Cultural Play at a Distance: Post-COVID Serious Heritage Games

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Digital Heritage, Virtual Heritage

We’re in an intermediate place here,” says head librarian Elisabeth Rozelot. “It’s vocation is to teach people how to be citizens and to develop their critical faculties, with the ability to choose their leisure activities, meet others and take part in social life.”

1.2. GLAM Challenges and Opportunities

1.3. Mirrored In-World Avatars

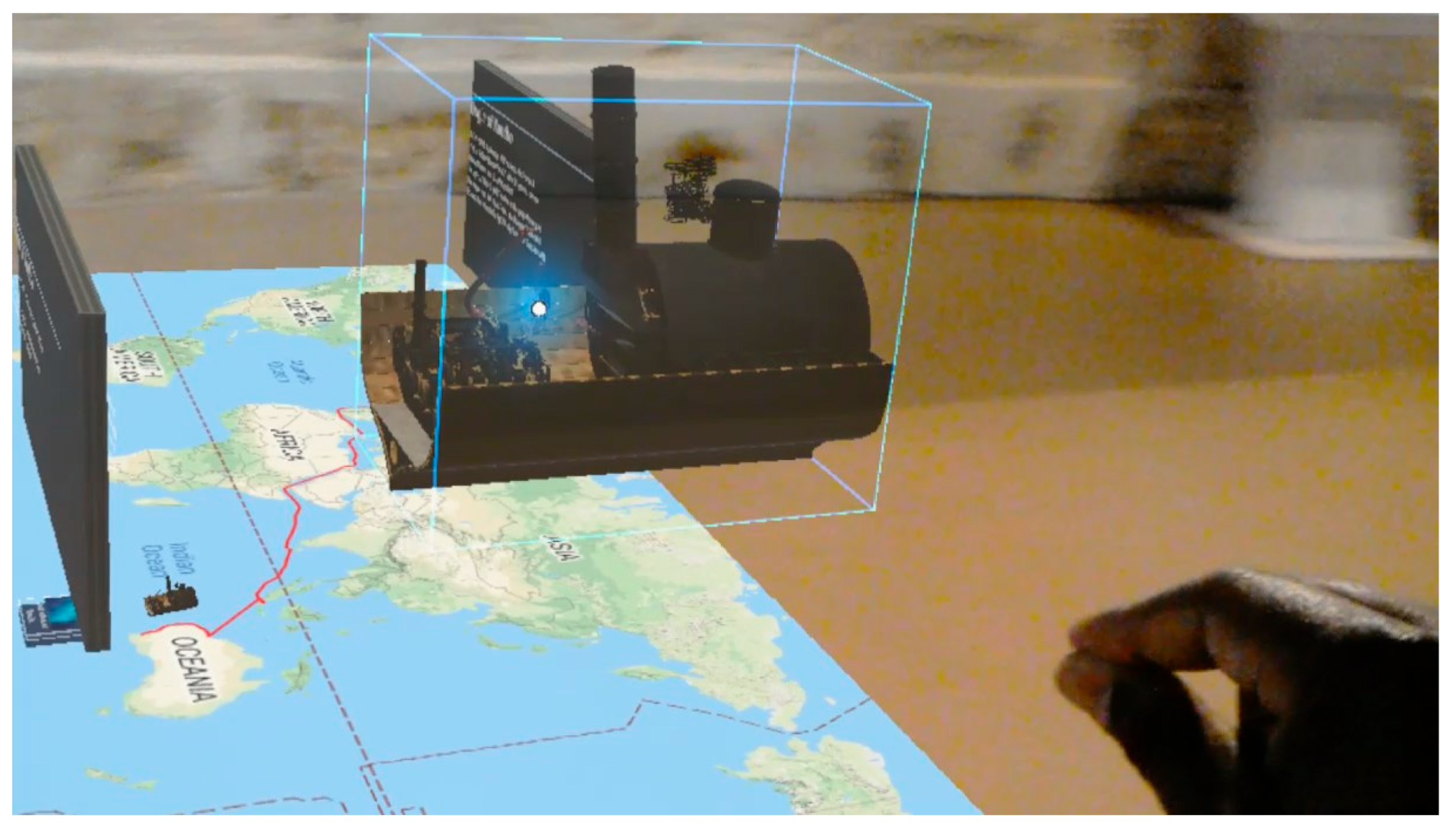

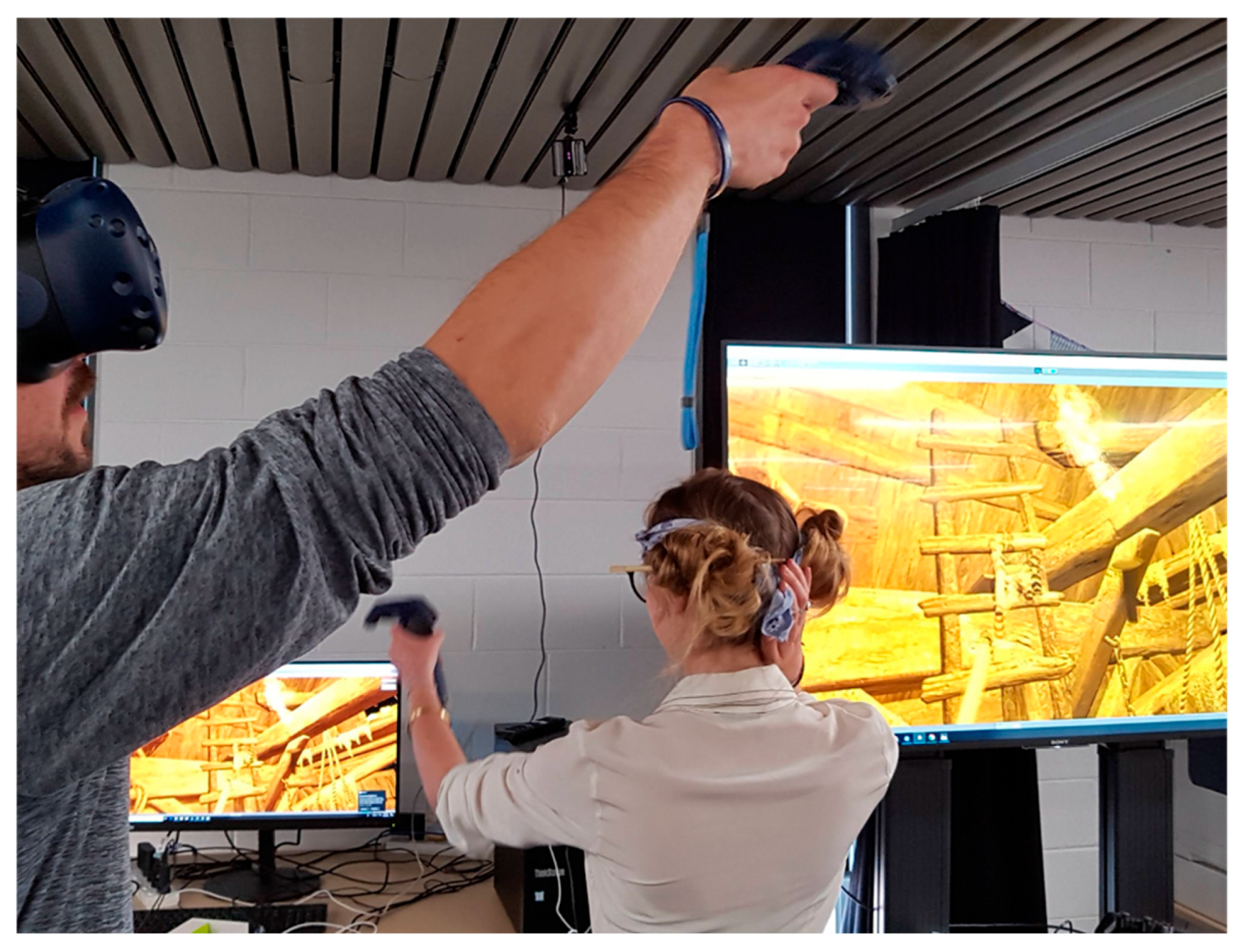

1.4. Mixed Reality at a Distance

1.5. Community-Based Support

2. Methodological Approach

3. Game Case Study

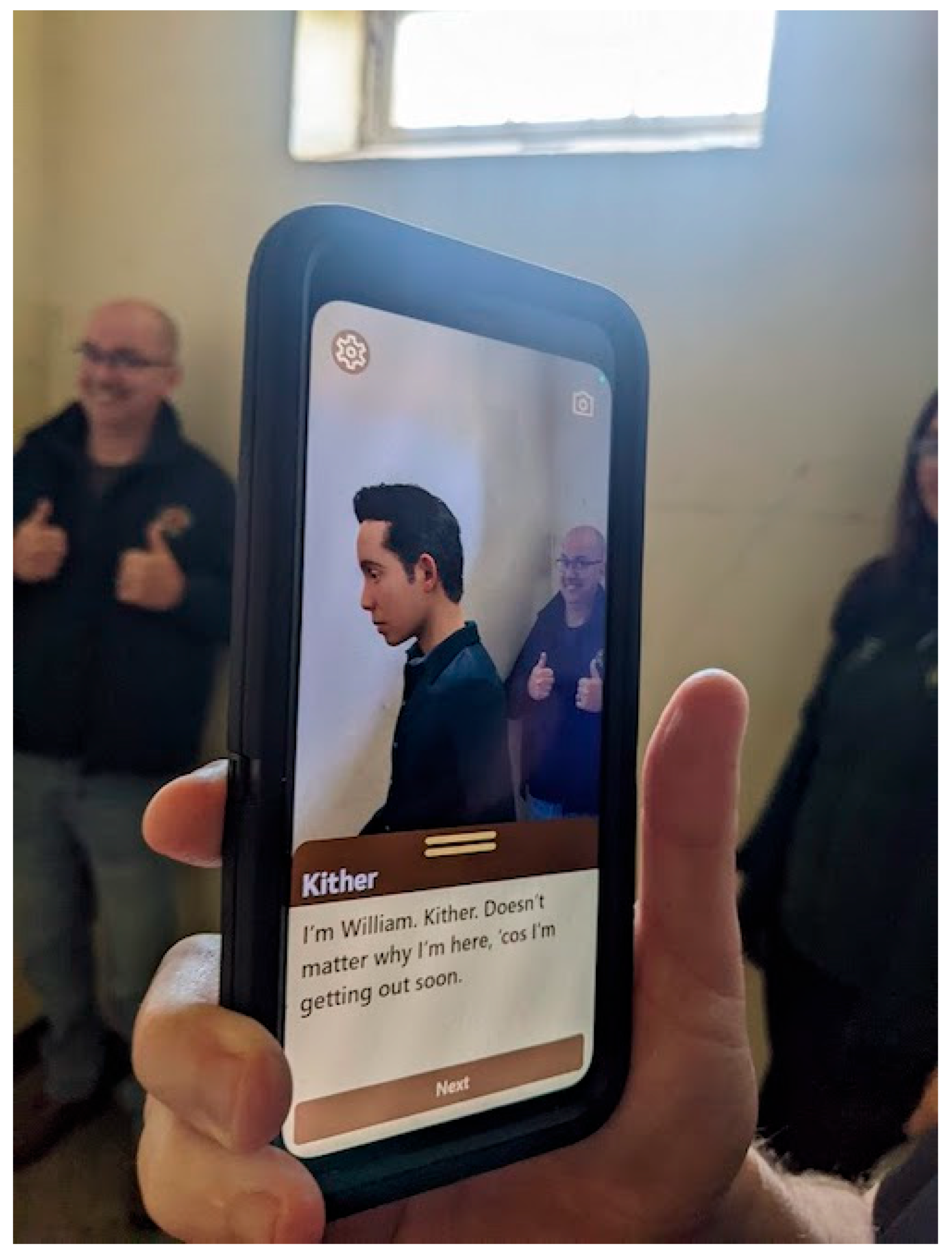

3.1. ‘Escape from the Gaol’: A Phone-Based Game

3.2. An Open-Ended Game Framework

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Supporting Museums: UNESCO Report Points to Options for the Future. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/supporting-museums-unesco-report-points-options-future (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- UN World Tourism Organization. Tourist Arrivals Down 87% in January 2021 as UNWTO Calls for Stronger Coordination to Restart Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/tourist-arrivals-down-87-in-january-2021-as-unwto-calls-for-stronger-coordination-to-restart-tourism (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Alatrash, S.; Arnab, S.; Antlej, K. The Potential Of Implementing Interactive Storytelling Experience For Museums. In Proceedings of the Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection: 8th International Conference, EuroMed 2020, Virtual Event, 2–5 November 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 713–721. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Games as Crowdsourcing Tools for Digital Heritage in the Gallery, Library, Archive and Museum (GLAM) Field A Model Design for Cultural Crowdsourcing Games Through the Lens of Interactive Narrative; Trinity College: Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G.