Architecture and Armour in Heritage Discourse: Form, Function, and Symbolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Scope and Theoretical Framework

1.2. Heritage Context and Contemporary Relevance

1.3. Towards a New Comparative Reading

1.4. Clarifying the Central Argument

1.5. Limits and Points of Contact

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Methodological Aim

2.2. Empirical Background and Craft-Based Experience

2.2.1. Experimental Documentation and Reconstruction

2.2.2. Stone Carving and Intergenerational Craft Knowledge

2.2.3. Field-Based Heritage Practice: Ambulanța Pentru Monumente (Bihor)

2.3. Heritage Science Relevance

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Framework: Reading Across Categories

- Form and Structure—How mass, rhythm, and articulation define both a cathedral’s envelope and a cuirass’s silhouette.

- Ornament and Surface—How tracery, engraving, or fluting transformed mere function into meaning, echoing the structural rhythm and surface logic of Gothic vaults and late-medieval plate armour [21].

- Function and Use—How weight, ergonomics, and defensive logic govern the shaping of both space and steel.

- Symbolic Meaning—How each artefact—whether wall or helm—encodes authority, devotion, and identity.

3.2. The Romanesque Synthesis: Armour and Architecture in Convergence

3.3. Crac Des Chevaliers and the Knight as a Fortified Body

3.4. From Romanesque Mass to Gothic Modulation: Parallel Evolutions in Architecture and Armour

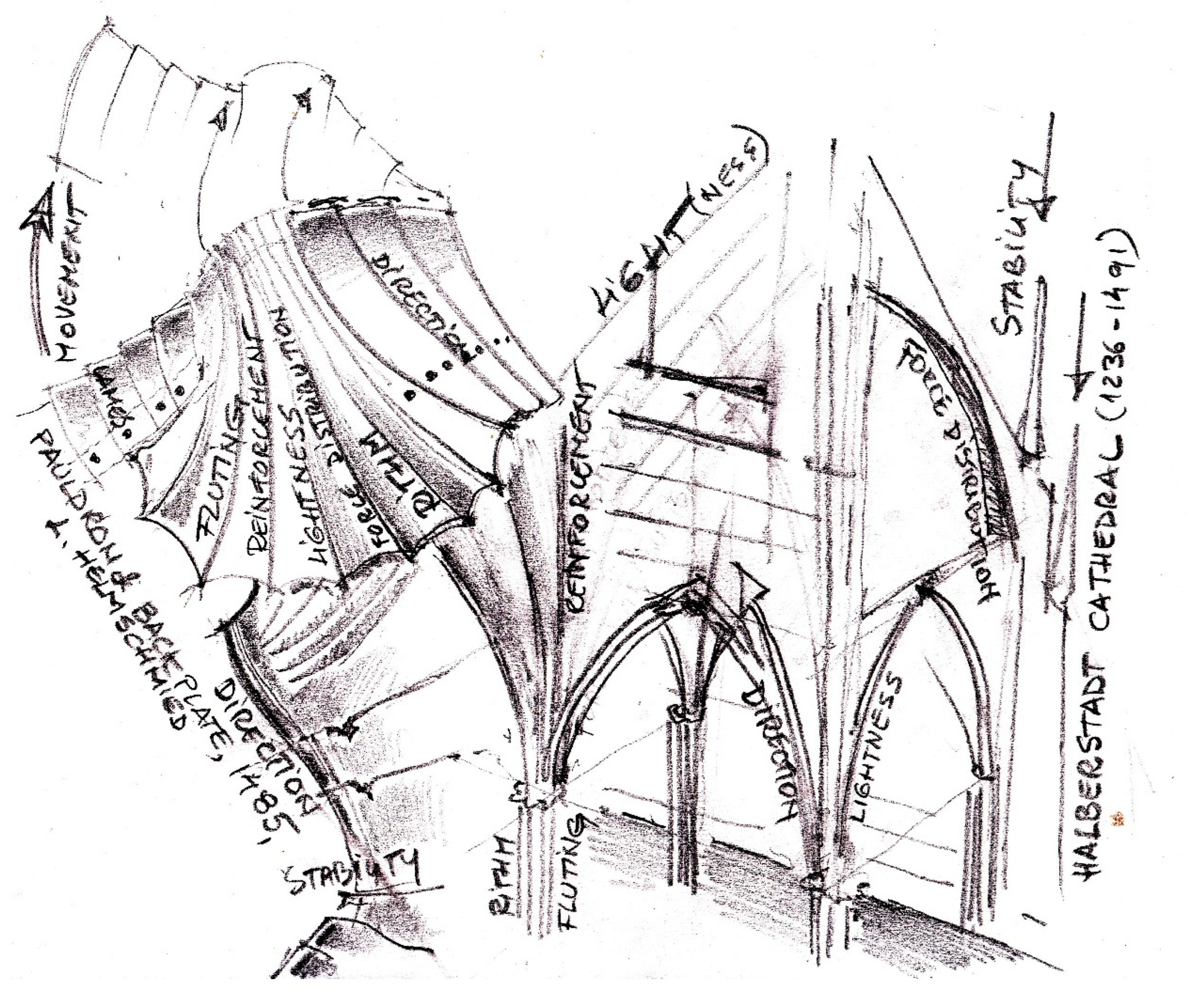

3.5. The Gothic Peak: A Mobile Cathedral for the Body

3.6. Renaissance Symmetries: Classical Revival in Armour and Architecture

3.7. Memorialisation in Stone and Steel

3.8. Ornament, Structure, and Symbol: Formal Analogies

4. Discussion

4.1. Beyond Rupture: Continuity Between Gothic and Renaissance

4.2. Mobility and Exchange: Condottieri, Reputations, and Cross-Border Gear

4.3. Romanian Principalities: Peripheral Evidence and Central Questions

4.4. Marginal Historiography and the Need for Recovery

4.5. Embodied Knowledge and the Logic of Proportion

4.6. The Scabbard as Façade: Ornament, Architecture, and Symbolic Power

4.7. Armour as Architecture in Motion

4.8. Postscript: Absence as Argument—The Romanian Case

