Abstract

This paper explores the possibility of counteracting the crisis of culture and institutions by investing in the identity values of the user-actor within digital spaces built for the purpose. The strategy is applied to the analysis of three Catalan cloisters (Spain), with a focus on the representation of the cloister of Sant Cugat (Barcelona). Heuristic picklocks are found in the semantic richness proposed by Marius Schneider exclusively on the verbal level. The authors interpret the contents and transcribe them into graphic signs and digital denotations of sounds and colors. They organize proprietary ontologies, or syntagmatic lines, to be entrusted to the management of computer algorithms. The syncretic culture that characterized the medieval era allowed the ability to mediate science and faith to be entrusted to the mind of the praying monk alone in every canonical hour. The hypothesis that a careful direction has programmed the ways in which to orient souls to “navigate by sight” urges the authors to find the criteria that advanced statistics imitates to make automatic data processing “Intelligent”. In step with the times and in line with the most recent directions for the Safeguarding of Heritage, the musical, astral, and narrative rhythms feared by Schneider are used to inform representative models, to increase not only the visual perception of the user (XR Extended Reality) but also to solicit new analogies and illuminating associations. The results return a vision of the culture of the time suitable for shortening the distances between present and past, attracting the visitor and, with him, the resources necessary to protect and enhance the spaces of the Romanesque era. The methodology goes beyond the contingent aspect by encouraging the ‘remediation’ of contents with the help of machine learning.

