1. Introduction

The rapid development of nanotechnology and biotechnology has enabled the emergence of nanoscale communication systems inspired by biological processes. Among the most promising approaches is molecular communication (MC), a paradigm where information is transmitted using chemical signals—mimicking natural biological signaling mechanisms such as hormone delivery, neurotransmission, or immune responses.

MC plays a key role in the implementation of Internet of BioNanoThings (IoBNT) and Body Area Nanonetworks (BANNs), where interconnected nanomachines coordinate for tasks such as health monitoring, drug delivery, and diagnostics and lastly theranostics [

1,

2,

3].

Unlike conventional wireless technologies, which face severe limitations at the nanoscale due to antenna size constraints and energy requirements, MC leverages biochemical signals as information carriers, inspired by natural processes such as cellular signaling and pheromone-based communication. MC, which is naturally occurring in biological organisms, offers a low-power, bio-compatible solution for short-range in-body communications [

4]. It relies on chemical signals as carriers of information, offering inherent biocompatibility and low energy requirements that make it suitable for in-body or environmentally sensitive contexts. To move from theoretical models to practical realizations, experimental testbeds have become an indispensable step, providing controlled platforms where communication schemes, detection strategies, and channel dynamics can be systematically studied. Early macro-scale prototypes, such as the tabletop chemical messaging system of Farsad et al. [

5], demonstrated the feasibility of encoding digital messages in molecular form, while fluidic platforms like the cardiovascular-inspired setup of Pan et al. [

6] highlighted how molecular transport in flowing environments can be emulated. These pioneering efforts laid the foundation for translating abstract communication models into tangible experimental systems.

During the past decade, extensive theoretical work has been devoted to characterizing molecular communication channels, developing modulation schemes, and analyzing the fundamental limits of achievable rates [

7,

8,

9]. In particular, diffusion-based MC has attracted significant attention, as it closely reflects naturally occurring mechanisms of information transfer. However, despite the breadth of theoretical and simulation-based studies, experimental demonstrations remain limited due to in vitro and in vivo complexity, need for specialized infrastructure and personnel, and cost. Existing prototypes, such as tabletop molecular communication systems, have provided valuable insights but are often restricted to unidirectional transmission or neglect the closed system characteristics [

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, the nonlinear dynamics of real channels, including intersymbol interference (ISI) and signal saturation, are typically not captured in idealized models, highlighting the need for experimental validation.

Recent efforts in building proof-of-concept platforms, from spray-based macroscopic systems to microfluidic testbeds as we analyze in the next section, have underscored the importance of bridging the gap between theoretical modeling and physical implementation. These systems have demonstrated the feasibility of molecular communication in practice but also revealed key challenges such as slow diffusion, channel memory, and limited data rates. Channel saturation caused by molecule accumulation constitutes a fundamental bottleneck, as it prevents sustained bidirectional information transfer in the absence of appropriate clearance mechanisms.

In this work, we present an enhanced closed-loop molecular communication system with a responsive receiver that can not only decode messages but also send acknowledgment signals or responses, back to the transmitter. This bidirectional communication setup enables two-way communication, allowing basic message exchange in both directions through the same physical channel. The system does not alter or regulate the intensity of transmitted signals, but it supports bidirectional signaling based on physical propagation mechanisms like diffusion and advection. Our system builds on the theoretical framework of diffusion-based communication governed by Fick’s laws [

13], while also incorporating advection to reflect externally driven flow in the medium, such as that observed in circulatory systems. The transmitter releases into the medium the diffusive substance resembling molecular pulses corresponding to encoded binary data. These pulses are transported through the medium and sensed by the receiver via a color sensor. Upon message reception, the receiver initiates a reverse communication process by emitting its own molecular signal. This structure enables the implementation of simple acknowledgment-based communication, which is fundamental to more advanced interaction schemes in nanonetworks [

14].

To validate the feasibility of this system, we conducted a series of experiments under varying conditions of rate. The results confirm that the proposed design can sustain reliable two-way communication in a biologically inspired environment and provide insights into how such systems may be adapted for use in biomedical nanonetworks.

The contributions of this paper are threefold:

We expand the existing cardiovascular-inspired molecular communication testbed presented in the literature into a unique bi-directional communication system.

We develop a responsive receiver module capable of generating molecular responses and detecting incoming signals based on a two threshold-based mechanism. Additionally, we propose and implement an experimental detection algorithm based on a percentage signal drop, where a pulse is considered successfully received if the measured intensity decreases by at least 35% after peak detection. This alternative strategy, validated through experiments, proved particularly useful in confirming message reception under varying flow conditions.

We evaluate the performance, latency, and operational reliability of the proposed two-way molecular communication system simulating different physiological environments. Our experiments assess how different flow rates affect signal propagation, reception accuracy, and overall system feasibility in biologically inspired environments.

These findings suggest that the proposed architecture, based on inexpensive electronics and components, serves as a practical step toward the development of responsive, two-way molecular communication systems, enabling bidirectional information exchange under biologically relevant conditions and contributing to the broader design of adaptive nanonetwork protocols [

5].

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews prior work in molecular communication and experimental testbeds relevant to our system.

Section 3 presents the architecture and components of the proposed tabletop platform.

Section 4 details the signal modulation scheme, detection algorithms and the mathematical modeling of advection-diffusion dynamics.

Section 5 describes the bidirectional communication protocol implemented in our system.

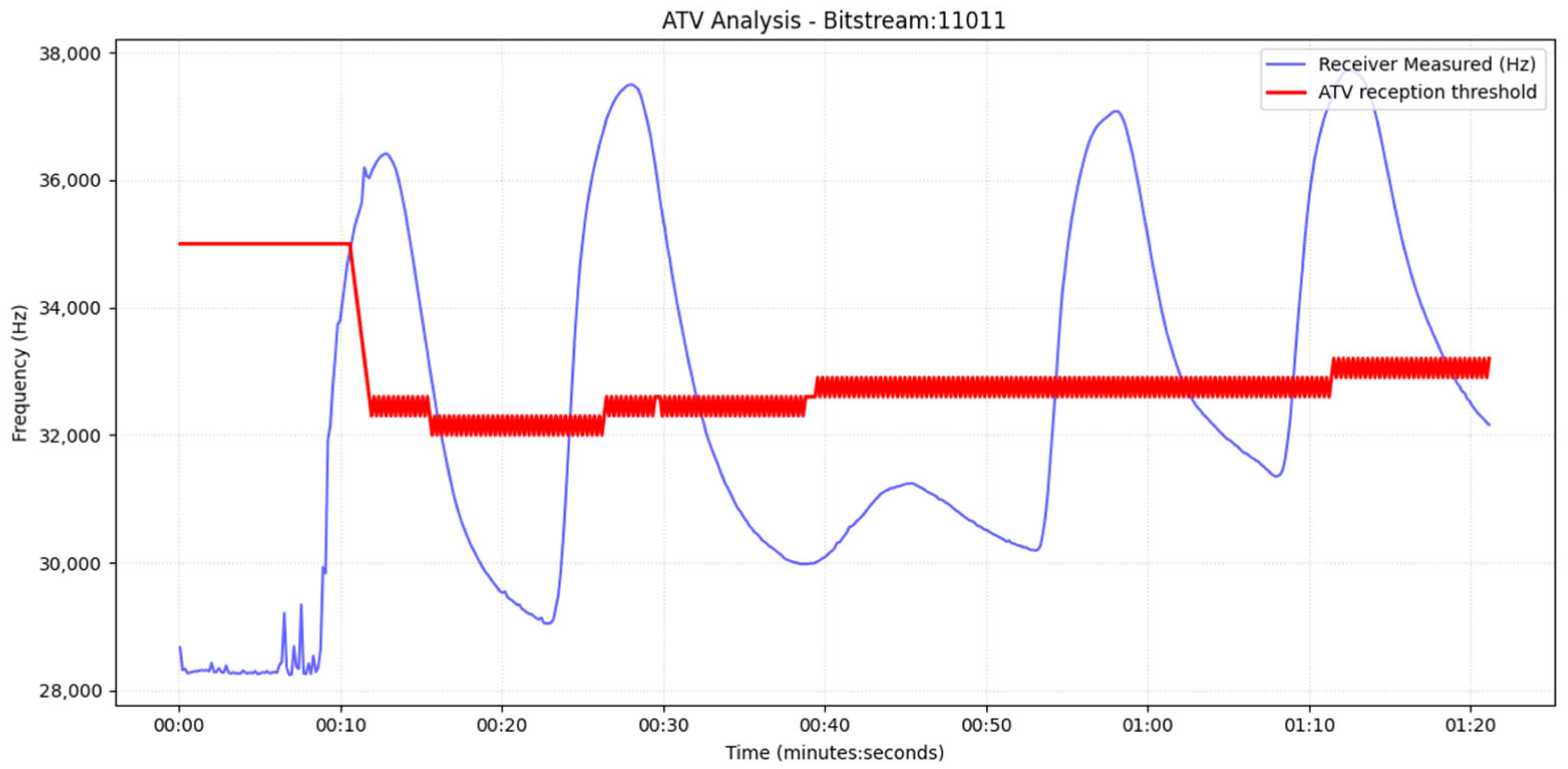

Section 6 reports the experimental results under multiple operating conditions along with statistical analysis of the results. Additionally, in this section we present the application of the Adaptive Threshold Variation (ATV) algorithm to the physical system, while

Section 7 discusses key insights, limitations and implications for future designs. Finally,

Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Recent research in MC has explored its potential for biomedical applications such as intra-body sensing, targeted therapy, and real-time diagnostics. One of the main challenges remains the design of systems capable of reliable and efficient message transmission and reception within the complex and variable conditions of biological environments.

The conceptual roots of MC can be traced to early work on molecular information processing and molecular computing by Michael Conrad. In the early 1970s, Conrad analyzed information processing in molecular systems and emphasized enzyme-catalyzed reactions as natural information-processing elements at the molecular scale [

15]. He later formulated design principles for molecular computers based on protein enzymes and reaction–diffusion processes [

16] and introduced the broader molecular computing paradigm [

17], providing important conceptual groundwork for contemporary MC and IoBNT research.

In the same manner, initial progress in MC via diffusion was rooted in theoretical modeling and mathematical analysis of Crank’s work on diffusion [

18], which laid the foundation for subsequent studies, modeling molecular propagation under Fickian or advection-diffusion dynamics. Farsad et al. [

14] provided a unified overview of MC channel types, modulation schemes, and receiver architectures, while Kuran et al. [

19] examined modulation techniques suited for diffusion-based nanonetworks. Simulation-based studies further expanded these models by incorporating environmental variability, flow conditions, and reaction–diffusion processes [

13,

20], offering a broader understanding of signal behavior under more realistic biological constraints. Complementary analyses of diffusion channels, including impulse response and pulse-based modulation performance, were presented by Liatser et al. [

21].

While theoretical models are well-developed, real-world experimental systems remain limited in number and scope. As emphasized by Hamidović et al. [

9], the integration of microfluidic technologies has been instrumental in moving MC from abstract models toward physical testbeds that enable controlled experimentation with molecular signals. Microfluidic systems allow for precise control of flow, pressure, and substance concentration, making them ideal environments for validating diffusion and advection-based propagation models.

Early macro-scale prototypes, such as the tabletop chemical messaging system of Farsad et al. [

5] and the cardiovascular-inspired fluidic platform of Pan et al. [

6], successfully demonstrated the feasibility of encoding and transmitting information via molecules. However, these pioneering systems were predominantly unidirectional, with passive receivers incapable of providing feedback.

Recent advances have shifted attention toward improving realism, biocompatibility, and accessibility of MC testbeds. Microfluidic systems, reviewed extensively by Hamidović et al. [

9], now provide precise control of signal release and transport, enabling the exploration of advanced modulation schemes in environments closer to physiological conditions. To align with biomedical applications, Bartunik et al. [

22] proposed a fully biocompatible testbed employing superparamagnetic nanoparticles and magnetic detection, bridging experimental work with clinically relevant technologies. At the same time, practical concerns have driven the development of low-cost platforms, such as the adhesive-tape microfluidic testbed by Albay et al. [

23], which integrates electrochemical detection and multi-level modulation in a highly accessible format. Despite these significant steps forward, most existing systems remain unidirectional, with receivers acting passively and unable to provide feedback. The absence of responsive and bidirectional communication mechanisms limits the ability to replicate interactive processes found in nature, such as feedback loops and adaptive signaling. Addressing this gap requires the design of experimental platforms capable of supporting two-way communication, thus bringing MC testbeds closer to the vision of functional IoBNT nanonetworks [

24].

A major breakthrough was presented by Koo et al. [

7], who developed a 2 × 2 macro-scale molecular MIMO system featuring multiple transmitters and receivers. Their system uses distinct chemical sprays and sensors in a tabletop setup to simulate spatial parallelism and bidirectional transmission. This architecture enables simultaneous multi-stream signaling, accounts for ISI and inter-link interference, and demonstrates practical detection algorithms like adaptive thresholding and zero-forcing. Importantly, their physical prototype achieves nearly double the throughput compared to SISO systems and confirms the feasibility of bidirectional molecular signaling using coordinated emission and reception strategies.

A notable recent work by Brand et al. [

25] introduces a fluid-based molecular communication testbed that operates in a closed-loop configuration, emulating environments such as the human cardiovascular system. Instead of injecting new molecules, the system employs media modulation by optically switching the state of green fluorescent protein Dreiklang (GFPD) molecules already present in the medium. This approach enables multiple reuses of signaling molecules and external control of transmission, reception, and erasure processes. Due to the long experiment durations and the closed-loop design, the authors identify and characterize new forms of ISI, including inter-loop, offset, and permanent ISI, and propose mitigation strategies.

Wietfeld et al. [

26] present a novel flow-based molecular communication testbed that enables real-time multi-molecule (MUMO) transmission using spectral sensing. The system uses colored inks (cyan, magenta, yellow) as distinct signaling molecules and employs a non-invasive spectral sensor at the receiver to estimate the concentration of each molecule type via a linear estimator based on the Beer–Lambert law. Extensive channel impulse response (CIR) measurements are conducted, showing that MUMO transmission only slightly impacts signal shape compared to single-molecule transmission. The testbed achieves data rates up to 3 bps with near-error-free communication, using a simple difference detector.

In parallel, research has also focused on implantable and bio-hybrid MC systems. Koo et al. [

10] proposed a deep learning-based nano-communication platform with glucose-sensitive implantable chips, highlighting the integration of biosensing, machine intelligence, and nano transceiver architectures. This line of work demonstrates the importance of adaptive detection strategies and learning-based approaches to overcome sensor and channel uncertainties in practical nanonetworks.

To clearly contextualize the contribution of our work within the landscape of existing experimental platforms, we provide a comparative summary in

Table 1. The table contrasts key characteristics, such as communication direction, channel type, and detection method, across several representative systems.

As illustrated in

Table 1, our system occupies a unique position. Unlike the MIMO approach of Koo et al. [

7] which uses parallel channels, we achieve bidirectionality through role switching of two nodes within a single physical channel. Furthermore, while Brand et al. [

25] also employ a closed loop, their focus is on reusing a fixed set of molecules via optical switching, whereas our platform studies the fundamental effects of molecule accumulation and saturation resulting from sequential injections in a closed system, a critical phenomenon for practical IoBNT applications.

In this work, we developed a closed-loop molecular communication platform capable of bidirectional signaling through a fluidic channel based on this single-channel role-switching paradigm. Our system integrates diffusion- and advection-based transport, real-time sensing, and a responsive receiver capable of role switching. In the following section, we describe the hardware architecture and communication protocol that enable this biological emulation.

3. Tabletop System Description

Building upon the need for practical, testable platforms that support two-way communication based on diffusion and advection, we designed a Tabletop system that enables controlled experimentation with molecular signal transmission and reception utilizing peristaltic pumps, 3D printed components, a Raspberry Pi, several relays and an ATX power supply. Beyond its research utility, this platform also has educational value, as it is low-cost and constructed from components readily available in most laboratories. The platform simulates molecular communication and diffusion, allowing real-time testing of how signals are exchanged between devices or cells in an environment that mimics the flow of body fluids. Before setting up the experimental platform, the communication scheme of the whole system needs to be determined.

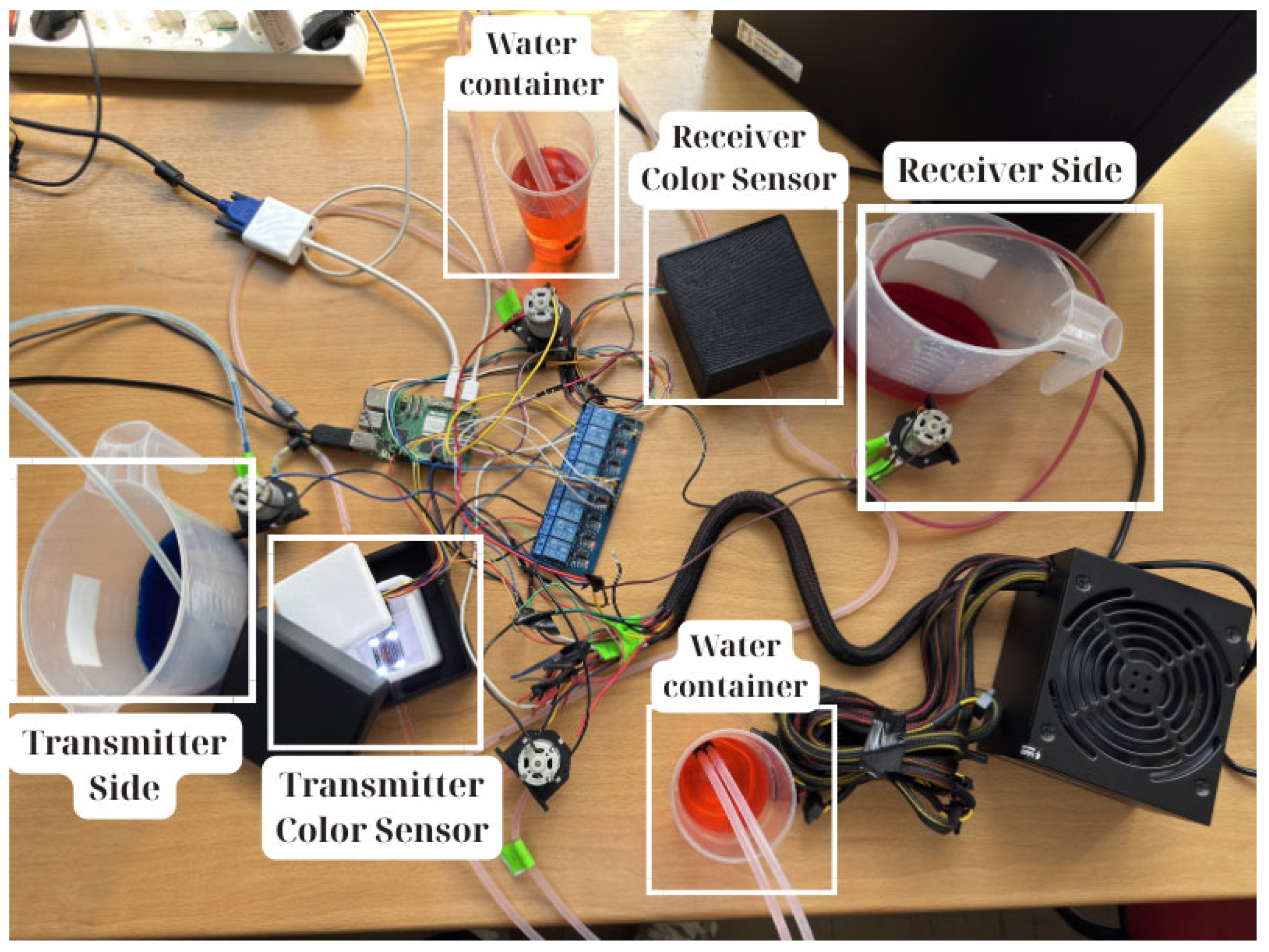

Figure 1 illustrates the system architecture, with the transmitter section shown on the left and the receiver on the right. These two endpoints are connected by a circuit of silicone tubing, which functions as the communication channel. The setup consists of two communication endpoints that exchange signals, thereby simulating MC through diffusion and advection processes in a flow environment analogous to that of the human body.

