1. Introduction

In Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, annual winter grapevine pruning (mid-late October) aims to remove diseased, insect-infested, weak, and immature branches while retaining robust fruiting canes and viable buds—this optimizes vine structure, sustaining yields and health [

1].

Pruning generates over 100,000 tons of annual grapevine residues in Xinjiang, China [

2]. Current management methods (in-situ stacking/burial, open burning, mechanical crushing) all have flaws: stacked branches risk fire [

3]; decomposing biomass harbors pathogens [

4]; open burning pollutes air [

5]; crushing increases soil-borne disease risks (chemicals fail to eliminate deep pathogens) [

6]; trench burial may damage roots via fermentation heat. Thus, efficient, sustainable pruning waste recycling is urgent [

7], as it mitigates hazards, eases forage scarcity, and boosts circular agriculture—with crushing-collection being key for utilization [

8].

Advanced grape-producing regions have standardized, intelligent residue management equipment (e.g., Spain’s SERRAT, Italy’s NOBILI, France’s KUHN) [

9], but high biomass supply chain costs hinder efficiency. In China, branch crushing equipment development started late, yet growing ecological protection focus and improved waste recycling systems have spurred demand for crushing-collection machinery, expanding product varieties and advancing technology [

10]. Domestic crushers (hammer-blade, hammer-claw) include mature grape-specialized models, but integrated crushing-collection machines remain experimental and undeployed widely [

11]—a gap obvious in Xinjiang.

In Xinjiang, grape branch crushing-collection has low mechanization, poor quality, and high labor intensity [

12]; few dedicated machines exist, and general orchard models are costly, complex, and inefficient [

13]. To address this, this study developed an integrated stripping-picking-crushing-collection machine for Xinjiang’s grape cultivation and residue needs.

Based on grape wood properties, key components (collection device, crusher, transmission) were designed and analyzed theoretically. Simulations modeled crushing processes, and field experiments optimized performance (pickup rate, qualified crushing rate) via parameter adjustment. Insights into Xinjiang’s cultivation and branch characteristics refined the device; tests validated the design, aiming to improve operational quality and guide future equipment development.

2. Materials and Methods: Design and Analysis of Key Components

2.1. Material Properties of Grapevine Branches

The material characteristics of grapevine branches form the fundamental basis for designing collection and crushing machinery. Sampling was conducted during the winter pruning season in vineyards located in Jinghe County, Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. A direct field sampling method was employed to measure the morphological dimensions of the branches, including the diameters at the base, middle, and top sections, as well as the total branch length. Lateral branches were excluded from the measurements. The sampling setup is illustrated in

Figure 1. In accordance with relevant literature and considering local viticulture practices, three measurement areas were systematically selected at equal intervals along the vineyard rows. The resulting parameters characterizing the material properties of the grape branches are summarized in

Table 1, providing critical data for the design and optimization of key mechanical components.

In this study, the key mechanical parameters of grapevine branches were determined through systematic experiments: the average density of the samples was measured using the water displacement method, providing basic material parameters for simulation analysis; the average moisture content was obtained via the oven-drying method in accordance with the GB/T 1931-2009 standard [

14], which characterizes the effect of moisture on the mechanical behavior of the material; based on the compression test using a universal testing machine and fitting with Hooke’s Law, the average elastic modulus was derived, and the average shear modulus was further calculated therefrom, fully characterizing the material’s deformation resistance; in addition, the static friction coefficients between grapevine branches and steel plates, as well as between grapevine branches themselves, were measured using the inclined plane method, providing key parameters for the contact mechanics simulation of the crushing process.

2.2. Machine Structure and Working Principle

The entire machine adopts a tractor-towed operation mode, compatible with the widely used 45–70 horsepower small tractors owned by most local farmers. This approach allows full utilization of existing agricultural resources and significantly reduces the operational costs of branch recycling. The design ensures adaptability to the majority of vineyard planting patterns in Xinjiang, permitting smooth traversal between rows without damaging the grape main stems or affecting subsequent harvests. The implement is designed to achieve high operational quality even with lower tractor power output. The transmission system is optimized for efficiency, and the crushing and feeding mechanisms are well-matched to minimize fuel consumption. The machine is capable of automatically gathering scattered branches from both sides of the rows, eliminating the need for manual collection and reducing labor requirements. Crushed branches are automatically conveyed into a collection container, which can be easily transported and unloaded when full. Target performance metrics include a branch pickup rate and qualified crushing length rate of at least 90%. Given the arid, low-rainfall, and sandy conditions prevalent in Xinjiang, which impose higher demands on equipment lubrication and maintenance, the machine emphasizes structural reliability and operational stability, the machine adopts robust components to ensure reliability and ease of maintenance.

