Digital Storytelling in Cultural and Heritage Tourism: A Review of Social Media Integration and Youth Engagement Frameworks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

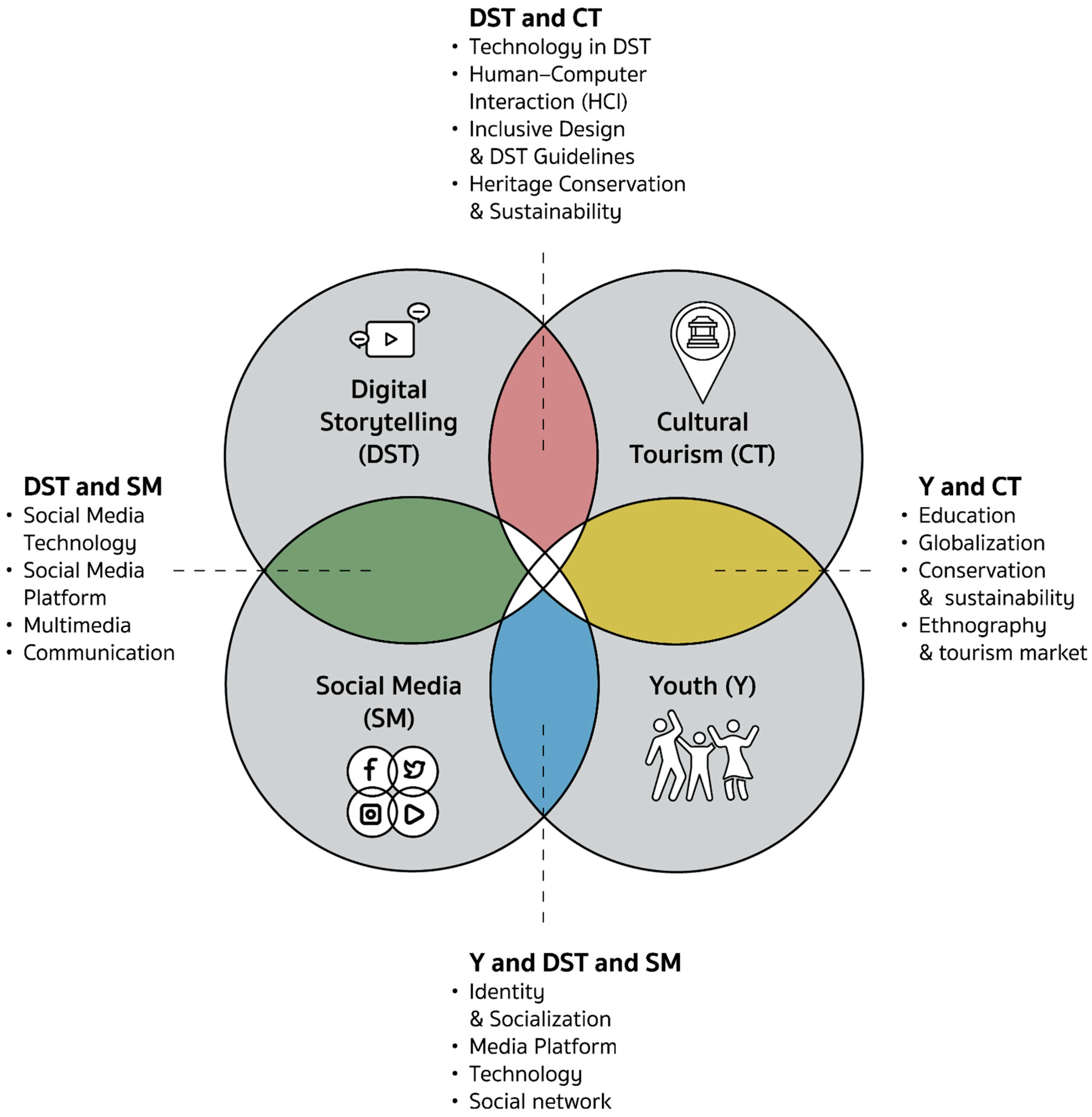

3. Results

3.1. Digital Storytelling (DST) and Cultural Tourism (CT)

3.1.1. Cluster 1: Technology in Digital Storytelling

3.1.2. Cluster 2: Human–Computer Interaction

3.1.3. Cluster 3: Inclusive Design and Digital Storytelling Guidelines

3.1.4. Cluster 4: Digital Storytelling Guidelines

3.2. Digital Storytelling (DST) and Social Media (SM)

3.2.1. Cluster 1: Social Media Feature Trends

3.2.2. Cluster 2: Social Media Platforms

3.2.3. Cluster 3: Multimedia

3.2.4. Cluster 4: Communication

3.3. Youth and Cultural Tourism (CT)

3.3.1. Cluster 1: Education

3.3.2. Cluster 2: Globalization

3.3.3. Cluster 3: Conservation and Sustainability

3.3.4. Cluster 4: Ethnography, Tourism Market

3.4. Youth and Digital Storytelling (DST) and Social Media (SM)

3.4.1. Cluster 1: Self-Esteem, Identity, and Socialization

3.4.2. Cluster 2: Social Media Platform and Content

3.4.3. Cluster 3: Digital Engagement Technology

3.4.4. Cluster 4: Social Networks

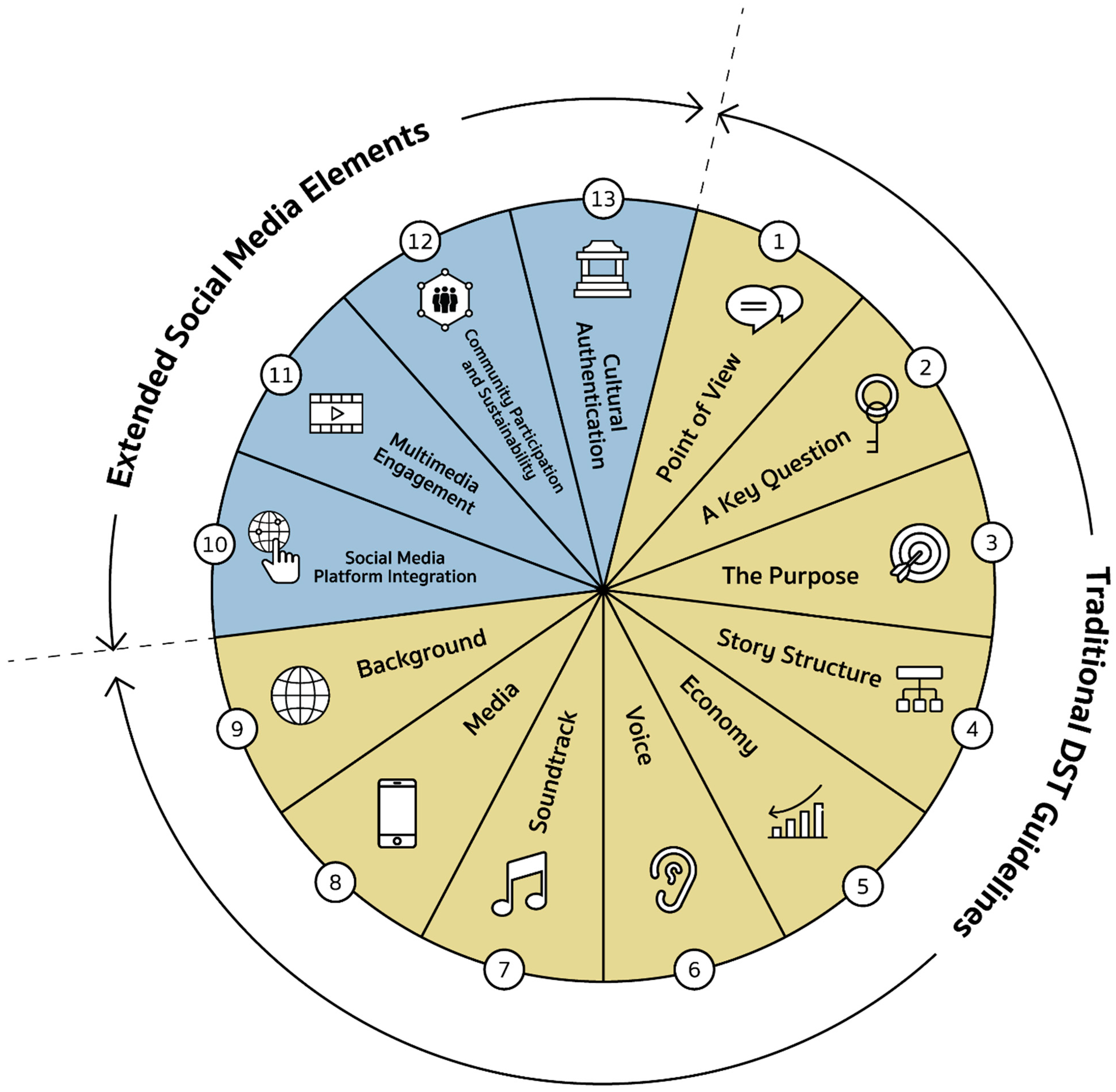

4. Developing the IDSM Framework by Extending Traditional Guidelines Utilizing Contemporary Social Media Elements

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.1.1. Cultural Tourism/Tourism Industry

5.1.2. Research/Education

5.1.3. Media Designers and Digital Content Creators

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boc, E.; Filimon, A.L.; Mancia, M.S.; Mancia, C.A.; Josan, I.; Herman, M.L.; Filimon, A.C.; Herman, G.V. Tourism and Cultural Heritage in Beiuș Land, Romania. Heritage 2022, 5, 1734–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Shen, Z.; Teng, X.; Mao, Q. Cultural