Abstract

The transition of Sketchfab, a widely used platform for hosting and sharing 3D cultural heritage content, to Epic Games’ Fab marketplace has raised concerns within the cultural heritage community about the potential loss of years of work and thousands of 3D models, highlighting the risks of relying on commercial solutions for preservation and dissemination. This shift, together with the unprecedented investments by the European Commission on infrastructures for digitised heritage, present a critical opportunity to restart conversations about the future of 3D scholarship and infrastructures for cultural heritage. Using a mixed-methods approach, this paper analyses data from a literature review, two surveys, a focus group, and community responses to Sketchfab’s announced changes. Our findings reveal critical user requirements, including robust metadata and paradata for transparency, advanced analytical tools for scholarly use, flexible annotation systems, mechanisms for ownership, licensing, and citation, as well as community features for fostering engagement and recognition. This paper proposes models and key features for a new infrastructure and concludes by calling for collaborative efforts among stakeholders to develop a system that will ensure that 3D cultural heritage remains accessible, reusable, and meaningful in an ever-changing technological landscape.

1. Introduction

On the 18th of September 2024, an email from Sketchfab support was sent to its registered users: “We’re excited to share that Fab—Epic’s new digital marketplace—will launch in mid-October…When Fab launches, it will replace the Sketchfab Store and you will no longer be able to buy or sell assets on the Sketchfab Store” (Sketchfab Support, personal communication, 18 September 2024). The email provided a timeline with the changes for Sketchfab users and a future roadmap, including the closing of the Sketchfab store in mid-October and the need to migrate assets/models to Fab as long as they comply with the platform’s licensing. Although the change in policy was flagged a year earlier [1], the September announcement sent shockwaves through the heritage community, which had grown to rely on the platform to host 3D content. Sketchfab is well known by this community for being a platform that not only welcomed but was arguably a key enabler of the growth of the creation and sharing of 3D models in the cultural heritage sector. While natively embedding 3D models on Web browsers is now possible through technologies such as WebGL and JavaScript libraries (e.g., Three.js, Babylon.js, and A-Frame), many institutions and researchers relied on Sketchfab, which ensured cross-device and browser compatibility through the embedding of 3D models on web pages using an iframe. This ready-made solution was particularly beneficial for those unfamiliar with Javascript and 3D rendering concepts, as well as those who do not have the capacity to host and optimise 3D models. As a result of the announced changes, the only option open to institutions and individuals who want or need to rely on a third-party platform to host their models is to migrate them to Fab. However, this migration necessitates complying with the software’s new publishing requirements, e.g., models can only be made available on a for-purchase basis. For many institutions, this shift may conflict with their institutional mandates.

After the September 2024 announcement, the cultural heritage and 3D enthusiast community responded on social media, including LinkedIn, X, Reddit, and Discord. This led to the development of the petition ‘Keep Sketchfab Alive: Preserve Open Access To 3D Art & Museum Collections’, which included the following statement: “This is the virtual equivalent of burning the Library of Alexandria.” [2]. From a business perspective, the shift in focus from Sketchfab to Fab is entirely reasonable as Fab will focus on their core constituency, the gaming industry. It has, however, made painfully visible the consequences of the reliance of the cultural heritage community on a key piece of infrastructure provided by the private sector. Sketchfab has become the de facto venue for hosting 3D models from institutions as varied as The British Museum, The Louvre, The Osaka Museum of Natural History, and The Virtual Museums of Małopolska (Kraków) to funded projects and archaeological teams, as well as freelance artists and hobbyist 3D modellers. The appeal of Sketchfab is primarily due to its offering a plug-and-play solution for sharing 3D content: from uploading models along with associated (albeit limited) metadata and annotating points of interest to applying different rendering modes and editing the models’ lights and materials. This combination of ease of use and functionality tailored to 3D models has resulted in the largest source of 3D heritage content published anywhere else on the web. In 2019, Sketchfab celebrated a milestone of 100,000 cultural heritage models, with almost 20,000 of these models downloadable and reusable under Creative Commons licences [3]. Sketchfab did not simply emerge as a repository for models from the heritage sector, but its activity encouraged its use by the community.

This shift in Sketchfab’s business model comes at a propitious time as the European Union is currently making significant investments—through initiatives like the Common European Data Space for Cultural Heritage and the Collaborative Cloud for Cultural Heritage—in supporting the development and display of 3D models for the heritage community. European and international initiatives (e.g., the TwinIt! campaign by the European Commission and Europeana) are underpinning institutional pressure to produce more than two-dimensional images of tangible heritage. Concurrently, we are witnessing an increase in 3D digitisation spurred by the promise of virtual reality and the metaverse. Regardless of whether Sketchfab is fully replaced by Fab or remains accessible to the cultural heritage community in some capacity, it has become clear that 3D heritage, and especially the presentation layer of 3D, will require greater attention in the coming years. While numerous researchers, projects, and working groups have explored the potential and challenges of disseminating and preserving 3D data in the arts and humanities, much of this work has focused on data curation and standards with much less emphasis on web-based viewing environments. Although several research groups have developed their own 3D viewers (3DHOP, Visual Media Service, Kompakkt, etc.), none have matched the ease of use and functionality that Sketchfab provided to the heritage community, as evidenced by the limited number of users who have integrated such software in their 3D workflows. Given these developments, as well as our experience in developing PURE3D—an infrastructure for the publication and preservation of 3D scholarship in the Netherlands—the authors of this article believe that it is timely to reconsider how three-dimensional cultural heritage is presented online and to discuss the needs and requirements that future infrastructures must meet to more effectively serve this community.

The aim of this paper is to argue for an open and sustainable infrastructure for 3D cultural heritage that is tailored to the requirements of the community. To do this, we will identify the needs and user requirements by critically looking at recent literature, two surveys—one conducted by the PURE3D project and one by Sketchfab— and a focus group on 3D viewing interfaces conducted in the context of the PURE3D project, as well as users’ responses to the announced changes to the possible demise of Sketchfab. The paper is structured as follows: First, we present a historical overview of Sketchfab, including how it emerged and how it changed over the years. This is followed by an outline of our methodology, the literature review, and the thematic analysis of the two surveys, the focus group, and the community’s reactions on social media. The final section consolidates the findings from the different sources and will propose features and services that a new open infrastructure should provide to the 3D heritage community. The paper concludes by highlighting the urgent need for a collaborative effort that brings together different stakeholders to develop a sustainable, open access infrastructure that not only meets the technical needs of the community but also ensures that heritage remains accessible for future generations.

2. Background and Context: Sketchfab—A Historical Overview

Sketchfab was established in Paris, France, by Alban Denoyel (CEO), Cédric Pinson (CTO), and Pierre-Antoine Passet (CPO), and it was publicly launched on 26 March 2012. Its predecessor was ShowWebGL, a proof-of-concept web-based 3D viewer developed by Pinson a year earlier. Sketchfab was released with the tagline “Showcase 3D models in your browser” and was described as the “first free service offering a simple way to upload and showcase 3D content online” [4,5]. As the founders say, Sketchfab was the result of frustration seeing “so many 3D creators spending hours on making great 3D models, but ending up sharing boring screenshots as there was no better solution to showcase their work” [6].