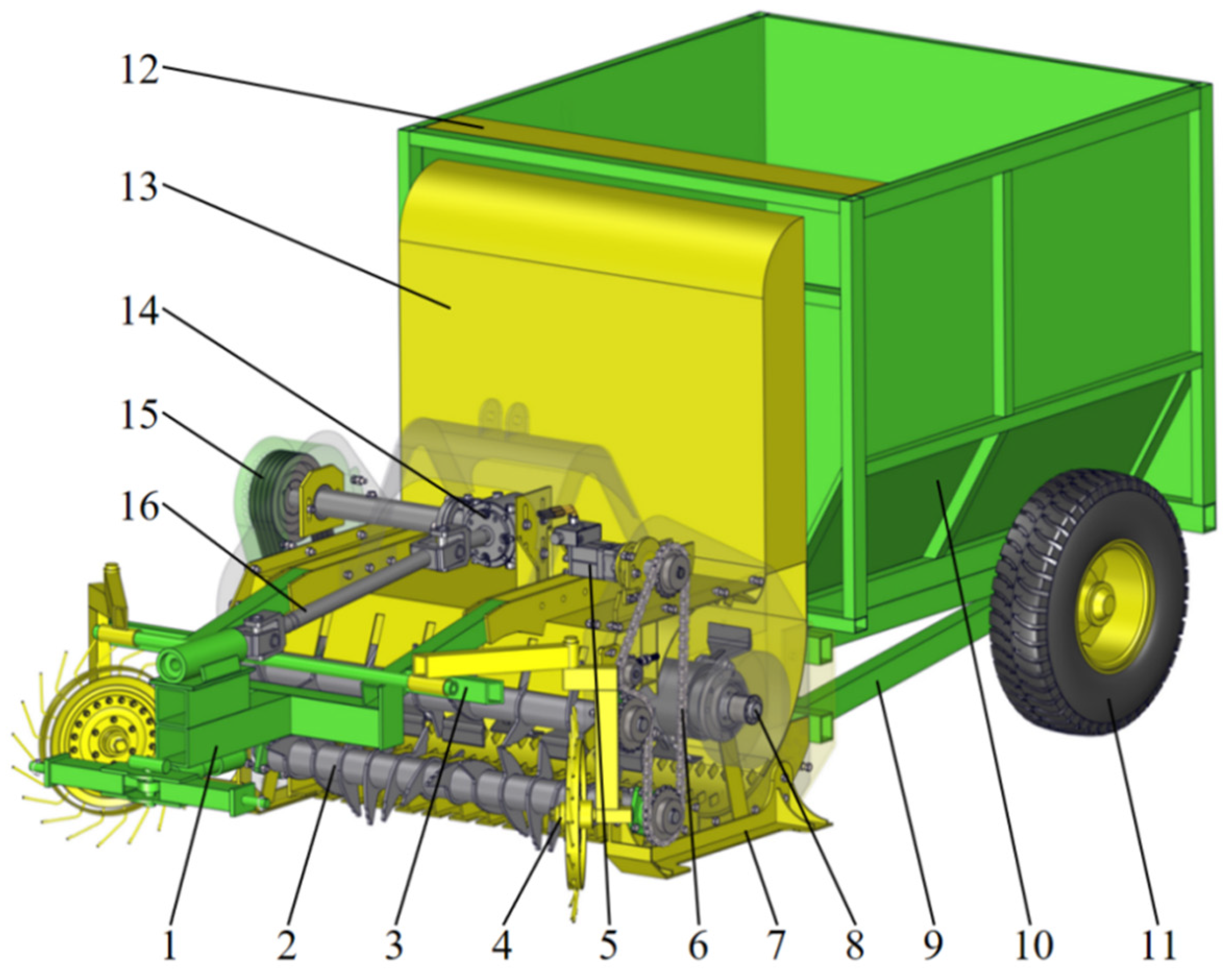

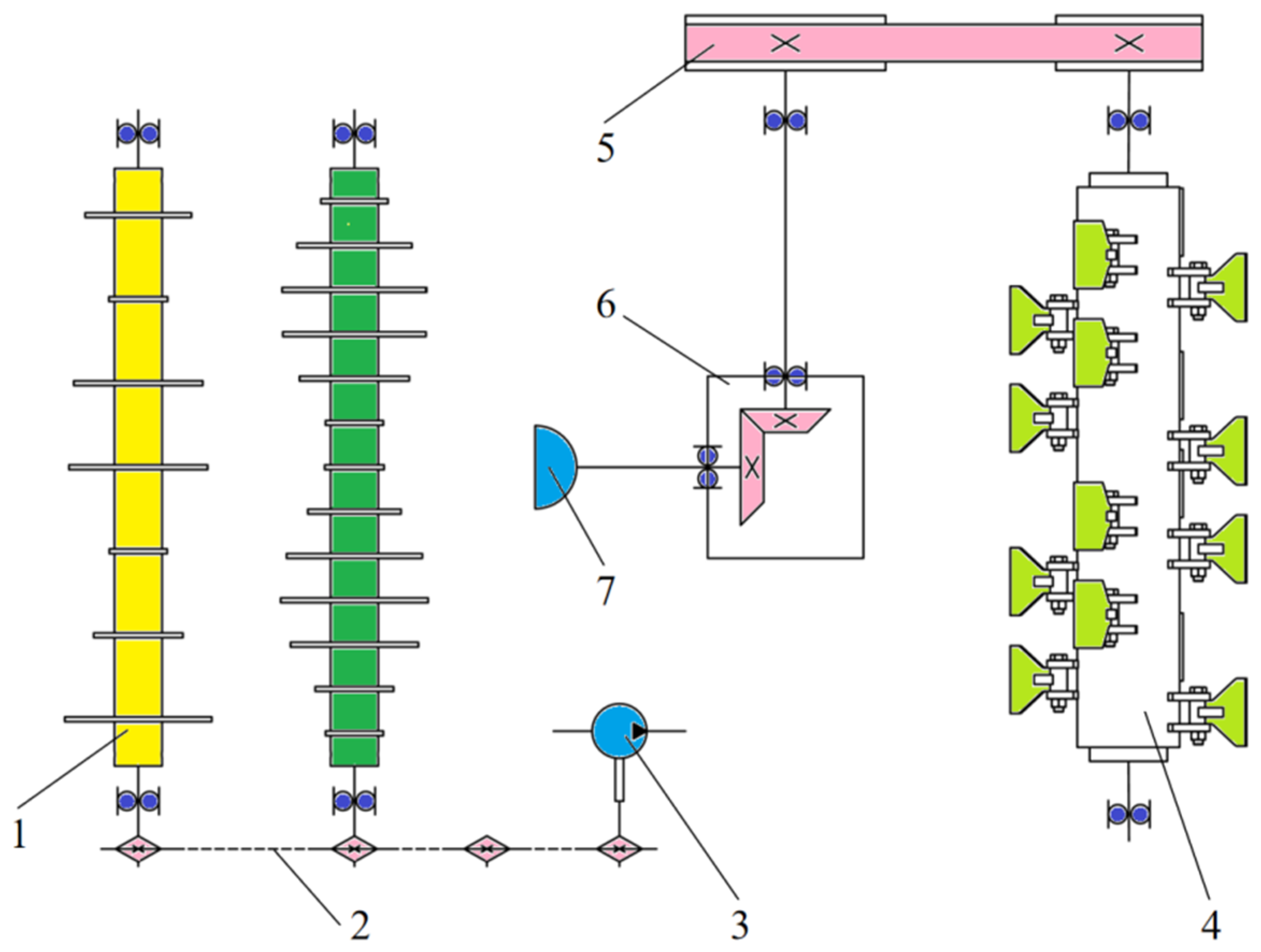

The grapevine branch crushing and collection machine comprises several key components: a gathering device, pickup device, crushing unit, and collection device, correspondingly labeled as parts 4, 2, 8, and 10 in the accompanying diagram. The gathering device (marked as 4) consists of left and right finger plates, which gather scattered branches from both sides of the vineyard rows toward the center. The pickup device (indicated as 2) includes upper and lower pickup rollers. It is driven by a hydraulic motor and chain transmission system (components 5 and 6), and is equipped with a throttle valve to allow independent adjustment of the pickup speed. The crushing mechanism (labeled 8) employs a hammer-claw design, comprising a crushing knife roller and a dedicated crushing chamber. The collection unit (marked 10) is fitted with a hydraulic lifting system to facilitate the unloading of crushed material from the collection box. The overall structure of the machine is illustrated in

Figure 2.

