Data Evidence-Based Transformative Actions in Historic Urban Context—The Bologna University Area Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

State of the Research: Among Smart Cities, Cultural Heritage-Led Regeneration and Big-Data

2. Case Study Selection in the ROCK Framework

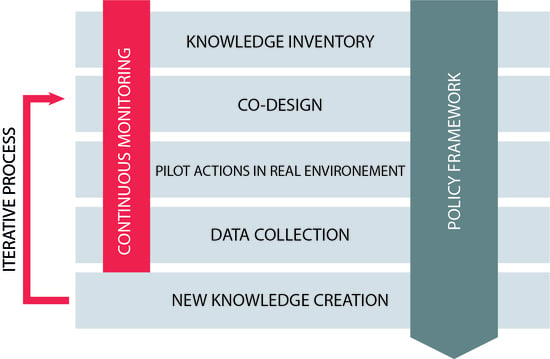

2.1. Research-Action-Research Approach: The ROCK Method for Implementing Actions

- Research. The first research phase aims to create the knowledge base and outline the initial status by collecting data and needs, and identifying key stakeholders, key areas, and key actions and enablers, in order to effectively set up the field for the concrete planning and implementation phase.

- Action. The action phase concerns the implementation of pilot actions according to the first drafting of objectives, topics, and proposals emerged from participatory inquiries. This first action can highlight unforeseen barriers, arise more needs, or suggest additional adjusting actions. Therefore, the process foresees a second research activity.

- Research. The second research phase aims to define more precise and detailed scenarios, which includes not only foreseen actions and tools application, recalibrating the future actions to improve their effectiveness, strengthening week aspects and correcting mistakes, but also considerations about new assumptions to be taken into account, new barriers and risks, new stakeholders, and the connection and clustering of specific actions with new or more precisely identified target groups.

