1. Introduction

Digital storytelling, combining personal narratives with digital media, has emerged as a transformative approach to create engaging content across various media. It integrates traditional storytelling with modern technology, enabling digital creators to develop narratives for diverse audiences [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. In cultural heritage tourism contexts, digital storytelling holds significant potential for enhancing visitor engagement. For example, it can make complex historical content more accessible and interesting through short visual narratives [

2,

7]. Research demonstrates that digital storytelling techniques in cultural heritage tourism contexts not only enrich online visitor experiences but also help to increase visits to physical sites. Thus, digital storytelling can create connections between virtual and physical cultural experiences [

1,

6,

8].

Cultural and heritage sites worldwide have successfully implemented digital storytelling through virtual museums and smartphone applications [

9,

10]. Digital storytelling facilitates accessibility by providing virtual access to sites that may be expensive to get to, remote, fragile, or no longer exist, thereby overcoming physical limitations to expand the potentials of cultural heritage tourism [

11,

12].

Despite these advantages, digital storytelling faces significant challenges that limit its effectiveness and reach. Traditional digital storytelling frameworks [

4,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] were developed for general, educational, or entertainment contexts rather than for social media platforms. Thus, these frameworks do not focus on the unique demands of contemporary youth engagement through social media platforms [

10]. This has left content creators without evidence-based guidelines for producing effective short-form cultural heritage tourism videos that chime with youth audiences. There is a critical gap between theoretical frameworks and practical requirements.

Compounding this challenge, there is a disconnect between presentation methods and youth preferences. Young people aged 18–25 may show limited interest in information that is presented in a formal, academic fashion, as this does not align with their digital consumption habits, especially on social media. This represents a significant barrier to cultural heritage tourism engagement, with young visitors often finding museums unmotivating and removed from their interests and lifestyles [

19,

20,

21].

Toward addressing this issue, prior research [

22] introduced the Integrated Digital Storytelling for Social Media (IDSM) framework, consisting of 13 elements. That initial study provided only a literature review and initial framework summary. The present paper tests the framework in a sample population. This study aims to investigate how youths aged 18–25 perceive and prioritize the 13 elements of the IDSM framework in social media-enhanced cultural heritage tourism contexts and to explore their specific preferences for cultural heritage tourism video content. The research addresses the critical need to establish and validate guidelines that connect theoretical frameworks with the practical requirements of social media content creation, providing practical value for cultural heritage tourism practitioners and content creators. The findings will enable cultural heritage tourism organizations, museums, and content creators to develop evidence-based strategies for producing engaging short-form videos that effectively motivate youth engagement with cultural heritage. Furthermore, the research delivers actionable insights that can transform how cultural heritage tourism content is created and shared across social media platforms, ultimately enhancing the accessibility and appeal of cultural heritage experiences for younger generations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. From Cultural and Heritage Tourism to the Emergence of Cultural Heritage Tourism

Cultural tourism is defined as travel and exploration undertaken by individuals primarily driven by learning motivations, encompassing educational tours, artistic experiences, and historical site visits [

23]. This multifaceted field incorporates both past and present manifestations through products, processes, and locations that facilitate visitor engagement with local traditions, alongside sightseeing and contemporary artistic events [

24]. In contrast, heritage tourism refers specifically to the inclination to visit historical sites and engage with artifacts that symbolize the past, with authenticity recognized as a fundamental element. Heritage tourism focuses exclusively on past-oriented products and historical attractions that preserve and interpret previous eras and civilizations [

25,

26]. Cultural heritage tourism represents a convergence of these concepts, referring to travel to specific locations and events that accurately portray the histories and traditions of both past and present. This approach combines historical preservation with contemporary interpretation, enabling visitor engagement with living traditions alongside historical artifacts [

27,

28]. This distinction is particularly relevant for digital storytelling frameworks targeting youth engagement, as contemporary audiences increasingly seek authentic cultural experiences that connect historical narratives with present-day cultural relevance, requiring approaches that transcend traditional heritage-focused methodologies to encompass broader cultural tourism contexts.

2.2. Cultural Heritage Tourism Context

Cultural heritage tourism contexts encompass heritage sites, cultural precincts, and locations facilitating authentic cultural experiences within defined geographic parameters. Extension includes temples, museums, historical districts, traditional markets, and artisan quarters where visitors engage with cultural heritage elements. Inclusion requires (1) tangible or intangible cultural heritage significance, (2) interpretive educational opportunities regarding local culture and history, (3) authentic cultural experiences distinguishable from recreational tourism, and (4) visitor engagement motivated by cultural learning rather than entertainment purposes. This framework ensures methodological clarity for identifying cultural heritage tourism environments and distinguishing them from general tourism contexts within the research parameters [

29,

30].

2.3. Digital Storytelling and Cultural Heritage Tourism

Digital storytelling, combining traditional narrative techniques with contemporary digital media technologies, has been widely applied as a transformative approach for enhancing cultural heritage tourism experiences [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Studies suggest that digital storytelling can enhance both online and onsite user experiences and increase motivation to visit physical locations. This is to say, it can help forge connections between virtual and real-world cultural engagement [

8,

11,

31,

32,

33,

34]. However, significant implementation challenges persist, and traditional frameworks demonstrate limitations when applied to social media integration and youth engagement strategies [

22].

2.4. Cultural Heritage Tourism and Youth

Research indicates that young people aged 18–25 demonstrate limited participation in cultural heritage tourism activities, primarily due to misalignment between presentation methods and youth digital consumption preferences [

2]. This demographic gap presents significant implications for the sustainability of cultural heritage tourism, as early engagement patterns influence long-term cultural heritage site viability [

2,

19,

35,

36].