-S.; Ab. Aziz, K.; Ahmad, Z. Ensuring resilience using augmented reality: How museums can respond during and post COVID-19? In Augmented Reality in Tourism, Museums and Heritage: A New Technology to Inform and Entertain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Brigitte, V.; Muscat, A. Sharing Indigenous Cultural Heritage Online: An Overview of GLAM Policies. Creative Commons Organization Copyright. 2020. Available online: https://creativecommons.org/2020/08/08/sharing-indigenous-cultural-heritage-online-an-overview-of-glam-policies/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Ross, B. Is This the End of Touchscreens in Museums? The Use of Touchless Gesture-Based Controls. Science Museum Group Digital Lab, 2020. Available online: https://lab.sciencemuseum.org.uk/is-this-the-end-of-touchscreens-in-museums-the-use-of-touchless-gesture-based-controls-ee3f3c3f37ce (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J.P. Museums and Digital Culture: From Reality to Digitality in the Age of COVID-19. Heritage 2022, 5, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaroudi, M.; Echavarria, K.R.; Perry, L. Heritage in Lockdown: Digital Provision of Memory Institutions in the UK and US of America During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Escape COVID-19: Using a Serious Game to Promote COVID-19 Infection Prevention and Control Practice Among Hospital Staff Prior to the Availability of Vaccines; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 2025.

- Raab, M.H.; Döbler, N.A.; Carbon, C.-C. A Game of Covid: Strategic Thoughts About a Ludified Pandemic. Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 607309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Concept of Digital Heritage. UNESCO. 19 October 2021. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/information-preservation/digital-heritage/concept-digital-heritage (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Champion, E. History and Cultural Heritage in Virtual Environments. In The Oxford Handbook of Virtuality; Grimshaw, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.; Waterton, E. Heritage, Communities and Archaeology; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deutschmann, M.; Outakoski, H.; Panichi, L.; Schneider, C. Virtual Learning, Real Heritage Benefits and Challenges of Virtual Worlds for the Learning of Indigenous Minority Languages. In Proceedings of the International ICT for Language Learning 2010, Florence, Italy, 11–12 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- So, H.-J.; Seo, M. A systematic literature review of game-based learning and gamification research in Asia. In Routledge International Handbook of Schools and Schooling in Asia; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vocaturo, E.; Zumpano, E.; Caroprese, L.; Pagliuso, S.M.; Lappano, D. Educational Games for Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the VIPERC and 15th Italian Research Conference on Digital Libraries, Pisa, Italy, 30 January 2019; pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Leader-Elliott, L. Community heritage interpretation games: A case study from Angaston, South Australia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2003, 11, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.N.; Rafi, A.; Woods, P. Experience Design Framework for Reconstructed Virtual Architectural Heritage. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2018, 24, 1352–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. How Can Gaming Save the Museum Industry During/After the COVID-19? Available online: https://weiss-ag.com/how-can-gaming-save-the-museum-industry-during-after-the-covid-19/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Potet, F. France’s Libraries Discovering a New Lease of Life Beyond Just Books. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/02/france-libraries-social-workshops-meeting-hub (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Griffin, D.; Paroissien, L. Museums in Australia: From a New Era to a New Century. Available online: https://nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/DGriffin_LParoissien_2011a.html (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- American Library Association. The Rise of Third Place and Open Access Amidst the Pandemic. Available online: https://www.ala.org/advocacy/diversity/odlos-blog/rise-third-place (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Bongiorno, F.; Black, J.; Arrow, M. Australia’s Cultural Institutions Are Especially Vulnerable to Efficiency Dividends: Looking Back at 35 Years of Cuts. Arts+Culture. 2023. Available online: https://theconversation.com/australias-cultural-institutions-are-especially-vulnerable-to-efficiency-dividends-looking-back-at-35-years-of-cuts-202727 (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Johnson, K.R.; Owens, I.F.; Group, G.C. A global approach for natural history museum collections. Science 2023, 379, 1192–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Champion, E.; Summers, L.; Lugmayr, A.; Clarke, M. The Role of Responsive Library Makerspaces in Supporting Informal Learning in the Digital Humanities. In Digital Humanities, Libraries, and Partnerships: A Critical Examination of Labor, Networks, and Community; Kear, R., Joranson, K., Eds.; Chandos Press, Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Champion, E.M.; Qiang, L.; Lacet, D.; Dekker, A. 3D in-world Telepresence With Camera-Tracked Gestural Interaction. In Eurographics Workshop on Graphics and Cultural Heritage; Eurographics Association: Genoa Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Bekele, M.K.; Champion, E.; McMeekin, D.A.; Rahaman, H. The Influence of Collaborative and Multi-Modal Mixed Reality: Cultural Learning in Virtual Heritage. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Bokijonov, S.; Choi, Y. Review of Microsoft HoloLens Applications Over the Past Five Years. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heather, B. Dark Tourism. Law Text Cult. 2009, 13, 260–272. [Google Scholar]