The traction shaft of the crushing and collecting machine is pinned at both ends to the lower hitch points of the tractor. The implement can be raised or lowered via the tractor’s hydraulic hitch system—lowered during crushing operations and raised for transport. Power is supplied from the tractor’s hydraulic pump to the crusher’s hydraulic motor, which drives the pickup roller through a chain transmission. Simultaneously, the tractor’s power take-off (PTO) shaft delivers mechanical power via a drive shaft to the gearbox, which then transmits power through a belt drive to the crushing knife roller, thereby enabling material fragmentation.

During operation under tractor traction, the equipment’s skid plate remains in contact with the ground. The pickup roller, driven by a hydraulic motor, guides the branches into the crushing chamber. Inside, a rapidly rotating crushing knife roller shreds the incoming branches. Shorter and finer crushed material is flung by centrifugal force along the discharge pipe into the collection box. Heavier and larger fragments remain within the chamber for further crushing until they are sufficiently reduced in size to be ejected. When the collection box is full, the machine is transported to a designated area. The lifting control switch is then activated to raise the collection box to a certain angle for unloading. The technical parameters of the machine are listed in

Table 2. The equipment is equipped with a crushing chamber protective cover (material: Q235 steel plate, thickness: 3 mm), a frame adaptable to transportation scenarios (transportation width: 1960 mm, meeting the requirements of relevant road transportation standards), and a discharge splash guard (height: 500 mm); the parameter design of all safety and transportation components is in line with the actual operational needs in the field.

2.3. Design of Strip Collector

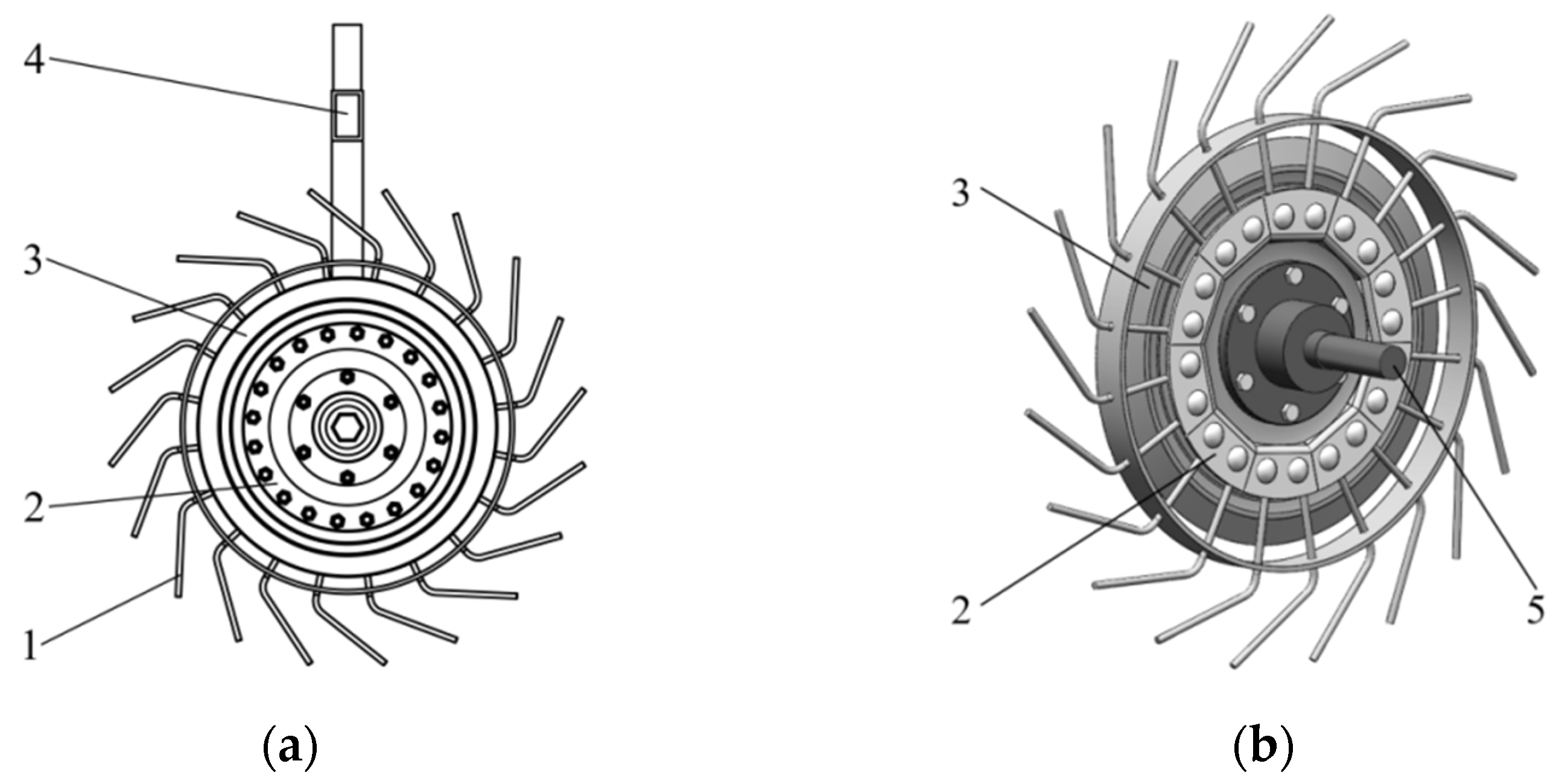

During grape branch pruning, a portion of the branches is scattered on both sides of the rows. To improve branch recovery efficiency and eliminate the need for manual gathering, the machine is equipped with finger-plate gathering devices on both sides. As the machine moves forward, the spring teeth contact the ground and generate friction, which drives the rotation of the finger plates. The resulting centrifugal motion causes the grape branches to be repositioned. Branches located at the edges of the rows are gradually guided toward the intake of the pickup device as the finger plates rotate. In this design, the finger plate radius

Rn is 310 mm, and two finger plates are installed. The spring teeth have a bend angle of 117° and a diameter of 7 mm. The angle between the finger plate plane and the direction of travel can be adjusted to accommodate different row spacing requirements. The mechanism is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The absolute speed of movement of the tooth end of the toothed disk elastic tooth during the operation of the collector bar device is:

where

V is the operating speed of the machine, m/s;

Vn is the speed of absolute motion of the tooth end of the elastic tooth, m/s;

αn is the angle between the straight line

OnC and the vertical direction, °;

δn is the angle between the disk plane and the forward direction of the branch crushing and collecting machine, °.

From Equation (1), it can be seen that the absolute motion speed Vn of the tooth end of the tooth disk elastic tooth is mainly related to the operating speed V of the machine, the angle δn between the plane of the finger disk and the forward direction of the branch crushing and collecting machine, and the parameter αn. Under the condition of a certain parameter αn, the absolute motion speed of the tooth end of the tooth disk elastic tooth decreases with the increase of the angle δn between the finger disk plane and the forward direction, and increases with the increase of the machine operating speed.

