Incidence of Daytime Sleepiness and Associated Factors in Two First Nations Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

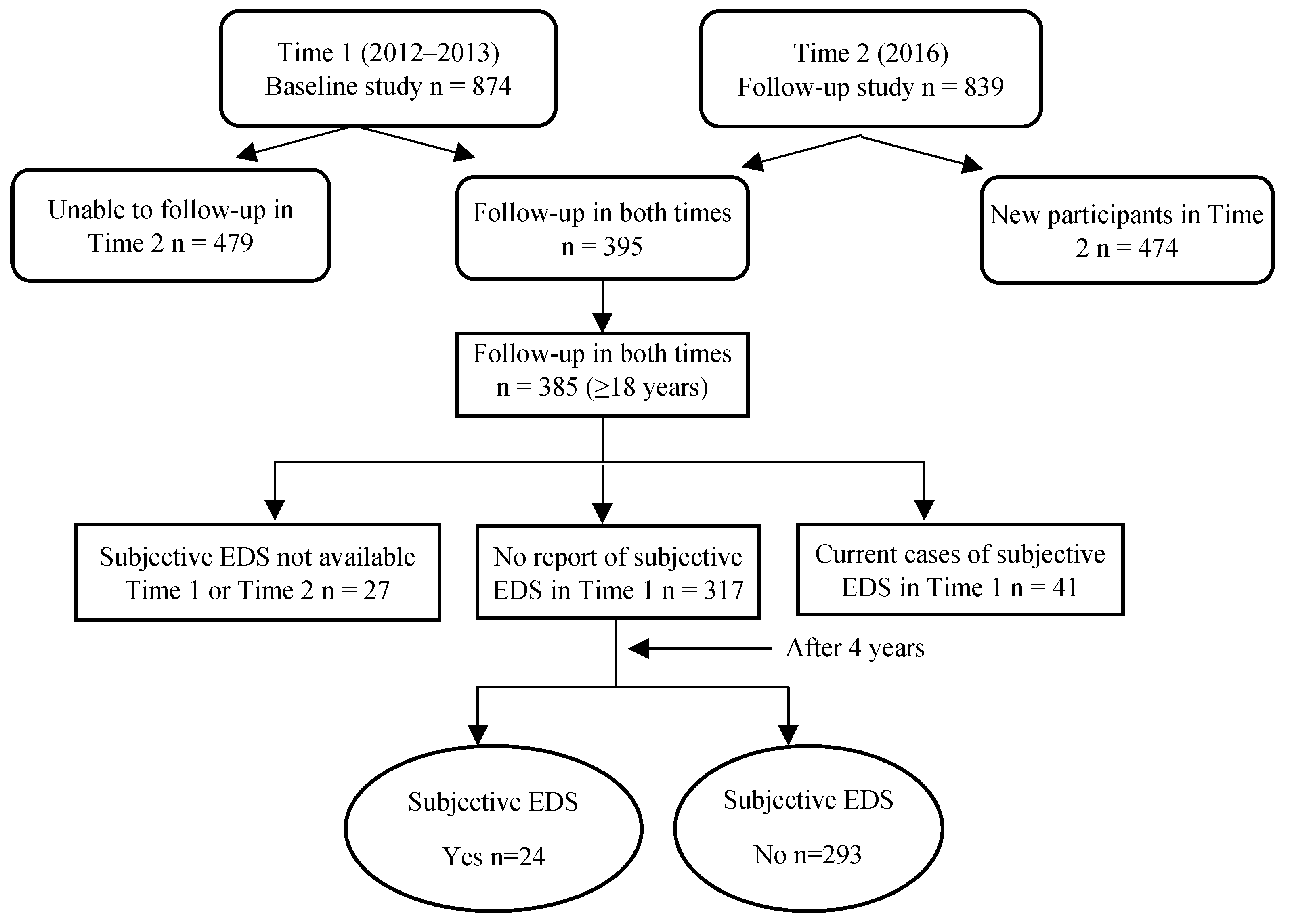

4.1. Study Sample

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EDS | Excessive daytime sleepiness |

| ESS | Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| FNLHP | First Nations Lung Health Project |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| SOB | Shortness of Breath |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| MSLT | Multiple Sleep Latency Test |

References

- National Sleep Foundation. What Is Excessive Sleepiness? Available online: https://sleepfoundation.org/excessivesleepiness/content/what-excessive-sleepiness (accessed on 26 April 2018).