routes as cultural tourism products for heritage conservation and regional development: A systematic review. Heritage 2024, 7, 2399–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomadaki, O.I.; Dimoulas, C.A.; Kalliris, G.M.; Paschalidis, G. Digital storytelling and audience engagement in cultural heritage management: A collaborative model based on the Digital City of Thessaloniki. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 36, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpracha, B.; Kasemsarn, K.; Patcharawit, K.; Mungkornwong, K.; Sumthumpruek, A. A Conceptual Framework and Website Design for Promoting Cultural Tourism in Kalasin Province for Travelers Using Big Bikes. J. Mekong Soc. 2024, 20, 158–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cesário, V. Guidelines for combining storytelling and gamification: Which features would teenagers desire to have a more enjoyable museum experience? In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kasemsarn, K. Applying classic literature to facilitate cultural heritage tourism for youth through multimedia e-book. Heritage 2024, 7, 5148–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, N.F.; Cohen, S.A.; Scarles, C. The power of social media storytelling in destination branding. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Illera, J.L.; Barberà Gregori, E.; Molas-Castells, N. Reasons and mediators in the development and communication of personal digital stories. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 4093–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Hurtado, M.J.; Fuertes-Alpiste, M.; Martínez-Olmo, F.; Quintana, J. Youths’ posting practices on social media for digital storytelling. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.; Hessler, B. Digital Storytelling Capturing Lives, Creating Community; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.H. Digital Storytelling 4e: A Creator’s Guide to Interactive Entertainment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cunsolo Willox, A.; Harper, S.L.; Edge, V.L.; ‘My Word’: Storytelling and Digital Media Lab; Rigolet Inuit Community Government. Storytelling in a digital age: Digital storytelling as an emerging narrative method for preserving and promoting indigenous oral wisdom. Qual. Res. 2013, 13, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, A.M.; Mc Guckin, C. The Systematic Literature Review Method: Trials and Tribulations of Electronic Database Searching at Doctoral Level; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W-65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.E.; da Silva, V.L.; de Souza, S.J.; de Souza, G.A. A tool for integrating genetic and mass spectrometry-based peptide data: Proteogenomics Viewer: PV: A genome browser-like tool, which includes MS data visualization and peptide identification parameters. Bioessays 2017, 39, 1700015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Sawadsri, A.; Harrison, D.; Nickpour, F. Museums for Older Adults and Mobility-Impaired People: Applying Inclusive Design Principles and Digital Storytelling Guidelines—A Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 1893–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katifori, A.; Tsitou, F.; Pichou, M.; Kourtis, V.; Papoulias, E.; Ioannidis, Y.; Roussou, M. Exploring the potential of visually-rich animated digital storytelling for cultural heritage: The mobile experience of the Athens university history museum. In Visual Computing for Cultural Heritage; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 325–345. [Google Scholar]

