1. Introduction

Amateur radio, commonly known as “ham radio” offers a diverse range of applications and goals for enthusiasts. The role of ham radio has decreased in daily communications, but in emergency situations offers a possible way to communicate [

1]. Another possible application is to introduce students to STEM in a practical way [

2].

However, regulatory authorities and experts emphasize one critical objective: the study of radio wave propagation. Propagation research [

3,

4] through amateur radio plays a vital role in understanding how radio signals travel, interact with the atmosphere, and behave under various conditions.

The basic element of ham radio operation is the contact, in which the mandatory parts are the exchange of the callsigns and the signal reports. Signal report is the characterization of the received signal, which can contain the signal strength and other properties (signal purity, modulation quality, signal fluctuation, etc.). This information provides valuable data for studying the varying properties of radio wave propagation [

5].

A particularly popular subfield of the hobby is DXing, where the objective is to establish contacts with distant stations across continents or even globally. Such DX contacts are typically brief, with communication serving primarily to confirm the successful establishment of the connection.

Ham radio operators employ various modulation modes to facilitate voice, Morse code, and data communication [

6]. In recent years, data-based contacts have gained significant popularity, largely due to advancements in digital technology, such as computers, sound cards, and specialized software. These highly efficient digital modes have revolutionized the DXing segment of ham radio by offering enhanced performance in low-signal environments. Another promising direction is the use of remotely accessible stations, which allows installations in low-noise rural environments and thereby improves the reception of weak signals [

7].

FT8, or Franke–Taylor design, 8-Frequency Shift Keying, is a digital communication mode developed in 2017 by Joe Taylor (K1JT) and Steven Franke (K9AN) [

8,

9]. It has rapidly gained popularity within the amateur radio community due to its exceptional efficiency, especially in low-power and noisy environments. One of FT8’s key features is its ability to perform automated, computer-assisted communications, allowing for rapid exchanges of minimal data, including callsigns, signal reports, and geo-locations. Although another minimalistic ham radio mode, WSPR [

10], was specifically designed to support real-time propagation studies, the widespread popularity of FT8 has made it an equally powerful and highly practical tool for propagation research. Although the transmitters used as beacons do not emit continuous signals, their large number compensates for this limitation and enables a finer spatial resolution.

2. Background

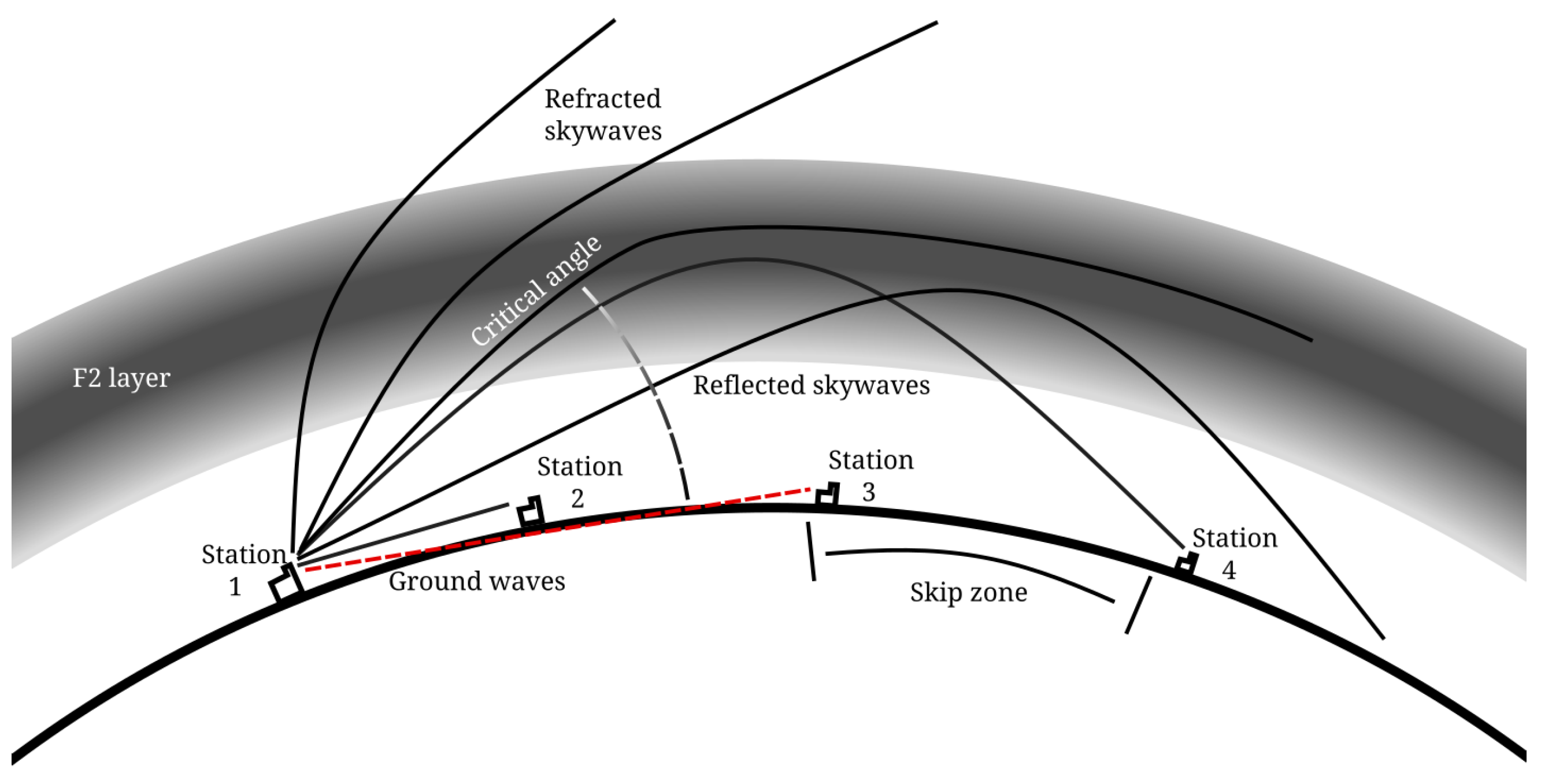

HF radio signals, typically in the range of 3–30 MHz, can propagate over long distances through two primary mechanisms: ground wave and skywave propagation. Ground waves travel along the Earth’s surface and are influenced by terrain conductivity and frequency; they are most effective at lower HF frequencies and gradually attenuate with distance due to surface absorption. While ground waves provide reliable communication up to several hundred kilometers, they are insufficient for global coverage. Long-distance HF communication relies on skywaves, which are refracted—or, at certain angles, reflected—by the ionosphere. The ionosphere is a region of the upper atmosphere, starting at around 50 km above the surface, that contains charged particles produced by solar ultraviolet and X-ray radiation. Skywave propagation enables signals to “hop” between the ionosphere and the Earth’s surface, allowing communication over thousands of kilometers. Multiple hops can occur, extending coverage to intercontinental distances.