At one end of the communication system, the transmitter nanomachine injects a blue-colored liquid pulse into the closed-loop fluidic channel, which serves as the propagation medium. The signaling solution is prepared by mixing 1 L of clear water with various concentrations of blue pigment. This pulse propagates through the silicone-based fluidic pathway and is subsequently detected by the receiver nanomachine at the opposite end. Symmetrically, the receiver can generate a red-colored response pulse—prepared under identical conditions with 1 L of clear water and again various concentrations of red pigment—thus enabling bidirectional molecular-like signaling. Each communication end can alternate roles between transmitter and receiver during successive communication cycles, thereby modeling molecular feedback exchange within a fluidic medium. To ensure high-fidelity detection of molecular signals and prevent optical interference, each nanomachine is enclosed within a 3D-printed white housing, itself encapsulated in a 3D-printed black shielding box, ensuring complete isolation from ambient light sources. This design maintains measurement consistency and reduces environmental interference. The sensors capture both color types and intensity, enabling signal decoding.

The system employs Concentration Shift Keying (CSK) modulation for communication, where the presence of a colored pulse (blue or red) represents a pulse of signaling molecules and is subsequently decoded at the receiver. Signal detection is performed through a threshold-based mechanism that determines whether a valid pulse has been received.

A central control system, implemented on Raspberry Pi 5, orchestrates valve operations, timing sequences, and sensor monitoring, including both color detection and flow measurements. Via a relay module incorporating 8 relays, the control unit operates the peristaltic pumps, which release either colored or clear liquid into the fluidic channel. This architecture enables precise coordination of signal generation, flow regulation, sensor data acquisition, and system flushing, thereby ensuring reliable operation and repeatability of the communication process.

To prevent pressure buildup and ensure safe fluid management during repeated operation cycles, two intermediate containers were integrated into the tubing system. These containers serve as buffering reservoirs, each filled with different amounts of clear water, providing liquid storage and facilitating flow stabilization across the closed-loop channel. Their inclusion was essential to mitigate overflow risks and avert potential system failures arising from unbalanced pressure conditions within the closed-loop environment.

Overall, this tabletop system provides a practical and flexible testbed for investigating bidirectional molecular communication, offering insights into how diffusion- and advection-based mechanisms can be exploited in biological nanonetworks. In addition, it facilitates controlled experimentation on channel memory and molecule accumulation effects, supports validation of modulation and detection schemes such as CSK, and enables reproducible evaluation of flow-assisted transport phenomena. Beyond its immediate applicability for nanoscale communication studies, the platform also serves as a valuable educational and prototyping tool for bridging theoretical models with experimental verification.

4. Signal Modulation and Demodulation-Detection Algorithm

Effective molecular communication relies on the ability to encode, transmit, and decode information reliably within a fluidic environment. This section introduces the signal modulation and detection framework employed in our system. It outlines how digital information is represented through fluid-based molecular pulses and describes the signal processing techniques used to identify and interpret these pulses.

In diffusion-based molecular communication systems, thresholding mechanisms are employed at the receiver to enable binary detection of incoming message pulses. Given the stochastic nature of molecular diffusion, the use of two asymmetric thresholds (upper and lower) forms a hysteresis loop that improves robustness against noise and signal ambiguity.

Let T

up and T

low denote the upper and lower concentration thresholds, respectively. The receiver registers a “high” state when the molecular concentration C(t) exceeds T

up and reverts to “low” when C(t) falls below T

low. This design mitigates erratic toggling due to marginal signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) and residual tails from previous transmissions (ISI). The molecule count at the receiver under background noise is modeled as a Poisson process:

with mean

variance

, and standard deviation

.

To bound the probability of error, we define

Miss detection probability:

To ensure reliable operation, typical design criteria require .

These bounds translate to a statistical separation between thresholds governed by the total noise variance:

Thus, the minimum threshold separation

must satisfy

with

corresponding to the desired confidence level (e.g.,

.

This inequality imposes a fundamental constraint on how closely the upper and lower thresholds may be placed. Notably, may dominate in systems with slow diffusion clearance or high symbol rates, mandating wider hysteresis margins.

Moreover, real biological environments may exhibit compound Poisson noise, increasing beyond the Poisson assumption. Consequently, attempts to minimize hysteresis width below the bound given above will elevate error rates unless mitigated by

- ○

Adaptive or dynamic thresholding schemes;

- ○

Receptor state feedback;

- ○

Pre- or post-processing techniques (e.g., filtering, timing correlation).

In summary, hysteresis threshold separation must be explicitly designed as a function of the system’s stochastic characteristics, and we followed this approach to set the upper and lower thresholds of the system. The bound serves as a quantitative guideline to balance signal fidelity with responsiveness in the receiver logic.

4.1. Modulation Scheme and Pulse Representation

In molecular communication systems, information encoding can be achieved through various modulation schemes, each exploiting different physical or chemical properties of molecular signals. The five fundamental types include molecular concentration coding, molecular type coding, release time coding, molecular quantity coding, and molecular structure coding. Among these, our system adopts molecular concentration coding, wherein the presence or absence of a molecular pulse within a transmission window conveys binary information [

19]. Each communication endpoint releases a pulse (colored fluid) to represent a logical ‘1’ and as it does not count on synchronization; to send a logical ‘0’ the system can send another type of color fluid. This simple yet effective approach facilitates robust binary signaling and is well-suited to flow-based experimental platforms like the one implemented in this work. Future work could incorporate a synchronization mechanism between the two communicating ends, thereby enabling the exploitation of intentional non-transmission as a valid signaling option, with the receiving end interpreting it as a logical ‘0’.

Communication occurs over a flow-assisted molecular channel, where signals propagate through a combination of diffusion and externally induced advection, enabled by four peristaltic pumps installed within the system. These pumps, as detailed in

Section 3, ensure continuous fluid motion through a closed-loop silicone tubing network, effectively simulating biologically relevant transport conditions such as blood circulation. Molecular pulses, represented by increased local concentrations of signaling molecules, are carried by this flow, allowing for directional and timely propagation toward the receiving endpoint. The use of advection improves signal reliability and reduces transmission delay compared to purely diffusion-based systems, while still preserving the inherent randomness of molecular propagation that characterizes biological environments.

In this context, we apply Concentration Shift Keying (CSK), a modulation scheme where digital information is encoded as distinct variations in signaling molecule concentration and is part of the molecular concentration coding. Each pulse represents a data bit by temporarily increasing the concentration in the medium. This concentration change is then decoded at the receiver by observing the dynamic optical response of the fluid.

A key engineering challenge in implementing this CSK scheme within a closed-loop system was the management of internal pressure during repeated fluid injections. In a fully sealed environment, the continuous introduction of liquid pulses for signaling would gradually increase the internal volume and pressure, risking system rupture, backflow, or sensor misalignment.

To address this, we incorporated two intermediate open-top fluid containers (max 200 mL) into the system design. These reservoirs act as dynamic buffers, allowing excess fluid to be displaced during each injection cycle. Positioned symmetrically within the loop, they help stabilize the system by maintaining consistent flow. Each container contains a base level of clean fluid (clear water) and serves as a controlled overflow point, ensuring continuous circulation without risking backflow, tubing stress, or fluid leakage during extended operation. This solution was crucial for ensuring the safe and stable operation of the system. By preventing pressure buildup inside the tubing, it helped maintain unidirectional flow and avoided problems such as leaks, blockages, or tubing deformation. In addition, the open design of the containers made it easier to fill the system, clean it, and reset it between experiments. Overall, this setup provided a practical and reliable way to manage fluid volume and pressure, allowing the molecular communication system to function consistently and without interruption.

While the physical implementation details (e.g., colored liquids and tubing flow) are handled at the hardware level, the modulation process is abstracted as a CSK-based binary communication system, where each bit is represented by a concentration pulse of signaling molecules. Unlike conventional molecular communication models that rely on global timing structures—such as synchronized transmission windows or predefined time slots—our platform employs an event-driven scheme. In this approach, message generation is triggered dynamically: a node transmits a new pulse only upon successful reception and decoding of the previous message at the receiver side. This asynchronous mechanism more closely resembles biological signaling behavior, where responses occur reactively rather than in predetermined intervals [

27].

The timing characteristics of each pulse, specifically the injection duration and fluid volume, were experimentally determined to ensure clear signal generation and minimize ISI. Each pulse is introduced into the system by activating one of the peristaltic pumps for a fixed duration of approximately 3 s. During this time, 5 mL of colored fluid (either blue or red) was injected into the main tubing loop, creating a molecular concentration pulse that propagates towards the receiver.

It should be noted that although the injected message pulse corresponds to 5 mL, the measured flow velocity corresponds to 9.2 mL per 3 s. This difference arises because the flow rate was measured while the fluid was already in motion, whereas the 5 mL pulse volume is defined from the instant the pump activation command is given, i.e., before the flow reaches its steady state.

The main system parameters related to this modulation setup are summarized in

Table 2.

Although the injection time for each pulse is always fixed at 3 s, there is no strict schedule that defines exactly when each new bit must be sent. Instead, the timing between transmissions depends entirely on how the system behaves. Specifically, each node waits until it receives a concentration pulse before sending its own response. In this way, communication happens bidirectionally through CSK signaling molecules, and the system naturally adjusts its rhythm depending on how fast or slow the signals propagate and are decoded at the receiver.

Having defined the modulation mechanism and pulse transmission procedure, the next critical aspect of the system involves detecting these signals at the receiver side. In the following section, we describe the signal detection process and the algorithms employed to reliably decode incoming molecular pulses under various flow and noise conditions.

4.2. Signal Detection Process

The detection algorithm at each receiver node operates in two primary stages: continuous signal sampling and pulse validation. Sampling is performed by optical color sensors positioned downstream of the transmission point, capturing changes in fluid color that indicate molecular signal arrival. These sensors acquire RGB readings at regular intervals, generating time-series data for each transmission cycle.

Functionally, this sensing mechanism emulates the ligand–receptor interactions observed in biological nanonetworks, wherein chemical messengers diffuse through the extracellular medium and bind selectively to receptors on target cells. In the proposed system, however, molecular binding is substituted with optical intensity measurements, whereby the concentration of signaling molecules is decoded. A propagating concentration pulse induces measurable variations in the detected optical signal, serving as an experimental analog to biological receptor activation.

To reliably detect the presence of transmitted CSK pulses under various flow conditions, we implemented two complementary signal validation strategies, each designed to identify a valid transmission based on the characteristics of the received optical signal. These methods are detailed in the following subsections.

4.2.1. Threshold-Based Pulse Validation

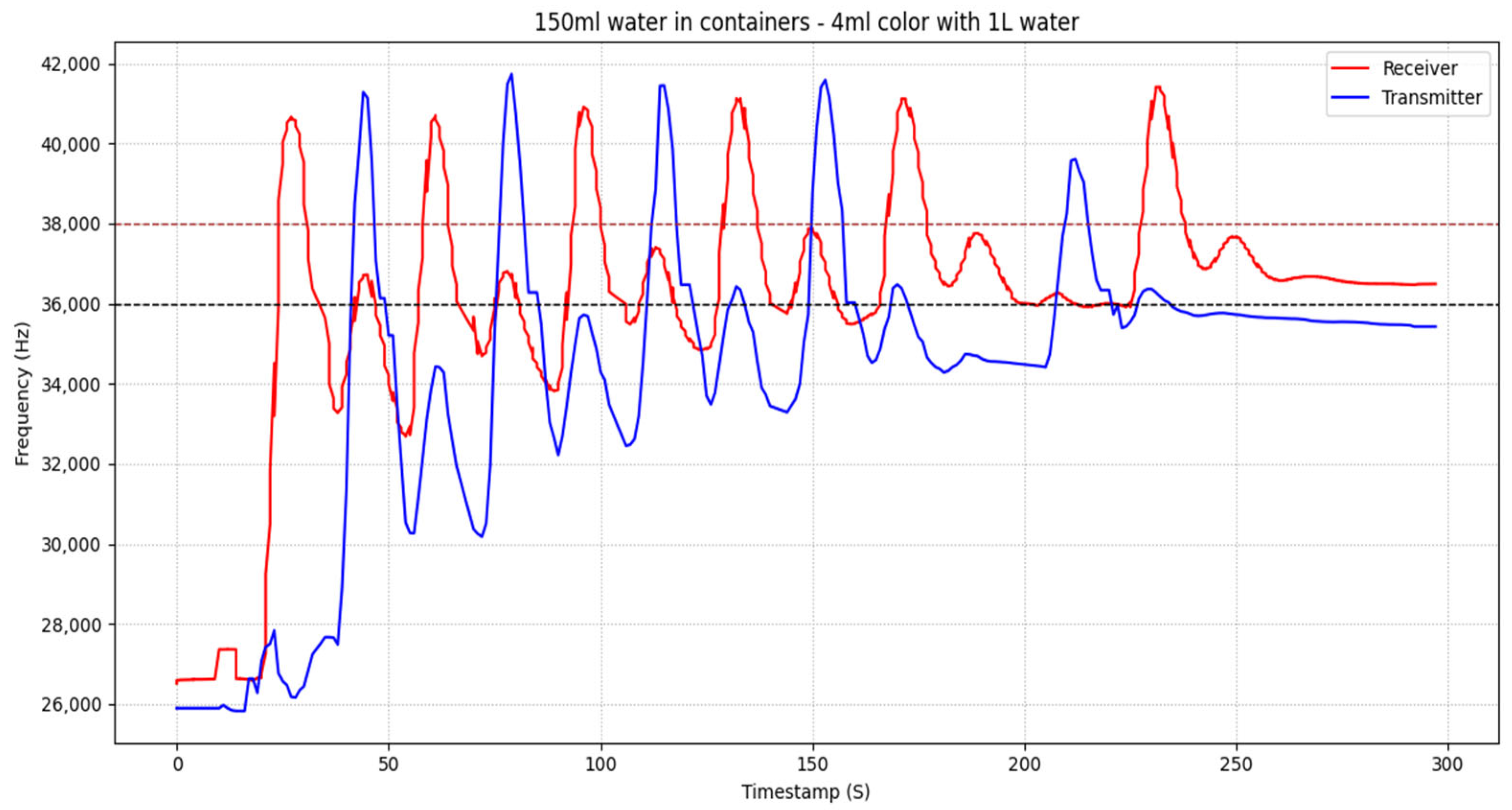

In the first validation method, we applied a dual-threshold mechanism to the sensor data to ensure robust detection of molecular pulses, as illustrated in

Figure 2. This strategy is grounded in well-established signal detection principles, where a signal is only considered valid if it exhibits a clear rise above an upper threshold, followed by a return below a lower threshold. The upper threshold is indicated by the red dotted line at

38 kHz, while the lower threshold is indicated by the black dotted line at

36 kHz.

This approach helps to reduce false positives caused by sensor noise or residual color tails from previous transmissions. Similar threshold-based detection schemes have been successfully applied in prior MC platforms such as those by Farsad et al. [

5] and Felicetti et al. [

28], particularly in systems using optical or chemical concentration signals under noisy or dynamic channel conditions, where the received signal follows a diffusion-based concentration profile such as

C(x, t): concentration at position x and time t;

M: total released substance (mass or number of molecules);

D: diffusion coefficient, indicating spreading out rate.

To determine the appropriate threshold values, we initially conducted a series of experimental runs where colored pulses of varying volume were injected into the system under stable flow. During each run, the optical sensor readings were recorded and analyzed to capture the signal rise and decay pattern over time. These signal traces enabled us to identify consistent peaks and baseline levels, from which we empirically selected threshold values that could reliably differentiate valid pulses from background noise.

The upper threshold was set slightly below the average peak intensity of strong pulses to ensure detection without saturating the sensor, while the lower threshold was positioned above the observed noise floor to ensure pulse resolution. This calibration procedure was guided not only by empirical observations but also by theoretical principles established in prior studies on molecular communication. Specifically, insights from concentration-based models such as those presented in [

29] suggest that the concentration profile at the receiver is a function of both the distance from the transmitter and time. These models typically derive from Fick’s laws or inverse Gaussian formulations and help justify the shape and expected bounds of the received signal. Thus, our manually defined thresholds are consistent with both experimental observations and theoretical expectations for concentration-based pulse propagation [

30].

In this validation method, two thresholds are applied to the incoming sensor data:

An upper threshold, which must be exceeded to register the rising edge of a potential pulse (38 kHz).