Most museums and cultural sites worldwide continue to employ formal, academic information delivery methods that fail to connect with young visitors’ interests, lifestyles, and communication preferences. These traditional approaches, characterized by extensive textual information and static displays, contrast sharply with youth expectations of interactive, visually engaging, and socially shareable experiences [

19,

21].

The consequences of youth disengagement extend beyond immediate visitor statistics to encompass broader cultural heritage preservation concerns. Research demonstrates that early exposure to cultural heritage tourism significantly influences adult participation patterns, making youth engagement essential for long-term cultural site sustainability [

19,

37]. Furthermore, young visitors often serve as cultural ambassadors within their social networks, amplifying the impact of successful engagement strategies through peer influence and social media sharing [

19,

35].

2.5. Youth and Digital Storytelling and Social Media

Research demonstrates that social media environments facilitate authentic self-representation dynamics so that digital presence correlates positively with self-concept clarity. This suggests that authentic social media engagement contributes to stable self-perception development among young users [

38,

39,

40]. Consequently, in cultural heritage tourism, connections with personal identity can help to enhance heritage engagement effectiveness [

39].

Social media platforms serve as effective spaces for youth participation in community-driven narrative construction and collective identity formation. Studies indicate that platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok function as significant value transmission mechanisms, reflecting demands for authenticity in digital interactions [

40,

41,

42]. These platforms enable youths to construct and share personal narratives that foster community cohesion while expressing individual interests and motivations [

41].

The integration of immersive technologies in youth social media engagement promises to have substantial implications in cultural heritage contexts. Research reveals that virtual reality and augmented reality implementation can significantly impact emotional and behavioral responses, with quantifiable effects on flow state and satisfaction metrics [

43]. Furthermore, research into intercultural communication competence development through social media platforms indicates that the use of YouTube, in particular, can effectively facilitate intercultural competence development among young tourists [

44].

Analysis of the economic impact of social media among youths reveals significant revenue generation patterns and entrepreneurial opportunities. Statistical analysis demonstrates that youth users account for 30–40% of advertising revenue on social media platforms, highlighting the economic significance of this demographic segment [

45].

2.6. The IDSM Framework: Theoretical Foundation

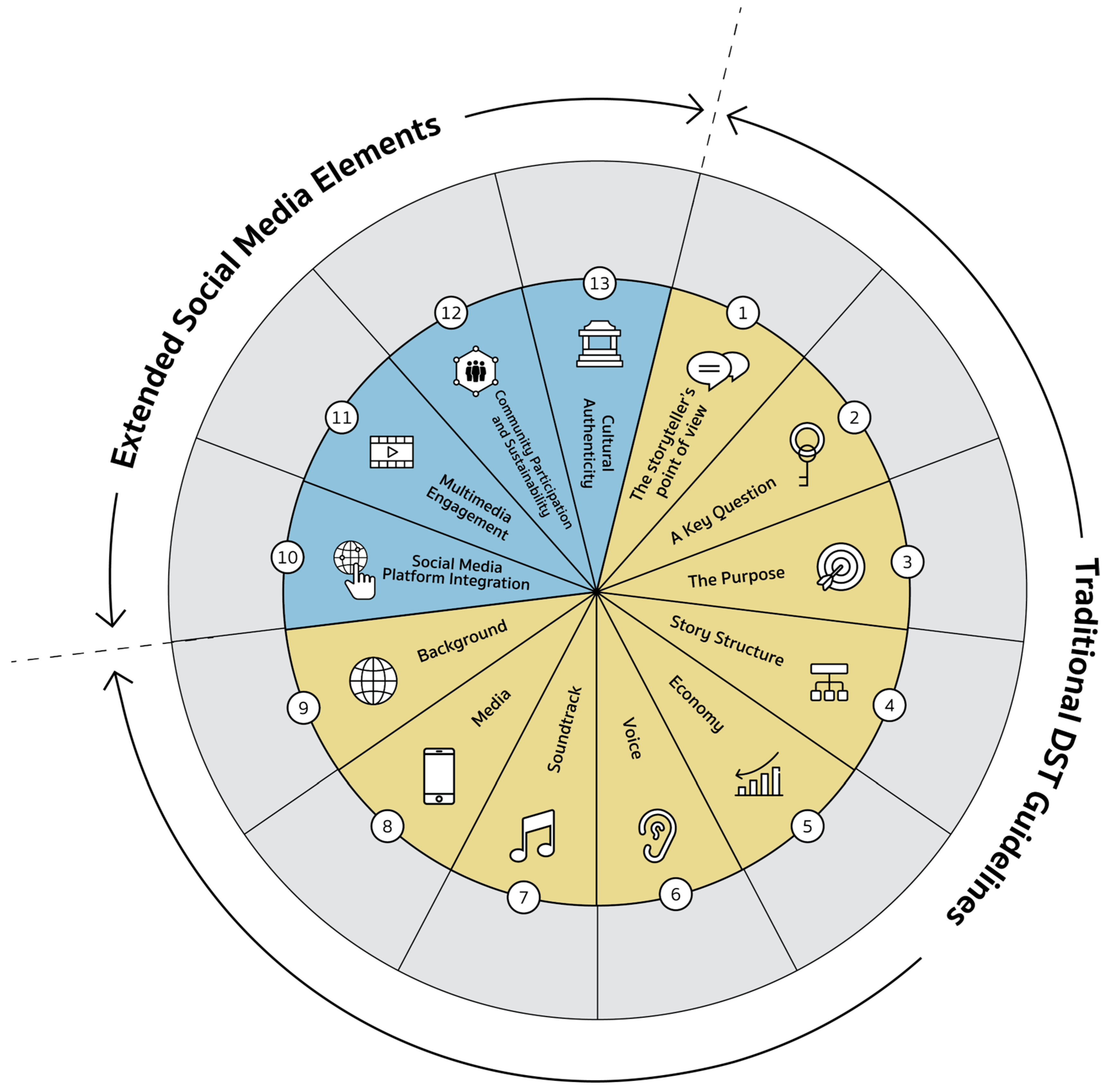

The IDSM framework (

Figure 1 and

Table 1) represents a preliminary theoretical synthesis integrating traditional digital storytelling principles with contemporary social media engagement requirements, specifically designed for cultural heritage tourism applications. This initial framework emerged from a systematic literature review (SLR) and analysis through the Scopus database in four interconnected research domains: (1) digital storytelling and cultural tourism, (2) digital storytelling and social media, (3) youth and cultural tourism, and (4) youth interaction with digital storytelling through social media platforms [

22]. VOSviewer software 1.6.20 was used to identify thematic clusters across 688 articles, revealing distinct patterns that informed the framework’s structural components.

