Atomic Layer Deposition of Oxide-Based Nanocoatings for Regulation of AZ31 Alloy Biocorrosion in Ringer’s Solution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) of Coatings

2.3. Sample Characterisation

2.4. Electrochemical Corrosion Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Thickness and Surface Morphology of ALD Coatings

3.1.1. Thickness Measurement of Oxide Coatings

3.1.2. Surface Morphology of Oxide Coatings with Different Thickness

3.1.3. Surface Morphology of Mixed Oxide Coatings

3.2. Composition of ALD Coatings

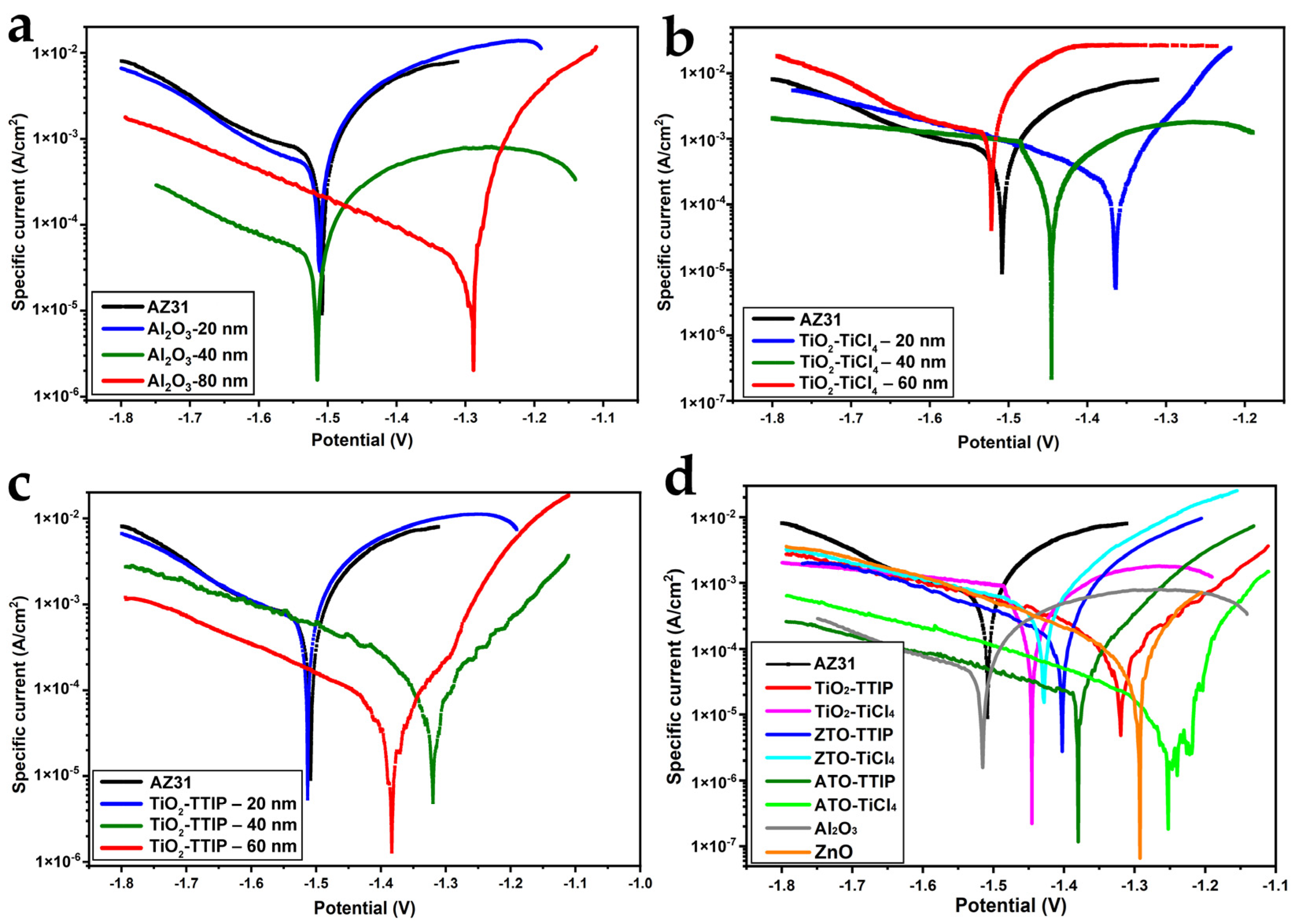

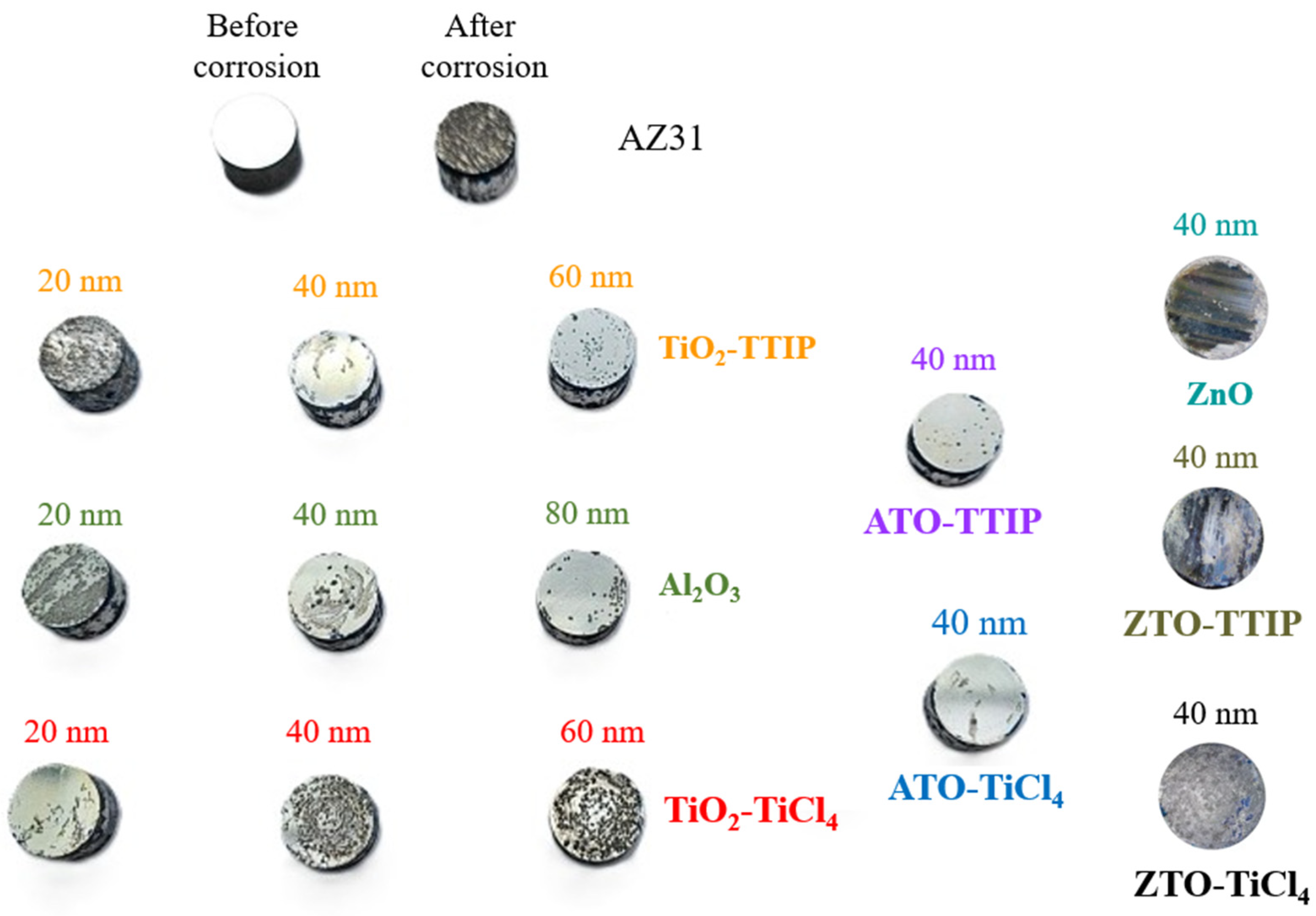

3.3. Potentiodynamic Polarisation Tests

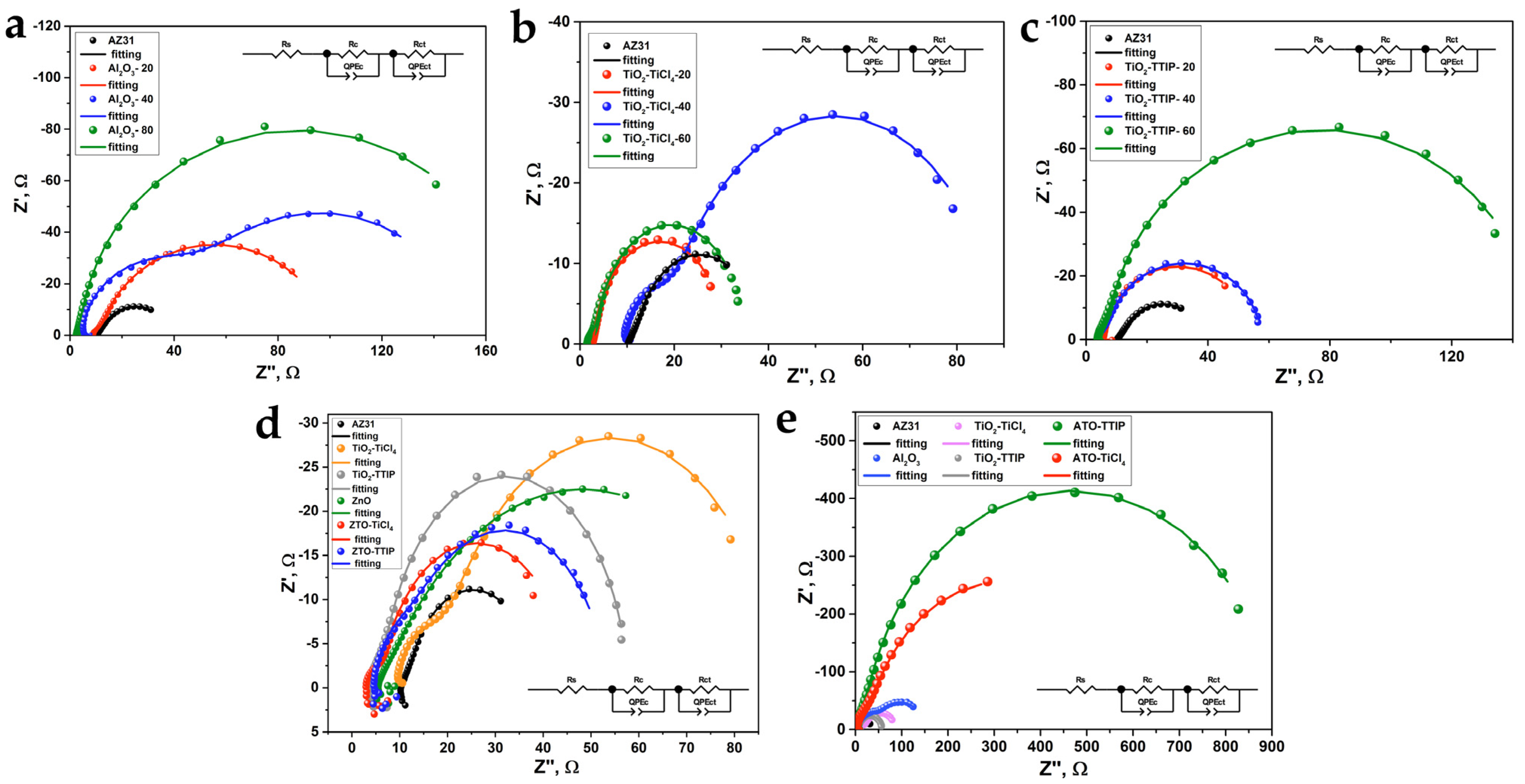

3.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Tiwari, S.K. Research Progress on Corrosion Behavior of Magnesium Alloy Composites in Practical Service Conditions. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, e00660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, P.; Narendranath, S.; Desai, V. Recent progress in in vivo studies and clinical applications of magnesium based biodegradable implants—A review. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Miao, J.; Balasubramani, N.; Cho, D.H.; Avey, T.; Chang, C.-Y.; Luo, A.A. Magnesium research and applications: Past, present and future. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 3867–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Liu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Shi, Z.; Pan, X. Biodegradable Medical Implants: Reshaping Future Medical Practice. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e08014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Salaha, Z.F.; Abdullah, N.N.A.A.; Chan, K.F.; Gan, H.-S.; Mohd Yusop, M.Z.; Ramlee, M.H. Biodegradable orthopaedic implants: A systematic review of in vitro and in vivo evaluations of magnesium, iron, and zinc alloys. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Gu, X.N.; Witte, F. Biodegradable metals. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2014, 77, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonfa, B.K.; Jiru, M.G.; Esleman, E.A. Advancing metallic implant: A review of magnesium alloys as bio-absorbable alternatives to orthopedic devices. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, Y.; Zou, D.; Zu, H.; Li, W.; Zheng, Y. An overview of magnesium-based implants in orthopaedics and a prospect of its application in spine fusion. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 39, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty Banerjee, P.; Al-Saadi, S.; Choudhary, L.; Harandi, S.E.; Singh, R. Magnesium Implants: Prospects and Challenges. Materials 2019, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amara, H.; Martinez, D.C.; Shah, F.A.; Loo, A.J.; Emanuelsson, L.; Norlindh, B.; Willumeit-Romer, R.; Plocinski, T.; Swieszkowski, W.; Palmquist, A.; et al. Magnesium implant degradation provides immunomodulatory and proangiogenic effects and attenuates peri-implant fibrosis in soft tissues. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 26, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, T.; Kuhlmann, J.; Dong, Z.; Chen, S.; Joshi, M.; Salunke, P.; Shanov, V.N.; Hong, D.; Kumta, P.N.; et al. In vivo monitoring the biodegradation of magnesium alloys with an electrochemical H2 sensor. Acta Biomater. 2016, 36, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Helmholz, H.; Willumeit-Römer, R. Peri-implant gas accumulation in response to magnesium-based musculoskeletal biomaterials: Reframing current evidence for preclinical research and clinical evaluation. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Shuai, C.; Yang, Y. Surface Coatings on Biomedical Magnesium Alloys. Materials 2025, 18, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Batra, U.; Kumar, K.; Ahuja, N.; Mahapatro, A. Progress in bioactive surface coatings on biodegradable Mg alloys: A critical review towards clinical translation. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 19, 717–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarian, M.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sotoudehbagha, P.; Razavi, M.; Ahmed, Q.U.; Sukotjo, C.; Hermawan, H. Potential bioactive coating system for high-performance absorbable magnesium bone implants. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 12, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capitaine, B.P.D.; López, A.G.M.; Magaña, J.C.T.; Aguilar, G.G.; Reyes, J.L.R. Electrochemical characterization of conversion coatings of phosphates plus nanostructured TiO2 over magnesium in a simulated body fluid. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2023, 27, 3091–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommiers, S.; Frayret, J.; Castetbon, A.; Potin-Gautier, M. Alternative conversion coatings to chromate for the protection of magnesium alloys. Corros. Sci. 2014, 84, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati Darband, G.