1. Introduction

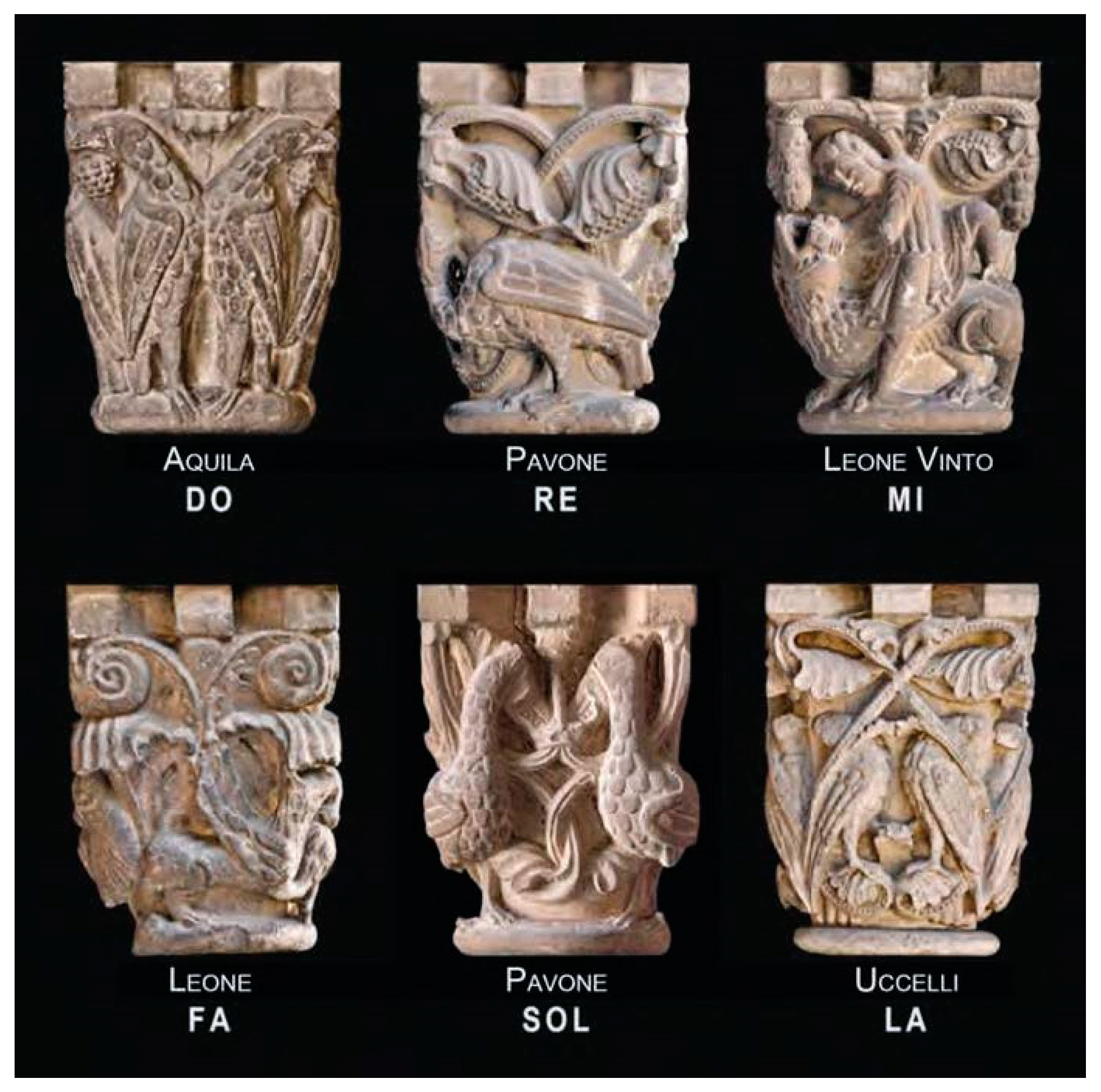

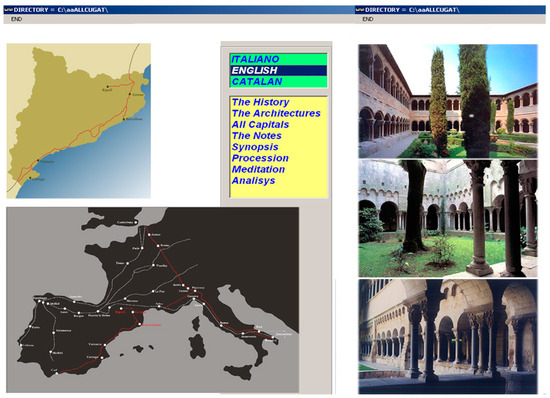

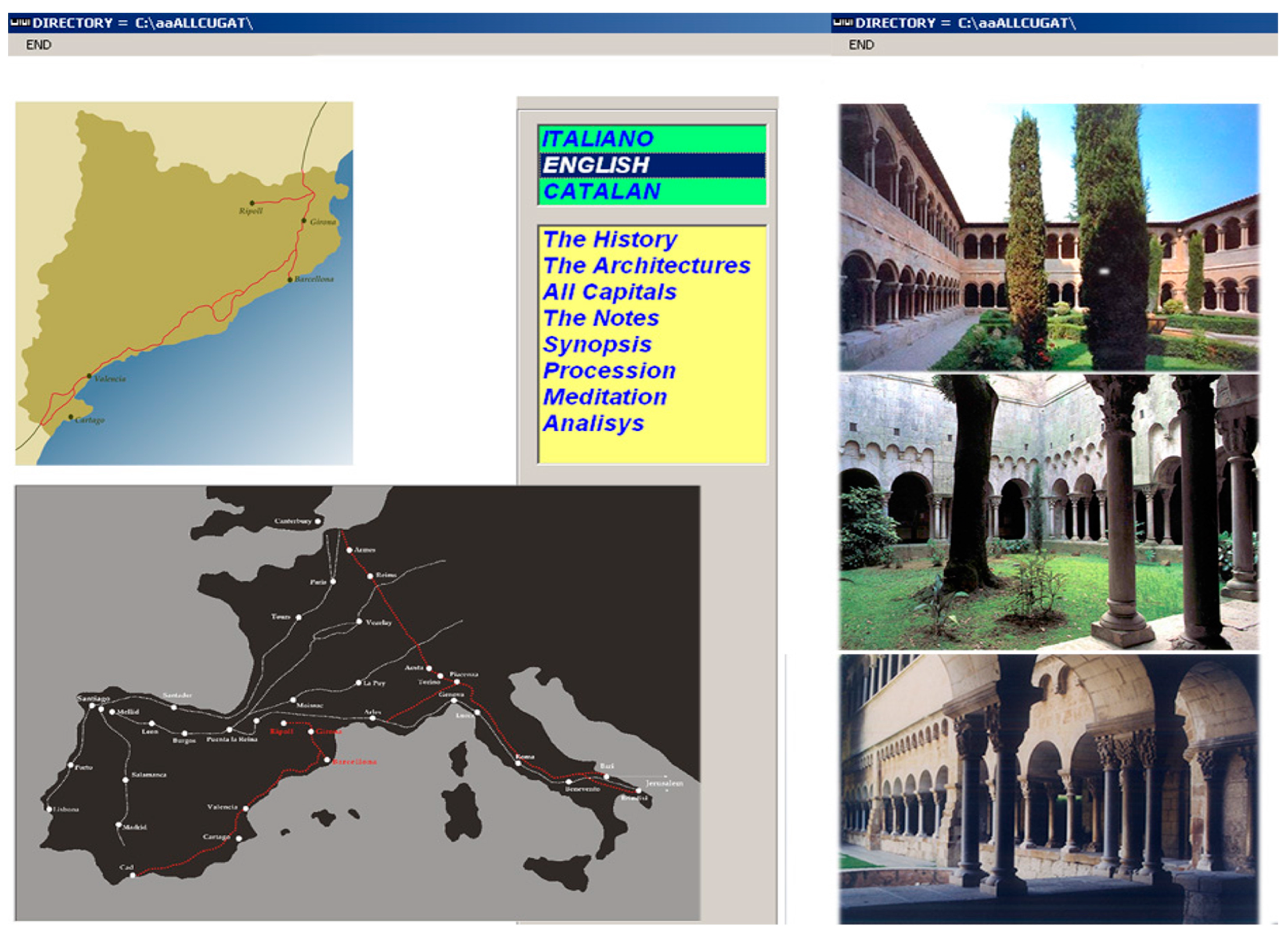

In addition to the Romanesque style, the Catalan cloisters of Sant Cugat, Girona, and Ripoll (Figure 1) are united by the type of ornamental figures that decorate the capitals. These connect groups of small arches supported by a double order of slender columns resting on a single base that circumscribes the central garden so that the bas-reliefs remain at eye level for those walking along the lateral ambulatories (Figure 2).

In the style of the bestiaries of the time [1], one can recognize—sculpted in the bas-reliefs—feathered birds, small and large birds of prey, lions, bulls, roosters, sheep, chimeras, and other types of fantastic animals, among which compositions of leaves and fruits, atlases, and mythological and narrative scenes alternate. It seems difficult to try to find a logical connection in the succession of these icons that Bernard of Clairvaux would not hesitate to consider “ridiculous monstrosities” (letter to his cousin Robert of Châtillon 1124) to be prohibited in the place dedicated to prayer and meditation such as the cloister, the paradise (from paradesha in Sanskrit, with the meaning of ‘supreme country’) built in the image of the Heavenly Jerusalem [2]. Although the Father of the Benedictine Rule had been dead for some decades and the rebellious position of the abbot of Suger de Saint-Denis (1127–1140) had been welcomed in the monastic communities, it seems at least strange that the abbots of the three abbeys allowed the engravers unconditional freedom.

Figure 1.

Location of the Catalan cloisters. From top: Sant Cugat, Girona, Ripoll, recalled by the VisualBasic interface [3] (pp. 353–362).

Figure 1.

Location of the Catalan cloisters. From top: Sant Cugat, Girona, Ripoll, recalled by the VisualBasic interface [3] (pp. 353–362).

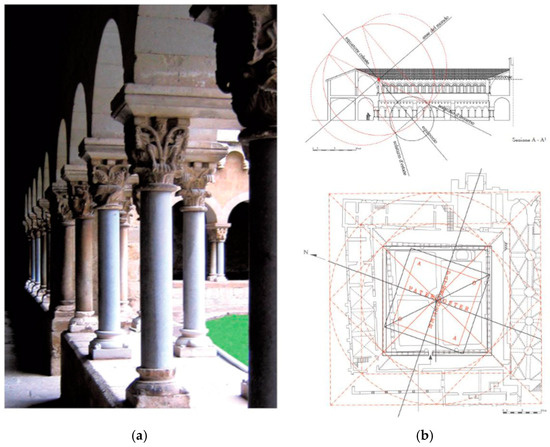

Figure 2.

Sant Cugat del Valles, interior of the abbey cloister: (a) western gallery—photo by the author; (b) elevation of the eastern gallery associated with the planimetric survey; superimposed is the ice plan derived from the interpretation of the indications contained in the Carmen de Laide vitae monasticae [3] (p. 139).

Figure 2.

Sant Cugat del Valles, interior of the abbey cloister: (a) western gallery—photo by the author; (b) elevation of the eastern gallery associated with the planimetric survey; superimposed is the ice plan derived from the interpretation of the indications contained in the Carmen de Laide vitae monasticae [3] (p. 139).

To this possibility, Marius Schneider (1903 Hagenau—1982 Marquarstein), one of the most erudite ethnomusicologists of the twentieth century [4] (p. 207) and an expert in the history of art and natural philosophy, counterposes the hypothesis of a careful direction. “Modern man—writes Schneider—barely perceives the great inscrutability of the acoustic world, the polychromy and polyrhythm and the force of sound from which the ancient cosmogonic legends made the visible and tangible world proceed” [3] (p. 2). Convinced, like many of his contemporaries, that the sounds of animals had directed the first steps towards a melodic phenomenon, he decodes the icons of the three cloisters, obtaining from them, in comparison with the mythological sculptures, a code of sound’s heights. He correlates the mystical meaning of the words found in the Mātya-śāstra attributed to the Brahmin Bharata (4th–5th century) to the syllables extracted from the wisdom stanzas of the RgVeda Saṃhitā [5,6,7] (p. 9550). Then, he superimposes syntagmatic lines extracted from what the wise men had been able to deduce by observing the sky and the stars (from the term vedantā), the local tradition filtered through history [8] (p. 13), the wisdom of Artisù (as Aristotle—384–322 BC—made known in Persia) and, last but not least, the analogies outlined by Father Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680).

Unlike the symbols placed inside a pentagram, the zoomorphic denotation code identifies “signs” that must be interpreted in the context of the scenes: “it is the sense of the ’forming’ shapes, rather than the ’formed’ shapes, that must be understood and decoded” [4] (p. 207).

In the tendentious interest of the authors, the zoomorphic attributes perceived as musical “notes” designate thematic contexts that make the monks protagonists: to the sensitivity, to the culture, the mood of the moment is entrusted with the task of processing the (im)material information provided by the single icon read in succession of the apparent path of the sun. The intellectual and synaesthetic capacities of the single monk mediate faith and science in the meditative experience. Musical, narrative, biblical, historical, daily, seasonal, solar, and astral rhythms guide creative associations that are casually interactive rather than linear deductive–inductive.

With the lenses of current events, the keys offered by Schneider’s narration are used by the authors as picklocks to organize digital contents to be inserted within cultural products developed with the aim of increasing and extending the perception of the user who has become the protagonist. Digital tools and technologies allow the expansion of the limits of spaces to increase the user’s perception by inserting contents (MR, Mixed Reality). They allow for offering cloud computing models to extend the components to non-visual characteristics (XR, Extended Reality). In addition, the most recent computer research promises to articulate, figuratively or literally, multidimensional and multimodal involvement paths extended to the presentation and evocation of immaterial characters.

For this purpose, repeated surveys on the cloister of Sant Cugat, elected as an emblem of experimentation, have the aim of exploiting reality-based acquisitions to share and make some of the contents interoperable [9]. The resulting schedule of information models, if managed by the “Visual Sciences” [10,11], use digital twins [12] to promote updated forms of knowledge [13].

Beyond maintenance, restoration, renovation, or description for future reference, the authors discuss the possibility of countering the current crisis of culture and institutions and investing in the promotion of protection and exploitation policies. Compatible with the vulnerability and preciousness of the artefacts, digital knowledge and production develops a territory of common goods, a sort of cultural vision [14] within which each person can intervene according to specific purposes (research, professional, educational, dissemination, touristic, etc.) but with the necessary attention to the complexity of the whole.

