Responses to Intermittent Light Stimulation Late in the Night Phase Before Dawn

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

- A.

- A uniform, uninterrupted light pulse delivered over 15 min.

- B.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 30 s each minute on the minute.

- C.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 15 s each minute on the minute.

- D.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 30 s every 2 min.

- E.

- A 225 s light stimulus delivered within two symmetrical 112.5 s blocks distributed at the tail-ends of ZT23 and ZT23.25. The first bookend pulse began precisely at ZT23, while the second pulse ended precisely at ZT23.25.

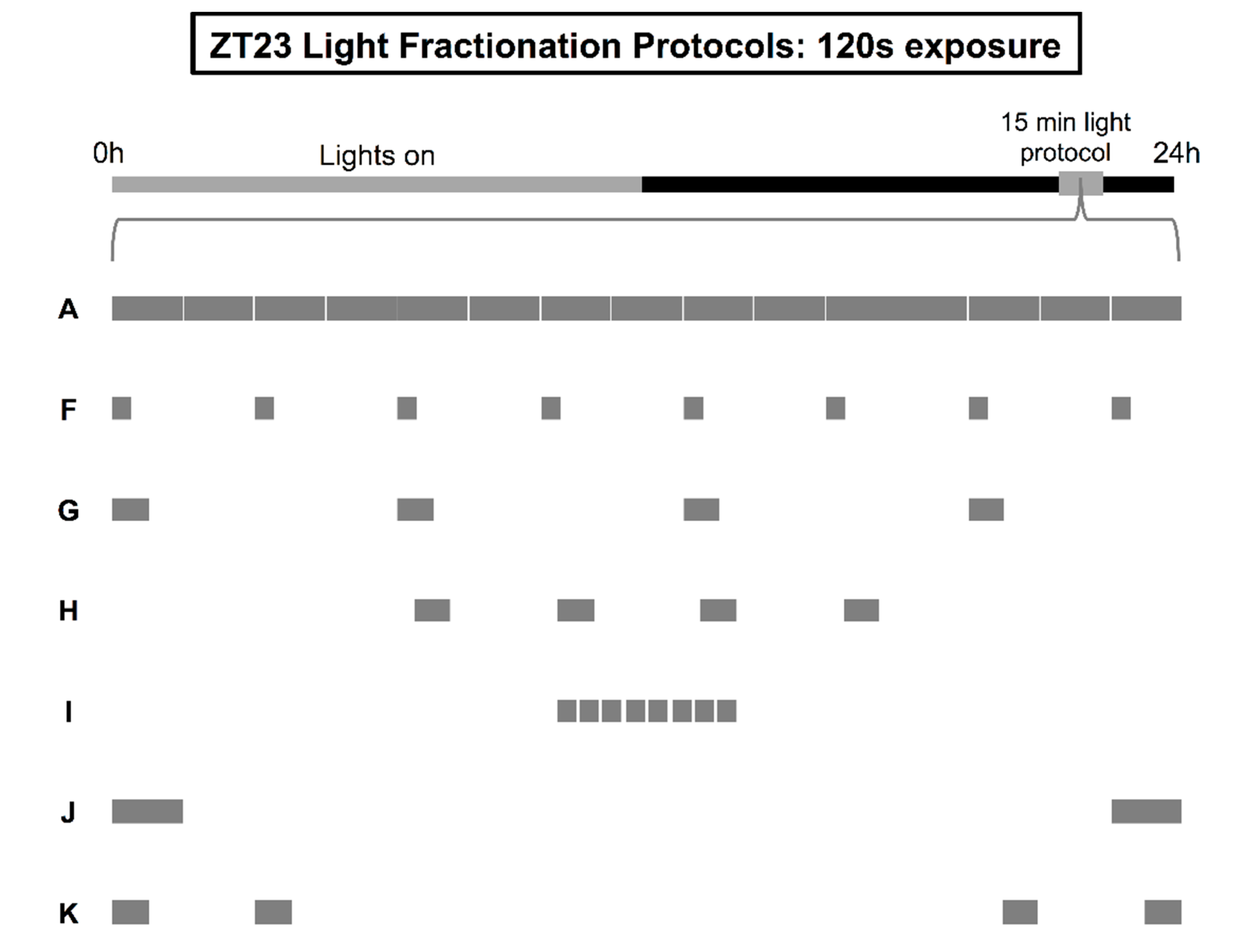

- F.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 15 s every 2 min.

