1. Introduction

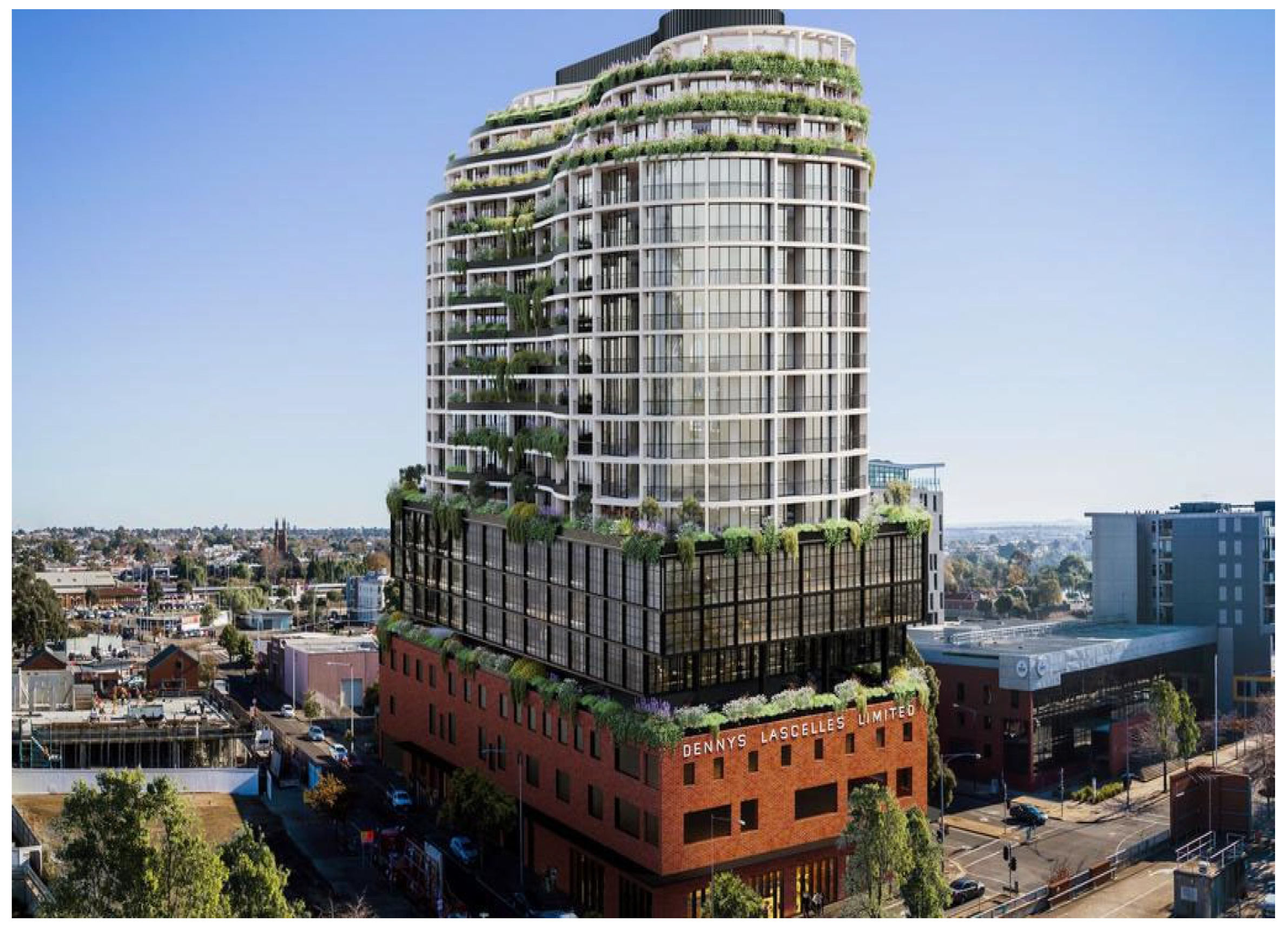

The future of the currently vacant former Dennys Lascelles Wool store, aged more than a hundred and located at 20 Brougham Street, is under dispute between the state government and a property developer (

Figure 1). This building was once part of the old Dennys Lascelles wool store. The store had different parts: the current National Wool Museum Building, which is now a museum and protected for its heritage, and the legendary bow truss building, also heritage-listed. Unfortunately, the bow truss building was demolished in the nineties. Now, there is a new TAC building on that spot. As for the building we are talking about, it has been empty for many years. The state government raised opposition against the proposed design reuse plan with the argument that the developer has neglected the building’s contribution to a valuable part of Geelong’s history and identity [

1]. In the meantime, Heritage Victoria declined the inclusion of this building in the Victorian Heritage List and rejected its nomination proposal, although the former wool store is part of an exceptional collection of former wool store buildings located in the Geelong CBD and represents a tangible legacy of the city’s role as the wool capital of Victoria [

2].

