Rubber-Induced Corrosion of Painted Automotive Steel: Inconspicuous Case of Galvanic Corrosion

Abstract

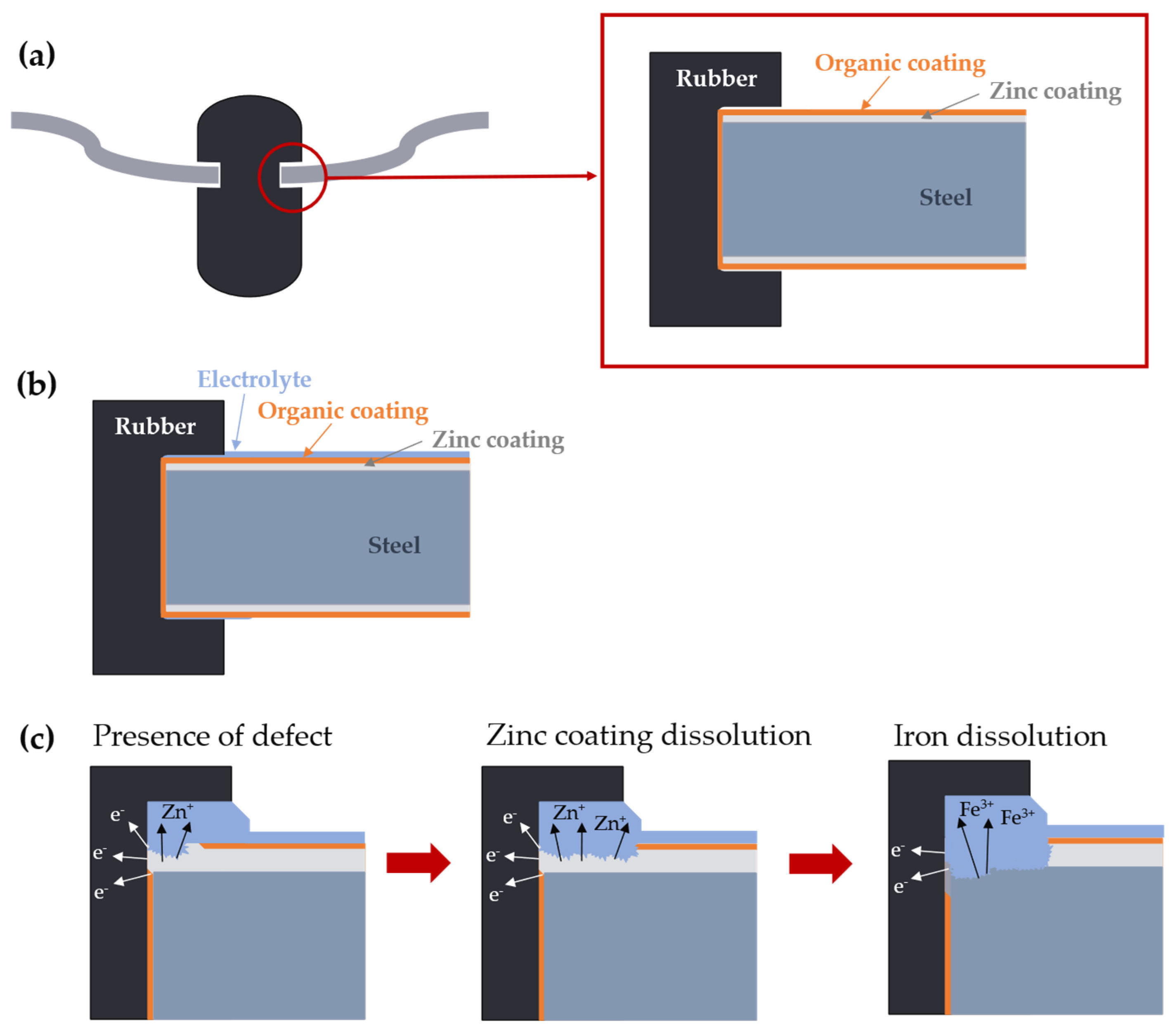

1. Introduction

- To confirm that galvanic coupling between rubber and galvanized automotive steel can accelerate corrosion.

- To connect and put into context results obtained using electrochemical methods and accelerated corrosion testing.

- To assess the risk of corrosion of painted automotive steel in contact with a series of rubber materials.

- To recommend an optimal approach to minimize the risk of accelerated corrosion of car parts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Volume Resistivity Measurement