The initial framework builds upon established digital storytelling guidelines while addressing critical gaps identified in contemporary social media contexts. Nine traditional elements encompass fundamental narrative components: storyteller’s point of view, key questions, purpose, story structure, economy, voice, soundtrack, media selection, and background setting [

4,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Traditional digital storytelling, as defined in this research context, refers to established narrative frameworks developed prior to social media platform integration, encompassing nine fundamental elements identified in pre-digital and early digital storytelling literature [

22]. However, systematic analysis revealed that existing guidelines are inadequate to meet platform-specific social media requirements regarding youth engagement in cultural heritage tourism contexts [

22].

Therefore, four additional framework elements identified through the thematic cluster analysis were added. “Social media platform integration” encompasses platform-specific features that facilitate interactive storytelling, authentic narrative sharing, and community engagement mechanisms [

46,

47]. “Multimedia engagement” integrates diverse media elements including immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality to enhance cultural heritage content accessibility [

48]. “Community participation and sustainability” incorporates co-created content development methodologies and community-driven storytelling approaches specifically designed for youth engagement [

49,

50]. “Cultural authenticity” encompasses genuine cultural representation that maintains heritage accuracy without excessive embellishment, balancing authentic content with engaging presentation methods for youth audiences [

49,

51,

52].

In brief, the initial framework constitutes an exploratory integration of established digital storytelling guidelines while addressing critical gaps identified in contemporary social media contexts for youth engagement in cultural heritage tourism.

Table 1.

Details of the initial IDSM framework [

22] pp. (16–17).

Table 1.

Details of the initial IDSM framework [

22] pp. (16–17).

| Factors | Explanation | References |

|---|

| 1. Storyteller’s point of view | The main perspective or central argument from which the narrative is presented, establishing the author’s viewpoint and narrative stance. | [20,22] |

| 2. Key question | A pivotal inquiry that sustains audience attention and provides narrative focus, guiding the story toward resolution. |

| 3. Purpose | Clear narrative objectives established early and maintained consistently throughout the presentation to ensure focused storytelling direction. |

| 4. Story structure | The major events, challenges, and dramatic progression that define the narrative arc and constituent story elements. |

| 5. Economy | Optimal content balance that conveys the story effectively without overwhelming the audience, employing minimal yet meaningful narrative elements. |

| 6. Voice | The storyteller’s appropriate emphasis and personal engagement with the narrative, providing proper focus and connection to the story. |

| 7. Soundtrack | Musical elements and sound effects that support and enhance the narrative, creating emotional engagement and atmospheric enhancement. |

| 8. Media | The technological platforms and delivery methods employed for content presentation, including mobile devices, television, or internet-based systems. |

| 9. Background | The environmental setting and contextual world where the narrative unfolds, establishing atmospheric foundation and spatial context. |

| 10. Social media platform integration | Choosing different social media platforms based on their unique tools and features to connect with target groups | [46,47,53,54] |

| 11. Multimedia engagement | Choosing diverse media formats and technologies to make materials more interesting to the target audience | [32,48,55,56,57,58,59] |

| 12. Community participation and sustainability | Encouraging local communities and users to contribute their own stories and content | [6,42,49,50] |

| 13. Cultural authenticity | Genuine cultural representation that maintains heritage accuracy without excessive embellishment, balancing authentic content with engaging presentation methods for youth audiences | [49,51,52] |

3. Research Methodology

This study employed a quantitative methodology using a structured questionnaire distributed during weekends to 100 youths aged 18–25 in Bangkok, Thailand, from March to April 2025 (see

Figure 2). The lack of standardized age ranges for youths creates significant methodological challenges in comparing research findings across studies. The definitional frameworks vary across cultural environments and institutional contexts. Therefore, this study adopts the 18–25 age parameter, extending the United Nations’ youth definition (15–24 years) relevant to independent cultural heritage tourism decision-making [

60]. The 18-year minimum ensures participants possess legal autonomy for travel decisions. Moreover, the 25-year maximum maintains alignment with Generation Z demographic boundaries, representing digital natives with distinct social media consumption patterns and cultural engagement preferences that fundamentally differ from preceding generational cohorts.

It also employed an exploratory on-site intercept survey methodology, a well-established approach in tourism research for capturing visitor experiences within cultural contexts [

61]. The purposive sampling strategy prioritized exploratory investigation over statistical representativeness, enabling focused examination of youth preferences during active cultural heritage tourism engagement.

The research conducted at various cultural heritage tourism sites around Rattanakosin Island, Bangkok, in an area covering 4.142 square kilometers and encompassing museums, heritage sites, temples, markets, and cultural streets. Data collection was conducted at six cultural heritage tourism locations: (1) the exterior grounds of the Temple of the Emerald Buddha; (2) Sanam Luang, the historic public square; (3) the National Museum; (4) Museum Siam; (5) Wat Pho temple; (6) Wang Lang Community, a local cultural district representing living heritage practices. These locations were selected to ensure diverse representation of both institutional cultural sites and community-based cultural heritage tourism experiences.