A lower threshold, which must be crossed downward to confirm pulse resolution (36 kHz).

These values were not arbitrarily chosen but derived from the experimental calibration process described above. Once the typical peak and baseline signal levels were identified across multiple pulse injections, the thresholds were selected to fall just below the average peak (for the upper limit) and safely above the noise floor (for the lower limit). This ensures that a valid pulse is only registered when the signal rises above the upper threshold and then falls below the lower one—reflecting a full transmission event. The method is particularly effective under stable flow conditions, where pulses are well-formed and optical signal transitions are sharp. In such cases, the dual-threshold approach provides reliable binary classification, minimizing both false positives and missed detections.

This calibration approach ensured that the selected threshold values accurately reflected both the dynamic range of the sensor and the system’s background noise characteristics. However, given that real-world molecular environments are often subject to variations in flow rate, pulse dispersion, and sensor drift, relying solely on fixed thresholds may be insufficient in all conditions. To address this, an additional detection strategy was developed, based on identifying significant relative signal drops rather than depending solely on absolute signal values. The following section introduces this complementary method and demonstrates its role in enhancing detection robustness under less predictable operating conditions.

4.2.2. Drop-Based Detection

To increase robustness under non-ideal conditions—such as variable flow profiles, signal attenuation, or sensor noise—we implemented the following detection strategy based on relative signal drop rather than fixed thresholds.

This method relies on the dynamic behavior of the signal over time. The receiver node continuously monitors the sensor output and analyzes the sequence of incoming data points in real time. The algorithm begins by identifying a local peak in the signal, that is, a point where the frequency stops increasing and begins to decline. From this peak onward, the algorithm evaluates whether the signal has dropped by at least 35% compared to that peak and more than 3 kHz compared to that peak value. The additional constraint of a minimum absolute drop of 3 kHz ensures robustness against shallow dips that might otherwise be misinterpreted as valid signals. If both conditions are satisfied, the system registers the event as a valid pulse reception.

The process is repeated iteratively: once a drop is detected and a message registered, the algorithm resets its baseline to the most recent minimum and searches again for a new peak, continuing this loop for the duration of the communication cycle. This ensures that even under non-ideal conditions—such as when the signal does not return fully to the baseline or when successive pulses partially overlap—real transmissions can still be identified based on relative changes in the signal.

The system incorporates two alternative detection strategies, each suited to different operating conditions. The threshold-based method is highly effective under ideal circumstances, providing clear binary classification when pulses are well-formed and the signal reliably returns to baseline. However, it may fail when pulse dispersion increases or when the baseline drifts, as is often the case in closed-loop systems. In such scenarios, the 35% drop method proves more effective, since it relies on relative changes in the signal rather than absolute levels. This approach enables the detection of a larger number of pulses, particularly under challenging conditions, albeit with a higher susceptibility to false positives in noisy environments. By selecting between these two methods according to system behavior, the detection process maintains a balance between robustness and sensitivity across variable operating conditions.

While the previous subsections described the practical aspects of signal modulation, pulse representation, and detection algorithms, a complementary analytical framework is needed to better understand and predict the underlying transport phenomena. In particular, the interplay between advection and diffusion fundamentally shapes how molecular pulses propagate, disperse, and accumulate in the closed-loop system. To capture these dynamics and link the experimental results with theoretical expectations, we introduce a mathematical model that describes the temporal evolution of dye concentration within the receiver chamber (water container as shown in

Figure 1) with the appropriate stochastic noise term.

4.3. Mathematical Modeling of Advection–Diffusion Dynamics

In order to provide a rigorous and physically grounded description of the molecular signal propagation in the proposed bidirectional fluidic communication system, this section introduces a comprehensive advection–diffusion mathematical model. The model explicitly captures the coupled dynamics of the transmitter and receiver chambers, the pulsed flow actuation, molecular dispersion effects, stochastic uncertainties, and the sensor calibration process.

4.3.1. Coupled Advection–Diffusion Equations

The temporal evolution of the dye concentration inside the transmitter and receiver chambers is modeled through a pair of coupled first-order differential equations:

where

: dye concentration in the transmitter and receiver chambers (mg/mL);

: time-varying inflow rates generated by the pumps (mL/s);

: injected concentration pulse trains (mg/mL);

: chamber volumes (ranging from 100 to 250, typical 120 mL);

: molecular diffusion coefficient (3.5 × 10−3 cm2/s -measured);

,: inlet–outlet distances inside the chambers (0.6 cm);

: stochastic noise terms accounting for experimental uncertainties.

Formulations (2) and (3) model each chamber as a well-mixed control volume, where concentration changes arise from inflow-driven advection, diffusive losses, and stochastic perturbations.

4.3.2. Physical Interpretation of Model Terms

The advection term

represents the replacement of fluid inside the chamber due to pump activation. When a pulse is injected, incoming dye-enriched fluid increases the chamber concentration proportionally to the flow rate and inversely to the chamber volume.

The diffusion loss term

models molecular dispersion from the sensing region. Although advection dominates transport, diffusion contributes to the gradual decay and smoothing of the concentration signal between pulses.

The noise term η(t) captures unavoidable experimental imperfections, ensuring that the model reflects real system behavior rather than an idealized deterministic response.

4.3.3. Piecewise Flow Rate Definition

Pump actuation is explicitly modeled as a piecewise-defined function, reflecting the discrete pulse-based operation of the peristaltic pumps:

with

= 3 s (denoting the pump activation duration);

(defining the transmission times of the transmitter);

(receiver response times—time interval between message reception from receiver to transmitter);

= 30 s (communication cycle duration).

The delay parameter accounts for the system-level response time required for signal detection, decision processing, and role switching between receiver and transmitter. The cycle duration was selected to provide sufficient temporal separation between successive pulse injections, allowing the concentration signal to stabilize and reducing inter-symbol interference caused by channel memory and fluid recirculation. This formulation accurately reflects the on–off nature of the physical pumps and ensures temporal alignment between theoretical inputs and experimental actuation.

Formulations (6) and (7) accurately reflect the on–off nature of the physical pumps, ensuring temporal alignment between theoretical inputs and experimental actuation.

4.3.4. Input Pulse Concentration Profiles

The injected dye concentration is modeled as a train of Gaussian pulses, capturing the smooth temporal dispersion of dye during injection:

where

: pulse amplitudes (typically 40 mg/mL);

: pulse widths (3–5 s);

: total number of transmitted pulses.

Gaussian pulses (8) and (9) provide a physically realistic approximation of the combined effects of pump inertia, tubing dispersion, and mixing dynamics.

4.3.5. Molecular Count per Pulse

To establish biological relevance and enable comparison with molecular communication literature, the injected signal strength is quantified in terms of molar concentration and molecular load, based on the actual experimental preparation of the working fluid. In the proposed setup, information is conveyed using water-based food coloring (blue and red), which is dissolved in water and transported through the fluidic channel via pump-driven advection.

The colored solution is prepared by diluting liquid food coloring into water. Specifically, a volume of approximately 40 mL of liquid food coloring is added to 1 L of water. Assuming a density close to that of water (≈1 g/mL), this corresponds to an injected dye mass of approximately 40 g per liter of solution. The resulting mass concentration is therefore

This value reflects the actual experimental preparation and is used consistently across all experimental runs.

Commercial food coloring consists of mixtures of dyes and additives, the exact composition of which is typically proprietary. To enable a physically meaningful molecular-scale analysis, each color is modeled using a representative FDA/EFSA-approved food dye chromophore, which captures the dominant molecular component responsible for optical absorption and sensor response. In particular, the blue and red food colorings are represented by Brilliant Blue FCF (E133) and Allura Red AC (E129), respectively.

The molar concentration of the injected solution is computed using the standard relation:

where

denotes the molecular weight of the representative dye.

For the blue dye (Brilliant Blue FCF,

[

30],

For the red dye (Allura Red AC,

[

31],

The corresponding molecular concentration is obtained by multiplying the molar concentration by Avogadro’s constant

Each transmission pulse corresponds to the injection of a fixed volume of colored solution, determined by the pump flow rate and activation time. With a pump activation duration of 3 s and a flow rate of 3.07 mL/s, the injected pulse volume is approximately

The molecular load per pulse is therefore estimated as follows:

4.3.6. Stochastic Noise Characterization

The additive noise terms

are modeled as zero-mean Gaussian processes:

Noise sources include

Sensor noise (TCS3200 frequency fluctuations ±0.5 kHz);

Flow variations due to pump pulsatility (±2%);

Timing uncertainties in relay activation (±50 ms);

Minor optical variations from ambient lighting.

Baseline measurements estimate ≈ 0.3–0.5 kHz after conversion to concentration units.

4.3.7. Advection Dominance Justification (Péclet Number)

The dominance of advection over diffusion is quantitatively justified using the Péclet number:

Equation (12) confirms that molecular transport in the system is advection-dominated, validating the modeling assumptions and the neglect of back-diffusion effects.

It should be noted that backward diffusion from the receiver towards the transmitter is physically negligible in the proposed system. This is quantitatively justified by the extremely high Péclet number (Pe ≈ 6.2 × 105), which indicates advection-dominated transport. As a result, no back-diffusion term is included in the coupled equations. Furthermore, molecular degradation effects are not considered, since the employed dye remains chemically stable over the experimental time scale and does not undergo biological or chemical decay. Finally, stochastic terms are explicitly incorporated in the model in a Langevin-type formulation to account for experimental variability, sensor noise, and pump-induced fluctuations, which are consistently observed even under identical operating conditions.

4.3.8. Calibration and Goodness-of-Fit

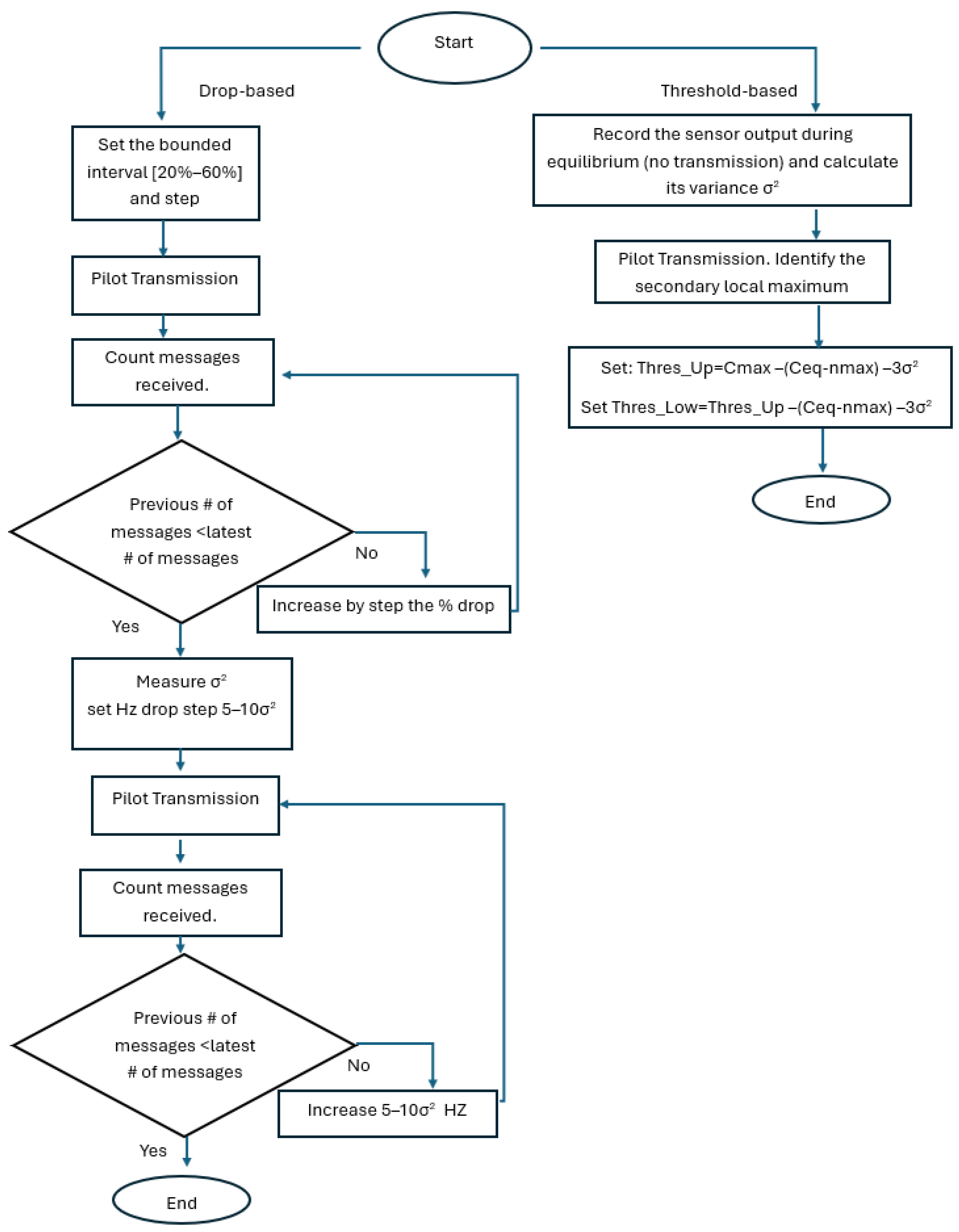

To mitigate the limited generalizability of fixed, empirically tuned detection parameters across different fluids, sensors, and channel geometries, we adopt a self-adjusting receiver design that leverages real-time sensor feedback. Instead of assuming static thresholds or a single empirical drop percentage, the receiver estimates baseline variability at equilibrium and uses short pilot transmissions to automatically configure its reception boundaries. This approach of adaptive threshold mechanism using real-time sensor feedback explicitly accounts for time-varying noise floors, drift, and pump-induced recirculation artifacts (e.g., secondary peaks), thereby improving robustness without increasing algorithm complexity.

The proposed reception detection framework operates in two phases. In Phase I (calibration), the receiver sets the detection parameters using real-time sensor feedback (baseline/noise statistics and pilot pulses) instead of relying on fixed, empirically chosen constants. In Phase II (normal operation), the communicating nodes perform the typical bidirectional message transfer using the calibrated parameters while continuously updating baseline/noise estimates to remain robust to drift and channel-memory effects. Both sensor calibration methods are shown in

Figure 3.

For the drop-based calibration, we calibrate the percentage-drop parameter, p, by searching a bounded interval [20%, 60%] with a step of 5% (starting at 20%). For each candidate p, a short pilot transmission is executed, and the receiver counts the number of correctly detected messages N(p). The algorithm increases p while performance improves; once performance decreases, the selected percentage is the previous value (local maximum under monotonic stepping), denoted by p*. To further suppress false positives under varying noise floors, we estimate the baseline variability at equilibrium and compute the variance σ2. We then enforce an additional minimum absolute-drop requirement in Hz, proportional to σ2 (starting from 5–10*σ2), so a symbol is declared only if it satisfies both: (i) relative drop ≥ p* and (ii) absolute drop ≥ 5σ2. And we increase this frequency drop in each step for the best p found in the previous sub-step. This yields a hybrid decision rule that adapts to sensor noise and drift.

For the dual threshold method, we first record the sensor output during equilibrium (no transmission) and estimate its variance σ

2. A 3σ

2 margin is employed as a conservative separation between baseline variability and true signal excursions, similar to common practice in detection-limit heuristics and statistical process monitoring/control limits [

32]. Next, we transmit a single pilot pulse and measure (i) the peak response C

max, (ii) the final equilibrium level after the pulse C

eq and (iii) the full transient trajectory until equilibrium. The transient inspection is necessary because, when pumps operate in the second cycle, a secondary local maximum may appear due to water recirculation; without explicit transient awareness, this peak could be misinterpreted as an additional symbol.

Let nmax denote the maximum observed noise amplitude (estimated from equilibrium and defined as Δ = (C

eq − nmax). The high and low thresholds are then set as

After calibration, nodes proceed with standard bidirectional communication (role switching between transmitter and receiver). The receiver applies the calibrated percentage-drop and/or hysteresis (dual) thresholds to decode symbols. Baseline/noise statistics continue to be updated online to maintain robustness against any type of artifacts.

In parallel, since the color sensors measure frequency shifts (Hz) rather than concentration directly. Sensor frequency is linearly related to concentration through

where

The linear form of Equation (21) was chosen to establish a direct and computationally simple relationship between the simulated concentration and the raw sensor readings, facilitating the validation process.

A single global calibration function was derived by pooling all experimental data together, providing a unified mapping from concentration to frequency. This approach reflects a consistent sensor model across different volumes (120, 100, 150 mL) and experimental runs. The resulting calibration was:

Goodness-of-fit metrics were obtained by comparing the experimentally measured sensor frequency signals with the model-predicted frequency values derived from the simulated concentration through the global linear calibration. For each experimental run and container volume, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) was computed over the entire time series and subsequently normalized to obtain the NRMSE. The coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated to quantify the linear agreement between measured and modeled signals. Residual analysis was performed by inspecting the distribution of prediction errors over time, confirming the absence of systematic bias. Based on this procedure, the global calibration achieved an overall NRMSE of 8.2%, with volume-specific NRMSE values of 8.3% (100 mL), 7.1% (120 mL), and 9.2% (150 mL), and R2 values ranging between 0.91 and 0.94.

To examine the adaptability of the proposed calibration under different dye conditions, a single global concentration–frequency calibration was employed for both the red and blue dyes, derived from pooled experimental data obtained under identical experimental conditions. The consistent performance of this unified calibration across all datasets, as reflected by the reported RMSE and R2 values, indicates comparable sensor response characteristics for the two colorants within the examined concentration range. The use of a common calibration avoids unnecessary model complexity while maintaining reliable detection. Nevertheless, potential dye-specific calibration remains an interesting direction for future investigation, particularly in scenarios involving colorants with substantially different optical properties.

These results demonstrate that the model faithfully captures the mean dynamics, accumulation behavior, and steady-state response observed experimentally.

