1. Introduction

In recent decades, scholars have argued that the Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD) privileges monumental, urban, and state-sponsored heritage, often ignoring or marginalising alternative or local values [

1,

2]. As such, the prevalent focus on iconic architectural significance neglects the modest buildings that are equally infused with the heritage narrative. Although small-scale and modest structures contribute considerably to the cultural continuity of societies with their multidimensional heritage values, they are often overshadowed by magnificent and large-scale structures in the conservation of architectural heritage. These already overlooked structures have become even more invisible, particularly in peripheral rural areas. This imbalance is especially acute in peripheral rural landscapes, where heritage neglect converges with depopulation and shifting economies [

3].

In the rural expanses of Western Anatolia, renowned as a historic agricultural nexus enriched by Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman influences, the architectural heritage manifests in assets related to agricultural practices [

4], including the particularly distinctive and lesser-studied cold-water baths in the Birgi and Ulamış Villages of the Karaburun Peninsula in İzmir (

Figure 1). While the magnificent baths of ancient empires often receive comprehensive documentation, official recognition, and protection, these modest baths await acknowledgement and preservation. In contrast to the opulent baths adorned with majestic domes and intricate three-part layouts, these small-scale structures are designed with a single-spacing structure that is used for a quick cold-water shower. Their function defines local usage for villagers working in the agricultural fields and passengers travelling long distances.

Unlike hammams and Roman thermae, cold-water baths did not mean to stage the long, status-laden rituals that turned bathing into civic acting. Physically they are plain—a single chamber fed by wells without hypocaust furnaces or vaulted caldaria—but their deeper distinctiveness is social. Located beside wells and field tracks, each bath served a single itinerant farmhand or travellers who needed a shower before returning to work, rather than a town-dweller seeking leisure. Their masonry was assembled from reused fieldstone and maintained by village subscription; by contrast, Roman thermae were imperial benefactions, and Ottoman hammams were financed through royal waqf networks [

5,

6]. They used the agricultural calendar—open in harvest months and dormant in winter months—whereas urban hammams and imperial thermae operated year-round as fixed civic amenities [

7,

8]. No evidence links cold-water baths to weddings, maternity rites, or festival preparations, all of which filled the weekly and ceremonial calendar of hammams; instead, their intangible value lays in routine labour solidarity. As they are a testament to the agricultural customs, rural lifestyle, and local memory of Western Anatolia, they hold various values that form an exceptional significance worth acknowledging through their humble existence. Therefore, the following discussion situates these baths into the broader debate on vernacular rural heritage and the politics of scale in heritage ranking, underscoring the distinctive insights this study adds to that discourse.

However, the actuality of these rural and agricultural land is precarious. Although the region has exhibited impressive agricultural capability over the centuries, especially in growing crops like grapes, olives, figs, citrus fruits, tobacco, and cotton, these practices have experienced extreme transformations, especially after the 2019 COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 Samos earthquake. Due to the increasing interest in living in detached houses with gardens in peri-urban areas, these fertile terrains have been repurposed for residential developments. This transition endangers the cold-water baths, symbolic of a fading rural tradition, casting them to the edge of collective memory. The passage of time, the shifting societal contexts, and the absence of protective measures make these cold-water baths increasingly vulnerable. Today, only three baths, once numerous on the landscape, can be identified with field studies. The scarcity of archival material and historical records exacerbates this difficulty, leaving the memories of the elderly local population as the fragile repositories of this heritage at risk.

As they are vessels of collective memory, this research aims to trace the values of these structures and grasp their significance in the present. Combining a multi-disciplinary approach, the research begins with the initial phase that draws upon literature and archival records to form a historical overview. However, due to the lack of formal documentation, exploration merges into an ethnographical phase, leaning on interviews and the oral histories of village elders. As oral history puts flesh on the bones of history [

9], the locals’ narratives bring forth the cold-water baths with the social intercourse and communal life they once adopted. The subsequent spatial analysis refines the character of these structures within their geographical and environmental context, threading them back into the frame of existence as depicted in the oral histories. With these phases, this study applies a comprehensive value assessment to uncover the baths’ intrinsic value. Examining the values in a contemporary context reveals that although the baths are marks of rural history, they are now fading from the community’s collective memory. Therefore, this study guides the evaluation of architectural heritage, giving these modest baths the place they deserve and ensuring that their stories are not forgotten.

Figure 1.

The location of Birgi and Ulamış in the Karaburun Peninsula of İzmir, Türkiye.

Figure 1.

The location of Birgi and Ulamış in the Karaburun Peninsula of İzmir, Türkiye.

2. Methodology

This study aims to reveal the underestimated heritage values of cold-water baths in Western Anatolia’s agricultural context. Regardless of the type of heritage, value assessment requires a multi-dimensional perspective due to the fluid, subjective, and complex nature of values. Therefore, the research team of this study consists of conservation architects and sociologists with expertise in cultural heritage studies to perform an intricate evaluation of the cold-water baths’ values. The research is designed to unearth tangible and intangible attributes of the baths by examining their environmental setting and architectural characteristics and exploring their imprints within the collective memory. Due to the lack of reliable and relevant historical records, this research requires oral history reliance, predominantly sourced from the local community’s older generation. To secure narratives that were both temporally deep and geographically representative, a purposive, stratified-snowball approach was employed. Village headmen (mukhtar), and coffee-house owners first provided household lists indicating residents aged ≥50. From these lists, the team deliberately selected an initial core that balanced gender and five-year age bands. After each interview, participants were asked to nominate further elders “with clear memories of the baths”; those referrals were screened against the same residency and age criteria until thematic saturation was reached. This procedure yielded 24 interviewees in Ulamış and 12 in Birgi, matching the target quotas while ensuring that voices came from different kinship networks.

With an awareness that memories may not always align with historical accuracies and oral narratives harbour intrinsic personal biases [

9,

10,

11], the research team continuously cross-checked oral testimonies against literature review and field research. All interview recordings were first transcribed verbatim and anonymised. The transcripts were then examined in NVivo using a hybrid thematic approach: an initial set of heritage value categories guided the first read-through, while subsequent passes allowed new themes to surface inductively. Two researchers worked iteratively—regularly comparing their coding decisions, revising the code list, and discussing discrepancies—until a shared, coherent thematic structure was reached. Emerging patterns were finally cross-checked against field notes and archival evidence to ensure a balanced interpretation of both tangible and intangible values.

In this line, the methodological approach of this study is outlined below:

Literature review: The initial phase involves reviewing available literature. Though scant, these sources establish the contextual framework for the baths, guiding the subsequent phases of primary data acquisition.

Fieldwork: Acknowledging the gaps unearthed during the literature review, the second phase proceeds to detailed fieldwork. This initiative involves interviewing locals about the traditions and histories of the baths and collecting precise geographical, environmental, and spatial data. The research team meticulously records observations, conducts measurements of the structures, and drafts plans, sections, and elevations at specified scales to document the baths’ spatial and environmental context thoroughly.