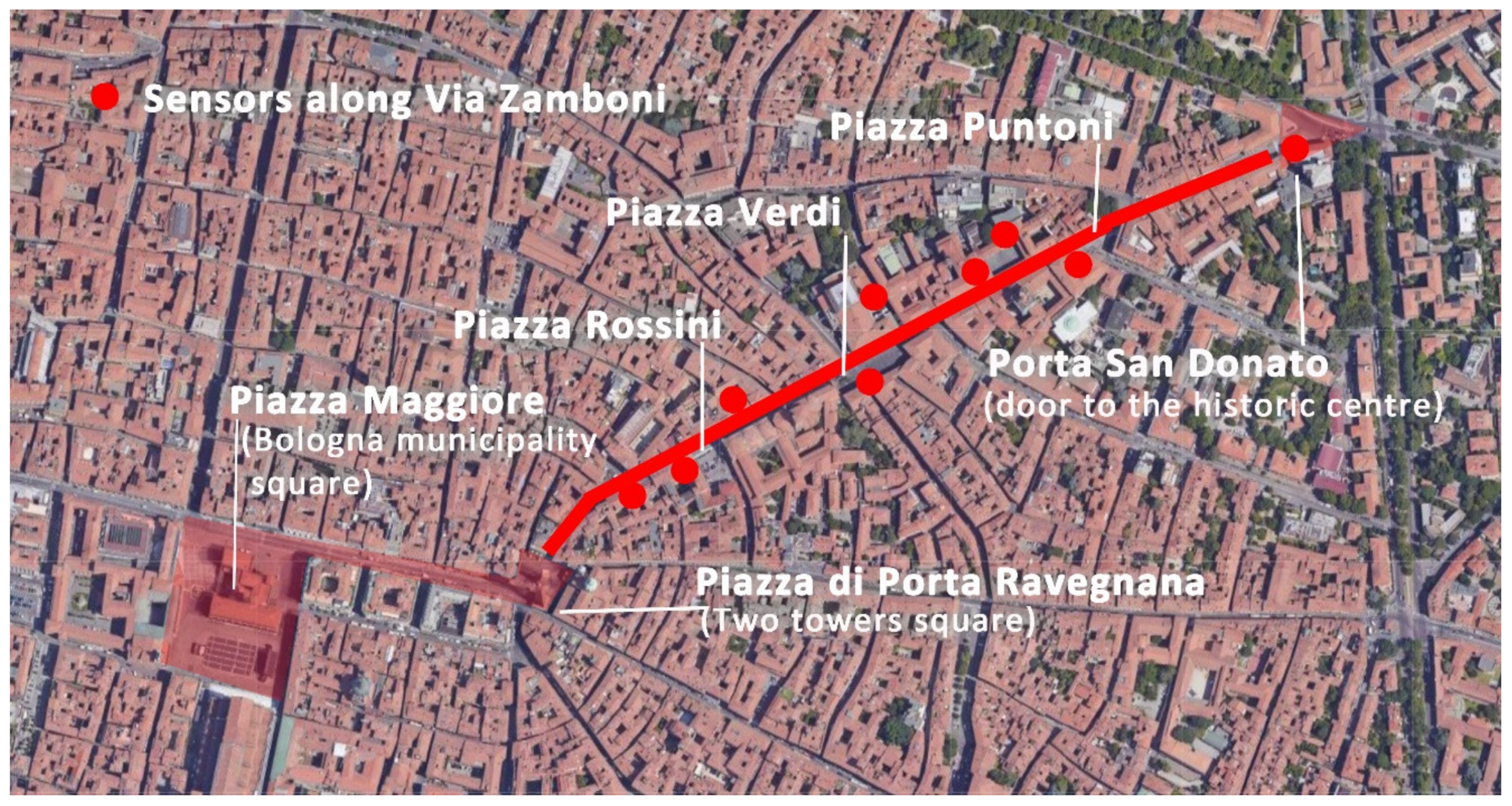

2.2. Case Study Selection

Temporary Spatial Transformations

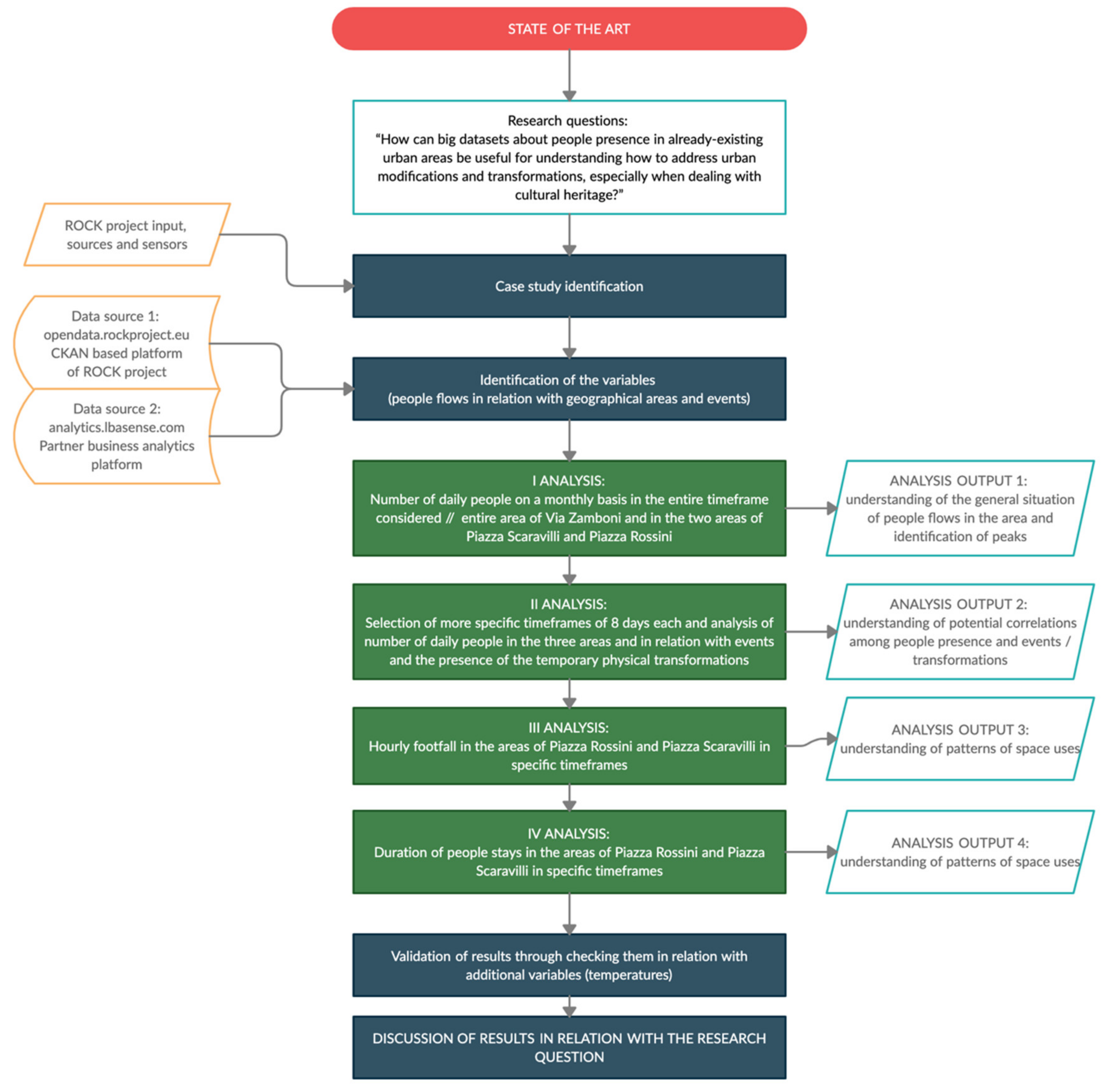

3. Methodologies

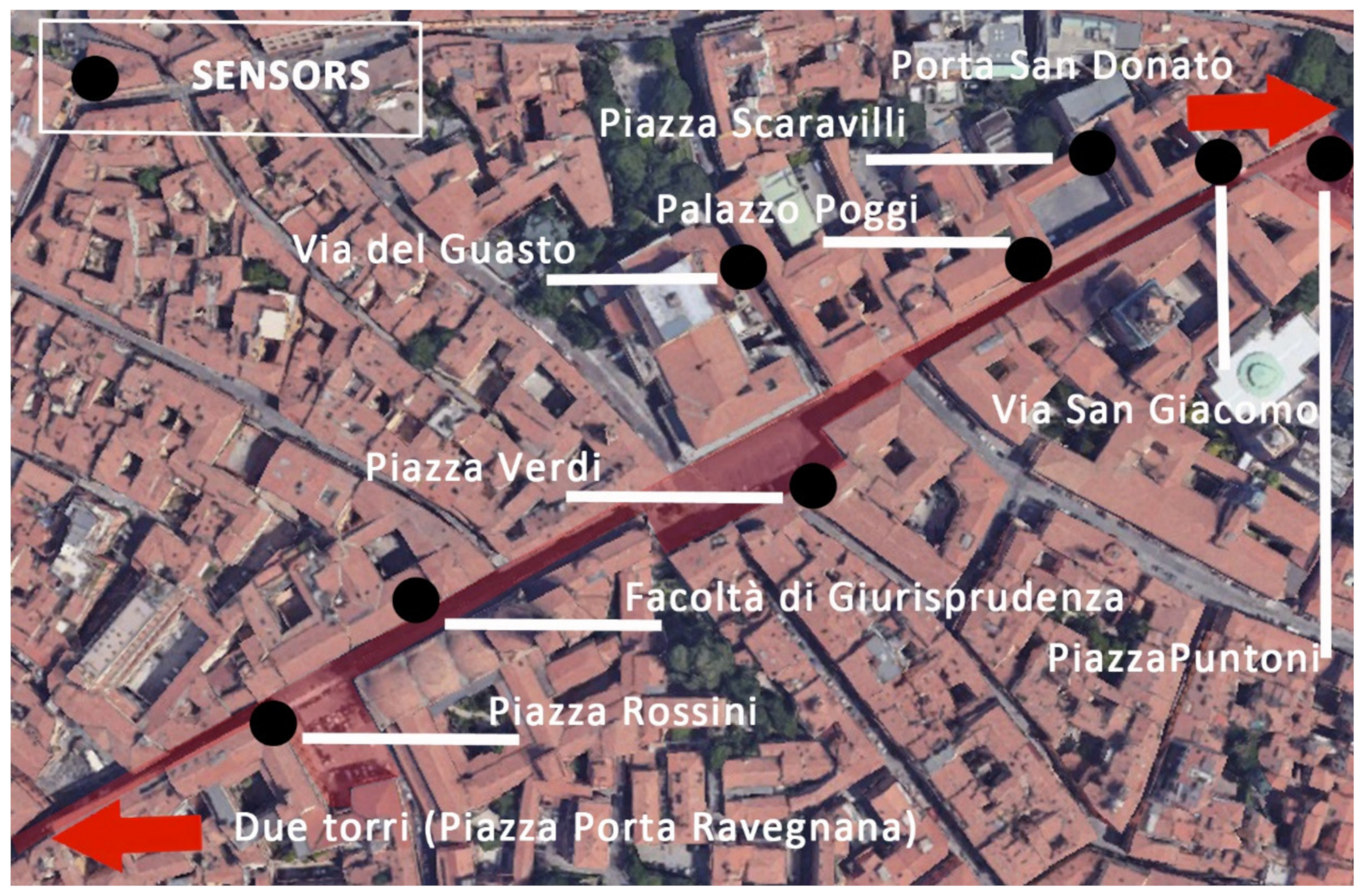

3.1. The Use of Sensors in the ROCK Project in Bologna

3.1.1. Limitations on the Sensors in the Area

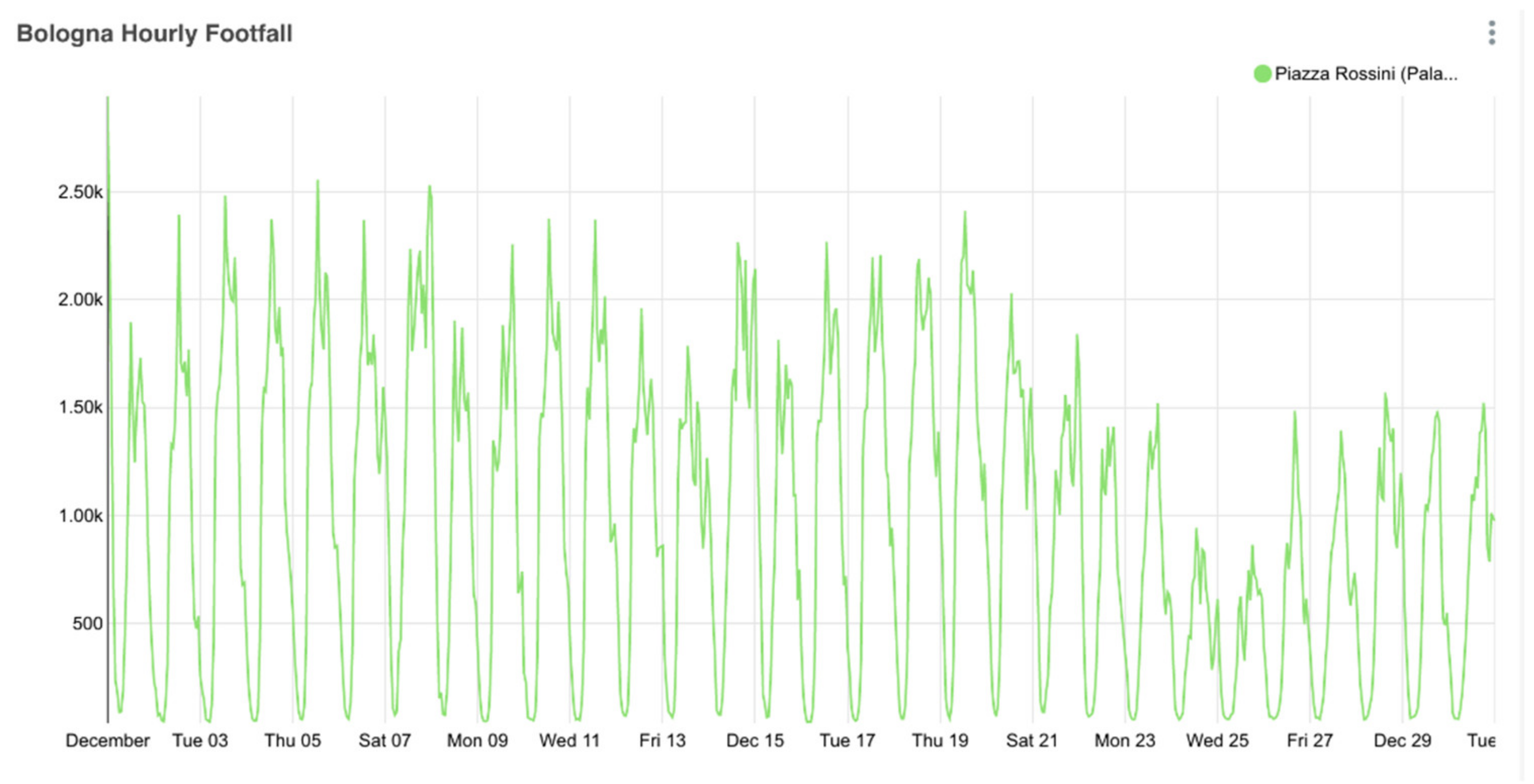

- Geographical limits. The sensors were installed along the street named Via Zamboni according to several boundary conditions, such as the availability of physical space on building façades, the proximity with electrical connection points, the different ownership of buildings, and the needs of the Soprintenza ai Beni Culturali. All those boundary conditions made the selection of the best position for the sensors limited to certain specific spots. For that reason, the municipality and ROCK partners were not able to always place sensors in the best potential spot. In the case of Piazza Rossini, for example, the sensor can detect not only people entering the square but also the ones passing in front of it, causing some interpretation limits. In this study, we acknowledge those limits, and we consider them in the interpretation, as explained in the results and discussion section.

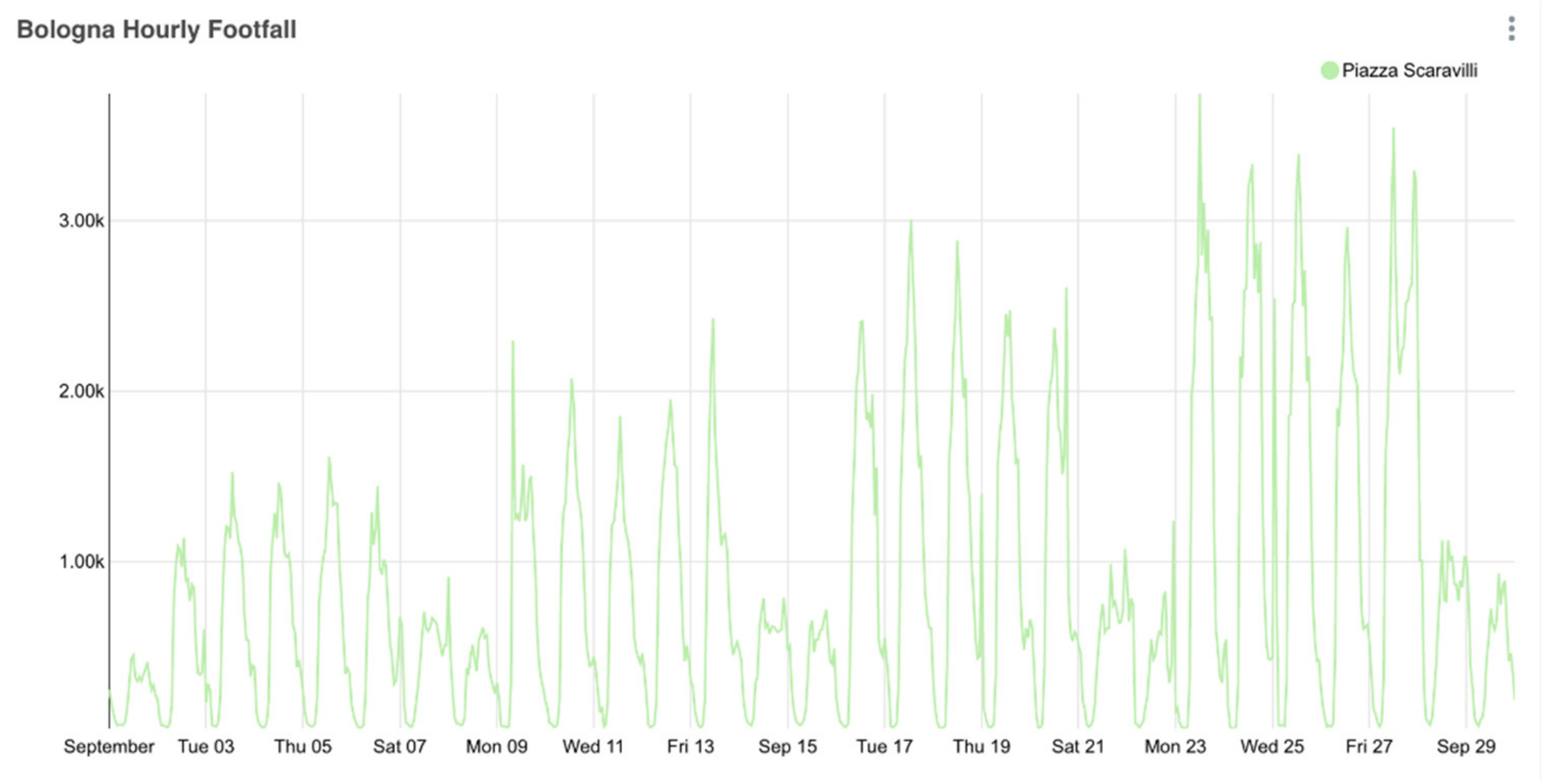

- Time limits and unpredictable events. For the reasons explained in the first point, the time needed for completing the installation was higher than expected. In fact, the municipality and ROCK partners were able to make sensors in function starting from June 2019. The process of acquiring authorization, doing in site inspections, solving technical issues and, finally, the need to address ethical issues, as requested by the European Commission, led to a delay in the installation. Thus, we are not able to compare 2019 results with 2018. Additionally, the emergence of COVID-19 caused a sensor switch-off in the entire area, due to the temporary closing of the partner in charge of them. Finally, the sensor in Piazza Scaravilli encountered some technical issues, thus we have limited availability of data from this site (from November 2019 to July 2020 no data are available). We included the specifications of that in the results and discussion section. However, the project planned to maintain the monitoring active for two years after the project end (December 2020), thus we aim to continue the analysis with these big data. However, even with these limitations, data show interesting features that need to be addressed and taken into consideration.

