Design and Testing of a Helmholtz Coil Device to Generate Homogeneous Magnetic Field for Enhancing Solid-State Fermentation of Agricultural Biomass

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Helmholtz Coil System Design and Validation

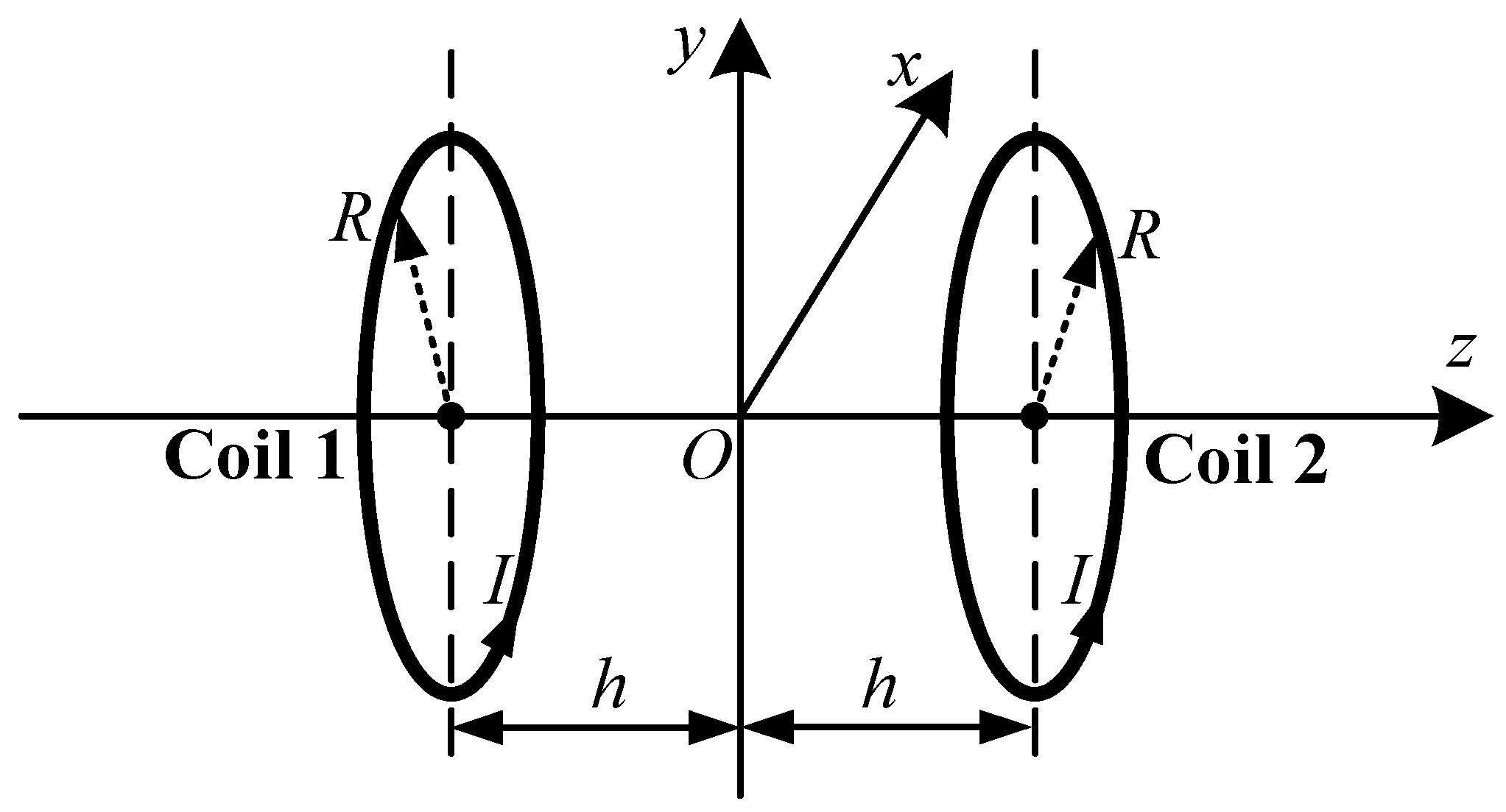

2.1. Basic Principle of Helmholtz Coil

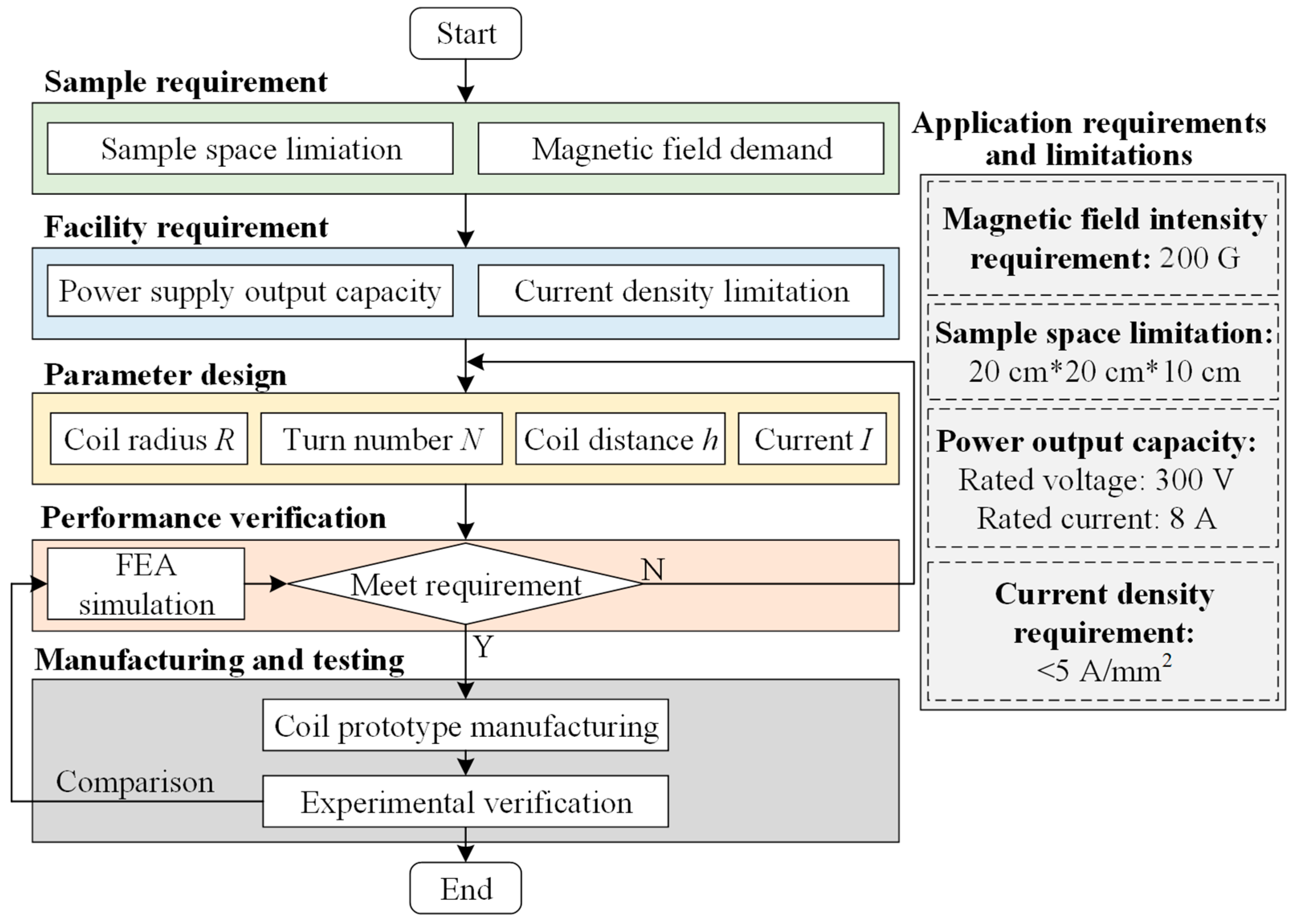

2.2. Helmholtz Coil Design Steps

- (1)

- Design requirement

- (2)

- Coil parameter calculation

- (3)

- Magnetic field homogeneity analysis

- (4)

- FEA Simulation

- (5)