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Hamghalam, P.; Valizade, N. Plasma electrolytic oxidation of magnesium and its alloys: Mechanism, properties and applications. J. Magnes. Alloys 2017, 5, 74–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashtalyar, D.V.; Imshinetskiy, I.M.; Kashepa, V.V.; Nadaraia, K.V.; Piatkova, M.A.; Pleshkova, A.I.; Fomenko, K.A.; Ustinov, A.Y.; Sinebryukhov, S.L.; Gnedenkov, S.V. Effect of Ta2O5 nanoparticles on bioactivity, composition, structure, in vitro and in vivo behavior of PEO coatings on Mg-alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 2360–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Mei, J.; Ouyang, J.; Wu, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; He, Y.; Zheng, W.; Li, H.; Lu, C.; et al. Structure and corrosion resistance of electron-beam-strengthened and micro-arc oxidized coatings on magnesium alloy AZ31. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2023, 41, 053101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Yuan, M.; Xun, M.; Zhang, H. Progress in the study of micro-arc oxidation film layers on biomedical metal surfaces. Corros. Rev. 2025, 43, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Pan, X.; Yang, W.; Cai, K.; Chen, Y. Al2O3–ZrO2 ceramic coatings fabricated on WE43 magnesium alloy by cathodic plasma electrolytic deposition. Mater. Lett. 2012, 70, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Peng, G.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Fang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Wu, J. The fabrication of a CeO2 coating via cathode plasma electrolytic deposition for the corrosion resistance of AZ31 magnesium alloy. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 19885–19891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarka, M.; Dikici, B.; Niinomi, M.; Ezirmik, K.V.; Nakai, M.; Yilmazer, H. A systematic study of β-type Ti-based PVD coatings on magnesium for biomedical application. Vacuum 2021, 183, 109850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoche, H.; Schmidt, J.; Groß, S.; Troßmann, T.; Berger, C. PVD coating and substrate pretreatment concepts for corrosion and wear protection of magnesium alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, S145–S150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, E.; Duran, A.; Cere, S.; Castro, Y. Hybrid Epoxy-Alkyl Sol-Gel Coatings Reinforced with SiO2 Nanoparticles for Corrosion Protection of Anodized AZ31B Mg Alloy. Gels 2022, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Le, Q.