4.3.9. Relation to Experimental Results

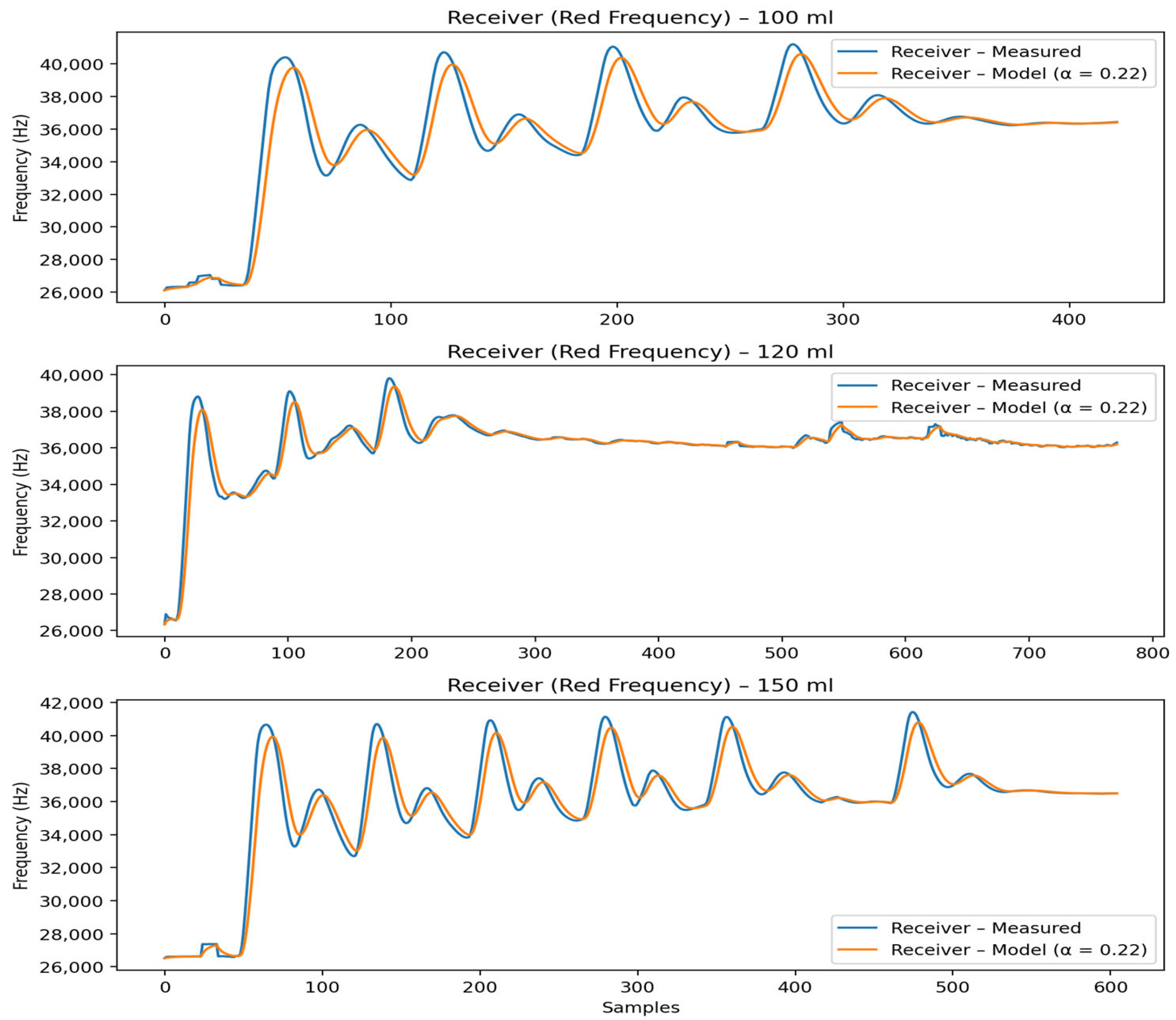

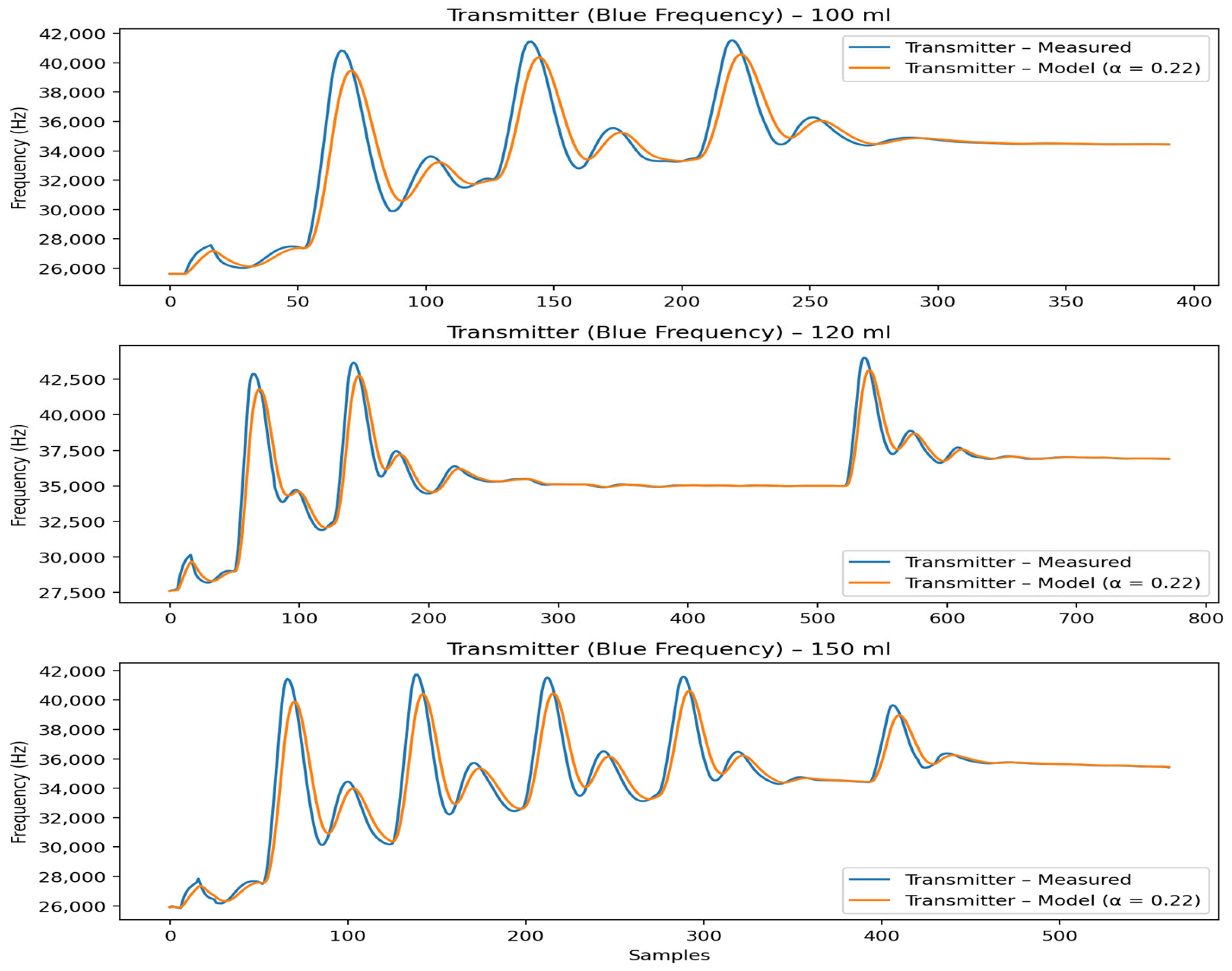

The theoretical predictions directly correspond to the transmitter and receiver frequency measurements shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The model accurately reproduces pulse timing, accumulation trends, and volume-dependent behavior, while higher-frequency oscillations are correctly interpreted as stochastic effects rather than deterministic transport phenomena.

In

Figure 4, the receiver frequency responses for three different container volumes (100 mL, 120 mL, and 150 mL) are depicted. Each subplot compares the experimentally measured receiver signal (red frequency, blue curve) with the corresponding output of the proposed mathematical model (orange curve). The model successfully captures the progressive staircase-like increase in the receiver signal caused by the cumulative arrival of successive molecular pulses. Across all volumes, the timing and overall trend of pulse accumulation are well reproduced, while differences in signal amplitude and relaxation behavior reflect volume-dependent dilution and retention dynamics within the receiver chamber. The lowest RMSE is observed for the 120 mL configuration, indicating optimal agreement between model and experiment, whereas slightly higher deviations for 100 mL and 150 mL arise mainly from sharper experimental peaks and transient oscillations. These high-frequency fluctuations are intentionally not reproduced by the model, as they originate from pulse injection variability and sensor noise. Overall, the results demonstrate that the model accurately represents the dominant transport and accumulation mechanisms governing the receiver response.

In

Figure 5, the transmitter frequency responses for container volumes of 100 mL, 120 mL, and 150 mL are shown. The experimentally measured transmitter signals (blue frequency, blue curves) are compared with the corresponding model predictions (orange curves) obtained using the same global parameter set (α = 0.22). The model accurately reproduces the timing of pulse emissions, the accumulation behavior, and the convergence toward steady-state levels across all examined volumes. Differences in peak amplitude between volumes are consistently reflected in the model and are attributed to changes in effective dilution and flow dynamics at the transmitter node. The RMSE values indicate good agreement for all cases, with deviations primarily associated with sharp experimental peaks and short-term oscillations that are not explicitly modeled. By focusing on the mean dynamic response rather than pointwise fitting, the proposed formulation provides a physically interpretable description of the transmitter-side emission behavior that remains consistent across different fluid volumes.

5. Communication Protocol Design

The communication protocol in our molecular nanonetwork system is designed to enable reliable bidirectional message exchange over a closed-loop fluidic channel, simulating diffusion and advection-based molecular signaling. A key enhancement over previous architectures [

13] is the inclusion of a responsive receiver capable of emitting its own molecular responses, thus completing a full communication cycle with feedback in a closed system.

Each communication round is initiated by the transmitter, which encodes binary data into fluidic pulses using CSK modulation. Specifically, the presence of a colored pulse (blue) corresponds to a new incoming message for the receiver. The transmitter releases a pulse by activating the pump through the relay for 3 s to infuse the blue-colored liquid into the system.

The injected colored liquid acting as a molecular pulse travels through the fluidic channel and reaches the receiver, which is equipped with a color sensor, as described above. The receiver continuously monitors the optical intensity from the color sensor. A valid transmission is recognized in two different ways: (i) the sensor detects a pulse that crosses a preset upper threshold and then drops below a lower threshold (ii) when a relative intensity drop of at least 35% from peak is observed, and this drop is more than 3000 Hz. This hybrid detection strategy ensures robust recognition of incoming messages under varying flow conditions.

We used the TCS3200 color sensor, which produces significantly higher values for the dominant color component when a specific color is detected (e.g., the blue value is noticeably higher than the red value when a blue object passes by, and in the case of red, the opposite occurs). During our observations, we noticed that when a blue object was introduced, the red values exhibited a sharp decrease, while the blue values remained relatively stable, close to their baseline (idle) value. Since we aimed for the color curves to increase—rather than decrease—as more color entered the system, and because the sensor readings ranged between 0 and 50 kHz, we treated 50 as our reference zero and applied the following transformation: Blue = 50 kHz − Red Value.

This inversion allowed the red curve to increase in response to the presence of blue, making it easier to define the upper and lower thresholds, which were 38 kHz and 36 kHz correspondingly. The red values were selected for analysis because they exhibited greater variation compared to the blue values when the blue color passed by the sensor. This made them more sensitive and reliable for detecting changes, especially when setting thresholds.

Upon successful reception and decoding of the message, the receiver switches roles and becomes the new transmitter for the response phase. It generates its own fluidic pulse (red-colored for differentiation) using the same CSK principles and sends it back through the same physical channel. The initial transmitter now acts as the receiver, applying the same threshold-based or differential detection algorithm to interpret the incoming signal; even though we measure different color (red), the same thresholds are used corresponding to the receiver’s response pulse. In the case of red-colored pulses, we applied the transformation: Red = 50 − Blue Value. As mentioned above, the same thresholds were used.

By enabling the receiver to actively respond, our system introduces an interactive communication protocol within the constraints of a molecular medium. This bidirectional capability not only increases communication reliability but also aligns more closely with biological signaling behaviors, where feedback loops, mutual signaling, and dynamic regulation are fundamental [

33,

34,

35]. Such responsiveness allows the system to adapt in real time to environmental fluctuations or transmission errors, enhancing robustness. Furthermore, this design mimics natural cellular communication pathways, such as quorum sensing and synaptic signaling, thereby making the system more suitable for integration with biological or bio-hybrid networks.

6. Experimental Results

This section demonstrates the platform’s communication feasibility and presents experimental data and analysis based on distinct fluid transmission scenarios. Specifically, the first test involves transmission of single-color fluid; the second evaluates message exchange at a fixed rate; the third examines message exchange triggered only when predefined threshold values are exceeded; and the fourth examines message exchange triggered only when 35% drop from the preceding peak.

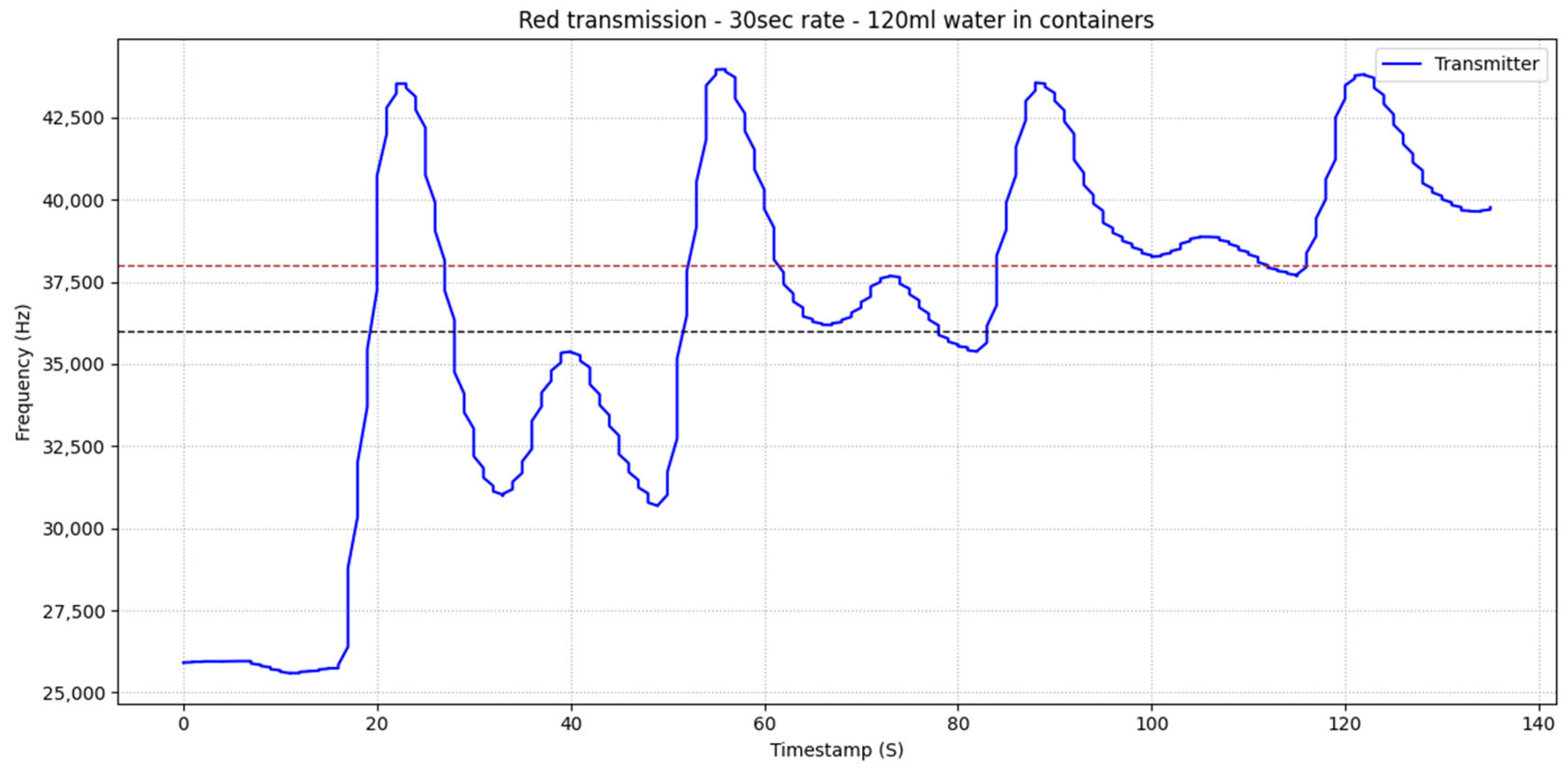

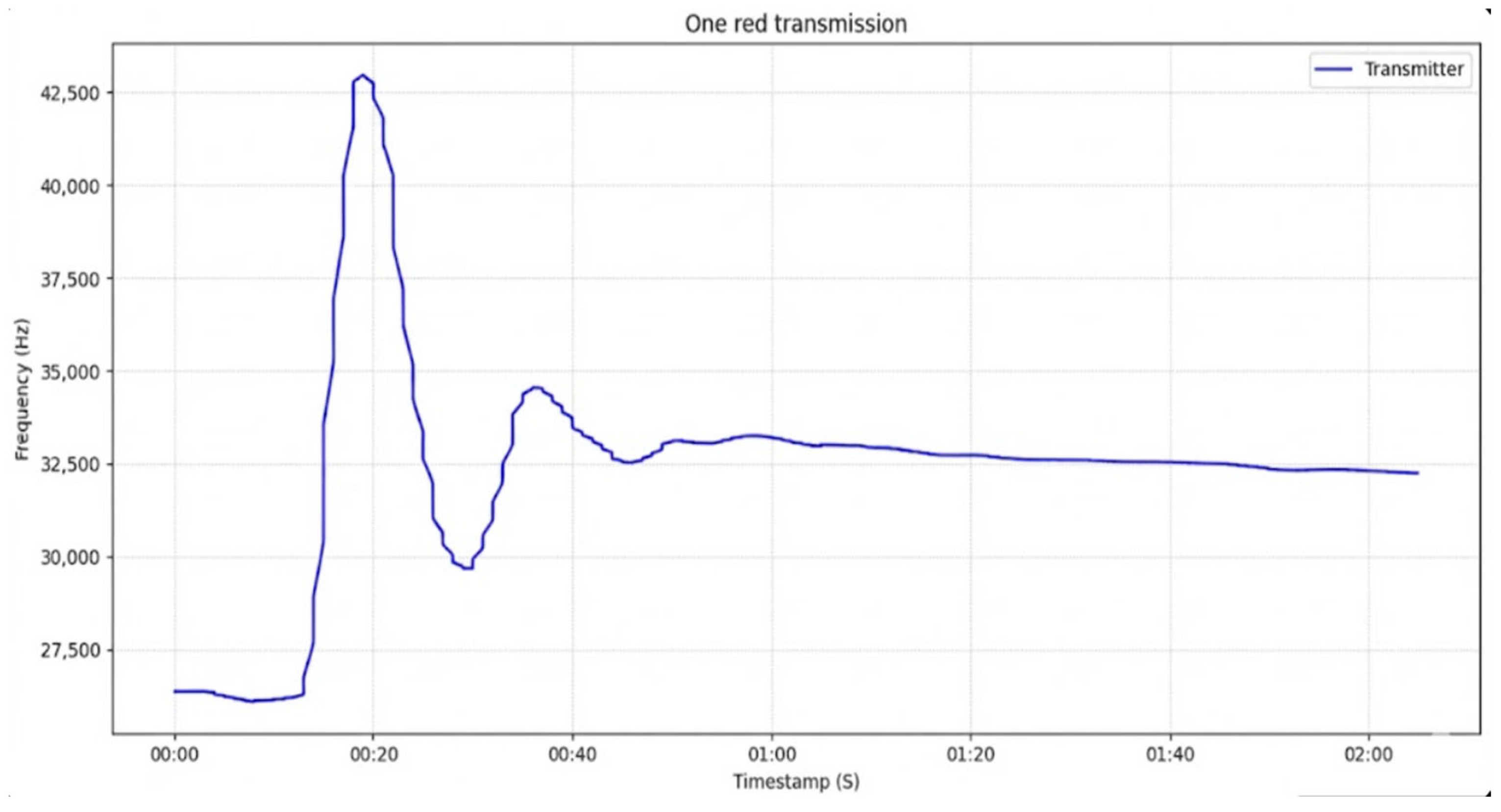

6.1. Single Transmission of Red Fluid

In this experiment, we implemented the transmission of a red fluid pulse, selected as the reference case since it constitutes the basis of the subsequent analysis. Following the detection of the primary signal, secondary peaks were observed in the sensor output. These artifacts originate from the closed-loop configuration of the system, where the inlet and outlet tubes inside the intermediate containers are positioned in close proximity. Under these conditions, only a limited portion of the injected fluid is dissipated, thereby reducing diffusion effects. As a result, residual fluid recirculates through the channel and produces additional attenuated peaks that do not correspond to genuine transmissions but instead represent measurement artifacts induced by the system’s geometry.