3.2. Data Analysis Methodology

- The first one dealt with analyzing the total and the average number of people detected by sensors on a monthly basis for the entire available timeframe in the entire area of Via Zamboni and in the two squares of Piazza Scaravillli and Piazza Rossini. This analysis intended to understand the general frequency and amount of people in the areas and to find peaks.

- The second one dealt with analyzing the total and the average number of people detected by sensors in very specific timeframes of eight days each (see Section 3.2.1 for further information on how we chose the timeframes) in the same three areas. This analysis aimed to understand the potential correlations among peaks and the presence of events or physical transformations in the area.

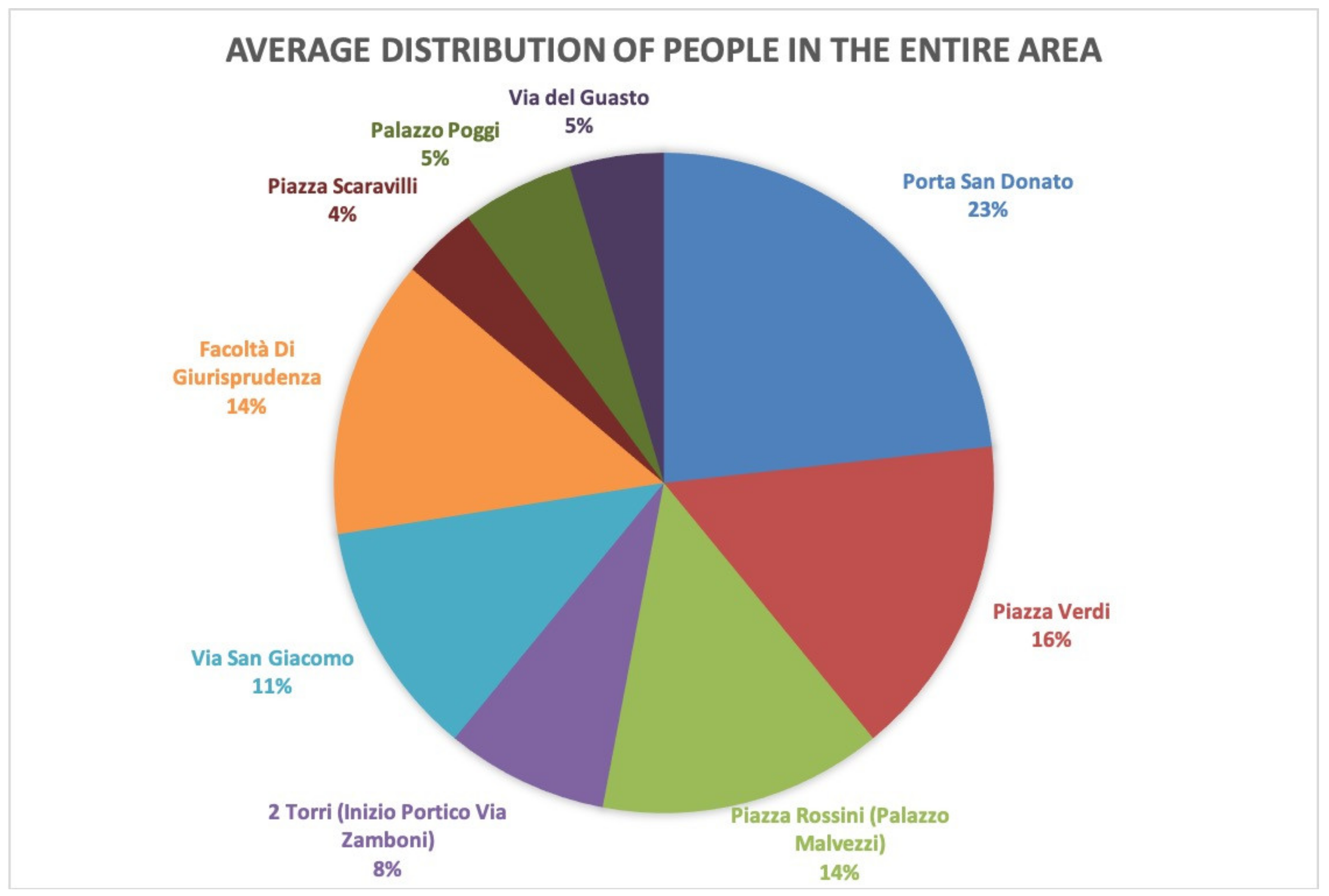

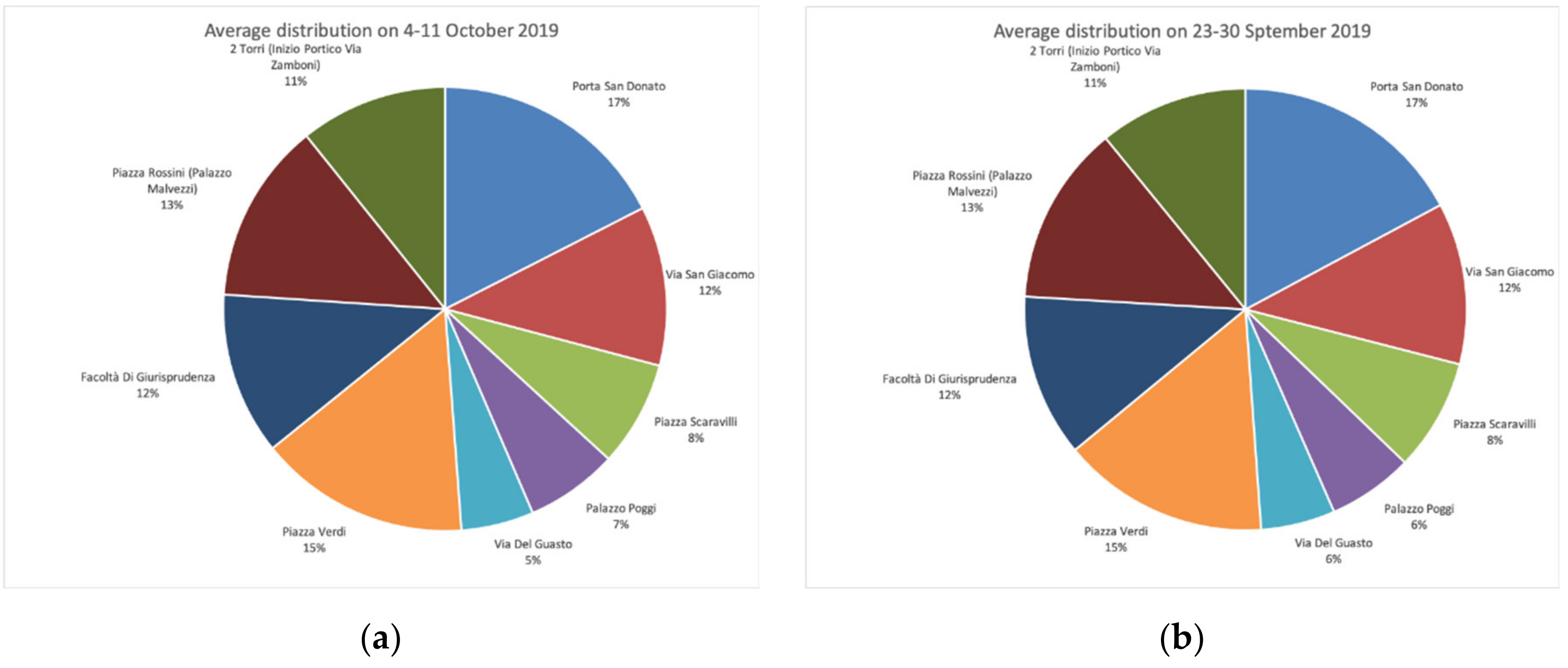

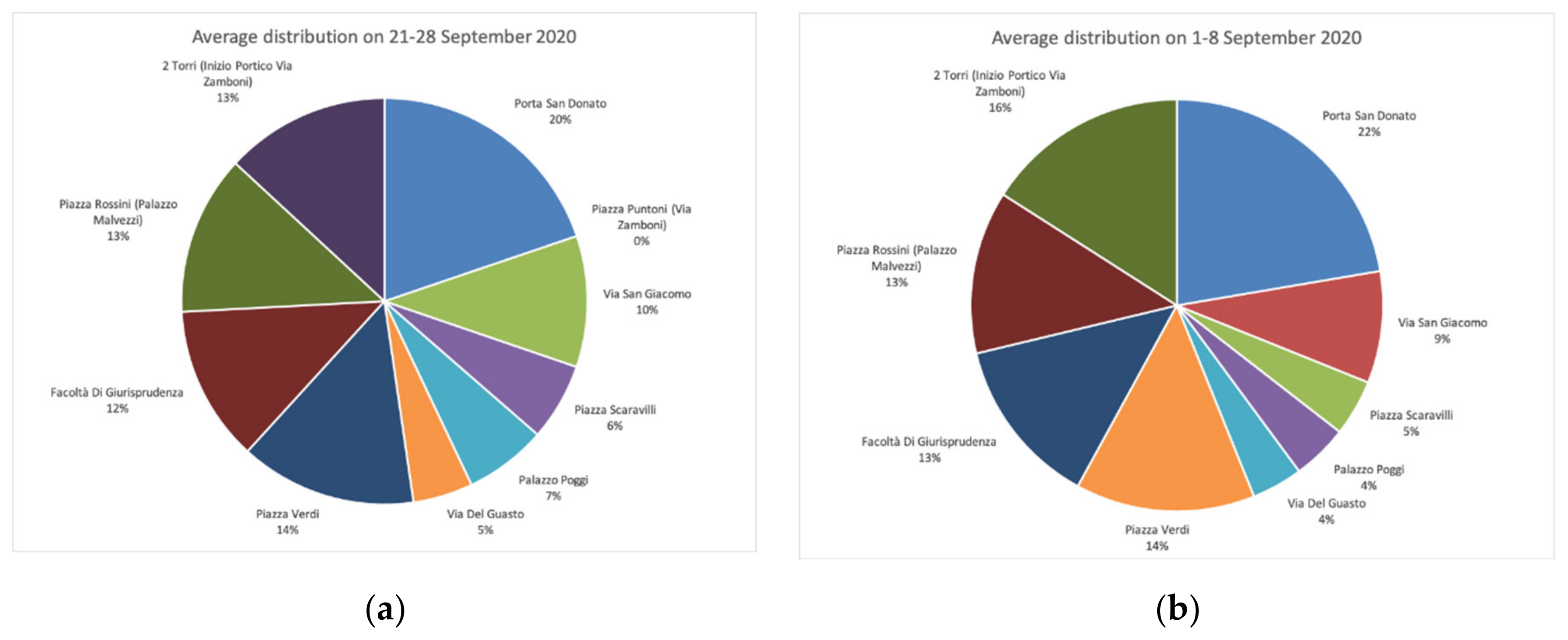

- The third one dealt with understanding the distribution of people in the area. We performed this analysis only for Via Zamboni, in order to understand if there was some variability in relation to the different timeframes.

- Then, we addressed the duration of people in the two squares. This analysis was particularly useful to understand how people tend to use the space and to identify how many people just pass the area and are detected by the sensors, and the ones that have an interest in the specific square and thus they stay longer than 5 min. For this purpose, we found different durations as explained in Table 1.