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, C.; Guo, R.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, X. The growth and corrosion mechanism of Zn-based coating on AZ31 magnesium alloys by novel hot-dip process. Mater. Charact. 2022, 189, 111988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, A.; Szindler, M.M.; Szindler, M. Structure and Corrosion Behavior of TiO2 Thin Films Deposited by ALD on a Biomedical Magnesium Alloy. Coatings 2021, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Lin, K.F.; Chiu, C.; Semenov, V.I.; Lin, H.C.; Chen, M.J. Effect of atomic layer plasma treatment on TALD-ZrO2 film to improve the corrosion protection of Mg-Ca alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 427, 127811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Yuan, W.; Zheng, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Wu, S. A combined coating strategy based on atomic layer deposition for enhancement of corrosion resistance of AZ31 magnesium alloy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 434, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, M.; Berto, F.; Torgersen, J. Stress corrosion cracking behavior of zirconia ALD–coated AZ31 alloy in simulated body fluid. Mater. Des. Process. Commun. 2019, 2, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, M.; Cogo, S.; Bjelland, M.; Bin Afif, A.; Dadlani, A.; Greggio, E.; Berto, F.; Torgersen, J. On the evaluation of ALD TiO2, ZrO2 and HfO2 coatings on corrosion and cytotoxicity performances. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 1806–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, V.; Puurunen, R.L.; Dendooven, J. Conformality in atomic layer deposition: Current status overview of analysis and modelling. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2019, 6, 21302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.M. Atomic Layer Deposition: An Overview. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessels, E.; Devi, A.; Park, J.-S.; Ritala, M.; Yanguas-Gil, A.; Wiemer, C. Atomic layer deposition. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2025, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yuan, W.