Organic Residue Analysis on Iron Age Ceramic Mugs (5th–1st Century BC) from Valle Camonica—UNESCO Site n. 94, Northern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Cultural Background

1.2. The Archaeological Context: The Sites of Provenance of the Samples

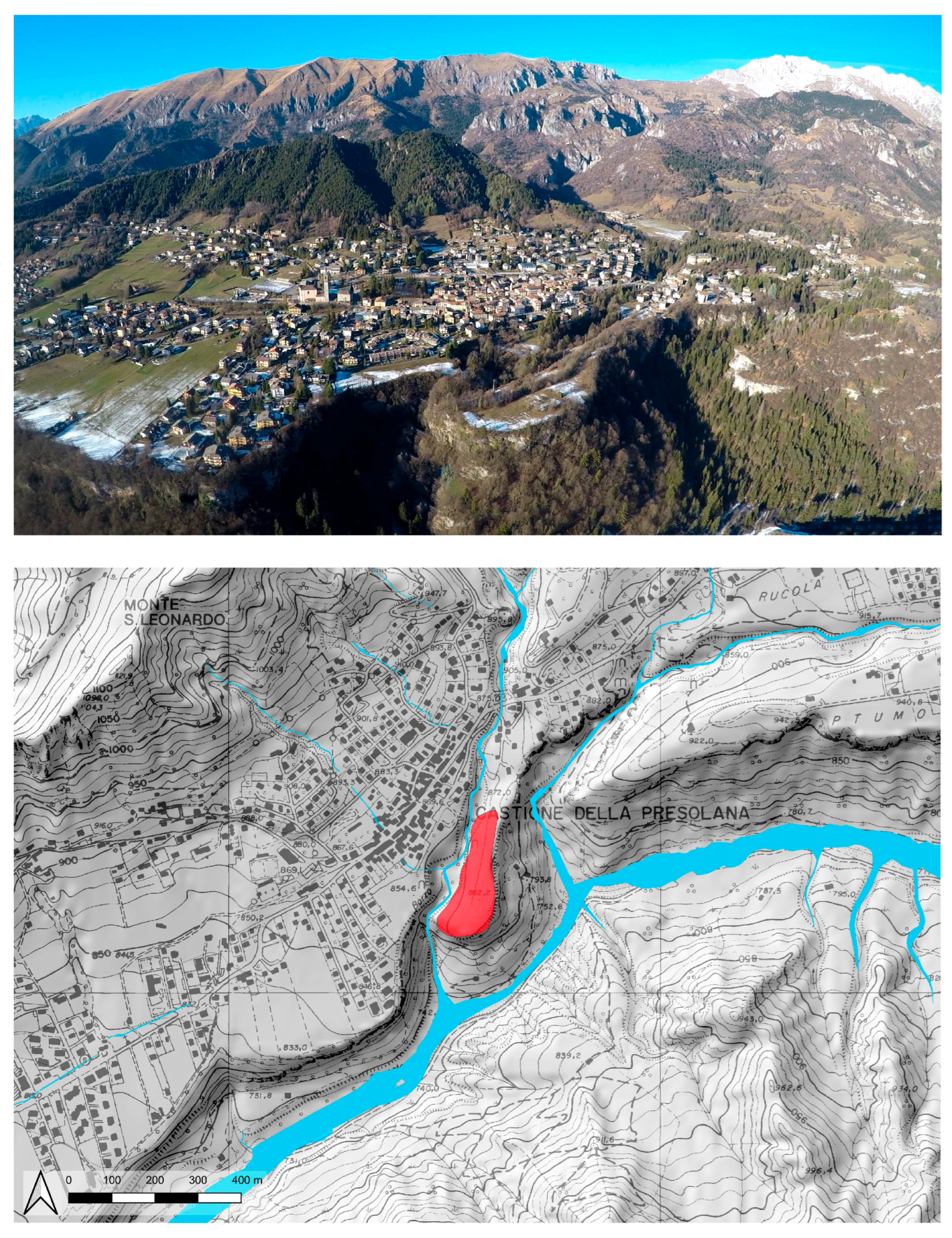

1.2.1. Dos dell’Arca

1.2.2. Castello di Castione della Presolana

2. Materials and Methods

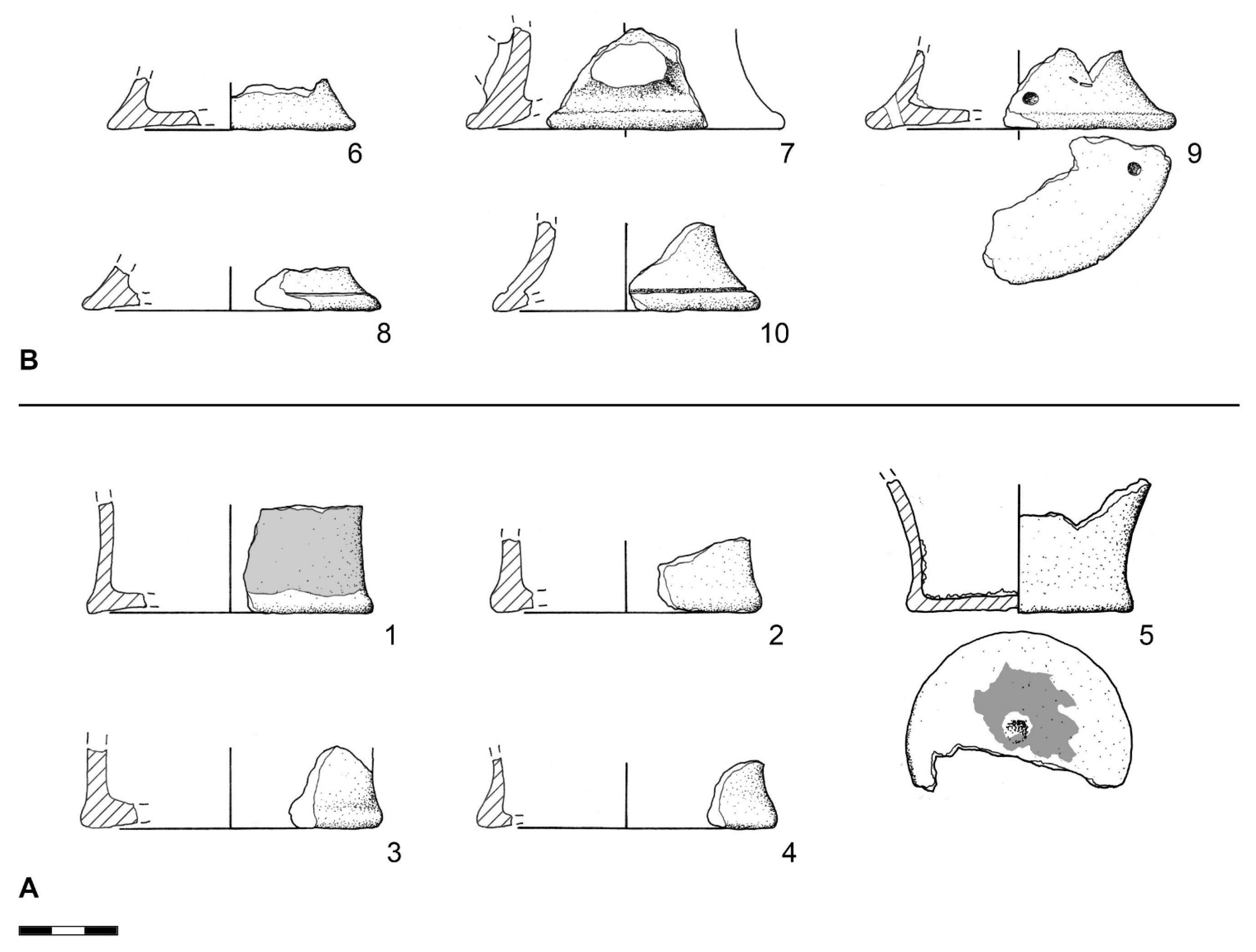

2.1. Description of Archaeological Samples

2.2. Organic Residue Analyses (ORA)

2.2.1. Extraction Protocol and Instrumentation for the Recovery of Lipid Fraction

2.2.2. Extraction Protocol and Instrumentation for the Recovery of Short-Chain Carboxylic Compounds

2.2.3. GC-C-IRMS Analyses

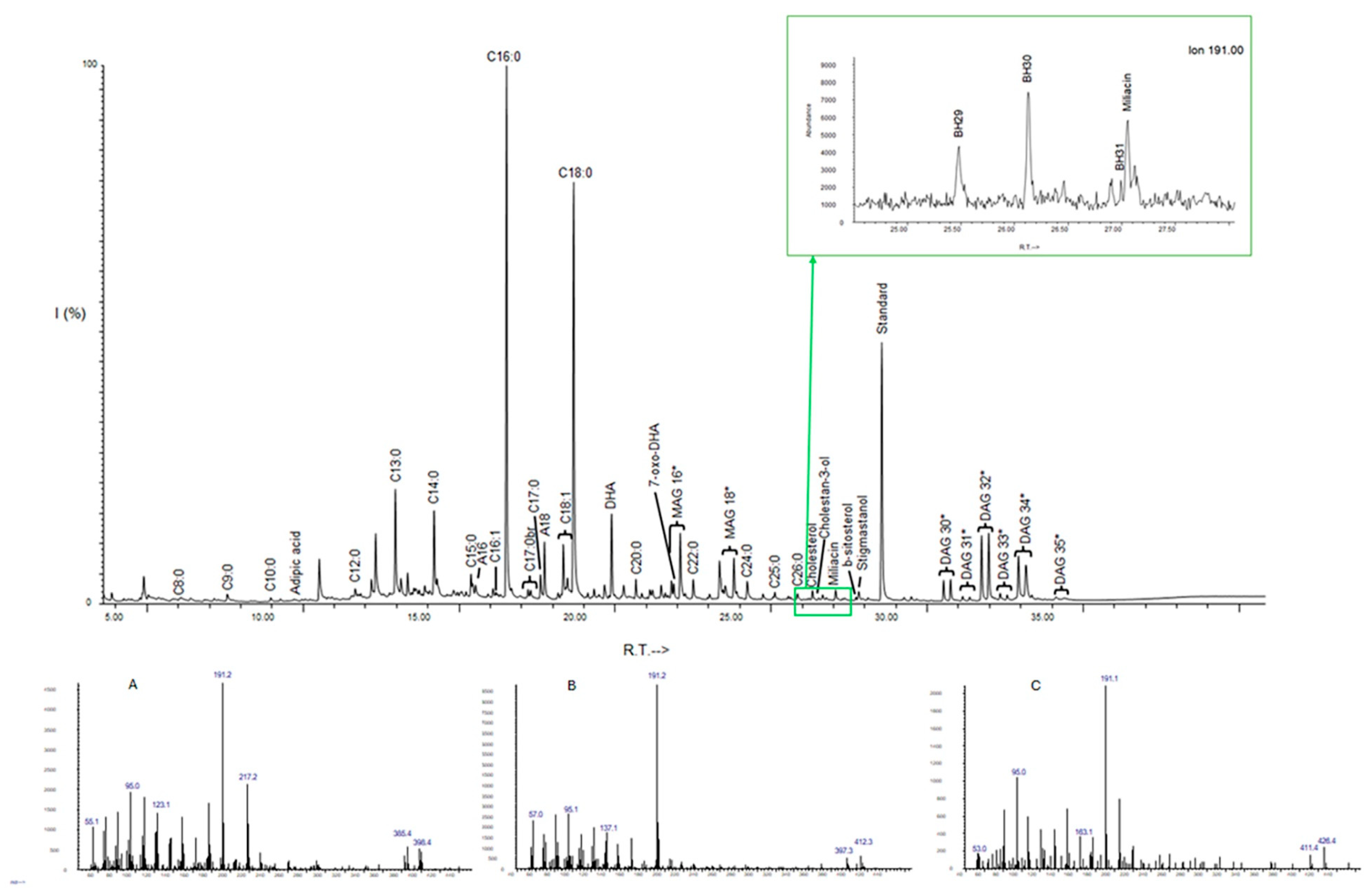

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Marinis, R.C. Preistoria e protostoria della Valcamonica, Valtrompia e Valsabbia. Aspetti della cultura materiale dal Neolitico all’età del Ferro. In Valtellina e Mondo Alpino nella Preistoria. Catalogo della Mostra; Poggiani Keller, R., Ed.; Edizioni Franco Cosimo Panini: Modena, Italy, 1989; pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Poggiani Keller, R.; Massari, A.; Baioni, M. Aspetti