1. Introduction

In the past decade, there has been an increased interest in safety and well-being in student training in archaeological fieldwork contexts (e.g., [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]), particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Training excavations are seen as unique educational settings in which student well-being may potentially erode more easily than in traditional classroom environments [

2]. Participants—both students and directors—may be exposed to physical labour, outdoor conditions, social relationships, and local living conditions they are unfamiliar with, which may lead to unexpected physical and mental responses and behaviours. Projects obviously differ from one place to another, but fieldwork conditions can be harsh and have even been experienced as creating “an atmosphere where students do not feel safe or empowered to approach field directors when they witness or experience forms of harassment and assault” [

5]. Moreover, it is known that ng adults, in particular, who participate in field research face a risk of mental health challenges [

6].

By contrast, there is also evidence of well-being improvements among participants in archaeological activities and excavations (e.g., [

1,

7,

8]). Archaeological fieldwork programmes such as Project Nightingale and Waterloo Uncovered demonstrated, for instance, impressive positive results on feelings of well-being among military veterans [

9,

10]. Archaeological activities with excluded groups, like homeless people, provided evidence for positive impacts on personal development as well [

11]. Additionally, the Human Henge study found that immersing participants with mental health issues in a Neolithic landscape improved their well-being [

12]. Studies conducted by our institution have also shown positive impacts on aspects of well-being, like social cohesion and feelings of belonging, albeit with different groups of participants [

13,

14].

It is because of the acknowledged risks of student fieldwork training that more attention is being paid to in-field due diligence [

4]. Yet, with only one case study—from the United Kingdom—measuring mental student well-being during a training excavation [

1], there is still a need for systematic, empirical studies to direct future pedagogical practice in fieldwork training of students. This case study intends to contribute to this by adding to the body of evidence through evaluating self-reported positive and negative emotions during a field school training. This field school is organised each spring for first-year bachelor students by the Field Research Education Centre (FREC) of Leiden University’s Faculty of Archaeology (Netherlands). It is an obligatory course as part of the curriculum for undergraduates

1. In 2020, our archaeology field school could not be run due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown of higher education in our country. In the spring of 2021, the COVID-19 measures were temporarily eased, and the faculty’s field unit team, together with its private sector partner Archol BV, made a huge effort to organise once again a field school for its first-year students, albeit with special conditions.

Student well-being was an important argument for organising this field school again, since it was generally acknowledged during the COVID-19 pandemic that students (and teachers) were struggling with the periods of education lockdowns, during which universities were forced to move from face-to-face teaching to online platforms. It introduced substantial periods of solitary studying at home, which disrupted students’ study routines and caused cultural isolation. At the time, it was in the early days of the pandemic, and no evidence-based studies on the impact on archaeology students were available. However, there were anecdotal signs of such struggles, like loneliness and depression. Moreover, a mental health monitor at Erasmus University Rotterdam (Netherlands) indicated that a disturbing 51.06% of the surveyed students reported below-average mental well-being, with 47.9% experiencing moderate to severe depression [

16]. In particular, bachelor’s students exhibited a lower level of satisfaction with life, lower self-esteem, and higher levels of stress and depression [

16]. Furthermore, it was known that in higher education in other domains, blended learning and online teaching—despite their many advantages for some in terms of flexibility, humanising, breaking down barriers [

17], and empowerment [

18]—faced challenges such as stimulating interaction and fostering an effective learning climate [

19]. It was also observed over decades that in online teaching in higher education, dropout rates tend to be higher than in on-campus programmes (e.g., [

20,

21,

22]), possibly due to a lack of social connections with teachers [

23] and peers, and a lack of learning support.

When the Field Research Education Centre (FREC) of Leiden University was again allowed to organise a field school during the COVID-19 pandemic, we used this unique opportunity as a case study to evaluate how students would develop in terms of self-reported psychological well-being. Based on both the reported risks of field training and the positive evidence of well-being effects, we developed a hypothesis that students could benefit in terms of social and psychological well-being from being outside and conducting archaeological training in a socially engaging environment. We applied a narrow hedonic approach to mental well-being, while understanding the complexity of defining mental well-being [

24], which differs from one research field to the another, and acknowledging that mental well-being is only one aspect of overall health and well-being, that it is multi-dimensional—encompassing emotional, psychological, and social factors—and that it can be experienced differently from one person to the next

2. According to the American Psychological Association, hedonic well-being is the type of happiness or contentment that is achieved when pleasure is obtained and pain is avoided

3. As a method, it focuses on measuring the presence of positive emotions (e.g., happiness) and the absence of negative emotions.

2. The Case Study

The field school of 2021 was designed as a two-week course. The first week (five working days) took place at an excavation site in the rural environment of Oss, in the southern part of the Netherlands. The excavation was conducted in a real-life setting, commissioned by the local authorities. During the second school week, the students worked for five days in the laboratories at the Faculty in Leiden.

Since the number of COVID-19 infections was still high in the Netherlands and students had not yet been invited to be vaccinated, the circumstances for the 2021 field school were extraordinary. The university board gave permission only under strict conditions and compliance with a COVID-proof protocol (including social distancing, frequent medical testing, and strict hygienic measures). A total of 170 students participated in the field school in 2021, distributed over six weeks. Thus, we received around 30 students a week. This was a larger group than usual because it consisted of two bachelor’s cohorts—those who started their studies in 2020 and the first-year students of 2021. The group consisted of students around the age of twenty, both males and females, from over twenty countries across the globe (

Table 1).

The students all arrived at the excavation on a Monday morning and stayed overnight in small tents at a nearby camping ground for four days. They worked until Friday afternoon, when they returned to their home base for the weekend. Due to the social distancing requirements of the Dutch government, students and staff members could not be transported in cars or buses and had to cycle about 13 kilometres back and forth between the campsite and the excavation.

The field school was taught by a team of four to six faculty members, assisted by one or two post-docs or PhD students. Due to the unusual circumstances, the team’s composition differed from one week to another. The staff members would also stay overnight at the campsite in a large guest house.

During the field school, the students first received general instructions. During the week, they participated in different activities in small groups, like measuring, coring, drawing profiles and features, analysing features, and documenting finds (

Figure 1). After the first working week in the field, the students continued training at the Faculty of Archaeology from Monday until Friday. At the faculty, another team of staff members guided the students in exercises related to the analysis of the collected data and material (finds, features, and samples). The final exercise included dissemination work. After the second week of lab work, the students were expected to hand in a report on the entire field school experience, which would be assessed and graded.

3. Research Method

In order to measure student well-being development, a quantitative survey was set up based on an existing and recognised well-being measurement tool, the Museum Well-being Measures Toolkit [

25,

26]. This toolkit was developed by researchers from University College London for museum staff involved in outreach and participation projects and is still the most commonly used measure today, including for activities in natural settings [

27]. It evaluates the impact of museum activities on the self-reported (subjective) psychological well-being of participants by measuring mood levels at specific intervals. It consists of a set of scales, known as the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), for psychological well-being, which measure the mental state of the individual through the presence of positive and negative moods and emotions. The PANAS scale was originally developed by Watson, Clark, and Tellegen [

28].

In order to measure these moods, participants are asked to self-report their moods and emotions on a 5-point Likert scale. They typically do this prior to and immediately after an activity or intervention. In this way, one can measure mood changes over time, with the hypothesis being that this change in mood relates to the activity if moods are measured shortly before and after this activity [

28].

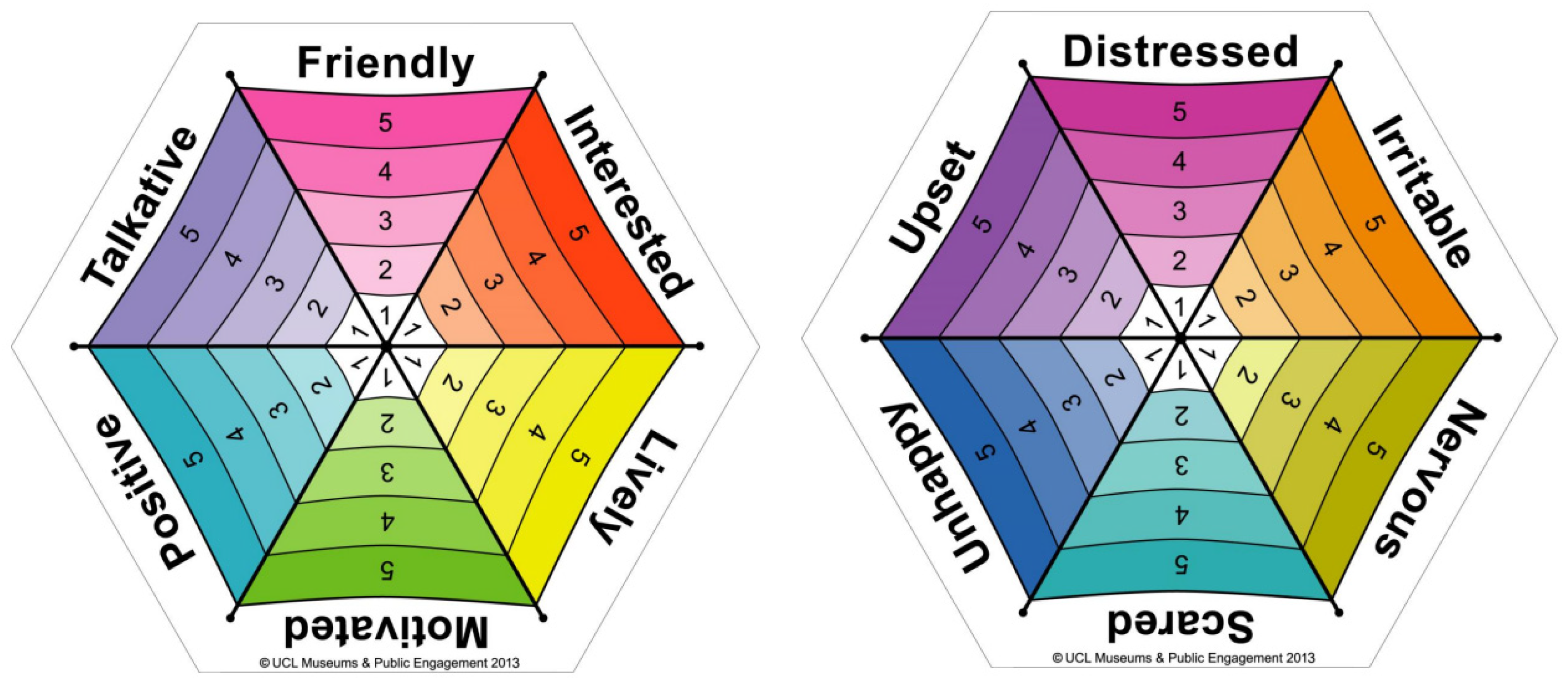

The tool can either be used as a colourful, hexagonal-shaped well-being umbrella (

