Biosphere Reserves in Spain: A Holistic Commitment to Environmental and Cultural Heritage Within the 2030 Agenda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background: Legitimation Theory

3. Context of This Study

4. Materials and Methods

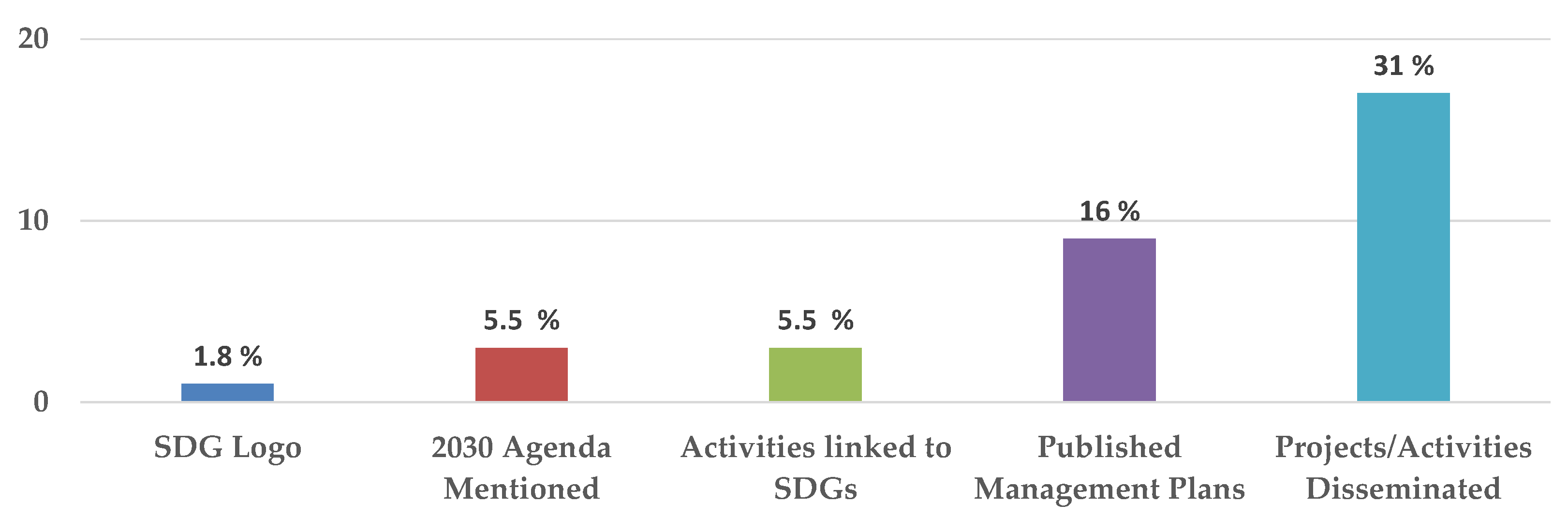

4.1. First Step: Visibility of the SDGs in the SNBRs

- (i)

- The Presence of the SDG Logo on the Official Websites:The growing importance of visually and clearly communicating a commitment to sustainability is a key factor that justifies the use of this criterion. The presence of the SDG logo on a website signals an explicit commitment to these goals and enhances visitors’ understanding of the organization’s objectives and actions.

- (ii)

- Availability of Information on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development:By their very nature, BRs are closely aligned with the principles of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. However, the way this information is presented and the extent to which the SDGs are addressed can vary significantly from one reserve to another.

- (iii)

- Accessibility of the Action Plan on the Website:All BRs are required to have a policy, action, or management plan, as this document is mandatory and serves to achieve the declared objectives of the BR in a structured and measurable manner, as stated in the Technical Guidelines for BRs [3].

- (iv)

- Dissemination of Activities Related to the SDGs:By making this information visible and sharing it, the important role that BTs play in building a more sustainable future is effectively promoted.

