Revitalizing the Estrada do Paraibuna: Exploring Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

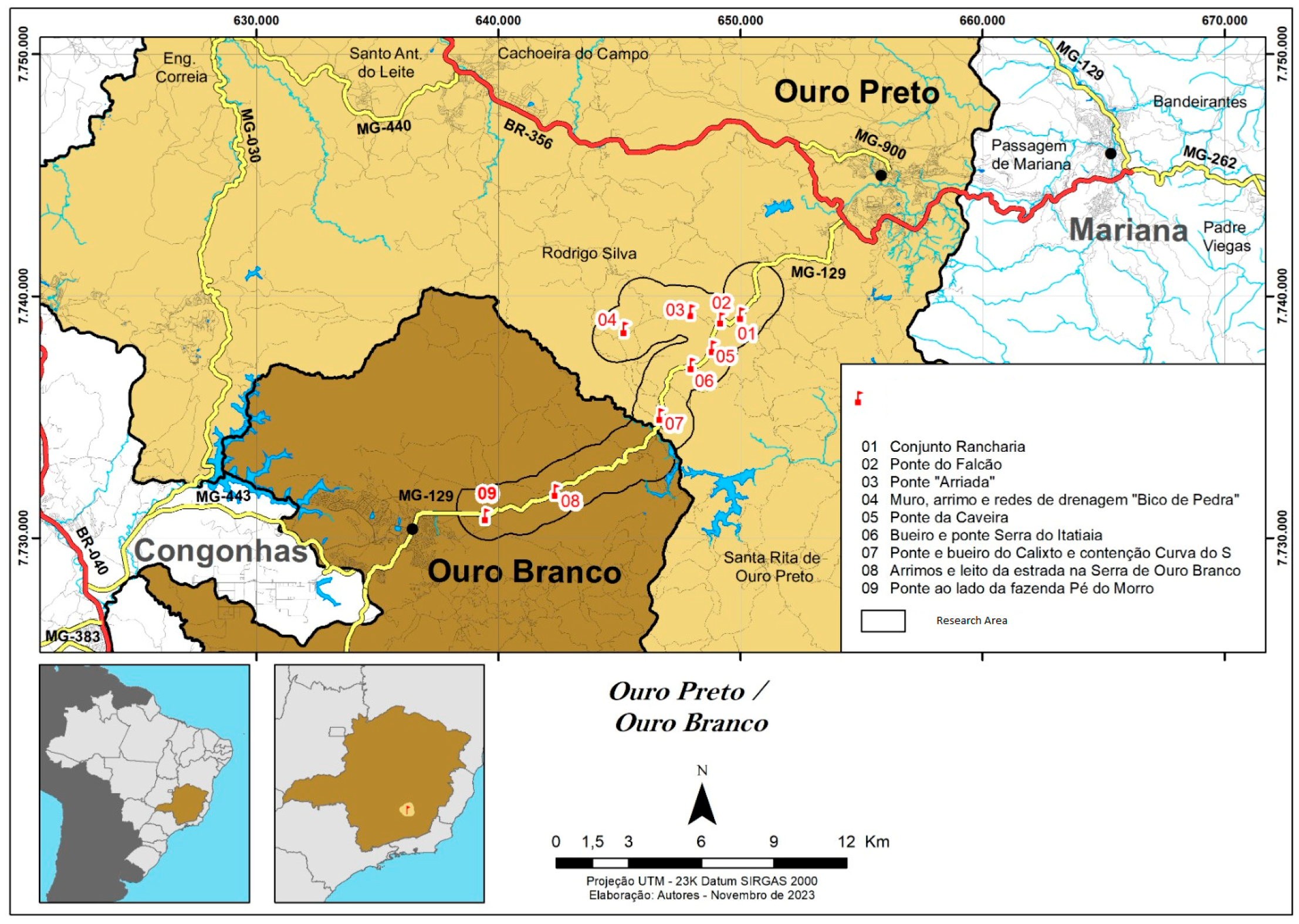

2. The Historical Road Estrada do Paraibuna

3. Methodological Approach

- Analyze and describe the natural and cultural environment around the Paraibuna Road.

- Note the primary threats identified to the heritage along Paraibuna Road.

- Identify priority actions that need to be taken to maintain or restore the conservation state.

- Identify new cultural resources with tourism potential.

4. Results and Discussion

- Context Description: This category analyzes the local setting, highlighting the historical significance of ancient trails within a unique landscape characterized by abundant waterscapes, including rivers and streams. The natural environment—featuring caves, forests, and river beaches—emerged as the most significant aspect, with a consensus on the need for its preservation due the relevance for tourism and local development.

