Turbomachinery Noise Predictions: Present and Future

Abstract

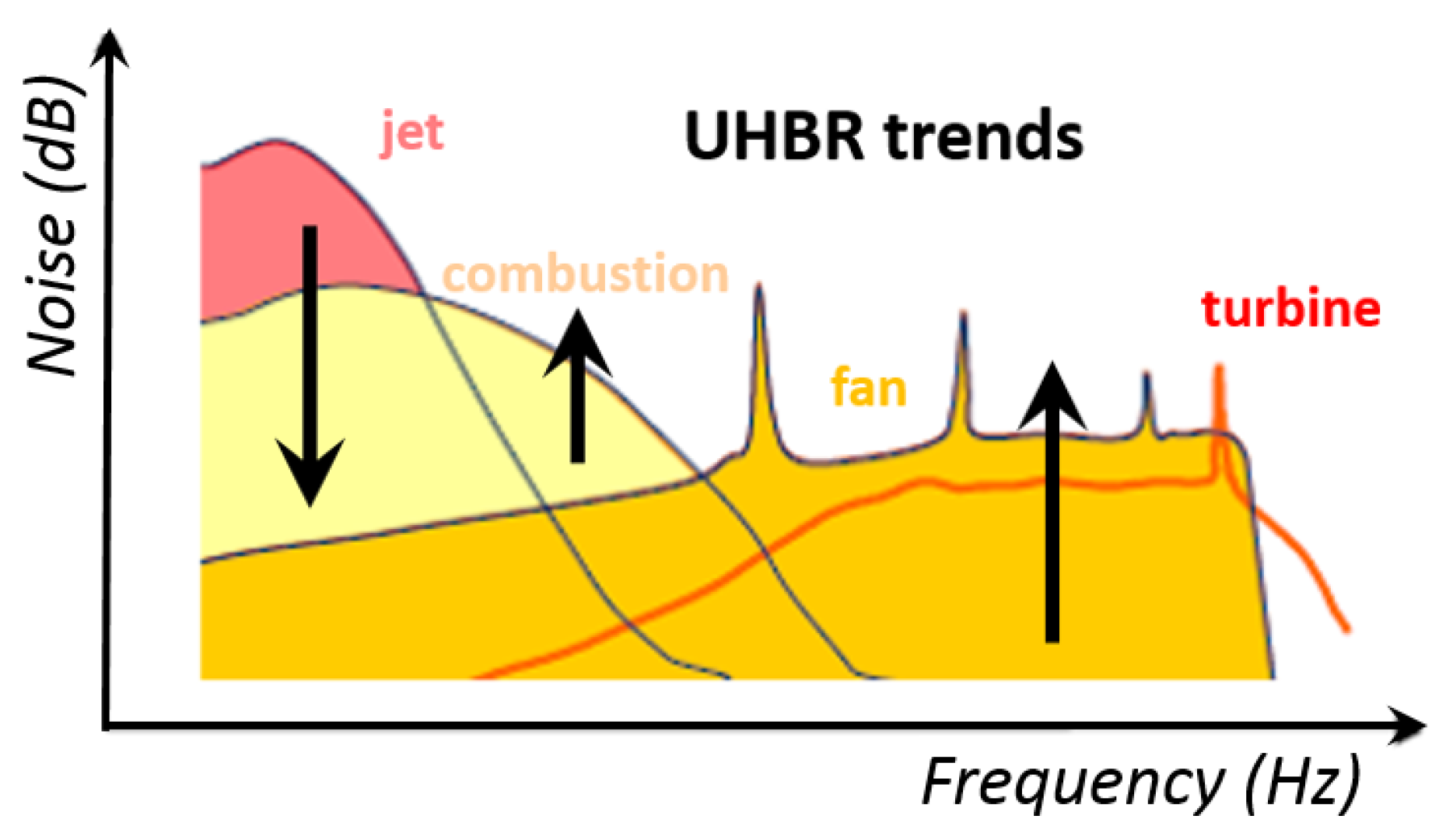

1. Introduction

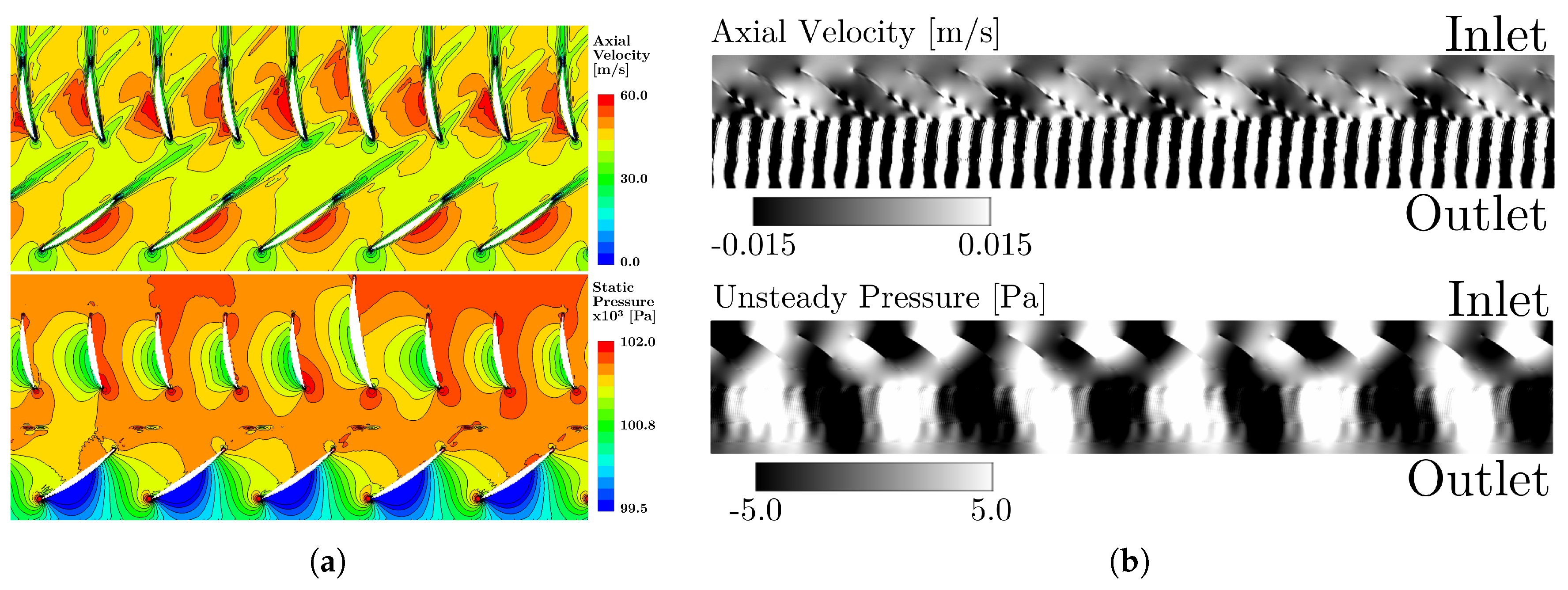

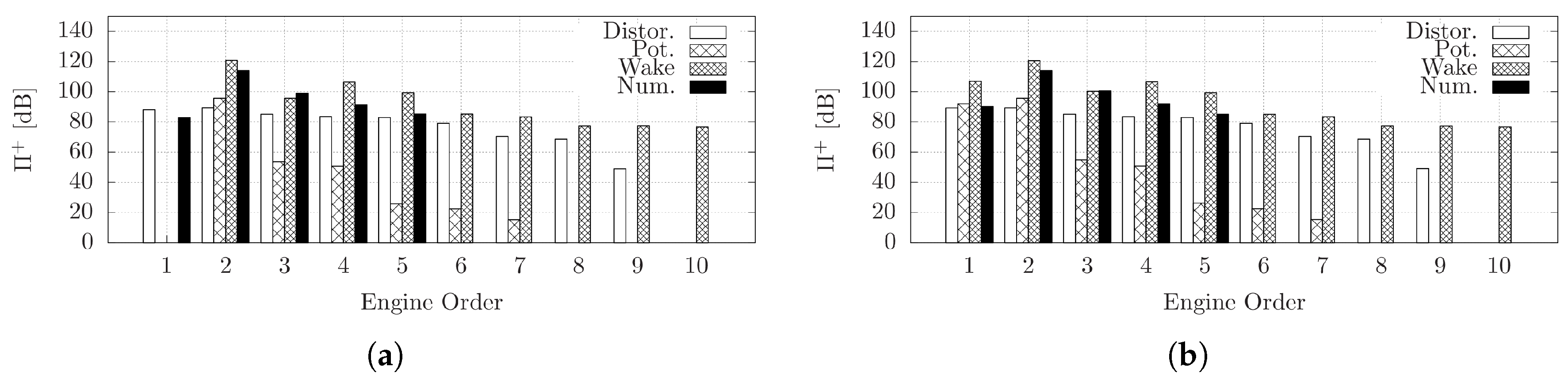

2. Turbomachinery Tonal Noise

2.1. Analytical Models

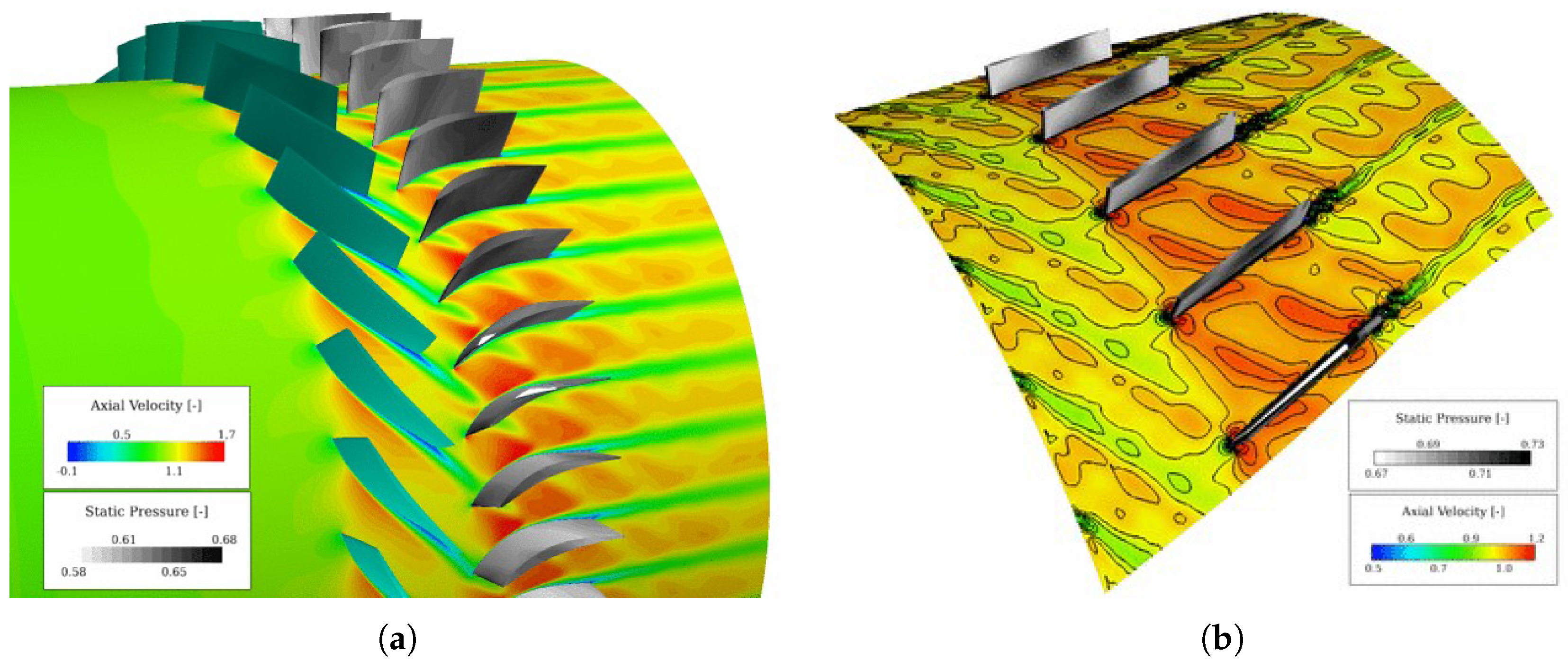

2.2. Numerical Methods

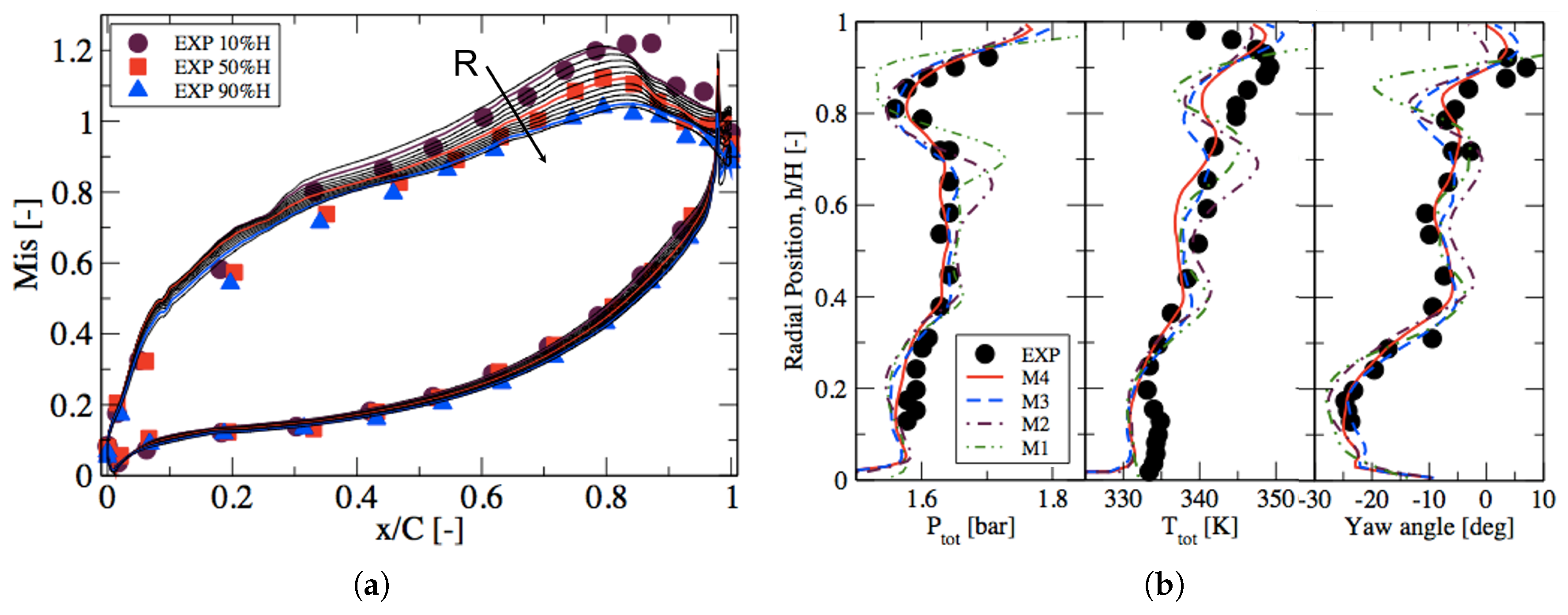

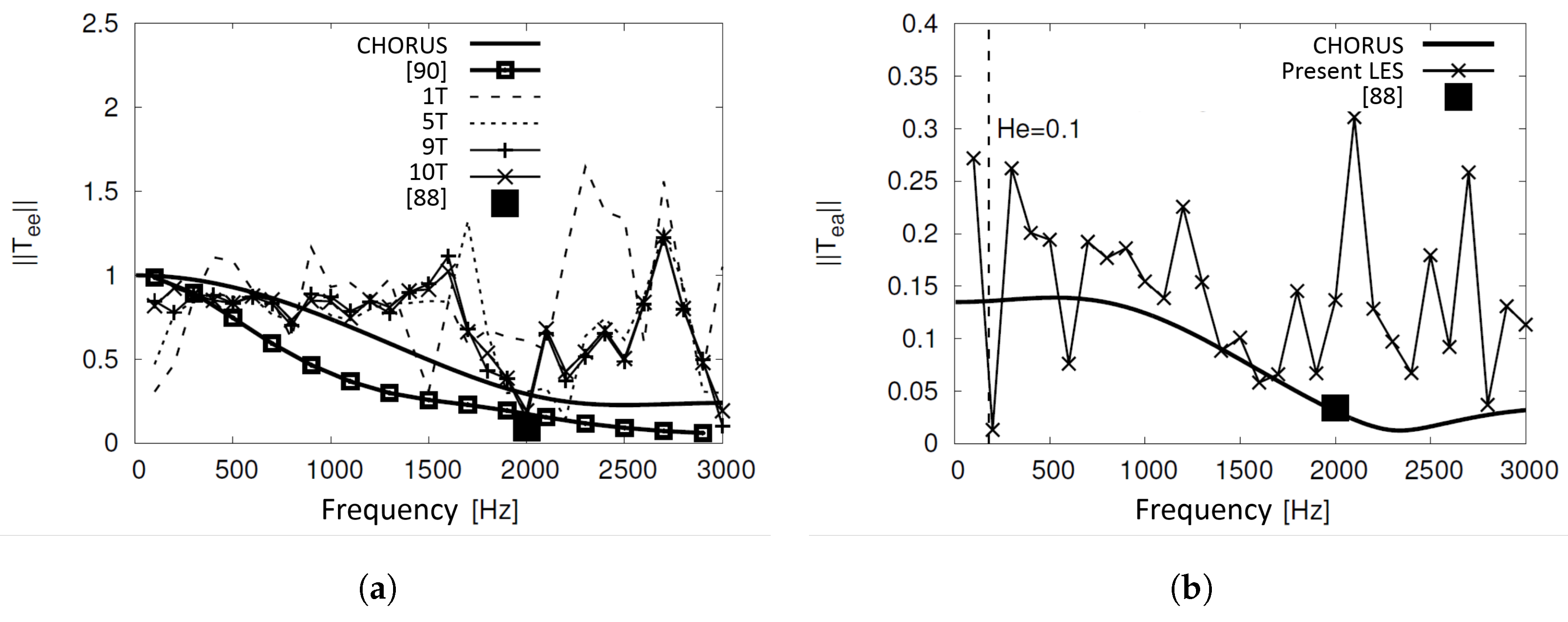

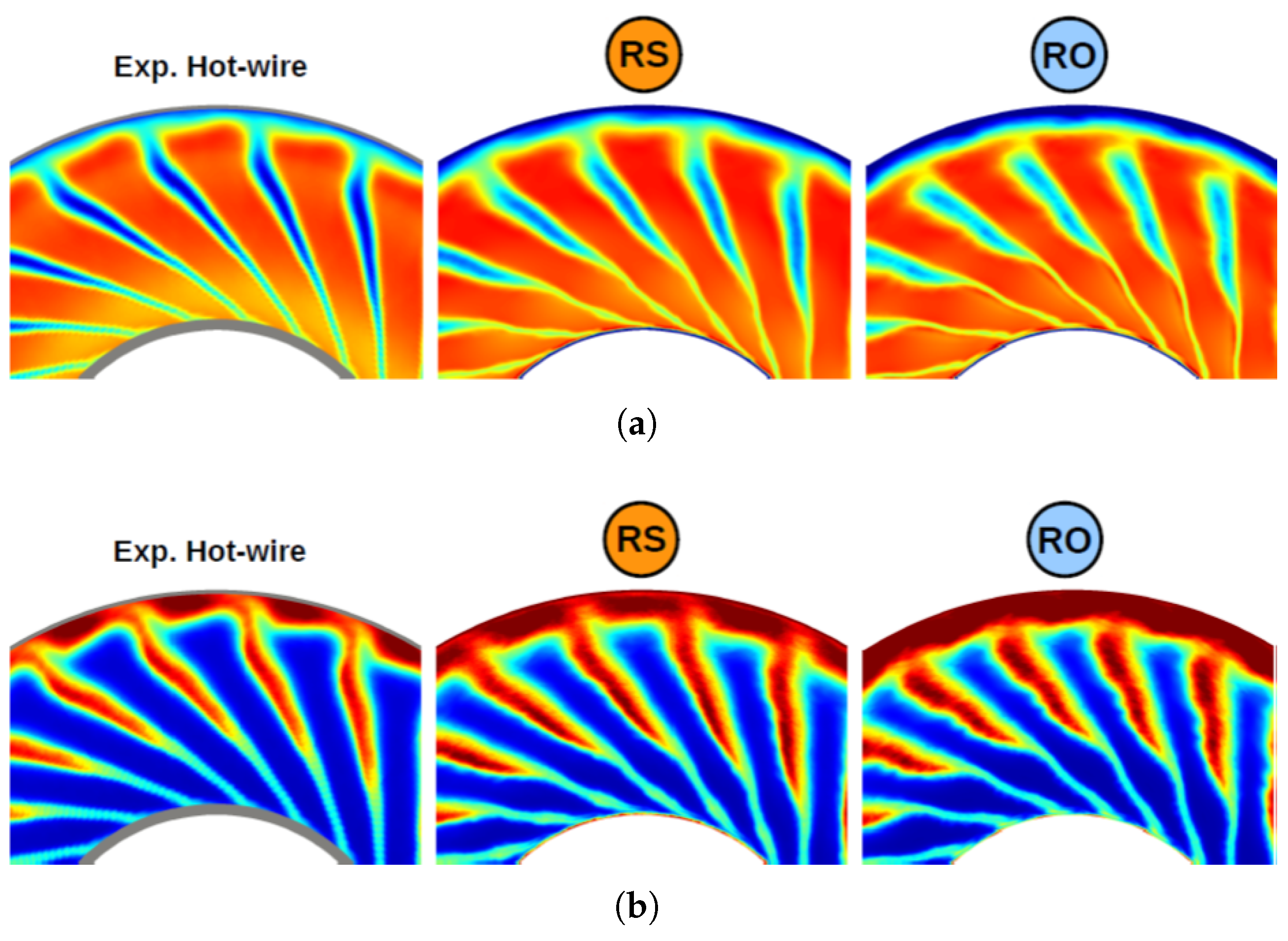

