Copy/Past: A Hauntological Approach to the Digital Replication of Destroyed Monuments

Abstract

1. Introduction in Eight Events

- Event 1

- Event 2

- Event 3

- Event 4

- Event 5

- Event 6

- Event 7

- Event 8

2. How to Build a Specter

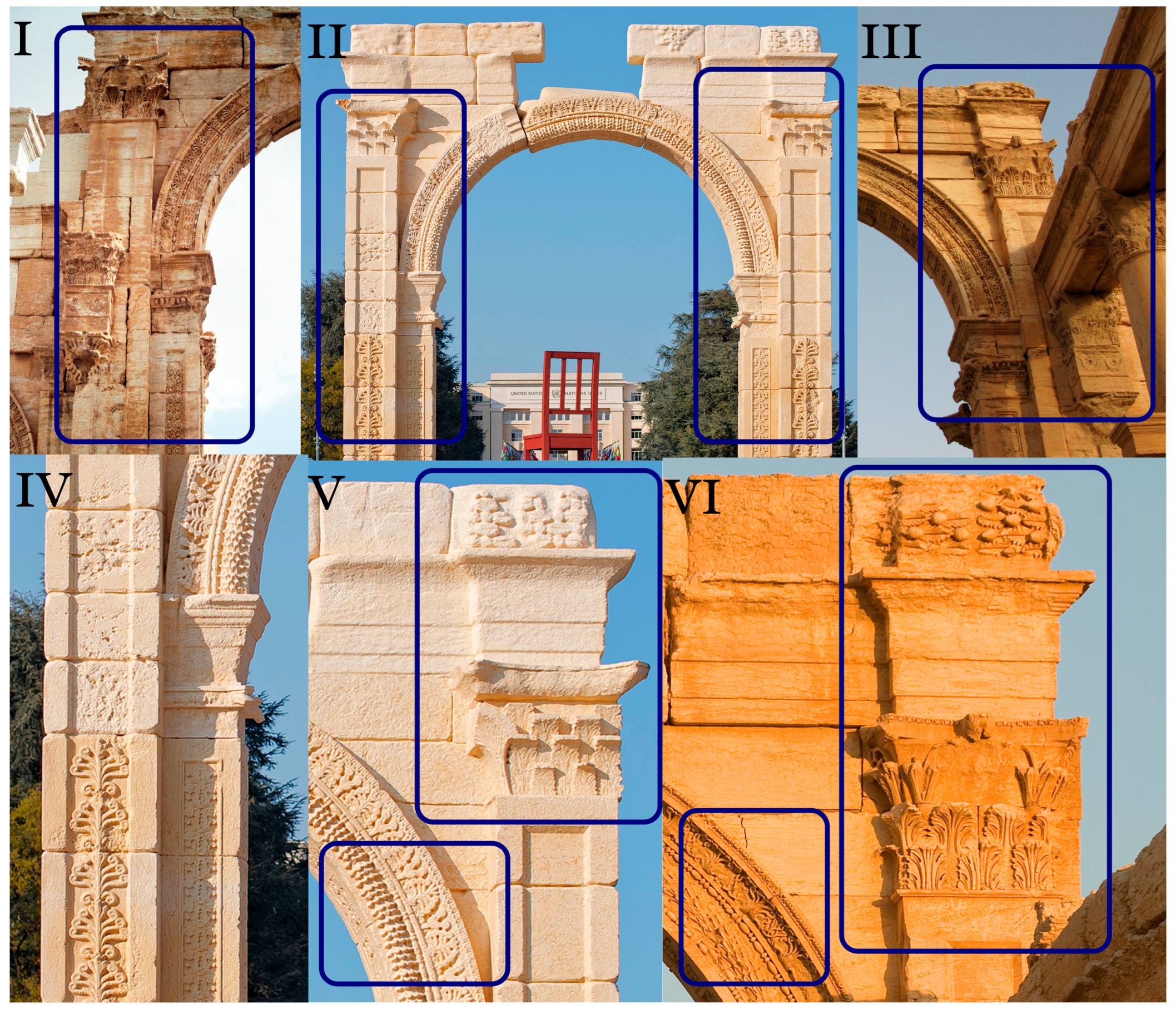

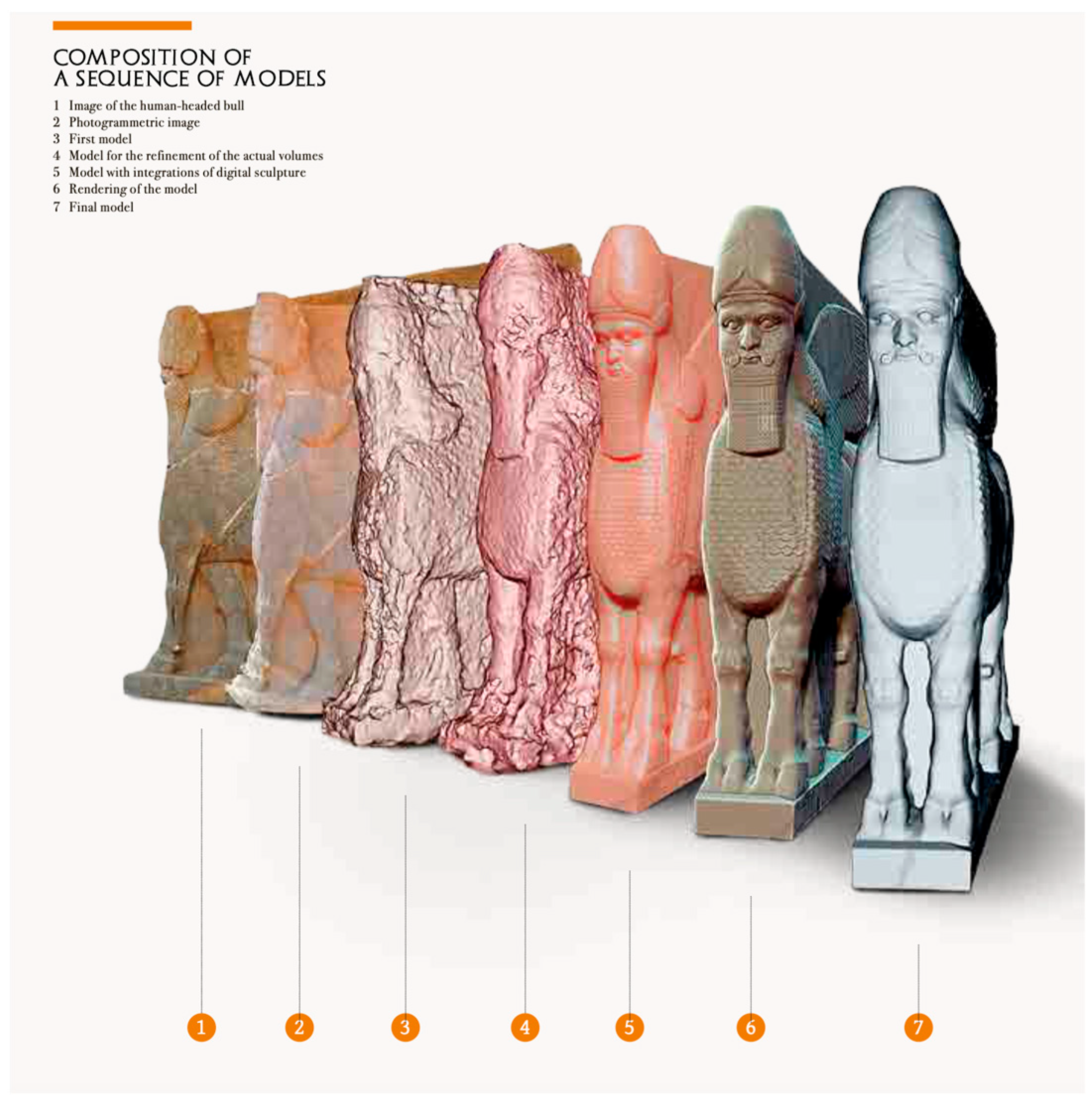

2.1. From Stone to Screen (and Back): Replicating the Arch and the Lamassu

2.2. Mourning Monuments: The Arch and the Lamassu as Specters

3. Specters on Display

- “The culture called more or less properly political (the official discourses of parties and politicians in power in the world, virtually everywhere Western models prevail, the speech or the rhetoric of what in France is called the ‘classe politique’) [26] (p. 52);

- “Mass-media culture: ‘communications’” and interpretations, selective and hierarchized productions of “information” [26] (p. 52);

- “Scholarly or academic culture” [26] (p. 53).