Figure 2), on which participants circle the number (from 1 to 5) that represents their mood level, or as a text-based questionnaire in which one selects the description that best represents their mood. For our survey, it was used as a questionnaire with words because the textual expression of the ratings is clearer than an umbrella with numbers, and easier to process with large numbers of participants. Moreover, we selected the version on positive moods that was specifically designed for younger adults, with the moods and emotions they seemed to respond best to, such as feeling ‘friendly’, ‘interested’, ‘lively’, ‘motivated’, ‘positive’, and ‘talkative’ [

25].

We asked the students to report their moods and emotions on four different occasions with specific intervals. The first measurement phase was at the start of the field school, on Monday morning, just after arriving at the excavation premises. The research objectives, the ethical protocol, and the survey were briefly explained by a team member, and students had the chance to fill out the survey during their lunch break. The second occasion was at the end of the excavation week, after five days of outdoor training in the field, just before leaving the excavation and going home for the weekend. The third phase was at the start of the following Monday, with lab work in class at the faculty building. The fourth and final measurement was on Friday afternoon, after one week of lab work activities in class at the faculty building.

We asked how the students felt at these four moments regarding six positive emotions (interested, lively, motivated, positive, talkative, and friendly) and six negative emotions (distressed, irritable, nervous, scared, unhappy, and upset). The options on the 5-point scale were as follows: 1—not at all; 2—a little bit; 3—fairly; 4—quite a bit; and 5—extremely. We used the original English version because we have an international classroom, and all our teaching is in English.

The survey was conducted fully anonymously. For privacy reasons, students were asked not to fill out their names but to use a unique numerical identifier, which they could remember (and reuse for all survey forms) and which would guarantee their anonymity. Students were not obliged to participate and could opt to return the forms without completing them.

4. Results

The students handed in 420 filled-out forms (out of the ca. 620 we distributed). This is a response rate of 68%. The response rates differed per phase; we received 106 forms for phase 1, 109 for phase 2, 108 for phase 3, and 97 for phase 4. In total, 311 forms were filled out by students of Dutch nationality (74.1%), and 98 (23.3%) by international students (

Table 1). We counted 21 nationalities, with 11 respondents not indicating their home country. While the majority of international participants were from Europe (including the United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Poland, Germany, Italy, France, Romania, Bulgaria, Spain, and Portugal), they represented a diverse range of countries, including the USA, Mexico, Chile, China, Russia, India, Sri Lanka, Philippines, and Indonesia. In total, 189 survey forms were filled out by students who self-identified their gender as ‘female’ (45%), 193 as ‘male’ (46%), and 32 (7.6%) as ‘non-binary’ or ‘neutral’. Another six forms said ‘none’.

In order to be able to follow individual students during the four phases and analyse the development in their well-being ratings, we asked the survey participants to provide a self-invented code on each filled-out questionnaire. In this way, the students remained anonymous, while we could link a series of measurements to individual participants and apply a significance test. A substantial number did not fill out an identifier on all four forms and had to be excluded from this part of the analysis, leaving a total of 54 students who could be included in the development analysis. The other forms were only used to gain insights into the general well-being levels reported at the start and end.

