Vineyard Groundcover Biodiversity: Using Deep Learning to Differentiate Cover Crop Communities from Aerial RGB Imagery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

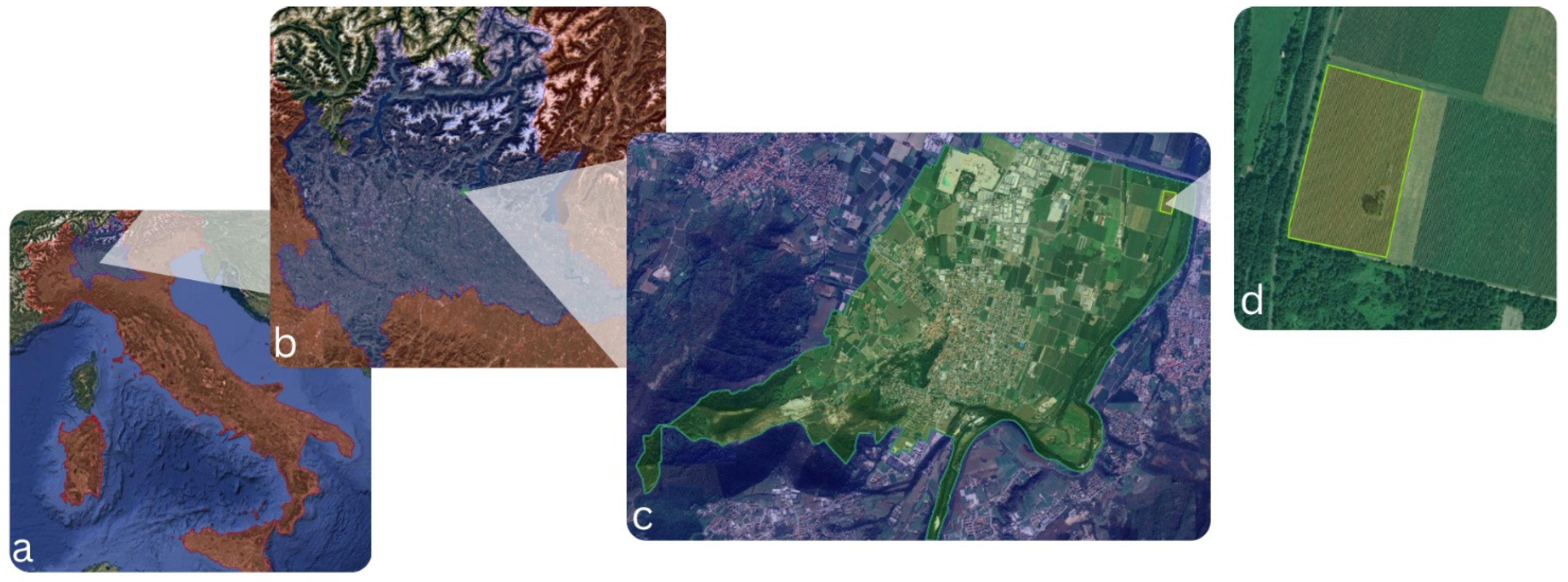

2.1. Study Site

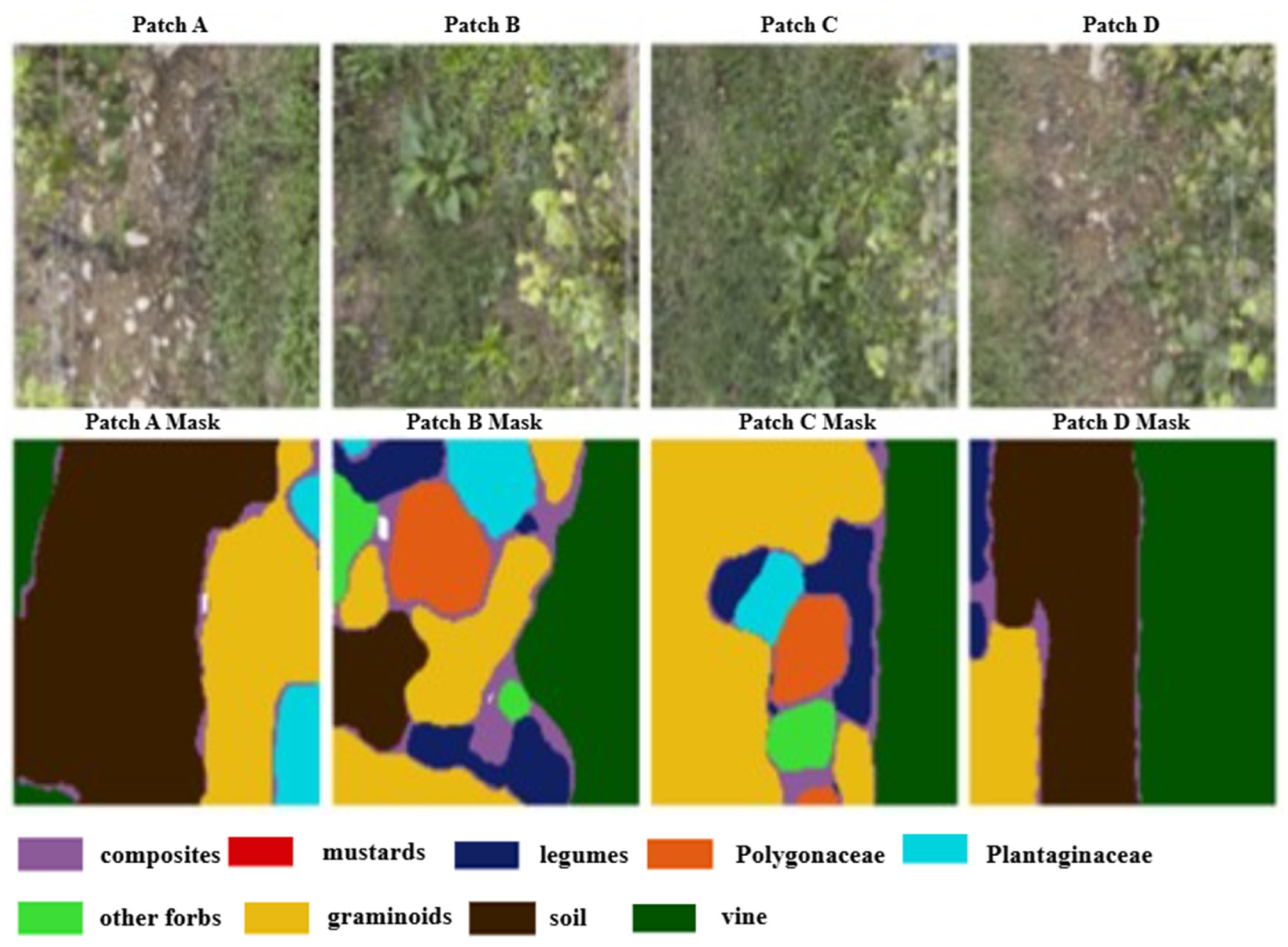