During operation of the strip collection device, the spring teeth undergo deformation upon contact with the ground. Owing to variations in branch thickness on the terrain and the circular configuration of the finger plates, the effective working width of the machine equipped with this device is less than the theoretical width. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the effective operating width of the machine can be expressed as:

where

dn is the effective operational width, m;

bn is the design distance from the center of the disk, m;

ln is the effective distance between the disk and the branch action, m; and

Rn is the radius of the disk, m.

In Equation (2), the effective action height

Hn of the finger disk is related to the radial deformation

a generated by the contact of the bullet teeth with the ground and the thickness

hn of the surface branches, and the relationship between the three is shown in Equation (3):

Combined with the machine design parameters and actual operating conditions, in this paper, the finger plate center distance bn is 1622 mm, the finger plate radius Rn is 310 mm, the thickness of the branch pile hn is 200 mm, the radial deformation of the spring teeth a is 15 mm, the angle δn between the finger plate plane and the forward direction of the branch crushing and collecting machine is 30°~60°, and substituting each parameter into the Formula (4) gives the range of the machine’s effective operating width as follows The effective working width of the machine is 1770~1878 mm.

The key parameter

N of the finger plate of the bar collecting device is solved by the relation equation:

where

K is an even number greater than 2; the angle of passage

φ is the angle, °, at which a particular elastic tooth of the finger disk turns from the point D where it enters the branch accumulation layer to the point C where it leaves the accumulation layer. Determined by the finger disk radius

Rn and effective action height

Hn:

It is known that the radial deformation a is 15 mm, the thickness of the branch accumulation hn is 200 mm, the radius of the finger disk Rn is 310 mm, and the values of the parameters a and hn are substituted into Equation (3) to obtain the effective height of action Hn is 215 mm, and the coefficient K is taken to be 8, and the values of the parameters Hn, Rn, and K are taken into Equation (7) to obtain the number of finger-disk spring teeth is 20.

2.4. Design of Crushing Unit

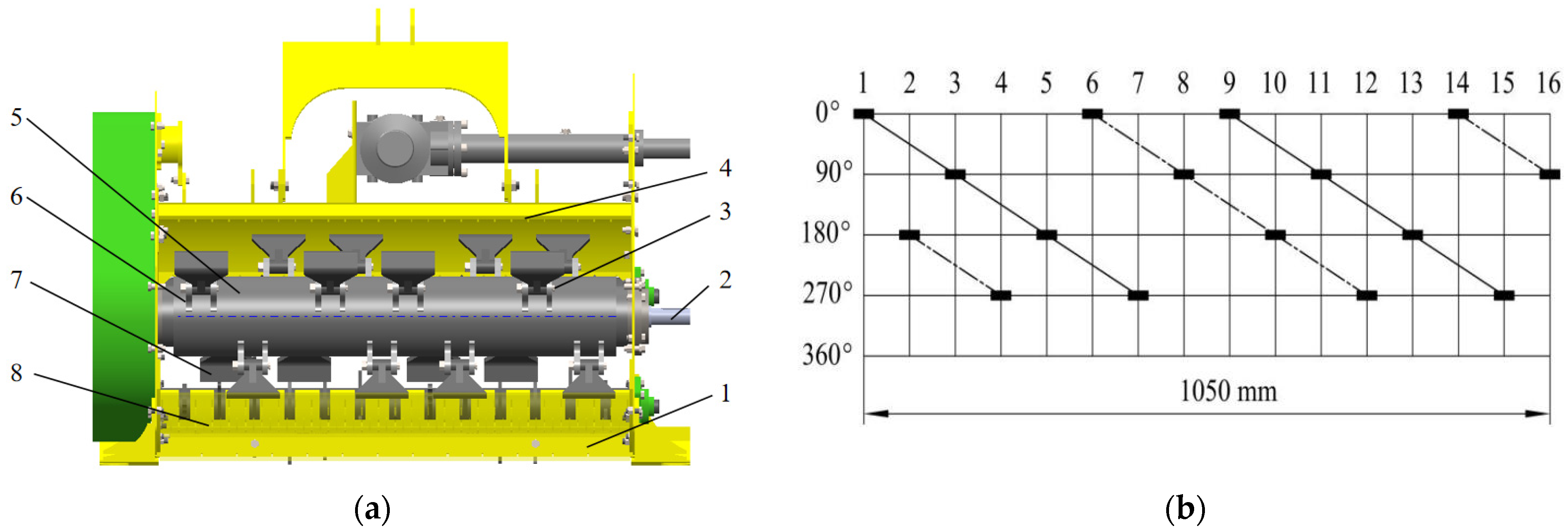

The crushing device serves as the core working component of the crushing and collection machine. It primarily consists of a crushing knife shaft, crushing knives, supports, crushing tooth plates, and fixed teeth, which are correspondingly labeled in the accompanying diagram as parts 5, 7, 6, 1, and 8. The crushing knives mounted on the shaft perform the main fragmentation function, while the toothed lining on the inner wall of the crushing chamber disrupts the circulating layer of crushed material. This design reduces the tendency of fragmented biomass to rotate along with the knife roller, thereby minimizing ineffective energy expenditure and ensuring thorough crushing of the branches within the chamber. During operation, the high-speed rotation of the knife roller cuts and crushes the incoming branches. The resulting fragmented material is then discharged along the outlet pipe under centrifugal force generated by the rotating knives. As a result, the crushing unit integrates both fragmentation and conveyance functions, eliminating the need for a separate fan to expel the crushed material. The structure of the crushing device is illustrated in

Figure 4a.

The number of hammer claws has a certain degree of influence on the operation stability, service life and operation efficiency of the crushing device. If the number of hammer claws is too large, the power consumption will increase; if the number is too small, the qualified rate of the crushing length of the branches will decrease, which will affect the operation effect [

15]. Therefore, it is necessary to select a suitable number of hammer claws. The relationship between tool density

c and pulverizer operating width

L is shown in the following Formula (8) The number of hammer claws can be determined by Formula (8).

where

c is the hammer claw density, piece/cm;

n is the number of hammer claws, pieces;

L is the width of crusher operation, mm.

The hammer claw density is typically set at 0.07 to 0.13 pieces per centimeter. With this machine’s theoretical working width of 1300 mm substituted into Formula (8), the number of hammer claws n is calculated to be 9 to 18 pieces. Considering comprehensively vibration control (reducing dynamic unbalance force during high-speed rotation), energy consumption optimization (18 or more hammer claws would make the power demand of the knife roller exceed the load capacity of the power take-off shaft), and mechanical balance (16 hammer claws arranged in a double-helix symmetric pattern, which can reduce operating noise), the number of hammer claws is finally determined to be 16. Moreover, the hammer claws are made of 40Cr material, and their hardness reaches 28-32HRC after quenching and tempering treatment.