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

Appendix A.4

| 1 | New York City (City Hall Park, September 2016), Dubai (World Government Summit, February 2017), Florence (G7 Culture Summit, March–April 2017), Arona (ceremony for the renaming of the local archaeological museum in honor of Khaled al-Asaad, April 2017), Washington, D.C. (National Mall, September 2018), Geneva (Place des Nations, commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Second Protocol, April 2019), Bern (celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Swiss Commission for UNESCO, June 2019), and Luxembourg (December 2019–February 2020). The arch was originally intended to be sent to Syria as its final destination; following the initial announcement, no further updates have been provided regarding the monument’s future. A smaller version of the arch, produced as a part of the same project, is currently on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. |

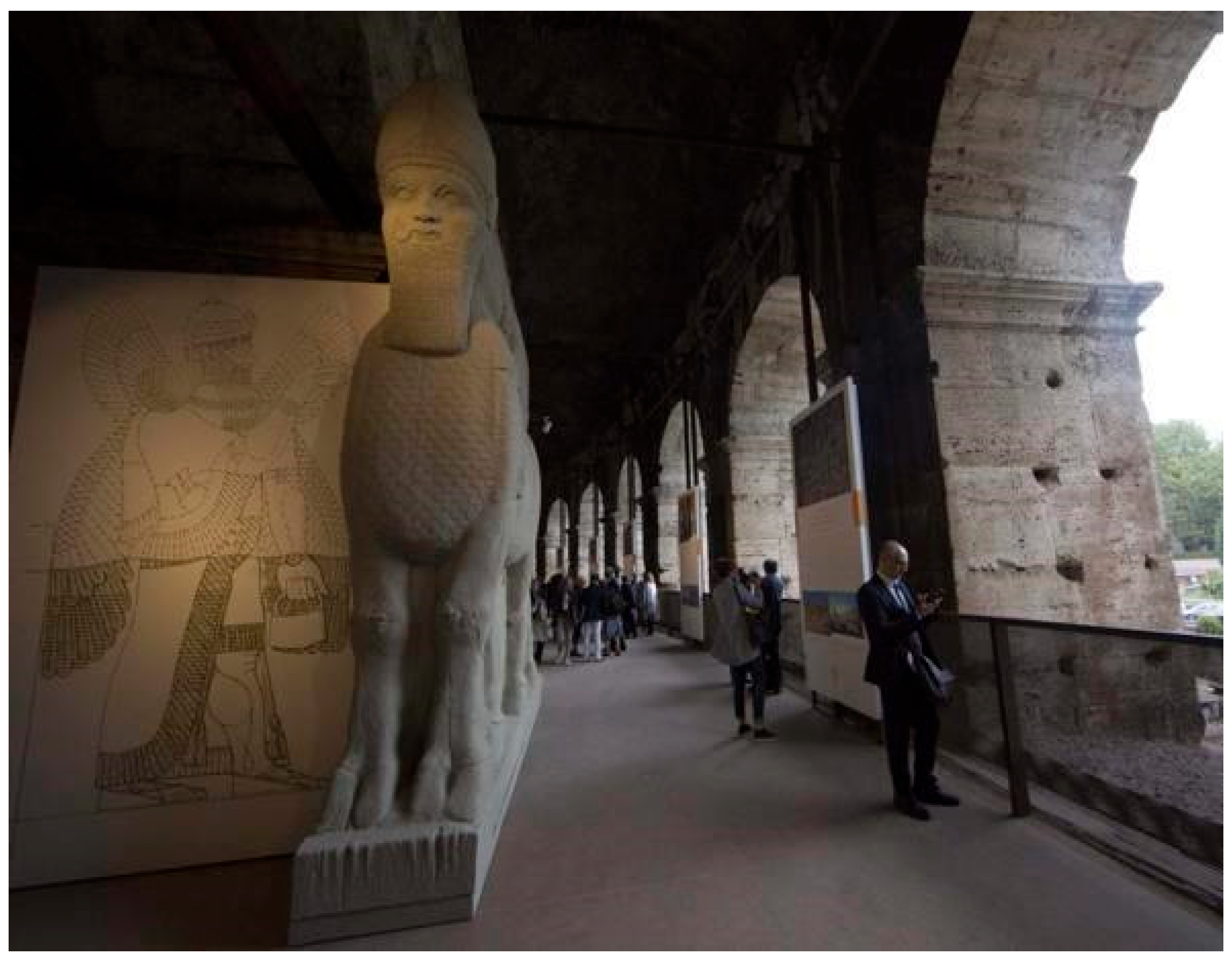

| 2 | In 2018, the Archive Room of Ebla was donated to University La Sapienza in Rome, and since April 2019, the replica of the Bēl Temple’s ceiling has been on display at the Damascus Museum. The Ebla Archive was exhibited in front of the headquarters of the European Council in the Justus Lipsius building in Brussels. Between November 2017 and January 2018, the lamassu was placed “in defense” of the entrance of the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. The ceiling of the Temple of Bēl was on display in the exhibition Palmyra: Rising from Destruction organized at FAO headquarters in Rome during the 30th ICCROM General Assembly (from 29 November to 1 December 2017), together with a funeral bust looted from Palmyra and recovered in Italy by the Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage. |

| 3 | “Armed with smartphones, DSLRs, or our proprietary lightweight, discreet, and easy-to-use 3D cameras, our dedicated volunteer photographers are capturing high-quality scans at important sites in conflict zones throughout the Middle East and North Africa. Images are uploaded through our web portal for inclusion in the open-source Million Image Database. These images will be used for research, heritage appreciation, educational programs, and 3D reconstruction” [19]. As of this writing, the database has not yet been made publicly accessible. |

| 4 | “The Institute for Digital Archaeology was, at that time, in the early stages of a documentation and cultural heritage protection project in collaboration with the people of the region. Plans were made to create a massive scale reconstruction of one of the well-known structures from the site for public display, using a combination of computer-based 3D rendering and a pioneering 3D-carving technology capable of creating very accurate renditions of computer-modeled objects in solid stone” [9]. |