2.2. Cover Crop Communities Classification

2.3. Image Acquisition

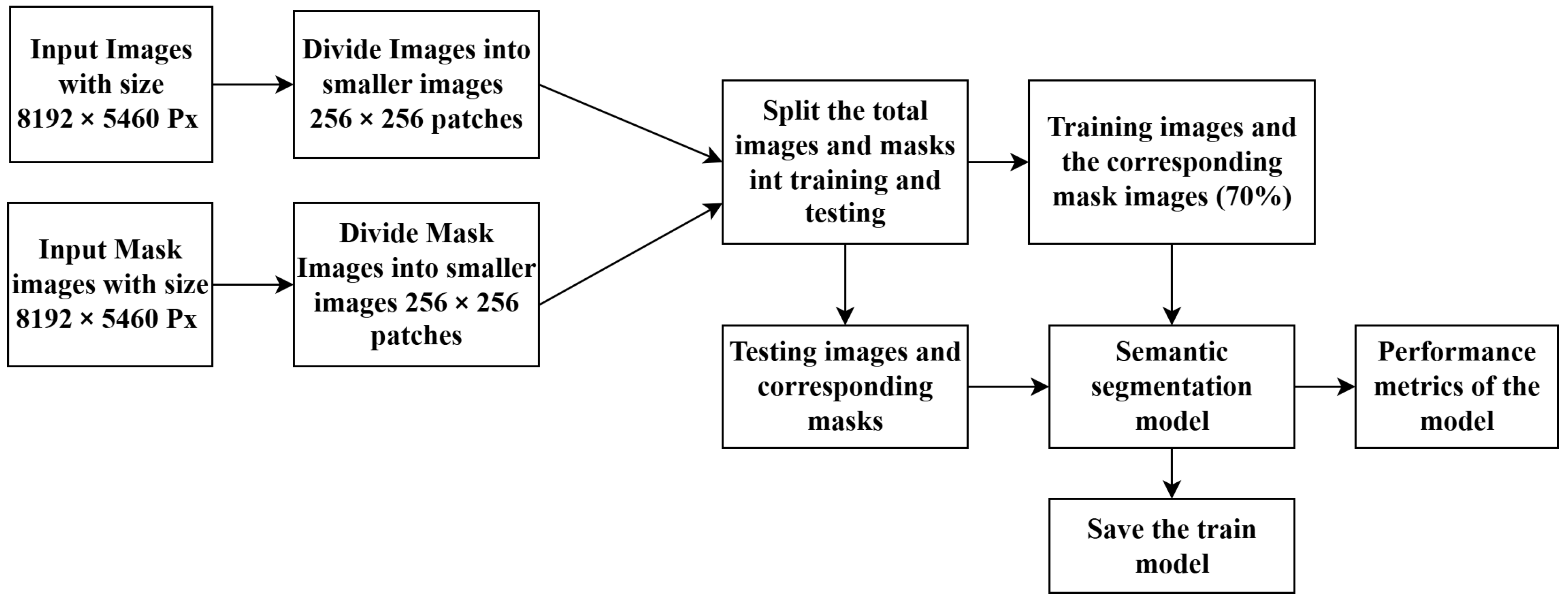

2.4. Data Preprocessing for Cover Crops Segmentation

- A plant expert manually annotated masks for each training image using Roboflow, a web-based platform for image dataset creation and management.