Next, according to the National Statistical Office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, the total number of Thai youths (18–25 years old) residing in Thailand is approximately 7,622,345 [

62]. Sample size calculation using Yamane’s formula with 10% margin of error yielded 100 participants [

63]. The study utilized anonymous data collection to ensure participant confidentiality and encourage honest responses.

Participant selection employed a purposive sampling methodology targeting youths aged 18–25 years. Research assistants approached potential participants at cultural sites, initially inquiring about age eligibility before requesting participation. Individuals meeting the age criteria (18–25 years) were invited to participate in the questionnaire survey, with informed consent obtained prior to data collection. This approach ensured systematic adherence to demographic parameters while maintaining ethical research standards and voluntary participation principles.

The questionnaire comprised three distinct sections utilizing different measurement scales:

Section 1 contained four demographic questions employing nominal and ordinal scales to collect participant characteristics including gender, age group, education level, and number of cultural heritage tourism trips per year.

Section 2 consisted of 20 questions utilizing mixed measurement scales—categorical/nominal scales for video orientation preferences, social media platform usage frequency, media source preferences, video style preferences, and duration preferences—and 5-point Likert scales (1 = least to 5 = most) for evaluating the 13 IDSM framework elements regarding digital storytelling effectiveness in cultural heritage tourism contexts.

Section 3 comprised one open-ended question inviting participant suggestions for ideal cultural heritage tourism video content, enabling detailed insight into desired characteristics and features.

The questionnaire used simple language instead of technical terms to help participants understand the questions clearly. The academic words from

Table 1 were changed into easy statements that young people could easily understand.

4. Results

Demographic analysis of participants (N = 100) demonstrated targeted sampling within the specified youth demographic presented in

Table 2. The sample comprised 63% female participants, with an age range of 18–20 years (45%) and 21–23 years (25%). Regarding education, undergraduate students constituted 80% of participants and high-school graduates made up 20%. As for cultural heritage tourism engagement patterns, 61% reported 1–3 cultural heritage tourism visits per year.

From

Table 3, it can be seen that all participants (100%) agreed that social media videos possess the capacity to motivate cultural heritage tourism engagement. Some 60% favored a vertical video format. Content production preferences revealed a significant trend toward authenticity versus professional quality: 64% of participants preferred simple mobile phone recordings, while 24% favored professional live-action footage. Significantly, preferences regarding video content suggested optimal engagement durations of 31–60 s (48% of responses) and 1–2 min (37% of responses).

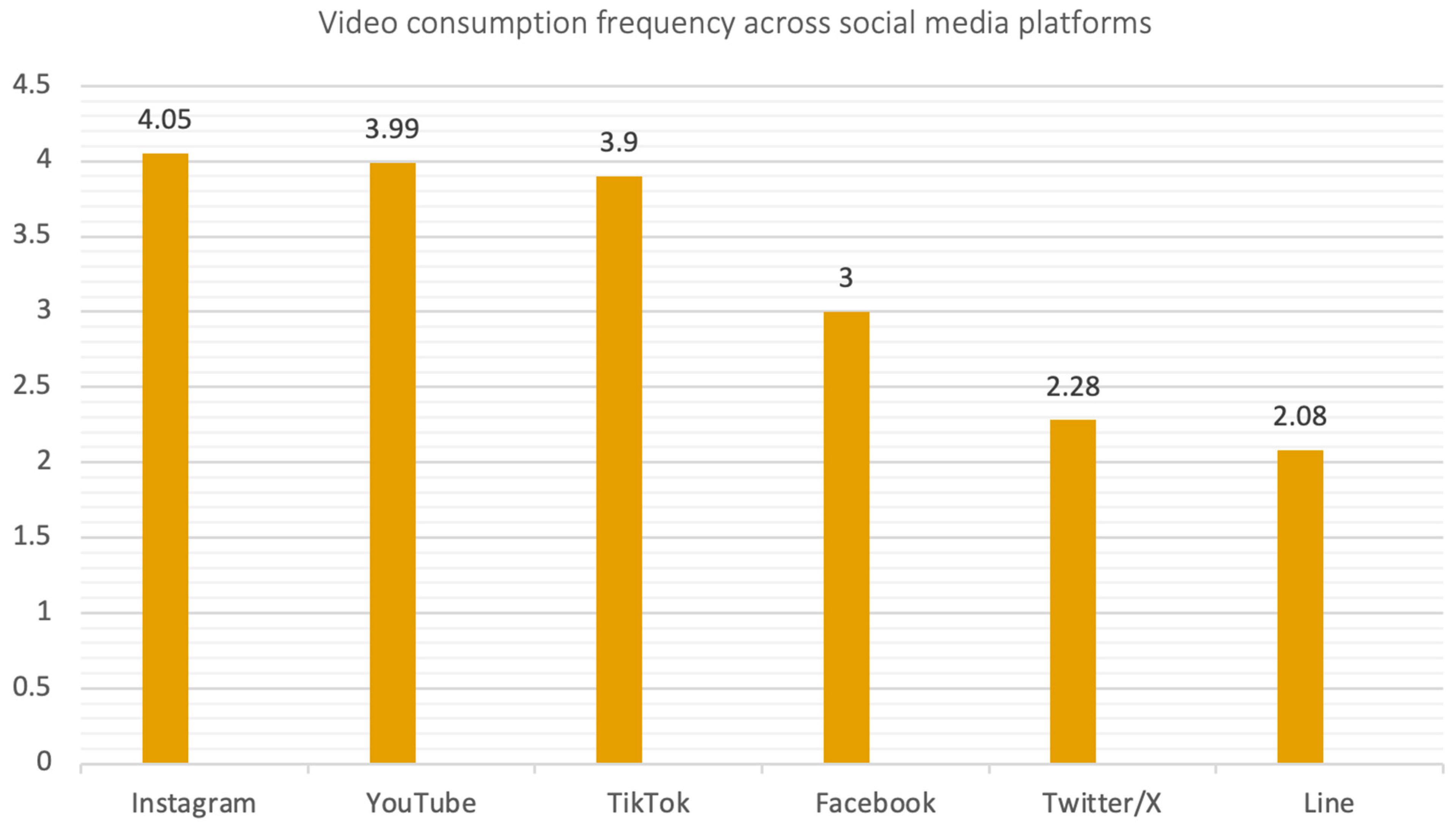

Distinct usage patterns were found for videos on social media platforms, as presented in