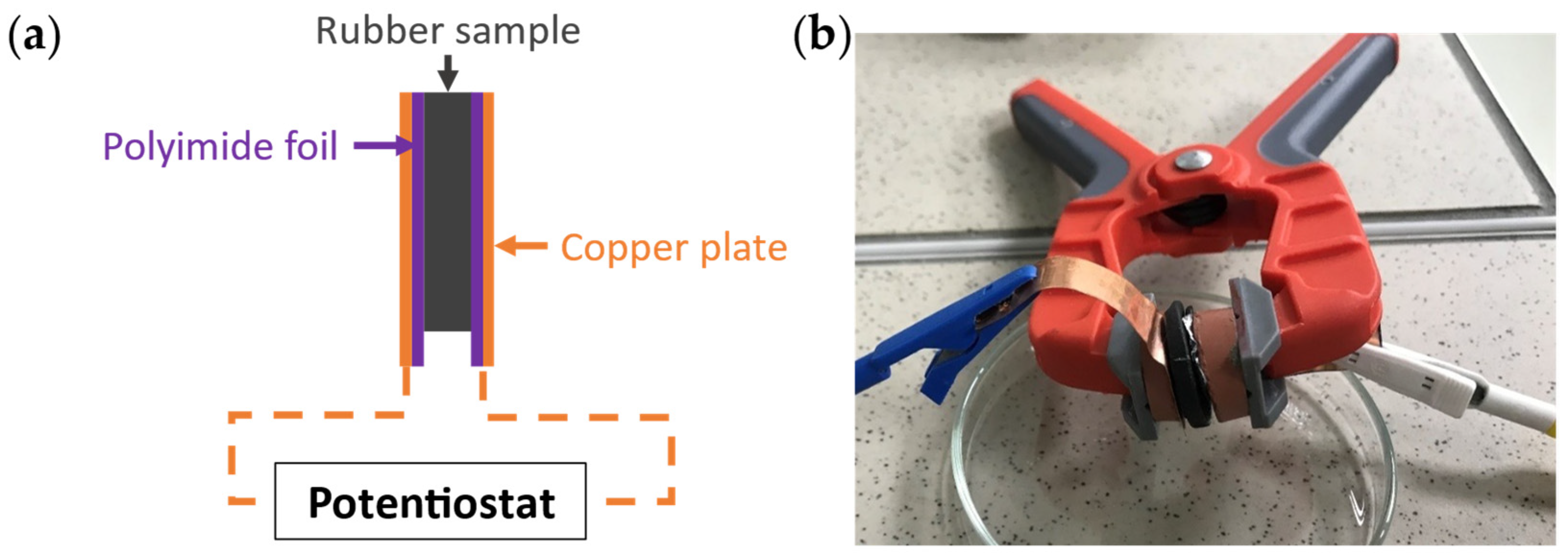

2.3. ZRA Measurement

2.4. Resistometric Corrosion Monitoring

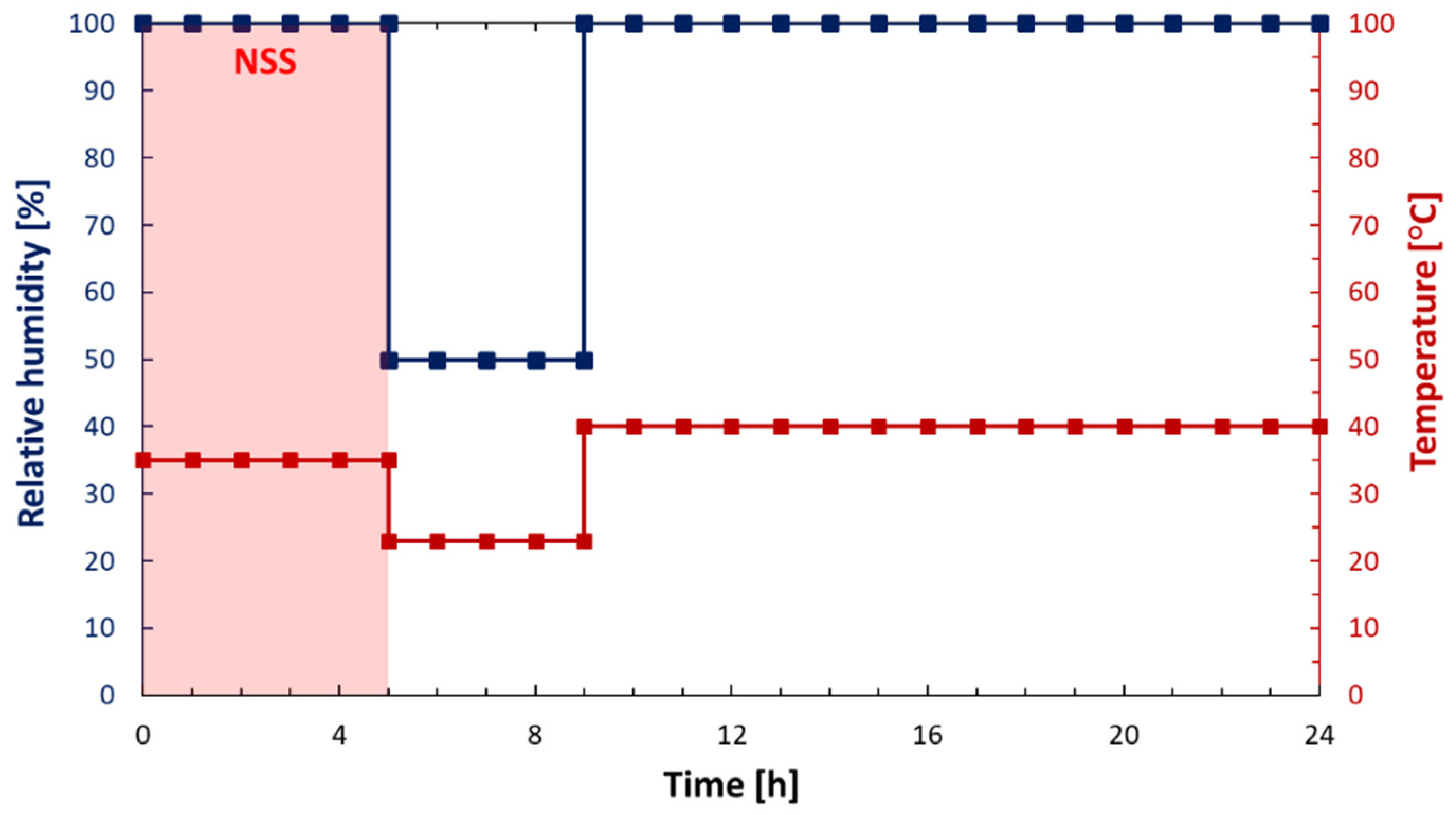

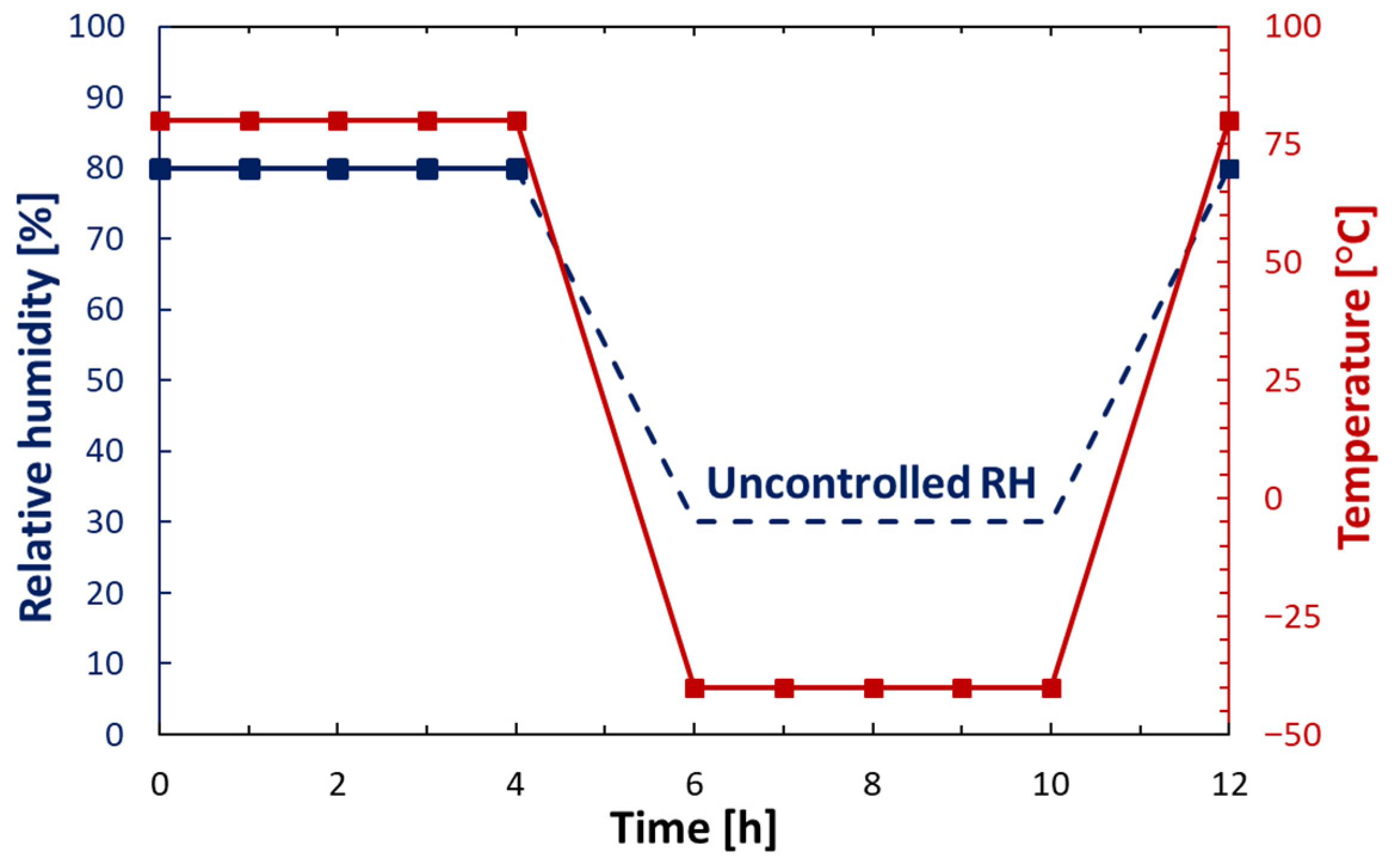

2.5. Accelerated Corrosion Test

3. Results

3.1. Volume Resistivity

3.2. ZRA

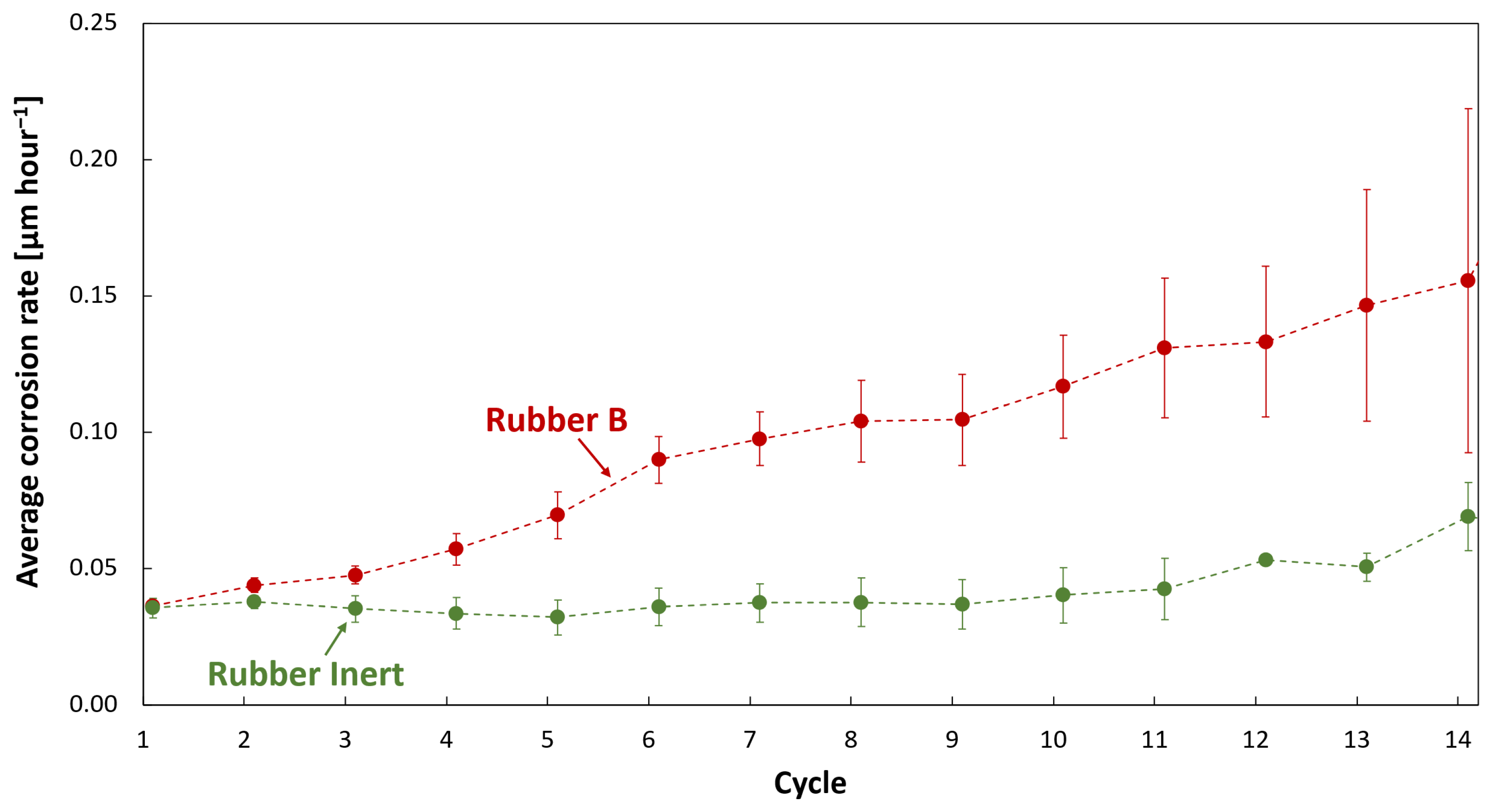

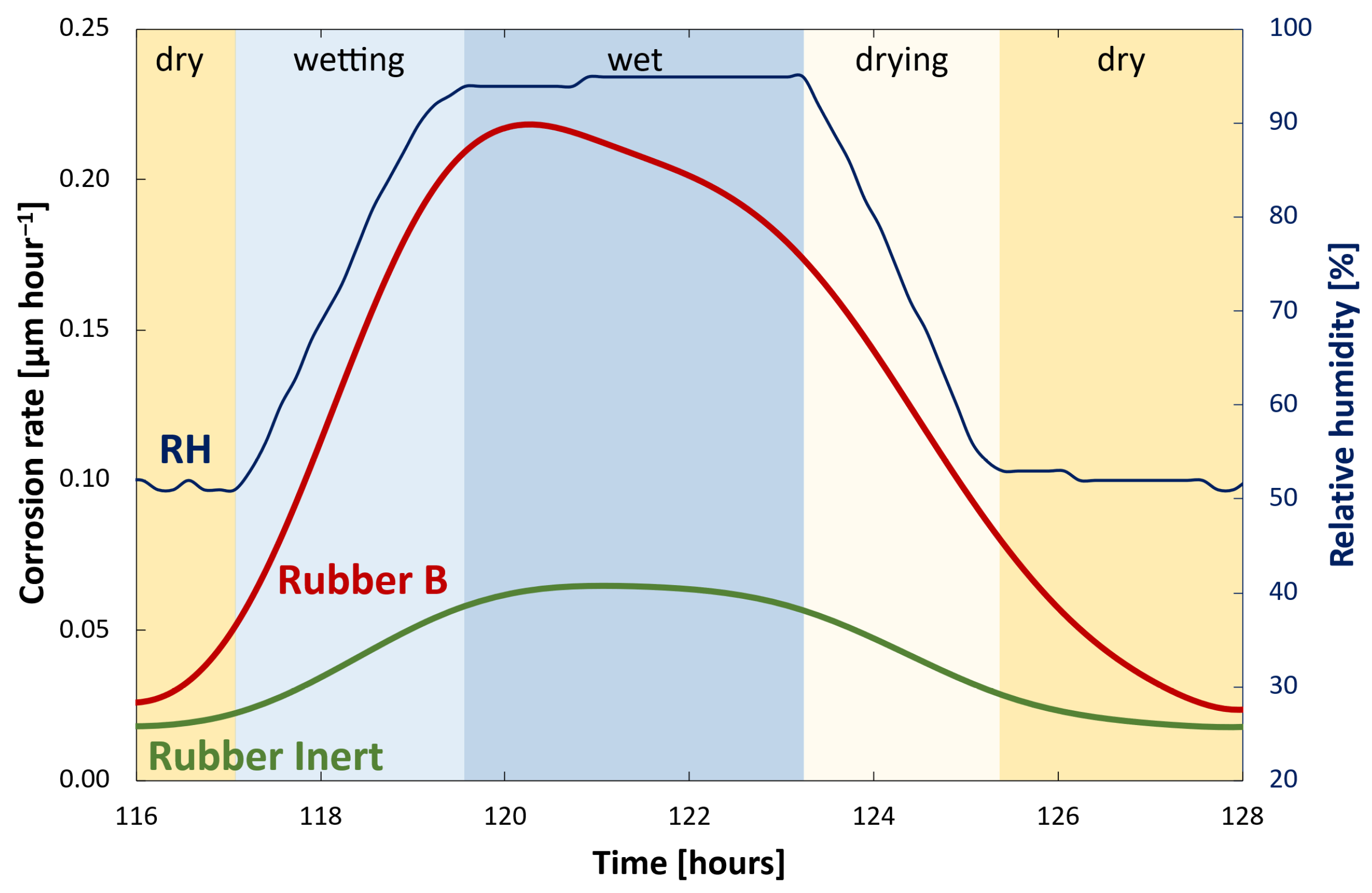

3.3. Corrosion Monitoring

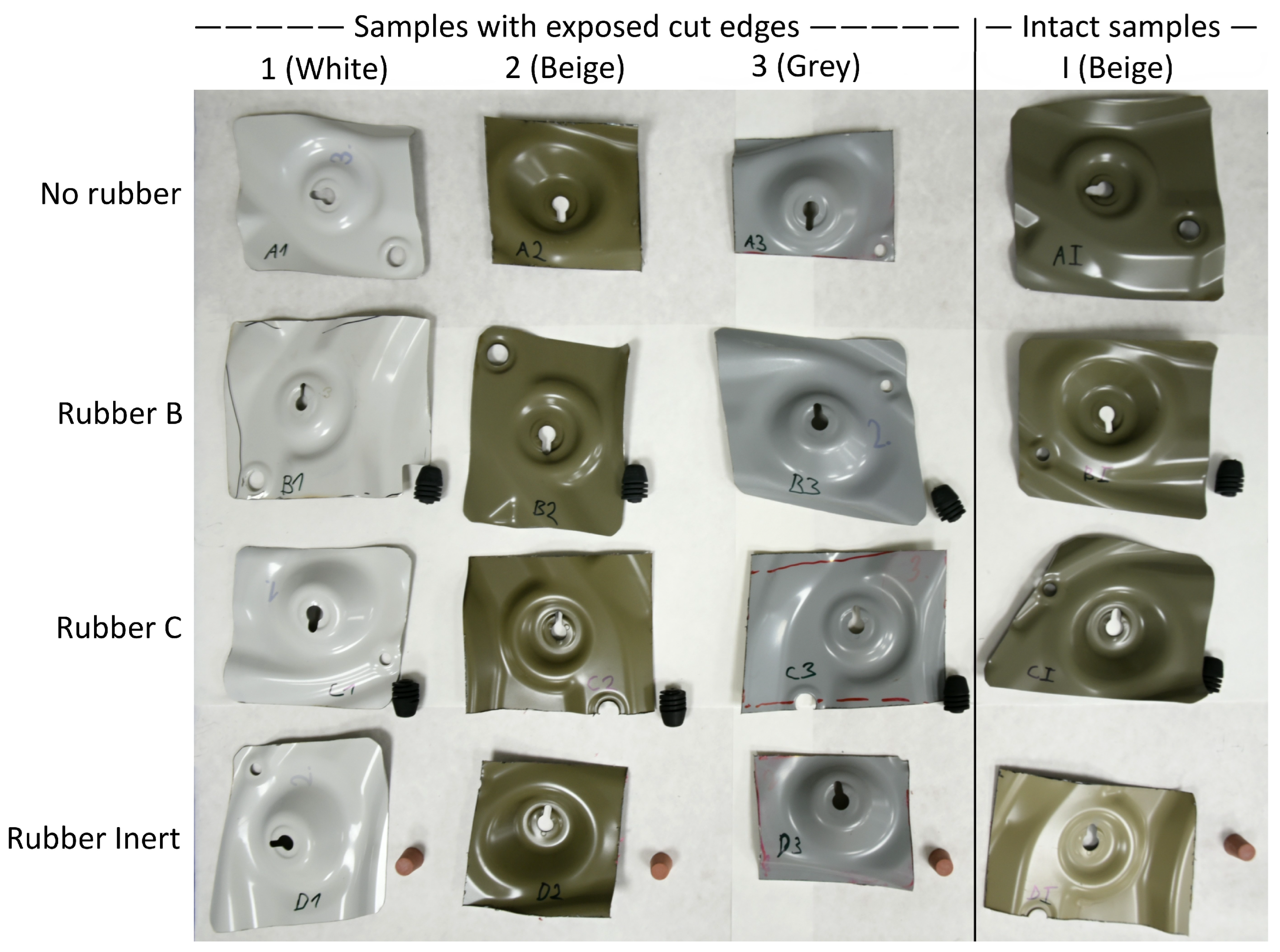

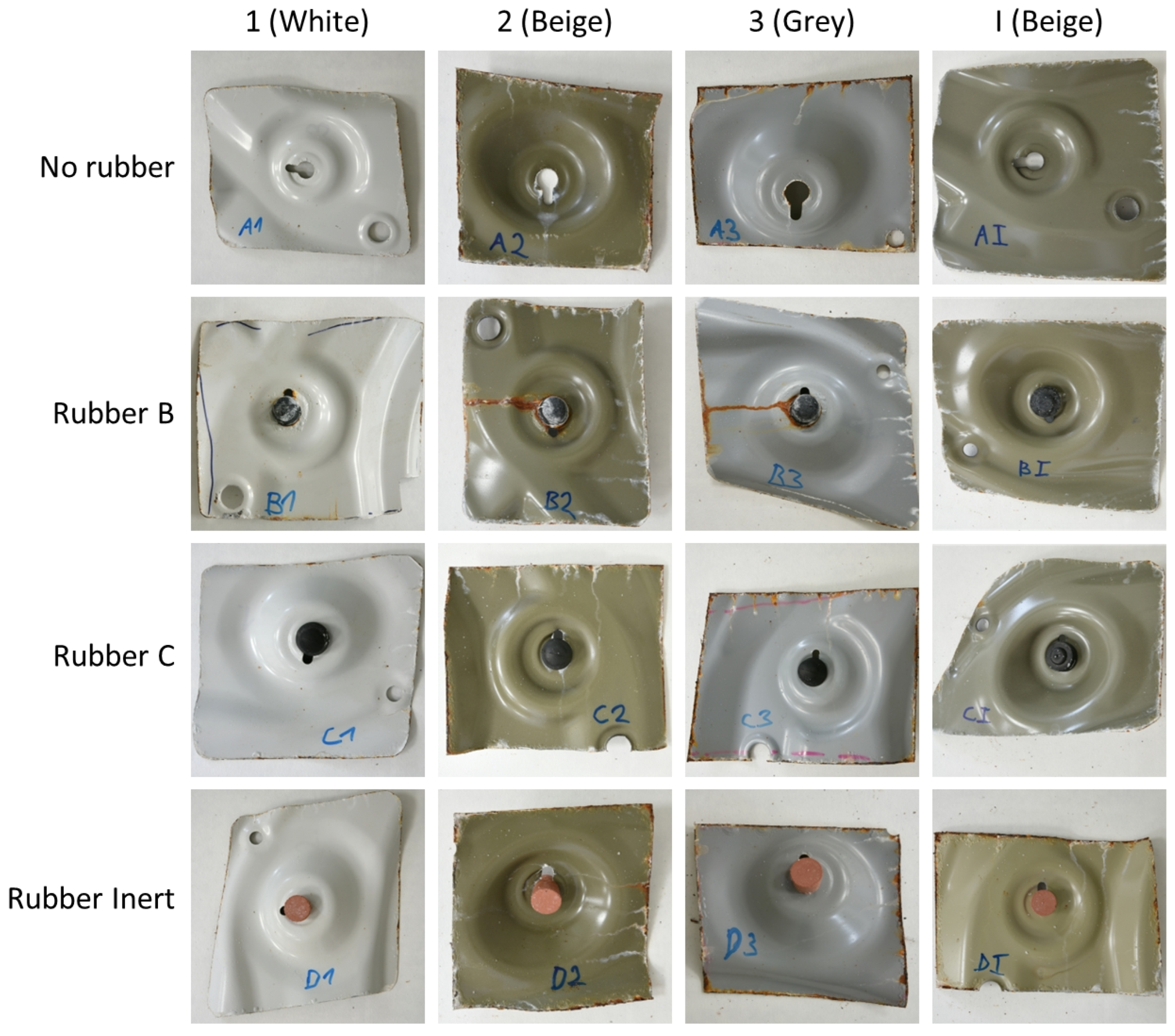

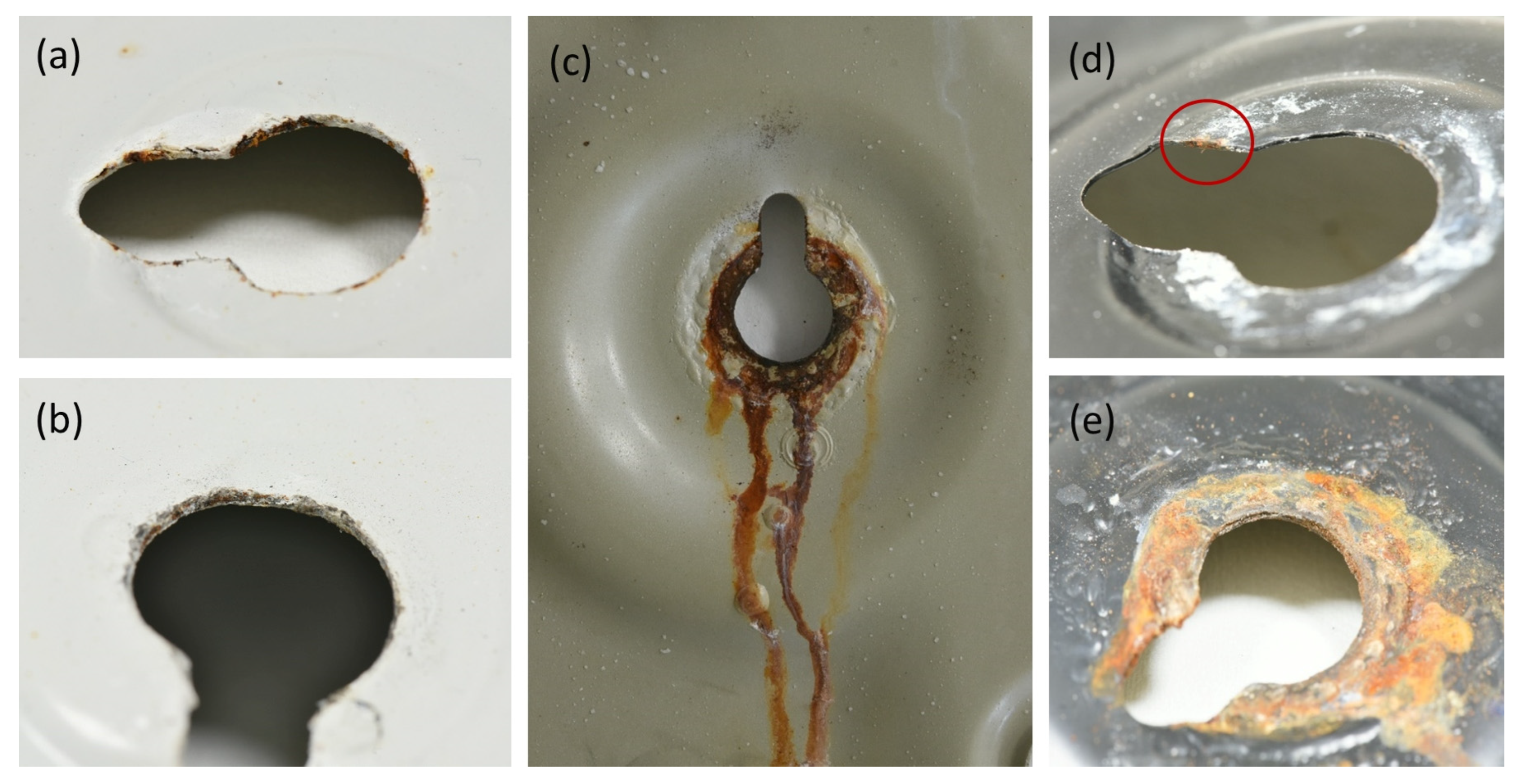

3.4. Accelerated Corrosion Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- In corrosive environments, the car body is susceptible to the acceleration of corrosion in defects due to galvanic coupling with carbon-filled rubber. The extent of paint delamination decreases with increasing rubber resistivity. Rubber with resistivity from about 104 Ω·m is considered safe in view of galvanic corrosion and corrosion acceleration.

- Laboratory galvanic current and even simple volume resistivity measurements correlated well with results of the accelerated cyclic corrosion test of painted automotive steel samples coupled with rubber and can therefore be used to estimate the risk of corrosion damage.