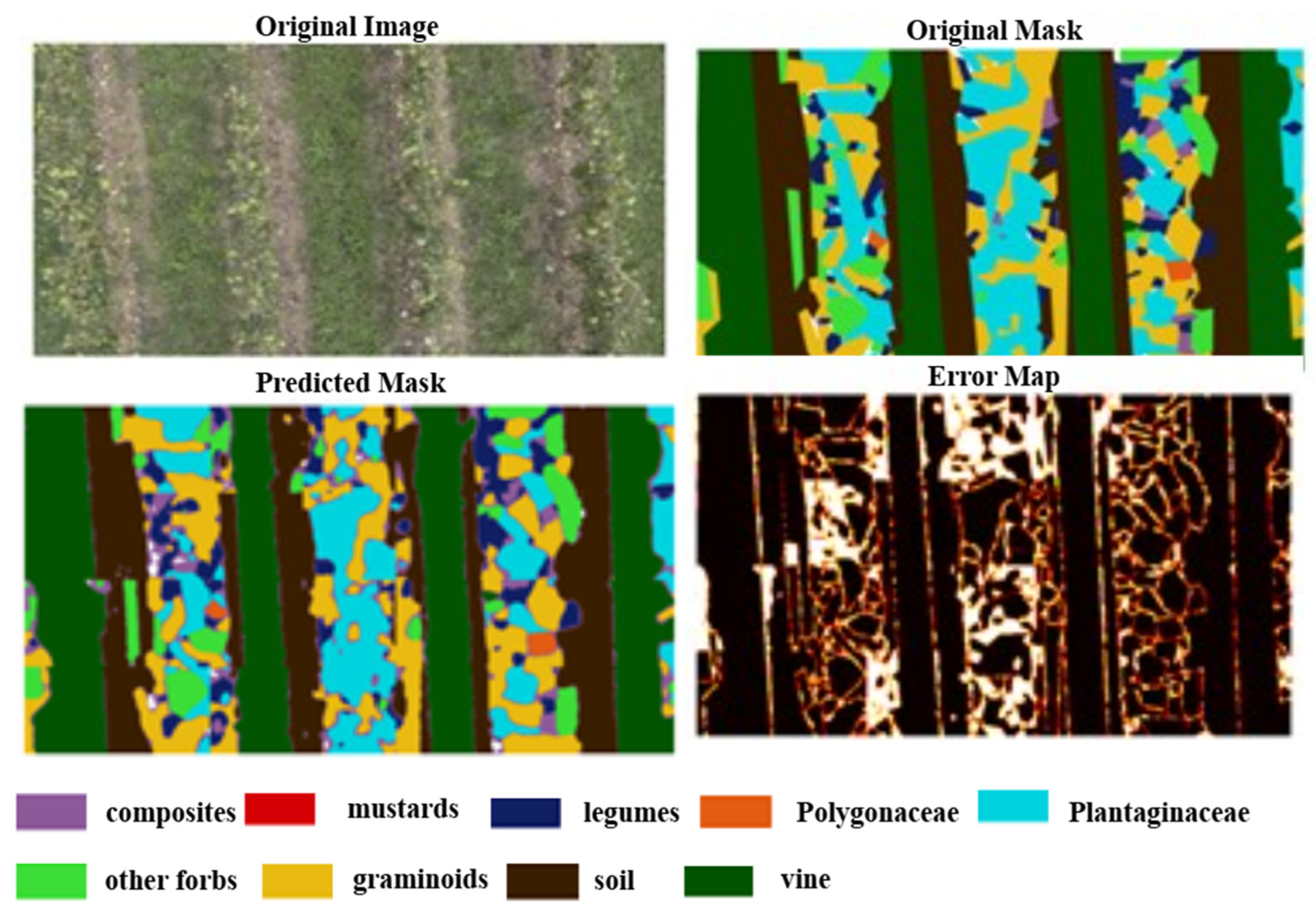

- The high-resolution images and their corresponding masks were partitioned into 256 × 256-pixel patches for training a U-Net segmentation model. This facilitated efficient image segmentation and feature identification. The trained model was then saved.

- The saved model was used for the prediction and mapping of the full-size images.