Figure 3. Instagram demonstrated the highest engagement frequency (M = 4.05, on 1–5 scale), followed by YouTube (M = 3.99) and TikTok (M = 3.90). Facebook maintained moderate engagement levels (M = 3.00), while Twitter/X (M = 2.28) and Line (M = 2.08) showed limited youth engagement.

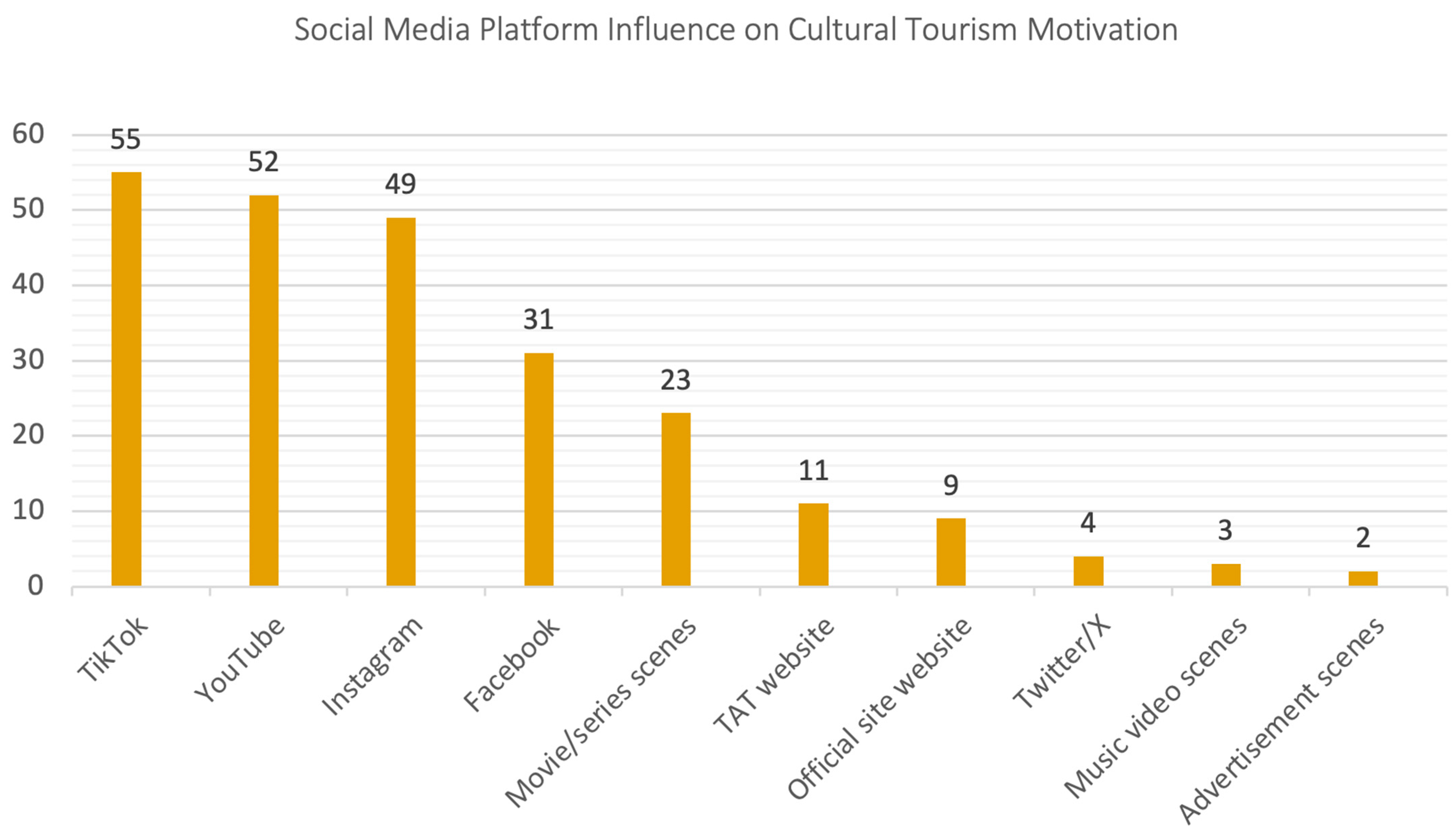

Notably, cultural heritage tourism motivational influence patterns differed from usage frequency, as presented in

Figure 4: TikTok emerged as the primary motivational source (55% of participants), followed by YouTube (52%) and Instagram (49%). Traditional promotional channels, including official tourism websites, demonstrated minimal motivational impact (9–11% participant selection), highlighting youth preference for peer-generated social media content over institutional communications.

Next,

Table 4 presents results on the 13 IDSM framework elements, adopting a 5-point Likert scale: 1.00–1.49 = Strongly disagree; 1.50–2.49 = Disagree; 2.50–3.49 = Neutral; 3.50–4.49 = Agree; 4.50–5.00 = Strongly agree.

