1. Introduction

The dynamic development of Additive Manufacturing (AM) technologies, which constitute a key pillar in the field of Rapid Prototyping, has introduced a paradigmatic shift in the approach to design and manufacturing across numerous engineering disciplines [

1,

2,

3]. Among the diverse AM techniques, Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) stands out due to its accessibility, low implementation cost, and a wide range of available polymer and composite materials [

4,

5,

6]. The ability to rapidly fabricate physical models, conduct cost-effective low-volume production, and, most importantly, create geometries of high complexity that are impossible or uneconomical to achieve with traditional methods has opened up unprecedented design possibilities. One of the areas where the potential of AM is particularly promising is the design of personalized audio systems, especially loudspeaker enclosures, where internal geometry and material properties play a crucial role in shaping the final acoustic characteristics [

7,

8,

9].

According to the fundamental principles of vibro-acoustics, an ideal loudspeaker enclosure should be an acoustically inert structure [

10,

11,

12]. Its primary function is to prevent the phenomenon of acoustic short-circuiting—the destructive interference of low-frequency sound waves generated in antiphase by the front and rear of the driver’s diaphragm—and to control parasitic self-resonances (i.e., unwanted vibrations of the enclosure’s panels at their natural frequencies, which color the generated sound). To achieve this goal, materials used in the traditional manufacturing of high-quality enclosures, such as Medium-Density Fibreboard (MDF) and High-Density Fibreboard (HDF), are selected for their specific combination of mechanical properties: high stiffness, high density, and, most importantly, a high internal damping coefficient. Internal damping is a measure of a material’s ability to dissipate mechanical vibration energy, primarily through conversion into thermal energy, which prevents the propagation of resonances within the structure and consequently minimizes the coloration of the generated sound [

13,

14].

In this context, a fundamental challenge arises for FDM technology. The basic thermoplastics used in this method, such as Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), possess mechanical properties that are fundamentally different from those of wood-based materials [

15,

16]. They are characterized by low density and, most significantly, negligible internal damping, which makes them inherently prone to resonance [

13,

17]. However, FDM technology offers a unique tool to compensate for these material shortcomings: the ability to precisely design the internal infill structure. The geometry (e.g., anisotropic-linear, quasi-isotropic-honeycomb, fully isotropic-Gyroid), density, and orientation of this internal lattice critically influence the resultant mechanical properties of the entire component [

15,

18]. The fabricated object is no longer a solid polymer but becomes a composite or cellular solid, whose overall stiffness, mass, and, crucially for this work, ability to dissipate vibration energy are a function of both the base material and its micro-architecture [

19,

20].

Despite the growing popularity of 3D-printed audio systems in hobbyist and prototyping environments, the available scientific literature shows a research gap concerning systematic, quantitative studies that compare the influence of key FDM printing parameters on the final vibro-acoustic properties of enclosures [

9,

21]. Existing research predominantly focuses on the analysis of the static mechanical properties (tensile strength, compression strength, elastic modulus) of printed components [

6,

15,

22]. neglecting their dynamic characteristics and damping capabilities, which are decisive parameters in audio applications. Although some studies have analyzed the vibro-acoustic properties of additively manufactured composites [

17], comprehensive comparative studies for commonly available materials and geometries are lacking.