- Tzima, S.; Styliaras, G.; Bassounas, A.; Tzima, M. Harnessing the potential of storytelling and mobile technology in intangible cultural heritage: A case study in early childhood education in sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinam, M.; Ciotoli, L.; Koceva, F.; Torre, I. Digital storytelling in a museum application using the web of things. In Proceedings of the Interactive Storytelling: 13th International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2020, Bournemouth, UK, 3–6 November 2020; Proceedings 13. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Surapiyawong, P.; Kasemsarn, K. Mobile application of local Baba-Peranakan food tourism for generation Y: A case study of Phuket province, Thailand. J. Mekong Soc. 2024, 20, 101–130. [Google Scholar]

- Vrettakis, E.; Katifori, A.; Ioannidis, Y. Digital storytelling and social interaction in cultural heritage-an approach for sites with reduced connectivity. In Proceedings of the Interactive Storytelling: 14th International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2021, Tallinn, Estonia, 7–10 December 2021; Proceedings 14. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulos, G.; Alexandridis, G.; Caridakis, G. A survey on computational and emergent digital storytelling. Heritage 2023, 6, 1227–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, M.; Nisi, V. Leveraging Transmedia storytelling to engage tourists in the understanding of the destination’s local heritage. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 34813–34841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuran, C.; Salim, F.A.; Ying, X. Enhancing Cultural Heritage Tourism through Market Innovation and Technology Integration. In Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture; De Gruyter Brill: Boston, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kontiza, K.; Antoniou, A.; Daif, A.; Reboreda-Morillo, S.; Bassani, M.; González-Soutelo, S.; Lykourentzou, I.; Jones, C.E.; Padfield, J.; López-Nores, M. On how technology-powered storytelling can contribute to cultural heritage sustainability across multiple venues—Evidence from the CrossCult H2020 project. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaturk, T.; Mazza, D.; McKinnon, M.; Kaljevic, S. GDOM: An Immersive Experience of Intangible Heritage through Spatial Storytelling. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2023, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvic, S.; Boskovic, D.; Mijatovic, B. Advanced interactive digital storytelling in digital heritage applications. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2024, 33, e00334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.R.; Dorsch, L.L.P.; Figueiredo, M. Digital tourism: An alternative view on cultural intangible heritage and sustainability in Tavira, Portugal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podara, A.; Matsiola, M.; Kotsakis, R.; Maniou, T.A.; Kalliris, G. Generation Z’s screen culture: Understanding younger users’ behaviour in the television streaming age–The case of post-crisis Greece. Crit. Stud. Telev. 2021, 16, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiongli, W. Commercialization of digital storytelling: An integrated approach for cultural tourism, the Beijing Olympics and wireless VAS. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2006, 9, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Oliva, A.; Alvarado-Uribe, J.; Parra-Meroño, M.C.; Jara, A.J. Transforming communication channels to the co-creation and diffusion of intangible heritage in smart tourism destination: Creation and testing in ceutí (spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabellone, F. Development of an Immersive VR Experience Using Integrated Survey Technologies and Hybrid Scenarios. Heritage 2023, 6, 1169–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paolis, L.T.; Faggiano, F.; Gatto, C.; Barba, M.C.; De Luca, V. Immersive virtual reality for the fruition of ancient contexts: The case of the archaeological and Naturalistic Park of Santa Maria d’Agnano in Ostuni. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2022, 27, e00243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.; Reid, P.H. Digital storytelling and participatory local heritage through the creation of an online moving image archive: A case-study of Fraserburgh on Film. J. Doc. 2022, 78, 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.T.; Miranda, M. Storytelling as media literacy and intercultural dialogue in post-colonial societies. Media Commun. 2022, 10, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Nickpour, F. A conceptual framework for inclusive digital storytelling to increase diversity and motivation for cultural tourism in Thailand. In Universal Design 2016: Learning from the Past, Designing for the Future; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Ohler, J.B. Digital Storytelling in the Classroom: New Media Pathways to Literacy, Learning, and Creativity; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alcantud-Diaz, M.; Vayá, A.R.; Gregori-Signes, C. Share your experience. In Digital Storytelling in English for Tourism; Ibérica, Revista de la Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, L.; Eglinton, K.; Gubrium, A. Using digital stories to understand the lives of Alaska Native young people. Youth Soc. 2014, 46, 478–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B. Digitales: The Art of Telling Digital Stories; Bernajean Porter: Sedalia, CO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Salpeter, J. Telling Tales with Technology: Digital Storytelling Is a New Twist on the Ancient Art of the Oral Narrative. Technol. Learn. 2005, 25, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, B.R. Digital storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory Into Pract. 2008, 47, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, L. Investigations on Digital Storytelling: The Development of a Reference Model; VDM Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany; Müller: Ulm, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hausknecht, S. The role of new media in communicating and shaping older adult stories. In Proceedings of the Acceptance, Communication and Participation: 4th International Conference, ITAP 2018, Held as Part of HCI International 2018, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 478–491. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, N.; Fiebich, C. The elements of digital storytelling. Sch. Journal. Mass Commun. Inst. New Media Stud. Media Cent. Retrieved 2005, 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hajarian, M.; Bastanfard, A.; Mohammadzadeh, J.; Khalilian, M. A personalized gamification method for increasing user engagement in social networks. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2019, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtolina, S. A storytelling-driven framework for cultural heritage dissemination. Data Sci. Eng. 2016, 1, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelson, C.; Sheffield, A. Digital storytelling in a Web 2.0 world. In TCC; TCCHawaii: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2009; pp. 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H. Social-media-based knowledge sharing: A qualitative analysis of multiple cases. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. (IJKM) 2018, 14, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolino, E.M. User-Generated Content: Cultural Practices and Creativity in the Digital Era. In ESA Research Network Sociology of Culture Midterm Conference: Culture and the Making of Worlds; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, S.V. User-generated content about brands: Understanding its creators and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, M.E.; Macciò, M.; Raffini, L.; Striano, P.; Ramenghi, L.A. Enhancing public engagement through NICU storytelling on Facebook and Instagram: A case study from Gaslini Children’s Hospital. Front. Commun. 2024, 9, 1387733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibakhshi, R.; Srivastava, S.C. Post-story: Influence of introducing story feature on social media posts. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2022, 39, 573–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulou, A. (Small) stories as features on social media: Toward formatted storytelling. In The Routledge Companion to Narrative Theory; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, M.E.; Rajaram, D. Social Media Storytelling; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pettengill, J. Social media and digital storytelling for social good. J. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 9, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Lăzăroiu, G. The Social construction of participatory media technologies. Contemp. Read. Law Soc. Justice 2014, 6, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, M.; De Francisci Morales, G.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.S. Multimodal Engagement through a Transmedia Storytelling Project for Undergraduate Students. Gema Online J. Lang. Stud. 2020, 20, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubrium, A.; Turner, K.N. Digital storytelling as an emergent method for social research and practice. In Handbook of Emergent Technologies in Social Research; Academia: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 469–491. [Google Scholar]

