1. Introduction

Museums and cultural heritage spaces play a pivotal role in the economic regeneration of territories [

1]. However, the management of museums and cultural heritage spaces remains an unresolved challenge, as no single management model has proven universally effective across different countries or adaptable on a global scale [

2]. Contemporary cultural projects, often highly specialised, generate significant social transformations, yet concerns persist regarding their instrumentalisation as mere “social inclusion” programmes designed to fulfil governmental agendas [

3]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to explore alternative approaches to management models that align with contemporary societal needs, striking a balance between economic viability and social benefit. Such models must also facilitate the active participation of all relevant stakeholders in the decision-making processes within museums.

The effective articulation of a museum’s role within a given territory is intrinsically linked to the broader network of tourism actors and their interrelations. Thus, increasing attention must be directed towards the active management of the tourism space [

4]. This governance challenge is particularly pronounced in public cultural institutions, which require a level of flexibility to integrate external stakeholders capable of generating value and practical impacts in museum management [

5,

6]. Such flexibility can be achieved through varying degrees of hybridisation in museum management [

7], allowing institutions to incorporate diverse funding sources, operational structures, and decision-making frameworks.

One of the primary difficulties in cultural management concerns the practical implementation of cultural democracy [

8]. Current literature reveals a significant gap in the analysis of funding systems, organisational structures, and management models suitable for museums—particularly those adaptable to the evolving demands of contemporary society and capable of withstanding economic crises across different regions. Museums have demonstrated their capacity to provide extensive benefits to society, including conservation, economic development, enhancement of residents’ quality of life, and the strengthening of social networks. Given this, museums present a unique opportunity to advance collaborative approaches among stakeholders, fostering greater involvement in decision-making processes. This necessitates a shift towards governance models that not only encourage broader participation but also enhance the institutions’ responsiveness to the needs of the communities they serve [

9].

This study aims to identify the key components that define an effective governance model for museums, with a particular focus on public administration. By integrating elements from various existing management models, the objective is to optimise institutional performance while addressing the interests of all relevant stakeholders. To this end, a case study methodology is adopted, examining four distinct examples, each representing a different cultural heritage management model [

10,

11]. The selected cases, all located on the island of Gran Canaria, are as follows: (1) a publicly managed institution with organic dependency (Cueva Pintada Museum and Archaeological Park), (2) an autonomously managed museum (Néstor Museum), (3) a non-profit cultural organisation (Cultural Project for Community Development of La Aldea), and (4) a privately managed heritage site (Cenobio de Valerón).

The study employs a range of qualitative research techniques, including bibliographic review, documentary analysis, direct observation, questionnaires, and interviews. By applying data triangulation, a detailed comparative analysis is conducted for each of the selected cases, facilitating a deeper understanding of their respective cultural management strategies and the strengths and limitations of their governance structures. The findings suggest that improving the management of museums and cultural heritage institutions may necessitate more decentralisation of patrimonial administration, provided that such a transition is underpinned by robust mechanisms that ensure the accountability of local stakeholders. As noted by Santana Talavera [

12], governance models should foster a system in which local actors play an active role in decision-making, contributing to a more collaborative approach to museum management.

Consequently, this study examines the feasibility of a hybrid management model, wherein public-private partnerships and stakeholder interactivity are leveraged to enhance decision-making processes. This approach seeks to deliver broader benefits to all involved parties by balancing economic sustainability with cultural and social objectives. A comparative evaluation of cultural heritage management models is presented, particularly in relation to their governance structures and their role in shaping heritage tourism products.

Hypothesis: The implementation of a hybrid management model in museums and cultural heritage institutions will foster the active participation of multiple stakeholders, improve governance, and contribute to the sustainability and optimisation of the cultural and tourism product.

Objectives

General Objective:

To propose a hybrid governance model for the management of museums and cultural heritage institutions, optimising decision-making processes, fostering stakeholder participation, and enhancing the sustainability of the cultural and tourism product.

To analyse existing museum management models, identifying their strengths and weaknesses in terms of governance and stakeholder engagement.

To compare the effectiveness of different museum management models concerning sustainability, operational efficiency, and the integration of public and private actors.

To design a hybrid governance model that incorporates elements from public, private, and non-profit sectors, fostering collaborative approaches to cultural heritage management.

To identify potential obstacles and limitations to implementing the hybrid governance model, proposing strategies to facilitate its effective application.

By addressing these objectives, this research contributes to the ongoing discourse on museum management and cultural governance, offering an adaptable framework that can enhance the effectiveness, inclusivity, and long-term viability of museums and cultural heritage institutions.

2. State of the Question

The management of museums and cultural heritage institutions requires a structured approach that integrates elements from the public, private, and non-profit sectors, moving towards a hybrid governance model. While three primary types of hybrid models exist within organisational management [

13], their application to the museum sector remains underexplored. Given the evolving demands placed upon museums, new governance strategies are needed to optimise decision-making processes, foster stakeholder participation, and ensure the sustainability of cultural and tourism products.

Museums, like other cultural institutions, are increasingly engaging in community-driven interventions, reflecting a shift towards more collaborative approaches [

14]. The concept of the “hybrid museum” has primarily been discussed in the context of virtual museums, where digital interaction between visitors and managers enhances exhibition design and user experience [

15,

16]. However, hybrid governance in a broader sense—where multiple societal actors actively contribute to museum decision-making—remains a challenge [

17]. Beyond fostering engagement between museums and their visitors, there is an increasing need to integrate different individuals and community groups into governance structures to enhance social relevance and generate collective benefits.

Although sometimes insular in their involvement, local communities possess the potential to influence cultural marketing strategies and contribute to the effective management of museums [

18]. Governance models should therefore be designed to promote equitable participation, ensuring that disadvantaged groups, in terms of education and income, are not excluded [

19]. Museums must adopt an inclusive and collaborative approach to stakeholder management, fostering processes that facilitate engagement across all levels of society [

20]. This is particularly relevant in the context of heritage management, where interdisciplinary strategies are required to address sustainability and conservation challenges [

21]. The establishment of strategic alliances, both within the cultural sector and in complementary fields such as sports and recreation [

22], further underscores the necessity of cross-sectoral cooperation [

23].

Heritage management has evolved beyond merely conserving heritage assets to embrace a more integrated approach that addresses contemporary social needs. Ballart and Treserras [

11] define heritage management as “the set of programmed actions with the dual objective of (a) achieving optimal conservation of heritage assets and (b) adapting them to the most appropriate use of contemporary social demands.” This definition marks a departure from traditional conceptions that restricted cultural heritage governance to conservation efforts alone. Modern approaches advocate for a more comprehensive model that balances conservation with broader societal benefits, ensuring that heritage sites remain both protected and socially relevant.

