1. Introduction

Plant pathology is currently a promising area of research due to technological developments, as well as climatic and economic changes. Among the many crops affected by diseases, tomatoes are a particularly relevant case study due to their worldwide high consumption rates and economic importance. According to [

1], the production of tomatoes worldwide for 2024 reached 45.8 million metric tons (MT), surpassing the total of 2023 by 1.43 million MT.

Tomatoes are highly susceptible to several foliar diseases, such as early blight, late blight, bacterial spots, and others, leading to expensive yield losses. Understanding and automatically detecting such diseases through technology is essential to protect the crops of millions of farmers and ensure a stable supply.

Over time, numerous approaches have been developed to address the detection of diseases in tomato leaves, encompassing traditional machine learning (ML) methods, such as K-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Naive Bayes (NB), and more advanced mechanisms, such as convolutional neural networks (CNN). Although these ML techniques have been extensively explored, most approaches require large and diverse training datasets to achieve robust performance. At the same time, most studies remain restricted to laboratory datasets that do not capture real world variability.

The consistency and variety of the dataset represented a major limitation in the study of plant diseases. Due to the worldwide scale of tomato cultivation, the evolution of diseases is often shaped by regional factors such as climate, soil type, temperature, and pest populations; therefore, it is difficult to develop a broadly applicable and consistent dataset.

Beyond the need for more representative datasets, a further challenge lies in the high costs associated with generating and annotating such data. In addition, training models on large datasets requires substantial computational resources, inherently resulting in higher costs. Moreover, potential conflicts of interest could arise between the entities that contributed with data to the creation of the dataset. However, it is unrealistic to think that a model trained once would yield perfect results under all the conditions mentioned above. These challenges have encouraged the exploration of alternative strategies, among which federated learning has emerged as a promising approach.

Federated learning is an increasingly utilized technique in plant disease research, offering promising new directions of study. According to [

2], FL is an innovative approach that enables decentralized training of ML models between multiple organizations, ensuring that data is retained exclusively on local devices and not transferred externally. Rather than transmitting raw data to a central server, each participant trains the model locally on its own dataset and shares only the model updates with the central server. The central server aggregates these updates to improve the overall model, ensuring the privacy of sensitive data. This decentralized framework not only enhances data security, but also enables the integration of diverse datasets, leading to improved model accuracy and generalization.

FL obviates the need to transfer data from individual devices to a centralized entity for training purposes, ensuring compliance with data privacy regulations such as GDPR. This approach allows organizations to collaborate with models without violating privacy laws, as raw data remains on local devices. In addition, FL addresses challenges associated with traditional data handling methods, which have become increasingly impractical in modern contexts. Due to stringent administrative procedures, data collection and transfer became almost impossible even within different departments of the same organization. Therefore, FL provides a viable and efficient alternative to secure, decentralized use of data, as demonstrated by [

3].

In this paper, we applied FL to detect tomato diseases under complex field conditions. This approach seeks to overcome the limitations of centralized learning by exploiting FL advantages in preserving data privacy, scalability, and efficient use of computational resources. Our work was inspired by the valuable contribution of [

4], who provided significant information on the challenge of occlusion and small lesions in the detection of tomato leaf disease. Their study offered important insights, which we extend here through the integration of biological inspiration and the application of FL. This is significant because it supports the development of more generalizable models for real-world deployment and reduces reliance on centralized infrastructures. To our knowledge, this is the first study in this direction.

This paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the work on plant disease detection, while

Section 3 describes the materials and methods used.

Section 4 presents the experimental results we achieved and

Section 5 discusses their implications. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Given the challenges of developing reliable and field-ready detection systems, numerous studies have explored a range of data acquisition strategies and ML algorithms. In this chapter, we review the most relevant contributions, with a particular focus on approaches applied to the detection of tomato disease.

Existing research relevant to this study can be divided into two main directions. The first focuses on data generation, including the creation of synthetic datasets, augmentation strategies, and field data collection protocols. The second addresses methodological innovations, with particular attention to federated learning and related collaborative training.

An important strand of research has concentrated on data generation, because ML models require training on diverse and consistent datasets to achieve reliable performances. To support research in this area, Ref. [

5] presents an open source dataset of plant images, of which 18,162 depict tomato leaves. A similar dataset is presented in [

6]. Such datasets were actively used by several authors for training models and inferring plant diseases. Ref. [

7] introduced PlantXViT, a hybrid Vision-Transformer CNN model that achieved strong performance on several plant diseases, although their evaluation was limited to publicly available datasets.Ref. [

8] developed a generic system for tomato disease detection and severity estimation, demonstrating strong performance but on a private greenhouse dataset, limiting both reproducibility and field applicability. Ref. [

9] introduced a non-invasive diagnostic system for tomato late blight based on leaf volatile organic compound profiling with a smartphone-integrated sensor array. In [

10], the authors examined how the size and diversity of the dataset influence the performance of deep learning in the classification of plant diseases, showing that larger and more varied datasets significantly improve accuracy, although his experiments remained centered on existing public datasets rather than challenging real field conditions. More recently, a lightweight hybrid model was proposed for the classification of plant leaf disease, reporting high accuracy on the public dataset [

5], but its validation remained limited to controlled conditions.

