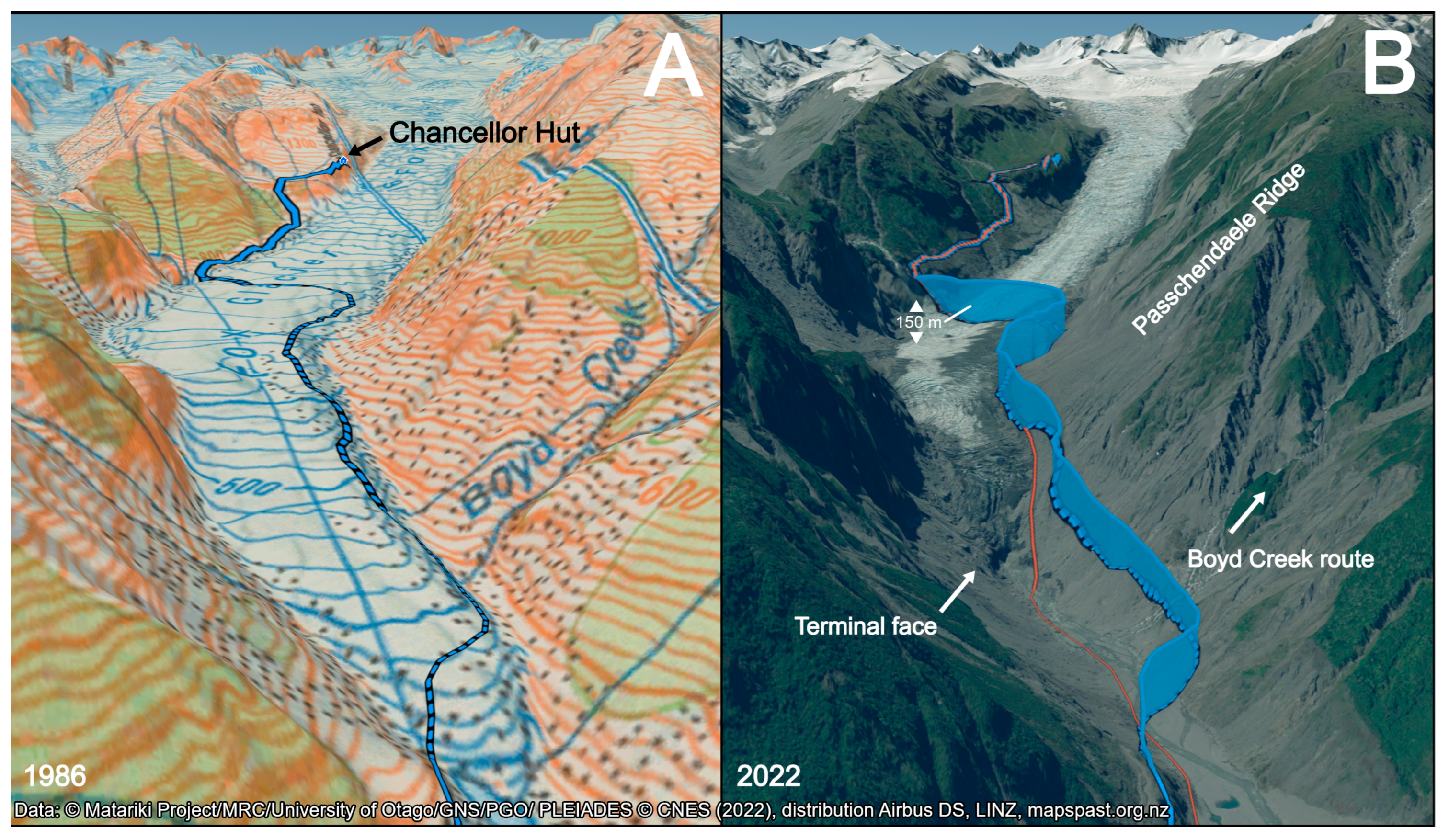

3.3. Fox Glacier/Te Moeka o Tuawe Access in Westland Tai Poutini National Park

4. Discussion

4.1. Public Access as a Focus for Environmental Management

4.2. Human Dimensions

- Providing access that supports the core functions of protected areas;

- Evaluating the impacts of both physical changes and human responses to them;

- Managing tensions between stakeholder preferences.

