1. Introduction

An artistic and cultural manifestation such as architecture is the consequence of a great diversity of interrelated factors: contextual, religious, artistic, cultural, social, and political. These elements act as semiotic layers that allow a polysemic interpretation of the architectural object. Among the most influential architectural movements in world history, the Renaissance in Europe gave rise to a comprehensive architectural theory grounded in classical antiquity, humanism, and mathematical rationality. Emerging in the 15th century, Renaissance architectural theory systematized a set of principles aimed at restoring and surpassing the achievements of ancient Greek and Roman architecture.

At its core, Renaissance architectural thought emphasized harmony, proportion, and order. Constructions were designed to reflect mathematical precision, often using geometric ratios inspired by Vitruvius’ De Architectura and later developed in treatises such as Leon Battista Alberti’s De Re Aedificatoria and Andrea Palladio’s I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura.

These texts articulated a design vocabulary based on symmetry and centralized spatial planning. Furthermore, Renaissance architecture employed linear perspective, enabling a coherent representation of three-dimensional space and creating a structured visual experience based on rational logic and aesthetic clarity.

These Renaissance architectural principles strongly influenced the architecture introduced to China by Jesuit missionaries at the beginning of the Qing dynasty. As part of their evangelizing mission, the Jesuits engaged in a process of inculturation, which in the realm of architecture aimed to reconcile Western formalism with Chinese spatial, symbolic, and visual traditions. This exchange occurred through several specific channels of transmission [

1,

2].

First and foremost, Jesuit missionaries, such as Matteo Ricci, Johann Adam Schall von Bell, and Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining), acted as intermediaries between European scientific and artistic knowledge and the Chinese imperial court. They brought with them not only religious texts but also architectural treatises, engraved illustrations and perspective drawings. These visual and material forms of knowledge allowed ideas to circulate across linguistic and conceptual boundaries. Particularly during the reigns of emperors Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong, Jesuits were commissioned to participate in court projects, resulting in the creation of hybrid structures within imperial spaces such as the gardens and palaces of the Yuanmingyuan.

However, the dissemination of Renaissance ideas in China was far from unilateral. The Chinese craftsmen who executed these works played an essential role in interpreting and transforming foreign concepts according to local practices. These structures combined European surface ornamentation and geometric planning with Chinese construction techniques and symbolic traditions. Consequently, the overall architectural style upholds harmony and stability, striving to create symmetries and building its aesthetic effect on the foundation of mathematics and perspective [

3].

According to Le Corbusier: “Architecture only exists when there is a poetic emotion. Architecture is a plastic thing. I mean by plastic what is seen and measured by the eyes” [

4]. This resonates with the visual and symbolic focus of Qing palace architecture, where the impact of architecture lay not only in its function or structure but in its capacity to evoke emotion, status, and meaning. Herbert Read similarly underscores the symbolic discourse inherent in architectural forms [

5], which further illustrates why Jesuit efforts succeeded most profoundly not in replicating European buildings, but in appealing to Chinese notions of visual order and imperial grandeur.

In this encounter, the original strategy was infiltrated by Jesuit missionaries, particularly in the palaces and royal gardens of the Qing Dynasty during the process of inculturation. From an architectural perspective, the Qing Dynasty can be regarded as the most remarkable period of palace architecture and royal garden design in imperial China.

In conclusion, the cultural encounter between European and Chinese architecture during the Qing dynasty reveals a rich and dynamic process of convergence. It was not a matter of stylistic transplantation, but rather an intercultural negotiation shaped by Chinese aesthetics, Renaissance architectural theory, and mutual technological curiosity [

6,

7]. Advances in science, engineering, and the visual arts [

8], especially in architecture and painting, culminated in an extraordinary period of artistic innovation that stands as a testament to the possibilities of cross-cultural synthesis.

Western Constructions as Object of Study

Geremie R. Barmé in [

9] provides detailed information about the Yuanmingyuan, commonly translated as

the Garden of Perfect Brightness, describing it as a complex of gardens and palaces located approximately twelve kilometres northwest of central Beijing. Additionally, sources [

10,

11] offer further insights into the extensive history of the Yuanmingyuan. The number “9” is regarded as “the number of completeness and perfection” and “the highest digit, symbolising completeness and culmination”. Other symbolic meanings are discussed by Cary Y. Liu in [

12]. Moreover, the most comprehensive European account of the Chinese imperial gardens was provided by the Jesuit Jean-Denis Attiret in

Lettres édifiantes et curieuses de Chine par des missionnaires jésuites [

13].