4.1. Ratings of Positive and Negative Emotions in Phase 1

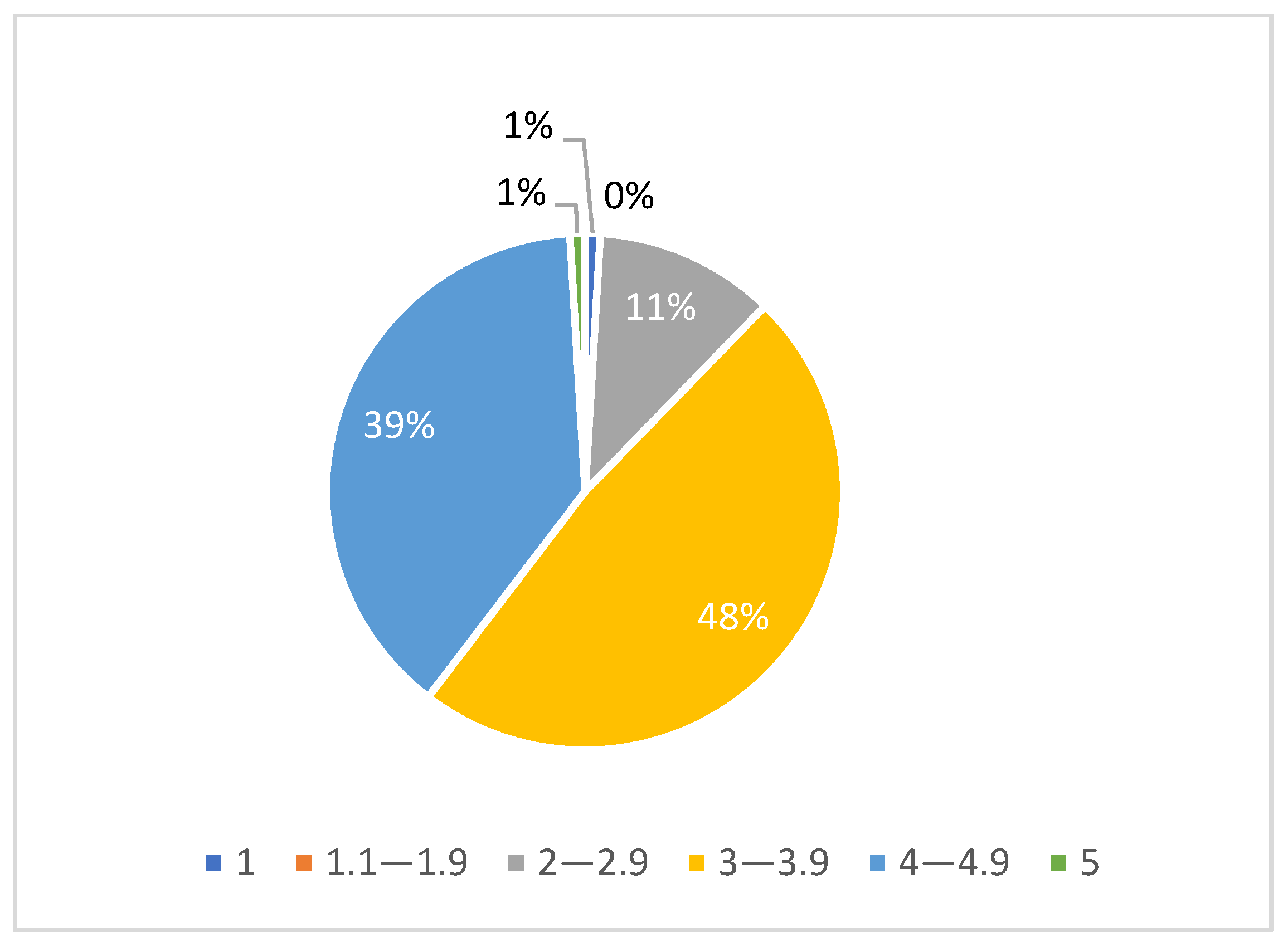

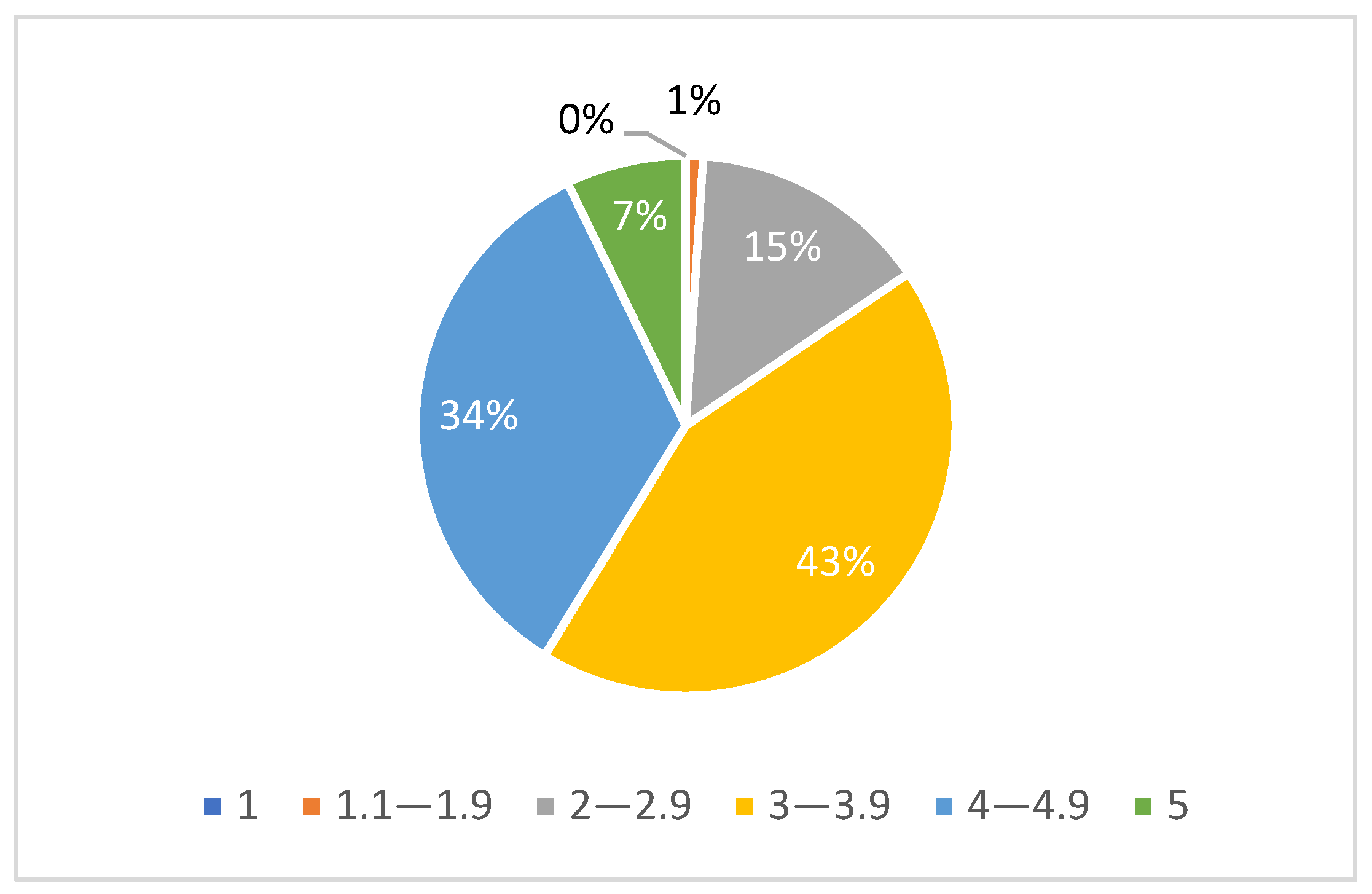

The calculated averages of the emotion ratings from all 106 survey forms that the students handed in at the first measurement occasion showed a rather high level of positive emotions and a fairly low level of negative emotions (

Table 2). The highest averages for the positive moods were for ‘feeling interested’ (M 4.15, SD 0.75) and ‘feeling friendly’ (M 3.97, SD 0.86). These relatively high averages imply that the students felt these positive moods ‘fairly often’ (3) to ‘quite a bit’ (4). The lowest scores for the positive emotions were for ‘feeling lively’ (M 3.25, SD 1.01) and ‘feeling positive’ (M 3.29, SD 0.94), but they still felt these emotions, on average, fairly often. At this phase, the median was 4 for the positive emotions of feeling ‘interested’, ‘motivated’, ‘positive’, and ‘friendly’; and 3 for feeling ‘lively’ and ‘talkative’. The largest group (48%) had a mean rating between 3 and 4 for all six positive emotions (

Figure 3), and nearly all (87%) scored between 3 and 5. One student had the highest possible score of 5, and another had an extremely low score of 1, while 12 individuals scored between 2 and 1. Thus, while most felt quite okay, 13 students reported low psychological well-being levels in terms of positive emotions

4.

In terms of negative emotions, the students gave ‘feeling upset’ the lowest rating at the start of their fieldwork activities (M 1.15, SD 0.40); the second lowest was ‘feeling scared’ (M 1.35, SD 0.66) (

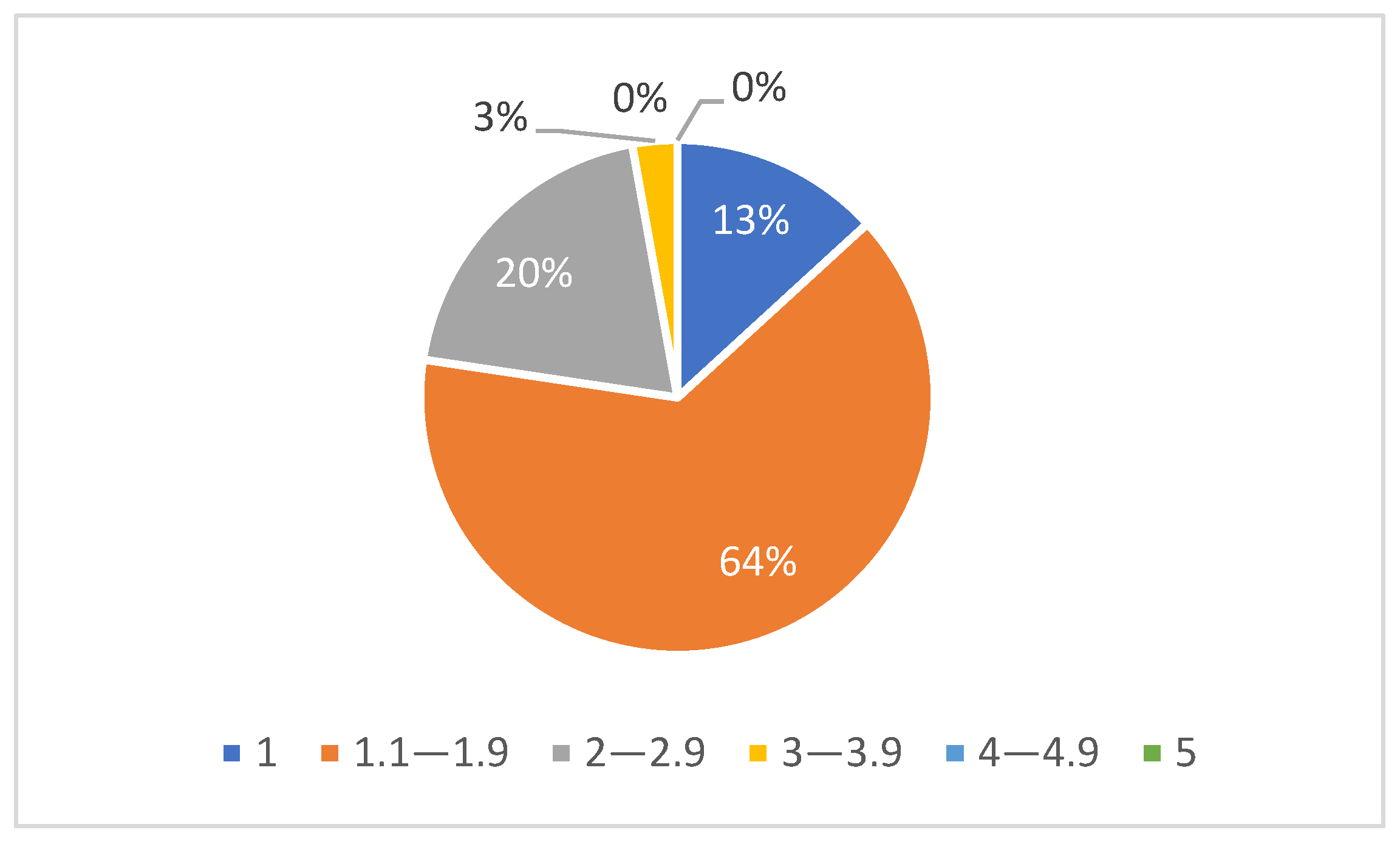

Table 2). The highest ratings for negative emotions were reported for ‘feeling nervous’, with a 2.09 average score (SD 1.02). All other negative emotions were, on average, rated below 2 (the median was 1 for almost all negative emotions in phase 1, except for ‘feeling nervous’, for which the median was 2). This means the students felt most negative moods ‘almost none of the time’, which is a positive signal.