A double-helix arrangement is adopted for the tool configuration to significantly reduce machine vibration. The layout of the knife shaft is illustrated in

Figure 4b. The shaft is equipped with 16 hammer claws distributed uniformly along its axial direction, with an interval of 210 mm between adjacent claws. On the helical paths, the distance between adjacent hammer claws on the same helix is 140 mm, and the initial phase angles of the two helices are set at 0° and 180°, respectively. Four rows of hammer claws are uniformly arranged around the cylindrical surface of the crushing knife shaft, with four claws in each row. This configuration ensures a consistent number of hammer claws engaged simultaneously during operation, thereby minimizing fluctuations in working resistance.

2.5. Tool Dynamics Analysis

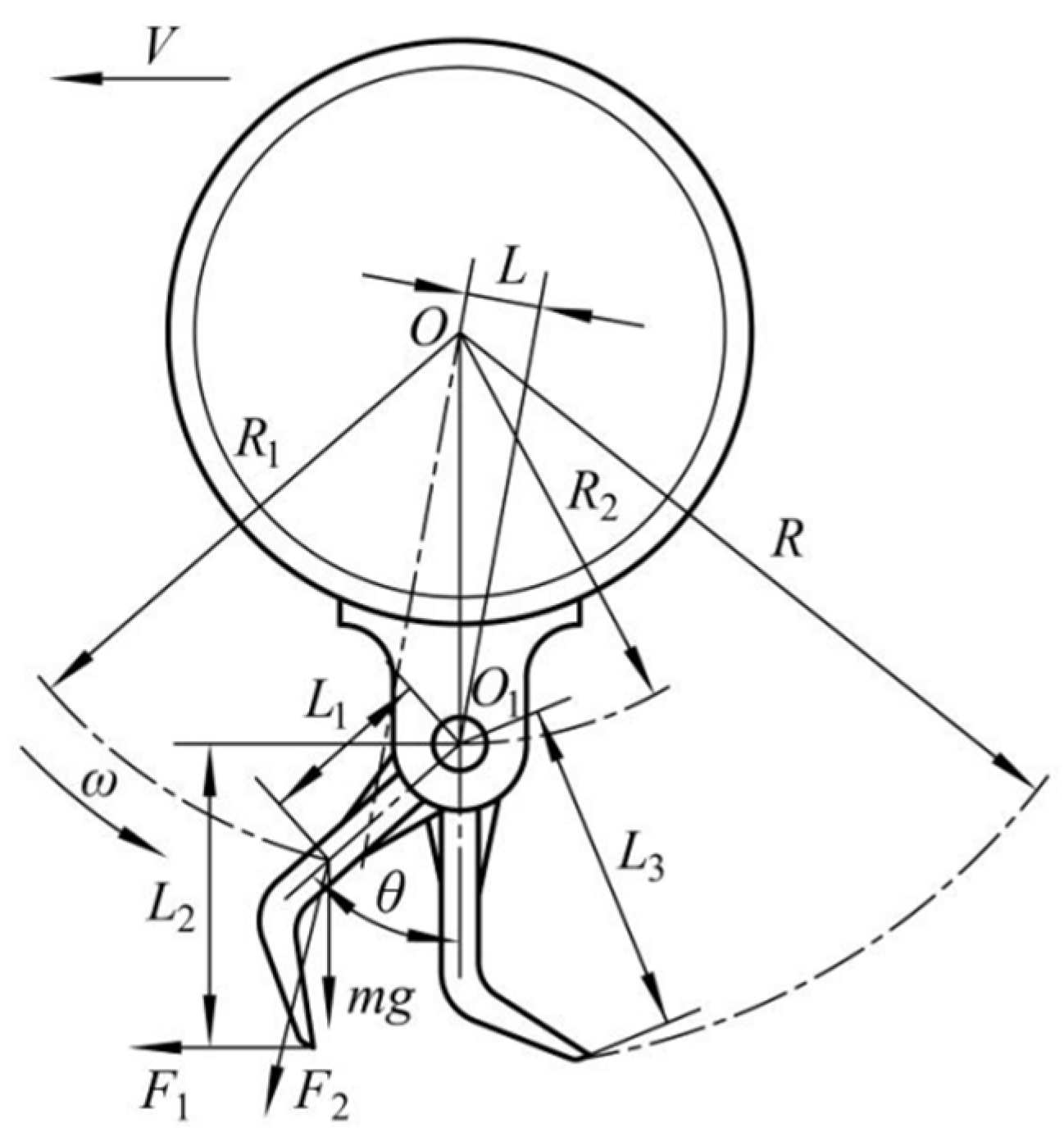

During the crushing process, the hammer claw is subjected to the following mechanical analysis: the crushing knife roller rotates at high speed, and centrifugal force causes the hammer claws to remain approximately in a radial orientation. When crushing grape branches, the tip of the hammer claw experiences a uniform cutting resistance force, denoted as

F1. Part of the kinetic energy is expended to overcome this resistance, resulting in a deflection of the hammer claw by an angle θ. Assuming negligible friction between the pin and the hammer claw, the contact force exerted by the pin on the hammer claw passes through the pivot point

O1, producing zero moment about

O1 and thus not contributing to rotational resistance. The force analysis of the hammer claw is illustrated in

Figure 5.

The forces that generate the moment of the hammer claw relative to the point

O1 are mainly centrifugal force

F2, gravity

mg, and cutting resistance

F1, and the corresponding force arms are

L,

L1 sin

θ, and

L2. Neglecting the curvature of the hammer claw, the analysis can be obtained:

In the formula:

L3—Hammer jaw length;

M1—Cutting resistance torque;

M2—Gravitational moment;

M3—Centrifugal torque;

ω—Knife roller rotation angular speed;

R1—Radius of rotation of the center of mass of the hammer claw.

From the similarity of triangles:

The moment balance equation of the hammer claw with respect to the pin center

O1 point is:

Well-organized:

In the formula:

g—gravitational acceleration.

The mass of the hammer claw is m = 1.2 kg; the total length L = 200 mm; the effective working section length L1 = 150 mm; and the fixed section length L2 = 50 mm. The power transmission path of the equipment is divided into two routes: one is the power take-off shaft → gearbox (transmission ratio 3.2:1) → belt drive → knife roller, which provides power for the crushing operation; the other is the hydraulic system → chain drive (transmission ratio 2:1) → pickup roller, which drives the pickup device to operate.