| 5 | Digital colonialism and cultural appropriation are also closely tied to issues of copyright and economic control [47,48,49]. While a nation’s cultural heritage is not protected under copyright law, it has been noted that “the creators of digital models of these non-copyrightable cultural heritage artifacts most probably do have copyright protection” [47] (p. 172). This raises complex questions regarding the ownership of ‘replicas’ of monuments that no longer exist. If technology companies begin to market artworks produced through 3D modeling, carving, and printing—claiming to (re)create ‘copies’ of lost originals—what economic value would be attached to the fact that these are reproductions of objects no longer extant? The stakes of such questions are underscored by the sale of a relief from the Nimrud Palace at Christie’s (New York) in October 2018 for USD 31 million. How much might a ‘replica’ of the lost lamassu from the same site be worth? As a preliminary response to these concerns, it has been proposed that 3D models and images of heritage artifacts be made “openly accessible and downloadable for replication” [50]. This principle is partially supported by Article 2 of the 2003 UNESCO Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage, which states: “Access to digital heritage materials, especially those in the public domain, should be free of unreasonable restrictions”. On the broader ethical and political dimensions of 3D printing and the digitization of cultural heritage in Syria, see Morehshin Allahyari’s activist art project Material Speculation: ISIS, in which she critically engages with questions of loss, memory, and digital reconstruction [51,52]. |

| 6 | More media coverage of the IDA’s arch can be found on the Institute for Digital Archaeology’s website [18]. |

| 7 | Moreover, while UNESCO has always considered “authenticity” as a fundamental requirement to include an archeological site on the list of World Heritage sites, “replication on site, using modern synthetic materials and 3D-printing techniques, is now being promoted by preservationists in the United States and Western Europe as the best course of action for the future of the sites in Iraq and Syria” [64] (p. 113). |

| 8 | “In the midst of all these international plans for the future of the historical architecture, monuments, and sites of Iraq and Syria, what we have not heard are the voices of local scholars or local people. This exclusion is, perhaps, the direct result of the continuing claims—made by some influential cultural heritage preservationists and museum specialists in the West—that the local Iraqis and Syrians have no relationship with, or interest in, the ancient sites. These claims echo the ideology of ISIS, a deliberate dissociation of people from their historical landscape” [64] (pp. 117–118). It is worth quoting another excerpt from Andreas Schmidt-Colinet’s response to Horst Bredekamp: “What first must be rebuilt in Palmyra is the modern city, an essential infrastructure, houses, flats, a water system, … a nursery school, a school, a hospital, a mosque, a cemetery. Above all, people have to go back there: Human beings have to return to their houses. And then you can consider whether and how you rebuild the Temple of Bēl. And these decisions must be taken by those who, hopefully, will one day live there again peacefully” [66]. |