Sketchfab is a platform that enables users to upload, view, and share 3D models with several features (e.g., annotations, metadata, model interaction) that are object-type agnostic and thus appealing to a diverse audience, including 3D enthusiasts, researchers, gamers, marketers, and large institutions. A 3D viewer is the key feature of the platform that allows the seamless embedding of models on websites, social media, and forums without requiring additional plugins. The viewer is compatible with all major browsers and operating systems, supports virtual and augmented reality, and includes a model inspector for quality assessment. Models can be accompanied by a short description, tags, and categories to enhance discoverability, while visibility settings allow users to control access, enable comments and texture inspection, and define licensing terms, ranging from free standard and Creative Commons to commercial sales. The platform also integrates community-driven features, such as liking, sharing, commenting on models, adding them to collections, and embedding the model to other platforms by customising the viewing experience. For 3D creators, the 3D editor allows the customisation of 3D scenes by adjusting lighting, materials and backgrounds while also supporting animations, annotation, and first-person navigation. Although sound was originally supported, it was discontinued due to copyright concerns. Sketchfab also supports a simplified workflow through the Sketchfab API, enabling direct uploads from 93 professional 3D applications, including all major professional 3D modelling, scanning, sculpting, and texturing software. Additionally, many platforms such as Twitter (X), Facebook, Reddit, LinkedIn, and WordPress natively support Sketchfab, allowing the embedding of the Sketchfab viewer in a social media post via a simple model link.

In 2015, Sketchfab launched its Cultural Heritage Programme, initially led by Nicolas Guinebretière and since 2017 by Thomas Flynn. Sketchfab’s heritage-friendly policy enabled individuals and institutions to share their 3D models with the public and the broader heritage community. Providing a free space that enabled what was previously impossible (at least in a plug-and-play form) also motivated others to join what seemed like a revolution. Not only major institutions, like the British Museum, The Natural History Museum in Vienna, and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, but also other infrastructures, including the biggest aggregator of cultural heritage content, Europeana, were using Sketchfab as a means to present 3D content online [7].

2018 was a critical year for Sketchfab. The platform had over 1 million users and over 2 million 3D models, and many companies had already adopted the platform, its tools, and content. This was considered a good threshold to start monetising the platform’s functionality and content, which in turn would enable the delivery of premium services, including 3D and augmented reality configurations that would speak to the needs of business [8], including some of the biggest industry players, including Audi, Yamaha, and Philips. Moving towards a for-profit model made many of the users, especially from the cultural sector, anxious about the future of the platform and the content they had produced and uploaded models of (see Section 5.3). Although there were some changes at that point, including restrictions to the number of uploads per month, maximum file size, and number of annotations, the basic free version still offered adequate functionality to the average user. Pro and premium accounts that had better features were also given for free to eligible institutions, mostly on the basis of an annual revenue of less than USD 100.000 and having the majority of the 3D models publicly accessible (e.g., not in private mode). Such free accounts were reviewed on a yearly basis to ensure they were still in use and abiding by these conditions.

On the 21st of July 2021, Epic Games [9] made the announcement that “Sketchfab has joined the Epic family games”. In the words of Sketchfab’s CEO, Alban Denoyel, “Joining Epic will enable us to accelerate the development of Sketchfab and our powerful online toolset, all while providing an even greater experience for creators. We are proud to work alongside Epic to build the Metaverse and enable creators to take their work even further”. This is not the first time that a commercial platform embraced by the cultural heritage community was discontinued after being obtained by another company (e.g., the augmented reality company Metaio was obtained by Apple in 2015) or changed their profit model so drastically that it became unaffordable for (small) institutions and non-profit organisations (e.g., Second Life, for which Linden Labs ended educational discounts in 2010). On 29 March 2024, Alban Denoyel, one of Sketchfab’s co-founders, left the company [10].

On 18 September 2024, Sketchfab started sending an email notification to its registered users about Epic’s new digital marketplace, Fab, that would be launching in a month and would replace Sketchfab’s marketplace function. The message highlighted the high revenue share for sellers of 3D models as well as some of the new features that Fab will offer, including “an improved 3D viewer and editor, media galleries, expanded payout options, and the ability to set prices for personal and professional licence tiers” (Sketchfab Support, personal communication, 18 September 2024). A day earlier, Epic Game/Unreal Engine had released an announcement highlighting that it is not only Sketchfab but also other stores and platforms that will be gradually replaced by Fab: the Unreal Engine Marketplace, Quixel, and ArtStation. According to Bill Clifford, Epic’s vice president and general manager for creator marketplaces, “When it comes to selling digital assets, it’s a pretty large total addressable market spread out across a lot of subscale marketplaces. We think the market really needs this single destination” [11]. At the moment of writing this paper, 10 years after the launch of the platform, more than 6 million 3D models have been uploaded, and there are more than 15 million registered users with over 6 million unique visits per month [6].

3. Materials and Methods

In thinking about the development of a new infrastructure that is tailored to the needs of the cultural heritage community, this research combines a literature review and a qualitative thematic analysis of two surveys, a focus group, and community responses to the announced changes to Sketchfab (Figure 1). This section outlines the employed methods and addresses their limitations.

Figure 1.

Paper structure and methodological components.

3.1. Literature Review

The literature review focuses on academic literature that discusses the landscape of 3D cultural heritage, including infrastructures, interfaces, standards for 3D data curation, preservation, and qualitative studies on user experience, and that has been published within the last 15 years; this is to ensure relevance to contemporary technological developments and scholarly discourse. No exclusion criteria were applied to the venue of publication, thus allowing for the inclusion of journals, edited volumes, and conference proceedings, as well as grey literature, such as blog posts, reports, and whitepapers. While the majority of consulted sources were peer-reviewed academic papers, only literature written or translated into English was included due to the authors’ native and working language.

To conduct this literature review, a total of 56 academic works were consulted by searching through academic databases, Google Scholar, institutional repositories, and project websites. Searching included a combination of terms such as “3D cultural heritage”, “3D repositories”, “3D infrastructure”, “3D interface”, “3D web viewer”, “3D scholarship”, “3D paradata”, “digital preservation”, and “sustainability”. Based on this search, six key themes were identified: (1) 3D viewing interfaces, including tools, features, and user experience; (2) metadata and paradata; (3) publication and peer review; (4) research support and community building; (5) intellectual property; and (6) preservation. This literature not only provides a comprehensive overview of challenges and opportunities but also helps us identify the gaps and establish community needs that can inform future infrastructural developments, while providing a theoretical and methodological framework for analysing infrastructure and user requirements. The literature review is by no means exhaustive but aims to address key themes relevant to this study. It may present biases towards more well-documented and known projects as well as literature published in English.

3.2. Qualitative Thematic Analysis

A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted on (1) a survey conducted by Sketchfab in 2019; (2) a survey led by the authors of this article for the PURE3D project in 2021; (3) a focus group on 3D viewing interfaces organised by PURE3D in December 2022; and (4) the community responses to Sketchfab’s announced changes in 2024.

3.2.1. Online Surveys

Survey 1: Sketchfab

The survey was conducted in 2019 by Thomas Flynn while in his role as heritage lead for Sketchfab [12]. This survey was advertised to Sketchfab members who primarily publish heritage 3D models on the Sketchfab platform for use in “public education and/or outreach”. It included questions categorised under six sections: (1) about you and your 3D content (covering demographics, the types of 3D models that respondents produce, and their 3D skills); (2) how you use Sketchfab (addressing the Sketchfab functionalities that respondents most often utilise, including licensing of the models and features that they may be missing); (3) how you create 3D (focusing on hardware and software used as well as on the most common barriers in producing 3D models); (4) metadata (relating to their use, storage, and sharing); and (5) standards and networking (addressing the standards that content creators use as well as the means used to keep up with development in the field and colleagues). The final section allowed respondents to share anything that was not covered by the previous questions. The survey received 142 responses with the majority using photogrammetry as the method of digitisation. The majority of the respondents came from the museum sector, self-identified as archaeologists and researchers, and focused on the use of 3D for public education and outreach.