dell’insediamento e abitati d’altura nell’età del Bronzo e del Ferro in Lombardia. In Höhensiedlungen der Bronzezeit und Eisenzeit. Kontrolle der Verbindugswege über die Alpen/Abitati d’altura dell’età del Bronzo e del Ferro. Controllo delle vie di Comunicazione Attraverso le Alpi; Dal Ri, L., Gamper, P., Steiner, H., Eds.; Temi Editore: Trento, Italy, 2010; pp. 165–231. [Google Scholar]

- Marzatico, F.; Solano, S. Reti e Camuni. Vicini e lontani. Riv. Sci. Preist. 2022, LXXII S2-202, 753–765. [Google Scholar]

- Rondini, P. Genti di Montagna. Valle Camonica e Prealpi lombarde nella prima età del Ferro. Riv. Sci. Preist. 2022, LXXII S2-2022, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Solano, S. Ceramica della media e avanzata età del Ferro. In Il Santuario di Minerva. Un Luogo di culto a Breno tra Protostoria ed età Romana; Rossi, F., Ed.; ET Edizioni: Milano, Italy, 2010; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- de Marinis, R.C. La cultura Breno-Dos dell’Arca e il problema degli Euganei. In Atti del II Convegno Archeologico Provinciale; Poggiani Keller, R., Ed.; Ante Quem Editore: Sondrio, Italy, 1999; pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rondini, P. L’interfaccia orientale della cultura di Golasecca. In Il Territorio di Varese in età Preistorica e Protostorica; Harari, M., Ed.; Nomos Editore: Busto Arsizio, Italy, 2017; pp. 263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, F. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries; Waveland Pr Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, P.S. Early Bronze Age Pottery at Haschkeller in Bavaria: Visuality, Ecological Psychology and the Practice of Deposition in Bronze Age A2/B1. Archäologisches Korresp. 2010, 40, 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Giannichedda, E. Identificare e classificare. In Studi in Onore di Clementina Panella; Ferrandes, A.F., Pardini, G., Eds.; Sede Legale: Roma, Italy, 2016; pp. 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rondini, P. Protostoria delle Valli Lombarde. Vol. I: Insediamenti e Materiali dalle Province di Bergamo e Brescia; Quasar Editore: Roma, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- de Marinis, R.C. Il territorio prealpino e alpino tra i Laghi di Como e di Garda dal Bronzo recente alla fine dell’età del Ferro. In Die Räter/I Reti; Metzger, I., Gleirscher, P., Eds.; Athesia: Bolzano, Italy, 1992; pp. 145–174. [Google Scholar]