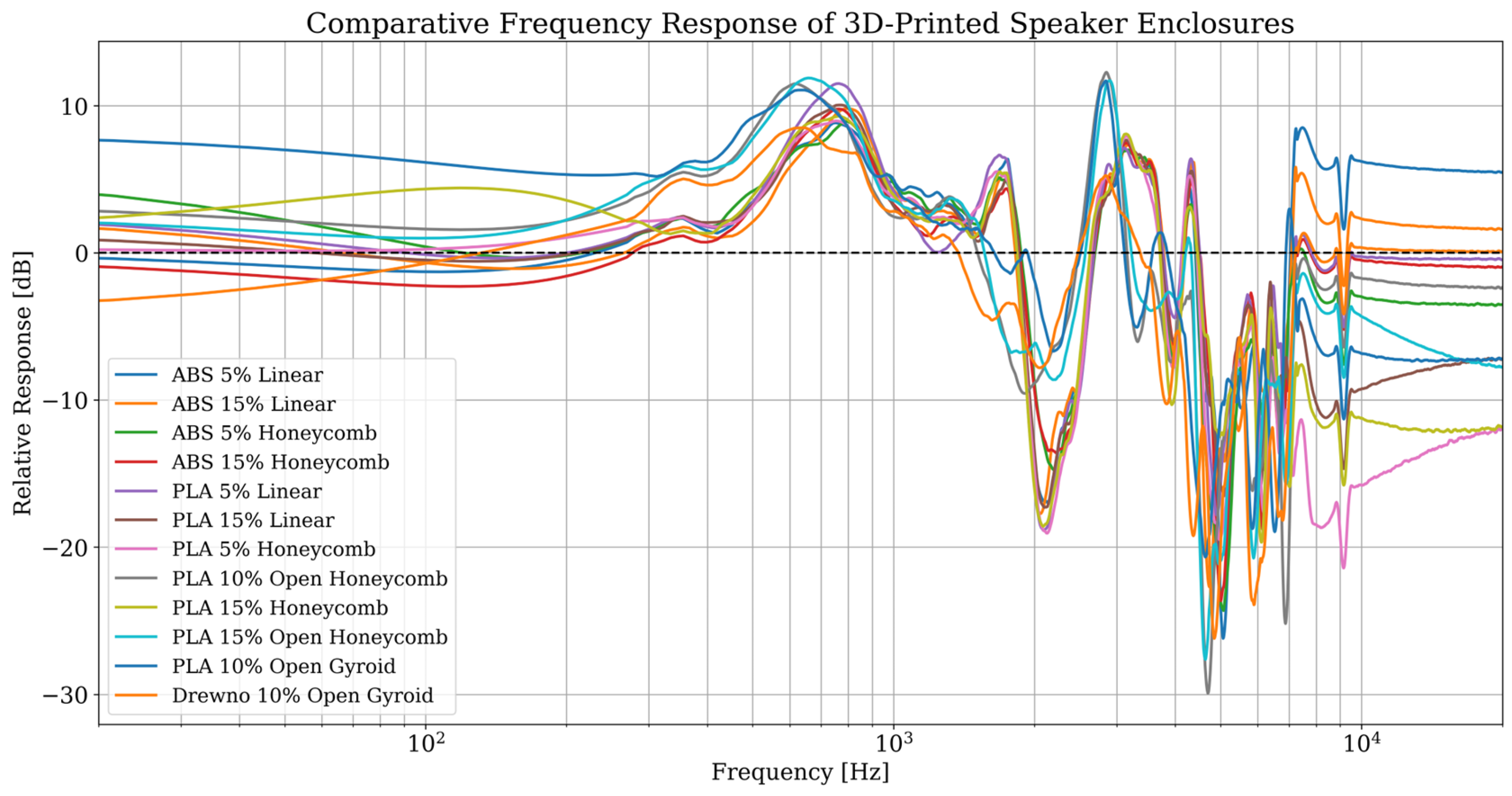

The primary contribution of this work is therefore threefold. First, it provides a comprehensive comparative dataset on the vibro-acoustic performance of commonly used FDM materials and advanced infill geometries, a topic currently underrepresented in the literature. Second, it presents a multi-faceted analysis methodology, combining relative frequency response, time-frequency analysis, and theoretical FEA modeling to create a holistic view of the system’s behavior. Third, it distills these complex findings into a set of practical engineering guidelines that can be directly applied by designers and engineers to optimize 3D-printed audio systems.

In response to this identified gap in the literature, the aim of this work is to conduct a systematic, empirical analysis and quantification of the influence of three fundamental FDM process parameters—filament type (PLA, ABS, wood-composite), infill geometry (linear, honeycomb, Gyroid), and its density—on the sound transfer characteristics of a loudspeaker enclosure. Through a comprehensive comparative analysis of twelve unique configurations, this study aims to create a set of quantitative design guidelines for engineers and designers, enabling the deliberate shaping of the desired sound signature and the minimization of unwanted resonances in personalized audio systems manufactured with additive technology [

9,

10].

2. Materials and Methods

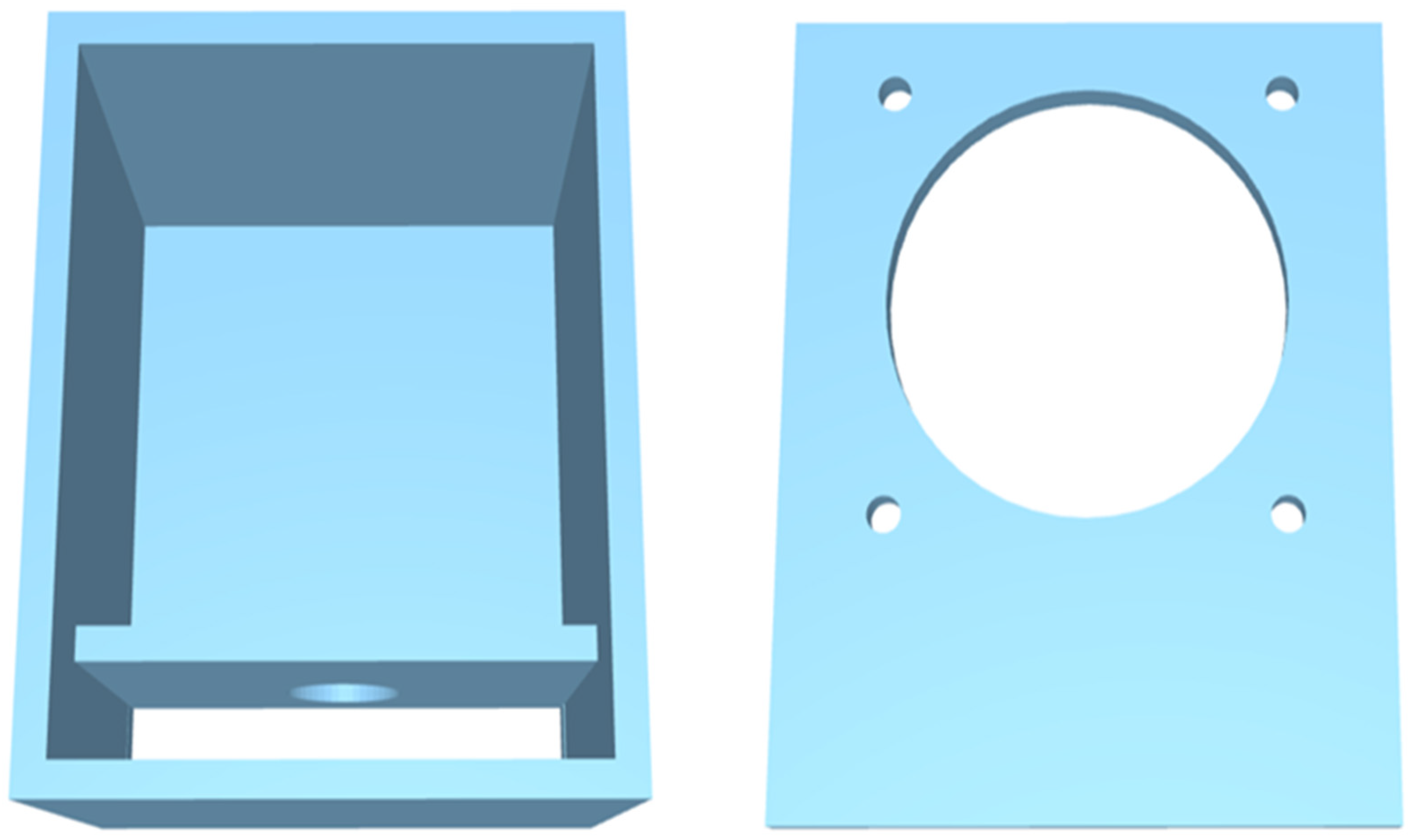

The object of this study was a loudspeaker enclosure with external dimensions of 90 × 110 × 65 mm and a constant wall thickness of 4 mm, designed in CAD software—Autodesk Inventor Professional 2023 (

Figure 1). Its geometry was intentionally shaped as an exponential horn. This design, in contrast to standard constructions aimed at minimizing coloration, was intended to intensify resonance phenomena, which enabled an easier and more precise assessment of the influence of the investigated parameters on the acoustic characteristics. All test specimens were fabricated using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) technology on a Creality Ender 3 type 3D printer.

