Large Terrace Structure Unearthed in the Heart of the City Zone of Īśānapura: Could It Be the ‘Great Hall’ Described in the Book of Sui?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Distribution of Archaeological Features in the Moated City Zone

3. Textual Materials and Methods

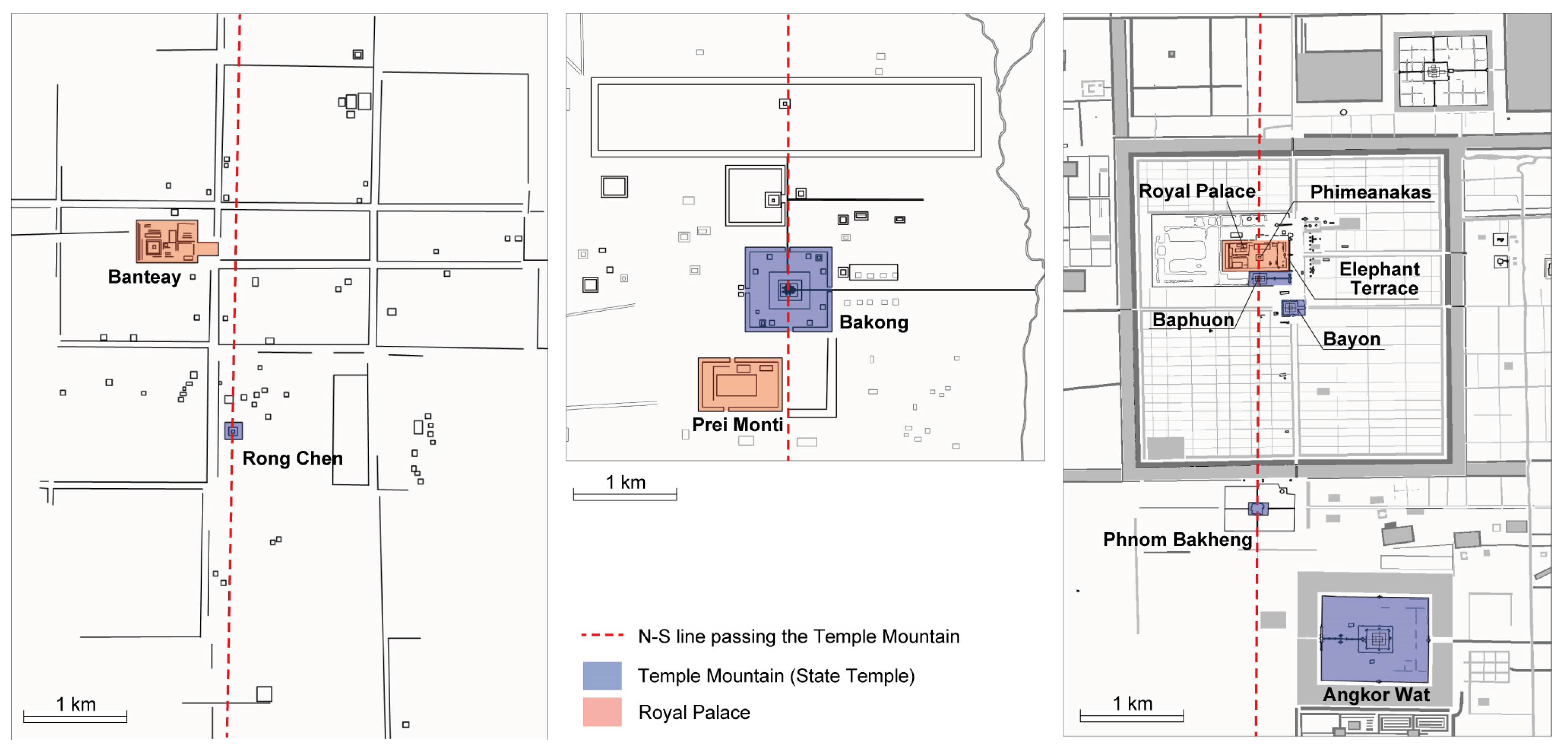

3.1. Īśānapura as Described in the Book of Sui

3.2. Methods and Scope of Archaeological Excavation Survey

4. Results

4.1. Structures Confirmed in the Excavation Surveys

4.1.1. Central Terrace

4.1.2. Southern Attached Chamber

4.1.3. Structures on the Central Terrace

Upper Low Terrace

Upper Brick Square Bases

Collapsed Brick-Built Features

Upper Structures at the North End of the Central Terrace

4.2. Unearthed Artifacts That Contribute to the Dating of Structures

4.2.1. Stone Items

4.2.2. Chinese and Vietnamese Potteries

4.3. Results of a Radiocarbon Dating of Sampled Charcoal

5. Discussion

5.1. Architectural Reconstruction and Dating of the Construction and Modifications of Large Terrace M.90

5.1.1. Reconstruction of the Excavated Structure

5.1.2. Chronological Consideration of the Construction, Modification, and Abandonment of the Excavated Structure

5.2. Exploring Khmer Urban History Through the Great Hall of Īśānapura

5.2.1. Characteristics of Īśānapura in Comparison with Urban Layouts of Later Khmer Cities

5.2.2. The Spatial Position of the Great Hall Within the Royal Palace Complex

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Excavated Artifacts from M.90

| Area A | Area B | Area C | Area D | Area E | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earthenware | 682 | 821 | 954 | 4048 | 155 | 6660 |

| Khmer or imported ceramics | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Stone or stone product | 0 | 3 | 19 | 10 | 0 | 32 |

| Metal object | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Clay clump | 0 | 0 | 3 | 18 | 0 | 21 |

| Total | 682 | 828 | 985 | 4077 | 155 | 6727 |

| Layer | Area A (Including 63U-V) | Area B (Including 55R-S) |

|---|---|---|

| I (surface soil) | 0 | 0 |

| II (sedimentary soil) | 0 | 0 |

| III (sedimentary soil on the additional brick structures) | 421 | 42 |

| IV (filled soil under additional square base structures) | 28 | 291 |

| V (filled soil in the central terrace) | 233 | 492 |

| Unknown | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 682 | 829 |

| Area A | Area B | Area C | Area D | Area E | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jar | 5 | 17 | 33 | 44 | 2 | 101 |

| Large jar | 22 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 44 |

| Spouted vessels (kundis) | 12 | 3 | 7 | 22 | 4 | 48 |

| Bowls | 20 | 94 | 72 | 93 | 7 | 286 |

