To What Extent Are the Type Localities of Minerals Part of Geological Heritage? A Global Review and the Case of Spain as an Example

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

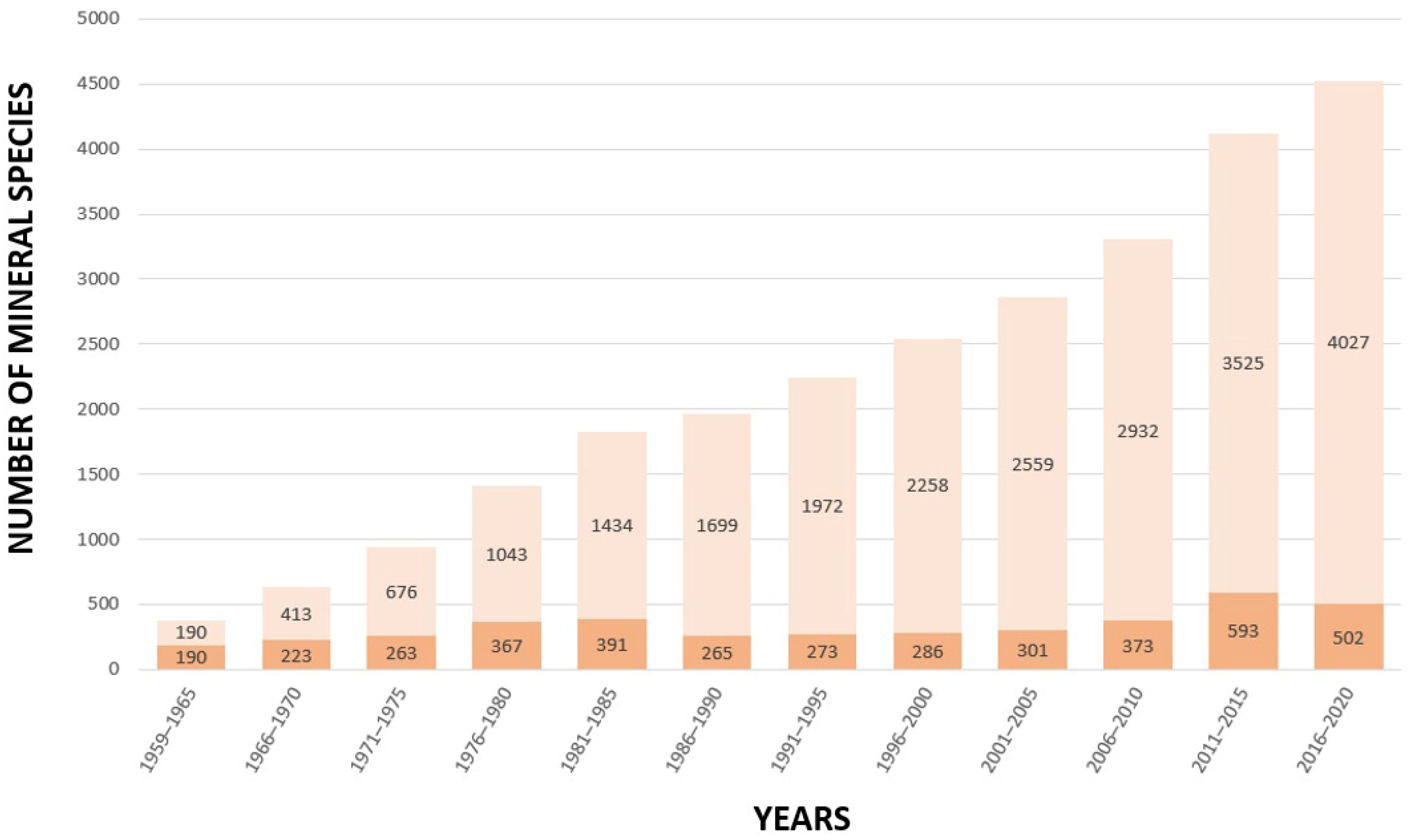

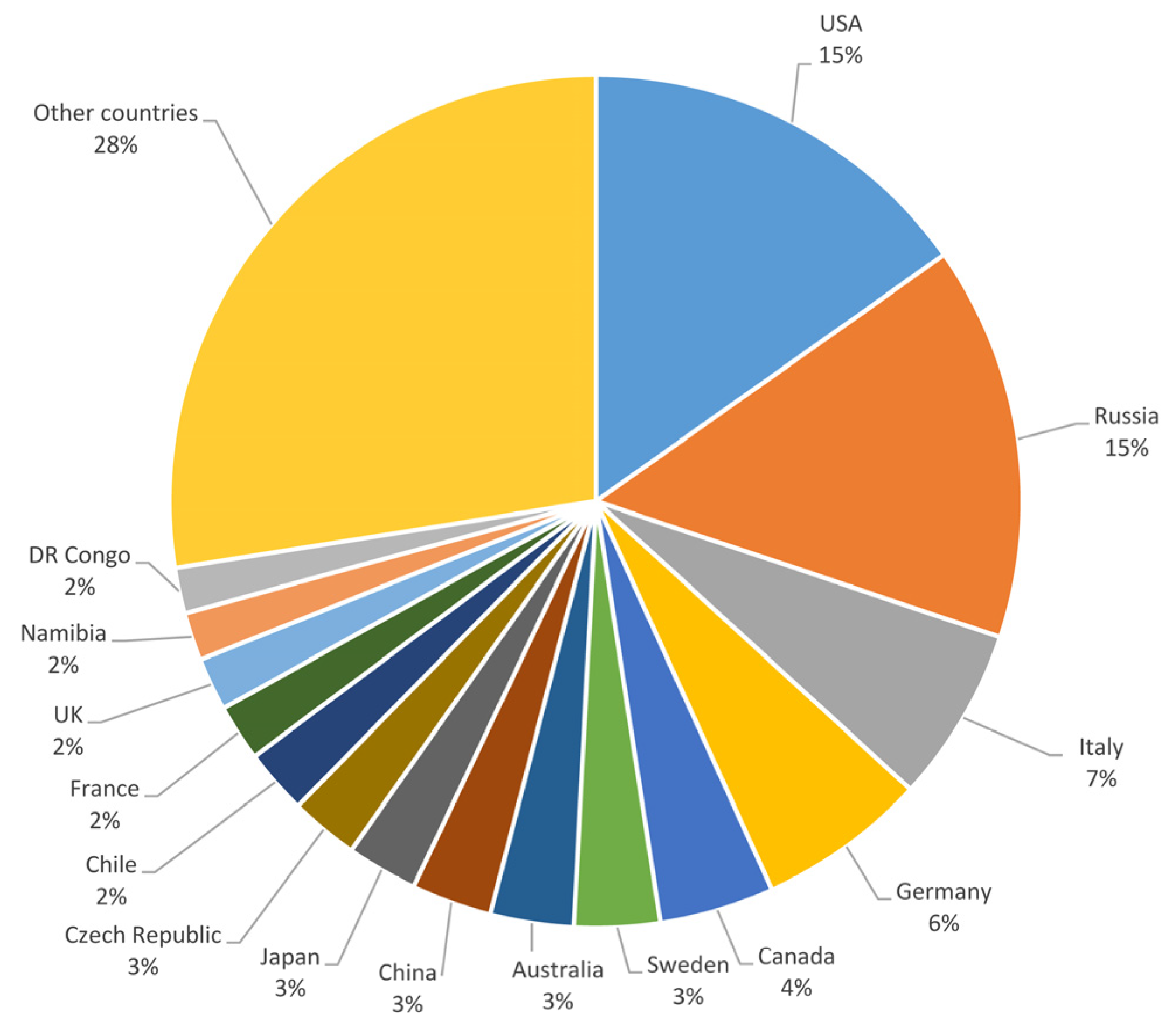

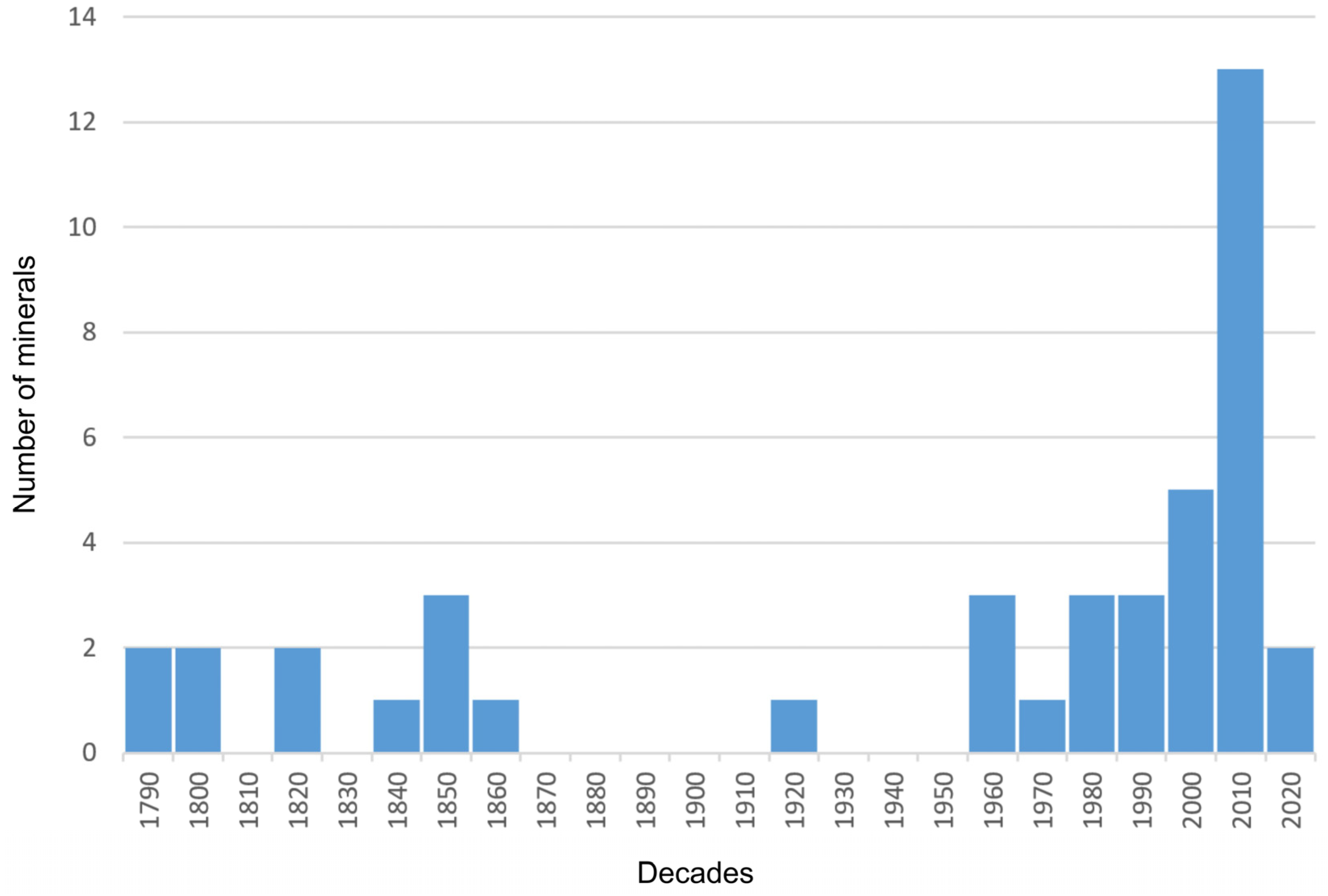

3.1. Global Situation

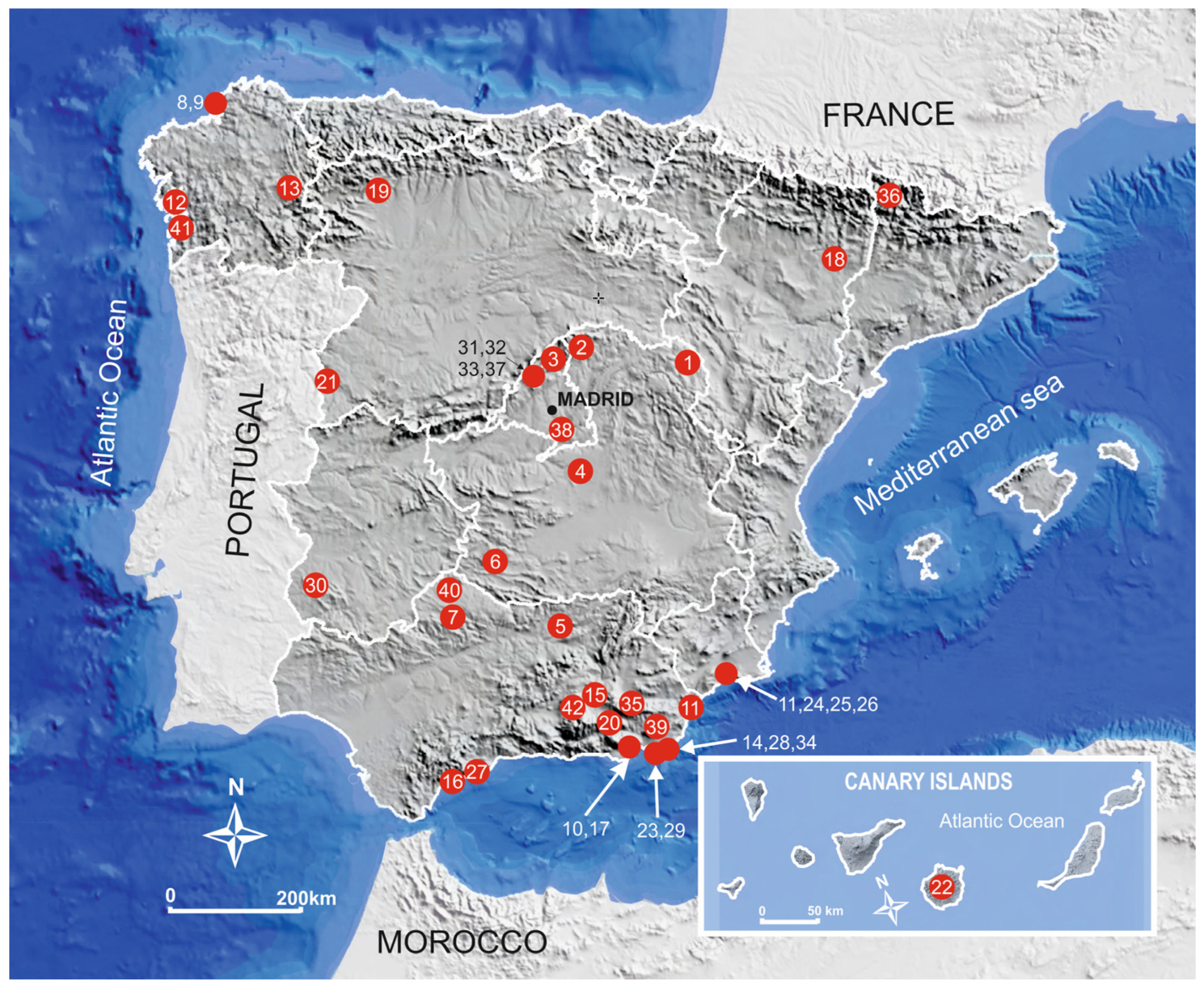

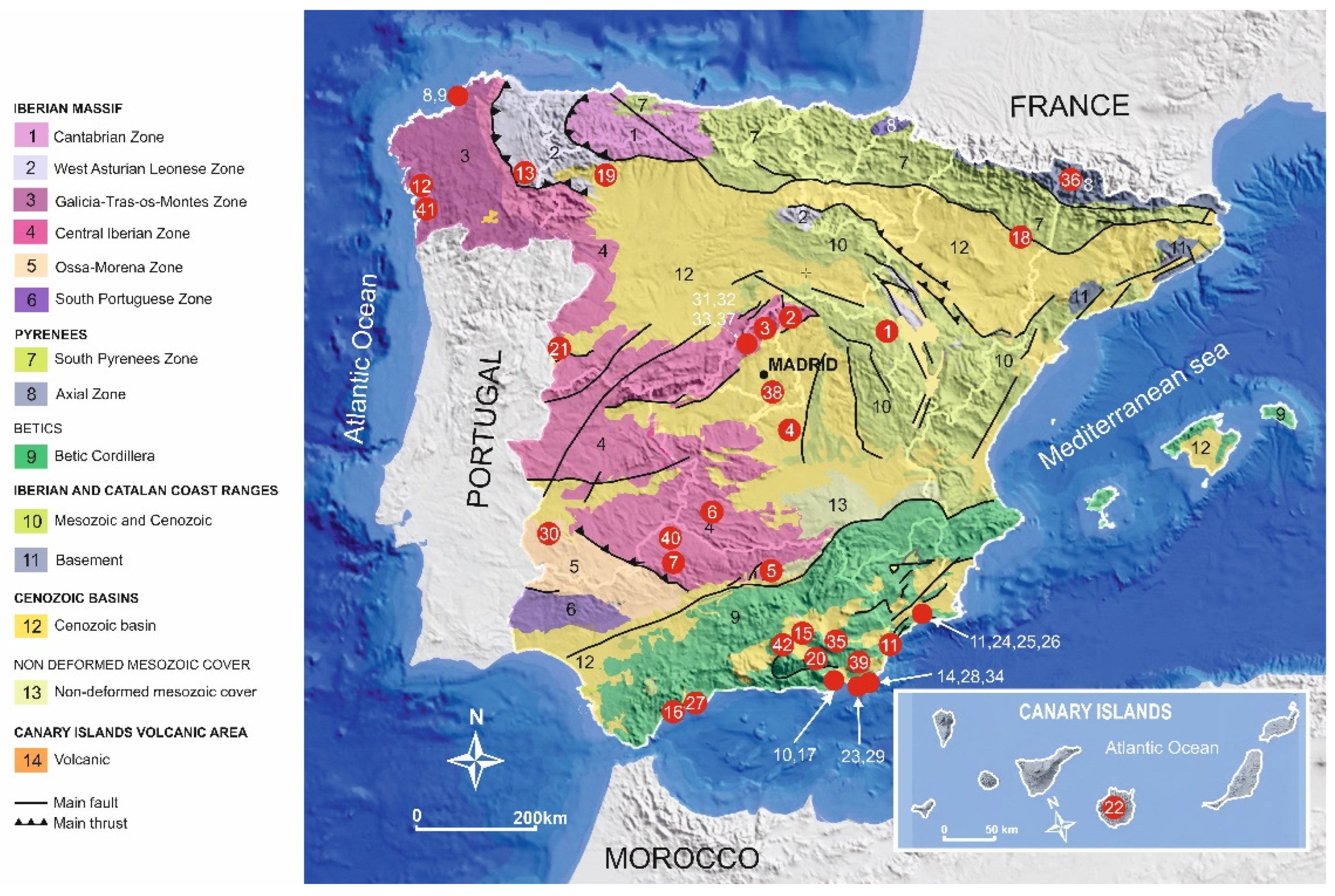

3.2. Case of Spain

- -

- Andalusite: although the location of the type locality is not exactly known, it is known to be in El Cardoso de la Sierra (Guadalajara), within the Sierra Norte de Guadalajara Natural Park.

- -

- Aragonite: in the UNESCO World Geopark of Molina–Alto Tajo (Figure 8).

- -