The ionosphere is conventionally divided into three primary layers—D, E, and F—each with distinct propagation characteristics. The D layer is located roughly between 50 km and 90 km, is present during daylight hours, and causes significant signal absorption, especially at lower HF frequencies. At night, it dissipates, allowing lower frequencies to propagate much farther. The E layer is found between 90 km and 120 km, can refract HF waves, and occasionally supports sporadic E propagation, producing strong, short-lived paths over medium distances (typically 1000–2000 km). The F layer is the highest ionospheric region, from about 150 km upward, and is often split into F1 and F2 layers during the day. The lower surface of the F2 layer behaves much like the boundary between two optical media with different refractive indices, producing effects analogous to those observed in optics. A critical angle can always be defined, depending on both the conditions within the F2 layer and the operating frequency. When a skywave enters the F2 layer at an angle greater than this critical value, it is refracted away and fails to return to Earth, making reception impossible. Conversely, if the incidence angle is smaller, the wave is refracted back toward the ground. where it can reflect and continue with additional hops.

The critical angle, together with the actual height of the F2 layer, determines the skip distance. Stations located closer than this distance cannot be reached via F2 propagation. Note that close stations can reach each other with ground waves, with limited range, typically under 100 km. The F2 layer is crucial for long-distance HF communication, as it remains ionized even at night and can reflect higher HF frequencies over 3000 km per hop [

11]. In

Figure 1 Station 1 can reach the nearby Station 2 with ground waves. Station 3 is at the closest point, which cannot be reached with ground waves. Station 4 is the closest one, which can be rached with skywaves. A skip zone is formed between Station 3 and 4.

Ionospheric conditions—and thus HF propagation—vary with the time of day, season, and solar activity. Daytime ionization enhances higher frequency propagation but increases D-layer absorption, while nighttime favors lower frequencies. Solar flares, geomagnetic storms, and the 11-year solar cycle all significantly impact propagation, sometimes enhancing communication paths and at other times causing complete HF blackouts [

5,

12,

13].

An ionosonde is a specialized radar system used to study the ionosphere by transmitting short pulses of high-frequency (HF) radio waves vertically and recording the time delay and intensity of the echoes reflected from ionospheric layers [

14]. The output of an ionosonde is an ionogram, a two-dimensional plot of virtual height versus frequency, which visually represents the reflective properties of the ionosphere at a given time and location. Distinct traces in an ionogram correspond to reflections from different ionospheric layers, allowing researchers to identify parameters such as the maximum usable frequency (MUF) and the lowest usable frequency (LUF) for radio communication. Ionograms are widely used for both scientific research and practical applications, including shortwave frequency planning, space weather monitoring, and validation of ionospheric models [

15,

16]. Ionosondes have some downsides as well: they are expensive to install and maintain, requiring dedicated infrastructure, calibration, and skilled personnel, which restricts their availability to relatively few sites worldwide. This sparse geographic coverage limits their ability to capture global ionospheric variability, especially over oceans and remote regions. Furthermore, ionograms represent only vertical soundings at a single location and time, meaning that they cannot directly measure oblique propagation paths relevant for long-distance HF communication without additional modeling or interpolation.

Ionospheric models are mathematical and empirical frameworks used to describe and predict the state of the ionosphere and its effect on radio wave propagation. These models integrate parameters such as electron density profiles, ionospheric layer heights, and critical frequencies, often derived from both ground-based (ionosondes, GPS TEC measurements) and satellite observations. Widely used examples include the International Reference Ionosphere (IRI), which provides monthly median conditions globally, and physics-based models such as the Thermosphere–Ionosphere–Electrodynamics General Circulation Model (TIE-GCM), which simulate ionospheric behavior under varying solar, geomagnetic, and atmospheric conditions. Hybrid models, combining empirical climatology with real-time data assimilation, are increasingly employed to capture both long-term trends and short-term variability caused by space weather events [

17].

Prediction of ionospheric conditions is essential for planning and optimizing HF communication, navigation systems, and over-the-horizon radar operations. Forecast systems use models to estimate parameters like the Maximum Usable Frequency (MUF) and Lowest Usable Frequency (LUF) along specific radio paths, considering factors such as time of day, season, solar cycle phase, and geomagnetic activity [

18].

Weak Signal Propagation Reporter (WSPR) has emerged as a powerful tool for ionospheric and HF propagation research [

19] due to its ability to detect and decode extremely weak signals—down to about −28 dB in a 2.5 kHz bandwidth. Operating on standardized, time-synchronized transmissions, WSPR provides a globally coordinated network of transmitting and receiving stations that continuously exchange low-power beacons on multiple amateur radio bands. The resulting datasets include precise information on transmitter and receiver locations, operating frequencies, time stamps, and signal-to-noise ratios, enabling detailed analysis of propagation paths, diurnal and seasonal trends, and the effects of solar and geomagnetic activity. Unlike traditional propagation experiments that require dedicated high-power transmitters and specialized receivers, WSPR leverages the participation of thousands of amateur operators worldwide, creating a massive, decentralized measurement network [

10,

20].

FT8 generally exhibits higher activity levels than WSPR because it is more rewarding and engaging for amateur radio operators. While WSPR is primarily a one-way beacon mode designed for propagation monitoring, FT8 enables two-way contacts, allowing operators to exchange signal reports, locations, and confirmations toward awards such as DXCC or grid square achievements. This interactive nature attracts a much larger user base and sustains high levels of global participation across all amateur HF bands. As a result, FT8 produces significantly more transmission and reception events than WSPR, generating larger datasets with broader geographic and temporal coverage. For researchers, this abundance of data provides greater statistical power, higher spatial resolution, and more opportunities for advanced processing and analysis of ionospheric and HF propagation behavior.

