1. Introduction

Nanotechnology has revolutionized materials science by enabling the design of functional nanomaterials with properties superior to their bulk counterparts, owing to their high surface-to-volume ratios and quantum size effects. Among these, nanocomposites often exhibit synergistic behaviors, such as enhanced catalytic, optical, and electrochemical performance compared to monometallic systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Their tailored architecture and multifunctionality make them highly appropriate for applications in antioxidant, anticorrosive, and catalytic treatments.

However, conventional nanocomposite synthesis usually depends on toxic chemicals and energy intensive methods, which compromise both sustainability and environmental safety. The introduction of green synthesis methodologies, employing plant extracts and other biological sources as natural stabilizing and capping agents, addresses these drawbacks by providing cost-effective, eco-friendly alternatives that minimize harmful and toxic byproducts. Such approaches exploit the rich phytochemical composition of plants, including phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids, to mediate nanoparticle formation under mild, environmentally benign conditions [

5,

6,

7].

Trachyspermum ammi (ajwain) seeds, widely used in traditional medicine, are particularly effective green catalytic agents. They are rich in bioactive phytochemicals such as thymol, p-cymene, and γ-terpinene, which act as powerful natural reducing and stabilizing agents during nanoparticle synthesis. While the therapeutic and antimicrobial potential of

T. ammi seed oil has been extensively documented [

8,

9], its application as a green reducing, capping, and inhibition agent for the synthesis of mixed oxide nanocomposites (NCs) remains largely unexplored.

In this study, T. ammi seed extract was utilized to synthesize Cd–Cs mixed oxide NCs through an eco-friendly, plant-mediated route and to investigate, for the first time, their synergistic antioxidant and corrosion-inhibition performance on mild steel. This dual-functional and electrocatalytically driven approach provides a novel, promising strategy for developing multifunctional nanomaterials with enhanced surface-protective properties. Notably, plant-derived molecules with strong antioxidant capacity (e.g., phenolics and flavonoids) can also act as corrosion inhibitors by adsorbing onto metal surfaces and forming adsorbed protective films. Integrating these electrocatalytic and antioxidant functions within NCs thus offers an efficient route toward simultaneous corrosion resistance.

As part of our ongoing research on nanoparticle synthesis via green methodologies [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], we have explored plant extracts as green alternatives to traditional chemical methods. In the present work, Cd–Cs mixed oxide nanocomposites were synthesized, which is a novel and underexplored field. During synthesis, Cs

+ ions derived from the metal precursor can either form a Cs–O surface species or integrate into the nanoparticle lattice. The presence of Cs

+ modulates surface charge, facilitates adsorption of ions, and enhances barrier protection against dissolution.

The synergistic interaction between CdO and Cs

+ species strengthens antioxidant activity and improves electrochemical corrosion inhibition efficiency, highlighting the electrocatalytic dimension of the system. By harnessing the intrinsic capping and stabilizing potential of

T. ammi seed extract, this green synthetic route addresses the limitations of conventional toxic methods while using systematic control of physicochemical characteristics through variations in precursor ratio, pH, temperature, and reaction time. Comparable eco-friendly systems with their potential efficacy are shown in

Table 1, further underscoring the importance of plant-mediated synthesis of nanocomposites for multifunctional electrocatalytic and corrosion protective applications. These findings highlight the advantages of the present Cd–Cs nanocomposites study, including high inhibition efficiency, lower IC

50 values, and being the first plant-mediated Cd–Cs oxide system.

In summary, this study integrates a green synthetic strategy with functional material design to develop electrocatalytically active Cd–Cs mixed oxide NCs using T. ammi seed extract. The resulting NCs were thoroughly characterized and shown to exhibit dual functionality serving both as efficient antioxidants and as potent corrosion inhibitors for mild steel. The radical scavenging and protective performance arise from the synergistic interaction between CdO and Cs+ surface species, which is further supported by the bioactive phytochemicals of the plant extract. This work represents a green and innovative approach to nanomaterial design and aligns with the emerging demand for environmentally responsible nanotechnology with practical uses in surface engineering and materials protection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Extract Preparation

Seeds of T. ammi were first rinsed with tap water and then repeatedly washed with distilled water to remove surface impurities and dust. Approximately 50 g of the cleaned seeds were boiled in 500 mL of distilled water (solid-to-liquid ratio 1:10) at 100 °C for 45 min to ensure maximum extraction of phytochemicals. The resulting mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the clear aqueous extract was stored at room temperature for subsequent use as a natural reducing and stabilizing agent in nanocomposite synthesis.

2.2. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry of Plant Extract

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) is an analytical technique that separates compounds in a mixture by gas chromatography and subsequently identifies and quantifies them based on their mass spectra. It is widely employed for detecting, characterizing and analyzing the chemical composition of plant extracts.

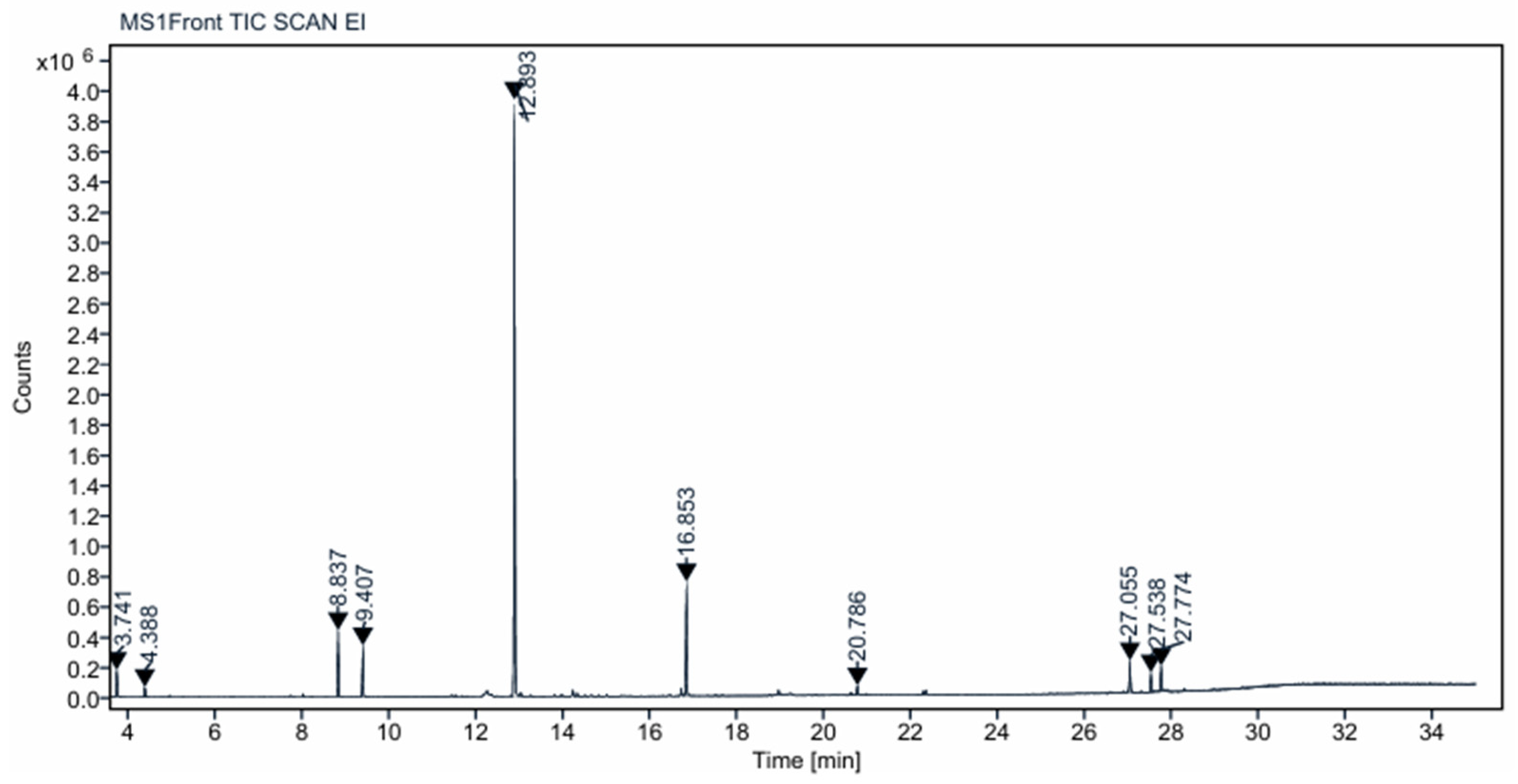

The GC–MS spectrum of the

T. ammi seed extract (

Figure 1) revealed a complex mixture of bioactive constituents, including terpenes (such as

o-cymene, γ-terpinene, and 3-carene), phenolic compounds (thymol and substituted phenols), esters, and fatty acid amides [

9]. The dominant peak at 12.89 min corresponded to thymol and related phenolics, which are well known for their antioxidant and anticorrosive properties. The presence of terpenes and fatty acid amides further enhances the extract’s potential as a green corrosion inhibitor, as these compounds can adsorb onto the steel surface, forming a protective barrier that mitigates acid attack [

21,

22]. The identified components are summarized in

Table 2.

Prior to GC–MS analysis, the aqueous extract was subjected to liquid–liquid extraction with ethyl acetate (3×). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was injected for GC–MS analysis.

2.3. Standard Measurement and Repetition Procedure

All experiments in this study, including DLS, zeta potential, ABTS, and DPPH antioxidant assays and electrochemical corrosion measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3). For each analysis, freshly prepared samples were used for every run. Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For instrumental measurements (DLS, zeta potential, and electrochemical tests), any run showing non-physical fluctuations, scattering artefacts, or unstable signals was repeated and such outliers were excluded.

2.4. Instrument/Material Used

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade, and 0.5 M HCl was prepared using deionized water. Cd–Cs nanocomposites were synthesized as described in

Section 2.1 and used at five concentrations (blank, 200, 400, 600, and 800 mg/L); equivalent values have been corrected and expressed as mg L

−1 throughout the manuscript). Electrochemical experiments were performed using a NOVA potentiostat/galvanostatic (Metrohm Auto lab B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands) sourced from Utrecht, Netherlands equipped with a conventional three-electrode cell consisting of a mild steel working electrode (IS 2062 grade, 1 cm

2 exposed area) sourced from Gobingarh, India, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as reference, and a platinum wire (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as the counter electrode. The working electrode was mounted in epoxy resin and polished before each test.

3. Synthesis

For the synthesis of Cd–Cs mixed oxide nanocomposites (

Figure 2), 50 mL of

T. ammi seed extract was added dropwise to 50 mL of an aqueous solution containing 0.1 M Cd(NO

3)

2·4H

2O and 0.1 M CsCl under continuous magnetic stirring at 60 °C. Cadmium nitrate tetrahydrate and cesium chloride served as the respective cadmium and cesium precursors, mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio to achieve the desired Cd:Cs composition in the final nanocomposite. The total ionic strength of the reaction mixture was maintained at approximately 0.05 M, accounting for all dissociated ionic species (Cd

2+, NO

3−, Cs

+, Cl

−).