2.3. Results

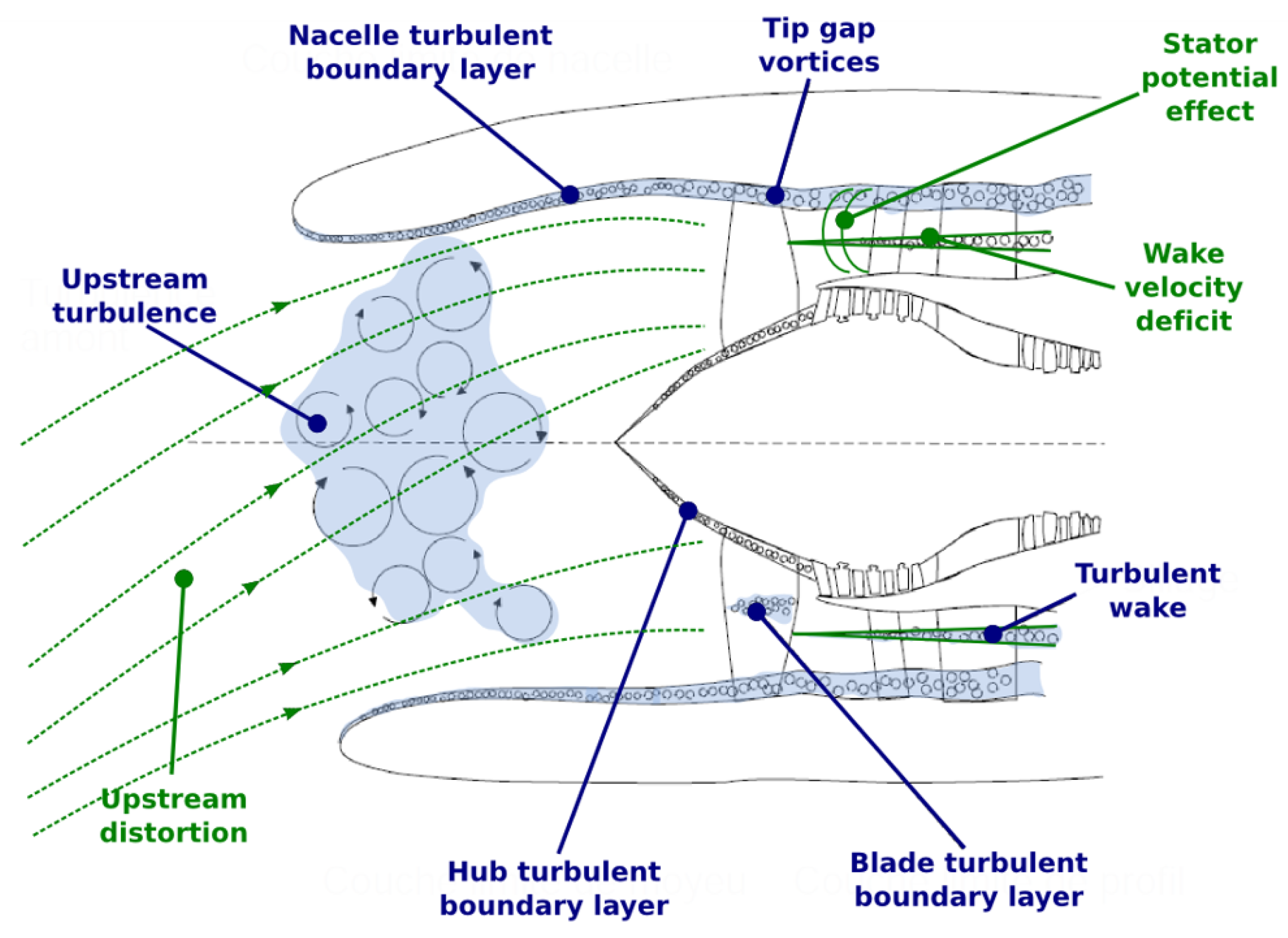

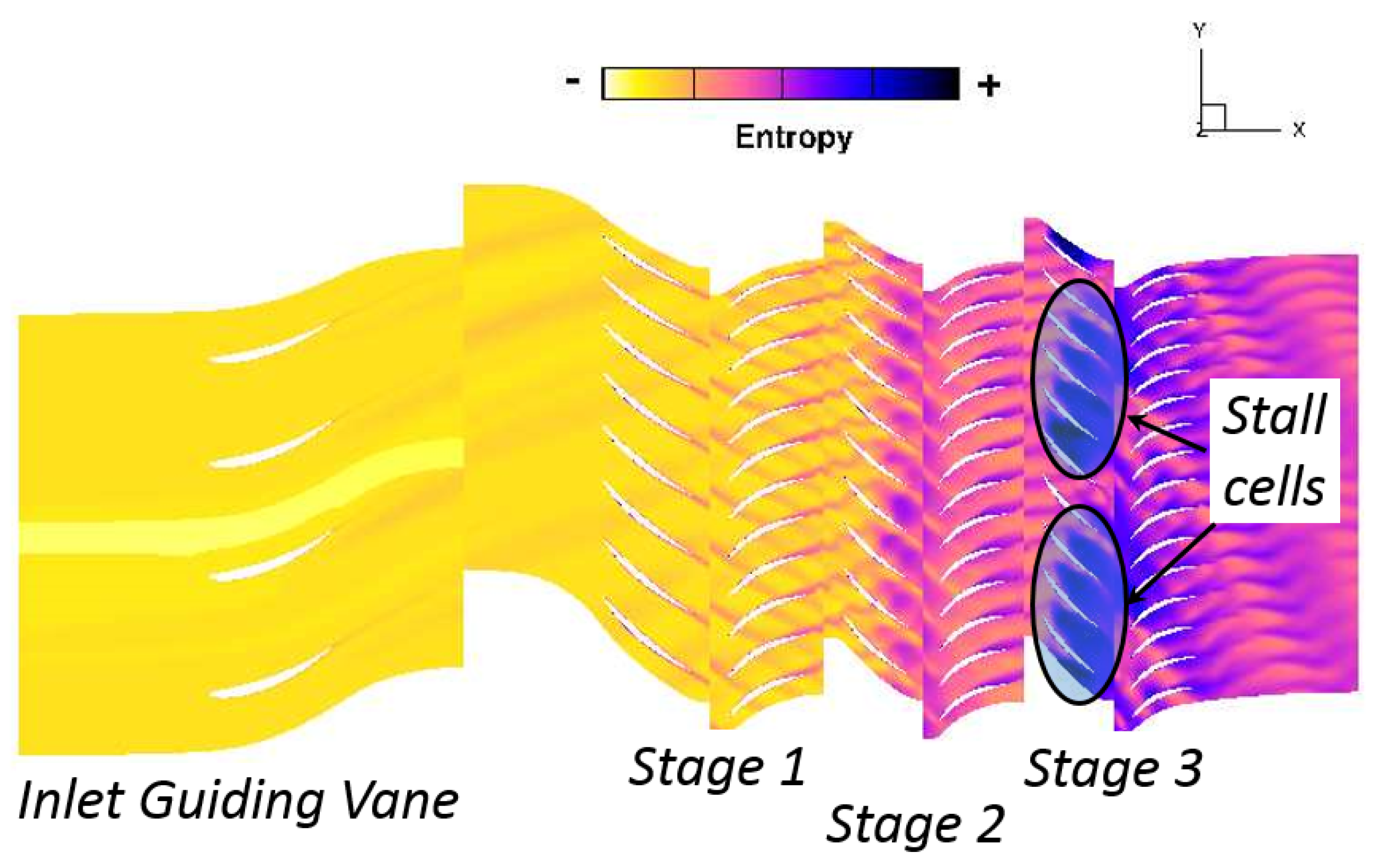

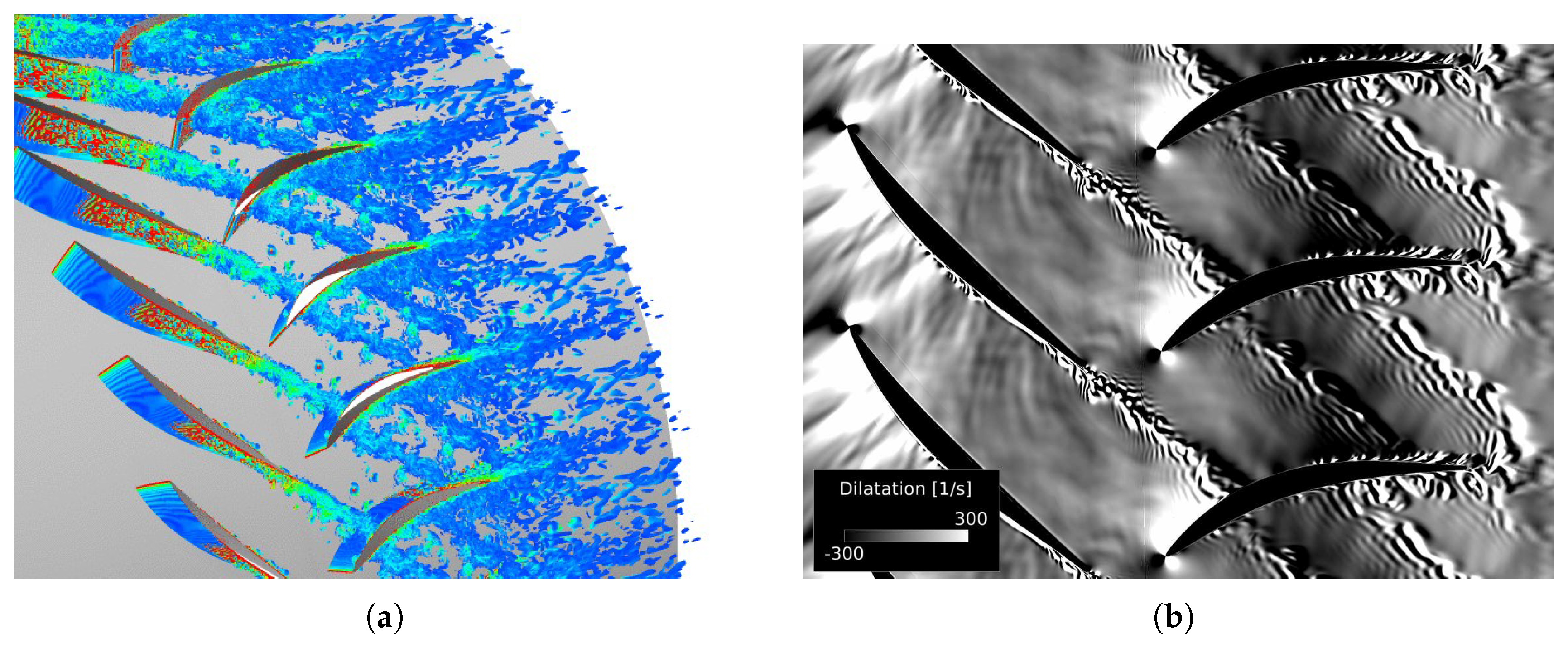

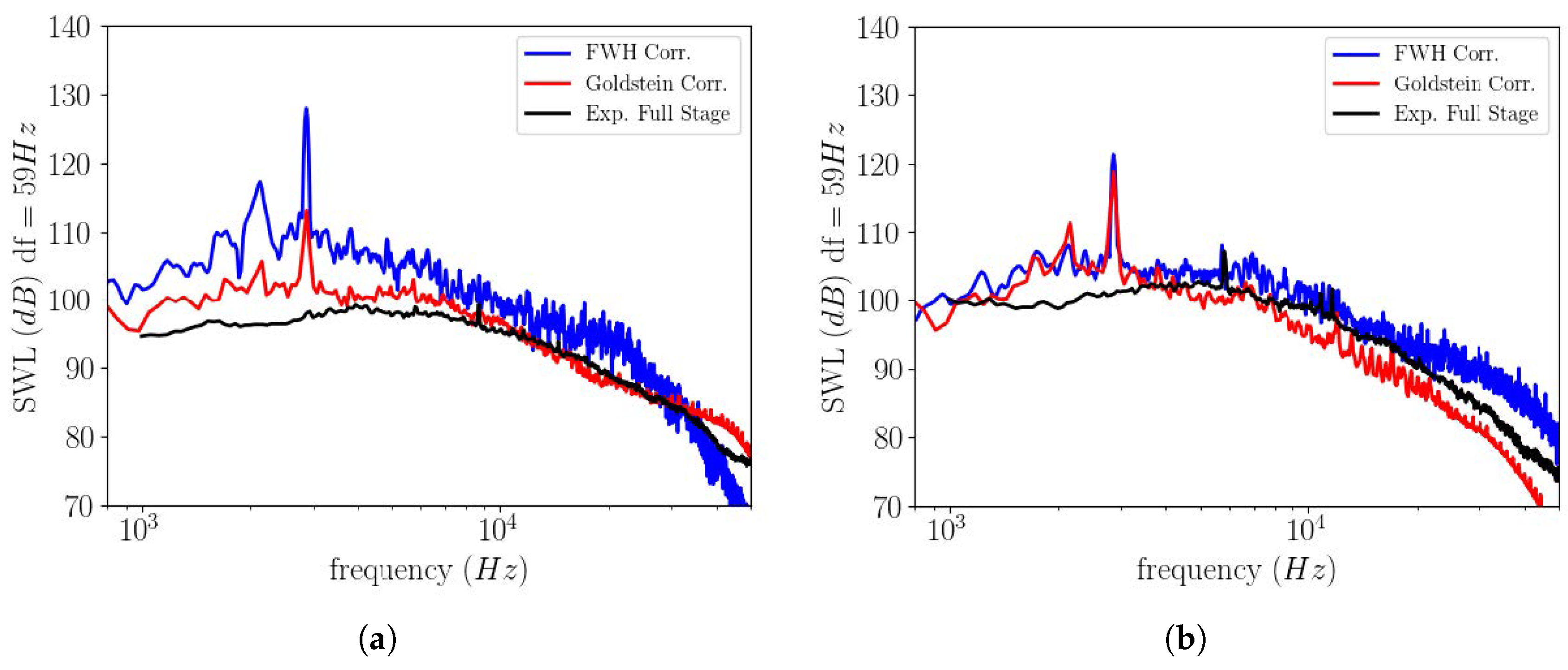

3. Turbomachinery Broadband Noise

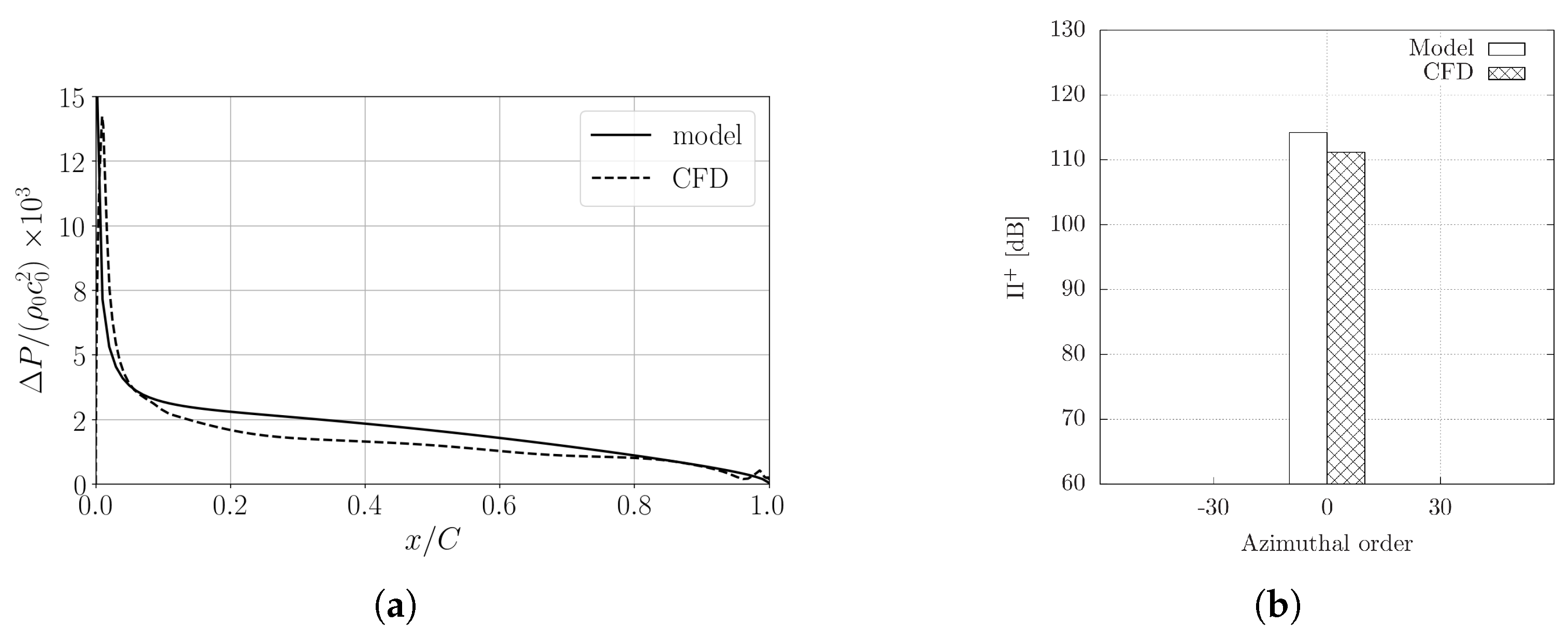

3.1. Analytical Model

3.2. Numerical Methods

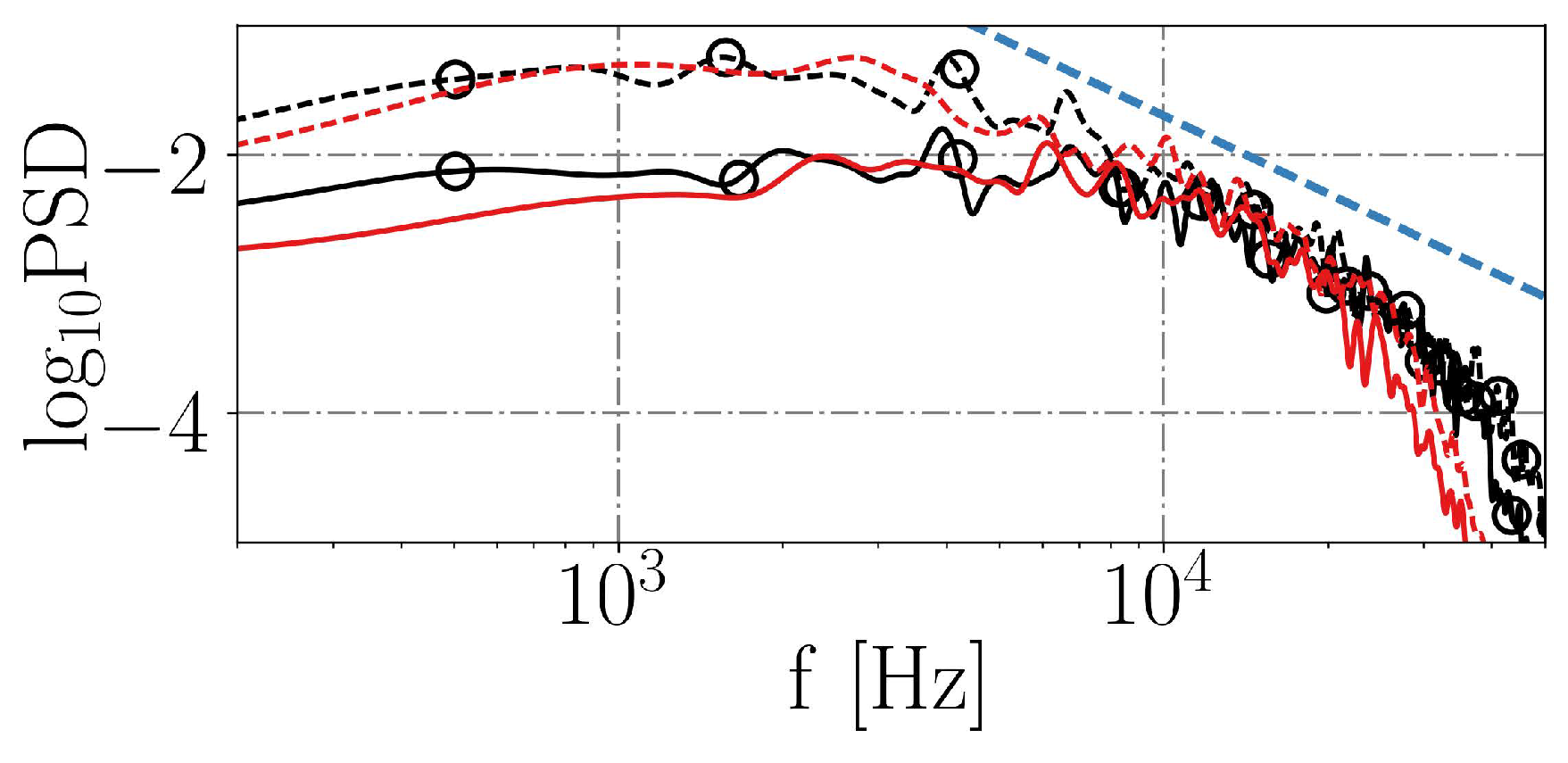

3.3. Results

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hughes, C. NASA Collaborative Research