1. Introduction

Brazil, in addition to being one of the largest coffee producers in the world, also stands out as the largest exporter of the product [

1]. In 2022, Brazil had a total coffee production of approximately 50.92 million processed bags. Approximately 54.74 million processed bags are estimated to be produced in 2023, indicating an increase of 7.5% compared to the result obtained in the previous crop due to the biennial production of the crop [

2]. Coffee is a product whose value is associated with its quality standard. Therefore, developing systems that allow for the harvesting of the best quality product adds value to the product and guarantees a greater return to the producer. One way to obtain a better-quality coffee is by harvesting the fruits in the ripe maturation stage.

Since harvesting requires the most time and has the highest cost in the coffee production chain, producers have used new technologies available in the market to reduce such losses and increase profitability. Understanding the factors that influence the coffee harvesting is essential to improve the efficiency of this operation [

3]. An approach that can be performed to achieve these goals is by using mechanized harvesting. The success of mechanized harvesting can be confirmed in the studies by [

4,

5], who concluded that the mechanized coffee harvesting system has significant technical and economic viability when compared to the manual system due to the reduction in costs and increase in production. An important aspect to be considered is, to improve the efficiency of the mechanized harvesting and also the quality of the final product, the selective harvesting can be performed. Selective harvesting aims to detach the maximum number of ripe fruits while keeping green fruits on the plants for future harvesting process [

3]. This operation can improve significantly the quality of final product, allowing to obtain higher-quality coffees [

6,

7].

Mechanized coffee harvesting has been efficiently performed using the vibration principle, which is based on the transfer of mechanical energy to the fruit–peduncle system that promotes the detachment of fruits from the peduncle [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, poorly configured harvesting machines or those with design deficiencies that employ the principle of mechanical vibrations can cause severe damage to plants, such as defoliation and excessive branch breakage, directly impacting plant productivity in the next few years. Therefore, it is necessary to study the aspects of harvesting that involve mechanical vibrations in machines, as well as the interactions between machines and plants [

15,

16].

Thus, knowledge of the coffee modal parameters, such as the natural frequency, is essential to understand the behavior of the plant when interacting with the harvesting machine and to assist in the development and improvement of these machines, which will lead to a reduction in the damage caused to plants and increased efficiency during mechanized or semi-mechanized harvesting [

17,

18].

Such parameters can be determined by means of modal analysis. These parameters can be used to study the dynamic properties from excitations caused by vibrations. Modal analysis is based on the measurements and study of the dynamic response of systems when subjected to an external force. Whether numerical or experimental, it is an important tool for determining, improving and optimizing the dynamic characteristics of mechanical systems [

19]. In addition to coffee cultivation, modal analysis has also been applied in studies that were conducted to develop machines for the mechanized harvest of apricots, oranges, pistachios, olives, jujubes and grapes [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

There are many studies of the dynamic behavior of fruit–peduncle, fruit–peduncle–branch and coffee plant systems through numerical and experimental modal analysis [

30,

31]. However, these studies, conducted in laboratory conditions, have focused on the modal properties of coffee, with an emphasis on analyzing the plant’s subsystems. It is believed that conducting a comprehensive characterization study of the coffee plant’s dynamic response under field conditions could lead to significant advancements in existing equipment and the creation of new machinery. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to determine the natural frequencies and damping ratios of the arabica coffee, Catuaí Vermelho variety, under field conditions using experimental modal analysis at different positions along the plants and considering the immature and mature ripening stages.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, a methodology for determining the natural frequencies and damping ratios of coffee plants by means of modal analysis based on impulsive excitation will be presented. The process is defined in three stages: instrumentation for data acquisition, experimental modal analysis, and scenario assessment.

Figure 1 shows a summary of the proposed methodology for the study. All instruments used for the implementation of the methodology are detailed in posterior sections

2.1. Characterization of the Experimental Area

The experiment was conducted at the Cedro farm, located in Nazaré de Minas, in the district of Nepomuceno, in the south of the state of Minas Gerais, at an altitude of 809 m, latitude of 21°05′ S and longitude of 45°18′ W. The farm covers approximately 28 hectares, of which 2.17 hectares are intended for Arabica coffee of the Catuaí Vermelho variety, as shown in

Figure 2. The plants had an average height of 3.10 m and an age of 12 years.

The plants are pruned using the skeleton pruning technique, which consists of cutting the ends of the plagiotropic branches near the orthotropic branches of the coffee tree, from the bottom to the top, leaving them with an average length of 20 cm to 30 cm, with the objective of promoting the opening of the crop and renewing the productive stems [

31]. Pruning is conducted in a cyclical manner, being performed during one year and then allowing vegetative development in the following year. Thus, this cycle is repeated every 2 years to promote growth of new branches for future production.

For the present research, 15 coffee plants were chosen randomly. The evaluated plants contained fruits at two ripening stages, immature and predominantly mature. The trials were conducted in the field during the 2022 crop year, following the evolution of the fruit ripening stage. Firstly, the trials were performed, considering the 15 coffee plants, when the fruits were in immature ripening stage. Later, with the evolution of the fruits ripening stage, the trials were performed again, at the same plants.

To characterize the influence of the plant architecture, tests were performed at different positions along the axis defined by its orthotropic branch, namely, the lower, middle and upper thirds. Additionally, the plants were characterized with regard to the length of the plagiotropic branches in the different thirds evaluated.

2.2. Determination of the Natural Frequencies of Coffee Plants

To determine the natural frequencies and damping ratios of coffee plants, experimental modal analysis tests were performed based on impulsive excitation to obtain the frequency response functions.