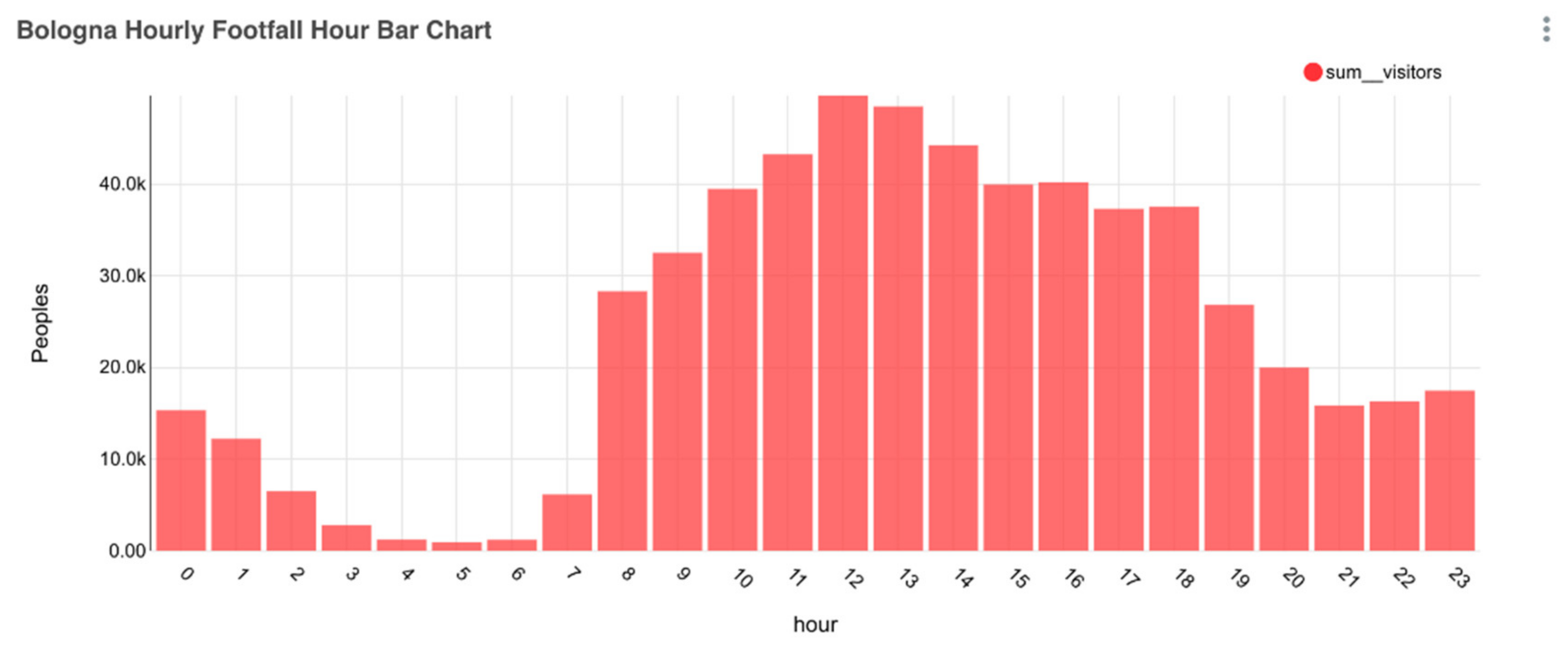

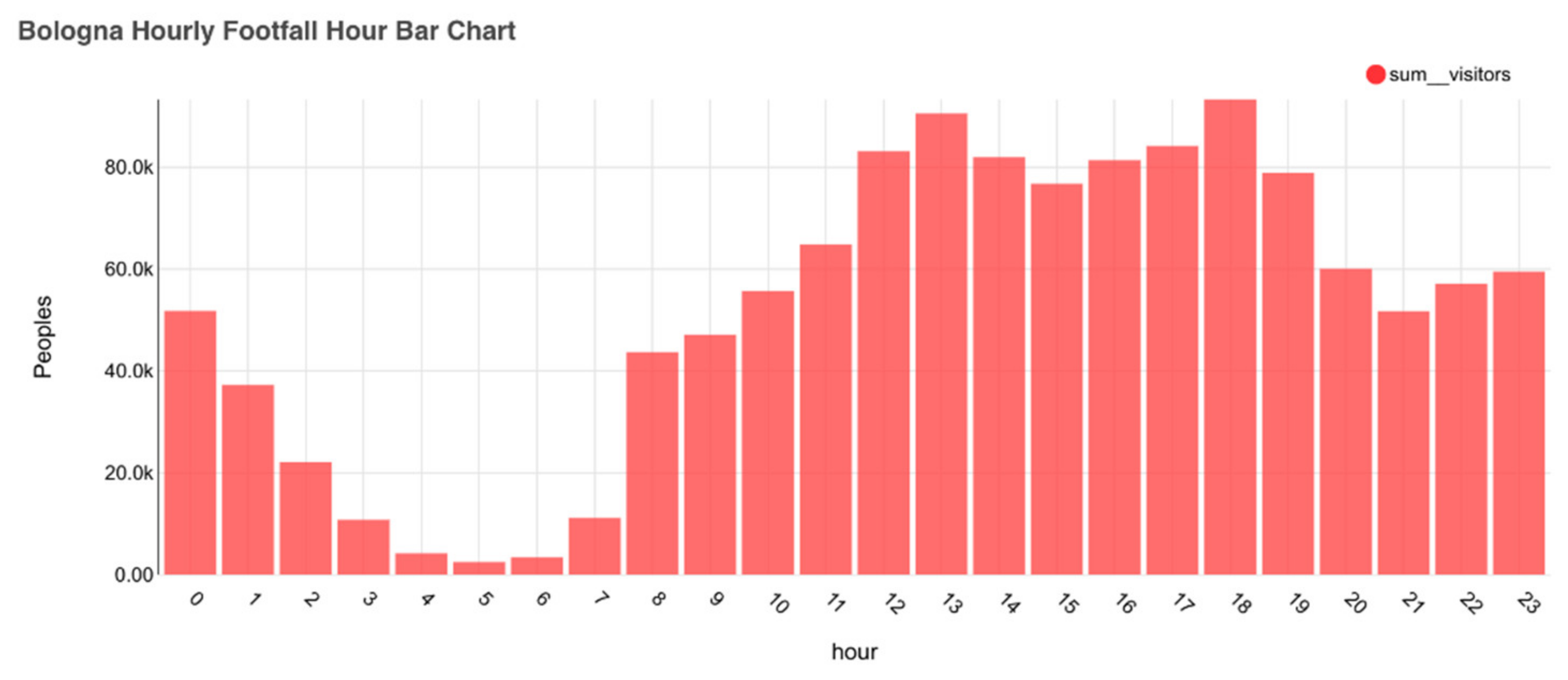

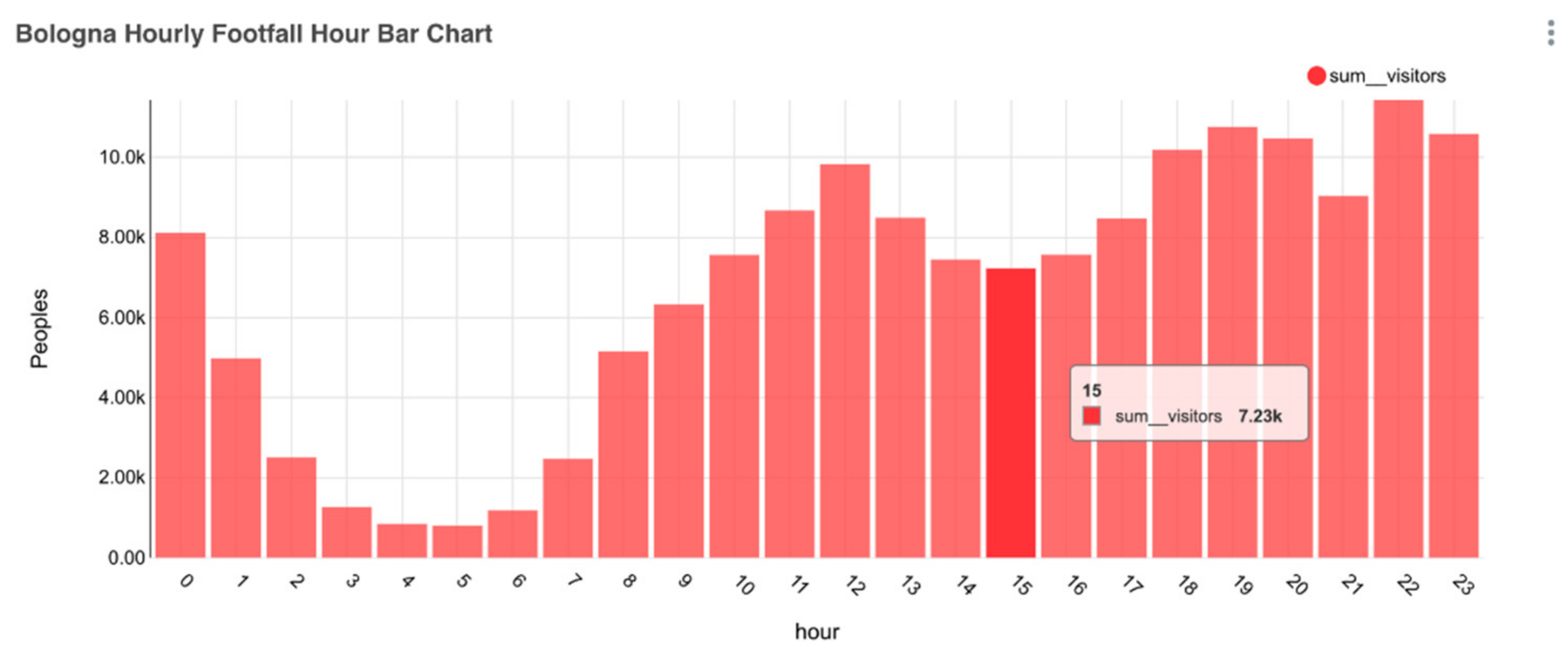

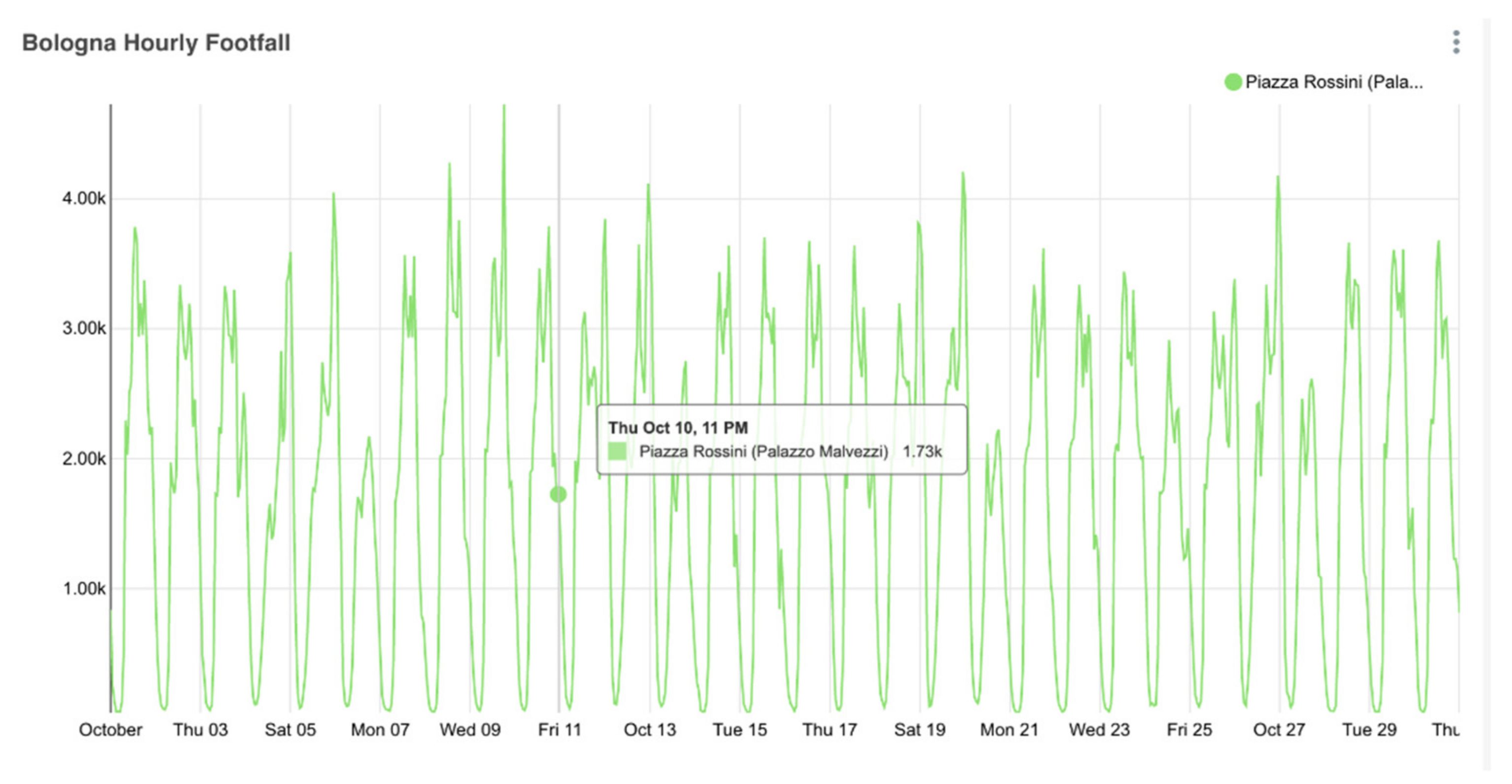

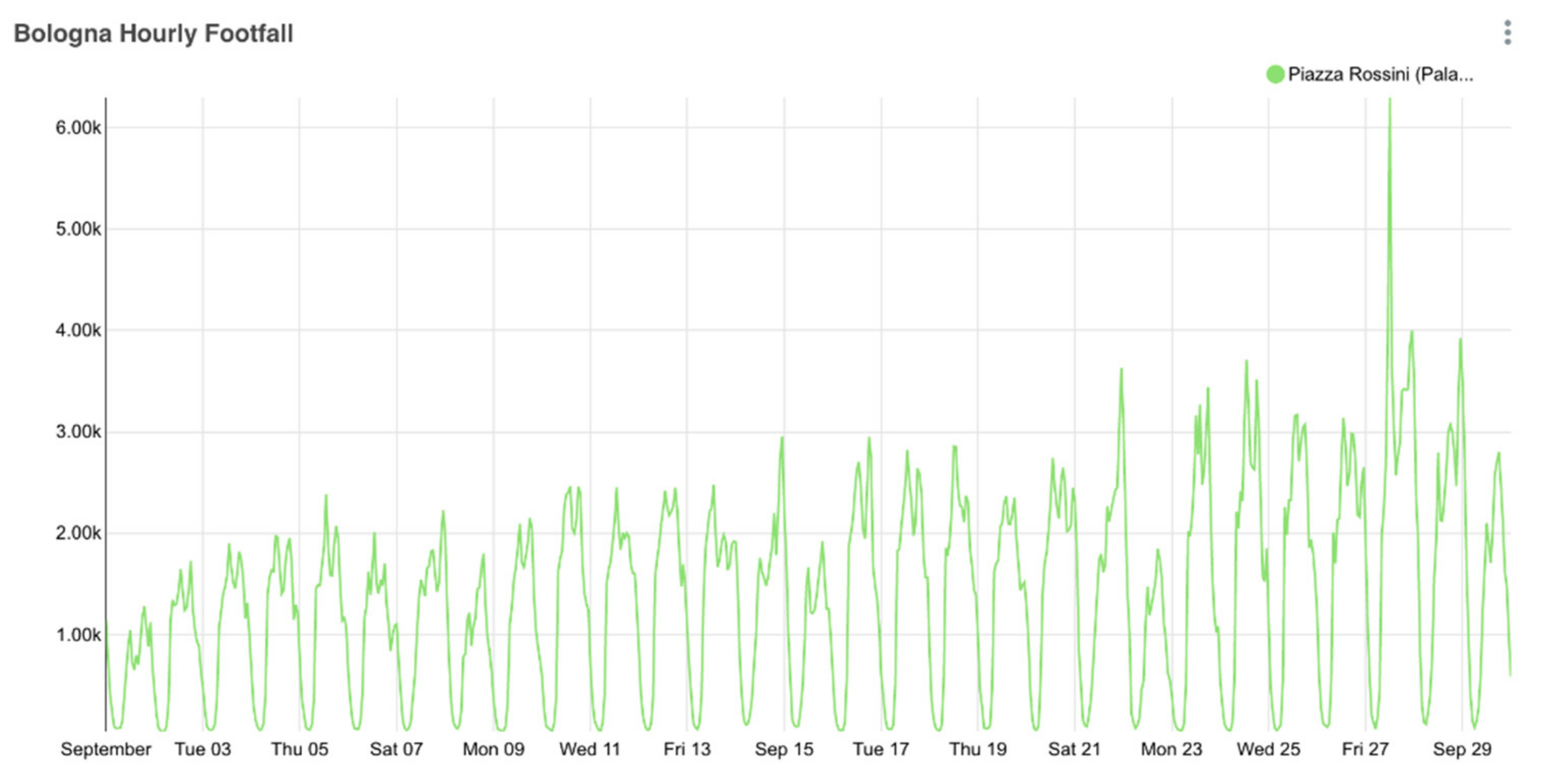

- Finally, we studied the concentration of people in the two squares along the day, to understand the most frequented hours. For this analysis we considered the entire 24 h of the day, to analyze not only the daytime but also the nighttime.

3.2.1. Selection of Timeframes

- 21–28 September 2020. In this timeframe both Piazza Scaravilli and Piazza Rossini hosted a temporary physical transformation, and, in addition, there was a series of events, under the name of “Take Care of U”. Especially located in Piazza Rossini, the events were expected to attract people to the area. It is important, in fact, to remember that Via Zamboni is a university street in the core center of the city of Bologna. Thus, it is frequented by a variety of people (students, tourists, businesspeople, residents, etc).

- 1–8 September 2020. In this timeframe, the area was characterized by the absence of events but the presence of both temporary installations in Piazza Scaravilli and Piazza Rossini.

- 4–11 October 2019. In this timeframe, the area had no events but both temporary transformation ongoing; specifically, in Piazza Rossini, there was the first pilot experience of greening named “Green Please: the meadow you don’t expect” (Figure 3), built during the “Le Cinque Piazze”.

- 23–30 September 2019. In this timeframe, in the area, there was the panel of events under the name “Le Cinque Piazze”, where both the Screensaver and the first Piazza Rossini temporary installations were built.

- 10–17 June 2019. In this timeframe, the area was characterized by the absence of the temporary installations. The area was not involved in specific events, however, in the city, there was the annual summer panel of activities, that for 2019 went under the name of “BE HERE Bologna Estate 2019”.

3.2.2. Events and Temporary Transformations in Relation with the Selected Timeframe

4. Results

4.1. Via Zamboni

- The area saw monthly a high amount of people passing in the area and going outside it or staying. Except for the COVID-19 period, the average number of people passing in the area on a monthly basis is around 1.5 million.