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Meaning in Western Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, D.; Reynolds, W. Carolingian Cavalryman AD 768–987; Warrior Series; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Toman, R. Romanesque: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting; Konemann: Koln, Germany, 1997; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Lepage, J.D.G.G. (Ed.) Castles and Fortifed Cities of Medieval Europe: An Illustrated History; McFarland: Jefferson, NC, USA, 2002; p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A. The Knight and the Blast Furnace: A History of the Metallurgy of Armour in the Middle Ages & the Early Modern Period; Brill Book Archive Part 1; BRILL: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 9004124985. [Google Scholar]

- Kulpiński, J. Defensive Strongholds and Fortified Castles in Poland—From the Art of Fortifications to Tourist Attractions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, I.V.; Mourão, P.J.R.; Albuquerque, H. Do Medieval Castles Drive Heritage-Based Development in Low-Density Areas? Heritage 2025, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virilio, P. Bunker Archaeology; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Arnheim, R. Art and Visual Perception, 2nd rev. exp. ed.; Reprint 2020 ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Baxandall, M. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style, 2nd ed.; 28. print; Oxford Paperbacks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1988; p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Kubler, G. The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Riegl, A. Stilfragen: Grundlegungen zu Einer Geschichte der Ornamentik; Verlag von Georg Siemens: Berlin, Germany, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Viollet-le-Duc, E.-E.; Kurtz, J.-P. Dictionnaire Raisonné de L’architecture Française du XIème au XVIème Siècle; Reproduction en fac-similé; Books on Demand: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, E. Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism; Art history; Meridian: New York, NY, USA, 1974; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- Giedion, S. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition; The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures for 1938–1939; 5., rev. enlarged ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; p. 897. [Google Scholar]