The contemporary notion of heritage management is holistic and interdisciplinary, structured as a sequence of interconnected actions known as the “logical chain” [

24]. These actions encompass research, protection, conservation, restoration, and dissemination through educational initiatives. Effective governance in this field requires systematic planning and resource allocation, ensuring that heritage assets are preserved while remaining accessible to the communities that created them [

25]. This approach is grounded in the principle that cultural heritage must not only be safeguarded but also actively integrated into contemporary society.

Sustainability presents a significant challenge in heritage governance. Hall and McArthur [

26] highlight that heritage sites have often been commodified for statistical and economic purposes, leading to governance models that fail to account for the dynamic nature of cultural values. Achieving sustainability in heritage management requires flexible strategies that accommodate change. Three fundamental principles underpin this process: (1) the preservation of heritage tourism spaces in a manner that prevents degradation of their intrinsic values, (2) strategic planning that aligns governance structures with clear objectives and conservation measures, and (3) meaningful community involvement in decision-making [

27]. This study and research explores these dimensions by analysing governance models in four distinct case studies.

The complexity of heritage management stems from its inherently multifaceted nature, influenced by factors such as site characteristics, visitor dynamics, and the broader socio-political environment. Over time, numerous tools have been developed to assist managers in balancing the needs of stakeholders, maintaining conservation standards, and generating sustainable revenue streams. A well-executed governance strategy results in culturally and economically sustainable environments, benefiting both visitors and local communities. However, effective heritage governance should not be confined to direct citizen control; rather, it should facilitate public involvement through participatory mechanisms. By fostering a sense of local ownership, heritage managers can ensure that communities remain engaged in both conservation efforts and the economic opportunities associated with cultural tourism.

A critical consideration in museum governance is the financial sustainability of institutions. Heritage managers must reconcile conservation imperatives with economic viability, often necessitating difficult decisions regarding revenue generation [

28]. A key debate in this context is whether admission fees should be imposed, a policy that remains contentious within the public and non-profit sectors. While cultural heritage marketing can play a crucial role in raising awareness and increasing financial stability, it must be implemented strategically to manage visitor impact and preserve site integrity. Given these challenges, this study investigates how hybrid governance models can integrate public, private, and community-based funding mechanisms to enhance institutional resilience.

Heritage management serves as a mechanism for societal transformation, adapting to social, cultural, demographic, and economic shifts [

29]. Governance structures must therefore be sufficiently flexible to accommodate changes in employment patterns, cultural ideologies, and population dynamics. Failure to do so can result in governance inefficiencies, diminishing the capacity of institutions to respond to evolving societal needs. To address these challenges, strategic decision-making frameworks must be implemented, ensuring that cultural institutions operate with a clear mandate and measurable objectives [

30].

A central debate in heritage governance pertains to the degree of centralisation or decentralisation of decision-making within cultural institutions. While centralised governance models offer consistency and regulatory oversight, they often lack the agility required to address localised concerns. Conversely, decentralised models empower local stakeholders but may suffer from coordination challenges. Hybrid governance presents a potential solution, leveraging the strengths of both approaches while mitigating their respective limitations.

The governance of cultural heritage institutions extends beyond the preservation of physical assets to include decision-making processes related to technology adoption, information management, and stakeholder engagement. Strategic governance models must balance the interests of cultural producers and consumers, ensuring that heritage institutions remain relevant while preserving their historical significance. This study examines how hybrid governance structures can achieve this balance, facilitating a more inclusive and effective approach to museum and heritage management.

Although various organisations oversee cultural heritage, contemporary governance models can be broadly categorised into four main types: (1) state-controlled institutions with organic dependency, (2) autonomous entities with state oversight, (3) non-profit organisations, and (4) privately managed institutions [

10,

11]. Each governance model exhibits distinct organisational characteristics, presenting both strengths and limitations. This study proposes a hybrid governance model that synthesises these approaches, optimising decision-making, fostering stakeholder participation, and enhancing the sustainability of cultural and tourism products (

Table 1).

3. Methodology and Case Studies

The methodology section of this study adopts a qualitative research approach, designed to address the hypothesis and objectives outlined at the outset. Given the inherent complexity of museum and cultural heritage governance, qualitative methodologies provide a comprehensive means of exploring and evaluating various management models. To ensure the validity of the results, grounded theory was employed as the methodological framework, enabling theory development based on empirical data gathered from real-world contexts [

31]. Grounded theory integrates both inductive and deductive reasoning, facilitating an iterative analytical process that evolves as data are collected and interpreted.

3.1. Use of Software for Data Analysis

For the analysis of qualitative data, Nvivo 10 software was utilised. This tool, developed within the framework of grounded theory, supports data organisation, model visualisation, and the identification of patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed in manual analysis. Key features of Nvivo include structuring and analysing qualitative data, enabling the discovery of subtle thematic connections, and offering compatibility with other research tools such as Microsoft Excel 2019, Word Office 365, IBM SPSS 27, and EndNote 20 (Microsoft: Redmond, MA, USA). Furthermore, Nvivo enhances collaborative research by allowing multiple researchers to work on a shared dataset.

3.2. Data Collection Techniques

The data collection methods employed in this study are diverse and comprehensive, recognising that no single approach can fully capture the complexities of museum governance. The multi-method strategy ensures both reliability and depth in the analysis, incorporating a literature review and documentary analysis, direct observation, surveys, structured questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and informal conversations. These techniques collectively provide a well-rounded understanding of governance models, stakeholder engagement, and the effectiveness of current management strategies.

3.3. Case Selection and Interviews

Case studies were selected to ensure a diverse and representative sample, focusing on four distinct museum management models: the public governance model of the Cueva Pintada Museum, the autonomous management under public oversight at the Néstor Museum, the non-profit governance model of the Cultural Project for Community Development of La Aldea, and the privately managed Cenobio de Valerón heritage site. A total of ten interviews were conducted, distributed across two rounds, with directors or senior managers of the museums being interviewed, as well as an additional interview with the director of the Antonio Padrón House Museum (Gáldar, Gran Canaria, Spain) to obtain external insights. The interviews were structured around themes such as general governance, stakeholder involvement, and proposed improvements, with the second round focused on validating and refining the hybrid governance model. All interviews were audio-recorded and supplemented with field notes to ensure data integrity and reliability.

