1. Introduction: Rediscovering the Mashrabiya in Islamic Public Architecture

A distinctive element of traditional Islamic architecture, the mashrabiya is a traditional projecting window enclosed with intricately carved wooden latticework, serving as both a functional and decorative element. It was initially designed to provide both privacy and thermal comfort through passive cooling and light control [

1]. Its importance in public building architecture has yet to be studied, despite its well-documented application in domestic structures.

The diverse purposes and variants of mashrabiya in Islamic public buildings, particularly mosques, madrasas, caravanserais, and hospitals, across various historical and geographic settings, are examined in this study. In particular, this research, through the analysis of selected case studies related to public buildings, aims to investigate the extent to which regional characteristics have influenced the shape, material, and function of the mashrabiya. The applied methodology, based on a comparative analysis of selected case studies among four identified categories of public buildings in traditional Islamic architecture, demonstrates the important cultural meaning of the mashrabiya and its potential application in contemporary sustainable design. Ultimately, the present study aims to provide a thorough understanding of the symbolic and functional role played by the mashrabiya in its traditional context, while also offering insight into its integration in contemporary design.

While the mashrabiya’s aesthetic qualities have received attention in previous scholarship, its multifaceted role in public architecture—particularly in non-residential contexts—remains underexamined. This research aims to fill that gap by providing a comparative lens across various typologies, periods, and regions, thereby contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the significance of this architectural element.

2. Literature Review: Origins, Functions, and Contemporary Reinterpretations of the Mashrabiya

A substantial body of literature exists on the subject, addressing the origins of the mashrabiya, as well as its functions, construction techniques, materials, and potential applications.

As widely documented, the mashrabiya is defined as a typical element of Islamic architecture, initially designed for evaporative water cooling [

2], that later evolved into a projecting window for discreet observation of public spaces [

3]. This architectural feature, due to its widespread adoption throughout the Arab world [

4,

5,

6], has acquired various regional names (such as Rawshan in Saudi Arabia, Aggasi in Bahrain, Jali in India, and Takhrima in Yemen), yet “mashrabiya” remains the most prevalent name. Its etymological root, “mashraba,” derives from the verb “yashrab,” meaning “to drink.” Alternatively, “mashrabiya” is also interpreted as a derivative of “mashrafiya,” meaning “to overlook from an elevated position” [

7]. Some scholars trace the earliest mashrabiya examples to pre-Islamic Egypt [

8], suggesting that its dissemination across the Islamic world, particularly in the Arab regions, was facilitated by the technical expertise and woodworking traditions of Egyptian artisans [

2,

3].

While the mashrabiya’s consistent presence and functional role in traditional architecture are undeniable [

9,

10], the advent of the Industrial Revolution and the widespread use of electricity (for lighting and artificial cooling) significantly diminished its use and application [

11,

12] However, recent years have witnessed a revival of the mashrabiya’s application, because of a new interest aimed at rediscovering and reevaluating Islamic cultural roots, including in architecture [

1,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], coupled with the contemporary sustainability goals. A recent survey [

4] indicates that the majority of Saudi Arabian citizens are in favor of reintroducing the mashrabiya, citing sustainability and cultural heritage as primary motivators [

13,

17]. Nevertheless, the study highlights the high costs associated with its fabrication (materials and skilled labor) as a significant barrier to its implementation.

Furthermore, there is an ongoing debate regarding the reintroduction and reinterpretation of the mashrabiya in modern constructions [

11,

18]. According to the researcher, beyond purely aesthetic considerations (which require a separate discussion regarding the patterns adopted), maintaining the mashrabiya’s original function related to sustainability is crucial [

19]. In light of this interpretation, the mashrabiya shall not merely serve as an aesthetic link to the past but, when integrated with modern technologies, contribute to the building’s sustainability [

5,

6,

9,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The recent and renewed interest in traditional architecture, as a tangible form of cultural identity, has also led to the re-evaluation of the mashrabiya, which has been the subject of several studies focused on analyzing possible reinterpretations in a modern context. Among these studies, Alazhari [

27] aimed to create a digital archive, cataloging existing mashrabiya typologies for potential use through three-dimensional printing technologies [

1,

18,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

A more recent work [

32] sought to identify the mathematical variables and rules that govern the creation of the mashrabiya’s intricate patterns. In this case, the digital archive, created collaboratively with artisans, aims to preserve the cultural significance of this architectural feature [

33], ultimately suggesting potential future applications through contemporary examples. Even if they employ different methods, these studies all aim to preserve an important aspect of Islamic architectural heritage. The former attempts to create a digital catalog for the fabrication of mashrabiyas via 3D printing [

34,

35], while the latter provides an open-source database of examples, focusing on morphological and constructional aspects. This latter study also cites examples of the mashrabiya being reinterpreted [

36] and utilized in iconic projects [

12], leveraging the advantages of home automation [

35,

37]. However, while the majority of the latest studies focus on the potential application of the mashrabiya in implementing new technologies, there is currently no comprehensive study specifically aimed at examining the functions of the mashrabiya in historical public buildings. This exercise of exploring the lesser-explored use of the mashrabiya in historical public buildings does not aim to be exhaustive but, rather, seeks to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of architectural heritage. Collectively, these studies underscore that the mashrabiya embodies a multifaceted significance, encompassing symbolic, tectonic, and functional dimensions, each explored through diverse methodological and disciplinary lenses. This body of research highlights not only its role as a climatic and spatial device but also its value as a cultural artifact and an expression of craftsmanship. Recognizing this layered importance provides a foundation for the present study, which builds upon these insights to explore how the mashrabiya’s heritage values can be preserved, reinterpreted, and integrated within contemporary sustainable architecture.

Research Questions

Although the available literature offers an insightful background on the evolution over time, typological differences, and modern-day reinterpretations of the mashrabiya, the majority of the work is concerned mainly with its implementation in residential architecture or as a decorative feature in modern structures. Even though there are now attempts to digitalize its morphological characteristics and investigate new fabrication methods for it, the implementation of mashrabiyas in historic public structures continues to be largely unstudied. What is more pertinent is the fact that public structures—including mosques, madrasas, bimaristans, and caravanserais—were instrumental in defining Islamic urban spaces and civic life. A more refined examination of how mashrabiyas operated within such spheres can unveil not just their climatic and societal functions but also how the symbolic and typological differences extended over regions. The current work addresses such a lacuna by concentrating on the traditional implementation of the mashrabiya in public Islamic architecture so as to analyze how regional qualities affected its design, materiality, and purpose in various building types as well as geographical locations.

To what extent have regional characteristics influenced the design, materials, and function of the mashrabiya in Islamic public buildings?

Islamic architecture is defined by a rich vocabulary of decorative, functional, and compositional elements, among which the mashrabiya stands out as one of the most representative.

At the height of its territorial expansion, stretching from Southern Europe to Asia via North Africa, the Islamic world developed a coherent architectural language. This language incorporated specific design features that played a key role in fostering a shared cultural and religious identity amid diverse populations.

Among these elements, the mashrabiya responded particularly well to a range of needs common across the Islamic world. It functioned as a passive climate control device [

38], regulating heat and light in interior spaces exposed to intense temperatures, as well as serving as a privacy screen, in line with cultural values of modesty. At the same time, it served as a distinctive decorative motif, becoming a symbol of identity and continuity within the Islamic architectural tradition. In particular, the recent resurgence of the mashrabiya in architectural practice follows a long genealogy of re-reading precedents going back decades. The best known among these early sources was probably Jean Nouvel’s Paris Institut du Monde Arabe of 1987, in which a kinesthetic system of mechanical apertures, derived from classical mashrabiya geometries, was joined by carefully crafted lacelike interior screens of stone. This building shows how elements of traditional Islamic design may be programmatically re-invented in contemporary applications, combining cultural inheritance and the latest technology. Citing such prototypes underpins the idea of vernacular devices integrated into the practice of modern architecture with a long-standing history. Herein lies a worthwhile lesson about sustainable and culturally sympathetic design now and in the future.

This study is therefore motivated by the limited availability of similar research in public buildings, and by the aim of contributing to a broader understanding of the mashrabiya, thereby supporting its thoughtful integration into contemporary sustainable architecture.

While the mashrabiya is more traditionally related to domestic Islamic architecture, its occurrence and adoption within public building types warrants further consideration. No available literature accurately accounts for the percentage of research dedicated to the relationship of public versus residential applications; however, the dissemination of this feature from private residences to public building types signifies continuities and form/function adaptations throughout. In instances such as mosques and madrasas, the mashrabiya maintained climatic and privacy-seeking functions and took on new symbolic and sociable connotations. In hospitality-focused buildings such as caravanserais—though technically non-orthodox public building types due to their short-term accommodation purpose—its employment mirrors residential prototypes and fulfills commercial and observational purposes. Understanding these overlaps and distinctions underpins comprehension of the evolution of the mashrabiya across types and underpins this study’s consideration of applying the feature in diverse applications of public building types.

3. Materials and Methods: Analyzing the Mashrabiya Across Public Building Typologies

To better identify the specific features and common aspects of the mashrabiya across different geographical, cultural, and social contexts, a deductive–inductive comparative method analysis was employed. The deductions in this case are the result of an inductive study carried out using supporting material, primarily photographic, which served as a reference. This involved examining the mashrabiya in public buildings of the same typology, as this appeared to be the most suitable approach to reveal both variations and recurring characteristics, regardless of the period of construction or the geographic, social, and economic context.