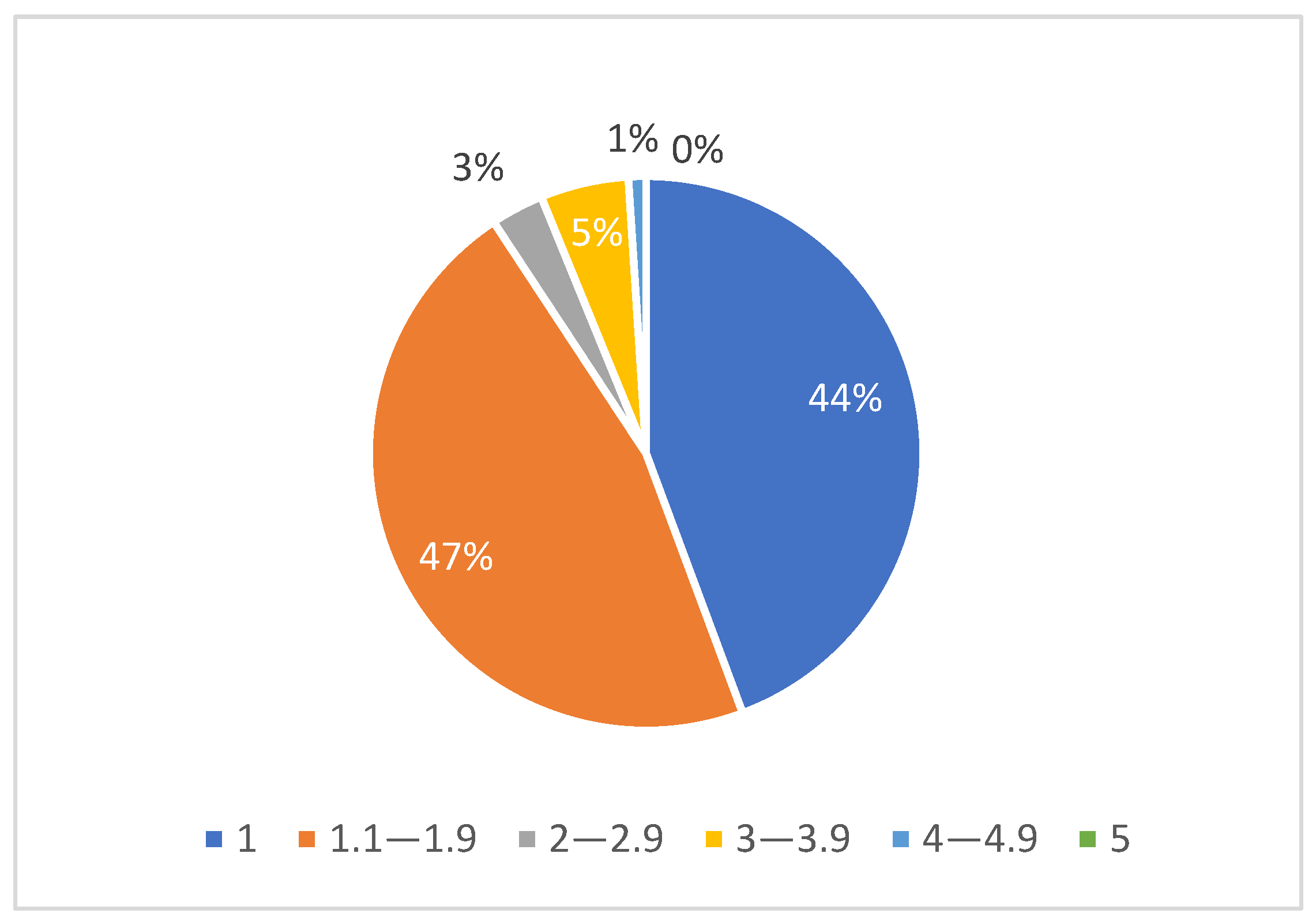

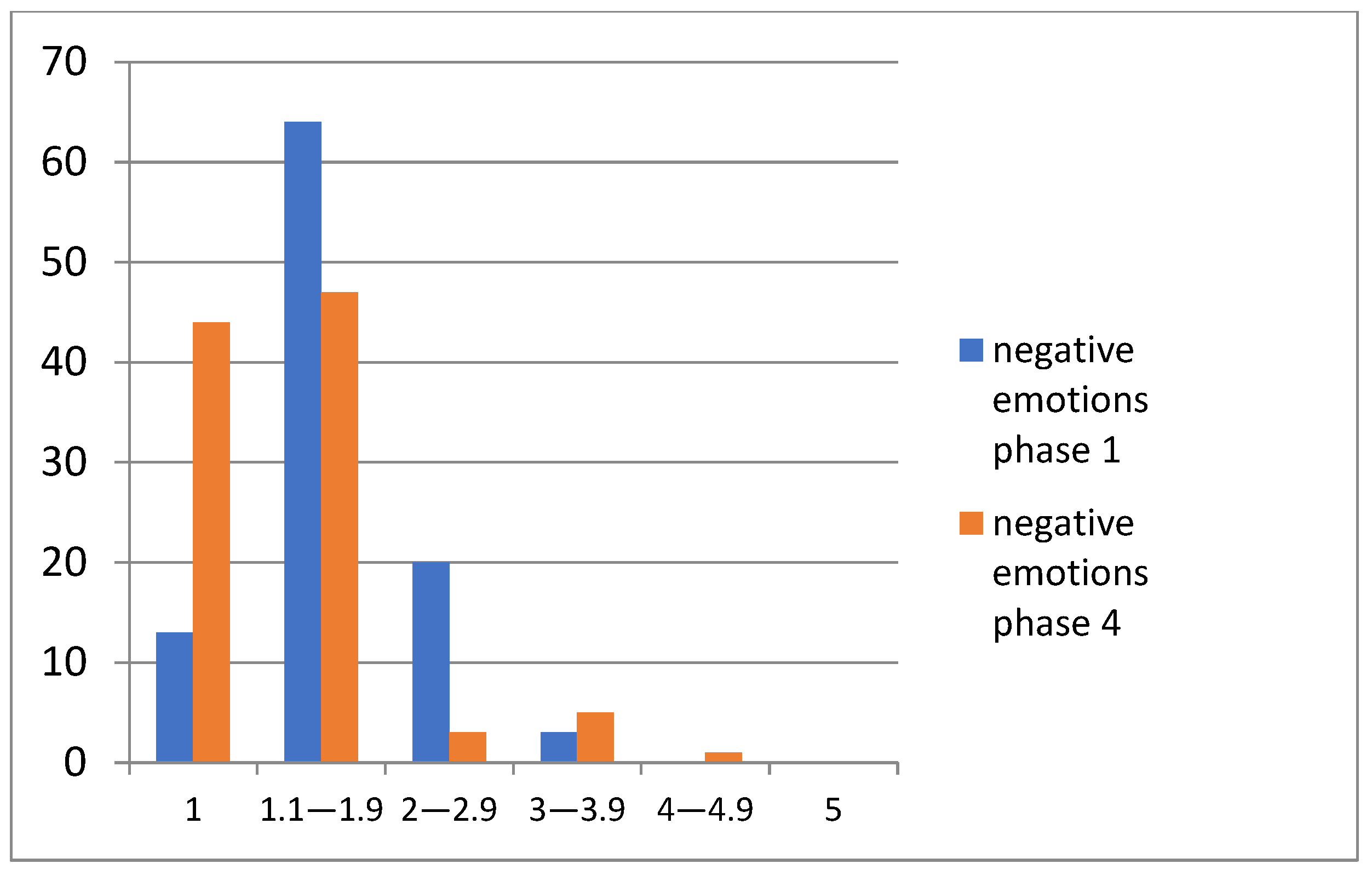

Fourteen students (13%) reported not feeling any negative emotions; they did not feel nervous either (

Figure 4). A majority (64%) had an average score for all negative emotions between 1 and 1.9. This is a positive signal. A small group (20%) had an average between 2 and 2.9, and only three students scored a 3. No one had an average of 4 or more. None reported a high level of negative moods (>3) in combination with a low level of positive moods.

4.2. Distribution over Time

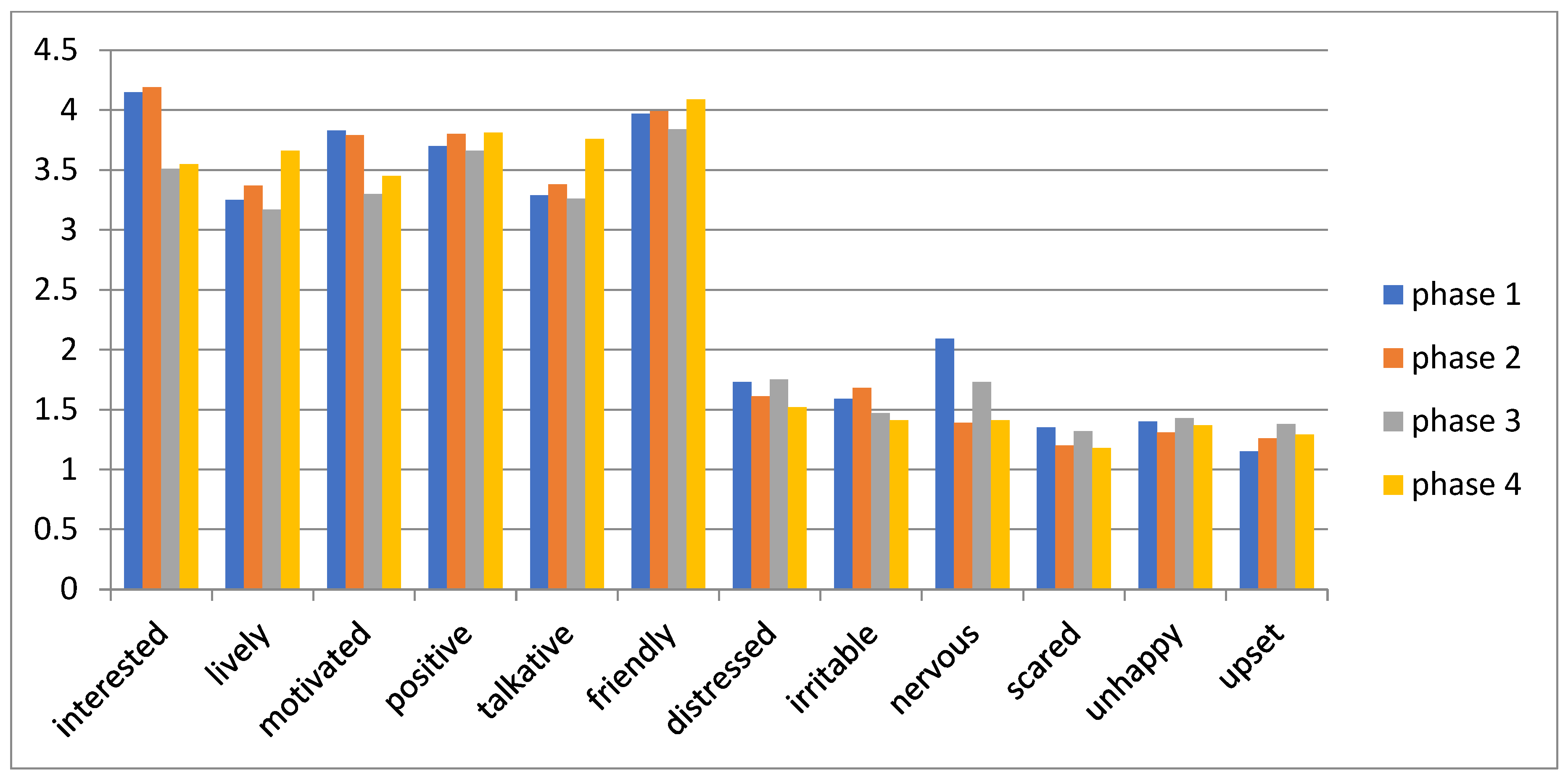

Figure 5 shows how the average ratings for all motions changed for all four measurement intervals during the field school. It visualises how the averages for all emotions fluctuated from one phase to another, but overall remained quite high for the positive emotions and rather low for negative emotions.