3.4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

Qualitative data analysis involved categorisation, triangulation, and comparative analysis. The data were systematically organised into thematic categories, and relationships between identified themes were explored to derive preliminary conclusions regarding governance models. This iterative process of interpretation and reflection, grounded in empirical evidence, supports the development of a hybrid governance model that is both practical and adaptable.

3.5. Generalisability of Findings

Concerning the issue of generalisability, the study acknowledges that qualitative research is context-dependent. However, its aim is to generate transferable insights with broader applicability, particularly in cultural heritage tourism management. While certain socio-political and administrative factors may require adaptation to different contexts, the core principles of stakeholder participation, governance optimisation, and sustainability remain relevant across various settings.

3.6. Case Study Approach

This research adopts a case study methodology [

32] to facilitate an in-depth examination of museum governance models, as defined by Simons [

33]:

“The case study is an exhaustive investigation and from multiple perspectives of the complexity and uniqueness of a given project, policy, institution, programme or system in a real context. It integrates different methods and is guided by evidence. The primary purpose is to generate a thorough understanding of a specific topic, a programme, a policy, an institution, or a system, to generate knowledge and/or inform the development of policies, professional practice, and civil or community action.”

The case study approach is particularly suited to this research, as it enables an exploratory, comparative, and context-sensitive examination of museum and heritage management models. As noted by Gratton and Jones [

34], case study research is characterised by:

The study of specific phenomena in a defined context;

In-depth exploration of each case;

Analysis of cases within their natural environment;

Contextualised interpretation of governance structures.

The methodological framework employed in this study ensures a rigorous and systematic examination of museum and heritage governance models. Through qualitative research, case study analysis, and thematic triangulation, this study seeks to propose a hybrid governance model that optimises decision-making processes, fosters stakeholder participation, and enhances the sustainability of cultural and tourism products.

By integrating empirical evidence, theoretical insights, and stakeholder perspectives, this research contributes to the development of a more effective, participatory, and sustainable model for museum and cultural heritage management.

4. Results

The results of this study emerge from a comprehensive analysis that includes interviews with museum directors, a thorough bibliographic review, and direct observation of the selected case studies. These results highlight a range of insights that reflect both the strengths and the challenges of existing museum governance models, as well as the necessity for an improved governance framework that can better meet the demands of cultural heritage management in the contemporary context.

4.1. Aspects to Be Highlighted in the Questions Asked of the Directors

The interviews with the museum directors provided insightful and multifaceted perspectives on the governance challenges they face, as well as the potential improvements that could be made to their current management models. These responses align closely with the hypothesis that the implementation of a hybrid management model can foster active stakeholder participation, enhance governance, and contribute to the sustainability of the cultural and tourism product. The directors’ reflections on key governance issues help contextualise the potential benefits of adopting such a model, as they identified several critical shortcomings in their current operational structures.

One of the most consistent concerns raised by the directors was the lack of mechanisms for interrelation between stakeholders. In each case, directors noted that while various internal and external actors were involved in the decision-making process, the communication channels were often insufficiently developed. This lack of structured interaction between stakeholders resulted in fragmented decision-making and missed opportunities for collaborative action. In line with the general objective of the study—proposing a governance model that optimises decision-making processes and fosters greater stakeholder engagement—this finding suggests that current models fail to leverage the full potential of stakeholder involvement. The importance of enhancing communication and collaboration across multiple governance layers is emphasised by scholars such as Žuvela et al. [

35], who argue that the integration of various stakeholders through well-structured communication channels is essential for sustainable governance in cultural institutions.

In addition to stakeholder interrelation, the directors also pointed to the lack of versatility in accessing financing as a major limitation. Securing adequate funding is a challenge faced by many cultural heritage institutions, and the existing models were found to be too rigid, with limited avenues for exploring alternative financial support beyond traditional government or private sector channels. As financial sustainability is one of the key factors that influence the long-term viability of museums and heritage sites, this finding is directly linked to the specific objective of comparing the effectiveness of different management models in terms of sustainability. According Romolini et al. [

36], a hybrid model that incorporates both public and private financing sources offers a more flexible approach, reducing reliance on a single funding stream and enhancing financial resilience. This is particularly important in an era where public funding for cultural heritage institutions is often under pressure, and there is an increasing need to balance operational costs with the demand for high-quality visitor experiences.

Another issue frequently raised by the directors was the difficulty in making decisions in a timely and effective manner. This was attributed to the hierarchical nature of existing governance models, where decision-making is often concentrated in a few key individuals or bodies, leading to delays and inefficiencies. This limitation ties directly into the study’s hypothesis, which posits that a hybrid governance model can improve decision-making by involving a wider range of stakeholders and decentralising authority. The specific objective of fostering stakeholder participation can be seen as an essential solution to this issue, as it encourages more inclusive decision-making processes that can lead to faster, more informed, and more effective outcomes. In their study on governance in cultural heritage institutions, Iaione et al. [

37] assert that decentralised models of governance are more adaptable and responsive to the evolving needs of both the institution and its community, allowing for more agile decision-making.

The time involved in putting decisions into practice was also identified as a significant challenge. Directors noted that the bureaucratic processes required to implement decisions, particularly in the context of public sector involvement, often slowed down the operationalisation of new initiatives. This issue of bureaucratic inefficiency is a frequent criticism of traditional public sector models of governance, where administrative procedures can be complex and time-consuming. According to Eid [

38], such delays are detrimental to cultural institutions, especially when they aim to remain relevant in the fast-paced world of cultural tourism. A hybrid management model, which incorporates both public and private elements, could streamline decision-making processes by reducing bureaucratic obstacles and enabling quicker responses to emerging needs.

Another critical aspect highlighted by the directors was the difficulty in facilitating donations, which was often hindered by high levels of bureaucratic burden. Museums and cultural heritage institutions rely on donations to supplement funding, but the intricate administrative procedures associated with donation acceptance and management deter potential donors. This point reinforces the findings of Žuvela et al. [

35], who argue that reducing bureaucratic obstacles can enhance institutional flexibility and increase external investment, both in terms of financial contributions and community engagement.

