Discretization of Digital Controllers Comprising Second-Order Notch Filters

Abstract

1. Introduction

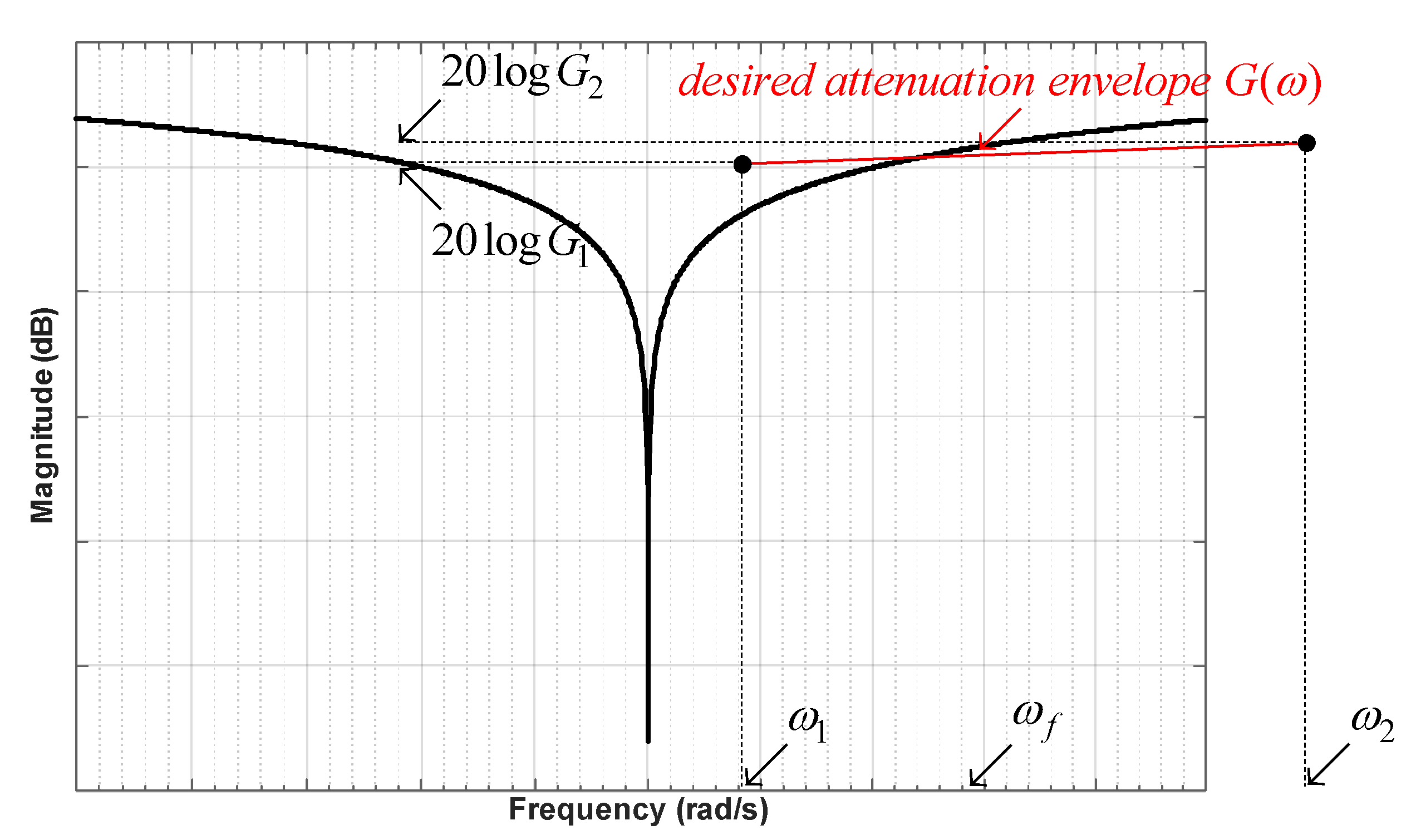

2. Notch Filter Under Consideration

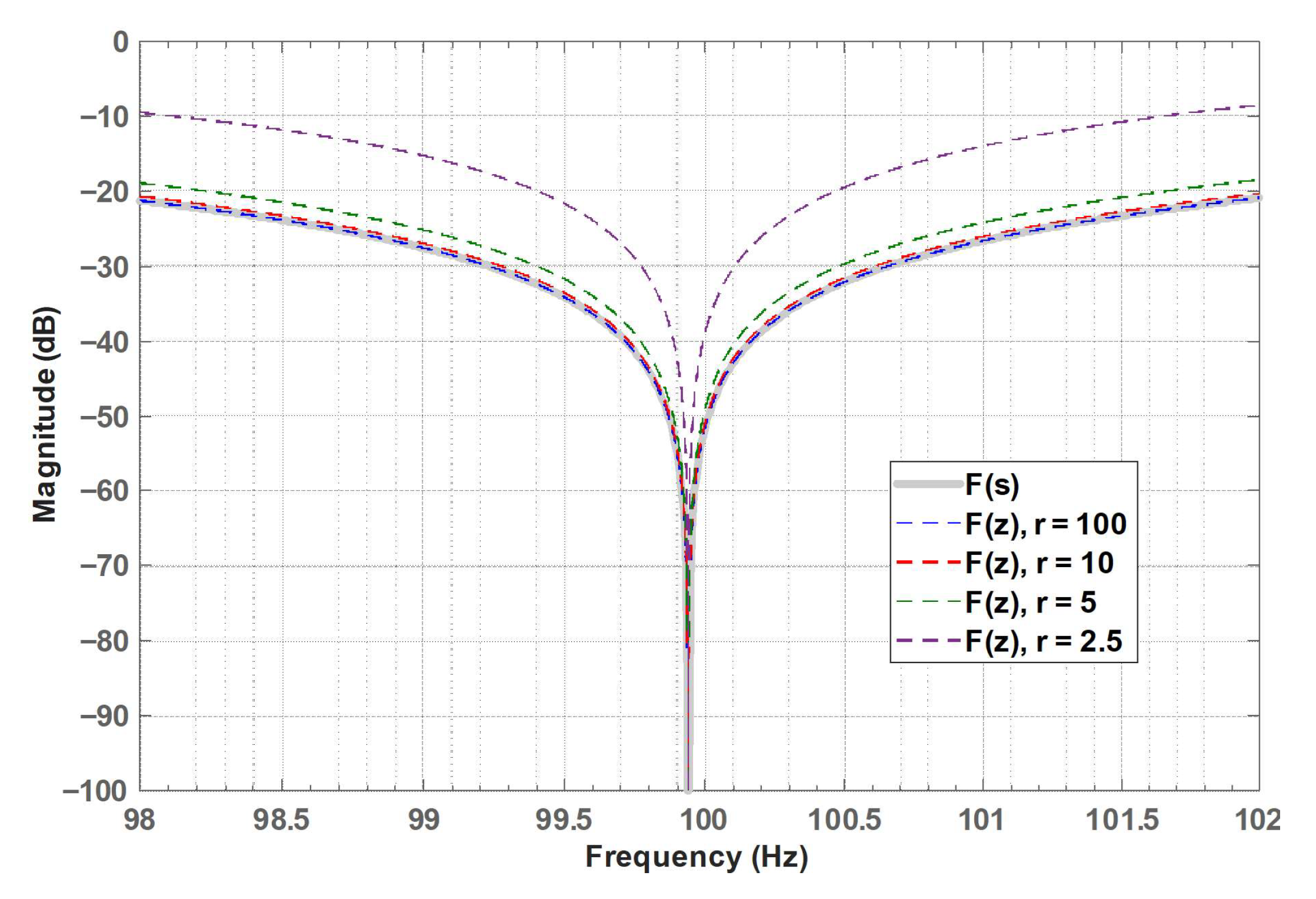

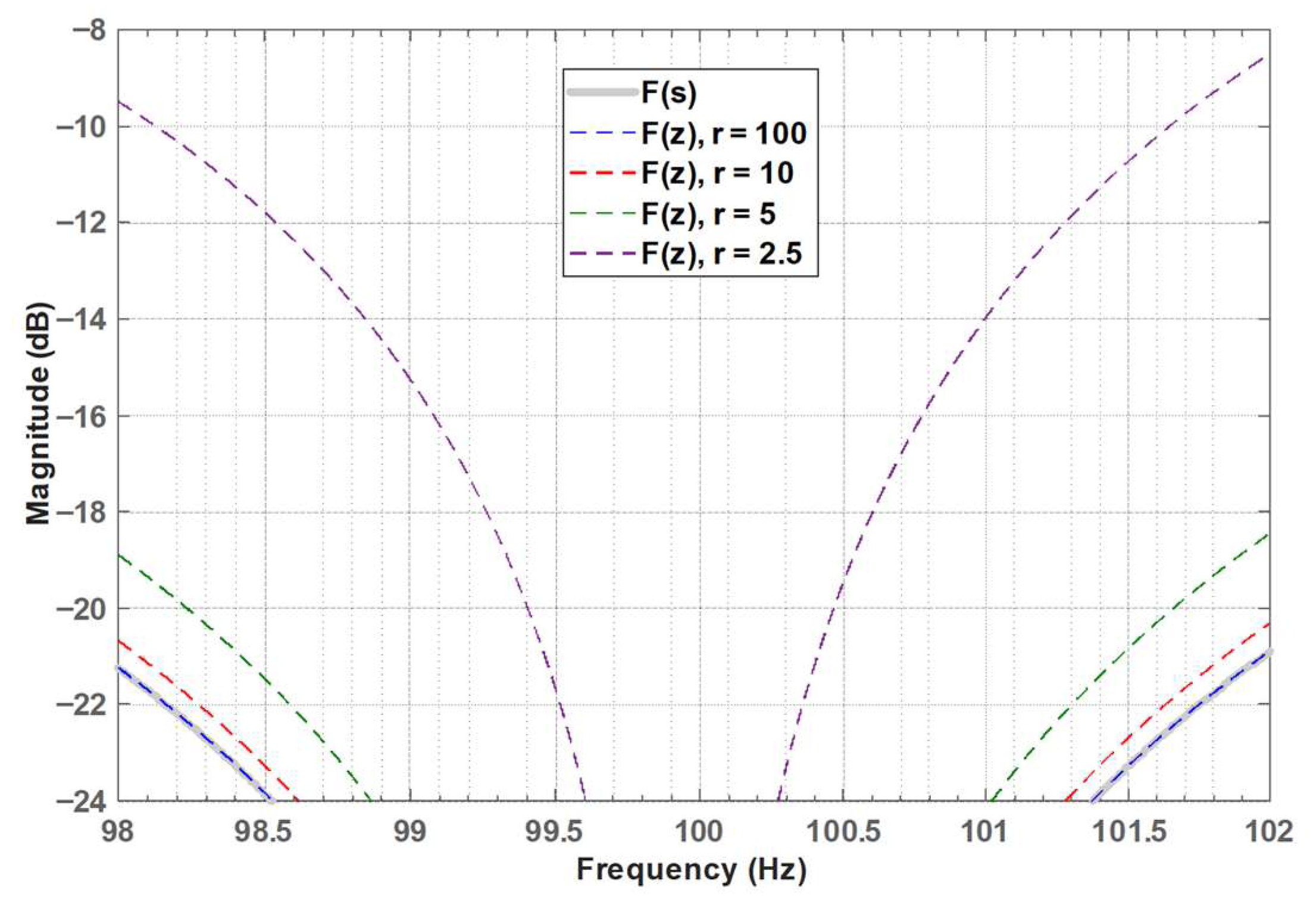

3. Discretization Issues

3.1. Discretization by Notch Frequency Prewarping

3.2. Discretization by Notch Frequency and Damping Factor Prewarping

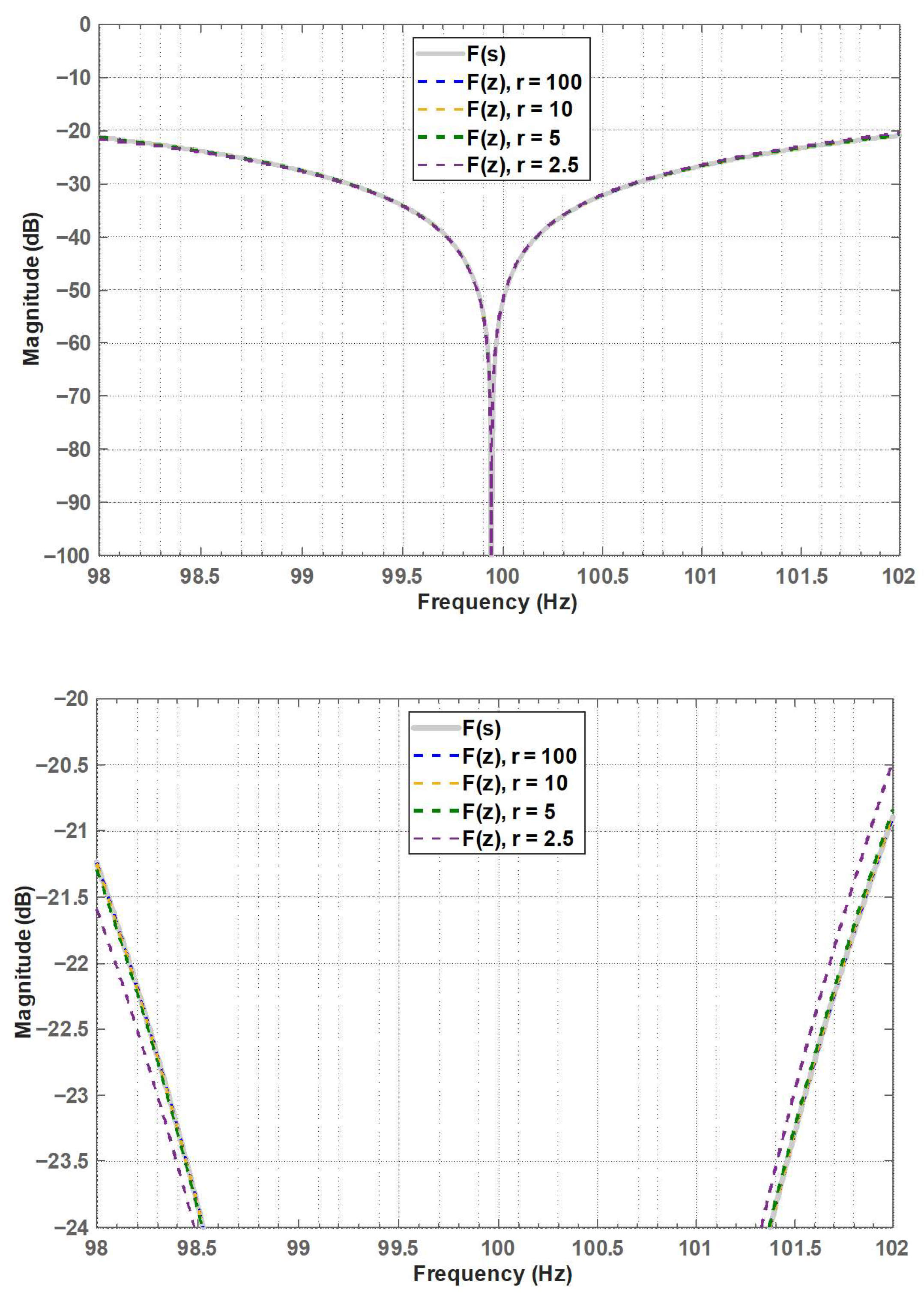

3.3. Discretization by Boundary Frequency Prewarping

4. Simulations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mori, T. Design of a servo control system using a notch filter for a flexible arm and its applications. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2013, 183, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Tsai, M.-S.; Hong, M.-Q.; Tang, P.-Y. Development of a novel tuning approach of the notch filter of the servo feed drive system. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2020, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Peng, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Dynamic Balance Correction of Active Magnetic Bearing Rotor Based on Adaptive Notch Filter and Influence Coefficient Method. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Hua, Z. Rotor Unbalanced Vibration Control of Active Magnetic Bearing High-Speed Motor via Adaptive Fuzzy Controller Based on Switching Notch Filter. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J. Modal Vibration Suppression for Magnetically Levitated Rotor Considering Significant Gyroscopic Effects and Interface Contact. Actuators 2025, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Ruan, X.; Wang, J.; Su, R.; Hu, L. Precise