To understand the impact and influence of specific contexts, this study examines case studies that are geographically distant yet united by Islamic culture. Moreover, to assess the possible evolution of the mashrabiya over time, case studies from different historical periods have also been considered. A further selection criterion for the case studies was the quality and quantity of graphic and photographic documentation available, which very often corresponds to prominent examples within the selected building categories. The choice of these analytical parameters (position in the building, dimension, material, design, function) was based on their capacity to provide key information about mashrabiyas within traditional Islamic public buildings.

In this study, symbolic, cultural, and formal criteria were assessed in an integrated manner to ensure that the mashrabiya’s significance was understood holistically. While the comparative morphological framework served as the primary analytical tool, enabling precise evaluation of proportions, patterns, materials, and functional performance, these formal observations were consistently interpreted in relation to their cultural and symbolic meanings. This approach ensured that the analysis did not privilege form over meaning, instead highlighting how environmental performance, aesthetic expression, and cultural symbolism are interdependent in the mashrabiya’s architectural role.

By comparing these aspects across examples of the same typology, this study seeks to recognize the consistent elements that form the core of the mashrabiya’s identity beyond superficial variations shaped by geographical, historical, social, and cultural influences.

The position of the mashrabiya within the building is crucial for understanding its role and its relationship with the surrounding space.

The dimensions of the mashrabiya can vary significantly and are often related to its function and the scale of the building. Comparing dimensions with respect to building typology and placement can help identify whether there are typical proportions or scales associated with specific functions or public contexts.

The material used in constructing the mashrabiya—typically wood or stone, though subject to regional variations—is a key element of its identity. This choice of material affects not only the fabrication techniques but also the aesthetic qualities, durability, and physical properties, such as its capacity to filter light and air. Additionally, comparing materials across time and place helps identify common choices or adaptations to local resources [

6,

39,

40,

41,

42].

The function performed by the mashrabiya is a central element of its identity. Its primary functions may vary in priority depending on its location and building typology. Comparing these functions in similar contexts can reveal which are consistently present and, therefore, more closely tied to their “essence” as an architectural element.

The design, such as the geometric patterns, decorations, and intricacy of the latticework, is a distinctive aspect of the mashrabiya and often reflects local cultural, artistic, and technical influences.

Comparative Analysis of the Mashrabiya Among Different Typologies

Within each category of public buildings under consideration, this work analyzes two case studies selected based on their relevance and importance.

In particular, the analysis considers the following:

Mashrabiya in Mosques: Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo, Egypt; and the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque in Ahmedabad, India

Mashrabiya in Madrasas: Bou Inania Madrasa, Meknes, Morocco; and the Madrasa of Umm al Sultan Sha’ban in Cairo, Egypt.

Mashrabiya in Bimaristans: Nur al-Din Bimaristan in Damascus; and Qalawun Hospital, also known as Al Mansour Hospital, in Cairo, Egypt.

Mashrabiya in Caravanserai: Wikala of Baazar’a (urban caravanserai), Cairo, Egypt; and the Najjarin Funduq (urban caravanserai), Fez, Morocco.

Eight case studies were selected for this research—two for each of the four Islamic public architecture types (mosques, madrasas, bimaristans, and caravanserais)—in a manner that ensured both typological cohesion and geographic variation. The Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo was selected for its centuries-long evolution in architecture, as well as for the presence within it of internal mashrabiyas connected to religious and didactic functions [

10]. The Sidi Saiyyed Mosque in Ahmedabad was selected for its world-famous jali screens, which represent an advanced example of mashrabiya-carved stones in the Indian subcontinent and reveal the aesthetic synthesis characteristic of Indo-Islamic architecture.

For the madrasas, the Bou Inania Madrasa in Meknes is a well-preserved manifestation of Marinid architecture in Morocco, whose finely crafted wooden mashrabiyas are representative of North African traditions of craftsmanship. The Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha’ban in Cairo was selected for its new urban form and imposing stone mashrabiyas, which express the building’s characteristic corner frontage, revealing the relationships among ornamentality, visibility, and urban form.

For hospital typology, the Damascus Nur al-Din Bimaristan was included, as it was one of the earliest extant Islamic hospitals and featured a stone mashrabiya within an architectural complex where form is counterbalanced by religious/spiritual and decorative intent. Its mirror image in architectural ambition was the Mamluk state’s Qalawun Hospital in Cairo, which interposes various mashrabiyas between public streets and internal courtyards and is therefore an ideal case for testing the interplay between environmental and representational functions. For caravanserais, the Wikala of Baazar’a in Cairo was chosen for its urban context and for the projecting wooden mashrabiyas on the upper floors, which provide graphic demonstrations of how residential privacy and climatic control were addressed within commercial lodging edifices. The Najjarin Funduq in Fez was chosen for both its original status as a craftsman’s inn and for the photographic evidence from the early 20th century, which demonstrates now-lost mashrabiyas, offering a remarkable glimpse into former Moroccan hospitality architecture configurations.

These case studies include a geographically and culturally diverse sample spanning North Africa, the Levant, and South Asia, for which there is abundant textual and visual documentation. They can be compared substantively with each other to understand the evolution of mashrabiyas’ design, construction, and purpose in various types of public architecture and regions within the Islamic world.

In pursuing the comparative morphological and typological method, this research systematically connects the physical characteristics of the mashrabiyas—i.e., proportions, lattice density, composition of materials, and building technique—with the larger cultural, historical, and environmental settings in which they were made. Typological categorization allows shared design solutions within each category of public building to be identified, and morphological analysis shows how these solutions are adapted or transmuted in response to regional availability of materials, artisanal capability, and climatic demands. For instance, the use of wood or stone involves structural and aesthetic preference but also involves regionally specific crafting customs and symbolic significance. Integrating these contextual aspects into the morphological/typological system allows the analysis to ensure that form is read as an articulation of functional performance and sociocultural significance, thereby allowing an integrated understanding of the mashrabiya across a range of Islamic public building types.

While the comparative morphological approach forms the structural backbone of this study, it is inherently intertwined with the cultural, historical, and material contexts of the examined buildings. The mashrabiya, as both a functional and aesthetic device, cannot be fully understood without considering the regional availability of materials, their climatic responsiveness, and the artisanal traditions that shaped their fabrication. Variations in wood species, joinery techniques, and decorative motifs across regions not only influence the durability and performance of the mashrabiya but also embody local identity and symbolic meaning. Therefore, in each case study, the morphological description is integrated with an assessment of how these cultural and material factors have influenced design choices, enabling a more holistic understanding of sustainability, symbolism, and aesthetic expression in the mashrabiya tradition.

4. Results from Eight Case Studies of Mashrabiyas in Islamic Public Buildings

4.1. General Overview—Functions and Cultural Context of the Mashrabiya

Whether the mashrabiya was first introduced in public buildings or private residences remains uncertain; nevertheless, its etymology suggests that its original and primary purpose was to cool water in terracotta jars (a prevalent practice in residences), whereas in public buildings its functions seem to be more closely connected to the notion of privacy. This aspect is particularly important and sensitive in the Islamic culture [

1] because it is aligned with the core values of modesty and sanctity of private life and avoiding unnecessary exposure. Therefore, the built environment must protect the occupants, especially women, from unwanted visibility. The design of the mashrabiya was then an efficient solution to grant privacy while still maintaining ventilation and natural light control. Public buildings in Islamic architecture hold particular importance because, in addition to fulfilling practical needs (such as praying, educating, healing, and hosting), they have a strong spiritual connotation aimed at celebrating and spreading the Islamic faith.

Traditional Islamic architecture views public buildings as structures primarily intended to serve the community thoroughly, offering suitable spaces for a wide range of activities, including worship, gathering, public governance, education, hospitality, and medical treatment. Strategically located and well integrated within the urban fabric, these buildings, in addition to fulfilling specific practical functions, aimed to represent the efficiency, grandeur, and prosperity of the Islamic state. Consequently, the architectural language often emphasizes and exalts the public function in a stately manner.

Often, the materials used to construct these buildings were locally sourced.

As part of the applied methodology, we identified and selected the following four categories of public buildings: mosques, Quranic schools or madrasas, hospitals or bimaristans, and inns or caravanserai [

43].

4.1.1. Mosques

Mosques can be considered to be the most important and widespread public buildings in Islamic architecture, as they represent the primary place of congregation and prayer for Islamic communities. Designed and built according to ancient principles and guidelines, among which the most important is the Qibla (the orientation towards the Kaaba, a cubic building located within the Sacred Mosque in the city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia), mosques are generally composed of three elements that correspond to their main functions: a main prayer hall, dedicated to prayer and prostrations; one or more minarets for locating the mosque even from a far distance and for calling the faithful to prayer; and a space to perform ritual purification (ablution) before prayers.

4.1.2. Madrasas or Quranic Schools

The earliest form of education, particularly religious education, was often conducted within mosques. As Islam expanded, the necessity emerged to accommodate students arriving from various regions to study in prominent educational centers. This led to the creation of institutions like madrasas, which provided both instruction and lodging for these students. These centers not only provided theological education but also encompassed the major scientific disciplines of that time. As madrasas evolved, they played an increasingly crucial and pivotal role in disseminating Islam, eventually becoming autonomous structures separate from mosques. These complexes commonly included internal courtyards, lecture halls, and student dormitories.

4.1.3. Caravanserai/Inns

Caravanserai seems to derive its origin from the Persian word “karvān-sarāy”, meaning “caravan palace”. A constant feature of Islamic culture was the movement of people and goods. Islamic culture, with its nomadic roots, has always been associated with movement. As Islam spread, travel routes became increasingly important, especially for trade and pilgrimages. This generated a need for safe havens for these travelers, primarily merchants and pilgrims. Caravanserais answered this need, providing secure rest stops along the principal routes of communication for people and their animals. In addition to this rural setting, there was also an urban version. These facilities had several names, such as khan funduq, ribat, and manzil, which reflected slight differences in their functions and related shapes.