| Tall jars | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Lid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Small bowl with many holes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Stove | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 8 |

| Tile | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| Small containers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Disc-shaped clay items | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 60 | 129 | 129 | 178 | 16 | 512 |

References

- Dagens, B. Les Khmers (Guide Belles Lettres des Civilisations 10); Les Belles Lettres: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, C. Études d’épigraphie cambodgienne. X—Autour de quelques toponymes de l’inscription de Pràsàt Trapẵṅ Run, K. 598: La capitale angkorienne de Yaśovarman Ier à Sūryavarman Ier. Bull. l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 1978, 65, 281–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaucher, J. Considérations nouvelles sur la fondation d’Angkor Thom, in Angkor. In Naissance d’un Mythe: Louis Delaporte et le Cambodge; Pierre, B., Thierry, Z., Eds.; Gallimard: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Groslier, B.-P. Fouilles du palais d’Angkor Thom. Aséanie Sci. Hum. Asie Du Sud-Est 2014, 33, 175–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, H. Shinrō Fudoki: Ankōruki No Kanbojia (Customs of Cambodia: Cambodia in Angkor Period); Toyo Bunko: Tokyo, Japan, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Groslier, G. Recherches Sur les Cambodgiens s’après les Textes et les Monuments Depuis les Premiers Siècles de Notre ère; A. Challamel: Paris, France, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, T.; Polkinghorne, M. A Review of Sources for Visualising the Royal Palace of Angkor, Cambodia, in the 13th Century. In Virtual Palaces, Part II. Lost Palaces and Their Afterlife. Virtual Reconstruction Between Science and Media; Hoppe, S., Breitling, S., Eds.; Hoppe and Breitling: München, Germany, 2016; pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Dumarçay, J. The Palaces of South-East Asia: Architecture and Customs; Oxford University Press: Singapore, 1991; pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cœdès, G. Inscriptions du Cambodge; Collection des Textes et Documents sur l’Indochine, 3; Éditions de Boccard: Paris, France, 1952; Volume 4, pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier, H. L’art Khmèr Primitif; Publ. de L’EFEO: Paris, France, 1927; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Goloubew, V. Chronique. Cambodia. Bull. l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 1937, 37, 655. [Google Scholar]