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Pan, H.; Wu, S. Atomic layer deposited ZrO2 nanofilm on Mg-Sr alloy for enhanced corrosion resistance and biocompatibility. Acta Biomater 2017, 58, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, L.A.; Vartiajnen, V.V.; Kirichenko, S.O.; Rytova, M.A.; Godun, A.P.; Kolesnichenko, Y.V.; Yudintceva, N.M.; Kalganov, V.D.; Lozhkin, M.S.; Morozova, N.E.; et al. Regulation of biocorrosion of AZ31-type magnesium alloy by atomic layer deposition of Al2O3 nanocoatings. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 69, 106775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Luo, L.; Xiong, L.; Liu, Y. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of ALD Al2O3 film on AZ31 magnesium alloy with different surface roughness. J. Magnes. Alloys 2020, 8, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-C.; Lin, K.; Lin, Y.-H.; Yang, K.-C.; Semenov, V.I.; Lin, H.-C.; Chen, M.-J. Improvement of Corrosion Resistance and Biocompatibility of Biodegradable Mg–Ca Alloy by ALD HfZrO2 Film. Coatings 2022, 12, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, M.; Bin Afif, A.; Dadlani, A.L.; Berto, F.; Torgersen, J. Improving stress corrosion cracking behavior of AZ31 alloy with conformal thin titania and zirconia coatings for biomedical applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 111, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peron, M.; Bertolini, R.; Cogo, S. On the corrosion, stress corrosion and cytocompatibility performances of ALD TiO2 and ZrO2 coated magnesium alloys. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 125, 104945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chang, R.; Webster, T.J. Atomic Layer Deposition Coating of TiO2 Nano-Thin Films on Magnesium-Zinc Alloys to Enhance Cytocompatibility for Bioresorbable Vascular Stents. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9955–9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-J.; Yang, K.-C.; Lin, P.-C.; Lin, K.; Chen, M.-J.; Wang, C.-C.; Chiu, C.; Lin, H.-C. Multilayer Al2O3/ZrO2 coatings via PEALD for enhanced corrosion resistance and biocompatibility of biodegradable Mg–Ca alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 345, 131297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, D.; Ezhov, I.; Yudintceva, N.; Mitrofanov, I.; Shevtsov, M.; Rudakova, A.; Maximov, M. MG-63 and FetMSC Cell Response on Atomic Layer Deposited TiO2 Nanolayers Prepared Using Titanium Tetrachloride and Tetraisopropoxide. Coatings 2022, 12, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, D.; Kozlova, L.; Rudakova, A.; Zemtsova, E.; Yudintceva, N.; Ovcharenko, E.; Koroleva, A.; Kasatkin, I.; Kraeva, L.; Rogacheva, E.; et