4.1.4. Hospitals/Bimaristans

In Islamic culture, the care of the sick was initially carried out within dedicated tents that could be easily moved and relocated as needed. Later, proper buildings emerged that, in addition to providing treatments, also addressed the psychophysical well-being of patients by offering them gardens, fountains, and recreational activities.

These structures were the first to be organized by separating patients by gender, a practice still in use worldwide today.

4.2. Analysis Across Building Categories

Before conducting the comparative analysis of mashrabiyas within their specific building types, some general information about the buildings is provided to offer a better understanding of the context. However, the focus and in-depth analysis are not on the building itself, but rather on its representative typology and how the mashrabiya integrates and interacts within this category of historical public building, along with its significance. It is essential to clarify that, when a building features multiple mashrabiyas (which is not unusual), a general overview is provided; however, the main focus of the analysis is on a single, representative one. This selection prioritizes the most significant examples, those that encapsulate the characteristics of others, or those holding a more prominent position within the structure.

4.3. Mashrabiyas in Two Mosques (Egypt and India)

4.3.1. Al-Azhar Mosque

Located in the historic center of Cairo, Egypt, this mosque, whose construction dates back to the early 11th century, is one of the oldest and most significant mosques in the Islamic world. Over time, this mosque became not only an important center of worship but also a key reference point for education, eventually becoming one of the oldest Islamic universities in the world [

44]. The mashrabiya is not a widespread element throughout this mosque but appears in specific locations tied to particular functions. The mashrabiya examined (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) is an integral part of the interior façade that, through a portico, overlooks the inner courtyard.

Dimensions and Material: Of considerable size, this mashrabiya was made of solid wood, presumably teak, oak, or cedar, chosen for their durability and the relative ease with which they could be carved and crafted.

Design: The mashrabiya connects the floor both visually and physically to two vertical elements of the façade (walls), albeit without completely closing the upper part: it does not reach the intrados of the architrave but stops at a certain height. Rectangular in shape, it displays a clear horizontal emphasis in its composition, articulated in five bands. The upper and lower bands are each divided into four panels: the upper ones are solid and decorated with inscriptions, while balusters characterize the lower ones. The three central bands, on the other hand, are each divided into five panels, breaking the overall vertical alignment and reinforcing the horizontal one. Within these central bands, the panels symmetrically alternate between baluster elements and diagonal interlacing patterns. In this specific example, the geometric design of the mashrabiya is quite simple and repetitive; however, the alternation of the adopted geometric patterns creates an interesting and visually pleasing composition. Consistent with Islamic art principles that emphasize abstraction and geometry, there are no figurative decorations.

Function: The mashrabiya, in this case, becomes an effective tool for dividing spaces with a thin, semi-permeable screen that allows for the controlled passage of light, sunlight, and ventilation.

4.3.2. Sidi Saiyyed Mosque

Located in the old city of Ahmedabad (Northwest India), this mosque was built around 1573 by Sidi Saiyyed, a prominent figure of the Sultan’s court. Although it was primarily erected to provide the local Muslim community with a place for worship, it was also a means to showcase Sidi Saiyyed’s faith and social status [

45].

The jali screens (also known as mashrabiyas in this part of the world) in this mosque are some of the most iconic examples of stone latticework in Indo-Islamic architecture. Located on the upper side of the rear wall of the prayer hall, they follow the shape of the pointed arch openings (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Dimensions and Material: Although fairly large, these jalis become even more interesting when we consider that they were made from yellow sandstone, the same material used for the construction of the mosque itself. This stone was widely available locally and, therefore, well known to the local artisans, allowing them to achieve such intricate and precise carving with a material they had long mastered.

Design: The distribution of the jalis in the rear wall is symmetrical in both position and pattern. While the central arch is filled solid with masonry, the two latticed panels on either side feature an intricate and exquisitely delicate design, depicting a tree with branches curling upon themselves. This particular jali screen, considered to be a true work of art, is the reason why the mosque is renowned worldwide. Finally, at the far ends, there are two examples of jalis that are especially relevant to this study. Although it follows the arched shape of the opening, this jali is divided into square panels arranged in five horizontal and nine vertical rows. The bottom row displays an asymmetrical arrangement of panels featuring purely geometric patterns. In contrast, the upper rows are more uniform, featuring highly stylized floral designs or patterns made of interlaced polygons and arabesques.

Functions: At first glance, the position of these jalis might suggest that their function is limited to controlling natural light and ventilation, seemingly excluding the role of providing privacy. However, a closer study of the mosque’s structure reveals that privacy is ensured by the solid perimeter walls, made possible precisely because the jalis provide light and ventilation. Therefore, even indirectly, these elements contribute to preserving the sense of privacy and intimacy that is essential in a place of worship. Furthermore, the refinement and exquisite craftsmanship of the designs go beyond mere function, suggesting an intention to celebrate the grandeur of Islamic culture.

4.4. Mashrabiyas in Two Madrasas (Morocco and Egypt)

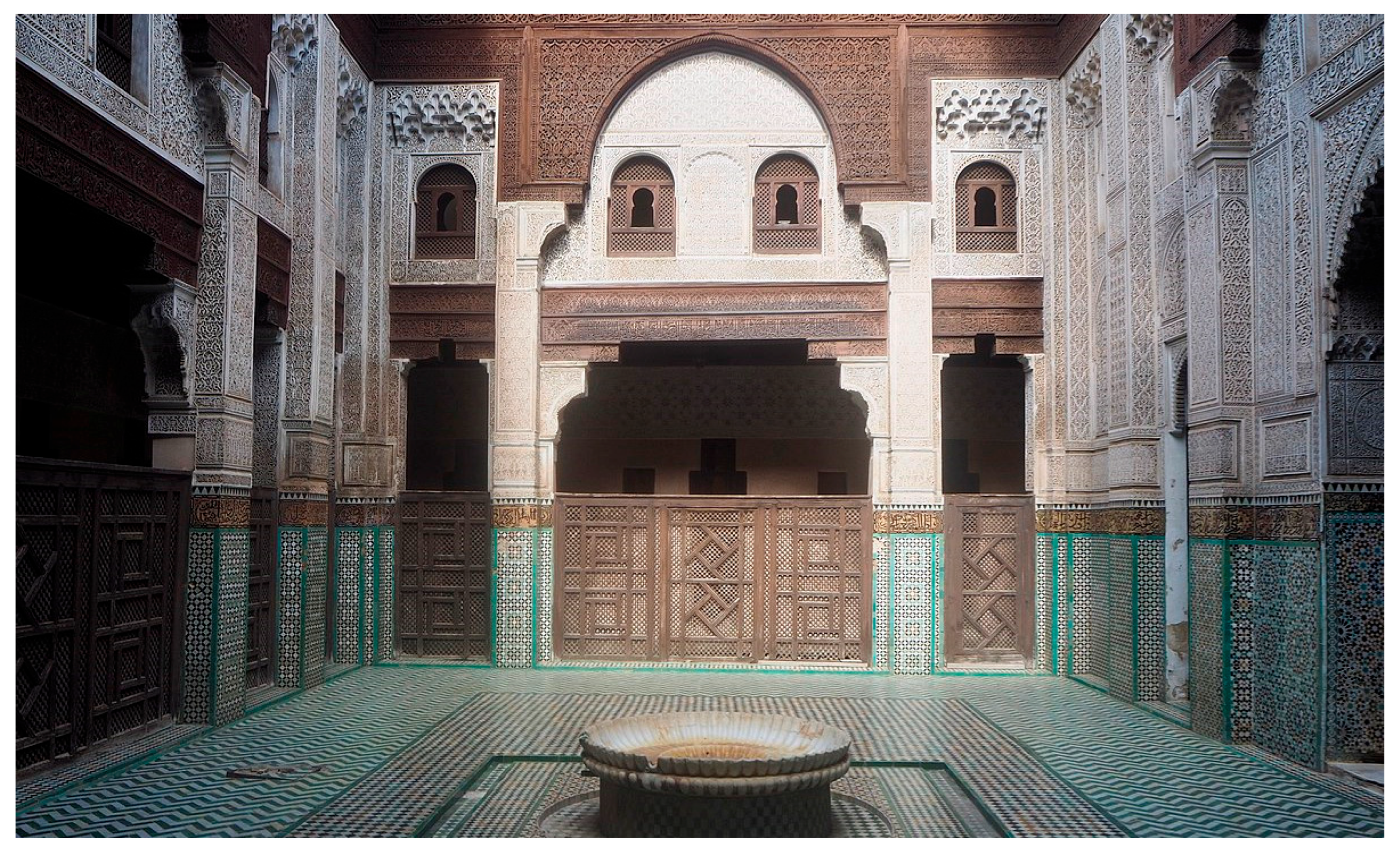

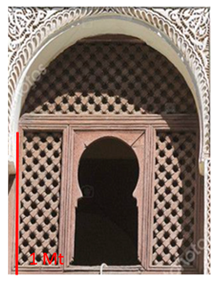

4.4.1. Bou Inania Madrasa, Meknes, Morocco

Located in the heart of the historic medina of Meknes, Morocco, this madrasa, built around 1335, represents one of the most significant examples of Marinid architecture in the country [

46]. The madrasa comprises 39 student rooms, 13 of which are located on the ground floor and 26 on the upper level, all arranged around a central open space. This courtyard is renowned for the richness of its internal façades, which are adorned with glazed tiles, finely carved stucco panels, and intricately carved wooden mashrabiyas. These latter elements on the ground floor of the building alternate with pillars, creating an interesting chromatic effect and generating screened passages on three sides of the inner courtyard. Mashrabiyas are also present on the first floor of the building, but in this case they are of a smaller size and correspond to the arched openings of the student rooms overlooking the courtyard. Although all are worthy of interest and study, this work’s attention focuses on the mashrabiyas of the first-floor window openings, allowing for a better comparison with the type of mashrabiya in the second madrasa case study.