- G.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 30 s every 4 min.

- H.

- A series of four 30 s light pulses separated by an interstimulus interval of 90 s (centered in the middle of the ZT23-ZT23.25 timeframe).

- I.

- A series of eight 15 s light pulses separated by an interstimulus interval of 15 s (centered in the middle of the ZT23-ZT23.25 timeframe).

- J.

- A 120 s light stimulus delivered within two symmetrical 60 s blocks distributed at the tail-ends of ZT23 and ZT23.25. The first bookend pulse began precisely at ZT23, while the second pulse ended precisely at ZT23.25.

- K.

- Two pairs of 30 s light pulses (interstimulus interval of 90 s in between individual pulses within each pair). The first pair began precisely at ZT23, while the second pair ended precisely at ZT23.25.

- L.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 15 s every 3 min.

- M.

- A series of five 15 s light pulses separated by an interstimulus interval of 15 s (centered in the middle of the ZT23-ZT23.25 timeframe).

- N.

- A series of four 19 s light pulses separated by an interstimulus interval of 57 s (centered in the middle of the ZT23-ZT23.25 timeframe).

- O.

- A series of three 25 s light pulses separated by an interstimulus interval of 75 s (centered in the middle of the ZT23-ZT23.25 timeframe).

- P.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 25 s every 5 min.

- Q.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 25 s every 6 min.

- R.

- Intermittent delivery of light for 25 s every 7 min.

- S.