3. Architecture

3.1. The FT8 Protocol

The FT8 protocol [

21] allows for two participants to exchange their callsigns, their geolocations, and the received signal-to-noise ratios in a compact form. Callsigns can consist of letters and numbers with some rules and restrictions. Special prefixes or suffixes with a/(slash) symbol can extend the callsign in some cases.

The geolocation is encoded in 4 letter Maidenhead format, which is represented as two letters and two digits. Each combination defines a rectangle of 2 degrees (longitude) by 1 degre (latitude).

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is expressed on a dB scale from −30 to +32 dB. To reduce the number of required bits, only even numbers are used.

An FT8 contact between the station of Alice (with callsign AL1CE) and the station of Bob (with the callsign B0BB) consists of the following messages:

CQ AL1CE JN87

AL1CE B0BB IO83

B0BB AL1CE -15

AL1CE B0BB R-17

B0BB AL1CE RRR

AL1CE B0BB 73

B0BB AL1CE RR73

Message type 1 is a general call (CQ) from Alice, which means she is ready to make contact. JN87 is the Maidenhead grid square of Alice. Note that an optional designator can be applied between the CQ and the callsign, marking a target area or a special event.

Bob can answer this with message type 2. This message contains the callsign of both stations and the grid square of Bob.

Then Alice can reply with message type 3. This message type contains the two callsigns and the signal report from Alice (−15 dB).

Message type 4 contains the callsigns, the signal report from Bob (−17 dB), and an acknowledgement for the previous message (R, short for roger).

Then Alice acknowledges the contact with message type 5 (RRR, short for roger, roger, roger).

Message type 6 makes the contact complete, where the participants say goodbye with 73 (meaning Best Regards). An alternative shorter version for types 5 and 6 is message type 7 (RR73).

Each message is represented as a 77-bit packet, then with Cyclic Recundancy Check (CRC) and Forward Error Coding (FEC), a 174-bit codeword is generated. Codewords are transmitted using 8-tone CPFSK (Continuos Phase Frequency Shift Keying) with 6.25 Hz tone separation and 6.25 symbols/s. One FT8 message takes approx. 50 Hz bandwidth, therefore a usual 2800 Hz ham radio SSB voice channel can handle 56 parallel communications. Note that decoding partially overlapping messages is possible. Unlike conventional voice communication, which requires separate frequencies for each transmission to prevent interference, FT8 operates on a single, fixed frequency within each ham radio band, enabling multiple simultaneous communications and data collection through passive listening and decoding.

3.2. Hardware Architecture

The first key design decision in this research was the selection of the appropriate frequency band or bands to study. The two main criteria guiding this choice were simplicity and the ability to collect the largest amount of relevant data. While the most comprehensive approach would have been a multi-band setup with multiple receivers and antennas operating simultaneously, such a system would have been overly complex. An alternative option was to use a single receiver with a time-multiplexed band-switching system, though this would still involve certain trade-offs. Ultimately, prioritizing simplicity, a single-band system was chosen.

The worldwide available HF bands are 1.8 MHz (160 m), 3.5 MHz (80 m), 7 MHz (40 m), 10 MHz (30 m), 14 MHz (20 m), 18 MHz (17 m), 21 MHz (15 m), 24 MHz (12 m), and 28 MHz (10 m). The nature of the different bands are different and each of them would provide interesting research data. The available installation space places a clear limitation on antenna size and, consequently, on the lowest usable frequency. A half-wavelength dipole can serve as a reference point for antenna dimensions, though shortened antenna designs are also possible, with compromises in gain and simplicity. In this study, the target installation area was an attic with a length of 18 m, which constrained the lowest practical band to 10 MHz. The two highest bands, 24 MHz and 28 MHz, are special cases, as they generally become active only under specific and occasional propagation conditions, rather than following a consistent daily pattern.

For this study the 14 MHz (20-m) band was chosen due to its consistent activity levels throughout the day, making it ideal for observing and analyzing propagation conditions over various times and regions. This band strikes a balance between effective long-distance communication and manageable antenna requirements, offering a practical setup for amateur radio research.