Symmetrically arranged on the interior façade of the prayer hall, the four mashrabiyas are essentially identical in form, dimensions, and design. The specific one under analysis is among the two central ones, which are topped by a pointed arch crafted from finely inlaid wood (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Dimensions and Material: Fitting the arched window openings, these mashrabiyas can be considered to be of small to medium size. They are made of carved wood, a material commonly used in mashrabiyas of North African Islamic architecture, particularly in Morocco [

47].

Design: The mashrabiya is made of interlocking pieces of wood, while at the center there is an opening with the shape of a miniature pointed arch. This miniature arch is located at the center of the mashrabiya and is itself framed by wooden elements, only the horizontal ones of which extend to the perimeter. This mashrabiya is composed of three horizontal bands, all characterized by interlocking wooden pieces. The broader central band is split into three elements, with the central, openable one mimicking in miniature the arch of which it is part.

Function: The mashrabiya is not only an important decorative element that enhances the madrasa’s visual composition and spiritual atmosphere but also provides privacy for student residences and serves a crucial environmental purpose.

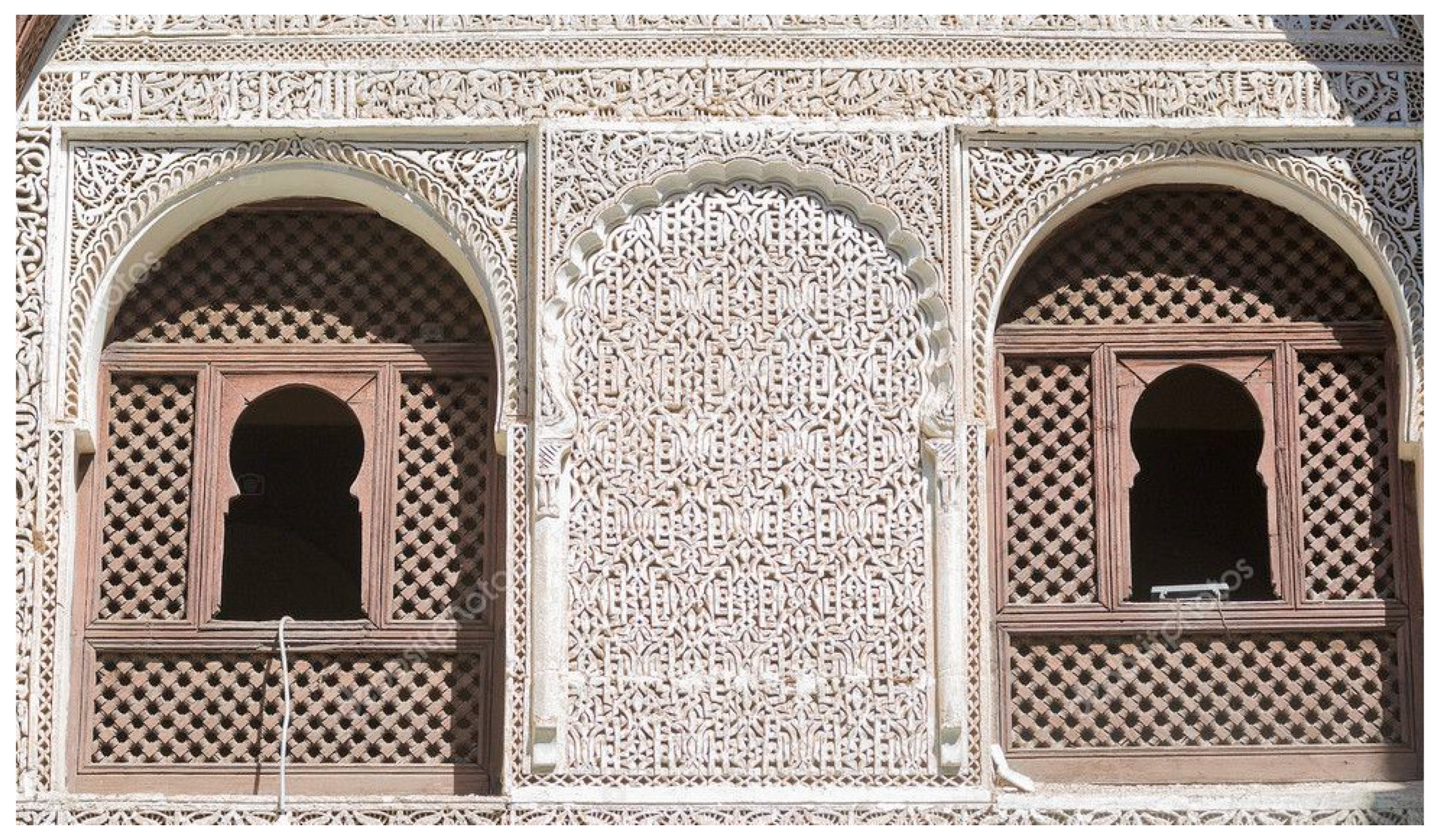

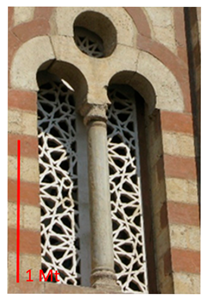

4.4.2. Madrasa of Umm al Sultan Sha’ban, Cairo, Egypt

The Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha’ban, located near the Citadel of Cairo, was built around 1368 in honor of the Sultan’s mother following her pilgrimage to Mecca, as indicated on the foundation inscription in the building. The madrasa originally housed the two Sunni schools of law: the Hanafi and the Shafi’i [

48].

Positioned at the intersection of Tabbana Street and a small side street that joins it at an angle, forming a three-sided façade around the corner, the structure has an interesting layout. It represents the first example of its kind in Cairo, properly oriented towards the Kaaba in Mecca.

Precisely because the iconic three-sided façade around the corner is one of the building’s distinctive elements, this study focused on a mashrabiya situated on this façade. Characterized by an alternation of different colored stones that create horizontal bands and add rhythm to the design, the façade features two orders of openings on the upper floors: single-arched on the first floor, and bifora on the second floor, all fitted with mashrabiyas (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

Position in the Building: The mashrabiya is integrated into arched openings (single and bifora) located on the upper levels of the building, and they are recessed within the bearing stone walls of the façade.

Dimensions and Material: Consistent with the building’s main material, these mashrabiyas of small-to-medium dimensions are largely stone-carved.

Design: The design is repetitive and symmetrical, derived from geometric forms that recall circles, polygons, and stars.

Function: These mashrabiyas fulfilled two main roles: providing sufficient ventilation and natural light. A privacy function is also plausible, although this was likely less emphasized given the height and placement of the openings. Crucially, the decision to incorporate such beautiful mashrabiyas, distinguished by both their material and their intricate design, was consistent with the building’s main purpose. This structure was intended to simultaneously honor Islamic faith and proclaim the power of its patron.