- Capwell, T. Armour of the English Knight 1400–1450; Thomas Del Mar Ltd.: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Toman, R. The Master Builders and the Cathedral Workshop. In Gothic: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting; Könemann: Cologne, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S.J. Masterpieces of European Arms and Armour in the Wallace Collection; Capwell, T., Ed.; Paul Holberton Publishing: London, UK, 2011; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, C. European Armour: C.1660–c.1700; New Impression; B.T. Batsford: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Capwell, T. Armour of the English Knight 1450–1500; Thomas Del Mar Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- Capwell, T. Armour of the English Knight. Continental Armour in England 1435–1500; Great Britain; Thomas Del Mar Ltd.: London, UK, 2022; p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, D. Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050–1350. Western Europe and the Crusader States; Greenhill Books: London, UK; Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, PA, USA, 1999; p. 636. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, D. Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050–1350: Islam, Eastern Europe and Asia, rev. and updated ed.; Greenhill Books: London, UK; Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, PA, USA, 1999; p. 576. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, R. (Ed.) Medieval Arms and Armour: A Sourcebook. Volume I: The Fourteenth Century; The Boydell Press: Martlesham, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, R. Medieval Arms & Armour: A Sourcebook. Volume III: 1450–1500; Armour and weapons; Boydell & Brewer: Woodbridge, UK; Rochester, NY, USA, 2024; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. Foundational Description of the Art of Fencing: The 1570 Treatise of Joachim Meyer; Reading Edition; Chidester, M., Ed.; HEMA Bookshelf: Somerville, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chidester, M. The Flower of Battle: MS M 383; HEMA Bookshelf: Somerville, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Anglo, S. The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2000; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, J. The Stone Skeleton: Structural Engineering of Masonry Architecture, 1st paperback ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Bérard, E.; Dillmann, P.; Renaudeau, O.; Verna, C.; Toureille, V. Fabrication of a suit of armour at the end of Middle Ages: An extensive archaeometallurgical characterization of the armour of Laval. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 53, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, T.; Kraner, J. Thickness Mapping of Body Armour: A Comparative Study of Eight Breastplates from the National Museum of Slovenia. Fasc. Archaeol. Hist. 2019, 32, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wang, H. Digital Twin Research on Masonry–Timber Architectural Heritage Pathology Cracks Using 3D Laser Scanning and Deep Learning Model. Buildings 2024, 14, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimkhil, M.H.; Shen, X.; Barati, K.; Wang, C.C. Dynamic Progress Monitoring of Masonry Construction through Mobile SLAM Mapping and As-Built Modeling. Buildings 2023, 13, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aparicio, L.J.; Santamaría-Maestro, R.; Sanz-Honrado, P.; Villanueva-Llauradó, P.; Aira-Zunzunegui, J.R.; González-Aguilera, D. A Holistic Solution for Supporting the Diagnosis of Historic Constructions from 3D Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley-Smith, J.S.C. The Crusades: A History, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2005; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, R. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change, 950–1350; 1. Princeton Paperback Print; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994; p. 432. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, D.; Hook, C. Knight Hospitaller (1): 1100–1306; Reprinted; Men-at-Arms Series; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, D.; Hook, A. (Eds.) Crusader Castles in the Holy Land, 1192–1302; Fortress Series; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, D.; Hook, A. Crusader Castles in the Holy Land, 1097–1192; Fortress Series; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, D. Knight of Outremer: AD 1187–1344; Reprinted; Elite Series; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gravett, C. English Medieval Knight 1200–1300; Warrior Series; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gravett, C.; McBride, A. (Eds.) Knights at Tournament; Osprey Military Elite Series; Osprey Publishing: London, UK, 1988; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, H.J.; Reynolds, W. Knight Templar: 1120–1312; Warrior Series; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Sugerus; Panofsky, E.; Panofsky-Soergel, G. Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and its Art Treasures, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, H. Crusader Castles, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, J.D.; Metropolitan Museum of Art; Museo de la Alhambra (Eds.) Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain; Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle, D. El Cid and the Reconquista 1050–1492; Osprey Military Men-at-Arms Series; Reprint; Osprey Publishing: London, UK, 1988; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Wendland, D.; Gielen, M.; Korensky, V. Towards the Gothic: Design and Construction of the 12th Century Vaults in Notre-Dame in Paris, and Possible Origins. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2025, 19, 1231–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobbik, E.; Krähling, J. A Methodological Approach and Geometry-Based Typology of Late-Gothic Net Vaults’ Rib Systems. Presented on Case Studies from Historic Hungary. Nexus Netw. J. 2025, 27, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toman, R.; Bednorz, A. Gothic: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting; Könemann: Köln, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, P.; Crossley, P. Gothic Architecture; 2nd revised; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2001; p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Berge Armures: Première Vente—Le Musée Fantastique de Karsten Klingbeil; Bruxelles. 2011. Available online: https://cdn.drouot.com/d/catalogue?path=berge/13122011-armures/BergeArmures-13122011-BD.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Oakeshott, R.E. A Knight and his Armor, 2nd ed.; Dufour Editions: Chester Springs, PA, USA, 1999; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Capwell, T. Armour and the Knight in Life and Afterlife; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 9 June 2020; Available online: https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/article/tobias-capwells-lecture-armour-and-the-knight-in-life-and-afterlife (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Rusu, A.A. Arme și armuri medievale în Transilvania (Medieval Arms and Armour in Transylvania). In Investigări ale Culturii Materiale Medievale din Transilvania (Studies on Medieval Material Culture in Transylvania); Editura Mega: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elizalde, R.R. Beauvais Cathedral: The Ambition, Collapse and Legacy of Gothic Engineering. Heritage 2025, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toman, R. The Art of the Italian Renaissance: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Drawing, revised ed.; Art, Architecture, Design; H.F. Ullmann: Potsdam, Germany, 2015; p. 464. Available online: https://archive.org/details/isbn_9783833146749/mode/2up (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Hunt, L. (Ed.) The Family Romance of the French Revolution; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, C.; Ghiara, G.; De Montis, P.; Piccardo, P.; Gatta, G.D.; Trasatti, S.P. Archaeometallurgical Analyses on Two Renaissance Swords from the “Luigi Marzoli” Museum in Brescia: Manufacturing and Provenance. Heritage 2021, 4, 1269–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, P. The master of incavatura: Faustino Ghelfo of Brescia and the decoration of blades with multiple niches. J. Arms Armour Soc. 2021, 23, 340–352. [Google Scholar]