In

Figure 6, the first peak represents the intended transmitted pulse. The subsequent secondary peak arises from the recirculation of the red fluid within the closed-loop channel, reaching the sensor in a partially diluted state. A third, considerably smaller peak is also observed, corresponding to a further diluted recirculation of the same pulse. These artifacts are attributed to the geometrical configuration of the circuit, where the inlet and outlet tubing in the intermediate containers are positioned in close proximity. Following these transient responses, the system approaches equilibrium as the injected fluid becomes uniformly diffused throughout the channel.

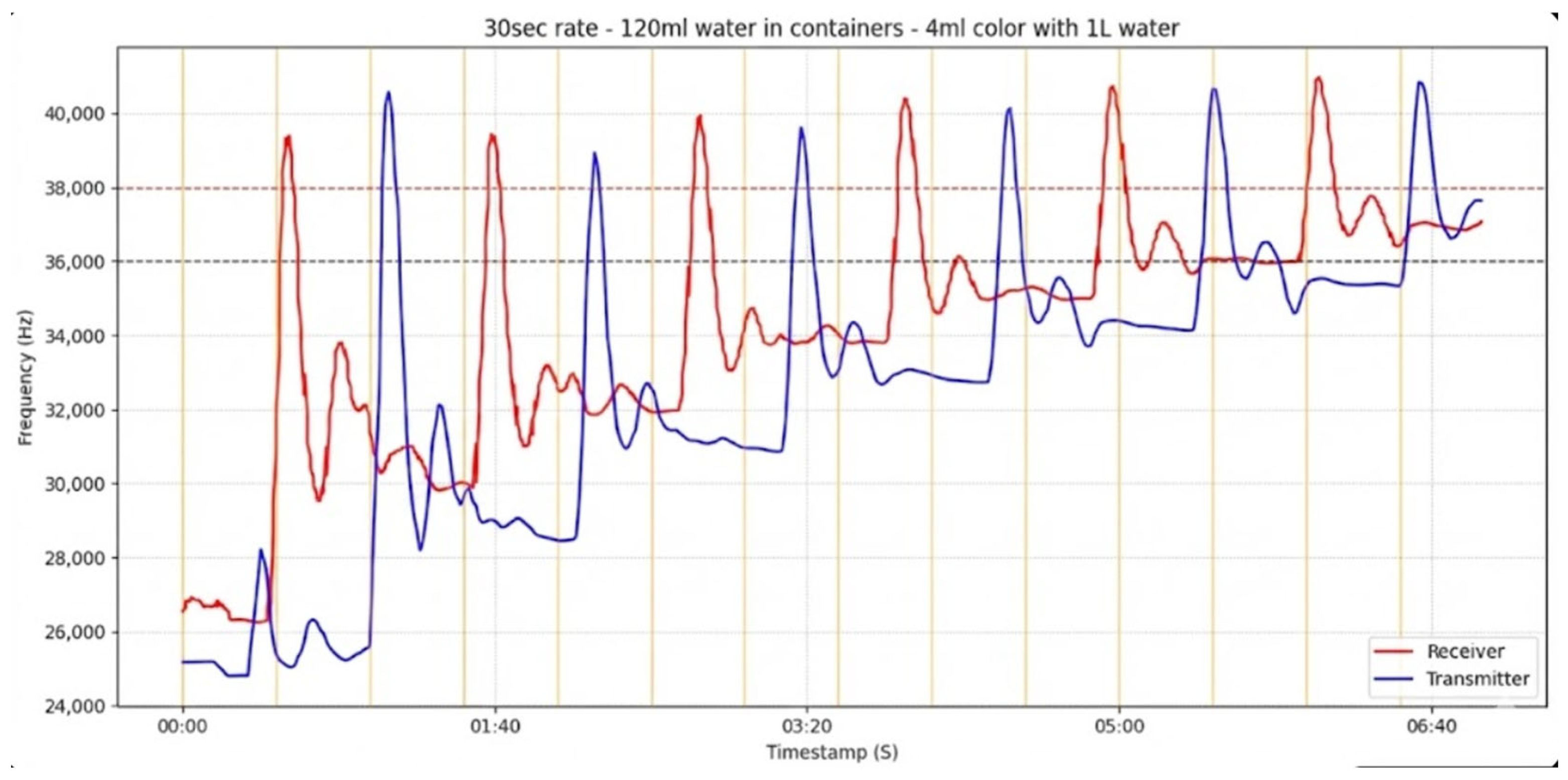

6.2. Message Exchange at a Constant Rate

In the following sections, we analyze how the transmitter and receiver coordinate their bidirectional message exchange by employing the fixed-threshold algorithm, in which a valid pulse is detected when the signal crosses an upper threshold of 38 kHz and subsequently falls below a lower threshold of 36 kHz. Through extensive testing of the blue–red link, we determined that a transmission rate of one pulse every 30 s, combined with the defined thresholds, enables consistent detection of at least four successful exchanges before channel saturation occurs. In this configuration, the transmitter injects a blue fluid pulse at 30 s intervals, while the receiver monitors the corresponding red frequency response. The red component was selected for analysis because it exhibits larger frequency excursions when the blue fluid passes the color sensor, thereby enhancing detection sensitivity, as previously discussed. The choice of a 30 s interval resulted from systematic experimentation: we began with larger inter-pulse periods and gradually reduced the interval until the system could no longer reliably discriminate successive transmissions. At shorter intervals, the reception pattern failed to satisfy the threshold criteria, leading to missed messages.

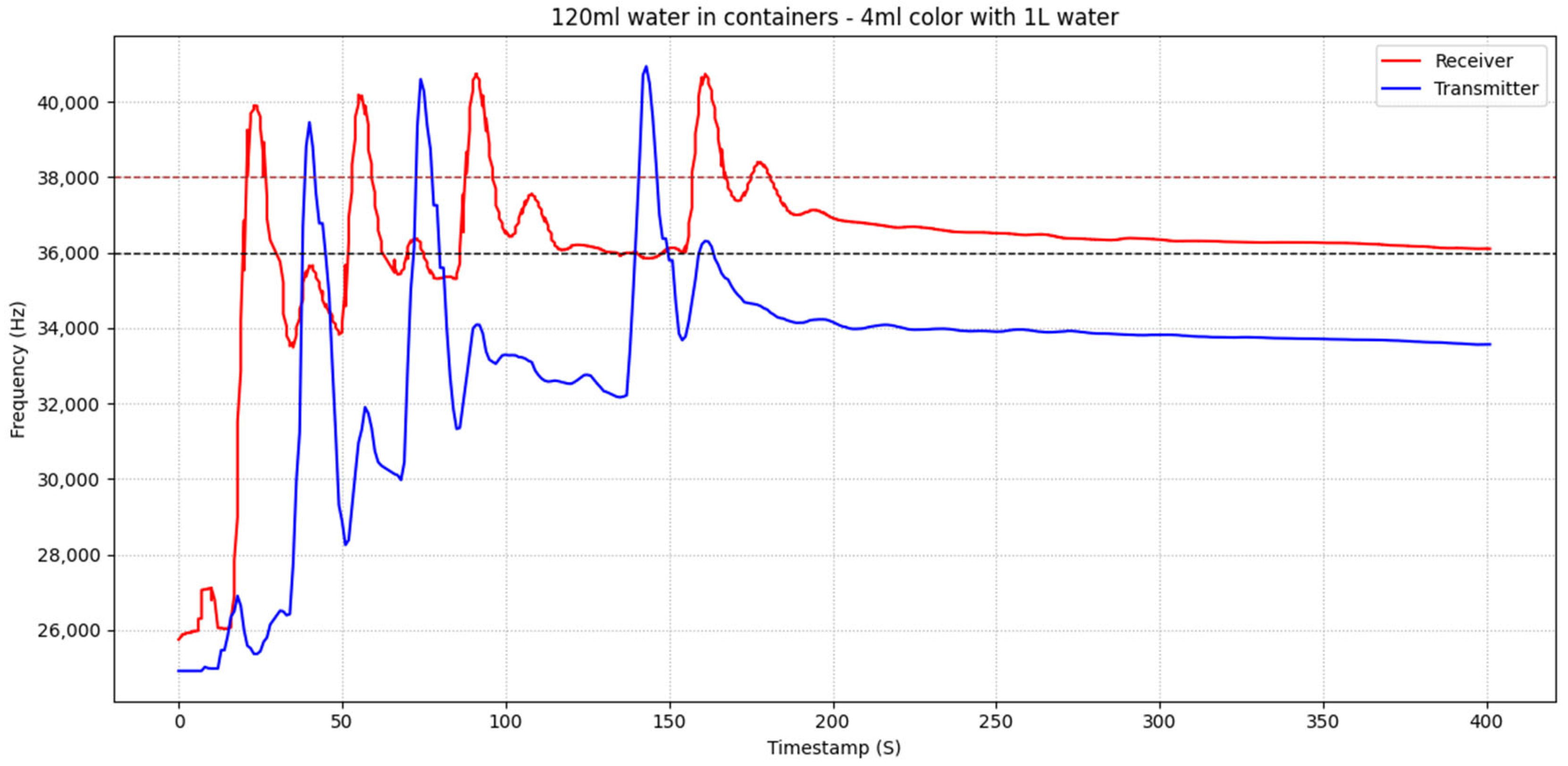

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the receiver discriminates valid pulses from noise by applying a fixed-threshold rule on the red frequency trace: a valid message is registered when the signal first rises above the upper threshold of 38 kHz and subsequently falls below the lower threshold of 36 kHz. When the roles are reversed (i.e., the red fluid is transmitted and the blue component is monitored), the same thresholds are applied at the blue-side sensor to detect return pulses. Under this configuration, both the transmitter and the receiver successfully detected five valid messages while suppressing noise artifacts. However, the last two pulses did not fall below the lower threshold and were therefore not recognized.

6.3. Message Exchange Triggered Only When Predefined Threshold Values Are Exceeded

In this subsection, we present the results of an experiment designed to emulate more faithfully the dynamics of a biological nanonetwork. In this scenario, once a cell-like node receives a message, it immediately generates and transmits a response, thereby reproducing the feedback behavior characteristic of natural molecular communication systems. By implementing this immediate “receive-and-reply” mechanism, the proposed setup more closely approximates biological signaling pathways and highlights the inherently bidirectional nature of molecular exchanges. Two cases are examined: (i) message exchange using fixed thresholds with varying water volumes in the intermediate containers, and (ii) message exchange employing the 35% drop-based detection algorithm. The performance of these two approaches is analyzed and compared to determine which is more suitable for reliable operation of the system.

In

Figure 8, threshold-based communication is illustrated for the case of 120 mL of water in the intermediate containers. The red frequency trace is analyzed from the transmitter’s perspective, as the red component exhibits larger frequency excursions when the blue fluid emitted by the transmitter passes by the color sensor. The receiver successfully detects the first three messages according to the threshold-based rule (upper threshold: 38 kHz; lower threshold: 36 kHz). Each red peak followed by a blue peak corresponds to a complete transmission–reply set, representing the emission of a message by the transmitter and the reply from the receiver. Three distinct communication sets can be identified in the figure.

1st set: The first red peak begins at approximately 00:15 s and reaches its maximum shortly before 00:30 s. A corresponding blue peak appears with a short delay between 00:35 and 00:45 s, indicating successful detection and reply.

2nd set: The second red peak starts near 00:50 s and peaks slightly after 01:00 s. The associated blue response follows between 01:05 and 01:25 s, confirming that the second transmission triggered a valid response.

3rd set: The third red peak initiates around 01:40 s and reaches its maximum near 01:55 s. The subsequent blue peak occurs between 02:00 and 02:20 s, completing the third successful communication cycle. Notably, there is a noticeable gap between the red and blue peaks, which arises because the red signal’s equilibrium level takes longer to drop back below the lower threshold after the transmission. This delayed return prolongs the detection time for the corresponding reply, reflecting the equilibrium state relaxation effect that becomes more pronounced after successive injections.

4th transmission (no reply): At 02:30 s, a fourth red peak is clearly observed, but no corresponding blue response follows. This missed detection results from the equilibrium level of the red signal remaining above the lower threshold (36 kHz), preventing the threshold-crossing condition from being satisfied.

This outcome highlights a practical limitation of threshold-based detection that arises from the closed-loop nature of the system: each successive injection of colored fluid cumulatively increases the overall concentration within the circuit. Consequently, the equilibrium state defined as the sensor’s baseline frequency in the absence of pulses progressively shifts upward after each transmission.

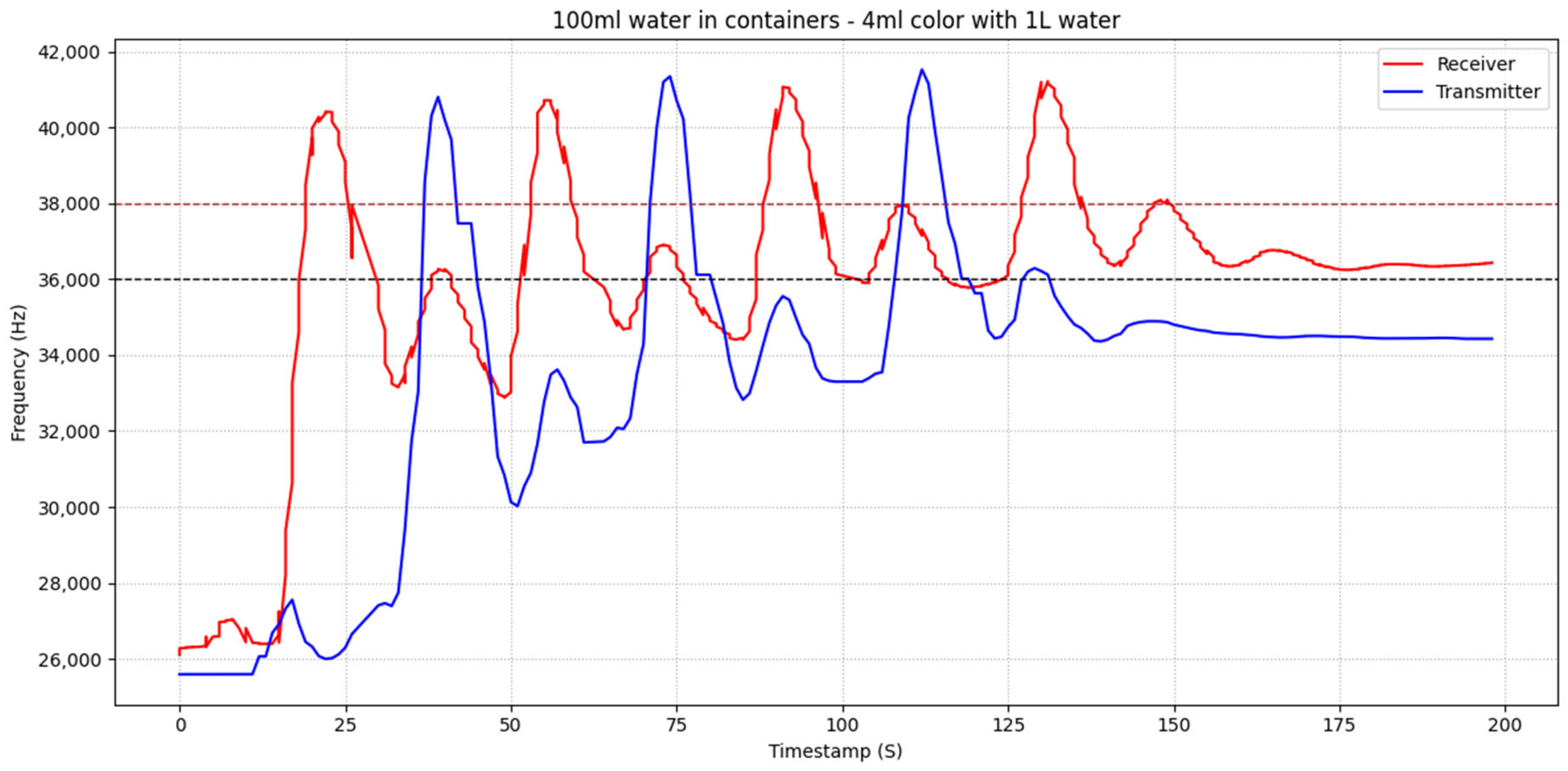

In

Figure 9, threshold-based communication is illustrated for the case of 100 mL of water in the containers. A comparison with

Figure 8 shows that the reduced water volume results in higher sensor intensity, as a larger fraction of the colored substance reaches the receiver’s sensor. Again, the red frequency trace represents the transmitter’s perspective, since the red component exhibits larger frequency excursions when the blue fluid emitted by the transmitter passes the color sensor. The receiver successfully detects the first three messages according to the threshold-based rule; however, the fourth transmission is not registered despite being clearly injected. This limitation stems from the cumulative concentration effect described previously, which prevents the signal from returning below the lower threshold.