4.5. Mashrabiyas in Two Bimaristans (Hospitals) (Syria and Egypt)

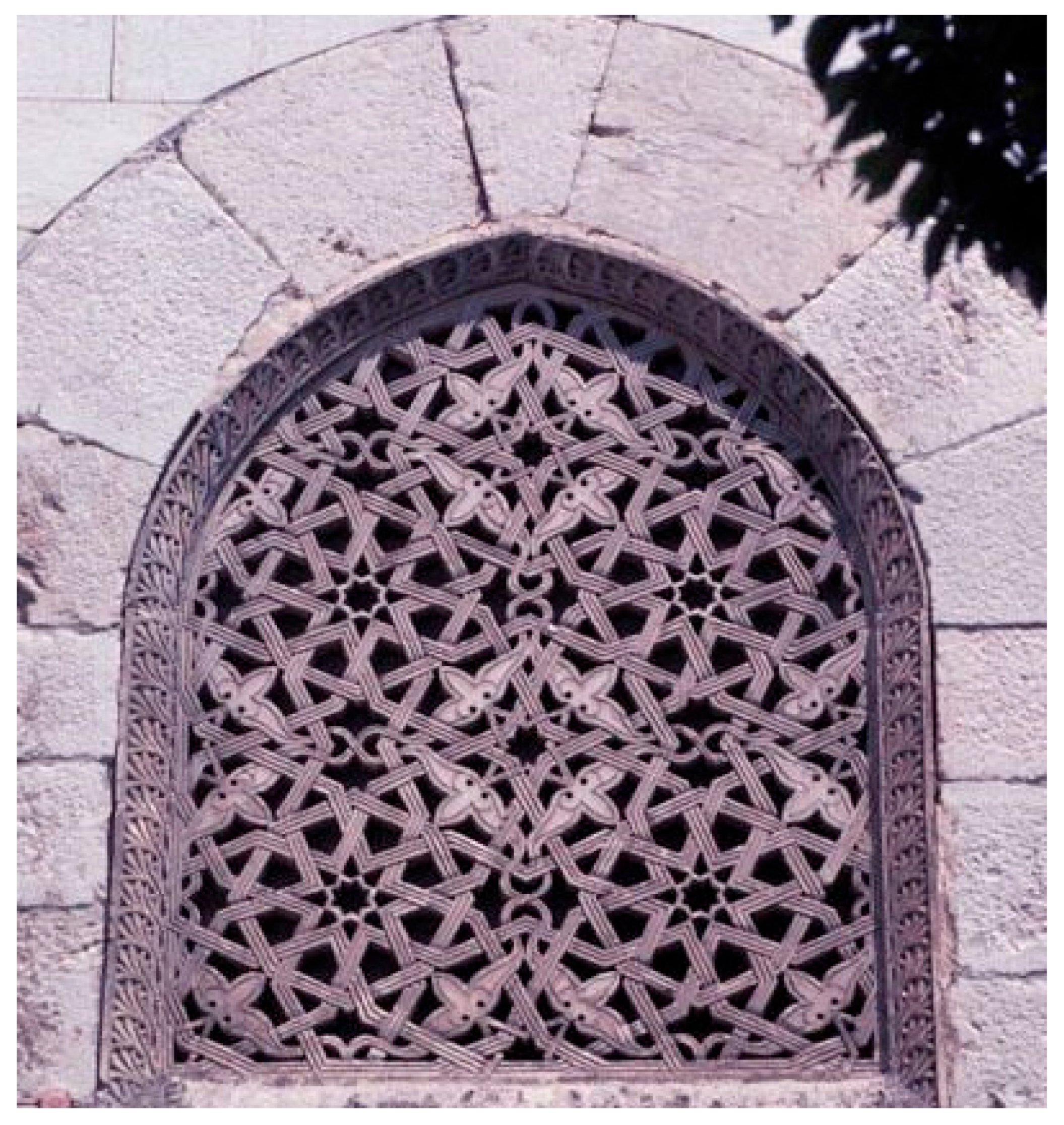

4.5.1. Nur al-Din Bimaristan, Damascus

Located in the heart of the old city walls of Damascus, this building, which served as a hospital until the 20th century, was constructed in two phases: the original core was completed in 1154, and a later expansion followed in 1242 [

28].

Modest in size, the building is organized around a rectangular central courtyard, which ensures light and ventilation to the interior spaces thanks to the mashrabiya, the subject of this study. One of the building’s most distinctive features is the entrance portal, crowned by a large muqarnas [

49] niche carved in stone, a significant example of medieval Islamic architecture for which this building is well known worldwide.

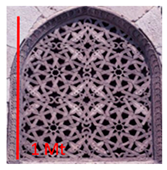

Dimensions and Material: The mashrabiya being studied is located above the stone lintel of the doorway connecting the courtyard to the interior rooms. Photographic evidence suggests that its width closely matches the door below, and it fills the entire pointed archway built with shaped stone blocks. The same stone has been used for the mashrabiya, in this case finely carved, indicating the level of expertise achieved by the local craftsmanship.

Design: Set within a pointed arch opening, the mashrabiya is further embellished by a full and finely carved frame that serves as the transitional element between the solidity of the stones that constitute the arch and the lightness of the screen. The design of the central part, although very intricate at first glance, reveals the presence of geometric elements that repeat to form floral and star-shaped compositions (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

Function: The refined design of the mashrabiya, in addition to enriching the aesthetics of the passage, helps to provide an adequate level of ventilation and lighting from the courtyard towards the interior spaces. The height and placement of the mashrabiya suggest that, in this case, the privacy function was not the primary one, although it was still present.

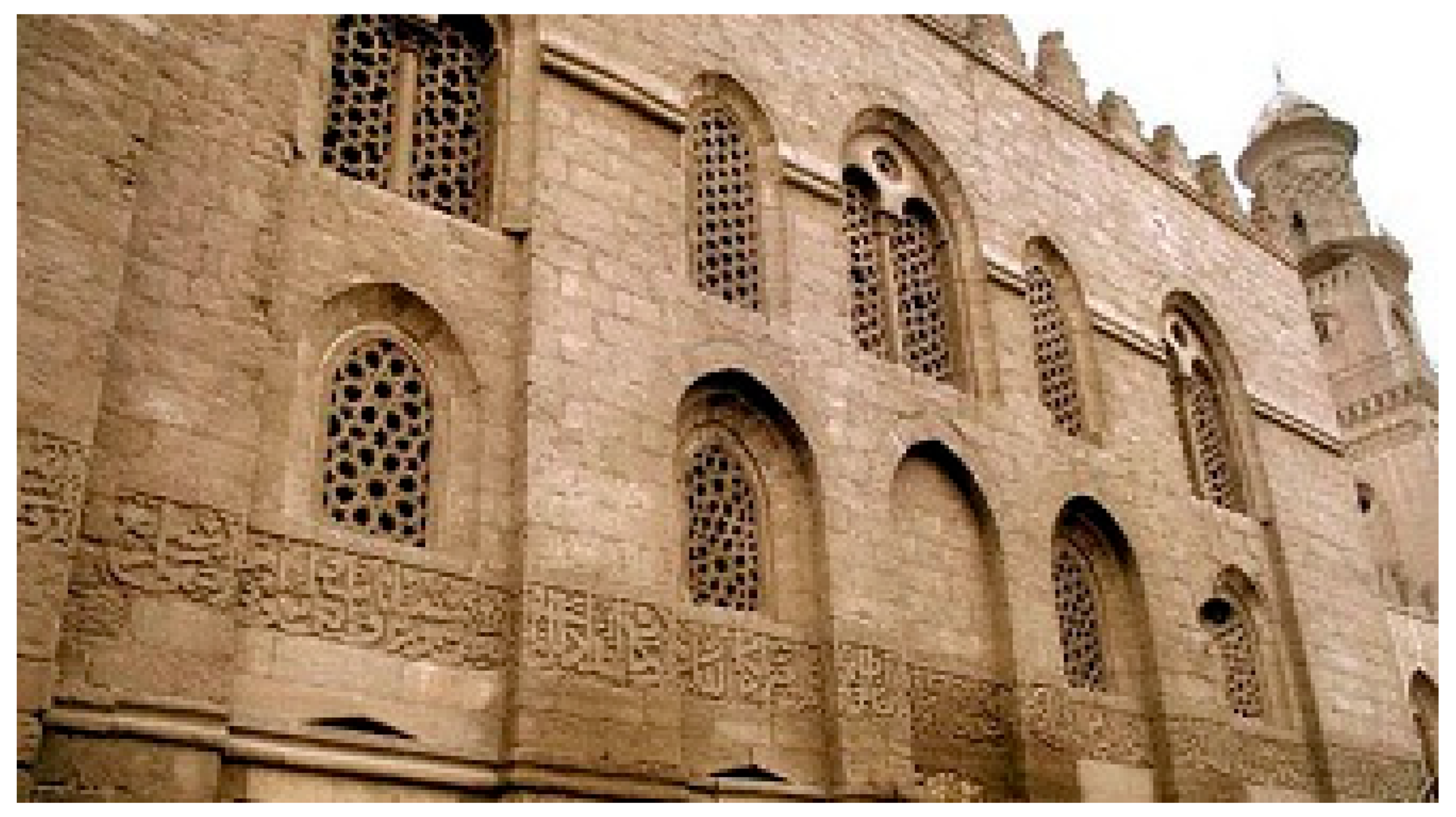

4.5.2. Qalawun Hospital or Al Mansour Hospital (Bimaristan)

There is a common thread, linked to a human story, that connects the bimaristan previously analyzed in Damascus with that of Al-Mansour present in Cairo. Sultan Al-Mansour, who initiated the construction of the bimaristan in Cairo, had previously received treatment for a serious illness at the Damascus facility. This experience, which surely marked his life, was the reason he decided to build similar structures in Cairo as well. The Qalawun Hospital was built in 1284, inspired by the concept of the hospital in Damascus [

50]. Located on Al-Muizz Street, one of the most important and oldest streets in Cairo, this sizable structure is built around a central courtyard, extending three stories above ground. Ventilation and natural lighting are ensured by a series of arched openings, both single and double lancets, present on the upper floors of both the external and internal façades, the latter facing the courtyard. All openings are provided with mashrabiyas (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

Dimensions and Material: In general, the dimensions of these mashrabiyas can be considered to be medium–small, while the material used is stone, which gives a more durable presence suitable for public institutions like hospitals.

Design: The geometric motif used, although simple, is consistent across all of the openings, ensuring aesthetic and formal uniformity. In this case, the mashrabiya design recalls an abstract sequence of floral motifs.

Function: In this particular case, the primary functions are air circulation and light control. As these mashrabiyas are located on an upper floor, they mediate between the interior rooms and the exterior environment rather than separating specific spaces. The mashrabiya also plays an important decorative role in the façade of the hospital.

