Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Biophysical Parameters of Sugarcane

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

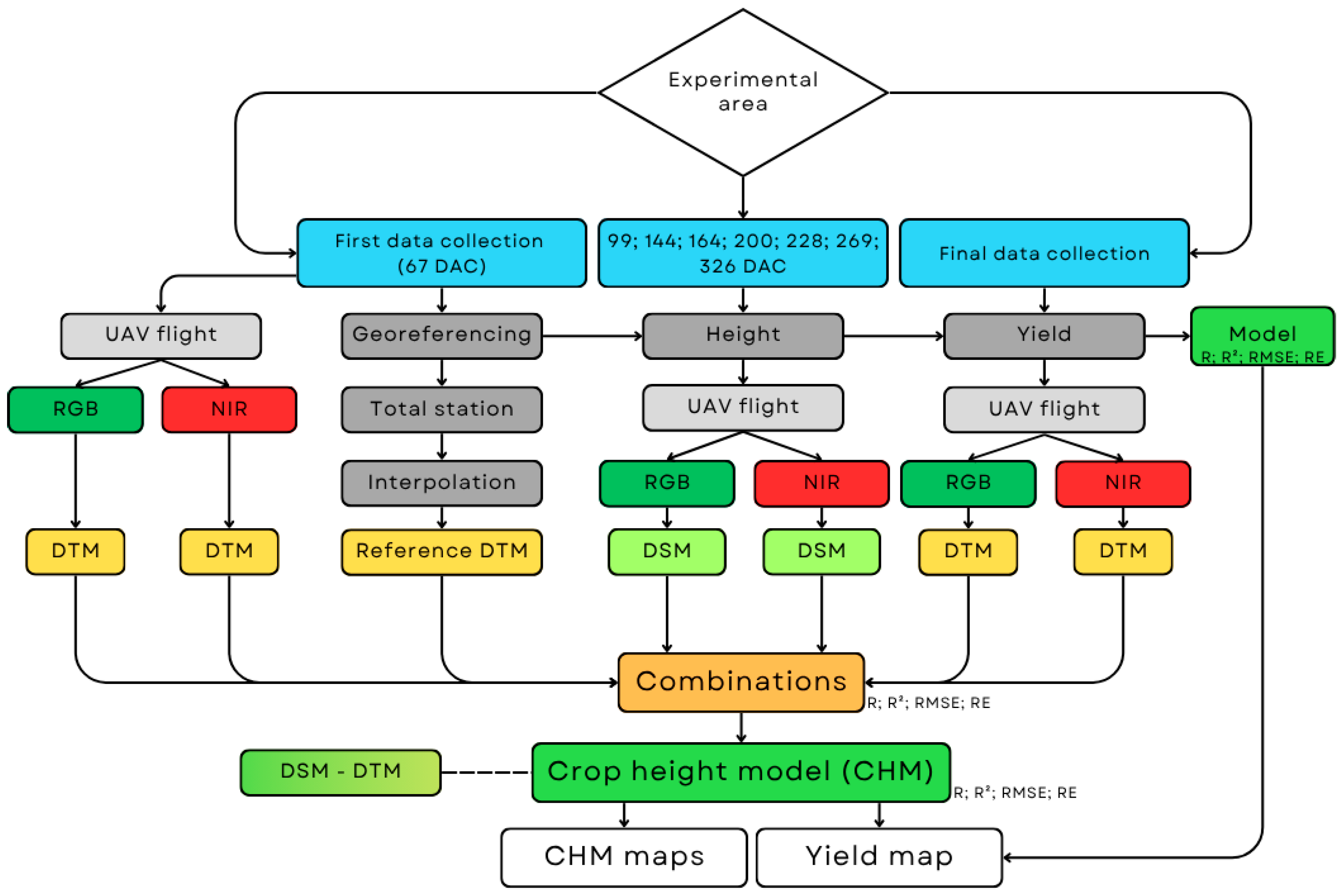

3. Materials and Methods

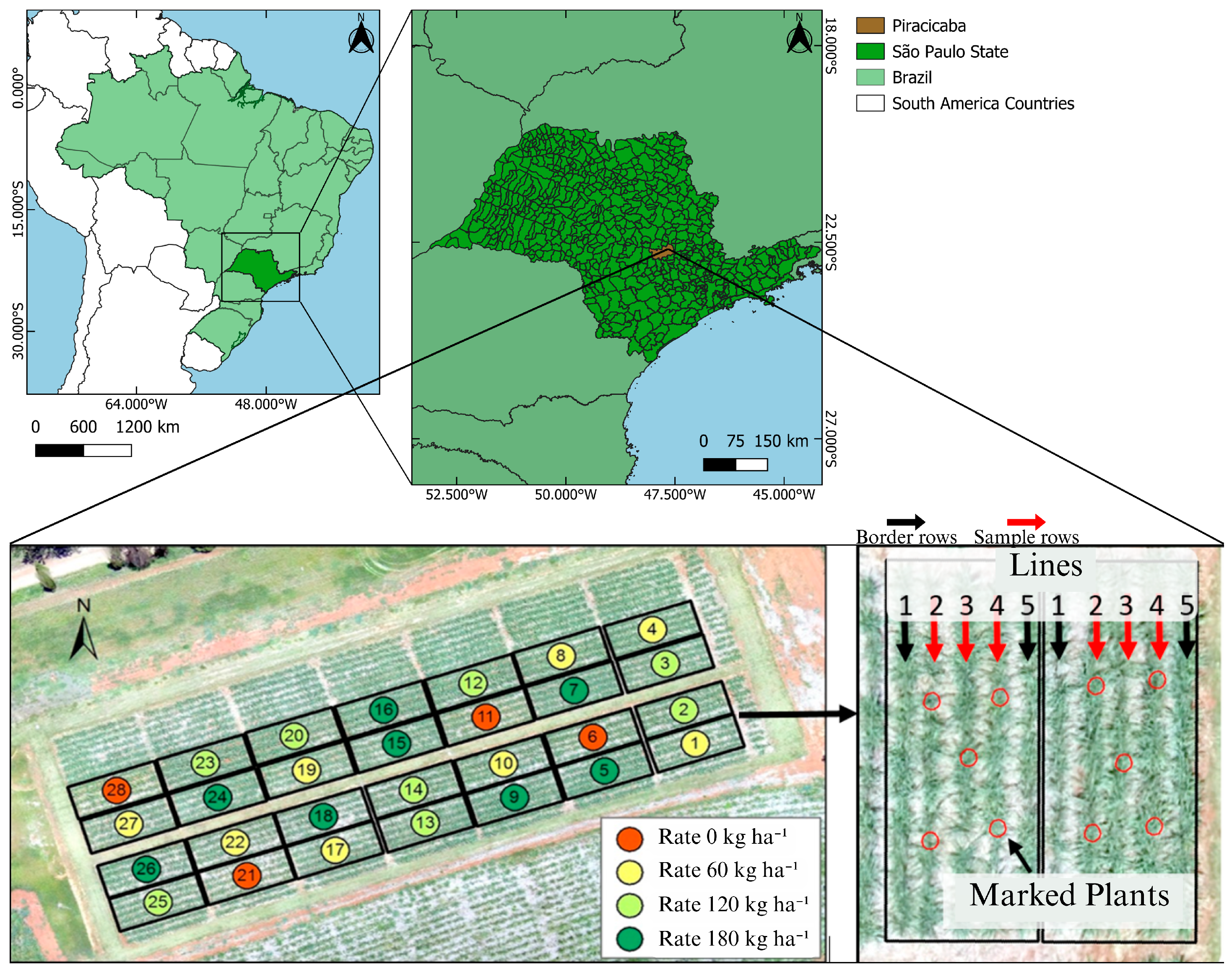

3.1. Study Area and Experimental Design

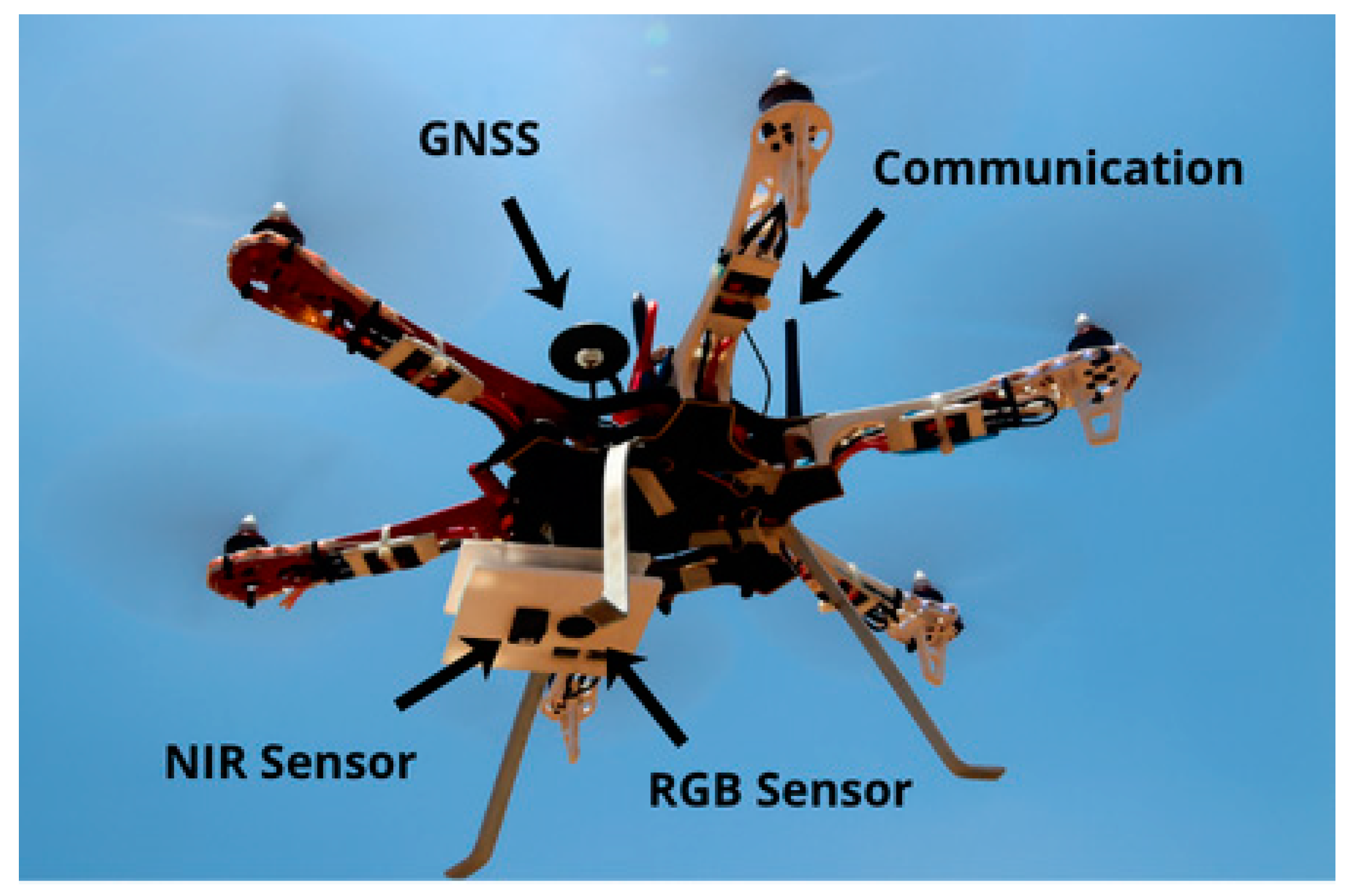

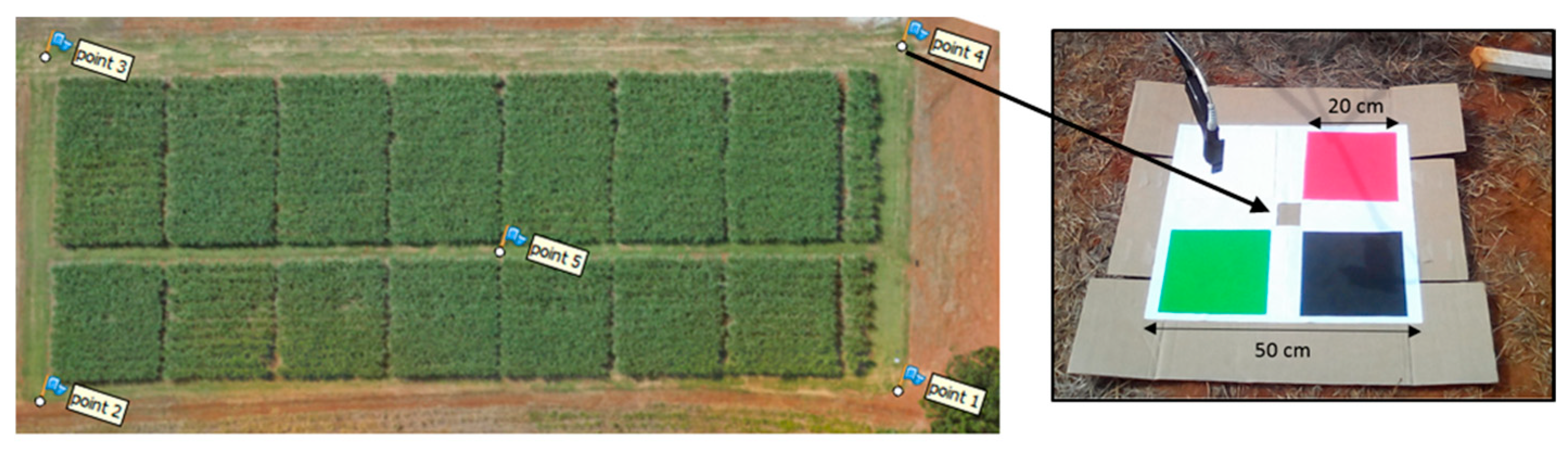

3.2. Remotely Piloted Aircraft and Image Acquisition

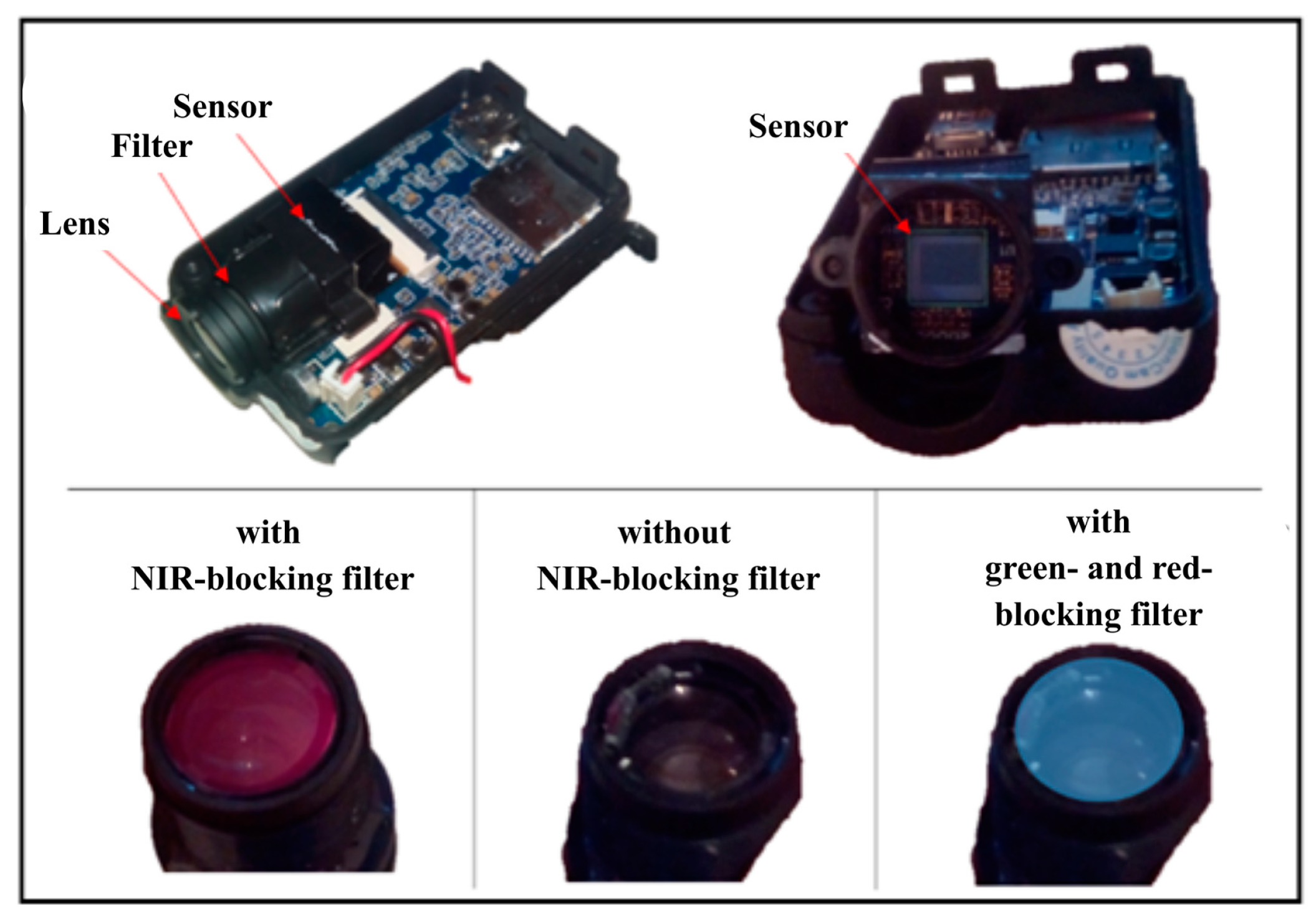

3.3. Design and Cost of the Modified Sensor

3.4. Digital Surface Models (DSMs) and Digital Terrain Models (DTMs)

3.5. Crop Height Model (CHM)

3.6. Models’ Performance and Relationship with Sugarcane Yield

4. Results

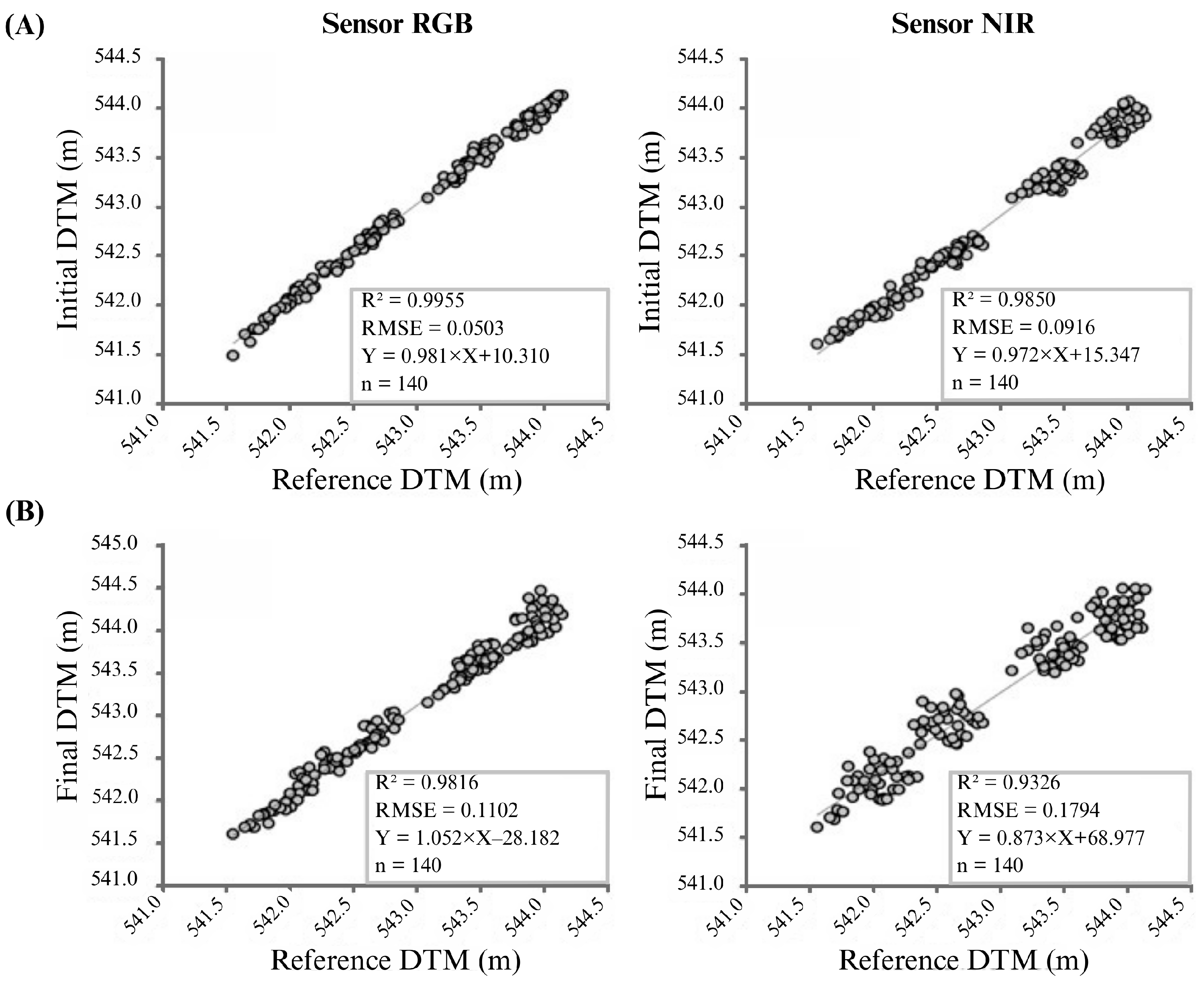

4.1. Comparison of Initial and Final DTMs (RGB and NIR) with the Reference DTM

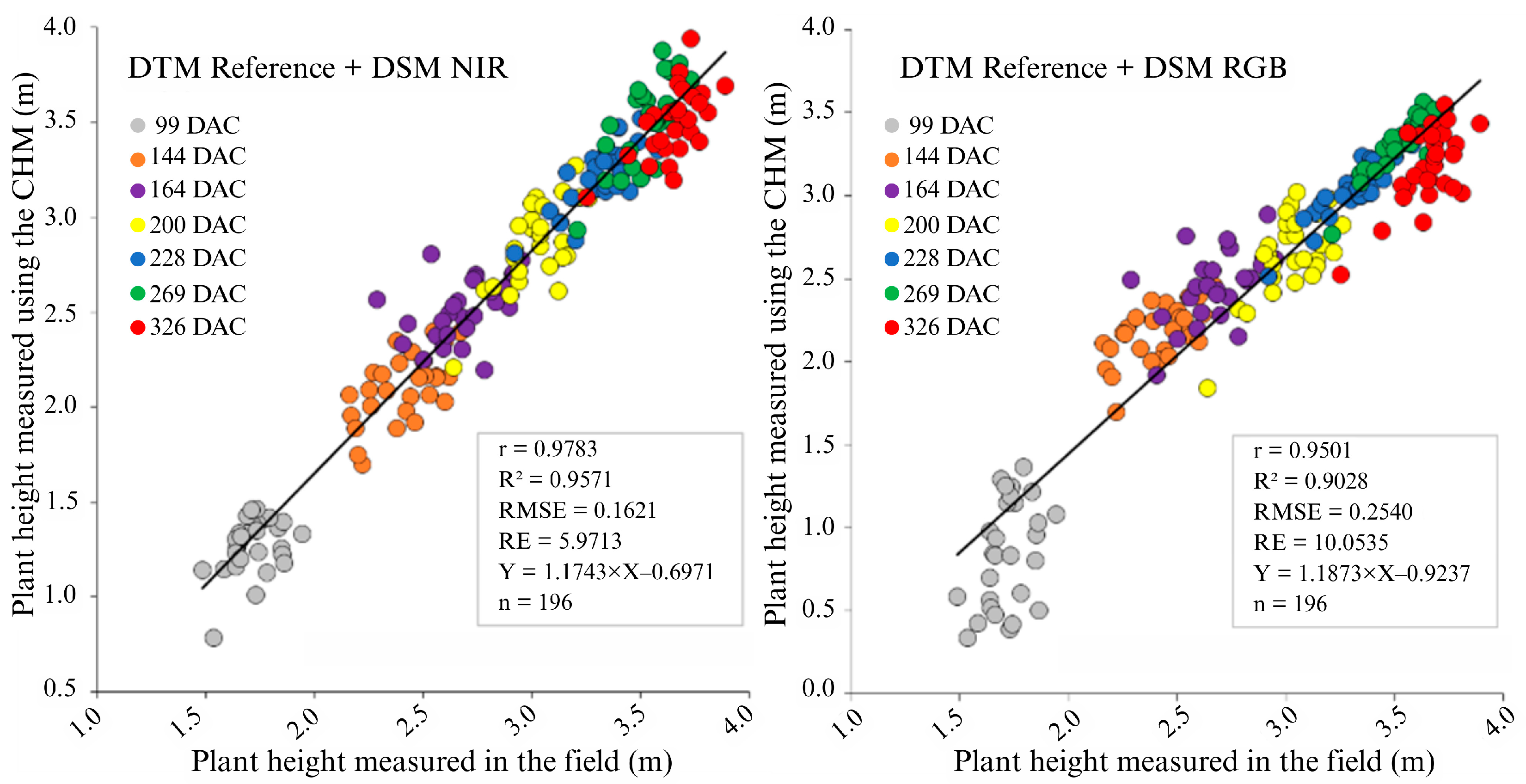

4.2. Evaluation of Crop Height Models

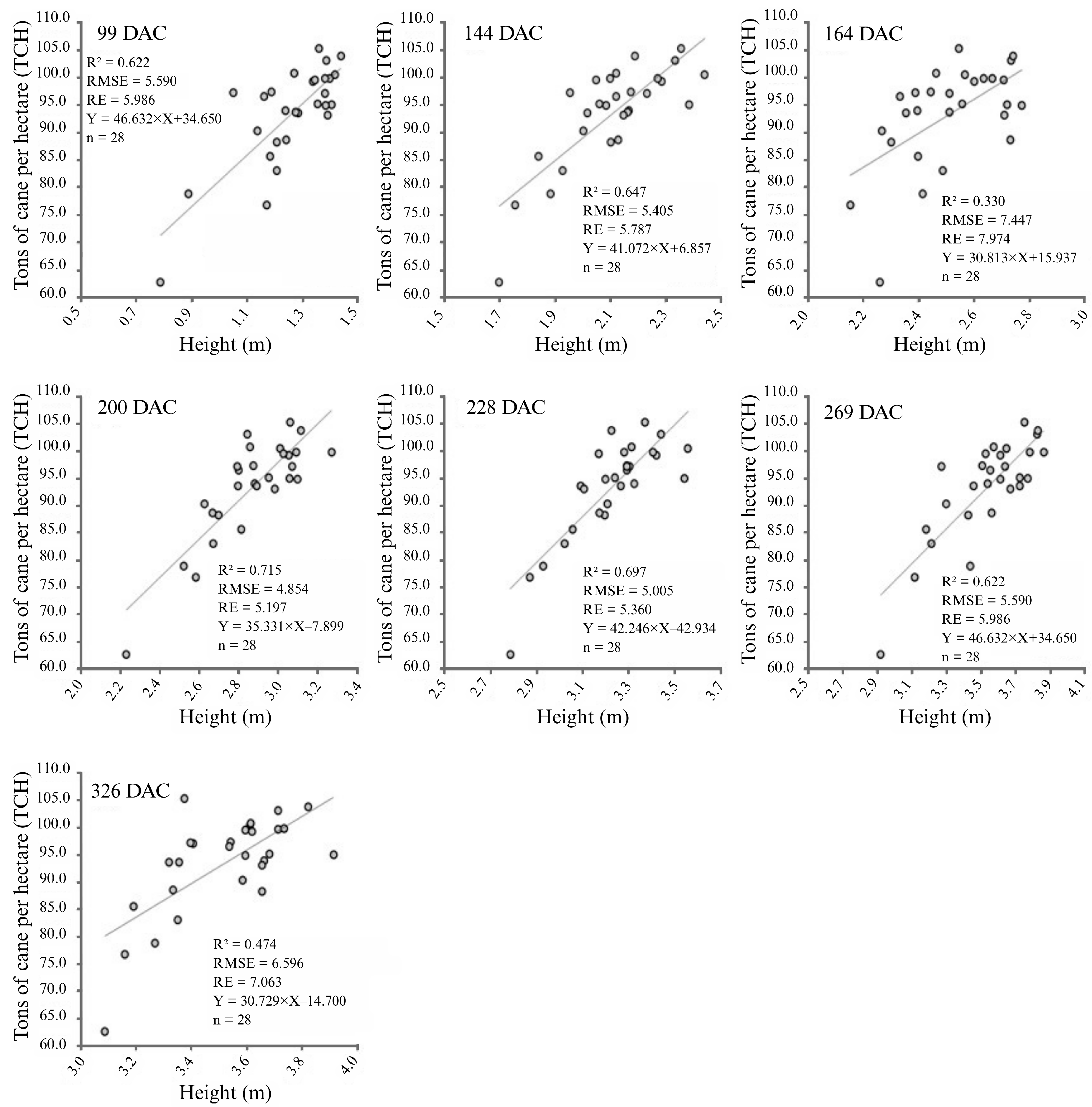

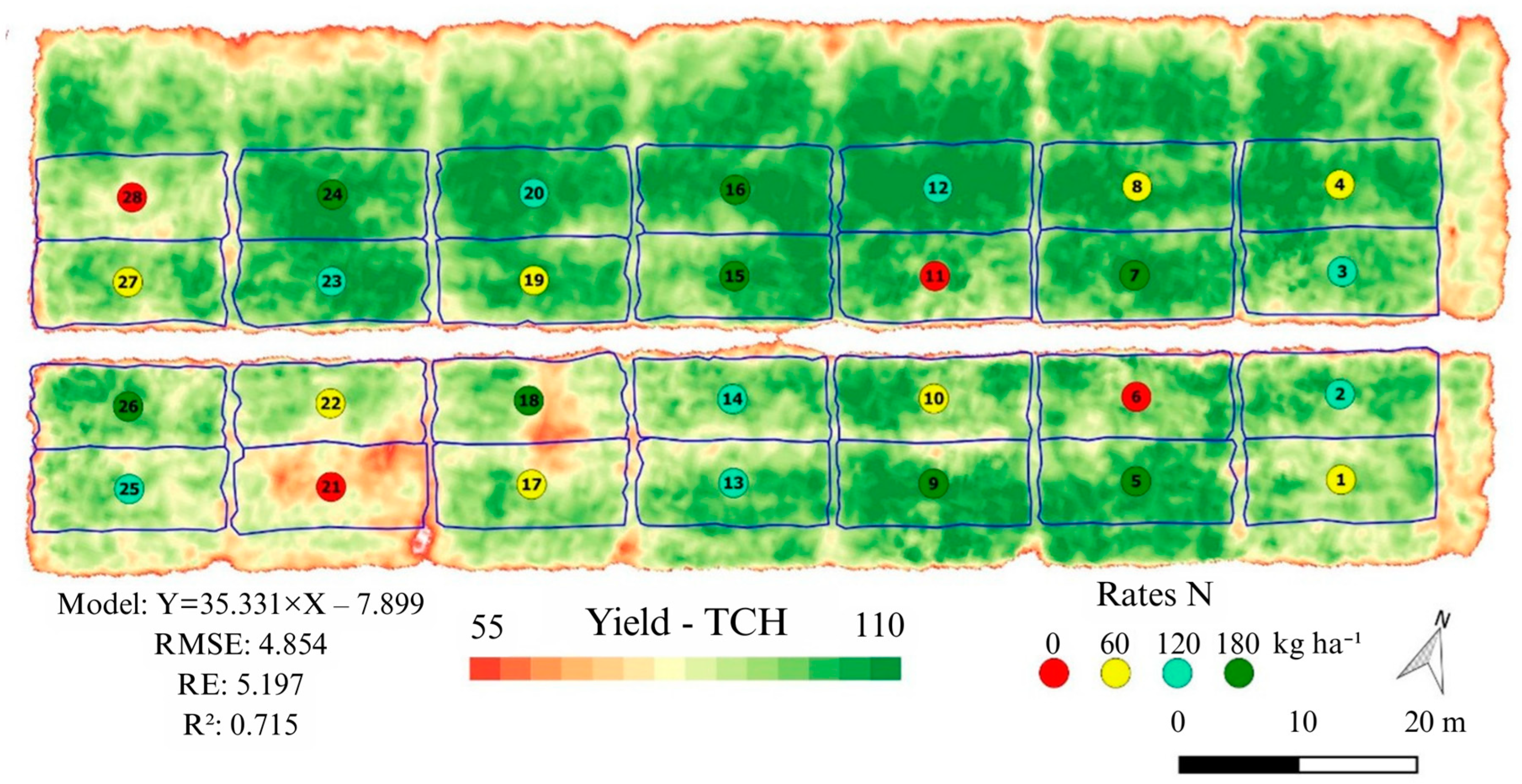

4.3. Relationship Between Crop Height and Yield

5. Discussion

5.1. Evaluation of Initial and Final RGB/NIR DTMs Relative to the Reference DTM

5.2. Assessment of Crop Height Models

5.3. Crop Height-Yield Relationship Analysis

5.4. Comparative Cost–Performance Analysis

5.5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoang, T.-D.; Nghiem, N. Recent Developments and Current Status of Commercial Production of Fuel Ethanol. Fermentation 2021, 7, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, L.P.S.; Valladares-Diestra, K.K.; Bittencourt, G.A.; Zevallos Torres, L.A.; Vieira, S.; Karp, S.G.; Sydney, E.B.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Thomaz Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. Beyond Sugar and Ethanol: The Future of Sugarcane Biorefineries in Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, L.; Chawla, I.; Mishra, A.K. A Review of Remote Sensing Applications in Agriculture for Food Security: Crop Growth and Yield, Irrigation, and Crop Losses. J. Hydrol. 2020, 586, 124905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benami, E.; Jin, Z.; Carter, M.R.; Ghosh, A.; Hijmans, R.J.; Hobbs, A.; Lobell, D.B. Uniting remote sensing, crop modelling and economics for agricultural risk management. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture: A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, A.; Thwal, N.S.; Khanal, N.; Mayer, T.; Bhandari, B.; Markert, K.; Nicolau, A.P.; Dilger, J.; Tenneson, K.; Clinton, N.; et al. Mapping sugarcane in Thailand using transfer learning, a lightweight convolutional neural network, NICFI high resolution satellite imagery and Google Earth Engine. ISPRS Open J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, Z.; Pan, B.; Lin, S.; Dong, J.; Li, X.; Yuan, W. Development of a Phenology-Based Method for Identifying Sugarcane Plantation Areas in China Using High-Resolution Satellite Datasets. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, S.K.; Chiang, T.H.A.; Happonen, A.; Chang, M.M.L. From Satellite to UAV-Based Remote Sensing: A Review on Precision Agriculture. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 127057–127076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ordoñez, J.; Cartujo, P.; Martos, V. Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) in Agriculture: A Pursuit of Sustainability. Agronomy 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, B.; Kebede, E.; Legesse, H.; Fite, T. Sugarcane productivity and sugar yield improvement: Selecting variety, nitrogen fertilizer rate, and bioregulator as a first-line treatment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zha, Y.; Shi, L.; Jin, X.; Hu, S.; Yang, Q.; Huang, K.; Zeng, W. Improvement of sugarcane yield estimation by assimilating UAV-derived plant height observations. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 121, 126159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuimphukhieo, I.; Bhandari, M.; Enciso, J.; da Silva, J.A. Estimating sugarcane yield and its components using unoc-cupied aerial systems (UAS)-based high throughput phenotyping (HTP). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som-ard, J.; Immitzer, M.; Vuolo, F.; Atzberger, C. Sugarcane yield estimation in Thailand at multiple scales using the integration of UAV and Sentinel-2 imagery. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 1581–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, F.H.; Riche, A.B.; Michalski, A.; Castle, M.; Wooster, M.J.; Hawkesford, M.J. High Throughput Field Phenotyping of Wheat Plant Height and Growth Rate in Field Plot Trials Using UAV Based Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.H.W.; Lamparelli, R.A.C.; Rocha, J.V.; Magalhães, P.S.G. Height estimation of sugarcane using an unmanned aerial system (UAS) based on structure from motion (SfM) point clouds. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 2218–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumesh, K.; Ninsawat, S.; Som-ard, J. Integration of RGB-based vegetation index, crop surface model and object-based image analysis approach for sugarcane yield estimation using unmanned aerial vehicle. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, A.; Koutras, K.; Ali, S.B.; Puccio, S.; Carella, A.; Ottaviano, R.; Kalogeras, A. Complementary Use of Ground-Based Proximal Sensing and Airborne/Spaceborne Remote Sensing Techniques in Precision Agriculture: A Systematic Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näsi, R.; Viljanen, N.; Kaivosoja, J.; Alhonoja, K.; Hakala, T.; Markelin, L.; Honkavaara, E. Estimating Biomass and Nitrogen Amount of Barley and Grass Using UAV and Aircraft Based Spectral and Photogrammetric 3D Features. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcão Júnior, J.C.; Nuñez, D.N.C. O uso de drones na agricultura 4.0. Braz. J. Sci. 2024, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.d.J.A.; Marulanda, E.E.C.; Henao-Céspedes, V.; Cardona-Morales, O.; Garcés-Gómez, Y.A. Quantification of Flowering in Coffee Growing with Low-Cost RGB Sensor UAV-Mounted. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 309, 111649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousel, J.; Haas, R.; Schell, J.; Deering, D. Monitoring vegetation systems in the great plains with ERTS. In Proceedings of the Third Earth Resources Technology Satellite—1 Symposium, NASA SP-351, Washington, DC, USA, 10–14 December 1973; pp. 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bannari, A.; Morin, D.; Bonn, F.; Huete, A.R. A Review of Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Rev. 1995, 13, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.S.; Chen, X.; Avtar, R. Assessing the Accuracy of an Infrared-Converted Drone Camera with Orange-Cyan-NIR Filter for Vegetation and Environmental Monitoring. Remote Sens. Appl. 