- The strict specification and verification of the electrical volume resistivity of rubber materials by automotive manufacturers is required to eliminate the potential detrimental effect of galvanic corrosion.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LeBozec, N.; Baudoin, J.-L.; Orain, V.; Thierry, D. Blistering on Painted Automotive Materials Induced by Galvanic Coupling with Rubber Material. Corrosion 2007, 63, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, V. Understand Electrochemical Corrosion in EPDM Compounds Due to Contact Between Dissimilar Metals in a Car Body. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hatemmi, M.H. A New Trend for Studying the Effects of Rubber Resistivity on the Corrosion Rate of Steel Cords in Rubber/Steel Composites. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 15, 4234–4246. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.-L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Zheng, D. Galvanic Activity of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers and Electrochemical Behavior of Carbon Fiber. Corros. Commun. 2023, 10, 88–89, Erratum in Corros. Commun. 2021, 1, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Yergin, M. Corrosion Avoidance in Lightweight Materials for Automotive Applications. npj Mater. Degrad. 2018, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, D.-J.; Song, G.-L. Galvanic Effect between Galvanized Steel and Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2017, 30, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Nie, X. Galvanic Corrosion Property of Contacts between Carbon Fiber Cloth Materials and Typical Metal Alloys in an Aggressive Environment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 215, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Tang, J.; Kainuma, S. Inhibition and Facilitation Mechanisms of Galvanic Corrosion between Carbon Fiber and Steel in Atmospheric Environments. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 297, 112332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Kainuma, S.; Niu, W.; Xie, J. Evaluation of Influence Factors for Galvanic Corrosion Coupled between Carbon Fiber Cloth and Carbon Steel. Zairyo-to-Kankyo 2023, 72, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J. Investigation on Galvanic Corrosion Behaviors of CFRPs and Aluminum Alloys Systems for Automotive Applications. Mater. Corros. 2019, 70, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adapala, P.; Hosking, N.; Nichols, M.; Frankel, G. Laboratory Accelerated Cyclic Corrosion Testing and On-Road Corrosion Testing of AA6××× Coupled to Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Plastics. Corrosion 2022, 78, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, L.; Olivier, M.