4.6. Mashrabiyas in Two Caravanserai (Egypt and Morocco)

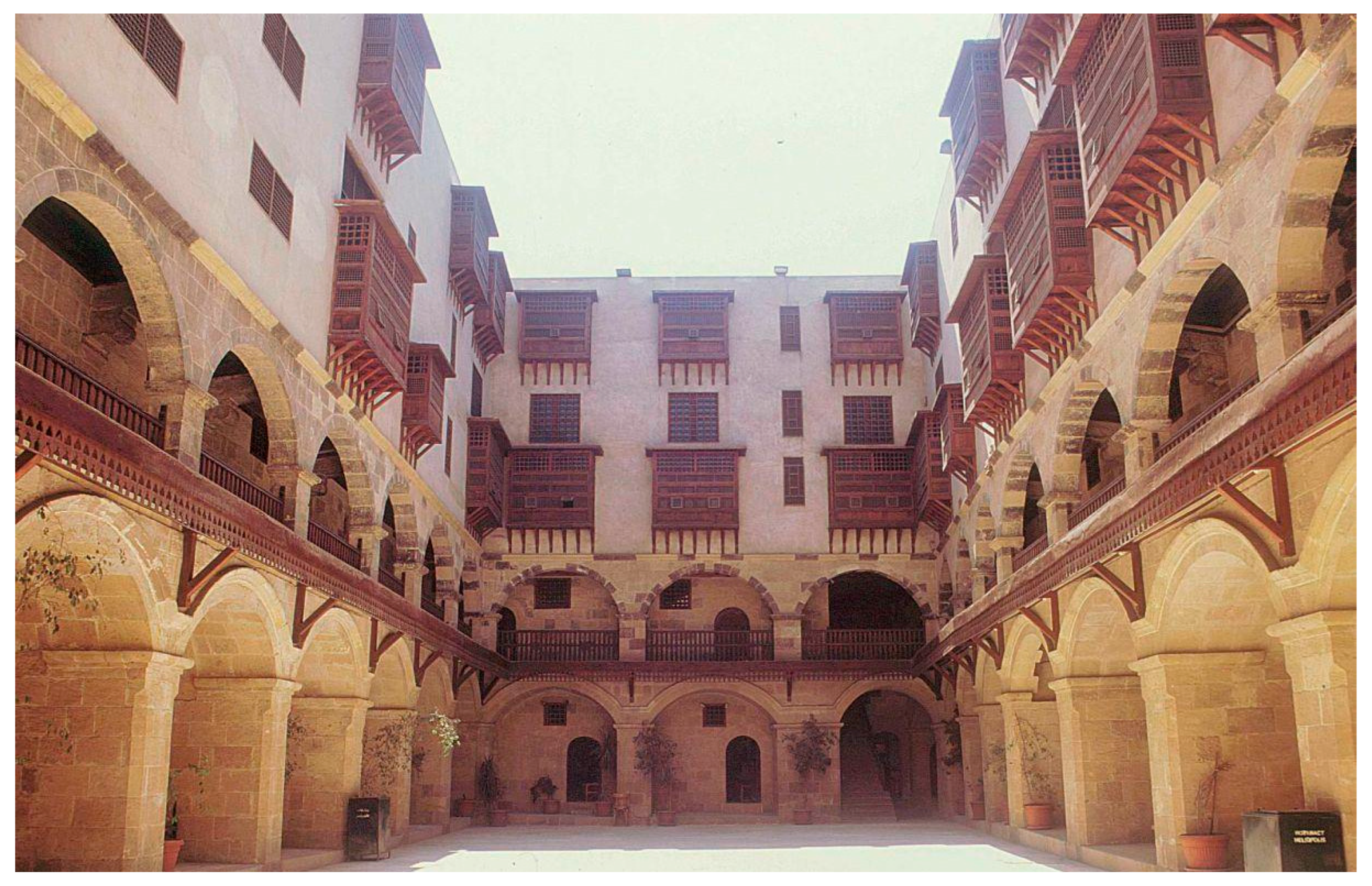

4.6.1. Wikala (Caravanserai) of Baazar’a, Cairo

Wikala al Baazar’a is a type of urban caravanserai dating back to the 17th century, which served as a place for trade and lodging for foreign merchants who needed a place to stay when doing business in the city. Located in what was Cairo’s most significant commercial district during the Fatimid era, the building is organized around a central rectangular courtyard and consists of four floors. The building comprises two main sections: a commercial area spanning the ground and first floors around the courtyard, and a two-story residential wing [

51].

The wikala has two entrances: the first is the main entrance that leads to the courtyard, and the second is a private entrance that leads to the upper residential units and is not connected to the courtyard. It ascends directly to the residential floors, taking into account privacy and separating commercial traffic from the guest area. The building’s façades facing the inner courtyard are articulated on the first two floors by round arches. Above these, the top two residential floors feature projecting mashrabiyas that rest on custom-designed corbels, specifically crafted to bear their weight (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

Position in the Building: As previously mentioned, these mashrabiyas are located on the upper floors of the building, corresponding to the guest accommodations. They allow occupants to observe activities in the central courtyard while maintaining a high level of privacy. All of the mashrabiyas appear to have the same dimensions, form, and design.

Dimensions and Material: In this case, the mashrabiyas are remarkably large and project outwards thanks to their supporting corbels. Crafted from wood on a lathe, they strongly resemble those found in private residences, highlighting the artisans’ skill in producing these protective screens.

Design: The mashrabiya extends outward from the main wall, supported by wooden brackets. Rather than being a single continuous screen, each mashrabiya is segmented into small rectangular panels. The lower panels feature a tighter, more intricate weave, which progressively loosens in the upper sections. Within the lattice, there are smaller, operable windows that can be opened for air circulation or a better view.

Function: In this case, the mashrabiya fulfills all of its traditional functions, namely, both environmental and privacy-related ones.

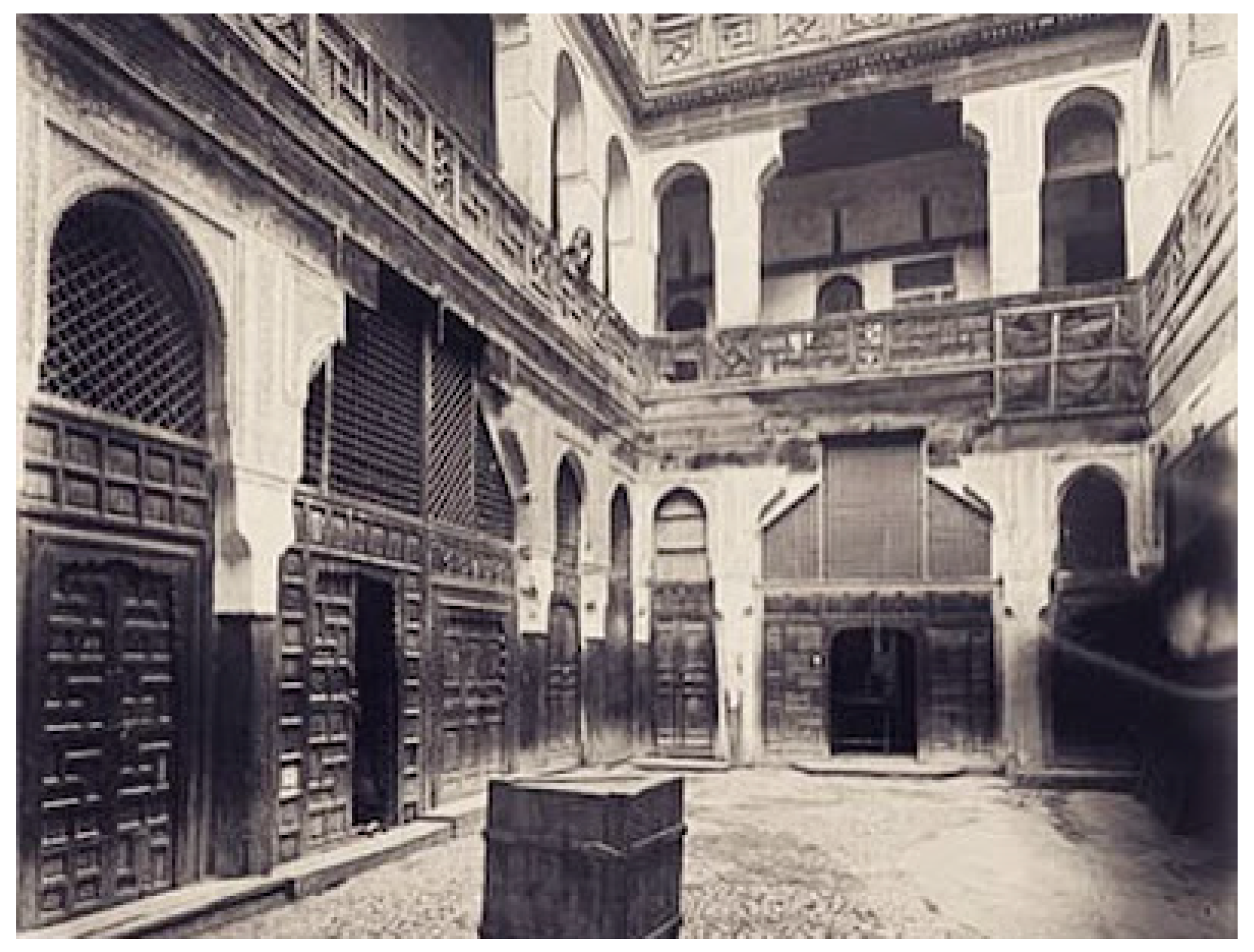

4.6.2. The Najjarin Funduq (Urban Caravanserai) Fez

The Najjarin Funduq was renowned as the inn of carpenters, situated in the heart of the medina quarter in the city of Fez. It is substantially an urban caravanserai, although in this part of the world it is called a funduq.

Built in 1711, this three-story building is organized around a central courtyard that served commercial functions and provided hospitality for merchants and woodworking artisans. Following a restoration that was completed in 1996, this building became the home of the Museum of Wood Arts and Crafts. However, some of the wood features, which were still present at the beginning of the 20th century, were not included in the renovation project (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16). For this reason, this study refers to some old images of this building (dated to the beginning of the 20th century), which show a mashrabiya present on the ground floor [

24,

52].