- Gravett, C. Tudor Knight; Warrior Series; Osprey Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, A.A. Ctitori şi Biserici din Ţara Haţegului Până la 1700 (Founders and Churches of the Hațeg Region up to 1700); Editura Muzeului Sătmărean: Satu Mare, Romania, 1997; p. 386. [Google Scholar]

- Terjanian, P. The Last Knight. The Art, Armor, and Ambition of Maximilian I; Illustrated; Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtert, K. Portraits of the City: Representing Urban Space in Later Medieval and Early Modern Europe; Studies in European Urban History (1100–1800); Brepols Publishers: Turnhout, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Southwick, L. The Great Helm in England. Arms Armour J. R. Armouries 2006, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăguț, V. Arta Gotică în România (Gothic Art in Romania); Meridiane: București, Romania, 1979; p. 397. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, A.A. Sculptura gotică din Transilvania (Gothic Sculpture in Transylvania). In Arhitectura Religioasă Medievală din Transilvania; Editura Muzeului Sătmărean: Satu Mare, Romania, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, A.A. Arhitectura Religioasă Medievală din Transilvania (The Medieval Religious Architecture of Transylvania); Szőcs, P.L., Ed.; Editura Muzeului Sătmărean: Satu Mare, Romania, 2012; p. 392. [Google Scholar]