The pH of the precursor solution was adjusted to 9 using 0.1 M NaOH, as mildly alkaline conditions favor the formation of Cd(OH)2, which upon drying is converted to CdO. The reaction mixture was stirred constantly for 120 h to ensure complete nucleation of NCs. After synthesis, the resulting suspension was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 min to separate the NCs, which were then washed repeatedly with ethanol and acetone to remove leftover impurities. The purified product was then dried at 70 °C for 4–5 h and processed into a fine powder for subsequent characterization.

All material characterization and performance examinations (corrosion inhibition and antioxidant assays) were performed on the batch synthesized under optimized conditions (0.05 M total precursor concentration, pH 9, 60 °C, 120 h), as shown in

Section 4.

4. Optimization of Synthesis Parameters

In the green synthesis of NCs using plant material, optimizing reaction conditions is crucial to achieving controlled particle size, morphology, and functionality. CdO nanoparticles usually exhibit a characteristic UV–Vis absorption band in the 270–290 nm region, whereas the Cd–Cs NCs display a broader absorption band between 320 and 350 nm. This red shift highlights modifications in electronic transitions and suggests that Cs incorporation promotes nucleation and surface modification, which was not previously reported.

In this study, the key synthesis parameters were optimized that include metal precursor concentration, plant extract ratio, pH, reaction temperature, and time to understand their influence on NCs formation and structural evolution. The observed outcomes provide insight into particle size, surface chemistry, and electrocatalytic functionality of the biosynthesized Cd-Cs NCs.

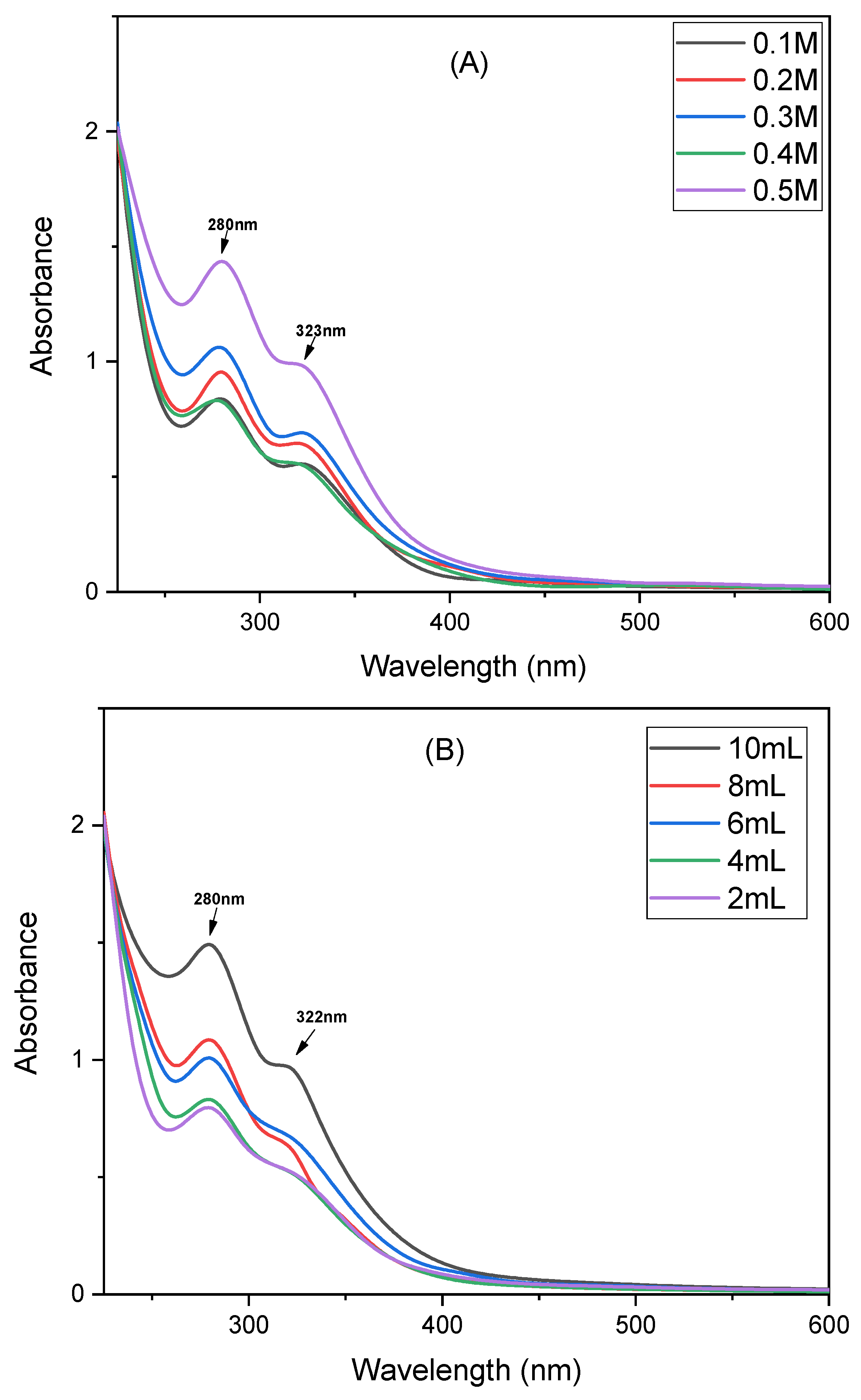

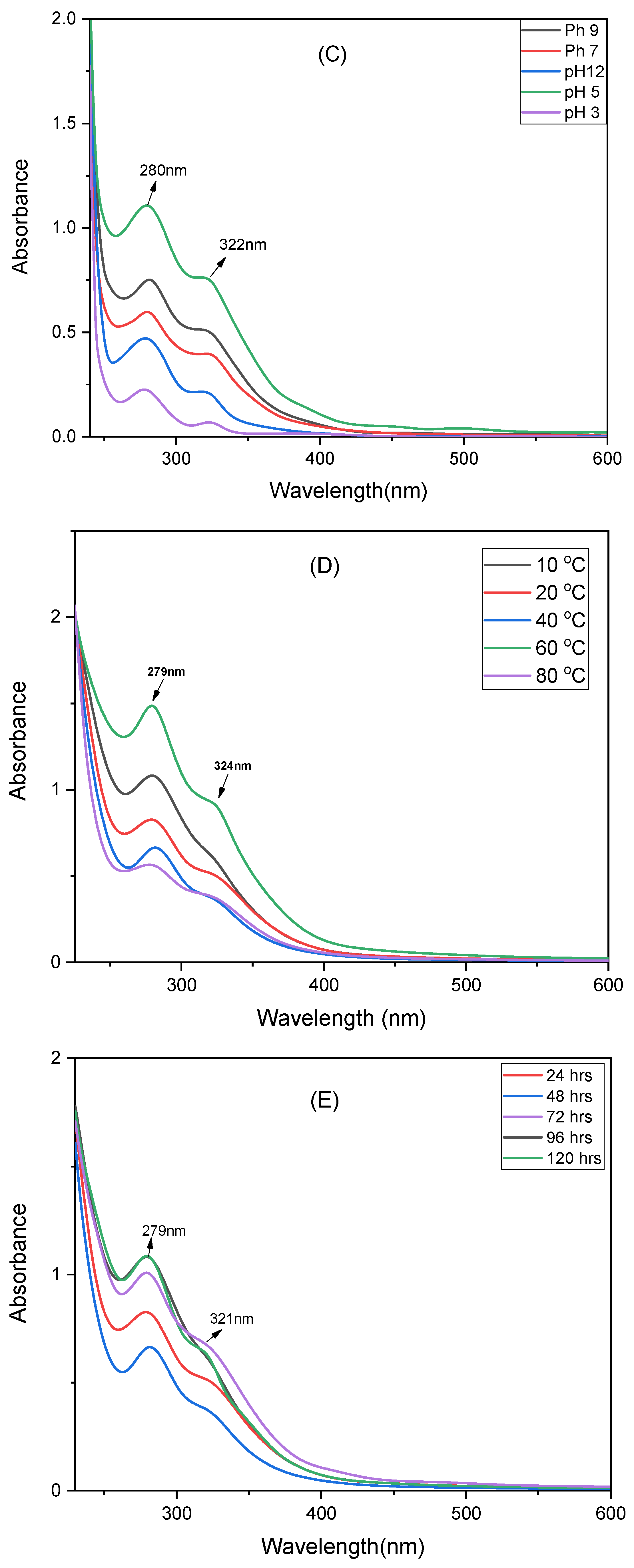

4.1. Effect of Metal Precursor

The concentration of metal precursors, which are cadmium nitrate and cesium chloride, plays a key role in enhancing the nucleation and growth of NCs. In this study, precursor concentrations varying from 0.1 M to 0.5 M were accessed. The UV–Vis spectrum (

Figure 3A) suggests that a 0.5 M precursor concentration shows the highest absorbance intensity, indicating effective nucleation and high yield of Cd–Cs nanocomposites. At lower concentrations, the reduced absorbance suggests incomplete reduction and limited particle formation due to insufficient availability of metal ions. Therefore, 0.5 M was identified as the optimal metal precursor concentration for stable and well-formed Cd–Cs nanocomposites.

4.2. Effect of Plant Extract

The phytochemicals in T. ammi seed extract play an essential role as natural stabilizing and capping agents in the formation of Cd–Cs NCs. The extract was prepared using a solid to liquid ratio of 1:10. After boiling and cooling, mixture was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper (11 µm pore size) to remove insoluble material. Different extract volumes varying from 2 mL to 10 mL were accessed to evaluate their impact on the formation of nanocomposites.

As observed in

Figure 3B, the absorbance value increased with extract volume, reaching an optimum value at 10 mL. This result indicates that higher extract volumes provide an enough concentration of phytochemicals to reduce and stabilize Cd

2+ and Cs

+ ions effectively. Similarly, lower extract volumes lead to weaker absorbance peaks that indicate incomplete reduction and limited NCs formation. Therefore, 10 mL of extract was selected as the optimal volume for Cd–Cs nanocomposites.

4.3. Effect of pH

The pH of the reaction directly influences the particle size, stability, and dispersion of NCs. Experiments performed in a pH range of 3 to 12 indicated that both highly acidic (pH 3) and strongly alkaline (pH 9–12) resulted in lower absorbance caused by NCs aggregation (

Figure 3C). The maximum absorbance observed at pH 5 suggests that lower acidic medium favors effective formation of stable and well-dispersed NCs. These outcomes aligned with previous literature that shows the mild acidic conditions enhance plant-mediated NCs synthesis.

4.4. Effect of Temperature

Temperature helps in affecting the kinetics of NCs formation. Reactions examined at 10, 20, 40, 60, and 80 °C showed a significant increase in UV–Vis absorbance with increasing temperature, reaching an optimum at 60 °C (

Figure 3D). This observation highlights that moderate heating promotes reduction kinetics and enhances effective nucleation of the NCs. At 80 °C, the absorbance reduced due to degradation of phytochemicals at high temperature and also increased particle aggregation. Therefore, 60 °C was selected as the optimal temperature for well-formed and stable Cd–Cs nanocomposites.