- Solano, S. Da Camunni a Romani? Dinamiche ed esiti di un incontro di culture. In Da Camunni a Romani. Archeologia e storia della romanizzazione alpina. In Proceedings of the Conference “Da Camunni a Romani. Archeologia e Storia della Romanizzazione Alpina, Breno-Cividate Camuno (BS), Breno, Italy, 10–11 October 2013; Solano, S., Ed.; Quasar Editore: Roma, Italy, 2017; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- de Marinis, R.C. Le popolazioni alpine di stirpe retica, Liguri e Celto-liguri. In Italia Omnium Terrarum Alumna. La Civiltà dei Veneti, Reti, Liguri, Celti, Piceni, Umbri, Latini, Campani e Iapigi; Pugliese Carratelli, G., Ed.; Libri Scheiwiller: Milano, Italy, 1988; pp. 99–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolone, M.; Bonafini, G.; Rittatore, F. La necropoli preromana di Breno in Val Camonica. In Sibrium, III; Amazon: Seattle, WA, USA, 1957; pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Anati, E. Le Origini della Civiltà Camuna; Edizioni del Centro: Capo di Ponte, Italy, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rondini, P.; Marretta, A.; Ruggiero, M.G. Nuove ricerche archeologiche a Capo di Ponte (Valle Camonica, BS): Dos dell’Arca e l’area dei “Quattro Dossi”. Foldr—Fasti Online Doc. Res. 2018, 414. Available online: https://fastionline.org/s/folder/item/97051 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Rondini, P. Dos dell’Arca. La ripresa dello studio, cinquant’anni dopo. In Digging Up Excavations. Processi di Ricontestualizzazione di “Vecchi” Scavi Archeologici: Esperienze, Problemi, Prospettive. Proceedings of the Conference “Digging Up Excavations”, Pavia, Collegio Ghislieri, Pavia, Italy, 15–16 January 2015; Rondini, P., Zamboni, L., Eds.; Quasar Editore: Roma, Italy, 2016; pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rondini, P.; Marretta, A. Dos dell’Arca e l’area dei Quattro Dossi (Capo di Ponte, BS): Un aggiornamento. Boll. Del Cent. Camuno Studi Preist. 2021, 45, 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Solano, S. Le iscrizioni di Berzo Demo nel quadro dell’epigrafia preromana della Valcamonica: Il contesto archeologico e territoriale. In Pagine di Pietra. Scrittura e immagini a Berzo Demo fra età del Ferro e Romanizzazione; Marretta, A., Solano, S., Eds.; Quaderni, 4: Breno, Italy, 2014; pp. 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Mottram, H.R.; Dudd, S.N.; Lawrence, G.J.; Stott, A.W.; Evershed, R.P. New chromatographic, mass-spectrometric and stable isotope approaches to the classification of degraded animal fats preserved in archaeological pottery. J. Chromatogr. A 1999, 833, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drieu, L.; Rageot, M.; Wales, N.; Stern, B.; Lundy, J.; Zerrer, M.; Gaffney, I.; Bondetti, M.; Spiteri, C.; Thomas-Oates, J.; et al. Is it possible to identify ancient wine production using biomolecular approaches? STAR Sci. Technol. Archaeol. Res. 2020, 6, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evershed, R.P.; Dudd, S.N.; Charters, S.; Mottram, H.; Stott, A.W.; Raven, A.; van Bergen, P.F.; Bland, H.A. Lipids as carriers of anthropogenic signals from prehistory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1999, 354, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evershed, R.P. Organic residue analysis in archaeology: The archaeological biomarker revolution. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 895–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavari, G.; Fabbri, D.; Prati, S. Characterisation of natural resins by pyrolysis—Silylation. Chromatographia 2002, 55, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osete-Cortina, L.; Doménech-Carbó, M.T. Analytical characterization of diterpenoid resins present in pictorial varnishes using pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry with on line trimethylsilylation. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1065, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steigenberger, G.; Herm, C. Natural resins and balsams from an eighteenth-century pharmaceutical collection analysed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helwig, K.; Monahan, V.; Poulin, J. The identification of hafting adhesive on a slotted antler point from a southwest Yukon ice patch. Am. Antiq. 