In order to increase the diversity of the dataset, augmentation techniques are applied to generate synthetic images, which help to improve the robustness and accuracy of the models. Ref. [

11] proposed a CycleGAN-based translation approach to generate additional diseased leaf images from healthy ones. They combined this data augmentation with [

5] and improved classification performance. However, such strategies still face important limitations when transferred to real life conditions. Although [

12] achieved an impressive accuracy on [

5], their dependence on controlled images highlights the gap between laboratory success and practical deployment, which motivates our focus on model evaluation with real field data.

Building on limitations identified in conventional centralized training, our second research direction explores the use of federated learning, as well as the integration of biological principles in the architecture of the model. Multiple approaches have led to promising results regarding the use of FL for the detection of leaf lesions. Ref. [

13] proposed a CNN federated learning model to detect and classify tomato leaf disease at five severity levels, facilitating targeted interventions to minimize yield loss. Ref. [

14] introduces a FL approach that preserves data privacy and ensures robustness by implementing a lightweight VGG16-based CNN enhanced with Efficient Channel Attention (ECA), optimized for edge devices. In [

15], a decentralized FL framework takes advantage of each client validation loss as a criterion for selectively sharing the model. However, previous approaches have used publicly available datasets where, despite the inclusion of some field images, most of the photos were captured under ideal laboratory conditions.

To enhance the reliability of systems in handling real-world data, E-TomatoDet was proposed in [

4], which is a transformer-enhanced, multi-scale feature detection network. E-TomatoDet addresses the challenge of disease detection in real field images, where leaf occlusion and small disease areas have a significant impact on performance. They replaced the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) backbone with a Cross-Shaped Window Transformer (CSWinTransformer) module. CSWintransformer was originally used by [

16], to enhance the ability of the model to capture global contextual information throughout the image while keeping computational demands manageable. A Comprehensive Multi-Kernel Model (CMKM) was used to extract local features at multiple scales.

Existing studies have shown significant progress in the detection of plant disease, yet most approaches still rely on laboratory datasets. These limitations highlight the need for approaches that can generalize across heterogeneous environments while respecting privacy constraints. Motivated by this gap, our work introduces a federated learning framework for tomato leaf disease detection, biologically inspired by the inherent adaptability and diversity of plant-pathogen interactions, with the aim of delivering models that are both field-ready and robust.

3. Materials and Methods

This section briefly describes the dataset employed for training and evaluation, including pre-processing and augmentation steps. In addition, this chapter subsequently outlines the complete workflow, with particular emphasis on the federated learning setup and the model training procedure.

3.1. Dataset

This article includes both public datasets and a proprietary dataset containing real-field images. The public datasets used in our approach, owned by [

17,

18], contain images for 9 different types of diseases, as well as images of healthy leaves. Most of the photos were taken with focus on a single leaf, with well-defined lesions, but there are also some images included in the dataset that do not focus solely on the leaf, incorporating backgrounds with imperfections.

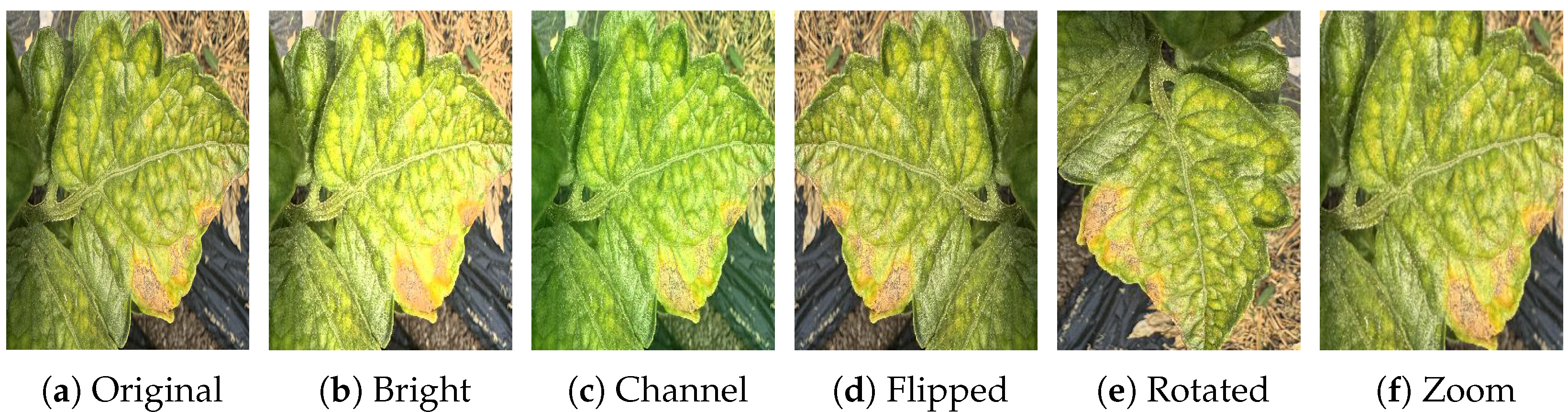

In addition to the public datasets used, a proprietary dataset was created containing images collected in the field. Our dataset was built with images collected from different geographical areas, both for outdoor and greenhouse crops. The photos were taken periodically, to capture several stages of leaf development, as well as at different times of the day, under various lighting conditions. Moreover, the dataset contains pictures taken in multiple harvests for the same greenhouses. The images contain complex backgrounds, the leaves are not perfectly centered, and they contain traces of pesticides, and even pests. Also, some leaves were photographed on both sides because the effects of the disease could also be visible on the back of the leaf. A sample of the field dataset is shown in

Figure 1.