The rediscovered concept of the environmental atmosphere [15] invites an awakening of the sensorial dimensions neglected by modernity, to interdisciplinary dialogue, to the inclusive flexibility and accessibility needed to ‘remedy’ reflections and actions to loosen the distances between past and present [16].

The title, “Digital Colors”, therefore, refers to the musical, astral, and narrative rhythms supposed by Marius Schneider. The synaesthetic qualities of the Romanesque space, in fact, invest in the identity values of the users—those that the artificial intelligence processes [17] try to emulate by studying the human brain to identify a model suitable for solving practical problems through the optimization of mathematical functions processed at a superhuman speed.

The subtitle, instead, places the acceptance on what—in line with the definitions and recommendations of the ICOMOS [18]—ensures the transmission of traditions. The atmosphere of the three Romanesque cloisters involves and refers to the syncretic character of medieval culture and, in parallel to the possibility of designing an information space dedicated to the theme. Within a shared environment (ACDat, ACDoc, CDE), accredited and differently enabled subjects (UNI 11337) could interactively use sources, studies, and elaborations by making the ‘Data Science’ dialogue with ongoing research. The study is part of the disciplinary debate [19] that goes beyond contingent aspects, using criteria and principles that are hoped to be a reference for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

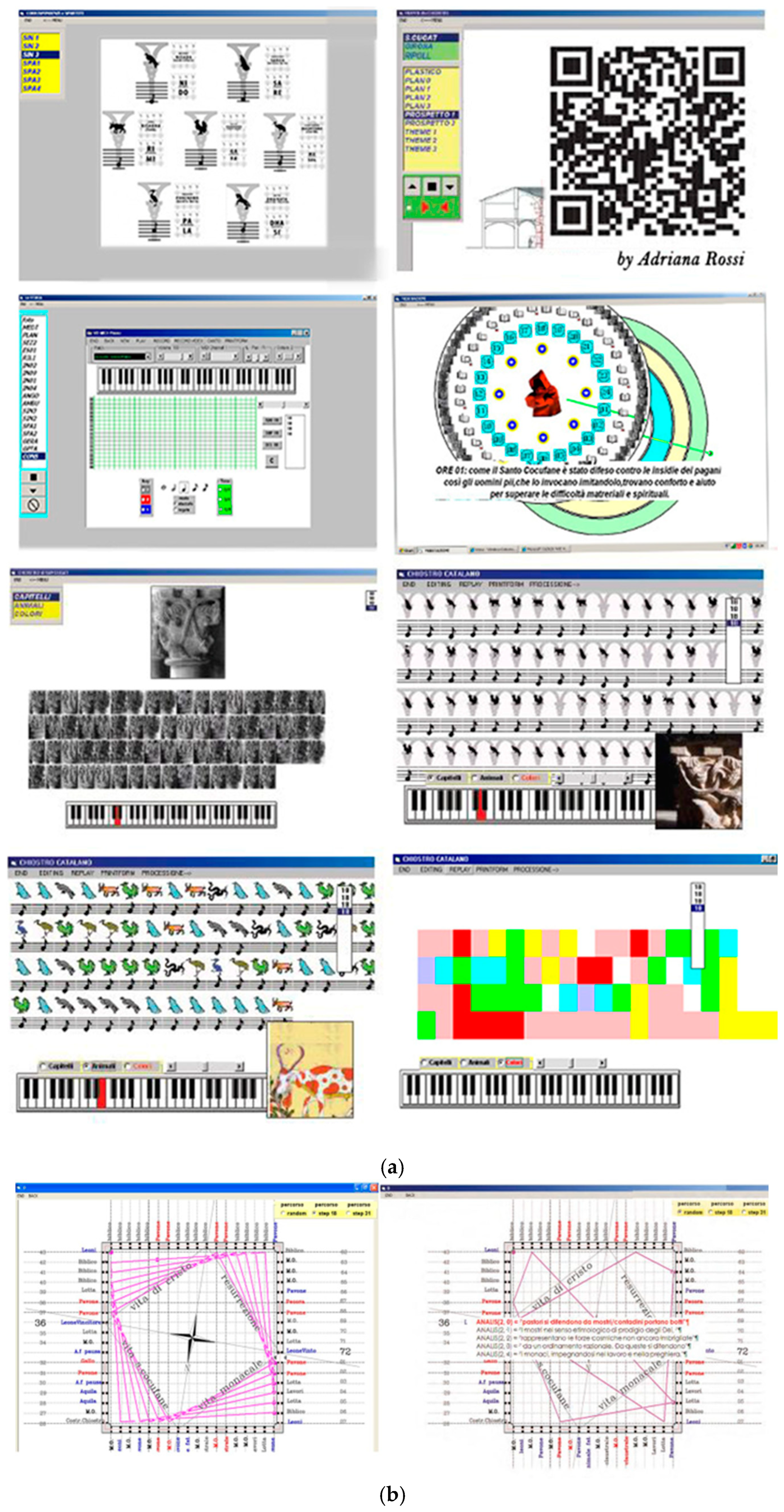

The knowledge that the paper shares is based on the studies, particularly those dedicated to the iconographic succession of the cloister capitals of three Catalan abbeys, by Marius Schneider, a well-known ethnomusicologist of the early twentieth century who trained at the Wiener Schule der Kunstgeschichte. In his texts, which are essentially verbal writing, iconic references are rare, mostly limited to a few photographs and graphic schemes for caption notes. The graphic transcription of concepts in extracted/abstract signs is, therefore, prodromal [20]. Subsequential, then, is the transcription in original representations of the schemes of anodic mathematical meaning necessary for algorithmic denotations [3,21]. The need to re-present the canons of a culture that “sees” through hearing has directed the development of a program to produce musical phrases.

A musical phrase is a set of notes that can be sung with a single emission of voice that corresponds to the spatial-temporal metrics of one side of the cloister. All the necessary instruments for scoring a piece of music are present. The time value of the notes is given by the symbols below, while the pitch is recorded on a normal staff or stave. At this stage, it is possible to delete, re-write, and copy entire musical phrases. The number of notes of each one, corresponding to the number of capitals, is indicated in the list at the top on the right. Focusing attention on the example chosen as a case study, the musical structure of the “Iste Confiteor”, the Gregorian chant identified by Schneider corresponding to the architecture of the cloister of Sant Cugat, was transcribed.

The chant had to be composed of four musical phrases, as many as the sides, with the notes as many as the column positions for each side. In addition, it had to satisfy three different ordering principles: (i) the pitches of the sounds, (ii) the rhythm, and (iii) the overall length of the chant. So, the pitches of the sounds had to be homophones of the attributes encoded in different syntagmatic lines (Figure 3a,b) ontologically superimposable to the astral and narrative correspondences simplified in the decoding of the zoomorphic code. When syntagmatic lines fall into contrast, decorative-ornamental patterns replace the signs of zoomorphic language. For representative purposes, several depictions have been introduced that are contextually recalled to the denotation of the musical note that, in succession, makes the Gregorian chant audible in the version dedicated to the patron saint (Figure 4a). In the meantime, it shows an association of photographs of the bas-reliefs and progressively more abstract forms, such as the colors associated with the notes based on the Newton frequency ratio. The hypothesis that a careful direction has planned the ways in which to orient the souls of the monks to “navigate by sight” allows us to orient communication strategies through interdisciplinary approaches. Immersive involvement paths have therefore been developed within the joint research carried out with Prof. Pedro M. Cabezos Bernard, a visiting professor within the chair of “Advanced representation techniques” in 2016 at the engineering department of Vanvitelli University [22]. The latest study instead addresses the accessibility of data [23]. The revised, corrected, and expanded materials are “systematized” by the authors of this article to address new forms of participatory knowledge [24].