- There was an increase of people in the area in the months of September, October, and November 2019. It is important to note that in these timeframes, as shown in Table 3 there were some events organized in the area and the building of both Scaravilli and Rossini temporary transformations.

- The hours of a major presence in the area were the lunchtime hours (between 12:00 and 13:00), as the main timeframe during which presence was recorded. However, it was possible to record an increase of presence also during the first hours of the evening, starting from 18:00. These two observations can be explained probably with the nature of the area itself: lunchtime and aperitif time are naturally more crowded than the rest of the day when people are at work or inside the university buildings.

- It is possible that the events in June and September were able to capture people in different ways, being, for example, the September event more attractive than the June one. As explained in Table 2, however, both months were involved into the annual summer panel of events, named for 2019 “BE HERE Bologna Estate”. Nevertheless, 2019 saw the organization of a unique event in September, organized by the ROCK project, under the name Le Cinque Piazze. In this event, both Piazza Scaravilli and Piazza Rossini temporary transformations were realized.

- The creation of the temporary transformations in both Piazza Scaravilli and Piazza Rossini could have influenced, at least partially, the use of those spaces that were both car parking before. However, it is not possible to say that they are responsible for the increase of people in the area, nor the still high presence in October because we were not able to compare those data with 2020 ones, due to the COVID-19 impacts.

- Finally, it is clear that the 2020 high decrease of people in the area is due to COVID-19 and to the consequent lockdown. However, the great increase of people between the first days of September and the end of the same month shows a progressive resumption in the use of public spaces. This increasing trend is also supported by Figure 6, where it is possible to see the increasing curve from the 31st of August to the 6th of October 2020. The peaks on 12th of September and starting from the 19th to the 28th can also be related with the presence of the panel of events “Take Care of U” in the area and, especially, in Piazza Rossini.

- The sensors in Porta San Donato and the Two Towers always detected the most people. This is because these points are the limits of Via Zamboni, where people flow merges with other flows of the city. In particular, the area around Porta San Donato is particularly crowded as it is one of the ancient doors to the city center and it actually links it with the major communications avenues.

- Inside the area, Piazza Verdi is the most attended. It is, in fact, the major square where most part of the student’s life outside happens, both during the day and the evening. It is also the area where nightlife usually concentrates, often creating tension with residents.

- The sensor was not located inside the square in a sheltered position, but it could detect people passing in front of it as well. In fact, for going to Piazza Verdi, this is one of the main flow directions, meaning that the number recorder for the Piazza Rossini sensor was not necessarily catching only people inside the area but also the ones passing in front of it.

- It is also possible that the progressive re-appropriation of uncommon spaces, such as Rossini and Scaravilli, and the growing attention that is paid to that area, are effectively increasing also the use of this specific space. Personal observations regularly made in the area tend to support this aspect, even if they cannot be considered, up to now, the proof that the physical transformation of Piazza Rossini is the unique reason.

4.2. Piazza Scaravilli

- The months of June and July 2019 were almost aligned with more than 100,000 visitors, even if it is already possible to detect the progressive decrease that peaked in August 2020. These data are explainable in function of the academic year, as in Italy, August is a vacation period and in July many students leave the city. The month of July is, in fact, only an exam month, with lessons already finished. However, this time was also framed by the absence of temporary transformations in the area.

- In September and October 2019, there was a high increase in visitors. Partially these data can be justified with the restarting of lessons, but a cautious comparison with September 2020 (when lessons also restarted in person in Bologna) together with the amount of the increase in people can be probably better explained by the panel of events Le Cinque Piazze, which also built the actual physical transformation in the area. In particular, the installation was built at the end of September, thus the high presence of people in October was probably also influenced by the greening and the possibility to sit and have lunch outside.

- Table 7 shows also the confirmation that the square has been recently used with increasing time duration. The percentage of people staying from 5 to 60 min in the square is around 34% in the 21–28 September timeframe and 27% in the 1–8 September timeframe. We do not know if this can be related to the presence of the event in Piazza Rossini. Probably, in this case, it was more linked with the restarting of the academic year, which happens at the end of the month, rather than at the beginning. This year the first lessons, in fact, started on Monday 21 in several university departments.

4.3. Piazza Rossini

- At first, Piazza Rossini was more highly crowded than Piazza Scaravilli, but we already explained this fact also in relation to the geographical position of the square in a transit area and with the position of the sensor.

- As for Piazza Scaravilli, there was a high increase in the number of daily visitors starting from September 2019, in the occasion of the Le Cinque Piazze (Table 10). In this case, we also have the available data for November, showing how these three months in which the physical transformation and events were organized experienced a higher presence of people. However, as for Piazza Scaravilli, it is important to consider also that, being a university neighborhood, the amount of people tends naturally to be higher during the semesters (from September to July).

- The first temporary project for Piazza Rossini, in 2019, was successfully embraced by the citizens, with an average daily presence of around 25,000 visitors who did not just transit through the area but spent some time in the square. During the week of experimentation in September 2019, an increase in flows with an average of 20,000 daily footfall and a peak in the day of around 26,000 visitors was registered: the total weekly inflows amounted to 200,000 visitors.

5. Discussion

- It seems clear from the data shown that the presence of events can induce people to visit urban spaces more than usual.

- In the specific selected area and as the main attended events were organized for co-constructing and building the temporary installations, it is possible to argue that the physical transformation of these underused spaces has led to a major use of them.

- According to data, it is possible to say that the months following the construction of physical transformations tend to register a continuous presence of people in these areas, showing that they are really used by people.

- According to data, the two squares involved in this study are clearly used the most during the lunch break by people who must do their activities near the areas, as their duration of stay is always around 5 to 60 min. Probably, we can imagine that students and university staff, and potentially some residents, are the two major users of these spaces.

- The area is mainly frequented during the university semesters, starting from September and finishing around the end of June–July. The high decrease of attendance in August can thus be mainly reconducted to this reason. This element also confirms how the main users of these spaces are students or university staff.