4.2. Second Step: The Managers’ Diagnostic

4.3. Population and Sample

5. Results

5.1. Results Regarding the Visibility

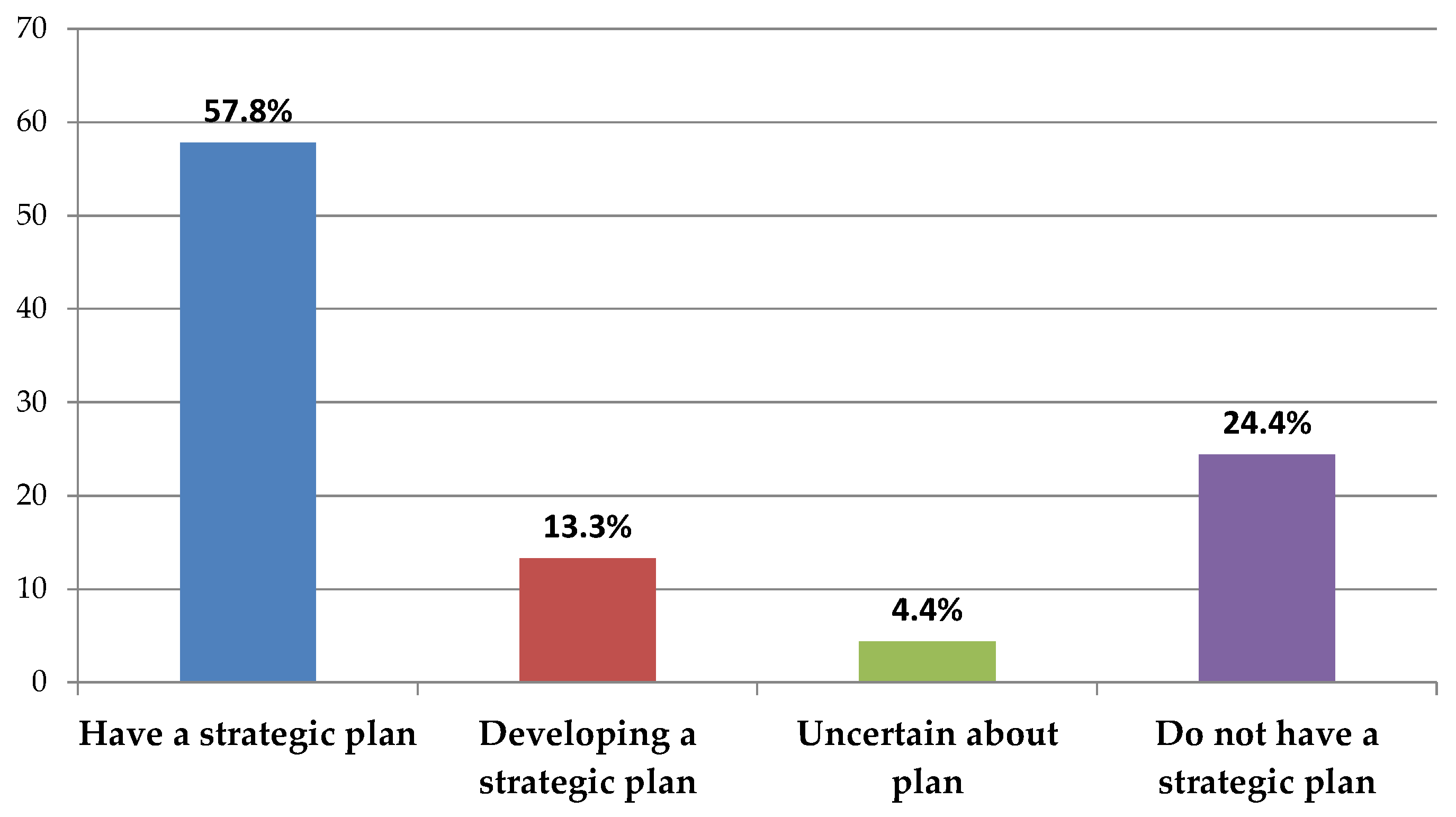

5.2. Results Regarding the Diagnostic

- Sectors

- Barriers

- Opportunities

- Interest in sustainable development

- Impact of crises

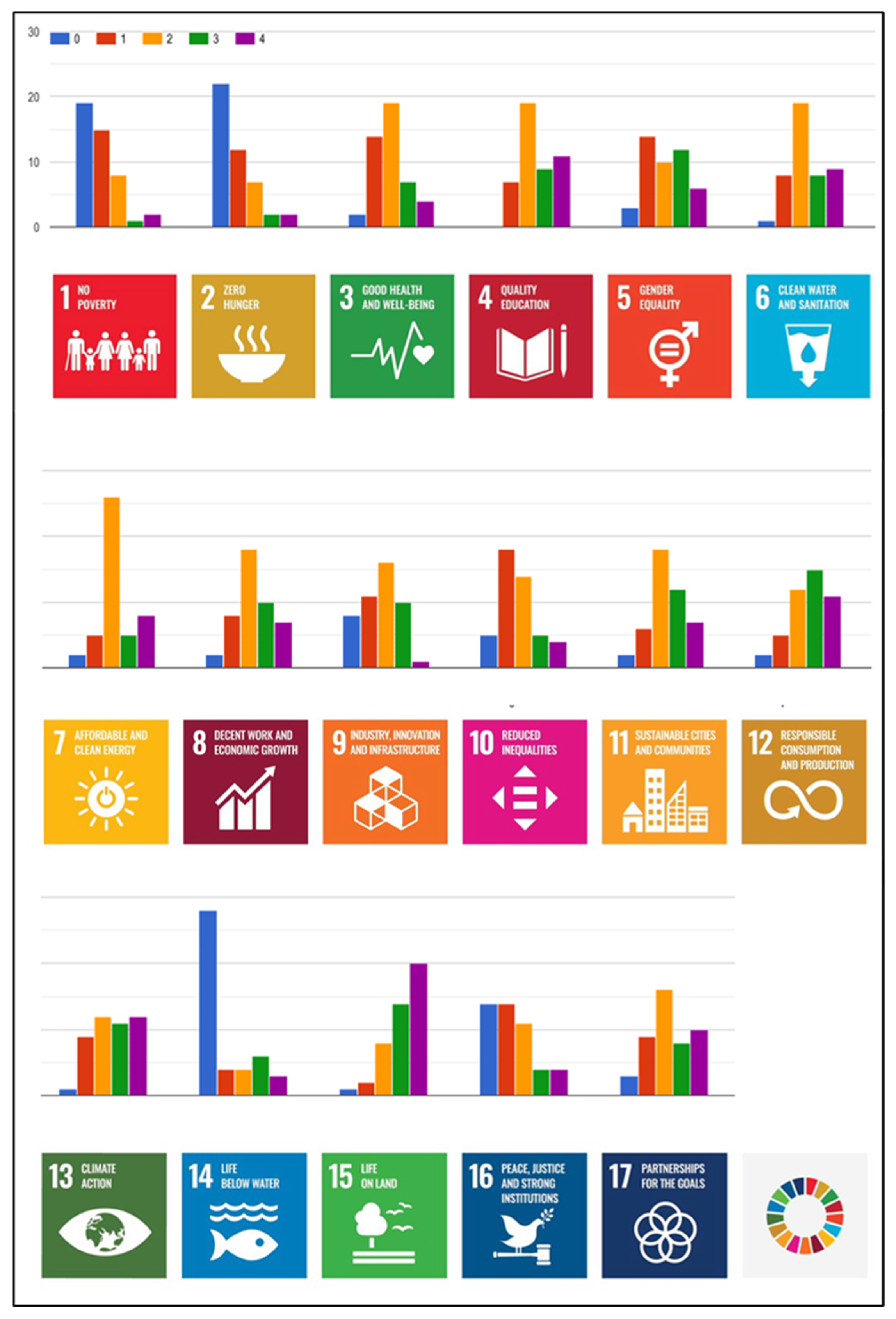

- SDG Engagement

- Actions

- -

- Education, training, and awareness-raising, which align with SDG 4 (Quality Education) and reinforce the role of Biosphere Reserves as learning sites for sustainability.

- -

- Entrepreneurship, economic incentives, and support for local responsible consumption and production, which contribute to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

- -

- Sustainable tourism and the promotion of clean energy are directly linked to SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

- -

- Health and well-being initiatives support SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), while environmental protection and ecosystem conservation are central to SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 15 (Life on Land).

- -

- Infrastructure improvement; research, development, and innovation projects; and the development of brands and designations of origin reflect efforts to enhance local identity and innovation, contributing to SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure).

- Organization and governance

- SDGs, Education, Learning, Research, and Development

- SDGs, Collaboration, and Partnerships

5.3. Successful Practices

- A good practice committed to cultural environmental heritage: Green Ring for Inclusion, a project carried on by the Tajo-Tejo International BR.