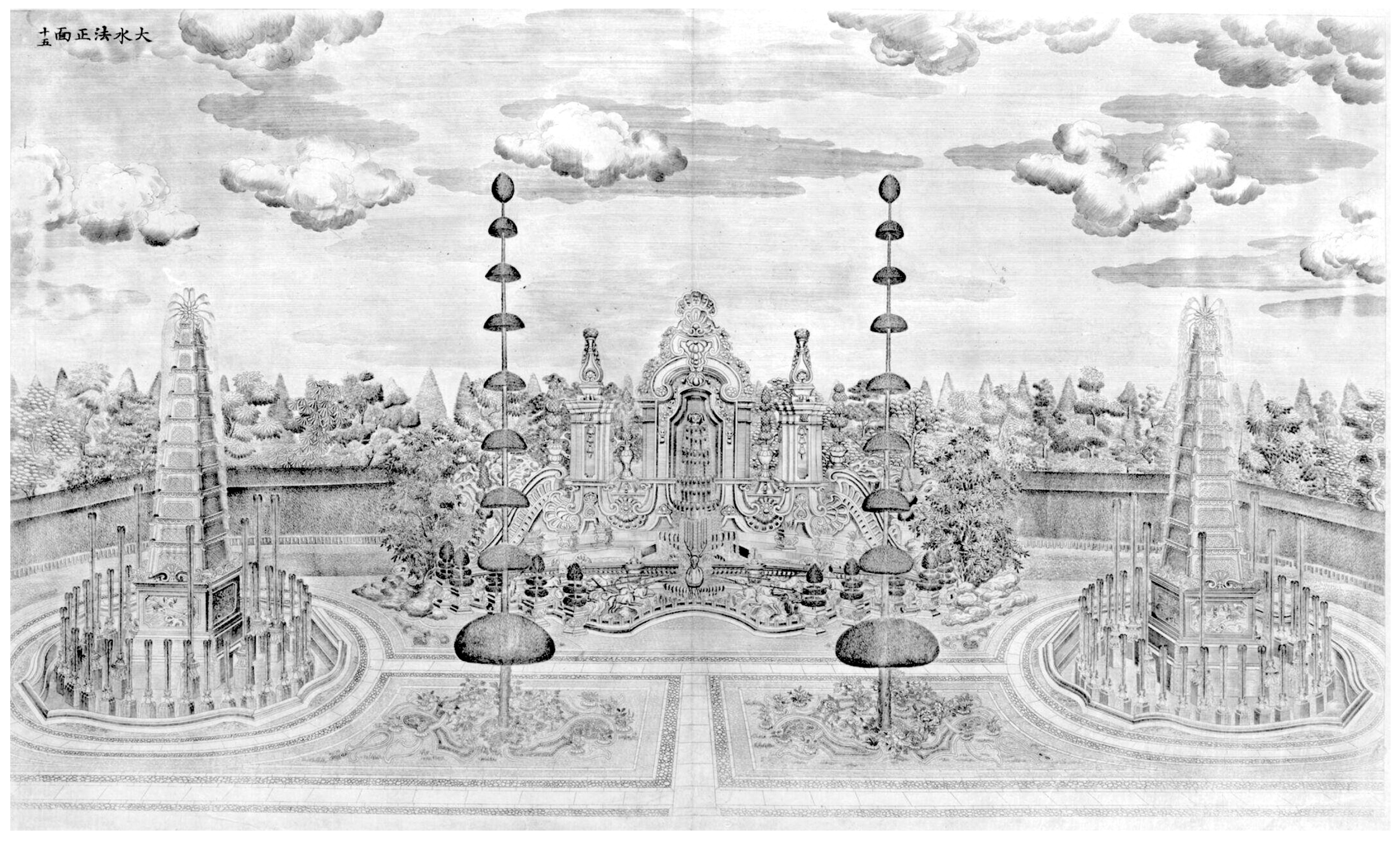

Consequently, these Western Constructions or European Palaces are situated at the northern end of the Eternal Spring Garden and represent one of the most extraordinary garden projects in Chinese architectural history [

14]. The European scenery, pavilions, and gardens are depicted in

Figure 1, arranged from west to east.