4.3. Providing Access That Supports the Core Functions of Protected Areas

4.4. Impacts of Both Physical Changes and Human Responses to Them

4.5. Managing Tensions Between Stakeholder Preferences

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brackhane, S.; Schoof, N.; Reif, A.; Schmitt, C.B. A new wilderness for Central Europe?—The potential for large strictly protected forest reserves in Germany. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 237, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, H.; Dearden, P. Rethinking protected area categories and the new paradigm. Environ. Conserv. 2005, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, D.S.; Morelli, G.A.; Demmer, J.; Starkey, M.; Telfer, P.; Steil, M. Parks and people: Assessing the human welfare effects of establishing protected areas for biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and peoples: The social impact of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H.; Busch, M.L. Park-people relationships: An international review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1990, 19, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.C.; Ban, N.C.; Bhattacharyya, J. A review of successes, challenges, and lessons from Indigenous protected and conserved areas. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.E. Indigenous Peoples, National Parks, and Protected Areas: A New Paradigm Linking Conservation, Culture, and Rights; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN-WCPA Task Force on OECMs. Recognising and Reporting Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Olive, R.; Wheaton, B. Understanding blue spaces: Sport, bodies, wellbeing, and the sea. J. Sport Soc. Iss. 2021, 45, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, B.W.; White, M.; Stahl-Timmins, W.; Depledge, M.H. Does living by the coast improve health and wellbeing? Health Place 2012, 18, 1198–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; van den Bosch, M.; Lafortezza, R. The health benefits of nature-based solutions to urbanization challenges for children and the elderly—A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Østby, K. Pocket parks for people—A study of park design and use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.A.; Pidgeon, N.F. Man-Made Disasters, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.; McAlear, Z.; Plovnick, A.; Wilkerson, A. Trails and Resilience: Review of the Role of Trails in Climate Resilience and Emergency Response; U.S. Department of Transportation: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023.

- Jellard, S.; Bell, S.L. A fragmented sense of home: Reconfiguring therapeutic coastal encounters in COVID-19 times. Emot. Space Soc. 2021, 40, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, S.; Reiblich, J.; dos Santos, M.D. Public coastal access: Emerging issues and potential solutions. Mar. Policy 2025, 179, 106759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, B. Future challenges in beach management as contested spaces. In Sandy Beach Morphodynamics; Jackson, D.W.T., Short, A.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 711–731. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, E.J.; Wilson, J.; Espiner, S.; Purdie, H.; Lemieux, C.; Dawson, J. Implications of climate change for glacier tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdie, H. Glacier retreat and tourism: Insights from New Zealand. Mt. Res. Dev. 2013, 33, 463–472, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. Aoraki Tai Poutini. A Guide for Mountaineers; New Zealand Alpine Club: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Orchard, S. Backcountry Ski-Touring in New Zealand: A Guide to New Zealand’s Best Backcountry Terrain; New Zealand Alpine Club: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Conservation. Westland Tai Poutini National Park Management Plan—Amended 4 April 2014; Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2014.

- Department of Conservation. Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park Management Plan; Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2004.

- Purdie, H.; Hutton, J.H.; Stewart, E.; Espiner, S. Implications of a changing alpine environment for geotourism: A case study from Aoraki/Mount Cook, New Zealand. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 29, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.; Purdie, H.; Stewart, E.; Espiner, S. Environmental Change and Tourism at Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park; Leap Report No. 41; Lincoln University: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Conservation. Draft Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park Management Plan; Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018.

- Sommer, C.; Malz, P.; Seehaus, T.C.; Lippl, S.; Zemp, M.; Braun, M.H. Rapid glacier retreat and downwasting throughout the European Alps in the early 21st century. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugonnet, R.; McNabb, R.; Berthier, E.; Menounos, B.; Nuth, C.; Girod, L.; Farinotti, D.; Huss, M.; Dussaillant, I.; Brun, F.; et al. Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature 2021, 592, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, M.; Bookhagen, B.; Huggel, C.; Jacobsen, D.; Bradley, R.S.; Clague, J.J.; Vuille, M.; Buytaert, W.; Cayan, D.R.; Greenwood, G.; et al. Toward mountains without permanent snow and ice. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Summary for Policymakers; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaymaker, O. Proglacial, periglacial or paraglacial? Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2009, 320, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. World Heritage Area Nomination—IUCN Summary. South West New Zealand World Heritage Area (Te Wahipounamu); IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Te Whaiti, K. Understanding Aoraki. Te Karaka 2012, 54, 13. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Government. Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998; Reprint as at 1 August 2020; New Zealand Government: Wellington, New Zealand, 1998.

- Williams, P.W. Tectonic geomorphology, uplift rates and geomorphic response in New Zealand. Catena 1991, 18, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Government. National Parks Act 1980; Version as at 5 April 2025; New Zealand Government: Wellington, New Zealand, 2025.