Internal consistency reliability analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of α = 0.7813, indicating acceptable reliability and confirming the scale measurement validity. Firstly, the “cultural authenticity” element emerged as the highest-ranked consideration among youth participants (M = 4.54, Strongly agree, SD = 0.68). This establishes authenticity as the foremost requirement for effective youth engagement in cultural heritage tourism digital content. Traditional storytelling elements demonstrated exceptional performance, with “story structure” (M = 4.12, Agree, SD = 0.71) and “content economy” (M = 4.11, Agree, SD = 0.75) receiving strong endorsement. These results confirm youth preference for clear narrative frameworks and concise messaging approaches. Technical production standards proved critical for youth acceptance, with substantial agreement (M = 4.02, Agree, SD = 0.85) on the requirement for “video quality”. “Community participation” demonstrated significant appeal (M = 4.24, Agree, SD = 0.80), validating the importance of local stakeholder involvement in content creation processes.

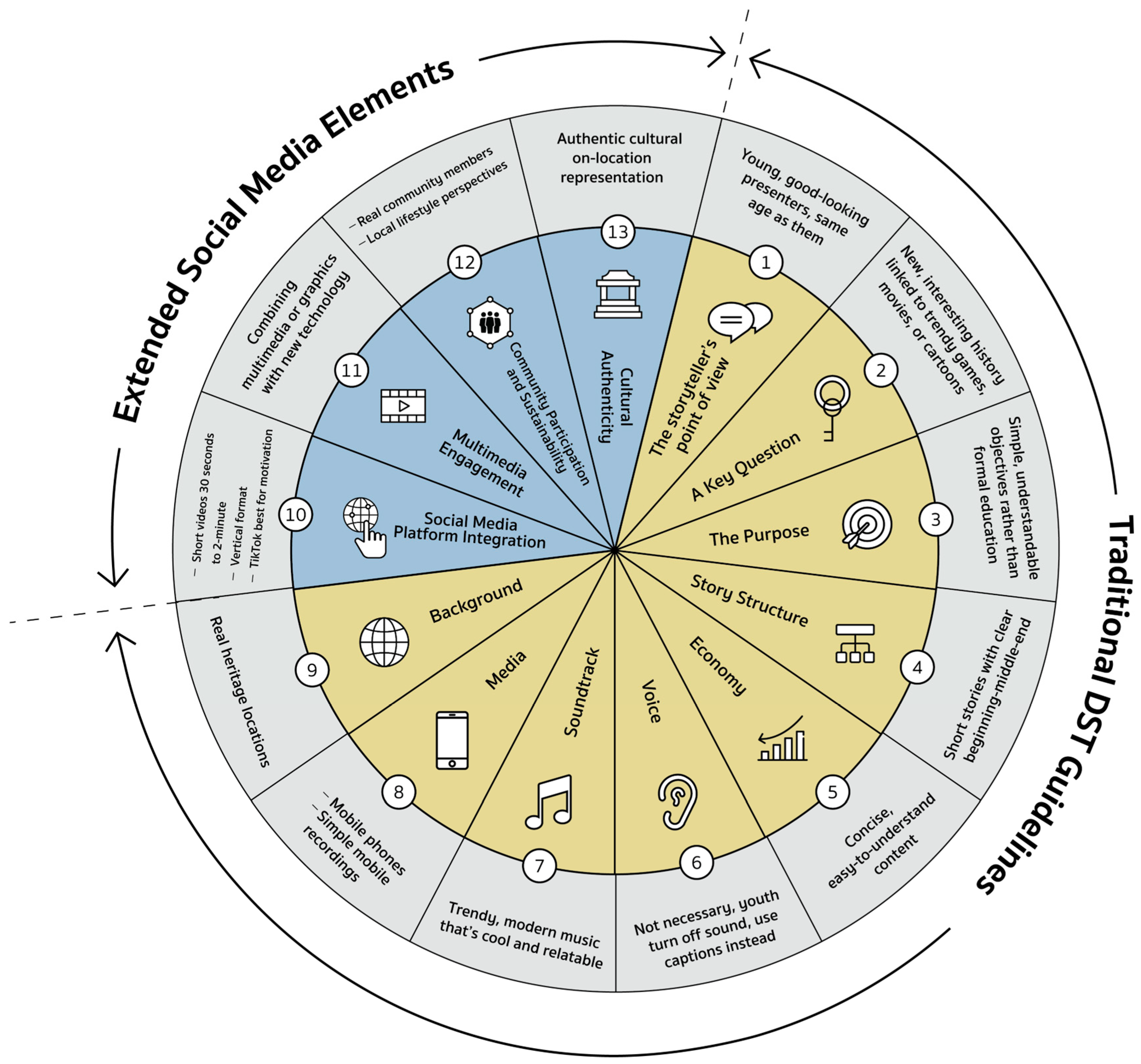

Table 5 presents the open-ended results for the 13 elements, and

Figure 5 illustrates the IDSM framework with results.

Open-ended responses were analyzed using content analysis conducted by three coders to ensure reliability and minimize researcher bias. The research team collaboratively categorized participant suggestions regarding ideal cultural heritage tourism video content according to the 13 IDSM framework elements.

5. Discussion

5.1. Gender Participation Patterns in Cultural Heritage Tourism

The observed gender distribution (63% female participants) provides valuable insight into contemporary cultural heritage tourism engagement patterns within Bangkok urban cultural heritage tourism contexts. While this study employed purposive sampling focused on age criteria rather than gender quotas, the resulting demographic composition reflects authentic cultural heritage tourism participation patterns, supporting the ecological validity of framework validation findings within genuine visitor contexts.

5.2. Video Content Type Preferences

As

Table 3 shows, the current study demonstrates a preference for authentic, simple mobile phone recordings among youth participants (64%). This finding validates the audience–expert discrepancy identified in previous research [

10], where experts recommended “hi-tech and professional devices” to attract youths, yet audiences consistently favored authenticity and simplicity in digital storytelling. The preference for realistic content production also aligns with social media research findings where youths preferred realistic over cinematic quality or highly stylized presentation across social media formats [

46,

53,

54].