The experimental modal analysis follows the reverse path of theoretical modal analysis, starting with the measurement of the response of the structure. First, a force of known magnitude was applied to the structure. Subsequently, vibrations were created with transducers that were arranged in the structure at representative points. Then, the vibrations were measured with the data acquisition system NI cDAQ-9174 chassis and an NI 9234 module with four channels. Finally, by processing the excitation and response signals, it is possible to estimate the respective frequency response functions (FRFs). A damped system with multiple degrees of freedom can be represented by Equation (1).

where [

M], [

C] and [

K] are the matrices of the mass, damping and stiffness, respectively;

,

, and

are the vectors of the displacement, velocity and acceleration, respectively; and {

f(

t)} is the vector of the applied external forces, which is represented by Equation (2).

where {

F} and ω are the harmonic excitation force and the forcing frequency, respectively. This system of equations has a particular solution represented by Equation (3).

where {

X} is a complex vector of response amplitudes dependent on ω and the system parameters. By differentiating {

x(

t)} once, the velocity vector can be determined. By differentiating again, the acceleration vector can be calculated.

By substituting Equations (2) and (3) and their derivatives into Equation (1), it can possible to obtain Equation (4) as follows.

An alternative way of representing Equation (4) is to consider the dynamic properties of the system, which contains a mathematical expression that relates the output {

x(

t)} with the input {

f(

t)}, according to Equation (5).

where

H(ω) is a complex frequency function called the frequency response function (FRF) of the system. As defined, this FRF is called the receptance, which relates the displacement response and the excitation force applied to the system. However, the dynamic response of the system can be expressed in terms of any convenient response characteristic, and it depends on the way in which the vibration will be measured. Thus, the FRFs can be obtained in terms of the velocity and acceleration, which are known as the mobility and inertia, respectively [

32,

33,

34,

35].

Despite having a simple appearance, Equation (5) tends to be inefficient in numerical applications, making its use quite limited. To solve this problem, it is necessary to perform inversion of an NxN matrix for each frequency value. Therefore, it is necessary to use methods such as the Fourier transform to solve these problems.

If

samples of

are collected in discrete time values, the data can be used to obtain the discrete form of the Fourier transform according to Equation (6).

where

,

, and

can be determined with Equations (7)–(9), respectively.

Equations (7)–(9) denote

algebraic equations for each of the

samples and can be expressed in matrix form according to Equation (10).

where

is the sample vector,

is the vector of spectral coefficients and

is the matrix composed of the coefficients

and

. The frequency content of the signal or system response can be determined from the solution of Equation (11).

Additionally, the data acquisition system provides information about the coherence function. This function refers to the measurement of the relationship between the power of the response signal and the input according to Equations (12)–(14) [

19]. It can also be interpreted as being analogous to the correlation coefficient applied to the frequency domain and as a measure of the noise present in the signals. Such a function can be used to verify the quality of the measured signal, with a real value between 0 and 1. The closer the coherence function is to 1, the less influenced the signals are by noise [

19].

In the previous equations, is the power eigenspectral density of the response; is the power eigenspectral density of the excitation; and are the cross-power densities between the excitation (strength) and the response, respectively; and is the frequency response function that links the excitation and the response.

Two estimators, called

and

, can be obtained for the FRF. These estimators are represented by Equations (15) and (16). The

estimator is mainly influenced by the noise present in the input signal, while the

estimator is significantly influenced by the noise present in the output signal.

The coherence function is defined as the ratio between the two estimators, according to Equation (17).