- A good practice committed to cultural heritage: Lives and Places with History, a project carried on by the Gerês-Xurés Transboundary BR.

- A good practice committed to both environmental and cultural heritage: Building Community, a project carried on by the Gran Canaria BR.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions, Strategic Recommendations for BRs

- -

- Strategic Planning and Institutional Commitment: A significant proportion of BRs still lack formal strategic frameworks aligned with the SDGs. It is essential that all reserves develop and implement a dedicated Agenda 2030 or equivalent strategic plan. This should be accompanied by the allocation of specific budgets and the establishment of robust monitoring, evaluation, and assessment mechanisms to ensure accountability and progress tracking.

- -

- Capacity Building and Resource Allocation: The effectiveness of BRs in promoting sustainable development is constrained by limited human and financial resources. Addressing these gaps through increased staffing, targeted funding, and professional development is crucial for enhancing management efficiency and long-term impact.

- -

- Knowledge, Education, and Research Integration: There is a clear need to expand educational offerings and training programs focused on the SDGs, sustainable development, and related global challenges such as climate change and economic transformation. Furthermore, research activities within BRs should more systematically incorporate sustainability themes to reinforce their role as knowledge hubs and innovation platforms.

- -

- Visibility, Engagement, and Governance: The commitment of BRs to the SDGs must be made more visible, both within their territories and across the broader network. This includes fostering greater engagement from political leaders, reserve managers, local communities, and civil society actors in sustainability initiatives.

- -

- Collaboration and Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships: Strengthening collaboration—both among BRs and with external institutions, community organizations, and private sector actors—is essential. Public–private partnerships and joint initiatives can amplify impact, facilitate knowledge exchange, and mobilize additional resources for sustainable development.

8. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AANP | Autonomous Agency for National Parks; |

| BRs | Biosphere Reserves; |

| MaB | Man and the Biosphere Programme; |

| NGOs | Non-Governmental Organizations; |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals; |

| SNBR | Spanish Network of Biosphere Reserves; |

| UN | United Nations; |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. |

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- 1.1. Name of the BR.

- 1.2. Type of BR.

- 1.3. Full name of the survey participant.

- 1.5. Contact information.

- 1.6. In which autonomous community or communities, country or countries, is the BR located?

- 2.1. Predominant dimensions: What is the main way sustainable development is understood?

- 2.2. Does the BR address the three dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social, and environmental) in an integrated manner?

- 2.3. Indicate your level of knowledge regarding each of the following aspects (Likert scale 4 points from null to advanced): the 2030 Agenda, SDGs, Education for Sustainable Development, Global Citizenship Education, Climate Change Education, Sustainable Development, and Economic Development.

- 2.4. Does your BR explicitly demonstrate its commitment to the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda? If the answer is affirmative, please specify how it does so, and inform all applicable options.

- 3.1. What specific unit is responsible for sustainability activities in the BR?

- 3.2. Who is most involved in sustainable development within the BR?

- 3.3. In which areas this BR has been involved in sustainable development?

- 3.4. Many BRs face various challenges when implementing actions toward sustainable development: Which of the following difficulties or challenges have hindered the implementation of sustainable development (and of plans and strategies, when they exist) in this BR?

- 3.5. New opportunities arise and promote the development and implementation of actions toward sustainable development. Which opportunities support the implementation of sustainable development actions in this BR?

- 3.6. What do you believe is most needed to promote sustainable development in BRs?

- 3.7. To what extent has the adoption of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs in 2015 increased interest in sustainable development in this BR?

- 3.8. Has COVID-19 influenced (or is it still influencing) the sustainable development strategy or related activities?

- 3.9. Has the economic crisis influenced, or is it currently influencing, the sustainable development strategy or related activities?

- 4.1. Indicate which SDGs in this BR is involved in (and at what level, if applicable) Mark on the scale: 0—not addressed, not even implicitly; 1—addressed implicitly in a tangential way; 2—implicitly addressed as part of the Reserve’s operations; 3—explicitly addressed as a secondary objective; 4—explicitly addressed as a primary objective).

- 4.2. Highlight up to 3 examples of how this BR works on the mentioned topics (include links to the projects if possible).

- 5.1. Is there a strategic plan for sustainable development in this BR?