- Cervantite: although the exact location of the mine where the specimens that led to its discovery were extracted is unknown, the municipality is included in the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve of Los Ancares Lucenses and Montes de Cervantes, Navia, and Becerreá.

- -

- Clino-ferri-holmquistite, clino-ferro-ferri-holmquistite, ferri-pedrizite, and ferro-ferri-pedrizite: in Guadarrama National Park.

- -

- Calomel: in Almadén Mining Park, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list under the name of Mercury Heritage: Almadén and Idrija.

- -

- Chlorapatite, fluorapatite, hydroniumpharmacoalumite, natropharmacoalumite, and rodalquilarite: in the Natural Park, Biosphere Reserve, and UNESCO World Geopark of Cabo de Gata.

- -

- Fehrite: in the Natural Park of Sierra Alhamilla.

- -

- Ferberite, jarosite, and zincosite: in the Spatial Conservation Zone (Natura 2000 Network) of Sierras Almagrera, de los Pinos, and el Aguilón.

- -

- Moganite: in the Gran Canaria Biosphere Reserve.

- -

- Morenosite and zaratite: although the place was buried under a coastal landslide, it is included in the UNESCO World Geopark of Cabo Ortegal.

- -

- Rutile: although the exact location of the type locality is unknown, it is known to be within the Sierra del Rincón Biosphere Reserve.

- -

- Thenardite: in the Well of Cultural Interest (category of protection of the Cultural Heritage) of the Salinas de Espartinas.

- -

- Villamaninite: in the Los Argüellos Biosphere Reserve.

- -

- Westerveldite: in the Sierra de las Nieves Biosphere Reserve and its surroundings.