- Tongsubanan, S.; Kasemsarn, K. Developing a design guideline for a user-friendly home energy-saving application that aligns with user-centered design (UCD) principles. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertiwi, E.; Sanusi, A.P. Storytelling in the Digital Age: Examining the Role and Effectiveness in Communication Strategies of Social Media Content Creators. Palakka Media Islam. Commun. 2023, 4, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, R.; Viglia, G. Exploring how video digital storytelling builds relationship experiences. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, T.R.; Nasution, B.; Nasution, F.; Harahap, A.N. Digital Narratives: The Evolution of Storytelling Techniques in the Age of Social Media. Int. J. Educ. Res. Excell. (IJERE) 2024, 3, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ma, Z.; Ma, R. Analyzing narrative contagion through digital storytelling in social media conversations: An AI-powered computational approach. New Media Soc. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Al Mahmud, A.; Liu, W. Digital storytelling intervention to enhance social connections and participation for people with mild cognitive impairment: A research protocol. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1217323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, N.; Henriksen, K.; Komodromos, M.; Tsagalas, D. Investigating digital storytelling for the creation of positively engaging digital content. EuroMed J. Bus. 2022, 17, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundby, K. Mediatized stories: Mediation perspectives on digital storytelling. New Media Soc. 2008, 10, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J.; McWilliam, K. Digital storytelling around the world. In Proceedings of the 27th National Informatics Conference; University of Southern Queensland: Toowoomba, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, C. Sustainable Development of Digital Cultural Heritage: A Hybrid Analysis of Crowdsourcing Projects Using fsQCA and System Dynamics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.; Skrocki, A.; Goebel, D.; Janes, K.; Locke, D.; Catalan, E.; Zanolini, W. Youth development travel programs: Facilitating engagement, deep experience, and “sparks” through self-relevance and stories. J. Leis. Res. 2024, 55, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortham, S. Youth cultures and education. Rev. Res. Educ. 2011, 35, vii–xi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukas, N. “Young faces in old places”: Perceptions of young cultural visitors for the archaeological site of Delphi. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 2, 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yan, F.; Fang, Q.; Si, W. Research on the Educational Tourism Development of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Suitability, Spatial Pattern, and Obstacle Factor. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachino, C.; Battisti, E.; Rovera, C.; Stylianou, I. Young travelers: Culture’s lovers and crowdfunding supporters. Manag. Res. Rev. 2024, 47, 1568–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchelli, V.; Octobre, S.; Cicchelli, V.; Octobre, S. An Alternative Globalization of Pop Culture. In The Sociology of Hallyu Pop Culture: Surfing the Korean Wave; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 75–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, K.; Yajima, H.; Islam, M.T.; Pan, S. Assessment of spawning habitat suitability for Amphidromous Ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis) in tidal Asahi River sections in Japan: Implications for conservation and restoration. River Res. Appl. 2024, 40, 1497–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahebwa, W.M.; Aporu, J.P.; Nyakaana, J.B. Bridging community livelihoods and cultural conservation through tourism: Case study of Kabaka heritage trail in Uganda. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 16, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaga, M.; Sopelana, A.; Gandini, A.; Aliaga, H.M.; Kalvet, T. Sustainable cultural tourism: Proposal for a comparative indicator-based framework in European destinations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Carlsen, J. The business of cultural heritage tourism: Critical success factors. J. Herit. Tour. 2010, 5, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnaru, G.I.; Niţă, V.; Melinte, C.; Anichiti, A.; Brînză, G. The nexus between sustainable behaviour of tourists from generation z and the factors that influence the protection of environmental quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, A.; Purbasari, N.; Damayanti, M.; Aprilia, N.; Astuti, W. Community-based rural tourism in inter-organizational collaboration: How does it work sustainably? Lessons learned from Nglanggeran Tourism Village, Gunungkidul Regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, M.; Kettunen, M.; Saarinen, J. Community inclusion in tourism development: Young people’s social innovation propositions for advancing sustainable tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2025, 50, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uduji, J.I.; Okolo-Obasi, E.N.; Asongu, S.A. Does CSR contribute to the development of rural young people in cultural tourism of sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence from the Niger Delta in Nigeria. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2019, 17, 725–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, L.; Mihalcea, R. Cross-cultural analysis of human values, morals, and biases in folk tales. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Association for Computational Linguistics: Singapore, 2023; pp. 5113–5125. [Google Scholar]