2008, 73, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regert, M. Analytical strategies for discriminating archaeological fatty substances from animal origin. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2011, 30, 177–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudd, S.N.; Evershed, R.P.; Gibson, A.M. Evidence for Varying Patterns of Exploitation of Animal Products in Different Prehistoric Pottery Traditions Based on Lipids Preserved in Surface and Absorbed Residues. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1999, 26, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evershed, R.P. Biomolecular archaeology and lipids. World Archaeol. 1993, 25, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Disnar, J.-R.; Arnaud, F.; Chapron, E.; Debret, M.; Lallier-Vergès, E.; Desmet, M.; Revel-Rolland, M. Millet cultivation history in the French Alps as evidenced by a sedimentary molecule. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, C.; Shoda, S.; Barcons, A.B.; Czebreszuk, J.; Eley, Y.; Gorton, M.; Kirleis, W.; Kneisel, J.; Lucquin, A.; Müller, J.; et al. First molecular and isotopic evidence of millet processing in prehistoric pottery vessels. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connan, J. Use and trade of bitumen in antiquity and prehistory: Molecular archaeology reveals secrets of past civilizations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1999, 354, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Ascencio, M.; Robertson, I.G.; Cabrera-Cortés, O.; Cabrera-Castro, R.; Evershed, R.P. Pulque production from fermented agave sap as a dietary supplement in Prehispanic Mesoamerica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14223–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffet-Salque, M.; Dunne, J.; Altoft, D.T.; Casanova, E.; Cramp, L.J.E.; Smyth, J.; Whelton, H.L.; Evershed, R.P. From the inside out: Upscaling organic residue analyses of archaeological ceramics. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 16, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, A.M.; van Bergen, P.F.; Stott, A.W.; Dudd, S.N.; Evershed, R.P. Formation of long-chain ketones in archaeological pottery vessels by pyrolysis of acyl lipids. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1997, 40–41, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drieu, L.; Peche-Quilichini, K.; Lachenal, T.; Regert, M. Domestic activities and pottery use in the Iron Age Corsican Settlement of Cuciurpula revealed by organic residue analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 19, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribechini, E.; Modugno, F.; Colombini, M.P.; Evershed, R.P. Gas chromatographic and mass spectrometric investigations of organic residues from Roman glass unguentaria. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1183, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanus, K.; Baeten, J.; Poblome, J.; Accardo, S.; Degryse, P.; Jacobs, P.; De Vos, D.; Waelkens, M. Wine and Olive Oil Permeation in Pitched and Non-Pitched Ceramics: Relation with Results from Archaeological Amphorae from Sagalassos, Turkey. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo di Caprio, N. Brevi annotazioni tecniche sulla ceramica del Dos dell’Arca. In Atti del Centro Studi e Documentazione sull’Italia Romana; Cisalpino Editore: Milan, Italy, 1976; Volume 7, pp. 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Breu, A.; Rosell-Melé, A.; Heron, C.; Antolìn, F.; Borrell, F.; Edo, M.; Fontanals, M.; Molist, M.; Moraleda, N.; Oms, F.X.; et al. Resinous deposits in Early Neolithic pottery vessels from the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 47, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, E.A.; Hart, J.P. Pine Resins and Pottery Sealing: Analysis of absorbed and visible pottery residues from central New York State. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelton, H.L.; Hammann, S.; Cramp, L.J.E.; Dunne, J.; Roffet-Salque, M.; Evershed, R.P. A call for caution in the analysis of lipids and other small biomolecules from archaeological contexts. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2021, 132, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, O.; Mulville, J.; Parker Pearson, M.; Sokol, R.J.; Gelsthorpe, K.; Stacey, R.; Collins, M.J. Detecting milk proteins in ancient pots. Nature 2000, 408, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, F. La fauna del sito pluristratificato di Malegno. In MuPRE. Museo Nazionale della Preistoria della Valle Camonica. Guida Breve; Poggiani Keller, R., Ed.; Litòs Ed: Gianico, Italy, 2017; pp. 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, J.; Rebay-Salisbury, K.; Salisbury, R.B.; Frisch, A.; Walton-Doyle, C.; Evershed, R.P. Milk of ruminants in ceramic baby bottles from prehistoric child graves. Nature 2019, 574, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović, D.; Meadows, J.; Dal Corso, M.; Kirleis, W.; Alsleben, A.; Akeret, Ö.; Bittmann, F.; Bosi, G.; Ciuta, B.; Dreslerovà, D.; et al. New AMS 14C dates track the arrival and spread of broomcorn millet cultivation and agricultural change in prehistoric Europe. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrizi, G. Contributo allo Studio della Ritualità Funeraria nella Verucchio Villanoviana: Analisi Contestuali e Biomolecolari, Tesi di Dottorato di Ricerca in Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale; Università del Salento, Dipartimento di Beni Culturali: Lecce, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Patrizi, G.; Rodriguez, E.; Rottoli, M.; Sala, I. Analisi archeobotaniche e dei residui organici dalle tombe villanoviane di Verucchio: Alcuni casi di studio multidisciplinare. In Proceedings of the Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria—56th Scientific Conference, Sciences of Prehistory and Protohistory: Palaeoecology, Archaeobiology, Digital Applications and Archaeometry, Ferrara, Italy, 20–23 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Castelletti, S.; Motella de Carlo, S. Le bevande protostoriche in Italia nord-occidentale ed i cereali nell’archeologia: Le ricerche archeobotaniche. In Del Vino d’orzo. La Storia della Birra e del Gusto Sulla Tavola a Pombia. Proceedings of the Conferences “Cervisia. La Birra Nell’archeologia e nella Storia del Territorio”, Pombia 13/4/2003 and “Spuma Cervisiae. La Birra nella Tradizione Novarese del Banchetto, dai Dati Archeologici ad Oggi”, Pombia 10/0/2004; Gambari, F.M., Ed.; Pombia, Italy, 2005; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.; Sanchez Rodrigues, V.; Mac an Bhaird, C.; Lotfi, M.; Kumar, M.; Horgan, D.; Dodd, S.; Danson, M. On the beer wagon: The past, present and future of Celtic brewing and its policies. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2023, 10, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maixner, F.; Sarhan, M.S.; Huang, K.D.; Tett, A.; Schoenafinger, A.; Zingale, S.; Blanco-Mìguez, A.; Manghi, P.; Cemper-Kiesslich, J.; Rosendahl, W.; et al. Hallstatt miners consumed blue cheese and beer during the iron Age and retained a non-Westernized gut microbiome until the Baroque period. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 5149–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambari, F. La birra dei Celti cisalpini ed i recipienti per degustarla, tra archeologia, storia e linguistica. In Del Vino d’orzo. La Storia Della Birra e del Gusto Sulla Tavola a Pombia. Proceedings of the Conferences “Cervisia. La Birra Nell’archeologia e nella Storia del Territorio”, Pombia 13/4/2003 and “Spuma Cervisiae. La Birra nella Tradizione Novarese del Banchetto, dai Dati Archeologici ad Oggi”, Pombia 10/0/2004; Gambari, F.M., Ed.; Pombia, Italy, 2005; pp. 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- Collis, J. Redefining the Celts. In Kelten am Rhein. Akten des Dreizehnten Internationalen Keltologiekongresses; Zimmer, S., Ed.; Verlag Philipp von Zabern: Bonn, Germany, 2010; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Götz, M. Identity and Power: The Transformation of Iron Age Societies in Northeast Gaul; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mostowlansky, T.; Rota, A. Emic and Etic. In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology; Stein, F., Lazar, S., Candea, M., Diemberger, H., Robbins, J., Sanchez, A., Stasch, R., Eds.; Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