- Culturally Significant Elements for Tourism and Local Valorization: This category identifies cultural resources with economic potential that reflect the identity and historical heritage of the local culture in a prominent and meaningful way.

- Threat Identification: This category encompasses all the primary threats to the heritage along Paraibuna Road and recognizes and addresses these challenges effectively.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krleza, P.; Behaim, J.; Kranjec, I.; Jurkovic, M. Recreating Historical Landscapes: Implementation of Digital Technologies inArchaeology. Case Study of Rab, Croatia. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), Funchal, Portugal, 25–27 September 2018; pp. 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. 1972. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- UNESCO. Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas. 1976. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/recommendation-concerning-safeguarding-and-contemporary-role-historic-areas (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Salerno, R. Representation and Visualization Processes for a Sustainable Approach to Landscape/Heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Burra Charter. 1999. Available online: https://icomosubih.ba/pdf/medjunarodni_dokumenti/1999%20Povelja%20iz%20Burre%20o%20mjestima%20od%20kulturnog%20znacenja.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- ICOMOS-IFLA. Principles Concerning Rural Landscapes as Heritage. 2017. Available online: https://www.icomos.pt/images/pdfs/2020/2017%20carta%20ICOMOS-IFLA%20sobre%20paisagens%20rurais.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention. 2000. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape/text-of-the-european-landscape-convention (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- UNESCO. Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. 2006. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000142919 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- ICOMOS. The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. 2008. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/3140/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Scorza, F.; Gatto, R.V. Identifying Territorial Values for Tourism Development: The Case Study of Calabrian Greek Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahle, M.; Saito, O. Mapping and characterizing the Jefoure roads that have cultural heritage values in the Gurage socio-ecological production landscape of Ethiopia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dax, T.; Tamme, O. Attractive Landscape Features as Drivers for Sustainable Mountain Tourism Experiences. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 4, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentz, M.; Albert, N. Cultural Landscapes as Potential Tools for the Conservation of Rural Landscape Heritage Values: Using the Example of the Passau Abbey Cultural Site. Mod. Geográfia 2023, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Pforr, C.; Dit, J.T. Exploring the regenerative potential for community-based ecotourism in the Niah National Park in Sarawak, Malaysia. J. Ecotourism 2024, 23, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll-Barneto, I.; Fusté-Forné, F. Understanding Environmental Actions in Tourism Systems: Ecological Accommodations for a Regenerative Tourism Development. J. Tour. Sustain. Well-Being 2023, 11, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawu, M.R.; Adikampana, I.M.; Arida, I.N.S. Empowering Communities in the Development of Regenerative Tourism in Koja Doi Tourism Village, Sikka Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province. Asian J. Soc. Humanit. 2024, 2, 1676. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Salgado, M.A.B.; Silva, R. Resilient and regenerative Rural Tourism: The case of Travancinha Village, Portugal. Cad. Geogr. 2023, 48, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omma, F.M. Regenerative nature-based tourism: Tour guides and stakeholder dynamics in Arctic Norway. J. Tour. Futures 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellato, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Nygaard, C.A. Regenerative tourism: A conceptual framework leveraging theory and practice. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 25, 1026–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedes-Ugarte, B.; Flores-Ruiz, D. Strategies for the Promotion of Regenerative Tourism: Hospitality Communities as Niches for Tourism Innovation. Adm. Sci. 2024, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Matas, J.A.; Rivera, J.Y. Local Development through Cultural Routes: The Case of San José de Chiquitos (Bolivia). Sociol. Tecnociencia 2025, 15, 176–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F.; Hussain, A. Regenerative leisure and tourism: A pathway for mindful fu-tures. Leisure/Loisir 2025, 49, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N.; de Castro, T.V.; Silva, S. Culture–tourism entanglements: Moving from grassroots practices to regenerative cultural policies in smaller communities. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2025, 31, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revollo-Fernández, D.A.; Lithgow, D.; Von Thaden, J.J.; Salazar-Vargas, M.D.P.; Rodríguez de los Santos, A. Unlocking Local and Regional Development through Nature-Based Tourism: Exploring the Potential of Agroforestry and Regenerative Livestock Farming in Mexico. Economies 2024, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawu, M.R.; Ridla, M. Tourist engagement model of regenerative tourism destinations: A case study of Egon Buluk tourism village, Sikka Regency, East Nusa Tenggara province. J. Glob. Hosp. Tour. 2024, 3, 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fuste-Forn, F.; Hussain, A. Regenerative tourism futures: A case study of Aotearoa New Zealand. J. Tour. Futures 2022, 8, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeser, H.M.P.; Roeser, P.A. O Quadrilátero Ferrífero-MG, Brasil: Aspectos sobre sua história, seus recursos minerais e problemas ambientais relacionados. Geonomos 2010, 8, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamim-Guedes, V. Uma análise histórico-ambiental da região de Ouro Preto pelo relato de naturalistas viajantes do século XIX. Filos. História Biol. 2010, 5, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Rezende, V.L. A mineração em Minas Gerais: Uma análise de sua expansão e os impactos ambientais e sociais causados por décadas de exploração. Soc. Nat. 2016, 28, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhouri, A. Crise como criticidade e cronicidade: A recorrência dos desastres da mineração em Minas Gerais. Horiz. Antropológicos 2023, 29, e660601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.G. Registros do Caminho Novo para as minas de ouro nos mapas antigos. Atas Do VI Simpósio Luso-Bras. Cartogr. Histórica 2015, 4, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pimenta, D.J. Caminhos de Minas Gerais; Imprensa Oficial: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.Q.X. Caminho e poder: Uma análise arqueológica do Caminho Novo em Minas Gerais. Século XVIII. Vestígios-Rev. Lat.-Am. Arqueol. Histórica 2015, 9, 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venancio, R.P. Caminho Novo: A longa duração. Varia História 1999, 15, 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Assis, M.C.L.; Vieira Filho, N.A.Q. Turistas e a Estrada Real: Um estudo de caso no trecho Ouro Preto-Ouro Branco. ANPTUR. IV Seminário da Associação Brasileira de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Turismo UAM—27 a 28 de Agosto de 2007. Available online: https://www.anptur.org.br/anais/anais/files/4/50.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Martoni, R.M.; Varajão, G.F. Caminhos Opostos: Turismo nas Estradas Reais de Minas Gerais; Livre Expressão Editora: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, A.; Barella, C.; Gomes, G.J. O Estado Socioambiental do Território Ouro-Pretano. Relatório PromoSAT. 2022. Available online: https://turismoepatrimonio.ufop.br/news/programa-promosat-op-valoriza%C3%A7%C3%A3o-do-patrim%C3%B4nio-ouro-pretano (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Freitas, I.V.; Martoni, R.M.; Bruno, K.A. Elementos do valor patrimonial e de memória. Enfoque desde Itatiaia (Ouro Branco, MG, Brasil). PatryTer Rev. Latinoam. Caribenha Geogr. Humanidades 2023, 6, e42445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Lima, C.; de Azevedo Ruchkys, Ú. Potencial geoturístico dos distritos do município de Ouro Preto com uso de geotecnologias. Geosul 2019, 34, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, A.M.A.; Ferraz, C.M.L.; Giovanini, R.; Júnior, T.T.N. A paisagem geográfica de Lavras Novas, ouro Preto: Uma apologia à “Morfologia da Paisagem” de Carl O. Sauer. Cad. Geogr. 2003, 13, 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Varajão, G.F.D.C.; Diniz, A.M.A. Turismo, produção do espaço e urbanização: Evolução do uso e ocupação do solo de Lavras Novas, Ouro Preto-MG. Cad. Geogr. 2014, 24, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.L. O ouro branco: Possibilidades do turismo gastronômico associado ao queijo artesanal na cidade do Serro, a Mater do norte de Minas. In Gastronomia e Vinhos: Contributos Para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável do Turismo Estudos de Caso-Brasil e Portugal; Henriques, C.H., Varela, L., Santos, M., César, P.D.A.B., Herédia, V.B.M., Eds.; Educs: Caxias do Sul, Brazil, 2020; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mucivuna, V.C.; Garcia, M.D.G.M.; Reynard, E.; da Silva Rosa, P.A. Integrating geoheritage into the management of protected areas: A case study of the Itatiaia National Park, Brazil. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2023, 10, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, V.; Levi, D. Observational Methods in Education Research: Balancing Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 20, 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Grodal, S.; Anteby, M.; Holm, A.L. Achieving rigor in qualitative analysis: The role of active categorization in theory building. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, A.; Sharma, B. Regenerative tourism: Opportunities and challenges. J. Responsible Tour. Manag. 2023, 3, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Martínez-Puche, A.; Lois-González, R.C. Heritage, Tourism and Local Development in Peripheral Rural Spaces: Mértola (Baixo Alentejo, Portugal). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D. Regenerative tourism: Transforming mindsets, systems and practices. J. Tour. Futures 2022, 8, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezio, C. Una lectura biorregional de los paisajes rurales de las zonas interiores italianas y el potencial regenerativo del turismo rural. El caso del proyecto VENTO. Ciudades 2020, 23, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