- Chastens, E.R.; Olshansky, E. Daytime sleepiness, diabetes, and psychological well-being. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2008, 29, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirghani, H.O.; Elbadawi, A.S. Depression, anxiety, and daytime sleepiness among type 2 diabetic patients and their correlation with the diabetes control: A case-control study. J. Taibah Univ. Medical. Sci. 2016, 11, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.B.; Spiekerman, C.F.; Enright, P.; Lefkowitz, D.; Manolio, T.; Reynolds, C.F.; Robbins, J. Daytime sleepiness predicts mortality and cardiovascular disease in older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000, 48, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endeshaw, Y.; Rice, T.B.; Schwartz, A.V.; Stone, K.L.; Manini, T.M.; Suzanne Satterfield, S.; Cummings, S.; Harris, T.; Pahor, M.; for the Health ABC Study. Snoring, Daytime Sleepiness, and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Sleep 2013, 36, 1737–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Šiarnik, P.; Klobučníková, K.; Šurda, P.; Putala, M.; Šutovský, S.; Kollár, B.; Turčáni, P. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Association with Restless Legs Syndrome, Diabetes Mellitus, Obesity, and Sleep-Disordered Breathing. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Schröder, C.; Cajochen, C. Chronobiology, excessive daytime sleepiness and depression: Is there a link? Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guda, N.; Partington, S.; Shaw, M.J.; Leo, G.; Vakil, N. Unrecognized GERD symptoms are associated with excessive daytime sleepiness in patients undergoing sleep studies. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007, 52, 2873–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergio Garbarino, S.; Durando, P.; Guglielmi, O.; Dini, G.; Francesca Bersi, F.; Fornarino, S.; Toletone, A.; Chiorri, C.; Magnavita, N. Sleep Apnea, Sleep Debt and Daytime Sleepiness Are Independently Associated with Road Accidents. A Cross-Sectional Study on Truck Drivers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özer, C.; Etcibaşı, S.; Öztürk, L. Daytime sleepiness and sleep habits as risk factors of traffic accidents in a group of Turkish public transport drivers. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garbarino, S.; Nobili, L.; Beelke, M.; De Carli, F.; Ferrillo, F. The contributing role of sleepiness in highway vehicle accidents. Sleep 2001, 24, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, J.; Norton, R.; Ameratunga, S.; Robinson, E.; Civil, I.; Dunn, R.; Bailey, J.; Jackson, R. Driver sleepiness and risk of serious injury to car occupants: Population based case control study. BMJ 2002, 324, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefft, B.C. Prevalence of motor vehicle crashes involving drowsy drivers, United States, 1999–2008. Accid Anal. Prev. 2012, 45, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.; Amici, R.; Lucas, R.; Åkerstedt, T.; Cirignotta, F.; Horne, J.; Léger, D.; McNicholas, W.T.; Partinen, M.; Téran-Santos, J.; et al. Sleepiness at the wheel across Europe: A survey of 19 countries. J. Sleep Res. 2015, 24, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaussent, I.; Morin, C.M.; Ivers, H.; Dauvilliers, Y. Incidence, worsening and risk factors of daytime sleepiness in a population-based 5-year longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahwa, P.; Karunanayake, C.P.; Hagel, L.; Gjevre, J.A.; Rennie, D.; Lawson, J.; Dosman, J.A. Prevalence of high Epworth sleepiness scale in a rural population. Can. Respir. J. 2012, 19, e10–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjevre, J.A.; Pahwa, P.; Karunanayake, C.; Hagel, L.; Rennie, D.; Lawson, J.; Dyck, R.; Dosman, J.; Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Team. Excessive daytime sleepiness among rural residents in Saskatchewan. Can. Respir. J. 2014, 21, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Spuy, I.; Karunanayake, C.P.; Dosman, J.A.; McMullin, K.; Zhao, G.; Abonyi, S.; Rennie, D.C.; Lawson, J.; Kirychuk, S.; MacDonald, J.; et al. Determinants of excessive daytime sleepiness in two First Nation communities. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017, 17, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringhini, S.; Haba-Rubio, J.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Waeber, G.; Preisig, M.; Guessous, I.; Bovet, P.; Vollenweider, P.; Tafti, M.; Heinzer, R. Association of socioeconomic status with sleep disturbances in the Swiss population-based CoLaus study. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrin, D.C.; McGrath, J.J.; Silverstein, J.E.; Drake, C. Objective and subjective socioeconomic gradients exist for sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, weekend oversleep, and daytime sleepiness in adults. Behav. Sleep Med. 2013, 11, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendell, M.J.; Mirer, A.G.; Cheung, K.; Tong, M.; Douwes, J. Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tischer, C.; Chen, C.M.; Heinrich, J. Association between domestic mould and mould components, and asthma and allergy in children: A systematic review. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tischer, C.G.; Hohmann, C.; Thiering, E.; Herbarth, O.; Müller, A.; Henderson, J.; Granell, R.; Fantini, M.P.; Luciano, L.; Bergström, A.; et al. Meta-analysis of mould and dampness exposure on asthma and allergy in eight European birth cohorts: An ENRIECO initiative. Allergy 2011, 66, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, C.N.; Stewart-Brown, S.; Fowle, S.E. Damp housing and adult health: Results from a lifestyle study in Worcester, England. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1994, 48, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janson, C.; Norbäck, D.; Omenaas, E.; Gislason, T.; Nyström, L.; Jõgi, R.; Lindberg, E.; Gunnbjörnsdottir, M.; Norrman, E.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; et al. Insomnia is more common among subjects living in damp buildings. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tiesler, C.; Thiering, E.; Tischer, C.; Lehmann, I.; Schaaf, B.; von Berg, A.; Heinrich, J. Exposure to visible mould or dampness at home and sleep problems in children: Results from the LISAplus study. Environ. Res. 2015, 137, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, C.; Stewart, R.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; Rocha, F.P.; Fuzikawa, C.; Uchoa, E.; Firmo, J.O.A.; Castro-Costa, E. Insomnia Subtypes and Their Relationship to Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Brazilian Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Sleep 2011, 34, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kao, C.C.; Huang, C.J.; Wang, M.Y.; Tsai, P.S. Insomnia: Prevalence and its impact on excessive daytime sleepiness and psychological well-being in the adult Taiwanese population. Qual. Life Res. 2008, 17, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Model-building strategies and methods for logistic regression. In Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 89–144. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Census in Brief: The Housing Conditions of Aboriginal People in Canada; Catalogue no. 98-200-X2016021; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. Available online: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016021/98-200-x2016021-eng.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2018).