- New Zealand Government. Responding to the Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki Supreme Court Decision and Giving Effect to Treaty Principles in Conservation; New Zealand Government: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018.

- Supreme Court of New Zealand. Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki Tribal Trust v Minister of Conservation; Supreme Court of New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018.

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Conservation. Draft Westland Tai Poutinit National Park Management Plan; Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018.

- Orchard, S.; Cocks, J.; Tanner, C.; Finlayson, J.; Nepia, E.; Dave Vass, D.; Mackenzie, E.; Miller, A. Recreational Access in Aoraki Mount Cook and Westland National Parks. A Survey of Stakeholder Perspectives; New Zealand Alpine Club: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Free Prior and Informed Consent. An Indigenous Peoples’ Right and a Good Practice for Local Communities; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, R.; Tate, N.J. Conducting Research in Human Geography: Theory, Methodology and Practice; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA; Harlow, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Columbus, J.; Sirguey, P.; Tenzer, R. A free, fully assessed 15-m DEM for New Zealand. Surv. Q. 2011, 66, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sirguey, P.; Cullen, N.J.; Hager, T.; Vivero, S. The contribution of photogrammetry, GIS, and geovisualisation to the determination of the height of Aoraki/Mt Cook. In Proceedings of the GeoCart’2014 and ICA Symposium on Cartography, Auckland, New Zealand, 3–5 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.D.; Redpath, T.A.N.; Sirguey, P.; Cox, S.C.; Bartelt, P.; Bogie, D.; Conway, J.P.; Cullen, N.J.; Bühler, Y. Unprecedented winter rainfall initiates large snow avalanche and mass movement cycle in New Zealand’s Southern Alps/Kā Tiritiri o te Moana. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2022GL102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthier, E.; Lebreton, J.; Fontannaz, D.; Hosford, S.; Belart, J.M.C.; Brun, F.; Andreassen, L.M.; Menounos, B.; Blondel, C. The Pléiades Glacier Observatory: High-resolution digital elevation models and ortho-imagery to monitor glacier change. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 5551–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, L.A.; Sirguey, P.; Miller, A.; Marty, M.; Schindler, K.; Stoffel, A.; Bühler, Y. Intercomparison of photogrammetric platforms for spatially continuous snow depth mapping. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareei, S.; Kelbe, D.; Sirguey, P.; Mills, S.; Eyers, D.M. Virtual ground control for survey-grade terrain modelling from satellite imagery. Paper presented at the 36th International Conference on Image and Vision. Computing New Zealand (IVCNZ), Tauranga, New Zealand, 9–10 December 2021; Volume 2021, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, G. A History of Mountain Climbing in New Zealand to 1953. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Purdie, H.; Gomez, C.; Espiner, S. Glacier recession and the changing rockfall hazard: Implications for glacier tourism. N. Z. Geogr. 2015, 71, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Conservation. Fox Glacier/Te Moeka o Tuawe Road Access; Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019.

- Massey, C.I.; De Vilder, S.; Taig, T.; Lukovic, B.; Archibald, G.C.; Morgenstern, R. Landslide Hazard and Risk Assessment for the Fox and Franz Josef Glacier Valleys; GNS Science Report 2022/29; Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2022; 79p. [Google Scholar]