- A 76 s light stimulus delivered within two symmetrical 38 s blocks distributed at the tail-ends of ZT23 and ZT23.25. The first bookend pulse began precisely at ZT23, while the second pulse ended precisely at ZT23.25.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pittendrigh, C.S.; Daan, S. A functional analysis of circadian pacemakers in nocturnal rodents. V. Pacemaker structure: A clock for all seasons. J. Comp. Physiol. 1976, 106, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyshchenko, V.P. Two-oscillatory model of the physiological mechanism of the photoperiodic reaction of insects. Zh. Obshch. Biol. 1966, 27, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Illnerová, H.; Vaněček, J. Two-oscillator structure of the pacemaker controlling the circadian rhythm of N-acetyltransferase in the rat pineal gland. J. Comp. Physiol. 1982, 145, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daan, S.; Albrecht, U.; Van der Horst, G.T.J.; Illnerová, H.; Roenneberg, T.; Wehr, T.A.; Schwartz, W.J. Assembling a clock for all seasons: Are there M and E oscillators in the genes? J. Biol. Rhythms 2001, 16, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daan, S.; Berde, C. Two coupled oscillators: Simulations of the circadian pacemaker in mammalian activity rhythms. J. Theor. Biol. 1978, 70, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daan, S.; Beersma, D.G.M.; Spoelstra, K. Dawn and dusk-specialisation of circadian system components for acceleration and deceleration in response to light. In Biological Rhythms; Honma, K., Honma, S., Eds.; Hokkaido Univ. Press: Sapporo, Japan, 2005; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg, T.; Foster, R.G. Twilight times: Light and the circadian system. Photochem. Photobiol. 1997, 66, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roenneberg, T.; Kumar, C.J.; Merrow, M. The human circadian clock entrains to sun time. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, R44–R45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehr, T.A.; Aeschbach, D.; Duncan, W.C. Evidence for a biological dawn and dusk in the human circadian timing system. J. Physiol. 2001, 535, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wehr, T.A. A ‘clock for all seasons’ in the human brain. Prog. Brain Res. 1996, 111, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wehr, T.A.; Schwartz, P.J.; Turner, E.H.; Feldman-Naim, S.; Drake, C.L.; Rosenthal, N.E. Bimodal patterns of human melatonin secretion consistent with a two-oscillator model of regulation. Neurosci. Lett. 1995, 194, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehr, T.A. In short photoperiods, human sleep is biphasic. J. Sleep Res. 1992, 1, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Helfrich-Förster, C. Does the morning and evening oscillator model fit better for flies or mice? J. Biol. Rhythms 2009, 24, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibuya, C.A.; Melnyk, R.B.; Mrosovsky, N. Simultaneous splitting of drinking and locomotor activity rhythms in a golden hamster. Naturwissenschaften 1980, 67, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, G.E.; Kahn, R.; Silver, R. Splitting of the circadian rhythm of body temperature in the golden hamster. Physiol. Behav. 1984, 32, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, G.E.; Turek, F.W. Splitting of the circadian rhythm of activity is abolished by unilateral lesions of the suprachiasmatic nuclei. Science 1982, 215, 1119–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Iglesia, H.O.; Meyer, J.; Carpino, A.; Schwartz, W.J. Antiphase oscillation of the left and right suprachiasmatic nuclei. Science 2000, 290, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, K.; Honma, S.; Katsuno, Y.; Abe, H.; Honma, K. Two distinct oscillators in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 7396–7400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Iglesia, H.O.; Cambras, T.; Schwartz, W.J.; Díez-Noguera, A. Forced desynchronization of dual circadian oscillators within the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Ogura, A.; Yamaoka, S. The clock in the dorsal suprachiasmatic nucleus runs faster than that in the ventral. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 20, 3199–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.L.; Swanson, B.E.; de la Iglesia, H.O. Circadian timing of REM sleep is coupled to an oscillator within the dorsomedial suprachiasmatic nucleus. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagota, A.; de la Iglesia, H.O.; Schwartz, W.J. Morning and evening circadian oscillations in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in vitro. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, N.; Honma, S.; Ono, D.; Tanahashi, Y.; Honma, K.I. Separate oscillating cell groups in mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus couple photoperiodically to the onset and end of daily activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7664–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Albrecht, U.; Zheng, B.; Larkin, D.; Sun, Z.S.; Lee, C.C. mPer1 and mPer2 are essential for normal resetting of the circadian clock. J. Biol. Rhythms 2001, 16, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinlechner, S.; Jacobmeier, B.; Scherbarth, F.; Dernbach, H.; Kruse, F.; Albrecht, U. Robust circadian rhythmicity of Per1 and Per2 mutant mice in constant light, and dynamics of Per1 and Per2 gene expression under long and short photoperiods. J. Biol. Rhythms 2002, 17, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoelstra, K.; Albrecht, U.; van der Horst, G.T.; Brauer, V.; Daan, S. Phase responses to light pulses in mice lacking functional per or cry genes. J. Biol. Rhythms 2004, 19, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roenneberg, T.; Morse, D. Two circadian oscillators in one cell. Nature 1993, 362, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlichting, M.; Grebler, R.; Menegazzi, P.; Helfrich-Förster, C. Twilight dominates over moonlight in adjusting Drosophila’s activity pattern. J. Biol. Rhythms 2015, 30, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoleru, D.; Peng, Y.; Agosto, J.; Rosbash, M. Coupled oscillators control morning and evening locomotor behaviour of Drosophila. Nature 2004, 431, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grima, B.; Chélot, E.; Xia, R.; Rouyer, F. Morning and evening peaks of activity rely on different clock neurons of the Drosophila brain. Nature 2004, 431, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorostiza, E.A.; Depetris-Chauvin, A.; Frenkel, L.; Pírez, N.; Ceriani, M.F. Circadian pacemaker neurons change synaptic contacts across the day. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 2161–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depetris-Chauvin, A.; Fernández-Gamba, Á.; Gorostiza, E.A.; Herrero, A.; Castaño, E.M.; Ceriani, M.F. Mmp1 processing of the PDF neuropeptide regulates circadian structural plasticity of pacemaker neurons. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehnert, K.I.; Cantera, R. Circadian rhythms in the morphology of neurons in Drosophila. Cell Tissue Res. 2011, 344, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bünning, E.; Moser, I. Response-Kurven bei der circadianen Rhythmik von Phaseolus. Planta 1966, 69, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekaran, M.K.; Engelmann, W.O. Early and late subjective night phases of the Drosophila pseudoobscura circadian rhythm require different energies of blue light for phase shifting. Z. Naturforsch C 1973, 28, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roenneberg, T.; Deng, T.S. Photobiology of the Gonyaulax circadian system. I. Different phase response curves for red and blue light. Planta 1997, 202, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaladchibachi, S.; Fernandez, F. Precision light for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Neural Plast 2018, 5868570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronfier, C.; Wright, K.P.; Kronauer, R.E.; Jewett, M.E.; Czeisler, C.A. Efficacy of a single sequence of intermittent bright light pulses for delaying circadian phase in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 287, E174–E181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rimmer, D.W.; Boivin, D.B.; Shanahan, T.L.; Kronauer, R.E.; Duffy, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A. Dynamic resetting of the human circadian pacemaker by intermittent bright light. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000, 279, R1574–R1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaladchibachi, S.; Negelspach, D.; Fernandez, F. Circadian phase-shifting by light: Beyond photons. Neurobiol. Sleep Circadian Rhythms 2018, 5, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negelspach, D.C.; Kaladchibachi, S.; Fernandez, F. The circadian activity rhythm is reset by nanowatt pulses of ultraviolet light. Proc. R Soc. B 2018, 285, 20181288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Pol, A.N.; Cao, V.; Heller, H.C. Circadian system of mice integrates brief light stimuli. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1998, 275, R654–R657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitogiannis, A.; Amir, S. Resetting the rat circadian clock by ultra-short light flashes. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 261, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, L.; Morin, L.P. Absence of normal photic integration in the circadian visual system: Response to millisecond light flashes. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 3375–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitzer, J.M.; Fisicaro, R.A.; Ruby, N.F.; Heller, H.C. Millisecond flashes of light phase delay the human circadian clock during sleep. J. Biol. Rhythms 2014, 29, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar, R.P.; Zeitzer, J.M. Temporal integration of light flashes by the human circadian system. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Joshi, D.; Chandrashekaran, M.K. Bright light flashes of 0.5 milliseconds reset the circadian clock of a microchiropteran bat. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 1984, 230, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronauer, R.E.; Forger, D.B.; Jewett, M.E. Quantifying human circadian pacemaker response to brief, extended, and repeated light stimuli over the phototopic range. J. Biol. Rhythms 1999, 14, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulburt, E.O. Explanation of the brightness and color of the sky, particularly the twilight sky. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1953, 43, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, L.; Hanna, L.; Mouland, J.; Martial, F.; West, A.; Smedley, A.R.; Bechtold, D.A.; Webb, A.R.; Lucas, R.J.; Brown, T.M. Colour as a signal for entraining the mammalian circadian clock. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurvich, L.M.; Jameson, D. The Perception of Brightness and Darkness; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, Massachusetts, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, W.K.; Mayo, E.G. The appearance of colors in twilight. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1952, 42, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, D.K.; Livingston, W. Color and Light in Nature, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, T. Fifty years of dark adaptation 1961–2011. Vis. Res. 2011, 51, 2243–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigg, E.K. The detection of atmospheric dust and temperature inversions by twilight scattering. J. Meteorol. 1956, 13, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, J.; Magnor, M.; Seidel, H.P. Physically-based simulation of twilight phenomena. ACM Trans. Graph. 2005, 24, 1353–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prabhakaran, P.M.; Sheeba, V. Sympatric Drosophilid species melanogaster and ananassae differ in temporal patterns of activity. J. Biol. Rhythms 2012, 27, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakaran, P.M.; Sheeba, V. Insights into differential activity patterns of drosophilids under semi-natural conditions. J. Exp. Biol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakaran, P.M.; Sheeba, V. Simulating natural light and temperature cycles in the laboratory reveals differential effects on activity/rest rhythm of four Drosophilids. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2014, 200, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuel, A.J.; Do, M.T.H. Melanopsin tristability for sustained and broadband phototransduction. Neuron 2015, 85, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, C.; Saccon, R.; Senthilan, P.R.; Domnik, L.; Dircksen, H.; Yoshii, T.; Helfrich-Förster, C. The circadian clock network in the brain of different Drosophila species. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013, 521, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, P.; Stanewsky, R.; Helfrich-Förster, C.; Emery-Le, M.; Hall, J.C.; Rosbash, M. Drosophila CRY is a deep brain circadian photoreceptor. Neuron 2000, 26, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, D.; Stanewsky, R.; Helfrich-Förster, C. Cryptochrome, compound eyes, Hofbauer-Buchner eyelets, and ocelli play different roles in the entrainment and masking pathway of the locomotor activity rhythm in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Rhythms 2003, 18, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayak, P.; Coupar, J.; Hughes, S.E.; Fozdar, P.; Kilby, J.; Garren, E.; Yoshii, T.; Hirsh, J. Exquisite light sensitivity of Drosophila melanogaster cryptochrome. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshii, T.; Hermann-Luibl, C.; Helfrich-Förster, C. Circadian light-input pathways in Drosophila. Commun Integr. Biol. 2016, 9, e1102805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.D.; Baik, L.S.; Holmes, T.C.; Montell, C. A rhodopsin in the brain functions in circadian photoentrainment in Drosophila. Nature 2017, 545, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kistenpfennig, C.; Grebler, R.; Ogueta, M.; Hermann-Luibl, C.; Schlichting, M.; Stanewsky, R.; Senthilan, P.R.; Helfrich-Förster, C. A new Rhodopsin influences light-dependent daily activity patterns of fruit flies. J. Biol. Rhythms 2017, 32, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grebler, R.; Kistenpfennig, C.; Rieger, D.; Bentrop, J.; Schneuwly, S.; Senthilan, P.R.; Helfrich-Förster, C. Drosophila Rhodopsin 7 can partially replace the structural role of Rhodopsin 1, but not its physiological function. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2017, 203, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschoff, J. Response curves in circadian periodicity. In Circadian Clocks; North-Holland Publishing Co.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1965; pp. 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lewy, A.J.; Sack, R.L.; Frederickson, R.H. The use of bright light in the treatment of chronobiologic sleep and mood disorders: The phase-response curve. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1983, 19, 523–525. [Google Scholar]