al. Atomic Layer Deposition of Chlorine Containing Titanium–Zinc Oxide Nanofilms Using the Supercycle Approach. Coatings 2023, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaily, M.; Svensson, J.E.; Fajardo, S.; Birbilis, N.; Frankel, G.S.; Virtanen, S.; Arrabal, R.; Thomas, S.; Johansson, L.G. Fundamentals and advances in magnesium alloy corrosion. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 89, 92–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, D.; Lamaka, S.V.; Lu, X.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Selecting medium for corrosion testing of bioabsorbable magnesium and other metals—A critical review. Corros. Sci. 2020, 171, 108722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, J.-P.; Marin, G.; Karppinen, M. Titanium dioxide thin films by atomic layer deposition: A review. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2017, 32, 093005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Tong, H.; Ye, X.; Wang, K.; Yuan, X.; Liu, C.; Li, H. Growth and atomic oxygen erosion resistance of Al2O3-doped TiO2 thin film formed on polyimide by atomic layer deposition. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 34833–34842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulagatov, A.I.; Yan, Y.; Cooper, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Gibbs, Z.M.; Cavanagh, A.S.; Yang, R.G.; Lee, Y.C.; George, S.M. Al2O3 and TiO2 atomic layer deposition on copper for water corrosion resistance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 4593–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, M.A.; Oldham, C.J.; Parsons, G.N. Investigation of the Corrosion Behavior of Atomic Layer Deposited Al2O3/TiO2 Nanolaminate Thin Films on Copper in 0.1 M NaCl. Materials 2019, 12, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarov, D.V.; Kozlova, L.A.; Yudintceva, N.M.; Ovcharenko, E.A.; Rudakova, A.V.; Kirichenko, S.O.; Rogacheva, E.V.; Kraeva, L.A.; Borisov, E.V.; Popovich, A.A.; et al. Atomic layer deposition of biocompatible multifunctional ZnO-TiO2 nanocoatings on the surface of additively manufactured nitinol. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 675, 160974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Precursors | Estimated Thickness, nm | Number of Cycles | Number of Supercycles | Thickness, nm (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 | Al(CH3)3 | 20 | 160 | - | 20.4 |