Control of Following Motion Under Perturbed Gap Flow Field. Actuators 2025, 14, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Zhao, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y. High-Frequency Harmonic Suppression Strategy and Modified Notch Filter-Based Active Damping for Low-Inductance HPMSM. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Muguro, J.; Njeri, W.; Doss, A.S.A. Adaptive Notch Filter in a Two-Link Flexible Manipulator for the Compensation of Vibration and Gravity-Induced Distortion. Vibration 2023, 6, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wei, J.; Wang, H.; Xiao, P.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, K. Analysis of the Notch Filter Insertion Position for Natural Frequency Vibration Suppression in a Magnetic Suspended Flywheel Energy Storage System. Actuators 2023, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Rahman, M.A. Comparative Analysis among Single-Stage, Dual-Stage, and Triple-Stage Actuator Systems Applied to a Hard Disk Drive Servo System. Actuators 2019, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Ivantysynova, M. Active Vibration Control of Swash Plate-Type Axial Piston Machines with Two-Weight Notch Least Mean Square/Filtered-x Least Mean Square (LMS/FxLMS) Filters. Energies 2017, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobori, Y.; Sun, Y.; Kobayashi, H. Selective Notch Frequency Technology for EMI Noise Reduction in DC–DC Converters: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, K.; Moallem, M. Synchronization and Control of a Single-Phase Grid-Tied Inverter under Harmonic Distortion. Electronics 2023, 12, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaza, A.