The founder of this wool store company, Charles John Dennys, has been described as the father of Geelong’s wool industry. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his company, Dennys Lascelles Austin & Co, Australia established a number of wool stores concentrated within a city block, strategically positioned between the commercial hub of Geelong and the harbor vicinity in Corio Bay, which were not only housing the wool bales but also displaying them for potential buyers [

3]. Constructed between 1872 and 1926–30, these wool stores covered a substantial portion of the city block in Moorabool and Brougham Streets. Within this complex of buildings, two of them have evaded demolition, one has been adapted into a Geelong National Wool Museum, but the other, as a legacy of the expansion of Dennys Lascelles in the early 1950s, has sat vacant for decades with its future being under a debate and at risk of unresponsive redevelopment.

2. Objective

This paper challenges the dominant conservation narrative by advocating for an integrated approach—one that values emotional connections, leverages digital documentation for engagement and memory-making, and aligns with sustainable reuse principles. It is a call to action for policymakers, heritage professionals, and urban planners to rethink how we define, preserve, and interact with heritage in a fast-changing world.

The primary objective of this paper is to advocate for a multidimensional framework of heritage conservation that:

Recognizes the Role of Affect: Emphasizes the emotional, sensory, and social connections people have with heritage sites, moving beyond strictly material preservation.

Leverages Digital Heritage Tools: Promotes the use of digital technologies to document, visualize, and interpret both tangible and intangible heritage elements, thereby enhancing accessibility, engagement, and educational value.

Applies Circular Economy Principles: Encourages sustainable strategies for adaptive reuse of remaining historic structures, allowing heritage to function dynamically within evolving urban landscapes.

Critiques the Limitations of AHD: Challenges the dominant preservation narrative that often prioritizes physical fabric over lived experiences and memory.

Through the case of the Dennys Lascelles Wool Store, the paper seeks to demonstrate how these interconnected approaches can offer a more inclusive, resilient, and sustainable model for heritage conservation in the digital age.

3. Methodology

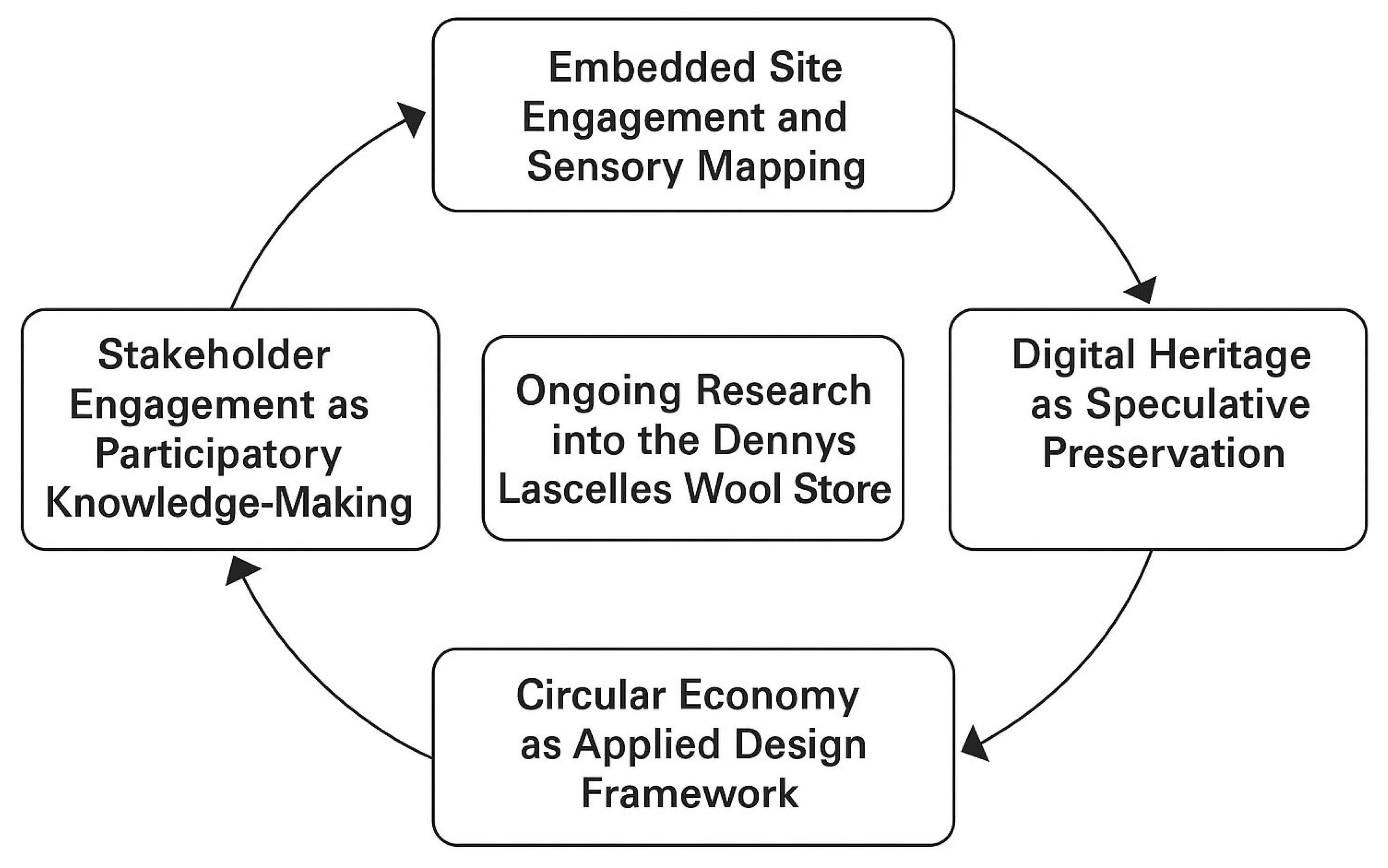

This ongoing research into the Dennys Lascelles Wool Store adopts a transdisciplinary and situated methodology (

Figure 2), aligning with our central position: that heritage conservation must evolve to recognize emotional connections (affect), leverage digital heritage tools, and engage circular economy strategies. Rather than treat heritage as a static object of preservation, our approach positions it as a living, affective, and adaptable system shaped by people, places, and technologies in flux.