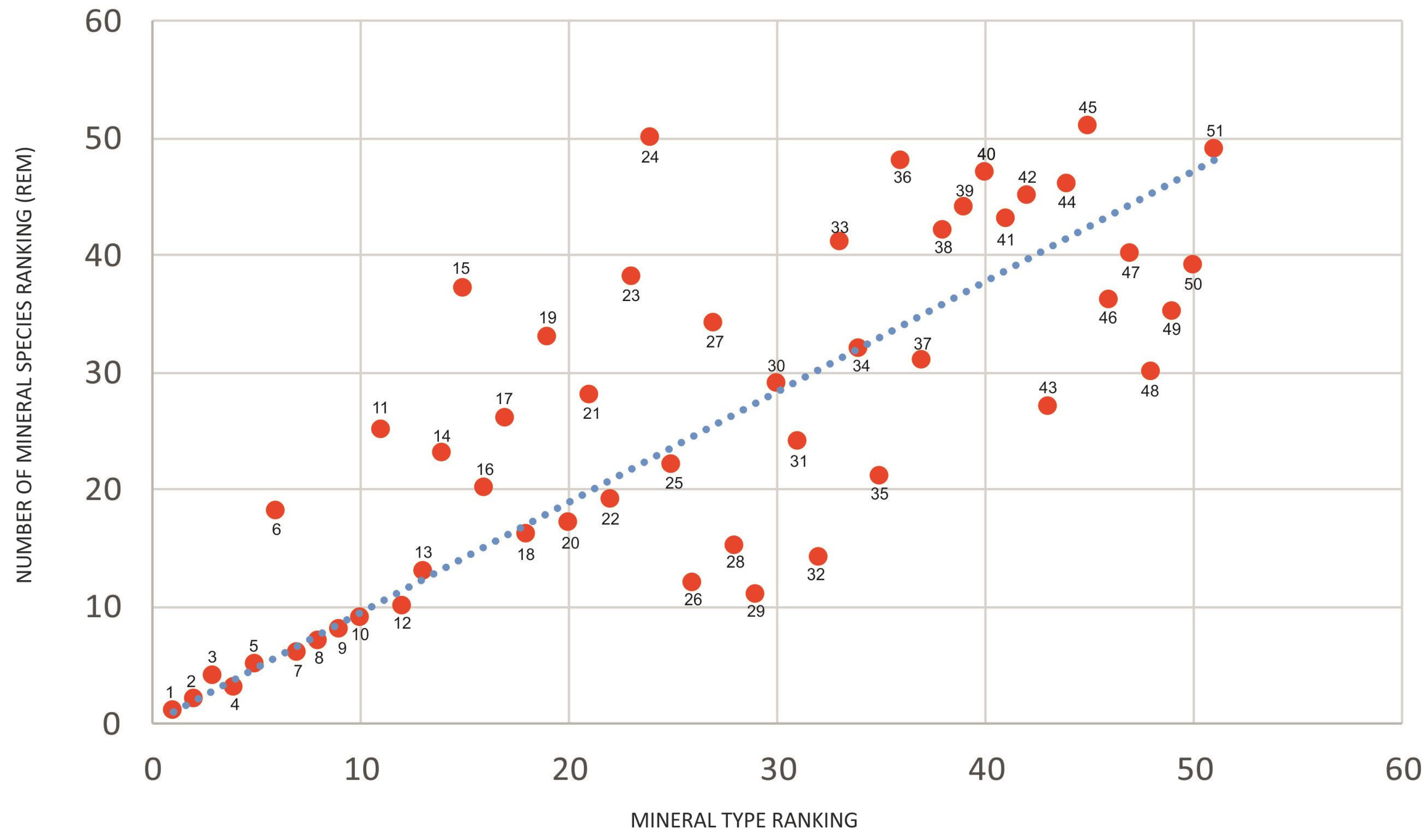

4. Discussion

4.1. Global Situation

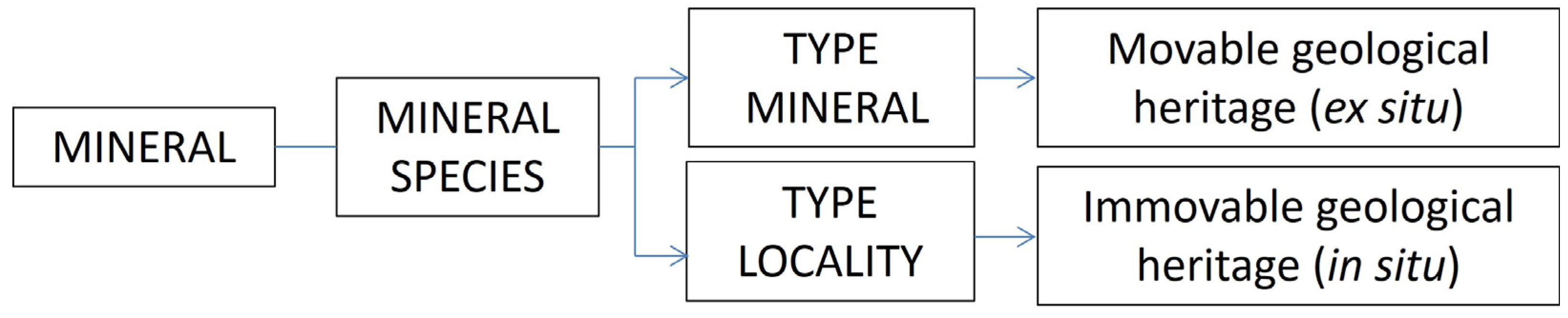

- (1)

- Not all the new mineral species define a type locality, since the origin of the sample that gave rise to the first determination may be unknown. Thus, there is a unique equivalence between mineral species and type minerals but not between mineral species and the type locality, such that not all mineral species have a type locality that can be a geosite; instead, there are several possible cases.

- (2)

- Type localities do not always offer the opportunity for new studies, as stated by Ruban (2018). This is particularly the case for those discovered in recent decades because material for determinations has been obtained and exhausted. In other words, there may be no more minerals remaining in the type locality; therefore, no further studies can be carried out.

- (3)

- Sometimes, the specimen from which the new mineral species was extracted is not related to the geological environment, as with the type minerals described from meteorites, such that the place where it was found is completely decontextualized and not geological or paragenetic. In this case, the concept of type locality is meaningless from the heritage point of view, and no geosite is defined.

- (4)

- Advances in mineralogy have led to reclassifications that modify the status of mineral species. In such cases, the type locality of a certain mineral species may lose its significance when the species is reclassified and loses its status as a new species. Such problems can occur at any type of locality, and as stated by Ruban [12], if a mineral species was described from a specimen, it means that at the time, it was a milestone in geological knowledge and was assigned special value. Brocx and Semeniuk [7] also insist on the idea of the patrimonial value of “historically significant sites where original contributions to the understanding of geological processes or principles were inspired” and argue that such sites should be part of geological heritage, regardless of whether their status is later revoked by advances.

- (5)

- Some minerals have been discovered in deep boreholes and inaccessible areas, so they do not define a geosite.

- (6)

- Are there some type localities that are dumps? A dump is an anthropically modified place, so it should not constitute a geosite or a type locality. However, in some cases, the deposit is completely depleted, and the only place where the type specimens can be observed is in the dumps of mining operations; thus, in this case, these places show paragenesis of the type locality and can be used as reserves of type samples.

- (7)

- An important aspect is to evaluate the degree of relevance of the type localities. Not all the elements of geological heritage have the same degree of interest, and they are frequently categorized as local, regional, national, or international [7]. Ruban [12] proposed that, at a minimum, type localities should have national relevance since they represent the place where a new mineral was discovered for the scientific community worldwide. The problem with assigning them international relevance is that the concept of world geological heritage makes sense when the elements that compose it are exclusive and relatively limited in number. Type localities can be considered exclusive, but in number, they would amount to several thousand geosites of international relevance. If thousands of other geosites from different earth science disciplines were added, the concept of geological heritage of global relevance would be distorted by the excessive number of sites. Therefore, it seems appropriate that the type localities are included in national inventories and that this characteristic is valuable, although not definitive, when proposing geosites of international relevance.

- (8)

- Is it necessary to consider the type locality as part of the geological heritage, or is it preferable to look for the best deposit of the mineral in question? The declaration of the type mineral includes scientific, historical, and geographical aspects inherent to the type locality; therefore, it is this aspect that must be considered in heritage inventories.