4.3. Ratings of Positive and Negative Emotions in Phase 4

At the end of the field school (phase 4), the average ratings for positive emotions decreased for ‘feeling interested’ and ‘feeling motivated’ (0.60 and 0.38, respectively); all other emotions improved (

Table 2). The rating with the highest percentage was between 2 and 2.9 (

Figure 6). The percentages of the highest ratings (5) on positive emotions increased slightly, from 1% in phase 1 to 7% in phase four (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7); the other higher rating levels (3 and 4) showed a small decrease, while the lower ratings (2 and 1) showed an increase (

Figure 7).

For negative emotions, lower ratings were given for all emotions, implying these emotions had all improved. In particular, ‘nervousness’ decreased strongly (

Table 2). In this phase, the median for feeling ‘lively’ and ‘talkative’ was 4, while the other positive emotions remained at the same level.

Overall, the percentage of low ratings (level 1) on negative emotions increased from 13% in phase 1 (

Figure 4) to 44% in phase 4 (

Figure 8). The ratings between 1.1 and 1.9 decreased from 64% to 47% (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), implying an improvement. However, a few students reported higher negative ratings as well (> 3).

A Welch’s

t-test was conducted to calculate statistical significance for the changes between phases 1 and 4 (

Table 2)

5. It turned out that only a few were statistically significant. With regard to positive emotions, interest (

p < 0.001) and motivation (

p 0.010) decreased significantly, whereas ‘talkative’ increased (

p 0.001). For negative emotions, only nervousness decreased significantly.

5. Development in Individual Well-Being

Secondly, the development in well-being for the group of 54 students who provided ratings for all phases was analysed. Of these, 46.3% were male and 42.6% were female. A majority (74.1%) had Dutch nationality (

Table 3). For this group, we again calculated averages (

Table 4) and applied a Wilcoxon paired sample test to calculate significance for the change in moods (

Table 5)

6.

Regarding positive emotions (

Table 4), the calculated averages for ‘feeling interested’ remained the same from phase 1 to 2, but decreased significantly (

z < 0.001) at the start of the second week of lab activities (phase 3). Ratings then stayed the same until the end of the field school (phase 4). Thus, this emotion showed an overall decline (phase 1 to 4) of 0.61, which is statistically significant (

Table 5). A similar pattern occurred for ‘feeling positive’, except that this decline was smaller and not statistically significant. For ‘feeling lively’, the ratings also increased from the start to the end, but mostly (and significantly) during the second week. The same was the case for ‘feeling friendly’, except that this effect was slightly less and, thus, not statistically significant.

Apart from feeling less interested, students also felt gradually less motivated; in particular, at the start of the second week (phase 3), the decline was statistically significant (z 0.045). It slightly increased again during the last week, but not significantly. So, overall, a statistically significant decline was reported for their motivation from the start of the field school until the end.

Overall, the ratings of three emotions decreased (feeling interested, motivated, and positive)—two significantly—and the ratings of three increased (feeling lively, talkative, and friendly), one of which was significant (talkative).

For negative emotions (

Table 6 and

Table 7), the calculated averages for ‘feeling distressed’ slightly declined from phase 1 to 2, and ended even lower in phase 4 (with a total of—0.10), but the Wilcoxon

t-test demonstrated no significance (

Table 7). Irritability decreased as well, mostly between phases 1 and 2, but this was not statistically significant either. Nervousness received the highest ratings at the start (1.92, on average) and decreased the most out of all negative emotions (by −0.64). It already diminished after the first week and once more after the second week. At the start of the second week, it increased significantly again. The positive change from phase 1 to 4 was statistically significant as well (

Table 7). The emotion ‘feeling scarred’ had the second lowest rating at the start (1.22) and showed the second highest decrease; its average rating improved by −0.11. It ended up having the lowest rating at the end. The only negative emotion for which the rating increased between phases 1 and 4 was ‘feeling upset’. It started with the lowest rating (1.11) and was reduced by 0.17, but again, the Wilcoxon

t-test demonstrated no statistical significance. Overall, all negative emotions except one (feeling upset) showed an improvement, of which nervousness and feeling scared had significantly decreased.

5.1. Individual Benefits

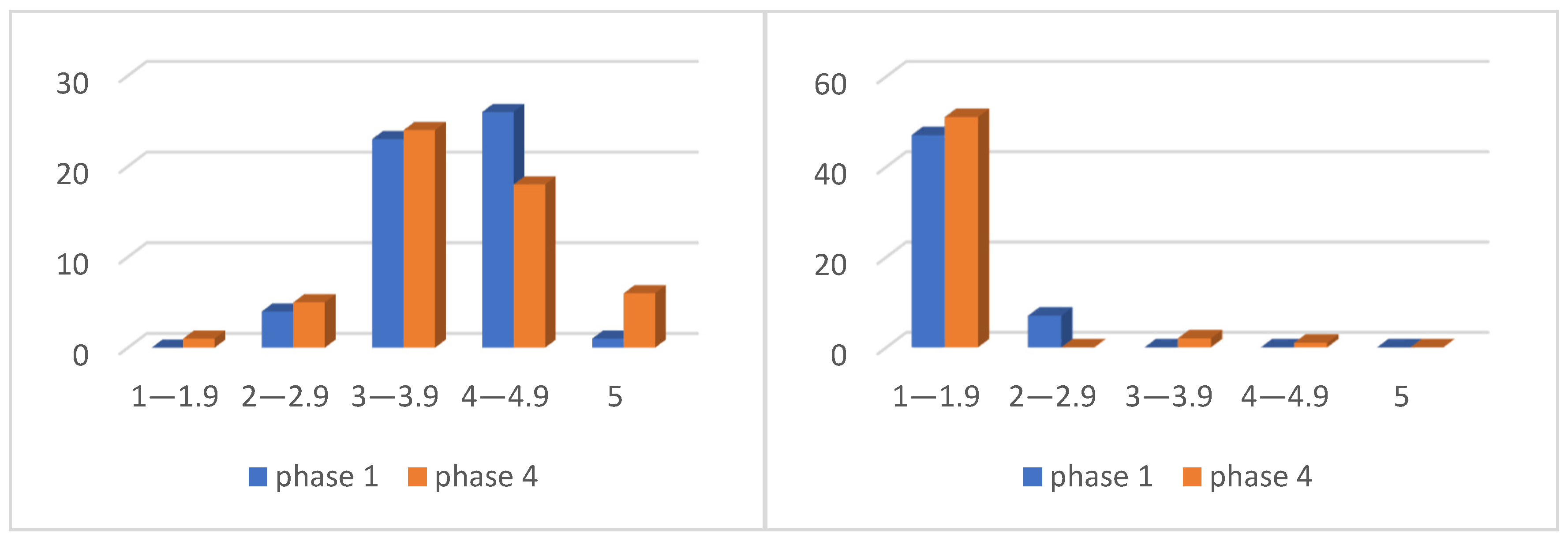

While the group as a whole showed some changes in some emotions from the start until the end, we also aimed to learn to what degree individuals gained from this activity. For this, we looked in more detail at the individual scores for the average ratings of both positive and negative emotions and whether these changed from phase 1 to 4. At the start, the largest group (26) rated their positive emotions at around 4 (

Figure 10). Low ratings hardly occurred, with only 4 indicating their positive emotion level ranged between 2 and 2.9. This means that the majority of these participants seemed to have felt quite well. At the end, scores were slightly more distributed, with a majority scoring between 3 and 3.9. For 46%, positive ratings decreased (

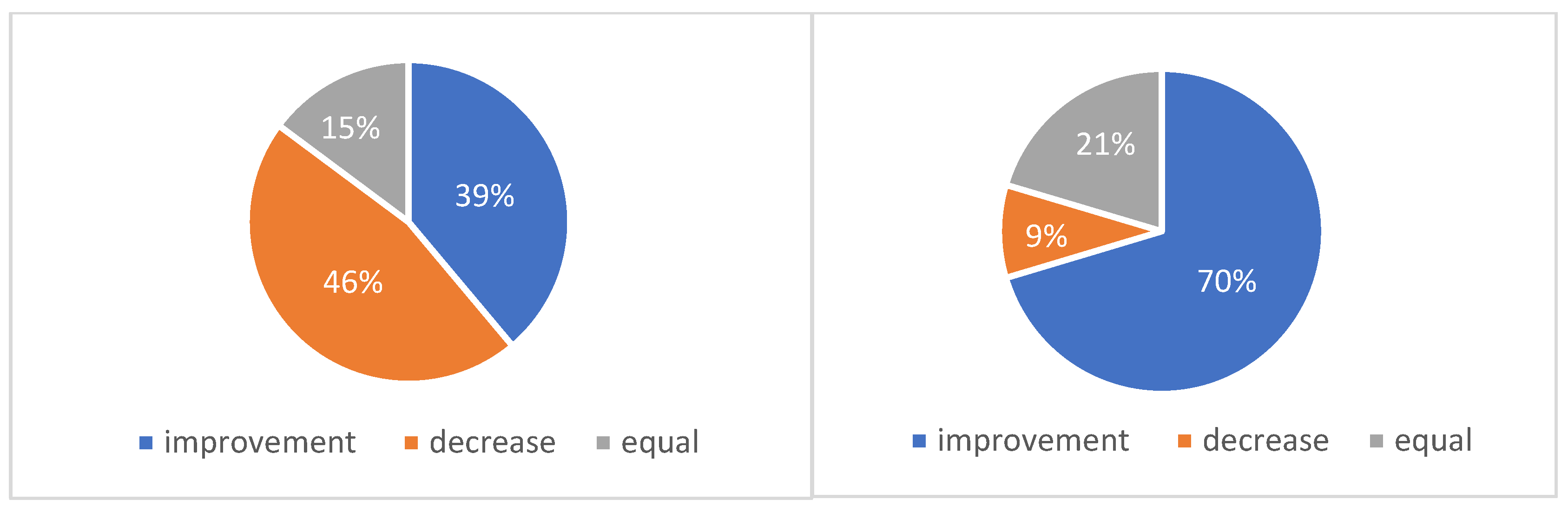

Figure 11), whereas 39% reported an improvement (15% remained the same). This implies that a majority did not gain in terms of positive emotions, and we know from the above analysis of emotions that this is mostly related to reduced interest and motivation.