-G. The Inhibition Efficiency of Different Species on AA2024/Graphite Galvanic Coupling Models Depicted by SVET. Corros. Sci. 2018, 136, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Ren, Y.; Wong, L.M.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. Galvanic Corrosion Protection of Al-Alloy in Contact with Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer through Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation Treatment. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Wu, G.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Ji, S.; Huang, Z. Galvanic Corrosion Behaviour of Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer/Magnesium Alloys Coupling. Corros. Sci. 2015, 98, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Lim, Y.C.; Li, Y.; Warren, C.D.; Feng, Z. Mitigation of Galvanic Corrosion in Bolted Joint of AZ31B and Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composite Using Polymer Insulation. Materials 2021, 14, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Xia, Z.; Li, Z.; Guo, F. Galvanic Corrosion Behavior of Ni—C Filled Conductive Silicone Rubber Coupled to AZ31 Magnesium Alloys. Mater. Corros. 2013, 64, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimian, S.; Bouzid, A.-H.; Hof, L.A. Corrosion Failures of Flanged Gasketed Joints: A Review. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2024, 9, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 62631-3-1; Dielectric and Resistive Properties of Solid Insulating Materials—Part 3-1: Determination of Resistive Properties (DC Methods)—Volume Resistance and Volume Resistivity—General Method. The International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Isacsson, M.; Ström, M.; Rootzén, H.; Lunder, O. Galvanically Induced Atmospheric Corrosion on Magnesium Alloys: A Designed Experiment Evaluated by Extreme Value Statistics and Conventional Techniques; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Popova, K.; Prošek, T. Corrosion Monitoring in Atmospheric Conditions: A Review. Metals 2022, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosek, T.; Le Bozec, N.; Thierry, D. Application of Automated Corrosion Sensors for Monitoring the Rate of Corrosion during Accelerated Corrosion Tests. Mater. Corros. 2014, 65, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diler, E.; Ledan, F.; LeBozec, N.; Thierry, D. Real-Time Monitoring of the Degradation of Metallic and Organic Coatings Using Electrical Resistance Sensors. Mater. Corros. 2017, 68, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, K.; Šefl, V.; Prošek, T.; Švadlena, J. Applications of a Novel Wireless System for Real-Time Atmospheric Corrosion Monitoring. Mater. Corros. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gema CorrSen. Available online: https://www.corrsen.com/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Popova, K.; Prošek, T.; Šefl, V.; Šedivý, M.; Kouřil, M.; Reiser, M. Application of Flexible Resistometric Sensors for Real-Time Corrosion Monitoring Under Insulation. Mater. Corros. 2024, 75, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosek, T.; Thierry, D.; Taxén, C.; Maixner, J. Effect of Cations on Corrosion of Zinc and Carbon Steel Covered with Chloride Deposits under Atmospheric Conditions. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 2676–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 4628:2016-8; Paints and Varnishes—Evaluation of Degradation of Coatings—Designation of Quantity Ans Size of Defects, and of Intensity of Uniform Chanes in Appearance—Part 8: Assessment of Degree of Delamination and Corrosion around a Scribe or Other Artificial Defect. ISO: Genève, Switzerland, 2016.