The architect and artist responsible for the design of the monumental project was the Jesuit architect Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766), who introduced novel concepts to the Qing court and combined them with those of Chinese tradition. Consequently, he established novel approaches of architectural and art expression between East Asia and the West.

G. Castiglione was a pioneering figure in the implementation and execution of the monumental architectural project, which culminated in the construction and decoration of the European Palaces (Western constructions) at the Garden of Perfect Brightness in Beijing. The Jesuit’s projective dimension embodies the extraordinary influence of Western architecture. Susan Naquin succinctly captures this notion, stating: “Today, he is regarded as a man who fused Western and Chinese artistic elements to establish a distinctive high Qing court style” [

15].

Symbolism is arguably one of the most significant characteristics of the Architectural Encounter between Europe and China. Through the use of symbolism, the Jesuits, including Giuseppe Castiglione, who possessed a deep understanding of both Chinese and Christian symbolism, meticulously planned and designed the structures to satisfy the emperor’s desires [

16]. This approach may have had the potential to facilitate the spread of Christianity [

17]. As George Robert Loehr highlights, the architect remained faithful to Chinese symbolism, yet it is plausible that the architects and missionaries deliberately incorporated characteristics that appealed to the emperor, thereby creating opportunities for apostolic action [

18]. In this sense, G.M. Thomas analyses artistic interactions between Europe and China, specifically focusing on China’s Yuanmingyuan imperial palace complex [

19]. “A single site of artistic interaction between Europe and China in the eighteenth century. It centres on China’s greatest imperial palace complex, the Yuanmingyuan, built near Beijing in the eighteenth century and destroyed by the British army in 1860 to bring the Second Opium War to a decisive end”.

Although not a religious imposition but rather a cultural matter, symbolism in this architecture was one of the most significant contributions of the Jesuits to “Qing architecture”. Accordingly, this study aims to explore and interpret one of its defining characteristics: The symbolic function of architecture. In this context, the Yuanmingyuan functioned as a powerful emblem of imperial authority, conveyed through its grand architectural scale and spatial composition. Among its most significant elements was the complex of European Palaces, conceived and designed by Guiseppe Castiglione, which played a central role in this symbolic narrative.

The genesis of these palatial structures can be attributed to Emperor Qianlong’s (1735–1796) profound fascination with European garden aesthetics. This interest extended beyond the baroque stylistic elements to encompass the sophisticated engineering feats associated with the transportation of water to grand fountains. In this regard, Cecile and Michel Beurdeley have documented that historical evidence suggests Castiglione, a Jesuit architect, presented the emperor with designs embodying a captivating form of Baroque, evocative of Borromini’s style [

20].

Jin, in his monograph [

21], articulates that these constructions embody principles of the Italian Renaissance, adorned with Baroque ornamental features, subtly integrated with traditional Chinese motifs such as bamboo pavilions, Liuli tiles, and Taihu rocks. Further, E. Corsi [

22] offers an analytical perspective on the Jesuits’ role in the development and dissemination of linear perspective within China. The distinctly Italianate character of these European palaces is further examined in the scholarship of Michèle Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens [

23]. There is broad consensus regarding the significant influence of the Renaissance and Baroque periods on the planning and execution of the Western Mansions. The underlying design strategy was characterized by the use of orthogonal axes, bilateral symmetry, and grid-based compositions. Based on these principles, Jesuits such as Giuseppe Castiglione and Father Benoist played a central role in transmitting the designs of these remarkable architectural settings.

Significant scholarly contributions include Hui Zou’s exploration of the architectural symbolism inherent in European palatial forms [

24], alongside an examination of the roles played by three pivotal emperors [

25]. Castilla [

26] elucidates the innovative prowess of G. Castiglione, positioning him as a forerunner in the early stages of pictorial–architectural globalisation, as reflected in the design and construction of these palaces. Qingyu’s original research [

27] delves into the Yuanmingyuan, with a particular focus on the European Palaces therein.

Lastly, Kristina Kleutghen [

28] observes: “The range of eighteenth-century occidentalizing Chinese art is vast, and these few examples are only a tiny fraction of what exists […] Much remains to be investigated, especially how these objects contributed to perceptions of the West”. This compelling assertion has significantly influenced the direction of the present research, aimed at addressing numerous questions pertaining to intercultural interactions between Eastern and Western traditions bridging these two worlds.