Survey 2: PURE3D

The survey was conducted in 2021 by the PURE3D project as a means to collect user needs and requirements to inform the development of the PURE3D infrastructure [13]. The survey was conducted digitally and anonymously and distributed through email lists; social media, including Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn; and by means of personally addressed emails. The survey remained open for almost 10 weeks, from 19 May to 25 July 2021. It contained three sections consisting of a total of 47 questions. The first section related to personal and professional demographic information. The second section asked questions about the ideal features, user accessibility, and sustainability of a scholarly 3D web infrastructure. The third and final section provided the option to respondents to answer project-specific questions based on their experiences of developing and disseminating their 3D content and associated research. More than 90 responses were recorded but, due to various levels of incomplete responses, 48 responses were analysed. Of those 48 records, 24 answered the survey section about a specific 3D heritage project. The majority of the respondents were researchers based at universities and research institutes, while their predominant method for producing 3D content was photogrammetry/structure from motion and 3D scanning.

While the two survey datasets had significant overlap in the questions asked, they are complementary as sources of comparison due to the respondent’s differing goals for publishing 3D—from public outreach as the main objective for the Sketchfab respondents to scholarly publishing for the PURE3D survey. It is also important to note that the Sketchfab survey solely focused on the platform’s affordances, while the PURE3D survey aimed at a more general assessment of the 3D scholarly publishing landscape.

3.2.2. Focus Group on 3D Viewing Interfaces

A focus group on 3D viewing interfaces was conducted by the PURE3D project in December 2022 to brainstorm and discuss requirements, features, and functionalities for a new 3D Scholarly Edition authoring and viewing interface that could be integrated into the PURE3D infrastructure. The idea of the focus group was to obtain broad input into a new design through a structured but active approach, utilising design thinking activities to help the participants generate ideas. The focus group consisted of seven participants coming from the fields of digital humanities and heritage. Five have been producing 3D models and been involved in the development of 3D infrastructures, while the other two had broader knowledge of digital humanities infrastructures and have led or been involved in building tools for digital scholarship. The authors led the activities and discussions. After an introductory presentation outlining the purpose of the focus group and the planned activities, participants engaged in four structured exercises. However, since many of these activities focused on brainstorming features specific to the PURE3D infrastructure, this paper will only analyse the responses from the first activity, since they align most closely with the themes covered in the other data sources and provide insights into broader user requirements for 3D viewing interfaces.

The first activity, titled ‘What I Want But Don’t get’ consisted of three parts. Initially, participants were asked to use sticky notes to brainstorm features that they felt were missing in current web-based 3D environments. They were also asked to group these features and to consider their purposes. For example, a feature like ‘first person view’ in a 3D viewing interface could relate to achieving a more immersive environment. In the second part of the activity, participants were asked to reflect on features highlighted in the PURE3D survey (see Section 3.2.1 and Section 5.1) and incorporate any additional ideas into their brainstorming. Finally, participants compiled a priority list of features using three categories: must have, should have, and might have.

3.2.3. Community Responses on Social Media

Scholars and professionals working with 3D cultural heritage actively used social media to express their concerns regarding the announced transition from Sketchfab to Fab. To capture these responses, the authors monitored various platforms, namely X (formerly Twitter), LinkedIn, Reddit, and Discord. In addition, comments posted on a publicly accessible Google Doc initiated by Thomas Flynn, formerly Heritage Lead at Sketchfab, were reviewed. This document collected users’ frustrations as well as suggestions for free and commercial Sketchfab alternatives. Comments from an online petition against the potential closure of Sketchfab on Change.org were also included in the analysis. Given the relatively small amount of content produced across these platforms, computational tools for extraction or analysis were not deemed necessary. The data collection spanned from September to December 2024, with the majority of content generated in September and October, coinciding with the initial Sketchfab announcement and updates as well as users’ heightened concern. The collected content was thematically analysed under four categories: anticipated disappointment; loss of community features; accessibility and institutional support; and technical shortcomings and migration concerns.

3.2.4. Ethical Considerations and Data Limitations

The authors of this paper acknowledge that using social media comments as research data poses certain ethical considerations, especially regarding informed consent, privacy, and anonymity. To address these concerns, several measures were taken to ensure the ethical use of these data. Firstly, all comments analysed in this study were publicly available under the commentators’ usernames. These usernames varied: some were real names, some were pseudonyms, and some were not easily identifiable, e.g., in cases where only the first name was used. In quoting comments, the authors retained the original names or usernames as a way to publicly acknowledge the contributors’ insights and perspectives. Secondly, care was taken to only include quotes that provide critical insights into community perspectives regarding Sketchfab’s transition and its implications for 3D heritage practices. The selected quotes reflect professional opinions or general frustrations rather than personal or private matters, while comments that were considered sensitive were omitted. Lastly, as an additional precaution, all individuals whose comments were included in the paper and who could be identified or contacted were asked to give their permission for us to quote them and include their (user)names.

In addition to the ethical considerations outlined above, this study also acknowledges limitations in the scope and representativeness of data. A significant limitation is that input from end-users, particularly members of the general public, is lacking. Despite a few exceptions [14,15,16], it is only creators, researchers, and professionals who are typically consulted regarding their needs and preferences, often overlooking those who consume 3D content for education, leisure, or cultural purposes. This gap leaves unanswered questions about what the public values in 3D heritage platforms, how their affordances shape their experience, how they use any available tools, and what features may be missing. The absence of this demographic in this research and in much of the referenced literature underscores a critical lacuna: the need to understand the expectations of the general public compared to the requirements of researchers and professionals. Future studies could focus more on engaging with this wider audience to develop tools, services, and infrastructures that are more inclusive and are better suited to the diverse needs of users.

4. Literature Review: Challenges and Opportunities in Developing Sustainable 3D Cultural Heritage Infrastructures

In 2010, Koller, Frishcher, and Humphreys [17] argued for the establishment of a centralised open repository in which the research and heritage communities could publish, peer review, update, and disseminate scholarship in 3D. Their observations were based on a number of surveys conducted online and at professional meetings. As a result of the feedback, they outlined research challenges that such a repository needed to address, including issues of digital rights management, clear communication of uncertainty and associated metadata, versioning, preservation, and interoperability [17]. More than a decade later, many 3D working groups and researchers are making similar arguments. For example, the EU-funded project Pooling Activities, Resources and Tools for Heritage E-research Networking, Optimization and Synergies (PARTHENOS) highlighted the complexity of 3D data preservation and publishing for the heritage domain [18,19], while the US-based project Developing Library Strategy for 3D and Virtual Reality Collection Development and Reuse (LIB3DVR) gathered perspectives from a variety of disciplinary experts and identified similar issues for accommodating the diversity of needs and requirements for 3D scholarship [20]. Both groups focused on the challenges for synchronising 3D standards and research workflows across national and international organisations (e.g., university libraries, museums, etc.). These working groups and other 3D data scholars mentioned in the review below reiterate and expand upon what Koller et al. [17] identified early on as a variety of interdependent components that are necessary to constitute a useful and usable centralised 3D heritage research infrastructure.