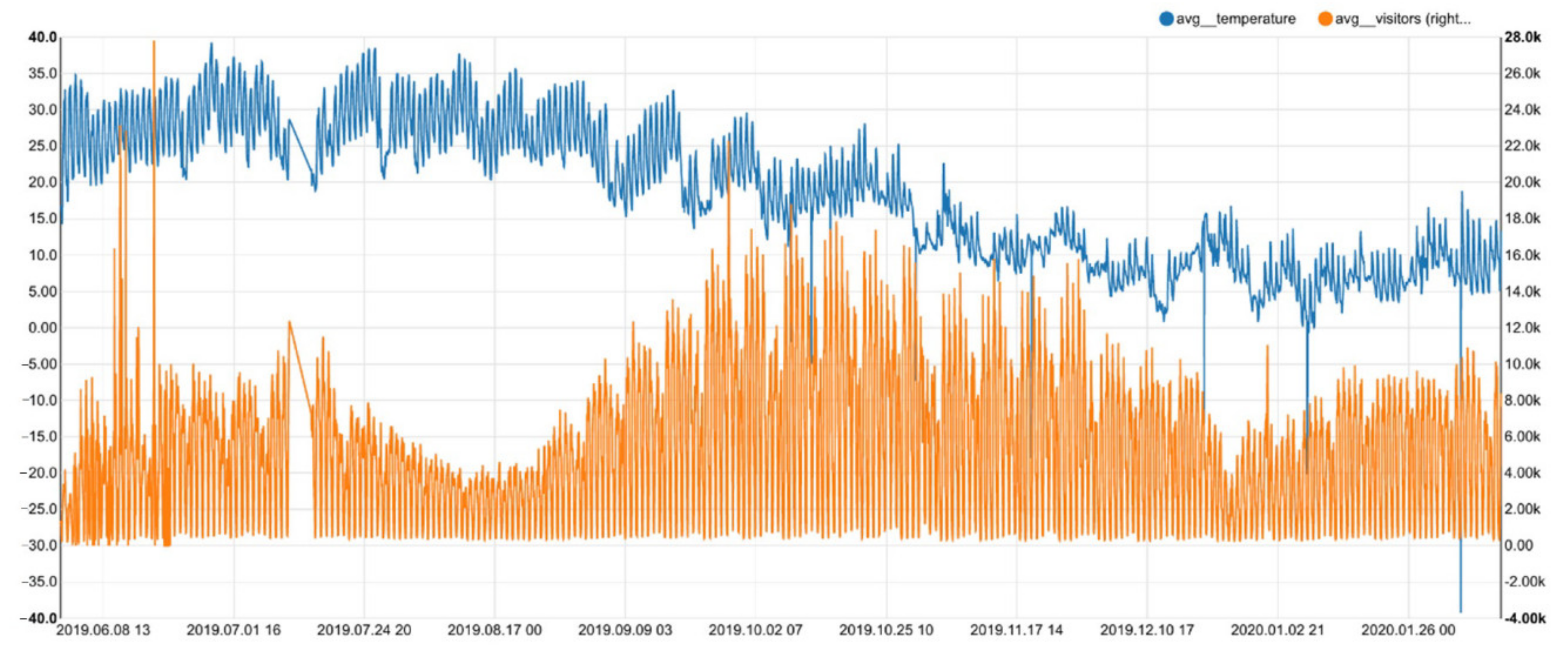

- As a final verification, Figure 19 shows the correlation between temperatures and visitors from June 2019 to February 2020. The graph shows that there was no correlation between the seasons and how people use the space, explaining also that temporary transformations in this area can be useful for enhancing the use of spaces regardless of the temperature and the season. Further publications will deepen this aspect with the aim to better understanding the relations among microclimate and people.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bibri, S.E. The anatomy of the data-driven smart sustainable city: Instrumentation, datafication, computerization and related applications. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 59. Available online: https://journalofbigdata.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40537-019-0221-4 (accessed on 2 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Shah, J.A.; Kadir, K.; Albattah, W.; Khan, F. Crowd Monitoring and Localization Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, A.; Almalki, K.J.; Choi, B.-Y.; Song, S. ICE-MoCha: Intelligent Crowd Engineering using Mobility Characterization and Analytics. Sensors 2019, 19, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalewaik, A. Smart Urbanism in Older Cities, IEEE European Technology and Engineering Management Summit, E-TEMS. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342058411_Smart_Urbanism_in_Older_Cities (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- European Commission. The Human-Centred City. Opportunities for Citizens through Research and Innovation. 2019. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5b85a079-2255-11ea-af81-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- ROCK Official Website. Available online: https://rockproject.eu (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. World Heritage Definition. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/about/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Jokilehto, J.; Originally from ICCROM Working Group “Heritage and Society”, Definition of Cultural Heritage. References to Documents in History. 2005. Available online: http://cif.icomos.org/pdf_docs/Documents%20on%20line/Heritage%20definitions.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Directorate B—Open Innovation and Open Science, Unit B.6—Open and Inclusive Societies, Innovation in Cultural Heritage Research. For an Integrated European Research Policy; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Directorate I—Climate Action and Resource Efficiency, Unit I.3, Sustainable Management of Natural Resources, Innovative Solutions for Cultural Heritage from EU Funded R & I Projects; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elisei, P.; Draghia, M.; Dane, G.; Onesciuc, N. Crowd Flow Analysis for Measuring the Impact of Urban Transformation Actions in City’s Heritage Areas; Schrenk, M., Popovich, V., Zeile, P., Elisei, P., Beyer, C., Ryser, J., Reicher, C., Çelik, C., Eds.; The Information Society Geo Multimedia: Aachen, Germany, 2020; pp. 1065–1079. Available online: https://research.tue.nl/en/publications/crowd-flow-analysis-for-measuring-the-impact-of-urban-transformat (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Vallianatos, M. Uncovering the Early History of «Big Data» and the «Smart City» in Los Angeles. Boom California. 2015. Available online: https://boomcalifornia.com/2015/06/16/uncovering-the-early-history-of-big-data-and-the-smart-city-in-la/ (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C. Smart Cities: Is it just a fad? Sci. Reg. 2018, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Komninos, N.; Mora, L. Exploring the big picture of smart city research. Sci. Reg. 2018, 17, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger, S.O.M. Smarter and Greener. A technological Path for Urban Complexity; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.; Dassen, T. Visualizing the Challenge for 21st Century Urbanism; PBL Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. World Cities Report 2020, The Value of Sustainable Urbanization. 2020. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/wcr/ (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Bonomi, A.; Masiero, R. Dalla Smart City Alla Smart Land; Marsilio editore: Venezia, Italy, 2014; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, T. Beyond Smart Cities. How Cities Network, Learn and Innovate; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart Cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudel, M.; Ratti, C. Dimensions of the Future City. In Cities in the 21st Century; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’O, G. Smart City. La Rivoluzione Intelligente Delle Città; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dameri, R.P.; Cocchia, A. Smart City and Digital City: Twenty Years of Terminology Evolution. In X Conference of the Italian Chapter of AIS; ITAIS: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Deakin, M. Creating Smart-er Cities; Informa UK Limited: Colchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Publication Office of the European Commission. The Human Centered City, 2019 Report. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b94ce36e-c550-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Directorate-General for Internal Policies-European Parliament. Mapping the Smart Cities in the EU. 2014. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2014/507480/IPOL-ITRE_ET(2014)507480_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Green, B. The Smart Enough City: Putting Technology in Its Place to Reclaim Our Urban Future; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Giffinger, R.; Fertner, C.; Kramar, H.; Meijers, E. City-Ranking of European Medium-Sized Cities. Cent. Reg. Sci. Vienna UT. 2007. Available online: http://www.smart-cities.eu/download/smart_cities_final_report.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Giffinger, R.; Haindlmaier, G.; Strohmayer, F. PLEEC. Planning for Energy Efficient Cities. Typology of Cities. 2014. Available online: https://globe.ku.dk/research/evogenomics/gopalakrishnan-group/?pure=en%2Fpublications%2Fnote(89f1d174-4c73-4818-a22f-40abad28f180)%2Fexport.html (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Gaspari, J.; Boulanger, S.; Antonini, E. Multi-layered design strategies to adopt smart districts as urban regeneration enablers. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2017, 12, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, S.; Roversi, R. Carte di Identità per Quartieri Multi-Layer. Strumenti per il Design Della Città Smart; Lauria, M., Mussinelli, E., Tucci, F., Eds.; La PROduzione del PROgetto; Santarcangelo di Romagna; Maggioli Editore: Santarcangelo, Italy, 2019; pp. 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate General for Research and Innovation. The Human-Centred City. Opportunities for Citizens through Research and Innovation. Report of the High-Level Expert Group on Innovating Cities. 2019. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b94ce36e-c550-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Architects’ Council of Europe. EFFORT; ERIH.; Europa Nostra and FRH, Leeuwarden Declaration. Adaptive Re-Use of the Built Heritage: Preserving and Enhancing the Values of Our Built Heritage for Future Generations (Leeuwarden: 23 November 2018). Available online: https://www.ace-cae.eu/uploads/tx_jidocumentsview/LEEUWARDEN_STATEMENT_FINAL_EN-NEW.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Camocini, B. Adapting Reuse. Strategie di Conversione d’uso Degli Interni e di Rinnovamento Urbano; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Musso, F.S. Permanencies and Disappearances. In Conservation-Adaptation. Keeping Alive the Spirit of the Place. Adaptive Reuse of Heritage with Symbolic Value; Fiorani, D., Kealy, L., Musso, F.S., Eds.; European Association for Architectural Education (EAAE): Hasselt, Belgium, 2017; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Sonkoly, G.; Vahtikari, T. Innovation in Cultural Heritage Research. In For an Integrated European Research Policy; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1dd62bd1-2216-11e8-ac73-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Boeri, A.; Gianfrate, V.; Longo, D.; Roversi, R. Cultural heritage-led initiatives for urban regeneration. In Pilot Implementation Actions in Bologna Public Spaces; Marata, A., Galdini, R., Eds.; Diverse City: Swanage, UK, 2019; pp. 463–472. Available online: http://www.cittacreative.eu/diverse-city/ (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Lerner, J. Urban Acupuncture; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, D.; Gianfrate, V. Urban Micro-Design. Tecnologie Integrate, Adattabilità e Qualità Degli Spazi Pubblici; Franco Angeli-Ricerche di Tecnologia dell’Architettura: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Iaconesi, S.; Persico, O. Digital Urban Acupuncture. In Digital Urban Acupuncture; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, R.; Boeri, A.; Longo, D.; Gianfrate, V.; Boulanger, S.O.; Mariotti, C. ICTs for Accessing, Understanding and Safeguarding Cultural Heritage: The Experience of INCEPTION and ROCK H2020 Projects. Int. J. Arch. Herit. 2019, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasnesis, P.; Tatlas, N.-A.; Mitilineos, S.A.; Patrikakis, C.Z.; Potirakis, S.M. Acoustic Sensor Data Flow for Cultural Heritage Monitoring and Safeguarding. Sensors 2019, 19, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasca, F.; Verticchio, E.; Caratelli, A.; Bertolin, C.; Camuffo, D.; Siani, A.M. A Comprehensive Study of the Microclimate-Induced Conservation Risks in Hypogeal Sites: The Mithraeum of the Baths of Caracalla (Rome). Sensors 2020, 20, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STORM Official Website. Available online: http://www.storm-project.eu/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Kostakos, V.; Rogstadius, J.; Ferreira, D.; Hosio, S.; Goncalves, J. Human Sensors. Participatory Sensing, Opinions and Collective Awareness. Understanding Complex, Systems. 2017. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-25658-0_4#citeas (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology; Cultural Heritage: Digitization, Online Accessibility and Digital Preservation. Consolidated Progress Report on the Implementation of Commission Recommendations 2015–2017, Luxembourg, 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/european-commission-report-cultural-heritage-digitisation-online-accessibility-and-digital (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Agapiou, A.; Lysandrou, V.; Alexakis, D.D.; Themistocleous, K.; Cuca, B.; Argyriou, A.; Sarris, A.; Hadjimitsis, D.G. Cultural heritage management and monitoring using remote sensing data and GIS: The case study of Paphos area, Cyprus. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 54, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A.; Ateya, A.A.; Amelyanovich, A.; Shpakov, M.; Darya, P.; Makolkina, M. Enabled System for Cultural Heritage Monitoring and Preservation. In Internet of Things, Smart Spaces, and Next Generation Networks and Systems. NEW2AN 2018, SMART 2018; Galinina, O., Andreev, S., Balandin, S., Koucheryavy, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.S. The key of sensor network applied in cultural heritage protection measurement and control technology. Sci. Cons. Archaeol. 2011, 23, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cardani, G.; Angjeliu, G. Integrated Use of Measurements for the Structural Diagnosis in Historical Vaulted Buildings. Sensors 2020, 20, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbota, H.; Mitchell, J.E.; Odlyha, M.; Strlič, M.; John, E.M. Remote Assessment of Cultural Heritage Environments with Wireless Sensor Array Networks. Sensors 2014, 14, 8779–8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti‡, N.; Capitani, D.; Di Tullio, V. Applications of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Sensors to Cultural Heritage. Sensors 2014, 14, 6977–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecocci, A.; Abrardo, A. Monitoring Architectural Heritage by Wireless Sensors Networks: San Gimignano—A Case Study. Sensors 2014, 14, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibri, S.E. On the sustainability of smart and smarter cities in the era of big data: An interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary literature review. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Fusion Research Centre (DFRC) Official Website. Available online: http://www.dfrc.ch/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Gianfrate, V.; Djalali, A.; Turillazzi, B.; Boulanger, S.O.; Massari, M. Research-Action-Research towards a Circular Urban System for Multi-level Regeneration in Historical Cities: The Case of Bologna. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2020, 15, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvallis Website. Available online: http://www.corvallis.it/Apps/WebObjects/Corvallis.woa/wa/viewSection?id=1962&lang=eng (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- ROCK Open Data Platform. Available online: https://opendata.rockproject.eu/rock/#/home (accessed on 14 October 2020).