on the Ultra High Bypass Engine Cycle and Potential Benefits for Noise, Performance, and Emissions; Technical Memorandum TM-2013-216345; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Hultgren, L.S. Editorial: Emerging importance of turbine noise. Int. J. Aeroacoust. 2011, 10, i–iv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, E. Towards a quieter low pressure turbine: Design characteristics and prediction needs. Int. J. Aeroacoust. 2011, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, S. Turbomachinery-related aeroacoustic modelling and simulation. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Fluid Flow Technologies, Budapest, Hungary, 4–7 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kontos, K.B.; Janardan, B.A.; Gliebe, P.R. Improved NASA-ANOPP Noise Prediction Computer Code for Advanced Subsonic Propulsion Systems Volume 1: ANOPP Evaluation and Fan Noise Model Improvement; Contractor Report CR-195480; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1986.

- Lopez, L.V.; Burley, C.L. Design of the next generation aircraft noise prediction program: ANOPP2. In Proceedings of the 17th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2011-2854), Portland, OR, USA, 5–8 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ffowcs Williams, J.E.; Hawkings, D.L. Sound Generation by Turbulence and Surfaces in Arbitrary Motion. Philo. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1969, 264, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ffowcs-Williams, J.E.; Hawkings, D.L. Theory relating to the noise of rotating machinery. J. Sound Vib. 1969, 10, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowson, M.V. Theoretical Studies of Compressor Noise; Contractor Report CR-1287; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1969.