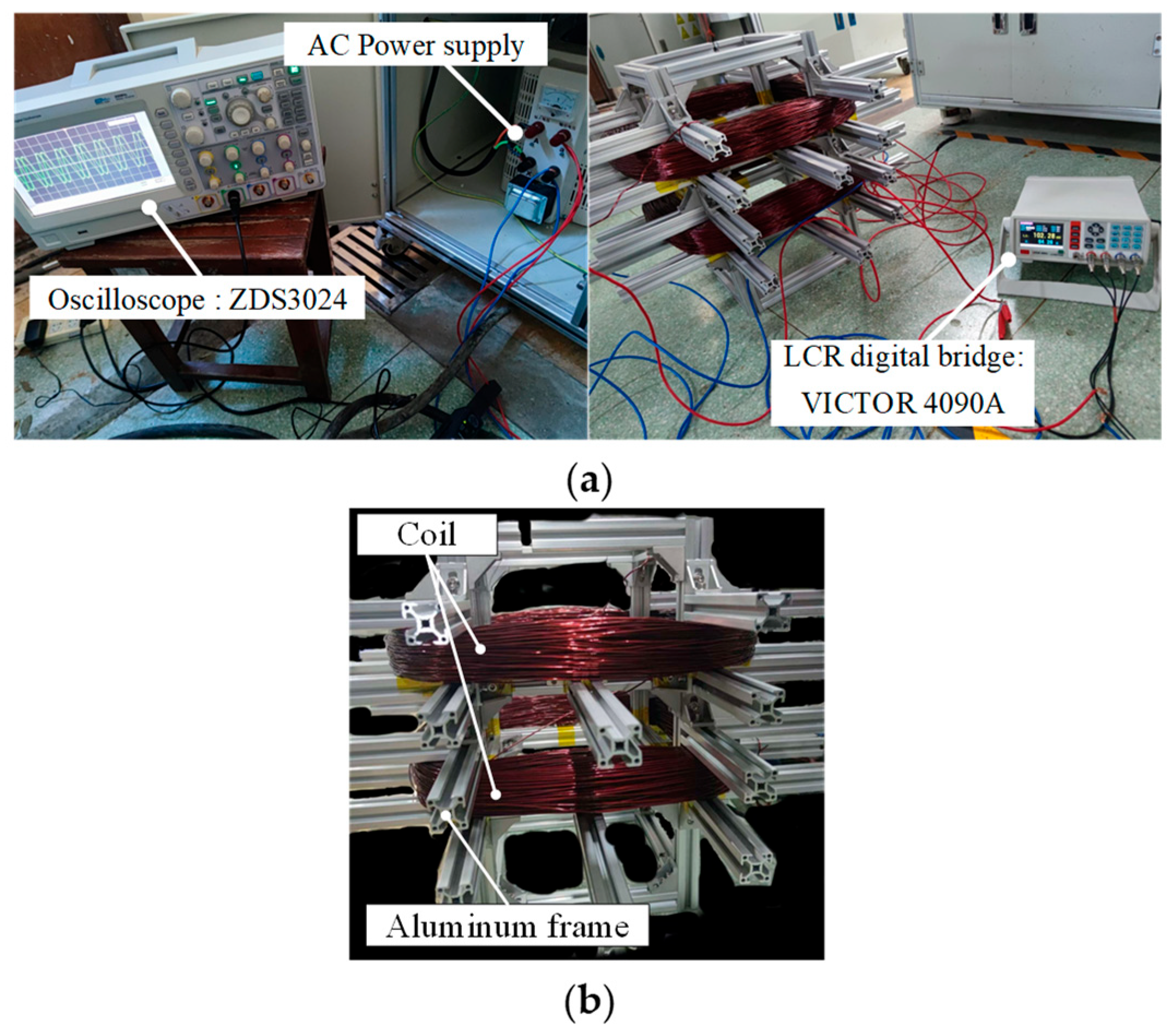

- Prototype Manufacturing and Testing

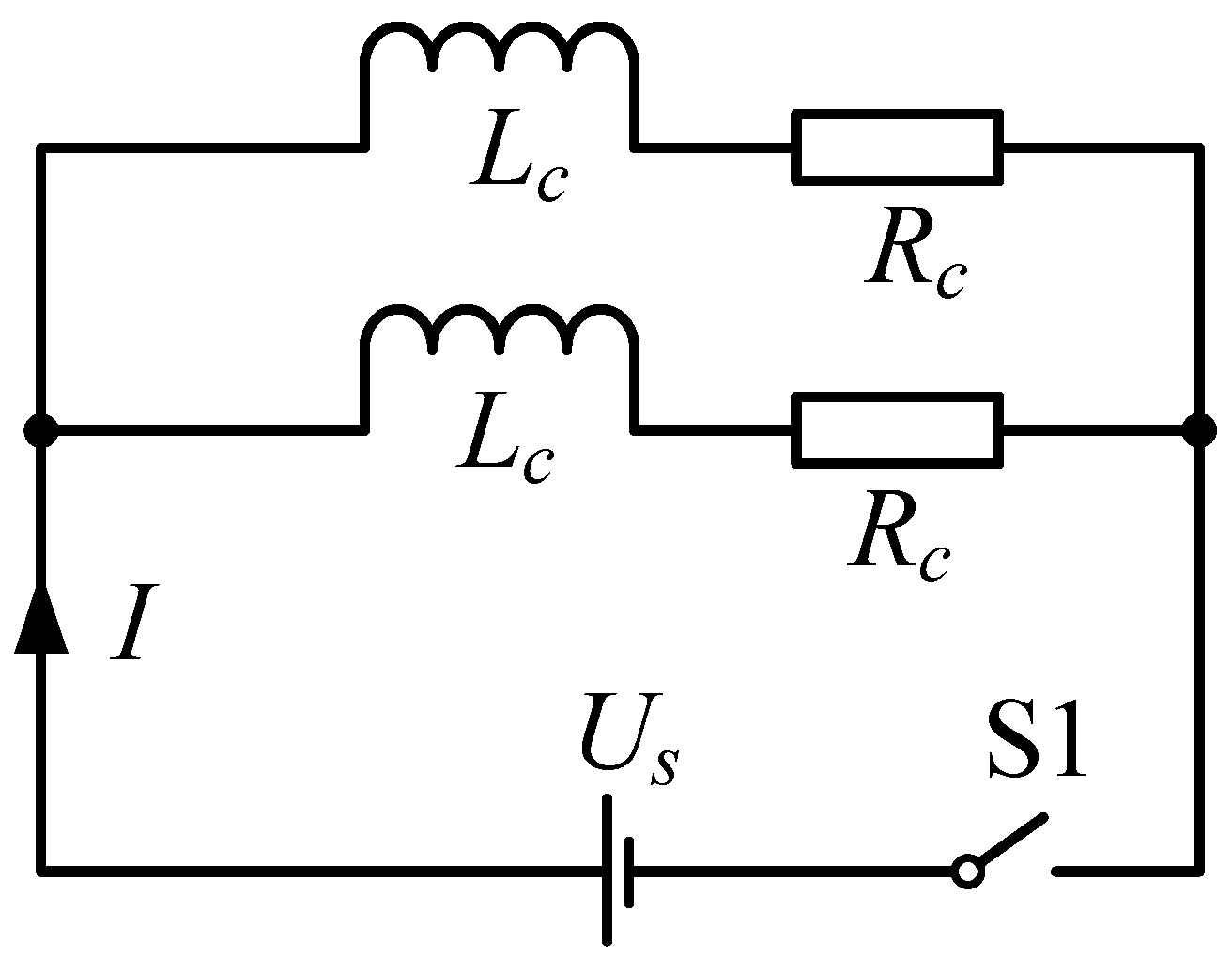

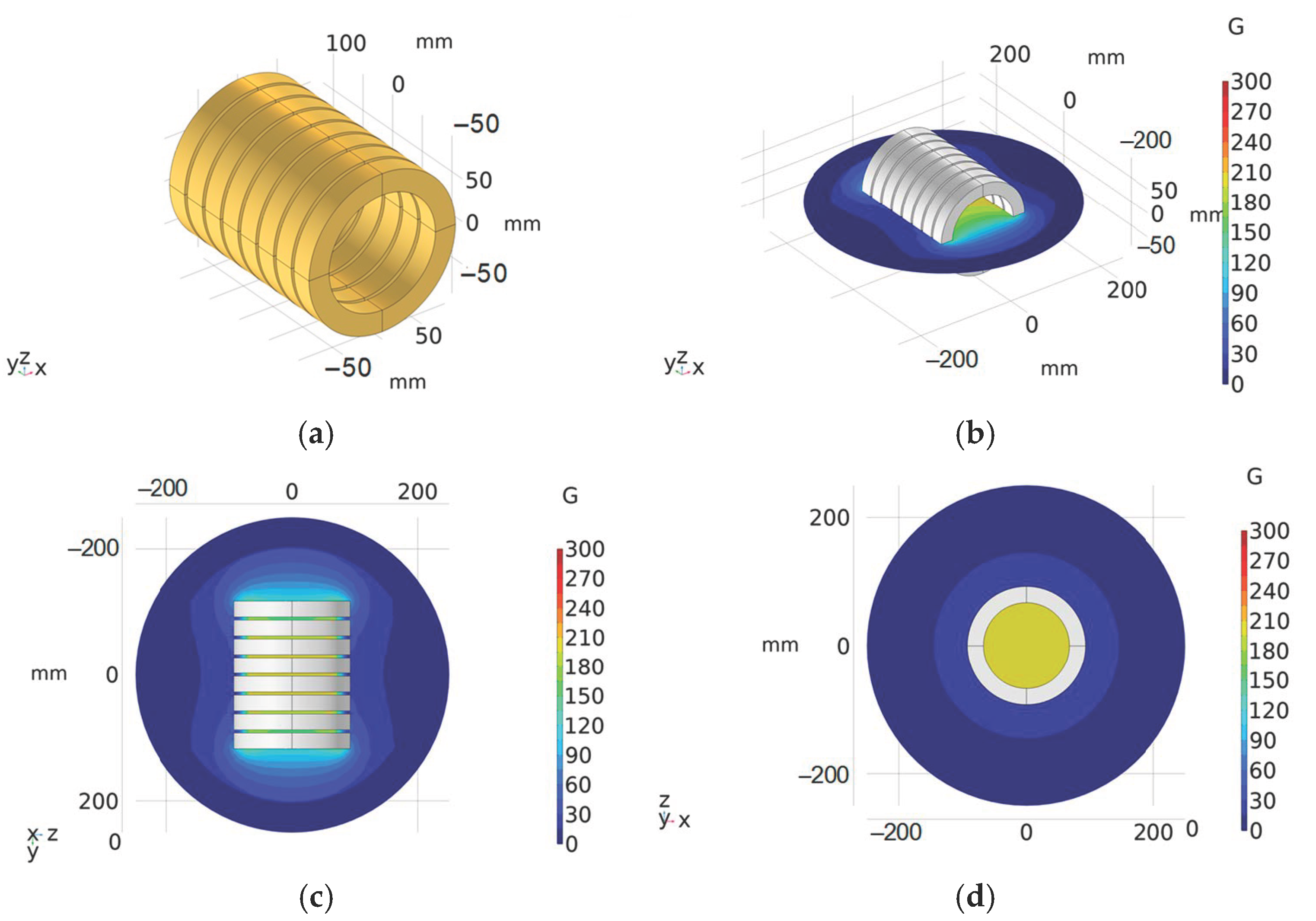

3. Analysis and Optimization of Electromagnetic Field Performance

3.1. Ring Coil Structure

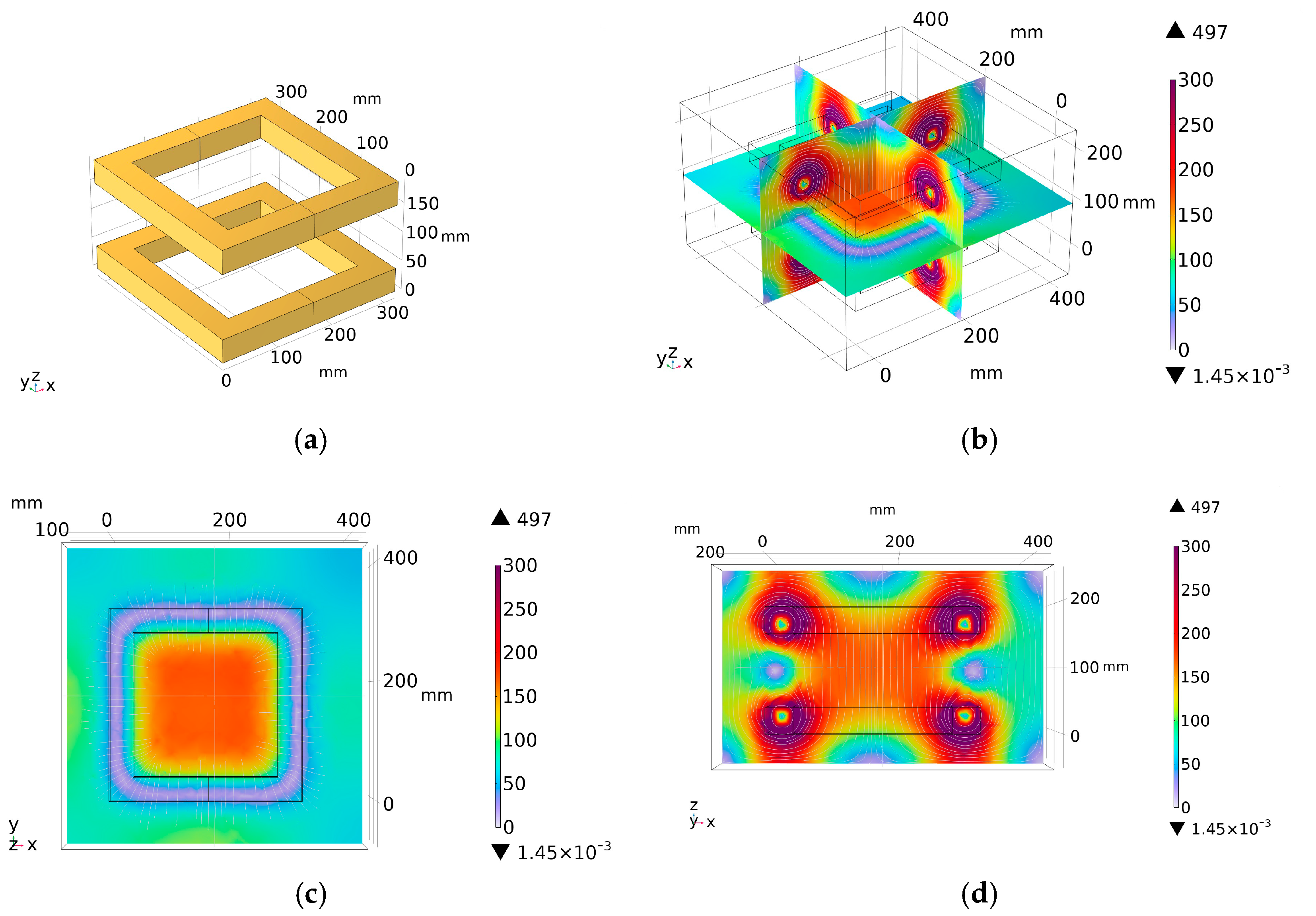

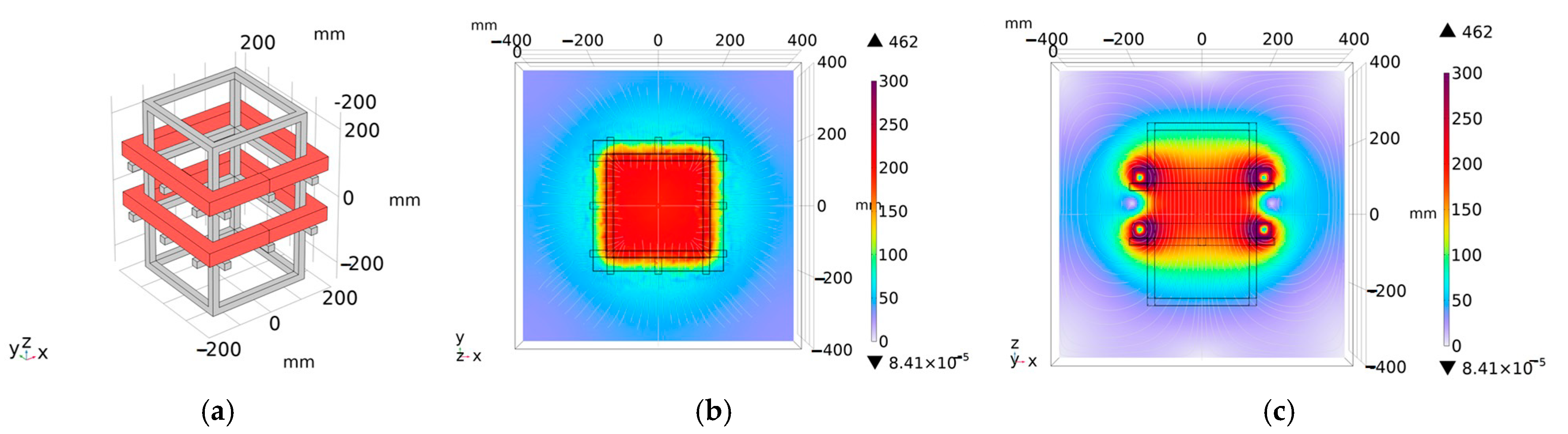

3.2. Double-Square Coil Structure

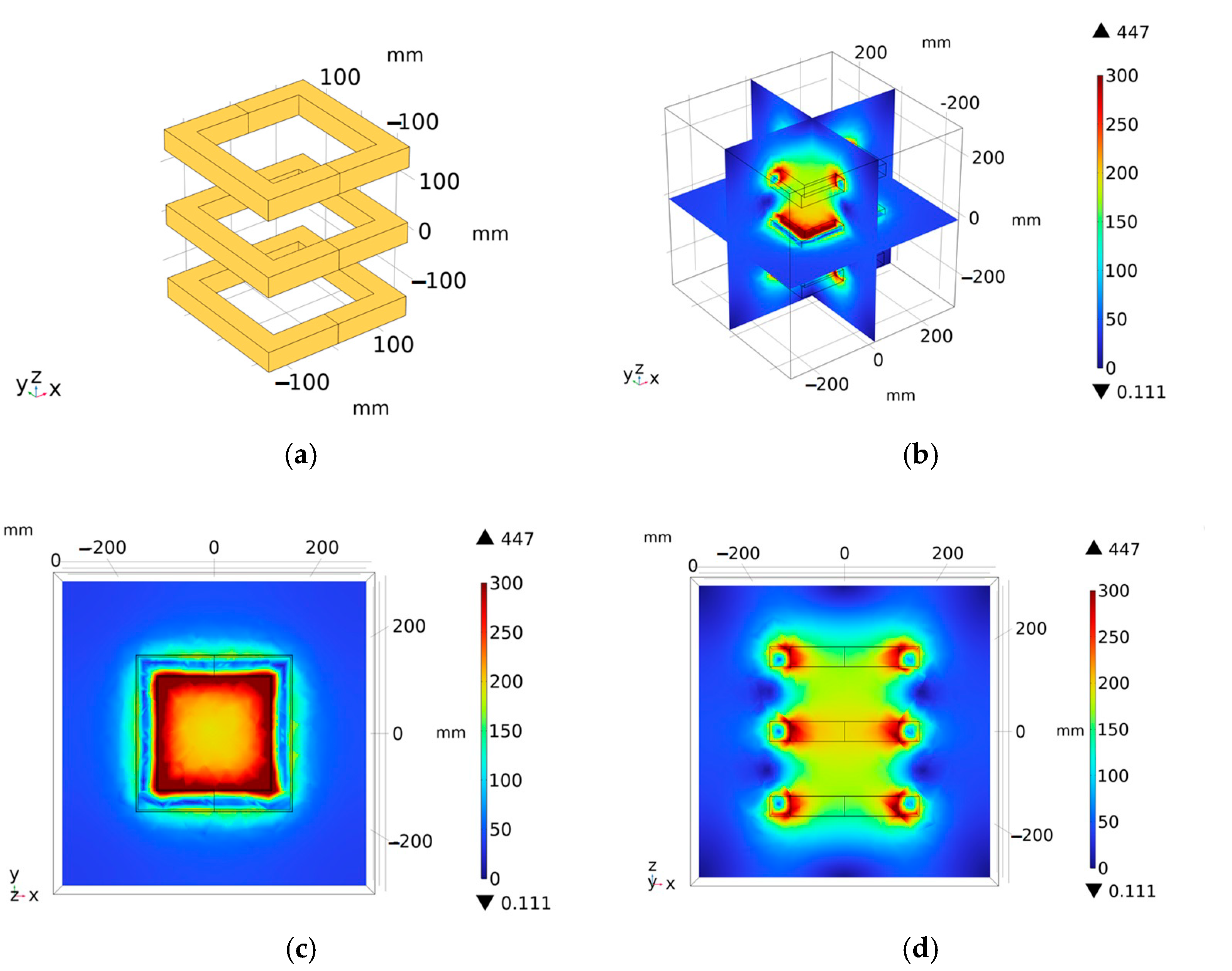

3.3. Triangular Coil Structure

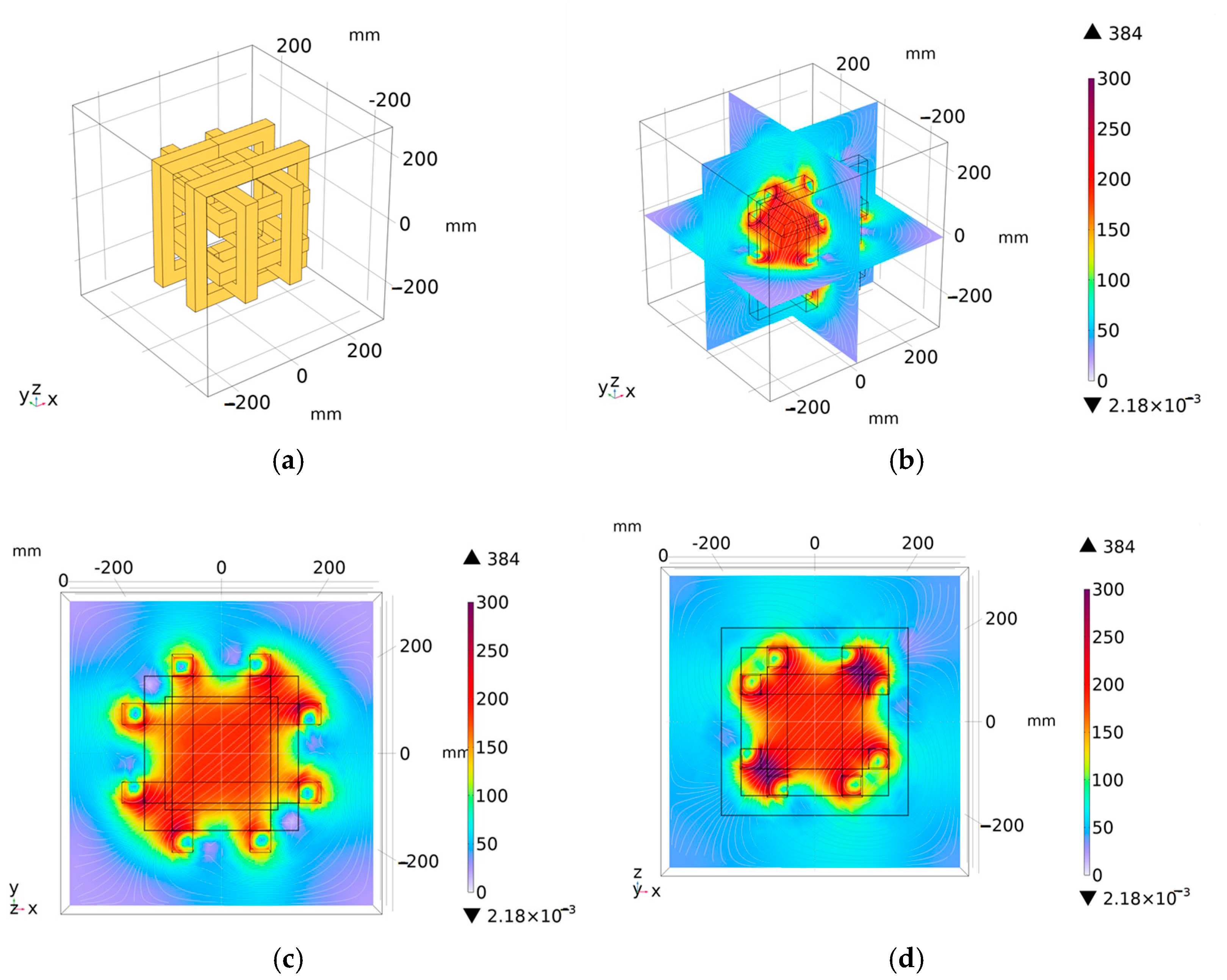

3.4. Hexagonal Three-Dimensional Coil Structure

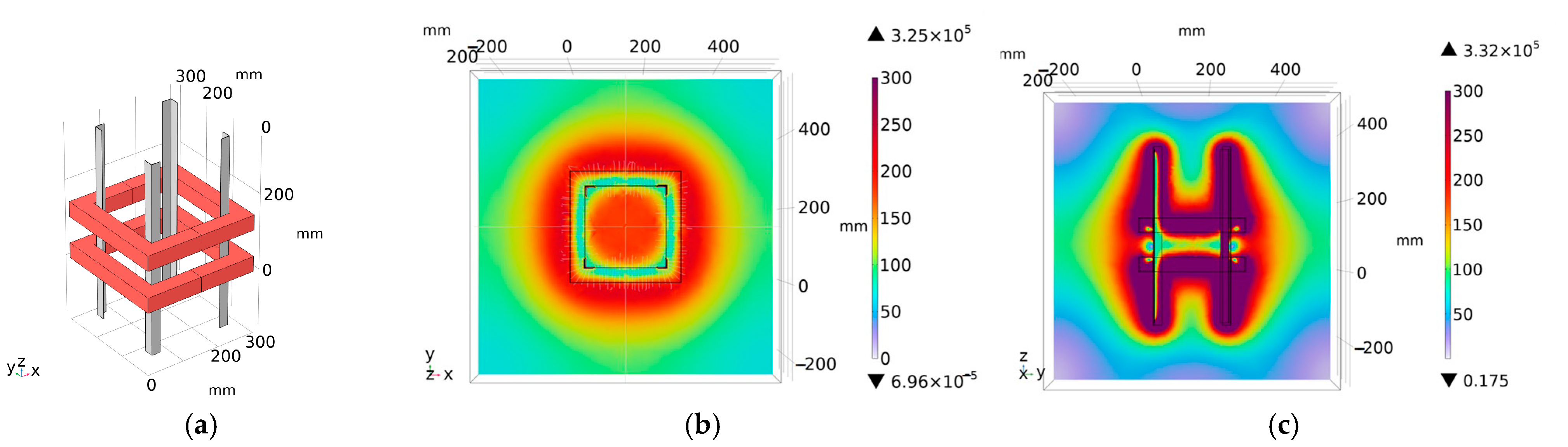

3.5. Coil Structure Selection

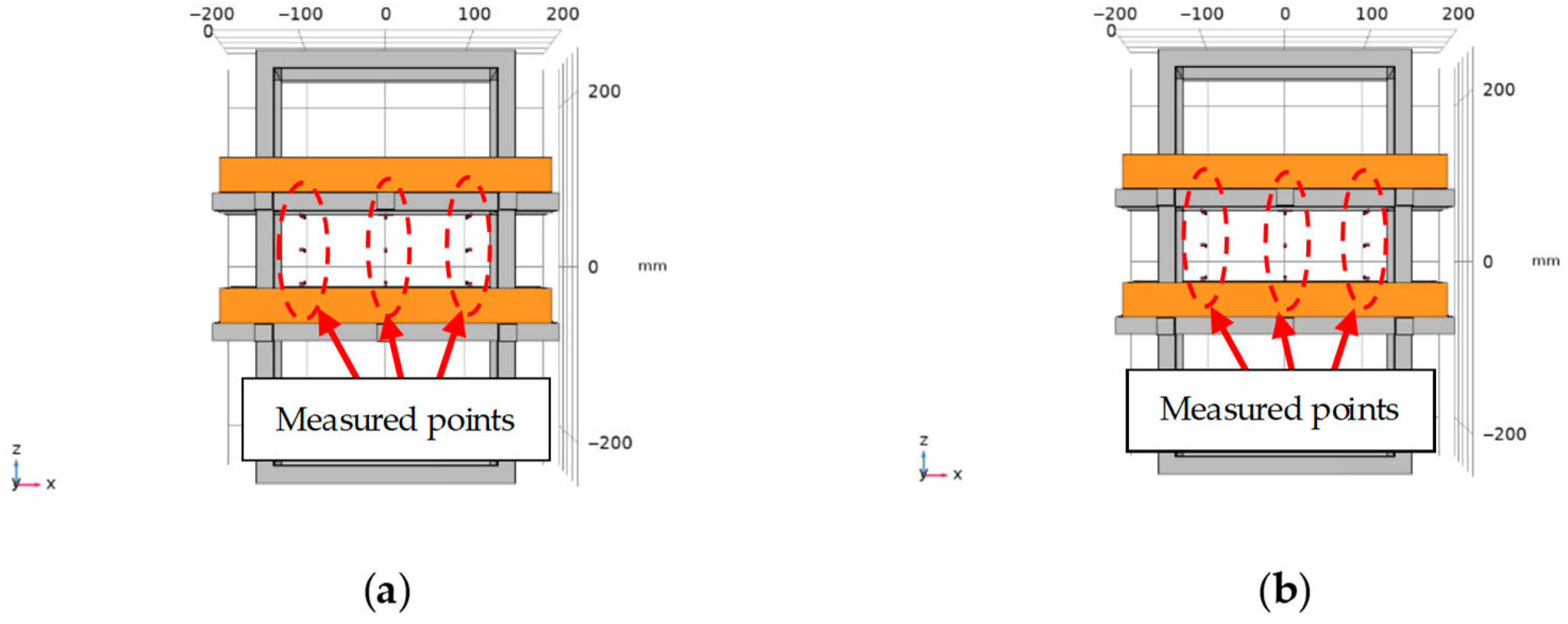

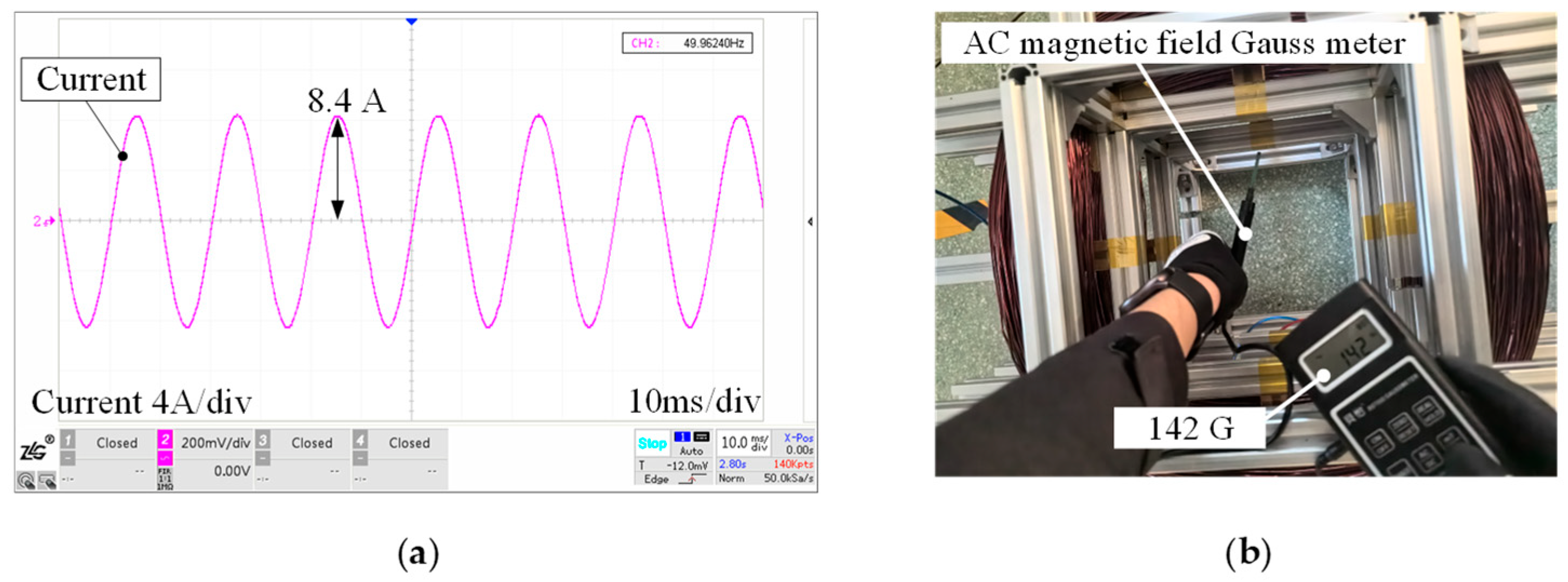

4. Experiment Verification of Magnetic Field Intensity Homogeneity

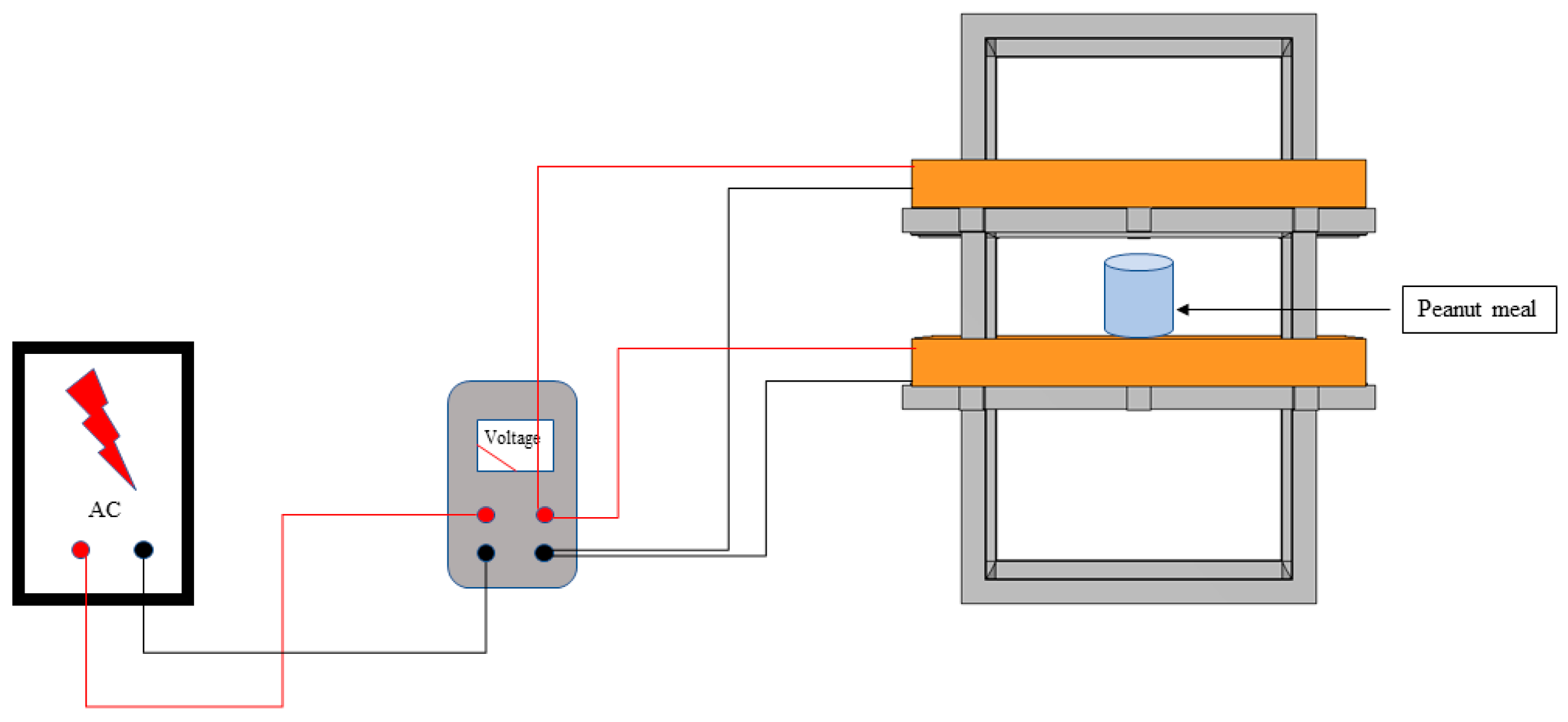

5. Magnetic-Field-Assisted Fermentation for Enhanced Polypeptide Production from Peanut Meal

5.1. Bacteria and Growth Conditions

5.2. Magnetic-Field-Assisted Fermentation Experimental Steps

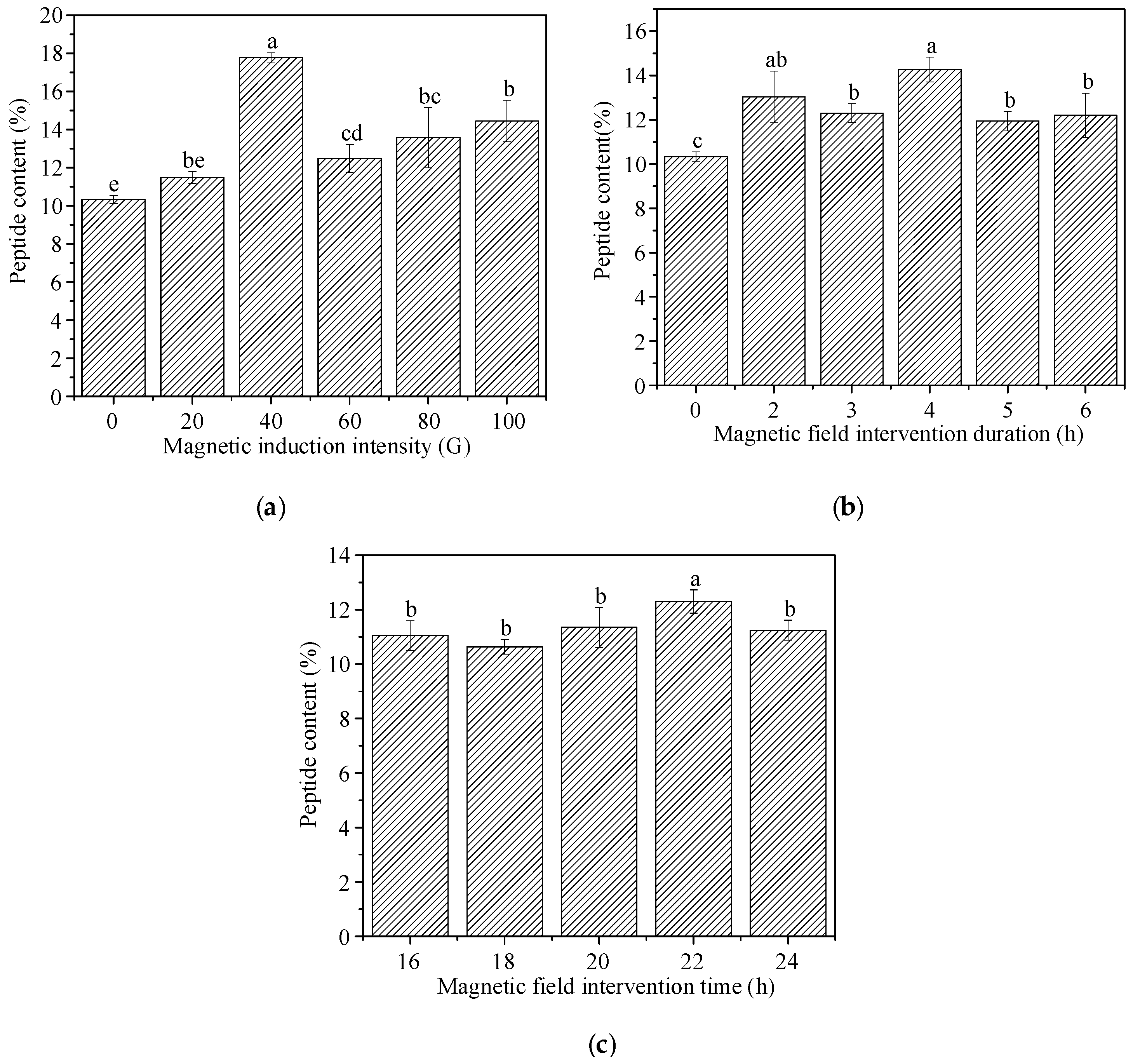

5.3. Experimental Study on the Effect of Magnetic Field on the Preparation of Peptides from Peanut Meal by Solid-State Fermentation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chilakamarry, C.R.; Sakinah, A.M.M.; Zularisam, A.W.; Sirohi, R.; Khilji, I.A.; Ahmad, N.; Pandey, A. Advances in solid-state fermentation for bioconversion of agricultural wastes to value-added products: Opportunities and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreti, N.; Kumar, P.; Kataria, R. Sustainable biotransformation of lignocellulosic biomass to microbial enzymes: An overview and update. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222 Pt 1, 119432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Lv, G.; Fang, X.; Teng, T.; Shi, B. Enhancing small peptide content and improving the microbial community and metabolites in corn gluten meal with solid-state fermentation using keratinase-producing Bacillus strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 441, 111320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Lu, D.; Wu, L.; Qin, C.; Wang, H.; Deng, J.; Luo, X. Highly efficient and sustainable bioconversion of cottonseed meal to high-value products through solid-state fermentation by protease-enhanced Streptomyces sp. SCUT-3. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jin, Y.; Yang, N.; Wei, L.; Xu, D.; Xu, X. Improving microbial production of value-added products through the intervention of magnetic fields. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 393, 130087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Song, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Lei, A.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, L.; He, Q. Study on the selective regulation of microbial community structure in microbial fuel cells by magnetic field–coupled magnetic carbon dots. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 437, 133065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, H.; He, R.; Ren, X.; Zhou, C. Prospects and application of ultrasound and magnetic fields in the fermentation of rare edible fungi. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, H. Effect of low-intensity magnetic field on the growth and metabolite of Grifola frondosa in submerged fermentation and its possible mechanisms. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Guo, Y.; Wu, P.; Liu, S.; Gu, C.; Wu, Y.M.; Ma, H.; He, R. Enhancement of polypeptide yield derived from rapeseed meal with low-intensity alternating magnetic field. Foods 2022, 11, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canli, O.; Kurbanoglu, E.B. Application of low magnetic field on inulinase production by Geotrichum candidum under solid state fermentation using leek as substrate. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2012, 28, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.M.; Cogo, A.J.D.; Perez, V.H.; Santos, N.F.; Okorokova-Façanha, A.L.; Justo, O.R.; Façanha, A.R. Increases of bioethanol productivity by S. cerevisiae in unconventional bioreactor under ELF-magnetic field: New advances in the biophysical mechanism elucidation on yeasts. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Yang, N.; Hou, J.; Lv, X.; Gong, L. Low frequency magnetic field assisted production of acidic protease by Aspergillus niger. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhu, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Betchem, G.; Yolandani, Y.; Ma, H. Enhancing submerged fermentation of Antrodia camphorata by low-frequency alternating magnetic field. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 86, 103382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hou, J.; Wang, D.; Shi, H.; Gong, L.; Lv, X.; Liu, J. Effect of low frequency alternating magnetic field for erythritol production in Yarrowia lipolytica. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuly, J.A.; Ma, H.; Zabed, H.M.; Dong, Y.; Chen, G.; Guo, L.; Betchem, G.; Igbokwe, C.J. Exploring magnetic field treatment into solid-state fermentation of organic waste for improving structural and physiological properties of keratin peptides. Food Biosci. 2022, 49, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarca, G.; Denizkara, A.J. Changes of quality in yoghurt produced under magnetic field effect during fermentation and storage processes. Int. Dairy J. 2024, 150, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Ding, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, G. Mechanism of static magnetic field influencing morphogenesis of Flavobacterium sp. m1-14. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2025, 191, 110714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; Gao, M. Effect of a magnetic field on the production of Monascus pigments and citrinin via regulation of intracellular and extracellular iron content. Food Phys. 2026, 3, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Cui, Y.; Liang, H.; Li, Z. Critical review on magnetic biological effects of microorganisms in the field of wastewater treatment: Theory and application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Armenteros, T.M.; Villacís-Chiriboga, J.; Guerra, L.S.; Ruales, J. Electromagnetic fields effects on microbial growth in cocoa fermentation: A controlled experimental approach using established growth models. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velichkova, P.G.; Ivanov, T.V.; Lalov, I.G. Magnetically assisted fluidized bed bioreactor for bioethanol production. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2017, 49, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Konopacka, A.; Rakoczy, R.; Konopacki, M. The effect of rotating magnetic field on bioethanol production by yeast strain modified by ferrimagnetic nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 473, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, X.; He, R.; Cui, H. Action