Data Analysis: In the analytical phase, the collected data were integrated to perform a comprehensive value assessment. Coupling ethnographic insights with the architectural characteristics of the baths, this study deciphers the heritage values and significance of these structures.

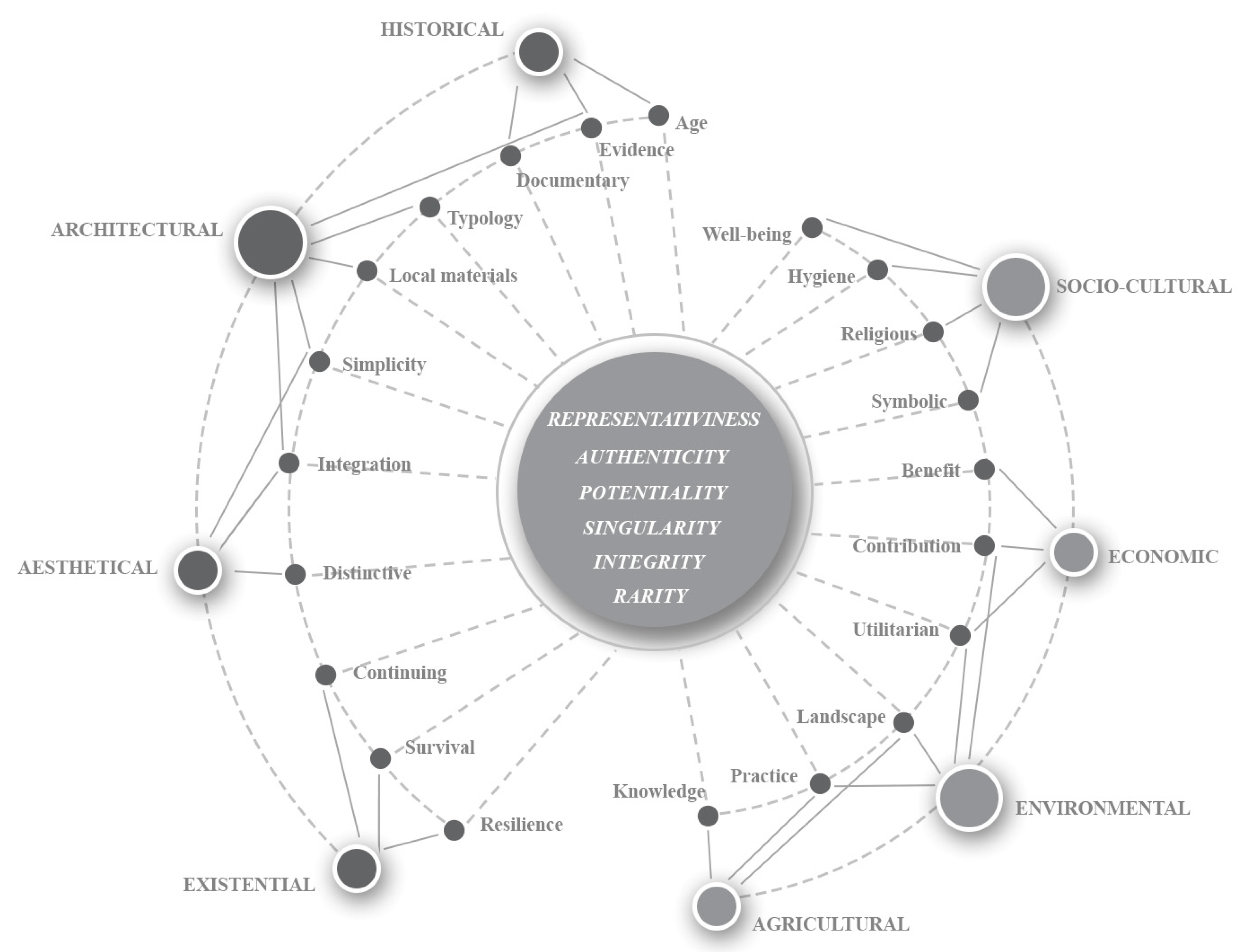

Value assessment: This stage establishes the cultural significance of the cold-water baths through a purpose-built valuation framework. Rather than applying an off-the-shelf matrix (e.g., those produced by the Getty Conservation Institute or English Heritage), this study developed its own typology by systematically reviewing the core heritage value discussion [

12,

13,

14]. Values embodied in the physical fabric were classified as explicit, whereas those inferred from social practice, landscape relations, or articulated community narratives were deemed implicit. Taken together, explicit and implicit values constitute the landscape’s intrinsic value—an emergent quality generated by the dynamic interaction of its elements and evaluated through criteria, such as representativeness, rarity, integrity, authenticity, and potentiality [

15]. This framework produces a rigorously documented register that traces the presence, persistence, and influence of each value and, in turn, demonstrates the baths’ cultural significance.

3. Results

This investigation centres on three cold-water baths, each embedded within its distinctive agricultural setting, revealing the nuanced interplay between architectural characteristics and rural traditions. Within the Ulamış Village of Seferihisar District lie the Üçkuyular and Zincirlikuyu baths, while the Birgi Village of Urla District is the location of the Hamamlıkuyu bath. Though numerically few, these baths embody the architectural heritage in the agricultural context of Western Anatolia, each standing as a testament to the values of societies within their landscapes. Despite a systematic literature survey, no documentary evidence was found that would allow us to date the construction or abandonment of the three baths with confidence. Additionally, none of the baths are currently registered by national heritage authorities.

3.1. Deciphering the Intricacies of Place

Amidst Western Anatolia’s rural history, the structures that form the focus of this study present a blend of distinct environmental integrity, spatial originality, and architectural rarity. Villagers reinforce this meaning by naming each site after its principal well: Hamamlıkuyu (well with bath), Üçkuyular (three wells), and Zincirlikuyu (well with chain). These vernacular names show how local communities encode environmental characteristics directly into place names, reinforcing the intimate link between each bath and its surrounding water sources. The Hamamlıkuyu and Üçkuyular baths have a similar environmental context—strategically located along historical routes and vast farmlands and surrounded by functional wells. The ruins near these two structures suggest they were part of a larger complex, with various additional buildings, including inns, barns, and bakeries. The Zincirlikuyu Bath departs from this environmental pattern, with proximity to a single well.

Each bath, created for individual cleansing and ablution, forms a single space. The entrance doors to these baths are seamless, with no visible joinery or hinges. Still, niches on the walls provide a safe zone for users to keep their objects. The marker of utilitarian architectural design within these baths is the water tanks, ingeniously incorporated into the wall—organised explicitly for bathing and ablution. The cleaning ritual was both humble and creative. The user would block the tank’s midpoint tap with a wooden stopper to fill the tank with clean water. The tank’s structure narrows from the exterior to the interior, improving water flow. When the bather is ready, removing the stopper would release the cold water for a shower.

Today, these structures stand as empty shells, disconnected from their original context and function. The larger complex that once surrounded the baths has almost entirely vanished, except for a few remaining traces. The wells are now repurposed for modest agricultural irrigation, and the baths are deteriorating.