- Kripke, D.F.; Mullaney, D.J.; Atkinson, M.; Wolf, S. Circadian rhythm disorders in manic-depressives. Biol. Psychiatry 1978, 13, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morgenthaler, T.I.; Lee-Chiong, T.; Alessi, C.; Friedman, L.; Aurora, R.N.; Boehlecke, B.; Brown, T.; Chesson, A.L.; Kapur, V.; Maganti, R.; et al. Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Sleep 2007, 30, 1445–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terman, M.; Terman, J.S. Bright light therapy: Side effects and benefits across the symptom spectrum. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ZT23 Stimulation Protocol | Light Exposure | Behavior Onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Description | Time (s) | Δ Phase Shift, h (n) |

| A | Continuous illumination (15 min) | 900 | 2.42 ± 0.10 (92) |

| B | Intermittent pulse 30 out of every 60 s | 450 | 2.39 ± 0.13 (66) |

| C | Intermittent pulse 15 out of every 60 s | 225 | 2.19 ± 0.14 (67) |

| D | Intermittent pulse 30 out of every 120 s | 240 | 2.17 ± 0.13 (27) |

| E | Two 112.5 s light pulses spaced 11 min, 15 s apart | 225 | 2.16 ± 0.12 (61) |

| ZT23 Stimulation Protocol | Light Exposure | Behavior Onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Description | Time (s) | Δ Phase Shift, h (n) |