- Carrière, G.M.; Garner, R.; Sanmartin, C. Housing conditions and respiratory hospitalizations among First Nations people in Canada. Health Rep. 2017, 28, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larcombe, L.; Nickerson, P.; Singer, M.; Robson, R.; Dantouze, J.; Mckey, L.; Orr, P. Housing conditions in 2 Canadian First Nations Communities. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2011, 70, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Statistics at a Glance: 2nd Edition. Available online: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-645-x/89-645-x2015001-eng.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Statistics Canada. 2016 Census of Population, Data Tables, 2016 Census-Aboriginal Identity (9), Employment Income Statistics; Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016268; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/rt-td/ap-pa-eng.cfm (accessed on 28 June 2018).

- Talala, K.M.; Martelin, T.P.; Haukkala, A.H.; Härkänen, T.T.; Prättälä, R.S. Socio-economic differences in self-reported insomnia and stress in Finland from 1979 to 2002: A population-based repeated cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Mendoza, J.; Vgontzas, A.N. Insomnia and Its Impact on Physical and Mental Health. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2013, 15, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.J.; Appleton, S.L.; Vakulin, A.; Lang, C.; Martin, S.A.; Taylor, A.W.; McEvoy, R.D.; Antic, N.A.; Catcheside, P.G.; Wittert, G.A. Association of daytime sleepiness with obstructive sleep apnoea and comorbidities varies by sleepiness definition in a population cohort of men. Respirology 2016, 21, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chambers, E.; Pichardo, M.S.; Rosenbaum, E. Sleep and the housing and neighborhood environment of urban Latino adults living in low-income housing: The AHOME Study. Behav. Sleep Med. 2016, 14, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strøm-Tejsen, P.; Zukowska, D.; Wargocki, P.; Wyon, D.P. The effects of bedroom air quality on sleep and next-day performance. Indoor Air 2016, 26, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilsmore, B.R.; Grunstein, R.R.; Fransen, M.; Woodward, M.; Norton, R.; Ameratunga, S. Sleep habits, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness in a large and healthy community-based sample of New Zealanders. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile. 2016 Census. Beardy’s 97 and Okemasis 96, IRI [Census subdivision], Saskatchewan and Saskatchewan [Province] (Table). Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released November 29, 2017. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 29 August 2018).