3.1.1. Hamamlıkuyu Bath, Birgi Village

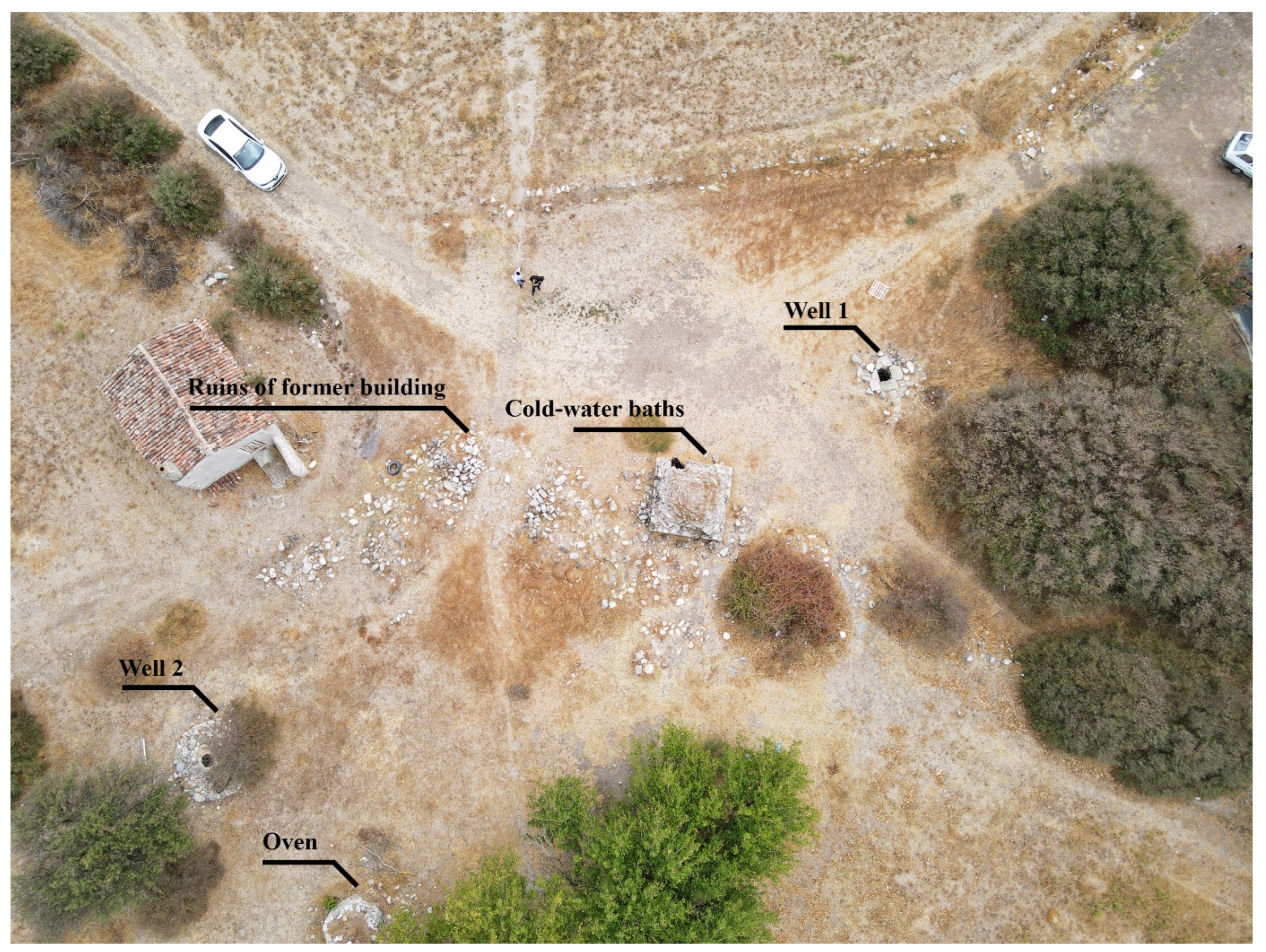

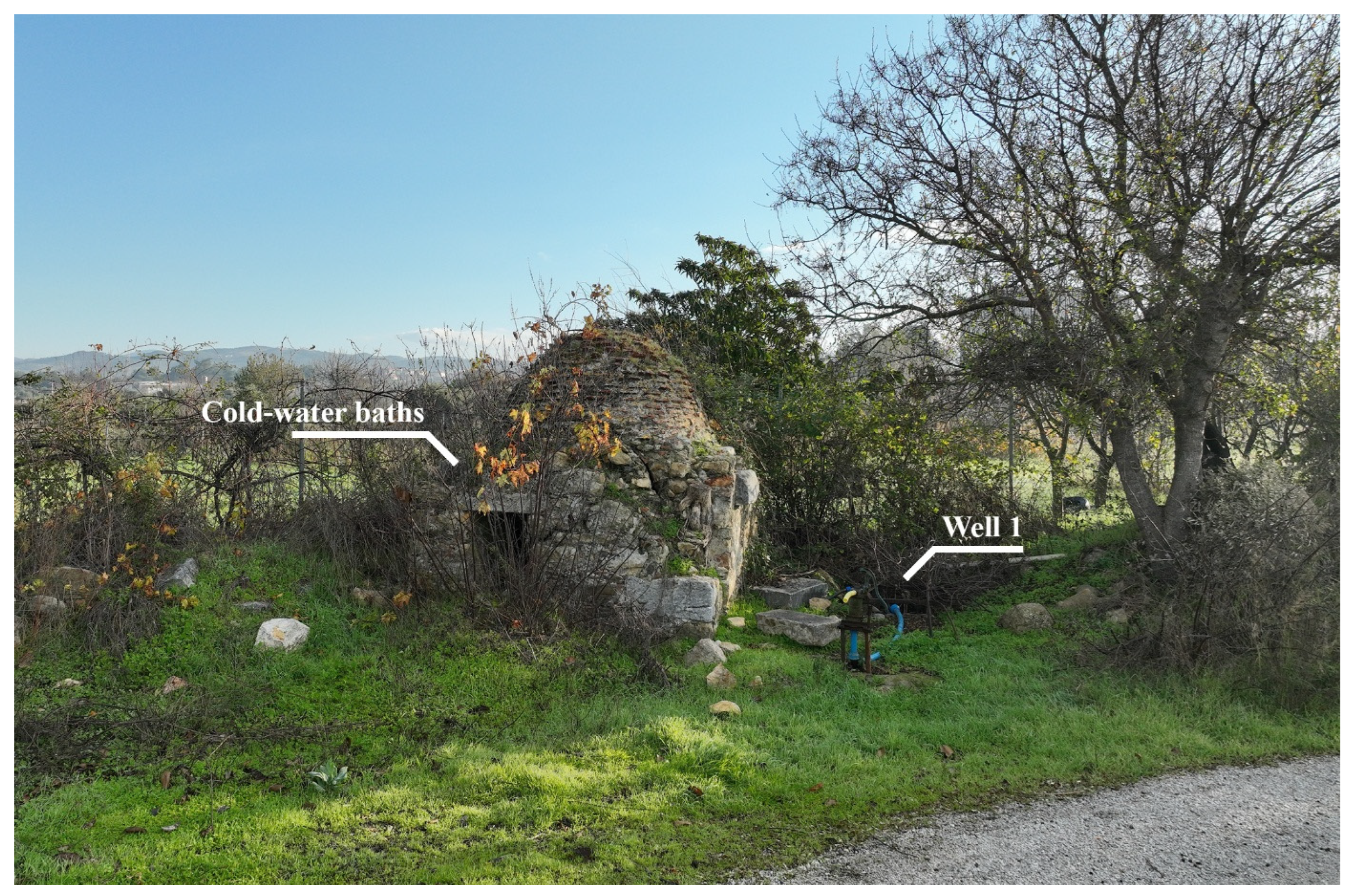

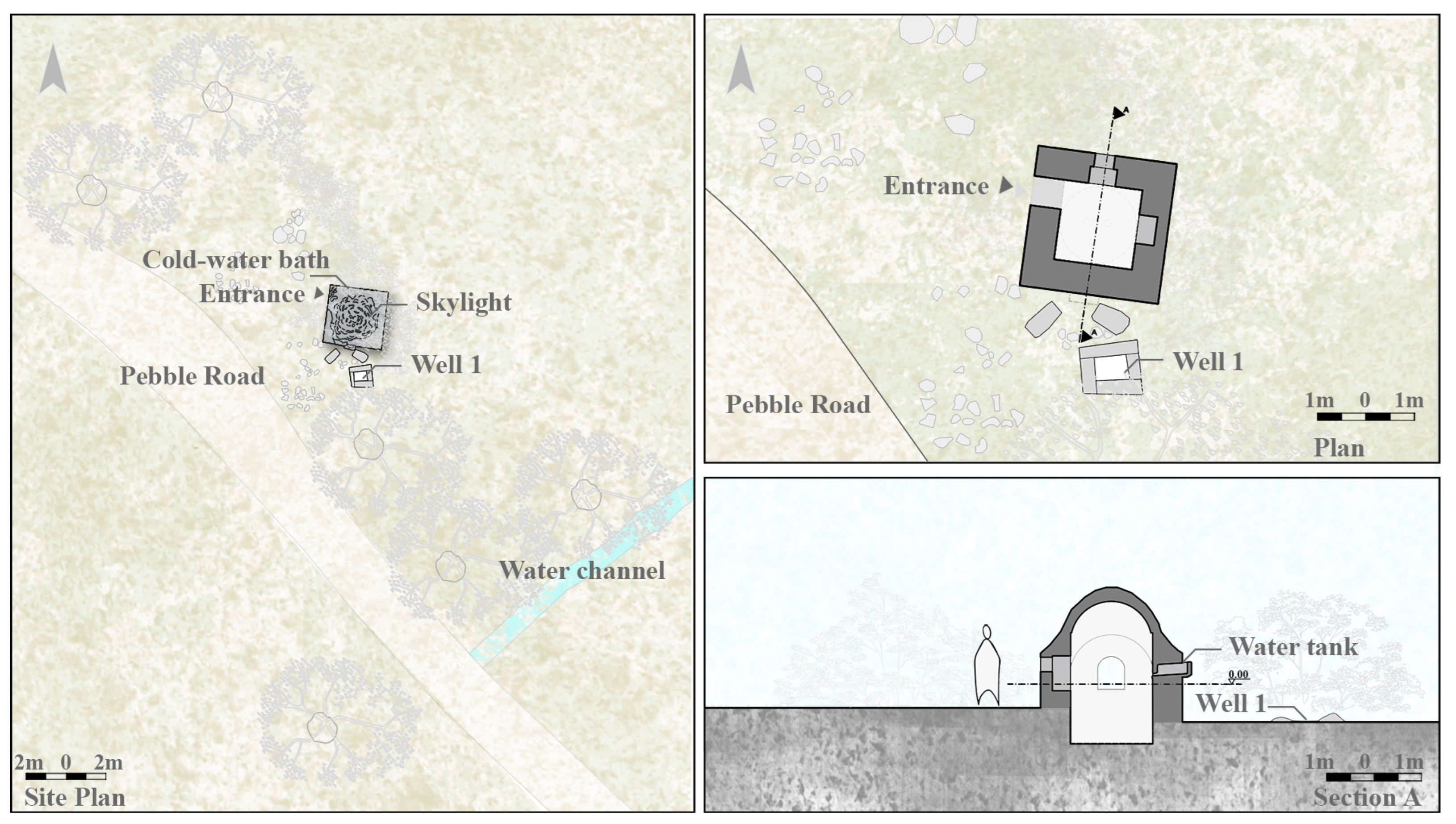

In the middle of wheat and cornfields, the Hamamlıkuyu Bath is an isolated monument far removed from the nearest habitation (

Figure 2). The site retains the foundational stones of a bakery, barn, and lodging facilities, though the actual structures have primarily eroded, leaving only these traces for archaeological reading, confirming oral histories that suggest it once served travellers on a historical postal carriage route (see

Section 3.2.1).