To ensure consistency and comparability of the results, all models were printed with constant, unified process parameters, such as nozzle diameter (0.4 mm), layer height (0.2 mm), and printing speed (50 mm/s). The only variables were the process temperatures, adjusted to the specifics of the material (210 °C for the nozzle and 60 °C for the bed in the case of PLA; 240 °C and 100 °C for ABS) [

6,

23,

24]. A total of twelve unique enclosure configurations were prepared for the experiment, differing in three key variables: material, infill geometry, and density. A complete list of the test specimens is presented in

Table 1.

The three materials selected for this study—PLA, ABS, and a wood-composite—were chosen due to their distinct and well-documented mechanical properties, which are critical for vibro-acoustic behavior. The nominal, literature-based properties used for the theoretical modeling and qualitative discussion are summarized in

Table 2.

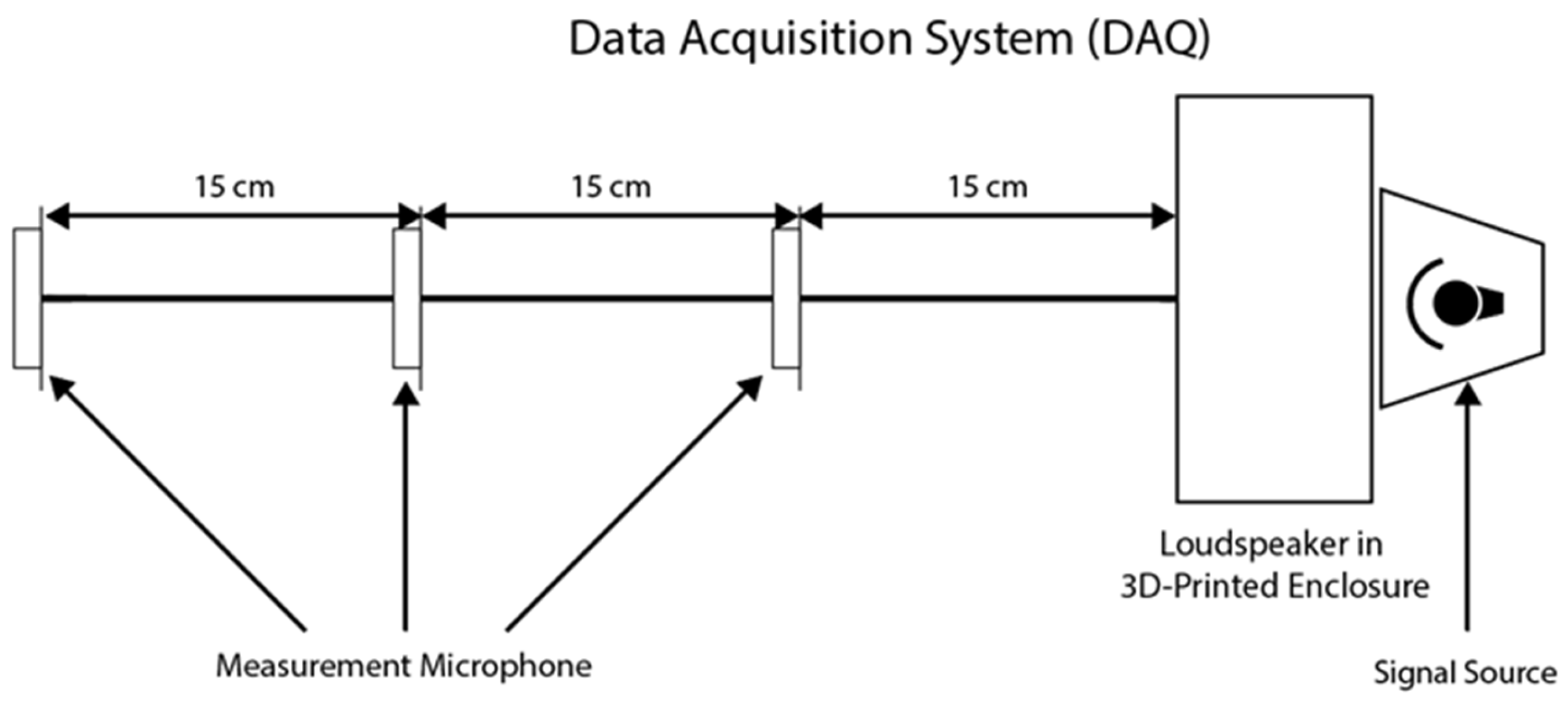

To evaluate the acoustic properties of each of the twelve configurations, a dedicated measurement setup was designed (

Figure 2). The measurements were conducted in a controlled environment with low background noise, using the same wide-band driver for each enclosure [

9]. An integrated condenser microphone of a single smartphone (iPhone X) was used for all audio signal acquisitions. The authors acknowledge that a non-calibrated, consumer-grade microphone lacks a flat frequency response and absolute accuracy, particularly in the high-frequency range. However, for a comparative study of this nature, the primary requirement is measurement consistency, not absolute metrological precision. By using the exact same device in a fixed position for all 36 measurements, any frequency response anomalies of the microphone are systematically applied to all samples and are effectively cancelled out during the calculation of the relative frequency response. While no formal calibration was performed, this approach ensures high repeatability, making the comparison between the specimens valid [

11].

A key element of the procedure was data acquisition at three defined distances from the sound source—15 cm, 30 cm, and 45 cm—which allowed for the verification of result consistency and the investigation of potential near-field effects [

12]. The 15 cm distance was specifically chosen as representative of the acoustic near-field, where the enclosure’s direct influence on the sound characteristics is most pronounced, while the additional measurements were conducted to verify the consistency of the observed trends. A 20-s excerpt of a musical piece with a wide frequency spectrum was used as the test signal, played back at a constant volume level. Additionally, a reference measurement was performed for the driver operating without any enclosure, which served as a baseline for all subsequent analyses.