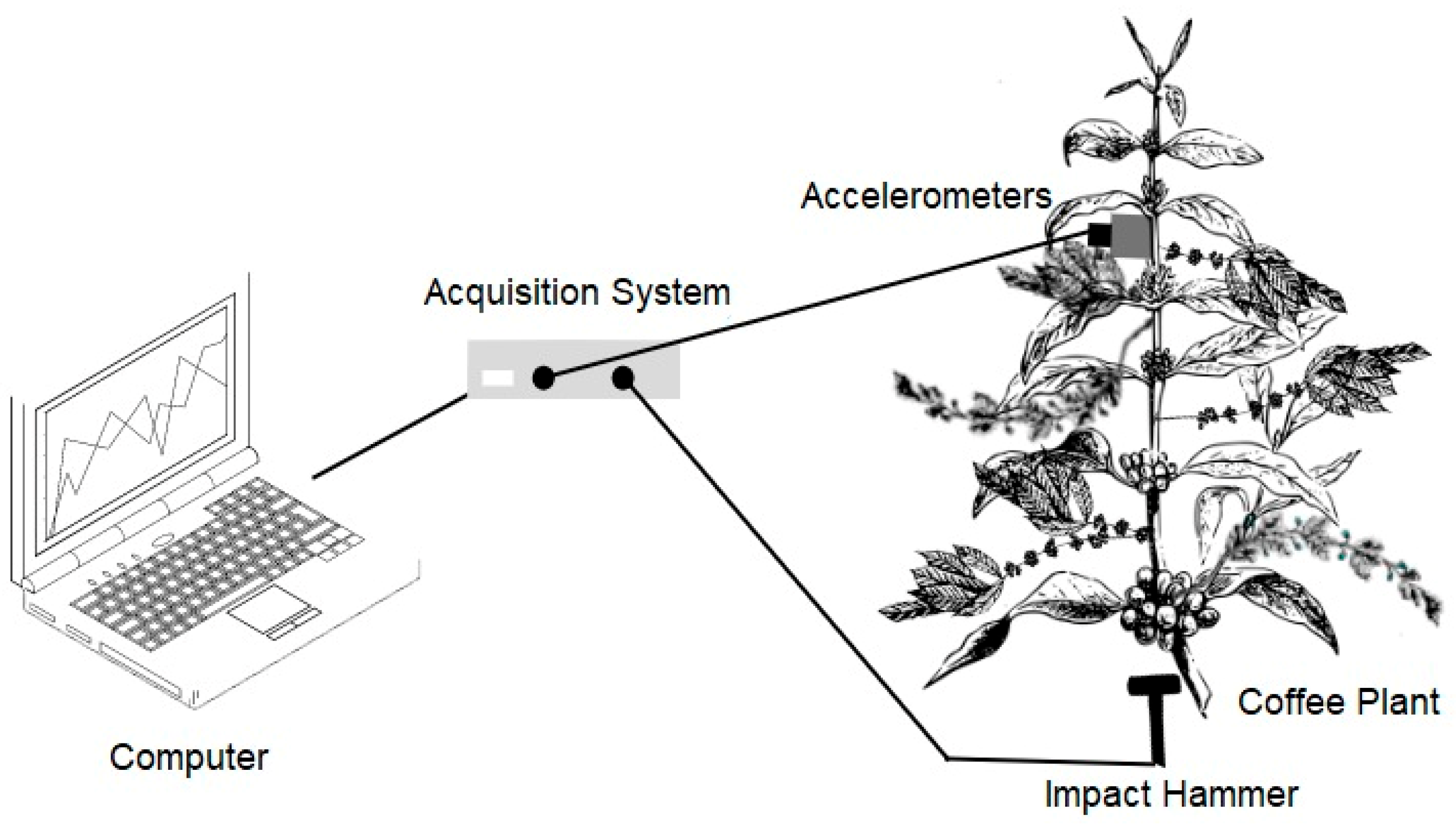

To obtain the FRF of the coffee plants, an impulsive excitation was used. This impulsive excitation was produced with an impact hammer, and the acceleration was measured with high-sensitivity accelerometers placed in the plant, as shown in

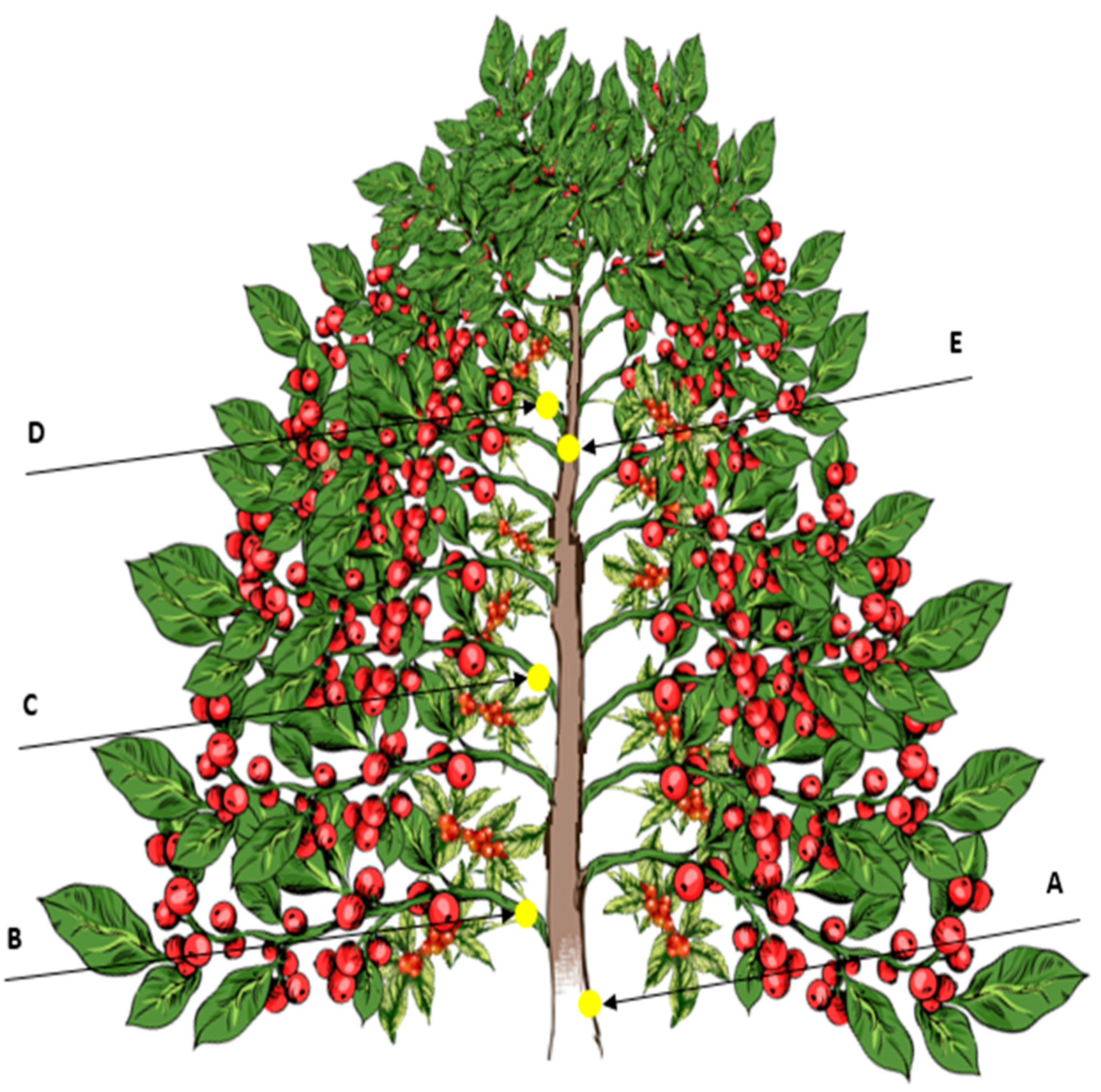

Figure 3. The impact was applied at Point A. Throughout the plant, the responses to the excitation were obtained from accelerometers that were attached with adhesive tape at the following 4 different points: B, C, D and E.