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Said, M.; Ghoniem, R.M.; Barakat, A.F. Implementation of an Electronically Based Active Power Filter Associated with a Digital Controller for Harmonics Elimination and Power Factor Correction. Electronics 2022, 11, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, O.M.; Butt, T.M.; Ashfaq, M.H.; Talha, M.; Raihan, S.R.S.; Hussain, M.M. Simulative Study to Reduce DC-Link Capacitor of Drive Train for Electric Vehicles. Energies 2022, 15, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Huang, S.; Chen, X. Performance Improvement for Two-Stage Single-Phase Grid-Connected Converters Using a Fast DC Bus Control Scheme and a Novel Synchronous Frame Current Controller. Energies 2017, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taul, M.G.; Wang, X.; Davari, P.; Blaabjerg, F. Current reference generation based on next-generation grid code requirements of grid-tied converters during asymmetrical faults. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 3784–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aroudi, A.; Cid-Pastor, A.; Martinez-Salamero, L. Suppression of line frequency instabilities in PFC AC-DC power supplies by feedback notch filtering the pre-regulator output voltage. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2013, 60, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borafker, S.; Strajnikov, P.; Kuperman, A. Design of dual-notch-filter-based controllers for enhancing the dynamic response of universal single-phase grid-connected power converters. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S.; Hossain, M.J.; Lu, J.; Karimi-Ghartemani, M. An Enhanced DC-bus voltage-control loop for single-phase grid-connected DC/AC converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 5819–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Ghartemani, M.; Khajehoddin, S.A.; Jain, P.K.; Bakhshai, A. A systematic approach to DC-bus control design in single-phase grid-connected renewable converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 3158–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Luo, A.; Huai, K. Oscillation Suppression Method by Two Notch Filters for Parallel Inverters under Weak Grid Conditions. Energies 2018, 11, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, N.; Kinshin, A.; Gusev, A. Review of grid codes: Ranges of frequency variation. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2135, 20049. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, J.D. Design of audio parametric equalizer filters directly in the digital domain. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2011, 19, 1843–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.H.; Kim, Y.C.; De La Barra, B.A.L. Issues in linear feedback control design with notch filters. In Proceedings of the Chinese Control Conference, Harbin, China, 7–11 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, R.; Mandic, D.P.; Kolonic, D.H. Some potential pitfalls with s to z-plane mappings. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Istanbul, Turkey, 7–11 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yepes, A.G.; Freijedo, F.D.; Doval-Gandoy, J.; López, Ó.; Malvar, J.; Fernandez-Comesaña, P. Effects of discretization methods on the performance of resonant controllers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 1692–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direct