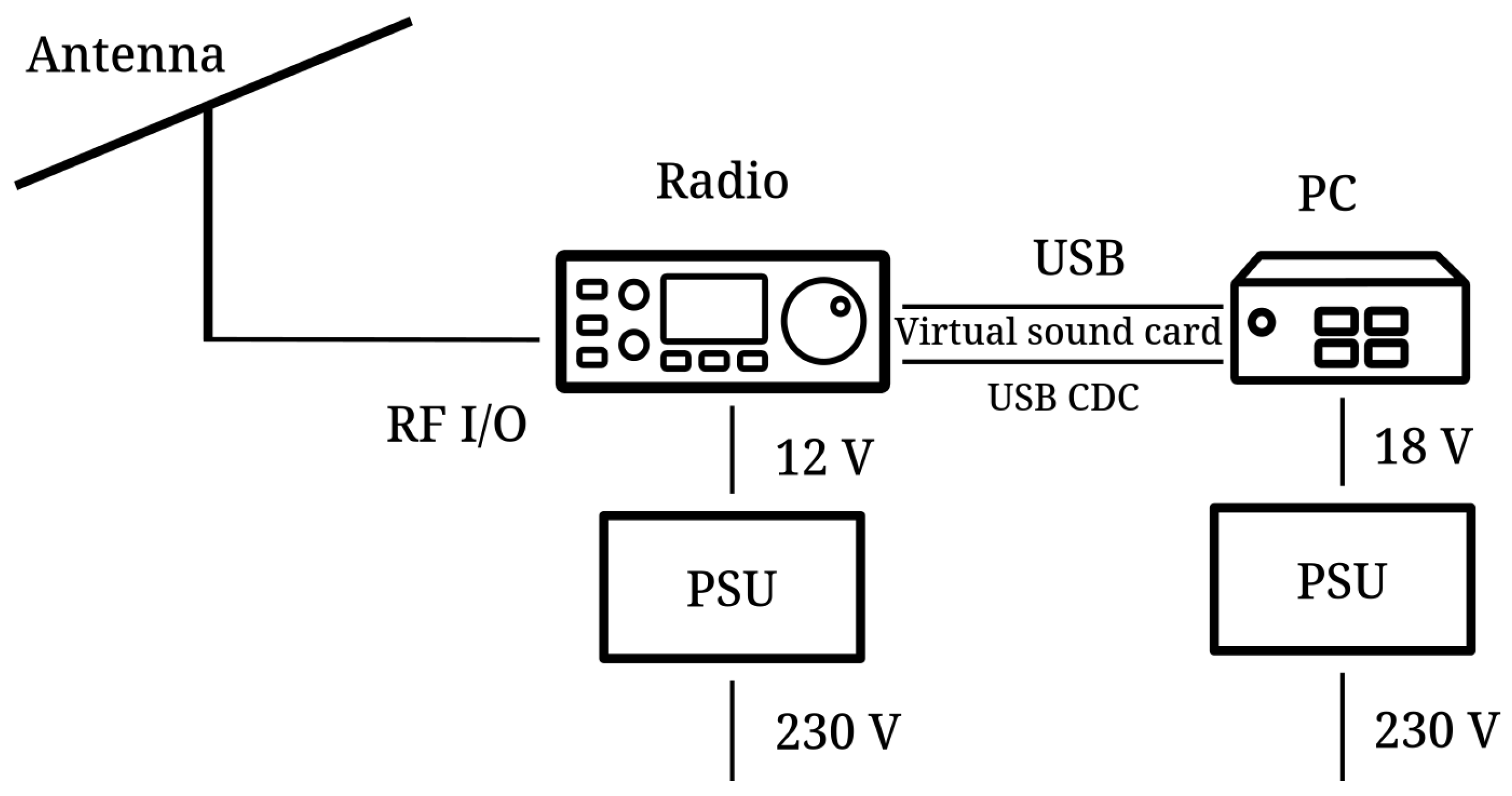

The hardware architecture of the system is shown in

Figure 2. The antenna used in this research is a simple wire dipole [

22], a straightforward yet reliable design with a theoretical gain of 2.15 dBi. Its radiation pattern is approximately omnidirectional, allowing for signal reception and transmission in multiple directions without requiring complex equipment. This configuration provides sufficient performance for studying propagation characteristics, while maintaining a compact and accessible setup.

The mcHF 0.6 [

23] transceiver was utilized in this study, covering the full range of amateur radio bands from 1.8 MHz to 30 MHz. The signal path of the receiver section starts with an optional attenuator / preamplifier block. This block was used in pass-through mode. The next stage of the RF front-end is a 7th order LC bandpass filter with 4 relay-selectable slightly overlapping frequency bands. Note that each distint filter covers multiple ham radio bands. The filtered signal goes into a Tayloe detector [

24], where the quadrature baseband I-Q signal pair is generated. The baseband signal is then amplified and lowpass filtered with low noise operational amplifier-based active filters. The A/D conversion is performed by a high performance 16-bit codec with 48 kHz sample rate. All further signal processing is done digitally by a 32-bit microcontroller. With additional filtering and decimation steps, a second frequency mixing is performed to 12 kHz, where the final selectable filtering takes place. With the appropriate settings the estimate IP3 (third-order intercept point) of the receiver stage of the mcHF transceiver approaches or exceeds +30 dBm.

This high IP3 enhances the receiver’s ability to manage weak signals, even in the presence of strong nearby interference, making it particularly well-suited for experiments involving low-power and low-signal conditions. Importantly, while the mcHF is capable of transmission, the transmission function was disabled throughout this experiment to focus exclusively on signal reception and propagation analysis.

This versatile transceiver offers a USB interface, enabling full control over key parameters such as frequency, transmit/receive modes, and filter settings. Simultaneously, the USB connection also serves as an audio interface, streamlining the integration with digital communication software for data exchange and signal processing.

The transceiver was connected to an Intel NUC DCCP847DYE mini-PC, equipped with an Intel Celeron 847E CPU running at 1.10 GHz, 8 GB of RAM, and 128 GB of NVMe SSD storage. Despite its relatively modest specifications, this resource-constrained setup provides sufficient computing power to effectively control the radio transceiver and execute signal processing algorithms, all while maintaining low energy consumption. Additionally, the PC features a power management setting that automatically powers the device when electricity is restored after an outage.