The locations where the impacts (excitation) occurred and where the plant responses were determined with accelerometers were scraped to remove the trunk bark to prevent the damping effects of the impact force from affecting the vibration measurements.

The acquisition of coffee plant acceleration signals was performed using a National Instruments data acquisition system consisting of an NI cDAQ-9174 chassis and an NI 9234 module with four channels.

The acquisition system was connected to a computer and managed by LabVIEW version 14.5 software. Using an impact test routine available in the Sound and Vibration package, it was possible to determine the FRF, the coherence values and the phase of the tests performed in the coffee plants. The data were collected considering a frequency range of 0 to 100 Hz and with a resolution of 0.1 Hz. The experimental setup scheme is illustrated in

Figure 4.

For each test, five replicates were performed with the impact hammer using the acceptance/rejection criterion based on coherence (Equation (17)). Values equal to or close to 1 indicate a good estimate of the FRF of the mechanical system studied. Notably, between impacts, it was necessary to wait for the plant to stabilize again.

The frequency and amplitude data were stored and FRF graphs were drawn. The natural frequencies of the system were determined from these graphs. A moving-average filter (moving-average filter) was used to process the data. This filter smoothed the noisy data through windowing. For this study, a window length of 20 was used for the orthotropic branch, and a window length of 10 was used for the plagiotropic branches. With the data obtained, the frequency response function graphs were plotted, and the natural frequencies of the systems were obtained through representative peaks selected in specific frequency ranges, namely, 10–20 Hz, 20–30 Hz, 30–40 Hz, 40–50 Hz and 50–60 Hz.

2.3. Quantifying Damping Ratios in Coffee Plants

Regarding the ripening stage, the damping ratio of the system was determined using the logarithmic decrement method, which allows us to determine it experimentally by measuring any two consecutive displacements and taking the natural logarithm of their amplitudes [

35]. According to [

34], the logarithmic decrement represents the rate at which the amplitude of a free damped vibration decreases, as shown in

Figure 5, which illustrates the theoretical response of an underdamped system after the application of the impulse.

Therefore, to obtain the decay curves of the coffee plant oscillation over time, an impulsive excitation created with the impact hammer was applied. The impact was applied to the base of the plants, and the acceleration was measured using high-sensitivity accelerometers placed on the plagiotropic branches of the plants, following the same scheme illustrated in

Figure 3. Specifically for this experiment, for each test, three replicates were performed with the impact hammer, and between each impact, it was necessary to wait for the plant to return to rest. Notably, the excitation orientation was the same as the response measurement.

The acquisition of the coffee plant acceleration data was performed by developing a code routine in LabVIEW software, which manages the same data acquisition system used previously in the experiment. Through this routine, it was possible to store the data of the acceleration, and later, it was feasible to trace the curves and determine the damping ratios of the plagiotropic branches in their respective thirds, considering predominance of ripe fruits.

The relationship between the value of the logarithmic decrement after

cycles of oscillation and the damping ratio of the system under study is represented by Equation (18).

where

is the damped period of oscillation,

is the value of the amplitude after

damped periods,

is the value of the initial amplitude,

is the damping ratio and

n is the number of cycles used to measure the amplitude.

2.4. Statistical Data Analysis

To evaluate the influence of the ripening stage of the fruits on the natural frequencies of coffee plants, an experiment was conducted according to a completely randomized design, with 15 replications.

The natural frequencies of the plagiotropic branches, obtained by experimental modal analysis, were evaluated according to a completely randomized design in a 3 × 2 factorial design (plant positions × fruit ripening stages), with 15 replications.

To evaluate the influence of the position on the damping ratios of coffee plants, an experiment was conducted according to a completely randomized design with 15 repetitions.

For all evaluated experiments, the data were subjected to the Shapiro–Wilk normality test and, subsequently, to analysis of variance considering a significance of 5%. The means of the response variables were studied using Tukey’s test at a 5% probability. Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.2.1.

3. Results

The natural frequencies of the coffee plants were obtained by means of experimental modal analysis tests based on impulsive excitation and identified by means of frequency response functions (FRFs) based on the amplification of the vibration amplitude at each sampling point.