Since the field dataset is limited in size, certain diseases are represented by only a few images. In order to increase the robustness, we first implemented data augmentation techniques, such as rotation, horizontal and vertical flipping, randomized zooming, and brightness adjustment. After applying augmentation techniques, the size of the dataset increased severalfold. Five additional images were generated based on a single reference: one with brightness adjustment, one with randomized zooming, one with channel adjustment, one flipped, and one rotated.

Figure 2 shows a sample of data generated after the augmentation of a single image.

As the images in our own dataset were insufficient and did not contain all disease classes, but only five of them, the public datasets were used to pre-train a ML model. The structure of the private data set is shown in

Table 1, while the structure of the public data set is presented in

Table 2.

The dataset containing field images was used to test the accuracy of the model and validate its feasibility in real situations. For training, in our study all images were resized to a standard resolution of 320 × 320 pixels. Up to this point, our contribution is limited to what previous authors have accomplished. The main innovation consists of the unique combination of every possible augmentation technique for trained images, coping with all imperfection and potential plan disease conditions.

Although the self-collected field dataset provides a realistic representation of the conditions of tomato leaf encountered in practice, it also exhibits several structural limitations that influence model training and evaluation. The dataset is relatively small compared to the public dataset, reflecting the difficulty of acquiring large amounts of labeled images under real farming conditions, where disease occurrences are seasonal and unevenly distributed across fields. As a result, the number of samples per class varies substantially: diseases such as Septoria leaf spot and Early blight are represented by only a handful of original images prior to augmentation, whereas others, like Bacterial spot and Late blight, are more frequently observed and therefore more abundant in the dataset. The inherent imbalance limits the intra-class variability that the model can observe during training and reduces its ability to form robust, class-specific representations for the rarer conditions. Minority classes may exhibit considerable visual overlap with more common diseases, such as similar lesion shapes, colorations, or progression patterns, further increasing the likelihood for misclassification. Moreover, because the augmented data is derived from a small set of original samples, it can only partially compensate for the lack of diversity appearances in the raw dataset.

3.2. Federated Transfer Learning

In traditional ML, train data and test data usually have the same feature space and the same data distribution. According to [

19], when the data distribution is different between the train dataset and the test dataset, the prediction can be affected. In real-life scenarios, we often deal with such small amounts of labeled data that ML models cannot be built reliably.

Transfer learning is a learning technique that is used to exploit the invariance between a resource-rich source domain and a resource-short target domain to transfer knowledge from the first to the other, as [

20] mentioned. Federated Transfer Learning (FTL) was introduced by [

21] to transfer knowledge in a federated manner, without compromising user privacy.

This paper takes advantage of collaboratively training a hybrid CNN model to implement FTL. We used a hybrid CNN that combines two biologically inspired design principles: Spiking Neural Network (SNN) for local, sparse, edge-aware feature detection and Graph-inspired receptive fields for spatial reasoning. The model is trained on the clean laboratory dataset to learn general visual perception features. To demonstrate the efficiency of the proposed model, we tested both on a sample of the lab dataset and on our own field dataset.

3.3. Methodology

Our approach consists of initializing a global model on a central server, training it on clean laboratory data, and spreading across multiple clients responsible for training the received model with local data, thus solving the security issue of data transmission. In this way, the client local data remains on the device, and only the model weights keep being transmitted periodically to the central server.

In our experiment, the main process can be divided into two phases: centralized transfer learning pretraining and federated learning across decentralized clients. For the first phase, a Graph–SNN model is trained on the laboratory dataset in order to learn general-purpose features such as lesion textures, edge patterns, and vein structures. The resulting weights serve as a shared initialization point among the clients. After the training is finished, in this phase the model accuracy is tested on both real field dataset and public available dataset.

In the second phase, the resulted pretrained model from phase 1 is deployed across multiple clients, each containing a unique subset of the training data. The subsets may differ in environmental variations, class distribution or sample counts, in order to simulate a non-IID data scenario. This phase can also be divided into two sub-phases: the transmission of model parameters and the model aggregation, as can be seen in

Figure 3.

For the first sub-phase, the central server initializes the pre-trained global Graph-SNN model from the previous phase and sends some of its parameters to the clients who join the training. In order to facilitate the FL experiment, the dataset was split into client-specific subsets, simulating decentralized data distribution. After receiving the parameters from the server, each client initializes a local model and starts training on its own private data. Once the local training is over, the clients send the resulted parameters back to the server.

When all participants complete the training, the model aggregation sub-phase starts, where the received parameters are combined and used as input for the initial hosted model. The server uses its own test dataset to validate the novel aggregated model.

In the context of distributed agricultural image analysis, the adoption of FL requires adherence to establish data-protection standards, including GDPR principles. Although agricultural images may appear non-sensitive at first glance, field-deployment environments frequently involve data collected on private farms, greenhouses, or commercial facilities, and therefore fall under regulatory expectations regarding data ownership, processing transparency, and cross-device data transfer. The training pipeline implemented in this study is inherently privacy-preserving, as all raw images remain stored on the client side and only the model parameter updates are exchanged with the server.