3.3. Software Architecture

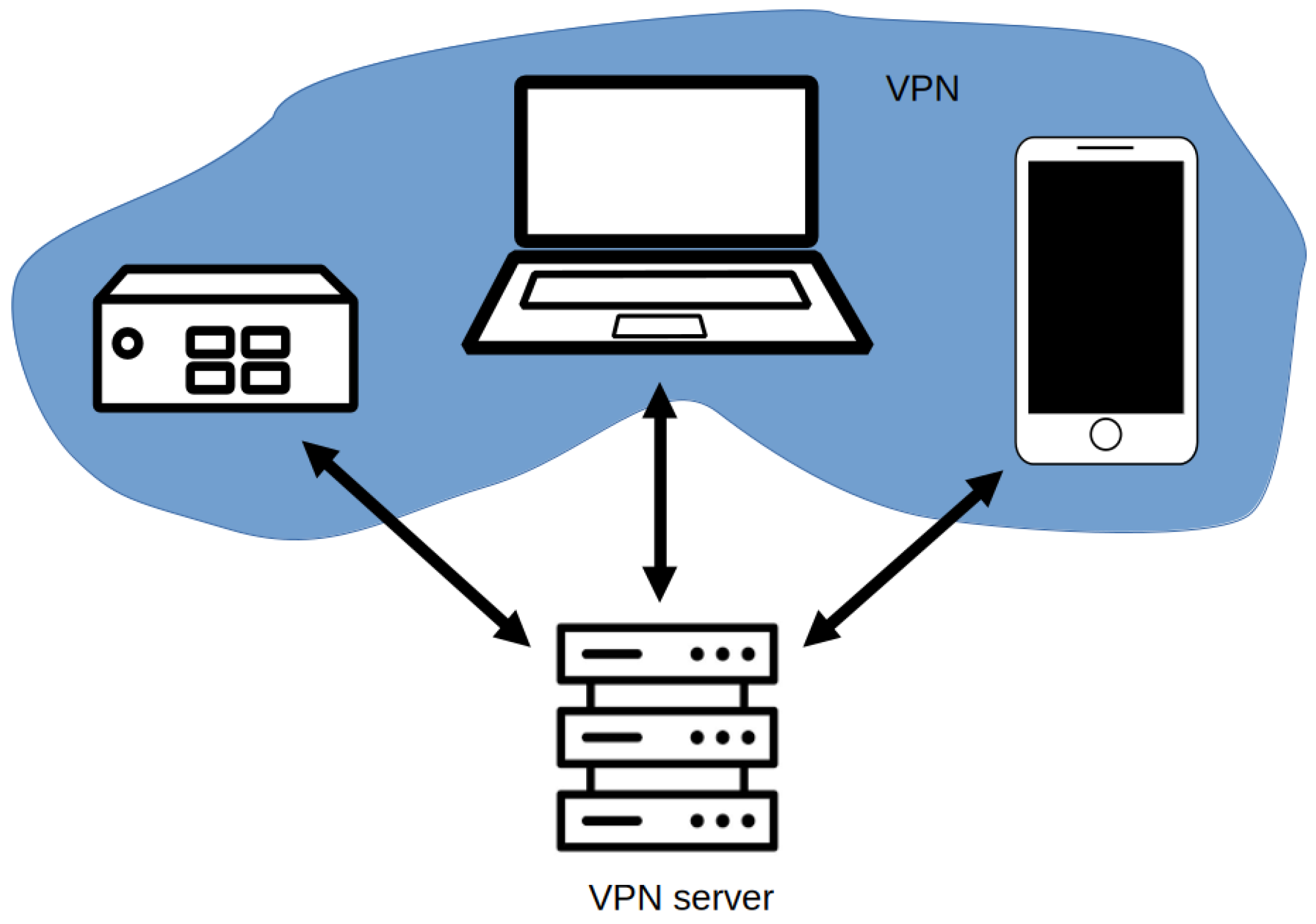

The network architecture of the system is shown in

Figure 3. The PC runs Debian Linux 12.5 in headless mode, i.e., it is accessible only through remote connections. Shell access is granted via SSH (Secure Shell), providing command-line control. Since the signal processing software (WSJT-X, discussed later) requires a graphical interface, a VNC (Virtual Network Computing) [

25] session is configured to launch automatically upon startup. This allows the desktop environment to be accessed remotely using a VNC viewer, such as RealVNC, providing full graphical access to the system.

To provide more flexible remote access the PC is connected to a VPN (Virtual Private Network) using OpenVPN. The OpenVPN client automatically connets to the server during bootup and reconnects in case of any network error.

The decoding of the FT8 communication is done using WSJT-X [

26]. WSJT-X (Weak Signal Joe Taylor-Extended) is an open-source software suite specifically designed for weak-signal communication by amateur radio operators. Developed by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Joe Taylor (K1JT) and a team of contributors, WSJT-X supports various digital modes like FT8, JT65, JT9, and WSPR, which are optimized for low-power, long-distance communication even under challenging conditions. These modes are particularly useful when working with faint or distorted signals, allowing users to make successful contacts in situations where traditional voice or Morse code communication would fail. The software uses advanced signal processing algorithms to decode transmissions at or below the noise floor, making it highly effective for weak-signal work.

One of WSJT-X’s most popular modes is FT8, which has gained widespread adoption in the amateur radio community due to its efficiency and reliability. FT8, for example, allows brief, structured exchanges in just 15-second transmission intervals, making it ideal for quick and automated contacts across great distances. WSJT-X provides a user-friendly graphical interface, real-time decoding, and automated message exchanges, making it accessible to both beginner and experienced operators. Additionally, it supports logging and integration with other radio control software, further enhancing its versatility. Overall, WSJT-X is a powerful tool for maximizing communication possibilities under poor propagation or limited power conditions.

4. Results

4.1. Collected Data and Preprocessing

WSJT-X logs all decoded message into a single ASCII text file (named ALL.TXT). Each line of the file corresponds to a decoded message, with timestamp and frequency information.

The data collection system was continuously run for a year, from 25 June 2024 to 25 June 2025, decoding and logging 30,819,847 messages. Since the system was not equipped with an uninterruptible power supply (UPS), unexpected power failures occured, causing minor errors in the log file. Another source of errors is false decoding. Since FT8 is primarily designed for human operation, WSJT-X is intentionally configured to be highly permissive—favoring the risk of false positives over missed valid decodes. In typical usage, this trade-off is acceptable, as the software’s automatic sequencing halts upon a false decode; a non-existent station will not respond, preventing the exchange from continuing.

The processing algorithms filter messages based on the occurrence of observed callsign–grid square pairs, treating the sender’s callsign and its corresponding grid square as a single compound source. False decodings can generate arbitrary grid locators, and grid squares that appear only once in the dataset can be trivially excluded. Since there are only 32,400 possible four-character grid squares, a dataset containing more than 30 million messages can easily contain at least two (or more) falsely decoded messages associated with the same invalid grid square. To address this more effectively, both grid squares and callsigns are considered jointly, and messages originating from sources (defined by callsign–grid square pairs) that occur fewer times than a configurable threshold k are disregarded.

Although advanced mathematical, statistical, and machine learning methods [

27,

28] could have been applied to analyze the collected data in greater depth, the researchers chose to focus primarily on the design and operation of the data collection system, providing only preliminary insights into the dataset. More detailed analysis and processing will be addressed in a separate article, dedicated exclusively to data interpretation and modeling.