The authors acknowledge that the employed measurement apparatus, utilizing a non-calibrated smartphone microphone, introduces a degree of absolute measurement uncertainty. However, the nature of this study is comparative, where the primary objective is to assess the relative performance differences between the configurations under identical conditions. To ensure the reliability of these comparisons, the repeatability of the measurements was a key focus. Each configuration was measured three times. An analysis of the standard deviation in the main resonance band (800–900 Hz) showed a variance of less than 0.5 dB across the repeated measurements. This high level of consistency confirms that the random error is minimal and that the observed differences between specimens are significant and attributable to the variations in their material and structure, thus allowing for valid engineering conclusions to be drawn.

The recorded audio files were then subjected to a multi-stage analysis pipeline in the Python 3.12 programming environment, which included automatic signal synchronization, relative frequency response calculation, and time-frequency (STFT) analysis. The first, crucial step was the automatic time-alignment of all recordings. This was achieved using a method based on the cross-correlation of onset strength envelopes, which allowed for the precise synchronization of the signals and enabled their further comparison [

11]. The primary method for quantitative evaluation was the relative frequency response analysis. This involved calculating the time-averaged power spectrum for each signal via FFT. Subsequently, to isolate the influence of the enclosure itself, the power spectrum of the signal from the tested configuration (driver + enclosure) was divided by the power spectrum of the reference signal (driver alone). This deconvolution operation, expressed in decibels, effectively isolates and quantifies the transfer function of the enclosure itself. The primary advantage of this relative response methodology is its ability to effectively cancel out the linear distortions originating from the non-ideal frequency responses of both the driver and the microphone. This allows for the precise isolation of the acoustic signature of the enclosure itself, making it a robust and accessible method for comparative analysis even without access to an anechoic environment or fully calibrated equipment. The result of this operation, expressed in decibels, effectively isolates and quantifies the influence of the enclosure itself on the transfer band. For in-depth visual analysis, a time-frequency analysis was also performed using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), generating spectrograms that allowed for the assessment of the decay times of parasitic resonances [

12].

To correlate the obtained acoustic results with the predicted mechanical properties, a theoretical model of the expected vibrations was also created. To provide a theoretical framework for interpreting the acoustic results, a predictive numerical model was developed. This FEA simulation was designed as a post-hoc explanatory tool, intended not to replace empirical measurement, but to serve as a fundamental instrument for explaining the physical mechanisms behind the observed acoustic phenomena and to correlate the measured sound response with the predicted mechanical behavior of the structures [

14,

17].

4. Discussion

It should be emphasized that this study is a parametric case study rather than a statistical analysis of a large population. Its objective is not to formulate universal laws for all 3D-printed enclosures but to identify and quantify the causal relationships and trends between specific parameters (material, geometry, density) and the resulting acoustic performance. The significance of the findings lies not in the sample size, but in the consistency and repeatability of the observed effects across all tested distances, as demonstrated in

Section 3. This approach allows for the formulation of reliable engineering conclusions regarding the influence of the investigated variables.