3.4. Model Description

The model used in this paper to implement FTL was inspired by recent efforts of [

22,

23] and represents a hybrid CNN that integrates biomimetic edge filtering mechanisms with graph-like spatial reasoning. Since standard CNNs struggle to generalize subtile disease symptoms, to address this limitation, our proposed model incorporates design principles from SNN and Graph Neural Networks (GNN).

In our work, the middle block of the architecture is described as graph-like due to the usage of dilated convolutions, which enlarge the receptive field in a manner that is conceptually similar to neighborhood expansion mechanisms found in graph-based processing. In a standard convolution, each output activation aggregates information from a compact 3 × 3 region. Conversely, a dilated convolution with dilation rate r samples pixels at intervals of r, thereby incorporating information from non-adjacent spatial positions within a broader spatial neighborhood. This introduces a sparse, non-local connectivity pattern across the image grid that resembles fixed graph adjacency relationships. Although the model does not explicitly construct or learn a graph, the dilated kernel provides an efficient grid-based approximation of graph-style receptive field propagation. Consequently, the term graph-like is used in a functional sense to denote the broadened contextual aggregation afforded by dilatation while retaining the inductive biases and computational efficiency of conventional CNNs.

The first convolutional block is described as SNN-inspired because it emphasizes local edge and contrast cues, reflecting the functional behavior typically associated with early stages of spiking and biological visual systems.The analogy refers to the effect of using shallow convolutions with small receptive fields and ReLU activation, which produce sparse, high-contrast activation maps highlighting local intensity changes. This response patterns resembles the edge-selective filtering observed in simplified SNN front-ends and early biological vision pathways. Therefore, the term is intended to denote functional affinity with these early processing mechanisms, rather than an explicit implementation of spiking dynamics.

Unlike previous work, the principles were adapted within a lightweight convolutional framework tailored for image classification and federated learning on plant disease datasets.

Figure 4 offers a visual representation of the described model. The input images were reshaped to 320 × 320 × 3 in order to preserve spatial and color details, essential for the analysis of leaf disease. The following layer performs initial downsampling to reduce spatial resolution while maintaining dominant visual features. Dilated Convolution layer records long-range spatial dependencies across the leaf by simulating graph-like receptive fields. The next layer is the SNN inspired convolution, which enables the model to respond selectively to the changes of the lesion texture and boundaries. At this point, the global average pooling encapsulates spatial information into a compact vector. The next dense layer learns high-level representations for disease classification, and the last layer produces a probability distribution over the ten given disease classes.

Although the architectural components of the proposed model are based on established convolutional operations, the novelty of this work lies in the integration and evaluation of a lightweight Graph–SNN-inspired feature extractor within a federated learning framework for the identification of plant disease. The compact model design, the receptive-field structure and the front-end edge emphasis were specifically selected to balance discriminative power with computational and communication constraints inherent to federated training. Empirical analysis across decentralized, federated, and domain-adapted phases further demonstrates how this architecture interacts with non-IID data, limited field sample diversity, and post-federation fine-tuning. Thus, the contribution of the work is not primarily the introduction of new convolutional operations, but the demonstration and characterization of this model class within a realistic FL deployment pipeline.

3.5. Federated Transfer Learning Pipeline

The FTL pipeline we implemented consists of a central server, which initializes the model described in the previous section, and four clients. The number of clients is realistic for this research area, many published experiments, especially in agriculture and healthcare, using 2 to 5 clients to simulate heterogeneous conditions. Ref. [

24] used 3 clients to detect presence of population heterogeneity in federated settings, Ref. [

25] implements a FL multi-location evapotranspiration estimation using data from 3 clients, Ref. [

26] uses 3 clients to implement federated vision-language for crop disease and pest detection.

All participants own a consistent dataset derived from the one described previously. The pipeline allows collaborative learning without exposing client data and can be structured as follows: global model initialization, local client training, model upload, aggregation and synchronization.

3.5.1. Global Model Initialization

This stage represents the transfer learning component of the framework, where the global model is initialized using parameters pre-trained on the centralized dataset. At this point, general representation features, such as edge structure, shape, texture, and lesion patterns are learned.

In this stage, the server initializes the global model with pre-trained weights resulting from centralized training of on the laboratory dataset. The pre-trained weights represent the foundational knowledge that limits the cold-start problem.

The resulting global model will be used by the participants in the federated training process. To reduce communication overhead, the server sends only the model weights to the clients, instead of the entire model.

3.5.2. Clients Local Training

Upon receiving the model weights from the server, each client loads them into its own local independent instance of the model. The clients training configuration uses a batch size of 32, 3 epochs per communication round. In this stage, the model adapts its parameters to the specific client data distribution while preserving data privacy and locality.

3.6. Model Transmission

After the local training is completed, each client sends the local model parameters to the central server. Raw data is not shared between the process entities, but only model weights, so privacy constraints are ensured. This stage represents the federated update step, where the client knowledge is transferred without exposing sensitive data, via secure communication.

Model Aggregation

Each time the server receives weights from all participants, a training round is finished. In our experiments, the model was trained for 5 rounds, and the aggregation process was triggered after each round. The server performs model aggregation using the Federated averaging algorithm (FedAvg), introduced by [

27]. In this stage, the global model parameters are updated as a weighted average of the received client models.