Design of Discrete-Time Notch (or Resonant Gain) Filter in State Space or as Second-Order-Section. Available online: https://dsp.stackexchange.com/questions/97778/direct-design-of-discrete-time-notch-or-resonant-gain-filter-in-state-space-or (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kim, T.-I.; Han, J.-S.; Oh, T.-H.; Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Cho, D.-I.D. A new accurate discretization method for high-frequency component mechatronic systems. Mechatronics 2019, 62, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, L. Prewarping techniques in filter simulation by bilinear transformation. Sig. Process. 1983, 5, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strajnikov, P.; Kuperman, A. Selection of PI+Notch voltage controller coefficients to attain desired steady-state and transient performance in PFC rectifiers. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 6534–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levron, Y.; Canaday, S.; Erickson, R.W. Bus voltage control with zero distortion and high bandwidth for single-phase solar inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strajnikov, P.; Kuperman, A. DC link capacitance reduction in PFC rectifiers employing PI+Notch voltage controllers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 1, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapiden, K.; Shakhin, Y.; Thao, N.G.M.; Do, T.D. Digital disturbance observer design with comparison of different discretization methods for permanent magnet motor drives. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 100892–100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanarates, C.; Zhou, Z.; Aytac, A. Investigating the impact of discretization techniques on real-time digital control of DC-DC boost converters: A comprehensive analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mon-Nzongo, D.L.; Lin, S.; Ipoum-Ngome, P.G.; Lai, C.; Jin, T.; Rodriguez, J. A fast-digital current regulator based on matched pole-zero deiscretization for PMSM. Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 9371–9387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, A.K.; Kapat, S.; Banerjee, S.; Pal, J. Nonlinear analysis of discretization effects in a digital current mode controlled boost converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2015, 5, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminov, Y.; Kuperman, A. Simple linear DC link voltage controller to improve transient response of PFC rectifiers under stability and current quality constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 23–26 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Aminov, Y.; Kuperman, A. Design of P+Notch DC link voltage controllers for PFC rectifiers operating under prescribed phase margin and THD constraints. In Proceedings of the International IEEE Conference on Power Electronics Smart Grid and Renewable Energy, Hubli, India, 18–21 December 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Heldwein, M.L.; Klaß, S. Intelligent closed-loop fluxgate current sensor using digital proportional–integral–derivative control with single-neuron pre-optimization. Signals 2025, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analog | r = 100 | r = 10 | r = 5 | r = 2.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 [dB] | −21.2 | −21.2 | −20.7 | −18.9 | −9.5 |