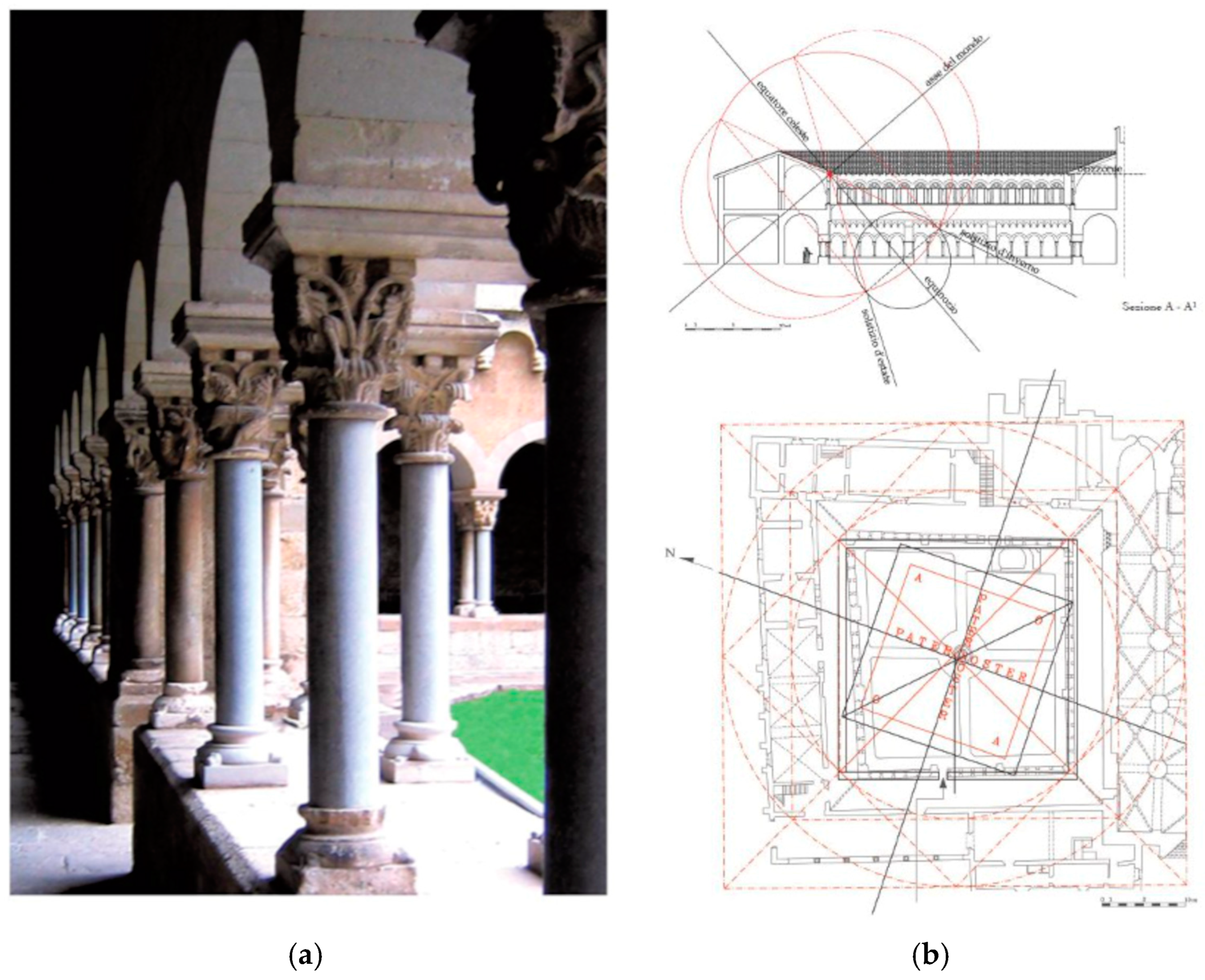

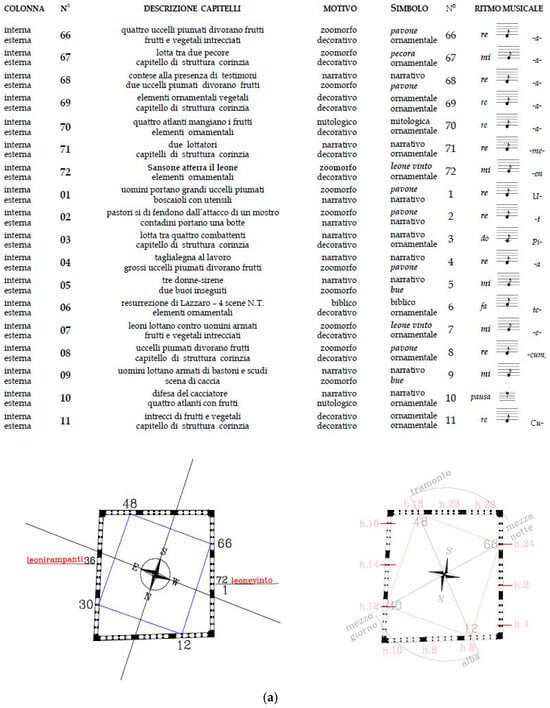

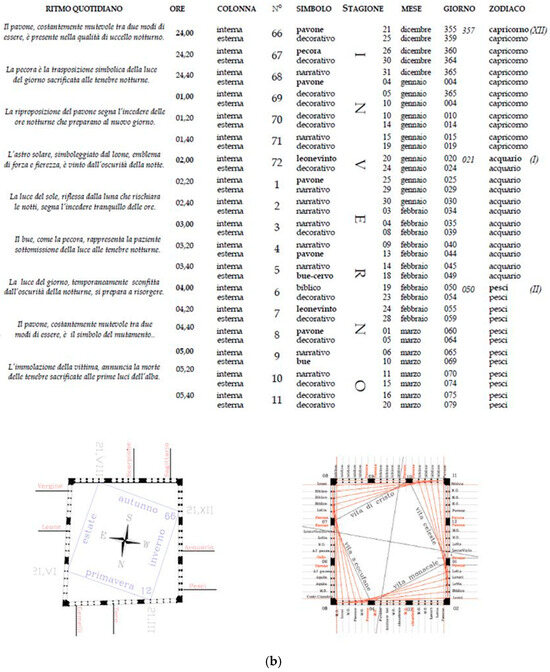

Figure 3.

(a,b) In the succession of columns, with positions numbered by M Schneider, a palimpsest of the information recalled by the same bas-relief.

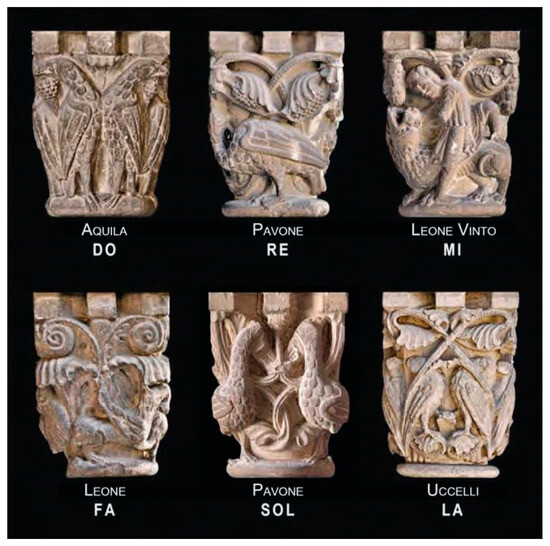

Figure 4.

(a) From Sanskrit syllables to words to decoding the central actions of zoomorphic motifs. (b) Symbolic representation of the thematic correspondences associated with the abstract zoomorphic motif.

Decisive for the purpose, the critical review of the literature aimed at representing the (im)material goods to ‘remedy’ experiences based on the integration of digital methodologies [25,26]. Case studies show the growing attention towards components extended to the approach to interdisciplinary strategies suitable for attracting a large audience of users. The auditory, olfactory, and imaginative dimensions expand our perception, playing a significant role in the satisfaction of users transformed into consumers of culture.

3. Towards Updated Forms of Participatory Knowledge

Not at all willing to delve into the controversy raised about the musical nature of the capitals or the scientific validity of the supposed rhythms, the occasion proved propitious to experiment with updated forms of knowledge.

A video, called from within the Visual Basic 6 software (Figure 5), was dedicated to the evocation of the great inscrutability of the acoustic world to the polychromy and polyrhythm of sound [4] (p. 13).