- Goloubew, V. Chronique. Cambodia. Bull. l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 1938, 38, 442. [Google Scholar]

- Leclère, M.A. Fouilles de Kompong Soay (Cambodia); Comptes Rendus de l’Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres: Paris, France, 1894; pp. 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Aymonier, É. Le Cambodge: Le Royaume Actuel; Ernest Leroux: Paris, France, 1900; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lunet de Lajonquière, É. Inventaire Descriptive des Monuments du Cambodge; Publ. de l’EFEO E (4), Ernest Leroux: Paris, France, 1902; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Morand, G. Notes et Images Pour Mieux Faire Connaître les Monuments et les Arts des Anciennes Civilisations du Cambodge et du Laos; Carqueiranne: Paris, France, 1907; Volume 2, pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier, H. Complément à l’inventaire descriptif des monuments du Cambodge. Bull. l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 1913, 13, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, H. Complément à L’art khmér primitif. Bull. l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 1935, 35, 1–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, I. Study on the Ancient Khmer City Isanapura. Ph.D. Thesis, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda, I.; Chan, V. Characteristics on the temple structures in the city zone of Sambor Prei Kuk: Focusing on the results of excavation survey at M.103 site. J. Southeast Asian Archaeol. 2024, 43, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chhum, M.; Shimoda, I.; Nakagawa, T. Construction and utilization dating of temples based on existing remains inside the city compound—Structure of the ancient Khmer city of Isanaura (Part I). J. Archit. Plan. 2013, 78, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, M.A.; Estrada-Belli, F.; Garrison, T.G.; Houston, S.D.; Acuña, M.J.; Kovác, M.; Marken, D.; Nondédéo, P.; Auld-Thomas, L.; Castanet, C.; et al. Ancient lowland Maya complexity as revealed by airborne laser scanning of northern Guatemala. Science 2018, 361, eaau0137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Airborne laser scanning as a method for exploring long-term socio-ecological dynamics in Cambodia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2016, 74, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizawa, Y. New Research on History of Ancient Cambodia; Fukyosha: Tokyo, Japan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wolters, O.W. Early Indonesian Commerce: Study of the Origins of Srivijaya; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, Greece; New York, NY, USA, 1967; pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Chhum, M. Historical Study on Basic Structure of Khmer Ancient City Isanapura. Ph.D. Thesis, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Groslier, B.-P. Introduction to the Ceramic Wares of Angkor. In Khmer Ceramics 9th–14th Century; Stock, D., Ed.; Southeast Asian Ceramic Society: Singapore, 1981; pp. 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Nakagawa, T. Reexamination on the dating of ceramics of Sambor Prei Kuk found by B. P. Groslier. J. Southeast Asian Archaeol. 2008, 28, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda, I.; Shimamoto, S. Spatial and Chronological Sketch of the Ancient City of Sambor Prei Kuk. Aséanie Sci. Hum. Asie Du Sud-Est 2012, 30, 11–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, N. Analysis of Vietnamese ceramics excavated from Kyushu in the 14th to 17th centuries—Dating, distribution and historical background. In Ceramic Distribution and the West Sea Region; Center for Cultural Interaction Studies, Kansai University: Osaka, Japan, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 23–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, N. Vietnamese ceramics recovered from archaeological research in the Lao, P.D.R. Showa Women’s Univ. Inst. Int. Cult. Bull. 2014, 21, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, C.B. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, P.J.; Austin, W.E.N.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Ramsey, C.B.