| 40 | 320 | - | 39.6 | ||

| 80 | 640 | - | 78.2 | ||

| TiO2 | TiCl4 | 20 | 365 | - | 18.5 |

| 40 | 730 | - | 37.8 | ||

| 60 | 1095 | - | 59.9 | ||

| TTIP | 20 | 500 | - | 17.3 | |

| 40 | 1000 | - | 35.6 | ||

| 60 | 1500 | - | 57.6 | ||

| ZnO | Zn(C2H5)2 | 40 | 222 | - | 39.8 |

| ZTO | TTIP, Zn(C2H5)2 | 40 | 364 | 182 | 40.2 |

| TiCl4, Zn(C2H5)2 | 40 | 340 | 170 | 41.5 | |

| ATO | TTIP, Al(CH3)3 | 40 | 500 | 250 | 37.1 |

| TiCl4, Al(CH3)3 | 40 | 460 | 230 | 37.6 |

| Sample | O, at. % | Mg, at. % | Al, at. % | Cl, at. % | Ti, at. % | Zn, at. % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2-TTIP | 18.01 | 73.75 | 3.87 | - | 3.91 | 0.44 |

| TiO2-TiCl4 | 35.32 | 54.94 | 3.09 | 0.49 | 5.81 | 0.35 |

| ZTO-TTIP | 9.06 | 86.83 | 2.80 | - | 0.23 | 1.08 |

| ZTO-TiCl4 | 6.35 | 89.72 | 3.06 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.49 |

| ATO-TTIP | 9.90 | 85.01 | 4.41 | - | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| ATO-TiCl4 | 21.22 | 70.86 | 6.10 | 0.09 | 1.20 | 0.52 |

| Al2O3 | 27.19 | 61.17 | 11.30 | - | - | 0.34 |

| Coating | Thickness, nm | Icorr, A/cm2 | E0, B | Corrosion Rate, mm/Year | Polarisation Resistance, Ohm*cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ31 | 0 | 7.29 × 104 | −1.508 | 16.09 | 28.5 |

| Al2O3 | 20 | 4.56 × 104 | −1.513 | 10.05 | 24.9 |

| 40 | 4.25 × 105 | −1.514 | 0.94 | 78.6 | |

| 80 | 4.01 × 105 | −1.289 | 0.88 | 158.0 | |

| TiO2-TTIP | 20 | 5.96 × 104 | −1.515 | 13.14 | 23.9 |

| 40 | 2.22 × 104 | −1.319 | 4.90 | 227.1 | |

| 60 | 6.20 × 105 | −1.384 | 1.37 | 508.3 | |

| TiO2-TiCl4 | 20 | 3.83 × 104 | −1.364 | 8.44 | 73.2 |

| 40 | 8.07 × 104 | −1.445 | 17.81 | 75.5 | |

| 60 | 1.17 × 103 | −1.523 | 25.82 | 5.8 |

| Sample | Icorr, A/cm2 | E0, B | Corrosion Rate, mm/Year | Polarisation Resistance, Ohm*cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ31 | 7.29 × 10−4 | −1.508 | 16.1 | 28.5 |

| ZnO | 6.62 × 10−5 | −1.292 | 1.46 | 260 |

| ZTO-TTIP | 2.15 × 10−4 | −1.403 | 4.73 | 94.2 |

| ZTO-TiCl4 | 4.24 × 10−4 | −1.427 | 9.36 | 51.5 |

| TiO2-TTIP | 2.22 × 10−4 | −1.319 | 4.90 | 227 |

| TiO2-TiCl4 | 8.07 × 10−4 | −1.445 | 17.8 | 75.5 |

| ATO-TTIP | 2.99 × 10−5 | −1.380 | 0.66 | 418 |

| ATO-TiCl4 | 1.35 × 10−5 | −1.246 | 0.30 | 3230 |

| Al2O3 | 4.25 × 10−5 | −1.514 | 0.94 | 78.6 |

| Thickness, nm | Rs, Ohm*cm2 | Rct, Ohm*cm2 | QPEct-Q, Ohm*cm−2 | QPEct-n | Rc, Ohm*cm2 | QPEc-Q, Ohm*cm−2 | QPEc-n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 26.7 | 63.8 | 2.92 × 10−6 | 0.98 | 8.4 | 4.29 × 10−6 | 0.83 |