1. Stakeholder Engagement as Participatory Knowledge-Making

At the core of our methodology is the understanding that heritage value is co-constructed. In this context, stakeholder interviews are not only a data collection tool but a platform for participatory meaning-making. Ongoing focus group interviews with a diverse group—including community members, heritage practitioners, digital preservation experts, urban planners, and sustainability advocates—inform a richer, more inclusive understanding of the Wool Store’s legacy. These interviews are to be conducted in different stages initially with an online survey and later multiple focused group interviews with different groups separately (e.g., Heritage experts, community members, etc.).

These conversations provide insights into how the site is remembered, experienced, and imagined across generations and professions. This multiplicity of perspectives challenges the materialist bias of Authoritative Heritage Discourse (AHD) and elevates the emotional, sensory, and lived dimensions of heritage.

2. Embedded Site Engagement and Sensory Mapping

We adopt an ethnographic approach through sustained site observation and engagement. By ethnographic approach, we emphasize people’s experiences associated with the heritage building and their connection with the building. The survey questions include users’ evaluation of the proposed reuse as well as their perception of the building with their collective memories. Beyond documenting the physical remnants of the Wool Store, we pay close attention to affective atmospheres, informal uses of space, and the site’s evolving presence within the urban fabric of Geelong. These observations help us capture heritage as it is performed and felt—not just preserved.

3. Digital Heritage as Hypothetical Preservation

Digital tools—3D modeling, photogrammetry, and immersive media—are currently being deployed to document, reconstruct, and reimagine both the lost and extant elements of the Wool Store. The digital reproduction of the demolished bow truss structure serves as a critical act of preservation, allowing it to persist in virtual form while becoming accessible and engaging to the public.

Rather than replicate traditional museological practices, we approach digital heritage as hypothetical: a way to visualize alternative futures for heritage, expand narratives, and democratize engagement. These technologies act as both archive and interface—bridging affective memory, public storytelling, and sustainable conservation.

4. Circular Economy as Applied Design Framework

In parallel, the research applies circular economy thinking as a design methodology. We are currently collaborating with architects and designers to explore adaptive reuse strategies for the remaining portions of the Wool Store complex. This includes:

- (i)

Assessing materials for potential reuse and embodied energy value.

- (ii)

Identifying programmatic opportunities that serve community needs while retaining cultural resonance.

- (iii)

Testing speculative design interventions that marry historical continuity with contemporary relevance.

- (iv)

Here, the Wool Store becomes a laboratory for circular heritage thinking—where architecture, memory, and sustainability intersect.

This methodology is not fixed but evolves in response to site-specific findings, community insights, and technological potentials. It reflects our belief that heritage practice in the digital age must be agile, inclusive, and forward-looking. By embedding affect, digital mediation, and circular design at the core of the research process, we aim to develop a replicable framework that not only preserves heritage sites in meaningful ways but also repositions them as agents of sustainable urban futures. The study is currently ongoing and this is based on positioning the concept. We are also developing sensory maps at the next stage that register not only what is seen, but what is remembered, evoked, and desired. This methodological lens reinforces our position that affect is foundational to heritage value.

4. Theoretical Framework

This study is designed for a new approach to heritage conservation—one that goes beyond traditional methods by including affective connections, digital tools, and circular economy ideas. As cities change and grow, heritage practices need to adapt. Using the example of the Dennys Lascelles Wool Store in Geelong, this paper argues that current conservation models, based on the traditional Authoritative Heritage Discourse (AHD), are no longer enough. These models often fail to capture the full value of industrial heritage, especially when buildings are modified or no longer physically present. The ensuing paragraphs will discuss this idea in detail.

4.1. What Should We Preserve: Authoritative Heritage Discourse (AHD)

Since the initial stages of acknowledging the imperative for protecting world heritage, historic landscapes generally faced two dominant black-and-white scenarios based on international corporations’ defined scope of heritage. In accordance with their approved rules, regulations, principles, and charters, if a historic landscape were of Outstanding Universal Values (OUV), it would be heritage-listed and enter the process of preserving and showcasing; otherwise, it would be subject to potential demolition and subsequent reconstruction. This approach to heritage has limitations and potentially can lead to counterproductive effects.

In the context of Geelong and specifically the subject case, the assessment of significance is based on the Burra Charter, namely The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance [

4] and its Practice Notes. Having undergone several amendments, this charter has shifted its focus from traditional fabric-centered approaches to adopting evolving concepts of heritage, dynamic economic or political conditions, and a wide array of distinct locales [

5]. However, its strong emphasis on intrinsic place values and a preservation-first mindset can potentially obstruct the progress of adaptive reuse and development initiatives, in addition to posing challenges in practical implementation.