4.1. Three-Dimensional Viewing Interfaces: Tools, Features, and User Experiences

The 3D web viewer is an integral component of 3D infrastructures. Three-dimensional viewers with plain visualisation functionality (e.g., zoom, rotate, pan) tend to be sufficient for users who consume 3D for enjoyment [21,22]. However, a survey of existing 3D depositories, repositories, archives, and web portals conducted by Champion and Rahaman [23] revealed a general lack of “useful features in the scholarly field of 3D digital heritage” (p. 13). Also recognising this trend in 3D viewing environments of 3D CH material, M’Darhri et al. [19] recommended a list of desirable 3D viewer features that would accommodate what they refer to as ‘publishing’ criteria that would enable 3D content to be utilised as a legitimate research resource. These include more robust analytical tools, such as measuring tape, slice tools, dynamic lighting, integrated screenshots, and different rendering views [14,18,24]; in-world semantic enrichment, such as hotspot annotation, embedded multimedia resources, guiding narratives, timeline capabilities, and removing/adding parts of the 3D model at the scale of the component, area, or layers [15,18,25,26,27]; and immersive functionalities, such as photorealistic rendering and lighting, first-person viewing perspective and navigation paradigms, the ability to interact or change the 3D scene, and real-world physics [24,25,28,29,30]. According to Münster [22], there seems to be an increasing emphasis on photorealism; however, this should always be tailored to specific use cases.

Within the digital heritage field, there has been some development of open-source 3D viewing frameworks incorporated into project websites, web platforms, repositories and infrastructures which seek to include some of the ‘publishing’ features mentioned above. Dynamic Collections Plus [31,32], for example, is a 3D research web infrastructure from Lund University utilising a customised 3DHOP viewer [33]—a 3D viewing framework developed by the Visual Computing Lab, CNR-ISTI (National Research Council of Italy—Institute of Information Science and Technologies “Alessandro Faedo”). Built for higher education and research of archaeological artefacts, Dynamic Collections Plus exemplifies the current state of applying 3D analytical tools and diverse forms of semantic annotation for the material analysis of digitised heritage research collections. In addition to the capabilities for slicing, measuring, and adjusting the rendering material and dynamic lighting, the platform allows one to create and export their own annotations at the level of the overall object, XYZ points on the object, and customised scene states which can record any of the analytical tools. Another example is that of the Voyager Framework [34] developed by the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office as a means of visualising and disseminating 3D digitised objects from their many museum collections. While Voyager includes some analytical features (e.g., a slice tool, a measurement tool, different rendering views), the emphasis of the framework is on linear and non-linear storytelling in and around the 3D object that can be customised using the back-end authoring interface, Voyager Story. The Voyager Framework has been incorporated into other heritage-based research platforms and infrastructures, such as the PURE3D Infrastructure, the 3D Workspace from the 4D Research Lab at The University of Amsterdam [35], and the eCorpus hosting platform from the eThesaurus Consortium. For alternatives to single, digitised objects, the ATON Framework [30], developed by the Virtual Heritage Lab, CNR-ISPC (National Research Council of Italy—Institute of Heritage Science), is designed to accommodate heritage projects with more complex (re)constructed scenes with a set of features that focus primarily on immersive experiences, navigation, and scene manipulation in virtual environments. An additional feature of ATON is its capability for real-time collaboration between multiple users using a number of different viewing devices, including desktops, phones, and tablets, while supporting extended reality via virtual reality headsets.

While the 3D viewing environment is a key component for user experience, the entire platform’s usability and user experience are also important aspects of 3D web infrastructures. Champion [36] warns that “a digital humanities infrastructure will not survive for long if it does not create effective synergies between equipment and people” (p. 61). Platform users include not just end-users who engage with the 3D content but also the 3D content creators and/or authors. Potenziani et al. [28] recognise that 3D infrastructures need to account for a variability in the technical background of both user groups, suggesting that simple UI and UX features and easy-to-handle tools are necessary for platform success. This is further emphasised by Maryl et al. [37], who stress the need to incorporate user-centred research in platform design. Huurdeman and Piccoli [29], referring to Joris van Zundert’s [38] generalisation paradox, point out the tension between creating a limited set of standard features that appeal to a wide range of uses and providing a tool that is useful for specific research purposes. On the other hand, they recognise the pitfalls in overloading the 3D viewing experience with a complex interface that can result in increased cognitive load and user frustration. To combat this tendency for interface maximalism, they prototyped a 3D viewing framework called Virtual Interiors with “a standard, lightweight set of features, which can be extended for use in different contexts” [29] (p. 330). These include a suite of features segmented in three layers within the user interface: (1) viewing experience by means of real-time exploration via orbit navigation or first-person perspective; (2) interpretation via linked open data, alternative hypotheses, a certainty index, and the manipulation of objects in the scene; (3) authoring through user-based textual annotation. Ultimately, the suite of advanced features, tools, and the end-user experience for 3D research platforms are determined by a number of factors, including the type of 3D model (e.g., digitised, single object vs. complex (re)constructed scenes); type of heritage object represented in 3D (e.g., artefact, monument, excavation site, building, landscape, etc.); disciplinary (sub)field, each with its own terminologies and methodological approaches (e.g., archaeology, architecture, history, art history); and the target audience (e.g., general public, university students, researchers, conservators, public sector).

However, in order for these advanced tools and features to be effectively utilised for scientific analysis and interpretation, the 3D model itself needs to be optimised for the web as well as correctly placed into the chosen 3D viewer. In an analysis of heritage models published by museums on the Sketchfab platform, Hernández-Muñoz [39] noted that many models were not correctly optimised for efficient visualisation and downloading. He observed a variety of phenomena, such as an excessive number of polygons in some cases or not enough polygons in other cases. In the case of lower polygon counts, the use of texture maps to establish material characteristics was not frequently applied as a means of compensating for the critical details that might disappear when optimising the model’s geometry. In addition to model adjustments, the further customisation of settings often needs to be made once the 3D model is imported to the web viewer. For example, in our exploration of existing 3D research platforms that make use of measurement and slice tools, we observed that, in some cases, the scale of the 3D object was not accurate to its real-world equivalent nor was the model properly oriented to the XYZ axis. Quality control for such cases may not be critical for the casual consumption of 3D models, but it may be necessary for research use cases, where these optimisation aspects are crucial, e.g., for material analysis.

4.2. Metadata and Paradata

There is general agreement that any kind of 3D research platform that onboards a large amount of diverse 3D content should, at a bare minimum, have clear and consistent metadata, with each object assigned a globally unique and persistent identifier registered in a searchable resource [40]. Metadata filters are especially necessary for large 3D repositories as one can refine their search for digital assets by a variety of topics, such as object type, region, time period, and material. Moore et al. [41] outline a roadmap for community standards of 3D data, taking into consideration the interdependencies of access, audience, and methodologies of 3D model creation. Likewise, Hardesty et al. [20] view these communities in terms of the research lifecycle of 3D and virtual reality outputs—from creation by 3D modellers to online preservation in hosting institutions and to the means of access by intended audiences and disciplinary expertise. These authors recognise that the inherently shifting nature of the needs and requirements of these various communities means there is likely no single, universal guideline that can be applied to 3D data. Münster [22] on the other hand, highlights that although CIDOC CRM has become a standard for heritage documentation, it is not widely or uniformly implemented. Therefore, given the inconsistencies in capturing and applying metadata standards, it may be critical to improve automated processes for metadata generation.

Another feature of 3D repositories should be the possibility of linking paradata, i.e., the documentation of the decision-making process in creating a 3D model [42], which would enable researchers not involved in the project to evaluate its creation [24] and facilitate reuse. A recently edited volume by Ioannides et al. [43] focuses on the documentation and application of paradata for a variety of 3D heritage applications—from digital twins of existing heritage artefacts, remains, and landscapes to hypothetical (re)constructions and Heritage Building Information Modelling. The diversity of these papers and the many bespoke solutions presented by the authors [44,45,46,47,48] reflect the depth and breadth of the creation and use communities mentioned above, reinforcing the notion that there is not a one-size-fits-all for 3D metadata, let alone paradata. As Huvila [49] argues in the same volume, the problem is not so much the lack of technical standards for representing paradata, since some already exist, but the “lack of social and cultural standards…of what is required for the transparency of many of the predominant cultural artefacts of the contemporary information sphere…” (p. 8).