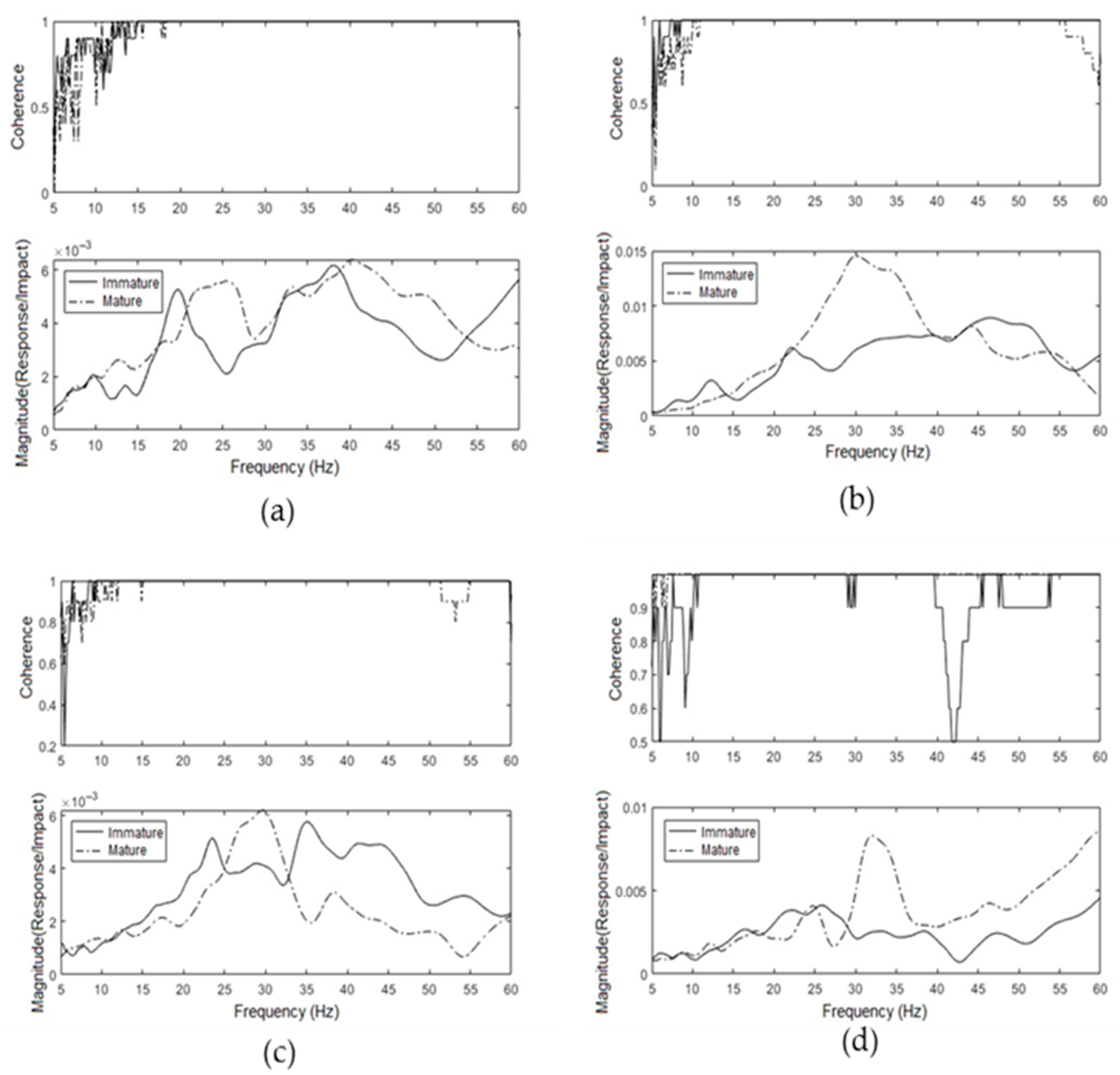

Figure 6 illustrates the FRFs of the upper third of the plagiotropic branches of Plants 11, 12, 15 and 17 for the mature and immature stages, together with the coherence information obtained during the tests.

The quality of the test performed can be evaluated based on the coherence value. This value indicates whether there is noise between the impact hammer and accelerometer signals [

36]. To identify the frequencies in the FRFs, the coherences in the intervals of interest were evaluated concomitantly. It was found that the coherence was always higher than 0.8, which indicates that the response signals between the impact hammer and the accelerometer were linearly correlated, without interference or noise. Since the experiment was conducted outdoors under field conditions, such a result is expected since external factors, such as wind, can directly influence the reduction in the coherence value.

In addition, it can be observed that the highest incidence of frequency peaks was concentrated between 20 and 40 Hz. Regarding the ripening stages in the lower and middle thirds of the plagiotropic branches, it was observed that the frequency peaks had a higher incidence in the frequency range from 20 to 30 Hz. Regarding the plagiotropic branches of the upper third and orthotropic branches of plants with predominantly ripe fruits, the highest occurrence of the frequency peaks was observed in the range of 30 to 40 Hz. Regarding the plants with predominantly immature fruits, the highest incidence of fruits occurred in the range from 20 to 30 Hz. Additionally, there was also a higher incidence of frequency peaks for immature fruits than for ripe fruits.

Figure 7 shows the mean frequency values extracted for each third of the plant, in each frequency band analyzed, for the plagiotropic branches and for the orthotropic branch.