2. Research Methodology

The research methodology is designed to provide comprehensive documentation and interpretive analysis of the architectural elements that characterize, in general form, the principal features of the Western Constructions’ pavilions (

Figure 1). This methodological approach combines historical analysis with qualitative interpretation to explore both the physical and symbolic dimensions of architectural hybridity in the context of East–West cultural interaction.

As a conceptual foundation for analysing historical symbols and their transformations, the research adopts a multidimensional framework, illustrated in

Figure 2.

The convergence of these sets (Set 4) forms the basis for a nuanced cultural synthesis analysis, enabling an understanding of how disparate architectural languages and symbol systems were negotiated and integrated in the construction of the Yuanmingyuan pavilions.

Historical and Archival Research Scope

The historical approach is particularly appropriate for this study, as it enables a deeper understanding of how architectural features and symbolic elements reflect their socio-cultural and historical context. The methodology includes archival research conducted at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, where the author consulted a range of primary and secondary sources. The selection and interpretation of historical materials was consistently focused on the European-style gardens constructed in the northwestern sector of the Yuanmingyuan. Given that SOAS is recognized as the world’s leading institution for the study of Asia and Africa, the conclusions drawn from this research, many of which are presented in this work, underscore both the objectivity and the historical fidelity of the interpretations offered. These encompassed the following elements:

Original architectural drawings and sketches.

Historical photographs documenting the Yuanmingyuan before and after its destruction.

Contemporary accounts, reports, and correspondence by Jesuit missionaries.

Scholarly articles and publications on Qing dynasty court architecture and missionary activity.

Interpretation of these materials followed a contextual and comparative approach, examining the architectural symbolism, material techniques, and cultural meanings embedded in the visual representations. This was reinforced by secondary literature from both Chinese and Western sources to support balanced interpretation.

By applying this integrated and reflexive methodology, the research not only captures the physical attributes of the pavilions and gardens but also situates them within the broader narrative of Chinese cultural heritage, architectural inculturation, and the cross-cultural dialogue between Qing China and Renaissance Europe. As noted by Kiani and Khakzand [

29], such symbolic landscapes demand an understanding of dualities—spatial–temporal and objective–subjective—that underpin the structural identity of traditional Chinese gardens.

Through this comprehensive methodological design, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of architectural convergence, cultural negotiation, and the preservation of hybrid heritage [

30,

31].

In the following section, an overview is provided outlining some of the most prominent elements and symbols, their respective cultural backgrounds, and the contexts in which they were manifested.

3. The Influence of Renaissance Theoretical Trends on the Design of the European Palaces

3.1. Symmetry, Rhythm and Proportion

Giuseppe Castiglione had the virtue of understanding the relationship between Chinese and Christian symbolism, and together with his fellow missionaries, he decided to define the characteristics of what would flatter the emperor and at the same time be opportune for his missionary mission. However, this characteristic was not a religious imposition but a cultural issue. Castiglione designed palaces and architecture in line with classic Italian villas, based on linear perspective, rhythm, and proportion [

32]. Thus, the Italian Renaissance space sequence reflects the rational poetics of gardens of the European Palaces (Western constructions). A notable example of symmetry and proportion was the design of the Xieqiqu pavilion,

Figure 3, the façade of which features a set of columns and pilasters of harmonious proportions and bilateral symmetry, as well as numerous Baroque-style decorative details. Among these characteristics, the symmetry, rhythm, proportion, and harmony are noteworthy, as well as the repetition of elements at regular intervals [

33].

Giuseppe Castiglione possessed a profound understanding of the symbology between Chinese and Christian traditions. Collaborating with his fellow missionaries, he endeavoured to discern the characteristics that would align with the emperor’s preferences while simultaneously facilitating his missionary objectives. However, this criterion was not a religious imposition but a cultural consideration. Castiglione meticulously designed palaces and architectural structures that conformed to the principles of classical Italian villas, employing linear perspective, rhythm, and proportion. Consequently, the Italian Renaissance spatial sequence mirrors the rational aesthetics of gardens found in Western constructions.