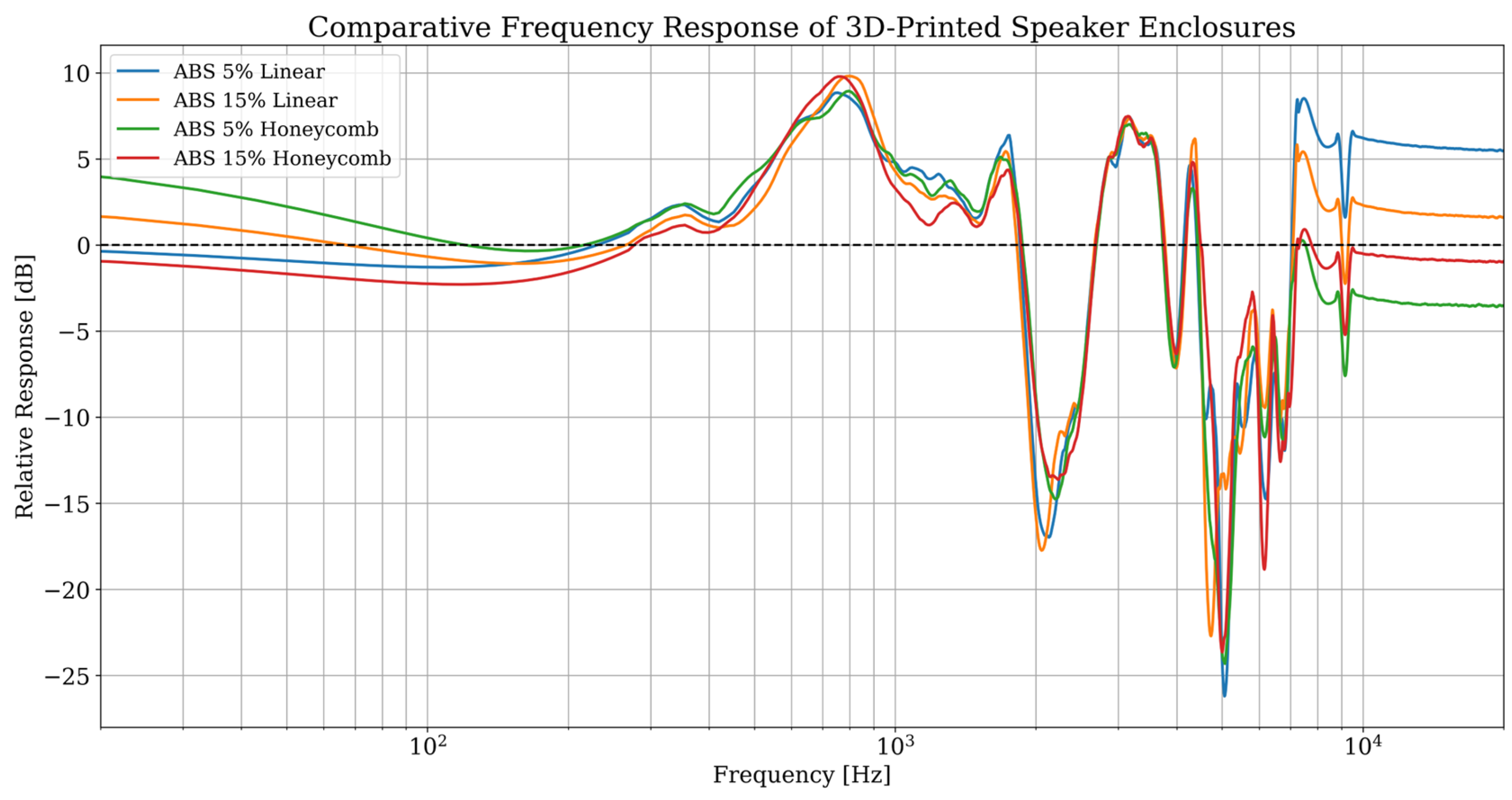

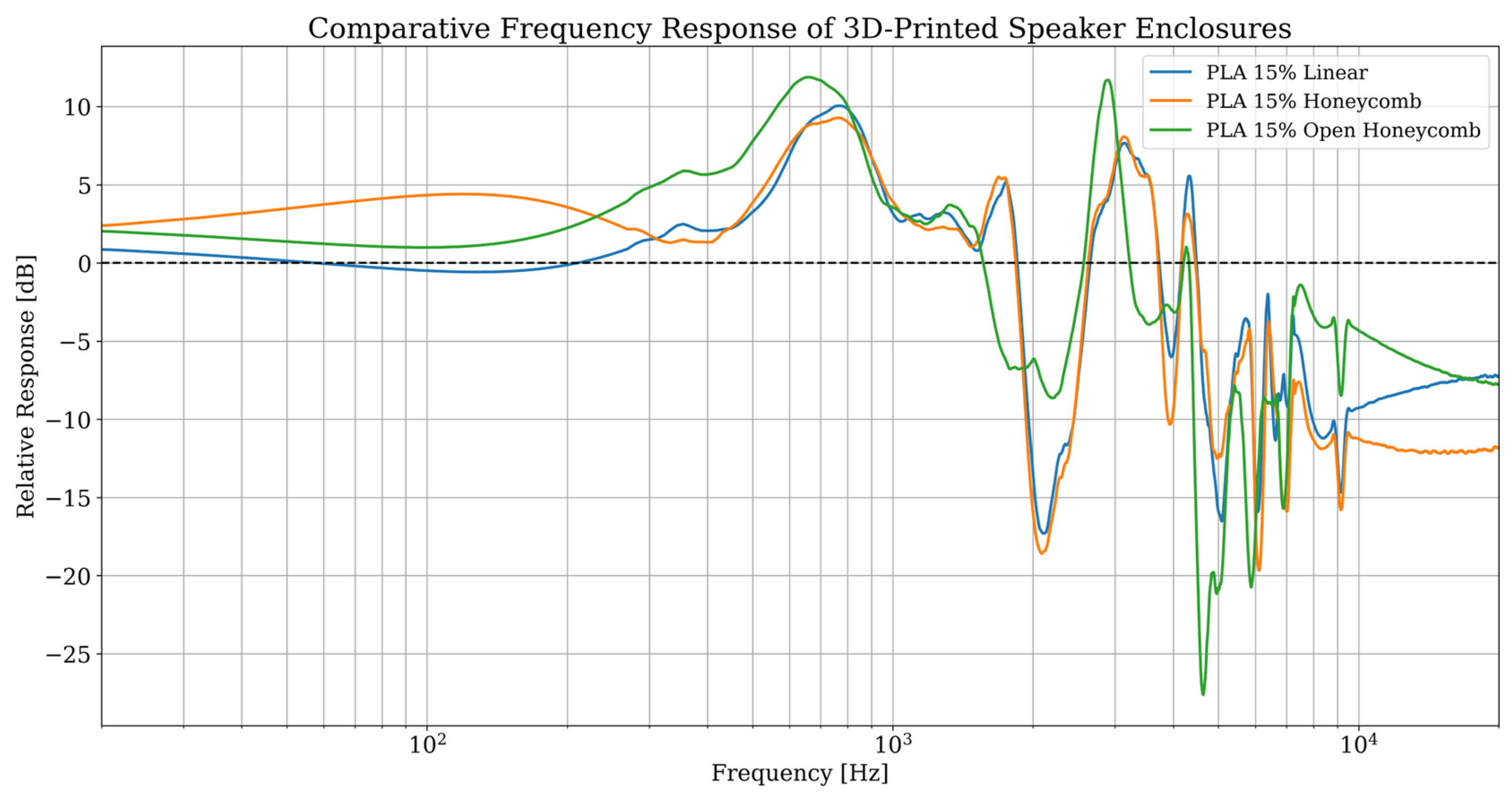

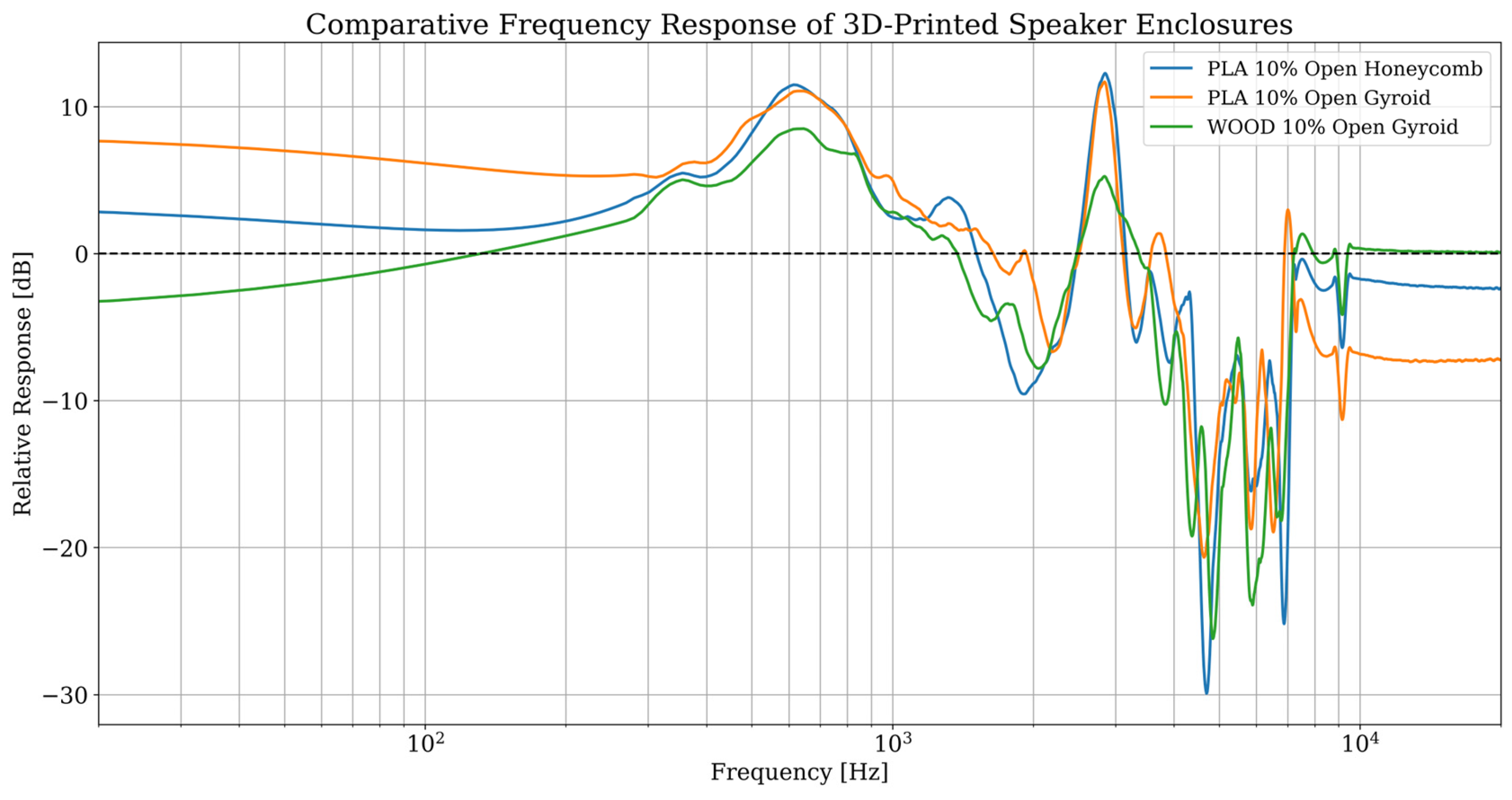

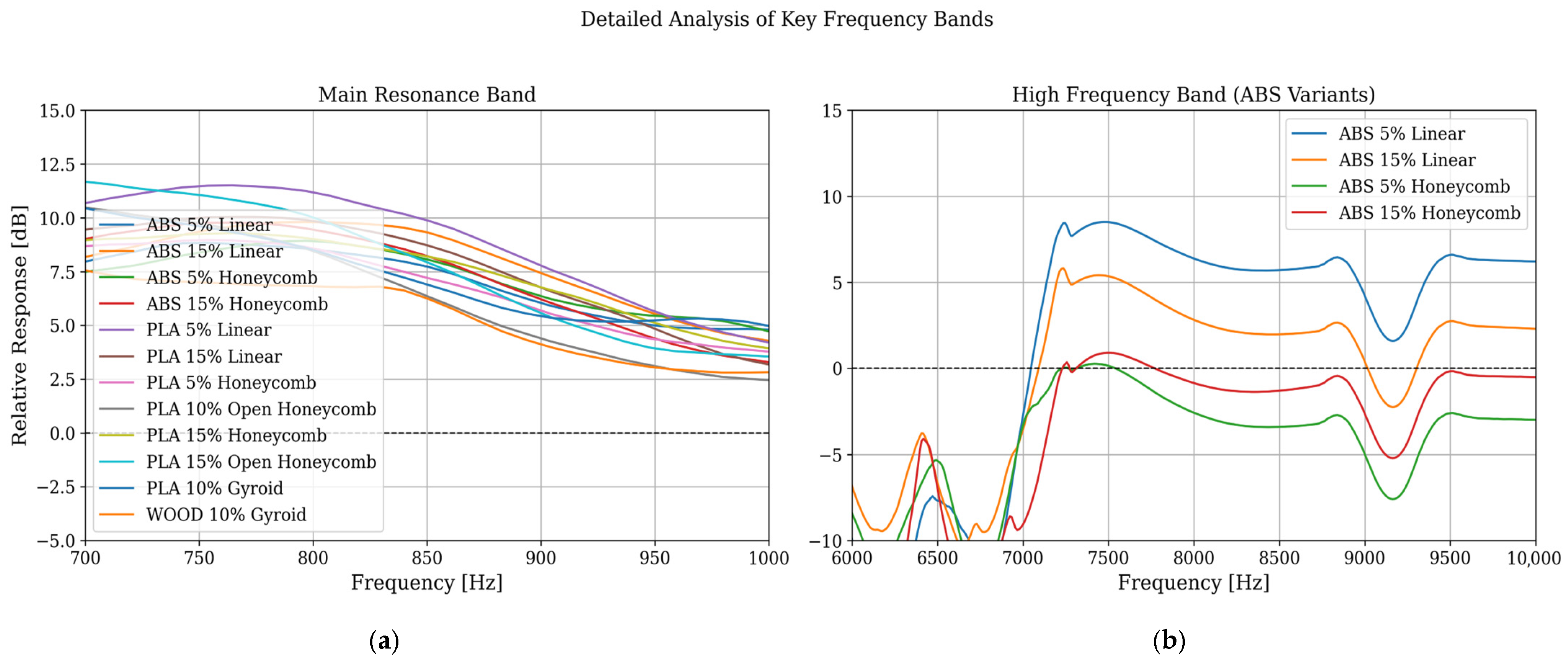

The detailed interpretation of the empirical results unequivocally confirms that the parameters of the Fused Deposition Modeling process have a fundamental and measurable impact on the vibro-acoustic characteristics of loudspeaker enclosures. The comparative analysis has shown that the internal damping coefficient of the material is a factor of critical importance. The juxtaposition of configurations based on PLA and the wood-composite, while maintaining an identical Gyroid geometry, indisputably revealed that the choice of material alone allowed for a reduction in the main resonance amplitude by approximately 4 dB. This serves as evidence that the low ability of the PLA filament to dissipate vibration energy constitutes a fundamental limitation, which even the most optimized internal structure cannot fully compensate for [