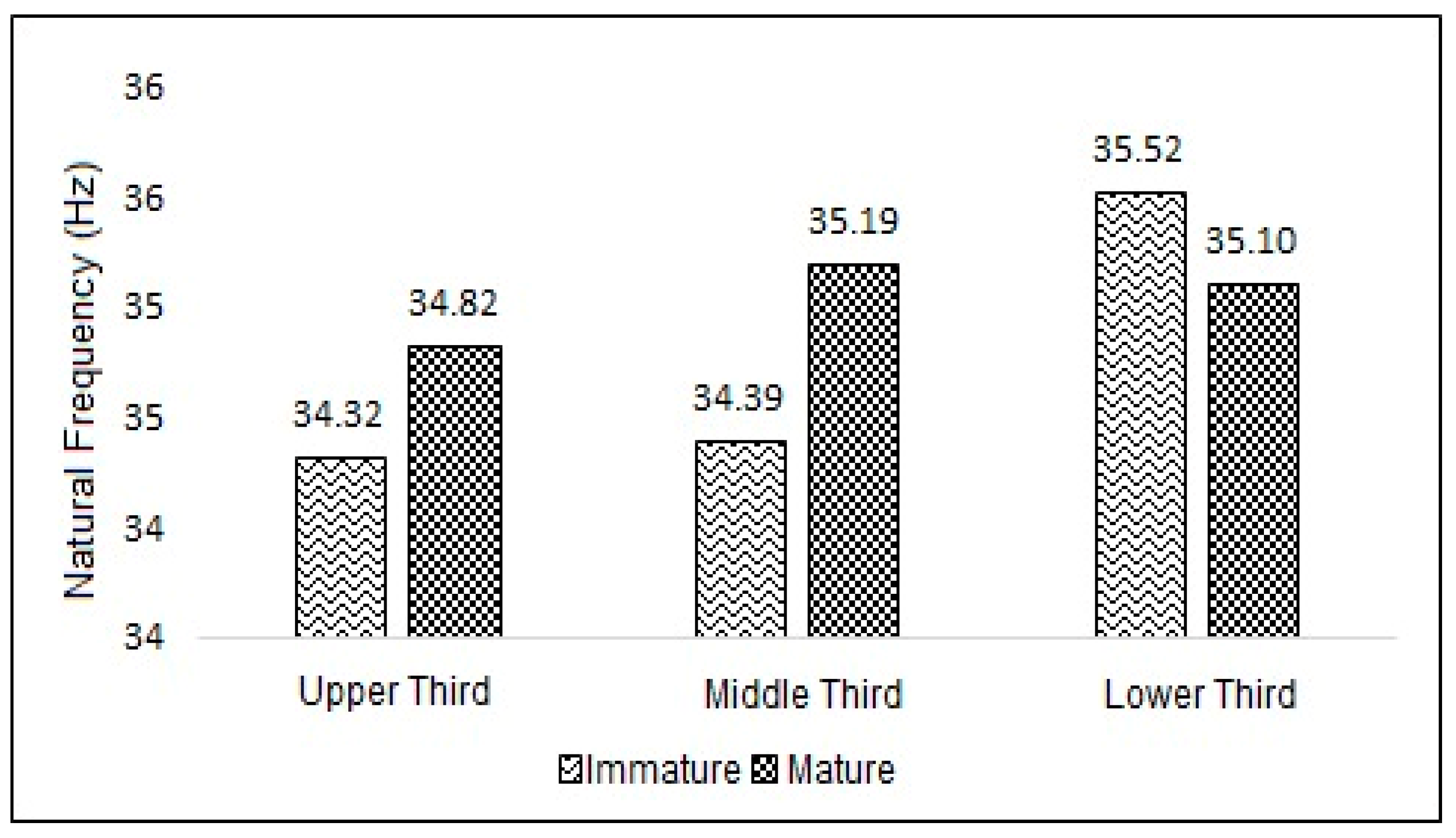

The mean natural frequency values for each position in the plant according to the ripening stage are shown in

Figure 8. It can be observed that regardless of the fruit ripening stage, the average natural frequency values are similar.

The natural frequencies obtained experimentally were subjected to an analysis of variance, and the results are shown in

Table 1. No significant differences were found at the 5% significance level, at different positions in the plant and at different ripening stages for any of the natural frequencies studied for the plagiotropic branches. This result was already expected according to the data that were presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

However, when evaluating the fourth frequency range, which varies from 40 to 50 Hz, the positions of the plants had a significant effect on the natural frequency, as shown in

Table 2. The consequences of this effect are presented in

Table 3, which shows that the natural frequency value for the lower third of the plagiotropic branches is higher compared to the middle and upper thirds.

As in the plagiotropic branches, when submitting the natural frequencies experimentally found for the upper third of the orthotropic branches to analysis of variance, no significant differences were found at the 5% significance level for the different ripening stages, as shown in

Table 4.