We define K as the total number of clients and the model weights of client k after local training in round t. Let be the number of training samples on client k. We consider N the total number of samples among all clients, defined as , and the updated weights received by the global model for round t + 1.

The weights of the global model are aggregated using FedAvg [

27] as follows:

In this way, we consider that the contribution of each client to the global model is proportional to the amount of data it holds, thus ensuring fairness among participants in the training process, especially if the data distribution differs significantly.

3.7. Synchronization

After the aggregation process is over, the resulted global model is redistributed to the participants. At this point, synchronization of the training states is necessary so that each client can benefit from the knowledge accumulated by the model following aggregation.

In this stage, each client aligns its local model with the global model, so that all participants start the next training round from the same global model state. In this way, consistency, stability, and the propagation of knowledge are ensured.

4. Results

This section presents the experimental results obtained from the proposed approach. We report the performance of the model on both laboratory and field data, followed by an analysis of accuracy, generalization, and limitations.

In our experiments, the entire model described in

Section 3.5 was stored on the server and pre-trained in a centralized manner on the dataset that contains clear laboratory data. At the end of this phase, we tested the accuracy of the model on both public and private datasets.

Using the public data set, predominantly composed of images captured under perfect laboratory conditions, we obtained an accuracy of 88% as shown in

Table 3, which is a good starting point for federated training. Since the public test dataset has the same distribution as the training dataset, the centralized model generalizes well.

Following centralized training on the public dataset, the model was evaluated on the real field dataset to assess its generalization capability. The results indicate that, despite the application of augmentation techniques to increase diversity, the accuracy obtained is lower than that achieved on the public dataset. As we can see in

Table 4, at this point, the model struggles to adapt to field domain, the performance of small classes being particularly weak.

The confusion matrix summarizes the performance of a model by comparing the predicted labels with the true labels, according to [

28]. Our model shows strong performance on the clean public dataset, but struggles on the real field one, as we can see, in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

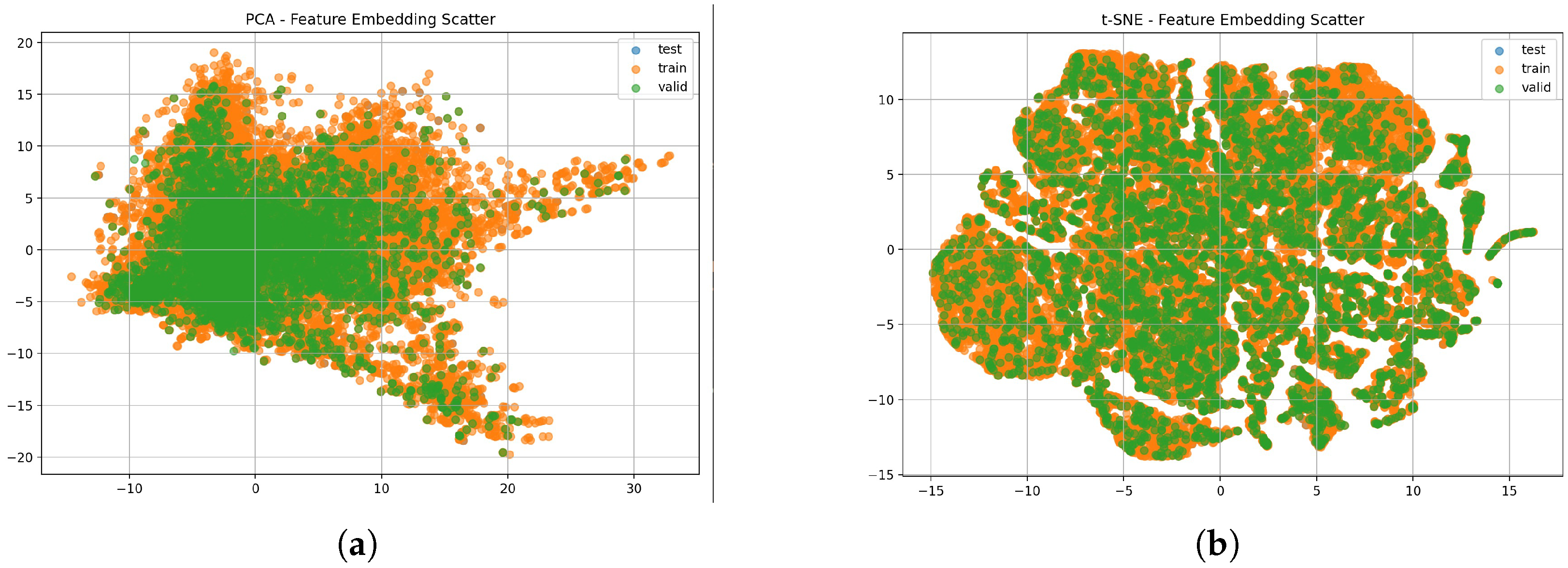

While the confusion matrix quantifies the classification performance across disease classes, additional insight into the underlying feature space can be gained by visualizing the learned representations. We implemented PCA and t-SNE to project the high-dimensional features into two dimensions and assess the degree of class separability.

Figure 6 confirms that train, validation and test sets share consistent feature distributions for the public dataset.