mechanism of pulsed magnetic field against E. coli O157:H7 and its application in vegetable juice. Food Control 2019, 95, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betchem, G.; Dabbour, M.; Tuly, J.A.; Lu, F.; Liu, D.; Monto, A.R.; Dusabe, K.D.; Ma, H. Effect of magnetic field-assisted fermentation on the in vitro protein digestibility and molecular structure of rapeseed meal. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 3883–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Xu, B.; Qu, G.; Ning, P.; Ren, N.; Zou, H. Research on the mechanism of copper removal during electromagnetic enhanced aerobic fermentation of sludge. Renew. Energy 2024, 231, 121014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Pan, Z.; Gao, M.; Luo, L. Efficacy in microbial sterilization of pulsed magnetic field treatment. Int. J. Food Eng. 2008, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawin, S.M.; Adey, W.R.; Sabbot, I.M. Ionic factors in release of 45Ca2+ from chicken cerebral tissue by electromagnetic fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 6314–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, C.F.; Benane, S.G.; Elliott, D.J.; House, D.E.; Pollock, M.M. Influence from brain tissue in Vitro: A three-model analysis consistent with the frequency response up to 510 Hz. Bioelectromangetics 1988, 9, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byus, C.V.; Lundak, R.L.; Fletche, R.M.; Adey, W.R. Alterations in protein kinase activity following exposure of cultured human lymphocytes to modulated microwave fields. Bioelectromagnetics 1984, 5, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Qu, J.; Peng, Y. Sterilization of Escherichia coli cells by the application of pulsed magnetic field. J. Environ. Sci. 2004, 16, 348–352. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinder, M.A.; Wang, K.; Zheng, B.; Shrestha, M.; Fan, Q. Magnetic field enhanced cold plasma sterilization. Clin. Plasma Med. 2020, 17, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Gu, T.; Gao, M. A low-frequency magnetic field regulated the synthesis of carotenoids in Rhodotorula mucilaginosa by influencing iron metabolism. Food Phys. 2025, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, A.F.; Franco, E.; Cadavid, H.; Pinedo, C.R. Analysis