3.2. The Garden

In the history of Chinese imperial gardens, the European garden or European-style palaces in Beijing stand as the pioneering fusion of traditional Chinese garden design with Italian influences. This garden conveys a dual message: rhythm and proportion, reminiscent of the labyrinths adorning classic Italian villas of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Renowned European architects such as Guarino Guarini and Borromini, among others, could have served as inspirational guides and design principles for Castiglione’s work. Initially, Renaissance linear perspective was employed, followed by the integration of the garden and monumentality into traditional Chinese cultural norms. This fusion aimed to create a geometric garden with distinct Eastern and Western influences. Castiglione’s designs were crafted in a Baroque style, incorporating ornamental and architectural elements that drew inspiration from the works of these architects.

A realistic conception adapted to the design and construction of Italian Renaissance gardens can be found in [

34]. The symbolic dimension of Chinese imperial gardens can be partially understood through their orientation, particularly the principle of receiving light from the south. This orientation, deeply rooted in Confucian traditions, was not merely a practical consideration but a metaphysical one. As such, receiving light from the south was believed to provide protection for the emperor against the intricate and sinuous characterisation of the garden.

3.3. The Water

Water is an integral element of Chinese gardens, manifesting in the form of streams, (dragon veins), water games, and lakes (seas). The dragon, a prominent symbol in Chinese legends, myths, and traditions, holds significant importance.

The inclusion of lakes or “seas” within garden complexes such as the Yuanmingyuan also held symbolic resonance. In contrast to the stability implied by architectural symmetry and axial planning, water provided a counterbalance of spontaneity and natural transformation, encouraging contemplation and harmonizing the physical with the metaphysical. Water can express a wide range of emotions, including instability, immediacy, contemplation, eternity, and longing [

35]. For Guo Xi, water is a vital element that enlivens mountains, beautifies grass and trees, and creates a “charming and elegant” atmosphere with mist and fog [

36].

3.4. The Linear Perspective: “Xianfa”

The technique employed by Jesuit artists in the Chinese transformation of European linear mathematical perspective was known as

xianfa [

22,

37]. This technique directly relates to depth and foreshortening achieved by lines converging at a focal point (vanishing point). This technique clearly corresponds to Western culture, where the visualisation of an image is predominantly through the senses, particularly sight.

From a Chinese perspective, each artist possessed a distinct vision of distances, erroneously referred to as “perspectives.” Thus, it is inaccurate to label xianfa as perspective, as it would diminish its spiritual character from a Chinese viewpoint and solely base its meaning on geometric concepts. According to this criterion, its interpretation aligns with one of the three distances proposed by Guo Xi (1020–1090) for landscape painting: deep, high, and level distance. In this context, I specifically refer to deep distance, understood as that which transcends physical space and penetrates the spiritual realm that constitutes the very essence of nature.

In this manner, xianfa can be defined as the confluence of European linear mathematical perspective with the influence of the spirit of Chinese art. To the symbolism and sensibility of the Asian mentality, Castiglione incorporated the enigmatic nature that encompasses the European linear mathematical perspective. The utilisation of xianfa, in addition to capturing reality based on linear mathematical perspective, could also evoke a journey within the viewer’s mind, connected to the Daoist philosophy, along the intricate pathways of the garden. This method bridged the religiosity of the Jesuits with Chinese cosmology, as the vanishing point or infinity point was associated with the origin of the world in the strictest interpretation of Daoism, while for the Jesuits, the vanishing point led to the glory of God.

3.5. The Dome

Similar to the symbolic significance of the dome in ancient European architecture, the roof in classical Chinese architecture was distinguished by its pyramidal form, encapsulating both aesthetic and practical importance,

Figure 4a. However, the existing dome in the hexagonal gazebo at the centre of the garden named “the Labyrinth” exhibits a structural fusion of Chinese and Western architectural influences, as depicted in

Figure 4b. The dome’s support was constructed from six ribbed arches characterised by curved edges, adhering to the Renaissance aesthetic.

A particularly noteworthy element within the spatial and symbolic composition of the Yuanmingyuan gardens is the gazebo, which functioned as both a geometric anchor and a metaphysical focal point. This structure, hexagonal in form, was positioned as the vanishing point within the broader compositional logic of the garden’s design, an approach clearly informed by European traditions of linear perspective and spatial illusion.

The underlying design strategy appears to draw inspiration from the perspectival theories of Andrea Pozzo (1642–1709), an Italian Jesuit painter and architect renowned for his work on illusionistic space in both architecture and painting. In his influential treatise Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum (1693–1700), Pozzo formalized methods of constructing perspective that could extend space and guide the viewer’s eye toward a predetermined vanishing point. These ideas were widely disseminated within Jesuit networks and became central to the visual strategies of missionary art and architecture. It is therefore unsurprising that such a device would appear in a Jesuit-influenced garden setting in Qing China, where mathematical rigor and symbolic meaning were harmonized in architectural practice.