26,

27]. The high internal damping of the wood-composite not only enabled the reduction of the resonance peak but also the near-total elimination of coloration in the low-mid frequency band, which directly translated to the most neutral and uncolored sound. The superior damping performance of the wood-composite can be attributed to the physical mechanism of interfacial friction. The presence of wood particles within the PLA polymer matrix introduces a vast number of micro-interfaces. When the structure vibrates, micro-slips and friction occur at these particle-polymer boundaries, providing an effective mechanism for dissipating mechanical energy as heat. This process is largely absent in pure thermoplastics like PLA, whose low internal damping is primarily governed by viscoelastic polymer chain movements.

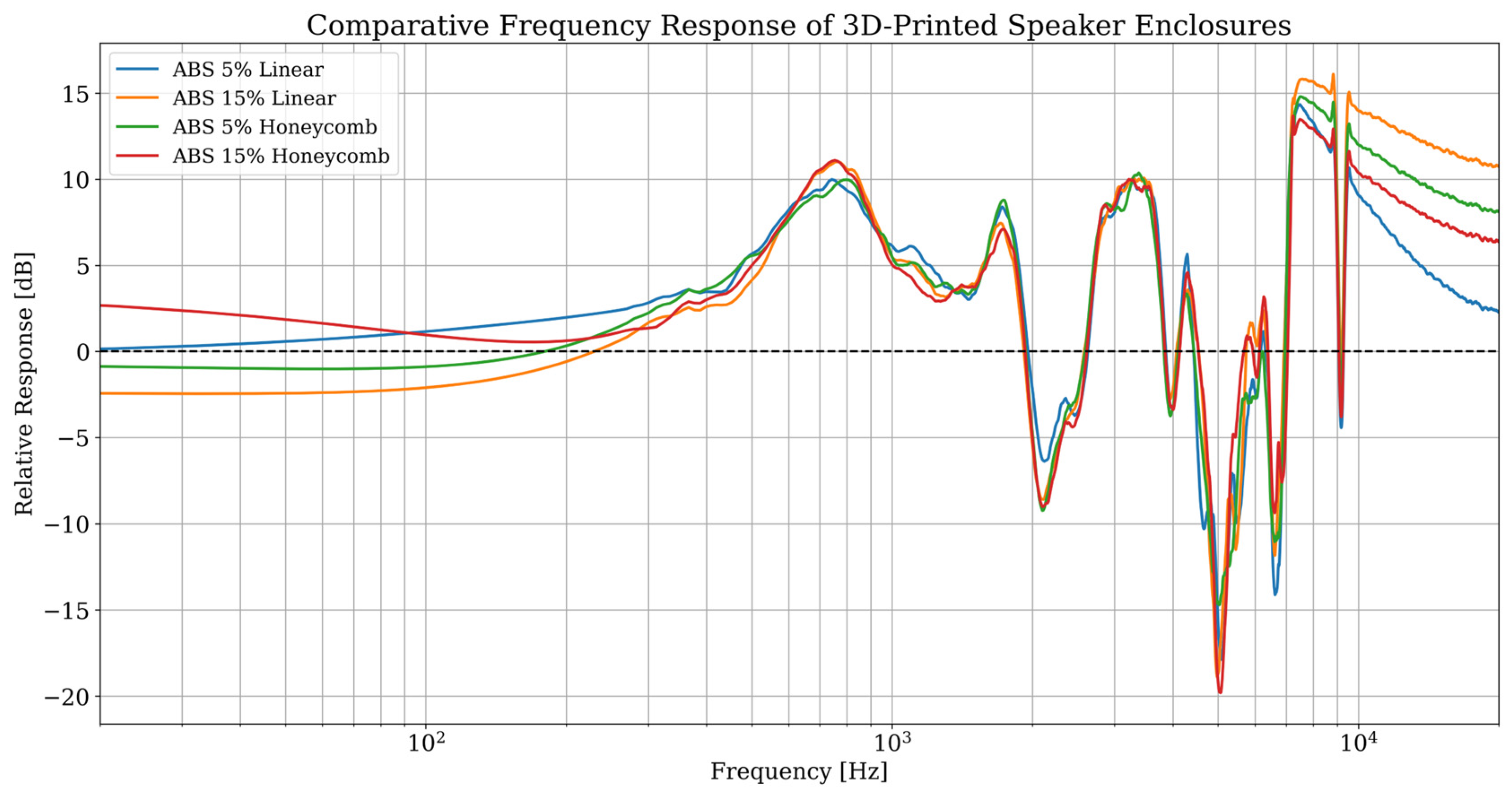

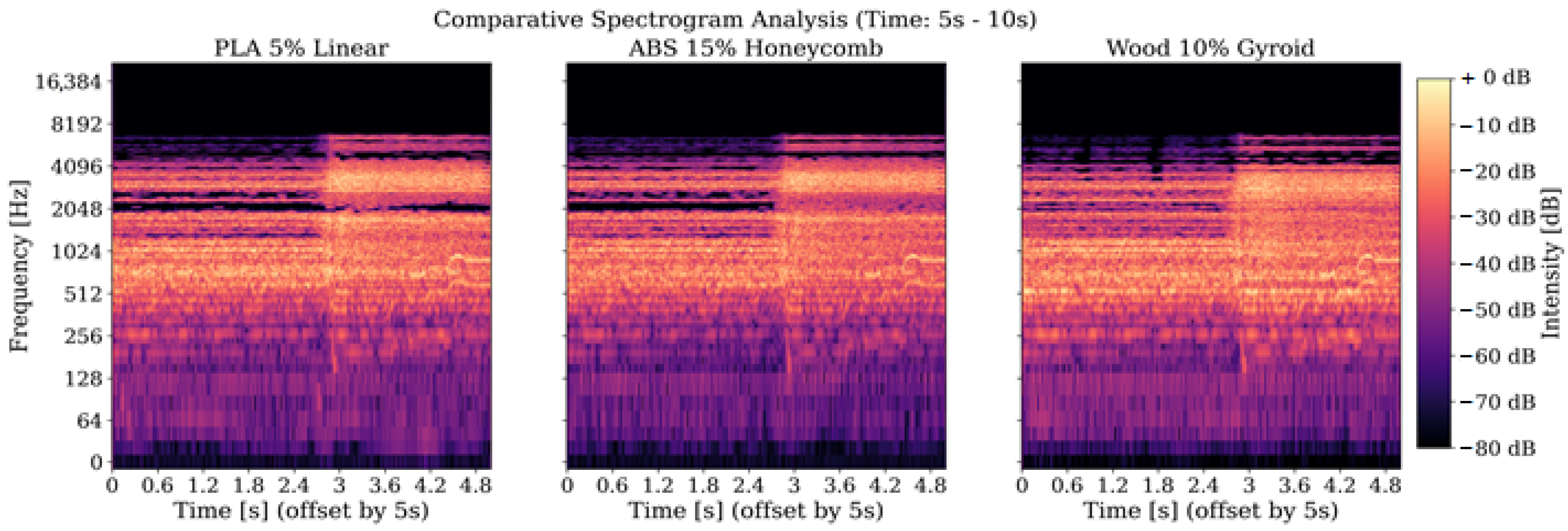

Equally significant was the role of the infill geometry, which functions as a structural energy dissipation mechanism, complementary to the damping properties of the material itself. The comparison of linear and honeycomb variants for the ABS material demonstrated that structures with higher isotropy (honeycomb) more effectively stiffen the enclosure panels and exhibit better control over resonances, especially in the high-frequency band. The reduction in the amplitude of narrow-band spectral peaks in this range, observed for the hexagonal structures, is an objective measure of a phenomenon that, in the psychoacoustic domain, corresponds to a decrease in undesirable artifacts such as “harshness” or a “metallic” sound character. The results for the advanced, fully isotropic Gyroid geometry further reinforce this conclusion. Its complex, three-dimensional micro-architecture proved to be the most effective at dissipating vibrational energy, which is confirmed both by the theoretical vibration model and by the visual analysis of the spectrograms, where the lowest level of parasitic resonance energy was recorded [

18,

19,

28]. The experiment also revealed the existence of complex interactions between the investigated parameters, demonstrating that simply increasing the infill density is not always an optimal strategy, and that the strategic placement of material within the structure to maximize its stiffness is of key importance [

7,

21].

The superior performance of the Gyroid geometry stems from its unique, triply periodic minimal surface structure. Unlike linear or honeycomb patterns, which can provide relatively straight paths for vibration propagation, the complex and continuously curved topology of the Gyroid forces mechanical waves to constantly scatter and change direction. This structural scattering is a highly effective passive mechanism for dissipating vibrational energy throughout the volume of the material, preventing the buildup of localized, high-amplitude standing waves that manifest as sharp resonance peaks.

5. Conclusions