- 5.2. If the answer to the previous question is affirmative, specify the timeline of the plan and include a link to the available information if possible.

- 5.3. Is there a 2030 Agenda or a Strategic Plan to achieve the SDGs in this BR?

- 5.4. If the answer to the previous question is affirmative, specify the timeline and include a link to the available information if possible.

- 5.5. At what level is sustainable development promoted in this BR?

- 5.6. Specify examples of policies and practices adopted in relation to sustainable development, the 2030 Agenda, and/or the SDGs.

- 5.7. Are there any instruments or mechanisms in this BR for assessing, monitoring, and evaluating sustainable development actions?

- 5.8. If the answer to the previous question is affirmative, specify the instruments used.

- 5.9. Is there a specific budget for sustainability and the implementation of the 2030 Agenda?

- 5.10. Has the budget changed in the last 5 years?

- 5.11. Are there specific plans, policies, or concrete actions aimed at increasing the alignment of the Biosphere Reserve with the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda in the future?

- 5.12. If this BR carries out good practices or has had any successful experiences related to the 2030 Agenda or the SDGs in general, or with any specific SDG, would you like to share them with other BRs?

- 6.1. Does this BR offer training and courses specifically focused on the SDGs, the 2030 Agenda, and sustainable development? If the answer is affirmative, could you please specify them?

- 6.2. Have the SDGs, the 2030 Agenda, and sustainable development become cross-cutting themes in education, research, and development within this BR? If the answer is affirmative, could you please specify how?

- 6.3. Does the research conducted in the BR include research focused on sustainable development and the SDGs? If the answer is affirmative, could you please specify the research areas?

- 6.4. The economic development of the BR is related to … (indicate at least 3 options you consider important).

- 7.1. Does this BR collaborate with other BRs or institutions on issues related to the SDGs and sustainable development? If the answer is affirmative, could you please specify at what level(s)?

- 7.2. In which BR networks focused on the SDGs and sustainable development does this BR participate?

- 7.3. Does this BR collaborate with public entities (e.g., government, public institutions and organizations, etc.) on sustainability, SDG, or 2030 Agenda projects? If the answer is affirmative, could you please specify which ones?

- 7.4. What types of political instruments influence this BR when committing to the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs?

- 7.5. Does this BR collaborate with private actors and entities (companies or organizations) on sustainability projects related to the SDGs or the 2030 Agenda? If the answer is affirmative, could you specify the entities?

- 7.6. If this BR could implement any new action to promote sustainability, the SDGs, or the 2030 Agenda, what would it be?

- 7.7. Could you indicate the contact points/focal points of the people responsible for promoting sustainable development programs and practices, SDGs, and the 2030 Agenda in this BR?

- 7.8. Would this BR like to learn more about how to integrate the SDGs, the 2030 Agenda, or sustainable development? If yes, please indicate in which areas (e.g., training, publications, seminars, etc.).

Appendix B

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sierra de Grazalema * | 36.75° N, 5.37° W | Mountain, Mediterranean | 1977 | 51,695 | 15,000 | 20 |

| Doñana * | 37.00° N, 6.45° W | Wetland, Coastal | 1980 | 268,293 | 40,000 | 50 |

| Sierra Nevada * | 37.09° N, 3.38° W | High Mountain | 1986 | 171,646 | 60,000 | 45 |

| Sierras de Cazorla, Segura, Las Viñas * | 38.10° N, 2.90° W | Mountain, Forest | 1983 | 209,920 | 25,000 | 30 |

| Marismas del Odiel * | 37.25° N, 6.95° W | Wetland, Estuary | 1983 | 25,304 | 10,000 | 10 |

| Sierra de las Nieves * | 36.65° N, 4.95° W | Mountain, Mediterranean | 1995 | 93,930 | 20,000 | 18 |

| Cabo de Gata-Níjar * | 36.83° N, 2.45° W | Coastal, Desert | 1997 | 50,000 | 30,000 | 20 |

| Dehesas de Sierra Morena * | 38.00° N, 5.50° W | Forest, Pastoral | 2002 | 424,400 | 60,000 | 25 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordesa-Viñamala * | 42.65° N, 0.03° E | High Mountain, Forest | 1977 | 117,364 | 5000 | 15 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somiedo * | 43.05° N, 6.25° W | Mountain, Forest | 2000 | 29,121 | 1500 | 8 |