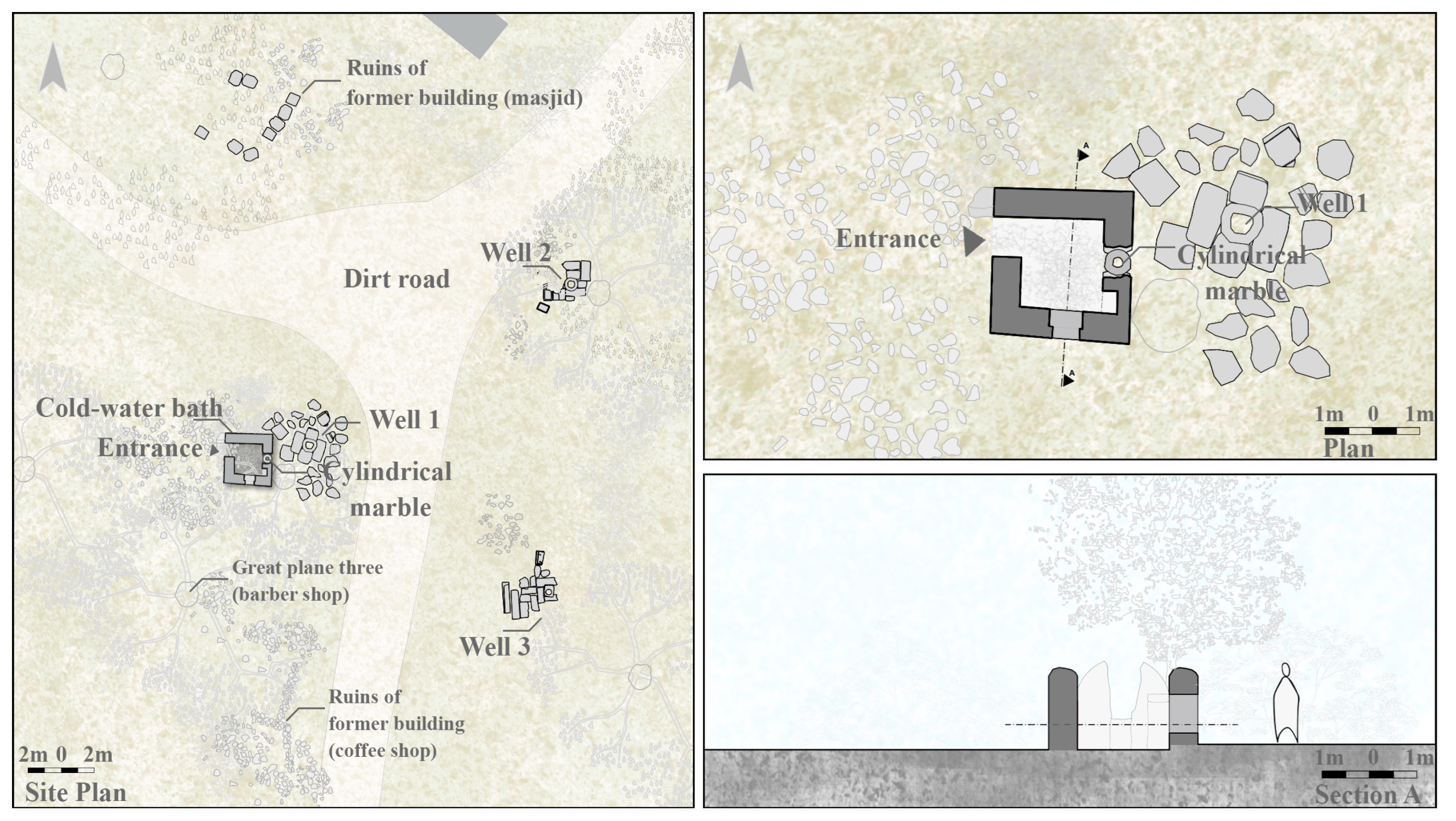

Two wells are intricately woven into the bath’s functional design, positioned at the core of the area (

Figure 3). The nearest well lies nearly 9 m from the edge of the bath, serving as the bath’s primary water source. The additional well falls within a radius of 25 m, establishing a vital water access network that is essential to the bath’s function. Structurally, the bath is defined by an almost square floor plan, with walls of approximately 3.5 m. The space is topped by a dome, reaching a height of nearly 2.5 m at its peak. Along the northern wall, the water tank is integral to the bath’s utility. It is further enhanced by a restrained drainage system that efficiently manages the expulsion of used water.

3.1.2. Üçkuyular Bath, Ulamış Village

Nestled amidst mandarin orchards, Üçkuyular Bath is isolated from nearby habitats. Its design mirrors the previously discussed Hamamlıkuyu Bath, sharing its integration with the environment and efficient use of space. Conveyed through oral history, directions at the ruins beside the bath—a coffeehouse and a masjid—as well as a notable tree repurposed as a barber’s corner, indicate that the bath was once a vital component of a service complex that likely served a caravan route (see

Section 3.2.2).

This bath is prominently framed by three wells, bordered by stones from the Ancient City of Heraklion (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The nearest well, located almost 1.5 m from the bath’s edge, acted as the water supply’s primary source. The bath presents with a nearly square plan, with each wall extending 3 m. Although the original domed roof has vanished, historical accounts affirm its previous existence [

16]. The water tank has disappeared over time. However, logic based on a comparative analysis suggests that it once was embedded along the deteriorated northern wall near the well. A piece of cylindrical marble, taken from the ruins of the ancient city, marks the spot where the tank once stood. This marble was initially repurposed to reinforce the tank as part of the bath’s original construction. Additionally, features like the bench and water channel have also faded into the records of time [

16].

3.1.3. Zincirlikuyu Bath, Ulamış Village

The Zincirlikuyu Bath shares the isolation of its counterparts, settled amid agricultural land. However, it stands out independently, with no traces of other historic structures nearby. Almost 1 m from its edge, the bath’s primary well is surrounded by stones from the Ancient City of Heraklion (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

The architectural design reflects the other baths, offering a nearly square plan bounded by walls 3 m. With the original flooring having collapsed, the dome’s precise height remains elusive, though it is estimated to have reached about 2.5 m at its peak. Adorning the dome are three skylights, ingeniously integrated to invite light and ventilation into the interior space. Firmly unified into the northern wall, the bath’s water tank remains a central feature. Meanwhile, an intentional drainage passage on the southern side ensures water removal.

Taken together, the three baths reveal a clear spatial logic that mirrors their social roles (

Table 1). Hamamlıkuyu and Üçkuyular lie within multi-functional service complexes situated on historical routes, signalling their former use as communal nodes of rest, trade, and worship. Zincirlikuyu, by contrast, stands alone and closer to its solitary well, suggesting a more individualised practice of ablution. Their proximity to water likewise encodes meaning: the short well-to-bath distances at Üçkuyular (1.5 m) and Zincirlikuyu (1 m) point to highly ritualised, immediate access to cleansing, whereas Hamamlıkuyu’s longer distance of 9 m reflects a larger spatial choreography that once served travellers and livestock. Thus, the clustered versus isolated siting and dense versus minimal water networks map directly onto differing socio-cultural narratives of collective gathering and private devotion across the peninsula.

3.2. Unveiling Local Stories

Oral histories extend beyond simple recounts of actions, encompassing a broad spectrum of human aspirations, beliefs, and reflective considerations [

17]. The landscape serves as a critical contextual framework for these, guiding the narrative trajectory and acting as a vehicle for memory [

18]. As such, the narratives gathered in this study delineate a complex network that vivifies historical events and bridges generations, safeguarding the knowledge of practices that are increasingly fading from the collective memory of the community [

19].

The geographical distribution, architectural characteristics, and communal associations of the cold-water baths have shaped the oral narratives profoundly, with stories and cultural significance based on the traditions of the local population. The physical and communal contexts embedded within each bath provide the foundation for the oral histories, reflecting the societal interactions. The distinctions between regions enhance our comprehension of the baths’ cultural significance, emphasising the heritage transferred through local memory.

This study presents the challenge of addressing the enduring physical structures of the baths amidst the disappearance of associated memories. This phenomenon requires a deeper examination of the complex interplay between oral history and landscape transformation. As farmers encounter the physical remnants of past generations within the landscape, they engage in a silent dialogue with history, tracing the echoes of past lives and practices [

19].

Collected narratives are a profound resource for understanding recent and long-standing landscape changes. A detailed analysis of these recollections has provided nuanced insights, bridging significant gaps in historical records. Efforts have extended beyond documenting changes in the landscape to include an engagement with oral histories that shed light on traditional practices, thereby contributing to contemporary debates about conservation [

19].