- (9)

- Does it make sense to consider as heritage an exhausted type locality, or a type locality where it is no longer possible to find specimens of the mineral that gave rise to its classification as such? Regardless of the existence of these minerals, the type locality includes the elements of scientific interest that motivated the declaration, such as the genetic environment and the paragenesis present in the description of the mineral, in addition to the historical and geographical aspects collected in the declaration; therefore, the inclusion of the locality in the national inventories of geosites is recommended.

4.2. Case of Spain

- -

- Fifteen species were collected from localities with several type minerals per locality.

- -

- In seven cases, the place of origin of the type mineral is unknown; therefore, only approximate information is available on the type locality.

- -

- Two minerals come from meteorites and, therefore, cannot generate geosites.

- -

- The type locality of two mineral species is inaccessible because it is hidden by a landslide.

- -

- Two type localities (potassic-ferro-taramite and ermeloite) do not contain more mineralization because they have been depleted.

- -

- Twenty-four types of minerals are located within a protected natural space.

- -

- Only one type locality is marked (Figure 8).

- -

- Guadarrama National Park, where four new mineral species have been defined, has the highest degree of environmental protection assigned by Spanish legislation, with three million visitors a year and five visitor and interpretation centers, one of which is in the sector where new minerals were discovered (La Pedriza).

- -

- UNESCO World Geopark of Molina–Alto Tajo, where the aragonite type locality is located, is marked with a sign, and the geopark museum has a space dedicated exclusively to this mineral.

- -

- The Cabo de Gata UNESCO World Geopark, which is simultaneously a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and a Natural Park, is a site where five mineral species have been discovered, although the exact locations of two of them are unknown. The geopark has an interpretation center in the area with the greatest mining wealth (Rodalquilar).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nickel, E.H. The definition of a mineral. Can. Mineral. 1995, 33, 689–690. [Google Scholar]

- International Mineralogical Association. Available online: https://mineralogy-ima.org/ (accessed on 27 June 2003).

- Evseev, A.A. Geographical location of mineral type localities. New Data Miner. 2003, 38, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ciriotti, M.E.; Fascio, L.; Pasero, M. Italian Type Minerals, 1st ed.; Edizioni Plus-Università di Pisa: Pisa, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carcavilla, L.; Díaz-Martínez, E.; García Cortés, A.; Vegas, J. Geoheritage and Geodiversity; IGME—PanAfGeo: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wimbledon, W.A.P. Geosites—A new conservation initiative. Episodes 1996, 19, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M.; Semeniuk, V. The geoheritage significance of crystals. The Geologists’ Association & the Geological Society of London. Geol. Today 2010, 26, 206–225. [Google Scholar]

- Carcavilla, L.; Delvene, G.; Díaz-Martínez, E.; García-Cortés, A.; Lozano, G.; Rábano, I.; Vegas, J. Geodiversidad y Patrimonio Geológico; IGME—Edición Parques Nacionales: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cairncross, B. The National Heritage Resource Act (1999): Can legislation protect South Africa’s rare geoheritage resources? Resour. Policy 2011, 36, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J. Inventory and quantitative assessment of geosites and geodiversity sites: A review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Martínez, R. Los Minerales y Sus Yacimientos en el Patrimonio Geológico. In Problemática, Valoración y Gestión en España; Serie Tesis Doctorales IGME: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ruban, D.A. New Mineral Discovery Geosites: Valuing for Geoconservation Purposes. Geoconserv. Res. 2018, 1, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfo, F.; Benna, P.; Cadoppi, P.; Castelli, D.; Favero-Longo, S.E.; Giardino, M.; Balestro, G.; Belluso, E.; Borghi, A.; Camara, F.; et al. The Monviso Massif and the Cottian Alps as symbols of the Alpine chain and geological heritage in Piemonte, Italy. Geoheritage 2015, 7, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, P.J.; Mandarino, J.A. Formal definitions of type mineral specimens. Am. Mineral. 1987, 72, 1261–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcavilla, L.; Durán, J.J.; García-Cortés, A.; López-Martínez, J. Geological heritage and geoconservation in Spain: Past, present and future. Geoheritage 2009, 1, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, E.H.; Grice, J.D. The IMA Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names: Procedures and guidelines on mineral nomenclature. Cana. Miner. 1998, 36, 913–926. [Google Scholar]

- Bannister, M.A.; Hey, M.H. Report on some crystalline components of the Weddell Sea deposits. Discov. Rep. 1936, 13, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Güner, F.E.G.; Sakurai, T.; Hondoh, T. Ernstburkeite, Mg(CH3SO3)2·12H2O, a new mineral from Antarctica. Eur. J. Mineral. 2013, 25, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofts, R.; Gordon, J.E. Geoconservation in protected areas. In Protected Area Governance Management; Worboys, G.L., Lockwood, M., Kothari, A., Feary, S., Pulsford, I., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 531–568. [Google Scholar]

- Haüy, C. Sur l’arragonite de Werner. Bull. Sci. Soc. Philom. 1791, 2, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Delamétherie, J.C. Sur une pierre de l’andalousie. J. Phys. Chim. D’histoire Nat. Arts 1798, 46, 386–387. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, C.F. Rutil. In Handbuch der Mineralogie nach A.G. Werner; Siegfried Lebrécht Crusius: Leipzig, Germany, 1803; Volume 1, pp. 305–306. [Google Scholar]

- Brongniart, A. Sur une nouvelle espèce de minéral de la classe des sels, nommée glauberite. J. Mines 1808, 23, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, H.I. On a new lead ore. Ann. Philos. 1822, 4, 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Mohs, F. Treatise on Mineralogy or the Natural History of the Mineral Kingdom; Archivald Constable and Co: Edinburgh, UK, 1825; Volume 1, p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- Breithaupt, J.F.A.; Fritzsche, F.W. Bestimmung neuer mineralien: Konichalcit. Ann. Der Phys. Und Chem. 1849, 77, 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Alcíbar, A. Sobre el mineral de nickel de Galicia, con algunas consideraciones sobre el polimorfismo del sulfato de nickel y de otras sustancias. Rev. Minera 1851, 2, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Alcibar, A. Raro é importante mineral de niquel. Rev. Minera 1850, 1, 302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Breithaupt, G. Beschereibung der zum Teil neuen Gang-Mineralien des Barranco Jaroso in der Sierra Almagrera. Berg. Hüttenmännische Ztg. 1852, 11, 100–102. [Google Scholar]

- Liebe, K.L. Ein neuer wolframit. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie. Geol. Paläontol. 1863, 641–653. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Navarro, L.; Castro, P. La bolivarita, nueva especie mineral. Boletín RSEHN 1921, 21, 326–328. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, J.D. Cervantite. In A System of Mineralogy, 3rd ed.; Dana, J.D., Ed.; G.P. Putnam: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1850; p. 417. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, J.; Leal, G.; Pierrot, L.; Lauren, Y.; Protas, J.; Dusausoy, Y. La rodalquilarite, chlorotelurite de fer, une nouvelle especie minerale. Société Française Minéral. Cristallogr. 1968, 91, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunch, T.E.; Fuchs, L.H. Yagiite, a new sodium-magnesium analogue of osumilite. Am. Mineral. 1969, 54, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Oen, J.S.; Burke, E.A.J.; Kieft, C.; Westerhof, A.B. Westerveldite, (Fe, Ni, Co)As, a new mineral from La Gallega, Spain. Am. Mineral. 1872, 57, 354–363. [Google Scholar]