Statham [50] recommends the disentanglement of the viewing environment and the data that accompany the 3D model, suggesting that the full set of specialised data should be stored separately—whether in a single downloadable file or folder or embedded within the website on which the 3D viewer is hosted—in a machine-readable format outside of the 3D viewing interface. This enhances the sustainability of the digital resource, accommodating a scenario whereby the viewing interface or platform is no longer supported but the crucial information relating to that digital resource is accessible for an indefinite duration [23].

4.3. Publication and Peer Review

Citation standards and peer review are also frequently mentioned as key for access and reuse. However, the nature of citing 3D content is not straightforward as it is not always clear what aspect of the compound object is being referenced: the geometry, metadata for the physical object, or the metadata or paradata for the digital object [51]. In an ideal scenario, there would be a consistent format for citation that can accommodate the various levels of data, each one assigned a globally unique ID or DOI at the individual item level as well as at the level of the entire data package [24]. Another aspect of citation standards for 3D infrastructure is the accommodation of multiple versions of a 3D project. Koller et al. [17] suggest that 3D version control conventions can be adapted from software development methods in order to track additions, deletions, and modifications of 3D models based on alternative, new, or updated insights and discoveries. Hardesty et al. [20] point out that versioning of 3D data is also necessary when converted or optimised for different modalities and audiences, for example, a 2D rendering, a web-based visualisation, and offline gaming engines.

The literature consistently recommends that 3D infrastructures facilitate peer review to allow the 3D asset and its data to be validated as a legitimate scholarly resource [17,23,51,52]. Advocates for a formal peer review process argue that this is essential not only for secondary use and long-term sustainability of the 3D asset [24,26,51] but also for academic valorisation and recognition of the 3D work as a scholarly output [20]. While peer review is mentioned as a necessity for 3D evaluation, few authors offer concrete recommendations on how to structure the process. Sullivan and Snyder [25] lay out a roadmap for 3D peer review, providing suggestions on how to overcome the technical, procedural, and conceptual obstacles of integrating 3D into existing publishing mechanisms. These include technical measures that ensure evaluation takes place based on the interactive experience of the content in its native format as well as decoupling the technical software requirements and limitations from the publishing house in order to accommodate the variety of 3D file formats and creation workflows. Procedural aspects concern finding relevant technical and subject experts that have the necessary knowledge and skills to provide useful feedback. Finally, they question the concept of ‘revise and resubmit’ that is typical for text-based scholarship. This is because a 3D publication consists of multiple components, including the 3D model, the accompanying information and multimedia assets, the viewing interface, academic arguments, and interpretive information. Sullivan and Snyder [25] therefore suggest that given the complexity of a 3D publication, it is only the arguments and interpretations that are easily modifiable to respond to reviewer comments.

4.4. Research Support and Community Building

Research support and platform community-building are also mentioned as underappreciated yet necessary aspects of user adoption of digital research infrastructures [53]. Research support features can include many elements, including the ability to download 3D data and to understand licensing information, versioning, paradata, and citation guidelines at various levels of 3D data. However, it can also include aid for dynamic research workflows which can occur via the platform, such as synchronous and asynchronous collaboration tools for project teams [30,54], creating and exporting user-based annotation [29,55], and the ability to create a personalised digital workspace via user profiles [31].

With regard to community features, Statham [50], based on her observations and analysis of three popular 3D heritage platforms, namely Sketchfab, CyArk, and Google Arts and Culture (GAC), recognises the value of active user participation for creating meaning and value around cultural heritage and practice. Through a comparison of the three platforms, she identifies that platforms with higher community participation, e.g., Sketchfab, on the one hand, tend to have lower control over how 3D authors’ content is used as well as lower scientific rigour—as any user can become a 3D author without screening for model quality or authenticity. On the other hand, this participatory approach creates shared community engagement by enabling platform users to interact by marking model favourites, creating personal collections, following creators, making comments, and sharing content in other platforms through embed APIs. However, she recommends these be cautiously implemented, using tools and protocols for moderation to minimize spammers and trolls. Conversely, platforms with more control over content management and model reuse, e.g., GAC and CyArk, and thus with lower community engagement, result in users becoming passive consumers.

4.5. Intellectual Property

Another affordance discussed in the literature is the need for mechanisms to manage intellectual property rights (IPR). Concerns about IPR in 3D digitisation are often centred on the potential loss of control over virtual representations, including risks of misrepresentation as well as improper commercial usage [17]. In cases where physical and digital ownership of heritage remains involve ethical and/or cultural entanglements, data use agreements have been suggested [56] as a way to guide access, distribution, and dissemination [26]. The literature highlights the need for flexible copyright systems [20] that allow 3D owners to apply various levels and configurations of licensing and download permissions of 3D models and associated data based on their specific needs. Such systems could provide varying levels of access while addressing concerns about misuse or misrepresentation. However, it should be noted that intellectual property for digitised cultural heritage, particularly in the context of 3D models, remains a grey area, since there is still no universal agreement on ownership and rights management [57,58,59]. This complexity is amplified by the diversity of stakeholders involved, including creators, institutions, and communities, each with their own priorities and concerns. Given such complexities, intellectual property rights are not only a legal or procedural matter but one that needs to be carefully considered by future 3D infrastructures, taking into account the idiosyncrasies surrounding cultural heritage objects and the institutional frameworks within which these objects are managed.

4.6. Preservation

Another critical issue associated with 3D platforms and infrastructures is the long-term preservation of 3D models. Due to inconsistencies in 3D standards for interoperability, many acknowledge the irony of spending effort and money to digitise heritage remains when the digital version’s half-life is much shorter than its physical counterpart [17,24]. Preservation strategies for 3D content need to address not only the technical challenges for maintaining 3D models and associated metadata but also the broader infrastructural and governance frameworks required to ensure their sustainability.

Hardesty et al. [20] recommend storing an original-resolution version of the model in a data archive while also publishing a web version that is more flexible and lightweight for online distribution and accessibility. To reduce dependencies on specific hardware and software, they suggest making 3D models available in multiple formats and avoiding proprietary formats. Clarke [56] also argues that once a digital content has been published in an infrastructure, its maintenance should be the responsibility of the preservation service and not of the original owner. Champion [36] emphasises that hosting platforms should support 3D file conversion, reformatting and exporting from one format into another, to anticipate rapid technological changes in which 3D modelling software and 3D web viewers are no longer able to read obsolete 3D formats. In the case of 3D models generated using the cost-effective photogrammetry/structure-from-motion method, the original image dataset can also be made available. This can be beneficial for two scenarios: (1) in the case of loss of the 3D model due to file format obsolescence and/or (2) technological advancements in which re-processing the image dataset yields a more accurate 3D representation than the initial version [60]. The Dynamic Collections Plus [32] platform practically models some of these 3D data preservation recommendations. For each 3D record, a DOI is assigned and enables a connection to an external online data archive, such as Zenodo or other trusted repository, where the raw image data, the 3D files, and other relevant information are stored and made accessible for download [61,62]. This connection to externally stored data as facilitated by the infrastructure can also be repurposed for paradata in the case of (re)constructed models [50]. However, an increasing number of studies highlight that the environmental impact of digital preservation should be taken into consideration, e.g., when making decisions about the long-term storage of raw data [63,64].