- Goldstein, M.E. Aeroacoustics; Mc Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Daroukh, M.; Moreau, S.; Gourdain, N.; Boussuge, J.; Sensiau, C. Effect of Distortion on Turbofan Tonal Noise at Cutback with Hybrid Methods. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2017, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posson, H.; Peake, N. The acoustic analogy in an annular duct with swirling mean flow. J. Fluid Mech. 2013, 726, 439–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.; Peake, N. The acoustic Green’s function for swirling flow in a lined duct. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 395, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, S.; Roger, M. Advanced noise modeling for future propulsion systems. Int. J. Aeroacoust. 2018, 17, 576–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, M.; Moreau, S. Extensions and limitations of analytical airfoil broadband noise models. Int. J. Aeroacoust. 2010, 9, 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glegg, S.A.L. The response of a swept blade row to a three-dimensional gust. J. Sound Vib. 1999, 227, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Laborderie, J.; Moreau, S. Prediction of tonal ducted fan noise. J. Sound Vib. 2016, 372, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Laborderie, J.; Blandeau, V.; Node-Langlois, T.; Moreau, S. Extension of a Fan Tonal Noise Cascade Model for Camber Effects. AIAA J. 2015, 53, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, D.A. TFaNS Tone Fan Noise Design/Prediction System: User’s Manual, TFaNS Vers1.5; Contractor Report CR-2003-212380; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Baddoo, P.; Ayton, L. An Analytic Solution for Gust Cascade Interaction Including Effects of Realistic Aerofoil Geometry—Inter-Blade Region. In Proceedings of the 24th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2018-2957), Atlanta, GA, USA, 25–29 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bouley, S.; François, B.; Roger, M.; Posson, H.; Moreau, S. On a two-dimensional mode-matching technique for sound generation and transmission in axial-flow outlet guide vanes. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 403, 190–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hixon, R. Computational Aeroacoustics Prediction of Acoustic Transmission Through a Realistic 2D Stator. In Proceedings of the 17th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2011-2706), Portland, OR, USA, 6–8 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Soulat, L.; Ferrrand, P.; Moreau, S.; Aubert, S.; Buisson, M. Efficient optimisation procedure for design problems in fluid mechanics. Comput. Fluids 2013, 82, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, J. Resolving the dependence on freestream values for the k-omega turbulence model. AIAA J. 2000, 38, 1292–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Madavan, N. Multi-Airfoil Navier–Stokes Simulations of Turbine Rotor-Stator Interaction. J. Turbomach. 1990, 112, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerolymos, G.; Michon, G.; Neubauer, J. Analysis and application of chorochronic periodicity in turbomachinery rotor/stator interaction computations. J. Propuls. Power 2002, 18, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, M.B. Calculation of unsteady wake/rotor interaction. J. Propuls. Power 1988, 4, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guédeney, T.; Gomar, A.; Gallard, F.; Sicot, F.; Dufour, G.; Puigt, G. Non-uniform time sampling for multiple-frequency harmonic balance computations. J. Comput. Phys. 2013, 236, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dooler, G.D. Lattice Boltzmann method for fluid flows. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1998, 30, 329–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brès, G.; Pérot, F.; Freed, D. Properties of the Lattice–Boltzmann Method for Acoustics. In Proceedings of the 15th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2009-3395), Miami, FL, USA, 11–13 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peake, N.; Parry, A.B. Modern challenges facing turbomachinery aeroacoustics. Annu. Rev. Fluid. Mech. 2012, 44, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Laborderie, J.; Soulat, L.; Moreau, S. Prediction of Noise Sources in Axial Compressor from URANS Simulation. J. Propuls. Power 2014, 30, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Laborderie, J.; Moreau, S. Evaluation of a Cascade-Based Acoustic Model for Fan Tonal Noise Prediction. AIAA J. 2014, 52, 2877–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjosé, M.; Daroukh, M.; Magnet, W.; De Laborderie, J.; Moreau, S.; Mann, A. Tonal fan noise prediction and validation on the ANCF configuration. Noise Control Eng. J. 2015, 63, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S.; Pestana, M.; Roger, M. Effect of Weak Outlet-Guide-Vane Heterogeneity on Rotor-Stator Tonal Noise. AIAA J. 2017, 55, 3440–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R. Resonant effects in wake shedding from parallel plates: Calculation of resonant frequencies. J. Sound Vib. 1967, 5, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holewa, A.; Weckmüller, C.; Guérin, S. Impact of bypass duct bifurcations on fan noise. J. Propuls. Power 2014, 30, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Moreau, S.; Carolus, T. Turbofan Inlet Distortion Noise Prediction with a Hybrid CFD-CAA Approach. In Proceedings of the 20th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2014-3102), Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–20 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Daroukh, M.; Moreau, S.; Gourdain, N.; Boussuge, J.; Sensiau, C. Complete Prediction of Modern Turbofan Tonal Noise at Transonic Regime. In Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on Transport Phenomena and Dynamics of Rotating Machinery, Lahaina, HI, USA, 16–21 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pardowitz, B.; Tapken, U.; Neuhaus, L.; Enghardt, L. Experiments on an Axial Fan Stage: Time-Resolved Analysis of Rotating Instability Modes. J. Eng. Gas Turb. Power 2015, 137, 062505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudina, M. Noise Generation in Vane Axial Fans due to Rotating Stall and Surge. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2001, 215, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crevel, F.; Gourdain, N.; Moreau, S. Numerical simulation of aerodynamic instabilities in a multistage high-speed high-pressure compressor on its test-rig: Part 1—Rotating stall. J. Turbomach. 2014, 136, 101003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandeau, V.; Joseph, P.; Kingan, M.; Parry, A. Broadband noise predictions from uninstalled contra-rotating open rotors. Int. J. Aeroacoust. 2013, 12, 245–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, R.W.; Amiet, R.K. Noise of a Model Helicopter Rotor Due to Ingestion of Turbulence; Contractor Report CR-3213; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1979.

- Schlinker, R.H.; Amiet, R.K. Helicopter Rotor Trailing Edge; Contractor Report CR-3470; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1981.

- Amiet, R.K. Acoustic radiation from an airfoil in a turbulent stream. J. Sound Vib. 1975, 41, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiet, R.K. Noise due to turbulent flow past a trailing edge. J. Sound Vib. 1976, 47, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, M.; Moreau, S. Back-scattering correction and further extensions of Amiet’s trailing edge noise model. Part 1: Theory. J. Sound Vib. 2005, 286, 477–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, S.; Roger, M. Back-scattering correction and further extensions of Amiet’s trailing-edge noise model. Part II: Application. J. Sound Vib. 2009, 323, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, M.; Moreau, S.; Guedel, A. Broadband Fan Noise Prediction using Single-Airfoil Theory. Noise Control Eng. J. 2006, 54, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S. Fast and accurate analytical modeling of broadband noise for a low-speed fan. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2018, 143, 3103–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinayoko, S.; Kingan, M.; Agarwal, A. Trailing edge noise theory for rotating blades in uniform flow. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013, 469, 20130065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, D.B. Theory of Broadband Noise for Rotor and Stator Cascade with Inhomogeneous Inflow Turbulence including Effects of Lean and Sweep; Contractor Report CR-210762; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Glegg, S.A.L.; Jochault, C. Broadband self-noise from a ducted fan. AIAA J. 1998, 36, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.N. Discrete Frequency Sound Generation in Axial Flow Turbomachines; H.M. Stationery Office: Richmond, UK, 1973; Volume 3709, pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ventres, C.S.; Theobald, M.A.; Mark, W.D. Turbofan Noise Generation, Volume 1: Analysis; Contractor Report CR-167952; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1982.

- Nallasamy, M.; Envia, E. Computation of rotor wake turbulence noise. J. Sound Vib. 2005, 282, 649–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posson, H.; Roger, M.; Moreau, S. On a uniformly valid analytical rectilinear cascade response function. J. Fluid Mech. 2010, 663, 22–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posson, H.; Moreau, S.; Roger, M. On the use of a uniformly valid analytical cascade response function for fan broadband noise predictions. J. Sound Vib. 2010, 329, 3721–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posson, H.; Moreau, S.; Roger, M. Broadband noise prediction of fan outlet guide vane using a cascade response function. J. Sound Vib. 2011, 330, 6153–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, V.; Posson, H.; Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S.; Roger, M. Fan-OGV interaction broadband noise prediction in a rigid annular duct with swirling and sheared mean flow. In Proceedings of the 22nd AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2016-2944), Lyon, France, 30 May–1 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, S.; Roger, M.; Jurdic, V. Effect of angle of attack and airfoil shape on Turbulence-Interaction Noise. In Proceedings of the 11th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference Meeting and Exhibit (AIAA 2005-2973), Monterey, CA, USA, 23–25 May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, S.M. Fan broadband interaction noise modeling using a low-order method. J. Sound Vib. 2015, 346, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadidi, B.; Atassi, H.M. Sound generation and scattering from radial vanes in uniform flow. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference of Fluid Dynamics and Propulsion (ICFDP7), Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, 18–20 December 2001; Volume AAC-3. [Google Scholar]