When the hammer claw works, if the deflection angle θ is too large, it will reduce the crushing quality. According to Equation (12) can be known:

Increasing the mass m of the hammer claw reduces the deflection angle θ, which is beneficial for branch crushing. However, a heavier hammer claw also leads to higher fuel consumption per unit time. Therefore, it is necessary to select an appropriate width and thickness to optimize the mass. Based on existing branch crusher designs, the average thickness of the hammer claw in this study is set to 11 mm.

When the L1/L3 ratio increases, the deflection angle θ will become smaller. This shows that the closer the center of mass of the hammer claw is to the cutter end, the smaller the working deflection angle of the hammer claw is, so the hammer claw can be designed as a structure with a small pin end and a large cutter end. Considering the structural strength requirements of the hammer claw, the width of the pin end is 50 mm and the width of the cutter end is 145 mm.

By increasing the angular speed ω of the knife roller, the working deflection angle θ decreases, but the fuel consumption per unit time increases accordingly, and at the same time, the requirements for dynamic balance are high.

2.6. Determination of Hammer Claw Speed

The rotary radius of the hammer claw and the rotational speed of the pulverizing knife roller are important structural and motion parameters of the pulverizer, which have an important influence on the pulverizing effect and the smoothness of operation of the pulverizer [

16,

17]. In order to meet the requirements of unsupported cutting, the hammer claw line cutting speed

v1 ≥ 48 m/s. The design of this machine hammer claw rotary radius

R is 280 mm, the hammer claw rotary radius and the knife roller rotational speed relationship equation is:

In the formula:

v1—Hammer Jaw Wire Cutting Speed, m/s;

n—Hammer claw speed, r/min;

R—Turning radius of the hammer claw, mm.

The calculated speed of the knife roller is 1638 r/min. Considering the toughness of the branch and related factors, the preliminary speed of the knife roller is 1640–2500 r/min.

2.7. Drive Train Design

The transmission system of the grapevine branch crushing and collecting machine is responsible for transferring power from the tractor to the pickup roller, the crushing knife roller, and the hydraulic lifting cylinder beneath the collection box. To enable independent speed adjustment of the pickup and crushing systems while ensuring efficient utilization of tractor power, the transmission is divided into mechanical and hydraulic subsystems. The mechanical transmission comprises the drive from the tractor’s power take-off (PTO) shaft to the crushing knife roller, as well as the transmission of power from the hydraulic motor to the pickup roller. The hydraulic transmission includes a dual-circuit system: one delivering power from the tractor’s hydraulic pump to the lifting cylinder, and another supplying the hydraulic motor. The overall transmission system is illustrated in

Figure 6.

Output Shaft—Crushing Knife Roller Transmission System: The design of this system aims to achieve speed increase while ensuring smooth power transmission. A belt drive is employed in the high-speed stage. During operation, the rotational speed from the tractor’s power take-off (PTO) shaft is first increased and redirected through a gearbox to the large pulley, and then further accelerated via belt drive to the crushing knife roller. Hydraulic Motor—Pickup Roller Transmission System: This system drives the counter-rotating pickup device. The upper and lower pickup rollers are identical in size and rotate in opposite directions at the same speed. Power is transmitted from the tractor’s hydraulic pump to the pickup device through a combination of hydraulic drive and chain transmission.

4. Discussion

This study employed analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the significance of each parameter’s effect on grinding efficiency. Tukey’s HSD test was used for post-hoc multiple comparisons to determine differences between different parameter levels. Design Expert software was used to fit the data and analyze the ANOVA for the grapevine branch pickup rate

Y1 in

Table 4, and the results of the analysis are shown in

Table 5. The results of the ANOVA of the pickup rate

Y1 showed that the regression model

F value of 76.79,

p < 0.0001, indicating that the regression model is extremely significant and statistically significant [

21]. The loss of fit term (Lack of Fit)

p = 0.3049 > 0.05, not significant, indicating that the loss of fit factor does not exist, and the regression equation can be used to replace the real test points in order to correlate the experimental results. The

p-value of pickup roller speed

X2 and ground clearance

X3 in

Table 5 is less than 0.0001, and the factors

X2 and

X3 have a highly significant effect on the pickup rate, and the

p-value of crushing knife roller speed

X1 is 0.4907 (

p > 0.05), indicating that the factor

X1 does not have a significant effect on the pickup rate. Through the comparison of F-value in the table, the degree of influence of each factor on the pickup rate is in the following order: ground clearance

X3 > pickup roller speed

X2 > crushing knife roller speed

X1, the F-value of factors

X3 and

X2 is 339.10 and 191.99, respectively, which shows that ground clearance and pickup roller speed are the key factors affecting the qualified rate of branch crushing.

A quadratic multiple regression was fitted to the data in

Table 5, and the quadratic term (Quadratic) model was chosen to model the regression of branch pickup rate with the factors, and the regression equation was:

Design expert software was used to fit the data and analyze the ANOVA of the grapevine branch crushing length qualification rate

Y2 in

Table 5, and the analysis results are shown in

Table 6. Crush length qualified rate

Y2 ANOVA results show that the regression model

F value of 247.17,

p < 0.0001, indicating that the regression model is extremely significant and statistically significant, the loss of fit term

p value of 0.4014 (

p > 0.05), the loss of fit term is not significant, indicating that the loss of fit factor does not exist, you can use the regression equation to replace the real test points, in order to correlate the results of the experiment. The

p-value of the crushing knife roller speed

X1 and pickup roller speed

X2 in

Table 6 is less than 0.0001, indicating that the factors

X1 and

X2 have a highly significant effect on the crushing pass rate, and the

p-value of the ground clearance

X3 is 0.0105 (

p < 0.05), indicating that the factor

X3 has a significant effect on the crushing pass rate. The size of the F-value in

Table 6 indicates the degree of influence of each factor on the crushing length qualification rate, the larger the F-value, the higher the degree of influence, it can be seen that the degree of influence of the size of the order of: crushing knife roller speed

X1 > pickup roller speed

X2 > clearance

X3, of which the crushing knife roller speed

X1 factor F-value of 1665.02, much larger than the factor

X2 and

X3 F-value, it can be seen that the crushing knife roller speed is a key factor in affecting the branch crushing The

F value of the factor

X1 is 1665.02, which is much larger than the

F value of the factors

X2 and

X3.