| Muniellos | 43.05° N, 6.70° W | Forest, Protected Core | 2000 | 55,657 | 500 | 5 |

| Redes | 43.20° N, 5.50° W | Mountain, Forest | 2001 | 37,804 | 2000 | 10 |

| Las Ubiñas-La Mesa * | 43.10° N, 6.00° W | Mountain, Forest | 2012 | 55,800 | 3000 | 12 |

| Ponga | 43.25° N, 5.20° W | Mountain, Forest | 2018 | 20,500 | 600 | 6 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mundial de La Palma * | 28.68° N, 17.77° W | Island, Volcanic | 1983 | 80,702 | 85,000 | 30 |

| Lanzarote * | 29.03° N, 13.63° W | Island, Volcanic | 1993 | 122,610 | 150,000 | 35 |

| El Hierro * | 27.74° N, 18.02° W | Island, Volcanic | 2000 | 27,000 | 11,000 | 15 |

| Gran Canaria * | 28.00° N, 15.60° W | Island, Volcanic | 2005 | 156,000 | 850,000 | 40 |

| La Gomera * | 28.10° N, 17.20° W | Island, Forest | 2012 | 38,000 | 22,000 | 20 |

| Fuerteventura * | 28.50° N, 14.00° W | Island, Desert | 2009 | 165,000 | 120,000 | 25 |

| Macizo de Anaga * | 28.55° N, 16.20° W | Island, Forest | 2015 | 14,419 | 10,000 | 10 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mancha Húmeda | 39.10° N, 3.40° W | Wetland, Agricultural | 1980 | 418,087 | 50,000 | 25 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babia | 42.98° N, 6.08° W | Mountain, Forest | 2004 | 38,018 | 1600 | 10 |

| Alto Bernesga * | 42.90° N, 5.60° W | Mountain, Forest | 2005 | 33,442 | 1000 | 5 |

| Los Argüellos | 43.00° N, 5.50° W | Mountain, Forest | 2005 | 33,260 | 1500 | 6 |

| Omaña y Luna | 42.85° N, 6.00° W | Mountain, Forest | 2005 | 81,162 | 3000 | 10 |

| Valle de Laciana * | 42.95° N, 6.30° W | Mountain, Forest | 2003 | 21,700 | 2000 | 6 |

| Los Ancares Leoneses | 42.80° N, 6.90° W | Mountain, Forest | 2006 | 56,786 | 4000 | 10 |

| Sierras de Béjar y Francia * | 40.40° N, 5.90° W | Mountain, Forest | 2006 | 199,140 | 10,000 | 15 |

| Real Sitio de San Ildefonso-El Espinar | 40.90° N, 4.00° W | Forest, Cultural Landscape | 2013 | 35,414 | 5000 | 8 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montseny | 41.77° N, 2.40° E | Mountain, Forest | 1978 | 50,167 | 30,000 | 25 |

| Terres de l’Ebre | 40.80° N, 0.60° E | River Delta, Coastal | 2013 | 367,729 | 190,000 | 30 |

| Val d’Aran * | 42.70° N, 0.90° E | Pyrenean, Cultural | 2024 | 63,168 | 10,000 | 12 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terras do Miño * | 43.00° N, 7.00° W | River Basin, Forest | 2002 | 363,669 | 150,000 | 20 |

| Área de Allariz * | 42.20° N, 7.80° W | Forest, Agricultural | 2005 | 21,482 | 10,000 | 8 |

| Os Ancares Lucenses * | 42.90° N, 7.00° W | Mountain, Forest | 2006 | 53,664 | 5000 | 10 |

| Mariñas Coruñesas e Terras do Mandeo * | 43.30° N, 8.30° W | Coastal, Agricultural | 2013 | 113,970 | 100,000 | 20 |

| Ribeira Sacra e Serras do Oribio e Courel * | 42.50° N, 7.40° W | River Basin, Forest | 2021 | 306,535 | 50,000 | 18 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monfragüe * | 39.85° N, 6.00° W | Mountain, Forest | 2003 | 116,160 | 10,000 | 20 |