However, its overreliance on the intrinsic values of places and focus on preservation still can potentially hinder the advancement of adaptive reuse or developmental projects, besides the challenges associated with its practical implementation [

6].

As such, the scenario in which historical materials are without assigned heritage significance is susceptible to memory and legacy loss, and the buildings are also subject to destruction, which is the opposite of sustainable frameworks. Following the more recent registered conventions and charters, other heritage dimensions have received recognition, and it is not merely monumental and grand tangible buildings but also intangible as a point of history that matters. In this term, current heritage approaches acknowledge both intangible and tangible, as physical landscapes cannot be separated from intangible immaterial people’s experiences [

7]. However, buildings like Dennys Lascelles wool store still have not gained the protection layer, and their future fate is trapped amidst debates.

The scenario in which buildings have attained heritage designation and acquired preservation has also prompted specific limitations. This value-based viewpoint of heritage, mostly through the lens of museumification approaches, objectifies historical materials and recognizes them as precious objects that should be preserved and curated carefully. These traditional views of heritagization provided by earlier conventions and charters have presumed heritage to be aesthetically pleasing static material, non-renewable, fragile, with innate values, and concerned with physical preservation [

8]. Smith [

9] (2006) critically called this viewpoint on approaching heritage ‘Authorised Heritage Discourse’ (AHD), Harrison [

10] called it ‘Official Heritage’, and Lesh [

11] called it the value-based model of conservation.

During the last two decades, Critical Heritage Studies (CHS) supporters have examined the range of cases and presented that AHD approach and the mere concentration on tangible aspects of heritage can elicit a myriad of shortcomings, such as (i) consumerist practices in which heritage and memory turn into sell point and industry, (ii) commodification and displacement (social and cultural evacuation of space as a result of gentrification and space cleansing) (iii) inequality and historical denialism, and (iv) hegemonic practices over minority groups during religious and ethnic conflicts by oppressing or empowering them, just to name a few [

12,

13,

14]) Another drawback, which stems from this tangible and objectified viewpoint ending up with strict physical preservation, is the condition of ignoring the economic pressure for resource development and urban growth in line with sustainability principles.

Parallel to the ever-changing world, the requirements of built environments and their societies keep inevitably transforming. Accordingly, the heritage definition, with its dynamic nature, is not exempt from this, and ‘Static government-endorsed definitions’ are not well-suited to such fluid circumstances [

15]. Heritage advocates in critical heritage studies believe the meaning of the past is constantly redefined in each present setting [

16]. (In critical views on AHD, heritage is not a past product to be discovered but rather a contemporary process and action [

9,

10,

17,

18]. In this term, the Faro Convention’s main suggestion is to challenge the conventional approach of heritage as a valuable asset to be preserved and to encourage viewing it as a resource to be actively utilized and exploited for various purposes [

15].

However, given the higher preservation status assigned to historic urban areas compared to other parts of the city, it is difficult to implement different strategies except those involving strict preservation [

19], and this results in unsustainability. Therefore, the two conventional scenarios for historical landscapes can potentially result in unsustainability. It must be noted that preserving buildings in their original state encompasses various issues and challenges like inadequate insulation, high embodied carbon, water inefficiency, environmental degradation, and limited adaptability, to name a few. As such, recent studies on curated decay, toxic substances, urban mining, and the circular economy (CE) have brought forth pivotal viewpoints regarding alternative prospects for built heritage. In this manner, waste management and material reuse practices are starting to challenge the conventional notions of heritage that categorize elements of the built environment as either ‘value-bearing’ or ‘of no value’ and encourage a more inclusive and holistic approach to heritage management [

20].

In this term, if we shift from the long-lasting traditional paradigm that development undermines conservation and recognize that the transformative potentials of historical spaces can be consistent with heritage preservation, their future fate can be aligned with the sustainable ethics of not generating waste and heritage decay can be mitigated [

21,

22]. Also, there has been a rising interest in exploring methods for design revolving around the reuse of reclaimed materials due to the magnitude of waste produced from demolition activities, resource scarcity, and landfill burden [

20]. Adaptive heritage reuse not only ensures the preservation of our historical landscapes but also adapts them to meet the requirements of the present by fostering socially inclusive environments, driving economic growth, and promoting environmental sustainability within cities [

11].

In the meantime, this modification process of making useful responses for the current purpose of buildings can also sacrifice aspects of their historical significance. This can be resolved by recognizing and representing the plurality of heritage narratives through innovative heritage approaches like digital heritage. So, this paper intends to bring affect theory as an additional complementary attribute for heritage preservation besides digital theory as a tool to augment the range of choices for preserving various aspects of heritage. This can be applied in the situation of being left with no option other than modifying and removing a part of the heritage in conditions with irresolvable issues like safety concerns, heat waste, unsustainability, etc., as the ultimate goal is to make the building functional.