Quadratic multiple regression was fitted to the data in

Table 6, and the quadratic term model was chosen to establish the regression model for the crushing length qualification rate and the factors, and the regression equation was:

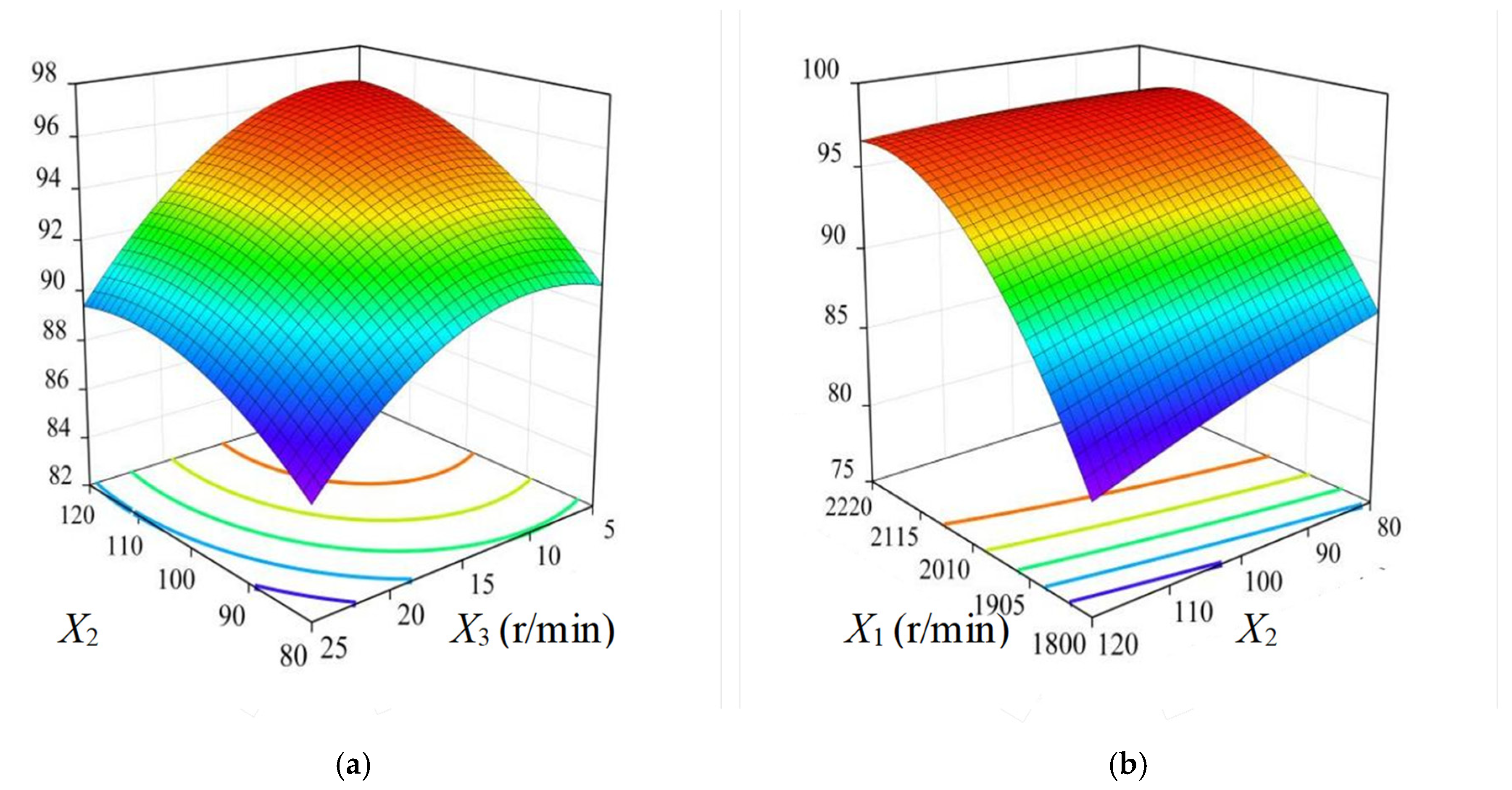

Through the variance table generated by Design Expert, the significant interaction terms of the three factors of crushing knife roller speed X1, pickup roller speed X2, and ground clearance X3 on the pickup rate Y1 and crushing length qualification rate Y2 were screened out, and the interaction effects were further analyzed through the corresponding 3D response surface plots.

In

Table 6 the

p-value of the interaction term

X2X3 was 0.0275 (

p < 0.05), which had a significant effect on the pickup rate

Y1, while the

p-values of the remaining two terms

X1X2 and

X1X3 were 0.2160 and 0.2713 respectively, which were all greater than 0.05 and did not have a significant effect.

C.V.% < 10% indicates high reliability and precision of the experiment; Adeq Precision represents the ratio of effective signal to noise, with values greater than 4 considered reasonable. As shown in

Table 7, the fitted regression equation complies with the above validation criteria and demonstrates good adaptability.

As shown in

Figure 9a, the branch pickup rate increases with the rising speed of the pickup roller. However, once the pickup rate reaches a certain level, the influence of further increases in roller speed diminishes. In contrast, the pickup rate exhibits an overall declining trend as the ground clearance of the pickup teeth increases. When the clearance remains within a small range, the pickup rate fluctuates only slightly, whereas a very low clearance has a more pronounced negative effect.

The analysis suggests that increasing the pickup roller speed leads to greater overlap of the tool trajectories, reducing the area of missed branches. Nevertheless, when the roller speed exceeds a certain threshold and the pickup teeth clearance is low, most of the uncollected branches tend to be shorter ones scattered on the surface [

22]. Whether these small branches can be collected becomes less dependent on roller speed. On the other hand, a larger ground clearance prevents the pickup teeth from effectively gathering branches lying close to the ground, causing some to be pushed aside rather than collected, thereby reducing the overall pickup rate.

From

Table 6, it can be seen that the

p value of the interaction term

X1X2 is 0.0006 (

p < 0.01), which has a highly significant effect on the crushing length qualification rate

Y2, and the

p values of the remaining two terms

X1X3 and

X2X3 are 0.0972 and 0.7149 respectively, which are all greater than 0.05 and do not have a significant effect.

As shown in

Figure 9b, the qualified rate of branch crushing length increases with the rising speed of the crushing knife roller. However, once the roller speed exceeds a certain value, the growth rate of the qualification rate slows significantly and begins to fluctuate within a narrow range. Similarly, an increase in the pickup roller speed also contributes to a higher qualification rate initially, though further speed improvements yield diminishing returns.

The analysis indicates that a higher crushing knife roller speed increases the frequency of blade impacts per unit time, thereby improving the proportion of branches that meet the desired length standard. Nevertheless, beyond a certain point, larger-diameter and harder branches resist further fragmentation. Additionally, the high-speed rotation of the hammer-claw tools drastically accelerates the airflow within the crushing chamber, causing some unqualified fragments to be ejected prematurely before achieving full comminution.