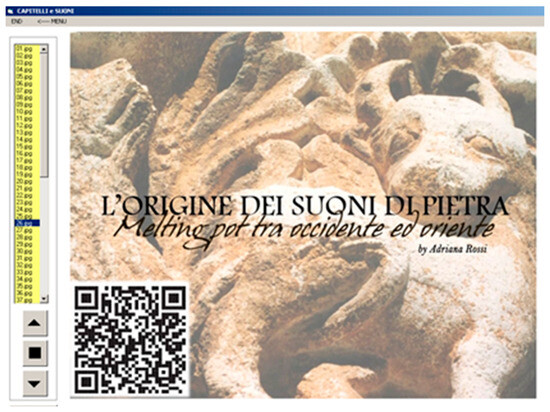

Figure 5.

The video edited by the authors (QR1) is inspired by Schneider’s theories to evoke the universal characteristics of the zoomorphic code used to evoke attributes of different quality classes.

It presents, edited by the authors, what was prompted by studying Schneider’s texts and integrated to communicate the universality of the zoomorphic code, understood in every time and geographical place. The mystical meaning of the tonal syllables and the actions to which they refer is inspired by Hindu wisdom [4] (p. 13) and [27].

The Historia Animalium [28] (467, 26) informs the features of the stories used for educational purposes by the Persian Anvar-i-Suhayli and the Syrian Kalilag and Damnag, but also by the Alexandrian Physiologus (2nd century). The Tales of Bidpay, to whom we owe the numerous popular declinations of the Pancā-tantrā revisited by the Thousand Fables (Hazār afsane, 10th century), known in the 12th century as the Stories of the Thousand and One Nights (Alf layla wa-layla, 12th century), arrived in the West with caravans of soldiers and goods. Le Petit Prince (1943), written by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in the last century and translated into fourteen languages, draws on the Canterbury Tales (1387) or the fairy tales of Jean de la Fontaine (1621–1695). The French writer inspired the characters “invented” by Walter Disney. More recently, when the Middle Eastern question imposed itself on European culture, Sulayman Al-Bassam, the Kuwaiti director, staged a revisited version, The Mirror For Princes (Oxford Playhouse London 2004); the simplicity of the animals’ language invited tolerance and peaceful coexistence. For the same reason, “modern” characters were broadcast on French and German TV, inspired by Saint-Exupéry’s autographed watercolors.

To align, instead, the semantic richness suggested by the Alsatian scholar to the expectations of visitors or to the values of users, or better, to the preferences of users’ protagonists of the claustral spaces, it is first necessary to present in digital form the common attributes, in other words, the substantial characteristics that, well beyond the properties, unite sets of data (Figure 4b). It is through these categories of sets that new analogies and creative associations can sometimes prove illuminating. A criterion of ‘organic differentiation’ directs the naming of classes of elements-objects evoked by the same action carved in succession. The code of signs is the zoomorphic one, abstracted by the authors from Schneider’s texts and presented in graphic representations. There are four groups identified by column-posts assumed as borders of regions, places of passage between day/night hours, seasons, constellations, and events with common attributes. The authors have observed that in the eastern gallery, starting from the entrance to the garden, the iconic descriptions allude to episodes tendentiously classifiable as belonging to scenes of daily life, monastic life, and subsequently to the narratives of the Old and New Testament. In the direction of the apparent path of the sun, within the group identified by 18 steps, strings of information superimposed on the same column-post (Figure 6) can be variably connected by the vertices of quadrangular, regular, or random geometric figures with one’s own culture, sensitivity, and state of mind, and the praying monk makes the experience significant. The quality of meditation is a function, among other things, of the semantic richness of the data “systematized” and oriented by the (im)material characteristics of the cloistered atmosphere. Gregorian chant accompanies meditation; it is a chanted prayer, well known to the brothers of the monastery who chant it in the version dedicated to the patron saint and transcribed in graphic signs of a zoomorphic nature [4] (p. 26). A spectrum of compositional rules can be found in the “Grammar of Fantasy” [29].

The results of the processing, if isomorphic to the objectives, are defined as intelligent. Artificial intelligence (AI), in fact, refers to: “the development of computer systems capable of carrying out activities that would normally require human intelligence, such as pattern and speech recognition, play and decision-making, and problem solving” [30]. Data-driven machine learning is a subset of AI that focuses on developing algorithms and models that allow computers to learn from experience without being explicitly programmed. ML algorithms learn patterns and relationships from large data sets and use this knowledge to make predictions, classify data, or make decisions [31].

Within human–machine collaboration spaces, large-scale big data are managed, in any case, and transcribed in table format [32]. Much more modestly, the classification system used at the time derives from traditional constraints detected and governed with the aid of electronic spreadsheets that place ordered strings of characteristics in relationships.

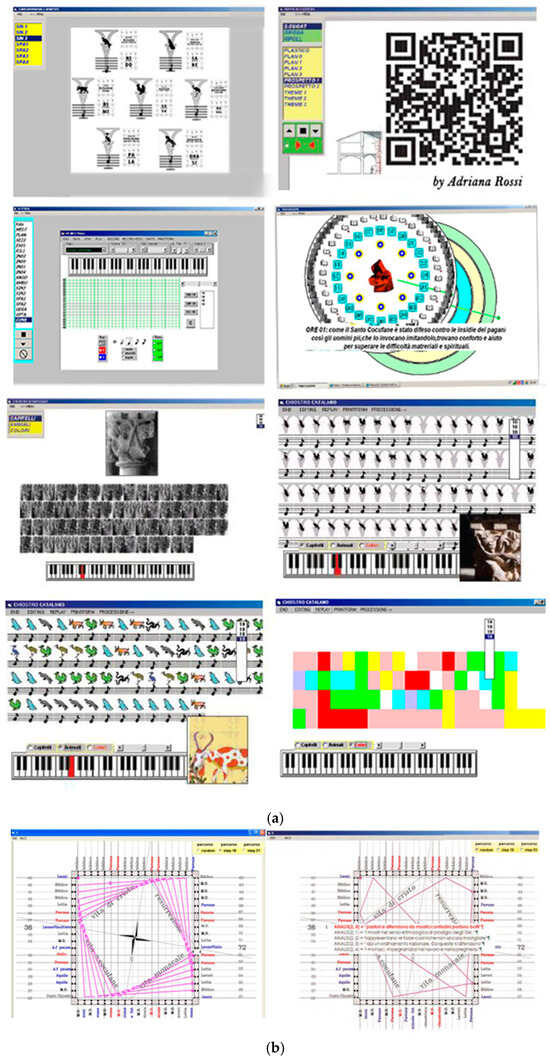

The car provided by Visual Basic (VB) seemed to be functional for the purpose, which, in version 6 guaranteed simplified access to the applications. Quickly, even for those who did not have computer skills, the chosen software allowed for writing sequences of instructions that, foreseeing a stop, were configured as algorithms useful for mapping connections cantered on the identity of the “objects” (Figure 7). The work environment did not imply the use of punctuation typical of contemporary programming systems (Figure 8). Shifting the focus from figurative properties to identifying attributes, the computer aids made available by Visual Basic allowed for the recall of classes of identified and abstract characters within the quadrangular space. Based on a criterion of ‘organic differentiation’, classes of attributes collected in syntagmatic lines on the same column station could be recalled in random or geometric mode to simulate the approach to the evolution of a creative thought, following the example of the never-too-often cited [29]. The modes are now approachable if assisted by machines capable of managing a large amount of information [33].

Figure 7.

Orthophotos of the reality-based 3D textured capitals Tonal correspondences derived from the interpretation of the ontological contents of the zoomorphic actions.

Figure 8.

(a) The Visual Basic screenshot regarding the functions quoted by the users; QR code to access the download of the software: https://extra.libreriauniversitaria.it/QR2.zip; (accessed on 23 December 2024) (b) jumps between classes of characteristics with geometric rule (on the left) and random (on the right).

Figure 6.

(a) Symbolic notation of the -ith row-column of the 72 column positions [3] (pp. 230, 173). On the left: at the top, the notes actually sung by the zoomorphic code; at the bottom, the complete score. On the right: at the top, the days of the year; at the bottom, the distribution of the hour. At the bottom (b). (b) The representation of the small and large day. Above, in plan, and below, along the development of the four facades divided into categories of days and seasons [34] (p. 16).