| La Siberia * | 39.30° N, 5.00° W | River Basin, Plains | 2019 | 155,717 | 15,000 | 12 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alto Turia * | 39.80° N, 1.00° W | River Basin, Forest | 2019 | 67,080 | 4300 | 10 |

| Valle del Cabriel | 39.60° N, 1.30° W | River Basin, Forest | 2019 | 421,766 | 20,000 | 15 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menorca * | 39.94° N, 4.14° E | Island, Coastal | 1993 | 71,186 | 95,000 | 20 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valles del Jubera, Leza, Cidacos y Alhama * | 42.30° N, 2.30° W | River Basin, Forest | 2003 | 119,669 | 10,000 | 10 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuencas Altas de los Ríos Manzanares, Lozoya y Guadarrama | 40.75° N, 3.90° W | Mountain, Forest | 1992/2019 | 105,654 | 100,000 | 35 |

| Sierra del Rincón * | 41.00° N, 3.50° W | Mountain, Forest | 2005 | 16,092 | 2000 | 10 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bárdenas Reales * | 42.20° N, 1.30° W | Semi-desert, Plateau | 2000 | 39,273 | 2000 | 8 |

| Name | Coordinates | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urdaibai | 43.40° N, 2.67° W | Estuary, Wetland | 1984 | 22,041 | 45,000 | 15 |

| Name | Coordinates | Regions Involved | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picos de Europa | 43.18° N, 4.83° W | Shared with Asturias, and Castilla y León | High Mountain | 2003 | 64,315 | 20,000 | 40 |

| Río Eo, Oscos y Terras de Burón * | 43.45° N, 7.00° W | Shared with Galicia, and Asturias | River Basin, Forest | 2007 | 158,883 | 20,000 | 15 |

| Valle del Cabriel * | 39.60° N, 1.30° W | Shared with Castilla-La Mancha, and Comunidad Valenciana | River Basin, Forest | 2019 | 421,766 | 20,000 | 15 |

| Name | Coordinates | Countries and Regions involved | Typology | Year | Area (ha) | Population (Approx.) | Staff (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercontinental del Mediterráneo * | 35.00° N, 5.00° W | Transboundary Spain (Andalucía)/Morocco | Mediterranean, Coastal | 2006 | 894,134 | 100,000 | 40 |

| Gerês-Xurés * | 42.00° N, 8.10° W | Transboundary Spain (Galicia)/Portugal | Mountain, Forest | 2009 | 267,958 | 30,000 | 20 |

| Meseta Ibérica * | 41.50° N, 6.00° W | Transboundary Spain (Castilla y León)/Portugal | Plateau, River Basin | 2015 | 1,132,607 | 300,000 | 50 |

| Tajo-Tejo Internacional * | 39.60° N, 7.50° W | Transboundary Spain (Extremadura)/Portugal | River Basin, Forest | 2016 | 428,176 | 30,000 | 20 |