In the federated training process, each client performed 3 epochs of training, meaning the model completely passed through the entire training dataset 3 times before sending the resulted weights back to the server for aggregation. The training process consists of five rounds, which means that each client performs 3 epochs of training 5 times consecutively. After each round, when all clients finish the local training, the server aggregates the parameters obtained from each using FedAvg.

After the FTL training is over and the model is aggregated at the server level, we tested its performance on both the public dataset and the private dataset. As shown in

Table 5, the global model achieved 94.45% accuracy with balanced precision, recall, and F1-scores across all classes on the public dataset, demonstrating that it successfully generalized the test data.

As we can see in

Figure 7, the model improved its performance after federated training. It has learned strong disease features under controlled conditions, each category being largely correctly predicted.

Our model demonstrated consistently high precision, recall, and F1 scores across most tomato leaf disease classes, indicating robust and reliable classification performances.

The feature embedding visualizations obtained through PCA and t-SNE are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. As we can observe, train, validation, and test sets demonstrate highly consistent distributions under the FTL setup. Compared to the centralized model, where the embeddings appeared to be more dispersed, the FL approach yields a more compact and heterogeneous feature space. This indicates that FL training preserves representativeness across splits and enhances the alignment of feature embeddings.

When evaluating the private field dataset, the performance dropped significantly due to real-world noise, illumination changes, and occlusions. Since the field dataset is much smaller than the lab dataset and has fewer classes, training from scratch would overfit. Moreover, using the model as it is, it does waste knowledge, because its head expects 10 classes. When the model was evaluated directly on the field dataset, performance was limited due to the domain shift between real field conditions and controlled lab images. The model achieved only 48,6% accuracy and a macro average F1-score of 0.39, which means weak performance on minority classes such as Septoria. Although bacterial spot has a high precision of 0.88, the recall was modest, only 0.54, meaning frequent missclasifications.

As observed in

Table 6, the global model obtained after FL performs poorly on the field dataset relative to the centrally trained mode. Although this outcome may initially appear unexpected, it is well aligned with the documented behavior of FedAvg in the presence of heterogeneous and non-IID client data. Ref. [

29] demonstrated that FedAvg can exhibit substantial accuracy degradation relative to a centralized model when trained on non-IID data, attributing this gap to client drift and the dominance of locally biased gradient updates during aggregation. Similarly, Ref. [

30] systematically benchmarked FedAvg across several image-classification datasets and showed that federated models frequently underperform centralized baselines when clients have imbalanced or distributionally skewed data partitions. This behavior has been further confirmed by [

31], who demonstrated that non-IID data substantially reduce FL accuracy in image classification tasks, prompting the development of GAN-based strategies to mitigate distributional divergence. These findings align closely with our experimental results: although the model converges well on clean and homogeneous laboratory domain, the aggregated representations generalize poorly to the visually complex and highly variable field images, This behavior reinforces the sensitivity of FedAvg to distributed mismatch and highlights the need for post-aggregation adaptation strategies, such as the fine-tuning step implemented in the third phase of our experiment.

In order to adapt the global model to field conditions, a fine-tuning stage was applied after the final federated aggregation. This step was carried out centrally on the server and uses the complete proprietary dataset, which contains only five classes: bacterial spot, early blight, healthy, late blight, and Septoria leaf. We retained the backbone as a fixed feature extractor and removed the final classification layer. A new classification head with five output neurons and softmax activation was attached and trained on our private dataset. To avoid overfitting, all backbone layers were frozen and only the new head was optimized.

After applying this strategy, as shown in

Table 7, the adapted model reached 62% accuracy and a macro F1 score of 0.56. Visible improvements were produced for the healthy class, where the F1 score increased to 0.80 and Septoria, to 0.43. The confusion matrix highlights that misclassifications now occur between visually similar conditions, such as bacterial spot and late blight. By applying fine-tuning, the pre-trained features effectively realign to the field domain and enhance sensitivity to minority classes.

The comparative analysis of the confusion matrices presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 10 further illustrates the evolution of class-specific performance across the five field classes. Before fine-tuning, the predictions were broadly dispersed, with each class exhibiting substantial misclassification into multiple alternative categories. Bacterial spot showed the highest concentration of correct predictions, but also notable confusion with healthy and late blight. Early blight showed a diffuse error pattern, with samples distributed across all four other classes. Healthy images were frequently misassigned as Late Blight, while Late Blight itself showed pronounced overlap with bacterial spot and healthy. The minority class, Septoria leaf spot, exhibited minimal correct predictions and a high degree of scattering across the confusion matrix.

After the fine-tuning stage, the overall structure of the confusion matrix becomes more coherent, with a clearer diagonal trend, indicating an increased proportion of correctly classified samples across most classes. However,

Figure 10 also shows that errors persist in characteristic ways that reflect the inherent difficulty of the field domain. Misclassifications remain common between visually similar conditions, and the two minority classes, Septoria leaf spot and Early blight, although showing slight improvement, continue to exhibit widely dispersed error patterns. These observations point to underlying challenges such as the subtile visual distinctions between certain diseases, the limited diversity and imbalance of the field dataset, and the residual effects of the domain shift between laboratory and field images. The patterns visible in the fine-tuned confusion matrix provide a clear starting point for a broader analysis of model limitations, data constraints, and adaptation needs, as examined in detail in the following section.