- University of South Australia. Adelaide Gaol Comes Alive Thanks to New Augmented Reality App. 2022. Available online: https://www.unisa.edu.au/media-centre/Releases/2022/adelaide-gaol-comes-alive-thanks-to-new-augmented-reality-app (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Museums & Galleries of NSW. 2018 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census Museums & Galleries of NSW-Data and Insights-Culture Counts™; Museums & Galleries of NSW: Sydney, Australia, 2019; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsabasis, P. Evaluation in virtual heritage. In Virtual Heritage: A Guide; Champion, E., Ed.; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, T.; Hu, C. Application Model of Museum Cultural Heritage Educational Game Based on Embodied Cognition and Immerse Experience. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhi, A.; Ahmed, H.O.; Alfaqheri, T.; Bouras, A.; Sadka, A.H.; Foufou, S. An Integrated Framework For The Interaction And 3D Visualization Of Cultural Heritage. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 46653–46681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, X.; Watanabe, I.; Ochiai, Y. A systematic review of digital transformation technologies in museum exhibition. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 161, 108407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerrouki, N.; Harrou, F.; Houacine, A.; Bouarroudj, R.; Cherifi, M.Y.; Zouina, A.-D.A.; Sun, Y. Deep learning for hand gesture recognition in virtual museum using wearable vision sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 8857–8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, R.L.; Hibbard, P.B. Current perceptions of virtual reality technology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. SMH. 20 January 2023. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/pm-says-arts-institutions-are-starved-of-funds-but-how-much-longer-can-they-hold-out-20230119-p5cdrb.html (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Banfi, F.; Oreni, D. Unlocking the interactive potential of digital models with game engines and visual programming for inclusive VR and web-based museums. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2025, 16, 44–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massidda, M.; Travaglini, L.; Pescarin, S. Designing Hybrid and XR narrative applications: A Framework to describe Authoring Tools in Cultural Domain. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2025, e00424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesário, V.; Freitas, J.; Campos, P. Empowering cultural heritage professionals: Designing interactive exhibitions with authoring tools. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2025, 40, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Emery, S.; Champion, E.M. Cultural Play at a Distance: Post-COVID Serious Heritage Games. Heritage 2025, 8, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070262

Emery S, Champion EM. Cultural Play at a Distance: Post-COVID Serious Heritage Games. Heritage. 2025; 8(7):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070262

Chicago/Turabian StyleEmery, Susannah, and Erik Malcolm Champion. 2025. "Cultural Play at a Distance: Post-COVID Serious Heritage Games" Heritage 8, no. 7: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070262

APA StyleEmery, S., & Champion, E. M. (2025). Cultural Play at a Distance: Post-COVID Serious Heritage Games. Heritage, 8(7), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070262