2.5. Semantic Segmentation Model

2.6. Metrics

2.7. Training Parameters

3. Results

3.1. Class Imbalance and Data Augmentation

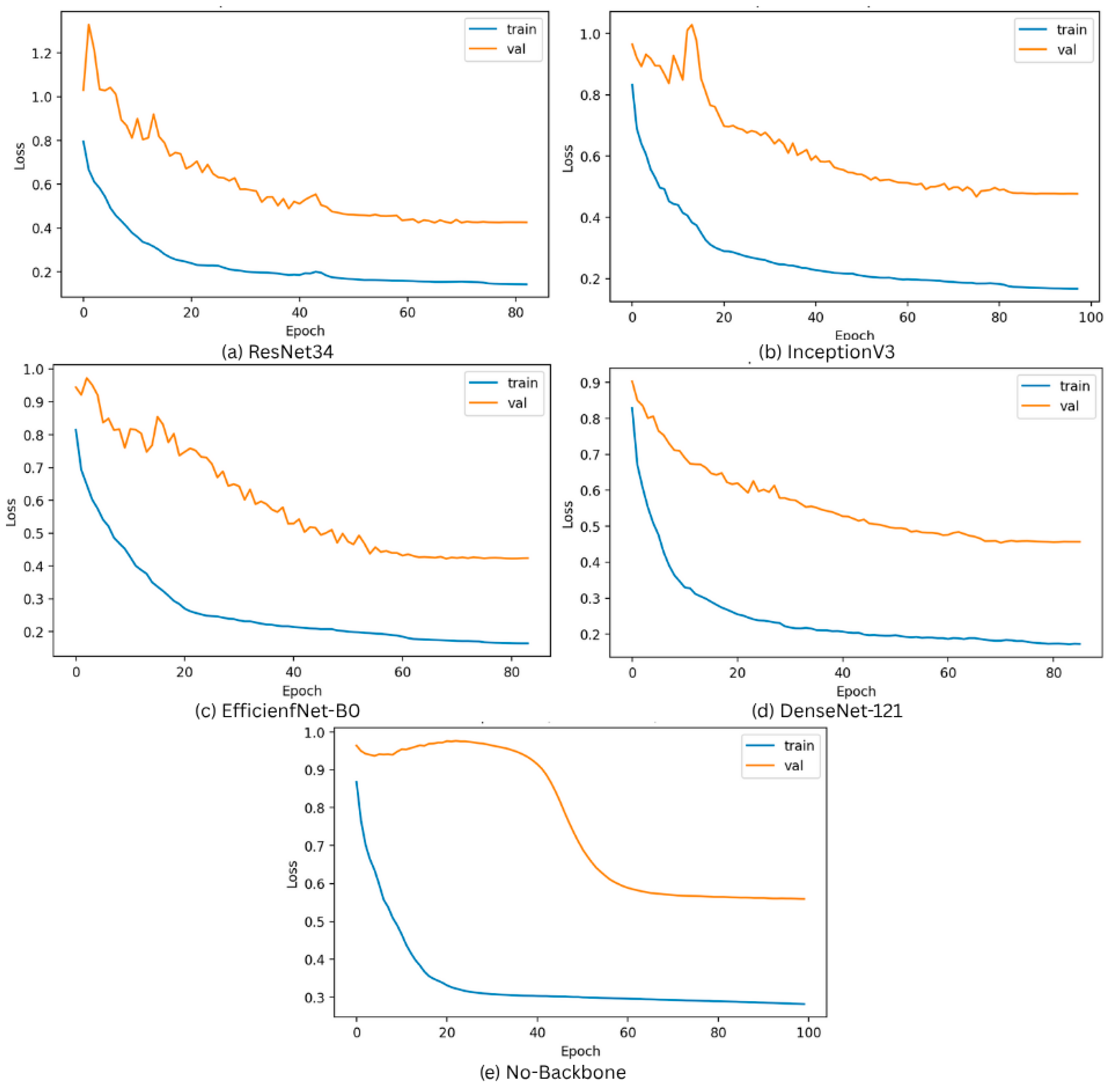

3.2. Overfitting Prevention Strategies

3.3. Model Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Homet, P.; Gallardo-Reina, M.Á.; Aguiar, J.F.; Liberal, I.M.; Casimiro-Soriguer, R.; Ochoa-Hueso, R. Viticulture and the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP): Historical Overview, Current Situation and Future Perspective. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e12099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Shaver, T.M.; Lindquist, J.L.; Shapiro, C.A.; Elmore, R.W.; Francis, C.A.; Hergert, G.W. Cover Crops and Ecosystem Services: Insights from Studies in Temperate Soils. Agron. J. 2015, 107, 2449–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, S.; Fu, B.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P.-A.; Zhao, W. Quantitative Synthesis on the Ecosystem Services of Cover Crops. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, M.; Mathulwe, L.; Gaigher, R.; Joubert, L.; Pryke, J. Native Cover Crops Enhance Arthropod Diversity in Vineyards of the Cape Floristic Region. J. Insect Conserv. 2020, 24, 133–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novara, A.; Catania, V.; Tolone, M.; Gristina, L.; Laudicina, V.A.; Quatrini, P. Cover Crop Impact on Soil Organic Carbon, Nitrogen Dynamics and Microbial Diversity in a Mediterranean Semiarid Vineyard. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeyrie, V.; Renard, D.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y.; Benyei, P.; Caillon, S.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Carrière, S.M.; Demongeot, M.; Descamps, E.; Braga Junqueira, A.; et al. The Role of Crop Diversity in Climate Change Adaptation: Insights from Local Observations to Inform Decision Making in Agriculture. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 51, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, F.V.; Stoate, C. The Legacy of Cover Crops on the Soil Habitat and Ecosystem Services in a Heavy Clay, Minimum Tillage Rotation. Food Energy Secur. 2019, 8, e00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.-L.; Swamy, M.N.S. Deep Learning. In Neural Networks and Statistical Learning; Du, K.-L., Swamy, M.N.S., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2019; pp. 717–736. ISBN 978-1-4471-7452-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bouguettaya, A.; Zarzour, H.; Kechida, A.; Taberkit, A.M. Deep Learning Techniques to Classify Agricultural Crops through UAV Imagery: A Review. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 9511–9536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărculescu, S.-I.; Badea, A.; Teodorescu, R.I.; Begea, M.; Frîncu, M.; Bărbulescu, I.D. Application of Artificial Intelligence Technologies in Viticulture. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2024, 24, 563–578. [Google Scholar]