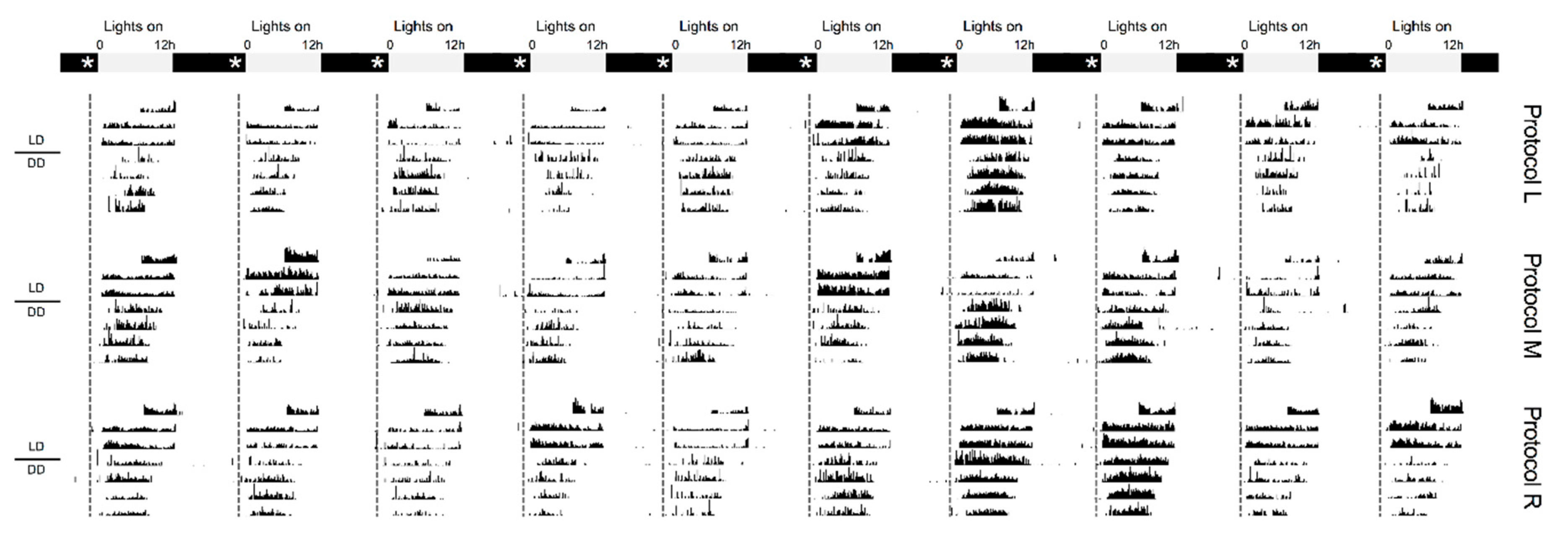

| A | Continuous illumination (15 min) | 900 | 2.42 ± 0.10 (92) |

| F | Intermittent pulse 15 out of every 120 s | 120 | 1.34 ± 0.11 (81) |

| G | Intermittent pulse 30 out of every 240 s | 120 | 1.88 ± 0.09 (99) a |

| H | Four 30 s light pulses spaced 90 s apart | 120 | 2.28 ± 0.11 (58) a,b |

| I | Eight 15 s light pulses spaced 15 s apart | 120 | 1.92 ± 0.16 (49) a,b |

| J | Two 60 s light pulses spaced 13 min apart | 120 | 1.76 ± 0.13 (55) |

| K | Paired 30 s light pulses (ISI 90 s), 10 min apart | 120 | 2.28 ± 0.12 (78) a,b |

| ZT23 Stimulation Protocol | Light Exposure | Behavior Onset | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Description | Time (s) | Δ Phase Shift, h (n) |

| A | Continuous illumination (15 min) | 900 | 2.42 ± 0.10 (92) |

| L | Intermittent pulse 15 out of every 180 s | 75 | 1.34 ± 0.09 (102) |

| M | Five 15 s light pulses spaced 15 s apart | 75 | 1.92 ± 0.11 (67) a |

| N | Four 19 s light pulses spaced 57 s apart | 76 | 1.67 ± 0.11 (67) |

| O | Three 25 s light pulses spaced 75 s apart | 75 | 1.63 ± 0.11 (86) |

| P | Intermittent 25 s pulse every 5 min | 75 | 1.36 ± 0.14 (62) |

| Q | Intermittent 25 s pulse every 6 min | 75 | 1.60 ± 0.15 (60) |

| R | Intermittent 25 s pulse every 7 min | 75 | 1.83 ± 0.09 (67) a |

| S | Two 38 s light pulses spaced 13 min, 44 s apart | 76 | 1.66 ± 0.12 (89) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaladchibachi, S.; Negelspach, D.C.; Fernandez, F. Responses to Intermittent Light Stimulation Late in the Night Phase Before Dawn. Clocks & Sleep 2019, 1, 26-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep1010004

Kaladchibachi S, Negelspach DC, Fernandez F. Responses to Intermittent Light Stimulation Late in the Night Phase Before Dawn. Clocks & Sleep. 2019; 1(1):26-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep1010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaladchibachi, Sevag, David C. Negelspach, and Fabian Fernandez. 2019. "Responses to Intermittent Light Stimulation Late in the Night Phase Before Dawn" Clocks & Sleep 1, no. 1: 26-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep1010004

APA StyleKaladchibachi, S., Negelspach, D. C., & Fernandez, F. (2019). Responses to Intermittent Light Stimulation Late in the Night Phase Before Dawn. Clocks & Sleep, 1(1), 26-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep1010004