Concerning negative emotions, a large majority of the participants reported an average rating at the lowest level (between 1 and 1.9) for phase 1, and no ratings above 2. This implies that negative emotions were quite low for this group. At the end, even more participants rated at the lowest level, while the higher levels were scored as well. Overall, the ratings improved for 70% and decreased for 9%. This implies that most experienced little negative emotions and even less toward the end. Thus, they gained from the activity in terms of well-being, mostly because nervousness levels and feelings of fear were reduced.

5.2. Participant Remarks

The positive and negative well-being umbrella method assumes that there is a relationship between the activity and the reported mood. However, this does not explain or provide indications concerning specific reasons for positive or negative changes. Thus, participants were invited to share comments via the survey form to share what contributed to their positive or negative emotions, but only a total of 10 students used this opportunity. One person indicated in the last phase (during lab work) that assignments with deadlines made them feel negative. In contrast, the excavation activities had added to this person’s mental well-being. This student was the only one complaining about deadlines. Two others complained in the comments about the weather being too hot. For three students, the type and quantity of the food that was provided in the first week was a reason to comment. These were international students who may not have been used to eating Dutch meals. Three individuals with Dutch nationality expressed their happiness and gratitude at the end of the excavation week and thanked the organisers of the field school for providing the experience.

6. Interpretation and Discussion

The first observation that can be derived from this case study is that, on average, at the start, all participants in the field school reported rather high average ratings on positive moods and low ratings on negative moods. With 88% of all students rating positive emotions between 3 and 5, and 77% rating negative emotions at 2 or less at the start of the first activity week (measurement phase 1), their mental well-being level was quite high. With 84% still rating positive emotions between 3 and 5 upon completion of the second week (phase 4), and 91% rating negative emotions at 2 or less, it can be argued that the self-reported overall well-being score for this group was no reason for concern. These self-reported mental well-being levels did not indicate that a large group was, at that moment, suffering from severe to moderate depression, unlike the students at the nearby Erasmus University in Rotterdam [

16].

At the start, the positive emotion scoring highest was ‘feeling interested’, and the lowest were ‘feeling talkative’ and ‘feeling lively’. Maybe these relatively lower ratings were caused by the past lockdown period, during which they only had online classes and very little opportunity to socialise with peers, but this is an assumption.

As said, the reported ratings for negative emotions were already low at the start of the field school, which supported the conclusion that the group as a whole seemed to be feeling quite well. The fact that the strongest negative emotion was ‘feeling nervous’ was not surprising. It is known that mandatory training may cause stress among students (e.g., [

31,

32]; this was seen in Sayer’s study [

1] as well. In our case, the students’ nervousness may have been related to—or enhanced by—some end-of-year stress, as half of the group was running toward the end of their first year of studies and needed good results to pass. This implied that their performance during field school would affect their final grade and, thus, their entry into the second year. The stress or anxiety that this normally evokes may have been more substantial in 2021 due to the effects of the lasting COVID-19 pandemic and the abnormal, unprecedented educational circumstances the students had been in.

The observation that the level of nervousness dropped significantly during the field school can be considered a positive result; it happened with the entire group, and with 54 students whose well-being could be monitored during the entire field school. Nevertheless, it is important to realise that participating in archaeological activities not only has the potential to improve one’s mood but can also (perhaps temporarily) evoke or aggravate negative emotions such as nervousness. Since academic pressure can have a direct impact on the mental well-being of students (e.g., [

33]), it is recommended to take this into account and investigate whether there is a need to mitigate this in future student fieldwork training.

Apart from the improved levels of nervousness, the Welch’s

t-test demonstrated that the group as a whole gained significantly during the field school period in terms of feeling more talkative. This suggests that the activity surely had a value for social connections and engagement. However, they also lost interest and motivation, not dramatically, but the decline was statistically significant. This is maybe difficult to understand for teachers. In psychology, it is said that ‘The function of interest is to motivate knowledge-seeking and exploration, which over time builds knowledge and competence’ [

34]. A decrease in interest among some members of the group could indicate that the knowledge-seeking need or hunger for exploration had been saturated. A declining motivation and interest may also have been caused by circumstances; students may have found themselves disliking archaeological work during warm or wet weather conditions, which they sometimes verbally expressed in other contexts to us as teachers. It is known that a field school setting is not just a place to gain skills and meet new people, but also to figure out whether one wants to pursue excavating as a career [

15], and that is fine too.

Even though the results from this case study are not fully comparable with previous mental well-being studies involving students in fieldwork settings, because the emotions being measured differ slightly from one study to another, and each field project and educational setting is different, there are some striking similarities with the results of Sayer’s case study [

1]. Coincidentally, for the same number of students (54) in a fieldwork training, she also reported a decrease in interest and enthusiasm (motivation), of which enthusiasm was statistically significant. And like with our students, those participating in Sayer’s study also showed high ratings for nervousness at the start, which then decreased significantly during the training excavation.

This brings us to a reflection on the methodology applied. Based on the data collected, we can draw patterns on positive and negative emotions for the group as a whole and its mental well-being. We can also observe that developments in mental well-being for the group as a whole may not count for all individuals. However, this method is also known to be limited in scope. By including positive and negative emotions only, it, for instance, does not address the multi-dimensional character that psychologists connect with individual health and well-being (e.g., [

24]). Since it typically does not measure elements such as relationships or accomplishments, it does not indicate anything about the overall well-being of participants, nor can it reveal the duration of the effects (only the mental state at a particular moment). Furthermore, there could be a self-selection bias; students who agree to participate may be more motivated and potentially more positive in answering. One must be aware of these limitations.

Moreover, the positive and negative well-being umbrella method does not provide indications concerning specific reasons for positive or negative moods. As such, it cannot be known if there is a direct relation with the activity and whether all other factors potentially influencing mental well-being—like family matters, personal issues, weather conditions, accommodation, and group composition—remained the same and had no influence during the period of measurement. To mitigate this limitation, it is recommended to implement a mixed-method approach in future studies, with qualitative (interview) data complementing quantitative well-being measurements. One could also be more confident about the effect of field training on student well-being if there were a larger body of literature presenting similar and comparable data for other field schools. With only one case study from the UK [

1] to compare—while annually dozens of field schools take place across the globe—there is room and a need for more systematic, empirical studies on student well-being in fieldwork training.

An additional argument for adding mental well-being studies more structurally to student training lies in the acknowledged risks for student well-being in outdoor training settings, as mentioned in the introduction. Given the risks, studies on fieldwork training recommend incorporating explicit attention to safety and well-being in student training (e.g., [

3,

4]) and fieldwork settings in general [

6]. For this, varying directions and instruments are being suggested, from implementing formalised discussions, policies, and structures, to safety-related certifications and Mental Health First Aid training for fieldwork leaders, most of which focus on prevention rather than monitoring or intervention. Based on our results, we recommend adding well-being measurements like a positive and negative well-being umbrella—or any of its validated and standardised alternatives [

27]—to these instruments, as these help to monitor well-being levels easily and can signal potential issues requiring intervention.

In the case of the Faculty of Archaeology’s field school, there is already serious attention to social safety. A code of conduct for fieldwork was installed, the use of course evaluations is a standard procedure, and students can turn to confidentiality counsellors. However, these instruments serve purposes other than monitoring students’ mental well-being. Course evaluations primarily measure teacher performance, and students are only expected to turn to counsellors in cases of serious misbehaviour by peers or staff members, not in cases of distress, anxiety, or discomfort related to other causes. Moreover, such instruments cannot be used to signal individual well-being issues during a course, while umbrella-based mental well-being measurements, in principle, can. Therefore, it would be useful to offer instruments like well-being monitoring with a low use-threshold to all students, so as not to place the burden of monitoring their mental well-being on students themselves, nor to make them responsible for taking the initiative or give the impression they are ‘complaining’.

7. Conclusions

This case study looked at self-reported mental well-being ratings from 170 students who participated in archaeological field training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students completed a PANAS-based mental well-being questionnaire at the start and end of two weeks of archaeological work. The questionnaire was based on the well-being umbrella (University College London); it measured six positive and six negative emotions.

Ratings turned out quite high for positive emotions and rather low for negative moods, suggesting that the students felt quite well at the start. No one reported high levels of negative emotions in combination with low levels of positive emotions. Therefore, there was no concern that the group showed high levels of depression, unlike some other student studies from this pandemic period [

16].

Based on statistical tests (Welch’s t-test for the entire group and Wilcoxon’s t-test for a subgroup), a significant decrease was found at the end of the field school for ratings on two positive emotions (feeling interested, feeling motivated), and a significant increase was found for feeling talkative. Regarding negative emotions, only nervousness was rated a bit higher than the other emotions at the start, but it also significantly decreased at the end. Overall, the ratings remained quite high for positive emotions and low for negative emotions.

Since it was also observed in another case study [

1] that the highest level for negative emotions was nervousness, the question should be raised as to whether the prospect of participating in this activity contributed to this nervousness. An implication of this research for the ethical understanding of archaeological field school training is that it requires more in-depth investigation into whether students’ stress levels need to be lowered in future training settings.

Apart from the generally quite positive patterns, it could also be observed that the changes were not similar for all. Whereas an almost equally large percentage (84% versus 88% at the start) of all students ended up with a high well-being level for positive emotions, and 91% with a low level of negative emotions, some students reported a decline in mental well-being. With the subgroup of 54 students that handed in ratings at all four interval periods, it could be observed that the ratings for negative emotions improved for 70% but decreased for 9%. Therefore, our hypothesis that students could benefit in terms of social and psychological well-being from being outside and conducting archaeology training in a socially engaging environment turned out to be true for a majority, but not for all. This implies that it is important to realise that positive developments for the group as a whole may not count for all individuals and that it is worth looking into ways to prevent a potential decrease in individual student well-being in an educational setting.