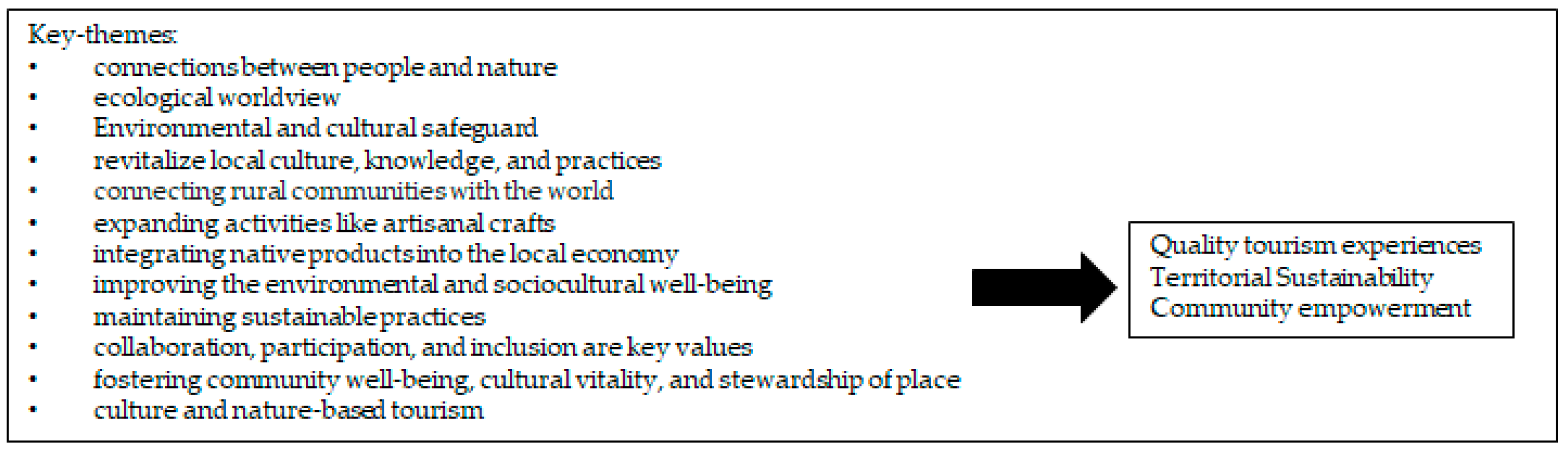

| Omma [18] | Omma emphasizes that the regenerative approach in tourism highlights ongoing investments in three main areas: people, places, and nature, to support the development of healthy and flourishing social and ecological places by immersive experiences in nature. This approach encourages connections between people and nature, promoting appreciation, understanding, and care for the natural world among visitors [19]. In this context, the regenerative approach seeks to create sustainable and mutually beneficial relationships between humans and their surroundings, ensuring resilience and well-being for both. |

| Bellato, Frantzeskaki, and Nygaard [19] | Bellato, Frantzeskaki, and Nygaard present key principles for regenerative tourism. These include grounding regenerative tourism in an ecological worldview, utilizing living system thinking in design to foster healthy and transformative change, and exploring the unique potential of places and communities. They emphasize identifying synergies between stakeholders and communities to drive transformations, employing strategies to revitalize local culture, knowledge, and practices, and creating regenerative places and communities by enhancing capacities and embracing regenerative practices. Additionally, collaborative participation is deemed essential to the regeneration process. |

| Miedes-Ugarte and Flores-Ruiz [20] | Miedes-Ugarte and Flores-Ruiz highlight the potential of small communities to become hubs of innovation within regenerative tourism by revitalizing key local stories, which can serve as the foundation for unique tourism experiences. The establishment of a collaborative platform has been crucial in connecting these rural communities to broader European networks while preserving their autonomy over cultural narratives and assets, enabling local stakeholders to retain control. This approach integrates digital platform skills with heritage restoration, fostering connections through regional initiatives and international partnerships. Thoughtfully managing expectations ensures that a delicate balance between conservation objectives and tourism development is achieved. |

| Valero-Matas and Rivera [21] | Valero-Matas and Rivera emphasize the need for a localized tourism strategy that leverages cultural and natural attractions while addressing resource limitations. Success relies on sustainable investments, municipal collaboration, cooperative models, and preserving cultural heritage. Expanding activities like artisanal crafts and integrating native products into the local economy are key, along with an inclusive plan that balances growth with environmental conservation. |