Experts envision digital research infrastructures as non-commercial, open access, and user-centred as essential for ensuring sustainability [38,65]. Financial sustainability is a key challenge, with solutions such as cloud-based storage systems, distributed storage networks, data compression techniques, and streaming protocols being proposed to mitigate costs [66,67]. The Principles of Open Scholarly Infrastructure (POSI) [65] provide a valuable framework for dealing with such challenges. POSI emphasises governance structures that are transparent and stakeholder-driven, while ensuring sustainability through different revenue streams. Of particular relevance is POSI’s concept of “living will”, which outlines a coherent plan about how an infrastructure should handle its assets if it is wound down. This ensures that assets are archived and transferred to a successor organisation that adheres to similar principles [65]. Such mechanisms build trust among users by demonstrating commitment to continuity and preservation. This is particularly pertinent to the case of Sketchfab since concerns have arisen regarding the long-term accessibility of heritage 3D models hosted on the platform, mirroring both a lack of clear commitment to preservation and broader concerns about the suitability of commercial solutions.

4.7. Conclusions

This literature review, which is by no means exhaustive, addresses core issues of 3D infrastructures, including metadata and paradata standards, publication and peer review, intellectual property, and community participation, emphasising the need for open, user-centred, and sustainable infrastructure for 3D cultural heritage assets. The importance of 3D web viewing interfaces is a recurring theme in the reviewed literature as a fundamental part of such infrastructures. In addition to enabling online and interactive viewing of 3D models by means of, e.g., zooming in/out, rotating, etc., 3D viewers need to accommodate more complex features, including annotation, dynamic lighting, semantic enrichment, and more immersive experiences; such features are necessary not only for the research community but also for novice users. However, there seems to be a conflict over 3D interfaces tailored to the specialised needs of certain communities, e.g., academia, over more generic and lightweight tools that would appeal to a broader audience. There is agreement, however, that given the ingrained complexity of 3D infrastructures, the UI and UX should not add to their complexity but enable a smooth experience for the intended audience. In order to further explore the needs, expectations, and difficulties faced by the 3D cultural heritage community, the following sections analyse data from two surveys that were conducted by Sketchfab and PURE3D as well as a focus group conducted by the PURE3D team. This analysis enhances the insights from the literature review by offering a more thorough account of user requirements for the development of 3D infrastructures.

5. Results

5.1. Analysis of Sketchfab and PURE3D Surveys

Building on the themes identified in the literature review, this section analyses two surveys, providing insights into the needs, preferences, and challenges faced by the cultural heritage community. While the survey by Sketchfab focuses on user engagement with an established commercial platform, the PURE3D survey gauges the ideal features of a scholarly 3D infrastructure. This survey was conducted at the beginning of the PURE3D project in 2021 to better inform the design of a new national Dutch infrastructure for the publication and preservation of 3D scholarship. By combining insights in how 3D practitioners and scholars interact with an existing platform and how they envision the future of such infrastructures, this section examines key topics, such as 3D viewer features, annotation, licensing, quality assessment, and long-term preservation, thus deepening our understanding of user requirements while highlighting areas where current solutions fall short.

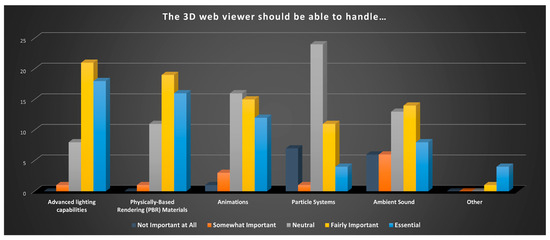

5.1.1. Three-Dimensional Viewer Features

In terms of functionality related to the 3D viewing interface and experience therein, some insights can be derived from both surveys. The majority of Sketchfab users take value from appearance-enhancing features, including post-processing effects and physically based rendering, while annotation is also a feature that is used often or sometimes (see Section 5.1.2). On the other hand, there is less of a need or desire for dynamic forms of presentation, for example, animation and audio. Although analytical features, such as measurements and cross-sections, are not supported by Sketchfab, these were included in the responses about additional functionality that users would be interested in. Overall, the ability to display the model with contextual information was deemed the third most important feature of 3D models uploaded to Sketchfab. The PURE3D survey asked specifically about features of an ideal 3D viewer. Respondents ranked functionality related to model appearance as well as in-viewer analytical features highly. For example, features such as physically based rendering (PBR) materials and advanced lighting came out to the top of the list of preferred functionalities, followed by animation and ambient sound (Figure 2). Analytical and dynamic features were also ranked highly, which is reasonable given the audience of the target audience of the PURE3D survey. Features such as measurement and cross-section tools as well as enabling/disabling parts of a 3D scene were considered essential or fairly important. A timeline and the ability to capture screenshots were also considered fairly important.

Figure 2.

PURE3D survey: responses to the question ‘The 3D web viewer should be able to handle…’.

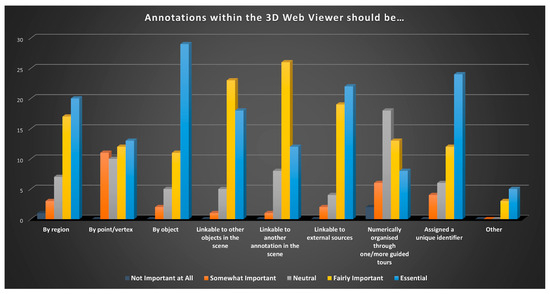

5.1.2. Annotation

Both survey results include responses that reflect the sentiments regarding the annotation of 3D models. While the Sketchfab survey only indirectly collected data about the semantic enrichment of 3D models (i.e., the addition of metadata that enhance context and relationships under the wider question about frequently used features), the PURE3D survey gathered more granular data, considering annotation to be an integral aspect of a scholarly 3D infrastructure. More specifically, according to the Sketchfab survey respondents, the hotspot annotation feature was less frequently used (ranked 7th out of 18 features) than other forms of semantic enrichment, such as descriptions, tags, and categories. These three features were the top ranked functionalities, indicating a preference for features that increase the findability of 3D models and provide connections to those uploaded by other members of the Sketchfab community.

Responses to the PURE3D survey (Figure 3) indicated a preference for annotations to be designated firstly by object and secondly by region, as opposed to a singular point or vertex, which was also ranked highly. The responses to this question also provide insight as to the interlinking of annotations, with the majority of respondents preferring a possibility to link an annotation to external sources, followed closely by the ability to link annotations to other objects or annotations in the same 3D environment. Regarding the referencing and discovery of these annotations, there was a preference that annotations receive a unique ID. The ability to add annotations by multiple contributors as well as users not involved in the creation of the 3D models were also considered fairly important functions (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

PURE3D survey: responses to the question ‘Annotations within the 3D Web Viewer should be…’.

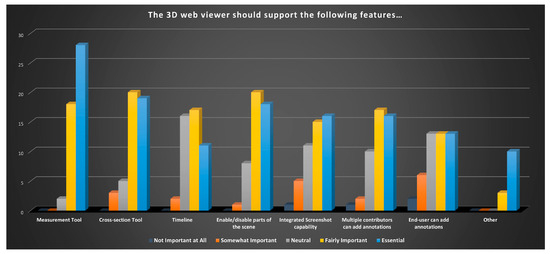

Figure 4.

PURE3D survey: responses to the question ‘The 3D web viewer should support the following features…’.

5.1.3. Community and Collaborative Features

Both surveys highlighted the importance of collaborative and community-oriented features in enhancing the reach and impact of 3D within the cultural heritage community. These features not only foster engagement but also enable the development of meaningful interactive resources that are of benefit to both individual creators and cultural heritage institutions.