On the other hand, volunteering emerged as an overwhelmingly positive factor in the management models observed. Directors across all case studies saw volunteers as a vital asset to the sustainability and operation of museums and heritage sites. The involvement of volunteers was viewed as a mechanism for increasing stakeholder engagement, reducing operational costs, and fostering a stronger sense of community involvement. This aligns with the specific objective of enhancing stakeholder participation by incorporating non-professional actors, who can bring diverse perspectives and skills to museum management. As noted by Sokka [

39], the inclusion of volunteers in museum governance can increase public ownership of cultural heritage and create a more inclusive and participatory management approach. Volunteers also contribute to a more sustainable model by providing services that would otherwise require paid staff, thus enabling institutions to focus resources on core activities such as conservation, education, and visitor engagement.

The responses from museum directors revealed several critical areas for improvement in the current management models, all of which align with the hypothesis and objectives of the study. The lack of effective stakeholder interrelation, limited financial flexibility, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and the need for increased volunteer engagement are all issues that the proposed hybrid governance model aims to address. By incorporating a more collaborative, flexible, and inclusive approach, the new model has the potential to enhance both the governance and the sustainability of cultural heritage institutions, fostering a more dynamic and participatory management system that can better serve the needs of all stakeholders involved.

4.2. Results of the Management of the Case Studies

The analysis of the four case studies reveals varying degrees of success and areas for improvement in the governance models currently in place. Each case study offers distinct insights into the different approaches to cultural heritage management and the challenges that arise from each.

The governance model at Cueva Pintada Museum reflects a public–private partnership, which, while functional, could be improved. The current model ensures that the museum is able to maintain public service and guarantee access to visitors. However, it also demonstrates a reliance on private companies, which could be reduced to foster a more balanced and self-sustaining governance structure. Public–private relations are regulated through public competitions for service provision, which has allowed the museum to maintain a degree of flexibility and openness. Nevertheless, there remains room for improvement in the balance between public and private interests to ensure long-term sustainability.

The governance model at the Néstor Museum, a public institution, could benefit from a structural update. A move towards a foundation model, with clearer roles for different stakeholders, could enhance its operational efficiency and governance capacity. The current model, which relies heavily on the financial support of the City Council, creates a degree of dependency on political decisions, which may limit the museum’s autonomy. However, the potential for improving cultural tourism and overall management effectiveness through a regulated participation model was recognised by the director.

The governance model at the Community Development Project of La Aldea is based on volunteerism, with the active involvement of local communities. While this model is seen as one of the most appropriate for management, especially in terms of community engagement, it is not without its challenges. Political and financial limitations are the primary concerns, as the model relies on the support of public administration, which can often be unstable and subject to political changes. The relationship between the public and private sectors in this case is dynamic, but the model suffers from an excessive dependence on public funding, which could undermine its sustainability in the long term.

The governance model at Cenobio de Valerón is entirely private, with decision-making authority resting with a private company. This model prioritises economic profitability, with little to no involvement of public or other stakeholders in governance decisions. While this approach may be effective in terms of operational efficiency and financial sustainability, it overlooks the benefits of stakeholder participation and the potential for collaborative decision-making processes. The lack of governance mechanisms that incorporate external agents and the public leads to a less inclusive and potentially less sustainable model.

4.3. Need for a New Management Model Methodological Application

The necessity for a new management model in museums and cultural heritage institutions has become increasingly evident in recent years. Existing management frameworks often show significant limitations in adapting to the rapid changes in cultural policy, stakeholder expectations, and technological advancements. This observation is in line with the conclusions of various studies, which highlight the growing need for innovative and hybrid governance models in the sector. According to ICOM [

40], hybrid models that combine public, private, and non-profit governance structures provide more robust and flexible solutions, allowing institutions to adapt to the shifting dynamics of cultural management.

In applying grounded theory to this study, a methodological framework that allows for the systematic collection and analysis of qualitative data, interviews and informal conversations to be conducted, and direct observations to be made in the case studies all point towards the urgent requirement to establish a governance model that enhances inter-stakeholder relationships. Grounded theory’s inductive approach enables the development of theories grounded in real-world evidence, which is crucial in addressing the complexities of cultural heritage governance [

41]. This methodology is particularly suitable in the context of this study, as it facilitates a detailed understanding of the experiences and perspectives of key museum directors and managers. These interviews revealed recurring patterns and concerns, including the lack of collaborative decision-making processes and the inadequate involvement of external stakeholders, all of which undermine the overall effectiveness and sustainability of current governance models.

The process of theoretical saturation, a key principle in grounded theory, became apparent during the data collection phase, particularly in the interview responses from museum directors. As data continued to be collected, the same concerns regarding the inefficiency of existing models were voiced repeatedly. These included issues with the bureaucratic processes that hindered donations, the lack of flexibility in securing financing, and the insufficient mechanisms for inter-agency collaboration [

42]. This saturation of themes confirmed the need for a revised governance model, one that is more adaptable and inclusive.

When asked directly about the necessity for a new management model, all directors across the case studies acknowledged the importance of innovation and expressed a clear consensus for the creation of a more integrative and hybrid governance model. This aligns with the findings of Žuvela et al. [

35], who argue that hybrid models that blend the strengths of different organisational structures—public, private, and non-profit—can facilitate greater flexibility, responsiveness, and stakeholder engagement in heritage management. A hybrid model, they suggest, promotes the dynamic interrelations among actors, ensuring that all relevant stakeholders, both internal and external, have a voice in decision-making processes.

In discussing the characteristics of the proposed hybrid model, the directors were unanimous in identifying the need to incorporate both internal (museum staff and management) and external (local government bodies, private sector partners, volunteer groups, and the broader community) stakeholders. The engagement of a wide range of actors, particularly from the local community, is critical in creating a governance structure that is not only more sustainable but also more representative of the diverse interests involved in cultural heritage management. As noted by Sokka et al. [

39], incorporating diverse stakeholder perspectives is essential to creating more inclusive and sustainable management practices in cultural institutions.

Furthermore, the proposed hybrid model should include a system of governance that is flexible enough to facilitate collaborative decision-making. This approach would counterbalance the current lack of versatility observed in the existing models, which often leads to slow decision-making processes and insufficient stakeholder buy-in. The creation of a governance model that fosters shared responsibility among stakeholders is an important step towards the optimisation of cultural heritage management. This will allow for the adoption of more responsive and proactive management strategies, ensuring that museums and cultural heritage institutions remain relevant and resilient in an era of rapid change.

The new governance framework should also address the financial limitations currently facing many museums. According to the findings of Lindqvist [

43], financial instability is a significant challenge for museums worldwide, especially when the reliance on a single source of funding—whether public or private—creates vulnerability. In contrast, a hybrid governance model that diversifies funding sources and integrates private and public sector contributions offers greater financial stability and ensures long-term sustainability.