Oral history research often involves engagement with elderly individuals, which is emphasised for several compelling reasons:

Elders possess extensive first-hand experiences of historical events, which can enrich the detail and depth of the narratives.

As custodians of intergenerational knowledge and traditions, they ensure the preservation of cultural heritage.

They are typically ready to impart this accumulated wisdom, benefiting the continuity of cultural memory across generations.

Their extensive life experiences predispose them to provide comprehensive and reflective contributions during interviews.

In this regard, this study focused on individuals aged 50 and older, aiming to harness their deep-seated knowledge and memories. In the Ulamış Village, interviews were conducted with 24 residents, comprising 11 women and 13 men. The participants were stratified into several age cohorts: two women exceeding 80 years, four men aged 70 to 80, and fourteen individuals (seven men and seven women) between the ages of 60 and 70, with an additional four respondents (two men and two women) in the age range of 50 to 60 (

Table 2). In the Birgi Village, the interview cohort comprised twelve individuals, eight women and four men, all over 50 (

Table 2). It is important to note that not all participants could recall experiences related to the cold-water baths; expressly, relevant personal recollections were provided by only eight individuals from Ulamış and three from Birgi. Despite these variations in memory recall, the narratives collected from both villages yielded critical insights into the cold-water baths’ traditional functions and cultural significance.

3.2.1. Hamamlıkuyu Bath, Birgi Village

Delving into the oral histories complements the architectural and environmental traces, providing a rich perspective on the site’s past significance (see

Section 3.1.1). Constructed strategically at the crossroads leading to various remote villages, including Barbaros, Kadıovacık, Ildırı, Nohutalan, and Birgi, the Hamamlıkuyu Bath served as a crucial rest station along the old Çeşme road. It also functioned as a vital water supply point, diverging to feed the Nohutalan Fountain and the villages of Kadıovacık and Ildırı. Despite its current ruin, discernible remnants suggest the historical presence of a lodging facility adjacent to the bath, with a footprint of approximately 20 square meters.

In the 1950s, a village imam, as recounted by one of the elderly interviewees, described how postal carriages drawn by four horses regularly passed along this route. Connecting İzmir with distant locales, such as the older Çeşme road, this historical path was a lifeline for remote villages across the region. The route, identifiable amidst the outlines of an old dirt path, is occasionally used by mules today as they transport flour to the “Döşeme başı” ponds. In winter, to prevent the danger of vehicles skidding on the steep slopes, a 500 m stretch was paved with large black stones sourced from adjacent hillsides, creating a makeshift yet necessary roadway down to the plains. Evidence of this historical paving is still present near Tepe Kahve, leading towards the Hamamlıkuyu Bath.

The once-utilised road, dubbed Hamidiye Şosesi, which wove through Uzunkuyu and Gülbahçe’s olive groves, was officially paved in 1931. However, its decline began in the 1960s upon the advent of the new Çeşme road, rendering the former passage obsolete. Consequently, memories of the bath started to fade from collective memory. One elder recalled, “In our childhood, we played hide-and-seek in the bath, surrounded by vineyards that belonged to our ancestors. However, few remain who remember those days”. These surviving oral histories are responsible for preserving a heritage at risk of being forgotten. As the living links to this history become increasingly scarce, the preciousness of their recollections becomes ever more apparent, highlighting an urgency to record and safeguard these ephemeral memories.

In the context of such narratives, conservation efforts are becoming increasingly essential. The tangible and the intangible remnants collectively constitute a cultural heritage at the peak of vanishing. Engaging with the past through these narratives invokes a responsibility to develop sustainable strategies for conservation. Such strategies are essential to preserving these fading testaments of traditional agrarian life for future generations by safeguarding these physical remnants and perpetuating the oral histories that animate them.

3.2.2. Üçkuyular and Zincirlikuyu Baths, Ulamış Village

The cold-water baths Üçkuyular and Zincirlikuyu are relics from a past chapter in the Ulamış Village’s history. Üçkuyular and Zincirlikuyu lie within the same farm belt on the southern edge of Ulamış, scarcely 300 m apart, and were used—and are remembered—by the same village community; for that reason, their local histories are presented together below. These structures represent more than architectural remnants; they encapsulate the village’s vibrant agrarian heritage and collective memories. The mention of “cold water” elicits a tangible sensation, accentuating the significance of these elemental experiences within the community.

A local participant vividly recounts an era when tobacco agriculture propelled the region’s economy. During the humid summer months, farmers established temporary centres where they could stay overnight instead of returning to their homes in the village. Here, the cold-water baths were vital in the seasonal context of village life, providing a relaxing cold shower or ablution for those working under the sun.

The village narrative often returns to one defining landmark—a great plane tree that anchored the community’s social interactions (

Figure 5). More than a simple source of shade, the tree’s hollowed chest served as an inventive barber shop, exemplifying the villagers’ creative use of their natural surroundings in day-to-day life. Additionally, the expansive branches of the plane tree served a dual purpose, forming a makeshift dome for an open-air mosque beneath which a low wall, approximately 50 to 60 centimetres high, was constructed to define the sacred space. A strategically placed stone within this enclosure indicated the direction of the Mihrab, aligning the congregational prayers with religious prescriptions. The absence of a conventional roof was naturally compensated by the dense foliage of the plane tree, providing both shelter and a serene ambience. Moreover, three apertures carved into the stone base around the mosque facilitated water access for local wildlife, including bees and birds, ensuring these resources were continually replenished. This multifunctional use of the plane tree not only underscores the ingenuity of the villagers but also highlights the deep integration of their social, religious, and agricultural practices.

Adjacent to the communal tree was a modest coffee shop, an essential element during the busy summer months. This establishment contributed significantly to forming the temporary centres that dotted the landscape. Highlighting the remnants of this coffee shop and an adjacent area designated for Islamic ritual prayers (namaz), another participant illuminates the role of this site as a former social nexus. The participant describes, “This place served as a brief respite for travellers along the road, providing a space not for overnight stays, but for necessary pauses in their journeys”. This site was crucial for travellers heading towards Urla, often accompanying livestock, or transporting local produce, such as grapes or fruits, underscoring the historical importance of these roadside havens. The cold-water baths, integral to these centres, offered much-needed relief and refreshment. However, the narratives also reveal the ephemeral nature of these establishments, which have now faded into historical obscurity, highlighting the transient yet vital role they played in the socio-economic fabric of the region.

These narratives vividly illustrate the enduring yet vulnerable connections between the communities and their tangible past. These stories enrich our understanding of the region’s cultural landscape and underline the urgent need for strategies that safeguard this intangible cultural heritage. It becomes clear that preserving such heritage is crucial for honouring historical truth and maintaining the cultural continuity that defines this community.

4. Discussion: Fading Heritage Values

Heritage is a multidimensional cultural practice rather than a thing, blending with the concept of value [

20,

21,

22]. Values describe the various positive or negative markers attributed to heritage by relevant individuals or groups [

12,

13]. From this perspective, heritage and its values are created in the past and interpreted in the present [

23,

24,

25]. In current conservation practices, establishing connections between values, determining their potential benefits and risks, and interpreting them in multiple contexts come to the fore [

14,

26]. However, values are subjective and situational formations rather than fixed [

27,

28]. Therefore, their framing shows the influence of experts, researchers, and, most importantly, local communities [

29].