of the magnetic field homogeneity for an equilateral triangular helmholtz coil. Prog. Electromagn. Res. M 2016, 50, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, A.F.; Franco, E.; Cadavid, H.; Pinedo, C.R. A comparative study of the magnetic field homogeneity for circular, square and equilateral triangular helmholtz coils. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer, and Optimization Techniques (ICEECCOT), Mysuru, India, 15–16 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, A.F.; Franco, E.; Pinedo, C.R. Study and analysis of magnetic field homogeneity of square and circular Helmholtz coil pairs: A Taylor series approximation. In Proceedings of the 2012 VI Andean Region International Conference, Cuenca, Ecuador, 7–9 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baranova, V.E.; Baranov, P.F. The Helmholtz coils simulating and improved in COMSOL. In Proceedings of the 2014 Dynamics of Systems, Mechanisms and Machines (Dynamics), Omsk, Russia, 11–13 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhao, J.; Xiang, Y. The sterilization effect of solenoid magnetic field direction on heterotrophic bacteria in circulating cooling water. Procedia Eng. 2017, 174, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Murayama, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Yoshimura, N.; Iwano, K.; Kudo, K. Evidence for sterilization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae K 7 by an external magnetic flux. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 31, L676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, K.; Nakamura, K.; Okuno, K.; Ano, T.; Shoda, M. Effect of homogeneous and inhomogeneous high magnetic fields on the growth of Escherichia coli. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 1996, 81, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutmeyer, A.; Raman, R.; Murphy, P.; Pandey, S. Effect of magnetic field on the fermentation kinetics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2011, 2, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, K.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, Y. Enhancement of magnetic field on fermentative hydrogen production by Clostridium pasteurianum. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xing, M.; Liu, C.; Ye, J.; Cheng, H.; Miao, Y. Optimization of composite Helmholtz coils towards high magnetic uniformity. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2023, 47, 101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, F.J.; Bayón, A.; Gascón, F. Optimization of the magnetic field homogeneity of circular and conical coil pairs. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2019, 90, 045120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; She, S.; Zhang, S. An improved Helmholtz coil and analysis of its magnetic field homogeneity. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2002, 73, 2175–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, V.D.; Jeng, J.T.; Tsao, T.H.; Pham, T.T.; Mei, P.I. Development of a broad bandwidth Helmholtz coil for biomagnetic application. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2020, 57, 5300305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, S.M.O.A.; Muhanna, K.A.; Khan, M.O. Design and Testing of a Square Helmholtz Coil for NMR Applications with Relative Improved B 1 Homogeneity. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques (IST), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 9–10 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Ma, H.; Wang, H. Inactivation of E. coli by high-intensity pulsed electromagnetic field with a change in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 2014, 28, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, M.; Motta Sobrinho, M.A.; Kraume, M. The use of biomagnetism for biogas production from sugar beet pulp. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 164, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Fang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Ni, W.; Sun, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, G.; et al. Effect of static magnetic field on morphology and growth metabolism of Flavobacterium sp. m1–14. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerana, M.; Yu, N.N.; Bae, S.J.; Kim, I.; Kim, E.S.; Ketya, W.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, N.Y.; Park, G. Enhancement of fungal enzyme production by radio-frequency electromagnetic fields. J. Ferment. 2022, 8, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Coil length, mm | 300 |