In terms of strategies for action, the key differences between the existing and the proposed hybrid models lie in the approach to governance, the inclusion of diverse actors in the decision-making process, and the flexibility in responding to external challenges. For example, the hybrid model would involve the establishment of consultative bodies consisting of representatives from various sectors, enabling ongoing dialogue between stakeholders and facilitating more effective decision-making. Moreover, the model would emphasise flexibility in terms of adapting governance structures to the needs of the community and the demands of cultural and tourism industries, as proposed by Van Assche et al. [

44].

Thus, the shift towards a hybrid governance model is not just about improving decision-making efficiency but also about fostering collaboration, inclusivity, and sustainability. This transformation will contribute to the creation of a more dynamic and sustainable cultural ecosystem that benefits not only the museums and heritage institutions but also the local communities they serve.

4.4. Proposed Hybrid Management Model for Museums and Cultural Heritage Institutions

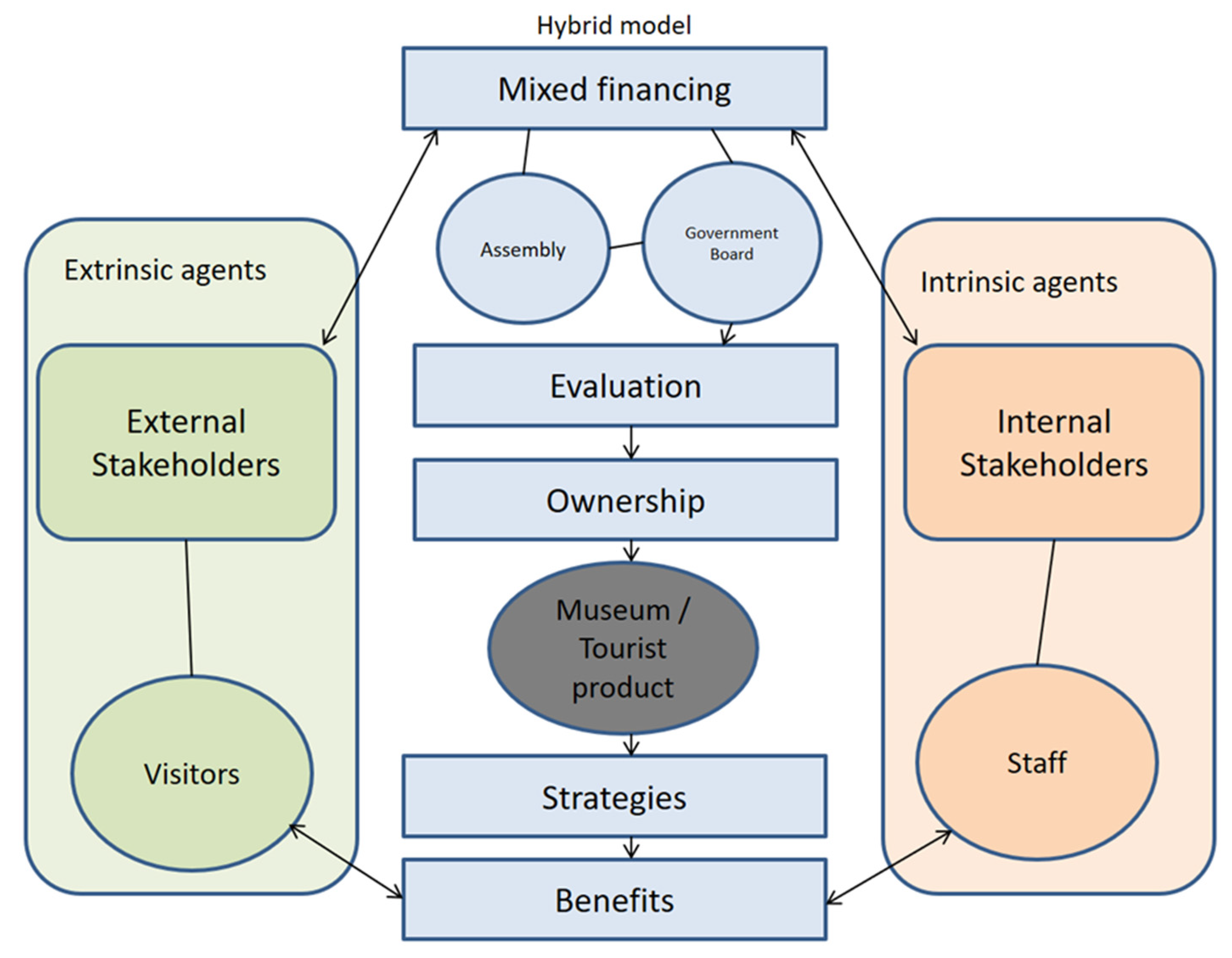

Based on the findings from the case studies, interviews with museum directors, and the analysis of governance models, this study proposes a hybrid management model for museums and cultural heritage institutions (

Figure 1). This model is designed to address the key challenges identified in the research, including the need for improved stakeholder engagement, financial sustainability, operational efficiency, and the integration of diverse governance actors. By blending elements from public, private, and non-profit sectors, the model aims to create a more collaborative, flexible, and inclusive governance framework, with the potential to foster participation, sustainability, and optimisation of cultural and tourism products.

The twelve points outlined below represent the core components of the proposed model, formulated based on the empirical evidence gathered and in alignment with the hypothesis that a hybrid governance model can enhance decision-making processes and foster active participation from multiple stakeholders.

Multifaceted Stakeholder Engagement: A central element of the proposed hybrid model is the active involvement of both internal and external stakeholders, including museum staff, local communities, governmental bodies, non-profit organisations, and private sector entities. This approach seeks to move beyond the often fragmented and siloed governance structures observed in the case studies, promoting collaboration across various stakeholder groups. Research consistently supports the idea that effective governance requires broad stakeholder engagement [

35], and this model aims to create platforms for continuous dialogue and shared decision-making, thus enhancing the legitimacy and inclusivity of the management process.

Decentralised Decision-Making: One of the key challenges identified in the research was the centralised decision-making processes in current models, which often lead to delays and inefficiencies. The hybrid model proposes a decentralised decision-making structure, wherein decisions are made at multiple levels, involving relevant stakeholders at each stage. This approach enables quicker responses to emerging challenges, empowers local actors, and allows for more adaptive governance [

44]. Decentralisation is particularly critical in enhancing the model’s responsiveness to community needs and ensuring that the voices of diverse stakeholders are heard.