4.5. Effect of Reaction Time

The duration of reaction plays a vital role in determining the extent of metal ion reduction and stabilization of NCs. Monitoring the reaction for over 24 to 120 h indicates that a gradual increase in UV–Vis absorbance with increasing time, reaching a maximum at 120 h (

Figure 3E). This observation shows that prolonged reaction time facilitates complete reduction of metal ions and efficient capping of NCs by plant sourced metabolites. Shorter reaction times gives in incomplete formation of NCs and lower absorbance. Consequently, 120 h was established as the optimal reaction time for synthesizing stable and well-formed Cd–Cs nanocomposites.

5. Characterization

Prior to practical applications, the successful synthesis of Cd–Cs mixed oxide NCs must be confirmed by a range of analytical techniques. A preliminary indication of NCs formation is the visual change in color of the reaction mixture from brown to greenish-black. This transformation is further validated by UV–Visible spectroscopy (Shimadzu UV-1900, SHIMADZU, Nishinokyo Kuwabara-cho, Nakagyo-ku, Japan), which depicts the characteristic absorption peaks of the synthesized nanomaterial.

Fourier–transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (PerkinElmer FTIR) sourced from CMC HSR, Bangalore, India is employed to identify the functional groups and biomolecules involved in the synthesis and stabilization of the nanoparticles. X-ray diffraction (X’PERT PRO) provides insight into the crystallinity and phase formation, while scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (HITACHI SU8010 SERIES, HITACHI, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan) yields complete information on surface configuration and elemental composition. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy with EDS (CRYO ARM™ 300 II, JEOL, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) gives high resolution imaging of particle morphology and distribution. The specific surface area and porosity are demonstrated using BET analysis and colloidal stability along with particle size is evaluated by zeta potential and dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements (Zetasizer, Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK).

Collectively, these complementary characterization techniques confirm the successful formation, structural integrity, and stability of the biosynthesized Cd–Cs mixed oxide nanocomposites.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. UV-Visible Spectroscopy

UV–Visible spectroscopy of the synthesized Cd–Cs mixed oxide nanocomposites (

Figure 4) revealed two characteristic absorption peaks at approximately 280 nm and 324 nm, which are absent in the spectrum of the

T. ammi seed extract. This confirms that these spectral features originate from the newly formed nanostructures rather than from extract components. The observed bands are attributed to electronic transitions within the nanocomposite. Similar multiple absorption peaks have been reported in biologically synthesized CdS nanoparticles by Bhadwal et al. [

23]. Therefore, the UV–Vis spectra provide strong evidence for the successful formation of Cd–Cs nanocomposite structures and corroborate their successful synthesis.

6.2. FTIR

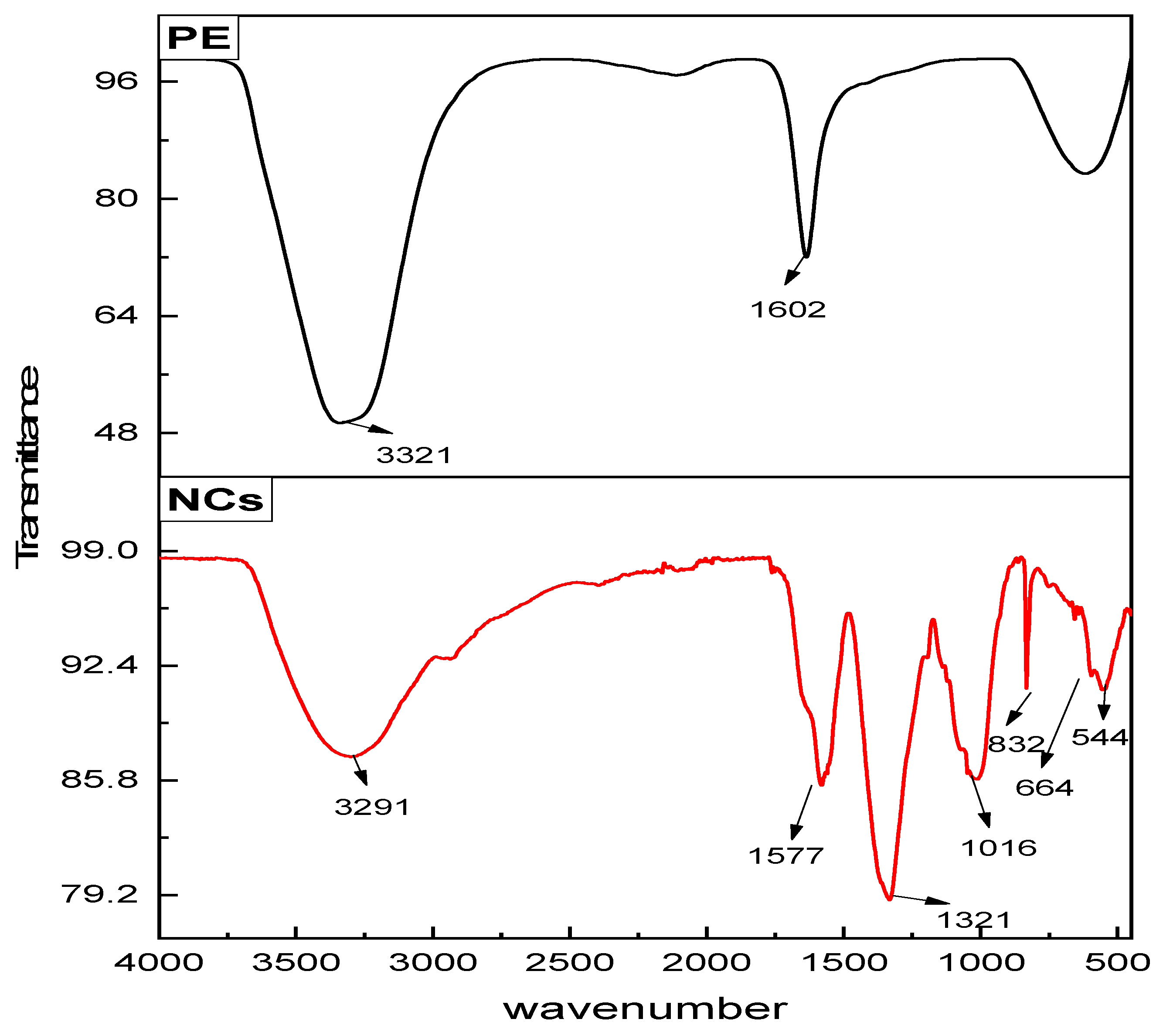

The FTIR spectra of the

T. ammi seed extract and the Cd–Cs nanocomposites (

Figure 5) exhibit notable differences in functional group vibrations. In the extract spectrum, a broad band at 3412 cm

−1 corresponds to O–H stretching of hydroxyl groups from phenolics and flavonoids. Peaks at 2924 cm

−1 and 1383 cm

−1 are attributed to aliphatic C–H stretching, while a strong band near 1634 cm

−1 indicates C = O stretching of amides. The band at 1060 cm

−1 corresponds to C–O stretching vibrations of alcohols, ethers, or polysaccharides.

In contrast, the nanocomposite spectrum shows a broad O–H stretching band at 3405 cm

−1, slightly shifted relative to the extract, suggesting hydrogen-bonding interactions with the nanoparticle surface. The carbonyl band shifts to 1630 cm

−1, and the C–O vibration appears at 1045 cm

−1, indicating coordination of phytochemicals with metal ions during nanoparticle capping and stabilization. Notably, new absorption features appear in the low-frequency region: a distinct band at 664 cm

−1 is assigned to Cd–O stretching, while peaks below 600 cm

−1 correspond to Cs–O vibrations or Cs

+ surface species. These low-wavenumber bands confirm the formation of metal–oxygen bonds and support the successful incorporation of cesium into the CdO matrix [

24].

6.3. XRD

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the synthesized Cd–Cs nanocomposites is presented in

Figure 6. The sharp and intense diffraction peaks confirm the crystalline nature of the material. Major peaks observed at 2θ values of approximately 23.5°, 28.4°, 33.0°, 37.1°, 40.5°, 46.8°, 52.3°, and 56.2° were successfully indexed to the CdO and Cs

2O phases. Similar crystalline characteristics for CdO and Cs-containing oxide phases have been reported in green-synthesized metal oxide nanocomposites by Silva et al. [

25] (JCPDS 05-0640; JCPDS 19-0336).

Reflections corresponding to the (111), (311), (222), and (331) planes were attributed to CdO, while additional peaks at (200) and (211) are consistent with Cs-containing surface species. In the absence of XPS or Rietveld refinement, these assignments are made cautiously. The coexistence of both phases in the XRD pattern provides strong evidence for the successful formation of the Cd–Cs nanocomposite. The average crystallite size was calculated to be approximately 22 nm using the Scherrer equation with K = 0.9. Each 2θ value represents the mean of three independent measurements, and corresponding d-spacing values were calculated from Bragg’s law and reported to three significant figures [

26].

6.4. SEM-EDS

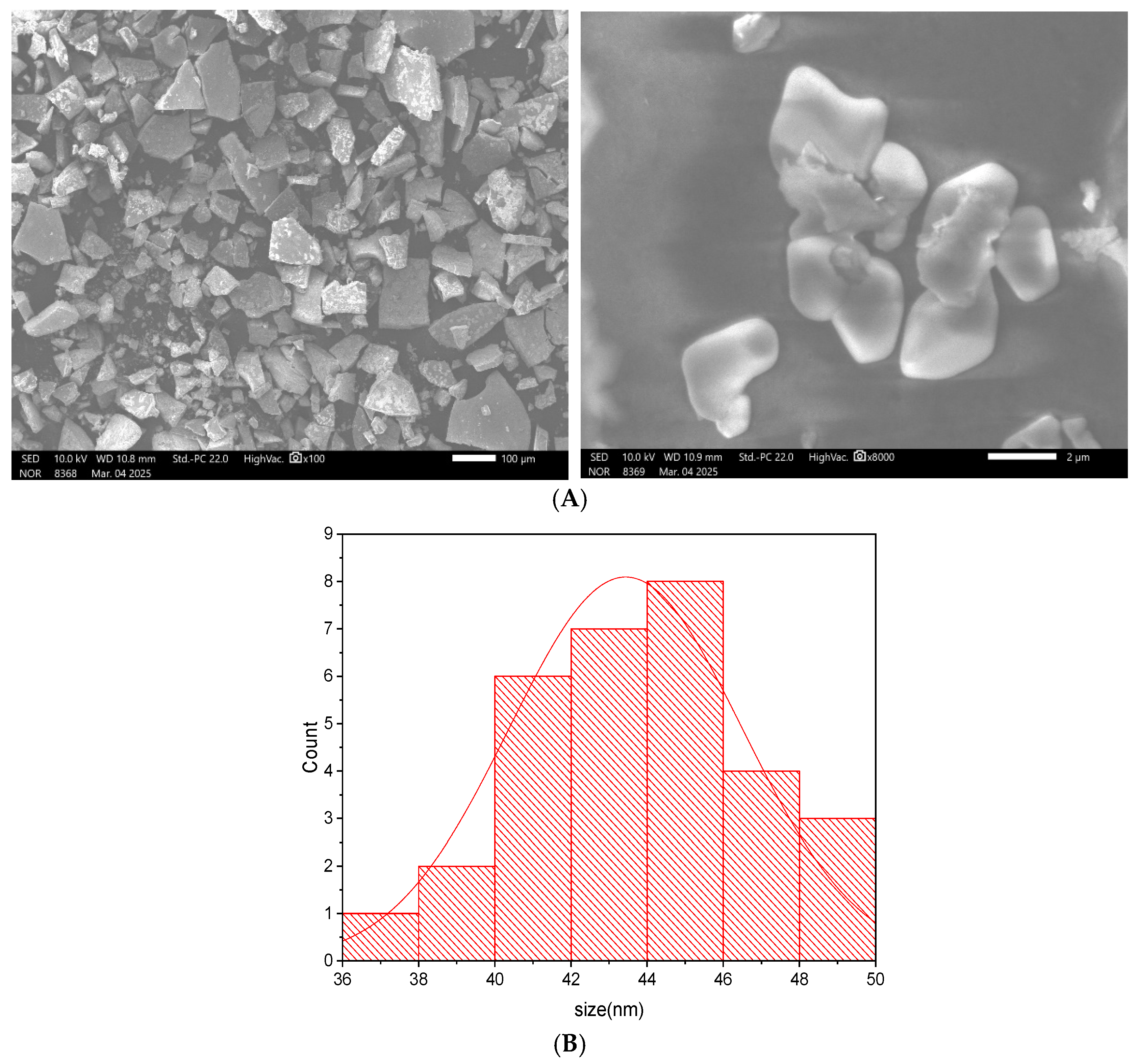

The surface morphology of the synthesized Cd–Cs nanocomposites was investigated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) as shown in