Figure 6.

(a) Symbolic notation of the -ith row-column of the 72 column positions [3] (pp. 230, 173). On the left: at the top, the notes actually sung by the zoomorphic code; at the bottom, the complete score. On the right: at the top, the days of the year; at the bottom, the distribution of the hour. At the bottom (b). (b) The representation of the small and large day. Above, in plan, and below, along the development of the four facades divided into categories of days and seasons [34] (p. 16).

Visual Basic was not very adequate for the purpose, and for this reason, it was abandoned by the same manufacturer. Microsoft first enhanced the VB6 modes, later realizing that the latest version (NET Framework) was not very friendly for improvised programmers, thus canceling the main cause of its success. With reference to the most recent directions for the protection of Cultural Heritage, the ongoing research looks at the possibility of sharing what has been studied to enhance the participatory-predictive role of those who remotely inhabit the three abbey cloisters. The user, rather than being blocked in a univocal reading, as happened in previous approaches, must be encouraged to explore the cloistered environments to understand and update the experience based on their own needs and expectations. The representative model must, therefore, provide the community with paths capable of encouraging behaviors. A sort of hyper-technological capsule would be desirable, of the type prefigured with the imaginary universe of Avatar, when the science fiction film was written and directed by James Cameron, but which today promises to be simulated in many aspects by designing a space for human–machine interaction.

Leaving computer scientists the possibility of intervening with due attention within an ecosystem of information and federated models, the heuristic project through which to attract the user interested in the theme, but also the one casually intercepted through the traces left by surfing the web, remains of specific relevance to the Representation sector. Visitors become users, and they obtain content by transforming themselves consciously into consumers and/or producers of goods and services [35]. The difficulty that is feared is more than technical; it concerns the ability to conceive an engaging, flexible, inclusive, multi-disciplinary space to fit the interests of a wider audience.

To this end, it is necessary to revive the atmosphere of the time and orient today’s “consumers of culture” [36] towards the enjoyment of those characteristics that cannot be preserved in physical form but only experienced through a vehicle that gives expression.

Virtual tours invest the users with participatory responsibility. They are created within an ideal model (spherical or cylindrical) in which users can move freely and choose what to look at with the possibility of zooming in on areas of interest within it. Sound effects, music, or narrations can be integrated, and/or buttons can be inserted to access the open-source repositories. The interaction gradient is different: simple, like those offered by Google Maps, or divided into rooms made interactive with the help of enabling technologies.

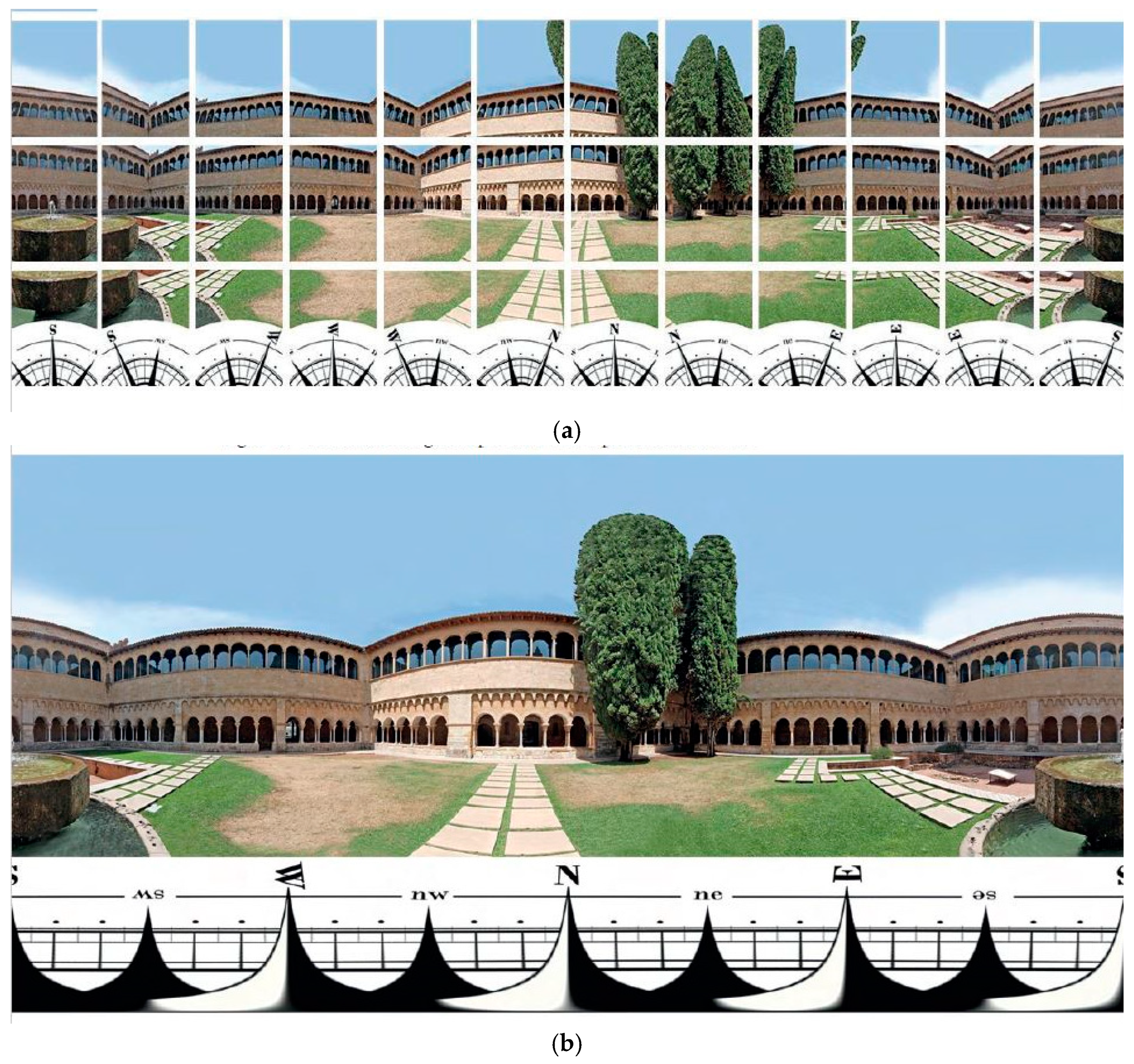

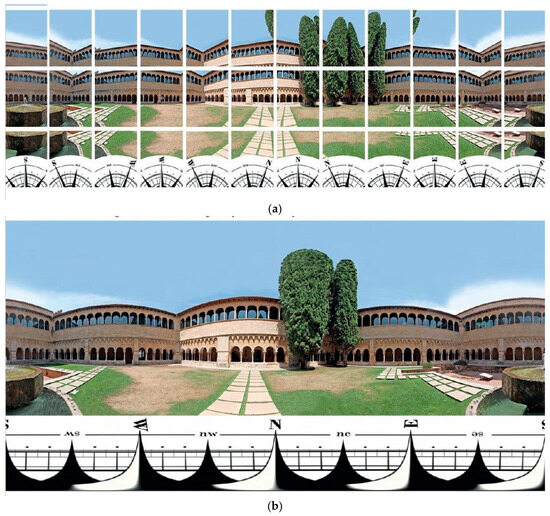

To integrate the first studies, the development of a spherical panorama [37] that allows viewing the cloister of Sant Cugat was elected as the emblem of the analyses. In an immediate and realistic way to start inhabiting the cloistered atmosphere from afar, a Real-Time Rendering engine or a web address allows an immersive approach by remotely directing the dissemination of the asset. Without manual transformations, the equirectangular projection (Figure 9a,b) re-maps the photos acquired with a rotating head equipped with a 180° fisheye lens into a two-dimensional image with the help of automated software (PTGui 12, image stitching software for stitching photographs into a seamless 360-degree spherical or gigapixel panoramic image). It achieves an ideal sphere whose radius is equal to the distance from the main nucleus of the camera to the taking surface, inside which it is possible to look at and approach the mosaic of photos, giving the sensation of being inside it.

Figure 9.

(a) 38 photographs to obtain the spherical panorama; (b) equirectangular projections of the images acquired [33].