Each red peak followed by a blue peak again corresponds to a complete transmission–reply set. Four transmissions are clearly injected, with three successful communication cycles and one missed detection at the end:

1st set: The first red peak begins at approximately 00:15 s and reaches its maximum shortly before 00:25 s. The corresponding blue response follows between 00:35 and 00:45 s, marking the first successful transmission and reply.

2nd set: The second red peak starts around 00:50 s and peaks just before 01:00 s, followed by the blue reply between 01:10 and 01:20 s.

3rd set: The third red peak initiates near 01:20 s, reaching its maximum at about 01:35 s, with the associated blue response occurring between 01:40 and 01:55 s.

4th transmission (no reply): The fourth red peak starts at approximately 02:05 s, but no corresponding blue peak is detected afterwards. As with the 120 mL case, this failure is attributed to the upward baseline drift that keeps the red signal above the lower threshold after multiple transmissions.

In

Figure 10, threshold-based communication is illustrated for the case of 150 mL of water in the containers. One would normally expect lower frequencies at the beginning; however, the color sensor starts measuring from a higher equilibrium state, which results in the observed higher frequency values. Each red peak followed by a blue peak corresponds to a complete transmission–reply set, and in this case, five successful communication cycles are clearly identified:

1st set: The first red peak begins at approximately 00:15 s and reaches its maximum near 00:30 s. The corresponding blue response follows shortly afterward between 00:35 and 00:50 s, marking the first successful exchange.

2nd set: The second red peak starts around 00:50 s, with its maximum occurring near 01:00 s, followed by the blue peak between 01:10 and 01:25 s, confirming the second message and reply.

3rd set: The third red peak initiates close to 01:25 s and reaches its maximum around 01:40 s. The blue reply appears between 01:45 and 02:00 s, confirming the third message exchange.

4th set: The fourth red peak begins near 02:00 s and peaks around 02:10 s. The corresponding blue response follows between 02:25 and 02:40 s.

5th set: The fifth red peak starts at approximately 02:40 s and extends until around 03:20 s, followed by a clear blue response between 03:30 and 03:55 s, completing the fifth successful transmission–reply cycle. A noticeable gap is observed between the end of the red peak and the onset of the blue response. This delay occurs because the red signal’s equilibrium level takes longer to drop below the lower threshold, as the fluid inside the system has become significantly darker after multiple transmissions. The increased concentration of color within the system slows down the fall of equilibrium, causing a delay in the detection of the pulse.

6th transmission (no reply): A sixth red peak is observed around 03:55 s, but no corresponding blue peak follows. This missed detection occurs because the red signal’s equilibrium level never drops below the lower threshold, due to the high accumulated dye concentration within the system after multiple transmissions. As a result, the threshold-crossing condition is never satisfied, and the reply pulse cannot be registered.

Figure 10.

Threshold-based communication with 150 mL water in containers.

Figure 10.

Threshold-based communication with 150 mL water in containers.

The increased water volume provides the system with a larger buffering capacity, enabling the successful exchange of five messages, in contrast to the previous cases where only three messages were reliably exchanged between the two communication ends.

Consequently, the local concentration at the receiver decays more steeply after each peak, as the color is dispersed into a larger water volume and returns highly attenuated. Therefore, the signal crosses below the lower threshold more rapidly between transmissions and the equilibrium state decreases. As a result, the system supports both a greater number of valid exchanges before saturation and a faster turnover between successive pulses compared to the 100 mL and 120 mL cases.

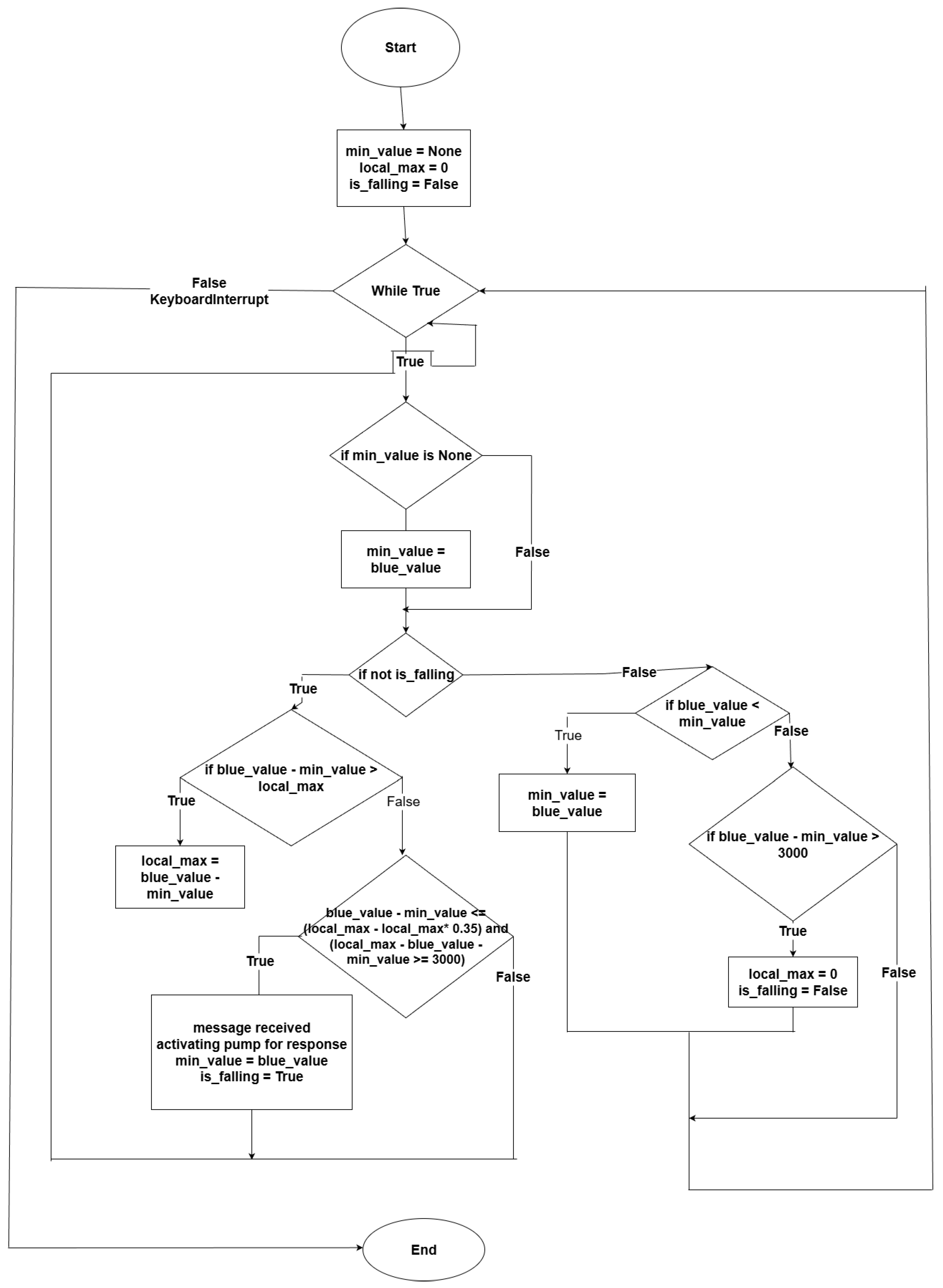

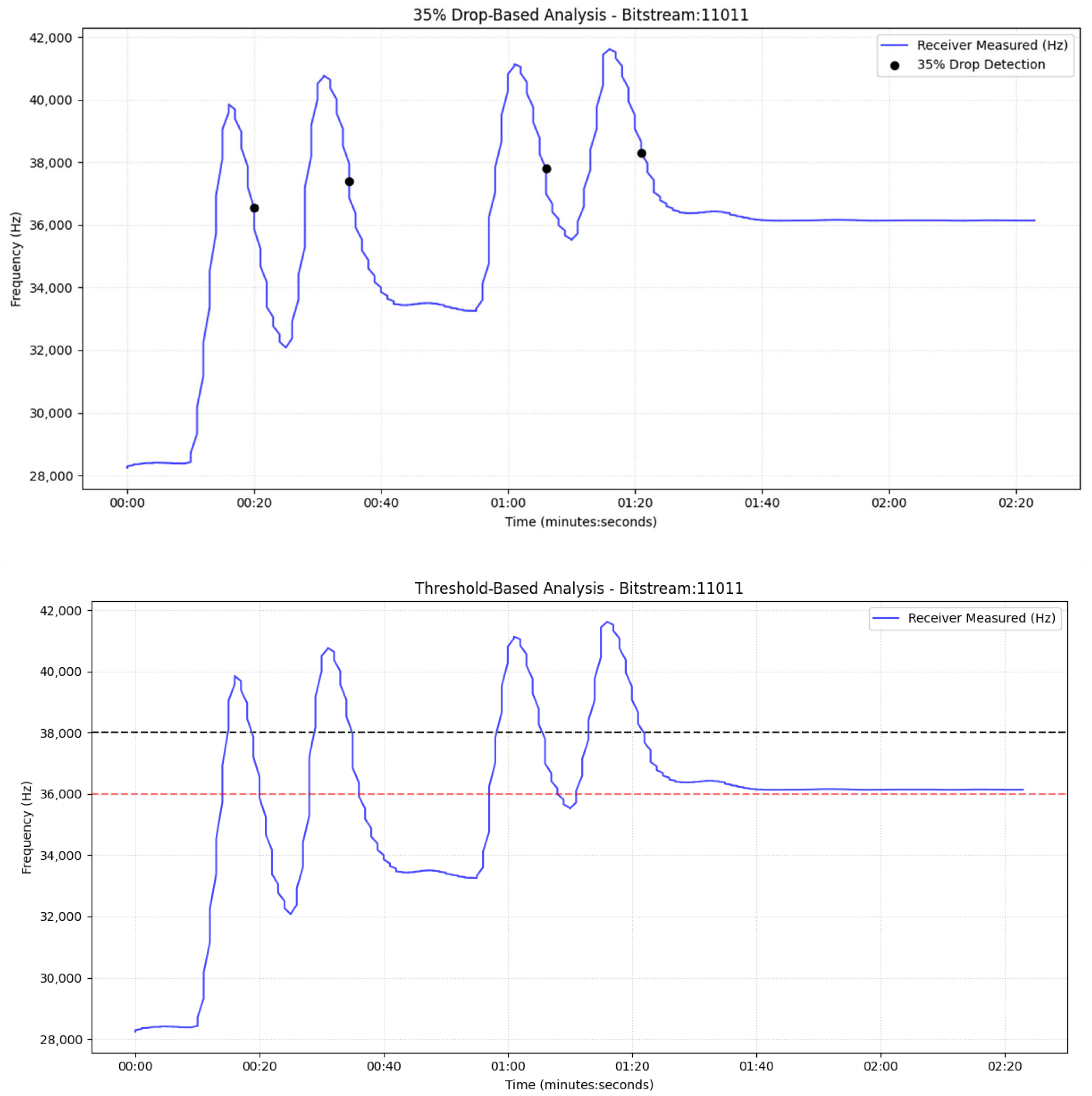

6.4. Message Exchange Triggered Only When There Is a 35% Drop from Last Peak

In this subsection, we analyze the drop-based algorithm. Specifically, the algorithm operates as follows: Initially, it takes the first sensor value as a baseline and subtracts this baseline from all subsequent sensor values until it identifies the first local maximum (peak). Once this peak is identified, the algorithm continuously checks whether the frequency has dropped by at least 35% from that peak and by more than 3 kHz. If these conditions are met, the algorithm recognizes that a pulse (message) has been successfully received. After detecting the pulse, the algorithm then locates the next local minimum, sets it as the new baseline, and repeats the baseline subtraction, peak detection, and drop testing, to detect additional pulses (see flowchart in

Figure 11). We next evaluate this algorithm experimentally.