Within this framework, the hexagonal gazebo served multiple roles. Geometrically, it marked the central point of convergence for the orthogonal axes and grid-based composition of the garden, forming a perspectival culmination point that ordered the viewer’s visual field. Its placement within the garden thus established a clear spatial hierarchy, anchoring surrounding elements and guiding movement through the landscape according to predetermined aesthetic and symbolic logics. Its design and placement within the garden reflect a profound synthesis of European perspectival science and Chinese imperial symbolism, embodying the very essence of the intercultural architectural dialogue that defined the Western Constructions at Yuanmingyuan.

3.6. The Ornamentation

From the perspective of ornamentation, the central area of the European Palaces is the one that has the most decorative richness, with the presence of the Yuanying Guan pavilion. The main facade was designed in a post-Renaissance style, especially Baroque, and decorated with extremely rich elements [

38]. In the remains of its two lateral columns, we find the bases of the Western column design, carved with plant motifs, mainly leaves,

Figure 5a,b. In front of these columns stood two figures representing lions, “protectors of sacred buildings and defenders of the law” [

39].

Malone Carroll Brown accurately defined the style of the palaces and their decorations:

“The rococo architecture of these palace buildings recalls the extravagances of Italian art at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century. Ch’ien Lung’s European palaces contained numerous false windows and doors, excessive ornamentation in carved stone, glazed tiles in startling colour combinations, imitation shells and rock-work, meaningless pyramids, scrolls and foliage, and conspicuous outside staircases”.

5. Conclusions

This research seeks to provide an in-depth exploration and understanding of the Chinese–European Cultural Encounter at the dawn of the Qing dynasty, particularly focusing on the influence exerted by Renaissance principles on the design and conceptualisation of architecture during this period. This paper investigates how these Renaissance ideals were adapted and integrated within the specific cultural and philosophical frameworks of China, exploring both their aesthetic and symbolic significance. In particular, it underscores the vital role of inherited cultural heritage as a source of inspiration in the development of new architectural spaces and constructions, which were based on core principles such as symmetry, rhythm, proportion, and linear mathematical perspective, key elements of Renaissance thought. These principles were not merely applied in a superficial manner but were carefully woven into the fabric of Chinese architectural traditions, creating a unique synthesis of Eastern and Western ideals.

The study demonstrates that the architectural expression of the European, often seen as an isolated example of Sino-Western interaction, did not emerge from arbitrary or disparate designs of individual pavilions. Rather, the overall design of the complex was governed by a highly intentional approach, one that resulted from the intersection of European Renaissance architectural trends with the cosmological and aesthetic concepts that are fundamental to Chinese culture. In particular, the European Palaces were conceived as a geometrically structured garden that evoked multiple interpretations and layered meanings, with innumerable symbolic references embedded within its numerical and geometric components. These elements were not only expressions of technical mastery but were also intended to symbolise a powerful image of the empire as a microcosm, reflecting the harmonious relationship between the celestial and terrestrial realms, and reinforcing the emperor’s divine role as the ruler of both the earthly and spiritual worlds.

Through the detailed analysis conducted in this paper, it has been substantiated that the Palaces are best understood as an architectural manifestation of the symbiosis between Chinese cosmology and the religious and philosophical influences brought by the Jesuits during the 18th-century Chinese–European Cultural Encounter. This blending of Eastern and Western intellectual traditions resulted in an architectural form that transcended its immediate function as a royal retreat, becoming a symbolic space that mirrored the complex interactions between two distinct cultures. The Jesuit influence is seen not only in the architectural design but also in the use of mathematical and astronomical references that reflect both Western scientific thought and Chinese metaphysical beliefs.

Within this performance, the emperor’s position as the central figure is not only a political and social reality but also a symbolic manifestation of divine authority, cosmic order, and the unification of cultural and philosophical ideals. This examination of these Western constructions, therefore, highlights the intricate layers of meaning embedded within this architectural ensemble, illustrating how it serves as a cultural artefact that speaks to the broader historical, political, and intellectual currents of the period. In essence, the architectural object under analysis functions as a dynamic, multifaceted theatrical representation where the emperor assumes the role of the principal protagonist.