Local communities have an extensive, close, and enduring connection with cultural heritage through their identities, memories, sense, traditions, legal rights, and collective knowledge [

30,

31]. The values of the communities heavily influence their heritage perceptions, creating distinctive ties between a location and its historical narrative [

32]. With this central idea, scholarly discourse emphasises the critical role and need for a community-centric value assessment. However, if the connection between a community and its heritage diminishes within the practical realm, the risk of losing its values becomes acute and is a significant challenge for conservation. At this point, solid contact between heritage authorities and the community becomes imperative in uncovering and sustaining heritage values. Heritage authorities and experts have the potential to generate an influential synthesis of both social narratives and scientific investigation. By engaging directly with community perspectives, they can effectively highlight and discover the values to shed light on nuanced aspects of heritage that might remain overshadowed by the passage of time.

This study draws attention to the fact that breaking social ties with the heritage accelerates the loss of heritage values through the case of cold-water baths. The research examines the explicit and implicit values of the baths (

Table 3), drawing upon the connections between authority and society and relying on ethnographic and empirical methods for comprehensive validation. This analysis has uncovered that the collective memory of them is fading, confined to a sparse elderly demographic within the villages. These individuals, whose interactions with the baths are not derived from current use but from ancestral narratives, exemplify a decreasing link to the past.

Moreover, the lack of intergenerational transmission of knowledge signals a void where, once the elderly pass away, the baths’ values and significance might be lost. Fieldwork and in-depth interviews demonstrate that, despite their cultural significance, cold-water baths have largely been deprived of their value in the contemporary context and are now perceived merely as historical relics. Consequently, this study approaches the valuation of these baths through a professional lens, intending to unearth and articulate the values that were once intrinsic (

Figure 8) to their existence but are now obscured or absent.

Explicit values:

Historical: The baths document the region’s age and agricultural development. They retain historical narratives, anchoring the evidence of the community’s evolution.

Architectural: The architectural value of the baths emerges from their unique typology, setting them apart from the historical bath structures scattered across the region. Their construction techniques, materials, and supporting elements, such as water tanks and dug wells, represent the perception of local design in rural communities via the architectural creation for managing water resources.

Aesthetical: With their modest design, the baths blend with the agricultural landscape and exhibit distinct architectural details. These features represent the humble yet attractive characteristics of the structures.

Existential: The physical existence of the baths acts as a tangible marker of the rural communities’ relationship with water and the agricultural environment. Their continuity guides the region’s resilience, anchoring its history. Also, the wells state that water resources are integral to local life.

Implicit values:

Socio-cultural: The baths transcend their hygienic function, becoming social centres hosting communal activities and rituals. With their environmental context, they encourage community bonds by providing a platform for collective gatherings and religious practices. The construction of baths and wells that rely on the mutual support of volunteer villagers underscores the impact of baths on a rural way of life. Additionally, the baths play a role in shaping gender dynamics, offering separate times for women and men, which had a profound influence on the social fabric and the community well-being.

Economic: Strategically placed along historical routes, the baths were critical nodes in the regional trade network, supplying the needs of travellers and bolstering the local economy. Complementary facilities like coffeehouses and barber shops near the baths reveal a bustling micro-economy, particularly during the busy agricultural seasons when temporary labourers would stay in the region for months. These interactions demonstrate the symbiotic interplay between cultural heritage and economic activity.

Environmental: The baths’ location on agricultural landscape and reliance on non-irrigation water sources (rain runoff collected in wells and groundwater seepage from wells) provide an insight into the ecological practices of the local community. This sustainable water usage represents the harmonious integration of human activities with the landscape, encouraging local flora and fauna conservation.

Agricultural: Reflecting the ingenuity and practicality of agrarian communities, the baths constructed with materials and methods were attuned to the region’s ecological and climatic context. They were integral to the daily rhythm of agricultural life, serving as functional structures for bathing and social spaces for communal respite amidst intense labour periods.

These values derived from informed interpretation contextualise the baths within the expansive network of heritage in the broader region, balancing the tangible properties of these structures with the intangible threads of memory. Viewed in the context of the Karaburun Peninsula, which is celebrated for its abundant underground and accessible natural resources, these structures gain significance within a more expansive heritage narrative. This peninsula has diverse types of heritage, including water and geological assets. Current initiatives to improve this heritage repository design thematic routes that revitalise water and geological heritages and shape a significant landscape across the region [

33,

34]. Within this interconnected heritage network, the baths located in the villages of Birgi and Ulamış show heritage values, anchoring the communities’ social identity and collective memory. Accordingly, the intrinsic value (

Figure 8) represented below provide an expansive reflection of these inherent values, offering insights into the heritage reflection of baths within the larger scale of the Karaburun Peninsula.

Figure 8.

Illustration that explains the relationship between values.

Figure 8.

Illustration that explains the relationship between values.

This study identifies six intrinsic value categories. Representativeness, authenticity, and integrity evaluate how accurately the baths embody regional cultural–environmental patterns and preserve their physical fabric. Rarity captures each site’s narrative distinctiveness, whereas singularity denotes their statistical scarcity. Potentiality addresses the prospective benefits that sensitive interpretation and reuse could generate. The refined statements below elaborate on these distinctions.

Representativeness: The cold-water baths symbolise the region’s geology, hydrology, and culture via the interplay between the environment and local society. They are a microcosm of agricultural traditions and water culture, showcasing the ingenious adaptations necessary to practice and access life-sustaining water. Thus, these baths capture the region’s sense of place, standing as a testament to a way of life that prioritises sustainable interactions with the environment.

Authenticity: Despite their partial deterioration, the surviving elements of the baths allow for the discernment of the original purpose of the structures, affirming their validity. They are intrinsically valuable as examples of historical utility and markers of a community’s bond with its environment, as they represent the ingenious design born from the practical needs and resourcefulness of the community.

Integrity: Beyond their humble construction, these baths exemplify holistic integration, blending agricultural practices, natural resources, local culture, and the landscape. They respect the delicate balance between human activity and the natural world without interrupting the landscape, unifying themselves to the peninsula’s broader geographical and cultural context.

Rarity: This value captures qualitative uniqueness. The baths stand out as remnants of the rare architectural typology, presenting a local tradition of taking a shower and the daily lives of rural communities. Their simple yet practical design highlights heritage site diversity and challenges the idea that size and complexity equal historical significance.

Singularity: This value denotes quantitative scarcity. Their singularity emerges from their isolated yet practical existence in a broader context. Though they may stand as solitary units within their environment, their designs reveal a deep harmony with nature and a close bond with the agricultural way of life. While modest in materiality, their value is essential in social and historical contexts. Thus, they convey a peculiar narrative distinguishing them from Western Anatolia’s extensive bath complexes.