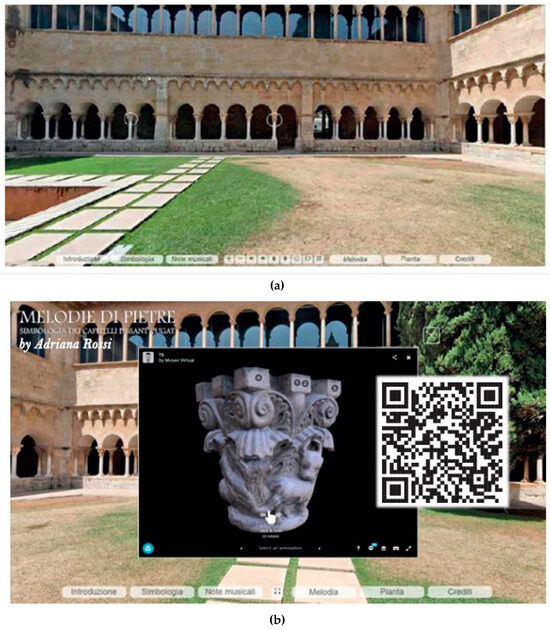

The spherical panorama has proven to be a suitable user interface for achieving a hypertextual structure of cloud registered models. The photogrammetric technique has proven to be crucial for the construction of digitally restored photo models of the sound capitals, placed at the service of the user who remotely enjoys a reconstructed space dedicated to various purposes, such as educational, cultural, research, enhancement, economic tourism, etc.

The detected 3D point clouds were acquired with the aid of passive sensors (Structure from Motion (SfM) was used to generate the gallery of sound capitals). These are manoeuvrable thanks to and by virtue of a 3D modeler made available by the platform in which they were uploaded free of charge—SketchUp has allowed for associating digitally archived metadata. You can listen to the song in succession by accessing the archive of uploaded information (Figure 10). Despite the excellent functionality of the platform used, the contents are static: where the link does not exist, specific information and, therefore, answers to the themes are missing.

Figure 10.

(a) Virtual museum interface (a) view of the cloister panorama; (b) interactive visualization of one of the capitals. QR code link to access the virtual gallery: https://extra.libreriauniversitaria.it/QR3/cugat/SanCugat.html (accessed on 23 December 2024) [22,33].

4. Discussion

Bringing individual research into dialogue with data science is a challenge that is far from won. There are two fundamental reasons: the first lies in the limits of digital models that currently approach but do not create experimental paths that are adequate to the premises, and the second is characterized by adequately intelligent trajectories to show and go beyond the semantic richness recalled by Schneider. The provocation has the merit of nevertheless provoking a reaction on the issues raised: creating new paths of involvement for Romanesque art; and advancing the debate on the use of extended reality and digital twin methodologies in heritage conservation. The effort to approach a flexible and inclusive interaction that the philosophy of science promises to achieve within the evolutionary mechanisms of each discipline remains noteworthy [38].

On the threshold of what proves to be a further phase of automation of interpretative and interactive processes, the interactive circularity of analysis and synthesis (once rigorously separated, today ensured by the digital supply chain) directs us to the ontological organization of knowledge, i.e., concerning the essential aspects of existence. Available for professional or study use at every stage, the ontological organization of knowledge is implementable, verifiable, and optimizable. The geography that identifies scientific knowledge, therefore, builds a sort of “cathedral” [39]. In our case, it approaches the culture of the medieval world, a culture that remained elusive in many perspectives [40] (p. 15) and obscure and controversial [41] due to the mystery that surrounded the syncretism of many aspects at that time.

The overcoming of many technological limitations in the recent past has directed research and dissemination towards a wider, more conscious, and standardized use of digital media with multiple levels of interpretation [42,43,44]. Complex digital platforms have been created with increasingly powerful and widespread systems that serve as useful research tools for experts in the field, such as some developed by the authors [45,46], but also up-to-date open-source 3D model presenters and frameworks [47,48] to create dynamic and increasingly interactive scenes for the average user, exploiting the 3D scene for captivating virtual tours and adaptable to any device.

Today, when programmers’ work is based on learning techniques, the limit encountered by developers who write the system’s operating code lies in the ability to reshape the contents rather than in the technologies made available by computer science research. Thousands of articles delve into the methodologies of survey and representation; few are concerned with the ability to imagine an information space adequate to contemporary expectations [48].

Today’s ubiquitous use of AI is revolutionary and is becoming a turning point for everything related to the creation of virtual experiences [17], both engaging and explanatory, in order to disseminate to a wide audience of users and enrich with content a digital base that is the starting point for a fuller and deeper understanding of Cultural Heritage or even of topics related to it at more diverse levels, as in the case study, that span multiple domains, including intangible ones.

Inherited goods have ceased to be the object of the “treasure chests” of history or “the deposit of the mummified Great Beauty” [36]. They have become a heritage linked to the history of the past but mainly a resource to comply with present needs. A careful eye cannot fail to notice that the deepest instances of Cultural Heritage aim to transform the crisis of institutions and memory into an opportunity for the development and production of new scenarios [43]. In fact, the next steps in the roadmap are to realize the existing potential with ever more modern and flexible tools to improve the user’s perceptive visualization and not only, but above all, to bring about the extended development of the acquisition of concepts beyond the tangible and material sphere, to be evoked with systems that emphasize overlapping registers [49].

The focus of the communication paradigm shifts, therefore, from the object “on display” to the subject who benefits from the production of products and services that develop around them [49]. The resulting intellectual wealth draws on representation, expression, knowledge, or skills; it includes tools, objects, artefacts, and cultural spaces supporting a practice that communities recognize as adequate for the protection of an “intangible” Cultural Heritage. In accordance with the indications formalized in the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, the semantic wealth discussed by Marius Schneider is proposed as an intellectual lever for the design of a significant information space. In reading Schneider’s texts, in fact, one can grasp the invitation to undermine the consolidated relationships between systems and to use the synergies found within the digital process chain, which, for different purposes, can govern the transmission of the inherited heritage [23].

5. Conclusions

Leveraging the empathy of the moment, the syncretic and metaphorical culture of the time allowed the mind of the monk praying among the bas-reliefs of the cloistered capitals to remedy science and faith in prayer paths, “navigating by sight”. In this way, new analogies and creative associations sometimes made the meditative experience enlightening. The hypothesis that a careful direction has planned how to orient the behavior of the monks within guided paths to a pre-established goal flexibly inclusive of identity values has urged the authors to use the musical, astral, and narrative rhythms feared by Schneider to inform representative models and increase the perception of the contemporary user with digital content that is not only visual (XR-Extended Reality).

In step with the times and in line with the most recent directions for the Protection of Heritage, a criterion of “organic differentiation” organizes ontologies of information or syntagmatic lines to be entrusted to the management of computer algorithms.

The results provide a vision of the culture of time suitable for shortening the distances between present and past and attracting visitors, and, with it, the resources needed to protect and enhance the spaces of the Romanesque era. This is a heritage that is ignored today but that, in the time and space in which it was realized, contributed to forging the Eurocentric identity.

The methodology goes beyond the contingent aspect by encouraging the possibility of ‘remediating’ experiences with the help of machine learning. In fact, the ambitious goal of developing a cultural vision supported by digital knowledge and production systems aimed at creating a territory of common goods remains unexplored.