4.2. Circular City-Recycling, Reuse and Repurpose

A circular city embraces the principles of the circular economy throughout its urban landscape, forming sustainable systems that optimize resources and eliminate waste. These cities foster local economies by extending product life, reusing, refurbishing, remanufacturing, and recycling while transitioning from linear to circular models. Collaboration across diverse aspects, including humans, businesses, systems, and infrastructure, drives this transformation. In the circular economy, materials circulate without waste, creating resilient and inclusive urban spaces that benefit all residents. The circular city is closely connected with the circular economy, a closed-loop system that uses waste as a resource. As Foster [

23] states:

‘Circular Economy is a production and consumption process that requires the minimum overall natural resource extraction and environmental impact by extending the use of materials and reducing the consumption and waste of materials and energy. The useful life of materials is extended through transformation into new products, design for longevity, waste minimization, and recovery/reuse, and redefining consumption to include sharing and services provision instead of individual ownership. A CE emphasizes the use of renewable, non-toxic, and biodegradable materials with the lowest possible life-cycle impacts. As a sustainability concept, a CE must be embedded in a social structure that promotes human well-being for all within the biophysical limits of the planet Earth.’

Hence, the existing building stocks, whether historic, partially demolished, or heritage, are considered resources for a circular city. Considering the city of Geelong as a case, where the city and its surroundings are changing as large businesses close and are replaced by luxury residences, hotels, and new office buildings, among other things. As a result, the once-industrial town and its associated architecture are quickly fading from city dwellers’ memories. As a result of development, the disappearance of visible and intangible memories raises concerns about voids or untold histories in the city’s industrial past and heritage. While much of Geelong’s CBD is being reshaped for the twenty-first century with new buildings, refurbished structures, alleyways, and new activities, certain areas of the CBD continue to be gaps/voids with empty, abandoned buildings, dark alleys, and vacant lots. In this context, a circular economy could be used as a strategy to mitigate this consumption by preserving and reusing historic buildings rather than demolishing and rebuilding them.

Heritage economics examines cultural heritage assets as integral components of a city’s cultural capital within the context of urban conservation. In such contexts, a heritage asset is perceived as more than an entity possessing mere economic value; it encapsulates cultural significance. This amalgamation of cultural and economic value imparts enduring worth over time, generating a continuum of services, consumable or utilizable in the production of additional goods and services [

24].

When we aim to match old historical assets with new needs and uses, the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage often requires significant interventions [

25,

26]. Thoughtful use of materials and people to take care of, maintain, and make use of heritage assets creates a lasting flow of valuable things and services. This makes adaptive reuse a meaningful part of the creative economy. As stated by Ost [

27].

‘Heritage conservation is the economic process of providing and investing additional resources in cultural capital to keep it generating cultural and economic values in the future.’

In the context of Geelong, the fate of industrial vacancies predominantly ends in abandoned sites waiting to be demolished or transformed if not listed as heritage. However, as architecture, these buildings are the only tangible evidence, the paramount query that reminiscences the historic narrative of the city and the place. Certainly, the importance of preserving historic buildings to maintain their historical, aesthetic, and architectural value is widely recognized.

One approach to preserving these values is by skillfully using the existing structure of the buildings. This means restoring, recycling, and repurposing old buildings while also safeguarding their unique architectural features and traditional methods that make them environmentally sustainable. However, this presents a challenge in two directions.

Firstly, if a building is considered a heritage site and protected by certain regulations (AHD), how can we make changes to it without losing its historical significance? Especially when we need to adapt it to new functions and roles in a fast-changing world. Sometimes, this even requires changing the infrastructure around the building to suit its new purpose.

On the other hand, if the building is not officially recognized as a heritage site, how can we keep the intangible historical and urban values it holds, whether we decide to tear it down or completely renovate it to match today’s needs? This is a challenge we are grappling with right now. In our case, the core of this issue revolves around the Denny Lascelles wool store. The portion with heritage status was completely demolished, while the remaining part is not officially recognized as heritage and is seemingly viewed as a basic abandoned structure, open to demolition and reconstruction, as we explained at the beginning of this paper.

In a previous study [

28], the team tried to uncover and revive the story of the missing section using digital tools. Now, in this paper, we are further investigating the potential of today’s digital tools and the concept of ‘affective heritage.’ We are doing this within the context of a circular city, aiming to safeguard the city’s architecture and cultural capital.

4.3. Affect and Heritage

‘Adaptive reuse’ prioritizes new purposes over conserving original heritage, especially when defined by the ‘authorised heritage discourse’ (AHD). We explore how a broader heritage definition can overcome AHD limitations while preserving historical value. This paper introduces ‘affective heritagisation,’ where existing building value mediates between program needs and heritage, fostering a symbiotic relationship between architecture and history.

According to David Lowenthal, heritage is a celebratory aspect of history, not an in-depth investigation. Our Geelong ‘Wool Store Precinct’ subtly celebrates the wool industry, avoiding ‘heritagization’ and ‘commodification’ [

29,

30]. Carman [

31], an archaeologist, explains heritage’s emergence from categorization, influenced by curatorial agendas, which Denny Lascelles does not fit with.

Tolia-Kelly et al. [

32] state heritage engagements are primarily emotional responses to triggers like pain, joy, nostalgia, and belonging. Zeisel [

33] underscores understanding human perception for appropriate built environment design, beneficial for heritage maintenance on the Denny Lascelles Wool store and similar projects.