Figure 7A. The micrographs reveal a heterogeneous distribution of micro- to submicron-sized particles with irregular, polyhedral shapes. The particles exhibit relatively smooth surfaces and well-defined edges, indicative of crystalline formation. Some degree of agglomeration is observed, likely due to interparticle interactions, which is common in green synthesis methods.

The relatively dense and faceted morphology suggests the formation of compact microstructures, which can function effectively as protective barriers by limiting the deposition of corrosive species such as oxygen, moisture and chloride ions on metal surfaces [

27]. Particle sizes were estimated to range between approximately 40–50 nm, distribution shown in

Figure 7B. Elemental composition, determined by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), confirmed the presence of cadmium, cesium, and oxygen with the corresponding spectrum shown in

Figure S1 and detailed compositional data provided in

Table 3.

Additionally, during preliminary optimization, various synthesis conditions were qualitatively examined. The ratio of plant extract played a key role in NCs synthesis, low concentration of extract gives irregular structures and elemental composition trend results in stronger C/O signals while higher amount often improved NCs dispersion and decreased agglomeration because of abundant phytochemical capping agents (Ahmed et al. in 2016) [

28]. The metal precursor concentration also influenced nucleation and uniformity of mixed oxide formation. Reaction temperature has a strong effect on particle formation where mild temperature facilitates uniform structures while high temperatures produce partial agglomeration and composition shows enhanced oxidation (Khalil et al. in 2014) [

29]. Reaction time impacted structural morphology, short durations give incomplete structures, and composition shows oxidation whereas optimal durations give smoother and more well defined NCs (Iravani in 2011) [

30]. Finally, pH impacted both morphology and surface chemistry, low pH tends to generate irregular structures and composition shows some degree of oxidation while near neutral pH promotes controlled nucleation and stabilized NCs (Sathishkumar et al. in 2012) [

31]. This preliminary testing also supported by literature depicts qualitative observations on how different synthesis parameters influences the morphology and composition of green synthesized Cd–Cs mixed oxide NCs.

6.5. HRTEM-EDS

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) images of the Cd–Cs nanocomposites (

Figure 8A) reveal irregular spherical nanoparticles with a pronounced tendency to form aggregates. The average particle size was approximately 45–50 nm, although some agglomerates were observed to reach sizes up to 100 nm. Such aggregation behavior is commonly reported in CdO- and Cs-based nanostructures due to their high surface energy.

In the micrographs, darker contrast regions likely correspond to cadmium-rich crystalline domains, while lighter regions may indicate cesium incorporation. These observations are consistent with previous reports on CdO and Cs-doped composites by Nasrullah et al. [

32]. The nanoscale size and aggregated morphology are expected to enhance the surface reactivity of the nanocomposites, contributing to their antioxidant and anticorrosive properties. Elemental composition analysis via EDS confirmed the presence of Cd, Cs, and O, as shown in

Figure 8B and detailed compositional data provided in

Table S2 of the Supporting Information.

6.6. ZETA-Potential

The zeta potential distribution of the synthesized Cd–Cs nanocomposites exhibits a relatively broad profile with the dominant peak near the central region (

Figure 9), indicating a moderate surface charge and intermediate colloidal stability. This near-neutral potential (mean ± SD,

n = 3;

Table S4 in the Supporting Information) shows moderate electrostatic stabilization of the dispersed particles leads to aggregation. These findings corresponds with TEM micrographs which show clustered NCs, which results from interparticle interactions mediated by surface-bound biomolecules.

Similar zeta potential has been reported for green-synthesized metal and metal oxide NPs, including ZnO, where partial charge neutralization is caused by adsorption of phytochemical residues from the plant extract [

33]. These biomolecules bind to the NCs’ surfaces, which modulate surface charge and the electrostatic layer. This partial aggregation can improve the anticorrosion potential of NCs by promoting the formation of a protective barrier on the metal surface and enhancing interfacial charge transfer inhibition which was supported by Collazo et al. (2022) [

34]. Overall, the measured zeta potential provides information about dispersion behavior of Cd–Cs NCs and also correlates with their surface protection performance in corrosion resistance applications.

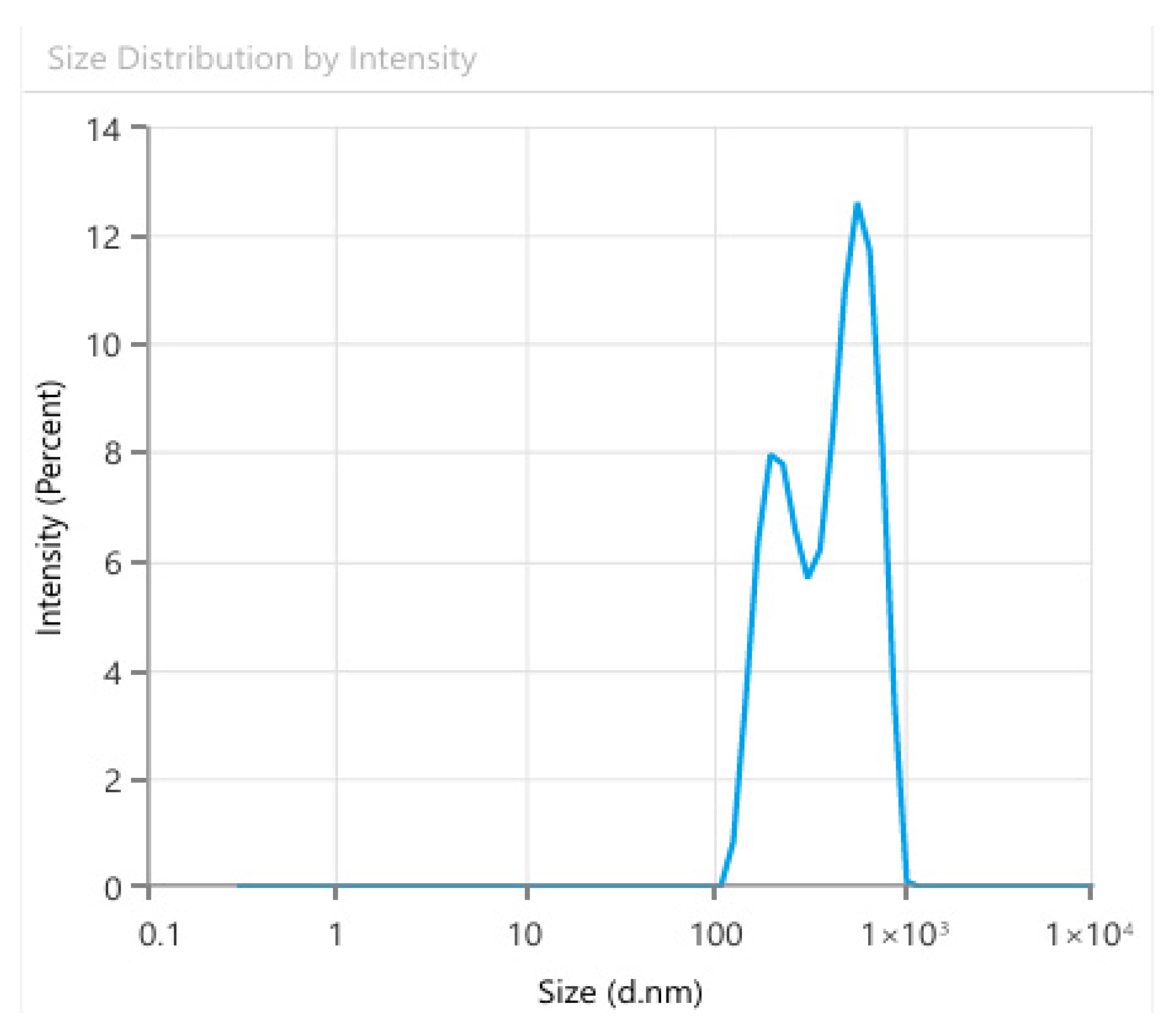

6.7. DLS

Dynamic light scattering analysis of the Cd-Cs nanocomposites depicts a polydisperse particles size distribution with a prominent peak in the range of 300–400 nm, which revealed the hydrodynamic diameter of the NCs. This distribution confirms the successful formation of NCs in the nanoscale region. The evaluated hydrodynamic size leads to the nanoparticle core; solvent layers and some aggregates present in suspension. In contrast, TEM provided a visualization of dried individual particles, indicating a more accurate evaluation of the primary particle size.

The polydispersity index (PDI) was 0.3, which suggests a moderate-size heterogeneity. The experiment was carried out in deionized water at a concentration of 1 mg mL

−1. The higher DLS values highlight the presence of particle aggregation in colloidal suspension. The peak around 300–400 nm (mean ± SD,

n = 3;

Figure 10 and

Table S3 of the supporting Information) corresponds to the stabilized NCs population, confirming that the green synthesis efficiently enhanced nucleation and controlled growth under sustainable conditions. These outcomes are consistent with earlier studies on green synthesis of metal and metal oxide NPs, where phytochemical capping verifies the stability and dispersity of nanoscale [

35].