4.2. Accessed Grid Squares

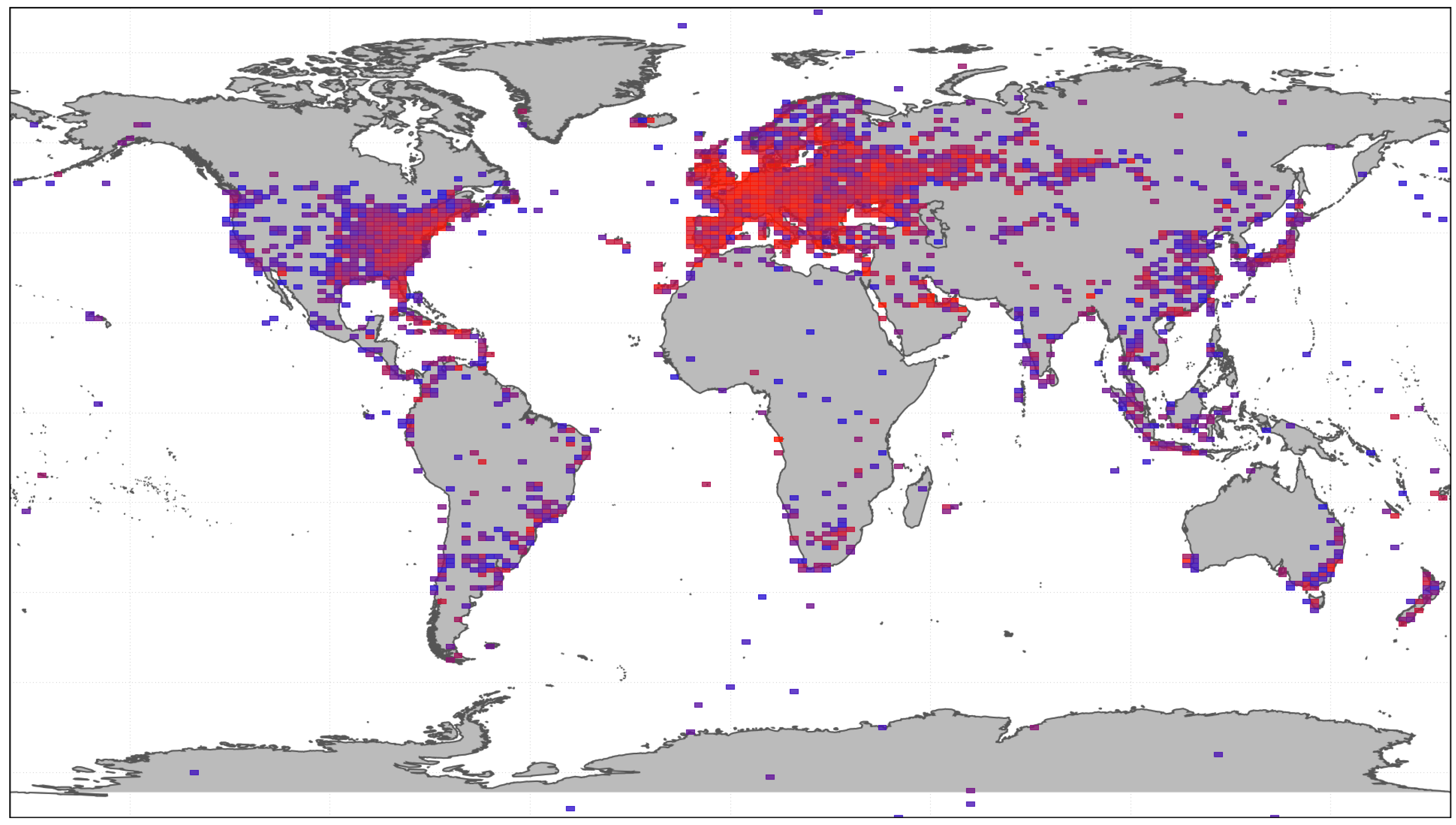

To provide an overall view of the collected data, a heat map of grid squares was generated, illustrating the spatial distribution and density of captured messages across different geographical regions, as shown in

Figure 4. Blue color means less captured messages, red color means more.

The map is clearly dominated by Europe and the eastern United States, both forming large, continuous regions of activity. Additional areas with significant coverage include Central America, Japan, the eastern and southwestern coasts of Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia. In contrast, other regions exhibit only sporadic FT8 activity.

Numerous islands—such as the Canary Islands, Cape Verde, St. Helena, Seychelles, Mauritius, Réunion, and many smaller ones—also display a high density of contacts. This measurement is somewhat biased, as these locations are popular among amateur radio operators who actively seek rare or remote contacts.

An interesting phenomenon is the presence of signal sources in the open ocean, which can be attributed to maritime vessels equipped with ham radio transceivers.

Lastly, Antarctica also appears on the map with notable FT8 activity, particularly around the Neumayer Station III [

29].

The distribution of accessed grid squares shows a strong correlation with the population density of the respective regions. While the effects of skip zones tend to overlap in a dataset spanning an entire year, the influence of the first skip zone remains visible, appearing as bluer grid squares across parts of Eastern Europe.

4.3. Hourly Distance Distribution

To analyze changes in propagation, heat maps were created showing the hourly distribution of received messages across different distance ranges with 500 km bins. Three 10-day intervals were selected—one from the winter of 2024, and two from the spring and summer of 2025.