Flexible Financial Model: To address the financial limitations of existing management models, the hybrid model incorporates a flexible financial structure that combines public funding, private sector investment, and community-based contributions. This mixed funding approach reduces reliance on any single source, providing greater financial resilience. According ICOM [

40], hybrid models that diversify financial support sources enhance the sustainability of cultural institutions by reducing vulnerability to economic shifts or budget cuts from public authorities.

Improved Resource Allocation: The hybrid model promotes more efficient resource allocation by involving multiple governance actors in identifying funding needs and distributing resources. Public sector actors can provide baseline funding for core activities, while private entities can invest in specific projects, and non-profit organisations can assist with operational costs. This collaborative resource allocation ensures that resources are used in the most effective manner, addressing both immediate needs and long-term sustainability goals.

Increased Volunteer Participation. Volunteers have been identified as a key asset for museum and heritage management. The hybrid model strongly emphasises the role of volunteers in museum operations. Drawing on the positive experiences shared by directors in the case studies, the model incorporates volunteer management systems that enhance community involvement, reduce operational costs, and foster a sense of collective ownership of cultural heritage [

39]. Volunteers can contribute to areas such as visitor engagement, educational programming, and conservation efforts, helping museums extend their reach and impact.

Integration of Public–Private Partnerships: The hybrid model establishes public–private partnerships (PPPs) as a central feature, aiming to strike a balance between public accountability and private sector efficiency. As identified in Case Study A (Cueva Pintada Museum and Archaeological Park), while public–private relationships can be beneficial, there is potential for improvement, particularly in ensuring that the public service aspect is not overshadowed by private sector priorities. By formalising these partnerships through structured agreements and regulations, the model ensures that both public and private actors contribute to the museum’s long-term goals while preserving its public service mission.

Collaborative Governance Mechanisms: The model integrates collaborative governance mechanisms that allow for more transparent decision-making processes. These mechanisms facilitate the participation of key stakeholders in discussions and decisions, ensuring that the interests of diverse groups are represented and addressed. The inclusion of governance structures that facilitate joint decision-making (e.g., advisory boards, consultative committees) has been shown to improve both institutional effectiveness and public trust in heritage management [

34].

Strategic Use of Technology: To support the management of diverse stakeholders and the efficient use of resources, the model proposes the strategic use of technology. This includes digital platforms for stakeholder engagement, data management systems for resource allocation, and online tools for volunteer coordination. The incorporation of technology can streamline processes, enhance communication, and enable more data-driven decision-making, ensuring the museum remains agile and responsive in an increasingly digital world.

Long-Term Sustainability Focus: The hybrid model prioritises long-term sustainability, both financially and operationally. The integration of various governance actors allows for better strategic planning, as resources and expertise are pooled from different sectors. The model encourages a focus on sustainability in all areas of operation, from environmental practices in museum facilities to the financial independence of heritage sites [

37]. This long-term perspective ensures that the museum remains relevant and operational in the face of changing cultural and economic conditions.

Stakeholder Accountability and Transparency: Transparency and accountability are fundamental to the credibility and effectiveness of any governance model. The hybrid model includes mechanisms to ensure stakeholder accountability and provide transparency in decision-making processes. Regular reports, audits, and stakeholder feedback mechanisms will be put in place to ensure that all actors involved are held accountable for their contributions and that the museum’s goals are being met. According to Žuvela et al. [

35], such mechanisms are essential in building trust and ensuring that governance remains responsive to the needs of all stakeholders.

Adaptive Governance Structures: The hybrid model embraces the principle of adaptive governance, recognising that the landscape of museum management is continually evolving. By creating flexible, dynamic governance structures, the model ensures that the museum can respond effectively to new challenges and opportunities. This adaptability is especially important in the context of cultural tourism, where trends and visitor expectations are constantly changing. Adaptive governance structures allow museums to innovate and experiment with new approaches to programming, engagement, and sustainability.

Evaluation and Continuous Improvement. Finally, the hybrid model includes an ongoing process of evaluation and continuous improvement. This ensures that the governance model remains relevant and effective over time. Regular assessments of performance, stakeholder satisfaction, and financial sustainability will guide iterative changes to the governance structure, allowing for constant refinement and improvement. This commitment to learning and adaptation is crucial for maintaining the museum’s long-term viability.

The implementation of the proposed hybrid management model offers several key benefits, which align with the core objectives of this research. By fostering active stakeholder participation, the model creates a more inclusive and collaborative environment, leading to more effective decision-making and enhanced community involvement. Furthermore, the diversified financial structure reduces dependency on any single funding source, promoting long-term sustainability and operational flexibility.

In addition, the model enhances governance transparency and accountability, improving trust between stakeholders and ensuring that decisions are made with the best interests of all parties in mind. The integration of public, private, and non-profit actors ensures that the museum is not only financially stable but also adaptable to changes in the cultural landscape. Ultimately, the hybrid governance model can optimise decision-making processes, leading to more efficient, sustainable, and impactful management of museums and cultural heritage institutions, contributing to the overall success of cultural and tourism products.

4.5. Explanation of the Model

Table 2 illustrates how the hybrid governance model incorporates a diverse array of stakeholders, each with clearly defined roles and responsibilities. The interaction between these actors fosters inclusive decision-making, optimises resource utilisation, and ensures long-term sustainability in heritage and museum management.

Government/Public Entities: The primary role of the public sector is to regulate, fund, and establish overarching policies. They are responsible for ensuring compliance with legislation and providing the necessary financial and regulatory infrastructure.

Private Institutions: Private institutions play a crucial role by providing financial backing and offering innovative approaches to museum management. Their involvement is vital for the economic and technological development of museums, and they often collaborate with public and non-profit organisations on joint ventures.

Non-Profit Organisations: These entities facilitate community participation and ensure that social and cultural interests are represented. They bridge the gap between local communities and larger institutions, ensuring that the voices of minority or disadvantaged groups are considered.

Local Communities: Local communities have a central role in the preservation and management of heritage. They bring valuable local knowledge, contribute to the intangible aspects of cultural preservation, and are actively engaged in museum management, especially when it pertains to decisions that affect their culture.

Visitors and Users: As consumers of cultural experiences, visitors provide crucial feedback that helps museums enhance their offerings. Their participation in cultural events and activities is also a vital component of the hybrid governance model, promoting cultural tourism and audience engagement.