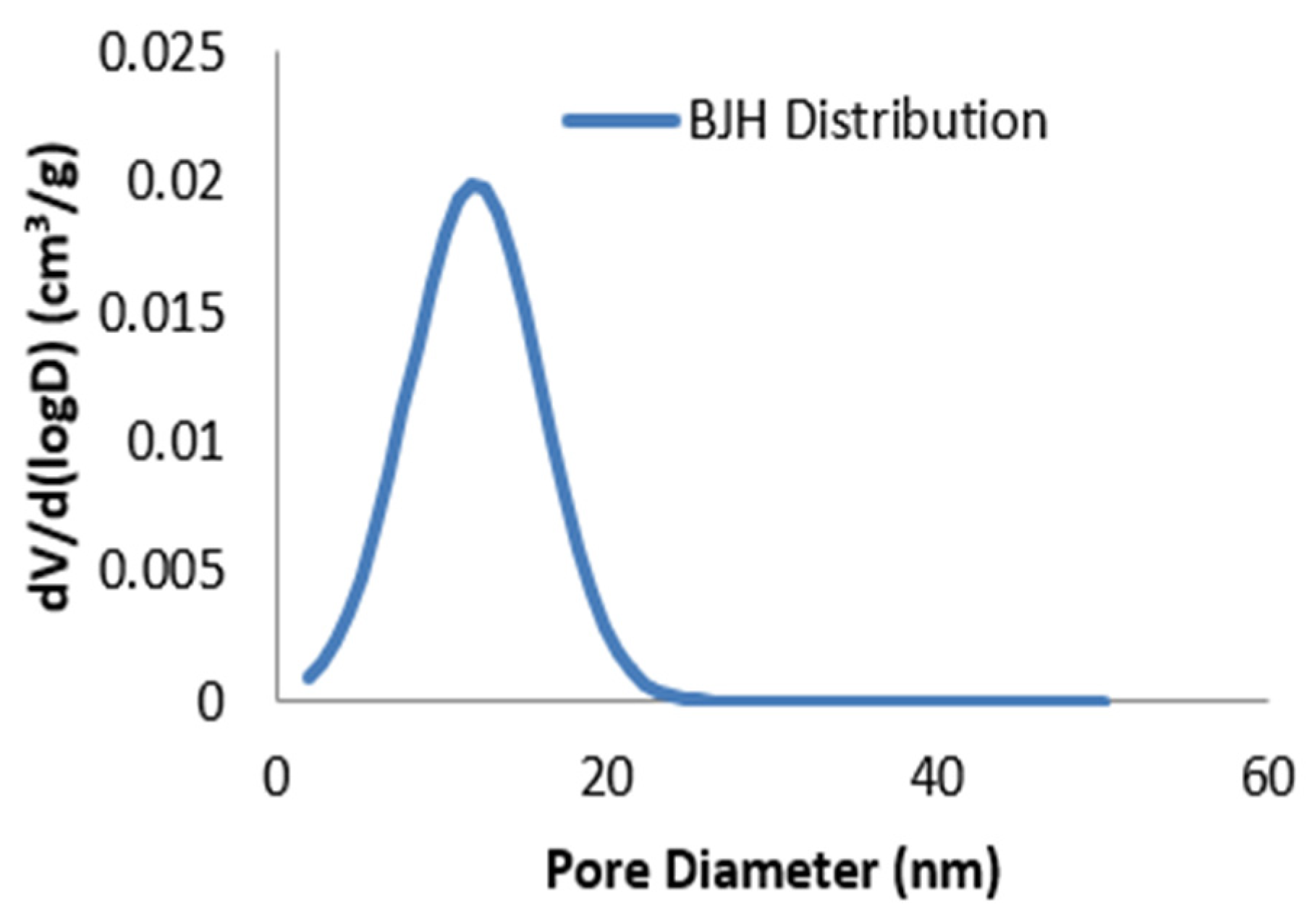

6.8. BET Analysis

The results of nitrogen adsorption–desorption of Cd–Cs NCs were obtained at 77 K to access the surface area and porosity. Multi-point BET analysis provided a specific surface area of 21.3 m

2 g

−1 that suggested moderate surface development. The total pore volume evaluated at P/P

0 ≈ 0.99 was 0.008 cm

3 g

−1, and the BJH desorption pore-size distribution (

Figure 11) indicated an average pore diameter of around 20 nm, which was consistent with mesoporous structure.

The increase in absorbed volume at high relative pressure (P/P

0 > 0.8) corresponds to multilayer adsorption and pore condensation. These outcomes confirmed that Cd–Cs NCs possess a well-defined mesoporous structure with sufficient surface area that enhances the adsorption and processes related to antioxidant activity and corrosion inhibition [

36]. The combination of moderate surface area and mesoporosity enhances the material’s surface reactivity and barrier performance in practical applications.

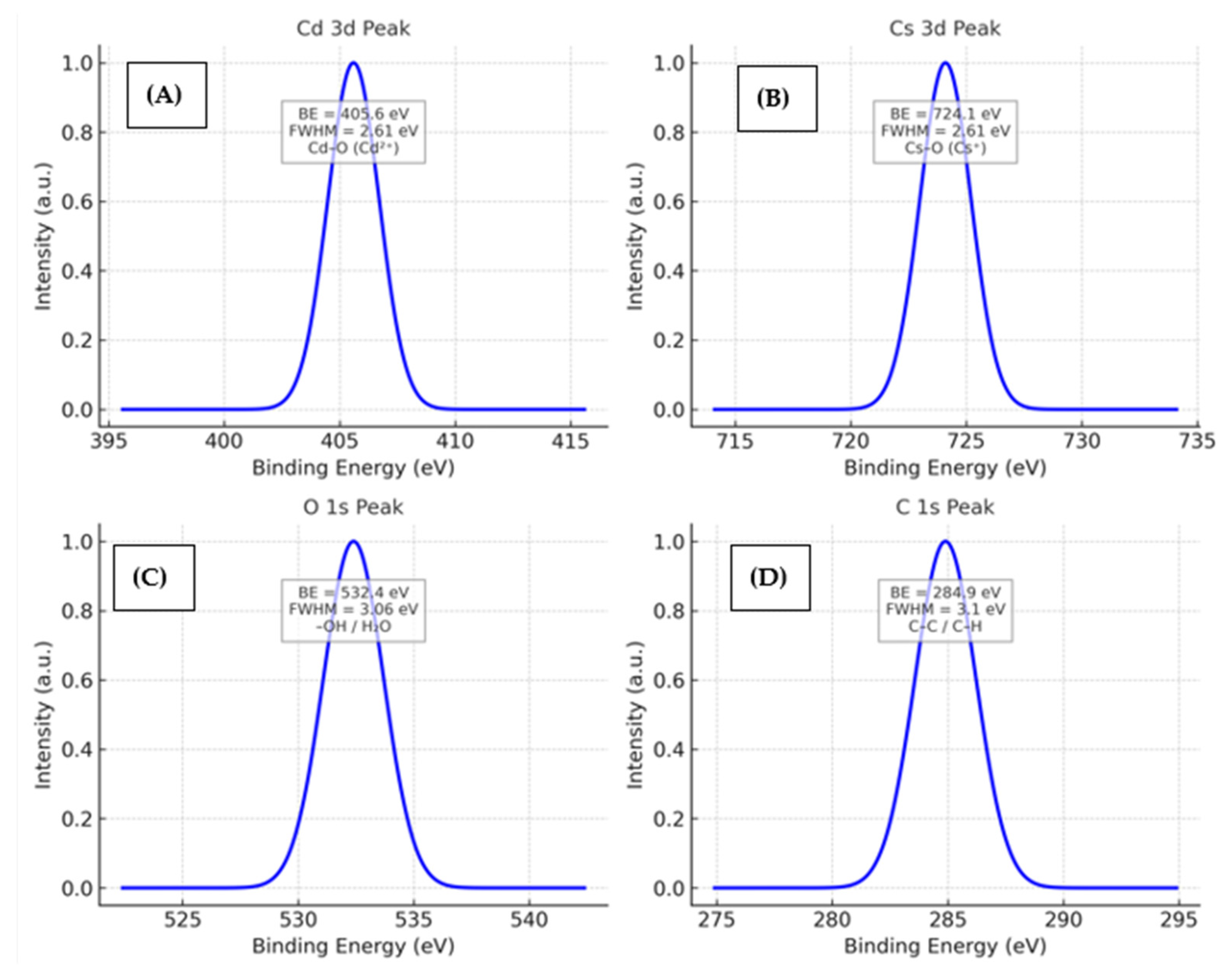

6.9. XPS Analysis

XPS analysis provides direct confirmation of the oxidation states and chemical environment of Cd and Cs within the nanocomposite, which are closely related to its antioxidant and anticorrosion performance. The Cd 3d

5/

2 and Cd 3d

3/

2 peaks at 405.6 and 412.3 eV shown in

Figure 12A,B indicate the presence of Cd

2+ bonded to oxygen (Cd–O), forming a stable mixed-oxide framework. The Cs 3d

5/

2 and 3d

3/

2 peaks at 724.1 and 737.8 eV confirm that Cs is incorporated as Cs

+ in Cs–O (

Table S5 of the Supporting Information) environments rather than metallic Cs or higher oxides. This Cs

+ incorporation enhances the basicity and electron density of the oxide surface, which promotes stronger adsorption of phytochemicals and improves interfacial charge-transfer behavior [

37].

The O 1s spectrum (

Figure 12C) further reveals lattice oxygen (529.6 eV), oxygen vacancies (531.2 eV), and surface hydroxyl groups/adsorbed water (532.4 eV). These oxygen defects and –OH groups not only facilitate radical scavenging interactions—supporting the antioxidant activity—but also contribute to the formation of a compact, reactive, and adherent protective layer on the steel surface, enhancing corrosion inhibition. Moreover, the C 1s (

Figure 12D) shows a dominant peak at ~284.9 eV, corresponding to C–C/C–H bonding, indicating the presence of carbonaceous species. This peak confirms surface carbon originating from the polymer matrix and/or adventitious carbon on the nanocomposite surface. Overall, the confirmed Cd

2+-O and Cs

+-O conditions, along with surface oxygen functionalities, explain the observed synergistic advantage in both antioxidant and anticorrosion behavior of the Cd–Cs nanocomposites.