| Al2O3 | |||||||

| 20 | 22.7 | 9.8 | 1.55 × 10−6 | 0.83 | 223 | 5.83 × 10−7 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 12.9 | 146 | 3.25 × 10−7 | 0.90 | 226 | 5.75 × 10−7 | 0.99 |

| 80 | 6.9 | 47.0 | 3.15 × 10−7 | 0.92 | 382 | 9.33 × 10−7 | 0.99 |

| TiO2-TTIP | |||||||

| 20 | 14.3 | 38.7 | 1.17 × 10−6 | 0.97 | 84.6 | 4.33 × 10−6 | 0.97 |

| 40 | 9.5 | 20.3 | 7.76 × 10−7 | 0.95 | 116 | 4.36 × 10−7 | 0.99 |

| 60 | 10.0 | 50.6 | 4.17 × 10−7 | 0.96 | 314 | 5.00 × 10−7 | 0.96 |

| TiO2-TiCl4 | |||||||

| 20 | 6.9 | 19.6 | 1.94 × 10−6 | 0.95 | 49.8 | 3.39 × 10−6 | 0.99 |

| 40 | 24.3 | 33.0 | 3.28 × 10−7 | 0.84 | 171 | 7.95 × 10−8 | 0.99 |

| 60 | 4.1 | 10.2 | 3.31 × 10−6 | 0.97 | 76.2 | 1.32 × 10−6 | 0.90 |

| Sample | Rs, Ohm*cm2 | Rct, Ohm*cm2 | QPEct-Q, Ohm*cm−2 | QPEct-n | Rc, Ohm*cm2 | QPEc-Q, Ohm*cm−2 | QPEc-n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ31 | 26.7 | 63.8 | 2.92 × 10−6 | 0.98 | 8.4 | 4.29 × 10−6 | 0.83 |

| ZnO | 14.0 | 6.9 | 2.33 × 10−6 | 0.98 | 210.3 | 2.14 × 10−6 | 0.61 |

| ZTO-TTIP | 12.2 | 36.0 | 6.54 × 10−7 | 0.85 | 87.9 | 3.18 × 10−7 | 0.99 |

| ZTO-TiCl4 | 7.4 | 12.0 | 9.45 × 10−7 | 0.86 | 97.5 | 2.28 × 10−7 | 0.94 |

| ATO-TTIP | 10.2 | 313 | 4.17 × 10−8 | 0.92 | 1982 | 7.60 × 10−8 | 0.99 |

| ATO-TiCl4 | 7.7 | 226 | 7.44 × 10−8 | 0.89 | 1321 | 7.17 × 10−8 | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nazarov, D.; Kozlova, L.; Vartiajnen, V.; Kirichenko, S.; Rytova, M.; Godun, A.P.; Maximov, M.; Ilina, A.; Combs, S.E.; Pitkin, M.; et al. Atomic Layer Deposition of Oxide-Based Nanocoatings for Regulation of AZ31 Alloy Biocorrosion in Ringer’s Solution. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd7010003

Nazarov D, Kozlova L, Vartiajnen V, Kirichenko S, Rytova M, Godun AP, Maximov M, Ilina A, Combs SE, Pitkin M, et al. Atomic Layer Deposition of Oxide-Based Nanocoatings for Regulation of AZ31 Alloy Biocorrosion in Ringer’s Solution. Corrosion and Materials Degradation. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazarov, Denis, Lada Kozlova, Vladislava Vartiajnen, Sergey Kirichenko, Maria Rytova, Anton P. Godun, Maxim Maximov, Alina Ilina, Stephanie E. Combs, Mark Pitkin, and et al. 2026. "Atomic Layer Deposition of Oxide-Based Nanocoatings for Regulation of AZ31 Alloy Biocorrosion in Ringer’s Solution" Corrosion and Materials Degradation 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd7010003

APA StyleNazarov, D., Kozlova, L., Vartiajnen, V., Kirichenko, S., Rytova, M., Godun, A. P., Maximov, M., Ilina, A., Combs, S. E., Pitkin, M., & Shevtsov, M. (2026). Atomic Layer Deposition of Oxide-Based Nanocoatings for Regulation of AZ31 Alloy Biocorrosion in Ringer’s Solution. Corrosion and Materials Degradation, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd7010003