Position in the Building: The ground floor of the building opened onto an inner courtyard through a portico, symmetrically divided by pillars with varying distances between them, surmounted by arches of different sizes. While doors occupied the space between the two columns, articulated on one or more leaves, the upper part featured a single mashrabiya.

Dimensions and Material: The size of these mashrabiyas varies according to the size of the door below. They are made of turned and carved wooden pieces, typical of Moroccan and North African architectural traditions.

Design: The design is a dense grid of small, interconnected wooden elements. Here, the design’s simplicity appears consistent with the social status of the likely clientele, who favored solutions that were aesthetically understated but highly effective from a functional perspective.

Function: Considering their position, it is reasonable to assume that the primary function of these mashrabiyas was to ensure ventilation and lighting, while also acting as a barrier against unwanted intrusions into what were most likely the goods warehouses on the ground floor.

These eight case studies reveal the adaptability of mashrabiya design in serving typologically distinct public functions. Whether functioning as a symbolic barrier, a climatic regulator, or a social interface, the mashrabiya emerges as a vital component of Islamic public architecture. The following discussion highlights commonalities and divergences observed in form, materiality, and cultural connotations across various building types.

5. Discussion—Regional Influences and Typological Variations in Mashrabiya Design

The discussion builds directly upon the methodological framework outlined in

Section 3, where symbolic, cultural, and formal criteria were established as complementary lenses for the analysis. While the comparative morphological approach provided a structured means to assess proportions, patterns, materials, and functional performance, these findings—synthesized in

Table 1—are here interpreted in light of the symbolic and cultural values previously defined. This integrated reading ensures that the formal characteristics of the mashrabiyas are not examined in isolation but are understood within their broader historical, climatic, and sociocultural contexts, thereby reinforcing the connection between methodological intent and analytical outcomes.

The following discussion directly addresses the research question by examining how regional and typological factors influenced the design, materiality, and functional role of the mashrabiya.

5.1. Comparative Analysis of Mashrabiyas in Mosques

This section introduces the comparative examination by analyzing the presence of the mashrabiya in two mosque case studies: Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo and Sidi Saiyyed Mosque in Ahmedabad (

Table 1). Mosques, as the ultimate representative form of Islamic public architecture, are simultaneously spaces for worship and cultural and social icons. A comparative examination of the employment of mashrabiyas in such sacred spaces provides insightful evidence on how thoughts about functionality, religiosity, and aesthetic considerations converge in their design. A comparison between the locations, materials, geometry, and symbolic content of the mashrabiyas in the two mosques tries to unveil general principles as well as local adaptations responsible for shaping their architectural form. These observations also contribute to providing context for the evolution of the mashrabiya in other public building types, as discussed in the subsequent sections.

By examining the mashrabiyas (jalis) of these two renowned mosques—both exemplary of traditional Islamic architecture—it is possible to draw some initial preliminary considerations through a comparative analysis aimed at highlighting differences and similarities. What immediately stands out is the presence of these architectural elements, still found in both sacred buildings, nearly five centuries after their initial construction. This may suggest that the mashrabiya (or jali) has, over time, transcended its purely functional aspects, although important, and assumed a symbolic meaning deeply connected to Islamic culture. Temporal and geographical differences have influenced the choice of materials: hardwood in Egypt and sandstone in India (the latter perhaps also facilitated by the technological development of the tools used for sculpture). Despite the variations in their respective designs, in both cases, abstract geometric motifs (central to the Islamic decorative tradition) are present, repeated alternately to reflect the concept of unity and oneness, known as Tawhid. In Islamic ideology, Tawhid is the central notion validating the oneness and unity of God, including His uniqueness, sovereignty, and indivisibility. Aside from its theological dimension, Tawhid further encompasses Islamic art and architecture, wherein it manifests in the form of harmony, balance, and unification of all elements into a single whole. In architecture, this principle manifests itself in the repetition of geometric motifs, the interplay of light and shadow, and proportional systems hinting at order and unity. From another perspective, the mashrabiya, with its latticework pattern, may be viewed as a concretized form of Tawhid—its interlocking and repetitive motifs symbolically signifying the interconnectedness and unity of creation under divine order. Geometric patterns serve as visual representations of this concept: the unity of creation and the indivisible nature of the divine.

5.2. Comparative Analysis of Mashrabiyas in Madrasas

This section examines the use of mashrabiyas in two historic madrasas: the Bou Inania Madrasa in Meknes, and the Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha’ban in Cairo. Madrasas, by definition, are places for study ingrained in religious and intellectual life, generally requiring a balance between openness and enclosure, particularly in study and residential areas (

Table 2). The employment of mashrabiyas within such building types illustrates how environmental control, privacy for sight, and aesthetic sophistication were integrated into pedagogic spaces. Through comparative analysis, this study considers how location, materials, and formal design reacted to cultural, climatic, and architectural traditions within regions.

This comparison highlighted that the mashrabiyas in the two madrasas have a different position within the building and, therefore, play a slightly different role.

The screen in the Moroccan madrasa faces an internal courtyard from an upper level, while the one in Cairo is located on the upper floor of the external façade. The one in Meknes seems to be linked to a discreet and contemplative space, while the mashrabiyas on the external façades in Cairo are more engaged with the public area of the surrounding streets. The mashrabiya in the Meknes madrasa is crafted from wood; its design is simple and consists of a grid, presenting a contrast to the richly worked stucco frame that encloses it. Conversely, the mashrabiya in Cairo is made of stone, and its craftsmanship, while featuring repetitive geometric patterns, is considerably more elaborate and of a larger scale, ensuring its visibility from the street. Regarding the functions served by these protective screens within their respective educational buildings, it is reasonable to assume that, in the Bou Inania Madrasa, in addition to fulfilling the primary mashrabiya function of cooling and light regulation, it also allows students occupying the elevated spaces overlooking the courtyard to observe without being seen. In contrast, for the mashrabiyas situated on the exterior façades of the Cairo madrasa, the regulation of light and air is the predominant function, supplemented by their aesthetic role, as the intricate perforation of these screens imparts a sense of lightness to the entirely stone-built structure.

5.3. Comparative Analysis of Mashrabiyas in Bimaristans

The following discussion considers bimaristans—Islamic hospitals—as one such typology where mashrabiyas served functional as well as therapeutic purposes. The primary case studies for considering intersections among privacy, hygiene, lighting control, and symbolic ornament in therapeutic environments are the Nur al-Din Bimaristan in Damascus and the Qalawun Hospital in Cairo (

Table 3). A comparison between the form and placement of mashrabiyas in the two facilities focuses on attention to patient comfort and indoor quality, while also reflecting broader cultural values embodied in built spaces for healthcare.

When comparing the mashrabiyas in both bimaristans, we immediately notice that they are made of the same material (carved stone). While wood was the more prevalent material for these screens in Egypt, stone was chosen for this example, most probably for its durability. The design of the mashrabiyas, albeit with slight differences, primarily consists of the repetition of geometric patterns. The mashrabiya in Nur Al-Din Bimaristan is positioned over a doorway overlooking the courtyard. At the same time, in Al Mansour Hospital, we have multiple mashrabiyas across the upper façade, facing both the road and the internal courtyard. While concerning the aesthetic features, the mashrabiyas played a role in both cases, their functions are determined by their position within the building. In the Nur al-Din Bimaristan, the mashrabiya’s position above the doorway, facing the courtyard, indicates that its main function was likely to mediate between the external and internal environments, regulating airflow and light. Regarding the Al-Mansour Hospital, the numerous screens in the openings from the first floor upwards suggest an ornamental role coupled with passive cooling, as the elevated location of the mashrabiyas inherently provided privacy.

5.4. Comparative Analysis of Mashrabiyas in Urban Caravanserai

This section turns to the mashrabiya as employed in urban caravanserais, such as the Wikala of Baazar’a in Cairo and the Najjarin Funduq in Fez. Caravanserais were multi-purpose building sites that incorporated hospitality, commerce, and storage, and they may also have served as secure bases for wandering merchants (

Table 4). The adoption of mashrabiyas in such sites was a logistical accommodation to the need for surveillance and security for goods. This comparative study examines how such elements were positioned, scaled, and detailed to meet both functional needs and local building traditions, providing insights into how vernacular design enabled mobility and commerce across the Islamic world.

The mashrabiyas examined in urban caravanserais pertain to ancient Islamic public buildings associated with hospitality, specifically caravanserais. These structures often served a dual purpose: providing lodging for merchants, and functioning as centers for commerce and trade. This analysis focuses on the mashrabiyas present in two urban caravanserais. As previously mentioned, while “caravanserai” is the most widespread term for such establishments, the nomenclature varies by geographical region. In this context, the term “wikala” is used in Egypt, whereas “funduq” is employed in Morocco. In both cases, the mashrabiyas overlook an internal courtyard—a characteristic feature of these types of public buildings. However, their placement and dimensions differ in the Wikala of Baazar’a, where the mashrabiyas are prominent, projecting structures located on the upper floors of the building.

In contrast, in the Funduq Al-Najjarin, they are positioned on the ground-floor portico, above the door lintels. It is evident that the mashrabiyas in the Egyptian caravanserai primarily serve to ensure the privacy of guests, as well as facilitating cooling and natural light control. In contrast, the mashrabiyas of the Funduq Al-Najjarin, while also aiding in ventilation and light regulation, additionally play a significant role in enhancing safety.