| 9 | In the context of the exhibition, two busts from Palmyra, severely damaged in 2015, were restored by the Italian Institute for Conservation and Restoration (ISCR) using 3D-printing technology. The missing parts of the busts were 3D-printed to complete the ancient objects. These busts were later repatriated to Syria and have been on display at an art school in Damascus since 2018, awaiting their return to the Palmyra Museum. |

References

- Bahrani, Z. Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barański, M. The Great Colonnade of Palmyra Reconsidered. Aram 1995, 7, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliou, C. Du Portique à la Rue à Portiques: Les Rues à Colonnades de Palmyre dans le Cadre de lʼUrbanisme Romain Impérial, Originalité et Conformisme. AAAS 1996, 42, 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Tabaczek, M. Zwischen Stoa und Suq. Die Säulenstraßen im Vorderen Orient in Römischer Zeit Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung von Palmyra. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität zu Köln, Köln, Germany, 2002. Available online: https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/1380/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Yon, J.-B. Les Notables de Palmyre; Presses de l’Ifpo: Beirut, Lebanon, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barański, M. Arch Construction in Palmyra (Syria). IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2012, 471, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R. Origins of the Colonnaded Streets in the Cities of the Roman East; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Intagliata, E. Urban Layout and Public Space: The Monuments of Palmyra in the Roman and Late Antique Periods. In The Oxford Handbook of Palmyra; Raja, R., Ed.; Oxford Handbooks: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- History of the Arch. The Institute for Digital Archaeology. Available online: http://digitalarchaeology.org.uk/history-of-the-arch (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Danti, M.; Branting, S.; Paulette, T.; Cuneo, A. Report on the Destruction of the Northwest Palace at Nimrud. ASOR Cult. Herit. Initiat. 2015. Available online: https://www.asor.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/ASOR_CHI_Nimrud_Report.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Sartre-Fauriat, A. Postludium: Palmyra and the Civil War in Syria. In The Oxford Handbook of Palmyra; Raja, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 579–594. [Google Scholar]