| Turn number per coil | 441 |

| Coil distance, mm | 150 |

| Wire type | QZY-2/180 |

| Wire diameter, mm | 2 |

| Wire insulation thickness, mm | 0.05 |

| Current density, A/mm2 | 2.54 |

| Shelf Number | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 145 G | 143 G | 146 G |

| 143 G | 141 G | 144 G | |

| 141 G | 142 G | 147 G | |

| 2 | 143 G | 142 G | 141 G |

| 141 G | 142 G | 143 G | |

| 140 G | 141 G | 141 G | |

| 3 | 145 G | 142 G | 146 G |

| 143 G | 141 G | 144 G | |

| 141 G | 142 G | 145 G |

| Factor | Level |

|---|---|

| Magnetic field intensity (G) | 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 |

| Magnetic field treatment duration (h) | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

| Magnetic field intervention time (fermentation hour) | 0, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24 |

| Sequence | Magnetic Induction Intensity (G) | Magnetic Field Intervention Duration (h) | Magnetic Field Intervention Time (Fermentation Hour) | Peptide Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 G | 4 h | 20 h | 13.5 |

| 2 | 20 G | 3 h | 24 h | 12.3 |

| 3 | 20 G | 5 h | 22 h | 15.0 |

| 4 | 40 G | 4 h | 24 h | 16.5 |

| 5 | 40 G | 3 h | 22 h | 18.4 |

| 6 | 40 G | 5 h | 20 h | 16.0 |

| 7 | 60 G | 4 h | 22 h | 13.3 |

| 8 | 60 G | 3 h | 20 h | 9.8 |

| 9 | 60 G | 5 h | 24 h | 11.6 |

| K1 | 40.8 | 40.5 | 39.3 | / |

| K2 | 50.9 | 43.3 | 46.7 | / |

| K3 | 34.7 | 42.6 | 40.4 | / |

| k1 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 13.1 | / |

| k2 | 16.97 | 14.43 | 15.57 | / |

| k3 | 11.57 | 14.20 | 13.47 | / |

| R | 5.40 | 0.93 | 2.47 | / |

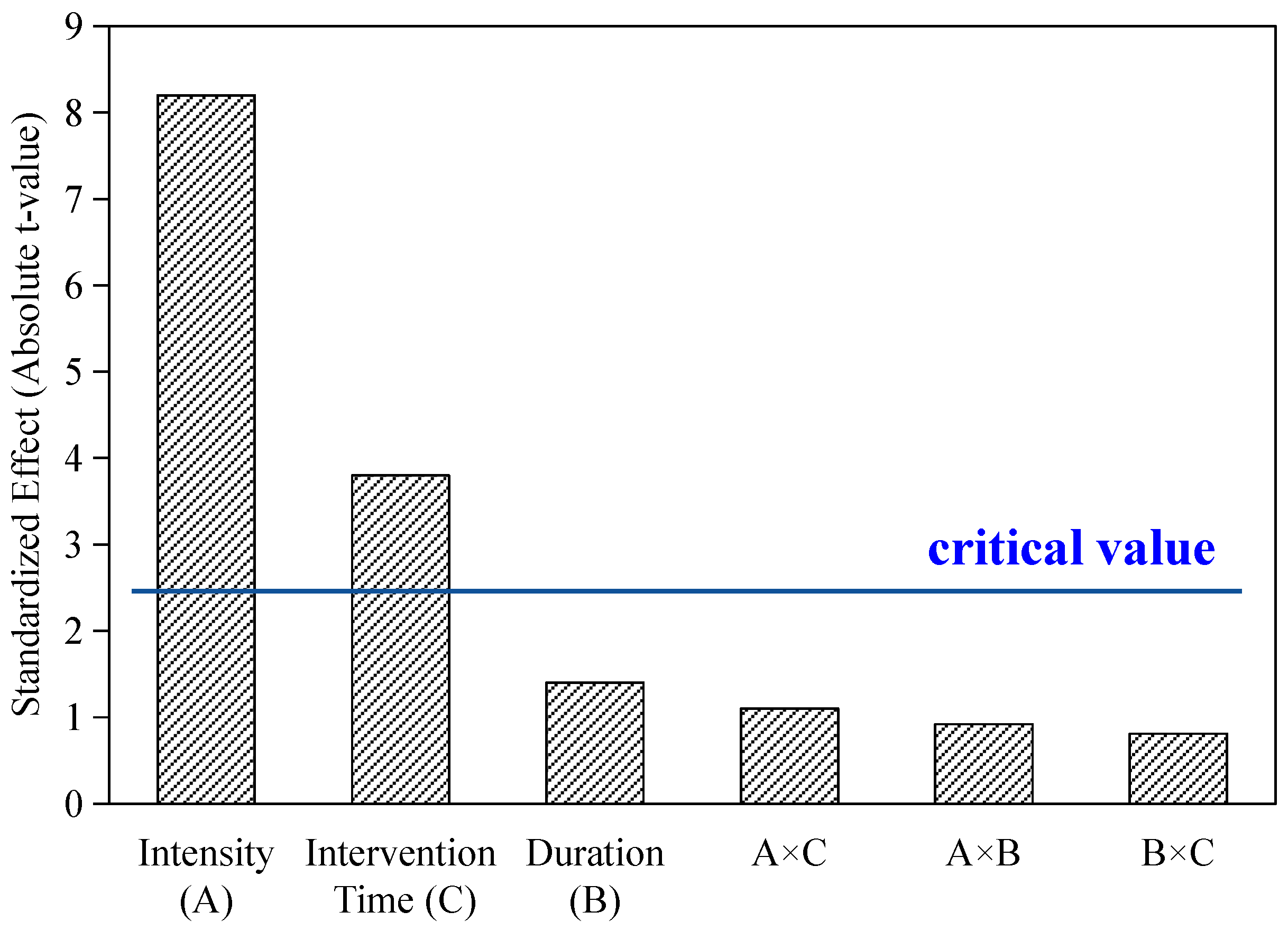

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares (SS) | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Mean Square (MS) | F-Value | F-Critical (α = 0.05) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Intensity) | 44.25 | 2 | 22.125 | 221.25 | 19.00 | ** |

| B (Time) | 1.36 | 2 | 0.68 | 6.8 | 19.00 | ns |

| C (Duration) | 9.29 | 2 | 4.645 | 46.45 | 19.00 | ** |

| Error | 0.20 | 2 | 0.10 | - | - | - |

| Total | 55.00 | 8 | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; Dai, C.; Du, Y.; He, R.; Ma, H. Design and Testing of a Helmholtz Coil Device to Generate Homogeneous Magnetic Field for Enhancing Solid-State Fermentation of Agricultural Biomass. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110385

Chen H, Zhang Y, He Z, Dai C, Du Y, He R, Ma H. Design and Testing of a Helmholtz Coil Device to Generate Homogeneous Magnetic Field for Enhancing Solid-State Fermentation of Agricultural Biomass. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(11):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110385

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Han, Yang Zhang, Zhuofan He, Chunhua Dai, Yansheng Du, Ronghai He, and Haile Ma. 2025. "Design and Testing of a Helmholtz Coil Device to Generate Homogeneous Magnetic Field for Enhancing Solid-State Fermentation of Agricultural Biomass" AgriEngineering 7, no. 11: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110385

APA StyleChen, H., Zhang, Y., He, Z., Dai, C., Du, Y., He, R., & Ma, H. (2025). Design and Testing of a Helmholtz Coil Device to Generate Homogeneous Magnetic Field for Enhancing Solid-State Fermentation of Agricultural Biomass. AgriEngineering, 7(11), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110385