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Sever, S.D.; Tok, E.; Sellami, A.L. Sustainable Development Goals in a Transforming World: Understanding the Dynamics of Localization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. World Network of Biosphere Reserves. 2023. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/wnbr (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- UNESCO. n.d. Man and the Biosphere Programme. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/mab (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Herrero, C. Biosphere Reserves: Learning spaces for sustainability. Int. J. UNESCO Biosph. Reserves 2017, 1, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbrand, E.; Michler, T. Why do UNESCO biosphere reserves get less recognition than national parks? A landscape research perspective on protected area narratives in Germany. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaindia, M.; Ballesteros, F.; Alonso, G.; Monge-Ganuzas, M.; Pena, L. Participatory process to prioritize actions for a sustainable management in a biosphere reserve. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 33, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cuong, C.; Dart, P.; Hockings, M. Biosphere reserves: Attributes for success. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguia-Cruz, M.; Cerda, C.; Ortiz-Cubillos, N.; Mansilla-Quiñones, P.; Moreira-Muñoz, A. Enhancing participatory governance in biosphere reserves through co-creation of transdisciplinary and intergenerational knowledge. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1266440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Lima Action Plan for UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme and Its World Network of Biosphere Reserves (2016–2025); Document SC-16/CONF.228/11; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Organismo Autónomo Parques Nacionales. Action Plan for the Spanish Network of Biosphere Reserves (2017–2025); Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico: Madrid, Spain, 2017; Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Red Española de Reservas de la Biosfera. Informe de Seguimiento de la Agenda 2030 en las Reservas de la Biosfera Españolas; Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: http://rerb.oapn.es/ (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Weber, M. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, T.; Söderbaum, F. The origins of legitimation strategies in international organizations: Agents, audiences and environments. Int. Aff. 2023, 99, 899–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaara, E.; Aranda, A.M.; Etchanchu, H. Discursive legitimation: An integrative theoretical framework and agenda for future research. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 2343–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, B.; Toubiana, M.; Coslor, E. From catch-and-harvest to catch-and-release: Trout Unlimited and repair-focused deinstitutionalization. Organ. Stud. 2024, 45, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imerman, D. Contested Legitimacy and Institutional Change: Unpacking the Dynamics of Institutional Legitimacy. Int. Stud. Rev. 2018, 20, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.J. Overcoming Barriers to Implementing Sustainable Development Goals: Human Ecology Matters. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2020, 26, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Aronson, J.; Whaley, O.; Lamb, D. The relationship between ecological restoration and the ecosystem services concept. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabard, C.H.; Gohr, C.; Weiss, F.; von Wehrden, H.; Neumann, F.; Hordasevych, S.; Arieta, B.; Hammerich, J.; Meier, C.; Jargow, J.; et al. Biosphere Reserves as model regions for transdisciplinarity? A literature review. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 2065–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbrich, S. On Legitimacy in Global Governance: Concept, Criteria, and Application; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, A.D.; Reed, M.G.; Mâren, I.E.; Price, M.F.; Moreira-Muñoz, A.; Coetzer, K. Recognize 727 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves for biodiversity COP15. Nature 2021, 598, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolmer, W. Transboundary Conservation: The Politics of Ecological Integrity in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. J. South. Afr. Stud. 2003, 29, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; de La Vega-Leinert, A.C.; Schultz, L. The role of community participation in the effectiveness of UNESCO Biosphere Reserve management: Evidence and reflections from two parallel global surveys. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karez, C.S.; Hernández Faccio, J.M.; Schüttler, E.; Rozzi, R.; Garcia, M.; Meza, Á.Y.; Clüsener-Godt, M. Learning experiences about intangible heritage conservation for sustainability in biosphere reserves. Mater. Cult. Rev. 2015, 82, 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rollo, M.F. Interconnected Nature and People: Biosphere Reserves and the Power of Memory and Oral Histories as Biocultural Heritage for a Sustainable Future. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhsain, W.; Boujrouf, S. Innovation of UNESCO-MAB: An opportunity for the territorial and sustainable development of the Arganeraie Biosphere Reserve. J. Adv. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 8, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRUE. Surveys, Spanish Universities, and the 2030 Agenda. 2019. Available online: https://www.crue.org (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Mohd Rokeman, N.R. Likert Measurement Scale in Education and Social Sciences: Explored and Explained. Educ. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technical Information | |

|---|---|

| Geographical Scope | Spain |

| Target Population | SNBR (55 BRs) |

| Data Collection Method | Questionnaire |

| Time Frame | July 2024–March 2025 |

| Participants | Reserve managers |

| Sample Size | 40 valid questionnaires |

| Participation Rate | 72.73% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maldonado-Briegas, J.J.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Corrales-Vázquez, J.M. Biosphere Reserves in Spain: A Holistic Commitment to Environmental and Cultural Heritage Within the 2030 Agenda. Heritage 2025, 8, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080309

Maldonado-Briegas JJ, Sánchez-Hernández MI, Corrales-Vázquez JM. Biosphere Reserves in Spain: A Holistic Commitment to Environmental and Cultural Heritage Within the 2030 Agenda. Heritage. 2025; 8(8):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080309

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaldonado-Briegas, Juan José, María Isabel Sánchez-Hernández, and José María Corrales-Vázquez. 2025. "Biosphere Reserves in Spain: A Holistic Commitment to Environmental and Cultural Heritage Within the 2030 Agenda" Heritage 8, no. 8: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080309

APA StyleMaldonado-Briegas, J. J., Sánchez-Hernández, M. I., & Corrales-Vázquez, J. M. (2025). Biosphere Reserves in Spain: A Holistic Commitment to Environmental and Cultural Heritage Within the 2030 Agenda. Heritage, 8(8), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080309