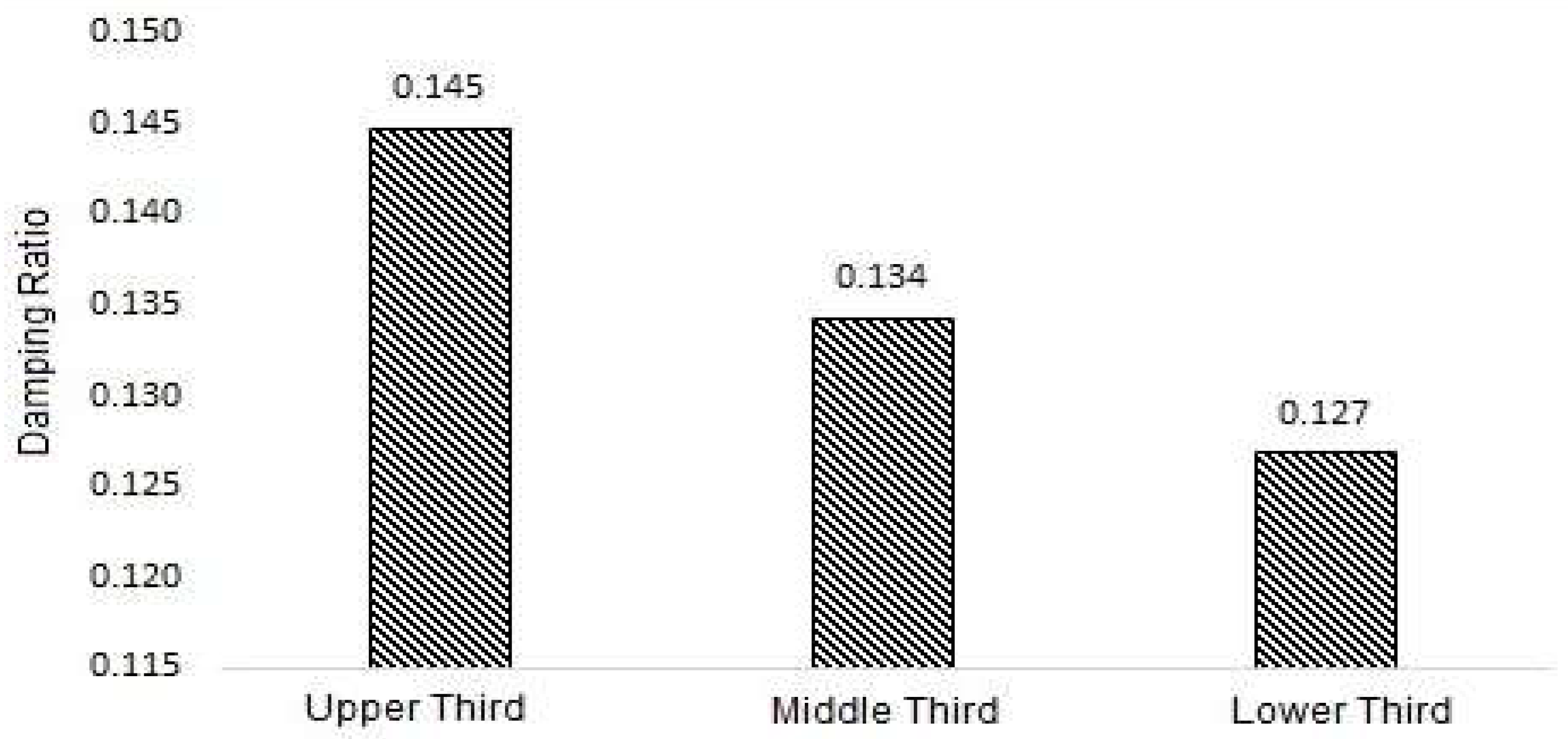

The damping ratio of the plagiotropic branches of the coffee plants was performed using the logarithmic decrement method for the mature stage. The interaction between the position of the plant and the damping ratio was not significant at the 5% significance level. The average damping ratio values for each position of the plants in the mature stage are presented in

Figure 9.

4. Discussion

During an evaluation of the coffee plant variety Catuaí Vermelho in the laboratory, [

18] observed that the highest incidence of frequency peaks was concentrated between 10 and 30. Reference [

33] found similar results with regard to only coffee fruits, with frequency bands with specific resonant peaks between 24 and 45 Hz, where ripe fruits presented greater magnitudes in the calculated parameters, for the Castillo variety. Both results agree with those found in this study.

Using the stochastic finite element method, [

37] evaluated the fruit-stem-stem system of coffee for the green and ripe ripening stages. From the results of the simulations, natural frequencies between 14 and 21.3 Hz were identified. Similarly to the aforementioned authors, the results of the simulations performed in my study showed natural frequencies in the range of 14 to 26 Hz, corroborating the previous findings. In addition, the authors found that as the number of fruits increases on the branch, the values of the natural frequencies tend to decrease, which suggests a concordance between these factors in both studies.

The results obtained by [

29] on the fruit–peduncle system of Arabica coffee, variety Colombia, are consistent with those presented in this study. They identified the first 20 natural frequencies and the vibration modes of the system using the finite element method at all ripening stages. The values of the natural frequencies found, which ranged from 16.33 to 49.43 Hz for the first three vibration modes, corroborate the results obtained in this study.

It is expected to find a variation in the results among different authors due to variations in the geometric, physical and mechanical properties of the plants under study, since these properties are associated with the characteristics of the soil, climate and plant, such as the age, variety and management of the plants [

26]. However, the results obtained in this study corroborate the aforementioned literature. Therefore, regarding this form of vibration transmission, under the conditions in which the experiment was performed, there is no possibility of achieving selectivity in the harvest of coffee fruits. However, a full harvest of fruits can be obtained by only using vibrations.

The suitable combination between frequency of vibration and amplitude can influence directly on the harvesting efficiency, also impacting on the costs of this operation. The detachment efficiency of coffee fruits increases with the increasing of frequency and amplitude factors during the harvesting process, as observed by [

38]. On the other hand, when vibrations are combined with impacts, selective harvesting can be performed because the efficiency of fruit detachment increases as the ripening stage progresses from unripe to ripe. This behavior can be explained by the fact that the peduncle exhibits less rigidity at the most advanced ripening stage of the fruit [

38] due to degradation of stem cell walls by enzymatic activity activated by the hormone ethylene. Degradation of the cell wall makes the peduncle fragile, reducing its elastic modulus and, consequently, the force needed for its rupture.

When evaluating the first frequency band alone, the means of the position in the plant factor were statistically equal, with values of 15.95, 15.38 and 14.44 Hz for the lower, middle and upper levels, respectively. Additionally, according to the analysis, the means of the ripening stages were nonsignificant, with values equal to 15.19 Hz for the immature stage and 15.04 Hz for the mature stage. The same occurred when the second, third and fifth frequency bands were evaluated separately, in which the means of the plant positions were statistically equal and the means of the ripening stages were not significant.

The means of the ripening stages were nonsignificant, with values equal to 35.62 Hz for the immature stage and 33.43 Hz for the mature stage (

Table 2). Thus, the selective harvesting of fruits only by the action of mechanical vibrations is unfeasible. This result was also observed by other researchers [

11,

25,

30,

31]. However, when evaluating the fourth frequency range, which varies from 40 to 50 Hz, the positions of the plants had a significant effect on the natural frequency, as shown in

Table 2. The consequences of this effect are presented in

Table 3, which shows that the natural frequency value for the lower third of the plagiotropic branches is higher compared to the middle and upper thirds.