7. Application

7.1. Antioxidant

7.1.1. ABTS

The antioxidant potential of the synthesized Cd–Cs nanocomposites was evaluated using the ABTS cation radical decolorization assay. This method is based on the ability of antioxidant molecules to quench the blue-green ABTS•

+ radicals, resulting in a measurable decrease in absorbance at 734 nm. The rate of decolorization is directly proportional to the radical-scavenging efficiency of the sample, providing a reliable estimate of its total antioxidant capacity. The ABTS assay is particularly advantageous because it can detect both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidant compounds. The scavenging activity of the synthesized nanocomposites was calculated using the following equation:

7.1.2. DPPH

In addition to the ABTS assay, the antioxidant activity of the biosynthesized Cd–Cs nanocomposites were evaluated using the DPPH free radical scavenging method. Briefly, 4 mg of DPPH was dissolved in 100 mL of methanol, and this solution was mixed with varying concentrations (0–800 mg mL

−1) of the synthesized nanocomposites prepared in both polar (methanol) and non-polar (hexane) solvents. The mixtures were vigorously shaken and incubated in the dark for 30 min. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard reference control. After incubation, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm, and the radical scavenging activity (%) was calculated using the following equation [

38];

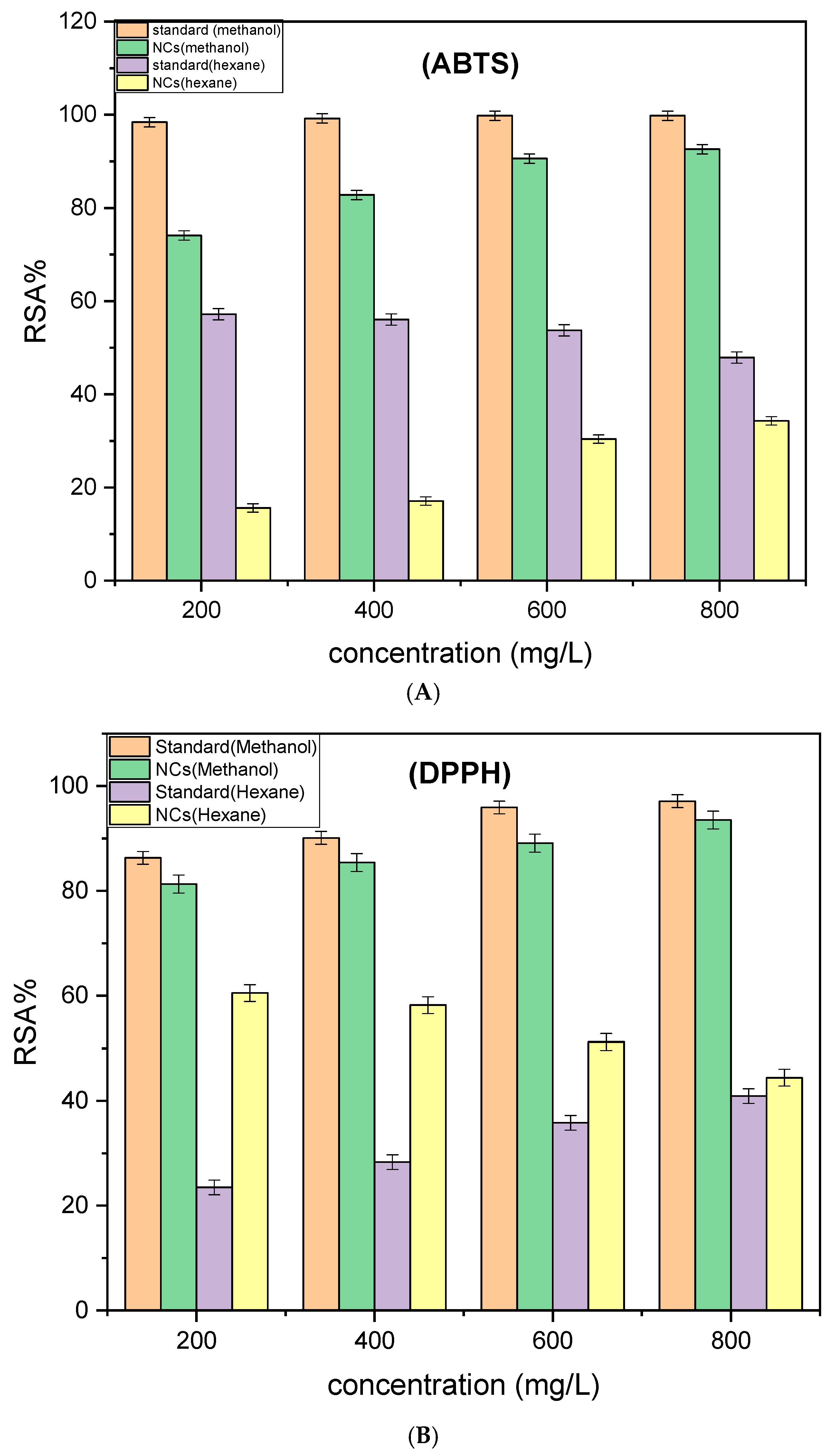

7.1.3. Radical Scavenging Activity of Synthesized Nanocomposites

The antioxidant activity of synthesized NCs arises mainly from the plant-derived bioactive constituents such as phenolics, flavonoids, and terpenoids, which donate electrons and neutralize free radicals. Additionally, Cd–Cs mixed oxide core enhances this effect by providing a high surface area platform that stabilizes and disperses these phytochemicals more effectively. Together, the phytochemicals act as radical scavengers while the oxide matrix supports and enhances their activity.

The antioxidant potential of Cd–Cs nanocomposites was evaluated using both ABTS and DPPH assays, with methanolic extracts exhibiting significantly higher radical-scavenging activity than hexane extracts. All measurements were performed in triplicate or more (n ≥ 3) and results are reported as mean ± SD, with error bars shown in the figures.

In the ABTS assay (

Figure 13A), the methanol standard achieved >99.8% scavenging, while the nanocomposites in methanol reached 92.6% at the highest concentration. Similarly, in the DPPH assay (

Figure 13B), the standard in methanol indicated 97.1% scavenging and NCs in methanol achieved 93.5%. In contrast, hexane showed significantly lower activity, with NCs in hexane varying from 15–30% in ABTS and 35–45% in DPPH. The higher performance in methanol is attributed to the efficient solubilization and extraction of polar antioxidant compounds including phenolics and flavonoids, whereas non-polar nature of hexane limits recovery of these active constituents.

The control comparisons further identify the contribution of phytochemicals to the antioxidant activity of the Cd-Cs NCs. Pure CdO and Cd–Cs oxides showed minimal scavenging (ABTS = 5–15%; DPPH = 3–12%), suggesting that the inorganic oxide matrix does not significantly contribute to radical scavenging. On the other hand, T. ammi extract showed moderate activity, with methanolic extract exhibiting 60–75% scavenging, consistent with the strong ABTS and DPPH performance observed for NCs in methanol of 92.6% and 93.5%, respectively and hexane extract indicating only 10–20% efficiency, aligning with the reduced activity seen in hexane based NCs (15–45%). The mixture of plant extract and CdO showing moderate performance (ABTS = 75–82%; DPPH = 70–78%), indicating enhanced dispersion of phytochemicals without chemical integration. Leaching tests illustrated that the filtrates after washing NCs possessed negligible activity (<5%), whereas the washed NCs attained high scavenging efficiency (ABTS = 85–92%; DPPH = 85–90%). Overall, these outcomes verified that the higher antioxidant effect arises from phytochemicals present on the nanocomposites surface rather than from residual extract or the inorganic core.

The concentration required to scavenge 50% of radicals (IC50) was accessed from dose-response curves. NCs in methanol exhibited stronger radical-scavenging activity, with IC50 values of 62 ± 3 mg mL−1 (ABTS) and 58 ± 3 mg mL−1 (DPPH), compared to 190 ± 5 mg mL−1 and 168 ± 6 mg mL−1 for hexane extracts. This difference indicates the higher solubility of phytochemicals in methanol, which promotes more effective radical scavenging. All assays included appropriate blanks (solvent only) and positive controls (ascorbic acid) to ensure baseline correction and assay validation.

8. Anti-Corrosive

The corrosion inhibition mechanism of mild steel by Cd–Cs mixed oxide nanocomposites synthesized using

T. ammi seed extract is illustrated in

Figure 14. The steel specimens were immersed in the corrosive medium (0.5M HCL) containing the desired concentration of NC suspension, allowing adsorption to occur naturally during the immersion period. This immersion-based exposure method enables the phytochemical-capped nanocomposites to adsorb onto the steel surface through electrostatic and chemical interactions, forming a compact and protective barrier layer. Bioactive constituents of

T. ammi, such as thymol and flavonoids, reduce and stabilize the Cd–Cs nanocomposites and provide functional groups (–OH, –COOH) that enhance surface adhesion and coverage. The Cd–Cs mixed oxide then reinforces this protection by creating a dense, compact inorganic barrier which increases charge transfer resistance and blocks hydrogen ions. Thus, corrosion inhibition is achieved through a combined adsorbed protective film where phytochemicals provide surface binding and the oxide core ensures durable passivation.

This adsorbed layer effectively inhibits the penetration of hydrogen ions, suppresses anodic metal dissolution and cathodic hydrogen emission, and significantly increases the charge transfer resistance, leading to a reduction in the corrosion current density (Iot). These findings aligned with the formation of a of an adsorbed protective layer on the steel surface. Quantitative analysis of adsorption parameters will be explained in future studies.

8.1. Electrochemical Analysis (EIS)

Electrochemical measurements were conducted using a conventional three-electrode system. The working electrode was a mild steel specimen grade IS 2062 embedded in epoxy resin, having an active surface area of 1 cm2 for interaction with the electrolyte. The steel composition made of primarily of iron (99.2%) with minor amounts of carbon and phosphorus. A saturated calomel electrode (SCE) acted as the reference electrode and a platinum wire was used as the counter electrode. The tip-to-surface distance between reference and working electrodes was maintained at 2 mm to reduce ohmic drop.

All experiments were carried out at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C). Before measurements, the electrolyte was either deprived of air by purging with high-purity nitrogen gas for 30 min or left under ambient aerated conditions. The electrodes were dipped in the electrolyte for 30 min to stabilize the open-circuit potential before recording impedance and potentiodynamic polarization data. Current was normalized to the exposed surface area of the steel electrode. Electrochemical method was employed to access the corrosion inhibition efficacy of Cd–Cs nanocomposites and the plant extract in 0.5 M HCl [

39]. All measurements were performed using a NOVA potentiostat controlled by M-Nova 2.1 software.