- Batat, W. The role of luxury gastronomy in culinary tourism: An ethnographic study of Michelin-Starred restaurants in France. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, H.; Baams, L.; Kretschmer, T. A Systematic Review of Social Media Use and Adolescent Identity Development. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2024, 10, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerario, A. The communication challenge in archaeological museums in Puglia: Insights into the contribution of social media and ICTs to small-scale institutions. Heritage 2023, 6, 4956–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, R.; Clark, L.S. Social media and connective journalism: The formation of counterpublics and youth civic participation. Journalism 2021, 22, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Ramos, A.; Torrecilla García, J.A.; Landa-Blanco, M.; Poleo Gutiérrez, F.J.; Castilla Mesa, M.T. Activism and social media: Youth participation and communication. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. Unleashing the potential of social media: Enhancing intercultural communication skills in the hospitality and tourism context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, R.E.; Hagen, I. Young adults’ perpetual contact, social connectivity, and social control through the Internet and mobile phones. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2010, 34, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirocchi, S. Generation Z, values, and media: From influencers to BeReal, between visibility and authenticity. Front. Sociol. 2024, 8, 1304093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echavarria, K.R.; Samaroudi, M.; Dibble, L.; Silverton, E.; Dixon, S. Creative experiences for engaging communities with cultural heritage through place-based narratives. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2022, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, S.; Mullett, J. Digital stories as a tool for health promotion and youth engagement. Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, e183–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffoul, A.; Ward, Z.J.; Santoso, M.; Kavanaugh, J.R.; Austin, S.B. Social media platforms generate billions of dollars in revenue from US youth: Findings from a simulated revenue model. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniesy, R.; Elshahawy, E.; Fakhreldin, H. Social media’s impact on the empowerment of women and youth male entrepreneurs in Egypt. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2022, 14, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serres, J. Online success as horizon of survival: Children and the digital economy in Lagos, Nigeria. Media Commun. 2023, 11, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J. Australian and Canadian Far-Right Extremism: A Cross-National Comparative Analysis of Social Media Mobilisation on Facebook. Ph.D. Dissertation, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Amsalem, D.; Martin, A.; Dixon, L.B.; Haim-Nachum, S. Using Instagram to Promote Youth Mental Health: Feasibility and Acceptability of a Brief Social Contact-Based Video Intervention to Reduce Depression Stigma; JAACAP Open: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Peer review studies in English | Non-English studies |