‘Heritagisation,’ a term from the late 20th Century, transforms history into exhibits for cultural tourists. Fluid definitions challenge this concept and the dominant ‘authorised heritage discourse’ [

34]. ‘Heritagisation’ is a dynamic process, evolving based on research, discourse, cultural values, and various group involvement [

35].

‘Affect Theory’ explains how experiences impact us physically and mentally. Tolia-Kelly et al. [

32] note heritage engagements are primarily emotional responses. Fielding [

36] expands this beyond emotions, involving mundane interactions, information, and others’ reactions, affecting perception. For Fielding, affect theory in heritage is more than emotional manipulation; it is about how understanding and reacting to the past impact present life. Affective heritagization suggests heritage through materiality, space, culture, and history.

Adaptive reuse of historical buildings prioritizes new programs over heritage preservation, sparking tension between conflicting priorities, especially within the ‘authorised heritage discourse’. This discourse perceives heritage as ‘material, non-renewable, and fragile’. To reconcile these concerns, the concept of ‘affective heritagization’ emerges, recognizing the active role of existing structures in balancing programmatic needs and heritage significance. Focusing on the Dennys Lascelles Wool store, this research highlights the importance of ‘historic narrative’ in crafting a meaningful heritage experience.

Memory encompasses information storage and recall, while nostalgia triggers emotional responses from physical and non-physical cues. Despite negative connotations, nostalgia can deepen engagement with history. For successful adaptive reuse and experience-centered architecture, emotions like nostalgia must be understood.

The Dennys Lascelles Wool store offers a model for heritage projects that emphasize the spatial and textural facets of the original structure, foregoing ‘heritagization’ and ‘commodification.’ This approach prioritizes an effective architectural experience, redirecting public learning towards emotional heritage understanding.

Heritage discourse has evolved into dynamic understandings, with affect theory exploring how experiences impact us. Affective heritagization proposes heritage through emotional triggers, fostering personal engagements. Ultimately, heritage emerges from interactions with material culture, shaping current social and political narratives. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

5. Discussion: Digital Heritage and Affective Preservation

This study critically explores the potential of digital technology to address ‘affective heritage,’ which simultaneously preserves building memories and repurposes them within the context of the circular economy. Grounded in the notion that architecture offers insights into human nature, values, and culture [

37], the project employs digital tools to meticulously reconstruct Geelong’s wool industry history for widespread dissemination. The concept of ‘Virtual heritage’ enables non-invasive monument restoration through immersive multimedia experiences [

38], effectively benefiting conservators, historians, archaeologists, and urban designers by ensuring the preservation of historical buildings within the principles of the circular economy. While 3D models considerably aid in the restoration process, capturing intangible values remains a notable challenge for architectural historians.

The study takes a comprehensive approach by effectively integrating digital technologies to capture both tangible and intangible memories. Understanding a building’s significance within the present context but devoid of traditional interactions poses a unique challenge [

39]. Although architecture inherently encapsulates collective memories, the process of engagement with them can be intricate and nuanced [

40]. The study itself revolves around the concept of ‘Affective Heritage’, which seeks to broaden heritage understanding by meticulously examining historic structures to holistically capture human experiences. The ultimate goal of the endeavor is to bridge temporal gaps, enabling present-day individuals to form a profound connection with the past, thereby shaping collective memory and fostering cultural preservation.