- François, B.; Bouley, S.; Roger, M.; Moreau, S. Analytical models based on a mode-matching technique for turbulence impingement noise on axial-flow outlet guide vanes. In Proceedings of the 22nd AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference and Exhibit (AIAA 2016-2947), Lyon, France, 30 May–1 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schram, C.; Christophe, J.; Shur, M.; Strelets, M.; Travin, A.; Wolhbrandt, A.; Guérin, S.; Ewert, R.; Martinez-Lera, P.; Tournour, M.; et al. Fan noise predictions using scale-resolved, statistical, stochastic and semi-analytical models. In Proceedings of the 23rd AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference and Exhibit (AIAA 2017-3386), Denver, CO, USA, 5–9 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- François, B.; Roger, M.; Moreau, S. Cascade trailing-edge noise modeling using a mode-matching technique and the edge-dipole theory. J. Sound Vib. 2016, 382, 310–327. [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld, T.; Rudgyard, M. Steady and Unsteady Flows Simulations Using the Hybrid Flow Solver AVBP. AIAA J. 1999, 37, 1378–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévèque, E.; Toschi, F.; Shao, L.; Bertoglio, J.P. Shear-Improved Smagorinsky model for large-eddy simulation of wall-bounded turbulent flows. J. Fluid Mech. 2007, 570, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoud, F.; Ducros, F. Subgrid-scale stress modelling based on the square of the velocity gradient. Flow Turb. Combust. 1999, 62, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagorinsky, J. General circulation experiments with the primitive equations: I. The basic experiment. Mon. Weather Rev. 1963, 91, 99–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Moreau, S.; Duchaine, F.; Gourdain, N.; Gicquel, L.Y.M. Large Eddy Simulations of the MT1 high-pressure turbine using TurboAVBP. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference of the CFD Society of Canada, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 6–9 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Papadogiannis, D.; Duchaine, F.; Gicquel, L.; Wang, G.; Moreau, S. Effects of SGS modeling on the deterministic and stochastic turbulent energetic distribution in LES of a high pressure turbine stage. J. Turbomach. 2016, 138, 091005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Duchaine, F.; Papadogiannis, D.; Duran, I.; Moreau, S.; Gicquel, L. An overset grid method for large eddy simulation of turbomachinery stages. J. Comput. Phys. 2014, 274, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Laborderie, J.; Duchaine, F.; Gicquel, L.Y.M.; Vermorel, O.; Wang, G.; Moreau, S. Numerical analysis of a high-order unstructured overset grid method for compressible LES of turbomachinery. J. Comput. Phys. 2018, 363, 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, O.; Rudgyard, M. Development of high-order Taylor-Galerkin schemes for unsteady calculations. J. Comput. Phys. 2000, 162, 338–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, P.D.; Wendroff, B. Difference schemes for hyperbolic equations with high order of accuracy. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1964, 17, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S.; Papadogiannis, D.; Duchaine, F.; Gicquel, L. Noise mechanisms in a transonic high-pressure turbine stage. Int. J. Aeroacoust. 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poinsot, T.; Lele, S. Boundary conditions for direct simulations of compressible viscous flows. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 101, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odier, N.; Sanjosé, M.; Gicquel, L.; Poinsot, T.; Moreau, S.; Duchaine, F. A characteristic inlet boundary condition for compressible, turbulent, multispecies turbomachinery flows. Comput. Fluids 2019, 178, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouret, G.; Gourdain, N.; Castillon, L. Adaptation of phase-lagged boundary conditions to Large Eddy Simulation in turbomachinery configurations. J. Turbomach. 2016, 138, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Laborderie, J.; Moreau, S.; Berry, A. Compressor Stage Broadband Noise Prediction using a Large-Eddy Simulation and Comparisons with a Cascade Response Model. In Proceedings of the 19th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2013-2042), Berlin, Germany, 27–29 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Moreau, S.; Duchaine, F.; de Laborderie, J.; Gicquel, L.Y.M. LES Investigation of Aerodynamics Performance in an Axial Compressor Stage. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the CFD Society of Canada, Toronto, ON, Canada, 1–4 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, T.M.; Michon, G.J.; Miton, H.; Vassilieff, N. Laser Doppler Anemometry Measurements in an Axial Compressor Stage. J. Propuls. Power 2001, 17, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.; Smith, A.D.; Chana, K.S.; Povey, T. Effect of Temperature Nonuniformity on Heat Transfer in an Unshrouded Transonic HP Turbine: An Experimental and Computational Investigation. J. Turbomach. 2014, 134, 011005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livebardon, T.; Moreau, S.; Gicquel, L.; Poinsot, T.; Bouty, E. Combining LES of combustion chamber and an actuator disk theory to predict combustion noise in a helicopter engine. Combust. Flames 2016, 165, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadogiannis, D.; Duchaine, F.; Gicquel, L.; Wang, G.; Moreau, S.; Nicoud, F. Assessment of the indirect combustion noise generated in a transonic high-pressure turbine stage. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2016, 138, 041503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpsty, N.A.; Marble, F.E. The interaction of entropy fluctuations with turbine blade rows—A mechanism of turbojet engine noise. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1977, 357, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyko, M.; Duran, I.; Moreau, S.; Nicoud, F.; Poinsot, T. Simulation and Modelling of the waves transmission and generation in a stator blade row in a combustion-noise framework. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 6090–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauerheim, M.; Duran, I.; Livebardon, T.; Wang, G.; Moreau, S.; Poinsot, T. Transmission and reflection of acoustic and entropy waves through a stator-rotor stage. J. Sound Vib. 2016, 374, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril, C.; Moreau, S.; Gicquel, L.Y.M. Study of Combustion Noise Generation in a Realistic Turbine Stage Configuration; GT2018-75062; ASME Turbo Expo: Oslo, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, P. Dynamic Mode Decomposition of numerical and experimental data. J. Fluid Mech. 2010, 656, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, T.; Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S.; Duchaine, F. Large Eddy Simulation of a scale-model turbofan for fan noise source diagnostic. In Proceedings of the 22nd AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2016-3000), Lyon, France, 30 May–1 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Arroyo, C.; Leonard, T.; Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S.; Duchaine, F. Large Eddy Simulation of a Scale-model Turbofan for Fan Noise Source Diagnostic. In Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on Transport Phenomena and Dynamics of Rotating Machinery, Lahaina, HI, USA, 16–21 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Arroyo, C.; Leonard, T.; Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S.; Duchaine, F. Large Eddy Simulation of a rotor stage for Fan Noise Source Diagnostic. In Proceedings of the Global Power and Propulsion Forum, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–9 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.; Jeracki, R.; Woodward, R.; Miller, C. Fan Noise Source Diagnostic Test-Rotor Alone Aerodynamic Performance Results. In Proceedings of the 8th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference & Exhibit (AIAA-2002-2426), Breckenridge, CO, USA, 17–19 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau, V.; Polacsek, C.; Castillon, L.; Marty, J.; Gervais, Y.; Moreau, S. Turbofan broadband noise predictions using a 3D ZDES rotor blade approach. In Proceedings of the 22nd AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference and Exhibit (AIAA 2016-2950), Lyon, France, 30 May–1 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, R.P.; Hughes, C.E.; Jeracki, R.J.; Miller, C.J. Fan Noise Source Diagnostic Test-Far-Field Acoustic Results; Technical Memorandum TM-2002-211591; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- Casalino, D.; Hazir, A.; Mann, A. Turbofan Broadband Noise Prediction Using the Lattice Boltzmann Method. AIAA J. 2018, 56, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, D.; Avallone, F.; Gonzales-Martino, I.; Ragni, D. Aeroacoustic study of a wavy stator leading edge in a realistic fan/OGV stage. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Transport Phenomena and Dynamics of Rotating Machinery (ISROMAC-17), Maui, HI, USA, 16–21 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Martino, I.; Casalino, D. Fan Tonal and Broadband Noise Simulations at Transonic Operating Conditions Using Lattice–Boltzmann Methods. In Proceedings of the 24th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (AIAA 2018-3395), Atlanta, GA, USA, 25–29 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Case | Cells | CPU Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 13 × 10 | 50–150 | 4 × 10 |

| M2 | 41 × 10 | 4–120 | 3 × 10 |

| M3 | 68 × 10 | 2–30 | 1.7 × 10 |

| M4 | 129 × 10 | 1–15 | 8 × 10 |

| Case | (kg/s) | (m/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | 26.44 | 1.159 | 112.42 |

| RANS-RS | 26.14 | 1.160 | 107.01 |

| LES-RS | 25.77 | 1.162 | 105.40 |

| LES-RO | 26.72 | 1.171 | 105.65 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreau, S. Turbomachinery Noise Predictions: Present and Future. Acoustics 2019, 1, 92-116. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1010008

Moreau S. Turbomachinery Noise Predictions: Present and Future. Acoustics. 2019; 1(1):92-116. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreau, Stéphane. 2019. "Turbomachinery Noise Predictions: Present and Future" Acoustics 1, no. 1: 92-116. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1010008

APA StyleMoreau, S. (2019). Turbomachinery Noise Predictions: Present and Future. Acoustics, 1(1), 92-116. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1010008