- Breithaupt, G. Beschereibung der zum Teil neuen Gang-Mineralien des Barranco Jaroso in der Sierra Almagrera. Berg. Hüttenmännische Zeitung 1852, 11, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lasaulx, A. Aerinit, ein neues mineral. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie. Geol. Paläontol. 1876, 352–358. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeller, W.R.; Powell, A.R. Villamaninite, a new mineral. Nature 1919, 104, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffé, B.; Baronnet, A.; Morin, G. La saliotite, interstratifié régulier 1:1 cookéite/paragonite. Nouveau phyllosilicate du métamorphisme de haute pression et basse température. Eur. J. Mineral. 1994, 6, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murciego, A.; Pascua, M.I.; Babkine, J.; Dusausoy, Y.; Medenbach, O.; Bernhardt, H.J. Barquillite, Cu2(Cd,Fe)GeS4, a new mineral from the Barquilla deposit, Salamanca, Spain. Eur. J. Mineral. 1999, 11, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flörke, O.W.; Flörke, U.; Giese, U. Moganite, a new microcrystalline silica-mineral. Neues Jahrb. Mineral. Abh. 1984, 149, 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- González del Tánago, J.; La Iglesia, Á.; Rius, J.; Fernández Santín, S. Calderonite, a new lead-iron-vanadate of the brackebuschite group. Am. Mineral. 2003, 88, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambor, J.L.; Viñals, J.; Groat, L.A.; Raudsepp, M. Cobaltarthurite, Co2+Fe3+2(AsO4)2(OH)2.4H2O, a new member of the arthurite group. Can. Mineral. 2002, 40, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñals, J.; Jambor, J.L.; Raudsepp, M.; Roberts, A.C.; Grice, J.D.; Kokinos, M.; Wise, W.S. Barahonaite-(Al) and barahonaite-(Fe), new Ca-Cu arsenate mineral species, from Murcia Province, southeastern Spain, and Gold Hill, Utah. Can. Mineral. 2008, 46, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Cruz, M.D.; Sanz de Galdeano, C. Suhailite, a new ammonium trioctahedral mica. Am. Mineral. 2009, 94, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, M.S.; Mills, S.J.; Spratt, J. Natropharmacoalumite, NaAl4[(OH)4(AsO4)3].4H2O, a new mineral of the pharmacosiderite supergroup and the renaming of aluminopharmacosiderite to pharmacoalumite. Mineral. Mag. 2010, 74, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Ueber die chemische zusammensetzung der apatite. Ann. Phys. Chem. 1827, 9, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochleitner, R.; Fehr, K.T.; Kaliwoda, M.; Günther, A.; Rewitzer, C.; Schmahl, W.W.; Park, S. Hydroniumpharmacoalumite, (H3O)Al4[(OH)4(AsO4)3]·4.5H2O, a new mineral of the pharmacosiderite supergroup from Rodalquilar, Spain. Neues Jahrb. Mineral. 2015, 192, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, J.M.; Oberti, R.; Ottoloni, L. Ferripedrizite, a new monoclinic BLi amphibole end-member from the Eastern Pedriza Massif, Sierra de Guadarrama, Spain, and a restatement of the nomenclature of Mg-Fe-Mn-Li amphiboles. Am. Mineral. 2002, 87, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberti, R.; Cámara, F.; Caballero, J.M.; Ottolini, L. Sodic-ferri-ferropedrizite and ferri-clinoferroholmquistite: Mineral data and degree of order of the A-site cations in Li-rich amphiboles. Can. Mineral. 2003, 41, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberti, R.; Boiocchi, M.; Smith, D.C.; Mendenbach, O.; Helmers, H. Potassic-aluminotaramite from Sierra de los Filabres, Spain. Eur. J. Mineral. 2008, 20, 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Insa, J.; Elvira, J.J.; Llovet, X.; Pérez-Cano, J.; Oriols, N.; Busquets-Masó, M.; Hernández, S. Abellaite, NaPb2(CO3)2(OH), a new supergene mineral from the Eureka mine, Lleida province, Catalonia, Spain. Eur. J. Mineral. 2017, 29, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberti, R.; Cámara, F.; Caballero, J.M. Ferri-ottoliniite and ferriwhittakerite, two new end-members of the new Group 5 for monoclinic amphiboles. Am. Mineral. 2004, 89, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaseca, J.L. Analyse et examen cristalographique de la thénardite. Ann. Chim. Phys. 1826, 32, 308–311. [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter, J.; Malcherek, T.; Mihailova, B.; Rewitzer, C.; Hochleitner, R.; Müller, D.; Günther, A. Fehrite, MgCu4(SO4)2(OH)6·6H2O, the magnesium analogue of ktenasite from the Casualidad mine near Baños de Alhamilla, Almeria, Spain. Neues Jahrb. Mineral. Abh. 2021, 197, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, I.E.; Hochleitner, R.; Rewitzer, C.; Riboldi-Tunnicliffe, A.; Kampf, A.R.; MacRae, C.M.; Mumme, W.G.; Kaliwoda, M.; Friis, H.; Martin, C.U. The walentaite group and the description of a new member, alcantarillaite, from the Alcantarilla mine, Belalcázar, Córdoba, Andalusia, Spain. Mineral. Mag. 2020, 84, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza Vérez, G.; Rodríguez Vázquez, C.J.; Dacuña Mariño, B.; Fernández Cereijo, I.; González del Tánago, J.; Jiménez Martínez, R.; Barreiro Pérez, R.; Antón Segurado, R.; Vázquez Fernández, E.; Gómez Dopazo, M.; et al. Ermeloite, AlPO4⋅H2O a new phosphate mineral with kieserite-type structure from Galicia, Spain. Mineral. Mag. 2024, 88, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. Colomeraite, IMA 2021-061. CNMNC Newsletter 63. Eur. J. Mineral. 2021, 33, 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cortés, Á.; Vegas, J.; Carcavilla, L.; Díaz-Martínez, E. Conceptual Base and Methodology of the Spanish Inventory of Sites of Geological Interest (IELIG); Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Madrid, Spain, 2019; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- IGME–CSIC. Inventario Español de Lugares de Interés Geológico (IELIG). Available online: https://info.igme.es/ielig/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Villalobos, M.; Braga, J.C.; Guirado, J.; Pérez, A.B. El inventario andaluz de georrecursos culturales: Criterios de valoración. De Re Met. 2004, 3, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Europarc. Anuario 2023 del Estado de las Áreas Protegidas en España; Fundación González Bernáldez: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, K.M. Guidelines for boundary stratotypes. Episodes 1986, 9, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | TM | RTM | MS | RMS | Area (S) (km2) | Ratio 1 (MS/TM) | Ratio 2 (MT × 104/S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 908 | 1 | 2810 | 1 | 9,826,675 | 3.09 | 0.92 |