Potentiality: The baths represent a vital source of tourism potential by offering integral transition points along the designed thematic routes, such as water heritage and geological heritage routes in the Karaburun Peninsula. Thus, they offer distinctive opportunities to promote regional heritage and the local economy via the appropriate interpretation of tourism strategies.

Heritage is a cultural practice sustained by community values rather than intrinsic material qualities [

20]. By “demonstrating a principal characteristic of a class of places” [

21], these baths capture the role of the values as mnemonic anchors for villagers who recall seasonal labour rhythms and communal cleansing rituals. These values are not an abstract scholarly label, but an actively negotiated meaning endorsed by local actors who see the baths as extensions of their collective identity. They outline the baths’ role in a rural existence and capture their enduring bond with the broader context of Western Anatolia. Strategically embedded within the agricultural landscape, the baths serve as custodians of past rural traditions, and their design is a harmonious blend with the daily rhythm of agrarian life. Their enduring cultural significance emerges in their humble presence, expressing a profound narrative contrasting with the opulent baths of Western Anatolia. Recognising this community-anchored significance strengthens the argument that preserving the baths is indispensable to safeguarding the cultural landscape as a living whole.

Memory decay, however, compounds the challenge of safeguarding this significance. Because social memory is performed rather than passively stored, the death of its living bearers dismantles the intangible framework that gives material remains their meaning, rendering the fabric vulnerable to neglect or misinterpretation. Nora’s notion of “lieux de mémoire” illustrates this process: as embodied recollection fades, heritage sites become a community’s last mnemonic anchors [

35]. In peripheral landscapes, such as the Karaburun Peninsula, this tipping point can accelerate abandonment unless it provokes a “reactive” preservation response [

36]. As one elder observed, “The young ones don’t feel it—now it is just old stones to them”. Such testimony reveals how memory decay reduces the baths to mere relics in contemporary eyes. Our interviews show that intergenerational forgetting risks eroding local recognition of significance before formal protection can be mobilised. However, oral history research demonstrates that systematically recording and disseminating elders’ narratives can stabilise cultural memory while expanding public engagement [

37,

38]. Incorporating these testimonies into participatory interpretation is especially effective for younger residents, who relate more readily to human stories than to static fabric [

39]. Framing memory work itself as a conservation asset therefore recasts the safeguarding of the cold-water baths as an urgent task linked to the lifespan of the last knowledge-holders.

5. Conclusions

The conservation of heritage hinges upon the appreciation of its myriad of values. Appropriate conservation strategies entail more than simply maintaining a record of these values; they involve a robust action to transcend time while sustaining their actuality, relevance, and vitality for future generations. The traditional cold-water baths of Western Anatolia, examined in this study, offer a modest yet essential conception of heritage that illustrates the intricate interplay of structure, society, landscape, and culture, and documents human ingenuity in the sustainable use of water resources.

The three single-room baths of the Karaburun Peninsula are therefore not antiquarian curiosities but key witnesses to the region’s agrarian past. By analysing each bath in its social, cultural, and environmental context, this study has shown that the explicit values manifested in physical fabric remain visible, whereas the implicit values carried in social memory are fading. In the analysis made from a broad perspective, intrinsic values are illustrations that prove the actuality of heritage values. Their representativeness lies in how seamlessly they translate local hydrology into architecture; their authenticity and integrity persist despite their partial ruin; their rarity and singularity highlight both the statistical scarcity of this typology and the distinctive narratives that surround each site; and their potentiality signals untapped opportunities for community-based heritage tourism.

In Turkey, attention to rural architecture has steadily intensified as decision-makers seek ways to balance housing demand, economic diversification, and heritage stewardship across the countryside. Emerging management debates promote the retention of vernacular building stock as a living component of rural life, encouraging its use for small-scale accommodations, local craft production, and nature-based tourism. This study positions these modest structures as reference points within broader national efforts to link rural developments with cultural continuity by showing how the cold-water baths integrate functional ingenuity with landscape identity. The value typology established here can guide broader strategies that activate traditional buildings without eroding their authenticity, allowing conservation goals to advance alongside community well-being and visitor engagement.

On a broader scale, the findings resonate with current international discussions on the stewardship of small-scale water heritage and climate-responsive vernacular architecture. Global bodies emphasise sustainable water management as a pillar of the 2030 Agenda, noting that losing local water traditions undermines SDG 6 targets and community resilience [

40]. Small rural water facilities in Mediterranean and semi-arid regions are likewise experiencing abandonment and a fading collective memory, a trend documented in recent socio-ecological landscape studies [

41]. Consequently, the significance of the Karaburun baths extends beyond their immediate locality, supplying evidence that can inform regional policies across Anatolia and contribute to global debates on integrating modest rural structures into broader heritage and sustainability agendas.

On the other hand, external difficulties, such as pandemics, earthquakes, and economic crises, are changing the socio-cultural and economic dynamics of the region, and the residential pressures resulting from the increasing population are also causing the transformation of the landscape. These transformations threaten the cold-water baths’ cultural, historical, and environmental context with their multidimensional values. At the same time, the rapid decline of living memories means that only a diminishing number of elders can still share first-hand experiences of the baths, creating a critically short window for acting.

Against this backdrop, safeguarding the baths will require a multi-layered response. First, the remaining fabric should be stabilised through compatible conservation techniques and with the formal registration of each structure by the authorities. Therefore, these measures would establish a rigorous technical baseline while furnishing a legal shield against insensitive alterations. Parallel community-focused initiatives—travelling exhibitions, curriculum-linked site visits, and an open-access digital repository of elders’ oral histories—ought to embed the baths’ narratives within everyday cultural life and cultivate joint stewardship among villagers, schools, and heritage NGOs. The baths can be reactivated as heritage nodes within an expanded network of sustainable tourism corridors by integrating them into existing vine and olive routes, or into a newly branded “rural heritage route” or “water heritage route”, as proposed in recent scholarship [

34,

42], where visitor flows can be channelled to generate maintenance revenue, reinforce local identity, and stay within ecological carrying capacity limits. If such routes were administered under carrying capacity guidelines and community benefit-sharing agreements, they would broaden the regional tourism portfolio while balancing ecological and economic pressures. In this integrated framework, material integrity, historical narratives, and contemporary social functions would reinforce one another, aligning heritage conservation with the evolving livelihoods of the rural population.

Taken together, these recommendations constitute practical actions that stakeholders may adopt to preserve the baths’ physical remains, maintain their value in modern society, and integrate them meaningfully into today’s community. By coupling urgent conservation measures with locally driven interpretation and revenue generation, the baths can move from neglected relics to vibrant anchors of communal identity—ensuring that both their stones and their stories endure. These initiatives aim to enhance cultural heritage by anchoring it within the society’s identity and collective memory. In this way, the historical cold-water baths of Western Anatolia can become living evidence integrated with the community and offer experiences combined with the preservation of historical and cultural significance. Ensuring the continuity of the heritage values of historical cold-water baths in memory can shed light on the ever-changing identity of a living community and enable them to become cultural landmarks.