| Publication in the years 2010–2025 | Publications outside the time frame were not selected |

| Journals, conference proceedings, and textbooks | Working papers, book chapters, organization websites, and conference abstracts |

| Categories: business, management, and accounting; computers and composition; computers in human behavior; design studies; arts and humanities; social sciences; and multidisciplinary | Categories other than the ones selected were not included |

| DST and CT | DST and SM | Y and DST and SM | Y and CT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (red) | Cluster 1 (red) | Cluster 1 (red) | Cluster 1 (red) |

| Technology in digital storytelling, immersive, augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) | Social media technology | Self-esteem, identity, socialization | Education |

| Cluster 2 (green) | Cluster 2 (green) | Cluster 2 (green) | Cluster 2 (green) |

| Human–computer interaction (HCI) | Social media platform | Media platform | Globalization |

| Cluster 3 (blue) | Cluster 3 (blue) | Cluster 3 (blue) | Cluster 3 (blue) |

| Inclusive design, digital storytelling guidelines | Multimedia | Technology | Conservation, sustainability |

| Cluster 4 (yellow) | Cluster 4 (yellow) | Cluster 4 (yellow) | Cluster 4 (yellow) |

| Heritage conservation, sustainability | Communication | Social network | Ethnography, tourism market |

| Guidelines/Authors | Elements of Each Guideline | Category | Target | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Take six: Elements [41] | Living in your story, unfolding lessons learning, developing creative tension, economizing the story told, showing, not telling, and developing craftsmanship | General | General |

| 2. | The seven elements of digital storytelling [10] | A point of view, a dramatic question, emotional content, the gift of your voice, the power of the soundtrack, economy, and pacing | General | General |

| 3. | Six elements of digital storytelling [42] | Personal, begin with the story or script, concise, use readily available source materials, include universal story elements, and involve collaboration | General | General |

| 4. | Expanded and modified digital storytelling elements [43] | The overall purpose of the story, the narrator’s point of view, a dramatic question or questions, quality of the images, video and other multimedia elements, use of a meaningful audio soundtrack, the choice of content, pacing of the narrative, good grammar and language usage, economy of the story detail, and clarity of voice | Education | Teachers, students |

| 5. | Story elements [38] | Point of view, emotional engagement, tone, spoken narrative, soundtrack music, role of video and performance, creativity and originality, time, and story length and economy | Education | Teachers, students |

| 6. | A ten-step development checklist for creating an interactive project [11] | Premise and purpose, audience and market, medium, platform and genre, narrative/gaming elements, user’s role and point of view, characters, structure and interface, fictional world and setting, user engagement, and overall look and sound | Interactive entertainment (games, applications, new technologies) | General |