- Danti, M. Ground-Based Observations of Cultural Heritage Incidents in Syria and Iraq. Near East. Archaeol. 2015, 78, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuneo, A.; Penacho, S.; Danti, M.; Gabriel, M.; O’Connell, J. Special Report: The Recapture of Palmyra. ASOR Cult. Herit. Initiat. 2016. Available online: https://www.asor.org/chi/reports/special-reports/The-Recapture-of-Palmyra/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Hadingham, E. The Technology That Will Resurrect ISIS-Destroyed Antiquities; Public Broadcasting Station: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/digital-preservation-syria/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Eastaugh, S. Palmyra’s Ancient Triumphal Arch Resurrected in London’s Trafalgar Square; Cable News Network: USA. 2016. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/palmyra-triumphal-arch-replica-london/index.html (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Nadali, D. Rinascere dalle Distruzioni. Ebla, Nimrud, Palmira; Rotostampa: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Imam, J. Italy Donates 3D-Printed Replica of Statue Destroyed by ISIS to Iraq; Cable News Network, USA. 2024. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/02/13/style/bull-of-nimrud-replica-basrah-museum-tan/index.html (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- The Institute for Digital Archaeology. Available online: http://digitalarchaeology.org.uk/our-purpose (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- The Institute for Digital Archaeology. Available online: http://digitalarchaeology.org.uk/projects (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Khunti, R. The Problem with Printing Palmyra: Exploring the Ethics of Using 3D Printing Technology to Reconstruct Heritage. Stud. Digit. Herit. 2018, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstki, K. Digital Innovations in European Archaeology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triumphal Arch of Palmyra Under Construction. 2016. Available online: https://vimeo.com/161046225 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Jenkins, S. After Palmyra, the Message to Isis: What You Destroy, We Will Rebuild. The Guardian, 29 March 2016. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/mar/29/palmyra-message-isis-islamic-state-jihadis-orgy-destruction-heritage-restored (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Lowe, A. The IDA Palmyra Arch Copy. 2016. Available online: https://factumfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/palmyra_adamlowe2016-1-002.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Merantzas, C. From Real to Digital-Mediated Objects: Some Reflections Upon the Digital Reproduction of Archaeological Objects. Eur. Sci. J. 2014, 10, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International; Kamuf, P., Translator; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Luckhurst, R. The Contemporary London Gothic and the Limits of the “Spectral Turn”. Textual Pract. 2002, 16, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M. What Is Hauntology? Film Q. 2012, 66, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, C. Becoming Hauntologists: A New Model for Critical-Creative Heritage Practice. Herit. Soc. 2021, 14, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, C. Archaeology and Hauntology: An Ongoing, Stalled Conversation. Religions 2023, 14, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plissart, M.F.; Derrida, J. Right of Inspection; Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J.; Stiegler, B. Echographies of Television: Filmed Interviews; Bajorek, J., Translator; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Blackwell Publishers: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gere, C. The Hauntology of the Digital Image. In A Companion to Digital Art; Paul, C., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, M.P. Aura and Trace: The Hauntology of the Rephotographic Image. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J. Copy, Archive, Signature; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, F. Beyond the Cult of the Replicant. In Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse; Cameron, F., Kenderdine, S., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 50–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, A. The Work of Archaeology in the Age of Digital Surrogacy. In Visions of Substance: 3D Imaging in Mediterranean Archaeology; Olson, B.R., Caraher, W.R., Eds.; The Digital Press at The University of North Dakota: Grand Forks, ND, USA, 2015; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Garstki, K. Virtual Authority and the Expanding Role of 3D Digital Artefacts. In Authenticity and Cultural Heritage in the Age of 3D Digital Reproductions; Di Giuseppantonio Di Franco, P., Galeazzi, F., Vassallo, V., Eds.; McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatinus, D.L. Subjectivity and the Hauntology of the Digital. Acta Philol. 2020, 56, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hermon, S.; Niccolucci, F. Digital Authenticity and the London Charter. In Authenticity and Cultural Heritage in the Age of 3D Digital Reproductions; Di Giuseppantonio Di Franco, P., Galeazzi, F., Vassallo, V., Eds.; McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The London Charter for the Computer-Based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://londoncharter.org/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Eco, U. The Limits of Interpretation; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke, J.L. Colonial Past and Neocolonial Present: The Monumental Arch of Tadmor-Palmyra and So-Called Roman Architecture in the Near East. In Postcolonialism, Heritage, and the Built Environment: New Approaches to Architecture in Archaeology; Nitschke, J.L., Lorenzon, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cassibry, K. Reception of the Roman Arch Monument. AJA. 2018, 122, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobiecka, M. Archaeological Heritage in the Age of Digital Colonialism. Archaeol. Dialog. 2020, 27, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbembe, A. Necropolitics; Corcoran, S., Translator; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.L. Legal and Ethical Considerations for Digital Recreations of Cultural Heritage. Chap. Rev. 2017, 20, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, C. Whose Digital Heritage? Third Text 2019, 33, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, S. A Virtual Oasis: Trafalgar Square’s Arch of Palmyra. Archnet-IJAR 2017, 11, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S. The Ethics of 3D-Printing Syria’s Cultural Heritage. Forbes, 22 September 2016. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2016/09/22/does-nycs-new-3d-printed-palmyra-arch-celebrate-syria-or-just-engage-in-digital-colonialism/?sh=2538296377db (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Allahyari, M. Physical Tactics for Digital Colonialism. Performance-Lecture at New Museum (New York), 28 February 2019. Available online: https://medium.com/@morehshin_87856/physical-tactics-for-digital-colonialism-45e8d3fcb2da (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Qureshi, A.; Allahyari, M. On Digital Decolonization: A Conversation with Morehshin Allahyari. Front. J. Women Stud. 2020, 41, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamash, Z. “Postcard to Palmyra”: Bringing the Public into Debates over Post-Conflict Reconstruction in the Middle East. World Archaeol. 2017, 49, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turku, H. The Destruction of Cultural Property as a Weapon of War: ISIS in Syria and Iraq; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, S.; Isakhan, B. The Ritualization of Heritage Destruction under the Islamic State. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2018, 18, 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.W. Understanding ISIS’s Destruction of Antiquities as a Rejection of Nationalism. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2018, 6, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basulto, D. How 3D Printers Can Help Undo the Destruction of ISIS. The Washington Post, 7 January 2016. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/innovations/wp/2016/01/07/how-3d-printers-can-help-undo-the-destruction-of-isis/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Erasing Isis: How 3D Technology Now Lets Us Copy and Rebuild Entire Cities. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/27/isis-palmyra-3d-technology-copy-rebuild-city-venice-biennale (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Reinertz, M. Celebrating 25 Years of UNESCO Heritage (But Not Much Else…). Luxembourg Times, 10 January 2020. Available online: https://luxtimes.lu/culture-life/39503-celebrating-25-years-of-unesco-heritage-but-not-much-else (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Bevan, R. Should We Celebrate a Replica of the Destroyed Palmyra Arch? London Evening Standard, 24 May 2016. Available online: https://www.standard.co.uk/insider/style/should-we-celebrate-a-replica-of-the-destroyed-palmyra-arch-a3233496.html (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Voon, C. What’s the Value of Recreating the Palmyra Arch with Digital Technology? Hyperallergic, 19 April 2016. Available online: https://hyperallergic.com/292006/whats-the-value-of-recreating-the-palmyra-arch-with-digital-technology/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Taylor, A. The Problem with Rebuilding a Palmyra Ruin Destroyed by ISIS—Does It Simply Help Assad? The Washington Post, 20 April 2016. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/04/20/the-problem-with-rebuilding-a-roman-ruin-destroyed-by-isis-does-it-simply-help-assad/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Nodjimbadem, K. The Heroic Effort to Digitally Reconstruct Lost Monuments. Smithsonian Magazine, March 2016. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/heroic-effort-digitally-reconstruct-lost-monuments-180958098/?no-ist (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Bahrani, Z. Destruction and Preservation as Aspects of Just War. Future Anterior 2017, 14, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Colinet, A. No Temple in Palmyra! Opposing the Reconstruction of the Temple of Bel. Syr. Stud. 2019, 11, 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Colinet, A.; Zederbauer, A. We Should Do Nothing!” On the History, Destruction and Rebuilding of Palmyra. Eurozine, 22 December 2017. Available online: https://www.eurozine.com/we-should-do-nothing-on-the-history-destruction-and-rebuilding-of-palmyra/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Munawar, N.A. Reconstructing Cultural Heritage in Conflict Zones: Should Palmyra Be Rebuilt? Ex Novo-J. Archaeol. 2017, 2, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younan, S. Poaching Museum Collections Using Digital 3D Technologies. JSTA 2015, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.; Stott, J.; Warnett, J.M.; Attridge, A.; Smith, M.P.; Williams, M.A. Evaluation of Touchable 3D-Printed Replicas in Museums. Curator Mus. J. 2018, 60, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutelli, F. Man can re-build what has been destroyed, if he wants. In It is Possible to Reproduce Destroyed Things: 5 Years of International Campaigns, Their Results, the Perspectives of a New “Soft Power”; Rotostampa: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.L. Recreating the Past in Our Own Image: Contemporary Artists’ Reactions to the Digitization of Threatened Cultural Heritage Sites in the Middle East. Future Anterior 2018, 15, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, W. Illuminations; Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 217–251. [Google Scholar]

- Schweibenz, W. The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction. Museum 2018, 70, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B.; Lowe, A. The Migration of the Aura, or How to Explore the Original through Its Facsimiles. In Switching Codes: Thinking Through Digital Technology in the Humanities and the Arts; Bartscherer, T., Coover, R., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; pp. 275–298. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lovisetto, G. Copy/Past: A Hauntological Approach to the Digital Replication of Destroyed Monuments. Heritage 2025, 8, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070255

Lovisetto G. Copy/Past: A Hauntological Approach to the Digital Replication of Destroyed Monuments. Heritage. 2025; 8(7):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070255

Chicago/Turabian StyleLovisetto, Giovanni. 2025. "Copy/Past: A Hauntological Approach to the Digital Replication of Destroyed Monuments" Heritage 8, no. 7: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070255

APA StyleLovisetto, G. (2025). Copy/Past: A Hauntological Approach to the Digital Replication of Destroyed Monuments. Heritage, 8(7), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070255