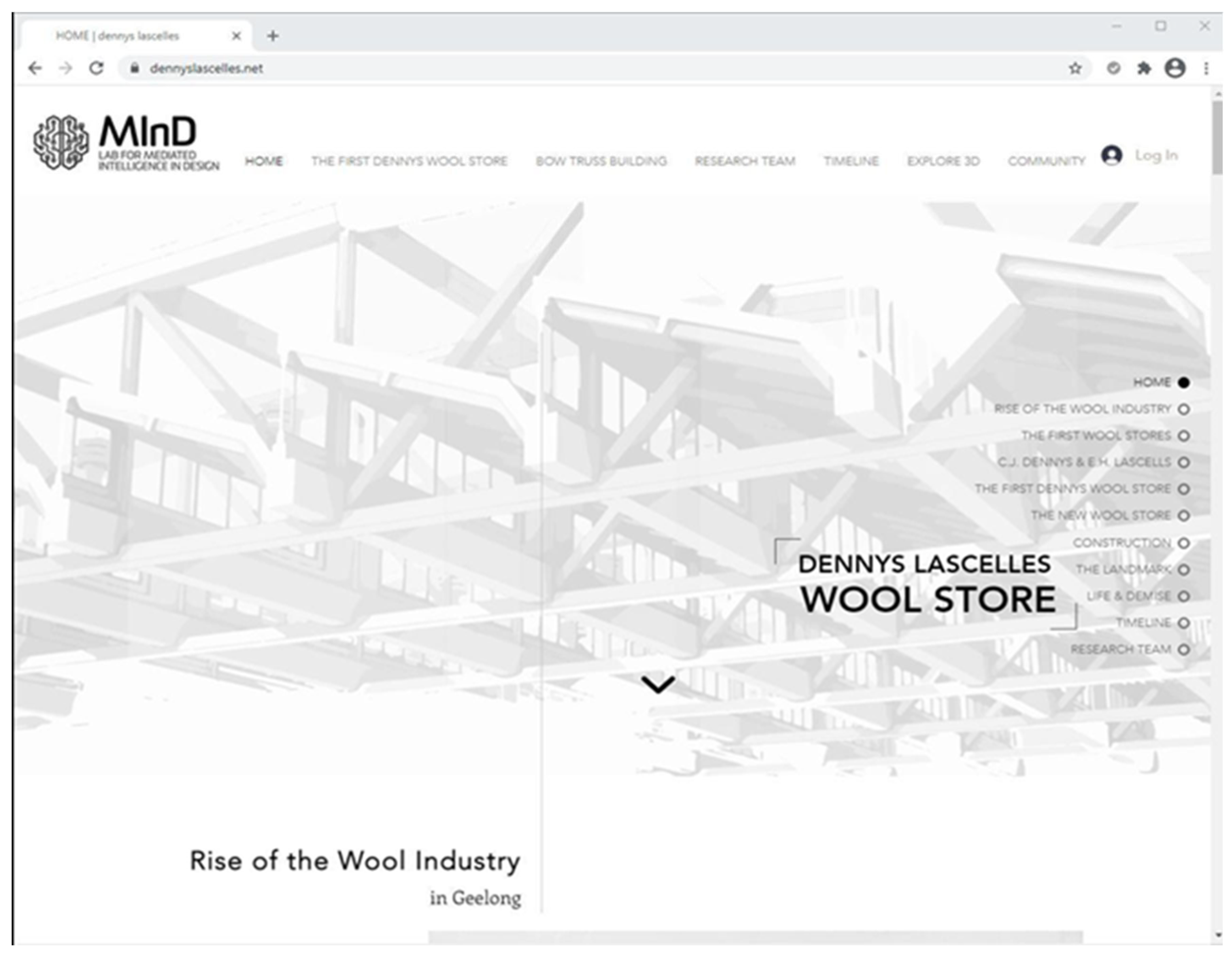

The study takes a critical stance by investigating the challenges surrounding the reconstruction of the lost architectural narrative of the Bow truss building, the primary structure within the Dennys Lascelles Wool Store complex. Despite the building’s heritage listing, it faced demolition, thereby disconnecting current citizens of the city of Geelong from its original architecture and historical significance as an initial study proposed a virtual diachronic model of the building, which views architecture as a dynamic process [

41] and employs a linked open database to meticulously reconstruct the historical trajectory of the site. This approach effectively bridges the gap between the tangible and intangible aspects of heritage. The project is carried out through five distinct stages: data collection, identification of historical narratives, creation of a digital model, development of a user-friendly storyboard, and dissemination of findings via an interactive website (

Figure 3) [

28].

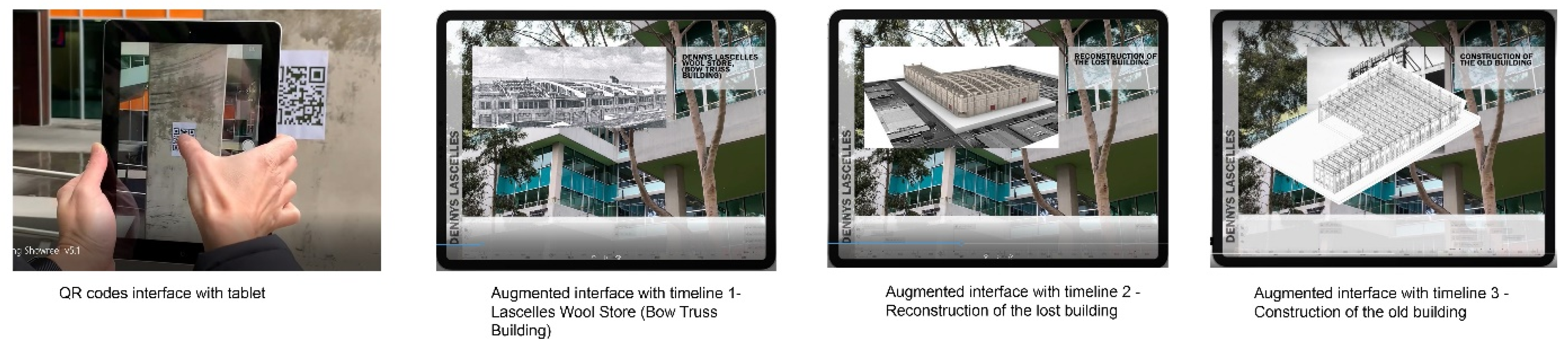

The first part of the study conclusively affirms the pivotal role that architecture and digital tools play in effectively preserving heritage while ensuring public engagement. The introduction of an Augmented Reality (AR) experiment utilizing QR codes for virtual walking tours is particularly noteworthy (

Figure 4). The study’s limited surveys yielded positive responses, which significantly underscore AR’s potential for engaging users with historical spaces [

28]. The project’s ongoing innovation revolves around the intricately intertwined narratives, promoting an inclusive heritage experience that actively involves the community. As technology continues to advance rapidly, the study envisions a future where architectural interfaces play an instrumental role in disseminating heritage while promoting engagement with architecture.