The conducted research leads to the formulation of final conclusions of both a fundamental and an applicative nature. The most important of these is the finding that achieving high acoustic fidelity in 3D-printed loudspeaker enclosures is the result of a synergy between a material with high damping and an advanced, energy-dissipating internal geometry. The configuration made from the wood-composite with 10% Gyroid infill was unequivocally identified as the design with the best and most balanced acoustic properties among all tested variants. This work demonstrates that a deliberate and engineering-led selection of 3D printing parameters allows for the precise shaping of the vibro-acoustic characteristics, paving the way for the design of highly personalized and optimized audio systems [

9,

21]. The synthesis of the obtained empirical and theoretical results leads to the following main conclusions:

In vibro-acoustic designs, priority should be given to composite materials with a known, high internal damping coefficient, as the material properties are a factor of primary importance.

Simple, anisotropic infill geometries (e.g., linear) should be avoided in favor of isotropic structures (e.g., Gyroid), which provide higher structural stiffness and greater efficiency in dissipating vibrational energy.

The optimization of infill density should be considered in close connection with the chosen geometry, as their interaction is non-linear and its influence on the resultant mechanical characteristics is non-trivial.

The authors acknowledge certain limitations inherent in the employed methodology. The use of a non-calibrated smartphone microphone and the absence of an anechoic chamber mean that the presented results should be interpreted as a robust comparative analysis rather than a set of absolute, metrologically precise measurements. However, the high repeatability of the measurements, ensured by a consistent experimental setup, validates the conclusions drawn regarding the relative performance hierarchy of the tested configurations. This approach demonstrates that meaningful engineering insights can be derived using accessible and low-cost equipment, which is a significant finding in itself for the broader community of designers and hobbyists.

To further deepen the knowledge in this area, several potential directions for future research were identified. A primary avenue would be the analysis of other advanced composite materials. For example, incorporating short carbon fibers into a PLA or ABS matrix could significantly increase the material’s stiffness (Young’s Modulus) without a proportional increase in mass, potentially shifting panel resonances to higher, less audibly critical frequencies. Another direction is the validation of the obtained relative results using professional, calibrated measurement equipment (e.g., an IEC 60268-5 compliant microphone) within an anechoic chamber to obtain absolute, metrologically traceable data. Finally, the development of more sophisticated predictive numerical models (FEA) is crucial. Such models could incorporate material damping coefficients (structural damping) and be formally validated against empirical vibration measurements (e.g., using laser Doppler vibrometry) to create a truly predictive tool. Such a validated model would also allow for a sensitivity analysis to be performed, optimizing parameters like wall thickness or infill density in a virtual environment prior to the costly printing phase.