These results have demonstrated the value of measuring student well-being during training activities, not just in times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, and that there is a need for more comparable results on well-being in student training during fieldwork. To better understand the development in ratings, it is furthermore recommended that future researchers apply a mixed-methods approach and gather additional qualitative data from participants. With the PANAS method, it is impossible to distinguish whether the environment influenced these improvements or deteriorations in the students or whether other external factors were involved. Since archaeological fieldwork and training are acknowledged to come with well-being risks, the authors recommend that future field schools regularly verify the well-being of the student community by implementing well-being evaluations as a standard procedure, to help universities further improve their learning environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.H.v.d.D.; methodology, M.H.v.d.D. and F.C.M.T.; data gathering, F.C.M.T.; data processing, M.H.v.d.D. and F.C.M.T.; validation, M.H.v.d.D.; writing—original draft, M.H.v.d.D.; writing—review and editing, F.C.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

By handing in the survey forms, all participants gave permission to take part in this study and to use the data for research purposes. An ethical protocol was in place and applied; all students were invited to participate, and were informed about the aims of the study, their rights, and data management (via email, Blackboard, and verbally, all prior to the data gathering).

Informed Consent Statement

The survey was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975); all survey data were gathered anonymously, and participants were informed that their anonymity was assured. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to several colleagues who supported this study and helped to collect the data by distributing and gathering the questionnaires, both during the course activities outdoors and at the faculty building (in random order): Maaike de Waal, Arjan Louwen, Zoë van Litsenburg, Dennis Braekmans, Rocio Vera Flores, Maia Casna, and Mink IJzendoorn. A special word of thanks goes to Jarien Fokkens for processing the data swiftly and meticulously and for his data analysis insights and discussions on the interpretation. This was very much appreciated. Insights on the interpretation of the data were also provided by Arjan Louwen of the Field Research and Education Centre. And finally, it is thanks to the collaboration of our students and their willingness to fill out a questionnaire four times (!) that we were able to conduct this analysis. Thank you all.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This field school is an obligatory course for undergraduate students and, unlike many other archaeological field schools across the globe (e.g., [ 4, 15]), it is not open to non-Leiden first-year students. The undergraduate curriculum requires training in fieldwork (and/or lab work) from second and third year students as well (up to six weeks), but these field schools were not included in this case study. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | As the measurements were handed in anonymously and data processing was not conducted by staff members participating in the field school, it could not be noticed at the time. For reasons of respecting privacy, the authors also do not know if any of these students indicated to the staff that they were having a hard time or needed help. |

| 5 | Welch’s t-test for unequal variances was used as the most robust test statistic [ 29] given that the sample sizes and standard deviations differed between the group reporting well-being at the start (N = 106) and end (N = 97). The software used is IBM SPSS v.30 [ 30]. |

| 6 | Wilcoxon’s Signed Ranks test was conducted to calculate significance for a group of 45 individuals, all providing rating data (scale type) for 4 phases. The software used is IBM SPSS v.30 [ 30]. |

References

- Sayer, F. Can digging make you happy? Archaeological excavations, happiness and heritage. Arts Health Int. J. Res. Policy Pract. 2015, 7, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, H.; Croucher, K. Assembling wellbeing in archaeological teaching and learning. In Archaeology, Heritage and Wellbeing. Authentic, Powerful, and Therapeutic Engagement with the Past; Everill, P., Burnell, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.E.; Meehan, P.; Klehm, C.; Kurnick, S.; Cameron, C. Recommendations for safety education and training for graduate students directing field projects. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2021, 9, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, M.C. Towards a safe archaeological field school. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2021, 9, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.P.; Colaninno, C.E. Bending the trajectory of field school teaching and learning through active and advocacy archaeology. Humans 2023, 3, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifling, K.P. Mental health and the field research team. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2021, 9, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.; Siriwardena, N.; Laparidou, D.; Pattinson, J.; Sima, C.; Scott, A.; Hughes, H.; Akanuwe, J. Wellbeing in Volunteers on Heritage at Risk Projects; Research Report Series no. 57/2021; Historic England: London, UK, 2021. Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/research/results/reports/8485/WellbeinginVolunteersonHeritageatRiskProjects (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Everill, P.; Burnell, K. (Eds.) Archaeology, Heritage and Wellbeing. Authentic, Powerful, and Therapeutic Engagement with the Past; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.; Eve, S.; Haverkate-Emmerson, V.; Pollard, T.; Steinberg, E.; Ulke, D. Waterloo Uncovered: From discoveries in conflict archaeology to military veteran collaboration and recovery on one of the world’s most famous battlefields. In Historic Landscapes and Mental Well-Being; Darvill, T., Barrass, K., Drysdale, L., Heaslip, V., Staelens, Y., Eds.; Archaeopress: Summertown, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Everill, P.; Bennett, R.; Burnell, K. Dig in: An evaluation of the role of archaeological fieldwork for the improved wellbeing of military veterans. Antiquity 2020, 94, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiddey, R.; Schofield, J. Embrace the Margins: Adventures in Archaeology and Homelessness. Public Archaeol. 2011, 10, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaslip, V.; Vahdaninia, M.; Hind, M.; Darvill, T.; Staelens, Y.; O’Donoghue, D.; Drysdale, L.; Lunt, S.; Hogg, C.; Allfrey, M.; et al. Locating oneself in the past to influence the present: Impacts of Neolithic landscapes on mental health well-being. Health Place 2020, 62, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boom, K.H.J. Imprint of Action: The Sociocultural Impact of Public Activities in Archaeology; Leiden University; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- van den Dries, M.H. Bring it on! Increasing heritage participation through engagement opportunities at unconventional places. In Transforming Heritage Practice in the 21st Century, Contributions from Community Archaeology; Jameson, J.H., Ed.; One World Archaeology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.E. Authentic learning in field schools: Preparing future members of the archaeological community. World Archaeol. 2004, 36, 236–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus University Rotterdam Student Wellbeing Monitor. General Report on First ASSESSMENT Wave (Dec 2020–Jan 2021); Erasmus University Rotterdam Student Wellbeing Monitor: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.eur.nl/en/media/2021-06-studentmonitorgeneralreport2020 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Pacansky-Brock, M.; Smedshammer, M.; Vincent-Layton, K. Humanizing Online Teaching to Equitize Higher Education. Curr. Issues Educ. 2020, 21. Available online: https://cie.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/cieatasu/article/view/1905 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Lee, K. Rethinking the accessibility of online higher education: A historical review. Internet High. Educ. 2017, 33, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R.; De Wever, B.; Voet, M. Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S. As distance education comes of age, the challenge is keeping the students. Chron. High. Educ. 2000, 46, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Willging, P.A.; Johnson, S.D. Factors that Influence Students’ Decision to Dropout of Online Courses. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2009, 13, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cefa, B.; Zawacki-Richter, O. Mapping the dropout phenomenon in open, distance, and digital education (ODDE): A conceptual analysis. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2025, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, S.G. Factors That Influence Students’ Decision to Drop Out of an Online Business Course. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9689&context=dissertations (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Baxter, L.; Burnell, K. What is wellbeing and how do we measure and evaluate it? In Archaeology, Heritage and Wellbeing. Authentic, Powerful, and Therapeutic Engagement with the Past; Everill, P., Burnell, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, L.J.; Chatterjee, H.J. UCL Museum Wellbeing Measures Toolkit; University College London: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/culture/sites/culture/files/ucl_museum_wellbeing_measures_toolkit_sept2013.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Thomson, L.J.; Chatterjee, H.J. Measuring the impact of museum activities on well-being: Developing the Museum Well-being Measures Toolkit. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2015, 30, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, L.J.; Chatterjee, H.J. Heritage, creativity, and wellbeing: Approaches for evaluating the impact of cultural participation using the UCL Museum Wellbeing Measures. In Archaeology, Heritage and Wellbeing. Authentic, Powerful, and Therapeutic Engagement with the Past; Everill, P., Burnell, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.S.; McCabe, G.P.; Craig, B.A. Introduction to the Practice of Statistics; W.H. Freeman and Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, S.; Schwabe, L. Learning and memory under stress: Implications for the classroom. Npj Sci. Learn. 2016, 1, 16011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Hetrick, S.E. The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimmen, S.; Timmermans, O.; Mikolajczak-Degrauwe, K.; Oenema, A. How stress-related factors affect mental wellbeing of university students. A cross-sectional study to explore the associations between stressors, perceived stress, and mental wellbeing. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvia, P.J. Exploring the Psychology of Interest; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The geographical location of Oss (drawing: Harry Fokkens, used with permission), where students conducted activities during the 2021 field school (Photo: Arjan Louwen, used with permission).

Figure 1.

The geographical location of Oss (drawing: Harry Fokkens, used with permission), where students conducted activities during the 2021 field school (Photo: Arjan Louwen, used with permission).

Figure 2.

UCL positive (

left) and negative (

right) well-being umbrellas [

25]. The numbers refer to mood levels; 1 equals ‘not at all’, 5 equals ‘extremely’.

Figure 2.

UCL positive (

left) and negative (

right) well-being umbrellas [

25]. The numbers refer to mood levels; 1 equals ‘not at all’, 5 equals ‘extremely’.

Figure 3.

Distribution (in percentages) of reported mood levels for positive emotions at the start of the fieldwork activities in phase 1 (N = 106).

Figure 3.

Distribution (in percentages) of reported mood levels for positive emotions at the start of the fieldwork activities in phase 1 (N = 106).

Figure 4.

Distribution (in percentages) of reported mood levels (1–5) for negative emotions at the start of the fieldwork activities (phase 1) (N = 106).

Figure 4.

Distribution (in percentages) of reported mood levels (1–5) for negative emotions at the start of the fieldwork activities (phase 1) (N = 106).

Figure 5.

Averages for all participants across all emotion ratings at the four measurement moments.

Figure 5.