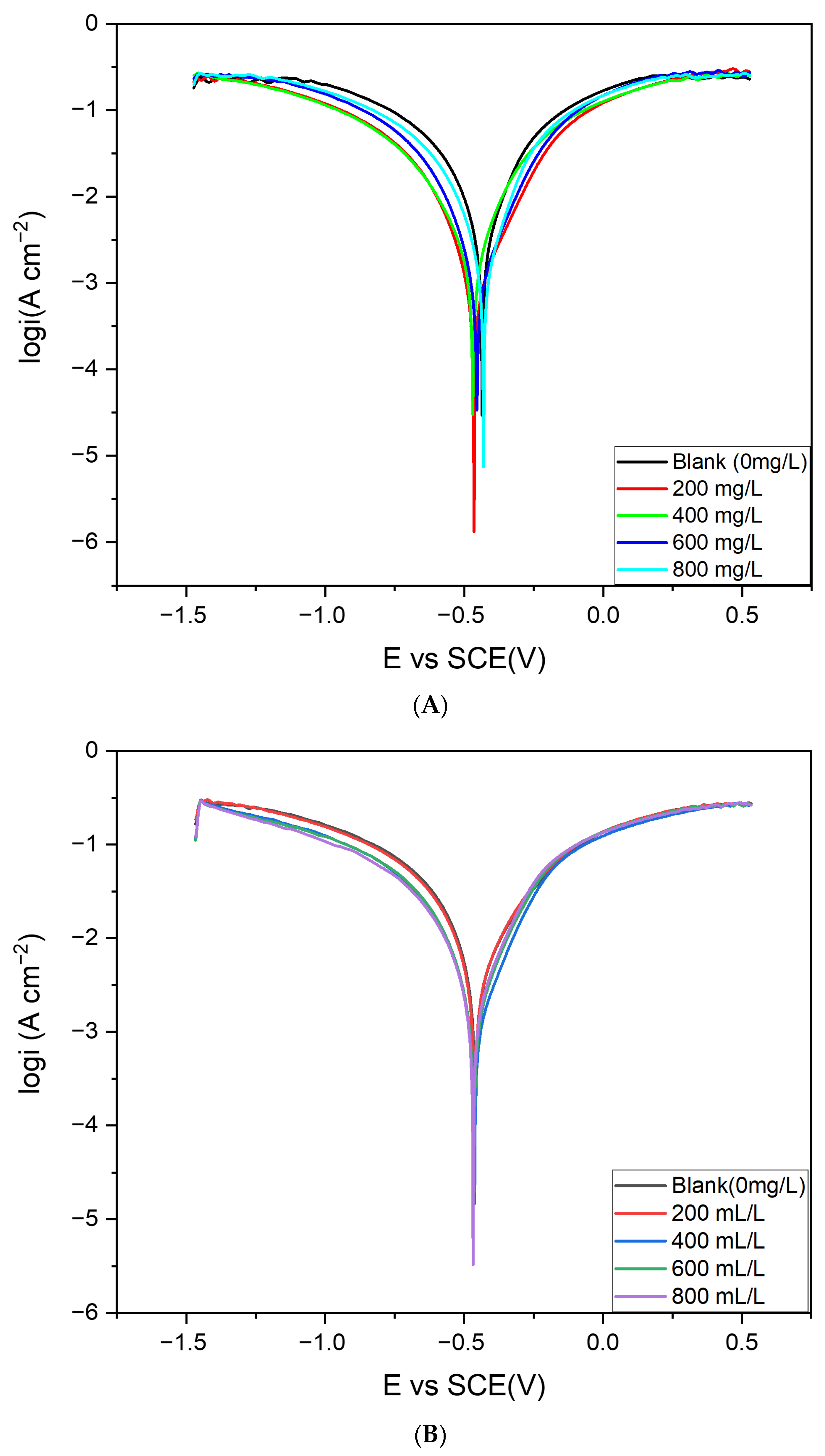

8.2. Potentiodynamic Polarization

Potentiodynamic polarization measurements were performed at a scan rate of 1 mV s

−1 across a potential range of around ±250 mV related to open-circuit potential. Triplicate measurements were observed for each sample concentration to verify the reproducibility. Tafel curves were recorded over a current range of 100 nA to 1 mA and a potential range of −0.1 to 0.1 V. The corrosion inhibition efficiency (I.E.%) was evaluated from the corrosion current density (I

ot) values using the given equation [

40]:

where

I0Corr and

IiCorr represent corrosion current densities in the absence and presence of inhibitors respectively.

Table 4 and

Table 5 summarize the Tafel parameters, including corrosion current density (I

ot), corrosion potential (E

ot), cathodic Tafel slope (βc), and inhibition efficiency (I.E.%). Representative potentiodynamic polarization curves for steel in 0.5 M HCl, in the absence and presence of varying concentrations of Cd–Cs nanocomposites and plant extract, are shown in

Figure 15A,B, respectively. NCs exhibit significantly higher inhibition efficiency compared to PE at equivalent concentrations. This enhanced performance can be attributed to the synergistic interaction between the metallic oxide core (Cd–Cs oxide) and the phytochemical derived organic shell, which enables stronger surface coverage and the formation of a more stable and compact protective barrier. The NCs reduce the corrosion current density (Icorr) to a much greater extent than PE, indicating superior suppression of the charge-transfer process. Overall, comparative analysis confirms that although PE alone has good moderate inhibition efficiency, the NCs deliver significantly improved corrosion resistance due to the combined effects of nanoscale surface coverage.

The presence of the inhibitor significantly suppresses the corrosion current density, indicating effective hindrance of both anodic dissolution and cathodic reactions on the steel surface. With increasing inhibitor concentration, Iot decreased progressively, reaching a maximum inhibition efficiency of 91.0% for the nanocomposites and 88% for the plant extract. This reflects strong suppression of the corrosion reaction due to adsorption of the inhibitor at the steel–solution interface. The corrosion potential (Eot) values shifted only slightly (≤25 mV) relative to the blank, well below the 85 mV criterion, confirming that the inhibitors act as mixed-type, affecting both anodic and cathodic processes.

The anodic (βa) and cathodic (βc) Tafel slopes varied with inhibitor dose. For example, at 400 mg/L, βa decreased while −βc increased compared to the blank, indicating initial inhibition of the cathodic reaction pathway. At higher concentrations (600 mg/L–800 mg/L), both slopes changed simultaneously, suggesting mixed control by suppression of anodic metal dissolution and cathodic reduction. These slopes variations, combined with the reduction in Iot, demonstrate that inhibitor adsorption modifies charge transfer and forms an adsorbed protective barrier film, leading to effective corrosion mitigation.

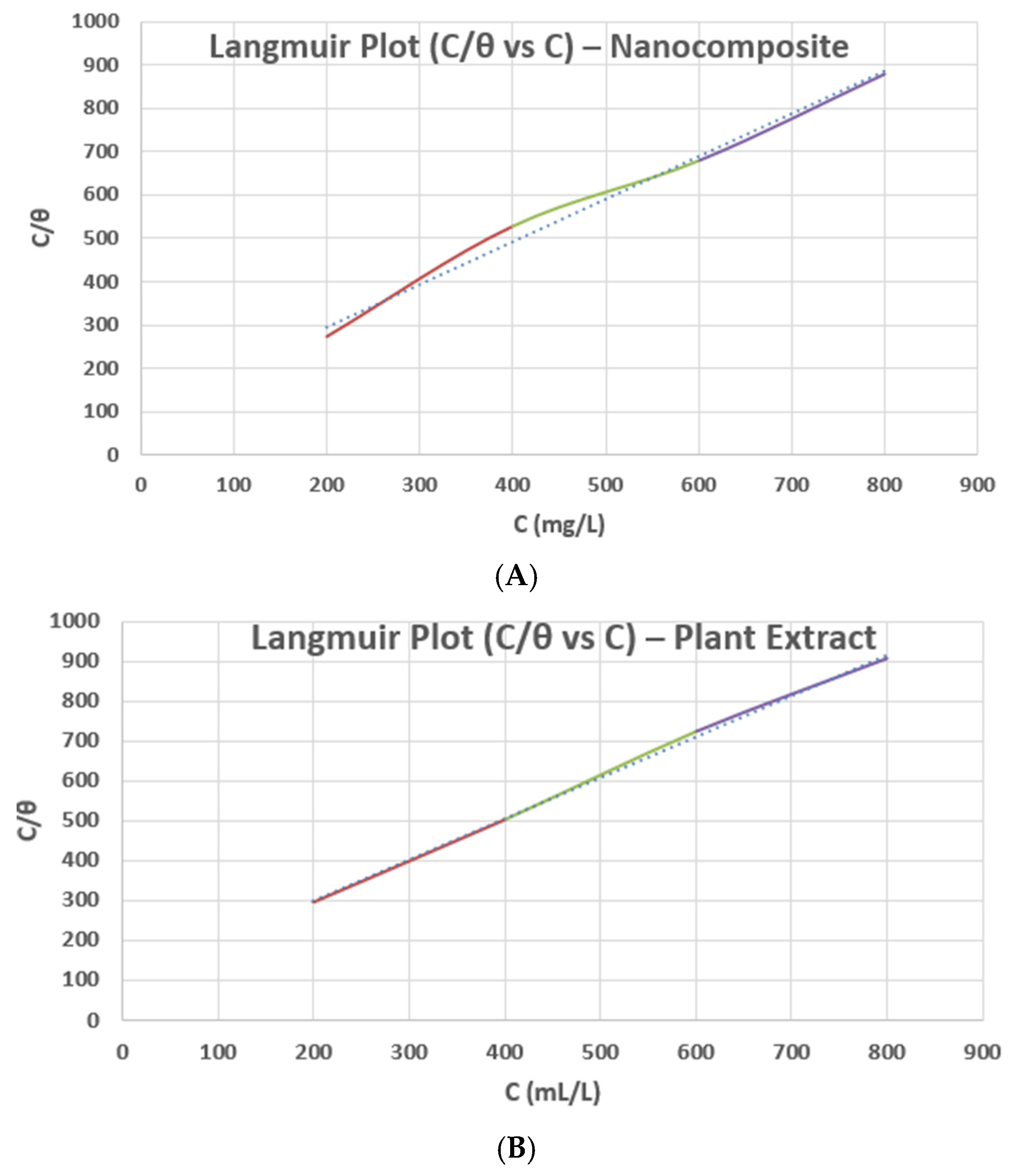

Furthermore, the adsorption behavior of both the nanocomposites and plant extract on the steel surface shown in

Figure 16 was evaluated using Langmuir adsorption isotherms based on the surface-coverage (θ) values derived from PDP inhibition efficiencies. A linear correlation between C/θ and C was obtained for both systems, indicating monolayer adsorption and strong inhibitor surface affinity. This supports the formation of an adsorbed barrier layer where phytochemicals and oxide domains collectively anchor onto the steel surface through chemisorption and electrostatic interactions.