2024, 35, 101229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Rehman, T.U.; Ma, D.; Jin, J. Precise Estimation of NDVI with a Simple NIR Sensitive RGB Camera and Machine Learning Methods for Corn Plants. Sensors 2020, 20, 3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putra, B.T.; Soni, P. Evaluating NIR-Red and NIR-Red edge external filters with digital cameras for assessing vegetation indices under different illumination. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2017, 81, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geipel, J.; Link, J.; Claupein, W. Combined Spectral and Spatial Modeling of Corn Yield Based on Aerial Images and Crop Surface Models Acquired with an Unmanned Aircraft System. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 10335–10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Varela, R.A.; De la Rosa, R.; León, L.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. High-Resolution Airborne UAV Imagery to Assess Olive Tree Crown Parameters Using 3D Photo Reconstruction: Application in Breeding Trials. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 4213–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmeister, D.; Waldhoff, G.; Korres, W.; Curdt, C.; Bareth, G. Crop height variability detection in a single field by multi-temporal terrestrial laser scanning. Precis. Agric. 2016, 17, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapuyt, F.; Vanacker, V.; Van Oost, K. Reproducibility of UAV-based earth topography reconstructions based on Structure-from-Motion algorithms. Geomorphology 2016, 260, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furby, B.; Akhavian, R. A Comprehensive Comparison of Photogrammetric and RTK-GPS Methods for General Order Land Surveying. Buildings 2024, 14, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canata, T.F.; Martello, M.; Maldaner, L.F. 3D Data Processing to Characterize the Spatial Variability of Sugarcane Fields. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Chen, B.; Lu, X.; Bai, B.; Fan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Guo, X. Integration of UAV Multi-Source Data for Accurate Plant Height and SPAD Estimation in Peanut. Drones 2025, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Singh, K.D.; Poudel, H.P.; Natarajan, M.; Ravichandran, P.; Eisenreich, B. Forage Height and Above-Ground Biomass Estimation by Comparing UAV-Based Multispectral and RGB Imagery. Sensors 2024, 24, 5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Han, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H. Estimating maize plant height using a crop surface model constructed from UAV RGB images. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 241, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja Putra, T.B.; Soni, P. Enhanced broadband greenness in assessing chlorophyll a and b, carotenoid, and nitrogen in Robusta coffee plantations using a digital camera. Precis. Agric. 2018, 19, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Sadeh, R.; Bino, E.; Polder, G.; Boer, M.P.; Rutledge, D.N.; Herrmann, I. Complementary Chemometrics and Deep Learning for Semantic Segmentation of Tall and Wide Visible and Near-Infrared Spectral Images of Plants. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 186, 106226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kior, A.; Yudina, L.; Zolin, Y.; Sukhov, V.; Sukhova, E. RGB Imaging as a Tool for Remote Sensing of Characteristics of Ter-restrial Plants: A Review. Plants 2024, 13, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, T.; Strong, J. The infrared transmission of atmospheric windows. J. Frankl. Inst. 1953, 255, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemoud, S.; Ustin, S.L. Leaf optical properties: A State of the art. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium of Physical Measurements & Signatures in Remote Sensing—CNES, Aussois, France, 8–12 January 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Winsen, M.; Hamilton, G. A Comparison of UAV-Derived Dense Point Clouds Using LiDAR and NIR Photogrammetry in an Australian Eucalypt Forest. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.P.; Barbosa Júnior, M.R.; Pinto, A.A.; Oliveira, J.L.P.; Zerbato, C.; Furlani, C.E.A. Predicting Sugarcane Biometric Pa-rameters by UAV Multispectral Images and Machine Learning. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portz, G.; Amaral, L.R.; Molin, J.P.; Adamchuk, V.I. Field comparison of ultrasonic and canopy reflectance sensors used to estimate biomass and N-uptake in sugarcane. In Precision Agriculture’13; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som-ard, J.; Hossain, M.D.; Ninsawat, S.; Veerachitt, V. Pre-harvest sugarcane yield estimation using UAV-based RGB images and ground observation. Sugar Tech 2018, 20, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, S.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Luo, J.; Li, M.; Guo, J.; Su, Y.; Xu, L.; Que, Y. The Physiological and Agronomic Responses to Nitrogen Dosage in Different Sugarcane Varieties. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-P.; Zhu, K.; Lu, J.-M.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, L.-T.; Xing, Y.-X.; Li, Y.-R. Long-Term Effects of Different Nitrogen Levels on Growth, Yield, and Quality in Sugarcane. Agronomy 2020, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, B.H. Environmental effects of n fertilizer use—An overview. Fert. Res. 1990, 26, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, J.; Ahmad, S.; Malik, M. Nitrogenous fertilizers: Impact on environment sustainability, mitigation strategies, and challenges. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 11649–116472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.; Akhtar, N. Biofertilizers: Prospects and Challenges for Future. In Biofertilizers; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Othman, N.Q.H.; Li, Y.; Alsharif, M.H.; Khan, M.A. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): Practical aspects, applications, open challenges, security issues, and future trends. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2023, 16, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghari, A.A.; Jumani, A.K.; Laghari, R.A.; Nawaz, H. Unmanned aerial vehicles: A review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.K.M.; Medeiros, S.E.L.; da Silva, L.P.; Coelho, L.M., Jr.; Abrahão, R. Sugarcane production and climate trends in Paraíba state (Brazil). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.T.A.; Silvero, N.E.; Bellinaso, H.; Gómez, A.M.R.; Greschuk, L.T.; Campos, L.R.; Demattê, J.A. Impact of soil types on sugarcane development monitored over time by remote sensing. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 1532–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, M.L.d.S.; e Lima, I.d.L.; Nilsson, M.S.; Rizzo, R.; Silva, C.A.A.C.; Fiorio, P.R. Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) Productivity Estimation Using Multispectral Sensors in RPAs, Biometric Variables, and Vegetation Indices. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Huang, Z.H.; Fu, D.W.; Fang, J.T.; Zhang, X.B.; Feng, X.M.; Xie, J.F.; Wu, B.; Luo, Y.J.; Zhu, M.F.; et al. Identification of genetic loci for sugarcane leaf angle at different developmental stages by genome-wide association study. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 841693–841705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwanpathirana, P.P.; Sakai, K.; Jayasinghe, G.Y.; Nakandakari, T.; Yuge, K.; Wijekoon, W.M.C.J.; Priyankara, A.C.P.; Samaraweera, M.D.S.; Madushanka, P.L.A. Evaluation of Sugarcane Crop Growth Monitoring Using Vegetation Indices Derived from RGB-Based UAV Images and Machine Learning Models. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyatikanto, R.; Lu, Y.; Dash, J.; Sheffield, J. Improving generalisability and transferability of machine-learning-based maize yield prediction model through domain adaptation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 341, 109652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.L.; da Silva, A.R.A.; de Moura Neto, J.M.; Calou, V.B.C.; Fernandes, C.N.V.; Araújo, E.M. Enhanced Water Monitoring and Corn Yield Prediction Using Rpa-Derived Imagery. Eng. Agríc. 2025, 45, e20240092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, G.M.; Duft, D.G.; Kölln, O.T.; Luciano, A.C.d.S.; De Castro, S.G.Q.; Okuno, F.M.; Franco, H.C.J. The potential for RGB images obtained using unmanned aerial vehicle to assess and predict yield in sugarcane fields. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 5402–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine Learning in Agriculture: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benos, L.; Tagarakis, A.C.; Dolias, G.; Berruto, R.; Kateris, D.; Bochtis, D. Machine Learning in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Updated Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (DAC) | Month | Crop Stage | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 67 | December | Emergence | 255.90 |