- Meer, M. Heraldry in Urban Society: Visual Culture and Communication in Late Medieval England and Germany; Oxford Studies in Medieval European History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M.C. Pisano, Nicola and Giovanni. In Research Starters Home. 2022. Available online: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/biography/nicola-pisano-and-giovanni-pisano (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Mallett, M. Signori e Mercenari: La Guerra Nell’italia del Rinascimento; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2013; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Neagoe, C. Military organization of Wallachia from the first Basarabs until the beginning of the 16th century. Ann. D’univ. “Valahia” Târgovişte Sect. D’archéol. D’hist. 2019, 21, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraner, J.; Lazar, T.; Mlinar, M.; Burja, J. Metal Artefacts and Remains of Armour from Kozlov Rob Castle: Metallurgical Analyses as a Tool for Identification and Interpretation of Fragmentary Archaeological Finds. Heritage 2023, 6, 4653–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M.; Behrens-Abouseif, D. (Eds.) The Arts of the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria: Evolution and Impact (Mamluk Studies); Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht unipress GmbH: Göttingen, Germany, 2012; p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, A.A. Castelul și Spada. Cultura Materială a Elitelor din Transilvania în Evul Mediu Târziu (The Castle and the Sword. The Material Culture of the Elites in Transylvania during the Late Middle Ages); Editura Mega: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2019; p. 920. [Google Scholar]

- Vlădescu, C.M. Types of Bladed Weapons and Armour Used by Romanian Forces in the Second Half of the 15th Century. In Studies and Materials of Museography and Military History; Muzeul Militar Central: Bucharest, Romania, 1973; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Capwell, T. Reconstructing the Fifteenth-Century Armour of the Black Prince. In Royal Armouries Yearbook; Royal Armouries Museum: Leeds, England, 2008; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, L.B.; Rykwert, J.; Alberti, L.B. On the Art of Building: In Ten Books; 7. print; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1991; p. 442. [Google Scholar]

- Leoni, T.; Mele, G. Flowers of Battle: Historical Overview and the Getty Manuscript; Annotated; Freelance Academy Press, Inc.: Wheaton, IL, USA, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Forgeng, J.L. The Medieval Art of Swordsmanship: Royal Armouries MS I.33; Royal Armouries: Leeds, UK, 2018; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Serlio, S. Sebastiano Serlio on Architecture; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 1996; Volume I–V. [Google Scholar]

- Rudler, R. François 1er: Bâtisseur de la Monarchie; Calmann-Lévy: Paris, France, 1980; p. 350. [Google Scholar]

- Armor Experts React to Famous Knight from the 100 Years War—With Dr. Tobias Capwell [Internet]. Schola Gladiatoria (YouTube Channel). 2025. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3ob3RLoiSQ&ab_channel=scholagladiatoria (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Gheorghiu, T.O.; Bica, S.M. Restituții: Orașe la începuturile Evului Mediu românesc (Restitutions: Fortified Towns at the Beginning of the Romanian Middle Ages); Cărțile Arhitext; Editura Fundației Arhitext Design: Bucharest, Romania, 2015; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Niedermaier, P. Habitatul Medieval în Transilvania (Medieval Habitation in Transylvania); Contribuţii privind istoria oraşelor/Academia Română/Comisia de Istorie a Oraşelor din România (Contributions to the History of Towns/Romanian Academy/Commission for the History of Towns in Romania); Editura Academiei Române: Bucharest, Romania, 2012; p. 380. [Google Scholar]

- Costăchel, S.; Panaitescu, P. Obștea sătească în Țara Românească și Moldova (The Peasant Community in Wallachia and Moldavia). In Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medievală; Editura Academiei Republicii Populare Române: Bucharest, Romania, 1956; Volume I, pp. 63–123. [Google Scholar]

- Duby, G. Rural Economy and Country Life in the Medieval West; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998; p. 600. [Google Scholar]