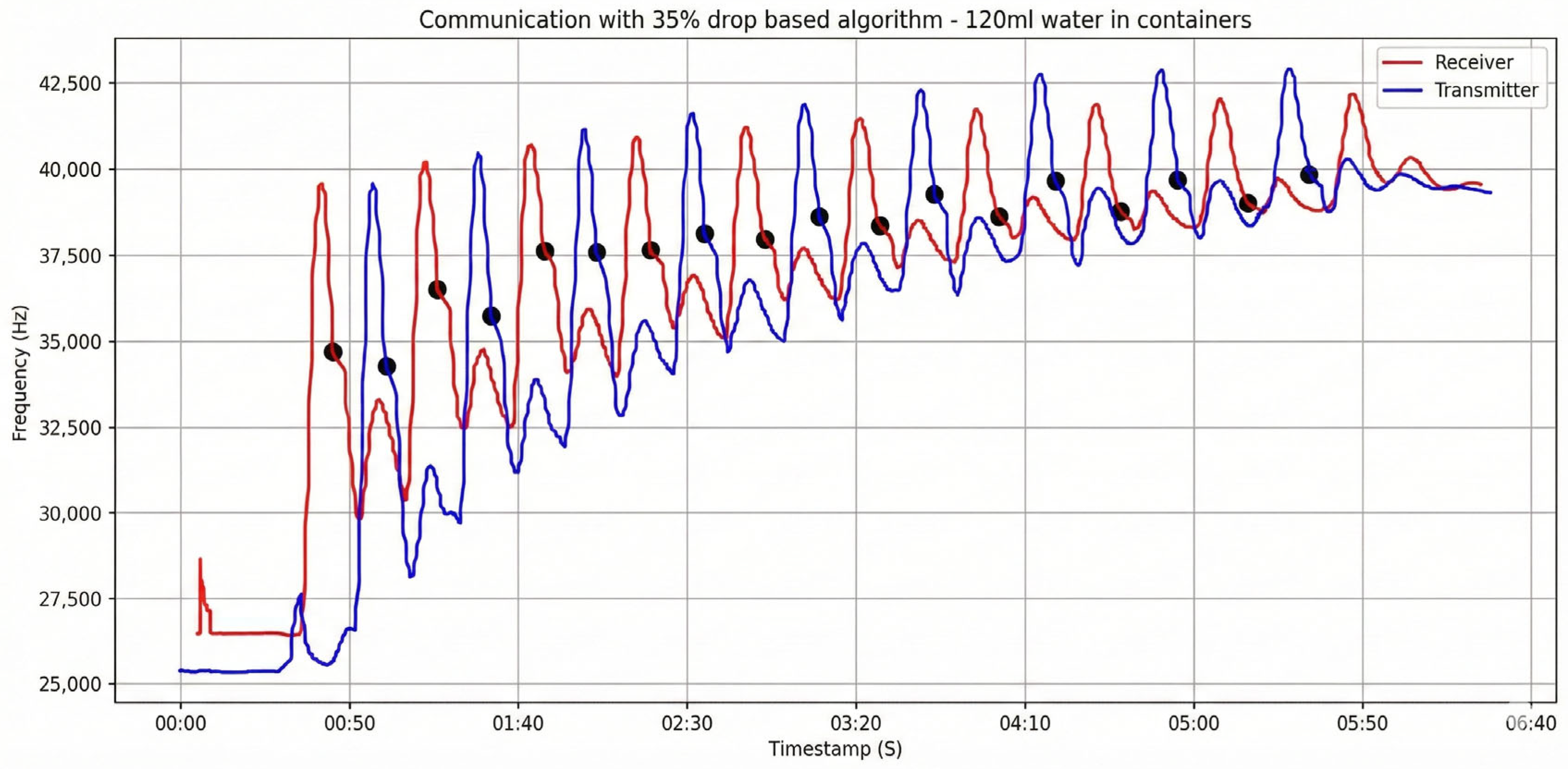

In

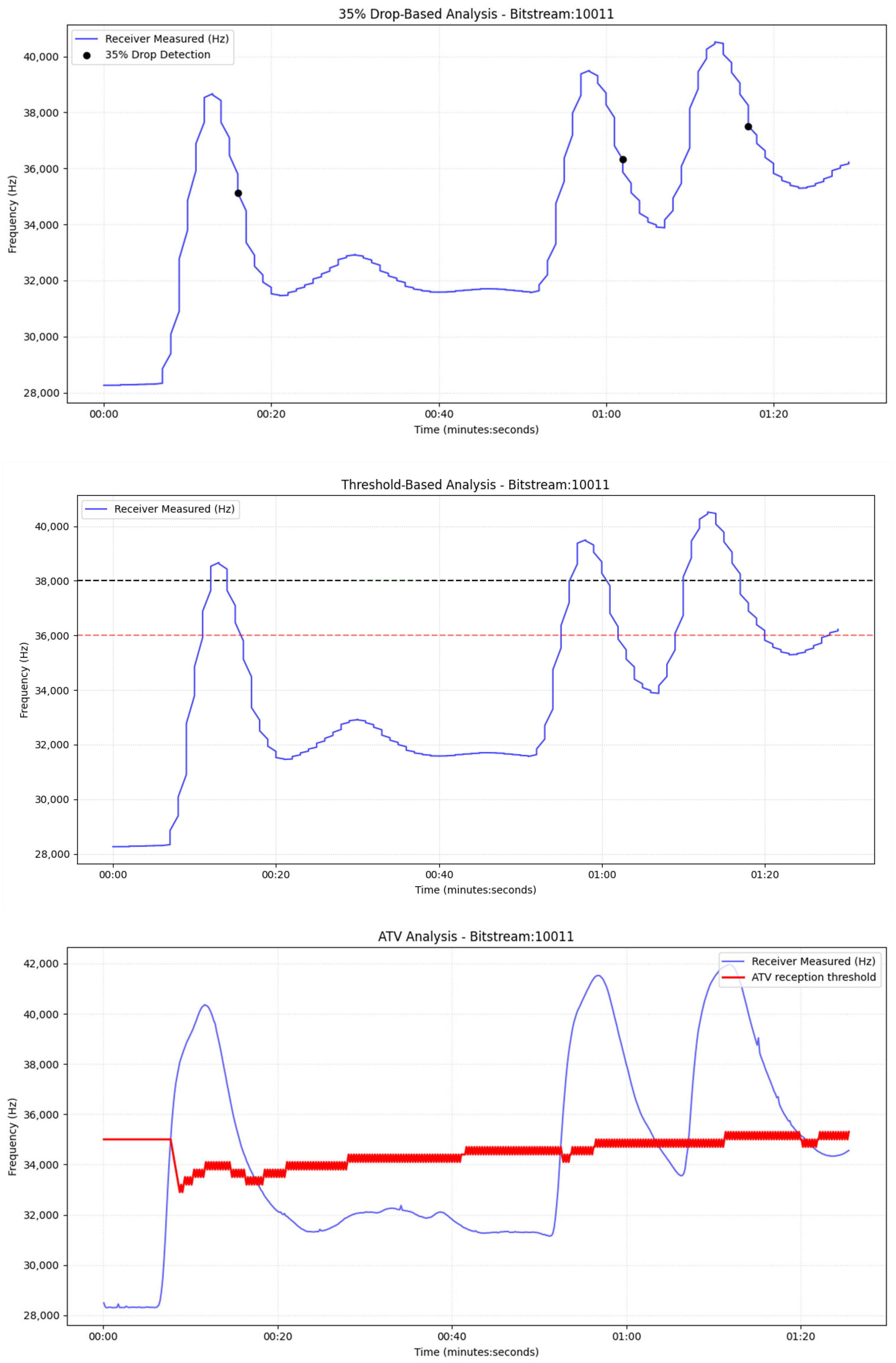

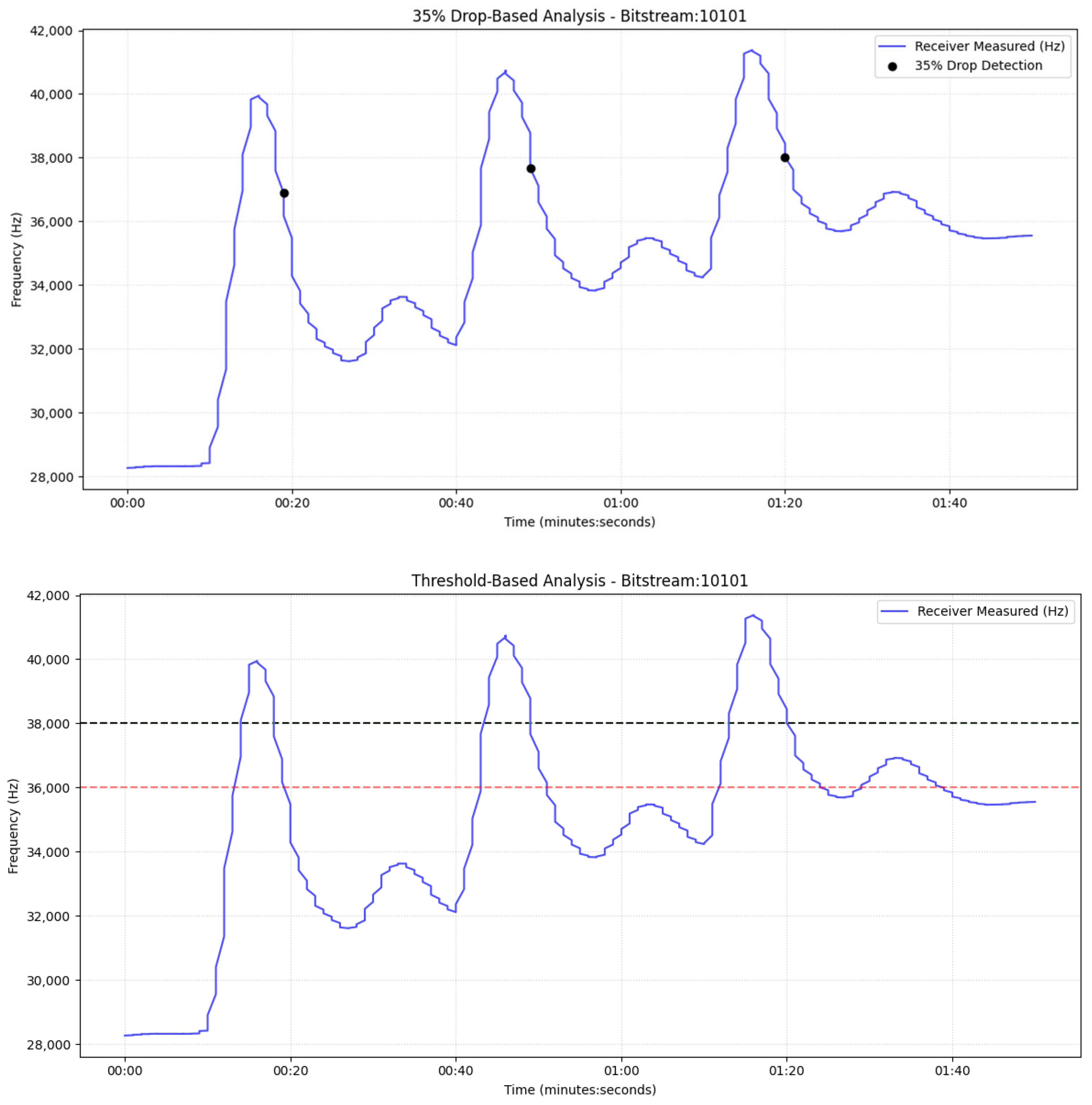

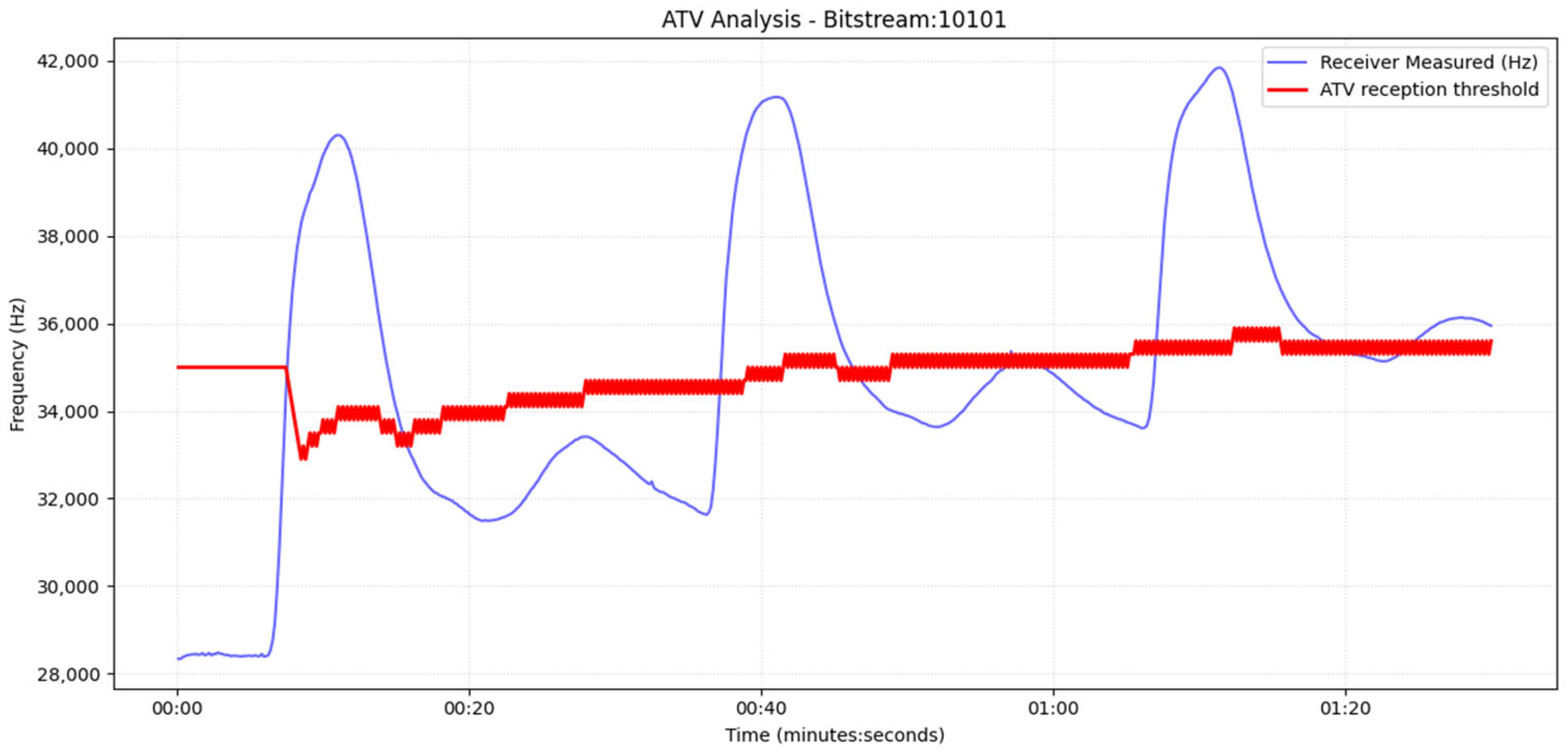

Figure 12, we observe the drop-based communication with 120 mL water in containers, like the experiment shown in

Figure 7; however, in this case, the system does not wait for the signal to drop below the lower threshold to trigger a reply. Instead, a response is sent when a 35% decrease from the last peak is detected, and this drop exceeds 3 kHz. For the receiver we focus our attention on the red frequency line, which corresponds to the signal observed while the transmitter is sending blue liquid, as described earlier. Using the dual drop criterion (≥35% relative to the local peak and >3 kHz absolute), the receiver detects nine distinct messages, indicated by black markers. The tenth transmission is not declared because the post-peak decline fails to simultaneously satisfy the 35% and 3 kHz thresholds.

In the same experiment, the blue frequency trace reflects the transmitter’s measurement of the red reply pulses emitted by the receiver. Applying the drop-based criterion (≥35% relative decrease from the local peak and >3 kHz absolute drop), the transmitter correctly declares all nine responses, as indicated by the black markers.

Based on these observations, the 35% drop-based detector outperforms the threshold-based scheme in our setup. By relying on relative post-peak decreases (≥35% and >3 kHz) rather than fixed absolute levels, it is more robust to baseline drift, channel memory, and saturation effects in the closed loop. Empirically, it enabled a greater number of correctly declared messages, for example, 9 vs. 3 under the 120 mL condition (

Figure 12 vs.

Figure 8)—thereby improving both communication efficiency and reliability. Consequently, the drop-based algorithm is the preferred choice for this molecular communication platform.

6.5. Statistical Analysis

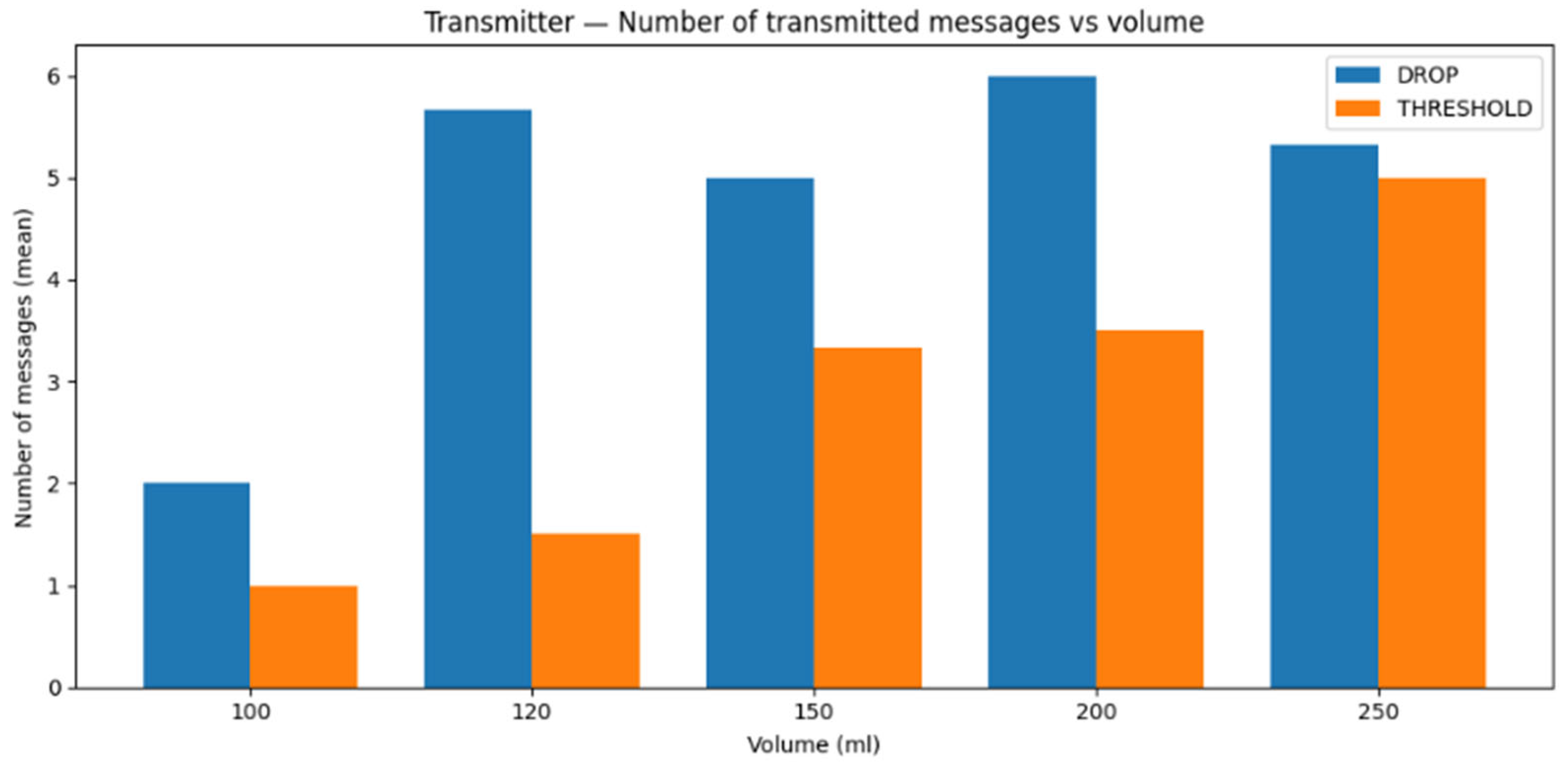

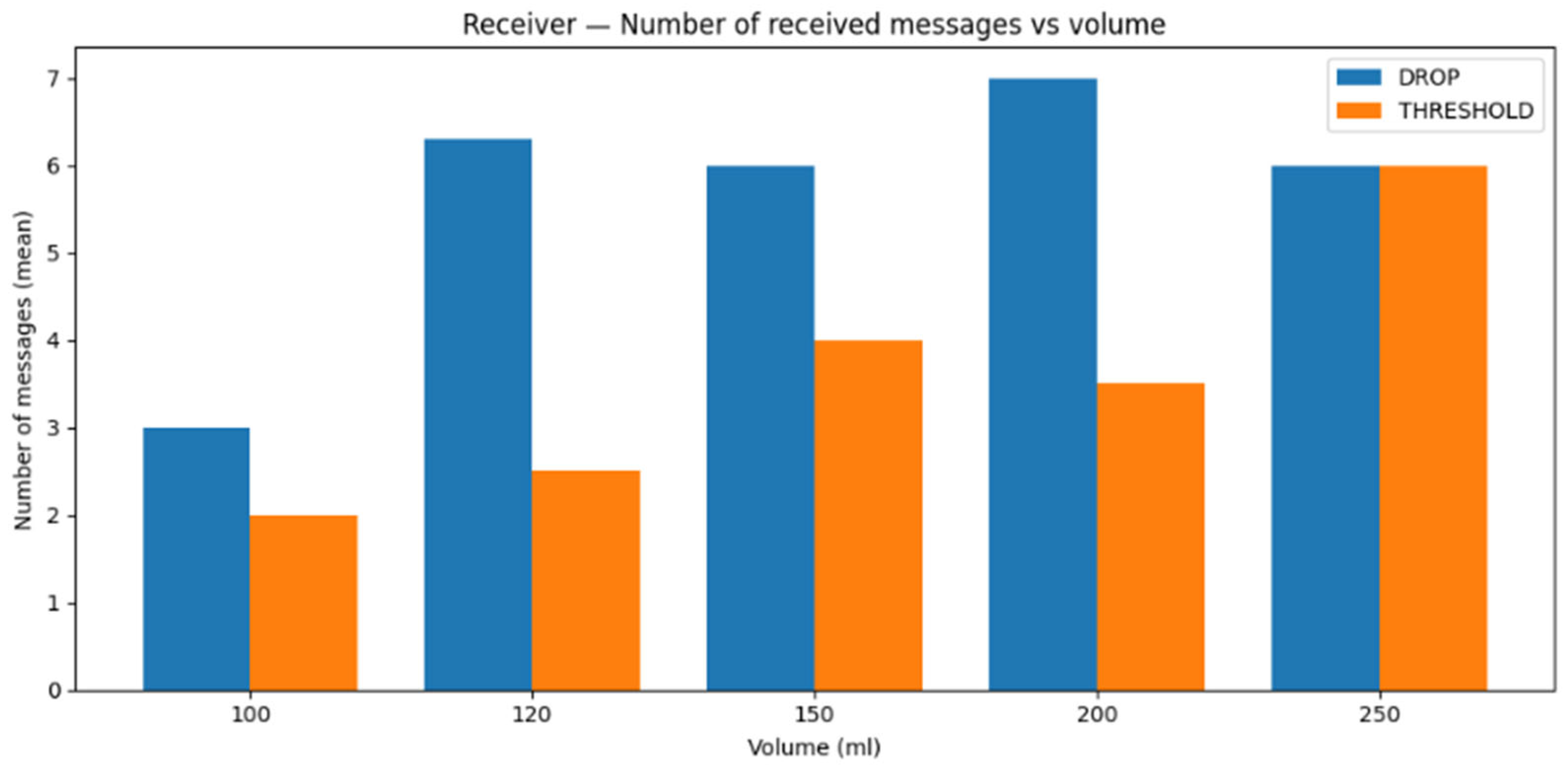

To quantify reproducibility and experimental variability, we performed repeated measurements for each tested water volume (100, 120, 150, 200, and 250 mL) under both proposed schemes (threshold and drop-based). For each configuration and volume, we recorded two latency metrics: first-message latency (time elapsed until the first successfully received message after the start of the trial) and latest-message latency (time associated with the last successful message reception in the trial window) since residual information molecules remaining in the containers can alter the observed latency values.