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile. 2016 Census. Montreal Lake 106, IRI [Census subdivision], Saskatchewan and New Brunswick [Province] (Table). Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released November 29, 2017. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 29 August 2018).

- Aurora, R.N.; Caffo, B.; Crainiceanu, C.; Punjabi, N.M. Correlating Subjective and Objective Sleepiness: Revisiting the Association Using Survival Analysis. Sleep 2011, 34, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahwa, P.; Abonyi, S.; Karunanayake, C.; Rennie, D.C.; Janzen, B.; Kirychuk, S.; Lawson, J.A.; Katapally, T.; McMullin, K.; Seeseequasis, J.; et al. A community-based participatory research methodology to address, redress, and reassess disparities in respiratory health among First Nations. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. December 2014. Available online: http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2-2014/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2018).

- Johns, M.W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, M.W. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1992, 15, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, M.W. Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Chest 1993, 103, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, M.W. Sleepiness in different situations measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1994, 17, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, C.E.; McPherson, K.; Tikoft, E.; Usher, K.; Hosseini, F.; Ferns, J.; Jersmann, H.; Antic, R.; Maguire, G.P. Sleep Disorders in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and Residents of Regional and Remote Australia. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variables | Total n (%) | Newly Diagnosed Subjective EDS | p Value | Crude OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 151 (47.6) | 12 (50.0) | 139 (47.4) | 0.812 | 1.11 (0.48, 2.55) |

| Female | 166 (52.4) | 12 (50.0) | 154 (52.6) | 1.00 | |

| Age group | |||||

| 18–35 years | 170 (53.6) | 12 (50.0) | 158 (53.9) | 0.866 | 0.87 (0.18, 4.32) |

| 36–55 years | 122 (38.5) | 10 (41.7) | 112 (38.2) | 0.976 | 1.02 (0.20, 5.15) |

| >55 years | 25 (7.9) | 2 (8.3) | 23 (7.8) | 1.00 | |

| Education level | |||||

| Less than high school | 156 (49.4) | 14 (58.4) | 142 (48.6) | 0.425 | 1.54 (0.53, 4.41) |

| Completed high school | 77 (24.4) | 5 (20.8) | 72 (24.7) | 0.907 | 1.08 (0.30, 3.93) |

| Post-secondary (university/technical or some) | 83 (26.2) | 5 (20.8) | 78 (26.7) | 1.00 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/common law | 119 (39.0) | 8 (33.3) | 111 (39.5) | 0.550 | 0.77 (0.32, 1.83) |

| Widowed/divorced/separated/single | 186 (61.0) | 16 (66.7) | 170 (60.5) | 1.00 | |

| Body mass index | |||||

| Neither overweight nor obese | 102 (31.1) | 5 (20.8) | 97 (34.2) | 0.341 | 0.58 (0.19, 1.77) |

| Overweight | 95 (30.9) | 10 (41.7) | 85 (29.9) | 0.547 | 1.33 (0.52, 3.39) |

| Obese | 111 (36.0) | 9 (31.5) | 102 (35.9) | 1.00 | |

| Home crowding status | |||||

| More than one person per room | 99 (32.6) | 7 (31.8) | 92 (32.6) | 0.937 | 0.96 (0.39, 2.41) |

| One or less person per room | 205 (67.4) | 15 (68.2) | 190 (67.4) | 1.00 | |

| Alcohol consumption (5 or more drinks at a time) | |||||

| Never | 61 (19.3) | 4 (16.7) | 57 (19.5) | 0.675 | 0.78 (0.24, 2.51) |

| Occasionally | 122 (38.6) | 9 (37.5) | 113 (38.7) | 0.792 | 0.88 (0.35, 2.34) |