- Van den Steen, N.; Simillion, H.; Thierry, D.; Terryn, H.; Deconinck, J. Comparing Modeled and Experimental Accelerated Corrosion Tests on Steel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, C554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, K.; Prošek, T. Mechanism of Carbon Steel Corrosion in Accelerated Corrosion Tests. Mater. Corros. 2025, 76, 486–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, D. Automotive Corrosion and Accelerated Corrosion Tests for Zinc Coated Steels. ISIJ Int. 2018, 58, 1562–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Steen, N.; Simillion, H.; Dolgikh, O.; Terryn, H.; Deconinck, J. An Integrated Modeling Approach for Atmospheric Corrosion in Presence of a Varying Electrolyte Film. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 187, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgikh, O.; Bastos, A.; Oliveira, A.; Dan, C.; Deconinck, J. Influence of the Electrolyte Film Thickness and NaCl Concentration on the Oxygen Reduction Current on Platinum. Corros. Sci. 2016, 102, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rubber Material | Volume Resistivity [Ω·m] | Order of Magnitude [Ω·m] |

|---|---|---|

| C | 1,064,859 | 106 |

| H | 1699 | 103 |

| J | 275 | 102 |

| A | 213 | 102 |

| E | 202 | 102 |

| B | 133 | 102 |

| F | 101 | 102 |

| D | 23 | 101 |

| I | 20 | 101 |

| G | 12 | 101 |

| Rubber | EOC-R [V/SCE] | Egalv [V/SCE] | EOC-Fe [V/SCE] | jgalv [A·m−2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | −0.15 ± 0.02 | −0.48 ± 0.02 | −0.48 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.13 |

| B | −0.06 ± 0.02 | −0.52 ± 0.01 | −0.53 ± 0.01 | 1.33 ± 0.20 |

| C | 0.05 ± 0.00 | −0.49 ± 0.01 | −0.49 ± 0.01 | (2.1 ± 1.3)·10−6 |

| H | −0.22 ± 0.07 | −0.49 ± 0.01 | −0.49 ± 0.02 | 0.47 ± 0.10 |

| Rubber | EOC-R [V/SCE] | Egalv [V/SCE] | EOC-Zn [V/SCE] | jgalv [A·m−2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | −0.23 ± 0.00 | −0.97 ± 0.00 | −0.99 ± 0.00 | 768 ± 37 |

| B | −0.20 ± 0.03 | −0.98 ± 0.01 | −1.00 ± 0.00 | 537 ± 54 |

| C | 0.31 ± 0.05 | −1.00 ± 0.01 | −1.00 ± 0.01 | (5.3 ± 3.2)·10−6 |

| H | 0.05 ± 0.01 | −1.03 ± 0.01 | −1.03 ± 0.01 | 5 ± 1 |

| Sample | Average Delamination Distance [mm] | Maximum Delamination Distance [mm] |

|---|---|---|

| No rubber | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.8 |

| Rubber B | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 9.5 ± 1.7 |

| Rubber C | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.3 |

| Rubber Inert | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Popova, K.; Švadlena, J.; Prošek, T. Rubber-Induced Corrosion of Painted Automotive Steel: Inconspicuous Case of Galvanic Corrosion. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd7010002

Popova K, Švadlena J, Prošek T. Rubber-Induced Corrosion of Painted Automotive Steel: Inconspicuous Case of Galvanic Corrosion. Corrosion and Materials Degradation. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd7010002

Chicago/Turabian StylePopova, Kateryna, Jan Švadlena, and Tomáš Prošek. 2026. "Rubber-Induced Corrosion of Painted Automotive Steel: Inconspicuous Case of Galvanic Corrosion" Corrosion and Materials Degradation 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd7010002

APA StylePopova, K., Švadlena, J., & Prošek, T. (2026). Rubber-Induced Corrosion of Painted Automotive Steel: Inconspicuous Case of Galvanic Corrosion. Corrosion and Materials Degradation, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd7010002