- Epifani, L.; Caruso, A. A Survey on Deep Learning in UAV Imagery for Precision Agriculture and Wild Flora Monitoring: Datasets, Models and Challenges. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, J.; Hermoso de Mendoza, I.; Marín, D.; Orcaray, L.; Santesteban, L.G. Cover Crops in Viticulture. A Systematic Review (1): Implications on Soil Characteristics and Biodiversity in Vineyard. OENO One 2021, 55, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sundert, K.; Arfin Khan, M.A.S.; Bharath, S.; Buckley, Y.M.; Caldeira, M.C.; Donohue, I.; Dubbert, M.; Ebeling, A.; Eisenhauer, N.; Eskelinen, A.; et al. Fertilized Graminoids Intensify Negative Drought Effects on Grassland Productivity. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2441–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandvik, V.; Althuizen, I.; Jaroszynska, F.; Krüger, L.; Lee, H.; Goldberg, D.; Klanderud, K.; Olsen, S.; Telford, R.; Östman, S.; et al. The Role of Plant Functional Groups Mediating Climate Impacts on Carbon and Biodiversity of Alpine Grasslands. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, S.; Grossman, J.; Liebman, A.; Wells, S.; Sooksa-nguan, T.; Jordan, N. Legume Cover Crop Contributions to Ecological Nutrient Management in Upper Midwest Vegetable Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 712152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Wang, J.; Sainju, U.M.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, F.; Khan, A. Cover Cropping Enhances Soil Microbial Biomass and Affects Microbial Community Structure: A Meta-Analysis. Geoderma 2021, 381, 114696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A.; Estaki, M.; Úrbez-Torres, J.R.; Bowen, P.; Lowery, T.; Hart, M. Cover Crop Diversity as a Tool to Mitigate Vine Decline and Reduce Pathogens in Vineyard Soils. Diversity 2020, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-Romo, M.G.; Veas-Bernal, A.; Martínez-García, H.; Campos-Herrera, R.; Ibáñez-Pascual, S.; Martínez-Villar, E.; Pérez-Moreno, I.; Marco-Mancebón, V.S. Ground Cover Management in a Mediterranean Vineyard: Impact on Insect Abundance and Diversity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 283, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, T.; Shail, J.W. Using a Buckwheat Cover Crop for Maximum Weed Suppression after Early Vegetables. HortTechnology 2013, 23, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglécz, T.; Valkó, O.; Török, P.; Deák, B.; Kelemen, A.; Donkó, Á.; Drexler, D.; Tóthmérész, B. Establishment of Three Cover Crop Mixtures in Vineyards. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 197, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, J.T. Green Roof Plant Species Diversity Improves Ecosystem Multifunctionality. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisakti, B. Vegetation Type Classification and Vegetation Cover Percentage Estimation in Urban Green Zone Using Pleiades Imagery. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 54, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassland-Modelling-Report.Pdf. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/205002/9722562/Grassland-Modelling-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Y.; Li, W. An Improved UNet Lightweight Network for Semantic Segmentation of Weed Images in Corn Fields. CMC 2024, 79, 4413–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, T.B.; Dahal, S.; Sitaula, C.; Neupane, A.; Guo, W. Deep Learning-Based Weed Detection Using UAV Images: A Comparative Study. Drones 2023, 7, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, L.; Jiang, T.; Gao, F. MDE-UNet: A Multitask Deformable UNet Combined Enhancement Network for Farmland Boundary Segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.R.; Isaac, M.E. Functional Traits in Agroecology: Advancing Description and Prediction in Agroecosystems. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Farrell, C.; Forge, T.; Hart, M.M. Using Brassica Cover Crops as Living Mulch in a Vineyard, Changes over One Growing Season. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2023, 14, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, A.Z.; Javed, H.H.; Karim, H.; Studnicki, M.; Ali, I.; Yue, H.; Xiao, P.; Asghar, M.A.; Brock, C.; Wu, Y. Biological Nitrogen Fixation for Sustainable Agriculture Development Under Climate Change–New Insights From a Meta-Analysis. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2024, 210, e12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yuan, Y.; Song, M.; Ding, Y.; Lin, F.; Liang, D.; Zhang, D. Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery and Deep Learning UNet to Extract Rice Lodging. Sensors 2019, 19, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, T.B.; Xu, C.-Y.; Neupane, A.; Guo, W.; Shahi, T.B.; Xu, C.-Y.; Neupane, A.; Guo, W. Machine Learning Methods for Precision Agriculture with UAV Imagery: A Review. Electron. Res. Arch. 2022, 30, 4277–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cover Crop | Functional Role |

|---|---|

| Graminoids | Combating soil erosion and weed competition [13] |

| Legumes | Nitrogen fixation and the enhancement of soil health and biological fertility [14,15] |

| Mustards | Suppression of soil-borne pathogens in vineyards and nurseries [16] |

| Composites | Supporting beneficial insects [17] |

| Polygonaceae | Suppress weeds due to its rapid growth and allelopathic effects, also hosting many arthropods that contribute to pest control [18] |

| Plantaginaceae | Significant suppression of weeds [19] |

| Other forbs | Contribute to soil structure improvement and impact on the dynamics of organic carbon in the soil [20,21] |

| Image | Composite (%) | Mustards (%) | Legumes (%) | Polygonaceae (%) | Plantaginaceae (%) | Other Forbs (%) | Graminoids (%) | Soil (%) | Vine (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.56 | 0.18 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 20.06 | 3.09 | 9.92 | 29.18 |

| 2 | 7.12 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 1.50 | 0.37 | 1.03 | 6.44 | 8.85 | 25.54 |

| 3 | 7.07 | 0.00 | 7.54 | 1.91 | 18.42 | 7.73 | 15.25 | 16.44 | 25.32 |

| 4 | 8.23 | 0.04 | 6.39 | 5.47 | 12.10 | 2.90 | 13.95 | 19.68 | 28.29 |

| 5 | 9.70 | 0.12 | 1.07 | 0.76 | 1.28 | 24.27 | 4.48 | 11.29 | 36.70 |

| 6 | 1.64 | 0.82 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 2.72 | 8.38 | 4.87 | 25.44 | 44.36 |