The preference for authentic mobile phone recordings reflects fundamental shifts in digital authenticity perception and technical imperfections. This preference pattern aligns with social media platform algorithms that prioritize authentic user-generated content and parasocial relationship theory, whereby unpolished presentations facilitate stronger emotional connections and perceived relatability within cultural heritage tourism contexts.

5.3. Video Duration Preferences

Table 3 shows optimal engagement duration preferences of 31–60 s (48%) and 1–2 min (37%) among youth participants, with minimal interest in content exceeding 2 min (7%). The preference for a duration of 31–60 s aligns with digital storytelling economy principles established in previous research [

13,

14], which emphasizes the importance of achieving content delivery while maintaining narrative coherence but without audience overload. This preference pattern reflects contemporary social media consumption behaviors. Several studies confirm that effective cultural heritage tourism content needs to balance information density with consideration of optimal attention spans for youth engagement [

40,

41,

44].

The duration preferences reflect cognitive attention span constraints specific to the mobile social media consumption of digital native populations. This pattern aligns with established attention economy principles and cognitive load theory, where contemporary youths demonstrate reduced sustained attention capacities due to platform-conditioned rapid content switching behaviors.

5.4. Social Media Platform Influence on Cultural Heritage Tourism Motivation

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 reveal an interesting dissociation between social media platform usage frequency and motivational influence for cultural heritage tourism engagement. While Instagram demonstrates the highest usage frequency for watching videos (M = 4.05), TikTok emerges as the primary motivational driver for cultural heritage tourism (55% selection rate), followed by YouTube (52%) and Instagram (49%), with traditional media showing minimal selection rates. This finding corroborates previous research [

3,

10], where mobile devices and social media platforms were identified as primary preference channels while traditional media received consistently lower engagement scores. This underlines the paradigm shift from traditional tourism marketing channels to social media and confirms the necessity for cultural heritage tourism organizations to prioritize platform-specific social media content strategies focused on youth engagement patterns [

3,

40,

41,

45].

The dissociation between platform usage frequency and motivational influence reflects algorithmic content delivery mechanisms that prioritize discovery-oriented cultural experiences over routine consumption patterns. This divergence indicates that motivational influence operates independently from usage frequency.

5.5. Traditional Framework Validation

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the importance of the storyteller’s point of view (M = 4.24), with the open-ended responses emphasizing presenter demographics over narrative perspective. While traditional frameworks prioritize first-person storytelling to achieve a personal connection [

13], youth participants indicated that young narrators, or narrators of the same age as the target group (20 mentions), were more important to them than formal narrative structure. This finding suggests that peer identification supersedes traditional point-of-view considerations in social media contexts.

The elements “Purpose” (M = 4.05) and “Story structure” (M = 4.12) demonstrated robust results. The qualitative responses reveal a divergence from traditional digital storytelling, which focuses on complicated story structures [

4,

13,

16]. Youth participants emphasized the importance of simple and understandable purposes (24 mentions) and short narratives with engaging storylines (16 mentions), contrasting with formal cultural education approaches typically associated with long and complicated presentations [

4,

16].

The importance of the element “Economy” was strongly validated (M = 4.11), with quantitative and qualitative responses both emphasizing ease of understanding (22 mentions) and accurate information and concise presentation (8 mentions). This finding strongly supports traditional digital storytelling principles advocating for content brevity [

13,

15] while confirming social media consumption patterns [

46,

54].

The element “Key question” (M = 3.52) revealed the importance of adaptability for social media engagement, with youths emphasizing “new, interesting and unique question about history” (18 mentions) and trend integration with games, cartoons, superheroes, or Hollywood movies (22 mentions).

The element “Media” showed substantial agreement (M = 4.02), validating the importance of technical production standards while emphasizing mobile device optimization (38 mentions for “mobile phone”). The element “Background” (M = 3.94) confirmed the importance of filming in authentic locations (23 mentions), supporting changes in media preference toward mobile phones [

46,

53,

54].

The element “Voice” (M = 3.58) suggested that traditional frameworks lack critical platform adaptations. The open-ended responses indicated that voice narration is unnecessary as users turn the volume off when using their mobile phone (20 mentions). This finding highlights the necessity of including captions or graphic storytelling approaches to better reflect mobile consumption behaviors [

40,

64].

“Soundtrack” (M = 3.24) demonstrated neutral responses, with specific requirements for trendy, contemporary, new, and relatable music (15 mentions). While traditional frameworks emphasize the support function of soundtracks and their ability to promote emotions [

13], youth participants prioritized subtitles, graphics, cultural relevance, and contemporary content over narrative enhancement. This indicates a significant shift in audio preferences [

54,

59,

64].

In brief, the results show that traditional digital storytelling principles maintain theoretical relevance when adapted for social media platforms and youth engagement. However, successful implementation requires significant modifications to be made in order to address platform-specific social media consumption patterns, particularly in terms of mobile phone-first design, caption dependency, and contemporary cultural integration.

5.6. Four New IDSM Elements Focused on Social Media

The element “Social media platform integration” suggested a strong preference for mobile devices (M = 3.95) and short-form content (31–60 s: 48%). The motivational influence hierarchy—TikTok (55%), YouTube (52%), Instagram (49%)—confirms the platform-specific engagement mechanisms identified in the systematic review. Open-ended responses emphasize short-form social media content with optimal duration 30 s to 2 min (28 mentions), directly supporting the cluster findings on social media technology trends, particularly on the effectiveness of short-form videos and platform-optimized content strategies [

46,

47,

53].