5. Discussion

The current research explored a novel FTL approach for tomato disease detection using a biologically inspired Graph-CNN hybrid convolutional architecture. In the broader context of lightweight models used for the detection of plant-disease in distributed or federated settings, MobileNetV2 [

32] has emerged as one of the most widely adopted backbones due to its favorable balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Recent studies have demonstrated its suitability for classification of crop-diseases within federated pipelines. Ref. [

33] report that MobileNetV2 performs competitively in federated frameworks for the detection of rice-leaf disease in multiple cross-silo clients, while [

34] show that it achieves strong performance and communication efficiency in federated learning applied to multi-crop datasets. In contrast, the model proposed in our work follows a different architectural rationale. Rather than relying solely on depthwise separable convolutions for efficiency, it integrates an edge-sensitive front-end inspired by simplified spiking-processing behavior together with dilated graph-like convolutions designed to capture both fine-grained texture cues and expanded spatial context. This design targets the specific challenges encountered in real-world scenarios, particularly the non-IID nature and strong domain shift between laboratory and field environments. Our methodology was performed in three phases: centralized training, federated training, and fine-tuning stage. Each phase provided valuable insight into the generalization and efficiency of model deployment.

The study proposed by [

34] offers a valuable FL benchmark for comparison, as their experimental setup is structurally similar to ours. Importantly, the authors evaluate a broad range of pretrained deep-architectures, including VGG-16, ResNet-50, DenseNet-121, MobileNet-V2, Inception-V3, and Vision Transformer, and report consistently high results on multi-crop PlantVillage dataset [

18]. The dataset on which they performed the experiments consists of clean leaf images captured under controlled laboratory conditions with uniform backgrounds and well-balanced class distributions. Their CNN baseline achieved approximately 99.55% accuracy, but also consistently strong precision, recall, and F1-scores, often exceeding 0.98 for most disease categories. In our study, the proposed model, also CNN based, shows comparably robust behavior on the laboratory tomato dataset, achieving 94.45% accuracy and class-level precision, recall, and F1-scores typically in the 0.90–0.97 range. These results align with the performance trends observed by [

34] and reinforce that, under curated conditions, both conventional and hybrid CNN models achieve high discriminative performance regardless of architectural variations. However, on our real-field dataset, the model attains significantly low values, accuracy of 0.48 after FL and 0.62 after fine-tuning, alongside severe reductions in class level precision and recall, particularly for minority diseases such as Septoria leaf spot and Early blight. The strong performance gap across precision, recall, and F1-score confirms that FL behaves very differently when deployed on real agricultural imagery affected by nature variations, occlusions, pesticides and inconsistent illumination, conditions which are absent in the dataset used by [

34].

A second relevant point of comparison is the work of [

33], who proposed an FTL framework for rice-leaf disease classification using MobileNet-V2 and EfficientNet-B3 as backbone models. Unlike our field dataset, which contains severely underrepresented disease categories, most notably Septoria leaf spot with only 28 original samples, their dataset includes substantially more samples per class, offering a far more balanced distribution across the four target categories. Although our dataset achieves numerically similar class sizes only after augmentation, the augmented images cannot compensate for the limited morphological diversity present in the original samples. The difference in dataset composition directly affects the performance, as their models achieve approximately 98% accuracy on IID data and around 90% on non-IID partitions, while our model, trained and evaluated on more imbalanced tomato field imagery, reaches 62.02% accuracy even after fine-tuning. Furthermore, Ref. [

33] allow each client to perform its own customized preprocessing pipeline, including individual choices of data cleaning, normalization, resizing, and augmentation. This flexibility introduces a degree of client-specific data curation that tends to reduce inter-client variability. Our results highlight the challenges inherent in FL under true domain shift and severe class imbalance, conditions closer to real-world agricultural deployments.

The centralized experiments revealed a clear divergence in model performance between laboratory and field datasets. When trained on publicly available datasets, our model achieved an accuracy of 88% and demonstrated balanced precision and recall across all ten classes. However, this phase resulted in a substantially lower accuracy on the field dataset. Despite applying data augmentation, several classes, such as Septoria or Early blight, remained challenging for the model. The reduced performance of the model in this scenario highlights the difficulty of direct transfer techniques that perform well on curated laboratory dataset to real-world agricultural settings.

The results obtained in the second phase of the experiment show a distinct improvement on the lab dataset, where the accuracy increased to approximately 94%. This improvement indicates that the federated setup effectively enriched the global model without compromising the generalization capabilities learned from clean laboratory data. However, the field dataset exhibited the opposite trend, with the accuracy declining from the centralized baseline of about 60% to roughly 49% after federated learning. This reduction can be explained by the non-IID nature of the distributed dataset. The field images differ markedly from the lab images in their visual complexity, noise characteristic, and overall data distribution. During federated aggregation, updates originating from the larger and visually cleaner lab dataset have a stronger influence on the global model. Consequently, the shared model becomes increasingly aligned with the representations that are well suited to the lab domain, but less effective for capturing the variable conditions of real world environments. This reflects a well known challenge FL, where client heterogeneity and distributional mismatch can induce domain drift and gradient conflicts, ultimately leading to performance degradation on minority or more complex data sources, as shown by [

35].