- Hockings, M. Systems for assessing the effectiveness of management in protected areas. Bioscience 2003, 53, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.M.; Hutton, J. People, parks and poverty: Political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C.W.; Carr, A.; Vandermale, E.; Snow, B.; Philipp, L. Rethinking the role of Indigenous knowledge in sustainable mountain development and Protected Area management in Canada and Aotearoa/New Zealand. Mt. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, A1–A9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolton, S.; Shadie, P.; Dudley, N. IUCN WCPA Best Practice Guidance on Recognising Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Types; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coad, L.; Leverington, F.; Knights, K.; Geldmann, J.; Eassom, A.; Kapos, V.; Kingston, N.; de Lima, M.; Zamora, C.; Cuardros, I.; et al. Measuring impact of protected area management interventions: Current and future use of the Global Database of Protected Area Management Effectiveness. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverington, F.; Costa, K.L.; Pavese, H.; Lisle, A.; Hockings, M. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuerthner, G.; Crist, E.; Butler, T. Protecting the Wild: Parks and Wilderness, the Foundation for Conservation; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.A.; Matthews, C. Building a culture of conservation: Research findings and research priorities on connecting people to nature in parks. Parks 2015, 12, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, L.; Cannizzo, Z.; Stephenson, F.; Orchard, S.; Clarkson, S.; Weather, E.; Howe, S.; Kirkland, A.; Becker, D. Establishing Marine Protected Areas in a Changing Climate; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Magness, D.R.; Wagener, E.; Yurcich, E.; Mollnow, R.; Granfors, D.; Wilkening, J.L. A multi-scale blueprint for building the decision context to implement climate change adaptation on National Wildlife Refuges in the United States. Earth 2022, 3, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, C.R.; Berio Fortini, L.; Sprague, J.; Sprague, R.S.; Hess, S.C. Using systematic conservation planning to identify climate resilient habitat for endangered species recovery while retaining areas of cultural importance. Conservation 2024, 4, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Irl, S.D.H.; Beierkuhnlein, C. Predicted climate shifts within terrestrial protected areas worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawler, J.J.; Rinnan, D.S.; Michalak, J.L.; Withey, J.C.; Randels, C.R.; Possingham, H.P. Planning for climate change through additions to a national protected area network: Implications for cost and configuration. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.M.; O’Leary, B.C.; Hawkins, J.P. Climate change mitigation and nature conservation both require higher protected area targets. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, J.S.; Gunderson, L.; Allen, C.D.; Fleishman, E.; McKenzie, D.; Meyerson, L.A.; Oropeza, J.; Stephenson, N. Options for national parks and reserves for adapting to climate change. Environ. Manag. 2009, 44, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, G.E.; Braun, J. The tectonic evolution of the Southern Alps, New Zealand: Insights from fully thermally coupled dynamical modelling. Geophys. J. Int. 1999, 136, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.K.; Cox, S.C.; Owens, I.F. Rock avalanches and other landslides in the central Southern Alps of New Zealand: A regional study considering possible climate change impacts. Landslides 2011, 8, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirguey, P.; Cox, S. Hazard at Murchison Hut, Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park; GNS Sciences: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.K.; Schneider, D.; Owens, I.F. First approaches towards modelling glacial hazards in the Mount Cook region of New Zealand’s Southern Alps. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009, 9, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, E.; Draebing, D.; McColl, S.; Cook, S.; Brideau, M.-A. Geomorphology and geological controls of an active paraglacial rockslide in the New Zealand Southern Alps. Landslides 2020, 17, 755–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, I.; Pardo, M. Tourism versus nature conservation: Reconciliation of common interests and objectives—An analysis through Picos de Europa National Park. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 2505–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton-Treves, L.; Holland, M.B.; Brandon, K. The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papworth, S.K.; Rist, J.; Coad, L.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Evidence for shifting baseline syndrome in conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2009, 2, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, S.; Fischman, H.S.; Schiel, D.R. Managing beach access and vehicle impacts following reconfiguration of the landscape by a natural hazard event. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 220, 106101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiner, S.; Becken, S. Tourist towns on the edge: Conceptualising vulnerability and resilience in a protected area tourism system. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 646–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, E.; Ravanel, L.; Bourdeau, P.; Deline, P. Glacier tourism and climate change: Effects, adaptations, and perspectives in the Alps. Reg. Environ. Change 2021, 21, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankey, G.H.; McCool, S.F. Carrying capacity in recreational settings: Evolution, appraisal, and application. Leis. Sci. 1984, 6, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellon, V.; Bramwell, B. Protected area policies and sustainable tourism: Influences, relationships and co-evolution. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1369–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budowski, G. Tourism and environmental conservation: Conflict, coexistence, or symbiosis? Environ. Conserv. 1976, 3, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, S.; Comber, A.; McMorran, R.; Nutter, S. A GIS model for mapping spatial patterns and distribution of wild land in Scotland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 104, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.; Dixon, G. A remoteness-oriented approach to defining, protecting and restoring wilderness. Parks 2020, 26, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.R.; Venter, O.; Watson, J.E.M. Temporally inter-comparable maps of terrestrial wilderness and the Last of the Wild. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belote, R.T.; Dietz, M.S.; Jenkins, C.N.; McKinley, P.S.; Irwin, G.H.; Fullman, T.J.; Leppi, J.C.; Aplet, G.H. Wild, connected, and diverse: Building a more resilient system of protected areas. Ecol. Appl. 2017, 27, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Shanahan, D.F.; Di Marco, M.; Allan, J.D.; Laurance, W.F.; Sanderson, E.W.; Mackey, B.; Venter, O. Catastrophic declines in wilderness areas undermine global environment targets. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 2929–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N.; Yung, L. Beyond Naturalness: Rethinking Park and Wilderness Stewardship in an Era of Rapid Change; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aycrigg, J.L.; McCarley, T.R.; Belote, R.T.; Martinuzzi, S. Wilderness areas in a changing landscape: Changes in land use, land cover, and climate. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 32, e02471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Negative Effects | Positive Effects |

|---|---|

Landscape changes | |

| Loss of snow and ice feature features | New terrain and surface water features |