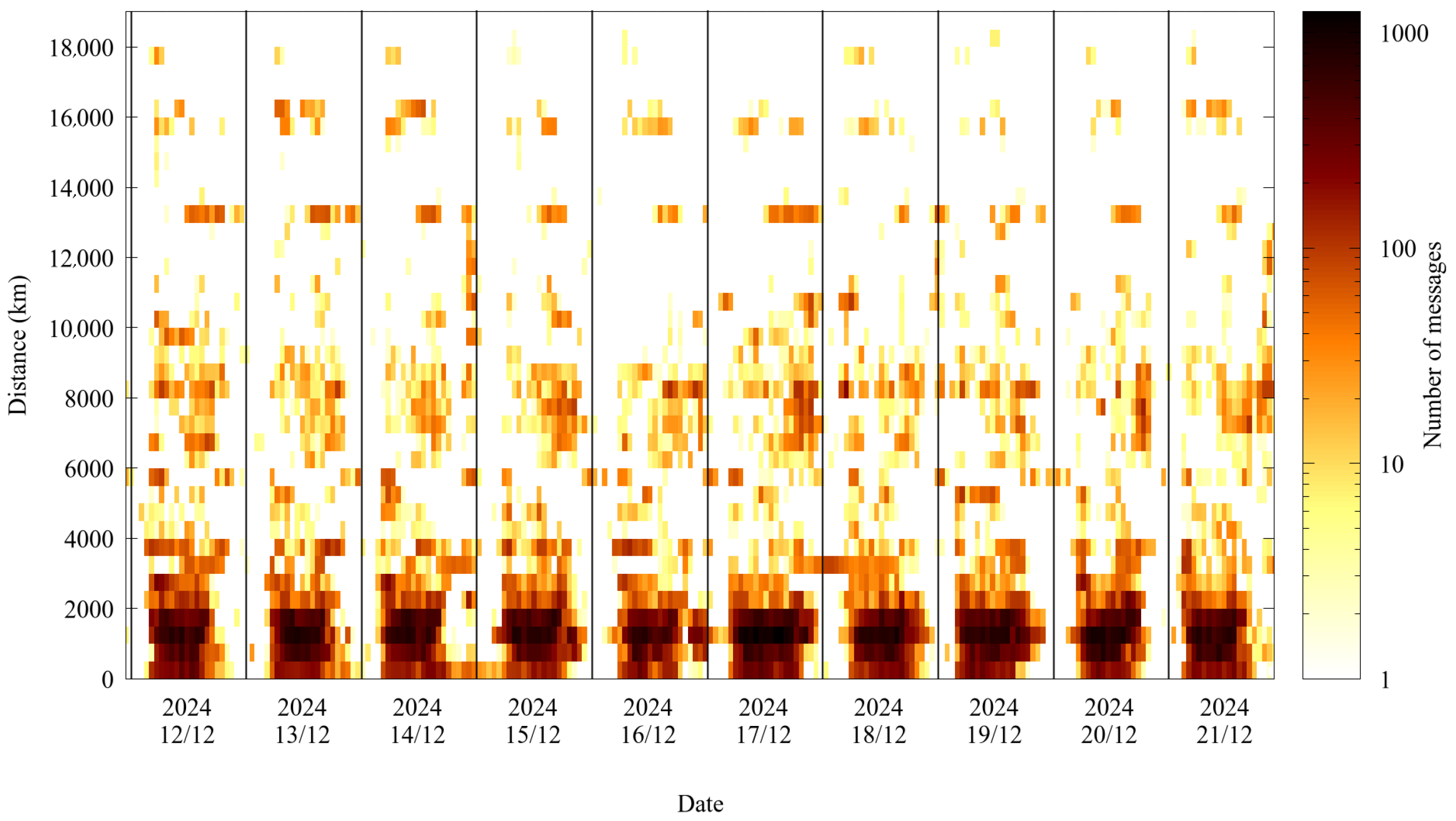

The daily patterns are similar during the same 10-day period. In wintertime (see

Figure 5) stations within 2000 km are generally observable throughout the day, except for a few nighttime hours around midnight. This is the range that can typically be reached via a single ionospheric reflection (hop). The reduced propagation observed at night is primarily caused by the decreased ionization level of the F2 layer. The lowest distance bin shows reduced activity. Due to the skip zone, these distances are already too far for reliable ground wave propagation yet too close for skywave reflection.

The zone between 6000 km and 9000 km shows regular but smaller activity, with the strongest distance interval being in the 7500–8000 km range, forming the second skip space. Three additional high-activity ranges are observed at 13,000–13,500 km, 15,500–16,500 km, and 17,500–18,000 km, forming the 3rd, 4th, and 5th skip spaces. Communication over these distances is only possible for short intervals, although such conditions may recur over several consecutive days.