Although our final field dataset accuracy of 62% does not reach the values often cited in leaf-disease classification literature, the level of performance is reasonable given the substantial domain shift and the limited amount of real field data available in our setting. Most high-accuracy reports originate from controlled or semi-controlled datasets, where models are trained and tested on visually homogeneous conditions. As noted by [

36], many of the results obtained on laboratory datasets are optimistic because they do not represent the full complexity of real-world scenarios. In contrast, the images in our field dataset were collected under genuinely heterogeneous cultivation conditions, including both greenhouses and open-field plots. Photographs were taken at different times of the day and therefore exhibit substantial variation in illumination, shadow patterns, and color temperature. In addition, many leaves have traces of pesticide residues, dust, water drops, or the presence of insects, and symptoms are often occluded by overlapping foliage or stems. These factors introduce complex background clutter and visual noise while altering the appearance and textures of symptoms. Even if data augmentation increases the number of training samples, it cannot replace the diversity contained in truly distinct real-world scenarios. Rotations, flipping, brightness adjustments, or zooming operations generate transformed versions of existing images, but do not introduce new biological or environmental variability. In our case, the field dataset contains a limited number of original images, particularly for minority classes such as Septoria, and these images already exhibit constrained symptom diversity. Since augmentation only reproduces variations along predefined transformation axes and cannot generate new disease manifestations, the ability of the model to generalize remains bounded by the limited diversity of the original dataset.

Our results also align with previous findings in the plant disease domain, where field-acquired datasets remain scarce and yield lower performance compared to controlled laboratory benchmarks. For example, Ref. [

37] highlights that the leaf classification performance decreases when moving away from controlled settings. In addition, the recent review by [

36] emphasizes that only a small subset of studies employ true field-level tomato datasets, and many of the frequently cited accuracies claims rely on more idealized conditions. In our study, the centralized model reached approximately 60% accuracy on the field dataset, which dropped to about 49% during federated training due to domain shift and client heterogeneity, but subsequently recovered to 62% following the fine-tuning stage. This progression underscores both the inherent challenge of the field domain and the practical effectiveness of our federated adaptation strategy. Under these conditions, an accuracy of 62% constitutes a realistic benchmark for deployment in agricultural environments.

Fine-tuning played a critical role in recovering the performance on field dataset. The procedure represents a post-federation domain adaptation stage, in which federated backbone is frozen and a new classification head containing five classes is trained exclusively on field data. This approach allows the model to retain the representations learned collaboratively during federated training while adjusting the decision boundaries to the specific characteristics of the field domain.

Despite the improvements obtained through head-only fine-tuning, the minority classes in the field dataset-most notably Septoria leaf and Early blight-continued to demonstrate weak performances. Although Septoria improved from F1-score of 0.22 before fine-tuning to 0.42 afterward, and Early blight reached an F1-score of 0.28, these values remain substantially lower than those achieved by majority classes. This gap indicates that the model faces considerable difficulty in learning the subtle visual representations associated with these diseases under field conditions. The challenge is compounded by the severe class imbalance present in the dataset. For example, only 28 original Septoria images were available prior augmentation, restricting the diversity of authentic symptom presentations on which the model could train.

Although augmentation increased the number of training samples, it did not generate additional biological variability or novel lesion morphologies and therefore could not fully compensate for the limited diversity of the original images from the minority-class. In addition, the fine-grained and sometimes overlapping characteristics of Septoria and Early blight lesions are often obscured by field-related factors, such as variable illumination, surface residues, and background clutter. These environmental complexities further affect the ability of the model to learn robust discriminative boundaries for minority classes.

In addition to domain shift issues, our FL setup exhibited practical challenges frequently encountered in real deployments, such as occasional missing client updates and limited class overlap between the training and evaluation datasets. Missing updates occurred when one or more clients were unable to complete a training round or upload their local model parameters. We handled these cases by performing aggregation using only the available client updates during that round, following the standard FedAvg protocol. Clients who missed a round automatically rejoined the subsequent round by downloading the latest global model. This approach prevents training interruption while maintaining robustness to intermittent client availability, a behavior widely considered essential in operational FL environments. The second issue concerned the test dataset rather than the federated clients. Although in the second phase, all clients had access to the full set of ten laboratory classes, the real field dataset used for the evaluation in phase 3 contained only 5 classes. To reconcile the discrepancy, we performed a centralized head-only fine-tuning step to align the decision boundaries of the model with the reduced class structure of the target domain, thereby mitigating the impact of limited class overlap between FL training distribution and the downstream field evaluation scenario.

To further enhance sensitivity and recall for minority classes, additional measures beyond head-only optimization are likely necessary. A first potential strategy includes the acquisition of more diverse field images for rare classes, which would increase the true biological variability available for training. Similarly, more advanced loss-balancing techniques, such as focal loss, class-balanced loss, or hard-mining, could be implemented to place greater emphasis on underrepresented samples during training, thereby encouraging the model to better learn minority-class patterns. Another promising direction is to allow selective unfreezing of deeper backbone layers during fine-tuning, enabling the feature extractor itself to adapt directly to the particularities of field-domain minority classes rather than relying solely on the classifier head for adjustment. In addition, the usage of other federated strategies, such as FedProx [

35] or related variants, could help mitigate domain drift and cross-client imbalance by allowing clients with scarce or highly variable data to retain locally adapted model components.