Traveling in time and space is the current challenge. Representing the complexity of matter, form, structures, functions, and behaviors is the goal to pursue to imagine a culturally adequate heritage and guarantee memory while respecting future needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.; methodology, A.R.; software, A.R.; validation, A.R., S.G.B. and S.B.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, A.R.; resources, A.R., S.G.B. and S.B.; data curation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, A.R., S.G.B. and S.B.; visualization, A.R., S.G.B. and S.B.; supervision, A.R.; project administration, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: QR code to access the short films https://extra.libreriauniversitaria.it/QR1.zip; QR code to access the download of the software: https://extra.libreriauniversitaria.it/QR2.zip; QR code to access the virtual gallery: https://extra.libreriauniversitaria.it/QR3/cugat/SanCugat.html. All links have been accessed on 23 December 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Orlandi, G. La tradizione del Physiologus e i prodromi del bestiario latino. In L’uomo di Fronte Al Mondo Animale Nell’alto Medioevo; Fondazione del Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo: Spoleto, Italy, 1985; Volume 2, pp. 1057–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Pistilli, P.F. Chiostro, s.v. Enciclopedia Dell’arte Medievale; Treccani: Rome, Italy, 1993; pp. 449–457. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. Melodie di Pietre; Edizioni Scientifiche e Artistiche: Naples, Italy, 2014; p. 442. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M. Introduzione 1970. In Il Significato Della Musica. Antologia degli Scritti di Marius Schneider, 1st ed.; Zolla, E., Ed.; Audisio, A.; Sanfratello, A.; Trevisa, B., Translators; Rusconi: Milan, Italy, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, S.Ṛ. Hinduismo; Giovanni, F., Ed.; Economica Laterza: Bari, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Panikkar, R. I Veda; Rizzoli: Milan, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dandekar, R.N. Vedas in Encyclopedia of Religion; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 14, p. 9550. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M.K.A. Singende Steine. Rhythmus. Studien an Three Katalanischen Kreuzgängen Romanischen Stils; Bärenreiter: Basel, Switzerland, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Banfi, F. Virtual Heritage. Dalla Modellazione 3D all’HBIM e Realtà Estesa Completare Dati; Maggioli Ed.: Rimini, Italy, 2023; p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoline, G. Visual Science: An Emerging Discipline. J. Geom. Graph. 1998, 2, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W.J.T. Image Science: Iconology, Visual Culture and Media Aesthetics; The Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, Y.; Gharineiat, Z.; Karimi, A.A.; McDougall, K.; Rossi, A.; Gonizzi Barsanti, S. Digital Twin Technology in Built Environment: A Review of Applications, Capabilities and Challenges. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 2594–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L.; Russo, M. Semantic Driven Analysis and Classification in Architectural Heritage. Disegnarecon 2021, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L. A Digital Ecosystem to Document, in Space and Time, the Restoration of Notre-Dame de Paris. Available online: https://www.canal-u.tv/chaines/mshvaldeloire/fair-heritage-17-and-18-juin-2020 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Brusaporci, S. Architectural Heritage Imaging: When Graphical Science Meets Model Theory. Disegnarecon 2023, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescarin, S. Videogames, Ricerca, Patrimonio Culturale; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2020; p. 314. [Google Scholar]

- Münster, S.; Maiwald, F.; di Lenardo, I.; Henriksson, J.; Isaac, A.; Graf, M.M.; Beck, C.; Oomen, J. Artificial Intelligence for Digital Heritage Innovation: Setting up a R&D Agenda for Europe. Heritage 2024, 7, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/what-we-do/image-what-we-do/151-intangible-cultural-heritage (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Salerno, R. Drawing as (in) Tangible; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2018; 1592p. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. (Ed.) Sons de Pedra. Barcelona: Patrimoni Arquitectònic Diputació de Barcelona, stampa sospesa. In Suoni Nella Pietra; Edizioni Scientifiche e Artistiche: Naples, Italy, 2012; pp. 369–451. ISBN 978-88-95430-44-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. The rhythm of the Cloister of Sant Cugat del Vallès. In Abitare la Terra; Gangemi Editore: Rome, Italy, 2006; pp. 36–42. ISSN 1592-8608. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.; Cabezos Bernal, M.P. Galleria 3D per la fruizione della cultura romanica/3D gallery for the contemporary fruition of Romanesque culture. In Territori e Frontiere della Rappresentazione; Cangemi: Rome, Italy, 2017; Volume 39, pp. 597–605. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. Sant Cugart del Valles. Verso L’accessibilità Dei Dati; Libreriauniversitaria.it Edizioni: Limena, Padova, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, C. Information Visualization: Perception for Design; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Hereinafter Referred to as UNESCO, Paris, France, 29 September–17 October 2003.

- 32nd session, of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Safeguarding of Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage: Towards an Integrated Approach, Nara, Japan, 20–23 October 2004.

- Panikkar, R. The Vedas; Rizzoli: Milan, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Simplicius. On Aristotle Physics; multiple volumes, (Ancient Commentators on Aristotle); Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rodari, G. Grammatica Della Fantasia. Introduzione All’arte di Inventare Storie; Einaudi Ragazzi: Trieste, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.J. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach; Pearson Education, Inc.: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sagiroglu, S.; Sinanc, D. Big data: A review. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Collaborative Technologies and Systems (CTS), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–24 May 2013; pp. 42–47, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Alì, M. (Ed.) Investire sul Capitale Immateriale per la Crescita, la Competitività e l’occupazione. Una Nuova Alleanza tra Scuola, Università, Ricerca e Impresa; Editori Laterza: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. Disegnare con. Marco Gaiani, Interviews. 3D Digit. Models Access. Incl. Fruition 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerquetti, M. The material and the immaterial. Towards a sustainable approach to management in the global context. In Il Capitale Cultural: Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage; Edition University di Macerata: Macerata, Italy, 2015; pp. 247–269. [Google Scholar]

- Irace, F. Design & Cultural Heritage. Immateriale Virtuale Interattivo/Intangible Virtual Interactive; Electa: Milan, Italy, 2014; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezos Bernal, M.P.; Rossi, A. Técnicas de musealización virtual. Los capiteles del Monasterio de San Cugat | Virtual musealization techniques. The capitals of the Monastery of San Cugat. EGA Rev. Expr. Gráf. Arquit. 2017, 22, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, N. Architecture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. An Introduction to AI for Architects; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2021; Volume 2, ISBN 9781350165519. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, L. Reconstruction de Notre-Dame de Paris: Contributions from Science and Technology Public Hearing at the Senate Organized by the Parliamentary Office for Scientific and Technological Evaluation (OPECST) l Speech by Livio de Luca, Director of the Laboratory. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vuzHbvL6SfI&ab_channel=ISPCCNR (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Granel, E.; Ramon Graell, A. (Eds.) Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Viatges per L’arquitectura Romànica; Collegi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; pp. 287–303. [Google Scholar]

- Montaner, D.L. (Ed.) Monestir de Sant Cugat del Vallès. Clausure. In Album Pintoresch-Monumental de Catalunya; Associació Catalanista d’ Excursions Científicas: Barcelona, Spain, 1878. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, E.; Rahaman, H. Survey of 3D digital heritage repositories and platforms. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storeide, M.S.B.; George, S.; Sole, A.; Hardeberg, J.Y. Standardization of digitized heritage: A review of implementations of 3D in cultural heritage. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spettu, F.; Achille, C.; Fassi, F. State-of-the-Art Web Platforms for the Management and Sharing of Data: Applications, Uses, and Potentialities. Heritage 2024, 7, 6008–6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollonio, F.I.; Rizzo, F.; Bertacchi, S.; Dall’Osso, G.; Corbelli, A.; Grana, C. SACHER: Smart Architecture for Cultural Heritage in Emilia Romagna. In Digital Libraries and Archives; Grana e, L.C., Baraldi, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bertacchi, S.; Al Jawarneh, I.M.; Apollonio, F.I.; Bertacchi, G.; Cancilla, M.; Foschini, L.; Grana, C.; Martuscelli, G.; Montanari, R. SACHER Project: A Cloud Platform and Integrated Services for Cultural Heritage and for Restoration. In Proceedings of the 4th EAI International Conference on Smart Objects and Technologies for Social Good, in Goodtechs ’18, Bologna, Italy, 28–30 November 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potenziani, M.; Callieri, M.; Dellepiane, M.; Corsini, M.; Ponchio, F.; Scopigno, R. 3DHOP: 3D Heritage Online Presenter. Comput. Graph. 2015, 52, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanini, B.; Ferdani, D.; Demetrescu, E.; Berto, S.; d’Annibale, E. ATON: An Open-Source Framework for Creating Immersive, Collaborative and Liquid Web-Apps for Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, M.E. Design & Cultural Heritage. Intervista Sulla Frontiera dei Beni Culturalii. 2014. Available online: https://www.artribune.com/progettazione/design/2014/09/design-cultural-heritage-intervista-sulla-frontiera-dei-beni-culturali/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).