To provide authenticity and accuracy for the comparison of morphologies, photographic materials pertaining to the case studies of the mashrabiyas were examined and are shown at either the same or an immediately comparable scale in

Table 5. This scaling of the material, an underlying principle of morphological examination, provides the basis for an accurate visual examination of proportional relationships, building detailing, and integration into the façade. It also facilitates a more discerning difference among changes in height, width, and solid-to-void ratio from one building context to another.

As shown in

Table 5, the comparative morphological examination encompasses eight case studies spread across mosques, madrasas, hospitals, and caravanserais in Egypt, Syria, Morocco, and India. The scale reference, material, pattern type, and function are noted in each entry, underlining the variety of design strategies. For instance, the extensive geometric and repetitive grid patterns of wooden panels in the Al-Azhar Mosque and Wikala of Baazar’a stress privacy and shading, and the small stone openings in the Nur al-Din Bimaristan are focused on ventilation. The pattern vocabulary shifts from purely geometrical compositions, such as in the Al-Azhar Mosque, to subtle floral patterns, such as the Nur al-Din Bimaristan Hospital.

By analyzing all photographical material through comparable dimensions, further functional and aesthetic distinctions become more obvious. These include the amount of ornamentation, latticework complexity, and the interrelation of decorative patterns and climatic performance. In madrasas, mashrabiyas alternate simple and complex geometry in an effort to balance privacy and light, but in caravanserais they lean toward the simpler geometrics in order to provide airflow to travelers’ quarters. The table also illustrates the importance of materiality to perform and enhance cultural values—carved wood affording fine detail and adaptability, but stone lattices suggesting permanence and monumental scale. This table enhances the veracity of such a cross-typology comparison but further solidifies the relationship of morphological attributes with the architectural, cultural, and climatic settings in which these mashrabiyas are set.

From a stylistic perspective, the comparative synthesis in

Table 5 also reveals recurring architectural morphemes that define the identity of the mashrabiya across regions and building types. These include the modular repetition of geometric units, the alternation of dense and open lattice segments to modulate privacy and airflow, and the integration of ornamental borders framing the lattice field. Variations in these morphemes—from the finely pierced star polygons in Moroccan examples to the vegetal tracery in Indian jalis—not only express local aesthetic traditions but also demonstrate adaptive responses to climatic, cultural, and functional needs.

6. Conclusions: Enduring Relevance of the Mashrabiya for Contemporary Sustainable Design

The analysis confirms that regional context significantly influenced the adaptation of mashrabiyas, addressing the core research question posed in this study. Comparative analyses of the eight case histories—with choices from four major public building types spanning different regions—verified that the mashrabiya was a remarkably adaptable architectural device throughout the Islamic world. Regardless of its adoption into spaces for worship, teaching, healing, or reception, it never failed to satisfy climatic needs while simultaneously reflecting regional design customs and cultural ideals. Regardless of the diversity in scale, building materials, or stylistic expression, its ultimate functions remained intact in all instances. This consistency reflects the mashrabiya’s input not only as a climatic device but also as a powerful architectural language.

Although limited to two case studies (from different countries) for each type of traditional public building, the comparative analysis carried out here has shown that, in most of the cases considered, the mashrabiya served multiple functions.

In spaces dedicated to worship and Qur’anic education, such as mosques and madrasas, mashrabiyas allowed students in upper-level rooms to observe activities in the courtyard (lessons, prayers, movements). Beyond their practical role in regulating light, the filtered illumination through the intricate geometry of the mashrabiya could carry deeper meaning. It created patterns of light and shadow, contributing to an atmosphere of serenity, mysticism, and reflection. Although not its primary function, the lattice structure could also provide some degree of sound attenuation from the courtyard or the street, fostering a quieter setting for study or prayer.

In spaces dedicated to the care of people (bimaristans), the mashrabiya, thanks to its ability to regulate temperature, allowed for effective yet non-invasive cooling, ensuring thermal comfort for patients. Beyond air regulation, the filtering of light helped create a relaxing environment, ideal for rest and well-being in treatment spaces that required a certain level of discretion.

Good air circulation was also essential, particularly for hygienic reasons.

In spaces dedicated to hospitality (caravanserais), the mashrabiya served specific functions to satisfy the needs of merchants and travelers in transit. While the primary purposes were always guaranteed, they took on different characteristics. Privacy for Merchants and Their Goods: Caravanserais hosted merchants, who often traveled with valuable goods. The mashrabiyas in the upper-floor rooms allowed for total safety. Observation of the Courtyard Activities: The central courtyard of the caravanserai was a vibrant hub of commercial activity, featuring the loading and unloading of goods, negotiations, and the movement of people and animals. The mashrabiyas allowed merchants to discreetly observe the courtyard and its activities, gathering precious information for their business without needing to come down or appear openly at a window. Travelers, often arriving after long and exhausting journeys, needed comfortable spaces to rest.

From the comparative analysis of the selected case studies, the following conclusions can be drawn regarding the mashrabiya as an architectural element. In terms of function, the mashrabiya consistently serves similar purposes. However, these are expressed with subtle yet significant variations depending on the function of the public building. In mosques, for instance, the interplay of light filtered through the mashrabiya acquires a spiritual meaning. In madrasas, it provides adequate natural lighting for study spaces while preserving privacy. In buildings dedicated to healing, the goal is to create soft lighting that promotes rest and recovery for patients. Finally, in a caravanserai, the lighting is designed to support commercial activities. Even the concept of privacy was adapted to the building’s function: the kind of privacy required by worshippers in a mosque was quite different from that needed by merchants staying in a caravanserai. Ultimately, it can be said that the core functions of the mashrabiya have remained consistent over time. However, when it comes to its form—or more precisely, the design and materials used—geographic and cultural influences played a significant role.

Comparing designs within the same building typology can reveal whether there are recurring geometric or stylistic principles that transcend regional specificities and help define a recognizable visual identity of the mashrabiya in traditional Islamic public architecture.

The discussion of the case studies has highlighted key commonalities and divergences in the form, materiality, and cultural connotations of the mashrabiya across different public building types. These observations confirm that while the mashrabiya’s climatic and privacy functions remained consistent, its material expression and symbolic resonance were closely shaped by regional resources, artisanal traditions, and cultural priorities. It is also important to note how, over time, the mashrabiya has evolved into a meaningful symbol of cultural belonging for the Islamic community.

Furthermore, this study suggests that, beyond functional parameters, mashrabiyas can be understood as instruments of cultural transmission—objects through which societies encode values such as privacy, modesty, and artistic identity. As contemporary architects explore climate-responsive strategies, revisiting and reinterpreting such vernacular elements could yield both ecological and cultural benefits.

This research’s findings offer insightful implications for modern architectural practice, particularly in dry and semi-arid climates, where passive climate control is a crucial design consideration. Classical mashrabiya systems provide an enduring paradigm for energy-efficient architecture. By redesigning such typologies with contemporary materials—such as engineered wood, metal composites, or smart solar screens—and combining them with high technologies, such as automated louvers and adaptive façades, architects can create hybrid systems that combine tradition with innovation. Such practice not only improves environmental performance but also asserts cultural identity in built form [

53]. Public facilities—such as schools, libraries, healthcare facilities, and civic centers—are ideal for such reinterpretations, as they serve multifaceted communities and can bridge the past and the present, both symbolically and practically. The adoption of mashrabiya-inspired devices in such spaces permits a significant continuity of Islamic architectural tradition while responding globally to mandates on sustainability, climate resilience, and contextual design. Bringing together the findings and reflections presented in the conclusions and the final discussion, this study demonstrates that the mashrabiya remains a powerful architectural element where environmental functionality, cultural symbolism, and formal aesthetics intersect. The comparative analysis, as consolidated in

Table 5, illustrates how its morphological diversity—in scale, material, and ornamentality—reflects both local adaptation and shared heritage principles. By linking symbolic and cultural interpretations with formal and climatic performance, this research confirms the mashrabiya’s enduring relevance for contemporary design. This integrative perspective reinforces the research objectives and offers a clear framework for architects seeking to embed tradition within innovative and sustainable architectural practices

7. Study Limitations and Directions for Further Research on Mashrabiyas

The major limitation of this research is the scarcity of available documentation. One limitation of this study concerns the absence of detailed building elevations and internal sections for the analyzed case studies. As

Table 5 offers a metric scale in the photographic documentation to enable the formal comparative analysis to take into account the scale of the mashrabiyas in varying building types and geographic locations, the prohibitive absence of accurate architectural drawings hinders the performance of a fully dimensioned comparative study of proportional relations vis-à-vis the host buildings. This weakness mainly results from limited access to some sites and the absence of available geometrical drawings or metric surveys. In future research, this gap may be bridged by conducting dedicated on-site measurements, photogrammetric surveys, or archival research to provide scaled drawings. These data would facilitate more in-depth comparative studies of the mashrabiya in reference to building form as a whole, façade composition, and interior spatial organization, thus enhancing the morphological and typological knowledge derived in the current study. This constraint has not always allowed for the study and comparison of buildings from the same period. However, since the mashrabiya has been reintroduced and reinterpreted in contemporary architecture, primarily within the context of public buildings, it seemed appropriate to explore—despite the aforementioned limitations, and with full awareness that this represents only an initial investigation—the lesser-known applications of this distinctive architectural element in historic public buildings. This study does not claim to be exhaustive but rather aims to contribute to a more holistic understanding of the Islamic architectural heritage. Starting from a broader approach, future research could focus on the role played by the mashrabiya in both residential and public buildings, exploring the relationship between its use in traditional architectural examples and its application in similar types of modern buildings.