For each metric, we report the mean and standard deviation across repeated trials (>10).

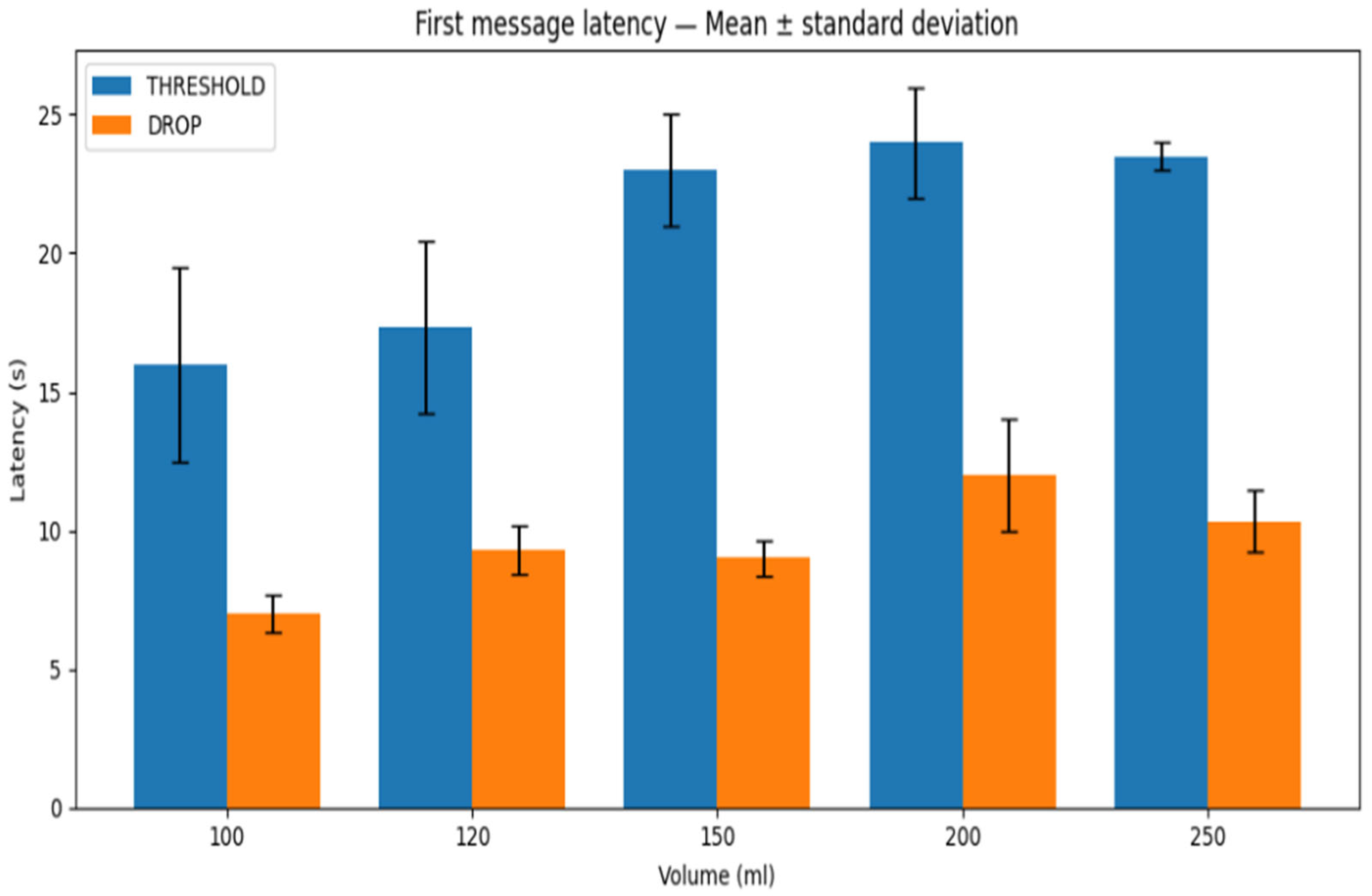

Figure 13 summarizes the first-message latency across all water volumes for both threshold and drop-based algorithms. From the results, threshold-based method exhibits higher first-message latency than drop-based scheme in all tested volumes, with variability that depends on the water volume (standard deviation ranges from sub-second to a few seconds depending on the case).

The same applies to the latest message reception latency, i.e., the time corresponding to the last successfully transmitted and received message within the trial window. The results are shown in

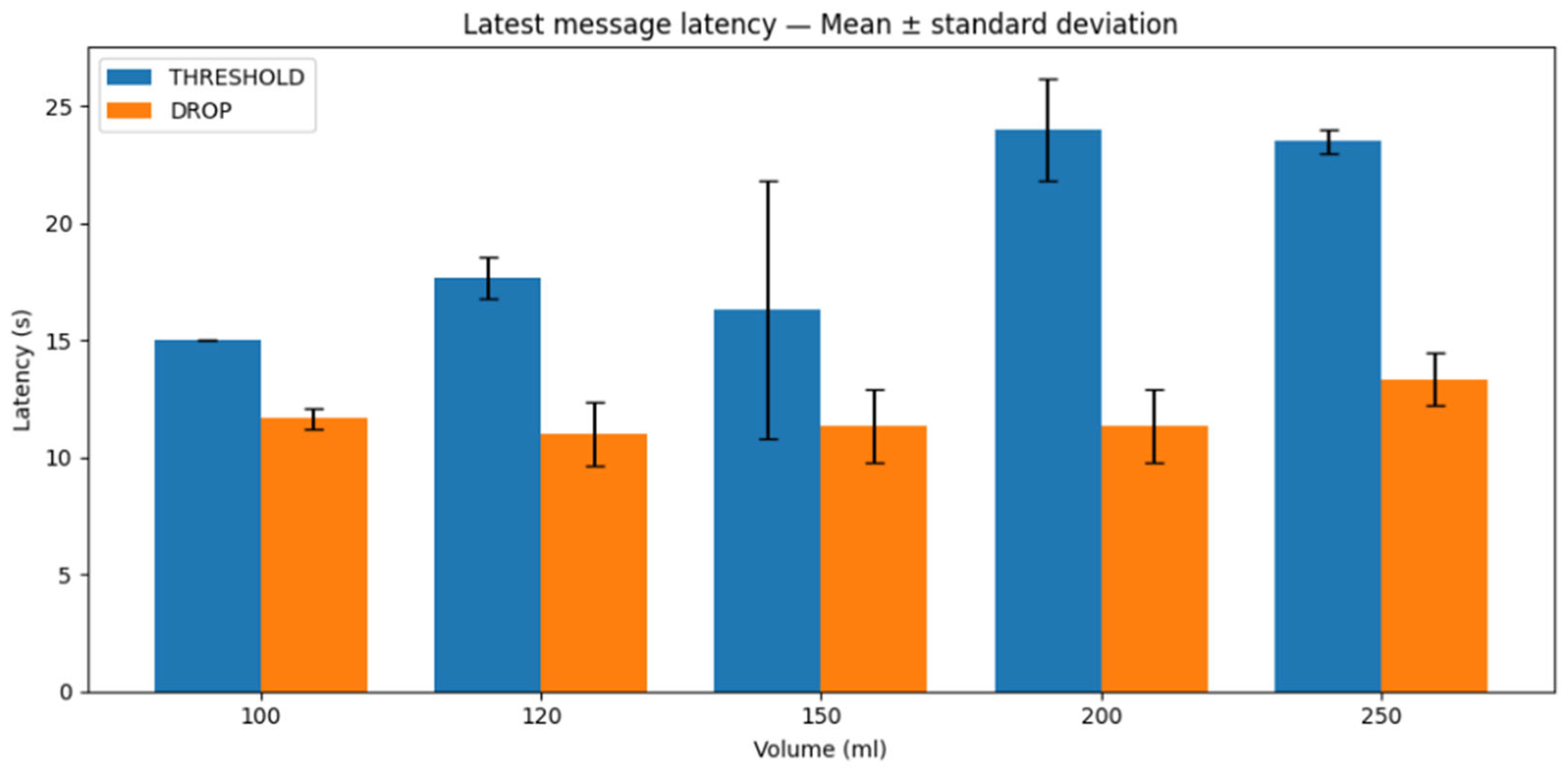

Figure 14. Overall, the latest-message latency is lower for the drop-based scheme than for the threshold-based scheme across the tested volumes. However, one can also discern slightly lower mean values for the threshold-based scheme at certain volumes, suggesting that residual substance up to a point may contribute to faster response times. In contrast, the drop-based scheme appears less favored by residual information molecules, resulting in slower response times, an observation that may also indicate a stronger influence of advection relative to diffusion under these conditions.

For the error rate, we consider the case where the transmitter sends a message, but the receiver fails to sense it due to the high concentration of information molecules in the system, near system saturation conditions.

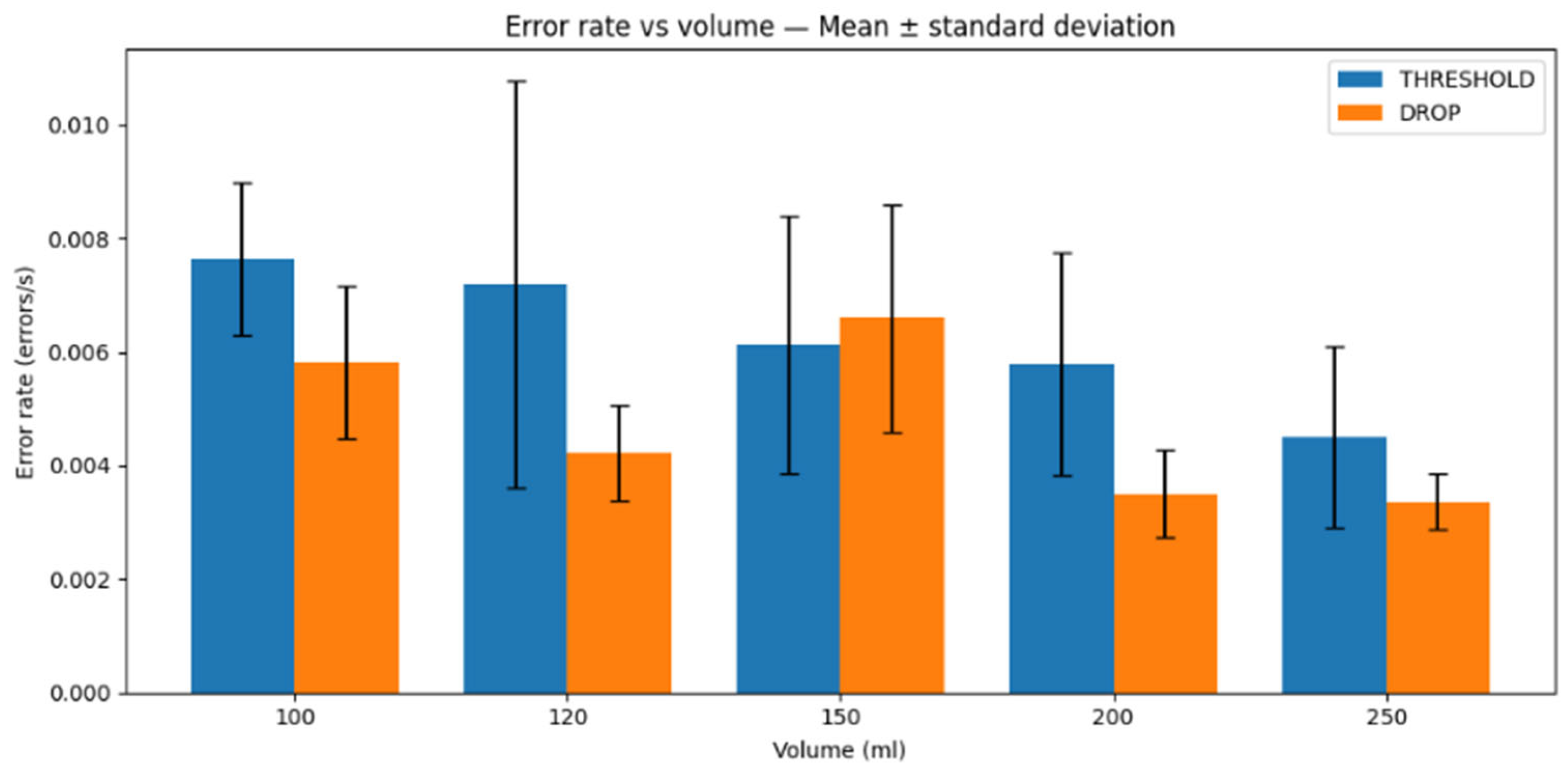

Figure 15 reports the error rate (errors/s) as a function of water volume for both schemes. Overall, the drop-based scheme exhibits lower mean error rates than the threshold-based scheme for most tested volumes, while the observed variability depends on the water volume and operating conditions. When considered together with the latency results, the drop-based method appears to be the preferred approach based on these two metrics.

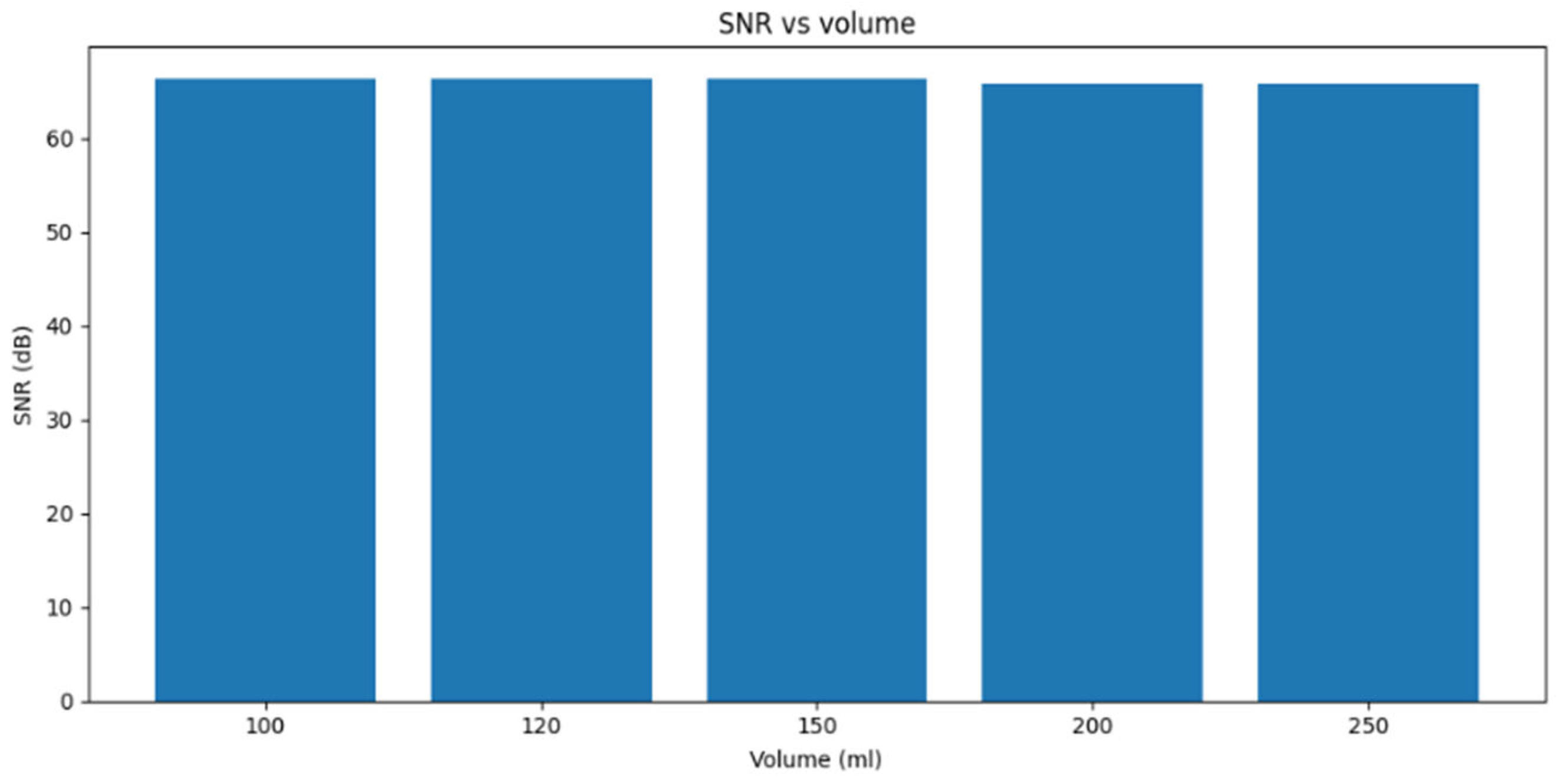

Figure 16 shows the measured signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) as a function of water volume (100, 120, 150, 200, and 250 mL). The results indicate a slight decreasing trend in SNR as the volume increases, from 66.43 dB at 100 mL to 65.79 dB at 250 mL. Although the absolute changes are small (≈0.64 dB across the entire range), this monotonic reduction is consistent with increased attenuation in larger water volumes while the limited variation suggests that advection dominates over diffusion under these conditions. These SNR measurements provide complementary evidence to the latency and error-rate results, supporting the interpretation that higher volumes lead to marginally less favorable channel conditions. (Here, SNR was computed in dB as the difference between the maximum frequency observed in a received message and the baseline frequency, normalized by the standard deviation of the baseline).