| 7. | Dimension star: Models for digital storytelling and interactive narratives [44] | Concreteness, user contribution, coherence, continuity, (conceptual) structure, stage, virtuality, spatiality, control, interactivity, collaboration, and immersion | Interactive entertainment (games, applications, new technologies) | General |

| 8. | Digital storytelling guideline for older adults [45] | Story type, imagery process and choice, music and sound, and multimedia | Multimedia | Older adults |

| 9. | Five elements of digital storytelling [46] | Media, action, relationship, context, and communication | Journalism | General |

| 10. | Inclusive digital storytelling guideline [17,37] | The storyteller’s point of view, a key question, the purpose, story structure, economy, the storyteller’s voice, soundtrack, media, and background | Museum presentation | Youth, older adults, disabled people |

| Factors | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1. The storyteller’s point of view | What is the main point of the story, and what is the perspective of the author? |

| 2. A key question | A key question that keeps the viewer’s attention and will be answered by the end of the story |

| 3. The purpose | Establish a purpose early on and maintain a clear focus throughout |

| 4. Story structure | What are the major events or challenges during the narrative? |

| 5. Economy | Using just enough content to tell the story without overloading the viewer |

| 6. The storyteller’s voice | Storyteller gives the narrative the appropriate amount of focus in their story |

| 7. Soundtrack | Music or other sounds that support and embellish the story |

| 8. Media | What is the media (e.g., mobile phones, TV, or the Internet)? |

| 9. Background | What is the world, and where is it set? |

| Factors | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. The storyteller’s point of view | What is the main point of the story, and what is the perspective of the author? | [17,37] |

| 2. A key question | A key question that keeps the viewer’s attention and will be answered by the end of the story. | |

| 3. The purpose | Establish a purpose early on and maintain a clear focus throughout. | |

| 4. Story structure | What are the major events or challenges during the narrative? | |

| 5. Economy | Using just enough content to tell the story without overloading the viewer. | |

| 6. Voice | Storyteller gives the narrative the appropriate amount of focus in their story. | |

| 7. Soundtrack | Music or other sounds that support and embellish the story. | |

| 8. Media | What is the media (e.g., mobile phones, TV, or the Internet)? | |

| 9. Background | What is the world, and where is it set? | |

| 10. Social media platform integration | Integration of platform-specific social media features that facilitate interactive storytelling, authentic narrative sharing, and community engagement. Includes consideration of platform-specific characteristics, user-generated content mechanisms, and value-aligned messaging strategies that resonate with youth audiences. | [53,54,55,56,57,58,101] |

| 11. Multimedia engagement | Integration of diverse multimedia elements, including visual, interactive, and immersive technologies (VR/AR), to enhance engagement with cultural heritage content. | [18,25,30,48,49,61,62,64,65] |

| 12. Community participation and sustainability | Encompasses methodologies for co-created content development, community-driven storytelling, and collective cultural heritage preservation and sustainability, specifically designed to enhance youth engagement in cultural tourism contexts. | [9,32,71,90] |

| 13. Cultural authentication | Encompasses methodological frameworks for community validation, heritage preservation, and cultural context verification, specifically designed to maintain authenticity while engaging youth audiences through digital platforms. | [26,29,32,36,81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kasemsarn, K.; Nickpour, F. Digital Storytelling in Cultural and Heritage Tourism: A Review of Social Media Integration and Youth Engagement Frameworks. Heritage 2025, 8, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060200

Kasemsarn K, Nickpour F. Digital Storytelling in Cultural and Heritage Tourism: A Review of Social Media Integration and Youth Engagement Frameworks. Heritage. 2025; 8(6):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060200

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasemsarn, Kittichai, and Farnaz Nickpour. 2025. "Digital Storytelling in Cultural and Heritage Tourism: A Review of Social Media Integration and Youth Engagement Frameworks" Heritage 8, no. 6: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060200

APA StyleKasemsarn, K., & Nickpour, F. (2025). Digital Storytelling in Cultural and Heritage Tourism: A Review of Social Media Integration and Youth Engagement Frameworks. Heritage, 8(6), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060200