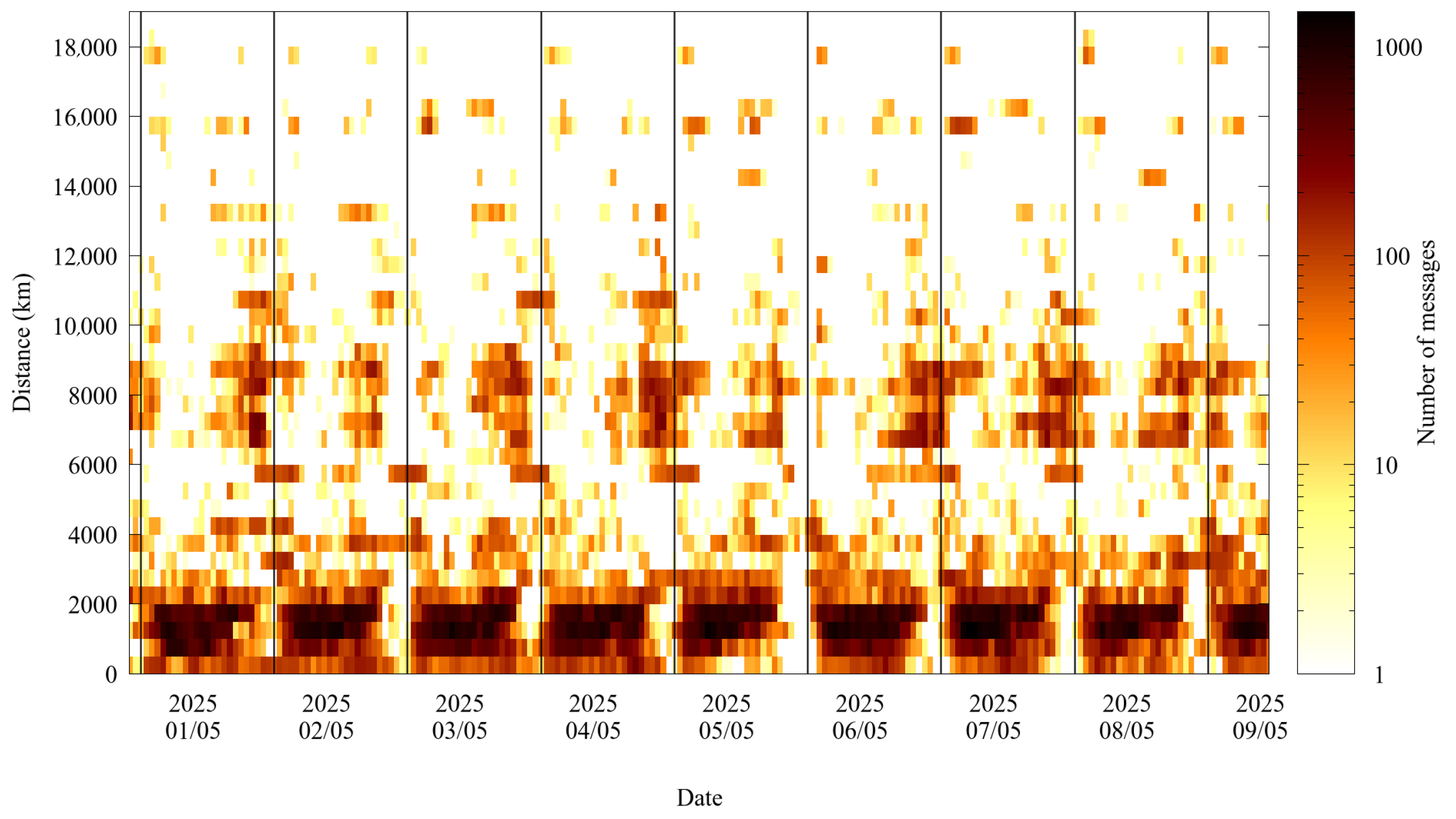

Figure 6 presents the hourly distance distribution for a 10-day period in spring. The overall patterns resemble those observed in winter, but with generally higher activity levels. For distances under 2000 km, the gaps around midnight are noticeably shorter. The first skip space (2000–6000 km) shows a strong but irregular pattern. The 6000–9000 km range (second skip space) exhibits significantly stronger activity, with an inverse pattern to short-range communication—showing peak intensity during nighttime hours. At even greater distances (in higher skip spaces), continuous communication is occasionally possible for several consecutive hours.

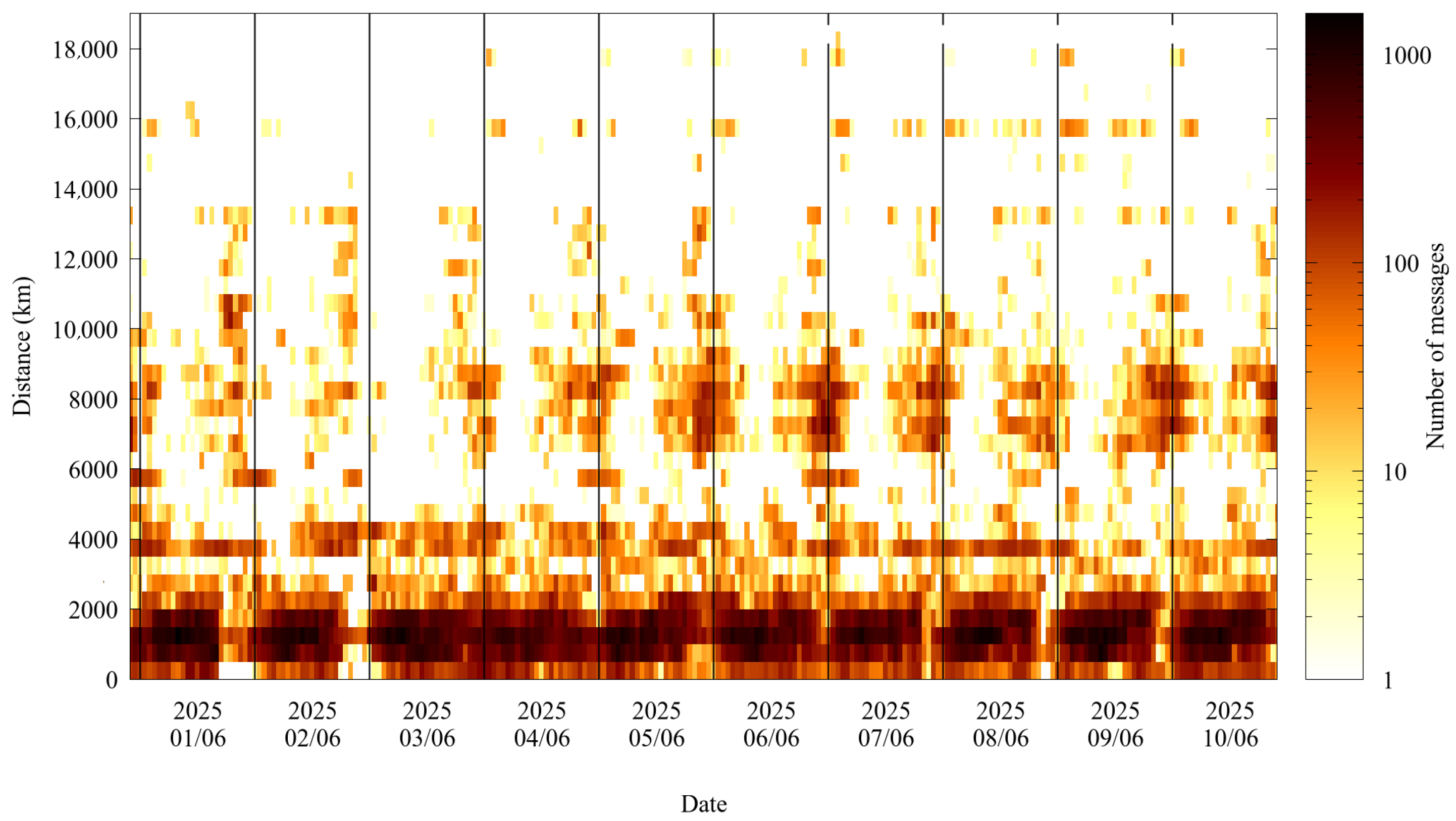

Figure 7 shows a 10-day period in summer. Communication in the first skip space (under 2000 km) is nearly continuous, while the second skip space (2000–6000 km) shows increased strength compared to earlier seasons. The 3rd skip space between 6000 and 9000 km remains comparable to spring, and activity at distances beyond 9000 km also exhibits similar patterns.

5. Summary

This study demonstrated the design and implementation of an automated, remotely accessible system for radio propagation data collection using the widely used FT8 protocol. The architecture and key components of the system were presented, highlighting its cost-efficiency, ease of deployment, and suitability for long-term, unattended operation.

Over the course of one year, the system recorded more than 30 million FT8 messages from stations across all continents, including Antarctica, numerous islands, and vessels at sea. This extensive dataset enabled a comprehensive analysis of HF propagation patterns on the 20 m amateur radio band. The results were consistent with established seasonal propagation behavior while providing a higher level of temporal and spatial detail than typically achievable with manual or less-frequent observations.

The findings confirm that large-scale, automated FT8 reception offers a powerful and accessible method for ionospheric and propagation research, supporting both the validation of existing models and the discovery of finer-scale phenomena.