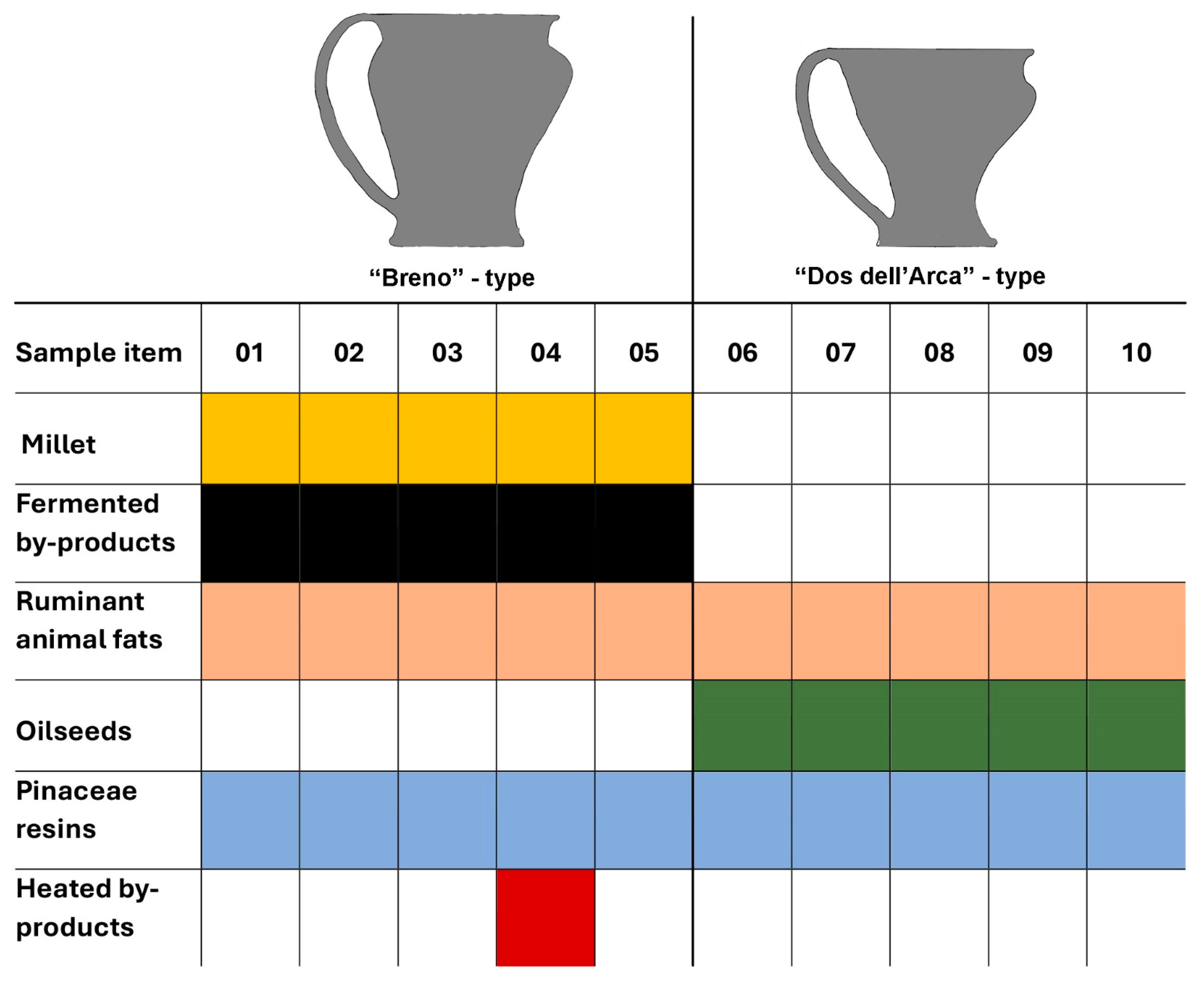

| Lab Code | Provenance | Type | Description | Size | Vessel Techology | Part of the Vessel Sampled | TLE (µg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector I, Trench C, US 2005 | Breno-Type | Base and low wall of “Breno”-type mug, with red paint on the exterior side. | Diameter 8.5 cm, height 3.3 cm. | Fine ware, yellowish brown. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 475 |

| 2 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector I, Trench C, US 2005—RR 56 | Breno-Type | Base and low wall of “Breno”-type mug. | Diameter 8 cm, height 2.3 cm. | Fine ware, light brown. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 508 |

| 3 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector I, Trench C, US 2005, RR 55 | Breno-Type | Base and low wall of “Breno”-type mug. | Diameter 9 cm, height 2.5 cm. | Fine ware, light brown with darker fire marks. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 143 |

| 4 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector I, Trench C, US 2006 | Breno-Type | Base and low wall “Breno”-type mug. | Diameter 9 cm, height 2.2 cm. | Fine ware, light brown. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 736 |

| 5 | Castione della Presolana (BG), Castello, Sector NW, Trench 2-2023, US 1201 | Breno-Type | Base and low-wall of “Breno”-type mug, with a concave base with a circular central cavity. It has a white encrustation on the inside. | Diameter 7 cm, height 4 cm. | Fine ware, light brown, with traces of red paint on the bottom. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 56 |

| 6 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector I, Trench C, US 2002 | Dos dell’Arca- Type | Base and short wall of a “Dos dell’Arca”-type mug. | Diameter 7.4 cm, height 8 cm. | Fine ware with mica, dark brown. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 1549 |

| 7 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector I, Trench C, US 2005, RR 50 | Dos dell’Arca- Type | Base and short wall with handle attachment for a “Dos dell’Arca”-type mug. | Diameter 9 cm, height 2.9 cm. | Fine ware with mica, reddish brown. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 177 |

| 8 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector I, Trench C, US 2006 | Dos dell’Arca-Type | Base and short wall of a “Dos dell’Arca”-type mug with incised line over the low border. | Diameter 8.8 cm, height 1.2 cm. | Fine ware with mica, greyish brown. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 69 |

| 9 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector I, Trench C, US 2005 | Dos dell’Arca-Type | Base and short wall of a “Dos dell’Arca” type mug with two incised lines on the wall (possibly part of an inscription) and a continuous vertical hole drilled between the wall and the bottom, possibly for repair. | Diameter 9.2 cm, height, 2.5 cm. | Fine ware with mica, dark gray. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 70 |

| 10 | Capo di Ponte (BS), Dos dell’Arca, Sector NW, Trench M, US 2101, RR 57. | Dos dell’Arca-Type | Base and short wall of a “Dos dell’Arca”-type mug, with incised line over the low border. | Diameter 8.1 cm, height 2.4 cm. | Fine ware with mica, light reddish brown. | Inner base of the vessel (L2) | 64 |