“Cultural authenticity” showed the highest score of all elements (M = 4.54), with 34 mentions in the open-ended responses. This strongly validates the importance of cultural authenticity, supporting previous studies that have pointed toward the importance of community validation and heritage preservation [

22,

51,

52]. The emphasis on authenticity over production value contradicts industry assumptions about youth preferences for embellished content, supporting the community-based stewardship approaches documented in the conservation and sustainability cluster.

“Community participation and sustainability” (M = 4.24) yielded 23 mentions of real community member participation, validating the cluster findings on community participation and sustainability. This confirms the effectiveness of co-created content development and community-driven storytelling [

6,

50]. The preference for local community involvement over professional presenters aligns with the user-generated content and collaborative digital storytelling trends identified in the DST-SM systematic analysis.

“Multimedia engagement” (M = 3.74) suggested cautious optimism about technological innovation, as identified in the technology integration cluster. This finding validates the importance of multimedia integration frameworks while confirming that technology must serve narrative purposes rather than providing novelty, consistent with trends in immersive technology [

32,

55,

56,

57].

These findings demonstrate that effective cultural heritage tourism digital storytelling frameworks must integrate traditional narrative principles with platform-specific social media requirements. The empirical validation of the four new elements confirms the theoretical gaps identified through bibliometric analysis and provides a foundation for evidence-based guidelines for cultural heritage tourism practitioners seeking to engage youth audiences through contemporary digital platforms. The convergence between quantitative framework validation and qualitative preference insights provides robust support for the IDSM framework’s practical implementation in cultural heritage tourism contexts.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate how youths aged 18–25 perceive and prioritize the 13 elements of the IDSM framework in social media-enhanced cultural heritage tourism contexts and to explore their specific preferences for cultural heritage tourism video content through open-ended insights. The research sought to address critical gaps in digital storytelling frameworks in cultural heritage tourism applications, which are inadequate to meet the requirements of contemporary social media platforms and youth engagement.

The results revealed several key findings that reshape our understanding of effective digital storytelling for youth audiences. Cultural authenticity emerged as the paramount consideration (M = 4.54), challenging industry assumptions about youth preferences for embellished content and establishing heritage accuracy as fundamental for engagement. Traditional storytelling elements demonstrated sustained relevance when adapted for social media contexts, with story structure (M = 4.12), content economy (M = 4.11), and storyteller demographics (M = 4.24) achieving strong validation. However, critical platform adaptations were identified, particularly the necessity for caption-dependent storytelling due to mobile consumption patterns whereby youths tend to turn the sound off when using their mobile phones. The four new IDSM elements demonstrated varying acceptance levels, with the importance of community participation achieving joint-strongest validation, while technological integration received more cautious endorsement. Youth preferences emphasized authentic mobile-phone-quality recordings (64%) over professional production and optimal video durations of 31–60 s (48%) and confirmed TikTok’s emergence as the primary motivational platform (55%), despite moderate usage frequency.

This exploratory study contributes to the initial development and preliminary validation of the IDSM framework for social media applications in cultural heritage tourism contexts. The exploratory findings establish preliminary evidence-based guidelines for cultural heritage tourism practitioners operating in comparable metropolitan contexts with similar demographic characteristics. The IDSM framework represents an initial theoretical synthesis requiring broader validation across diverse geographic, stakeholder, and cultural settings. The framework also provides practical value for organizations seeking to enhance youth engagement with cultural heritage through authentic, community-driven digital storytelling approaches within this study’s specified parameters.

Regarding study limitations, this study was conducted exclusively with 100 youth participants at cultural heritage tourism sites around Rattanakosin Island, Bangkok, Thailand, a historically significant area encompassing the capital’s old city and multiple heritage sites. While this location ensured participants demonstrated active engagement with cultural heritage tourism, the geographic constraint and urban context significantly limit generalizability to rural populations, smaller urban centers, or international youth demographics. Moreover, the gender distribution of 63% female participants may have introduced systematic bias affecting preference patterns and platform selections. Cultural heritage tourism preferences, social media consumption behaviors, and digital storytelling preferences may vary substantially across different regional contexts, socioeconomic backgrounds, and digital infrastructure levels. Therefore, findings should be interpreted as applicable primarily to urban youth populations actively engaged in cultural heritage tourism within similar metropolitan heritage contexts, requiring further validation for broader demographic and geographic applicability. Lastly, the research employed an exploratory on-site intercept survey design with purposive sampling (N = 100), which was not intended to achieve statistical representativeness of broader youth populations. While this methodological approach effectively captures authentic participant experiences within cultural heritage tourism contexts, it inherently limits generalizability beyond the specific demographic and geographic parameters studied.

Regarding implications for stakeholders, cultural heritage tourism organizations and museums might implement the IDSM framework by featuring young, relatable presenters in their social media materials and developing concise narratives within a duration of 31–60 s (or not more than 2 min). Content must use caption-dependent formats. TikTok and YouTube should be prioritized for maximum youth engagement. Organizations should implement accessible virtual reality or augmented reality tools when appropriate. Content should feature real community members. Museums should promote cultural authenticity, working to ensure heritage accuracy and maintaining youth appeal through the use of authentic mobile phone recordings.

Social media content creators and digital marketers could apply the framework by incorporating trendy games, cartoons, or superheroes into historical narratives. Content should emphasize authentic on-location filming using mobile devices within a duration of 31–60 s, acknowledging TikTok’s emergence as the primary motivational platform. User-generated content should be used to facilitate community participation. Content should maintain engaging, caption-dependent presentation methods for mobile phone consumption, acknowledging preference patterns.

Technology developers and platform designers should work toward user-friendly interfaces with vertical-format video and support mobile-prioritized content creation. Platforms should feature caption integration and community collaboration. Developers should work toward accessible multimedia integration and allow community creators to incorporate virtual reality or augmented reality elements without technical expertise. However, all tools should prioritize simplified, authentic content creation over technical complexity.