| G2 [dB] | −20.9 | −20.9 | −20.3 | −18.4 | −8.5 |

| Analog | r = 100 | r = 10 | r = 5 | r = 2.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 [dB] | −21.2 | −21.2 | −21.25 | −21.3 | −21.6 |

| G2 [dB] | −20.9 | −20.9 | −20.88 | −20.84 | −20.45 |

| Analog | r = 100 | r = 10 | r = 5 | r = 2.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 [dB] | −21.2 | −21.2 | −21.2 | −21.2 | −21.2 |

| G2 [dB] | −20.9 | −20.9 | −20.9 | −20.9 | −20.9 |

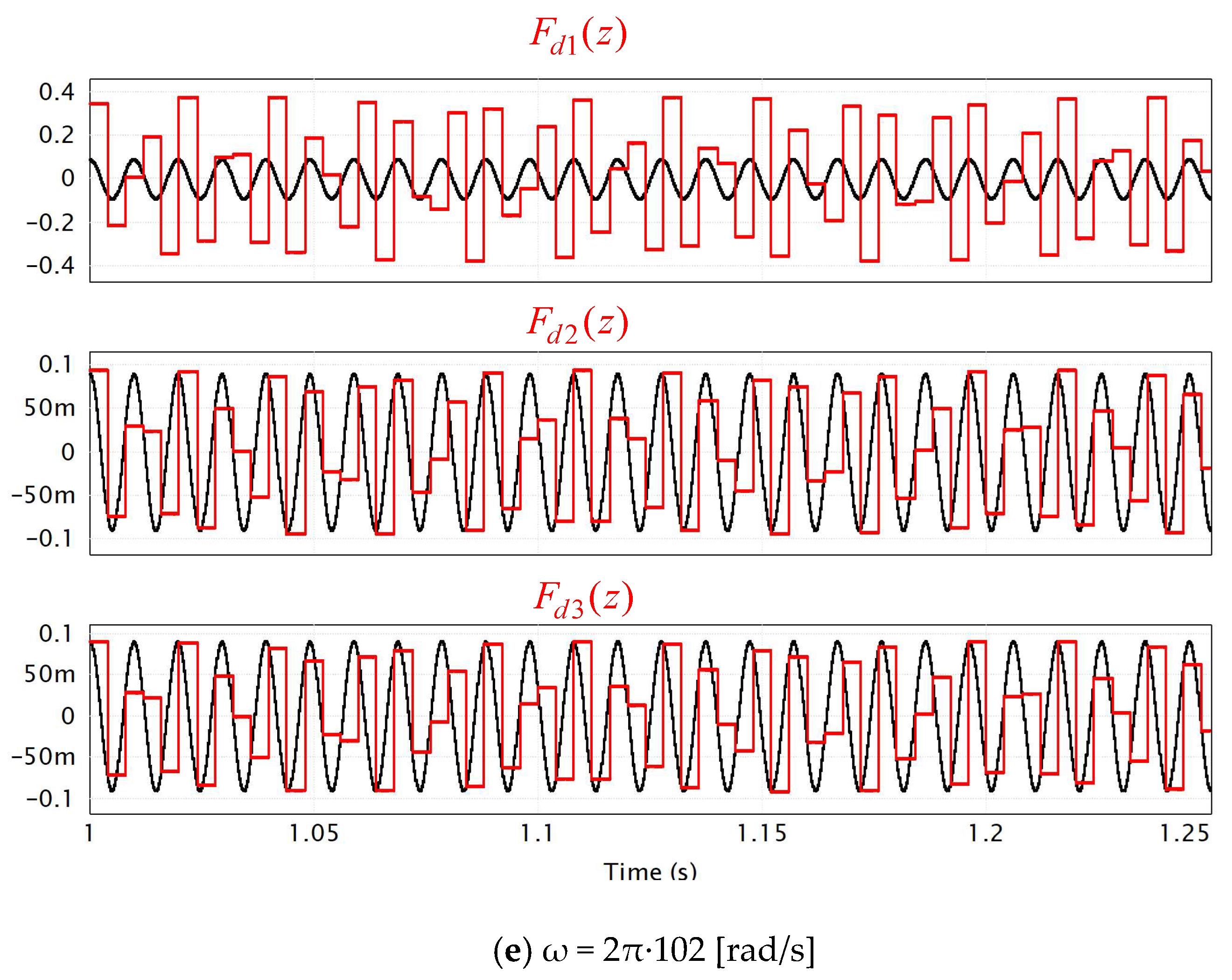

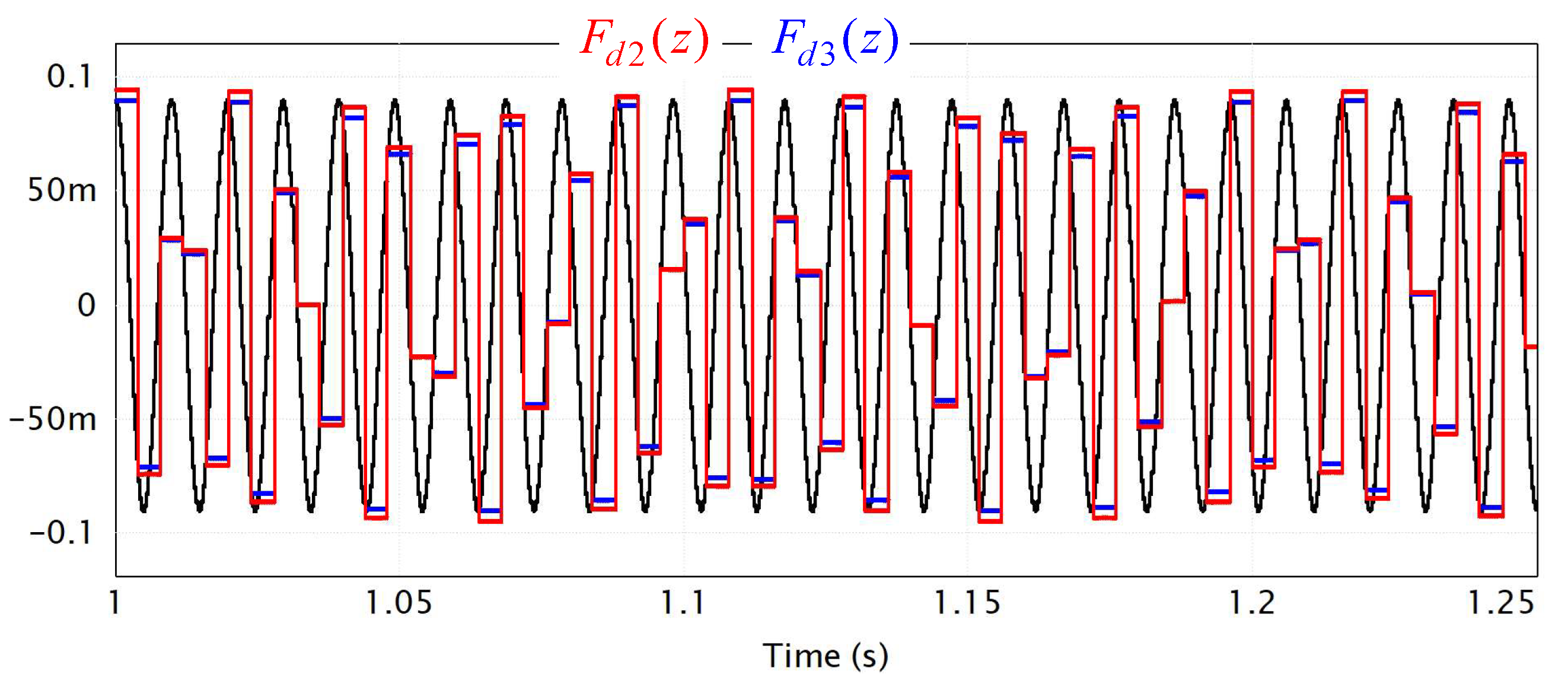

| ω [rad/s] | 2π∙98 | 2π∙99 | 2π∙100 | 2π∙101 | 2π∙102 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(s) | 0.087 | 0.042 | 0.0026 | 0.047 | 0.09 |

| Fd1(z) | 0.336 | 0.172 | 0.012 | 0.2 | 0.376 |

| Fd2(z) | 0.083 | 0.041 | 0.0027 | 0.048 | 0.095 |

| Fd3(z) | 0.087 | 0.045 | 0.0012 | 0.044 | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuperman, A. Discretization of Digital Controllers Comprising Second-Order Notch Filters. Signals 2025, 6, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/signals6040069

Kuperman A. Discretization of Digital Controllers Comprising Second-Order Notch Filters. Signals. 2025; 6(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/signals6040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuperman, Alon. 2025. "Discretization of Digital Controllers Comprising Second-Order Notch Filters" Signals 6, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/signals6040069

APA StyleKuperman, A. (2025). Discretization of Digital Controllers Comprising Second-Order Notch Filters. Signals, 6(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/signals6040069