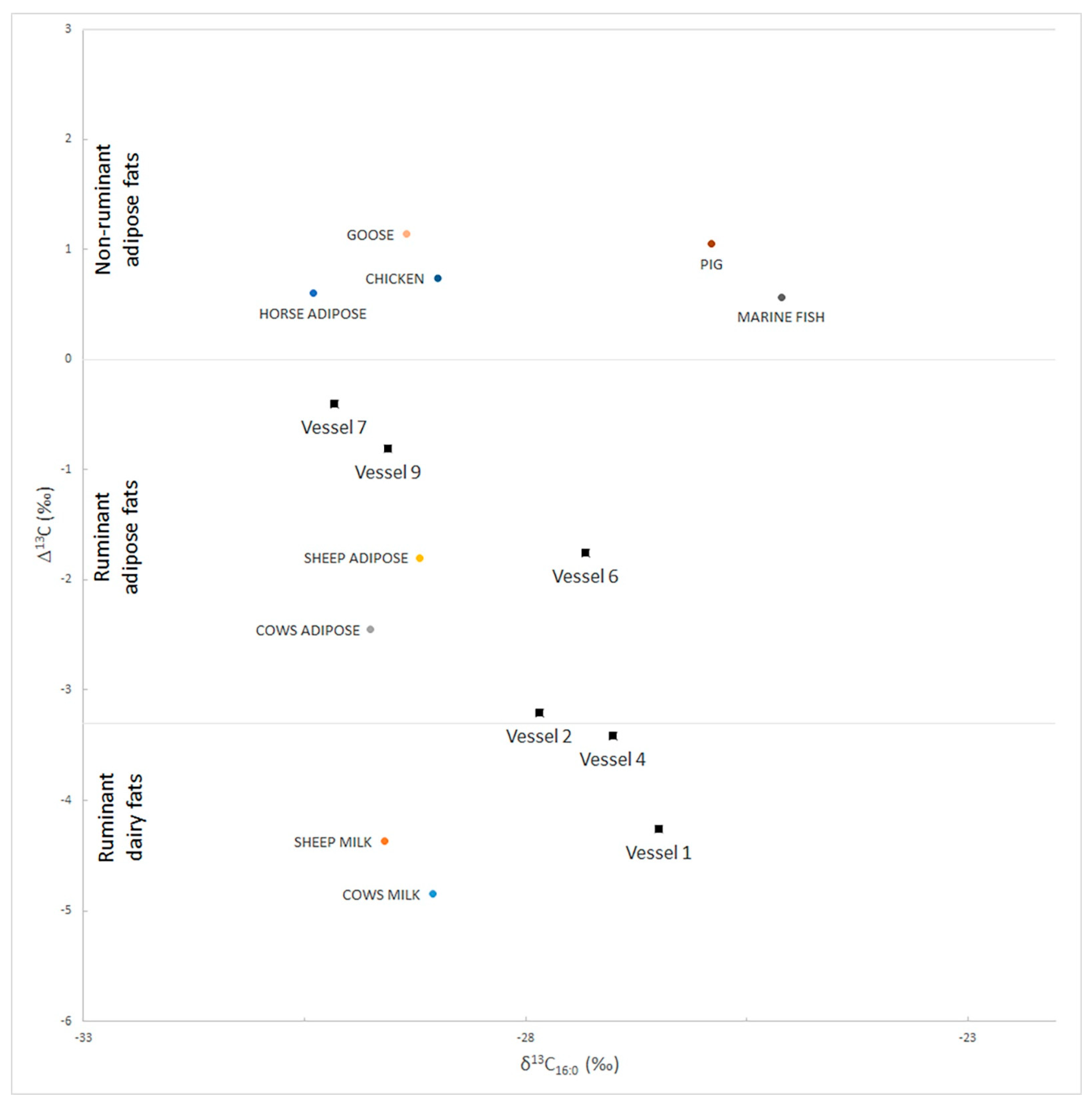

| Samples | δ13C16:0 | Δ13C |

|---|---|---|

| (‰ VPDB) | (‰ VPDB) | |

| 1 | −26.49 | −4.26 |

| 2 | −27.84 | −3.2 |

| 4 | −27.02 | −3.41 |

| 6 | −27.32 | −1.75 |

| 7 | −30.17 | −0.4 |

| 9 | −29.56 | −0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rondini, P.; Patrizi, G.; De Benedetto, G.E. Organic Residue Analysis on Iron Age Ceramic Mugs (5th–1st Century BC) from Valle Camonica—UNESCO Site n. 94, Northern Italy. Heritage 2025, 8, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060198

Rondini P, Patrizi G, De Benedetto GE. Organic Residue Analysis on Iron Age Ceramic Mugs (5th–1st Century BC) from Valle Camonica—UNESCO Site n. 94, Northern Italy. Heritage. 2025; 8(6):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060198

Chicago/Turabian StyleRondini, Paolo, Giulia Patrizi, and Giuseppe Egidio De Benedetto. 2025. "Organic Residue Analysis on Iron Age Ceramic Mugs (5th–1st Century BC) from Valle Camonica—UNESCO Site n. 94, Northern Italy" Heritage 8, no. 6: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060198

APA StyleRondini, P., Patrizi, G., & De Benedetto, G. E. (2025). Organic Residue Analysis on Iron Age Ceramic Mugs (5th–1st Century BC) from Valle Camonica—UNESCO Site n. 94, Northern Italy. Heritage, 8(6), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060198