Averages for all participants across all emotion ratings at the four measurement moments.

Figure 6.

Distribution (in percentages) of the reported mood levels (1–5) on positive emotions at the end of the lab work activities (phase 4, N = 97).

Figure 6.

Distribution (in percentages) of the reported mood levels (1–5) on positive emotions at the end of the lab work activities (phase 4, N = 97).

Figure 7.

Distribution of averages for all positive emotions in phase 1 versus phase 4 (phase 1 N = 106; phase 4 N = 97).

Figure 7.

Distribution of averages for all positive emotions in phase 1 versus phase 4 (phase 1 N = 106; phase 4 N = 97).

Figure 8.

Distribution (in percentages) of the reported mood levels (1–5) on negative emotions in phase 4 (N = 97).

Figure 8.

Distribution (in percentages) of the reported mood levels (1–5) on negative emotions in phase 4 (N = 97).

Figure 9.

Distribution of average scores for all six negative emotions in phase 1 versus phase 4 (phase 1 N = 106; phase 4 N = 97).

Figure 9.

Distribution of average scores for all six negative emotions in phase 1 versus phase 4 (phase 1 N = 106; phase 4 N = 97).

Figure 10.

Average ratings for positive emotions (left) and negative emotions (right) from phase 1 to 4 (N = 54).

Figure 10.

Average ratings for positive emotions (left) and negative emotions (right) from phase 1 to 4 (N = 54).

Figure 11.

The number of participants reporting an increase or decrease in positive (left) and negative (right) emotions from phase 1 to 4.

Figure 11.

The number of participants reporting an increase or decrease in positive (left) and negative (right) emotions from phase 1 to 4.

Table 1.

Demographic information provided by students on 420 forms. Gender values result from self-identification.

Table 1.

Demographic information provided by students on 420 forms. Gender values result from self-identification.

| | N | % |

|---|

| Gender | | |

| Male | 193 | 46 |

| Female | 189 | 45 |

| Other | 38 | 9 |

| Nationality | | |

| Dutch | 311 | 74.1 |

| International students | 98 | 23.3 |

| Not indicated | 11 | 2.6 |

Table 2.

Welch’s t-test for a comparison of emotion ratings at the start (phase 1, M1) and the end (phase 4, M2). Sample size n1 = 106, n2 = 97; Mean (M); Standard Deviation (SD); t-statistic; Degrees of Freedom (df); p-value (p); 95% Confidence Interval (CI); Effect Size (Cohen’s d). * significant.

Table 2.

Welch’s t-test for a comparison of emotion ratings at the start (phase 1, M1) and the end (phase 4, M2). Sample size n1 = 106, n2 = 97; Mean (M); Standard Deviation (SD); t-statistic; Degrees of Freedom (df); p-value (p); 95% Confidence Interval (CI); Effect Size (Cohen’s d). * significant.

| Emotions | M1 | M2 | Diff. | SD1 | SD2 | t | df1 | df2 | p | CI Lower | CI

Upper | d |

|---|

| Interested | 4.15 | 3.55 | −0.60 | 0.75 | 1.01 | 23.012 | 1 | 176.683 | <0.001 * | 0.038 | 0.189 | 0.886 |

| Lively | 3.25 | 3.66 | 0.41 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 7.811 | 1 | 197.657 | 0.006 * | 0.003 | 0.101 | 1.019 |

| Motivated | 3.83 | 3.45 | −0.38 | 0.92 | 1.10 | 6.862 | 1 | 187.179 | 0.010 * | 0.002 | 0.095 | 1.015 |

| Positive | 3.29 | 3.81 | 0.11 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.770 | 1 | 199.726 | 0.381 | 0.000 | 0.038 | 0.944 |

| Talkative | 3.70 | 3.76 | 0.47 | 1.13 | 0.87 | 10.652 | 1 | 193.933 | 0.001 * | 0.008 | 0.119 | 1.021 |

| Friendly | 3.97 | 4.09 | 0.12 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 1.065 | 1 | 200.957 | 0.303 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.838 |

| Distressed | 1.73 | 1.52 | −0.21 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 2.683 | 1 | 198.456 | 0.103 | 0.000 | 0.061 | 0.887 |

| Irritable | 1.59 | 1.41 | −0.18 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 2.712 | 1 | 200.910 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 0.060 | 0.789 |

| Nervous | 2.09 | 1.40 | −0.68 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 27.652 | 1 | 197.360 | <0.001 * | 0.047 | 0.205 | 0.939 |

| Scared | 1.35 | 1.18 | −0.17 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 3.065 | 1 | 199.188 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.064 | 0.664 |

| Unhappy | 1.40 | 1.37 | −0.03 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.054 | 1 | 195.898 | 0.817 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.499 |

| Upset | 1.15 | 1.28 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.79 | 2.366 | 1 | 141.152 | 0.126 | 0.000 | 0.058 | 0.621 |

Table 3.

Demographics of the group of 54 students participating in all four surveys.

Table 3.

Demographics of the group of 54 students participating in all four surveys.

| | N | % |

|---|

| Male | 25 | 46.3 |

| Female | 23 | 42.6 |

| Non-binary | 11 | 11.1 |

| Dutch | 40 | 74.1 |

| International students | 14 | 25.9 |

Table 4.

Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of student ratings for positive emotions at four occasions (N = 54).

Table 4.

Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of student ratings for positive emotions at four occasions (N = 54).

| | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 |

|---|

| Emotions | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

|---|

| Interested | 4.24 | 0.61 | 4.24 | 0.72 | 3.63 | 0.93 | 3.63 | 0.92 |

| Lively | 3.57 | 1.02 | 3.46 | 0.92 | 3.50 | 1.02 | 3.76 | 1.03 |

| Motivated | 3.91 | 0.91 | 3.85 | 0.94 | 3.52 | 1.00 | 3.59 | 1.00 |

| Positive | 3.93 | 0.80 | 3.94 | 0.76 | 3.81 | 0.97 | 3.85 | 0.90 |

| Talkative | 3.35 | 1.10 | 3.43 | 1.02 | 3.39 | 1.08 | 3.80 | 0.96 |

| Friendly | 3.98 | 0.83 | 3.98 | 0.79 | 3.89 | 0.90 | 4.13 | 0.80 |

Table 5.

Changes in average ratings for positive emotions among the group of 54 students, based on the Wilcoxon significance test (p-value 0.05). Difference in averages (M. diff.), test statistic (z), * significant differences.

Table 5.

Changes in average ratings for positive emotions among the group of 54 students, based on the Wilcoxon significance test (p-value 0.05). Difference in averages (M. diff.), test statistic (z), * significant differences.

| | Phase 1 to 2 | Phase 2 to 3 | Phase 3 to 4 | Phase 1 to 4 |

|---|

| | M. Diff. | z | M. Diff. | z | M. Diff. | z | M. Diff. | z |

|---|

| Interested | 0 | 0.955 | −0.61 | <0.001 * | 0 | 1 | −0.61 | <0.001 * |

| Lively | −0.11 | 0.403 | 0.04 | 0.842 | 0.26 | 0.045 * | 0.19 | 0.291 |

| Motivated | −0.06 | 0.632 | −0.33 | 0.045 * | 0.07 | 0.546 | −0.32 | 0.028 * |

| Positive | 0.01 | 0.655 | −0.13 | 0.258 | 0.04 | 0.643 | −0.08 | 0.842 |

| Talkative | 0.08 | 0.494 | −0.04 | 0.796 | 0.41 | 0.005 * | 0.45 | <0.001 * |

| Friendly | 0 | 0.867 | −0.09 | 0.465 | 0.24 | 0.052 | 0.15 | 0.181 |

Table 6.

Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) for student ratings on negative emotions at four occasions (N = 54).

Table 6.

Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) for student ratings on negative emotions at four occasions (N = 54).

| | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 |

|---|

| Emotions | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

|---|

| Distressed | 1.56 | 0.69 | 1.5 | 0.82 | 1.44 | 0.84 | 1.46 | 0.90 |

| Irritable | 1.48 | 0.66 | 1.48 | 0.61 | 1.35 | 0.70 | 1.46 | 0.84 |

| Nervous | 1.92 | 0.77 | 1.31 | 0.58 | 1.56 | 0.79 | 1.28 | 0.68 |

| Scarred | 1.22 | 0.46 | 1.09 | 0.35 | 1.17 | 0.64 | 1.11 | 0.57 |

| Unhappy | 1.30 | 0.63 | 1.24 | 0.47 | 1.30 | 0.69 | 1.28 | 0.76 |

| Upset | 1.11 | 0.32 | 1.22 | 0.42 | 1.24 | 0.64 | 1.28 | 0.88 |

Table 7.

Changes in average ratings for negative emotions among the group of 54 students, based on the Wilcoxon significance test (p-value 0.05); * significant differences.

Table 7.

Changes in average ratings for negative emotions among the group of 54 students, based on the Wilcoxon significance test (p-value 0.05); * significant differences.

| | Phase 1 to 2 | Phase 2 to 3 | Phase 3 to 4 | Phase 1 to 4 |

|---|

| | M. Diff | z | M. Diff. | z | M. Diff. | z | M. Diff. | z |

|---|

| Distressed | −0.06 | 0.616 | −0.06 | 0.512 | 0.02 | 0.805 | −0.10 | 0.344 |

| Irritable | 0 | 0.983 | −0.13 | 0.142 | 0.11 | 0.513 | −0.02 | 0.754 |

| Nervous | −0.61 | <0.001 * | 0.25 | 0.035 * | −0.28 | 0.006 * | −0.64 | <0.001 * |

| Scarred | −0.13 | 0.071 | 0.08 | 0.429 | −0.06 | 0.180 | −0.11 | 0.033 * |

| Unhappy | −0.06 | 0.531 | 0.06 | 0.632 | −0.02 | 0.564 | −0.02 | 0.501 |

| Upset | 0.11 | 0.109 | 0.02 | 0.808 | 0.04 | 0.660 | 0.17 | 0.357 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).