- Ciachir, D. Biblioteca Uitată de la Mediaș. Turnul Sfatului. (The Forgotten Library of Mediaș. The Council Tower). Available online: https://www.turnulsfatului.ro/2023/02/05/biblioteca-uitata-de-la-medias-manuscrise-si-incunabule-descoperite-intr-o-biserica-199051 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Janowski, A. Archaeologist in the Archive a Turning Point in the Study of Late-medieval Helmets in Western Pomerania. Fasc. Archaeol. Hist. 2020, 33, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaida, E. (Ed.) Ambulanța Pentru Monumente: Patrimoniul Salvat împreună (Ambulance for Monuments: Saving Heritage Together); Asociația Monumentum: Sibiu, Romania, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Romanesque | Gothic | Renaissance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Form and Structure | - Semicircular arches, massive volumes (Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire) - Compact keeps - Mail hauberks, cylindrical spangenhelms | - Ribbed vaults, pointed arches, vertical thrust (Chartres, Halberstadt) - Stepped bastions (Crac des Chevaliers) - Fluted cuirasses, “hounskull” helmets | - Classical symmetry (Palazzo Rucellai, San Lorenzo) - Rusticated urban fortresses (Palazzo Medici) - Smooth Milanese plate with Roman details |

| Ornament and Surface | - Symbolic relief sculpture (Moissac) - Simple engraved crosses on arms and shields | - Tracery, rose windows, sculptural programs (Notre Dame, Ulm Minster) - Etched floral or heraldic motifs - Decorative fluting and articulated fasteners | - Friezes, triglyphs, classical orders - Engraved cuirasses with vegetal or mythological themes - Shields with medallions of Hercules or Mars |

| Function and Use | - Passive fortification through mass - Restrictive protection for frontal shock combat | - Fully articulated plate suits, optimized for movement (e.g., German Gothic harness, c. 1480) - Dual-purpose sacred/military spaces (Marienburg Castle) | - Ceremonial and parade armour (e.g., François I, Maximilian I) - Civic buildings for prestige and display (Piazza della Signoria) |

| Symbolic Meaning | - Sacred enclosure, divine protection - The knight as guardian of the faith (Roland, Santiago) | - Transcendence through light and elevation - Chivalric armour as visual ethics code and noble identity marker | - Humanist ideal: the knight as vir virtutis - Architecture and armour as rationalized expressions of civic virtue and status |

| Architectural Element | Armorial Element | Shared Function/Logic |

|---|---|---|

| Vault rib | Fluting (cuirass, greaves) | Force distribution, rhythm, visual articulation |

| Buttress (flying or solid) | Shoulder/hip articulation | Lateral stabilization, redirection of load |

| Vertical pier/solid buttress | Leather straps, internal braces | Hidden support, structural anchoring, mass modulation |

| Windows/tracery | Etched decoration | Iconographic surface, symbolic inscription |

| Rose window (Romanesque/Gothic) | Besague/Rondel (axillary disc) | Circular articulation between major volumes; symbolic and structural transition |

| Portal tympanum | Decorated scabbard | Narrative display, threshold symbolism |

| Spire/pinnacle | Helmet crest | Vertical identity marker, status display |

| Modular façade panels | Armour plates (torso, limbs) | Segmentation, protection, hierarchy |

| Mouldings/engaged columns | Spaulders/vambraces | Layering, movement articulation, decorative framing |

| Polychrome finishes | Gilding enamel | Visual contrast, symbolic colouring |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pescaru, A.H.; Zsak, I.-G.; Onescu, I. Architecture and Armour in Heritage Discourse: Form, Function, and Symbolism. Heritage 2025, 8, 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090382

Pescaru AH, Zsak I-G, Onescu I. Architecture and Armour in Heritage Discourse: Form, Function, and Symbolism. Heritage. 2025; 8(9):382. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090382

Chicago/Turabian StylePescaru, Adrian Horațiu, Ivett-Greta Zsak, and Iasmina Onescu. 2025. "Architecture and Armour in Heritage Discourse: Form, Function, and Symbolism" Heritage 8, no. 9: 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090382

APA StylePescaru, A. H., Zsak, I.-G., & Onescu, I. (2025). Architecture and Armour in Heritage Discourse: Form, Function, and Symbolism. Heritage, 8(9), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090382