| Regularly | 133 (42.1) | 11 (45.8) | 122 (41.8) | 1.00 | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Current smoking | 265 (83.6) | 20 (83.3) | 245 (83.6) | 0.638 | 0.74 (0.20, 2.64) |

| Ex-smoker | 22 (6.9) | 1 (4.2) | 21 (7.2) | 0.482 | 0.43 (0.04, 4.53) |

| Never smoker | 30 (9.5) | 3 (12.5) | 27 (9.2) | 1.00 | |

| Employment Status | |||||

| Employed (full-time/part-time/seasonally/self-employment) | 73 (23.1) | 3 (12.5) | 70 (24.0) | 0.182 | 0.42 (0.12, 1.49) |

| Student (part-time/full-time) | 24 (7.6) | 1 (4.2) | 23 (7.9) | 0.422 | 0.43 (0.05, 3.37) |

| Unemployed | 219 (69.3) | 20 (83.3) | 199 (68.1) | 1.00 | |

| Co-morbid conditions | |||||

| Shortness of breath | |||||

| Yes | 156 (49.2) | 13 (54.2) | 143 (48.8) | 0.607 | 1.24 (0.54, 2.83) |

| No | 161 (50.8) | 11 (45.8) | 150 (51.2) | 1.00 | |

| Loud snoring | |||||

| Yes | 51 (16.1) | 3 (12.5) | 48 (16.4) | 0.163 | 0.73 (0.21, 2.55) |

| No | 265 (83.9) | 21 (87.5) | 244 (75.4) | 1.00 | |

| Ever Dr. said | |||||

| Chronic lung diseases * | |||||

| Yes | 81 (25.6) | 9 (37.5) | 72 (24.8) | 0.163 | 1.84 (0.78, 4.35) |

| No | 236 (74.4) | 15 (62.2) | 221 (75.2) | 1.00 | |

| Sinus trouble | |||||

| Yes | 85 (30.8) | 7 (31.8) | 78 (30.7) | 0.908 | 1.05 (0.43, 2.58) |

| No | 191 (69.2) | 15 (68.2) | 176 (69.3) | 1.00 | |

| Heart problem | |||||

| Yes | 25 (8.1) | 1 (4.2) | 24 (8.5) | 0.456 | 0.47 (0.07, 3.39) |

| No | 283 (91.9) | 23 (95.8) | 260 (91.5) | 1.00 | |

| Tuberculosis | |||||

| Yes | 24 (8.9) | 1 (4.5) | 23 (9.3) | 0.469 | 0.47 (0.06, 3.65) |

| No | 246 (91.1) | 21 (95.5) | 225 (90.7) | 1.00 | |

| Attack of bronchitis | |||||

| Yes | 81 (29.9) | 5 (22.7) | 76 (30.5) | 0.444 | 0.67 (0.24, 1.86) |

| No | 190 (70.1) | 17 (77.3) | 173 (69.5) | 1.00 | |

| Asthma | |||||

| Yes | 47 (14.8) | 4 (16.7) | 43 (14.7) | 0.794 | 1.16 (0.38, 3.57) |

| No | 270 (85.2) | 20 (83.3) | 250 (85.3) | 1.00 | |

| Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 42 (13.8) | 5 (20.8) | 37 (13.2) | 0.310 | 1.74 (0.60, 5.04) |

| No | 263 (86.2) | 19 (79.2) | 244 (86.8) | 1.00 | |

| Depression | |||||

| Yes | 61 (19.9) | 7 (29.2) | 54 (19.1) | 0.238 | 1.75 (0.69, 4.42) |

| No | 246 (80.1) | 17 (70.8) | 229 (80.9) | 1.00 | |

| Ear infection | |||||

| Yes | 44 (14.1) | 4 (16.7) | 40 (13.9) | 0.716 | 1.24 (0.39, 3.88) |

| No | 268 (85.9) | 20 (83.3) | 248 (86.1) | 1.00 | |

| Heart burn/Stomach Reflex | |||||

| Yes | 50 (16.0) | 5 (21.7) | 45 (15.5) | 0.440 | 1.51 (0.53, 4.31) |

| No | 263 (84.0) | 18 (78.3) | 253 (84.5) | 1.00 | |

| Socio-economic factors | |||||

| Money left over at the end of month | |||||

| Not enough money | 156 (51.7) | 17 (77.3) | 139 (49.6) | 0.072 | 3.09 (0.91, 10.57) |