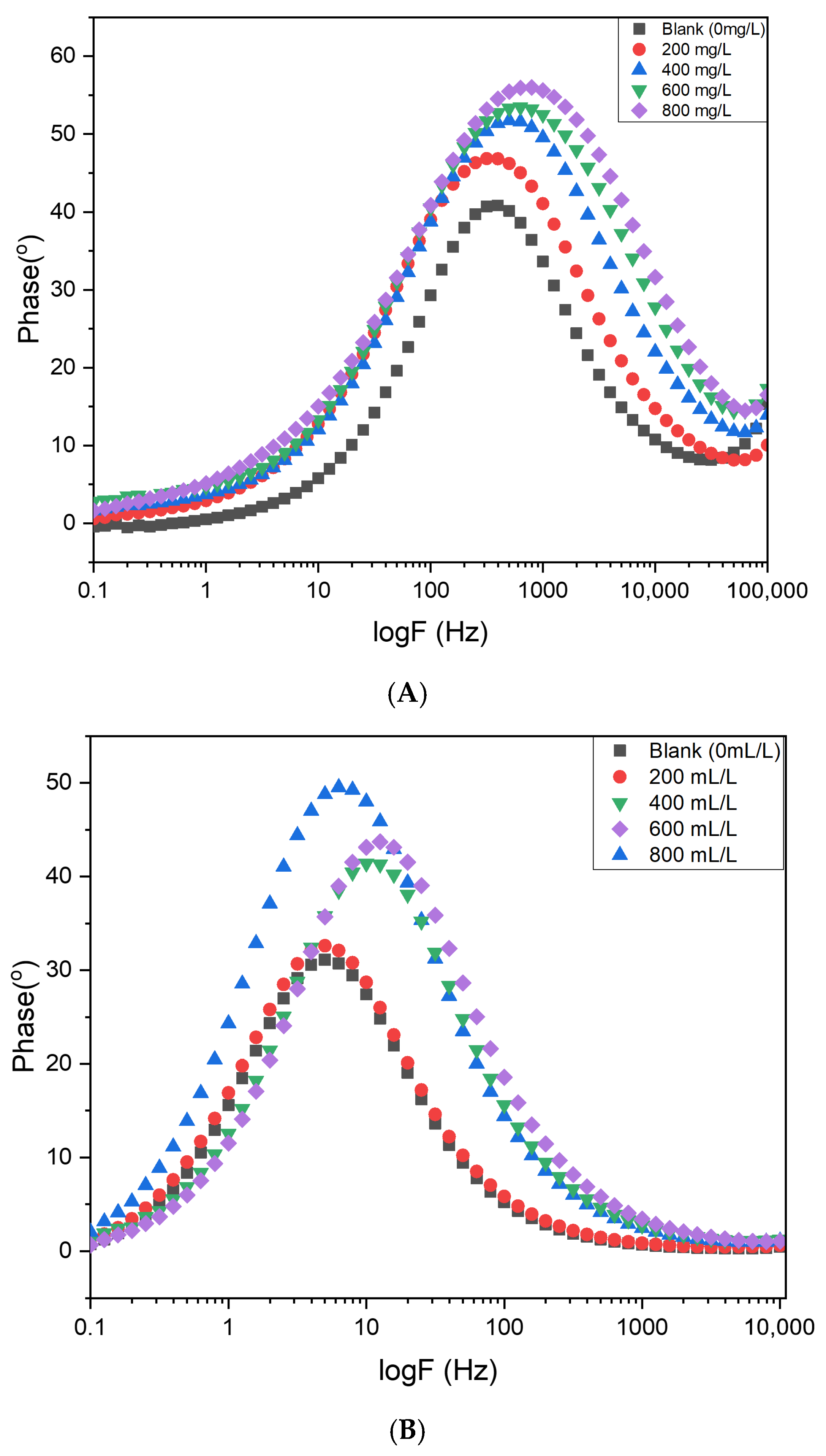

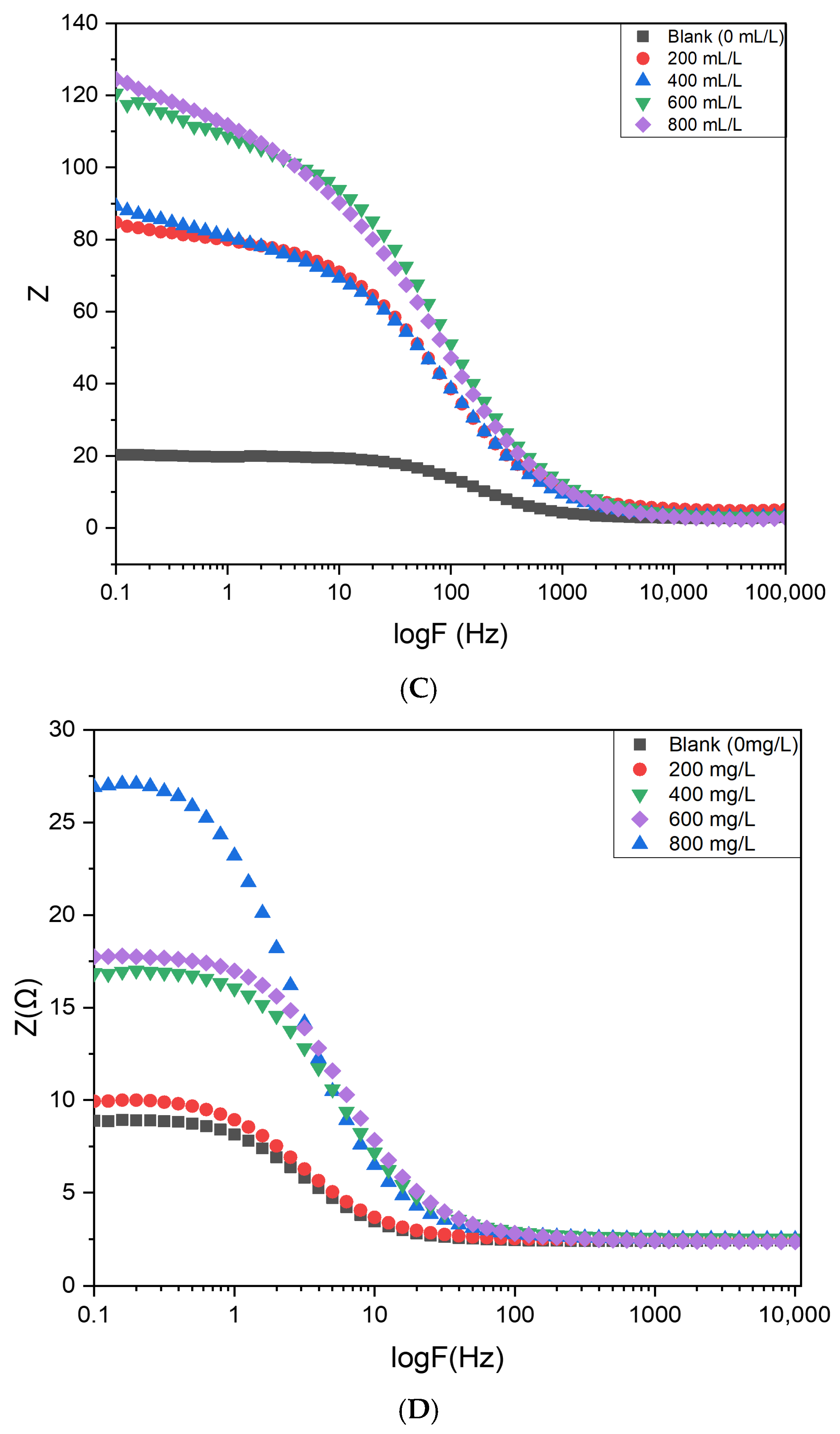

Figure 17 presents the Nyquist plots for mild steel immersed in 0.5 M HCl in the absence and presence of varying concentrations of Cd–Cs nanocomposites. Impedance parameters obtained from equivalent circuit fitting, including charge transfer resistance (Rct) and inhibition efficiency, are summarized in

Tables S6 and S7 in the Supporting Information, based on simulations using NOVA software 2.1. The corrosion process is predominantly controlled by charge transfer, as evidenced by the Nyquist spectra exhibiting a single capacitive semicircle. The diameter of the semicircles increases progressively with increasing inhibitor concentration [

41], indicating enhanced polarization resistance. Maximum inhibition efficiencies of 90.1% and 82.3% were achieved for 800 mg/L of NCs and 800 mL/L of plant extract, respectively.

Figure 18 shows the corresponding Bode plots, displaying both impedance magnitude and phase angle as a function of frequency. The low-frequency impedance magnitude indicates the barrier properties of the surface coating, with higher inhibitor concentrations exhibiting the largest impedance values, indicative of improved resistance to electrolyte penetration. These results confirm that the incorporation of Cd–Cs nanocomposites significantly enhances the protective ability of the steel surface [

42].

9. Gravimetric Analysis (Weight Loss)

Gravimetric experiments were conducted under static (non-dynamic) conditions to ensure adequate interaction between the steel specimens, inhibitor, and corrosive medium. Low-carbon steel coupons (4 × 2 × 0.2 cm) of grade IS 2062 were prepared by sequential polishing with emery papers of progressively finer grades, followed by immersion in acetone for 10 min to remove surface contaminants [

43]. The cleaned samples were wiped with a soft cloth, dried, and their initial weights recorded using a four-digit analytical balance.

The prepared coupons were immersed in 0.5 M HCl solutions containing different concentrations of the inhibitor at room temperature for 24 h and 48 h. Each test was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility, and the results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (

n ≥ 3). Freshly prepared inhibitor solutions were used for each experiment. Inhibition efficiency and associated parameters were determined using standard weight-loss equations as described in the literature [

44]. In addition, the difference in mass between inhibited and uninhibited coupons was used to estimate the amount of Cd–Cs nanocomposite immobilized on the steel surface, which formed the basis for the mass-balance calculation of residual Cd and Cs concentrations in the electrolyte.

where:

W = weight loss (mg/L)

A = surface area (cm2)

T = exposure time (hours)

D = density of the metal (g/cm3)

Tables S8 and S9 in the Supporting Information summarize the weight-loss data for mild steel in the presence of Cd–Cs nanocomposites. Steel specimens treated with the nanocomposites exhibited markedly lower weight loss compared to the blank control after both 24 h and 48 h, confirming the effective barrier protection provided by the adsorbed nanocomposite layer.

The highest inhibition efficiency of 90.1% was obtained at 800 mg/L of nanocomposites after 24 h, corresponding to the lowest corrosion rate of 0.9 mpy, indicating effective surface passivation. After 48 h, the nanocomposite-treated specimens maintained excellent corrosion resistance, reaching a maximum inhibition efficiency of 91.6%, thereby validating the long-term protective stability and durability of the synthesized Cd–Cs nanocomposites.

10. Safety Implications of Cd-Based Nanomaterials

Although the current study focuses on plant-based synthesis and the functional potential of Cd–Cs NCs, it is crucial to acknowledge the environmental implications attributed with the Cd-based system. Cadmium is a regulated heavy metal with some known toxicity and could pose environmental concerns [

45].

Based on a mass-balance estimation using the inhibitor dosage (mg L

−1), SEM–EDS metal composition of the Cd–Cs nanocomposites (

Table 3), and the adsorbed inhibitor mass obtained from gravimetric studies, the total residual concentrations of Cd and Cs remaining in the electrolyte were estimated to be in the ranges of approximately 80–320 mg L

−1 (Cd) and 50–200 mg L

−1 (Cs), depending on the nanocomposite dosage. These values represent the total nanocomposite derived metals present in the solution and not necessarily the concentration of freely dissolved Cd

2+ or Cs

+ ions, because a substantial fraction remains immobilized on the steel surface and/or incorporated into corrosion products as part of the protective layer. Direct quantification of dissolved Cd and Cs would require ICP based leaching analysis, which will be undertaken in future work to obtain precise environmental-risk evaluation.

Future work should include LCA based environmental impact analysis and ecotoxicity assays to fully study the environmental safety of these materials. Such examinations are significantly important before considering large scale application in corrosion inhibition systems.

11. Conclusions

Cd–Cs mixed oxide nanocomposites were successfully synthesized by green method using Trachyspermum ammi seed extract as a natural stabilizing and capping agent. This ecofriendly approach omits the need for harmful and toxic chemicals, promoting nanocomposites synthesis. Comprehensive characterization by XRD, FTIR, UV–Vis spectroscopy, SEM–EDS, zeta potential, DLS, HR-TEM EDS, BET, and XPS confirmed the crystalline nature, uniform morphology and nanoscale dimensions of the synthesized nanocomposites.

The antioxidant activity evaluated by using DPPH and ABTS assays illustrated strong free radical scavenging performance associated to the high surface area and phytochemical functionalization of the nanocomposites. Corrosion inhibition studies performed using potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) and gravimetric analysis showed a substantial reduction in corrosion current density minor shifts in corrosion potential and significant decrease in metal weight loss confirming the synthesis of a stable adsorbed protective film on surface mild steel. A theoretical estimation of the residual Cd and Cs levels in the electrolyte was also provided, while detailed ICP-based leaching studies are planned for future work to more rigorously address environmental safety.

Overall, this study underscores the dual functionality of T. ammi-mediated Cd–Cs nanocomposites as efficient agents for mild steel protection in 0.5 M HCl acidic medium, while cadmium plays a key role in the observed performance. Future research may focus on surface modifications to improve safety, environmental compatibility, and long-term stability, thereby improving the potential of these nanocomposites for industrial applications.