The vibration transmissibility data were obtained by inducing mechanical vibrations in the coffee plants using the RMS acceleration values at each acquisition point of the accelerometers based on the value at the initial point in the orthotropic branch at the base of the plants, as shown in

Figure 3.

Moreover, the transmissibility tends to decrease in the frequency range of 25 to 30 Hz and increase at a frequency of 35 Hz for the ripening stages studied, regardless of the position in the plant. This behavior can be attributed to the fact that the resonant frequency of the plants is not close to this frequency range.

Ref. [

14] evaluated a methodology for the selective harvesting of coffee, cultivar Catuaí 99, and the optimal harvester configurations in each management zone and observed that harvesting the upper third of the coffee tree first yielded better beverage quality and less sweeping coffee. This is because the upper third of a coffee plant exhibits different spatial variability in relation to the middle and lower thirds. These results highlight the importance of considering plant heterogeneity when performing selective harvesting, contributing to improving both the quality and efficiency of the process.

In addition, in the upper third, the fruits are not shaded by other plants, and the branches have few leaves because those are younger. Therefore, the fruits have a greater exposure to sunlight, causing an acceleration of the ripening of the fruits and allowing them to fall precipitously from the branches. As in this study, no significant difference was found between the values of the natural frequency of the upper and middle thirds, and performing the collection of these thirds first may produce positive results [

14].

When performing the characterization of coffee plants in relation to the average length of the plagiotropic branches between the different thirds of the plant, it was observed that in the lower third, the average length of the plagiotropic branches was 474.28 mm, while in the middle third, it was 636.23 mm. In the upper third, the longest average length was observed with a value of 693.73 mm. These data demonstrate heterogeneity in the development of the plagiotropic branches throughout the coffee plant, with a trend of progressively greater growth from the lower third to the upper third.

When evaluating the lower third of coffee plants, it is possible to observe that it has plagiotropic branches with a greater average length than those located in the upper part of the plant. The greater stiffness, due to the morphological characteristics of adult wood, may influence the average natural frequency of the branch [

39,

40]. These factors show why the values of the natural frequencies obtained for the lower third are significantly different, with higher averages in relation to the other positions in the plant.

According to the test presented in

Table 4, the means of the ripening stages were non-significant, with values equal to 31.66 Hz for the immature stage and 32.05 Hz for the mature stage. These results indicate that it is possible to accomplish complete harvesting but not selectivity of the coffee fruits through the application of vibration to the orthotropic branch of the plants. The results found for the orthotropic branch were close to those for the plagiotropic branches, and a similar behavior was observed in other studies available in the literature [

41,

42,

43,

44].

If the harvesting objective is to completely detach the fruits in a single operation, the harvesting machines and devices will be able to reach fruits at both ripening stages by using a frequency band close to the resonance band of the system. Moreover, the results show that the fruit ripening stages and positions of the plants were not dependent for either the plagiotropic or orthotropic branches.

Subsequently, an evaluation of the damping ratio of the plagiotropic branches of the coffee plants was performed using the logarithmic decrement method for the mature stage. The interaction between the position of the plant and the damping ratio was not significant at the 5% significance level. The average damping ratio values for each position of the plants in the mature stage are presented in

Figure 9. The values found for the damping ratio indicate that the plagiotropic branches behave as an underdamped system, as it presented values between 0 and 1 as is also observed for other crops, such as blueberry and grapes [

42,

43].

The study of the fruit–peduncle system of coffee found damping ratio values equal to 0.09 for the ripe stage (cherry) for the peduncles, and for the plagiotropic branch, they found a damping ratio with an average value of 0.02. Ref. [

27] evaluated the damping ratio for the fruit–stemmed coffee system under laboratory conditions using high-speed digital videos and obtained a value of 0.126 for the mature stage. In addition, in both studies, the authors also observed that there was no significant difference between the values of the damping ratio for the mature and immature stages. These results corroborate the results found in this study for the plagiotropic branches.

By using the logarithmic decrement method, obtained values between 0.08 and 0.1 for the damping ratio of the coffee trunk-stem-leaf system. In addition, the authors concluded that coffee leaves favor the damping of excitations caused in the plant. Although the values of the damping ratio did not show a significant difference in relation to the thirds of the coffee plants, a decrease in its value can be observed when evaluating from the upper third to the lower third. Ref. [

44] observed there are some physical properties along the plant that do not change such as specific averages for the orthotropic branches on upper, middle and lower thirds of the plant. This result corroborates with the results in this work.

The results obtained in this study, with insignificant values between different positions of the plagiotropic and orthotropic branches, can be considered important regulation parameters for harvesters. Therefore, according to [

16], the appropriate adjustment of the vibration frequencies and amplitudes of the harvester stems impact the coffee harvesting efficiency, reduce transfer costs, decrease plant defoliation, favor selective harvesting and, consequently, reduce the final costs of the operation of the harvest.

The execution of this work faced several challenges based on the plant instrumentation of the plants as described:—fixation of the transducer at the plant;—distribution of cables from the plant to the acquisition system;—weather conditions, mainly the wind; and—displacement of all instrumentation composed by transducers, acquisition system and computers from the laboratory to the experimental field. However, the proposed methodology can bring a new perspective of the dynamic response of the coffee plants when they are submitted to mechanical vibrations, which can be used on development and improvement of coffee harvesting machines.