| 99 | January | Tillering | 89.70 |

| 144 | March | Vegetative | 174.10 |

| 164 | March | Vegetative | 95.60 |

| 200 | April | Vegetative | 11.20 |

| 228 | May | Vegetative | 79.40 |

| 269 | July | Maturation | 1.90 |

| 326 | September | Maturation | 33.00 |

| Component | Mean Price (USD) |

|---|---|

| Camera—Mobius 1 1S A2 1440P HD | 60.15 |

| Filter—650 nm Narrow Bandpass | 1.44 |

| 3D-printed camera mount | 9.00 |

| Total | 61.59 |

| Combination | r | R2 | RMSE (m) | RE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial RGB DTM + RGB DSM | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.26 | 10.36 |

| Initial RGB DTM + NIR DSM | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.17 | 6.34 |

| Initial NIR DTM + RGB DSM | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.28 | 10.70 |

| Initial NIR DTM + NIR DSM | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.20 | 7.16 |

| Final RGB DTM + RGB DSM | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.28 | 11.62 |

| Final RGB DTM + NIR DSM | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.19 | 7.44 |

| Final NIR DTM + RGB DSM | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.32 | 12.83 |

| Final NIR DTM + NIR DSM | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.26 | 9.57 |

| Reference DTM + RGB DSM | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.25 | 10.05 |

| Reference DTM + NIR DSM | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.16 | 5.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martello, M.; Silva, M.L.; Silva, C.A.A.C.; Rizzo, R.; Oliveira, A.K.d.S.; Fiorio, P.R. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Biophysical Parameters of Sugarcane. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120403

Martello M, Silva ML, Silva CAAC, Rizzo R, Oliveira AKdS, Fiorio PR. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Biophysical Parameters of Sugarcane. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(12):403. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120403

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartello, Maurício, Mateus Lima Silva, Carlos Augusto Alves Cardoso Silva, Rodnei Rizzo, Ana Karla da Silva Oliveira, and Peterson Ricardo Fiorio. 2025. "Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Biophysical Parameters of Sugarcane" AgriEngineering 7, no. 12: 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120403

APA StyleMartello, M., Silva, M. L., Silva, C. A. A. C., Rizzo, R., Oliveira, A. K. d. S., & Fiorio, P. R. (2025). Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Biophysical Parameters of Sugarcane. AgriEngineering, 7(12), 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120403