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M.; et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0-55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, I.; Sugasawa, Y.; Yonenobu, H.; Tabata, Y. Research on the Active Habitation Period of the Ancient Khmer City Isanapura. J. Southeast Asian Archaeol. 2015, 35, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Goloubew, V. Chronique. Sambor Prei Kuk. Bull. l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 1927, 27, 489–492. [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda, I.; Chan, V.; Seng, K.; Hin, S. Restorative Studies on Prasat Sambor Temple in Sambor Prei Kuk Monuments. J. Southeast Asian Archaeol. 2008, 28, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.; Fletche, R.; Klassen, S.; Pottier, C.; Wijker, J. Trajectories of Urbanism in the Angkorian World. In The Angkorian World; Hendrickson, M., Stark, M.T., Evans, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, M. Southeast Asian urbanism: From early city to Classical state. In Early Cities in Comparative Perspective, 4000 BCE–1200 CE; Yoffee, N., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 74–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chevance, J.B. Banteay, palais royal de Mahendraparvata. Aséanie Sci. Hum. Asie Du Sud-Est 2014, 33, 279–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevance, J.B.; Pottier, C. The Early Capitals of Angkor. In The Angkorian World; Hendrickson, M., Stark, M.T., Evans, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pottier, C.; Desbat, A.; Dupoizat, M.-F.; Bolle, A. Le matériel céramique à Prei Monti (Angkor). In Orientalismes. De l’archéologie au Musée. Mélanges Offerts à Jean-François Jarrige; Lefecre, V., Ed.; Brepols: Turnhout, Belgium, 2012; pp. 291–317. [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier, H. L’Art Khmer Classique, les Monuments du Quadrand du Nord-Est; Publ. de L’EFEO: Paris, France, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda, I.; Chhum, M.; Chan, V.; Phin, S.; Ishizuka, M.; Shimoda, M.; Arakawa, C. Preliminary Survey on “Andong Preng”. In Koh Ker and Beng Mealea: Archietectural Study on the Provincial Sites of the Khmer Empire; Nakagawa, T., Mizoguchi, A., Eds.; Chuo Koron Bijutu Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Chevance, J.B.; Evans, D.; Hofer, N.; Sakhoeun, S.; Chhean, R. Mahendraparvata: An early Angkor-period capital defined through airborne laser scanning at Phnom Kulen. Antiquity 2019, 93, 1303–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groslier, B.-P. Programme de Recherches Urgentes à Angkor: Rapport Intermédiaire de Janvier 1962; Typescript Report; École française d’Extrême-Orient: Siem Reap, Cambodia, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Marchal, H. Notes sur le Palais Royal d’Angkor Thom. In Arts et Archéologie Khmers; Revue des Recherches sur les Arts, les Monuments et l’ethnographie du Cambodge, Depuis les Origines Jusqu’à Nos Jours; Notes sur le Palais Royal d’Angkor Thom: Paris, France, 1926; Volume 2, pp. 303–328. [Google Scholar]

- Marchal, H. Notes sur les Terrasses des Éléphants, du Roi lépreux et le Palais Royal d’Angkor Thom. Bull. l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 1937, 37, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ichita, S.; Vitharong, C.; Menghong, C. Large Terrace Structure Unearthed in the Heart of the City Zone of Īśānapura: Could It Be the ‘Great Hall’ Described in the Book of Sui? Heritage 2025, 8, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070258

Ichita S, Vitharong C, Menghong C. Large Terrace Structure Unearthed in the Heart of the City Zone of Īśānapura: Could It Be the ‘Great Hall’ Described in the Book of Sui? Heritage. 2025; 8(7):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070258

Chicago/Turabian StyleIchita, Shimoda, Chan Vitharong, and Chhum Menghong. 2025. "Large Terrace Structure Unearthed in the Heart of the City Zone of Īśānapura: Could It Be the ‘Great Hall’ Described in the Book of Sui?" Heritage 8, no. 7: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070258

APA StyleIchita, S., Vitharong, C., & Menghong, C. (2025). Large Terrace Structure Unearthed in the Heart of the City Zone of Īśānapura: Could It Be the ‘Great Hall’ Described in the Book of Sui? Heritage, 8(7), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070258