| Russia | 894 | 2 | 2701 | 2 | 17,098,242 | 3.02 | 0.52 |

| Italy | 397 | 3 | 1824 | 4 | 301,338 | 4.59 | 13.17 |

| Germany | 384 | 4 | 1916 | 3 | 357,121 | 4.99 | 10.75 |

| Canada | 260 | 5 | 1736 | 5 | 9,984,670 | 6.68 | 0.26 |

| Sweden | 194 | 6 | 946 | 18 | 450,295 | 4.88 | 4.31 |

| Australia | 189 | 7 | 1538 | 6 | 7,692,024 | 8.14 | 0.25 |

| China | 182 | 8 | 1478 | 7 | 9,596,961 | 8.12 | 0.19 |

| Japan | 161 | 9 | 1412 | 8 | 377,944 | 8.77 | 4.26 |

| Czech Republic | 155 | 10 | 1389 | 9 | 78,866 | 8.96 | 19.65 |

| Chile | 147 | 11 | 816 | 25 | 756,096 | 5.55 | 1.94 |

| France | 128 | 12 | 1357 | 10 | 564,690 | 10.6 | 2.27 |

| UK | 120 | 13 | 1079 | 13 | 243,610 | 8.99 | 4.93 |

| Namibia | 109 | 14 | 858 | 23 | 825,515 | 7.87 | 1.32 |

| Dr Congo | 103 | 15 | 469 | 37 | 2,345,410 | 4.55 | 0.44 |

| Switzerland | 94 | 16 | 902 | 20 | 41,285 | 9.6 | 22.77 |

| Mexico | 91 | 17 | 806 | 26 | 1,972,550 | 8.86 | 0.46 |

| Norway | 89 | 18 | 985 | 16 | 385,178 | 11.07 | 2.31 |

| Denmark | 87 | 19 | 573 | 33 | 2,210,401 | 6.59 | 0.39 |

| South Africa | 84 | 20 | 965 | 17 | 1,221,037 | 11.49 | 0.69 |

| Kazakhstan | 79 | 21 | 744 | 28 | 2,724,900 | 9.42 | 0.29 |

| Brazil | 78 | 22 | 942 | 19 | 8,515,767 | 12.08 | 0.09 |

| Tajikistan | 64 | 23 | 458 | 38 | 143,100 | 7.16 | 4.47 |

| Israel | 58 | 24 | 260 | 50 | 20,770 | 4.48 | 27.92 |

| Argentina | 55 | 25 | 861 | 22 | 2,780,400 | 15.65 | 0.2 |

| Austria | 53 | 26 | 1183 | 12 | 83,855 | 22.32 | 6.32 |

| Bolivia | 51 | 27 | 546 | 34 | 1,098,581 | 10.71 | 0.46 |

| Greece | 47 | 28 | 1,000 | 15 | 131,957 | 21.28 | 3.56 |

| Spain | 37 | 29 | 1262 | 11 | 505,992 | 34.11 | 0.73 |

| Finland | 36 | 30 | 730 | 29 | 338,424 | 20.28 | 1.06 |

| Romania | 35 | 31 | 852 | 24 | 238,391 | 24.34 | 1.47 |

| Poland | 32 | 32 | 1048 | 14 | 312,679 | 32.75 | 1.02 |

| Peru | 32 | 33 | 427 | 41 | 1,285,216 | 13.34 | 0.25 |

| Morocco | 30 | 34 | 581 | 32 | 446,550 | 19.37 | 0.67 |

| Slovakia | 28 | 35 | 872 | 21 | 49,035 | 31.14 | 5.71 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 25 | 36 | 294 | 48 | 199,951 | 11.76 | 1.25 |

| India | 22 | 37 | 648 | 31 | 3,287,590 | 29.45 | 0.07 |

| Madagascar | 18 | 38 | 389 | 42 | 587,041 | 21.61 | 0.3 |

| Belgium | 18 | 39 | 363 | 44 | 30,230 | 20.17 | 5.95 |

| North Macedonia | 18 | 40 | 299 | 47 | 25,713 | 16.61 | 7.00 |

| Antarctica * | 17 | 41 | 383 | 43 | 14,000,000 | 22.53 | 0.01 |

| Uzbekistan | 17 | 42 | 329 | 45 | 447,400 | 19.35 | 0.38 |

| Portugal | 15 | 43 | 769 | 27 | 92,090 | 51.27 | 1.63 |

| Tanzania | 15 | 44 | 300 | 46 | 947,303 | 20 | 0.16 |

| Jordan | 15 | 45 | 194 | 51 | 89,342 | 12.93 | 1.68 |

| New Zealand | 14 | 46 | 495 | 36 | 268,021 | 35.36 | 0.52 |

| Turkey | 13 | 47 | 431 | 40 | 783,562 | 33.15 | 0.17 |

| Hungary | 12 | 48 | 684 | 30 | 93,090 | 57 | 1.29 |

| Ukraine | 12 | 49 | 524 | 35 | 603,500 | 43.67 | 0.20 |

| Iran | 12 | 50 | 448 | 39 | 1,648,195 | 37.33 | 0.07 |

| Myanmar | 11 | 51 | 269 | 49 | 676,578 | 24.45 | 0.16 |

| Mineral | Composition | Type | Year | Type Location (Reference) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aragonite | Ca(CO3) | G | 1791 | Molina de Aragón, Guadalajara [20] |

| 2 | Andalusite | Al2SiO5 | G | 1798 | El Cardoso de la Sierra, Guadalajara [21] |

| 3 | Rutile | TiO2 | G | 1803 | Horcajuelo de la Sierra, Madrid [22] |

| 4 | Glauberite | Na2Ca(SO4)2 | G | 1808 | Villarrubia de Santiago, Toledo [23] |

| 5 | Linarite | CuPb(SO4)(OH)2 | G | 1822 | Linares, Jaén [24] |

| 6 | Calomel | HgCl | G | 1825 | Almadén, Ciudad Real [25] |

| 7 | Conichalcite | CaCu(AsO4)(OH) | G | 1849 | Hinojosa del Duque, Córdoba [26] |

| 8 | Morenosite | Ni(SO4)·7H2O | G | 1851 | Cedeira, A Coruña [27] |

| 9 | Zaratite | Ni3(CO3)(OH)4·4H2O | Q | 1851 | Cedeira, A Coruña [28] |

| 10 | Zinkosite | Zn(SO4) | G | 1852 | Cuevas del Almanzora, Almería [29] |

| 11 | Ferberite | Fe2+(WO4) | G | 1863 | Cuevas del Almanzora, Almería [30] |

| 12 | Bolivarite | Al2(PO4)(OH)3·4H2O | Q | 1921 | Pontevedra [31] |

| 13 | Cervantite | Sb3+Sb5+O4 | Rd | 1962 | Cervantes, Lugo [32] |

| 14 | Rodalquilarite | H3Fe3+2(Te4+O3)4Cl | A | 1967 | Nijar, Almeria [33] |

| 15 | Yagiite | NaMg2(AlMg2Si12)O30 | A | 1968 | Colomera meteorite [34] |

| 16 | Westerveldite | FeAs | A | 1971 | Ojen, Malaga [35] |

| 17 | Jarosite | KFe3+3(SO4)2(OH)6 | Rd | 1987 | Cuevas del Almanzora, Almería [36] |

| 18 | Aerinite | (Ca,Na)6(Fe3+,Fe2+,Mg,Al)4(Al,Mg)6Si12O36 (OH)12(CO3)·12H2O | Rd | 1988 | Estopiñán del Castillo, Huesca [37] |

| 19 | Villamaninite | CuS2 | Rd | 1989 | Cármenes, Leon [38] |

| 20 | Saliotite | (Li,Na)Al3(Si3Al)O10(OH)5 | A | 1990 | Nijar, Almeria [39] |

| 21 | Barquillite | Cu2(Cd,Fe)GeS4 | A | 1996 | Villar de la Yegua, Salamanca [40] |

| 22 | Moganite | SiO2·nH2O | Rn | 1999 | Mogán, Las Palmas [41] |

| 23 | Calderonite | Pb2Fe3+(VO4)2(OH) | A | 2001 | Santa Marta, Badajoz [42] |

| 24 | Cobaltarthurite | CoFe3+2(AsO4)2(OH)2·4H2O | A | 2001 | Mazarrón, Murcia [43] |