On the one hand, Sketchfab users often utilise functionalities such as descriptions, tags, and categories, as well as social media sharing and embedding functions to make their models more findable. These features allow the development of a community around their work, increasing model visibility and facilitating reuse. As recent responses on social media regarding the transition from Sketchfab to Fab reveal, such community features have also been instrumental for Sketchfab users in receiving recognition for their effort in digitising cultural heritage. For institutions, these tools provide a means to measure the impact of their digitisation projects and justify the resources invested in creating 3D collections (see Section 5.3.2).

The PURE3D survey similarly underscored the value of such features for end-users of 3D content. A significant majority of respondents expressed interest in functionalities such as liking or following projects and the ability to comment on them. However, over half of the respondents indicated that such interactions—along with downloading content—should be restricted to users who have created a profile on the platform. This reflects a desire for accountability and control over user interactions. Regarding public comments, many respondents indicated the need for solid mechanisms for filtering and moderation. As a result, private commenting seemed to be preferred over public discussion. These responses suggest that although 3D model creators appreciate interactions with end-users, they are careful about relinquishing control over how their projects are publicly discussed.

5.1.4. Ownership, Licensing, and Citation Standards

The topic of 3D data reuse was addressed in both the Sketchfab and the PURE3D surveys, offering insights into the values and preferences around ownership and licensing within the cultural heritage community.

In the Sketchfab survey, over half of the respondents indicated that they offer their 3D models for download under a variety of Creative Commons licences, with ‘Non-commercial’ and ‘Just Attribution’ being the most commonly used. However, almost half of the respondents chose not to make their models downloadable, citing various reasons. A significant concern was the lack of control over how their content might be reused. Other reasons included copyright restrictions, e.g., in cases where an institution owned the copyright, as well as the cultural sensitivity of certain models.

As a result, some respondents suggested alternatives, such as keeping the models private and making them available on demand. As one of the respondents explained, “...our institution needs to know who and for what data is use[d] for our statistics, funding…and database”. Commercial licensing was largely absent from respondents’ considerations. This was attributed to institutional policies for open licensing, copyright, ethical concerns over the monetisation of cultural heritage, and bureaucracy related to receiving payments and generating revenue, as well as concerns over potential misuse.

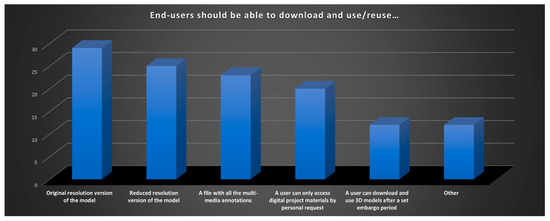

Similarly, the PURE3D survey explored conditions for downloading and reusing content (Figure 5). Both quantitative data and open-ended responses suggested that scholarly content creators prefer flexible solutions that allow authors or owners to control which parts of a 3D dataset are available for public download and re-use under a variety of CC licences. For example, some respondents indicated a preference for providing access to low-resolution versions, while a higher number suggested that access to the original resolution is preferred. Others emphasised the importance of allowing access to the multimedia annotations accompanying a file. Given this complexity, embargo periods and access by request were suggested as potential solutions. Providing licensing information so that end-users know the exact terms and conditions of using 3D models was deemed an essential feature of 3D infrastructures. One respondent summarised this need for flexibility: “a robust system should be able to accommodate all of those scenarios, depending on the content and its community of origin”. The survey also highlighted the importance of providing clear citation instructions. Respondents expressed a need for consistent citation standards that accommodate different levels of 3D data (e.g., through unique IDs for annotations) and ensure proper attribution. The inclusion of DOIs for 3D models was considered an essential feature to facilitate proper referencing and long-term discoverability.

Figure 5.

PURE3D survey: responses to the question ‘End-users should be able to download and use/reuse…’.

The findings from both surveys reflect the complexity of ownership and licensing in digital heritage. They underscore that 3D datasets often involve multiple stakeholders, who may have diverse and often conflicting concerns over how content is shared, (re)used, and protected.

5.1.5. Metadata, Quality Assessment, and Discoverability

While Sketchfab does not collect or require metadata for 3D content uploaded to the platform, this topic was highlighted in the Sketchfab survey. For the survey respondents, metadata equated to what we previously described as 3D paradata, including raw datasets; capture or creation details; software project files; and processing, editing, and conversion workflows. Responses revealed that while many users collect a variety of metadata and paradata, these are infrequently linked to the Sketchfab 3D model; only a small number of respondents indicated that they include such information in the model description or as a textual annotation. Respondents also indicated that they store metadata in offline databases and spreadsheets, with only a small percentage making these available through online databases. Regarding quality assurance or standards used in 3D production, the vast majority of responses underscored that either they use no formal standards or that they follow their own. PURE3D respondents also highlighted the importance of robust search functionalities. Search tools that enable filtering based on metadata fields, e.g., region, time period, material, etc., and user-defined criteria were considered essential for improving the models’ discoverability.

PURE3D survey participants were asked whether 3D projects should be peer-reviewed as a condition for publication on a scholarly 3D platform. Their responses were almost evenly mixed between ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘other’. Many of those who selected ‘other’ provided input that suggests that 3D authors value a flexible system which would allow them to decide if they want their 3D work to be peer-reviewed or not. The following comment encapsulates the overall sentiment: “I would love for this [peer review] to be an option, and to make it possible to search only peer-reviewed models. I would not want that to be the only way to upload and share, especially given the turnaround time for peer-review”.

5.1.6. Long-Term Preservation

While the topic of preservation was not touched upon in the Sketchfab survey, it was emphasised in the PURE3D survey through questions that probed for participants’ expectations for long-term care. In terms of expectations of a free and open-source platform’s commitment for supporting 3D data, the majority responded that they expect it to be maintained for the entire duration of the platform’s existence, with the second most popular answer being that models should be maintained for more than 10 years.

Regarding the cost of maintenance, responses revealed that the majority of participants would consider including a portion of the project funds for long-term maintenance, and that they would prefer either a single, upfront fee or a yearly subscription model. One-fifth of the respondents indicated that although they would not be willing to pay for maintenance, they expressed willingness to update the models to future standards if prompted by the platform. As was the case with similar questions, open-ended answers underscored that users would like a more nuanced and flexible approach to maintenance costs. Many used the phrase “depends on the cost” with some further suggestions, including a paid tier for longer-term storage and hosting, pay per view, or a donation model.

5.2. Analysis of Focus Group on 3D Viewing Interfaces

The focus group aimed to gather user requirements for features and functionalities in a 3D Scholarly Edition authoring and viewing interface that could be integrated into the PURE3D infrastructure. While the focus group covered a wide range of topics, this section discusses the findings most relevant to the themes highlighted in previous sections, particularly those related to 3D viewing interfaces. The first activity, titled ‘What I Want but I Don’t Get’, asked participants to brainstorm features missing in current 3D interfaces and to rank them in a priority list. The following part reflects their preferences in descending order of importance.

Annotation was a key area of discussion. Participants emphasised the importance of flexible annotation tools that would support, among others, collaborative annotation, similarly to how Google Docs function, allowing multiple users to contribute. They also suggested linking annotations to external sources or other annotations within the same 3D environment and associating them to specific coordinates within the model, thus allowing for more granular contextualisation. Disentangling annotations from the interface where the 3D models are viewed, e.g., by being able to export annotations in different formats, was also considered critical, particularly given the lack of interoperability commonly observed in such infrastructures. Mechanisms for the proper attribution and citation of 3D models were also deemed essential. Participants proposed assigning unique identifiers (e.g., DOIs) to models and their components, along with providing clear instructions on how to cite 3D models or their elements (e.g., annotations) in scholarly works. The ability to assign micro-level unique identifiers to specific parts of models was considered necessary for ensuring precise attribution but also for enabling complex queries.