| <5 min | People passing in the area without stopping. These are people that use the street as a means for transit from one side to another |

| 5 to 20 min | People stopping for short time in the area, for short purposes. These can be variable, e.g., from short activities (like taking a coffee), to the curiosity to see something happening. |

| 20 to 60 min | People stopping for medium time range in the area for longer purposes, such as having lunch, participating in some activities, going to the library or one of the bars and pubs present, etc. |

| 60 to 120 min | People stopping for a time range medium-long in the area. These people usually are doing some long activities, such as attending a conference or a lesson, enjoying time in a café or in a restaurant, participating in longer activities in the area. |

| 2 to 3 h | People stopping for a long time in the area, for example for attending a longer lesson or conference or event in the theatre or participating in quite long events; or just doing shorter activities in different spots inside the same area. |

| More than 3 h | People stopping for a very long time. Usually people that are resident, or work in the area, or they have longer classes or multiple classes in the same area, or they are spending their leisure time in the area for long time. |

| Date | Hours | Event Title | Ref. Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 August–30 September 2020 | Take Care of U | Piazza Rossini | |

| 29 September 2020 | From 17:30 | Presentation for the ROCK App “Bo for All” | Piazza Rossini |

| 26 September 2020 | 9:30–17:30 | Artistic marathon for Patrick Zaki | Piazza Rossini |

| 26 September 2020 + 8 September 2020 | From 17:30 | Take Care of U: “Ospiti alla Corte di Giovanni II Bentivoglio: una giornata tipo del 1492” | Piazza Rossini |

| From 18:00 | Take Care of U readings/monologues with invited speakers (24 September 2020; 23 September 2020; 17 September 2020; 16 September 2020; 10 September 2020; 9 September 2020; 3 September 2020; 2 September 2020; 27 August 2020; 20 August 2020) | Piazza Rossini | |

| 25 September–1 October 2020 | 9.00–18.00 | Installation and co-construction of “Green Please, il prato che non ti aspetti” | |

| 22 September 2020 + 25 August 2020 | From 18:00 | Take Care of U: “Amori, congiure e delitti: le famiglie nobili in Strà San Donato” | Piazza Rossini |

| 1 September 2020 + 18 August 2020 | From 18:00 | Take Care of U: “A passeggio con Rossini: personaggi illustri in Strada San Donato” | Piazza Rossini |

| 19 August 2020 | From 18:00 | Take Care of U: “Girovagando in via Zamboni osserviamo i palazzi, i portici, le piazze” | Piazza Rossini |

| 15 June–2 July 2020 | Construction of Green Please | Piazza Rossini | |

| 23–28 September 2020 | Le Cinque Piazze | Via Zamboni | |

| 25–28 September 2019 | 9.00–18.00 | Le Cinque Piazze: First installation of Green Please | Piazza Rossini |

| 23–28 September 2019 | 9.00–18.00 | Le Cinque Piazze: Screensaver installation | Piazza Scaravilli |

| 23–28 September 2019 | 9.00–18.00 | Le Cinque Piazze: UGarden | Piazza Verdi |

| 23–28 September 2019 | 9.00–18.00 | Le Cinque Piazze: Mediterranean Design Weeks | Piazza Verdi |

| 13 May–30 September 2019 | BE HERE—Bologna summer panel of events 2019 | City center | |

| 28 August 2019 | From 20:30 | Performance teatrale: “Figli di una cavalcata” | Piazza Verdi |

| 8 July 2019 | 17:00–20:00 | Pianeti solitari: mappatura esperienziale | Via Zamboni |

| 7 July 2019 | 15:00–17:00 | Pianeti solitari: mappatura esperienziale | Via Zamboni |

| 18 June 2019 | From 17:00 | Carotaggi: passeggiata insolita | Via Zamboni |

| 14 October 2018 | From 17:00 | Concerto per 5 Pianoforti | Piazza Scaravilli |

| 6 July 2018 | From 18:00 | SLAB co-construction opening | Piazza Scaravilli |

| 2–6 July 2018 | 9.00–18.00 | Co-construction workshop SLAB | Piazza Scaravilli |

| 11–16 June 2017 | 9.00–18.00 | Co-construction workshop Malerbe #2 | Piazza Scaravilli |

| Timeframe | Sum Daily Visitors | Average Daily Visitors | Hours of Major Presence (Central European Time; CET) | Presence of Transformations // Major Events in the Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 June | 1,628,414 | 54,280 | 12:00–13:00 | No // “Bologna Estate” set of events spread in the city center—no specific event in the area |

| 19 July | 1,797,050 | 57,969 | 12:00–13:00 (with slight difference with 17:00-19:00) | Yes // “Bologna Estate” set of events spread in the city center—no specific event in the area |

| 19 August | 1,111,597 | 35,858 | 12:00–13:00 and 18:00–19:00 | Yes // “Bologna Estate” set of events spread in the city center—performance in Piazza Verdi |

| 19 September | 2,327,649 | 77,588 | 12:00–13:00 | Yes // Yes (at the end of the month “Le Cinque Piazze” in the selected areas) |

| 19 October | 2,943,887 | 94,964 | 13:00 | Yes (both areas) // No |

| 19 November | 2,386,907 | 79,564 | 13:00 | Yes // No |

| 19 December | 1,749,274 | 56,428 | 13:00 (with slight difference with 16:00–18:00) | Yes // No |

| 20 January | 1,730,557 | 55,824 | 12:00–14:00 and 18:00 | Yes (COVID-19 emergency in Italy) |

| 20 February | 1,735,890 | 59,858 | 12:00–13:00 and 18:00 | Yes (COVID-19 emergency in Italy) |

| 20 March–June | No data | No data | No data | Yes (COVID-19 lockdown in Italy) |

| July (from the 17th) | 401,083 | 26,739 | 18:00–20:00 | Yes (slow re-opening from lockdown) |

| 20 August | 620,328 | 20,011 | 18:00–20:00 | Yes // Yes (at the end of the month “Take Care of U” in Piazza Rossini) |

| 20 September | 1,390,323 | 46,344 | 12:00–13:00 and 18:00–19:00 | Yes (both areas) // Yes (“Take Care of U” in Piazza Rossini) |

| Timeframe (8 Days) | Unique Visitors (Sum) | Events | Transformation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21–28 September 2020 | 431,516 | yes | yes |

| 1–8 September 2020 | 293,715 | no | yes |

| 4–11 October 2019 | 744,209 | no | yes |

| 23–30 September 2019 | 765,265 | yes | yes |

| 10–17 June 2019 | 448,059 | yes | no |

| Timeframe (8 Days) | <1 min | 1–5 min | 5–20 min | 20–60 min | 60–120 min | 2–3 h | >3 h | Events | Transformation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21–28 September 2020 | 29% | 28% | 20% | 15% | 5% | 1% | 2% | yes | yes |

| 1–8 September 2020 | 30% | 28% | 19% | 14% | 5% | 2% | 2% | no | yes |

| 4–11 October 2019 | 31% | 27% | 20% | 13% | 5% | 1% | 2% | no | yes |

| 23–30 September 2019 | 23% | 27% | 24% | 18% | 6% | 1% | 1% | yes | yes |

| 10–17 June 2019 | 17% | 21% | 32% | 21% | 5% | 2% | 2% | yes | no |

| Timeframe | Av. Daily Visitors (Total) | Sum Daily Visitors (Scaravilli) | Av. Daily Visitors (Scaravilli) | Main Ref. Hours |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 June | 54,280 | 181,555 | 6052 | 13:00 |

| 19 July | 57,969 | 101,884 | 3287 | 12:00–13:00 |

| 19 August | 35,858 | 85,597 | 2761 | 12:00–13:00 |

| 19 September | 77,588 | 354,739 | 11,825 | 12:00–13:00 |

| 19 October | 94,964 | 508,214 | 16,394 | 13:00 |

| 19 November | 79,564 | Sensor offline | Sensor offline | Sensor offline |

| 19 December | 56,428 | Sensor offline | Sensor offline | Sensor offline |

| 20 January | 55,824 | Sensor offline | Sensor offline | Sensor offline |

| 20 February | 59,858 | Sensor offline | Sensor offline | Sensor offline |

| 20 March–June | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| July (from the 17th) | 26,739 | Sensor offline | Sensor offline | Sensor offline |

| 20 August | 20,011 | 47,836 | 1543 | 13:00 + 18:00 |

| 20 September | 46,344 | 152,825 | 5094 | 13:00 + 18:00 |

| Timeframe (8 Days) | <1 min | 1–5 min | 5–20 min | 20–60 min | 60–120 min | 2–3 h | >3 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21–28 September 2020 | 24% | 24% | 19% | 15% | 7% | 3% | 8% |

| 1–8 September 2020 | 36% | 33% | 16% | 11% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| Timeframe | Av. Daily Visitors (Total) | Sum Daily Visitors (Rossini) | Av. Daily Visitors (Rossini) | Main Ref. Hours |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 June | 54,280 | 366,429 | 12,214 | 12–13/18–22 |

| 19 July | 57,969 | 447,033 | 14,420 | 12–13/18–19 |

| 19 August | 35,858 | 241,676 | 7796 | 12–13/18–22 |

| 19 September | 77,588 | 618,953 | 20,632 | 12–13/18–19 |

| 19 October | 94,964 | 809,458 | 26,112 | 18:00 |

| 19 November | 79,564 | 687,372 | 22,912 | 13:00 |

| 19 December | 56,428 | 474,262 | 15,299 | 13:00 |

| 20 January | 55,824 | 437,087 | 14,111 | 12–13/18–19 |

| 20 February | 59,858 | 473,095 | 16,314 | 18:00 |

| 20 March–June | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| July (from the 17th) | 26,739 | 108,403 | 7227 | 22:00 |

| 20 August | 20,011 | 159,084 | 5132 | 12–13/18–19 |

| September 20 | 46,344 | 362,237 | 12,075 | 12–13/18–19 |

| Timeframe (8 Days) | <1 min | 1–5 min | 5–20 min | 20–60 min | 60–120 min | 2–3 h | >3 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21–28 September 2020 | 34% | 34% | 18% | 11% | 2% | 0% | 1% |

| 1–8 September 2020 | 32% | 34% | 18% | 12% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| Timeframe | Av. Daily Visitors (Total) | Av. Daily Visitors (Verdi) | Av. Daily Visitors (Rossini) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 June | 54,280 | 14,320 | 12,214 | 2106 |

| 19 July | 57,969 | 16,364 | 14,420 | 1944 |

| 19 August | 35,858 | 8,245 | 7,796 | 449 |

| 19 September | 77,588 | 23,354 | 20,632 | 2722 |

| 19 October | 94,964 | 30,660 | 26,112 | 4548 |

| 19 November | 79,564 | 26,760 | 22,912 | 3848 |

| 19 December | 56,428 | 17,450 | 15,299 | 2151 |

| 20 January | 55,824 | 15,999 | 14,111 | 1888 |

| 20 February | 59,858 | 18,631 | 16,314 | 2317 |

| 20 March–June | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| July (from the 17th) | 26,739 | 8530 | 7227 | 1303 |

| 20 August | 20,011 | 5611 | 5132 | 479 |

| 20 September | 46,344 | 12,075 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boulanger, S.O.M.; Longo, D.; Roversi, R. Data Evidence-Based Transformative Actions in Historic Urban Context—The Bologna University Area Case Study. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 1448-1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3040069

Boulanger SOM, Longo D, Roversi R. Data Evidence-Based Transformative Actions in Historic Urban Context—The Bologna University Area Case Study. Smart Cities. 2020; 3(4):1448-1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoulanger, Saveria Olga Murielle, Danila Longo, and Rossella Roversi. 2020. "Data Evidence-Based Transformative Actions in Historic Urban Context—The Bologna University Area Case Study" Smart Cities 3, no. 4: 1448-1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3040069

APA StyleBoulanger, S. O. M., Longo, D., & Roversi, R. (2020). Data Evidence-Based Transformative Actions in Historic Urban Context—The Bologna University Area Case Study. Smart Cities, 3(4), 1448-1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3040069