Researchers/Academics: Researchers contribute specialised knowledge on heritage conservation and cultural history, providing evidence-based recommendations for museum and heritage management. Their expertise ensures that conservation practices are aligned with the latest scientific and academic standards.

Table 2 demonstrates how a hybrid governance model promotes effective collaboration among a variety of stakeholders, integrating their different resources, knowledge, and expertise. It facilitates a governance structure that is more inclusive, adaptable, and sustainable, ultimately supporting more effective heritage and museum management. This approach allows for balanced decision-making and ensures that museums and cultural heritage institutions remain socially relevant and economically viable.

4.6. Application of the Model to the Case Studies

The application of the proposed hybrid governance model to the four case studies presents various factors that can contribute to its success, as well as potential obstacles that may arise. Below, the key factors are outlined based on the governance models currently in place at each case study site and how they might align with or challenge the implementation of a hybrid model:

Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Structure: The existing public–private partnership model already has some elements of hybrid governance, offering a foundation for further development. The flexibility afforded by public competitions allows for a broader range of service providers, which could be enhanced in a hybrid model that integrates more varied stakeholder input.

Degree of Openness: The current system allows for a certain degree of flexibility and openness, making it conducive to integrating new actors and managing collaboration between public and private sectors in a more balanced way.

Over-Reliance on Private Companies: The current dependency on private companies could limit the museum’s self-sustainability, a challenge when trying to integrate a more balanced hybrid governance structure. A shift to a more diversified stakeholder model would require a reduction in this reliance and a recalibration of public–private relationships.

Balancing Public and Private Interests: Striking a balance between public interests (cultural preservation and accessibility) and private sector priorities (economic profitability) could be difficult, especially given the differing goals of each sector.

- 2

Case Study B: Néstor Museum

Public Institution with Potential for Structural Change: The museum’s status as a public institution offers a strong foundation for implementing a hybrid governance model, particularly through the potential transition to a foundation structure. This could enhance operational efficiency and provide more autonomy for decision-making processes.

Recognition of Cultural Tourism Potential: The director’s recognition of the importance of cultural tourism and management effectiveness aligns with hybrid governance goals, which aim to integrate diverse stakeholders in decision-making processes, fostering community participation and enhancing the museum’s relevance and sustainability.

Dependency on Political Decisions: The museum’s current financial dependence on the City Council presents a significant obstacle. Shifting to a hybrid model that reduces political influence and incorporates a more diverse range of stakeholders would require the museum to find new, stable sources of funding and align governance strategies to ensure greater autonomy and resilience.

Potential Resistance to Change: Transitioning from a highly centralised model (relying on public funding) to a more collaborative model may face institutional resistance, particularly from those invested in maintaining the existing political connections and financial arrangements.

- 3

Case Study C: Community Development Project of La Aldea

Active Community Involvement: The project’s reliance on community volunteerism and the active participation of local stakeholders aligns well with the inclusive principles of hybrid governance. The focus on local engagement could help ensure that the governance model remains relevant and rooted in the community’s needs.

Dynamic Public–Private Interaction: The existing dynamic between public and private sectors could be leveraged to create more formalised, transparent processes of collaboration, enhancing the overall management and sustainability of the project.

Financial and Political Instability: The reliance on public administration funding, which is subject to political changes and economic instability, poses a significant challenge to the sustainability of the hybrid model. The project would need to secure alternative or more stable sources of funding to avoid dependency on fluctuating public resources.

Volunteerism and Limited Professional Management: While volunteerism fosters community engagement, it may not be sufficient for handling the complexities of governance in a hybrid model. The project would need to integrate more professional management and decision-making expertise to ensure long-term sustainability and operational efficiency.

- 4

Case Study D: Cenobio de Valerón

Private Governance and Efficiency: The private governance model at Cenobio de Valerón has shown operational efficiency and financial sustainability, aspects that could be valuable in a hybrid model. The private sector’s approach to profitability could contribute to the economic sustainability of the broader hybrid governance structure.

Potential for External Partnerships: Although the current model excludes public participation, the potential for external partnerships with public and non-profit entities could be explored to integrate social and cultural elements into the decision-making process, making the model more inclusive.

Lack of Stakeholder Participation: The absence of public and other stakeholder involvement in governance may pose a significant obstacle to the success of a hybrid model, as this could limit the social relevance and inclusiveness of the model. Incorporating more stakeholders into decision-making processes would require a significant shift in governance philosophy.

Profit-Oriented Focus: The emphasis on economic profitability in the private governance model could conflict with the broader goals of hybrid governance, which include cultural preservation, social inclusion, and community engagement. The challenge would be to balance these economic objectives with the cultural and social responsibilities of heritage management.

Stakeholder Inclusivity: The model would benefit from ensuring that all relevant stakeholders (public, private, non-profit, and local communities) have a voice in decision-making. This inclusivity fosters broader support for governance strategies and enhances the long-term sustainability of cultural institutions.

Flexibility and Adaptability: The model’s capacity to adapt to changing financial, political, and social environments is crucial. Each of the case studies reveals the importance of flexibility—whether in reducing dependency on specific funding sources or adjusting governance structures to better engage diverse actors.

Collaboration Between Sectors: The model’s success hinges on effective collaboration between the public, private, and non-profit sectors. Each stakeholder brings unique resources, knowledge, and expertise to the table, and fostering meaningful partnerships between these groups can improve both cultural management and economic sustainability.

Community Engagement: Active participation from local communities and other stakeholders is vital in creating a governance model that is socially relevant and sustainable. The hybrid model encourages communities to take ownership of heritage sites, thereby ensuring that they remain valuable to future generations.

5. Discussion

This study contributes to the ongoing discourse surrounding museum and cultural heritage management by proposing a novel hybrid governance model that integrates the public, private, and non-profit sectors. Unlike previous research, which has primarily focused on the theoretical underpinnings of hybrid governance models [

13], this work bridges theory and practice by analysing concrete case studies and collaborating directly with cultural institutions. This practical approach facilitates the identification of gaps and challenges within current management systems and enables the development of a governance model that is both theoretically robust and pragmatically applicable.

While earlier studies have examined existing governance models in public institutions or private foundations, often isolating each sector’s strengths and weaknesses [

24,

45], this research departs from those traditional frameworks by specifically addressing the need for a hybrid approach. The proposed model fosters collaboration across all relevant sectors, encouraging a more inclusive approach to decision-making that integrates diverse stakeholders. This departure from a singular focus on one sector offers a significant shift towards a more balanced approach in heritage management.