| 7 | 4.30 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 6.18 | 12.94 | 24.22 | 4.75 | 21.69 |

| 8 | 11.32 | 0.02 | 7.09 | 6.90 | 6.86 | 7.84 | 11.97 | 15.91 | 31.06 |

| 9 | 7.64 | 0.00 | 3.69 | 0.87 | 11.68 | 15.48 | 19.85 | 16.77 | 23.76 |

| 10 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 3.36 | 3.09 | 13.53 | 5.06 | 14.30 | 20.71 | 32.00 |

| 11 | 5.60 | 0.01 | 2.51 | 2.81 | 10.70 | 9.98 | 21.69 | 17.73 | 28.39 |

| 12 | 5.72 | 0.00 | 3.81 | 3.67 | 10.71 | 4.19 | 16.06 | 21.83 | 33.90 |

| 13 | 24.56 | 0.00 | 1.64 | 0.29 | 0.95 | 15.70 | 20.71 | 0.92 | 24.24 |

| 14 | 8.14 | 0.00 | 5.25 | 0.30 | 12.59 | 4.98 | 14.86 | 23.11 | 30.42 |

| 15 | 12.87 | 0.05 | 1.71 | 1.21 | 1.52 | 23.50 | 3.65 | 7.76 | 19.29 |

| 16 | 4.31 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 6.18 | 12.94 | 24.22 | 4.75 | 21.69 |

| 17 | 8.98 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 2.45 | 0.04 | 11.97 | 7.64 | 13.33 | 27.78 |

| 18 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 3.21 | 0.66 | 17.08 | 4.53 | 15.66 | 22.07 | 28.22 |

| 19 | 8.98 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 2.46 | 0.05 | 11.97 | 7.64 | 13.33 | 27.78 |

| 20 | 7.07 | 0.00 | 7.54 | 1.91 | 18.42 | 7.73 | 15.25 | 16.44 | 25.32 |

| 21 | 8.23 | 0.04 | 6.39 | 5.47 | 12.10 | 2.90 | 13.95 | 19.68 | 28.29 |

| 22 | 11.32 | 0.03 | 7.09 | 6.90 | 6.86 | 7.84 | 11.97 | 15.91 | 31.06 |

| 23 | 5.60 | 0.02 | 2.51 | 2.81 | 10.70 | 9.98 | 21.69 | 17.73 | 28.39 |

| 24 | 3.87 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 2.61 | 0.30 | 17.42 | 10.57 | 21.57 | 34.51 |

| Backbone | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 (Correct) | Mean IOU | Jaccard Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet34 | 80.0 | 79.8 | 79.3 | 79.5 | 50.5 | 63.1 |

| EfficientNet B0 | 85.4 | 84.97 | 75.9 | 80.2 | 59.8 | 73.0 |

| Inception V3 | 82.9 | 82.3 | 82.6 | 82.4 | 53.8 | 66.4 |

| DenseNet | 83.6 | 83.9 | 83.4 | 83.6 | 52.1 | 65.1 |

| Without Backbone | 78.0 | 77.9 | 77.8 | 77.8 | 48.9 | 61.2 |

| Backbone | Class | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | IoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EfficientNet-B0 | Plantaginaceae | 0.994 | 0.917 | 0.91 | 0.841 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | Polygonaceae | 0.99 | 0.961 | 0.398 | 0.392 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | composite | 0.872 | 0.561 | 0.648 | 0.43 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | graminoids | 0.942 | 0.847 | 0.461 | 0.426 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | legumes | 0.996 | 0.747 | 0.534 | 0.452 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | mustards | 1.0 | 0.862 | 0.859 | 0.754 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | other forbs | 0.944 | 0.829 | 0.793 | 0.682 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | soil | 0.952 | 0.834 | 0.844 | 0.723 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | vine | 0.929 | 0.877 | 0.956 | 0.843 |