| 25 | Barahonaite–(Al) | (Ca,Cu,Na,Fe3+,Al)12Al2 (AsO4)8(OH,Cl)x·nH2O | A | 2006 | Mazarrón, Murcia [44] |

| 26 | Barahonaite–(Fe) | (Ca,Cu,Na,Fe3+,Al)12 Fe3+2(AsO4)8(OH,Cl)x·nH2O | A | 2006 | Mazarrón, Murcia [44] |

| 27 | Suhailite | (NH4)Fe2+3(Si3Al)O10(OH)2 | A | 2007 | Mijas, Malaga [45] |

| 28 | Natropharmacoalumite | NaAl4(AsO4)3(OH)4·4H2O | A | 2010 | Nijar, Almeria [46] |

| 29 | Chlorapatite | Ca5(PO4)3Cl | Rn | 2010 | Cabo de Gata, Almeria [47] |

| 30 | Fluorapatite | Ca5(PO4)3F | Rn | 2010 | Cabo de Gata, Almeria [47] |

| 31 | Hydroniumpharmaco-alumite | (H3O)Al4(AsO4)3(OH)4 ∙4.5H2O | A | 2012 | Nijar, Almeria [48] |

| 32 | Ferri-pedrizite | NaLi2(Mg2Fe3+2Li)Si8O22(OH)2 | Rd | 2012 | Manzanares el Real, Madrid [49] |

| 33 | Clino-ferro-ferri-holmquistite | Li2(Fe2+3Fe3+2)Si8O22(OH)2 | Rd | 2012 | Manzanares el Real, Madrid [50] |

| 34 | Ferro-ferri-pedrizite | NaLi2(Fe2+2Fe3+2Li)Si8O22(OH)2 | Rd | 2012 | Manzanares el Real, Madrid [50] |

| 35 | Potassic-ferro-taramite | K(NaCa)(Fe2+3Al2)(Si6Al2)O22 (OH)2 | Rd | 2012 | Bédar, Almeria [51] |

| 36 | Abellaite | NaPb2(CO3)2(OH) | A | 2014 | Torre de Cabdella, Lleida [52] |

| 37 | Clino-ferri-holmquistite | Li2(Mg3Fe3+2)Si8O22(OH)2 | A | 2014 | Manzanares el Real, Madrid [53] |

| 38 | Thenardite | Na2(SO4) | Rn | 2014 | Ciempozuelos, Madrid [54] |

| 39 | Fehrite | MgCu4(SO4)2(OH)6∙6H2O | A | 2018 | Pechina, Almeria [55] |

| 40 | Alcantarillaite | [Fe3+0.5(H2O)4][CaAs3+2(Fe3+2.5W6+0.5)(AsO4)2O7] | A | 2019 | Balalcázar, Cordoba [56] |

| 41 | Ermeloite | Al(PO4)·H2O | A | 2021 | Moaña, Pontevedra [57] |

| 42 | Colomeraite | NaTi3+Si2O6 | A | 2021 | Colomera meteorite [58] |

| Mineral | Generated Geosite | Threatened Conservation | In Protected Space | Educational and/or Tourist Potential | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aragonite | 1 | No | World Geopark of UNESCO | Yes; signposted |

| 2 | Andalusite | No | No | Natural Park | Yes |

| 3 | Rutile | No | No | Biosphere Reserve | Yes |

| 4 | Glauberite | 2 | No | No | Yes |

| 5 | Linarite | No | - | No | - |

| 6 | Calomel | 3 | No | UNESCO World Heritage | Yes |

| 7 | Conichalcite | No | - | No | No |

| 8 | Morenosite | No | Yes | World Geopark of UNESCO | - |

| 9 | Zaratite | No | Yes | World Geopark of UNESCO | - |

| 10 | Zinkosite | 4 | Yes | Natural area | Yes |

| 11 | Ferberite | 5 | - | Spatial Conservation Zone (Red Natura 2000) | Yes |

| 12 | Bolivarite | 6 | Yes | No | - |

| 13 | Cervantite | No | - | Special Protection Area for Natural Values | - |

| 14 | Rodalquilarite | 7 | No | UNESCO Global Geopark Natural Park Biosphere Reserve | Yes |

| 15 | Yagiite | No | - | - | - |

| 16 | Westerveldite | 8 | Yes | Biosphere Reserve | Yes |

| 17 | Jarosite | 4 | Yes | Natural area | Yes |

| 18 | Aerinite | 9 | No | No | Yes |

| 19 | Villamaninite | 10 | No | Biosphere Reserve | Yes |

| 20 | Saliotite | 11 | No | No | Yes |

| 21 | Barquillite | 12 | - | No | No |

| 22 | Moganite | 13 | No | Biosphere Reserve | Yes |

| 23 | Calderonite | 14 | No | No | Yes |

| 24 | Cobaltarthurite | 15 | No | No | Yes |

| 25 | Barahonaite- (Al) | 15 | No | No | Yes |

| 26 | Barahonaite- (Fe) | 15 | No | No | Yes |

| 27 | Suhailite | 16 | Yes | No | Yes |

| 28 | Natropharmacoalumite | 17 | No | Idem 14 | Yes |

| 29 | Chlorapatite | No | - | Idem 14 | - |

| 30 | Fluorapatite | No | - | Idem 14 | - |

| 31 | Hydroniumpharmacoalumite | 17 | No | Idem 14 | Yes |

| 32 | Ferri-pedrizite | 18 | No | National Park | Yes |

| 33 | Clino-ferro-ferri-holmquistite | 18 | No | National Park | Yes |

| 34 | Ferro-ferri-pedrizite | 18 | No | National Park | Yes |

| 35 | Potassic-ferro-taramite | 19 | - | No | - |

| 36 | Abellaite | 20 | - | No | Yes |

| 37 | Clino-ferri-holmquistite | 18 | No | National Park | Yes |

| 38 | Thenardite | 21 | No | BIC | Yes |

| 39 | Fehrite | 22 | - | Natural Park | - |

| 40 | Alcantarillaite | 23 | Yes | No | - |

| 41 | Ermeloite | 24 | Yes | No | - |

| 42 | Colomeraite | No | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Martínez, R.; Carcavilla, L.; López-Martínez, J.; Monasterio, J.M.; Hermosilla, H. To What Extent Are the Type Localities of Minerals Part of Geological Heritage? A Global Review and the Case of Spain as an Example. Heritage 2025, 8, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080314

Jiménez-Martínez R, Carcavilla L, López-Martínez J, Monasterio JM, Hermosilla H. To What Extent Are the Type Localities of Minerals Part of Geological Heritage? A Global Review and the Case of Spain as an Example. Heritage. 2025; 8(8):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080314

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Martínez, Ramón, Luis Carcavilla, Jerónimo López-Martínez, Juan Manuel Monasterio, and Hugo Hermosilla. 2025. "To What Extent Are the Type Localities of Minerals Part of Geological Heritage? A Global Review and the Case of Spain as an Example" Heritage 8, no. 8: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080314

APA StyleJiménez-Martínez, R., Carcavilla, L., López-Martínez, J., Monasterio, J. M., & Hermosilla, H. (2025). To What Extent Are the Type Localities of Minerals Part of Geological Heritage? A Global Review and the Case of Spain as an Example. Heritage, 8(8), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080314