The ongoing reactivation project unveils a novel narrative, intricately weaving an inclusive heritage experience accessible through a user-friendly interface. This fusion of narratives offers an immersive journey that rekindles cultural memories via spatial and non-linear storytelling, thus infusing heritage with enduring ‘Affect’. Concurrently, the project envisions repurposing buildings to align with circular economy principles. Amidst the rapid evolution of digital technology, the paper posits that the realm of ‘affective heritage’ holds the key to engaging with vanished structures and bygone eras. This approach stands not in contrast but rather in tandem with physical preservation endeavors, broadening the horizons of heritage conservation and dissemination, ensuring a sustainable circular future.

The team is also delving into more effective digital tools to capture historic buildings like ‘Digital Twin’. Dezen-Kempter et al. [

42] have observed that the application of Digital Twins (DT) in Heritage involves creating intelligent 3D models (HBIM) that manage and enhance information accessibility. According to Nagakura and Woong-ki [

43], digital historical models aid in building investigations cost-effectively, unlike physical artifacts stored in labs or museums. Technologies like photogrammetry and 3D laser scanning efficiently generate these models [

44]. Augmented Reality (AR) further aids interaction with these models, enhancing understanding and social engagement [

45]. In the future, the study will anticipate exploring combining the Digital Twin with the Human-Building Interaction (HBI) through architectural interfaces and augmented digital content, drawing parallels to prior instances such as the BIX façade and the tower of winds media façade. Foreseeing forthcoming technological strides and the evolving landscape of human-computer interaction (HCI), the study envisions historic building façades or interior walls as conduits for disseminating the building’s historical essence, enriching user engagement sans the reliance on mobile devices and augmented technology. Khoo et al. [

46] demonstrate the potential of integrating mobile spherical robots and projected digital visual contents as architectural interfaces for the existing built environment. In addition, as current artificial intelligence (AI) technologies continue to evolve, their integration into HBI and digital heritage preservation has given the opportunity to intelligent, adaptive, and responsive building interfaces that optimize human experience, history, and culture in digital heritage. This development with AI also enables multi-modal HBIs, including voice, gesture, and touch-based controls that offer more intuitive and flexible ways for users to interact with the digital heritage superimposed on the physical built environment to enhance the user experience and knowledge [

47]. The ever-evolving digital landscape with current AI technologies potentially ensures a multifaceted understanding of heritage, effectively guaranteeing its continuity within a sustainable and circular future. The project’s findings and the anticipated future developments underscore the remarkable potential of affective heritage in reshaping heritage preservation and dissemination.

With the ever-changing digital world, we can better understand and keep heritage alive, ensuring it continues into the future. This project’s discoveries and upcoming changes show that effective heritage, using digital tools, can play a big role in preserving and sharing heritage. In the end, this way of thinking suggests that affective heritage, using digital technology, could be a guide for protecting heritage in contemporary circular cities. This modern perspective combines technology, history, and how people connect to create a story where heritage not only survives but also thrives, adapting to the present while holding onto its cultural roots.

6. Positioned Conclusions: Reimagining Heritage Through Affect, Digitality, and Circular Practice

The evolving trajectory of Geelong’s Dennys Lascelles Wool Store exemplifies a critical moment in the discourse on industrial heritage—where preservation must contend with the realities of urban transformation, community effect, and ecological responsibility. As demonstrated throughout this paper, traditional heritage models, anchored in static material preservation, are increasingly inadequate in addressing the tensions between conservation and the need for adaptive reuse within a rapidly developing cityscape.

This research positions affective heritagization, amplified through digital technologies and framed within a circular economy, as a necessary evolution in heritage thinking. The emotional and sensory bonds that communities hold with places like the Wool Store are not peripheral but foundational to heritage value. These affective connections, when captured and reanimated through immersive technologies, offer an alternative to the binary of physical preservation or loss.

Through stakeholder engagement, site-based inquiry, and digital mediation, this study illustrates that heritage can thrive in forms that are adaptive, experiential, and sustainable. The loss of the iconic bow truss structure is emblematic of the challenges faced by many industrial sites; however, its digital re-presence through virtual reconstructions, 3D modeling, and augmented experiences becomes a vital means of restoring its narrative and presence within collective memory.

Moreover, the application of emerging AI technologies promises to extend the possibilities of digital heritage even further—enhancing realism, refining storytelling, and tailoring heritage interactions to diverse audiences. This enables a more democratic and accessible engagement with the past, especially for marginalized or less visible heritages.

In parallel, circular economy principles offer a pragmatic and forward-thinking approach to the adaptive reuse of the remaining structures. These strategies prioritize resource efficiency, programmatic flexibility, and community-centered design—ensuring that heritage sites are not frozen in time, but integrated meaningfully into the living, evolving fabric of the city.

We argue that the Dennys Lascelles Wool Store should not be seen as a symbol of heritage loss, but as a proving ground for a new model of heritage conservation: one that is deeply emotional, technologically enriched, and fundamentally sustainable. In doing so, we advocate for a future in which the past is not only remembered but regenerated, where urban development and memory are not in opposition, but in dialogue.

This is not just a local story—it is a call for heritage practices globally to reorient toward inclusion, innovation, and regeneration. Through effective digital heritage and circular thinking, we move beyond preservation-as-freeze toward preservation-as-continuity—bridging histories with futures, and memory with imagination.