Access and hazards | |

| Increased difficulty of historical routes | Longer approaches increasing the challenge of some routes |

| Longer travel times | More difficult access may reduce numbers on popular routes |

| Increased rockfall and moraine hazard | Rock routes may become safer over time |

| Access more difficult on and off lower glaciers | Reduced icefalls could reduce danger on some routes |

Recreational opportunities and hazardscape | |

| Increased rockfall and landslide hazard | New rock climbing features exposed |

| Greater flood risk hazard | New water activities and access modes, e.g., on newly formed lakes |

| Risks to existing infrastructure | More rock is exposed for potential hut sites |

| Greater impacts from aircraft access | Aircraft access to new sites |

| Less snow and ice | Winters less severe |

Social effects | |

| Loss of historical landmarks | Greater awareness of natural processes |

| Reduced interaction to glaciers | Greater awareness of climate change |

| Greater infrastructure investments required | Development of thinking for coping with change |

| Water security for downstream uses | Improved attention to sustainability |

| Reduce aesthetics from glacier changes (e.g., dirty ice) | Lakes could add scenic value |

| Tourism challenges from hazards and change | Tourism benefits of water activities, e.g., on paraglacial lakes |

| Route information goes out of date | Research opportunities associated with change |

| Loss of historical huts and routes | Could catalyse alternative access ideas |

| Route | Data Source | Total Distance (km) | Total Height Gain (m) | Slope Angle Mean (°) | Slope Angle 95th Percentile (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historic route | LINZ: NZMS260 (1999); DEM from 20 m contours (1986) [46]. | 20.6 | 2235 | 8.8 | 55.0 |

| Modern variant | LINZ: NZTopo50 (2023), Matariki Project/MRC/University of Otago/ GNS/PGO/Pleaides © NZAM (2008), © CNES (2022): Orthoimage, DEM. | 21.6 | 2330 | 11.9 | 35.0 |

| Route | Data Source | Total Distance (km) | Total Height Gain (m) | Slope Angle Mean (°) | Slope Angle 95th Percentile (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historic route | LINZ: NZMS260 (1999); DEM from 20 m contours (1986), [46]. | 6.2 | 1281 | 9.5 | 57.0 |

| Modern variant | LINZ: NZTopo50 (2023), Matariki Project/MRC/University of Otago/ GNS/PGO/Pleaides © CNES (2022): Orthoimage, DEM. | 6.0 | 1310 | 13.4 | 41.4 |

| Formal | Informal |

|---|---|

| Closure of tracks and/or removal of key infrastructure (e.g., damaged foot bridges) | Establishment of bypass tracks, sometimes associated with basic infrastructure (e.g., fixed ropes, cables or ladders) |

| Establishment of new roads, tracks and other infrastructure | Adoption of other modes of transport to reach desired destinations (e.g., increased use of aircraft, uptake of new access modes such as packrafts). |

| Relocation of supporting infrastructure such as huts and shelters | Abandonment of routes/destinations in favour of other locations |

| Re-development of road-head facilities | Communications of changes within user groups (e.g., guidebook updates, conditions and trip reports, social media) |

| Permits or spatial planning (i.e., zoning) for new types of access infrastructure or equipment | |

| Communications and educational materials to inform public of changing hazards and new facilities or arrangements (e.g., website content, on-site barriers, signage) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Orchard, S.; Miller, A.; Sirguey, P. Public Access Dimensions of Landscape Changes in Parks and Reserves: Case Studies of Erosion Impacts and Responses in a Changing Climate. GeoHazards 2026, 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010012

Orchard S, Miller A, Sirguey P. Public Access Dimensions of Landscape Changes in Parks and Reserves: Case Studies of Erosion Impacts and Responses in a Changing Climate. GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrchard, Shane, Aubrey Miller, and Pascal Sirguey. 2026. "Public Access Dimensions of Landscape Changes in Parks and Reserves: Case Studies of Erosion Impacts and Responses in a Changing Climate" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010012

APA StyleOrchard, S., Miller, A., & Sirguey, P. (2026). Public Access Dimensions of Landscape Changes in Parks and Reserves: Case Studies of Erosion Impacts and Responses in a Changing Climate. GeoHazards, 7(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010012