| DenseNet-121 | Plantaginaceae | 0.994 | 0.917 | 0.925 | 0.854 |

| DenseNet-121 | Polygonaceae | 0.991 | 0.943 | 0.473 | 0.46 |

| DenseNet-121 | composite | 0.862 | 0.544 | 0.534 | 0.369 |

| DenseNet-121 | graminoids | 0.929 | 0.632 | 0.551 | 0.417 |

| DenseNet-121 | legumes | 0.996 | 0.766 | 0.464 | 0.407 |

| DenseNet-121 | mustards | 1.0 | 0.831 | 0.825 | 0.706 |

| DenseNet-121 | other forbs | 0.945 | 0.817 | 0.801 | 0.679 |

| DenseNet-121 | soil | 0.943 | 0.805 | 0.817 | 0.682 |

| DenseNet-121 | vine | 0.935 | 0.893 | 0.951 | 0.854 |

| Inception-V3 | Plantaginaceae | 0.994 | 0.937 | 0.911 | 0.858 |

| Inception-V3 | Polygonaceae | 0.983 | 0.84 | 0.184 | 0.178 |

| Inception-V3 | composite | 0.863 | 0.517 | 0.603 | 0.386 |

| Inception-V3 | graminoids | 0.939 | 0.804 | 0.45 | 0.405 |

| Inception-V3 | legumes | 0.996 | 0.767 | 0.494 | 0.429 |

| Inception-V3 | mustards | 1.0 | 0.661 | 0.879 | 0.606 |

| Inception-V3 | other forbs | 0.925 | 0.751 | 0.748 | 0.599 |

| Inception-V3 | soil | 0.938 | 0.777 | 0.819 | 0.663 |

| Inception-V3 | vine | 0.932 | 0.888 | 0.95 | 0.849 |

| No-backbone | Plantaginaceae | 0.992 | 0.919 | 0.854 | 0.794 |

| No-backbone | Polygonaceae | 0.992 | 0.887 | 0.427 | 0.405 |

| No-backbone | composite | 0.875 | 0.58 | 0.475 | 0.354 |

| No-backbone | graminoids | 0.931 | 0.684 | 0.507 | 0.411 |

| No-backbone | legumes | 0.996 | 0.665 | 0.435 | 0.357 |

| No-backbone | mustards | 0.999 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| No-backbone | other forbs | 0.924 | 0.745 | 0.718 | 0.576 |

| No-backbone | soil | 0.923 | 0.733 | 0.772 | 0.603 |

| No-backbone | vine | 0.894 | 0.823 | 0.943 | 0.784 |

| ResNet50 | Plantaginaceae | 0.994 | 0.906 | 0.933 | 0.851 |

| ResNet50 | Polygonaceae | 0.985 | 0.963 | 0.215 | 0.213 |

| ResNet50 | composite | 0.865 | 0.544 | 0.58 | 0.39 |

| ResNet50 | graminoids | 0.939 | 0.725 | 0.549 | 0.455 |

| ResNet50 | legumes | 0.997 | 0.796 | 0.588 | 0.511 |

| ResNet50 | mustards | 1.0 | 0.874 | 0.941 | 0.829 |

| ResNet50 | other forbs | 0.938 | 0.825 | 0.748 | 0.646 |

| ResNet50 | soil | 0.946 | 0.827 | 0.808 | 0.691 |

| ResNet50 | vine | 0.918 | 0.856 | 0.954 | 0.822 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghiglieno, I.; Woldesemayat, G.T.; Sanchez Morchio, A.; Birolleau, C.; Facciano, L.; Gentilin, F.; Mangiapane, S.; Simonetto, A.; Gilioli, G. Vineyard Groundcover Biodiversity: Using Deep Learning to Differentiate Cover Crop Communities from Aerial RGB Imagery. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120434

Ghiglieno I, Woldesemayat GT, Sanchez Morchio A, Birolleau C, Facciano L, Gentilin F, Mangiapane S, Simonetto A, Gilioli G. Vineyard Groundcover Biodiversity: Using Deep Learning to Differentiate Cover Crop Communities from Aerial RGB Imagery. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(12):434. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120434

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhiglieno, Isabella, Girma Tariku Woldesemayat, Andres Sanchez Morchio, Celine Birolleau, Luca Facciano, Fulvio Gentilin, Salvatore Mangiapane, Anna Simonetto, and Gianni Gilioli. 2025. "Vineyard Groundcover Biodiversity: Using Deep Learning to Differentiate Cover Crop Communities from Aerial RGB Imagery" AgriEngineering 7, no. 12: 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120434

APA StyleGhiglieno, I., Woldesemayat, G. T., Sanchez Morchio, A., Birolleau, C., Facciano, L., Gentilin, F., Mangiapane, S., Simonetto, A., & Gilioli, G. (2025). Vineyard Groundcover Biodiversity: Using Deep Learning to Differentiate Cover Crop Communities from Aerial RGB Imagery. AgriEngineering, 7(12), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120434