One of the most prominent themes that emerged was the need for analytical tools. Participants expressed a desire for both basic and advanced functionalities to conduct qualitative and quantitative studies based on the 3D models. Basic features such as measurement tools for dimensions and distances were proposed. On the other hand, advanced tools for sound modelling, light simulation, and morphological and structural analysis were also suggested. In addition, participants indicated that tools for comparison are largely missing; therefore, tools that would provide the ability to compare the morphology of multiple 3D models side by side were deemed desirable. The focus group also highlighted the need for better integration of paradata and provenance information. Features including the linking of annotations and metadata directly to source data, e.g., through Linked Open Data, and the development of tools to represent uncertainty at a granular level were proposed. Also, given the complexity of paradata, in terms of both documentation and consumption, participants proposed the inclusion of audio clips to narrate paradata, making it more accessible to creators and end-users.

Immersion was another topic discussed during the focus group. Participants expressed interest in a first-person view—commonly used in video games and other immersive environments but often lacking in 3D viewing interfaces for cultural heritage—as well as support for virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and extended reality (XR). These immersive features were seen as increasingly relevant given their growing affordability and accessibility, integration into research and education, and potential applications in the cultural heritage field. Interoperability across platforms, file formats, and software was a recurring theme throughout the discussion. Participants highlighted the need for supporting multiple file formats with minimal conversion requirements, controlled vocabularies and ontologies for metadata and paradata, and interoperability between different viewers and platforms. This was considered particularly important given past challenges with bespoke 3D interfaces, which resulted in hardcoded functions and content, data loss when project funding ended, or tools that were incompatible with each other.

Ease of use was also identified as critical, particularly for people not necessarily familiar with 3D technologies and who may lack technical expertise, e.g., curators of cultural heritage institutions. For this reason, participants emphasised the need for the seamless integration of multimedia with 3D models to create intuitive connections between the 3D model and other types of content as well as a user-friendly interface that would simplify workflows without sacrificing functionality overall. To this end, training material tailored to the needs of different stakeholders should also be provided. Another significant requirement identified by participants was version control systems that capture changes not only in 3D models but also in their associated elements, such as annotations. They also suggested that versioning should extend to 3D viewing environments, as newer versions may introduce different affordances from those originally used. This information is critical for understanding the context of digital object creation. Lastly, participants highlighted the importance of export functions for different types of data. They suggested functionalities that would allow users to export not only 3D models but also textual or multimedial annotations as well as query results. These features would allow the reuse of metadata, paradata, or other types of content across different contexts.

5.3. Analysis of Community Responses to Sketchfab’s Transition: Concerns, Frustrations, and Valued Features

Scholars and professionals working with 3D for cultural heritage quickly reacted to the announced changes regarding Sketchfab. Social media platforms, including X (formerly Twitter), LinkedIn, Reddit, and Discord, became fora where concerns and frustrations were voiced. At the same time, users highlighted the platform’s affordances that made it the ‘go-to’ resource for hosting and sharing heritage 3D models. This section analyses comments from creators of cultural heritage content on these platforms, organising them under four broad themes: anticipated disappointment; loss of community features; accessibility and institutional support; and technical shortcomings and migration concerns.

5.3.1. Anticipated Disappointment

Many Sketchfab users expressed frustration over the potential loss of their work, while suggesting that this outcome was not entirely unexpected. While recognising the risks of relying on a commercial platform, Sketchfab had often been perceived as the only viable option for their needs. Users who have integrated Sketchfab into their research, teaching, or public dissemination projects acknowledged that the platform’s demise had always been a looming possibility, which became more likely after Sketchfab’s acquisition by Epic Games, a company with a different target audience, funding model, and strategic priorities. The popularity of the platform in the cultural heritage field was the result of not only its affordability and user-friendly interface but also of how users had misused it to serve as a de facto repository, even though it was never designed for this purpose. In essence, users often overlooked the platform’s primary function as a marketplace in favour of its 3D web viewing capabilities. This may also highlight a broader issue in the cultural heritage community: a preference for platforms that prioritise 3D viewing over infrastructures that can provide data management and archiving solutions. Although this may be partly connected to a gap in 3D literacy among producers and users of 3D content, it may also stem from the lack of standardised practices in the field. Lastly, it is worth noting that some members of the community saw this change as an opportunity to rethink how 3D heritage is stored and presented online. The following remarks provide insight into these views:

“We knew this was coming…and I’m terrified for my big national park service project that depends on Sketchfab API…and I had zero options besides sketchfab”[68]

“We’ve always known that this was a possibility right from the beginning, it was a presentation layer and not a preservation system. There’s not many options, but if the tech for the viewer was open sourced, things might pan out on distributed platforms. Sad, but foreseeable.”[69]

“I suspect creating/supporting a 3D archive for objects would be a good task for a University or govt agency…but money is, of course, the major problem. I suppose something like the Internet Archive but for objects is what is needed.”[70]

“Regardless of the outcome over the coming months/years, I think this is a really good opportunity for the heritage community to find/build/rally around an online 3D storage and display solution that it has more/full control over… while still using Sketchfab/Fab if they want:)”[71]

“Looking at these developments from an optimistic perspective, maybe this is the long overdue necessary catalyst for the heritage world (museums, libraries, collections, etc.) to finally create a modern robust open source, online 3D heritage management platform.”[72]

5.3.2. Loss of Community Features

Many Sketchfab users expressed concerns over the lack of community features on Fab [73], as Epic Games will shift the platform’s focus from being community-oriented to focusing more on marketplace features. While community engagement or the integration of community features in the platform and a focus on the commercial side of this endeavour are not mutually exclusive, Epic Games made a conscious decision to prioritise the creation of a “a one-stop destination where you can discover, buy, sell, and share assets” [74]. For many Sketchfab users, community features were instrumental for building a following and receiving recognition for producing and sharing cultural heritage content. These features also allowed institutions to measure the impact of their digitised collections on audiences that may not typically visit their physical locations. These were also essential for justifying their 3D digitisation efforts, e.g., by keeping track of analytics, such as downloads and likes. At the same time, Sketchfab’s marketplace and those selling their creations on the platform benefitted from such tools, as they were instrumental in providing users with additional income. Features such as creating collections and likes, as well as the option to subscribe, follow, and share with a direct link or to a social media platform, helped creators to form a loyal base of followers and 3D enthusiasts around their work. The following quotes illustrate these sentiments:

“I have creds and stats that are badges of honor. What was ALL that effort I put in for?”[75].

“To merge sketchfab into a bigger, better store would be one thing. But to kill EVERY SINGLE ONE of sketchfabs community features?”[76].

“7y of work gone for me”[77].

In response to these comments, Sketchfab released an announcement on 23 September stating that removing the community features is a necessary measure to transition to Fab but also that they “plan to offer enterprise analytics solutions in the future, when content management solutions become available in Fab” (Sketchfab Support, personal communication, 23 September 2024).

5.3.3. Accessibility and Institutional Support

Several members of the community highlighted Sketchfab’s user-friendly interface that enabled both institutions and individuals to upload content and end-users to seamlessly access it. Users particularly appreciated the platform’s reliability, noting that they rarely encountered technical issues such as broken links and workflow disruptions, a common problem with many online platforms, especially those managed by institutions. Sketchfab’s accessibility extended beyond technical ease as it also fulfilled a key role in education. Instructors were able to integrate 3D models into their curricula by having students develop and upload to Sketchfab their own models or by providing access to models created by others. This enriched the learning experience by offering new modalities of instruction and engagement with cultural heritage content. These quotes further emphasise the community’s perspectives:

“great resource [and] would be sad to see the access disappear! It is by far currently the most user friendly way to access the data outside institutions.”[78].