| Just enough money | 67 (22.2) | 2 (9.1) | 65 (23.2) | 0.784 | 0.78 (0.13, 4.60) |

| Some money | 79 (26.1) | 3 (13.6) | 76 (27.1) | 1.00 | |

| Housing conditions | |||||

| House in need of repairs | |||||

| Yes (major repair) | 123 (41.4) | 10 (45.5) | 113 (41.1) | 0.086 | 3.86 (0.83, 18.04) |

| Yes (minor repair) | 85 (28.6) | 10 (45.5) | 75 (27.3) | 0.026 | 5.82 (1.23, 27.52) |

| No (only regular maintenance) | 89 (30.0) | 2 (9.1) | 87 (31.6) | 1.00 | |

| In past 12 months, water or dampness in home | |||||

| Yes | 182 (63.4) | 18 (85.7) | 164 (61.7) | 0.035 | 3.73 (1.10, 12.66) |

| No | 106 (36.6) | 3 (14.3) | 102 (38.3) | 1.00 | |

| Damage caused by dampness | |||||

| Yes | 153 (48.3) | 16 (66.7) | 137 (46.8) | 0.061 | 2.28 (0.96, 5.39) |

| No | 164 (51.7) | 8 (33.3) | 156 (53.2) | 1.00 | |

| Mildew/moldy odor or musty smell | |||||

| Yes | 153 (53.9) | 16 (72.7) | 137 (52.3) | 0.075 | 2.43 (0.91, 6.46) |

| No | 131 (46.1) | 6 (27.3) | 125 (47.7) | 1.00 | |

| Signs of mold or mildew in home | |||||

| Yes | 133 (48.0) | 12 (57.1) | 121 (47.3) | 0.385 | 1.49 (0.61, 3.66) |

| No | 144 (52.0) | 9 (42.9) | 135 (52.7) | 1.00 | |

| Model 1 † | Model 2 † | Model 3 † | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Socio-economic factors | ||||||

| Money left over at the end of month | ||||||

| Not enough money | 3.83 (1.02, 14.43) | 0.047 | 4.62 (1.11, 19.32) | 0.036 | 3.32 (0.93, 11.79) | 0.064 |

| Just enough money | 0.85 (0.13, 5.63) | 0.873 | 1.08 (0.16, 7.43) | 0.937 | 0.69 (0.12, 4.12) | 0.684 |

| Some money | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Housing conditions | ||||||

| House in need of repairs | ||||||

| Yes (major repair) | 4.47 (0.86, 23.14) | 0.074 | ||||

| Yes (minor repair) | 5.72 (1.10, 29.73) | 0.038 | ||||

| No (only regular maintenance) | 1.00 | |||||

| In past 12 months, water or dampness in home | ||||||

| Yes | 3.54 (1.02, 12.22) | 0.046 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Damage caused by dampness | ||||||

| Yes | 2.79 (1.02, 7.65) | 0.046 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karunanayake, C.P.; Dosman, J.A.; Rennie, D.C.; Lawson, J.A.; Kirychuk, S.; Fenton, M.; Ramsden, V.R.; Seeseequasis, J.; Abonyi, S.; Pahwa, P.; et al. Incidence of Daytime Sleepiness and Associated Factors in Two First Nations Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada. Clocks & Sleep 2019, 1, 13-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep1010003

Karunanayake CP, Dosman JA, Rennie DC, Lawson JA, Kirychuk S, Fenton M, Ramsden VR, Seeseequasis J, Abonyi S, Pahwa P, et al. Incidence of Daytime Sleepiness and Associated Factors in Two First Nations Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada. Clocks & Sleep. 2019; 1(1):13-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep1010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarunanayake, Chandima P., James A. Dosman, Donna C. Rennie, Joshua A. Lawson, Shelley Kirychuk, Mark Fenton, Vivian R. Ramsden, Jeremy Seeseequasis, Sylvia Abonyi, Punam Pahwa, and et al. 2019. "Incidence of Daytime Sleepiness and Associated Factors in Two First Nations Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada" Clocks & Sleep 1, no. 1: 13-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep1010003