| Fusté-Forné and Hussain [22] | Fusté-Forné and Hussain highlight the transformative potential of regenerative efforts by advocating for innovation that supports both ecological systems and the communities that depend on them. They focus on redefining leisure and tourism—not as a niche activity, but as a holistic framework that fosters meaningful relationships between people and nature. In their perspective, regeneration in tourism is approached with a dual purpose: improving the environmental and sociocultural well-being of host communities while maintaining sustainable practices. This approach also includes empowering communities to connect deeply with their environment, further aligning the goals of regeneration with shared prosperity and ecological stewardship. |

| Duxbury, de Castro, and Silva [23] | Duxbury, de Castro, and Silva argue that collaboration, participation, and inclusion are key values in projects that engage local creators, strengthen networks, and connect with visitors. Expanding local cultural policy involves adopting an ecosystemic approach that recognizes culture’s interdependencies with other aspects of life. An integrated, holistic strategy focuses on long-term development, fostering community well-being, cultural vitality, and stewardship of place. |

| Revollo-Fernández et al. [24] | Revollo-Fernández et al. highlight key competencies for human capital: environmental education to identify biodiversity, tourism management for quality experiences, financial planning for economic feasibility, and resilience strategies. The author argues that success relies on collective action, equitable benefit-sharing, stakeholder collaboration, partnerships, and resource access to sustain nature-based tourism. |

| Categorized Dimensions | Theme |

|---|---|

| Context description Key dimension: Analyze and description of the context around the Paraibuna road for tourism and local development | Ancient trails of significance and historical use Mountain unique landscape Frequent waterfalls Rivers and streams that could be explored for tourism Natural caves and geosites, natural elements in the road context Ecological reserves Forests with significant biodiversity Beaches along rivers that could be interesting resources Natural Parques with nature protection and safeguard |

| Culturally significant elements for tourism: Key dimension: Identification of cultural resources with economic potential | Traditional villages with historical heritage, tangible and intangible in risk of disapearence by the population decreasing Saramenha ceramic Intangible heritage and storytelling linked with local stories and traditions Villages and places dating from the 16th century, from the first days of Brazil Farms, estates, and ranches dated from the 16th century Religious monuments–churches and monasteries Old and traditional villages of Lavras Novas, Chapada, and Itatiaia with wattle and daub architecture Road with remarkable beauty Beautiful landscapes Historical and traditional bridges, culverts, retaining walls, stormwater galleries, constructed, drainage networks, and cobblestone beds with traditional techniques The constructions (houses and churches) built with traditional stucco techniques are in ruins. The local festivities, many of which are no longer continued, were once enlivened by music bands. The old local shops that supported travelers are themes to be revived. The fountains that supplied the towns but also provided comfort to travelers. The agricultural plantations, which still influence local toponymy, also sold goods and artisanal products; for instance, in towns along the Road, they are examples of local exploitation and trade: cheese, cornmeal, coffee, and fruits. The local stories and legends, such as the “Mãe de Ouro” (Mother of Gold) or the “Mula sem Cabeça” (Headless Mule), or the events that marked the passage of known or strange people, are stories connected to the road that should be brought back. The connection of people to nature and the practice of using natural infusions as a cure for illnesses. |

| Threat Identification Key dimension: Signalization of the primary threats identified to the heritage along Paraibuna Road | Mining is a problem and it is the changing landscape, transforming those places into dangerous places. The pollution caused by intense mining, resulting in unpleasant odors Trucks in constant traffic. Heavy trucks using parts of the road significantly compromise the safety of users, visitors, and tourists and degrade the pavement. Dangerous road curves. Abandoned parts of the roads. Stonework artworks taken over by the forest. Part of the road is now a local road to connect different rural areas. Part of the historic road was paved. Part of the road came to be used by trucks serving mining companies Vegetation has practically taken over the Rancharia and Falcão bridges, as well as the ruins of the Arriada Bridge, making observation difficult. Many of the remnants of the road are overgrown with vegetation and are targets of vandalism and/or misuse. The old sections of the road contain waste and debris. The highway, without a shoulder, with sharp curves and many ascents and descents due to the topographical features of the region |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freitas, I.V.d.; Martoni, R.M. Revitalizing the Estrada do Paraibuna: Exploring Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism Dynamics. Heritage 2025, 8, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060214

Freitas IVd, Martoni RM. Revitalizing the Estrada do Paraibuna: Exploring Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism Dynamics. Heritage. 2025; 8(6):214. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060214

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreitas, Isabel Vaz de, and Rodrigo Meira Martoni. 2025. "Revitalizing the Estrada do Paraibuna: Exploring Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism Dynamics" Heritage 8, no. 6: 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060214

APA StyleFreitas, I. V. d., & Martoni, R. M. (2025). Revitalizing the Estrada do Paraibuna: Exploring Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism Dynamics. Heritage, 8(6), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060214