Moreover, the case studies analysed here highlight the inherent challenges of aligning the diverse objectives of stakeholders involved in cultural heritage management, whether economic, social, or administrative. Public, private, and non-profit sectors each pursue distinct goals, which often conflict and can create inefficiencies in decision-making. This study reveals that these tensions, while challenging, also present opportunities for creating broader alliances and new partnerships that can lead to more effective governance structures. By addressing these challenges, the research provides actionable insights into how these competing interests can be harmonised within a single governance model, ultimately improving stakeholder collaboration.

One of the key insights from this research is the critical relationship between conservation and dissemination in decision-making processes. The study corroborates the work of Weil [

46] and Phillips [

45], emphasising the necessity of balancing the social mission of museums with their financial sustainability. By prioritising both conservation and public outreach, museums can achieve mutual benefits that enhance their long-term relevance. This research reaffirms the importance of stakeholder participation in governance mechanisms, as advocated by Brown [

47] and Ostrower and Stone [

48]. The study demonstrates how tangible partnerships and collaborations between museums and stakeholders—driven by negotiations, time investments, and financing—are crucial for successful management.

The hybrid model proposed in this research builds on Lord and Lord’s [

10] classification of four management models for cultural heritage institutions. By modifying traditional management systems, this new framework allows museums to evolve and adapt more effectively to contemporary needs, particularly in the context of cultural tourism. The model integrates the strengths of the public, private, and non-profit sectors while mitigating the challenges of traditional governance structures. In doing so, it offers a comprehensive and adaptable solution that can accommodate the complexities of modern heritage management.

Unlike other studies, such as Soria Martínez [

2], which suggests greater responsibility for public entities in alleviating financial pressures, this research advocates for a more nuanced hybrid model. It proposes a governance structure that blends the strengths of each sector, creating a balanced approach that addresses the unique challenges of museum management. Despite this potential, existing literature has yet to provide a comprehensive framework for developing a hybrid governance model tailored specifically to museums. This study fills that gap, offering a concrete model that can be adapted by various institutions facing similar challenges.

In summary, this research offers a fresh perspective on hybrid governance models, grounded in real-world case studies and practical applications. It not only enriches the theoretical discourse but also provides actionable insights for cultural institutions seeking to improve their governance structures. By emphasising the need for collaborative, multi-stakeholder approaches, this study encourages a shift towards more inclusive and adaptive management strategies. Ultimately, it contributes to the long-term sustainability and success of museums and cultural heritage institutions by facilitating more effective governance, which is essential for addressing both societal and economic demands in the 21st century.

While this study provides valuable insights into the potential of hybrid governance models in the museum sector, several limitations must be acknowledged. The research has been primarily focused on a select number of case studies, which, while illustrative, may not capture the full diversity of governance practices across different regions and cultural contexts. As such, future studies should seek to expand the scope of research by incorporating a broader range of case studies, particularly from international contexts. A comparative analysis of multiple international case studies would allow for a more nuanced understanding of how hybrid governance models can be adapted to different cultural and institutional environments. This would also facilitate a deeper exploration of the factors that influence the successful implementation of such models, including political, social, and economic variables.

Moreover, the research has not extensively addressed the practical challenges associated with implementing a hybrid governance model, such as the coordination of multiple stakeholders and the management of conflicting interests. Future studies should consider these practical challenges in greater detail, providing actionable recommendations for museum managers and policymakers.

While this study offers a strong foundation for understanding the potential of hybrid management models in museum governance, further research is needed to refine these models and extend their application to a wider range of cultural institutions. By exploring a more diverse set of case studies and addressing the practical challenges of implementation, future research can contribute to the development of more effective and sustainable governance structures for museums in the 21st century.

6. Conclusions

This work is the result of several years of field research, which included collaboration with some of the experiences and institutions analysed throughout the study. This research was accompanied by an extensive bibliographical review, and the proposed model, as a contribution to the ongoing discussion on museum and heritage management, can almost be seen as a direct response to the demands of the institutions themselves. We express our gratitude to these institutions for their invaluable collaboration.

In museum management, inefficiencies often arise in the organisation of public administration concerning cultural heritage, particularly in the areas of protection, promotion, and ensuring public access and enjoyment. Many existing models are still influenced by administrative structures from the first half of the 20th century, or there is a practical absence of professional organisational frameworks for managing these areas in relation to various resources or cultural products. Innovation in the organisation of these processes is essential across both public and private sectors. In fact, even within private museum management, there is a clear need to foster greater participation in decision-making processes.

Following the research conducted in this study, it is possible to affirm the validity of the hypothesis proposed at the outset: “The creation of a new museum management model would entail the active participation of the various elements that converge in the cultural product.” The hybrid participation model suggested here involves creating a management system that prioritises negotiation, debate, and cooperation, ultimately working towards the optimisation of the offered cultural product. The implementation of responsible management policies would, therefore, enhance the products, resources, or cultural assets presented by museums, creating a more dynamic and inclusive approach to heritage management.

Through the analysis of the management strategies applied in the four case study models, a clear gap was identified: none of the models effectively integrated stakeholders into the management process in a proactive manner. This need for collaborative action is what led to the proposal of the “hybrid model,” where various stakeholders are integrated with the aim of streamlining decision-making processes within museums (or other cultural heritage institutions). This model provides greater agility, reducing operational costs by avoiding the need for individual, fragmented management approaches for each project.

The necessity for the proposed hybrid model arises from the growing complexity of managing cultural heritage in the contemporary landscape. Traditional governance models often fail to address the dynamic interplay of public, private, and non-profit interests, which is essential for the modern sustainability of cultural institutions. The hybrid model offers a more inclusive approach, involving multiple stakeholders, including community members, private sector partners, and public entities, each bringing their unique perspectives and resources to the table. This collaborative framework can lead to more informed, agile, and sustainable decision-making, ensuring that museums and heritage spaces can respond more effectively to the changing demands of both visitors and stakeholders.

Thus, it can be concluded that governance in cultural heritage management functions as a strategic tool for the administration of responsible tourism products. By engaging stakeholders and implementing accountability mechanisms, it is possible to enhance the efficiency and overall quality of the cultural goods or experiences offered to visitors. This model not only benefits museums and heritage organisations but is also transferable to other institutions responsible for the preservation and utilisation of cultural heritage, ensuring its sustainability and improvement for future generations. This research, therefore, aims to contribute to the ongoing discussion and provide actionable insights for optimising the public–private governance of museums and cultural heritage institutions. For future management improvement studies, the governance of “heritage sites” could be studied in the future.