Regarding the effect of pickup roller speed, an elevated speed raises the instantaneous feed rate of branches. Excessive feeding can overwhelm the crushing capacity, resulting in insufficiently processed branches and ultimately reducing the qualification rate.

In order to find the best combination of working parameters and structural parameters of the grapevine branch crushing and collecting machine, the multi-objective optimization algorithm of the Design Expert software is used to optimize the parameters of the regression model, and according to the range of values of the factors in the test program, while the pick-up rate

Y1 and the crushing length qualification rate

Y2 are taken to be the maximum value, the objective function and constraints are as follows:

Through the Design Expert software to find the optimal combination of factors: crushing knife roller speed X1 take the value of 2184.00 r/min, pickup roller speed X2 take the value of 106.78 r/min, the ground clearance X3 take the value of 9.72 mm, at this time, pick up the rate of Y1 for 96.21%, crushing the length of the qualified rate of Y2 for 97.06%. Taking into account the machine in the actual operation of the factors can achieve the accuracy of the value, adjusted and software analysis of the value of the optimal combination of parameters approximate: crushing knife roller speed 2185 r/min, pickup roller speed 105 r/min, ground clearance 10 mm.

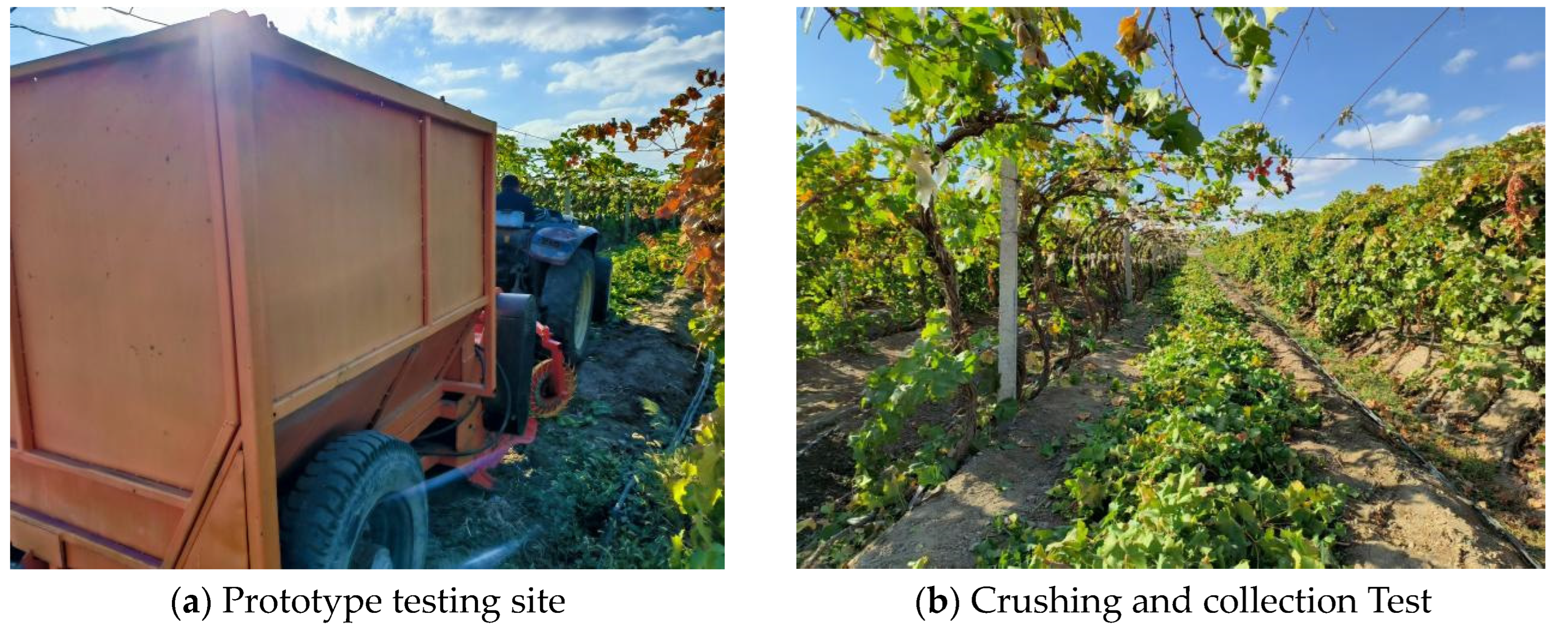

In order to verify the reliability of the optimal parameter combinations found in the response surface test, a validation test was carried out in the field to adjust the factors to the optimal combinations, and in order to eliminate the experimental errors, the validation test was repeated five times to take the average value, and the results of the optimal combinations validation test are shown in

Table 8.

As can be seen from

Table 8, the field optimal combination of validation test results show that the prototype pick-up rate of 95.93% ± 1.2%, crushing length qualification rate of 97.19% ± 0.8%, the difference between the field test value and the theoretical value obtained from the response surface test were: 0.28%, 0.13%, which can be seen that the experimental value and the theoretical value of the basic similar to show that the regression model has a very good reliability, and the prototype machine can meet the design requirements. The test results are shown in

Figure 10.

Based on the measured data from the Power Take-Off (PTO) power tester, this study conducted a comparative analysis of the energy consumption differences between the optimal operating condition and non-optimal operating conditions. Under the optimal operating condition, the PTO power consumption is 36.8 kW, and the fuel consumption per hectare of operation is 18.5 L, which are 12.3% and 10.8% lower than those under non-optimal operating conditions, respectively. Combined with the market price of mechanical operation in vineyards in Xinjiang, China (the operation cost per hectare is 800 yuan), the calculation shows that the optimal operating condition can save approximately 86 yuan in operation cost per hectare, while the operation efficiency is increased by 15% [

23]. This fully demonstrates the economy and efficiency of this optimized parameter combination in practical applications.

The grapevine branch shredder and collector developed in this paper can serve as a reference for designing similar orchard branch shredding and collection equipment [

24]. Research depth on the machine’s key components still needs to be enhanced, and there is room for optimizing the overall structure. Future research and improvements can be advanced through three approaches: First, further analyze how parameters such as branch diameter, blade bending angle, and blade center of gravity affect cutting resistance during branch shredding [

25]. Investigate the influence of shredding device structural parameters on internal airflow characteristics, and conduct coupled gas-solid flow field simulations to support device optimization. Second, given the multiple factors influencing the performance of the grapevine branch shredder and collector, supplementary experiments should analyze the specific effects of other structural parameters—such as the center distance of the pick-up rollers, the number of blades, and their arrangement—on the overall machine performance. Third, while ensuring the machine meets operational performance standards, lightweight structural improvements should be pursued to achieve the goals of reducing manufacturing costs and lowering operational energy consumption.